#Trinity atomic blast

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

By Susan Montoya Bryan

LOS ALAMOS, N.M. — The movie about a man who changed the course of the world’s history by shepherding the development of the first atomic bomb is expected to be a blockbuster, dramatic and full of suspense.

On the sidelines will be a community downwind from the testing site in the southern New Mexico desert, the impacts of which the U.S. government never has fully acknowledged. The movie on the life of scientist J. Robert Oppenheimer and the top-secret work of the Manhattan Project sheds no light on those residents’ pain.

“They’ll never reflect on the fact that New Mexicans gave their lives. They did the dirtiest of jobs. They invaded our lives and our lands and then they left,” Tina Cordova, a cancer survivor and founder of a group of New Mexico downwinders, said of the scientists and military officials who established a secret city in Los Alamos during the 1940s and tested their work at the Trinity Site some 200 miles away.

Cordova’s group, the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium, has been working with the Union of Concerned Scientists and others for years to bring attention to what the Manhattan Project did to people in New Mexico.

While film critics celebrate “Oppenheimer” and officials in Los Alamos prepare for the spotlight to be on their town, downwinders remain frustrated with the U.S. government — and now movie producers — for not recognizing their plight.

Advocates held vigils Saturday on the 78th anniversary of the Trinity Test in New Mexico and in New York City, where director Christopher Nolan and others participated in a panel discussion following a special screening of the film.

Nolan has called the Trinity Test an extraordinary moment in human history.

“I wanted to take the audience into that room and be there for when that button is pushed and really fully bring the audience to this moment in time,” he said in a clip being used by Universal Studios to promote the film.

The movie is based on Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s Pulitzer Prize-winning “American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer.” Nolan has said Oppenheimer’s story is both a dream and a nightmare.

Lilly Adams, a senior outreach coordinator with the Union of Concerned Scientists, participated in the New York vigil and said it was meant to show support for New Mexicans who have been affected.

“The human cost of Oppenheimer’s Trinity Test, and all nuclear weapons activities, is a crucial part of the conversation around U.S. nuclear legacy,” she said in an email. “We have to reckon with this human cost to fully understand Oppenheimer’s legacy and the harm caused by nuclear weapons.”

In developing and testing nuclear weapons, Adams said the U.S. government effectively “poisoned its own people, many of whom are still waiting for recognition and justice.”

Adams and others have said they hope that those involved in making “Oppenheimer” help raise awareness about the downwinders, who have not been added to the list of those covered by the federal government’s compensation program for people exposed to radiation.

Government officials chose the Trinity Test Site because it was remote and flat, with predictable winds. Due to the secret nature of the project, residents in surrounding areas were not warned.

The Tularosa Basin was home to a rural population that lived off the land by raising livestock and tending to gardens and farms. They drew water from cisterns and holding ponds. They had no idea that the fine ash that settled on everything in the days following the explosion was from the world’s first atomic blast.

The government initially tried to hide it, saying that an explosion at a munitions dump caused the rumble and bright light, which could be seen more than 160 miles away.

It wasn’t until the U.S. dropped bombs on Japan weeks later that New Mexico residents realized what they had witnessed.

According to the Manhattan Project National Historical Park, large amounts of radiation shot up into the atmosphere and fallout descended over an area about 250 miles long and 200 miles (322 kilometers) wide. Scientists tracked part of the fallout pattern as far as the Atlantic Ocean, but the greatest concentration settled about 30 miles from the test site.

For Cordova and younger generations who are dealing with cancer, the lack of acknowledgment by the government and those involved with the film is inexcusable.

“We were left here to live with the consequences,” Cordova said. “And they’ll over-glorify the science and the scientists and make no mention of us. And you know what? Shame on them.”

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fallout 4 Bobblehead Locations

Concord/Lexington Area - NW

Perception bobblehead - Museum of Freedom: On a desk next to a broken terminal in the back of the room where the player character first meets Preston Garvey.

Repair bobblehead - Corvega assembly plant: On the very end of the top exterior gantry (blue balloon), southwest roof section of the plant building on top of a wooden box.

Saugus/Salem Area - NE

Explosives bobblehead - Saugus Ironworks: In the blast furnace, on the second level catwalk behind Slag's spawn, sitting on top of a control panel attached to the wall to the left of a steamer trunk.

Charisma bobblehead - Parsons State Insane Asylum: On Jack Cabot's office desk, close to the elevator, administration area.

Sneak bobblehead - Dunwich Borers: On a small metal table by a lantern, right next to the metal post terminal area #4.

Barter bobblehead - Longneck Lukowski's Cannery: Inside the metal catwalk hut, northwest upper area of the main cannery room.

Science bobblehead - Malden Middle School (Vault 75): On the desk overlooking the subterranean "training" area, within the science labs.

Central West Area (North of Natick)

Energy - Fort Hagen Command Center: In the command center, southwest kitchens, on a small table between two fridges. (Accessible only during/after the main quest Reunions).

Boston Area - Central

Lock picking bobblehead - Pickman Gallery: Last tunnel chamber where one can see Pickman; On the ground between brick pillars and a bin fireplace.

Strength bobblehead - Mass Fusion building: On the head of the metal wall statue/sculpture five levels above the lobby desk.

Speech bobblehead - Park Street station (Vault 114): In the overseer's office on the desk. Found when rescuing Nick Valentine after he goes missing.

Intelligence bobblehead - Boston Public Library: On the computer bank, mechanical room, northwest corner of the library.

Melee bobblehead - Trinity Tower: On a table in the cage where Rex Goodman and Strong are being held.

Medicine bobblehead - Vault 81: In Curie's office, southeast corner of the Vault.

Quincy Area - SE

Unarmed bobblehead - Atom Cats garage: On the hood of the rusty car in the main warehouse.

Endurance bobblehead - Poseidon Energy: On the metal desk with a magazine, near steamer trunk, central metal catwalk.

Agility bobblehead - Wreck of the FMS Northern Star: On the edge of the bow of the ship, wooden platform.

Luck bobblehead - Spectacle Island: In the 2nd deck pilot house of a green tugboat located at the southern end of Spectacle Island, on a locker shelf near the steamer trunk.

South Central Area

Small guns bobblehead - Gunners plaza: On the broadcast desk in the on-air room, first floor, west side of the building.

Big guns bobblehead - Vault 95: In the living quarters area, northern most room, on a radio.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bobbleheads - Fallout 4 Guide (Game Guides) (Guides) (Warren Guides)

Guide and Photo Mode photo by @warrenwoodhouse #warrenwoodhouse

CLICK HERE to see an archived version of this list. The location of the Endurance Bobblehead was changed in the Update Patch v1.12 on the PS4, Xbox One, Steam, Bethesda Launcher and PC version of the game.

Luck Bobblehead: Spectacle Island: In a locker on the 2nd floor of a green boat

Agility Bobblehead: Wreck of the FMS North Star: On a wooden platform on the edge of the bow of the ship

Endurance Bobblehead: Poseidon Energy in Quincy: original release: On the central metal catwalk on a metal desk with a magazine near the steamer trunk | v1.12 update: It’s in a room near the central metal catwalk

Unarmed Bobblehead: Atom Cats Garage: On the hood of a rusty car in the main warehouse

Small Guns Bobblehead: Gunners Plaza: On the broadcast desk in the on-air room, ground floor, west side of the building

Big Guns Bobblehead: Vault 95: In the living quarters area, northernmost room, on a radio

Medicine Bobblehead: Curie’s Office in the Secret Vault in Vault 81: In the Secret Vault area, in Curie’s Office, south-west corner of the room on top of a table

Melee Bobblehead: Trinity Tower: On a table in the cage where Rex Goodman and Strong are being held captive

Intelligence Bobblehead: Boston Public Library: On top of the computer bank in the mechanical room, north-west corner of the library

Energy Weapons Bobblehead: Fort Hagen Command Center in Fort Hagen: South-west kitchens on a small table between two fridges

Speech Bobblehead: Overseer’s Office in Vault 114: On top of the Overseer’s Desk in the Overseer’s Office

Strength Bobblehead: Mass Fusion Building: add

Repair Bobblehead: Corvega Motors Assembly Plant in Lexington: add

Barter Bobblehead: Longneck Lukowski’s Cannery: add

Explosives Bobblehead: Saugus Ironworks: In the Blast Furnace area of the ironworks

Perception Bobblehead: Museum of Freedom, Concord: In the room where the settlers are holding up

Science Bobblehead: Vault 75

Charisma Bobblehead: Parson’s Insane Asylum: On a table in the room where you find Edward Deagan near the lift/elevator

Sneak Bobblehead: Dunwich Borers: add

Lock Picking Bobblehead: Pickman’s Gallery in the North End District of Boston: In the catacombs deep underground inside a secret section of the gallery

Changelog

2nd June 2024 at 7:00 am: Moved post to my Tumblr blog

10th June 2018 at 11:00 am: Updated post with new location of “Endurance Bobblehead” as of the recent update of v1.12

14th September 2015 at 9:00 am: Created post

#warrenwoodhouse#gaming#2024#2018#2015#fallout#fallout4#fallout 4#fo4#fallout 4 bobbleheads#bobbleheads fallout 4#lists#list#.list#gameguides#game guide#gameguide#game guides#guide#guides#.guide

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

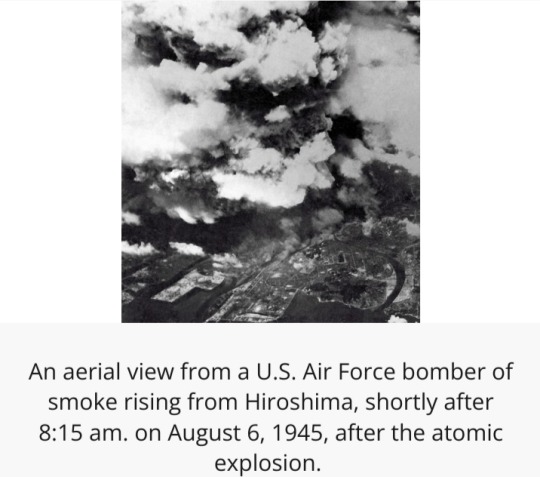

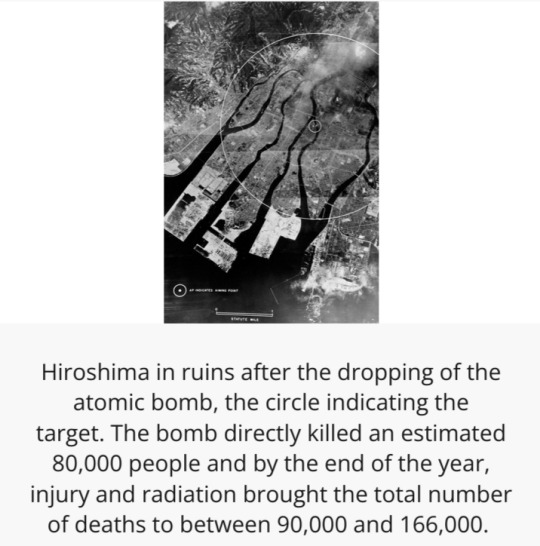

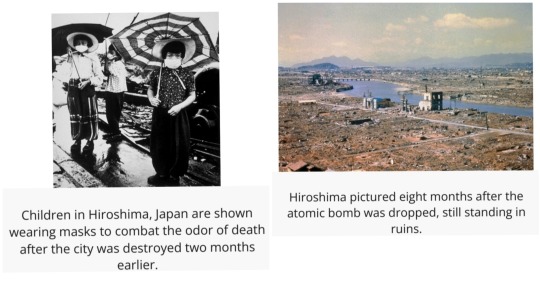

On 6 August 1945, during World War II (1939-45), an American B-29 bomber dropped the world’s first deployed atomic bomb over the Japanese city of Hiroshima.

The explosion immediately killed an estimated 80,000 people; tens of thousands more would later die of radiation exposure.

Three days later, a second B-29 dropped another A-bomb on Nagasaki, killing an estimated 40,000 people.

Japan’s Emperor Hirohito announced his country’s unconditional surrender in World War II in a radio address on August 15, citing the devastating power of “a new and most cruel bomb.”

The Manhattan Project

Even before the outbreak of war in 1939, a group of American scientists — many of them refugees from fascist regimes in Europe — became concerned with nuclear weapons research being conducted in Nazi Germany.

In 1940, the U.S. government began funding its own atomic weapons development program, which came under the joint responsibility of the Office of Scientific Research and Development and the War Department after the U.S. entry into World War II.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was tasked with spearheading the construction of the vast facilities necessary for the top-secret program, codenamed “The Manhattan Project” (for the engineering corps’ Manhattan district).

Over the next several years, the program’s scientists worked on producing the key materials for nuclear fission — uranium-235 and plutonium (Pu-239).

They sent them to Los Alamos, New Mexico, where a team led by J. Robert Oppenheimer worked to turn these materials into a workable atomic bomb.

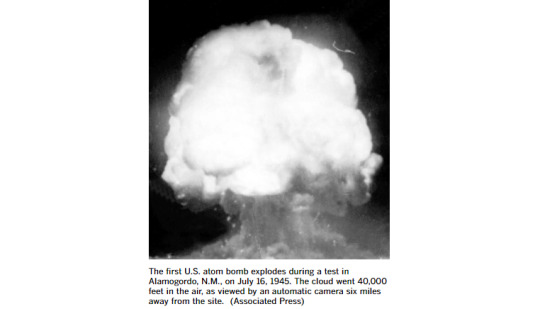

Early on the morning of 16 July 1945, the Manhattan Project held its first successful test of an atomic device — a plutonium bomb — at the Trinity test site at Alamogordo, New Mexico.

No Surrender for the Japanese

By the time of the Trinity test, the Allied powers had already defeated Germany in Europe.

Japan, however, vowed to fight to the bitter end in the Pacific, despite clear indications (as early as 1944) that they had little chance of winning.

In fact, between mid-April 1945 (when President Harry Truman took office) and mid-July, Japanese forces inflicted Allied casualties totaling nearly half those suffered in three full years of war in the Pacific, proving that Japan had become even more deadly when faced with defeat.

In late July, Japan’s militarist government rejected the Allied demand for surrender put forth in the Potsdam Declaration, which threatened the Japanese with “prompt and utter destruction” if they refused.

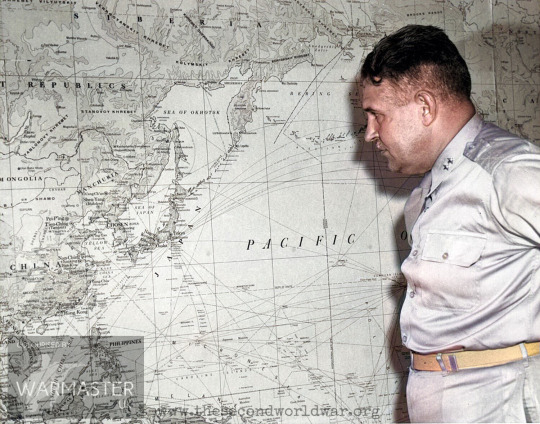

General Douglas MacArthur and other top military commanders favored continuing the conventional bombing of Japan already in effect and following up with a massive invasion, codenamed “Operation Downfall.”

They advised Truman that such an invasion would result in U.S. casualties of up to 1 million.

In order to avoid such a high casualty rate, Truman decided – over the moral reservations of Secretary of War Henry Stimson, General Dwight Eisenhower and a number of the Manhattan Project scientists – to use the atomic bomb in the hopes of bringing the war to a quick end.

Proponents of the A-bomb — such as James Byrnes, Truman’s secretary of state — believed that its devastating power would not only end the war but also put the U.S. in a dominant position to determine the course of the postwar world.

'Little Boy' and 'Fat Man' Are Dropped

Hiroshima, a manufacturing center of some 350,000 people located about 500 miles from Tokyo, was selected as the first target.

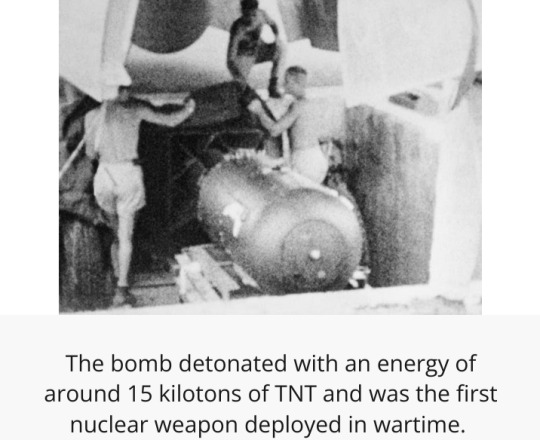

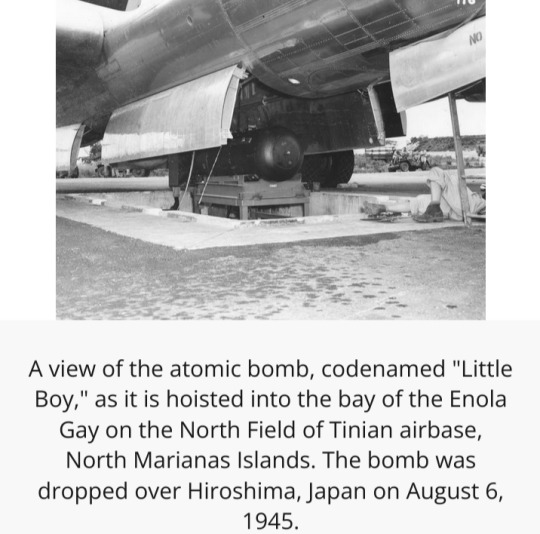

After arriving at the U.S. base on the Pacific island of Tinian, the more than 9,000-pound uranium-235 bomb was loaded aboard a modified B-29 bomber christened Enola Gay (after the mother of its pilot, Colonel Paul Tibbets).

The plane dropped the bomb — known as “Little Boy” — by parachute at 8:15 in the morning.

It exploded 2,000 feet above Hiroshima in a blast equal to 12-15,000 tons of TNT, destroying five square miles of the city.

Hiroshima’s devastation failed to elicit immediate Japanese surrender, however, and on August 9, Major Charles Sweeney flew another B-29 bomber, Bockscar, from Tinian.

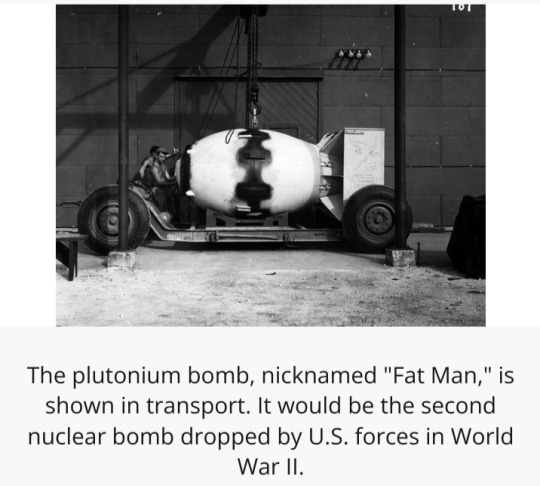

Thick clouds over the primary target, the city of Kokura, drove Sweeney to a secondary target, Nagasaki, where the plutonium bomb “Fat Man” was dropped at 11:02 that morning.

More powerful than the one used at Hiroshima, the bomb weighed nearly 10,000 pounds and was built to produce a 22-kiloton blast.

The topography of Nagasaki, which was nestled in narrow valleys between mountains, reduced the bomb’s effect, limiting the destruction to 2.6 square miles.

Aftermath of the Bombing

At noon on 15 August 1945 (Japanese time), Emperor Hirohito announced his country’s surrender in a radio broadcast.

The news spread quickly.

“Victory in Japan” or “V-J Day” celebrations broke out across the United States and other Allied nations.

The formal surrender agreement was signed on September 2, aboard the U.S. battleship Missouri, anchored in Tokyo Bay.

Because of the extent of the devastation and chaos — including the fact that much of the two cities' infrastructure was wiped out — exact death tolls from the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki remain unknown.

However, it's estimated roughly 70,000 to 135,000 people died in Hiroshima and 60,000 to 80,000 people died in Nagasaki, both from acute exposure to the blasts and from long-term side effects of radiation.

#Bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki (1945)#6 August 1945#atomic bomb#Hiroshima#Nagasaki#B-29 bomber#A-bomb#U.S. Army Corps of Engineers#The Manhattan Project#nuclear weapons research#Office of Scientific Research and Development#War Department#World War II#WWII#uranium-235#plutonium (Pu-239)#nuclear fission#plutonium bomb#J. Robert Oppenheimer#Oppenheimer#Trinity test#Potsdam Declaration#General Douglas MacArthur#Operation Downfall#Henry Stimson#General Dwight Eisenhower#Enola Gay#Colonel Paul Tibbets#Bockscar#V-J Day

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

The First Light of Trinity

— By Alex Wellerstein | July 16, 2015 | Annals of Technology

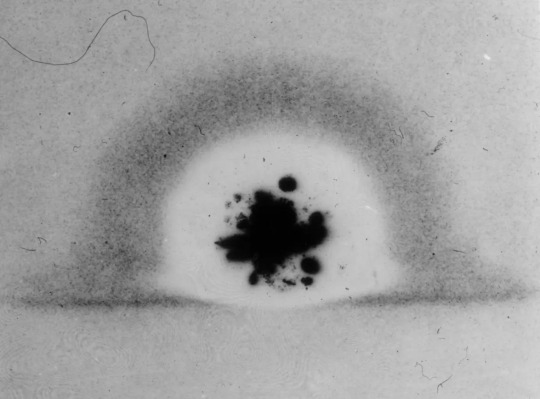

Seventy years ago, the flash of a nuclear bomb illuminated the skies over Alamogordo, New Mexico. Courtesy Los Alamos National Laboratory

The light of a nuclear explosion is unlike anything else on Earth. This is because the heat of a nuclear explosion is unlike anything else on Earth. Seventy years ago today, when the first atomic weapon was tested, they called its light cosmic. Where else, except in the interiors of stars, do the temperatures reach into the tens of millions of degrees? It is that blistering radiation, released in a reaction that takes about a millionth of a second to complete, that makes the light so unearthly, that gives it the strength to burn through photographic paper and wound human eyes. The heat is such that the air around it becomes luminous and incandescent and then opaque; for a moment, the brightness hides itself. Then the air expands outward, shedding its energy at the speed of sound—the blast wave that destroys houses, hospitals, schools, cities.

The test was given the evocative code name of Trinity, although no one seems to know precisely why. One theory is that J. Robert Oppenheimer, the head of the U.S. government’s laboratory in Los Alamos, New Mexico, and the director of science for the Manhattan Project, which designed and built the bomb, chose the name as an allusion to the poetry of John Donne. Oppenheimer’s former mistress, Jean Tatlock, a student at the University of California, Berkeley, when he was a professor there, had introduced him to Donne’s work before she committed suicide, in early 1944. But Oppenheimer later claimed not to recall where the name came from.

The operation was designated as top secret, which was a problem, since the whole point was to create an explosion that could be heard for a hundred miles around and seen for two hundred. How to keep such a spectacle under wraps? Oppenheimer and his colleagues considered several sites, including a patch of desert around two hundred miles east of Los Angeles, an island eighty miles southwest of Santa Monica, and a series of sand bars ten miles off the Texas coast. Eventually, they chose a place much closer to home, near Alamogordo, New Mexico, on an Army Air Forces bombing range in a valley called the Jornada del Muerto (“Journey of the Dead Man,” an indication of its unforgiving landscape). Freshwater had to be driven in, seven hundred gallons at a time, from a town forty miles away. To wire the site for a telephone connection required laying four miles of cable. The most expensive single line item in the budget was for the construction of bomb-proof shelters, which would protect some of the more than two hundred and fifty observers of the test.

The area immediately around the bombing range was sparsely populated but not by any means barren. It was within two hundred miles of Albuquerque, Santa Fe, and El Paso. The nearest town of more than fifty people was fewer than thirty miles away, and the nearest occupied ranch was only twelve miles away—long distances for a person, but not for light or a radioactive cloud. (One of Trinity’s more unusual financial appropriations, later on, was for the acquisition of several dozen head of cattle that had had their hair discolored by the explosion.) The Army made preparations to impose martial law after the test if necessary, keeping a military force of a hundred and sixty men on hand to manage any evacuations. Photographic film, sensitive to radioactivity, was stowed in nearby towns, to provide “medical legal” evidence of contamination in the future. Seismographs in Tucson, Denver, and Chihuahua, Mexico, would reveal how far away the explosion could be detected.

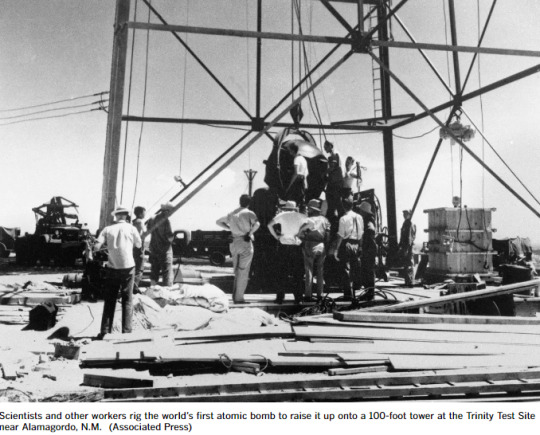

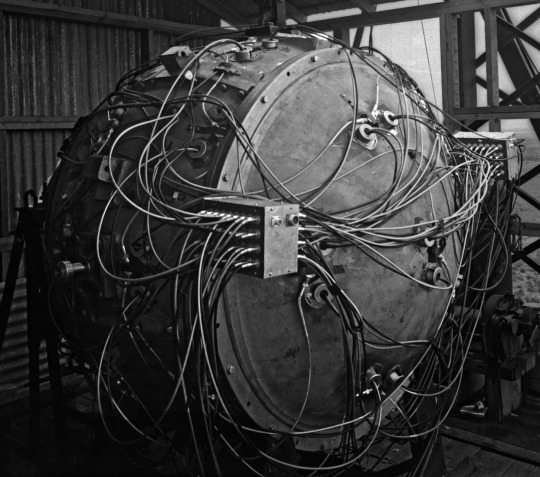

The Trinity test weapon. Courtesy Los Alamos National Laboratory

On July 16, 1945, the planned date of the test, the weather was poor. Thunderstorms were moving through the area, raising the twin hazards of electricity and rain. The test weapon, known euphemistically as the gadget, was mounted inside a shack atop a hundred-foot steel tower. It was a Frankenstein’s monster of wires, screws, switches, high explosives, radioactive materials, and diagnostic devices, and was crude enough that it could be tripped by a passing storm. (This had already happened once, with a model of the bomb’s electrical system.) Rain, or even too many clouds, could cause other problems—a spontaneous radioactive thunderstorm after detonation, unpredictable magnifications of the blast wave off a layer of warm air. It was later calculated that, even without the possibility of mechanical or electrical failure, there was still more than a one-in-ten chance of the gadget failing to perform optimally.

The scientists were prepared to cancel the test and wait for better weather when, at five in the morning, conditions began to improve. At five-ten, they announced that the test was going forward. At five-twenty-five, a rocket near the tower was shot into the sky—the five-minute warning. Another went up at five-twenty-nine. Forty-five seconds before zero hour, a switch was thrown in the control bunker, starting an automated timer. Just before five-thirty, an electrical pulse ran the five and a half miles across the desert from the bunker to the tower, up into the firing unit of the bomb. Within a hundred millionths of a second, a series of thirty-two charges went off around the device’s core, compressing the sphere of plutonium inside from about the size of an orange to that of a lime. Then the gadget exploded.

General Thomas Farrell, the deputy commander of the Manhattan Project, was in the control bunker with Oppenheimer when the blast went off. “The whole country was lighted by a searing light with the intensity many times that of the midday sun,” he wrote immediately afterward. “It was golden, purple, violet, gray, and blue. It lighted every peak, crevasse, and ridge of the nearby mountain range with a clarity and beauty that cannot be described but must be seen to be imagined. It was that beauty the great poets dream about but describe most poorly and inadequately.” Twenty-seven miles away from the tower, the Berkeley physicist and Nobel Prize winner Ernest O. Lawrence was stepping out of a car. “Just as I put my foot on the ground I was enveloped with a warm brilliant yellow white light—from darkness to brilliant sunshine in an instant,” he wrote. James Conant, the president of Harvard University, was watching from the V.I.P. viewing spot, ten miles from the tower. “The enormity of the light and its length quite stunned me,” he wrote. “The whole sky suddenly full of white light like the end of the world.”

In its first milliseconds, the Trinity fireball burned through photographic film. Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration

Trinity was filmed exclusively in black and white and without audio. In the main footage of the explosion, the fireball rises out of the frame before the cameraman, dazed by the sight, pans upward to follow it. The written accounts of the test, of which there are many, grapple with how to describe an experience for which no terminology had yet been invented. Some eventually settle on what would become the standard lexicon. Luis Alvarez, a physicist and future participant in the Hiroshima bombing, viewed Trinity from the air. He likened the debris cloud, which rose to a height of some thirty thousand feet in ten minutes, to “a parachute which was being blown up by a large electric fan,” noting that it “had very much the appearance of a large mushroom.” Charles Thomas, the vice-president of Monsanto, a major Manhattan Project contractor, observed the same. “It looked like a giant mushroom; the stalk was the thousands of tons of sand being sucked up by the explosion; the top of the mushroom was a flowering ball of fire,” he wrote. “It resembled a giant brain the convolutions of which were constantly changing.”

In the months before the test, the Manhattan Project scientists had estimated that their bomb would yield the equivalent of between seven hundred and five thousand tons of TNT. As it turned out, the detonation force was equal to about twenty thousand tons of TNT—four times larger than the expected maximum. The light was visible as far away as Amarillo, Texas, more than two hundred and eighty miles to the east, on the other side of a mountain range. Windows were reported broken in Silver City, New Mexico, some hundred and eighty miles to the southwest. Here, again, the written accounts converge. Thomas: “It is safe to say that nothing as terrible has been made by man before.” Lawrence: “There was restrained applause, but more a hushed murmuring bordering on reverence.” Farrell: “The strong, sustained, awesome roar … warned of doomsday and made us feel that we puny things were blasphemous.” Nevertheless, the plainclothes military police who were stationed in nearby towns reported that those who saw the light seemed to accept the government’s explanation, which was that an ammunition dump had exploded.

Trinity was only the first nuclear detonation of the summer of 1945. Two more followed, in early August, over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, killing as many as a quarter of a million people. By October, Norris Bradbury, the new director of Los Alamos, had proposed that the United States conduct “subsequent Trinity’s.” There was more to learn about the bomb, he argued, in a memo to the new coördinating council for the lab, and without the immediate pressure of making a weapon for war, “another TR might even be FUN.” A year after the test at Alamogordo, new ones began, at Bikini Atoll, in the Marshall Islands. They were not given literary names. Able, Baker, and Charlie were slated for 1946; X-ray, Yoke, and Zebra were slated for 1948. These were letters in the military radio alphabet—a clarification of who was really the master of the bomb.

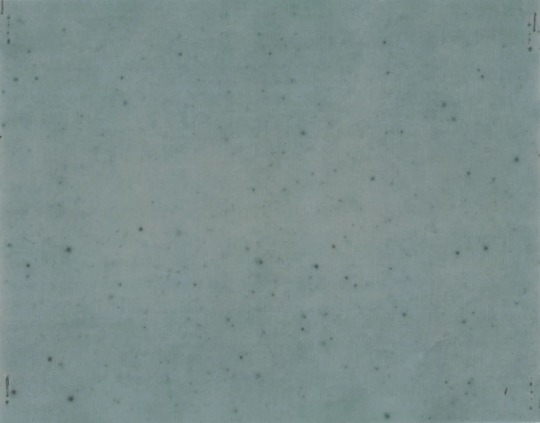

Irradiated Kodak X-ray film. Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration

By 1992, the U.S. government had conducted more than a thousand nuclear tests, and other nations—China, France, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union—had joined in the frenzy. The last aboveground detonation took place over Lop Nur, a dried-up salt lake in northwestern China, in 1980. We are some years away, in other words, from the day when no living person will have seen that unearthly light firsthand. But Trinity left secondhand signs behind. Because the gadget exploded so close to the ground, the fireball sucked up dirt and debris. Some of it melted and settled back down, cooling into a radioactive green glass that was dubbed Trinitite, and some of it floated away. A minute quantity of the dust ended up in a river about a thousand miles east of Alamogordo, where, in early August, 1945, it was taken up into a paper mill that manufactured strawboard for Eastman Kodak. The strawboard was used to pack some of the company’s industrial X-ray film, which, when it was developed, was mottled with dark blotches and pinpoint stars—the final exposure of the first light of the nuclear age.

#Hiroshima | Japan 🇯🇵 | John Donne | Manhattan Project | Monsanto#Nagasaki | Japan 🇯🇵 | Nuclear Weapons | Second World War | World War II#The New Yorker#Alex Wellerstein#Los Alamos National Laboratory#New Mexico#J. Robert Oppenheimer#John Donne#Jean Tatlock#University of California Berkeley#Jornada del Muerto | Journey of the Dead Man#General Thomas Farrell#Nobel Prize Winner Physicist Ernest O. Lawrence#Luis Alvarez#US 🇺🇸#China 🇨🇳#France 🇫🇷#Soviet Union (Now Russia 🇷🇺)#Alamogordo | New Mexico#Eastman Kodak#Nuclear Age

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

From Reddit:

At 5:30 AM on July 16, 1945, thirteen-year-old Barbara Kent was on a camping trip with her dance teacher and 11 other students in Ruidoso, New Mexico, when a forceful blast threw her out of her bunk bed onto the floor.

Later that day, the girls noticed what they believed was snow falling outside. Surprised and excited, Kent recalls, the young dancers ran outside to play. “We all thought ‘Oh my gosh,’ it’s July and it’s snowing … yet it was real warm,” she said. “We put it on our hands and were rubbing it on our face, we were all having such a good time … trying to catch what we thought was snow.”

Years later, Kent learned that the “snow” the young students played in was actually fallout from the first nuclear test explosion in the United States (and, indeed, the world), known as Trinity. Of the 12 girls that attended the camp, Kent is the only living survivor. The other 11 died from various cancers, as did the camp dance teacher and Kent’s mother, who was staying nearby.

Diagnosed with four different types of cancers herself, Kent is one of many people in New Mexico unknowingly exposed to fallout from the explosion of the first atomic bomb. In the years following the Trinity test, thousands of residents developed cancers and diseases that they believe were caused by the nuclear blast.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Amid a desert landscape a visionary unveils an invention that will forever change the world as we know it.

That’s the climactic scene of the Christopher Nolan biopic Oppenheimer, about the eponymous J. Robert Oppenheimer, the “father of the atomic bomb.” It’s also the opening scene of the Barbie movie, directed and co-written by indie auteur Greta Gerwig, which opened on the same day as Oppenheimer.

Despite the two films’ radically different subject matter and tone—one a dramatic examination of man’s hubris and the threat of nuclear apocalypse and the other a neon-drenched romp about Mattel’s iconic fashion doll—they have far more in common than just their release date. Both movies consider the complicated legacies of two American icons and how to grapple with and perhaps even atone for them.

In Oppenheimer, the desert scene depicts the Trinity test, the world’s first detonation of a nuclear bomb near Los Alamos, New Mexico, on July 16, 1945. A brilliant but flawed theoretical physicist and the rest of his team work frantically to develop the weapon for the United States before the Nazis can beat them to the punch; they then gather on bleak, lunar-white sands near their secret laboratory to test the terrifying creation.

The countdown timer ticks to 00:00:00, the proverbial big red button is pushed, and a blast ignites the sky—a blinding white flash that quickly morphs into a towering inferno. Everything goes silent as Oppenheimer stares in awe from behind a makeshift protective barrier at what he has created.

Suddenly, he begins experiencing flashes of a different kind, premonitions of the human horror and suffering his weapon will wreak. Nolan is unambiguously signaling to the audience that this is a pivotal moment for the world, and for Oppenheimer personally, as what was once merely a theoretical idea has become monstrously real. The fallout, both literally and figuratively, will be out of Oppenheimer’s control.

Barbie’s critical desert scene comes not at the film’s climax but at its very beginning. The movie opens with a parody of the famous “The Dawn of Man” scene from Stanley Kubrick’s classic 1968 science fiction film, 2001: A Space Odyssey. As a red-orange sunrise breaks across a rocky desert landscape, a voiceover (from none other than Dame Helen Mirren) begins: “Since the beginning of time, since the first little girl ever existed, there have been dolls. But the dolls were always and forever baby dolls.” On screen, underscored by the ominous notes of Richard Strauss’s “Also Sprach Zarathustra,” little girls sit amid dusty canyon walls playing with baby dolls.

“Until���” Mirren says. And then comes the reveal: The little girls look up to see a massive, monolith-sized Margot Robbie, dressed in the black and white-striped swimsuit of the very first Barbie doll. She lifts her sunglasses and winks. The little girls are stunned—and, like the apes in the classic sci-fi movie, they begin to angrily dash their baby dolls against the ground.

This is Barbie’s mythic origin story: Once upon a time, little girls could only play with baby dolls meant to socialize them into wanting to be good wives and, eventually, mothers. Then came Ruth Handler, who in 1959 decided to create a doll with an adult woman’s body, adult women’s fashions, and adult women’s careers so that little girls could dream of being more than just wives and mothers. And the rest is history. Thanks to such iterations as doctor Barbie, chef Barbie, scientist Barbie, professional violinist Barbie, and beyond, Barbie opened up young girls to a world of possibilities and, Mirren says, “All problems of feminism and equal rights [were] solved.”

Well, not so fast: Mirren adds one final, snarky beat: “At least,” she says, “that’s what the Barbies think.”

Thus Gerwig introduces the central tension that animates the movie: Handler set out to create a feminist toy to empower and inspire young girls. But we sitting in the audience in 2023 know that things worked out a little differently. In the intervening years, Barbie would come under fire from feminists and other critics for a whole host of sins: encouraging unrealistic and harmful beauty standards that contribute to negative body image issues, eating disorders, and depression among pre-adolescent girls; lacking diversity and perpetuating white supremacy, ableism, and heteronormativity; objectifying women; promoting consumerism and capitalism; and even contributing to greenhouse gas emissions.

And here is the core parallel between Barbie and Oppenheimer: Two iconic American creators who ostensibly meant well but whose creations caused irreparable harm. And two iconic American directors (Nolan is British-American) who set out to tell their stories from a very modern perspective, humanizing them while also addressing their harmful legacies.

But while Nolan obviously had the much harder task—no matter how much harm you think Barbie has done to the psyches of young girls over the years, there’s simply no comparison to the human toll of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the environmental impact of decades of nuclear testing, or the cost of the nuclear arms race—oddly enough, it’s Gerwig who ends up taking her job of atonement far more seriously.

As its opening scene shows, the Barbie movie lets the audience know right from the start that it’s self-aware. It knows that Barbie is problematic. And it’s going to go there.

And it does—almost to the point of overkill. The basic plot of the movie is this: Barbie is living happily in Barbie Land, a perfect pink plastic world where she and her fellow Barbies run everything from the White House to the Supreme Court and have everything they could ever want, from dream houses to dream cars to dreamy boyfriends (Ken)—the last of which they treat as little more than accessories.

But suddenly, things start to go wrong in Barbie’s happy feminist utopia, and to fix it, she is forced to journey into the real world—our world—accompanied by Ken, who insists on going with her. When she does, she realizes that contrary to what she believed (as Mirren told us in the opening scene), the invention of Barbies didn’t solve gender inequality in the real world. In the real world, Barbie is confronted not only with the dominance of the patriarchy (she discovers, for instance, that Mattel’s CEO is a man, played by Will Ferrell), but also with the fact that young girls seem to hate her.

In a crucial early scene, Robbie’s Barbie encounters ultracool Gen-Z teen Sasha (played by Ariana Greenblatt), who delivers a scathing monologue about everything that’s wrong with Barbie, the doll and cultural symbol—basically a checklist of all the criticisms lobbed at Barbie over the years, from promoting unrealistic beauty standards to destroying the planet with rampant capitalism. Barbie is crestfallen.

Meanwhile, there’s a subplot involving Ken’s parallel discovery of patriarchy, and how awesome and different it seems to be from his subjugated life in Barbie Land. Ken proceeds to go full men’s rights, heading back to Barbie Land and seizing power. He transforms Barbie’s dream house into Ken’s Mojo Dojo Casa House, where Barbies serve men and “every night is boys’ night!”

Barbie enlists the help of Sasha and her mom (played by America Ferrera)—a Mattel employee who secretly dreams up ideas for new, more realistic Barbies such as anxiety Barbie—to unseat Ken and restore female power in Barbie Land. Along the way, Ferrera’s character delivers the film’s other major feminist monologue, about how hard it is being a woman in the real world.

The monologues are unsubtle, as are the repeated mentions of concepts like the patriarchy. In every scene and nearly every line, the movie hits the audience over the head with the pro-feminism message. Gerwig knows what her job is—to atone for Barbie’s sins (and, yes, help Mattel sell more dolls)—and she makes sure everyone knows that she has fully understood the assignment.

But it’s in the film’s quieter, more tender moments that Gerwig’s background as an indie filmmaker and her true talent shine through, and where she’s able to communicate the message in a subtler, but ultimately more impactful, way. The scene where Barbie in the real world sees an elderly woman for the first time (old people and wrinkles don’t exist in Barbie Land, obviously) and is stunned at how beautiful she is, wrinkles and all. Or the scenes where Barbie talks quietly with her deceased creator, an elderly Handler (played by Rhea Perlman), who explains that the name Barbie was an homage to Handler’s daughter, Barbara, who inspired her to make the doll.

The overall result is a movie that, even if a bit ham-fisted in its over-the-top messaging, doesn’t shy away from the uglier parts of Barbie’s legacy. It looks them right in the face, wrinkles and all.

I said above that the Trinity test scene is the climactic scene in Oppenheimer, but that’s not really the case. For a movie about the complicated life and legacy of the man credited with creating the world’s most destructive weapon, it should be the climax. You might imagine it would follow with a denouement of the inventor confronting the reality that his creation is used to kill tens of thousands of Japanese civilians and sparks an arms race that threatens to destroy all of humanity.

These scenes are in there, but they are given short shrift next to the other story Nolan wants to tell: that of how Oppenheimer, once considered an American hero, was mistreated by his country in the postwar years. As McCarthy-era fears of communist infiltration grip the country, Oppenheimer’s previous ties to the Communist Party (he never joined the party himself, but he had close family members and friends who were members, and he supported various left-wing causes) are mysteriously brought to the FBI’s attention despite already being well documented. His security clearance is revoked, and his career working with the U.S. government on nuclear issues ends.

It is this storyline—not the apocalyptic destruction of two Japanese cities—that is given the most pathos. Much of the movie’s three-hour run time—and nearly all of its third act—centers on what we are clearly meant to see as the great evil that was done to this man who did so much for his country. The real climax of the film is not the Trinity test, nor even the bombings of Japan (which are not even shown in the movie), but rather the moment we learn who betrayed Oppenheimer by handing over his security file to the FBI.

This is the shocking revelation that is meant to induce gasps in the audience, not the images of charred and irradiated bodies. In fact, those images aren’t even shown to us, the viewers. In the scene where Oppenheimer and his team are shown photos of the aftermath of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the camera stays tight on Oppenheimer’s face as he reacts to the images—a reaction that consists of him putting his head down to avoid seeing them.

It is an act of cowardice on Oppenheimer’s part, yes, but also on Nolan’s. Indeed, the only glimpses we get of the macabre effects of the atom bomb take place in Oppenheimer’s fevered imagination, and even then, they are brief flashes used for shock value: skin flapping off the beautiful face of an admiring female colleague; the charred, faceless husk of a child’s body Oppenheimer accidentally steps on; a male colleague vomiting from the effects of radiation. Of the Japanese victims, there is nothing. They remain theoretical, faceless.

Nolan has said that he chose not to depict the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki not to sanitize them but because the film’s events are shown from Oppenheimer’s point of view. “We know so much more than he did at the time,” Nolan said at a screening of the movie in New York. “He learned about the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on the radio, the same as the rest of the world.”

But in reading the numerous interviews he’s given about the movie, it’s also clear that Nolan fundamentally sees Oppenheimer as a tragic hero—Nolan has repeatedly called Oppenheimer “the most important person who ever lived”—and Oppenheimer’s story as a distinctly American one. “I believe you see in the Oppenheimer story all that is great and all that is terrible about America’s uniquely modern power in the world,” he told the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. “It’s a very, very American story.”

That Nolan’s film devotes so much runtime to Oppenheimer’s point of view and how he was tragically betrayed by his country is partly due to the fact that the film is not an original story but rather an adaptation of the Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of the great scientist, American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer. That book also places Oppenheimer being stripped of his security clearance at its center. But that didn’t mean Nolan had to do the same in his adaptation. That was a choice. And the end result is what military technology writer Kelsey Atherton aptly described as “a 3 hour long argument that the greatest victim of atomic weaponry was Oppenheimer’s clearance.”

At a time when Americans are struggling to reckon with their country’s past and how it has shaped the present—from fights over how (or even whether) to teach children about the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow; to debates, including in these very pages, over the role (or lack thereof) of NATO expansion in Russia’s decision to wage war on Ukraine; to retrospectives on the myriad failures of the U.S. war in Afghanistan; and beyond—the fact that the two biggest films in theaters right now are attempting to confront the legacies of two American icons, the nuclear bomb and Barbie, is understandable and perhaps even impressive.

But the impulse to look away from the ugliest parts of those legacies remains strong, and Oppenheimer never fully faces them.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Secrecy and Deception Chapter 3

Untold Power (Wattpad | Ao3)

Table of Contents | Prev | Next

Event: Atomic Bombing of Hiroshima

Location: Hiroshima, Empire of Japan

Date: August 6, 1945

New Mexico was nervous. It was happening. The weapon created and tested in her state would finally be used. She was sitting in a plane with the people meant to observe the blast, waiting anxiously for the moment to arrive.

The deadliest weapon humanity has ever seen was about to be used. Why did everything have to come to this? Why couldn’t Japan see that this war was hopeless and spare the lives of her people?

Not that there was much she could do. Little Boy was going to be dropped on the city of Hiroshima very soon.

New Mexico had seen what the first bomb at the Trinity Test had done. What was this one going to do to this city?

She wished it didn’t have to come to this, that more civilians didn’t have to be caught in the crossfire. But still, this was to save her people’s lives and the lives of the Americans fighting this war.

Each island we took was taken with a high price in American lives. They were so bloody and went on for so long. As soon as their invasion troops landed, the Japanese were planning on executing all American prisoners. It would be the deadliest battle they’ve fought so far.

This was the best way. People would die, but more of their people would live. Japan would surrender, and the war would finally be over. They wouldn’t have to fight costly battles for the main Japanese islands. However, if Japan refused to surrender even after these bombs were dropped, Operation Downfall would commence.

At least, that was the justification that New Mexico was using to pretend like she didn’t know what the weapon was really being used for.

Truth be told, she knew many men in the military thought this was a drastic action, that it was unnecessary. She knew part of this was happening as an intimidation attempt against the USSR to get him to back down, was being used as a test on the people of Hiroshima, but…she didn’t know how she felt.

She had been the first test subject. Should she feel sympathy for the second?

“Miss, the bomb is about to be dropped,” one of the men on the plane said. New Mexico nodded, looking out the plane’s window at the Enola Gay, the plane carrying the bomb, before looking down at the city. The city had been picked because it contained the headquarters of the Japanese army defending the island of Kyushu and war industries.

Nex Mexico exhaled. They were really doing this. They would fulfill Papa, Britain, and China's promise at Potsdam: unconditional surrender or prompt and utter destruction.

Japan had not surrendered, so it was time to tell them exactly how serious they were about destroying her.

It was 8:15 am, and Enola Gay dropped one of the deadliest weapons humanity had ever created. Instantly, the plane jumped a decent amount of feet due to the sudden loss of weight as the bomb was released.

Enola Gay quickly turned around, trying to get out of the blast zone, as they weren’t sure if the plane would survive the shockwaves from the explosion.

The bomb exploded in a brilliant flash of light, and shockwaves began shaking the plane so violently, in fact, that New Mexico feared that they might be knocked out of the sky. She turned her head back towards Hiroshima, having looked away when the shockwaves hit the plane.

A giant purple mushroom cloud surrounded the city. Fires and smoke were on the ground. New Mexico couldn’t see the city. But then again, who even knew if it was left?

Hiroshima was the first city to experience an atomic bombing.

And if Japan didn’t surrender, it wouldn’t be the last.

—

Event: Soviet Declares War on Japan

Location: The Far East, Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

Date: August 8, 1945

“We’ve declared war. The invasion starts tomorrow.”

Tomorrow was in less than an hour. Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic was nervous.

Soviet had finally fulfilled his promise to America at the Yalta Conference and declared war on Japan, which hopefully came as a great surprise to her.

Just like America’s new weapon had.

Soviet was upset about America not informing him of the nuclear bomb. They already knew about the nuclear bomb. They had spies who had figured it out before America even implied its existence at the Potsdam Conference.

They were aware of what it could do. America claimed he trusted them, but he didn’t tell anyone about him figuring out the nuclear bomb.

It was worrying, to say the least.

Russian SFSR shook the thoughts of America out of his head. It wasn’t the time to think about him; that was Soviet’s job. His job was to fight with these forces, invade Manchuria, take the Kuril Islands, take South Sakhalin, Port Arthur, Hokkaido, and occupy Northern Korea.

They had many goals in Asia, even though most of their goals remained in Europe.

There was worry about America and his nuclear bombs, but Russian SFSR and his family would create their own. They wouldn’t let America be the only nuclear power for long.

Why did Russian SFSR keep thinking about America? That wasn’t his concern.

He was supposed to be worried about Japan. Russian SFSR sighed. He guessed the threat of a bomb that could wipe out a city was more concerning than going into battle against an enemy that, according to America, Britain, and China, would not surrender easily.

Why was he more worried about an ally than an enemy, even if America would one day have to become an enemy?

It was the ninth of August now, Russian SFSR noted, looking at the time. The invasion was planned for one in the morning. Japan was told they were going to invade tomorrow. Of course, tomorrow for Moscow and tomorrow here were very different. Hopefully, that would give them a very advantageous element of surprise, and hopefully, they would complete their goals before America used any more of his bombs.

They needed influence here just as much as they needed influence in Europe. And if America got her to surrender before they even got a chance to be involved, anything they could do here would be severely limited.

Maybe Russian SFSR was too worried about America, but even if America was their ally now, and Soviet and America wanted to remain allies, something would go wrong eventually. America was not a man they needed as an enemy right now.

But Russian SFSR doesn’t think that is going to happen anytime soon. Despite America not telling Soviet about the nuclear bombs he had developed, he was still an important ally, and would remain that way until something between them went wrong.

Or until they stopped needing him.

Whichever came first.

———————

Event: Atomic Bombing of Nagasaki

Location: Kyūshū, Empire of Japan

Date: August 10, 1945

Nihon didn’t think the Allies were going to invade now. She was with the ground forces that would be defending Kyūshū, and they were prepared to fight if they did, but still…after that nuclear bomb Beikoku had used, Nihon didn’t think they would invade until they had exhausted their supply.

And who knew how many they had? Nihon didn’t even know Beikoku had actually built a working nuclear bomb. She thought Beikoku was still in the scientific investigation stage. But Nihon was so very wrong. She wanted the Allies to invade! She would much rather fight off an invasion again than deal with that bomb. She would rather die honorably fighting her enemies than being forced to surrender to her enemies.

Surrender to the person that made her Sakura want to die.

If Beikoku used another one of those bombs, her government would likely surrender—and they couldn’t. Dai Nihon Teikoku could never surrender to the Western Nations!

Still, if these nuclear bombing attacks continued, Nihon might not be left with much of a choice, no matter how much she hated it. If only her attacks at Pearl Harbor and Midway had been more effective. Instead, Beikoku’s carriers were safe and ended up destroying her carriers, and Sakura was still securely in Beikoku’s hands. Nihon scowled. Hopefully, Beikoku had used his only nuclear bomb in an effort to get her to surrender.

But if he hadn’t…Nihon didn't want to think about that.

Then Nihon received the news—that Beikoku had dropped a second bomb. Nihon knew what this meant.

Nihon’s government was going to make her surrender.

———————

Event: VJ Day

Location: Washington, District of Columbia, United States of America

Date: August 15, 1945

“Dad, guess what?” District of Columbia said, throwing open the doors to her father's room.

“I can finally get out of this wheelchair?” Dad asked. I shook my head, and my mouth started to hurt from the smile.

“No! Japan surrendered!” DC exclaimed. Dad looked excited to hear that.

“Oh, thank god it’s over,” Dad said, relief in his voice as the tension that had been there since the war started drained out to him, though some remained. “It’s finally over.”

“Well, for now. We still have to wait for Japan to surrender officially. Then there is the matter of occupying Japan and her former colonies and possessions, the promise we made to Phil about his independence, your injury, Oklahoma’s injuries, North Dakota’s injury, Alaska telling Soviet, the introduction of nuclear weapons, and the issues President Truman had with Soviet but—” DC started rambling, thinking about all of the issues they were going to have to deal with now. Dad groaned.

“Dee, I appreciate you reminding me of all the problems I have to deal with, but can you please not remind me about all the problems I have to deal with? I need a break, and the war’s over. One day to relax, especially since most of your siblings aren’t here.” Dad said.

“Stop complaining about the wheelchair. Then I’ll stop talking about the things you need to do.” DC offered.

“I sincerely hope you will help me do some of those things. Also, the only way I will not complain about this chair is if you get me out of it,” Dad said. DC rolled her eyes.

“You’ll be out of it by the end of the month. Stop complaining before I make it take longer,” she said. Dad laughed.

“Are you threatening to make it worse?” He asked, amusement in his voice. DC smiled and nodded. Dad laughed again.

“There is a reason we fear Dee, Dad,” Massachusetts said as he walked up behind DC, using her head as an armrest.

“Kindly fuck off, dear sister,” DC said, pushing Massachusetts' arm off her head. Dad started laughing at them as Massachusetts rolled his eyes.

“I’d rather say West is my favorite sister than do that. I’m supposed to be babysitting Dad, remember?” Massachusetts responded. Dad groaned.

“Ginny, I don't need a babysitter. Why don’t you go celebrate with anyone else who’s here?” Dad asked. Massachusetts snorted and walked over to grab the handles of Dad’s wheelchair. “Hey, what are you doing?”

“The public wants to see you. And by the public, I mean some of the states.” Massachusetts said, pushing him out of the room.

“Oh, thank god it’s not the actual public; otherwise, I’d be running away no matter how bad my leg is,” Dad said. DC snorted. Their people could be a little… over-enthusiastic, to say the least.

“They aren’t that bad,” Massachusetts said.

“They can be very…very enthusiastic people, in good and bad ways. But they have an excuse to be enthusiastic now. It’s over! Finally!” Dad said, raising his hands in the air. DC smiled at Dad’s antics before Massachusetts pushed him out of the room.

She was glad things were finally looking up.

———————

Event: Official Surrender of Japan

Location: USS Missouri, Tokyo Bay, Empire of Japan

Date: September 2, 1945

There were two great things about this day. One, Japan was officially surrendering, which was going to formally end this godforsaken war. Two, it was the second day America was out of the wheelchair, and he loved it. Sure, he was still on crutches, but that was a big step up from the wheelchair.

“I’m glad this is over,” Australia said, drumming her fingers on the table.

“That’s what I’ve been saying since August. Along with ‘when am I allowed out of the wheelchair?’” America replied.

“I can’t believe your government gave you a babysitter to make you stay in your wheelchair,” Netherlands said. America shrugged.

“Apparently, I’m too stubborn to listen to what people tell me to do,” America said.

“You are.” Dad and Canada said. America rolled his eyes.

“You fight in one War of Independence, and no one lets you forget it,” America said, smiling slightly.

“Ame, you’ve told me you sometimes call the War of 1812 the Second American War of Independence.” Canada pointed out.

“Really?” Dad asked.

“I know for a fact you and at least twelve other European countries were making bets on how long my government would last and when I would be returned as your colony. Don’t act like you're surprised.” America said.

“You were taking bets on when he would collapse? Seriously?” China asked amusement in her voice.

“You are very confusing.” General MacArthur said as he and the other humans here were listening to their conversation. America shrugged. It was a fair point.

“I know my mother bet ten livres,” France said, causing America to give her a confused look. It was nice to know his allies had faith in him after helping America with the war in the first place. Then again, most Frenchmen who helped America in his Revolution were somewhat elitist.

“None of you were taking bets on how long I would last, were you?” Soviet asked. America laughed, knowing full well that they were taking bets as he was invited to participate. Soviet looked annoyed, probably taking America’s laugh as a yes.

“It’s a European tradition,” Dad said, trying to defend himself.

“You guys have weird traditions.” New Zealand said.

“It’s Europe.” Australia, Canada, China, and America said.

“Thank you. I’m glad you think so highly of our continent.” Netherlands said sarcastically.

“You’re welcom—” Australia began before she noticed something, and they turned to where she was looking. They saw Japan standing there with her people, having just arrived. Japan kept her face blank, but you could still see anger in her eyes, anger which was reflected by many other allied nations.

“Rì běn,” China said, hatred in her voice.

“Chūgoku,” Japan responded, an emotion that America couldn’t place in her voice. It seemed like it could be hatred, but it was hard to tell. Netherlands crossed his arms.

“Can we start the signing now?” he asked. General MacArthur nodded and gestured for the Japanese officials with Japan to come forward and directed them to the felt-covered table they needed to sit at. On top of the table was the canvas back book for the Japanese to have and the leather-backed version for the Allies to have. That was what the humans were signing. The countries had their own set of books in front of them.

This was the first signing America had attended with humans. Normally, humans and countries do it separately, as they had done with Germany. America didn’t really know why they did it like that, but it’s always been a thing. But this was a boat, so they didn’t have that luxury this time.

Japan was still staring off to the side, having not approached the table we were at.

“Japan, just come here so we can get this over with,” America said, picking up his pen and spinning it in his fingers until Australia snatched it from his hand. America gave her an annoyed look and stole her pen. Australia smiled and grabbed the two books containing the surrender documents before signing her name on both of them.

Japan then walked over and sat opposite them; none wanted to sit beside her. Australia passed her the books.

“Sign,” Australia said, giving her America’s pen. Japan took it and looked at Australia with loathing before signing her name, looking like it was painful for her to do so. Maybe it was, or perhaps she just hated having to surrender.

America heard France let out a sigh of relief as Japan signed.

“I’ll sign next,” Soviet said, so Netherlands passed the books to him.

“You betrayed me,” Japan said, turning to Soviet. He shrugged.

“I made a promise to America and Britain. I wasn’t going to back out of it,” he said, giving the books back to Netherlands, who signed them.

“Yes, thanks for keeping that promise, Soviet,” America said as Dad took the books and signed them before passing them to him. Japan’s fist clenched, and her face twisted in anger.

“Are you okay?” America asked, signing his name before passing the books to Canada.

“Don’t act like you care,” Japan said. America shrugged.

“Figure, I’d ask. After all, we aren't at war anymore.” America said as France signed the documents. China quickly took it from her, signing her name before passing it to New Zealand. New Zealand signed it, officially completing the surrender. Japan glared at America but sighed, looking away. It was odd to see that some of the fight had been drained out of her.

Maybe America would figure out exactly why later. But for now, he was content with not knowing. The war was officially over.

America just hoped that meant they could have some peace.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Decades before Christopher Nolan set his sights on a movie about J. Robert Oppenheimer, a science-obsessed BBC executive ventured to America in 1979 to make a $1.5 million TV show about the father of the atom bomb.

Peter Goodchild began his career at the BBC in radio drama, but eventually migrated to the storied “Horizon” science unit to put his chemistry degree to some use. The division began experimenting with factual dramas in the 1970s, and after delivering a hit series on French-Polish physicist Marie Curie, Goodchild set his sights on the New York-born Oppenheimer.

“I’d seen a play on J. Robert Oppenheimer at the Hampstead Theatre Club way back in 1966,” the 83-year-old tells Variety from his home in Exeter, southwest England, where his Zoom background reveals a room teeming with books on heaving shelves.

“It was an amazing story, and I’d always wanted to do it,” Goodchild continues. “Someone suddenly presented me with a book about Oppenheimer and his relationship with one of his other scientific colleagues, which was an excellent story. I said, ‘I’d love to take it further.’ And we did.”

Goodchild’s seven-part 1980 BBC series “Oppenheimer” — with the physicist played by 40-year-old Sam Waterston, just years away from his Oscar-nominated performance for “The Killing Fields” — received seven BAFTA nominations and took home three golden masks, including best drama series. The show, which was co-produced with WGBH Boston (which contributed just $100,000), also picked up a Golden Globe nod for Waterston along with two Primetime Emmy nominations.

Viewed through a contemporary lens, “Oppenheimer” is astonishing. A BBC-produced series telling an American story, featuring a predominantly American cast? It simply would never happen now. The broadcaster’s ongoing fight to justify its license fee-based funding model — in which every BBC-watching household in the U.K. pays £159 ($204) a year to fund its content — means that most original dramas on the Beeb have a distinctly British flavor.

But back then, “the sheer volume of drama that was happening was extraordinary,” explains Ruth Caleb, then a plucky line producer on “Oppenheimer.” “It went beyond the insular; it was much more outward-looking.” BBC drama still is, in some ways, she hastens to add. “But for different reasons that are often commercial reasons. Back then, they were creative reasons.”

“When Peter put up ‘Oppenheimer’ as an idea, it was clearly an important subject matter, because it’s not just about the country we live in, but about the world that we live in,” says Caleb, who is still producing films and scripted series under her own banner. “I think they trusted that Peter would come up with something pretty special.”

“Oppenheimer” introduces the nuclear physicist during his time with the University of Berkeley physics department — a halcyon period for the listless scientist, who surrounded himself with card-carrying Communists (though never fully subscribed himself) and carried on with the troubled Jean Tatlock while falling for Kitty Puening, a married woman.

The bulk of its seven hours focused on the formation of the Manhattan Project and the Los Alamos settlement in New Mexico, with special attention paid to Oppenheimer’s tumultuous relationship with General Leslie Groves and other scientists such as Edward Teller (played by “Poirot” star David Suchet). A masterful depiction of the Trinity test in Episode 5 used archival material to convey the actual blast, but also relied on a huge, arid Colorado Springs set. The final two episodes focused on Oppenheimer’s post-war troubles, and the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission hearing that stripped him of his security clearance, effectively severing his ties to U.S. government.

While much had been written by the late 1970s about Oppenheimer, who died of throat cancer in 1967, Goodchild and screenwriter Peter Prince spent a month in America researching the scientist. In addition to meeting a number of his academic peers — “They were happy to talk and talk!” says Goodchild — the duo also located Oppenheimer’s son Peter, his brother Frank and sister-in-law. (Kitty had died a few years prior, in 1972, while his daughter Toni died by suicide in 1977.)

“We got very, very strong images from his brother,” says Goodchild. “And then we went one Sunday morning to meet Peter. But when we arrived, he wasn’t there. Someone said he’s gone, but that he has these moods and may feel differently in an hour.”

So, Goodchild and Prince “hung out and wandered about” until he returned. “And he turned up,” the producer exclaims. “He wouldn’t let us in the house. He talked in a very—” Goodchild falters. “It was obvious life has not been straightforward for him.”

When the team began casting, they hired U.K.-based American actors, which helped to save money. A lead, however, proved elusive. All sorts of ideas were thrown at the wall — at one point, even “Psycho” star Anthony Perkins was in the mix — until Caleb suggested Waterston, who would need to be flown in from the U.S. where he’d been shooting a movie in Wisconsin.

“He was a dreamboat,” says Caleb. “Just the loveliest guy.”

Adds Goodchild: “I think we were paying him £1,200 a program. He liked the scripts, and said, ‘Yes, I’ll do it’ … We put him up in a house in Chelsea, which was around £1,200 a month, which seemed astronomical to us.” (Calculating for inflation, that’s roughly £6,500 per month.)

Waterston was worth the eye-watering Chelsea rent. His casting was considered to be a masterstroke due to his complex, unsentimental portrayal of Oppenheimer. One Manhattan Project scientist even remarked at the time that Waterston was “more Oppenheimer than Oppenheimer ever was.”

“My abiding memory of the production is how nice Sam Waterston was to work with,” screenwriter Peter Prince tells Variety over an email. “I re-watched a couple of episodes to refresh my memory and was reminded again how good Sam was as the actor: he was the complex Oppenheimer — charming, conflicted and driven.”

The show filmed between a studio in the U.K. for interior shots, and in Colorado Springs, where the Los Alamos project was constructed along with the vast tower that housed the atom bomb (pictured). “Everyone [tried] to be as authentic and near the actuality as possible,” says Caleb, who always had one eye on the $1.5 million budget — the equivalent of around $5.5 million today.

“When we were setting up Trinity, we hired this guy to make the bomb. And I knew that when we film, what you see in it is not the detail. But he did that bomb, which was hugely expensive, and every single detail of it was accurate — not that you ever saw it,” says Caleb. “I wasn’t pleased, yet he was so delighted that he managed to make this bomb exactly as it was. And all he got from me was a rather sour face saying ‘Yes, but you’ve gone over your budget!’”

Trinity was shot in three parts, with the American shoot completed over four weeks, followed by the studio work — which encompassed several control room scenes — and then other extraneous shots. Goodchild and Caleb detail a “pretty smooth” production that was primarily the work of the show’s gifted late director, Barry Davis, whom they describe as “fearsome” but someone who “knew what he wanted.” They also credit their editor Tariq Anwar, “who was brilliant,” adds Caleb.

Despite the show’s heavy subject matter, the team managed to eke out some fun on set. Toward the end of the shoot, when Suchet wrapped his final scenes as Teller and stepped out of the studio, “they delivered a cream pie into his face,” laughs Caleb. “I can’t remember whether it was Sam or someone else. But that demonstrates the good nature on the production. It was a happy production.”

Yet as one of Hollywood’s most visionary directors returns the A-bomb’s formidable creator to the cultural consciousness, the BBC’s “Oppenheimer” has become a largely forgotten production.

Goodchild — who used his research to write a book on Oppenheimer that published alongside the series in 1980 — had some interaction with Kai Bird, co-author of the 2005 Oppenheimer biography “American Prometheus” that Nolan’s film is based on. However, neither he nor Caleb were contacted by the “Tenet” director or Universal Studios as the new film came together. In fact, the pair are full of questions about how the movie turned out, and how it compares to the series. “I wonder what attracted [Nolan] to Oppenheimer,” Caleb says.

Goodchild, meanwhile, is shocked to hear the film will open on the same day as Greta Gerwig’s “Barbie.” “Wow,” he mutters. “I’m going to be very interested to see how well it goes down.”

Though there are 43 years between the TV show and the movie, the similarities in approach to scenes between Oppenheimer and the main players in his orbit are striking, particularly certain conversations between the scientist and Groves and Teller. The BBC series may be of its time — devoid of Ludwig Göransson’s feverish score, Nolan’s propulsive direction and a massive IMAX canvas — and made for around 5% of the movie’s budget in real terms, but in many ways, its narrative structure and use of sub-plots that delve deeper into Oppenheimer’s inner circle make it a more holistic portrait of an unpredictable character.

Caleb at one point asks whether the BBC will bring “Oppenheimer” out of the archives to air alongside the movie hitting cinemas. With an estimated opening of $50 million this weekend and clear public interest, it’s a good question.

But for all its critical success, “Oppenheimer” appears to have been all but lost in the annals of TV history. In the U.K., it’s not even on the BBC’s streaming service iPlayer; instead, it’s available for purchase on Prime Video for around £10. BBC Studios owns the rights to the series, but Variety understands a “complicated” rights situation means the show may not be rerun anytime soon.

Those who do uncover the series, of course, don’t tend to regret it. When Goodchild’s neighbors visited New Mexico several years back, he suggested they visit the National Museum of Nuclear Science and History.

“Not only did they do that, but they bought a DVD [of ‘Oppenheimer’] and took it home and watched it,” says Goodchild. “They came back and quite seriously said, ‘That was wonderful.’ After 42 years, it wasn’t something that got thrown at you very often.”'

#BBC#Oppenheimer#Peter Oppenheimer#Cillian Murphy#Kai Bird#Christopher Nolan#Peter Goodchild#Sam Waterston#Jean Tatlock#Kitty Puening#Edward Teller#David Suchet#Peter Prince#Barry Davis#Greta Gerwig#Barbie

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

My 2 Favorite Movies of Summer 2023

I watched a bunch of movies from June to July of this year, and I've come to the conclusion that my two favorite movies this summer are Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse and Oppenheimer.

While Mission: Impossible - Dead Reckoning Part One was enjoyable and Transformers: Rise of the Beasts was fun (especially as a Transformers fan), Across the Spider-Verse and Oppenheimer are two movies that have stuck with me since I've watched them.

So, this is not really a review per se but just an unfocused dumping of my thoughts about them.

SPIDER-MAN: ACROSS THE SPIDER-VERSE

I had been anticipating this movie since early this year, as did a lot of people. I was blown away by the animation and style that was shown by the trailers, so by the time it hit theaters I was hyped as hell. I initially wanted to see it with friends but their agendas didn't line up with when I wanted to so I ended up watching with my family much to my chagrin.

Anyway, I had such a blast watching the movie. I ended up watching it for a second time though I missed the intro sequence (embarrassing) but I still had a good time. Most of what I'm writing are much the same as other people so I'm going to be quick.

The animation was amazing (no pun intended), I love how the different universes are depicted in different art styles. I love the writing, how the characters and plot are written and the themes and it being kind of a commentary on your typical Spider-Man story. That ending sequence gave me chills, like, it was almost like the movie became a horror movie. It's clear that the movie was made with love, passion and care for art, animation and Spider-Man.

Overall, this movie was spectacular and it's likely that it'll be held as the new standard for animated movies in the future. That is until Beyond the Spider-Verse comes out and blows this movie out of the water like this movie did with Into.

It's such a shame this movie was produced under such abysmal conditions. Justice for the animation industry! It deserves so much better, man.

OPPENHEIMER

TW: Discussion of nuclear devastation

To be honest with you, I didn't much care about this movie before I watched it. I remember being ambivalent about it when the movie was first revealed. Later, out of the blue my dad suggested to my family that we go watch it and I joined mostly because I was like, "Eh, what the hell."

The movie was not what I expected.

For one thing, it didn't glorify the atomic bomb like I thought, even though it didn't show the devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the impact it had on the people of Japan. And, forgive me if I wrote out of turn, I don't think it needed to. For Oppenheimer (the character), the devastation was far away but just like during the Trinity nuclear test, he could still feel its effects even from far away.

Anyway, enough with the tangent. Let's talk about the actual goddamn movie.

It's definitely a Christopher Nolan movie featuring a non-linear story structure and epic and grand scope and presentation, with an extensive cast of actors, who I think did great with their portrayals. I could tell that every part of this movie was carefully crafted, everything from the casting, cinematography, production design, and special effects and visual effects, etc. are all executed with astonishing results. They recreated the Trinity bomb test with PRACTICAL EFFECTS I think that's fucking crazy.

This movie was so good, the ending, for the first time in a long time, left me with an actual fear of a nuclear holocaust, like, good g-d. If you want to talk about the politics of this movie, I'll tell you that it's clearly an anti-war film.

Unfortunately, I didn't get to see Barbie so I didn't participate in the Barbenheimer craze.

Overall, Oppenheimer is an excellent film. I don't think I have much more to write.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Thanks for indulging me during this trainwreck of a Tumblr post. I just wanted to talk about these two movies.

#across the spiderverse#spider man: across the spider verse#spider verse#oppenheimer#oppenheimer movie#review (kinda)#movies#film#please don't fight with me over the politics of oppenheimer#this post is kinda badly worded in places forgive me#thought dump

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wednesday, August 28, 2024

Fare Evasion Surges on N.Y.C. Buses, Where 48% of Riders Fail to Pay (NYT) Every weekday in New York City, close to one million bus riders—roughly one out of every two passengers—board without paying. The skipped fares are a crucial and growing loss of revenue for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, which is under severe financial pressure. New York’s long-running fare evasion problem, among the worst of any major city in the world, has intensified recently; before the pandemic, only about one in five bus riders skipped the fare. Yet public officials have done relatively little to collect the lost revenue from bus riders. Instead, they have focused almost exclusively on the subway system, where waves of police officers and private security guards have been deployed to enforce payment, even as fare evasion rates on trains are dwarfed by those on buses. Fare evasion has led to startling financial losses for the M.T.A., the state agency that runs the city transit system. In 2022, the authority lost $315 million because of bus fare evasion and $285 million as a result of subway fare beaters, according to a 2023 report commissioned by the M.T.A.

Downwinders from world’s 1st atomic test are on a mission to tell their story (AP) It was the summer of 1945 when the United States dropped atomic bombs on Japan, killing thousands of people as waves of destructive energy obliterated two cites. It was a decisive move that helped bring about the end of World War II, but survivors and the generations that followed were left to grapple with sickness from radiation exposure. At the time, U.S. President Harry Truman called it “the greatest scientific gamble in history,” saying the rain of ruin from the air would usher in a new concept of force and power. What he didn’t mention was that the federal government had already tested this new force on U.S. soil. Just weeks earlier in southern New Mexico, the early morning sky erupted with an incredible flash of light. Windows rattled hundreds of miles away and a trail of fallout stretched to the East Coast. Ash from the Trinity Test rained down for days. Children played in it, thinking it was snow. It covered fresh laundry that was hanging out to dry. It contaminated crops, singed livestock and found its way into cisterns used for drinking water. The story of New Mexico’s downwinders—the survivors of the world’s first atomic blast and those who helped mine the uranium needed for the nation’s arsenal—is little known. But that’s changing as the documentary “First We Bombed New Mexico” racks up awards from film festivals across the United States.