#Wieland Verlag

Text

Bernhard Winter

Die Stedinger Geschichtliche Darstellung

1984

Faksimile Verlag Wieland Soyka

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Collage Research - Hannah Höch

Personal Life -

Hannah Höch, (born November 1, 1889—died May 31, 1978), was a German artist, the only woman associated with the Berlin Dada group, known for her provocative collage that explores Weimar-era perceptions of gender and ethnic differences.

Höch began her training in 1912 at the School of Applied Arts in Berlin-Charlottenburg, where she studied glass design with Harold Bengen until her work was interrupted by World War I. She went back to Berlin in 1915 and re enrolled at the School of Applied Arts, where she studied painting and graphic design until 1920. In 1915 she met and became romantically involved with Austrian artist Raoul Hausmann, who in 1918 introduced her to the Berlin Dada circle, a group of artists that included George Grosz, Wieland Herzfelde, and Wieland’s older brother, John Heartfield. Höch began to experiment with nonobjective art through collage and photomontage consisting of fragments of imagery found in newspapers and magazines. From 1916 to 1926, to support herself and pay for her schooling, Höch worked part-time at Ullstein Verlag, a Berlin magazine-publishing house for which she wrote articles on and designed patterns for “women’s” handicrafts—mainly knitting, crocheting, and embroidery. That position gave her access to an abundant supply of images and text that she could use in her work.

In 1920 the group held the First International Dada Fair, Höch was allowed to participate only after Hausmann threatened to withdraw his own work from the exhibition if she was kept out. Höch’s large-scale photomontage Cut with the Kitchen Knife Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany (1919)—a forceful commentary, particularly on the gender issues erupting in postwar Weimar Germany—was one of the most prominently displayed and well-received works of the show. Despite her critical success, as the group’s only woman, Höch was typically patronized by and kept at the margins of the Berlin group. Consequently, she began to move away from Grosz and Heartfield and the others, including Hausmann, with whom she broke off her relationship in 1922. The Dada group dissolved in 1922, one of Höch’s final Dada works was My House-Sayings (1922).

It was Höch’s concern with and criticism of constructed gender roles that distinguished her work from that of her contemporaries in the Dada period. Höch had become interested in representing—and embodying—the “New Woman,” who wore her hair short, earned her own living, could make her own choices, and was generally ridding herself of the shackles of society’s traditional female roles.

From 1926 to 1929 Höch lived in The Hague with female Dutch author Til Brugman, who supported and encouraged her art. Their romantic relationship, scandalous for the time, compelled her further examination of traditional gender roles, cultural conventions, and the construction of identity.

After World War II, Höch worked hard to remain relevant and exhibit her work, coming out of hiding and participating in exhibitions already in 1945 and 1946. Until the end of her life, Höch worked with new modes of expression but regularly made reference to her past as well. She returned to influences and art-making practices from her early career, such as textile and pattern design, which she had learned with Orlik and from her job at Ullstein Verlag.

Over the water - 1943~1946

Practices -

Höch and the Dadaists were the first to embrace and develop the photograph as the dominant medium of the montage. Höch and Hausmann cut, overlapped photographic fragments in disorienting but meaningful ways to reflect the confusion and chaos of the postwar era. The Dadaists rejected the modern moral order, the violence of war, and the political constructs that had brought about the war. Their goal was to subvert all conventional modes of art making such as painting and sculpture. Their use of photomontage, which relied on mass-produced materials and required no academic art training, was a deliberate repudiation of the prevailing German Expressionist aesthetic and was intended as a type of anti-art. Ironically, the movement was quickly and enthusiastically absorbed into the art world and found appreciation among connoisseurs of fine art in the 1920s.

Between 1924 and 1930 she created From an Ethnographic Museum, a series of 18 to 20 composite figures that challenged both socially constructed gender roles and racial stereotypes. The provocative collages juxtapose representations of contemporary European women with “primitive” sculptures portrayed in a museum context. Höch was also particularly interested in the representation of women as dolls, mannequins, and puppets and as products for mass consumption. During her Dada period she had constructed and exhibited stuffed dolls that had exaggerated and abstract features but were clearly identifiable as female. In the late 1920s she used advertisement images of popular children’s dolls in several somewhat disturbing photomontages, including The Master (1925) and Love (c. 1926).

Her experience with textile design can be seen in Red Textile Page (1952; Rotes Textilblatt) and Around a Red Mouth (1967; Um einen roten Mund). Both of the aforementioned collages show Höch’s increasing use of colour images, which had become more readily available in print publications. In addition to exhibiting the wider use of colour, with the return of artistic freedom after the war, her work became more abstract, as in Poetry Around a Chimney (1956; Poesie um einen Schornstein).She achieved that abstraction by rotating or inverting her cut fragments so that they were readable no longer as images from the real world but instead as shapes and colour, open to many interpretations. In the 1960s she also reintroduced figural elements into her photomontages. In the colour assemblage Grotesque (1963), for example, two pairs of women’s legs are posed on a cobblestone street; one pair supports a woman’s fragmented facial features, the other a man’s bespectacled eyes and wrinkled forehead.

Why - Because Höch’s prolific career lasted six decades, her legacy can be attributed only partly to her participation in the short-lived Dada movement. Her desire to use art as a means to disrupt and unsettle the norms and categories of society remained a constant throughout. It is fitting that she used collage to construct a retrospective work: in Life Portrait (1972–73; Lebensbild), she assembled her own past, using photos of herself juxtaposed with images of past collages that she had cut from exhibition catalogues. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, her work began to receive renewed attention, thanks to a concerted effort by feminist scholars and artists to uncover, reevaluate, and reclaim the art created by Höch and other women during the early 20th century

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Old Vienna

Landstraße

Bürgertheater

Bürgertheater (3., Vordere Zollamtsstraße 13). Den eigentlichen Anstoß zur Gründung des Bürgertheaters gab der Schauspieler und Schriftsteller Oskar Fronz. Das Theater wurde nach Plänen von Franz Freiherr von Krauß und Josef Tölk erbaut und am 7. Dezember 1905 als Schauspielhaus eröffnet (Fassungsraum 1.134 Personen; Direktor Oskar Fronz).

SITZPLAN DES BÜRGERTHEATERS, 1905

Die innere Einteilung des Theaters entsprach etwa jener des Volkstheaters. Die dem Wienfluss zugewandte Hauptfassade war segmentförmig gekrümmt, der fünfachsige Mittelrisalit entsprach der Breite des Vestibüls. Die Fassade zeigte drei Reliefs von Elena Luksch-Makowsky (ausgeführt in glasiertem Steinzeug) sowie kolossale Eckfiguren von Georg Leisek.

Obwohl 1909 auch Alexander Girardi im Bürgertheater auftrat, kam es 1910 zu einer Krise, weil keine zugkräftigen Stücke aufgetrieben werden konnten. Deshalb erfolgte die Umwandlung in eine Operettenbühne (Erstaufführung der Operette "Der unsterbliche Lump" von Edmund Eysler am 14. Oktober 1910). Der große Erfolg führte dazu, dass Eysler zum "Hauskomponisten" des Bürgertheaters avancierte ("Der Frauenfresser", Erstaufführung 23. Dezember 1911; "Der lachende Ehemann", Erstaufführung 19. März 1913, bis 1921 1.793 Aufführungen; "Frühling am Rhein", Erstaufführung 10. Oktober 1914; "Die oder keine!", Erstaufführung 9. Oktober 1916; "Der dunkle Schatz", 14. November 1918).

Neben Werken von Eysler kamen auch solche von Oscar Straus ("Liebeszauber") und anderen zur Aufführung. Nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg wurde in der Spielzeit 1923/1924 "Mädi" von Robert Stolz aufgeführt. Am 24. Jänner 1925 dirigierte Pietro Mascagni die Aufführung seiner Operette "Ja".

Am 29. März 1925 starb Oskar Fronz, nachdem er das Bürgertheater fast zwei Jahrzehnte geleitet hatte. Es folgte ihm sein Sohn Oskar Fronz junior (anfangs gemeinsam mit Raoul Lischka), der bereits seit 1905 Sekretär und Direktor-Stellvertreter bei seinem Vater am Bürgertheater gewesen war.

1926 brach die Ära der Revue-Operette an ("Journal der Liebe" von Karl Farkas und Fritz Grünbaum mit Musik von Egon Neumann). Am 1. Oktober 1927 begann das Gastspiel der Marischka-Revue "Wien lacht wieder" (Musik Ralph Benatzky).

Während des Zweiten Weltkriegs war das Bürgertheater teilweise geschlossen, im April 1942 wurde es vorübergehend wiedereröffnet. Nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg wurde Franz Stoß Direktor (13. September 1945; Eröffnung mit "Im sechsten Stock" von Alfred Gehri). Unter ihm wurde das Bürgertheater zu einer volkstümlichen Zweigstelle des Theaters in der Josefstadt und unter den Schauspielern findet man Annie Rosar, Gusti Wolf und Guido Wieland.

Einen der letzten großen Erfolge verdankt das Bürgertheater der Marischka-Operette "Walzerkönigin" (Musik Ludwig Schmidseder). In "Hochzeitsnacht im Paradies" und "Feuerwerk" gab es so prominente Darsteller wie Maria Eis, Waltraut Haas, Heinz Conrads, Harry Fuß, Johannes Heesters und Fritz Imhoff.

1953 erfolgte der misslungene Versuch, dem Bürgertheater unter dem Namen "Broadwaybühne" eine neue Richtung zu weisen. In den 1950er Jahren diente das aufgelassene Theater dem Sender Rot-Weiß-Rot als Studiobühne, nahm aber auch die "Österreichische Spielwarenschau" auf und diente als "Haus der Jugend".

Als sich für das Bürgertheater keine Verwendung mehr fand, erwarb die Zentralsparkasse das Areal. Das Gebäude wurde ab 5. Jänner 1960 abgebrochen. An seiner Stelle entstand die neue Hauptanstalt der Zentralsparkasse der Gemeinde Wien (Eröffnung am 13. September 1965, Umbau [nach Brand] 1989-1992). Nach dem Auszug des Kreditinstituts, 2008, wurde das Gebäude (Adresse: 3., Vordere Zollamtsstraße 13) als Bürohaus adaptiert, in dem sich heute Redaktion und Verlag der Tageszeitung Der Standard und das Hauptbüro der Österreich Werbung, der offiziellen Marketingorganisation für den Tourismus nach Österreich, befinden.

0 notes

Text

Neuerscheinung in unserem Verlag "Buch und Note":

Ricarda Meinhold

Orgelpassacaglia

Das erste Werk der 2022 verstorbenen Komponistin in unserem Verlag. Vielen Dank an den Bruder der Komponistin (und Herausgeber) Wieland Meinhold für die erneute gute Zusammenarbeit.

Informationen auf unserer Verlags-Webseite:

https://www.musik-medienhaus.de/_bun/rubriken/orgel_solo.html#1022-03

Bestellen könnt Ihr das Werk in unserem Online-Shop unter https://dkunert.de/Meinhold-Ricarda-Orgelpassacaglia,

in unserem Notenkeller in Celle (http://www.notenkeller.de) oder bei jedem anderen gut sortierten Buch-/Musikalienhändler.

0 notes

Text

Collage Research

Here I will be documenting my research into the collage as a practice, as well as an artist I would like to draw inspiration from.

Why Collage? - I think collage would be a good process to try out, I can combine various media to replicate the various products hoarders can collect, as well as imply the feeling of being stuck in a crowded room, feeling suffocated by one’s own doing. I can also dive into how the hoarding mentality effects the victims relationships and environments, and probably more avenues since collage is relatively open. I have been collecting magazines and newspapers, as well as scrap paper, which I will combine into small collage pieces. I want to stick to mall collages, no bigger than A4, as I want it to be like a small zoom in on someone’s life. In an attempt to make a contrast against the reality where hoarding spreads and affects each and every part of the victims every life.

Collage History - Collage is considered an archetypal modern artistic technique, the word itself drives from the French verb coller meaning ‘to stick’. It was first used to describe the work of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, when they brought about theCubist movement when they stuck down newspaper cuttings and other materials to their canvas in 1912.

Research Links -

Artist Research - Hannah Höch

Life: Hannah Höch, (born November 1, 1889—died May 31, 1978), was a German artist, the only woman associated with the Berlin Dada group, known for her provocative collage that explores Weimar-era perceptions of gender and ethnic differences.

Höch began her training in 1912 at the School of Applied Arts in Berlin-Charlottenburg, where she studied glass design with Harold Bengen until her work was interrupted by World War I. She went back to Berlin in 1915 and re enrolled at the School of Applied Arts, where she studied painting and graphic design until 1920. In 1915 she met and became romantically involved with Austrian artist Raoul Hausmann, who in 1918 introduced her to the Berlin Dada circle, a group of artists that included George Grosz, Wieland Herzfelde, and Wieland’s older brother, John Heartfield. Höch began to experiment with nonobjective art through collage and photomontage consisting of fragments of imagery found in newspapers and magazines. From 1916 to 1926, to support herself and pay for her schooling, Höch worked part-time at Ullstein Verlag, a Berlin magazine-publishing house for which she wrote articles on and designed patterns for “women’s” handicrafts—mainly knitting, crocheting, and embroidery. That position gave her access to an abundant supply of images and text that she could use in her work.

In 1920 the group held the First International Dada Fair, Höch was allowed to participate only after Hausmann threatened to withdraw his own work from the exhibition if she was kept out. Höch’s large-scale photomontage Cut with the Kitchen Knife Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany (1919)—a forceful commentary, particularly on the gender issues erupting in postwar Weimar Germany—was one of the most prominently displayed and well-received works of the show. Despite her critical success, as the group’s only woman, Höch was typically patronized by and kept at the margins of the Berlin group. Consequently, she began to move away from Grosz and Heartfield and the others, including Hausmann, with whom she broke off her relationship in 1922. The Dada group dissolved in 1922, one of Höch’s final Dada works was My House-Sayings (1922).

It was Höch’s concern with and criticism of constructed gender roles that distinguished her work from that of her contemporaries in the Dada period. Höch had become interested in representing—and embodying—the “New Woman,” who wore her hair short, earned her own living, could make her own choices, and was generally ridding herself of the shackles of society’s traditional female roles.

From 1926 to 1929 Höch lived in The Hague with female Dutch author Til Brugman, who supported and encouraged her art. Their romantic relationship, scandalous for the time, compelled her further examination of traditional gender roles, cultural conventions, and the construction of identity.

After World War II, Höch worked hard to remain relevant and exhibit her work, coming out of hiding and participating in exhibitions already in 1945 and 1946. Until the end of her life, Höch worked with new modes of expression but regularly made reference to her past as well. She returned to influences and art-making practices from her early career, such as textile and pattern design, which she had learned with Orlik and from her job at Ullstein Verlag.

Art: Höch and the Dadaists were the first to embrace and develop the photograph as the dominant medium of the montage. Höch and Hausmann cut, overlapped photographic fragments in disorienting but meaningful ways to reflect the confusion and chaos of the postwar era. The Dadaists rejected the modern moral order, the violence of war, and the political constructs that had brought about the war. Their goal was to subvert all conventional modes of art making such as painting and sculpture. Their use of photomontage, which relied on mass-produced materials and required no academic art training, was a deliberate repudiation of the prevailing German Expressionist aesthetic and was intended as a type of anti-art. Ironically, the movement was quickly and enthusiastically absorbed into the art world and found appreciation among connoisseurs of fine art in the 1920s.

Between 1924 and 1930 she created From an Ethnographic Museum, a series of 18 to 20 composite figures that challenged both socially constructed gender roles and racial stereotypes. The provocative collages juxtapose representations of contemporary European women with “primitive” sculptures portrayed in a museum context. Höch was also particularly interested in the representation of women as dolls, mannequins, and puppets and as products for mass consumption. During her Dada period she had constructed and exhibited stuffed dolls that had exaggerated and abstract features but were clearly identifiable as female. In the late 1920s she used advertisement images of popular children’s dolls in several somewhat disturbing photomontages, including The Master (1925) and Love (c. 1926).

Her experience with textile design can be seen in Red Textile Page (1952; Rotes Textilblatt) and Around a Red Mouth (1967; Um einen roten Mund). Both of the aforementioned collages show Höch’s increasing use of colour images, which had become more readily available in print publications. In addition to exhibiting the wider use of colour, with the return of artistic freedom after the war, her work became more abstract, as in Poetry Around a Chimney (1956; Poesie um einen Schornstein).She achieved that abstraction by rotating or inverting her cut fragments so that they were readable no longer as images from the real world but instead as shapes and colour, open to many interpretations. In the 1960s she also reintroduced figural elements into her photomontages. In the colour assemblage Grotesque (1963), for example, two pairs of women’s legs are posed on a cobblestone street; one pair supports a woman’s fragmented facial features, the other a man’s bespectacled eyes and wrinkled forehead.

1 note

·

View note

Text

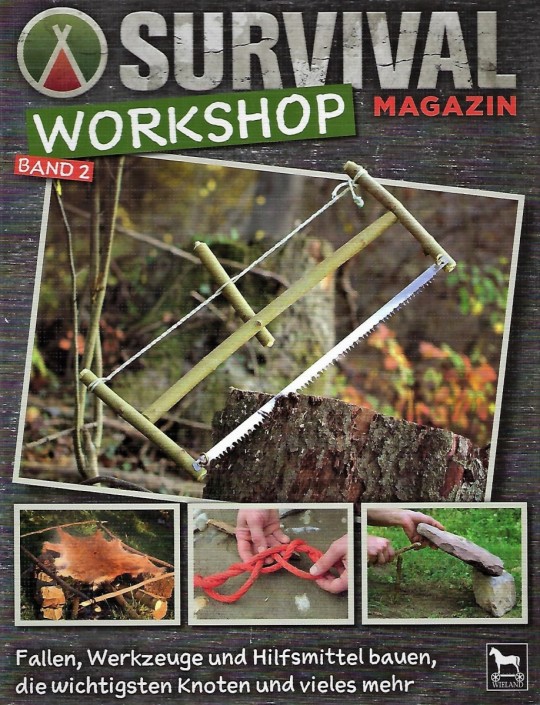

Survival Magazin Workshop Band 2: Fallen, Werkzeuge und Hilfsmittel bauen, die wichtigsten Knoten und vieles mehr

Survival Magazin Workshop Band 2: Fallen, Werkzeuge und Hilfsmittel bauen, die wichtigsten Knoten und vieles mehr

Buchvorstellung von Thomas Thelen

Das Buch Survival Magazin Workshop Band 2 dreht sich vorrangig ums Fallenbauen und -stellen, um draußen in der Natur im Notfall (!) hochwertige Nahrung erbeuten zu können. Wie in Band 1 (Schwerpunkt: Feuer machen und unterhalten) entfalten die drei erfahrenen und renommierten Outdoor-Experten Oliver Lang, Armin Tima und Joe Vogel in dem gut 140 Seiten…

View On WordPress

#Armin Tima#Buchvorstellung#Jagdblog#Joe Vogel#Kochen#Nahrung selber herstellen#Nahrung selber herstellen: Step-by-Step-Anleitungen für draußen#Oliver Lang#Rezension#Survival Magazin#Survival Magazin Workshop Band 2#Survival Magazin Workshop Band 2: Feuer#Thomas Thelen#Wieland Verlag

0 notes

Text

"Hier gilt's der Kunst". Wieland Wagner 1941-1945. Rezension

“Hier gilt’s der Kunst”. Wieland Wagner 1941-1945. Rezension

Schon das Cover des hier zu besprechenden Buches triggert die Leser. Jedenfalls so diese, welche halbwegs im Bilde sind über die berühmte Familie Wagner. Da war doch was! Ja, die engen Beziehungen der Familie zu Adolf Hitler. Daran ist kein Vorbeikommen. Auf dem Cover abgebildet ist Wieland Wagner, der sich bei Adolf Hitler eingehakt hat. Zu diesem Titelmotiv heißt es: Adolf Hitler mit den Enkeln…

View On WordPress

#Adolf Hitler#Anno Mungen#Bayreuth#Cosima Wagner#Komische Oper Berlin#Moshe Zuckermann#Peter Adam#Richard Wagner#Walter Felsenstein#Westend Verlag#Wieland Wagner#Wolfgang Wagner

0 notes

Photo

Die Leiche im Keller: Birgit Müller-Wielands „Flugschnee“ Sitzt da etwa ein Peter Weiss-Liebhaber in der diesjährigen Jury des Deutschen Buchpreises? Gleich zwei der Romane der Longlist weisen eklatante intertextuelle Bezüge zum epischen Jahrhundertwerk des deutsch-schwedischen Schriftstellers auf.

#dbp17#Berlin#Birgit Müller-Wieland#Deutscher Buchpreis#Die Ästhetik des Widerstands#Familiengeschichte#Familienroman#Flugschnee#Generationsroman#Hamburg#Longlist 2017#Otto Müller Verlag#Peter Weiss#Zweiter Weltkrieg

1 note

·

View note

Photo

1 note

·

View note

Text

Schubart-Denkmal in Aalen. Alle Bilder: Birgit Böllinger

„Gottes Schild flamm’ über dir! In dir werden Männer geboren stark und voll Kraft. Deutschheit, redlicher Sinn, schwäbische Herzlichkeit, redselige Laune, unschuldiger Scherz seyen immer, wie bisher, dein Eigenthum. Der Vorsicht Flügel schweb’ über eurer Kirche, eurem Rathhause, euren Hütten, und – eurem Gottesacker!“

Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart, Zitat aus „Simon von Aalen“, ca. 1775

Die Schwäbische Alb ist eine rauhe Landschaft. Geprägt vom Juragestein, ein Land, das den Menschen früherer Zeiten alles abverlangte. Der „Älbler“ er gilt gemeinhin als „eigen“. Und mitten hinein in diese herbe, karge Gegend wird 1739 ein wortstarker Freigeist und Luftikus geboren: Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart. Geboren im württembergischen Obersontheim wurde zur eigentlichen prägenden Stadt der Kindheit und Jugendjahre jedoch das nahegelegene Aalen: Hier wirkte der Vater Schubarts ab 1740 als Präzeptor und Musikdirektor.

In seinen Memoiren schrieb Schubart später:

“In dieser Stadt, die verkannt wie die redliche Einfalt, schon viele Jahre im Kochertale genügsame Bürger nährt – Bürger von altdeutscher Sitte, bieder geschäftig, wild und stark wie ihre Eichen, Verächter des Auslands, trotzige Verteidiger ihres Kittels, ihrer Misthaufen und ihrer donnernden Mundart, wurd ich erzogen… Was in Aalen gewöhnlicher Ton ist, scheint in anderen Städten trazischer Aufschrei und am Hofe Raserei zu sein. Von diesen ersten Grundzügen schreibt sich mein derber deutscher Ton…”

In Aalen lebte Schubart bis 1753, dann wurde er zur Vorbereitung auf die Universität auf das Gymnasium in dem etwa 40 Kilometer entfernten Nördlingen geschickt. Während des Theologiestudiums in Erlangen macht der Feuerkopf bereits das erste Mal Bekanntschaft mit dem Gefängnis – er, der zeitlebens Wein, Weib und Gesang zugetan war, landet dort wegen Schulden. Geknickt kehrt er 1760 nach Aalen zurück, wo er seinen Vater als Kantor und Prediger unterstützt. 1763 kommt er als Organist nach Geislingen, ebenfalls auf der Schwäbischen Alb gelegen, 1773 wird er jedoch als Stadtorganist wegen seines lockeren Lebenswandels und seiner frechen Zunge aus dem Dienst entlassen.

Sein weiterer Lebensweg führt ihn durch weite Teile Württembergs und Bayerns. 1774 ist ein bedeutsames Jahr: Schubart wendet sich dem Journalismus zu. In Augsburg gibt Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart erstmals ein Wochenblatt, das in der Regel zweimal wöchentlich erschien, unter dem Namen „Deutsche Chronik“ heraus. Bereits nach fünf Wochen verbietet der Augsburger Magistrat jedoch den Druck des Journals, dieser wird dann 1776 bis 1777 beim Verlag Wagner in Ulm fortgesetzt.

Heiner Jestrabek schreibt dazu in der Broschüre „Sturm und Drang auf der Ostalb“:

Die “Deutsche Chronik” war ein volkstümliches Blatt, das sich mit politischen Fragen befasste und literarische, pädagogische und poetische Beiträge brachte. Die Chronik war ausserordentlich erfolgreich und bald das wichtigste puplizistische Organ der bürgerlichen Opposition im ganzen Deutschen Reich. Schubart war jetzt 35 Jahre alt und hatte endlich einen Beruf, der Dauer und Einkommen versprach. 1775 wurden 1600 Exemplare verkauft. Da die Chronik viel herumgereicht wurde, hatte sie bis zu 20.000 Leser. Nach nur fünf Wochen wurde der Druck in Augsburg untersagt und musste nach Ulm verlegt werden. Die katholische Partei in Augsburg sah in Schubart ihren Hauptfeind. So wurde Schubarts Schlafzimmer mit einem Steinhagel bedacht, vor dem er nur unter seinem Bett Schutz fand. Besonders intensiv legte sich die Chronik mit dem Orden der Jesuiten an. Diese verbrannten sogar ein Spottgedicht des antiklerikalen Schubart öffentlich. Schubart schrieb in der Chronik: “den Geist dieses Ordens, der sich wie epidemischer Hauch im Finstern oder am hellen Mittage verderbend in einem Staat verbreitet”.

Schubart zieht 1775 nach Ulm, ist aber in der freien Reichsstadt gefangen. Nochmals Jestrabek:

„Auch mit seinen alten Widersachern, den Jesuiten gab’s Ärger. Ein Vorfall sollte die Brutalität und Gefährlichkeit dieser Klerikalen zeigen. Knapp ausserhalb der Ulmer Stadtmauern, in Wiblingen, wurde Josef Nickel, ein entlaufener Jesuitenschüler, der sich zu den Schriften Wielands, Lessings und Votaires bekannt hatte, gegen den Pater Gassner redete und offen für Schubart eintrat, unter dem Vorwurf der Ketzerei verhaftet, zum Tode verurteilt und “im Jahr des Heils 1776, am ersten Juni, Morgens 8 Uhr” geköpft. Schubart, der ihm einen Roman geliehen hatte, wurde beschuldigt, der Verursacher der “Religionsbeschimpfung und Gotteslästerei” Nickels gewesen zu sein. “Dieser Zufall kerkerte mich gleichsam in Ulm ein, weil mir ein gleiches Schicksal drohte”.

In diesen unruhigen Zeiten wird jedoch auch ein anderer Freiheitsdichter aus dem Württembergischen auf seinen Landsmann aufmerksam: 1775 veröffentlichte Schubart im „Schwäbischen Magazin“ seine Erzählung „Zur Geschichte des menschlichen Herzens“, Friedrich von Schiller liest diese später und verwendet sie in wesentlichen Teilen für sein Drama „Die Räuber“. Auch in der Erzählung, die Schubart mehrfach überarbeitete, zeigt sich seine spitze Zunge:

„Von uns armen Teutschen liest man nie ein Anekdötchen, und aus dem Stillschweigen unserer Schriftsteller müssen die Ausländer schließen, daß wir uns nur maschinenmäßig bewegen und daß Essen, Trinken, Dummarbeiten und Schlafen den ganzen Kreis eines Teutschen ausmache, in welchem er so lange unsinnig herumläuft, bis er schwindlige niederstürzt und stirbt. Allein, wann man die Charaktere von seiner Nation abziehen will, so wird ein wenig mehr Freiheit erfordert, als wir arme Teutsche haben, wo jeder treffende Zug, der der Feder eines offenen Kopfes entwischt, uns den Weg unter die Gesellschaft der Züchtlinge eröffnen kann.“

Als Schubart jedoch des württembergischen Herzogs Mätresse Franziska von Hohenheim in einem Schandgedicht als “Lichtputze, die glimmt und stinkt” verspottet, ist er in den Augen der Obrigkeit fällig: Durch eine Intrige wird er 1777 nach Blaubeuren gelockt, von da aus geht es in den Kerker in Hohenasperg. Ohne Anklage oder gar Verurteilung wird Schubart in der Festung Asperg für zehn Jahre eingesperrt und damit der berühmteste politische Gefangene seiner Zeit. Er darf keine Besucher empfangen und wird in den Anfangsjahren mit Schreib- und Leseverbot belegt. Erst die politische Intervention Preußens führte zu seiner Freilassung 1787. Zwar setzt er seine angriffslustige Polemik auch dann wieder fort, unter anderem in der Vaterländischen Chronik. 1791 stirbt er jedoch, physisch wie psychisch gebrochen.

Zu seinem 275. Geburtstag würdigte ihn Frank Suppanz in einer Veröffentlichung des Reclam Verlages:

„Es wäre zu einseitig, in Schubart nur den literarischen Polemiker zu sehen. Er war ein hochbegabter Klavierspieler und Organist (…) Die Musik schien differenziertere Seiten in Schubarts Charakter zum Vorschein zu bringen. In seinen „Ideen zur Ästhetik der Tonkunst“ argumentiert ein Vollblutmusiker mit klassizistischen Normen – für Angemessenheit als Maßstab des musikalischen Ausdrucks und für feine Nuancierung als Voraussetzung eines schönen Vortrags.“

Gedenktafel am Wohnhaus in Aalen.

Das ehemalige Wohnhaus der Familie Schubart in Aalen, ein Bürgerhaus aus dem 17. Jahrhundert.

Zu seinem 280. Geburtstag erinnert die Stadt, der er zeitlebens innerlich verbunden blieb, mit zahlreichen Aktivitäten an den freiheitsliebenden Dichter und Musiker: So findet in Aalen am kommenden Wochenende (22. und 23. Februar 2019) eine Tagung zu „Schubart und die französische Revolution“ statt, der renommierte Schubart-Preis wird an Daniel Kehlmann vergeben und in der Veranstaltungsreihe „wortgewaltig“ wird der Bogen von Schubart zur zeitgenössischen Kultur geschlagen.

Ein Besuch der oberschwäbischen Stadt lohnt sich auch unabhängig von den Schubart-Aktivitäten wegen seiner Limes-Thermen und seines mit den Römern verbundenen Status als Stätte des Weltkulturerbes: Hier befand sich das größte römische Reiterkastell nördlich der Alpen. Das Limesmuseum, die größte Einrichtung Süddeutschlands am UNESCO-Welterbe Limes, ist allemal einen Besuch wert, war allerdings in den vergangenen drei Jahren wegen grundlegenden Umbaus geschlossen. Ab Ende Mai können die Spuren der Römer auf der Alb wieder besichtigt werden.

Texte von Schubart:

Gedichte und Texte in der Bibliotheca Augustana

„Zur Geschichte des menschlichen Herzens“ im Projekt Gutenberg

Stoffgeschichte zu „Die Räuber“

Biographisches:

„Das Leben des Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart“ von Heiner Jestrabek

Schubart in der „Deutsche Biographie“

Orte:

Schubartjahr 2019 in Aalen

Schubart-Sammlung in Aalen

Schubart-Stube Blaubeuren

Der Blautopf und die Literatur

LITERARISCHE ORTE: Der Revoluzzer von der Alb „Gottes Schild flamm' über dir! In dir werden Männer geboren stark und voll Kraft. Deutschheit, redlicher Sinn, schwäbische Herzlichkeit, redselige Laune, unschuldiger Scherz seyen immer, wie bisher, dein Eigenthum.

#Aalen#Augsburg#Baden-Württemberg#Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart#Daniel Kehlmann#Deutsche Chronik#Friedrich Schiller#Hohenasperg#Literatur#Schwäbische Alb#Ulm

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kopf und Körper

Über seine Klasse kann keiner hinaus – ein Versuch über die Unterwürfigkeit der Vernunft von einem ihrer Anhänger

"Sie (Ideologie) ist impermeabel auch von außen. Wohlmeinende Belehrungen werden einfach nicht verstanden, oder, wenn sie verstanden werden, durch allzu viele deutliche Fälle aus dem vertrautesten Gesichtskreis widerlegt. Dort, wo einer sich auskennt, wird seine Meinung bestätigt, denn da hat er sie her. Die Ideologie kann, um mit Wieland³ zu reden, »kühnlich allen Bildnern, Schnitzlern, Anstreichern, Verzierern, Lackierern, Vergoldern, Frisierern und Parfumierern der Menschheit, kurz, allen Philosophen der ganzen Welt, Trotz bieten«. Daher die erste Regel der Sozialpraxis: Wer Menschen ändern will, muss nicht die Gemüter, sondern die Umstände ändern."

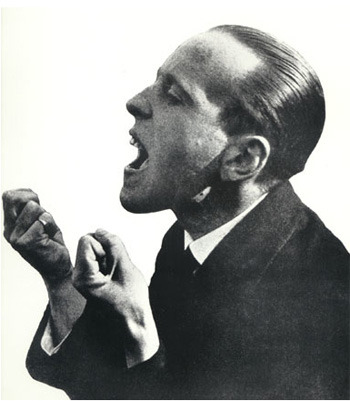

»Wer Menschen ändern will, muss nicht die Gemüter, sondern die Umstände ändern.« – der junge Peter Hacks bei einem Auftritt mit satirischen Gedichten in der »Schwabinger Laterne« (vermutlich 1949)

Foto: Eulenspiegel Verlag

https://www.jungewelt.de/artikel/345446.marxismus-kopf-und-körper.html

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Haye W. Hansen

Steinkammer von Stöckheim, Altmark

Holzschnitt, wahrscheinlich aus den 1930er Jahren

https://www.feuerstahl.org/h%C3%BCnengrab/

Dr. Haye W. Hansen. Künstler und Wissenschaftler 1903 - 1988

Ein Nachruf E. Heinsius

Faksimile-Verlag Wieland Soyka, 1988. Bremen

http://galleria.thule-italia.com/haye-walter-hansen/

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sonntags Lektüre: "Legende Laguiole" von Christian Lemasson, erschienen im Wieland Verlag. Glücklicherweise von Wolfgang Lantelme übersetzt. Schönen Sonntag euch allen! #legendelaguiole #laguiole #messer #fachbuch #couteaux #livredecouteaux #christianlemasson #wolfganglantelme #wielandverlag (hier: Laguiole, France) https://www.instagram.com/p/Cd2eWw6Mx6f/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#legendelaguiole#laguiole#messer#fachbuch#couteaux#livredecouteaux#christianlemasson#wolfganglantelme#wielandverlag

1 note

·

View note

Text

schwarz auf weiß

roman von andreas lehmann

erschienen 2021

im karl rauch verlag

isbn: 978-3-7920-0270-4

(von tobias bruns)

martin oppenländer macht sich zur unzeit selbstständig und versucht mit seiner geschäftsidee des gesundheitsmanagements kunden zu gewinnen. nicht leicht in zeiten eines lockdowns und damit zusammenhängender isolation... wie soll man kunden gewinnen, wenn man die ganze zeit zuhause ist? doch plötzlich klingelt sein festnetztelefon und hoffnung kommt auf. doch am telefon ist kein neuer auftraggeber, sondern rebekka wieland. wer aber ist rebekka wieland? martin kann sich beim besten willen nicht an eine frau mit diesem namen erinnern. so sehr er auch versucht in seinen erinnerungen zu graben, so sehr frau wiegand, wie er sie anfangs nennt auch versucht ihm auf die sprünge zu helfen - die dame scheint ein phantom zu sein. er erinnert sich an den ort des kennenlernens, das event des kennenlernens, die bar, in der die beiden sich wohl ewig unterhielten, aber die frau, die dazugehörte... fehlanzeige. doch was war da zwischen den beiden vorgefallen, dass sich frau wiegand wohl große hoffnungen auf eine gemeinsame zukunft gemacht hatte? die anrufe werden zu einem mit sehnsucht erwartetem event in der ganzen monotonie, die herrscht und martin versucht durch die gespräche auch sich selbst zu finden oder besser sich selbst zu ergründen. er durchforstet seine vergangenheit, seine chancen, sein gewissen, seine umgebung, sein notizbuch, dass ihn immer begleitet, damit er seine gedanken, ideen oder anderes schnell aufschreiben kann, bevor er sie vergisst, damit er sie “schwarz auf weiß” vor sich hat und kommt auf in normalen zeiten unerhörte ideen...

langsam scheint es zu beginnen, die immernoch laufende pandemie auch literarisch zu verarbeiten. andreas lehmann legt hier einen guten grundstein, der die reale absurdität der situation, in der sich die gesellschaft weltweit seit märz letzten jahres (2020) befindet hervorragend einfängt. dadurch dass man hier von einem er-erzähler durch den roman geleitet wird, fühlt man sich durchgängig als beobachter, der dem protagonisten überall auf schritt und tritt über die schulter schaut und dennoch - durch die vielen telefonate - bekommt der leser spielend einen blick ins innere des martin oppenländer. doch auch der er-erzähler verschweigt nicht, was in martin vorgeht: “sogar bei selbstgesprächen hat er das gefühl, dass er nicht mitreden kann.” es sind solche sätze, an denen diese geschichte nicht spart, die dem leser spaß machen, aber auch den gemütszustand des protagonisten offenbaren, der wie jeder andere auch mit den kontaktbeschränkungen zurecht kommen muss und dabei manchmal einfach zuviel zeit hat sich gedanken zu machen - über alles... (wieviele menschen haben in dieser zeit wohl tatsächlich begonnen selbstgespräche zu führen, vor allem wenn sie alleinstehend sind?) eine große rolle spielt im roman martins notizbuch, das buch in diesem buch, dass nicht nur ihn selbst widerspiegelt, sondern die gesamte gesellschaft - vor und in der pandemie und dazu die frage, wie es danach wohl weitergehen wird. ein roman, wie er gerade gebraucht wird!

#schwarz auf weiß#andreas lehmann#karl rauch#verlag karl rauch#literatur#roman#rezension#philosophenstreik#tobias bruns#literaturkritik#isolation

0 notes

Photo

De Chirico, Giorgio. Wir Metaphysiker. Propyläen Verlag, Berlin. 1973. 4°. OLn. mit OU 236(1) S., Gesammelte Schriften. Hrsg. von Wieland Schmied #dechirico #giorgiodechirico #metaphysics #kunstkiosk #kunstkioskimhelmhaus https://bit.ly/3lfrkZO (hier: Zürich, Switzerland) https://www.instagram.com/p/CERwj6pFVWv/?igshid=pe0srck90bfr

0 notes

Text

Fourcorners Gallery till Feb 8th https://www.fourcornersfilm.co.uk/another-eye

https://www.fourcornersfilm.co.uk/another-eye

Biography from https://www.johnheartfield.com/John-Heartfield-Exhibition/helmut-herzfeld-john-heartfield-life/artist-john-heartfield-biography

Bertolt Brecht: “John Heartfield is one of the most important European artists.”

John Heartfield is known:

As the founder of modern photomontage (photo montage), a form of collage. Living in Berlin, he risked his life to used his art “as a weapon” to combat fascist propaganda, Adolf Hitler, and The Third Reich.

As the inventor of 3-D book dust jackets, book covers that told a “story” from the front cover of the book to the back.

For his groundbreaking use of typography as a graphic design

For his innovative theater collaborations with Bertolt Brecht. Work that lead the world-famous playright and composer to develop a new form of theater.

German artist John Heartfield is a clear example of artistic genius combined with a heroism going far beyond the required courage of any great artist.

John Heartfield Biography

John Heartfield’s Art Saved Lives

Heartfield’s anti-fascist anti-Nazi art became famous on both sides of the Atlantic before and during WW2. Heartfield used fascists’ own words and images against them. His message was clear: “You must oppose this madness, escape, or do both.”

John Heartfield Biography

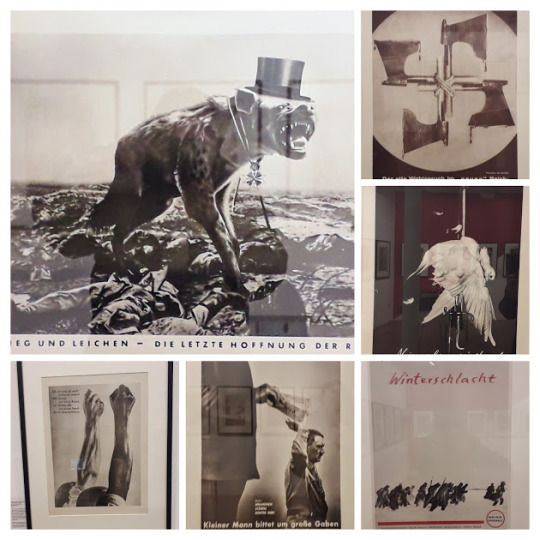

The Photomontages Of The Nazi Period

A John Heartfield biography must begin by highlighting the years when Heartfield’s genius reached its zenith. His famous political art, which he labeled “photomontages” expressed his hatred of fascists, especially Adolf Hitler and The Third Reich. From 1930 to 1938, Heartfield designed 240 pieces of anti-Nazi art for the AIZ [Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung], a magazine published by the New German Press, which was run by the political activist Willi Münzenberg. The AIZ had a significant readership in Weimar-era Germany. It may easily have had the second highest circulation in Germany in the early nineteen thirties. After the National Socialists took control, the AIZ was published for German readers in Czechoslovakia, Austria, Switzerland, and Eastern France.

To fully understand a John Heartfield biography, it’s vital to remember his artistic courage was equal to his physical courage. Heartfield was a resident of Berlin until 1933. His vehemently anti-fascist collages appeared on the covers of the AIZ on newsstands throughout the city. This is a vital point. From 1930-1933, Heartfield’s scathing anti-Nazi montages were clearly visible on Berlin Streets. Supporters also pasted posters of his montages on walls and surfaces for any passersby to see.

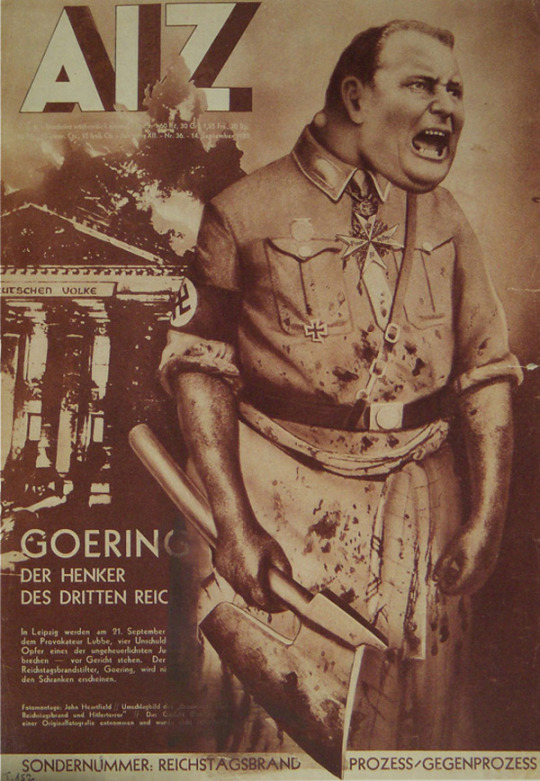

Although he shined in several other mediums, such as stage sets and book covers, there’s no doubt that Heartfield is best known for the satiric political montages he created during the 1930s to expose the insanity of Adolf Hitler, Herman Göring, and the entire Nazi philosophy. To battle the Third Reich with art, Heartfield created some of his most famous montages.

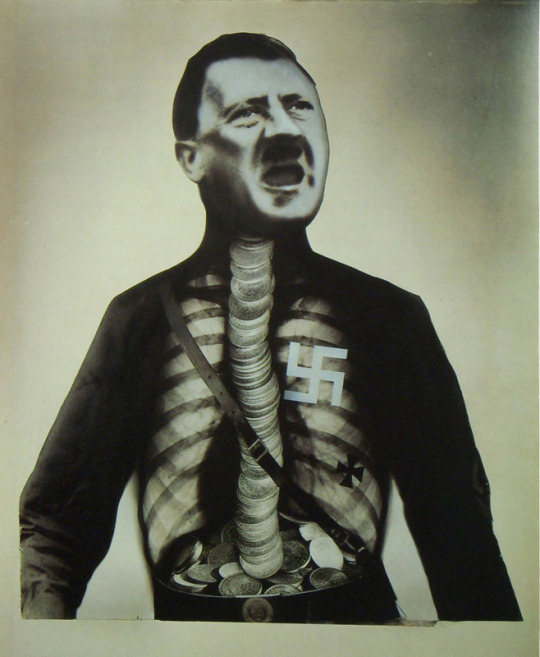

Adolf der Übermensch and Goering: der Henker are two examples of photo montages Heartfield produced and had widely distributed while he remained under constant threat of assassination by Hitler’s Third Reich.

This 1932 John Heartfield portrait of Adolf Hitler In Adolf The Superman: Swallows Gold and spouts Junk appeared all over Berlin corners placed in newsstands in 1932 on the cover of the popular AIZ magazine. Heartfield used an X-ray to show gold coins in the Führer’s throat leading to a pile in his stomach. Hitler changes his supporter’s gold to lies.

Adolf Der Übermensch: Schluckt Gold und redet Blech

(Adolf The Superman: Swallows Gold and spouts Junk)

The famous political artist who created famous WW II anti-Nazi art against Adolf Hitler

In the photomontage Göring: The Executioner of the Third Reich, Hitler’s designated successor is depicted as a bloody butcher. In 1934, Heartfield created this famous AIZ cover that exposed Hermann Goering as The Third Reich’s executioner. Goering had blamed the Reichstag fire that helped Hitler seize power as the work of Jews and communists.

Göring: Der Henker des Dritten Reichs

(Goering: The Executioner of the Third Reich)

AIZ Magazine Cover, Prague, Czechoslovakia, 1933

The artist who created famous WW II anti-Nazi art

From 1930-1938, he created an astounding 240 photomontages for covers of the AIZ magazine (circulation around 300,000 to 500,000 at its height). These 240 brilliant works of art were a complete description of the rise of fascism in the 20th century.

Heartfield’s AIZ covers appeared on street corners all over Adolf Hitler’s Berlin. His “Photomontages of the Nazi Period” are a feat of political art that has never been duplicated.

Heartfield lived in Berlin until Easter Sunday, April 1933, when he narrowly escaped assassination by the SS. He fled across the Sudeten Mountains to Czechoslovakia where he rose to number-five on the Gestapo’s most wanted list.

Below is an excerpt From David King’s book, John Heartfield, The Devastating Power Of Laughter. It describes the 1933 Easter Sunday Evening when Hitler’s jackboots came for John Heartfield.

“Berlin, April 14, 1933: They came for him in the night. The paramilitary SS burst into the apartment block and headed straight for the raised ground floor studio where John Heartfield was in the middle of packing up his artwork, knowing that his only chance left of survival was a life in exile; he was on their most wanted list. Hearing them dislocating his heavy wooden door, he dived through his french windows and leapt over the balcony into the darkness. He landed badly and sprained his ankle.

The Nazis made a flashlight sweep search of the darkened courtyard below yet failed to focus on an old metal bin in the far corner on which were displayed some enamel signs, the sort that advertise motor oil, or soap, or an aperitif. Under its battered lid, one of Hitler’s greatest enemies, far from having vanished into the ether, crouched in torment, squashed in a box full of the local residents’ garbage. For the next seven hours he hid there, toughing it out as he heard the nightmare sounds of the barbarians ransacking his studio and destroying his work.

When the raid was over, Heartfield quietly and unobtrusively opened the lid, climbed out of the bin, exited the courtyard and began his nerve-racking flight to Prague. Germany was now enemy territory, there was a high price on his head and he had nothing.”

After his narrow escape from the SS, Heartfield walked around the Sudeten Mountains to Czechoslovakia.

[Below: John Heartfield In Mountain Gear. Credit: John J Heartfield Collection.]

The artist persecuted by The Nazis

Heartfield had been beaten by Hitler’s supporter’s and thrown from a streetcar in Berlin. The artist who openly attacked Adolf Hitler and The Nazi Party while living in Berlin was five-foot-two inches tall, with red hair and blue eyes. His “weapon” was his imagination, scissors, glue pots, dabs of paint, and stacks of photographs and magazine articles. He insisted his montages contained both literal and ethical truth.

From his early work as fledging painter to his embrace of Dada to the anti-fascist montages that made him a Nazi target, Heartfield’s life and work was a profile in courage.

Forced to flee Nazi Germany a step ahead of the SS, Heartfield attacked the Nazi Party from Prague.

You can find more of Heartfield’s collages in ART AS A WEAPON has more of John Heartfield’s anti-fascist collages with historical perspective.

John Heartfield Biography

The Frail Artist Who Stood Up To Hitler

Heartfield was born into poverty June 19, 1891 in Berlin-Schmargendorf. He was named “Helmut Franz Josef Herzfeld.” The photo above of a young Helmut Herzfeld with a moustache was taken in 1912. Under the photo at the top of this page is a scan of what Herzfeld wrote on its back [Credit: John J Heartfield Collection].

When he was eight, Heartfield’s parents abandoned him, his younger brother, Wieland, and their two even younger sisters, Charlotte and Hertha, in a cabin in the woods. The children were separated and raised in a series of foster homes. Throughout his life, Heartfield maintained a close relationship with his brother, Wieland. In 1913, Wieland Herzfeld also changed his name, less dramatically to “Wieland Herzfelde.”

It was in 1916, while he was living in Berlin, that Herzfeld became disgusted with the shouts of “God Punish England!” that were so common in the streets of the city. As a protest against the anti-British fervor sweeping Germany, he informally changed his name from Helmut Herzfeld to John Heartfield to become, as David King later described him, “the greatest political artist and graphic designer of the twentieth century.”

It was not until August 27, 1964, that his name was legally changed to John Heartfield.

In 1912, after studying arts and crafts in Munich and Berlin, he found work as a commercial artist. From the beginning, Heartfield was infused with a passionate belief that the purpose of art was not to glorify the artist, but to serve the common good.

In 1916, Heartfield met the eccentric genius, George Grosz. Shortly afterwards, Heartfield destroyed all his paintings [mainly landscapes] except one entitled, The Cottage In The Woods.

Grosz had opened his eyes. Heartfield saw his oil paintings did not reflect his passion for honesty and change. He joined Berlin Club Dada in 1917 and became a central figure in the German Dada art movement. Dada has had a profound effect upon culture, advertising, politics, and society. Early one morning in 1916, Heartfield and George Grosz experimented with pasting pictures together. From this exercise grew Heartfield’s lifetime obsession with “photomontage.”

In 1917, John Heartfield founded the Malik-Verlag publishing house in Berlin. At that time, his beloved brother, Wieland, was serving near the front. The brothers were soon to become partners in Malik-Verlag, with John being responsible for the majority of the graphics.

Heartfield invented the concept of three-dimensional wrap-around book dust jackets. The book dust jackets told a story from the front cover to the back. There’s speculation that Malik-Verlag sold more publications because of Heartfield’s covers than the actual content of the books.

In 1920, Heartfield helped organize the Erste Internationale Dada-Messe [First International Dada Fair] in Berlin. Dadaists were the young lions of the German art scene, rebels who often disrupted public art gatherings and made fun of the participants. They labeled traditional art trivial and bourgeois. Heartfield was a vital member of a circle of German titans that included Hannah Höch, George Grosz, Kurt Schwitters, Richard Huelsenbeck, Raoul Hausmann, and others.

During the 1920s, Heartfield had produced a great number of photo montages for Malik-Verlag Publishing. He created groundbreaking dust jackets for books by Upton Sinclair, Kurt Tucholsky, and many other progressive writers.

In January of 1918, Heartfield joined the newly founded German Communist Party (KPD). The KPD, eventually blamed by the Nazis for the burning of the Reichstag, was the only serious political threat to the rise of Adolf Hitler and The Third Reich. From many of his montages, it is clear that Heartfield blamed the greed of capitalists, especially those that manufactured steel and munitions, for the horrors he had witnessed firsthand during World War I.

It is essential to note that the vast majority of his work demonstrates that Heartfield was a devoted pacifist. CURATOR’S NOTE: My own conversations with my grandfather made it clear to me that he never supported violence in any form. He had faith in people and the truth. He was certain if he brought the two together the result would be a better life for all.

John Heartfield Biography

Artistic Genius In The Weimar Republic

The work of Weimar Republic artists, writers, composers, and playwrights had a profound effect upon Heartfield. He, in turn, deeply influenced their work. His theater sets were vital elements in the early works of Bertolt Brecht and Erwin Piscator.

The Alienation Effect [Verfremdungs-effekt]

Heartfield played a major role in helping Brecht to realize the concept of the “Alienation Effect” [Verfremdungs-effekt]. The playwright used Heartfield’s simple props and stark stage set. Heartfield’s streetcar broke down one night on the way to the theater. He had to carry his screens for the Brecht’s play through the streets. He arrived after the play had begun. Brecht stopped the play and asked the audience to vote on whether Heartfield should be allowed to put up his sets.

Brecht developed this technique to remind spectators that they were experiencing an enactment of reality and not reality itself. Brecht interrupted his plays at key junctures to let the audience to be part of the action and not lose themselves in it. It’s a form of theatre that continued through decades in shows such as those by The Living Theater and Joe Papp’s Shakespeare productions.

The “Engineer” Heartfield

Heartfield preferred reality to artistic pretension. While he referred to himself as a “monteur,” he preferred the title “engineer.” A George Grosz painting The Engineer Heartfield hangs in MOMA, The Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Although he did not wish to be labeled an artist, Heartfield had a full measure of an artist’s passion. His Dada contemporaries tied him to a chair and enraged him just to experience the unbridled intensity of his emotions.

John Heartfield Biography. Club Dada Founder

John Heartfield Biography

A Fighter For World Peace

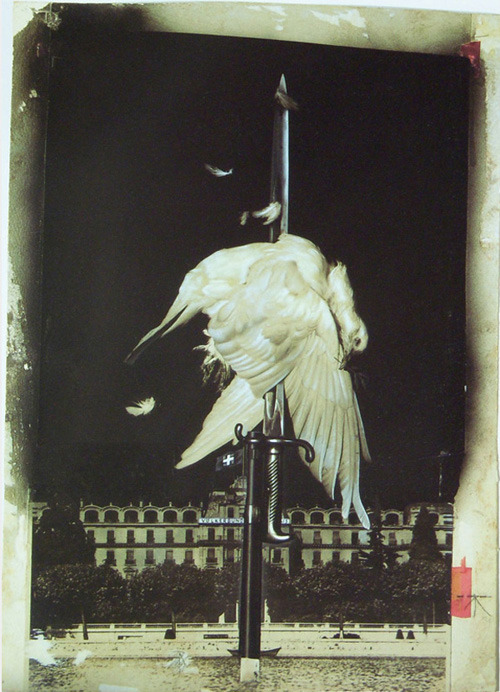

One of Heartfield’s most famous montages, The Meaning of Geneva, Where Capital Lives, There Can Be No Peace!, shows a dove of peace impaled on a blood-soaked bayonet in front of the League of Nations, where the cross of the Swiss flag has morphed into a swastika. John Heartfield’s love of all animals and nature is well documented. This image can be considered an especially deep emotional expression.

Der Sinn von Genf The Meaning of Geneva AIZ Cover, Berlin, Germany, 1932

John Heartfield Biography. Most famous political art Never Again! dove on bayonet

You can learn more about this montage and many others, along with historical perspective, in the ART AS A WEAPON section of the exhibition.

Heartfield’s artistic output was enormous and widely display. It was through rotogravure—an engraving process whereby pictures, designs, and words are engraved into the printing plate or printing cylinder—that he was able to reach this audience he coveted.

CURATOR’S NOTE: I’m certain my grandfather would be pleased and fascinated to see his work reproduced throughout the Internet and on this Digital Exhibition.

Forced to flee from Berlin, he continued to use the National Socialists’ own words to expose the truth behind their twisted dreams. In 1934, he montaged four bloody axes tied together to form a swastika to mock The Old Slogan in the “New” Reich: Blood and Iron (AIZ, Prague, March 8, 1934).

In 1938, he had to again run for his life before the imminent Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia. There were over 600 people on the Gestapo’s Most Wanted List. John Heartfield was number five. He settled in England. He was interned several times in England as an enemy alien. He was released as his health began to deteriorate. His brother, Wieland, was refused an English residency permit in 1939 and, with his family, left for the United States. John wished to accompany his brother, but was refused entry.

John Heartfield Biography

East German (GDR) Persecution

In 1941, Heartfield made it clear that he wished to remain in England and did not wish to return to East Germany [see John Heartfield Letter, 1941]. He and his third wife, Gertrud, found themselves with limited options.

Humboldt University in East Berlin offered Heartfield the position of “Professorship of Satirical Graphics” in 1947.

His response was, “Do I have to be a professor?”

Eventually, his brother Wieland convinced Heartfield to join him in East Berlin. He wanted his brother to take the apartment next to him. Wieland convinced Heartfield that he’d been well treated because Wieland had a comfortable position at a university.

In 1950, John Heartfield joined his brother in East Berlin. The artist who had held such strong beliefs in communist philosophy in his youth was greeted with nothing but suspicion because of the length of his stay in England. He was interrogated by the Stasi and nearly tried for treason against the state. For six years, Heartfield was denied admission to the East German Akademie der Künste. He was unable to work as an artist and denied health benefits.

After six years of official neglect by the East German Akademie der Künste [Academy of Arts], Bertolt Brecht and Stefan Heym intervened on Heartfield’s behalf. He was admitted to the GDR AdK in 1956. However, his health never improved. The later years of life were devoted to designing brilliant costumes, stage sets, and stage projection for the East German Theatre.

John Heartfield died on April 26, 1968 in East Berlin, German Democratic Republic.

Almost all of John Heartfield’s surviving original art is held within the Heartfield Archiv, Akademie der Künste, Berlin, Germany. The David King Collection is stored in the Tate Modern London. Hopefully, there will be free public exhibitions soon.

1 note

·

View note