#Zeb-un-Nissa

Text

“That Mughal women wrote quite extensively is remarkable and their works, wherever available, are extraordinary. Other Mughal women apart from Gulbadan left writings. Jahanara wrote two Sufi treatises as well as poetry. She corresponded extensively, not only with kings wanting her patronage but also with her brothers, Aurangzeb and Dara Shikoh, and she became the vortex of the succession struggle between the two princes, both brothers seeking her support. Many of the women, including Aurangzeb’s daughter Zeb-un-Nisa, wrote poetry. The women wrote farmans, or orders, and had seals in their names, which can be as eloquent as an entire biography. Noor Jahan’s seal reads ‘By the light of the sun of the emperor Jahangir, the bezel of the seal of Noor Jahan, the Empress of the age has become resplendent like the moon’—this is surely as powerful a testimony to her own ambition and glory than any biographer’s praise.”

- Ira Mukhoty, “Daughters of the Sun: Empresses, Queens and Begums of the Mughal Empire”

#history#historicwomendaily#indian history#mughal empire#mughal era#Jahanara Begum#Gulbadan Begum#Noor Jahan#Zeb-un-Nissa#mine#queue

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh cruel Love, when on the Day of Judgment,

your tyranny the Almighty will be repaying…

and all that blameless blood that you've shed

shall on your haughty head revenge be taking.

1 note

·

View note

Text

A nightingale came to the flower garden

because she was my pupil.

I am an expert in things of love.

even the moth is my disciple.

Princess Zeb-un-Nissa

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

—Makhfi (Princess Zeb-un-Nissa), translated by Dick Davis

Image I.D. — “I flee from knowing others so much that / Even before a mirror my eyes stay shut.” — End I.D.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

ZEB-UN-NISSA // PRINCESS OF THE MUGHAL EMPIRE

“She was a Mughal princess and poet with pen name ‘Makhfi’ (Hidden one in Persian). As a child, she was a favourite of her father, Emperor Aurangzeb, and received a wide education. She wrote many books of poetry but something went wrong because her beloved father imprisoned her for the last twenty years of her life at Salimgarh Fort in Delhi.”

0 notes

Text

Interesting Topics to Research On for Bored AF People (desi version)

The Bengal Sultanate

Dominance of taka in Silk Route Trade

Tibetan Buddhism

Chamba Rumal

Pashupati Seal

Zeb-un-nissa Begum

Rasa theory of Natyashastra

Gargi-Yajnavalkya Dialogue

Saraswati (River and Goddess)

Rudraveena

Atman-Brahman Relation and Mahavakyas

70's Bollywood fashion

Paintings of Raja Ravi Varma

Dhrupad

History of Chai/Cha

Mother Goddess Mohenjo Daro

Chanakya

Prakrit Language

Baro-Bhuiyan

Chicankari

Brajabuli

Tantra

Shipton–Tilman Nanda Devi expeditions

Banaras

Annamalaiyar Temple

Chola Dynasty

Pala Empire

Terracotta Temples of Bengal

#desiblr#desi#desi tag#desi tumblr#desiposting#desi humor#being desi#desi academia#nerd stuff#school#desi history#pop culture#bollywood songs#hindustani classical music#the nerd speaks#trust me this works#best way to start the day

745 notes

·

View notes

Text

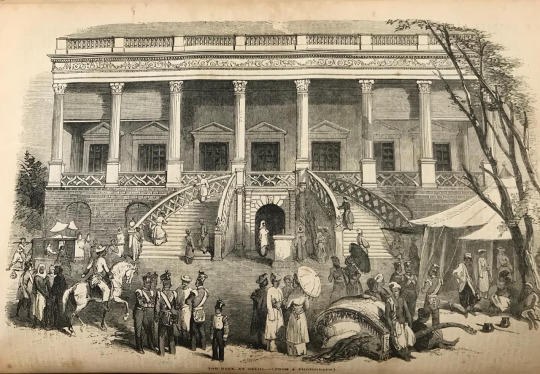

Portrait of Begum Samru, born Farzana Zeb un-Nissa, married Christian name Joanna Nobilis Sombre (c. 1753-1836)

Unknown artist, Delhi School

watercolour on paper

Delhi, India, c. 1830

Starting her career as a dancing (nautch) girl, Begum Samru eventually converted from Islam to Christian Catholicism and became the ruler of the small territory of Sardhana in present-day Uttar Pradesh. She was the head of a professionally trained mercenary army consisting of Europeans and Indians that she inherited from her European husband, Walter Reinhardt Sombre after his passing in 1778. She built several palaces including at Chandni Chowk in Delhi. Stories have been written about her political and dipolomatic astuteness and the important battles fought by the troops under her command. This painting follows the format of a portrait miniature on ivory but is larger and on paper surrounded by a lavish decorative border. She is depicted older in age with her right hand holding the end of a hookah pipe. It may have been part of a set of portraits of Indian rulers of the 19th century.

#begum samru#Joanna Nobilis Sombre#Delhi school#art#watercolour#India#1830s#19th century#history#women

27 notes

·

View notes

Note

Who is your favorite "unknown" mughal princess? By unknown I mean like women like Gauhar Ara begum, Nadira Banu begum, Zinat un nissa begum who were not documented so well.

*laughs*

Anon, that is a dangerous topic to get me started on. I have quite a few (and I'm omitting some of the big names that I also adore: Arjumand Banu, Mihrunissa, Hamida Banu Begum, etc.)

Khanzada Begum- Babur's sister, and--depending on which version you believe--either abandoned or straight up sold to Babur's enemy Shaybani Khan during Babur's escape. But! she wound up surviving both her marriage to the enemy, and returned to her now-victorious brother, subsequently marrying again under happier circumstances and becoming (according to some sources) the first Padishah Begum* of the empire.

*I feel like people often mistranslate this title as "Empress" or "Emperor's favorite wife," but it could just as often mean a beloved sister or daughter--basically, it was the most important woman in the royal family, and the one who effectively claimed the most power.

Gulbadan Begum - half-sister of Humayan, historian, and straight up nerd. Wrote her brother's biography, and delighted in telling embarassing anecdotes about him like any proper sibling. Loving aunt to Akbar; clever, independent, and fun.

Mah Chuchak Begum - widow of Humayan, ruler of Kabul (initially in the name of her son, apparently later just gave up on the pretense and ruled by herself). A hurdle in the path of the young Akbar's consolidation of the empire, she was unfortunately killed by her son-in-law. That said, years later, after her son had managed to piss off Akbar, her daughter Bakht-un-Nissa Begum wound up inheriting the governship of Kabul and apparently did a bang-up job of it.

Aram Banu Begum- Akbar's younger and favorite daughter, and explicitly a smart-aleck. Apparently Did Not get along with her half-brother Jahangir, to the point that one of Akbar's dying wishes was that the two get along. Never married, but seems to have been more a personal choice, rather than a strict decree against it. Seems to have been A Lot, in the best of ways.

Nadira Banu Begum- wife of Dara Shikoh, arguably in one of the happiest marriages of the dynasty. Dara never married anyone, and like her mother-in-law before her, Nadira joined her husband in exile and revolution. He apparently gave most of the paintings he loved to create to her, which is adorable; and did not survive her death by more than a few months.

Dilras Banu Begum - wife of Aurangazeb; apparently haughty and beautiful, and not a little terrifying. Interestingly, she was a devout Shia while Aurangazeb was a devout Sunni (to be fair, Shah Jahan and Mumtaz Mahal were also a very happy Sunni/Shia pair, but both Dilras and Aurangazeb were famously pious and much more religiously fixated than the prior generation). Died before her husband became Emperor, but her children would succeed him.

Zeb-un-nissa (&her siblings) - daughters of Aurangazeb, and talented poets, scholars, and artists. Particularly notable because while pop cultures has the later Mughal empire portrayed as either a joyless husk, or a decadent waste -- these women were clear contraindications to that generalization.

(I could go on, but these are the first few that come to mind!)

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm reading Zeb-un-Nissa's poetry for the first time and I'm not okay.

#i know very little about her honestly just the introduction and short video essay#but strike me why don't you?#I truly feel it's such a waste I can't read every language ever written

1 note

·

View note

Text

Like all intimidating women, Begum Samru too was once branded a witch. In the 18th-century, it was one way to explain the power emanating from this slight, pale Kashmiri nautch girl who commanded an army of deadly mercenaries and ruled a kingdom in present-day Uttar Pradesh. Farzana Zeb un-Nissa was a teenager eking out a living in one of Delhi’s red-light districts in the late-1760s when she met Walter Reinhardt Sombre aka Samru. She made a quick study and soon rose in the esteem of her partner’s army of renegade fighters. When Samru died, his Begum became the supreme commander and under her leadership, the army won decisive victories against the British and Sikhs. She also took over as the ruler of Sardhana, a kingdom awarded to her partner by Shah Alam II. Begum Samru’s haveli in Chandni Chowk was once a pleasure palace complete with fountains, gardens, classical Greek columns and dramatic, sweeping stairways. It’s a sadly reduced spectacle today. After the Begum’s death, the haveli was bought by Lala Bhagirath Mal whose family lived there till the early 1970s. From there the structure slid steadily into a state of disrepair. Most modern Delhiites wouldn’t know that their go-to destination for cheap electronics, Bhagirath Market, was once the fantastical abode of a queen. Sarmaya

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Zeb-un-Nissa (Persian: زیب النساء) (15 February 1638 – 26 May 1702) was a Mughal princess and the eldest child of Emperor Aurangzeb and his chief consort, Dilras Banu Begum. She was also a poet, who wrote under the pseudonym of "Makhfi" (مخفی, "Hidden, Disguised, Concealed One").

Imprisoned by her father in the last 20 years of her life at Salimgarh Fort, Delhi, Princess Zeb-un-Nissa is remembered as a poet, and her writings were collected posthumously as Diwan-i-Makhfi (Persian: ديوانِ مخفى) - "Complete (Poetical) Works of Makhfi".

#Zeb-un-Nissa#Mughal Empire#XVII century#XVIII century#people#portrait#paintings#art#arte#women in literature

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zeb-un-Nisa, Aurangzeb’s eldest daughter, is born in Daulatabad in 1638 when Aurangzeb is governor of the Deccan. While Daulatabad fort dominates the horizon from a hilltop, Aurangzeb is building a new capital at Khadki town, stronghold of Jahangir’s old nemesis, Malik Ambar the ‘rebel of black fortune’. Malik Ambar is now long dead, having never allowed the Mughals to claim the Deccan while he lived. Zeb-un-Nisa, daughter of the Persian noblewoman Dilras Banu Begum, grows up in this provincial capital, far from the intrigues of the Mughal court. In the Deccan, the supremacy of her father is unchallenged and Zeb-un-Nisa is given a rigorous education under the supervision of Hafiza Mariam, a scholar from a Khurasani family. Zeb-un-Nisa is an excellent student and excels in the Arabic and Persian languages. Her father is so delighted when she recites the entire Quran from memory as a child that he gifts her 30,000 gold mohurs. In her erudition and her quick wit she is very like her aunt, Shahzaadi Jahanara, whom her father respects above all the other women of the court. When she is fifteen years old, she visits Shahjahanabad with Aurangzeb’s zenana as they return from the doomed Kandahar campaign. She is enchanted with the sparkling new city, the elegant women with their refined tehzeeb, their every gesture studied and full of grace. In the travelling court of her father, in these wildering years, it is a more pragmatic and pared down zenana but in 1658, when Zeb-un-Nisa is twenty years old, Aurangzeb deposes Shah Jahan and his household moves to Shahjahanabad.

Dilras Banu Begum, the somewhat haughty senior wife of Aurangzeb, is now dead. Even Aurangzeb, when giving marital advice to a grandson, will later admit that ‘in the season of youth’, he ‘too had this relation with a wife who had extreme imperiousness’. Since the other wives of Aurangzeb have less illustrious backgrounds, the senior women of the royal zenana are Roshanara and her eldest niece, Zeb-un-Nisa.

For twenty years Zeb-un-Nisa will be one of the most influential women of the zenana at Shahjahanabad. Her particular area of interest is poetry and literature. She collects valuable manuscripts and books and her library is one of the most extensive in the country. When Aurangzeb begins to retrench imperial patronage towards music and poetry, it is the royal women, the shahzaadas, the noblemen and then, later still, the wealthy middle class of Shahjahanabad who will continue the patronage of the arts. The governor of Shahjahanabad, Aqil Khan, is himself a poet and writes under the pen name Razi. Indeed, despite Aurangzeb’s later disfavour, Shahjahanabad fairly pulses with music. It tumbles from the kothis of the courtesans, the women thoroughly trained singers themselves, who bring Delhi Qawwali singing to mainstream attention. It vaults out of the large mansions of the newly wealthy, who prefer the lighter Khayaal and Thumri styles. In the gloaming of a tropical evening, it throbs out of the immense havelis of the princes and the noblemen, in the tenuous hold that Dhrupad still has amongst the elite of the Mughal court. And the poets keep gathering at Shahjahanabad, despite Aurangzeb’s dismissal of them as ‘idle flatterers’. They come from very far, like Abd-al-Qader Bidel, whose family is Chagatai Turkic but whose poetry so defines a phase of Shahjahanabadi poetry that he becomes Abd-al-Qader Dehlvi. Some will come from the Deccan, like Wali Dakhni, and some are born in the narrow, winding galis (lanes) of Shahjahanabad itself. They will write in Persian, in Urdu, in Braj and later in Rekhti. They will write in obscure philosophical quatrains, in flamboyant ghazals or in erotic riti styles but many will glow with the high-voltage mysticism of Sufi thought, for the ghosts of Shahjahanabad’s Sufi saints will enchant all the poets of the city.

Zeb-un-Nisa, like Jahanara who returns to court as padshah begum in 1666, is instrumental in supporting the work of writers and poets through her patronage. She supports the scholar Mulla Safiuddin Adbeli when he translates the Arabic Tafsir-i-Kabir (Great Commentary) into Persian and he dedicates the book to the shahzaadi—Zeb-ut-Tafasir. She also sponsors the Hajj pilgrimage of Muhammad Safi Qazwini. Qazwini will write an extraordinary account of his voyage, the Pilgrims’ Confidant, unique in its genre and magnificently illustrated and will dedicate it to Zeb-un-Nisa. For a few years, the courts of Jahanara and Zeb-un-Nisa will nurture this eclectic maelstrom of a culture, which has much more in common with Babur and Humayun’s camaraderie of artists than it has with Aurangzeb’s increasingly austere one. When Aurangzeb bans opium and alcohol, the easy complicity that the noblemen and padshahs shared in the ghusal khaana or the Deewan-e-khaas while drinking wine, is now forbidden. The imperial women, however, continue to drink wine, often made from grapes in their own gardens, flavoured with spices.

In 1669, Zeb-un-Nisa attends the lavish marriage ceremony of her cousin, Jaani Begum, to her brother, Muhammad Azam, at the haveli of Jahanara. There will be other weddings too: her sister Zubdat-un-Nisa will marry Dara Shikoh’s youngest son Siphir Shikoh and Mehr-un-Nisa will marry Murad Baksh’s son Izad Baksh. But for Aurangzeb’s oldest daughters, there are no more cousins to marry. There is an understanding, also, that these oldest daughters, like their aunts, possess a powerful charisma as Timurid shahzaadis and must be kept within the controlling orbit of the imperial zenana. The decades pass and still Aurangzeb rules, as resolute and restless as a young man. His sons, meanwhile, are growing old and impatient. Muhammad Akbar is Zeb-un-Nisa’s youngest brother and she is particularly close to him, as their mother Dilras Banu died soon after giving birth to him, when Zeb-un-Nisa was nineteen. The other sons are middle-aged men, and there have been skirmishes, the shahzaadas jostling for power, always subdued immediately by their unforgiving father. In 1681, when Muhammad Akbar decides to challenge his father, with the support of a Rajput alliance including the Rathors of Jodhpur, Zeb-un-Nisa is in a particularly vulnerable position.

In 1681, Jahanara dies. The imperial zenana has glowed with her ambition and talent for more than half a century. If the shahzaadas are uncertain about the future leadership of the Mughal empire, then the stakes are almost as high in the imperial zenana. Zeb-un-Nisa believes she may become the next padshah begum. She is a woman of letters, like Jahanara, with the same Sufi inclinations too. She is the eldest of the Timurid shahzaadis and presides over an astonishingly talented salon. It is time, surely, for a shahzaada to ascend the Peacock Throne as Aurangzeb is already an old man, sixty-three years old. So Zeb-un-Nisa sides with the young prince Muhammad Akbar, hoping to ensure her legacy in the next court.

But Aurangzeb is able to defeat Muhammad Akbar, using a mixture of duplicity and treachery. In the process, he discovers letters which incriminate Zeb-un-Nisa, demonstrating her ardent support for her brother. ‘What belongs to you is as good as mine,’ Muhammad Akbar writes in a letter to Zeb-un-Nisa, ‘and whatever I own is at your disposal.’ And in another letter he writes: ‘The dismissal or appointment of the sons-in-law of Daulat and Sagar Mal is at your discretion. I have dismissed them at your bidding. I consider your orders in all affairs as sacred like the Quran and Traditions of the Prophet, and obedience to them is proper.’ Muhammad Akbar is exiled to Persia, and Zeb-un-Nisa is imprisoned at the Salimgarh fort in Delhi. Her pension of four lakhs rupees a year is discontinued and her property is seized.

Very soon after this rebellion, Aurangzeb leaves Shahjahanabad for the Deccan with an entourage of tens of thousands, all of his sons and his zenana. He will never return to Shahjahanabad, which will slowly be leached of all of its nobility, craftsmen, soldiers and traders. Zeb-un-Nisa will live more than twenty years imprisoned in Salimgarh fort. She will grow old here as Shahjahanabad empties of its people and becomes a shadow of its former self. But the poets and the singers do not desert Shahjahanabad, their fortunes and their hearts are too inextricably linked to the great city, to this paradise on earth. Other patrons take over the role of the nobility, humbler people, so that a critical poet will later write:

Those who once rode elephants now go barefooted; (while) those who longed for parched grains once are today owners of property mansions, elephants and banners, (and now) the rank of the lions has gone to the jackals.

Not only do the poets remain but their poetry becomes saturated with the haunted longing and nostalgia which becomes the calling card of all the great poets of Delhi. This city of beauty and splendour, abandoned and then desecrated, and then bloodied, will inspire reams of poetry on the twin themes of grief and remembrance. In the future, one of these poets will court eternity when he writes:

Dil ki basti bhi Sheher Dilli hai;

Jo bhi guzra usi ne loota

As for Zeb-un-Nisa, she waits for Muhammad Akbar to claim the Peacock Throne but he dies, in 1703, outlived by his father. From her lonely prison on the Yamuna, the shahzaadi can see Shah Jahan’s magnificent fort. The Qila-e-Mubaarak remains locked up for decades and the dust and ghosts move in. The bats make their home in the crenelated awnings and sleep as the relentless sun arcs through the lattice windows. Bees cluster drunkenly around the fruit trees in the Hayat Baksh, the overripe fruit crushed on the marble walkways like blood. Moss skims over the canals and the pools, though the waterfall still whispers its secrets to itself in the teh khana (underground chamber) as Zeb-un-Nisa waits. Zeb-un-Nisa writes poetry while she waits for a deliverance that will never come. She is a poet of some repute, and writes under the pseudonym Makhvi, the Concealed One. This is a popular pseudonym, however, and it is difficult to establish which lines are truly written by the shahzaadi but it is likely that the following wistful and delicate lines are hers, written in the grim solitude of Salimgarh fort:

Were an artist to choose me for his model—

How could he draw the form of a sigh?

She dies in 1702, unforgiven by Aurangzeb, and is buried in the Tees Hazari Garden, gifted to her by Jahanara.

- Ira Mukhoty, “Daughters of the Sun: Empresses, Queens and Begums of the Mughal Empire”

#history#historicwomendaily#indian history#india tag#mughal empire#mughal era#Zeb-un-Nissa#mine#queue

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

requested by anonymous

↳ notable female poets

#historyedit#history#weloveperioddrama#perioddramaedit#wallada bint al mustakfi#11th century#spanish history#16th century#sultanate of women#turkish history#ottoman history#17th century#indian history#Zeb-un-Nissa#20th Century#american history#21st century#ntozake shange#japanese history#9th Century#ono no komachi#polish history#rromani history#bronislawa wajs#italian history#19th Century#elizabeth margaret chandler#veronica franco#our edits#by julia

200 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dearest, my secret is now unveiled. And yes, I am thirsting. Thirsting like a madwoman. I am thirsting to drink of my own blood, to shed it abroad like a sea, to sacrifice all I have ever desired. To die as a victim for you

- The Diwan of Zeb Un-Nissa, address to God

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

5 Famous Female Authors Who Wrote Under Male or Androgynous Pen Names

Throughout history, authors in all genres have used pseudonyms for a variety of reasons, sometimes writing under as many as three, or four--or more!--pen names. Today, in honor of International Women’s Day, we’ve compiled a list of some of the most influential women writers who have had to write under male or androgynous monikers at some point in their careers:

1. Zeb-un-Nissa

(1630-1702)

Zeb-un-Nissa was an Imperial Princess of the Mughal Empire in India. She was a dedicated scholar, and fluent in three languages (Persian, Arabic, and Urdu). She is said to have loved reading so much that her personal library became the best in the Empire.

Zeb-un-Nissa was also an accomplished poet, and started writing and reciting her own poetry as early as 14 years old. Although her father, Emperor Aurangzeb, disapproved of her writing, she continued to do so under the male name “Makhfi”, which generally translates to “The Hidden One”.

Later in her life, Zeb-un-Nissa was arrested and imprisoned. Accounts vary on the reason for her imprisonment, but one theory is that her poetry threatened the austere, orthodox rule of her father. Although she died after many years in prison, her poems continue to be popular.

Via an excerpt from the Library of Congress website.

2. The Brontë Sisters

(1816--1855)

Ok, so this means our list technically contains more than five authors. But we found it impossible to pick a favorite from the three sisters.

Although the names of Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Brontë are now well-known to everyone from high school students to classic novel enthusiasts, this was not always the case. When they began publishing their novels, the Brontë sisters used the male pseudonyms Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell, respectively.

Charlotte summed up their reasoning for using the aliases best: “We did not like to declare ourselves women, because–without at that time suspecting that our mode of writing and thinking was not what is called ‘feminine’–we had a vague impression that authoresses are liable to be looked on with prejudice.”

Via Heather Armitage in this article for Culture Up.

3. Pearl S. Buck

(1892--1973)

Despite critical acclaim--including receiving a Pulitzer Prize for her novel The Good Earth and a Nobel Prize for Literature--Pearl S. Buck sometimes wrote under the masculine pseudonym “John Sedges” in the later stages of her career.

In her own words, Buck said that she chose a masculine pen name “because men have fewer handicaps in our society than women have in writing as well as in other professions.” She also felt that female authors “are not taken as seriously as men, however serious their work. It is true that they often achieve high popular success. But this counts against them as artists.”

Via Vanessa Künnemann in Middlebrow Mission: Pearl S. Buck's American China.

4. Alice C. Browning

(1907--1985)

Alice C. Browning was an American teacher, writer, editor, and publisher. She lived and worked in Chicago, where she created platforms to highlight African-American voices in literature. From 1944 to 1946, Browning published a literary magazine, Negro Story, and later founded and directed the International Black Writers Conference.

In the words of Professor Bill V. Mullen in Writers of the Black Chicago Renaissance:

“Browning’s stories appeared regularly in Negro Story. Nearly always she wrote under the pseudonym ‘Richard Bentley.’ This possibly reflected her desire to mask her role as editor and writer for the magazine. It also was a symbolic reminder, for readers and friends who knew her, of the impetus for starting the journal: namely the feeling that Black women and women writers in particular were being shunned by mainstream literary markets. The pseudonym also gave Browning perhaps playful free rein to write and publish stories that foregrounded taboo gendered and racial themes.”

5. Joanne Rowling

(1965--Present)

It’s hard for us to imagine an alternate universe where Harry Potter isn’t one of the bestselling book series of all time. But before Harry ever took his first trip to Hogwarts, publishers weren’t so sure that the book would be a blockbuster hit.

Before the release of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, publishers were concerned that young male readers would refuse to pick up a book penned by a female author. They convinced author Joanne Rowling to go by the non-gender-specific initials “J. K.” to draw in that demographic of readers. (Fun fact: Ms. Rowling does not, in fact, have a middle name. She chose the “K” in honor of her grandmother, whose name was Kathleen.) In an interview, Rowling commented: "It was the publisher's idea; they could have called me Enid Snodgrass. I just wanted it [the book] published."

Via Richard Savill in this article for The Telegraph.

While it may seem hard to imagine that publishers could still carry a (conscious or unconscious) bias against women--especially after success stories like Rowling’s--some recent social experiments have shown that this is still an issue. In honor of National Women’s History Month, let’s celebrate and recognize all the amazing women who write.

#nanowrimo#international women's day#national women's history month#writers#writing#Zeb-un-Nissa#the bronte sisters#pearl s. buck#Alice C. Browning#j. k. rowling#reading#women

582 notes

·

View notes

Text

The time of spring is past,

The rose-leaves in the garden drift apart,

Among the trees the bulbul sings no more.

How long, madness, shalt thou hold my heart!

How long, exaltation, shalt thou last

Now spring is o'er ?

- Zeb-Un-Nissa

25 notes

·

View notes