#and William Seamen

Text

Fox's Book of Martyrs

https://www.biblestudytools.com/history/foxs-book-of-martyrs/

Edited by William Byron Forbush This is a book that will never die — one of the great English classics. . . . Reprinted here in its most complete form, it brings to life the days when “a noble army, men and boys, the matron and the maid,” “climbed the steep ascent of heaven, ‘mid peril, toil, and pain.” “After the Bible itself, no…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

"Strike Continues: "White Collar” Men Unloading Lake Steamers," The Province (Vancouver). September 11, 1943. Page 3.

---

(By Canadian Press.)

FORT WILLIAM, Sept. 11. - Third day of the strike of 550 freight handlers at lakehead docks opened today with "white collar" workers helping to unload a cargo from the steamship Keewatin, C.P.R. passenger and package freight carrier.

The men are on strike in protest of the War Labor Board's failure to deliver a ruling on an application for increased wage rates.

The Keewatin, scheduled to leave at 1 p.m. for eastern ports, will be delayed several hours, it was announced.

#thunder bay#stevedores#longshoremen#canadian sailors#strike#union demands#union men#seamen's union#lakers#freighter#great lakes#scabs#strikebreakers#working class politics#working class struggle#canada during world war 2#fort william

0 notes

Text

South Wales Police Apology 70 Years After Hanging Injustice

The family of #MahmoodMattan a #Somaliland-#British father who was #wrongly convicted of #murder have been given a #police #apology 70yrs after he was executed. While the family welcomed an apology, one of his 6 #grandchildren has called it "#insincere."

(more…)

View On WordPress

#Black Lives Matter#British Somalilander#Cardiff#Injustice#Laura Williams#Lily Volpert#Mahmood Mattan#Race#Seamen#Somaliland#South Wales Police#United Kingdom (UK)#Wales

0 notes

Text

The Painted Hall, Greenwich

During the king’s coronation I visited Greenwich's "Painted Hall." This series of rooms depict scenes relating to the success of British Protestantism and the beginning of burgeoning imperial expansion. Following the vital English naval victory over France at La Hougue in 1692, Queen Mary ordered that a hospital be built for retired seamen, in keeping with the existing hospital for former soldiers at Chelsea.

While Mary died before its completion her husband, William III, saw the projected through. Sir Christopher Wren (of St Paul’s fame) and his assistant, Nicholas Hawksmoor, designed a grand series of buildings at Greenwich, in London.

The Royal Hospital at Greenwich acted as a retirement home for sailors between the 1700s and late 1900s. And at its heart is the Painted Hall, a series of rooms where a relatively unknown artist, James Thornhill, was commissioned to paint scenes of British-Protestant triumph.

At the centre is King William III and Queen Mary shown overseeing ‘The Triumph of Peace and Liberty over Tyranny.’ Immediately above the couple and to their left is the allegorical figure of Prudence holding a mirror, one of the four Cardinal Virtues.

To her right are Providence and Concord, while to her left is Justice. Beneath Justice is a woman representing Europe, who is accepting the ‘cap of liberty,’ the ancient red Phrygian cap, from William, who in turn is accepting an olive branch from ‘Peace.’

Beneath William’s foot is the defeated Louis XIV of France with a broken sword, and a tumbling, discarded papal crown. Beneath them the ‘Spirit of Architecture’ along with Truth and Time are overseeing plans showing the actual construction of the hospital.

Above it all, Apollo rides his chariot, while the signs of the zodiac are arrayed around the edges. At the bottom, Pallas Athena and Hercules crush the Hydra and the Gorgon, ‘expelling the Vices from the Kingdom of William and Mary.’

Another section of the ceiling shows a captured Spanish galley laden with the spoils of war, a reference to the British capture of Gibraltar in 1704. Diana, Goddess of the moon, passes mastery of the tides over to British sailors. Beneath them are representations of the English rivers Avon, Severn and Humber.

To the left and the right, scientific advancement is celebrated by the presence of astronomers Tycho Brahe, John Flamsteed, Copernicus and Newton’s ‘Principia.’ The gods Neptune and Cybele oversee it all.

The next section of the ceiling shows HMS Blenheim being filled with the spoils of war by the winged figure of Victory. Beneath are more river representations along with the City of London and figures representing navigation and astronomy. On the left is Galileo, while Zeus and Juno watch from above.

The painted hall took decades to complete, and saw further dynastic change, as George I, originally of Hanover, became king after William III’s successor, Queen Anne, died. George maintained the Protestant ascendancy, as portrayed in the upper hall chamber adjoining the main hall.

Here we see George I, his wife Sophia of Hanover and their children and grandchildren beneath St Paul’s, overseen the a figure representing “the Golden Age” with overflowing cornucopia. The artist, James Thornhill, added himself on the right.

Over them is an inscription quoting Virgil's Eclogues, which translates as ‘a new generation has descended from the heavens.’

On the left of the upper hall is a depiction of William III’s arrival in England at the start of the Glorious Revolution in 1688, while George I is shown arriving on the opposite side of the hall (rather unrealistically in a chariot) in 1714.

#painted hall#the painted hall#greenwich#history#british history#art#art history#william iii#william of orange#william and mary#george i#queen anne#17th century#18th century

132 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! I don't know if this is exactly your wheelhouse, but I was reading about Fredrick Douglass and it briefly mentioned that he used a Seamans protection certificate in his escape from slavery; I was wondering if you had any thoughts/ info about these as it relates to Black seamen in the US, especially the South. If not, absolutely no worries! Love your blog.

Oh yeah, I went down a rabbit hole sometime back about seamen’s protection certificates in the context of what they meant for Black mariners and US Citizenship!

To summarize that above post, Seamen’s Protection Certificates spoke to the contradictory legal status of Black mariners in the antebellum US when naturalization was only accessible to white men. It’s a paper that says that one is a US citizen, but was not considered ‘valid’ documentation for accessing the rights of a US citizen. But for all intents and purposes, it still signaled that the man in question was indeed a citizen when abroad. This contradiction (as well as other legal contradictions) was leveraged by people fighting for access to naturalization and a full legal identity for African Americans.

But while the certificate did not truly grant citizenship to Black sailors, it still served as a form of protection both in states where slavery was law, as well as ‘free’ states, where the Fugitive Slave Act quickly destabilized any sense of security one might have there. The seamen’s protection certificates had only a brief vague description of the holder. As such, some free Black men would take the risk of loaning their papers out to those escaping enslavement who roughly matched the written description, similar to how States’ ‘free papers’ were also loaned out for the same purpose. As Douglass mentioned in his autobiography concerning his use of said papers:

“But I had one friend—a sailor—who owned a sailor’s protection, which answered somewhat the purpose of free papers—describing his person and certifying to the fact that he was a free American sailor. The instrument had at its head the American eagle, which at once gave it the appearance of an authorized document.”

Nearly 1/3rd of applications for seamen’s protection certificates were made by men of color because of the protection they afforded against being kidnapped into slavery. Even though there was a lot of backpeddling from officials saying that the protection certificates didn’t REALLY mean citizenship, it was still an official document stating someone’s freedom and thus had tremendous value in allowing a man to move freely through the world. Here’s an old but good article about seamen’s protection certificates in general that speaks a little more to that.

In the context of mariners in the South, here are some examples. This one, from the National Archives is for a man named William Wright, from Viriginia who applied for a certificate in New Orleans in 1810.

And another from the collections of Mystic Seaport of a man named Jonathan Miller, born in New York but applying for the paper in Galveston Texas. The language is a bit different from the boilerplate seamen’s protection certificates like the one above, so I think it’s slightly different as a legal document—but still, in 1856, would hold the same sort of odd wobbly status.

The museum’s interpretation of this was that it was likely applied for and used as a form of protection in moving freely through the South, rather than Mr. Miller specifically using it for a maritime purpose.

209 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rereading The Terror

Oh gang... oh gang you're not going to like this one...! :(((

Big spoiler at the end so I'll put it all under the cut just in case.

Chapter Forty-Seven: Peglar

As they strike camp and begin to haul the boats out onto the ice toward the new leads, Peglar reflects on the near-mutiny - he heard all about it from Bridgens of course who saw the whole thing first-hand from the medical tent where he'd been assisting Goodsir.

Peglar always thought of Hickey, Manson, Aylmore et al as treacherous shits and so he's more surprised and offended to find out about the previously loyal men who also took part - his Erebus counterpart Robert SInclair, for instance, and Reuben Male who he describes as "a dependable man, but strong-willed. Very strong-willed."

Hauling across the ice again is hard-going, not just because of all the peaks and troughs to negotiate but also because it's getting thinner. Private Daly, scouting ahead to test said thickness, falls straight though into the water at one point - Goodsir has him stripped naked then and there on the ice, bundled up with two other men in layers of blankets and sleeping bags and even then he only just survives.

Peglar is worried of course, and the thought of open water makes his heart flutter which in turn has him reflecting on a childhood including scarlet fever and chronic chest pains. He's been so crippled with his throughout his life that he's often had to climb the rigging one-handed due to the shooting pains in his left arm - "The other foretopmen thought he was showing off."

As they progress further, Crozier places a boat hauled by Lieutenant Hodgson, Hickey, Manson, and Aylmore among others, at the head of the procession and in the position of greatest risk. Every man there knows it's a punishment and Peglar hasn't much sympathy at all:

"Peglar thought that young Hodgson looked as if he might weep. He knew how hard it must be to be in your twenties and know that your Naval career was over. Serves him right thought Peglar. He'd spent decades in a navy that hanged men for mutiny and lashed them for the mere thought of mutiny, and Harry Peglar had never disagreed with either the rule or the punishment."

Once they final reach the open water proper, Crozier assigns Peglar to the boat that will be lowered into it to scout the lead out fully. Lieutenant Little will lead the men, along with Ice Master Reid and a select group of seamen including William Wentzell, Alexander Berry, and Henry Sait.

Crozier expresses trust in Peglar specifically, and clearly values his input on the viability of the lead - "I need a good man on the sweep oar and a third assessment as to whether this lead is a go."

Once in the water, their journey is relatively uneventful. The lead narrows at several points and is blocked at others but every time they manage to find a way past until finally, they emerge into a massive lake of clear blue water in the middle of the ice with several huge flat bergs floating in it.

"We could camp on 'aton and have plenty of room left over," said Henry Sait, one of the Terror seamen at the oars.

"We don't want to camp," said Lieutenant Little from the bow. "We've had enough camping for a fucking lifetime. We want to go home."

They literally start to sing with happiness as they row their way out into the lake but soon enough that joy fades as they find no way out of it except the way they came in. Little even boosts Berry up onto Wentzell's shoulders to scout all round with a telescope but the ice is thick and impenetrable. Dejected, they make their way back to their entry point, which they marked with a pike.

But something is wrong...

It's Peglar who notices it - a big ice boulder right next to that way-marking pike that wasn't there before...

Little understands what that means straight away, orders the men to row backwards away from it, but it's already far too late. Then comes one of the simplest but best and most utterly chilling lines in this whole godforsaken book -

"The ice boulder turned."

#The Terror#The Terror AMC#Observations#Random Observations#Meta#Rereading the Terror#Terror Spoilers#Henry Peglar#Edward Little#Francis Crozier#Apologies but I'm not tagging everyone#God imagine if they'd included this in the show though!

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

I got curious about how 19th century newspapers actually reported on storms and shipwrecks. Here's an example from the Teesdale Mercury, 29th January 1890:

RESCUED IN MID-OCEAN

The liner Gallia brings particulars of the rescue of 18 mariners in the North Atlantic by Captain Munro, of the British steamship Stag, on the 29th ult [?], while on a voyage from Shields to New York. The sinking ship was the old American clipper-built ship Shakespeare, and the crew had already been left to their fate by one passenger steamer, and had abandoned all hope. Captain Munro in his account says the wind was blowing at hurricane force, and his ship was making its way through big seas when the wreck was seen through a veil of hail and rain. He made for the vessel, and found it was a dismasted ship, wit h the crew waving and shouting in a frenzy of despair. He continues: " At that time it was blowing a frightful hurricane, and a boat could not have lived a moment in the seas. Shortly after a heavy snow squall shut out the fast-sinking ship, and all that day and night the vessel was obscured, but every once in a while we could see the flash of lights and rockets telling us where they were. All that night we sailed about the ship, hoping that the storm would abate sufficiently to allow us to go to the crew's succour. For hours we could not see their distress signals, and it gave me intense anxiety for fear I would lose them. When morning dawned I again made a search for the ship. After hours of fruitless endeavour the snow squall suddenly ceased, the mist cleared away, and disclosed the ship to our view. She was almost level wit h the water. The sea was still frightfully high, but I knew that the crew's safety depended upon m y promptness. I ordered away the port quarter boat and called for volunteers to man it . Every one of my crew to a man instantly responded. Second-officer Noell and four of my

ablest seamen manned the first boat and rowed to the rescue. On account of the heavy sea the boat could not get within 50ft. of the sinking ship. Then those on the ship threw my men a line. I shouted to everyone to put a lifebelt on and jump into the sea, and then, with the aid of the rope, pull themselves through. Owing to the sea my lifeboat could only rescue five men the first time, and it made four successive trips, each of the men having first to jump into the sea, and then, with the aid of the line which was attached to the ship, swim towards the lifeboat. On the two last trips a fresh crew of volunteers, in charge of First-officer William Hanson, went to the wreck. Chief-officer Fred Matte, the last person to leave the sinking vessel, could not hold on to the rope, his hands being so sore and blistered from exposure and cold, and had to swim the whole distance, my men dragging him out of the water benumbed and exhausted. The rescue, although attended with the gravest difficulty, was successfully accomplished, and the conduct of my men and the presence of mind displayed by the Shakespeare's crew are deserving of the highest praise. We abandoned the ship and the late captain's pet dog to the mercy of the elements, and continued on our trip . The rescued men were weak and exhausted from fatigue and exposure, and were one mass of bruises and sores. They had been tossing about the Atlantic for nearly three months, having left Hamburg on Oct. 24. Their ship was dismasted in a gale on Dec. 17, in which she also sprang a leak. For four days and nights, amid frightful hurricanes, the big seas constantly sweeping over them, the brave crew manfully worked at the pumps in a hopeless endeavour to keep their ship afloat. Capt. Mullar died from heart disease on Dec. 16, and just as a big sea swept his ship on the following day, hurling the mizenmast wit h part of the mainmast to the deck, his body was buried in the sea."

Who knew that one of the areas where Bram Stoker allowed himself creative licence was the inclusion of paragraph breaks?

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Male and female slavery was different from the very beginning. As noted previously, women did not generally travel the middle passage in the holds of slave ships but took the dreaded journey on the quarter deck. According to the 1789 Report of the Committee of the Privy Council, the female passage was further distinguished from that of males in that women and girls were not shackled. The slave trader William Snelgrave mentioned the same policy: “We couple the sturdy Men together with Irons; but we suffer the Women and children to go freely about.”

This policy had at least two significant consequences for black women. First, they were more easily accessible to the criminal whims and sexual desires of seamen, and few attempts were made to keep the crew members of slave ships from molesting African women.3 As one slaver reported, officers were permitted to indulge their passions at pleasure and were “sometimes guilty of such brutal excesses as disgrace human nature.”"

- Ar'n't I a Woman? Revised addition by Deborah Gray White

#intersectional feminism#feminism#book quotations#feminist literature#feminist#feminist theory#intersectional feminism 101#intersectionality#intersectional politics#anti slavery#slavery tw#racism tw

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

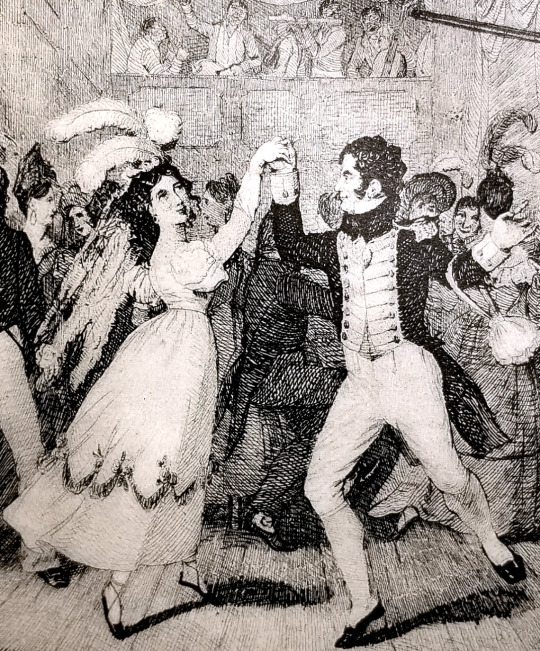

Quadrilles - practising at home: 1817 print (British Museum)

A passage from S.A. Cavell's Midshipman and Quarterdeck Boys in the British Navy, 1771-1831 on the importance of social dancing for young officers in the 19th century Royal Navy:

Many young gentlemen also began to ascribe greater importance to their participation in good society. Peter Cullen noted the anxiety of the Squirrel’s midshipmen when their captain refused an invitation to a ball given by the Earl of Kinsdale. Some of the more enterprising (and disobedient) among them found a way ashore and ‘had the honour of dancing with the Ladies de Courcy’. In 1807 able seaman Robert Wilson noted the elegance of several parties on board the Unité in which the officers and young gentlemen decorated the quarterdeck, arranged bands and entertainments, and organized refreshments in an effort to entertain local ladies and gentlemen with country dances. A bitter Charles Shaw chastised his parents for failing to send him a new uniform which caused him to miss an important social opportunity: ‘We have all been invited to a Ball at the British Consul’s at this place [Lisbon] but I was obliged to refused as I had no clothes to go in’.

Young gentlemen who paid excessive attention to the pursuits of genteel society risked the ire of more seasoned officers. Later in his career, Admiral Sir Thomas Byam Martin was peeved enough to comment: ‘The rivalry with midshipmen is no longer [over] smartness or professional duties, but in frivolous effeminacy, incompatible with what we wish and expect in the character of seamen.’ For most young gentlemen, however, the cultivation of an elegant manner in the company of polite society was essential to their personal and professional credit.

An 1837 illustration by Robert William Buss for Captain Frederick Marryat’s novel Peter Simple, showing Royal Navy officers and midshipmen dancing at a ball in Barbados in the early 19th century.

#midshipman monday#age of sail#naval history#social dancing#regency#royal navy#midshipmen#country dance#midshipmen and quarterdeck boys#samantha a cavell#robert william buss#frederick marryat#maritime history#dancing

95 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi there! i have a friend who started reading “in the heart of the sea” recently and is now very interested in similar maritime history books - do you have any good recommendations i can give her? thanks so much!

Hello! Most of my interest in maritime history is the lives of everyday sailors, and here are some of my favorite books! They are all nonfiction.

Unruly Desires: American Sailors Homosexualites in the Age of Sail by William Benemann- a look into homosexuality on merchant sailing vessels as well as in the British and American navies. One of my favorites!

Black Jacks: African American Seamen in the Age of Sail by W. Jeffrey Bolster- This one is very good about seafaring Black men from 1740-1865. I highly recommend it as a look into the important role Black sailors played in the maritime history of America.

Charles Benson: Mariner of Color in the Age of Sail by Michael Sokolow- I love this one particularly as a deep dive into the life of one of the hundreds of the men of color who served as sailors during the 1800s. He lived most of his adult life in Salem, MA.

@ltwilliammowett might have some recommendations on maritime disasters too, and they are an expert in shipwrecks if your friend would like to check their blog out!

If your friend is interested more in whaling history in particular have them check out @focsle’s blog! They are currently writing a ghost story comic set onboard a whaling vessel and have a lot of good posts about whaling.

Archive.org has also been a really good resource for reading ship logbooks, and those are a lot of fun.

Hope this is helpful! :)

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Mystery of the Mary Celeste

May 11, 2023

The Mary Celeste ship was built in Spencer’s Island, Nova Scotia and was launched under British registration as Amazon on May 18, 1861. On the registration documents the ship was 99.3 feet long, 25.5 feet broad, with a depth of 11.7 feet.

She had previously been in a wreck in Cape Breton and was very damaged. In November 1868, a man named Richard W. Haines, from New York paid $1,750 (US) for the wrecked ship and spent $8,825 to restore it. In December 1868, the ship was registered to the Collector of the Port of New York as an American vessel under the name, Mary Celeste. Haines also became the captain of her.

In October 1869, the ship was seized from Haines and sold to a New York consortium. For at least three years there is no record of Mary Celeste’s trading activities. In 1872, she underwent a refit that cost $10,000 and her size was increased, and the new captain’s name was Benjamin Spooner Briggs.

In October 1872, Briggs, his wife, and infant daughter took Mary Celeste on her first voyage, after her New York refit, to Genoa, Italy. Briggs had left his school aged son behind to be taken care of by his grandmother.

Briggs chose the crew for the voyage himself, including first mate Albert G. Richardson, second mate Andrew Gilling, 25 years old, the steward was Edward William Head, and four seamen who were German from the Frisian Islands: brothers Volkert and Boz Lorenzen, Arian Martens, and Gottlieb Goudschaal. Briggs and his wife were extremely satisfied with the crew.

On October 20, 1872, Briggs went to Pier 50 on the East River in New York City to supervise the ship loading 1,701 barrels of alcohol. Briggs’ wife and infant joined him a week later.

On Tuesday, November 5, 1872, Mary Celeste left Pier 50 and went into New York Harbor. The weather was uncertain, so they waited for better conditions. After two days, the weather was good enough to begin the voyage, and so Mary Celeste sailed into the Atlantic.

A Canadian ship, Dei Gratia was nearby in Hoboken, New Jersey, waiting on cargo before they set sail. The Captain, David Morehouse, and first mate Oliver Deveau were Nova Scotians who were highly experienced. It was even rumoured that Captain Morehouse and Briggs were friends and had dined together the night before Mary Celeste departed, however the evidence of this comes from Morehouses’ widow 50 years after the event.

Dei Gratia departed for Gibraltar on November 15, 1872, following the same route as Mary Celeste had seven days earlier.

On December 4, 1872, between the Azores and the coast of Portugal, Captain Morehouse on the Dei Gratia was made aware that there was a vessel heading unsteadily towards them about 6 miles away. The ship appeared to be making erratic movements, leading Morehouse to believe something must be wrong.

Captain Morehouse noticed there was nobody on deck when the ship came closer, and they were receiving no replies from their signals. Captain Morehouse sent Deveau and his second mate John Wright in a boat to investigate the strange vessel.

The two men discovered that this vessel was indeed the Mary Celeste, as the name was on her stern, so they climbed onto the ship and found that it had been completely deserted; there was not one person around. The sails were partly set and in poor condition, some were completely missing and a lot of the rigging had been damaged, with ropes hanging over the sides. The ship had a single lifeboat that was missing. The binnacle that had the ship’s compass in it was out of place and the glass cover was broken.

There was 3.5 feet of water in the hold, however that was not suspicious for a ship of that size. A makeshift sounding rod which measures the water in the hold was found abandoned on the deck.

The Mary Celestes’ daily log was in the mate’s cabin, and the final entry date had been at 8 am on November 25, nine days before the ship was discovered. The position was recorded to be about 400 nautical miles from the point where Dei Gratia had found her.

Deveau reported that the inside of the cabin had been wet and untidy from water that had come in through doorways and skylights, however it was mostly in order. There were personal items scattered in Captain Briggs’ cabin, however most of the ship’s papers were missing, along with navigational instruments.

There was no obvious signs of fire or violence, and there was no food prepared or being prepared. It appeared that there had been an orderly departure from the Mary Celeste, the crew using the missing lifeboat.

Captain Morehouse decided to bring Mary Celeste to Gibraltar, which was 600 nautical miles away. Under maritime law, a salvor could get a decent amount of money of a rescued vessel and cargo.

Morehouse divided his crew, and sent 3 members on the Mary Celeste, which he and four other members stayed on the Dei Gratia; however this meant that each ship was very under crewed. Dei Gratia arrived at Gibraltar on December 12, while Mary Celeste arrived the next day due to fog.

The salvage court hearings began on December 17, 1872, Captain Morehouse had written to his wife that he believed he would be paid well for the Mary Celeste salvage. Testimony from Deveau and Wright convinced the court that a crime had been committed, foul play was involved.

On December 23, 1872, there was an examination of Mary Celeste, which reported that there were cuts on each side of the bow, caused by what they thought a sharp instrument. There was also what appeared to be possible traces of blood on Captain Briggs’ sword.

The report stated that the ship did not appear to have been struck by heavy weather, or been involved in a collision. A group of Royal Naval captains also examined the ship and said the cuts on the bow seemed to be caused deliberately. There was also stains on one of the ship’s rails that might have been blood, with a deep mark possibly caused by an axe.

On January 22, 1873, the reports from the court hearings were sent to the Board of Trade in London, with Frederick Solly-Flood, the Attorney General of Gibraltar concluded that the crew on the Dei Gratia had wanted to steal the alcohol on the Mary Celeste, and murdered Captain Briggs’ and his crew in a drunken frenzy. Flood believed that Captain Morehouse and his men were hiding something, that the daily log of where the Mary Celeste had been had been doctored. Flood did not believe that the ship could have travelled 400 nautical miles while being uncrewed.

It was discovered that what appeared to be “blood stains” were in fact not blood, which setback Flood’s theory of murder. Another blow was when Captain Shufeldt of the US Navy reported the marks on the bow were not man-made, but came from natural actions of the sea.

There was nothing concrete, so Flood had to release the Mary Celeste from the court’s jurisdiction on February 25, 1873. The salvage payment was decided on April 8, 1873, the award was about one-fifth of the total value of ship and cargo, far lower than what was expected.

While Flood’s theories of murder were not very convincing, there was still suspicion that the ship had met foul play of some sort. Some believed that Briggs and Morehouse were involved together, wanting the money, but it doesn’t make sense that they would have planned such an attention drawing event. Others also comment that if Briggs wanted to disappear permanently he wouldn’t of left his young son behind with his mother.

Some believed the Mary Celeste was attacked by Riffian pirates who were active off the coast of Morocco in the 1870′s, however this has been largely dismissed because pirates would have looted the ship, yet the captain’s personal possessions were found; some which had significant value.

A New York insurance appraiser named Arthur N. Putman, was a leading investigator in sea mysteries in the early 20th century. He proposed a lifeboat theory, stating that only one single lifeboat had been missing, the rope had been cut, not untied, which meant that when the Mary Celeste was abandoned, it happened very quickly.

There was multiple times in the ship’s logs where it was mentioned there was ominous rumbling and small explosions from the hold. Putman believed that the alcohol on ship gave off explosive gas and one day there was a more intense explosion of this. A sailor perhaps went below deck with a light or a lit cigar which set off fumes causing an explosion that was violent enough to blow off the top covering on the hatch, explaining why it was found in an unusual position. Putman believes Briggs and the crew were in a panic and piled into one lifeboat, abandoning Mary Celeste.

Deveau, who was one of the men who examined the abandoned ship on sea, proposed that Briggs abandoned the ship after false sounding, there might of been a malfunction of the pumps or another mishap, giving the impression the ship was taking on water at a rapid pace, the crew might have assumed the ship was in danger of sinking.

Mary Celeste made her way to Genoa, and then left on June 26, 1873. She arrived in New York on September 19, 1873. Due to the Gibraltar hearings and newspaper stories she became quite unpopular, nobody wanted her. In February 1874, Mary Celeste was sold at a considerable loss to a partnership of New York businessmen.

Mary Celeste sailed mainly in the West Indian and Indian Ocean routes, but was losing a lot of money. In February 1879, her captain was a man named Edgar Tuthill, who had fallen ill. Tuthill died and some believed the ship was cursed, as he was the third captain who had died prematurely.

In August 1884, a new captain named Gilman C. Parker took on the ship. On January 3, 1885, Mary Celeste approached a large coral reef, the Rochelois Bank, where she purposely ran into it, ripping out the bottom and wrecking her beyond repair. The crew then rowed themselves ashore, and sold what was left of the cargo for $500.

In July 1885, Parker and his shippers were tried in Boston for conspiracy to commit insurance fraud, with Parker also being charged with “wilfully casting away the ship” which was known as barratry, which you could be sentenced to death for.

On August 15, 1885, the jury could not agree on a verdict. Instead of having another trial, which cost a lot of money, the judge negotiated an arrangement where Parker and his crew withdrew their insurance claims and repaid what they got. The barratry charge was deferred and Parker was set free, though his reputation was ruined.

Parker died in poverty three months later, one of the co-defendants went mad and another ended his life. This further caused people to believe Mary Celeste was cursed.

At Spencer’s Island, Mary Celeste and her lost crew are commemorated by a monument, and by a memorial outdoor cinema built in the shape of the vessel’s hull. The fate of the crew of the Mary Celeste have never been discovered, and over 150 years later, it is unlikely we will ever discover the truth.

#mystery#unsolved#UNSOLVED MYSTERIES#unsolved crime#unsolved case#ship#vessel#true crime#Crime#sail#mary#celeste

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Foxe's Book of Martyr

Foxe’s Book of Martyr

https://www.biblestudytools.com/history/foxs-book-of-martyrs/

Edited by William Byron Forbush This is a book that will never die — one of the great English classics. . . . Reprinted here in its most complete form, it brings to life the days when “a noble army, men and boys, the matron and the maid,” “climbed the steep ascent of heaven, ‘mid peril, toil, and pain.” “After the Bible itself, no…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Photo

1943 Sky Giant - Robert Taylor

In the mid-1930s, at a time when Pan American had led the way with two generations of four-engined flying boats, the United States Navy sought a much larger, heavier flying boat for over-water reconnaissance bomber service.Consolidated Aircraft’s PB2Y Coronado was the result, this massive all-metal flying boat first taking to the air in 1937. Several models and extensive modifications followed and in 1943-4 a number were converted for the Naval Air Transport Service for carriage of cargo and passengers and were flown by contracted Pan Am flight crews.Robert’s superb painting shows a PB2Y-3R dressed in wartime olive paint at Pan Am’s Marine Terminal mooring, La Guadia, 1943.Each print in the edition is signed by the artist, and Pan American Captain William W. Moss who, on one notable occasion, landed in heavy seas to rescue 48 survivors from a torpedoed merchantman – lifting off in a 15ft swell to fly the oil-soaked seamen 300 miles to safety.

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Police Apologize For Wrongful Conviction Of Somaliland-Born Man Executed 70 Years Ago

#MahmoodMattan, a #British #Somalilander, was hanged in 1952 after he was found guilty of murder in #Cardiff, but his family has been given a police apology for the terrible suffering the #miscarriage of justice caused, 70yrs after he was executed in a British prison.#Somaliland

(more…)

View On WordPress

#Black Lives Matter#British Somalilander#Cardiff#Injustice#Laura Williams#Lily Volpert#Mahmood Mattan#Race#Seamen#Somaliland#South Wales Police#United Kingdom (UK)#Wales

0 notes

Text

Commissioned Officers

Up to the 1630s it was a captain's responsibility to choose the lieutenants and the crew of the ships, whereas captains themselves were selected by the naval authorities. This left some room for corruption, and captains sometimes did not fill all the vacancies of a ship's crew, even at lieutenant's rank, so that they could pocket the difference in wages themselves. In a bid to stop the fraudulent practice the goverment decided it would appoint lieutenants. Much concern was expressed by the goverment and naval authorities about the quality and professional competence of its comissioned officers during the 17th century anglo dutch wars.

These concers centred around gentlemen officers from wealthy and aristocratic backgrounds who had received comissions and promotions not on the basis of their ability, but through patronage and interest ahead of more deserving and experienced professional seamen- tarpaulin officers who lacked the right social background and connections. A prime example of this was the rapid promotion of Sir William Berkley between 1661 and 1665 from lieutenant to vice admiral. As a result, measures were brought in to ensure that the most suitable candidates wer recruited as commissioned officers. In 1665, the goverment ordered that no man could be rated midshipman unless he could untertake the duties of a commissioned officers. Examinations wer introduced from 1677 to test whether would be lieutenants had the relevant skills, knowledge and experience required to perform the duties expected from the rank.

Candidates taking this examination had to be aged 20 or over (lates reduced to 19) and were required to have served at least 3 years at sea (later extended to six) - one year of which was to be served as a midshipman and produce certificates signed by their captains confirming they were suited to be a lieutenant. Most aspiring commissioned officers wrer sons of peers, baronets or the landed gentry. They could join the Navy in several ways to serve the necessary qualifying time to be able to sit the lieutenancy examitnation.

The traditional method was a captain's servant. This rating was giving to boys who served a type of apprenticeship under the patronage of a captain, who took them to sea more often than not to oblige relatives or friends. This custom of allowing officers their own retinue went back to the Middle Ages. In 1700, captains were allowed four such servants for every 100 men on board their ships. This led to an common abuse of the system in that actually being on board as captain's servant, thereby giving them false sea time to qualify them for the lieutenancy examination once they were older. One such captain was Sir Isaac Coffin, who was court martialled in 1788 for keeping false musters having entered the names of four boys, including two of Lord Dorchester's sons, for this very reason.

Another way of becoming a commissioned officer in the Royal Navy was as a volunteer. A new rating of volunteer by order with the patronage of the King was introduced in 1676, with the aim of recruiting young gentlemen to the Navy who are more sensible of honor that a man of meaner birth. They had to be at least 16 years old and brought up by times at sea and willing to apply themselves to the learning of navigation and fitting themselves for the service at sea. These volunteers, also known as King's Letter Boys because their appointment was by the authority of the King thended to be older than captains servants and were nominated by the Admiralty for service in ships.

The idea was to educate at least 40 students, with places given to officers' sons because the joining costs were too high. They would be trained in the important subjects of Latin, writing, arithemtic, drawing, fortification, mathematics, fencing and the use of small arms. In addition, they would work in a dockyard to learn shipbuilding, rigging and the use of guns. After completing the academy, the young gentlemen's time at sea would be shortened by two years. The programme was not popular with the captains, as it reduced their privilege to appoint their own boys to their ships. Many places were not taken up over the years. And the reputation of the acedemy was very poor, with many of the students misbehaving, getting drunk and whoring around town.

In 1773 the academy became known as the Royal Navy Academy and in 1806 the Royal Navy College. With fundamental changes in the way it repented and treated its students, the reputation recovered and the number of students rose to 70, although the incentive among the captains was never particularly high. And as a result, the college stopped admitting students in 1837.Scholars of note who did attend the school include Philip Broke, captain of HMS Shannon, who is famous for his victory over the USS Chesapeake in 1812; and Jane Austen’s two brothers Francis and Charles, who later became admirals.

The number of ranks and ratings on board each ship was fixed by the Admiralty. This limit on numbers meant that it was sometimes difficult for young gentlemen under Admiralty patronage to secure employment on board a ship given that captains chose a ship’s crew and were more likely to favour their own choice of men. So that volunteers per order (1676-1729) and college volunteers (1729- 1816) were given an opportunity to acquire the necessary qualifying time to take the lieutenancy examination, Pepys introduced during the 1660s the rank of the midshipman ordinary. This rank was treated as a supernumerary, paid only as an able seaman, and took the place of a seaman on board a ship. The rating of captain’s servant was abolished in 1794 and was replaced by volunteer first class, the number of which was officially limited. Boy’s age of entry was set at 13 unless they were sons of officers, in which case they could be 11.

The Admiralty, however, still had no great control over who could be nominated as a volunteer first class; this was still the personal decision of captains. By the early 1830s captains wer selecting fewer candidates as volunteers first class, mainly because after the Treaty of Paris in 1815 fewer officers were required.

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ranks and Roles Aboard Whaleships

Boatsteerer Philip Gomes of the bark Wanderer. Photographed by William H Tripp in 1922. Via New Bedford Whaling Museum.

GOOD MORNING. I never wrote about this cos I was like ‘well that’s common knowledge isn’t it’ but…I exist in my own little bubble so it probably isn’t. Here you go! The ranks, jobs, and average range of what their share of profits would be (the lay).

Whalers were most commonly ships or barks (there were smaller brigs and schooners but not for those Big Long Voyages, so those were seen more often much earlier in the industry). They were relatively small and stumpy, about 100ft long by 25ft wide, with a tonnage ranging 180-400, but had crews ranging from 20-40 people. Read on under readmore!

Captain

Lay: 1/12 - 1/16

Many captains were brought up in the industry, rising through the ranks from a young age. Many also came from whaling families. In addition to managing the voyage, updating the agents, and meting out discipline, the captain would also sometimes join in lowering for whales (as boatheader—see below, under mates). American whaleships were also not required by law to have a doctor on board and very few did (it’s an extreme rarity…I know of like, three). As such, the captain was also the one to manage medical care, ranging from dosing emetics to setting bones. Sometimes he would keep the official logbook himself. He was also permitted to bring his family on board, if he so chose.

Mate

Lay: anywhere from 1/18th - 1/65th depending on if they were 1st, 2nd, 3rd, or 4th mates.

Whaleships had 3-4 mates (3 is more common). In addition to carrying out the captain’s order in managing crews they also had domain over their individual whaleboats when lowering for whales. Each mate served as ‘boatheader’. The boatheader would stand at the stern of the whaleboat, steering it and quietly giving direction to the other 5 men rowing. He was the only one who was facing forward to see the whale. Once the boatsteerer (see below) at the bow harpooned the whale and the boat was fast, the mate and boatsteerer would change places. The boatsteerer would take up the steering oar, and the mate would stand at the bow. This switch happened because it was the mate’s job to actually kill the whale with a long lance, when the opportunity presented itself. Mates also tended to be the ones who cut the blanket pieces of blubber (the first and largest strips of that were later cut smaller aboard), either from the whale, or severing the piece when it was lifted up to the deck. The 1st mate also often tended to keep the ship’s log.

Boatsteerers

Lay: 1/80th - 1/110th

Essentially functioned as the petty officers on the ship. For general ship’s work, they helped oversee the foremast hands and would also coil the whale line tubs for their respective boats. But the core of their job was harpooning the whale. The name of their role is misleading, as for much of the time in the whaleboat they weren’t steering at all. They were positioned at the bow of the boat, helping to row until the opportunity came to harpoon the whale. Then they’d steer (much as one could at that point) upon switching places with the mate. They also could be the ones out on the scaffold when cutting into a whale, separating the blanket piece and discouraging hungry sharks swarming the carcass. Like the other above ranks, boatsteerers were often veteran whalers who worked their way up to that position.

Ordinary

Lay: 1/120th to 1/180th

Foremast hands. They were more experienced seamen than greenhands, who often outnumbered them.

Greenhand

Lay: 1/160th - 1/220th

Inexperienced new crewmen. Whaleships had a disproportionate amount of greenhands aboard than other maritime industries. Because they were small ships with large crews and years to learn on the job, agents were kinda like ‘yeah sure we’ll take anyone lol’. Typically, over half of the men living before the mast were brand new to the work and the sea in general. Line Crossing Ceremonies, for instance, didn’t feature as heavily on whalers as they did on merchant ships cos there were just too many new ones! Too many new ones for Neptune & Co. to haze.

Cook

Lay: 1/120th - 1/180th

He cooks….often the subject of ire among all foremast hands.

Steward

Lay: 1/100th - 1/180th

In charge of the cook and managing provisions. He also maintained the cabins of the captain and mates and waited on officers at meal times.

Carpenter

Lay: 1/120th - 1/180th

In addition to ship repairs, the carpenter also fixed whaleboats that were stove, so depending on the season and the luck, he could be kept very busy. His workbench was located behind the tryworks. In the case of carpenter and blacksmith, sometimes ordinary sailors doubled up on these jobs and served in this capacity as well, but they were more often a separate occupation.

Blacksmith

Lay: 1/20th - 1/180th

In addition to making metal fittings for ship repairs and maintaining the tryworks, he’d craft hoops for barrels, and make and repair whalecraft. He was responsible for straightening out all the twisted irons that were taken from a whale to be used again.

Cooper

Lay: 1/30th - 1/65th

Considered a particularly essential hand aboard, hence the pay. The cooper made all the barrels. And if all went well a whaleship would need a lot of barrels.

Cabin boy

Lay: 1/220th - 1/350th

Not always present on whaleships, but sometimes they were there. They mostly just assisted the steward. Many of them were young sons from whaling families, sometimes the sons or little brothers of mates or captains aboard that ship, going to sea with the intention to become career whalemen.

—

And just a little bit about the microcosm of rank within a whaleboat as well. There were six men in each.

Boatheader : Mate or Captain, who directs the crew, originally steers the boat, and kills the whale.

Boatsteerer: Petty officer who harpoons the whale, and steers after getting fast.

Bow Oarsman: Usually the most experienced foremast hand, as he managed the line once a whale was fast and led the crew in holding or hauling it when needed.

Midship Oarsman: His oar was often the longest and heaviest to wield, so he had to have a good deal of strength to manage it.

Tub Oarsman: Managed the whale line tubs, mostly making sure they weren’t fouling and dumping water on them to keep them from burning when they were being pulled by a whale.

After Oarsman: Usually the least experienced member. He’d coil the line that was hauled back into the boat.

137 notes

·

View notes