#and one of those european “orientalists” common at the time

Text

all im saying is if crowley had been friends with freddie mercury, it only follows that aziraphale was friends with Tchaikovsky.

I'm talking them sipping tea in russia. Indulging in pastries in comfortable silence, writing in their respective diaries. One day Tchaikovsky sticks his head out of his sheet music and gasps "what if we put CANNONS in the OVERTURE" smiling ear to ear and Aziraphale gives this wicked, enabling grin. Aziraphale's favorite piece would be Dumka because it has so much beautiful imagery and because it is really Tchaikovsky trying to put his home to music. Imagine Aziraphale meeting Tchaikovsky's lovers and warning them not to hurt him with a very angelic grin. Imagine Aziraphale sending Tchaikovsky his favorite foods during the latter's depressive episodes. Imagine Aziraphale's fury when after Tchaikovsky's death, his diaries are censored by the soviet union and the later russian government, entire passages blocked out because they discussed his lovers and sexuality. Imagine him trying to preserve the books his friend once loved because if he doesn't, even more of his memory would be erased.

#gay mfs#oops my hand slipped and it got angsty#pls fanfic writers make it happen#im evoking the muses rn#tchaikovsky wasnt all good ofc#he was very much a wealthy aristocrat#and one of those european “orientalists” common at the time#but still i think theyd be friends#good omens#aziraphale#good omens headcanons

74 notes

·

View notes

Note

While I feel that hws France is hard to portray I do wonder what headcanons you have for him. Care to tell a few that come to mind?

a lot of my headcanons of francis/françois are from the british imperial + sea/east asian perspective, so with that in mind, these are some thoughts i've had:

a. françois' strengths are that he can be very charming and good at putting people at ease. he is somebody, if you ran into him somewhere, just comes off as a really interesting person. he can talk for ages about his passion for philosophy, art, literature, science and cooking without it getting boring to the listener.

b. he can be a really good lover too and is that sort of person who considers it a point of pride to make his partners enjoy his company. the sort of person who will make dinner and probably also a good breakfast for you. but one of his flaws is that he can also be pretty self-centred at times, and sometimes he uses his charisma to get out of things or simply dodge issues in his personal relationships.

c. françois, much like arthur, is in the Bad Parent club vis a vis matthew in the 17—18th centuries. where they differ however, is i feel that arthur was controlling but more...present, whereas françois was more...dismissive. matthew would get letters from arthur instructing him to do this and that, which for matthew at least acknowledged him, whereas françois might just not even write to him much at all, especially after matthew came under arthur's control.

d. françois really clicked with alfred during the revolutionary war. it helped that alfred was punching arthur in the dick, but i think that françois for all his flaws, genuinely possesses a somewhat more idealistic streak (than say, arthur imo) so that gelled well with alfred spouting all kinds of enlightenment thoughts (especially since he was also reading french writers like Montesquieu).

e. françois and lien (vietnam) have a complicated (to say the least) relationship due to the history of french imperialism over vietnam; i see francis being much younger than her (she and yao are peers in age!), so lien fitted him very much into her prior experience as an older female nation being forced to deal with 'boys playing at being empires'. lien probably shot him in the face at least once during the first indochina war, that tried to re-establish colonial rule over vietnam in the 1950s. however, i do think they can talk more cordially in more recent decades, with normalisation of ties. cooking is perhaps one topic that is a common interest—vietnamese banh mi is a kind of sandwich originating from french baguettes that incorporates local ingredients, and it's a really tasty and popular streetfood. there's also a big french-vietnamese population in paris today.

f. kiku was absolutely not impressed by monet's la japonaise, nor 'madame chrysanthème', the wildly racist and orientalist mess that Madame Butterfly was based on. it was exoticising, not flattering to him—he was however, more amenable to those of françois' artists that incorporated japanese artistic techniques in more genuine ways, or with françois' own view of aesthetics and his knowledge and interest in engineering.

g. yao, much like kiku later, was someone françois was very interested in culturally—as seen from the boom in chinoiserie when trade with china began back in the 17th century. i think french is probably one of the first european languages yao learns (besides portuguese). it's a fairly functional trading relationship—until of course, french imperialist interests began expanding in yao's sphere of influence and the opium wars.

h. i'm a fruk fan so naturally i think his love-hate relationship with arthur is one of his most significant r/ships—arthur has been a neighbour, friend, enemy, lover and everything in between. but! scotfra is another very, very long-term relationship important to him (auld alliance!). also on an EU level well, there's him and ludwig too.

i. naturally, he's also fairly fashionable, and i feel like he'll always eye himself critically even if he's going out casually, compared to way i can see arthur being fairly chill about strolling out in that questionable, ill-fitting acid green christmas sweater alfred sent him as a joke once. i also think françois probably smokes a fair bit, compared to how arthur's gotten a kick in the arse to cut back after WWII. and nowadays, he'll often just be relaxing with a cigarette on the balcony of his apartment with a book, or enjoying a day out in one of his museums.

#hws france#hetalia#hws england#hws canada#hws vietnam#hws china#hws japan#hws scotland#hetalia headcanons

121 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do have any thoughts on genies (either the general group or one of the specific kinds)? I don’t know about other editions, but they seem really flat in 5th edition. It would also be nice if a lot of their depictions didn’t use stereotypes associated with the Middle East.

Monsters Reimagined: Djinn

So I'm going to attempt to restrain myself because the popular representation of genies is one of my favorite things to ramble about pedantically, because the versions of them that we get in d&d are so far removed from their mythological roots that to get into why they're done dirty in most fiction we're going to need to get into dissect a game of broken telephone that's been going on for hundreds of years.

Likewise, getting back to those roots requires us to delve into some very heavy topics like orientalism and cultural mores surrounding slavery, which are complex enough that I could easily make whole posts about any of them.

TLDR: Djinn work well enough as powerful elemental spirits, but the classifications the monster manual uses for them are completely arbitrary and actually mush several different types of creature into one category. Just use Djinn as an umbrella, and don't worry about the pokemon elemental alignments. Perhaps most jarringly: Genie wishes do not rewrite reality or do the impossible, and are instead tasks that the djinn is magically compelled to do. This means you can include Djinn in a lot more of your stories without having to worry about including magical cheatcodes into your game. Instead, you get to wrestle with the complication of people keeping powerful (and potentially destructive) magical creatures as slaves, which has much more storytelling potential to play with.

What's wrong: While normally I'd do a breakdown on problematic portrayals of djinn ( and hooboy are there many) I think to get us all on the same page, I'm going to peel back the layers of historical/pop culture representation so we can see how these creatures have changed over time.

Djinn originated in pre-Islamic Arabia and occupy a similar cultural role to "the fey" in Europe, unseen beings that are as numerous as as the stories and cultures that involve them, tricksters, tempters, helpers, monsters, all manner of things.

The 7th century rolls around and there's a hot new religion that's looking to put down roots. Djinn get codified in the Quran as one of the three sapient beings created by Allah ( Angels of Light, Humans of Clay, Djinn of smokeless fire) which defines their theological existence going forward. The idea of powerful/magical people keeping Djinn as servants gets popularized ( which I've heard was part of a loophole regarding the Abrahamic forbiddance on sorcery. A pious individual couldn't possess magical powers, but they could own a being/object who did)

Over the next thousand years Orientalist texts like the 1001 Nights expose European audiences to the concept of "genies" , leading to the common idea of them and the wishes they grant entering the cultural lexicon.

At some point in the 1970s, the folk who make d&d are plundering every mythology they can lay hands on for fantasy creatures to include in their game, and decide on including the djinn. To make this creature fit into their budding cosmology, they're made into air elementals, which paves the way for other elemental genies to follow, with the name of more Arabic spirits being haphazardly stapled on to fill out the roster.

In 1992 Disney happens, and the genie/ bound object/three wishes trope is codified into the cultural consciousness forever.

Putting aside the ham-fisted cramming of djinn into the role of elemental nobles, I think the most interesting thing to address when talking about Djinn is the issue of wishes. Simply put, rather than a being of “phenomenal cosmic power” that can snap its fingers and make the impossible happen, Djinn in the original stories were magical servants/slaves, bound into service and forced to do tasks that while impossible to a human were menial for it. The idea of a flying carpet? not an inherently magical object, but a piece of textile held aloft by four djinn who carried the thing and their “master” upon it like a palanquin. Aladdin asks the djinn of the ring to make him a palace? The djinn doesn’t just conjure one out of thin air, but assembles it by hand impossibly fast. If you bring bound djinn into your game, you’re going to have to start considering your world’s stance on slavery, which can be a heavy topic in its own right.

What’s worth Saving: The ethical quandary of a captive djinn can actually be a thematically rich avenue of storytelling potential provided your campaign is emotionally mature enough to acknowledge that enslaving sapient beings is abhorrent.

Is it right to keep a djinn captive for personal gain? No? What if its powers are turned to a good end?

What if the players get their hands on the djinn, get what they need, and free it right after? Is it still moral to exploit something and then let it go?

What if the djinn was a dangerous and wild thing, a murderous spirit, or the manifestation of a powerful storm or wildfire and if released would go back to causing chaos, is it still right to keep and exploit it then?

What if the djinn was not originally hostile, but has been deeply abused over its captivity, and has sworn revenge against those that wronged them? As a being of tremendous power its vendettas could prove to be calamitous

These sort of questions can have a party debating for ages, and can provide the thematic through line for a lot of great adventures, especially when coupled with wonderous possibilities of the djinn’s powers and their elemental nature for added aesthetic flourish.

How do we Fix it: 5e’s already taken a step in the right direction by removing the ability of most “genie” creatures to grant wishes, saving it for more advanced versions of the creature. Personally I’d eliminate the ability entirely, and have it be a misconception among common people and dabbling arcanists that djinn can do anything when captured. Djinn then stay the FUCK away from most mortals, preferring to dwell in the most inhospitable places and letting nature keep away those who would hunt and enslave them.

As I mentioned before, I'd also do away with a strict air/water/earth/fire alignment to geniekind, and instead have them manifest as particularly wild aspects of nature.

Adventure Hooks:

While trekking through the deep wilderness, the party stumbles into a wonderous castle boasting all manner of enchantments, with a strong elemental theme. Possibly seeking shelter or supplies, they enter the domicile only to discover that it’s the domain of a djinn, who fears that they’re here to capture it and bind it. Perhaps some swift talking can put their host at ease, or perhaps they’ll give into the temptation of making the castle theirs.

A djinn of falling stars was long ago bound to a lantern by a powerful arcanist, who had him tell her all the secrets of the heavens. Generations later, the Arcanist is dead, but the djinn remains trapped, and now searches for a mage clever enough to break the seal upon the lantern. Greatly disappointed by their prospects, the djinn has become a tutor of the arcane arts, hoping to raise up a student with enough talent to one day free them.

The spring that fed an oasis settlement has suddenly gone dry, throwing those who relied on it into chaos and despair. Investigation reveals that a shy and kindly djinn was maintaining the font, but was nearly killed after a band of treasure hunters learned of her existence and sought to capture her. With the elemental fading in their arms and the oasis on the verge of drying up, the party will need to decide between defending against further attacks, or venturing out into the desert to find a means of healing her.

#Djinn#random encounter#ally#mentor#desert#rescue mission#D&D#D&D adventure#Homebrew Adventure#Adventure#DnD#monsters reimagined

335 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Pacha of Many Tales

I’m finally finished with The Pacha of Many Tales, and it was… something, I suppose. It certainly dethrones The Pirate as my least favorite Marryat novel to date. I think The Pirate suffered in my estimation since it was only the second Marryat book I had read, and right after Mr. Midshipman Easy at that. After such a clever and humorous story it felt boring and bombastic, and one of these days I ought to give it another chance.

Reading The Pacha of Many Tales just once was more than enough, I’m sure of it. It is sometimes described as a “parody” of Arabian Nights, but it only borrows a similar framing device of a bored and fickle ruler (the Pacha) who demands entertainment with stories from his subjects. The Pacha and his vizier will eavesdrop on the common folk, and when they overhear an exceptionally colorful or inscrutable remark they insist on the story behind it. Certain characters return for multiple tales and others make a single appearance.

It is a great deal of orientalist nonsense, needless to say, although Marryat seems to be drawing from sincere translations for a lot of the material. There are at least two academic papers referencing Pacha that I came across in the course of looking up things from the book, and it is possibly of interest to people looking for Western, specifically British depictions of “exotic” cultures in the Middle East and the Mediterranean region. Marryat’s writing in general is heavy on broad stereotypes, often offensive stereotypes, but at least it has the redeeming qualities of being original and authentic in its Age of Sail content, and entertaining. Not so with the 500 pages of dreck I just plowed through.

Another note on the offensive stereotypes: it’s true that Islamic customs and religious officiants appear backward, primitive, and superstitious in Pacha; but Marryat’s treatment of European Catholics is just as patronizing. They are shown as equally regressive and corrupt, and this practically gets lampshaded by an English sailor who observes to the pacha and his vizier, “Jack Soames said that you warn’t Christians, but that if you were, you could only be Catholics.”

Marryat refrains from editorializing or interrupting his story, which was originally serialized in his Metropolitan Magazine between 1831 and 1835. There’s only one brief moment in the opening pages when Marryat speaks in his own voice, seeming to refer to his guilt and trauma stemming from his long military career. It’s a sad, disquieting passage, following a meditation on the “bloody hand” of heraldic symbolism:

And I, whose memory stepping from one legal murder to another, can walk dry-footed over the broad space of five-and-twenty years of time, —but the “damned spots” won’t come out— so I’ll put my hands in my pockets and walk on.

Conscience, fortunately or unfortunately, I can hardly tell which, permits us to form political and religious creeds, most suited to disguise or palliate our sins.

(Just in case you forgot Frederick Marryat had PTSD, owch.)

The best tales are those of Huckaback, a renegade French sailor of shifting national and religious allegiances. Marryat is in his element with the sea-stories, and we get a more concrete idea of the time period from Huckaback’s references to historical events such as la Terreur of 1793. (The other characters almost exist outside of history.) At one point Huckaback purchases a whaling ship and heads for Baffin’s Bay, and I was very curious to see an 1830s pop culture representation of an arctic voyage. It ends up with the ship beset and trapped in ice, the crew succumbs to scurvy and eventually resorts to cannibalism. (Prescient!)

Despite this negative experience, Huckaback returns for a second adventure in the arctic. This one is more mystical and fantastical, with Huckaback trapped inside an iceberg in a state of suspended animation before he’s rescued by the inhabitants of a floating island. Amidst this weirdness the real-life Captain William Parry makes a cameo, presumably with HMS Hecla and Griper in 1819-1820. As Parry’s men cut through the ice to free their ships the saws narrowly miss Huckaback in his icy prison.

I am beyond mystified that Pacha gets a higher average review on Goodreads (4.08 stars) than the superior Frank Mildmay (3.7 stars) or The King’s Own (3.45 stars). Both of those books have their flaws, but when they’re good they’re really, really good. Pacha might have a more consistent structure and theme, but it never rises to the level of truly great storytelling. It’s creaky and racist by modern standards, and you can skip it without missing much.

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#the pacha of many tales#the pirate wasn't funny and had just too much purple prose#i know why ppl are mad at the king's own but it is very underappreciated#who is giving 4 stars to this crap turn on your location i just want to talk#book review

1 note

·

View note

Text

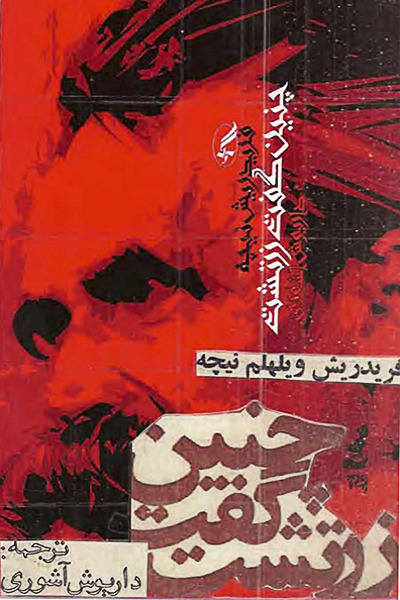

Nietzsche’s “Thus Spake Zarathustra” (part II/II)

❍❍❍

Iran between Zoroaster (زرتشت) and Islam

Last Thursday night (June 20th), Trump approved an attack on Iran after a US drone was shot down, yet he suddenly changed his mind and pulled back from the attack. (5) While Trump almost attacked Iran and started a new area of war and misery in the world, Iranians inside Iran and around the world are frightened by this escalation. Today, Iran’s Jewish community is the largest in the Mideast outside Israel – and feels safe and respected. (6)

Iranians in the diaspora have a variety of ethnicities, languages, religions, and political views but with different intensities, they all share the common Iranian-something else identity. There are many different political oppositions to the current Islamic Republic which in itself is one of the most straight-forward opponents of the United States hegemony and its imperial projects. Politically, Iranian Left has a wide spectrum; from the ultra-radical MEK which is supported by no one else but John Bolton, to Tudeh Party of Iran. Iranian right-wing opposition has also a wide gamut from ultra-right nationalists such as Persian Renaissance, Jason Reza Jorjani who hangs out with American white-supremacists Richard Spencer, to the good old monarchists, and of course the recent infamous Mohamad Tawhidi a fake Muslim cleric educated in Iran who is now a hero for the white-nationalists and Islamophobes. (7) (8)

Iranian nationalists see themselves as Caucasian or white. This might be in part due to the fact that etymologically the word Iran means “land of Aryans”. The Avestan name Airiianəm vaējō "Aryan expanse", is a reference in the Zoroastrian Avesta (Vendidad, Fargard 1) to the Aryans’ mother country and one of Ahura Mazda's "sixteen perfect lands". (9) Before the Islamic Revolution of 1978, Shah of Iran was seeing himself as a descendant of the great ancient Persian kings. In 1971, Shah decided to organize a huge event on the 2500-Year Celebration of Persian Empire (officially known as the 2500th year of Foundation of Imperial State of Iran). Many historians argue that this event resulted in the Iranian Revolution and eventual replacement of the Persian monarchy with the Islamic Republic. If you fancy watching some part of the event, there is good propaganda video narrated by Orsen Welles.

Before the Shah, for a short period, Iran had a cozy democracy in 1951-1952. Iran democratically elected its 25th prime minister Mohammad Mosaddegh (محمد مصدق), who was a supporter of secular democracy and resistance to foreign domination. He nationalized the Iranian oil for the first time in 1951. The oil industry had been built by the British on Persian lands since 1913 through the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC/AIOC -later British Petroleum and BP). Mosaddegh’s government was overthrown in a coup d'état (28 Mordad 1332) orchestrated by the United States' CIA and the United Kingdom's MI6. (10)

Nietzsche and Postmodernism

Zoroaster [Zarathustra as its older form] was the ancient Persian prophet who lived in Iran at some point between 1500 BCE - 1000 BCE. Nietzsche chose the older version of Zoroaster’s name “Zarathustra”. Before publishing the book, Nietzsche included the first paragraph of Zarathustra’s prologue in his previous book Joyous Science (1882). There are two differences between this paragraph and the opening in Thus Spoke Zarathustra. (1) The title Incipit Tragoedia [tragedy begins] and (2) in Joyous Science the lake of Zarathustra’s home is mentioned as “lake Urmi” [today’s lake Urmia] compare to the prologue in Thus Spoke Zarathustra where the name of the lake is left out. We know that the real birthplace of Zoroaster is uncertain. (11)

Nietzsche’s anti-Christian and anti-majoritarian views (it's reversals of Christian morality and values) are picked up by white feminists and queer theorists for obvious reasons. As Michael Hardt wrote in the forward for Deleuze’s "Nietzsche and Philosophy”, postmodernists didn’t just use these concepts to get away from the dominant French Philosophical establishment of ’50s and ’60s but they were also genuinely interested in Nietzsche’s anti-universalities views.

Although very similar in methodology, there are some differences between the Nietzschean concept of solitude (which is very predominant in this work) and postcolonial marginalization and anxiety. Words such as "happiness” and “joy” has a distinctive meaning for Nietzsche which wasn’t unpacked in this book but was the main topic of his previous book Joyous Science (1882). Nietzschean Dionysius is more tonal in this book rather than descriptive and maybe has giving its chair to the bigger umbrella of Eternal Return as the "fundamental conception" of Thus Spoke Zarathustra. (-Ecce Homo, 1888)

Importance of writing as an activist

“Of all that is written I love only that which is written with blood. Write with blood: and you will discover that blood is spirit. It is not easy to understand the blood of another: I hate the reading idler. He who knows the reader does nothing further for the reader. Another century of readers – and spirit itself will stink. That everyone is allowed to learn to read will in the long run ruin not only writing but thinking, too. Once spirit was God, then it became man, and now it is even becoming mob[populace].”

At the end of chapter 4 in Joyous Science, Nietzsche inserted the opening of the Zarathustra’s prologue. He is making his readers ready for a transformation. For understanding Thus Spoke Zarathustra, it is essential for the reader to read Joyous Science first. Nietzsche wants to prepare his readers for his philosophy, so in a way, he is selective about who is he talking to.

“We not only want to be understood when we write, but also just as surely not to be understood. It is by no means an objection to a book that someone finds it unintelligible: perhaps this was precisely the author’s intention – perhaps he did not want to be understood by ‘just anyone’. Every individual with a distinguished intellect and sense of taste, when he wishes to communicate himself, always selects his listeners; by selecting them, he simultaneously excludes ‘the others’. All the subtler laws of style have their origin here; they simultaneously ward off, create distance and forbid ‘entrance’ (or intelligibility, as I have said) – while allowing the words to be heard by those whose sense of hearing resembles the author’s. And between ourselves, may I say that, in my own case, I do not want my ignorance or the vivacity of my temperament to prevent me from being understandable to you, my friends; certainly not the vivacity, however much it may compel me to come to grips with a thing quickly, in order to come to grips with it at all. (The Joyous Science - Book V, 381 On the Question of Intelligibility”)

Anti-Nietzsche writers

Anti-Nietzsche writers usually refer only to Nietzsche’s text from his early period (before the break with Wenger) without taking his later works into consideration. Taking his works out of context is a sign of dismissal of his philosophy and art. Nietzsche met Wagner at the home of Hermann Brockhaus an Orientalist who was married to Wagner’s sister, Ottilie. Brockhaus was himself a specialist in Sanskrit and Persian whose publications included an edition of the Vendidad Sade—a text of the Zoroastrian religion. (12) It was only after the publication of “Richard Wagner in Bayreuth” that he realized who Wagner really was (an anti-Semitic coward). After completion of “Human, All-Too-Human” (1878) and continuation of his friendship with Jewish philosopher Paul Rée, Nietzsche ends his friendship with Wagner, who comes under attack in a thinly-disguised characterization of “the artist”. (12)

“Nietzsche had long hymned the sublime power that Wagner’s music exercised over his senses but now he realised how it robbed him of his free will. The realisation filled him with a growing resentment against the delirious, befogging metaphysical seduction that once had seemed like the highest redemption of life. Now he saw Wagner as a terrible danger, and his own devotion to him as reeking of a nihilist flight from the world. He criticised Wagner for being a romantic histrionic, a spurious tyrant, a sensual manipulator. Wagner’s music had shattered his nerves and ruined his health; Wagner was surely not a composer, but a disease?”

(Sue Prideaux, “I Am Dynamite!: A Life of Nietzsche”)

To even start talking about Heidegger and Nietzschean metaphysics, is to miss-read Nietzsche, just as taking "Will To Power” as something that Nietzsche actually published is wrong. Will to Power was never meant to be a book, it was put together by Nietzsche’s Nazi sister Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche and Heinrich Köselitz. They have selected, added and subtracted parts to Nietzsche’s notes in order to compile a book that is accessible to their average readers. (See Will to Power introduction by R. Kevin Hill, Penguin Classics 2017). Sue Prideaux described this perfectly in Nietzsche’s biography "I Am Dynamite!: A Life of Friedrich Nietzsche”. And Carol Diethe’s wrote a biography on Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche which gives us more insight into her proto-Fascist mentality.

The Will to Power book, did everything that Nazis wanted, hugely swerving from Nietzsche’s philosophy, the book starts with "European nihilism" and ends with the forceful sentence “This world is the will to power – and nothing besides! And even you yourselves are this will to power – and nothing besides!”. No other philosophy could do better justice to the Nazi cause than this fabricated assemblage.

Majority of Nietzsche’s work can be hijacked by ultra-right and the new alt-right, expect his fundamental critic of Christianity which is at the heart of his philosophy. Fascist and racist white writers such as Jordan Peterson, Oscar Levy (who wrote the introduction to Untimely mediation in 1909 and according to Walter Kaufmann, forged a fake autobiography of Nietzsche titled “My Sister and I”), Richard Spencer and others have tried to utilize Nietzsche in their hatred of brown and black peoples, religious minorities, Muslims and Jews, Queer people, and liberals. (13)

Methodologically, Nietzsche doesn’t throw away, archaic classical concepts such as; nobility, civilization, and barbarism, he appropriates and instrumentalizes them for his philosophical end. He didn’t have everything perfect, after all, we are talking about a dude who lived his mature period 140 years ago and was using a “writing ball” to type. (14) He has comical and outdated stuff as well. His rejection of vegetarianism is one of them.

Who is living in Nietzsche’s world

It seems to me the worst thing that we can do when reading Nietzsche is to put his philosophy into a functionalist and majoritarian (national) use. He argues in Joyous Science concerning consciousness (which he perceives as a communal category rather than an individual one):

“the growth of consciousness is dangerous, and whoever lives among the most conscious Europeans even knows that it is a disease. As one might have guessed, it is not the antithesis of subject and object which concerns me here; I leave that distinction to the epistemologists who have remained entangled in the snares of grammar (the metaphysics of the people). Even less is it the antithesis of the ‘thing in itself’ and the phenomenon; for we do not ‘know’ enough to be entitled to make such a distinction. We have absolutely no organ for knowledge, for ‘truth’; we ‘know’ (or believe, or imagine) exactly as much as may be useful to us, exactly as much as promotes the interests of the human herd or species; and even what is called ‘useful’ here is ultimately only what we believe to be useful, what we imagine to be useful, but perhaps is precisely the most fatal stupidity which will some day lead to our destruction.”

Nietzsche’s critique of European Universalism and Western Humanism is still valid and timely, yet if we stay within the hegemonic “white domain“ (White-main) our theoretical understanding of Nietzsche, will be centered somewhere between the Alt-right racism, white phenomenology, European Modernist and localists, Silicon Valley accelerationism and Nick Land (which is equally racist). The only way to get out of this binary is to step out of White-main and find Nietzsche in between the lines of the second-generation non-European Nietzsche intellectuals (Fanon, Derrida, Aimé Césaire, Muhammad Iqbal, Ali Shariati) and the third-generation intellectuals (Spivak, Bhabha). At this time in history, Europeans can’t (and shouldn’t) any longer teach or perpetuate Nietzsche’s philosophy for any end. Not for Germany, not for any other white-majority nation. This is simply because they are already living in Nietzsche’s post-God reality.

Bib.

1. NIETZSCHE, FRIEDRICH and HOLLINGDALE, R. J. . Ecce Homo. s.l. : PENGUIN BOOKS, 2004. 9780141921730.

2. Sandis, Constantine. Nietzsche’s Dance With Zarathustra . philosophy now. [Online] 2012. https://philosophynow.org/issues/93/Nietzsches_Dance_With_Zarathustra.

3. Ashouri, Daryoush. Nietzsche and Persia. http://www.iranicaonline.org. [Online] July 20, 2003. http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/nietzsche-and-persia.

4. Nietzsche, Friedrich. the joyous science . s.l. : Penguin Classics, 2018.

5. Michael D. Shear, Eric Schmitt, Michael Crowley and Maggie Haberman. Strikes on Iran Approved by Trump, Then Abruptly Pulled Back. nytimes.com. [Online] June 20, 2019 . https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/20/world/middleeast/iran-us-drone.html.

6. Hjelmgaard, Kim. Iran’s Jewish community is the largest in the Mideast outside Israel – and feels safe and respected. msn. [Online] 8 29, 2018. https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/world/iran%E2%80%99s-jewish-community-is-the-largest-in-the-mideast-outside-israel-%E2%80%93-and-feels-safe-and-respected/ss-BBMAVgX.

7. Mackey, Robert. How a Fringe Muslim Cleric From Australia Became a Hero to America’s Far Right. theintercept.com. [Online] June 25, 2019. https://theintercept.com/2019/06/25/mohamad-tawhidi-far-right/?fbclid=IwAR25hr0TV8w0erffRrGhccVkC5G0KFwjR3y7tM7n2j-4nx4pp_b5PssuFzo.

8. Schaeffer, Carol. ALT FIGHT Jason Jorjani Fancied Himself an Intellectual Leader of a White Supremacist Movement — Then It Came Crashing Down. theintercept.com. [Online] March 18 , 2018. https://theintercept.com/2018/03/18/alt-right-jason-jorjani/.

9. ĒRĀN-WĒZ . Encyclopedia Iranica. [Online] http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/eran-wez.

10. Kinzer, Stephen. All the Shah's Men: An American Coup and the Roots of Middle East Terror . s.l. : John Wiley & Sons, 2004.

11. Nietzsche, Friedrich. Joyous Science. s.l. : Penguin Calssics, 2018.

12. Wicks, Robert. Nietzsche’s Life and Works. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. [Online] 2018. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/nietzsche-life-works/.

13. Illing, Sean. The alt-right is drunk on bad readings of Nietzsche. The Nazis were too. www.vox.com. [Online] Dec 30, 2018. https://www.vox.com/2017/8/17/16140846/alt-right-nietzsche-richard-spencer-nazism.

14. Herbst, Felix. Nietzsche’s Writing Ball (Video). felixherbst.de. [Online] https://vimeo.com/43124993.

(Part II/II)

______________________

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lupine Publishers | The Concept of Science in Islamic Civilization the Case Psychology and Behavior Sciences

Lupine Publishers | Scholarly Journal Of Psychology And Behavioral Sciences

Abstract

Islamic civilization formed in context of behavioral changing and explaining human behavior in many medieval teachings led to emergence of behavioral science and psychology. Present study proved scientific approach of Islamic civilization to human behavioral research that it has illustrated concept of science in Islamic civilization. The capital of this change in behavior of nations is emergence of human phenomena called Prophet’s everyday life. Writing daily life has been common issue of world civilizations since ancient times. This religious phenomenon of Prophetic usage effected on attitude, hygiene which explained in various schools of religious psychology and social psychology, including Gestalt school. The writing of life style of Prophet led to establishment science in Islamic civilization entitled Knowledge of everyday life of Prophet because general phenomenon of character of Mohammad’s daily life is like a symphony that has organized behavior of Islamic societies for centuries. The subject of this science is perfect human behavior, which is intuitively understandable to human societies.

And it can be considered starting point of knowledge of Islamic behaviorism in Middle Ages. Because this generality exists alongside any partial behavior of Prophet. Within framework of Aristotle’s book on the soul Philosophers produced theoretical foundations of Islamic psychology and behaviorism. Alpharabius, Avicenna on soul and its belonging to body and neuroscience of these communications and his research on human sensory perceptions and physical connection of soul and essential place of prophecy in its completion. Islamic behavioral sciences refer to initiatives of Islamic societies.

Keywords: Psychology; Avicenna; Alpharabius; Lifestyle; Soul; Prophetic usage

Historical and Theoretical Introduction

The concept of science in civilization from Greek civilization to Islamic civilization Inductive study of the teachings is Aristotle’s initiative in the history of science. The way of thinking in Islamic civilization has been formed with a tendency towards Aristotle. The concept of science in Islamic civilization is the same as the concept of science in Greek civilization. It is on this basis that Aristotle was called the first human teacher in the history of science in ancient times due to his special tendency in the inductive division of sciences and knowledge. And Aristotelian philosophy has remained an active force in the method and concept of science to this day. Alpharabius was named the second teacher of science for sharing Aristotle’s method. His classification of sciences is based on Aristotle’s Book of Soul, which is first classic book on human behavior and it is theoretical basis of behavioral science in history of science.

Psychology and behavioral sciences in Islamic civilization

Behavioral Sciences, which deals with the nature of human individual and social behavior, began with Aristotle’s book of soul and Plato’s teachings about the soul and individual and social behavior of the citizen in the city. The classical form of defining the science of behavior and its place in the history of science is the product of Islamic civilization and was presented by Farabi’s second teacher [1-5]. By combining Aristotle’s and Plato’s views on the soul, he has divided science into five categories. and fifth branch is science of behavior, which Farabi referred to as civil science. Explaining this branch of science, Farabi has spoken about the word soul, behavior, personality, society, the nature of behavior, and the end and purpose of behavior. In beginning of Islamic civilization, Razes and Avicenna wrote book in phycology with title spiritual medicine and Psychosomatics.

Following perfect man in Islam and Christianity in medieval

The most Common denominator of Islam and Christianity in medieval is the need to follow perfect man to achieve happiness. At the beginning of the Middle Ages, St. Augustine wrote a book on the city of God in the context of Plato’s philosophy of soul, criticizing the individual and social behavior of Roman societies towards the behavior of the perfect man. In middle of medieval, Farabi examined perfect and imperfect behavior of man and society. And in late Middle Ages, Averroes criticized the individual and civil behavior of man in the context of Aristotle’s philosophy. He explained science of Islamic behavior on the basis of Aristotelian rationalism. At the same time, Emperor of Germany Frederick II called on Christian, Islamic, and Jewish scholars in the Mediterranean to test the nature of the human soul on the basis of Ibn Sina’s knowledge of the soul, and to ask scientists about the nature of the human soul. What is the reason for this emperor’s scientific actions, which was his apparent behavior in clothing and food and many other customs in accordance with the culture and behavior of Muslims and had several Islamic teachers and counselors, about soul -knowledge?

Anthropology, ethnology in Islamic civilization, behavior people of capitals

One of the most important branches of behavioral science is anthropology, which has been left and produced in classical texts of the Middle Ages. An anthropological leader in the Middle Ages, he traveled to India to learn about behavior and anthropology. According to historians, science is a pioneer in behaviorism of Indian people (Sarton, In medieval literature and history there are texts that are the written legacy of Islamic civilization on the behaviors of individuals and nations. At the forefront is the travelogue of Shiite scholar [6]. He traveled to India in the tenth century to report on the behavior of the India people, An external book on the behavior of the Indian people in 1910 was translated into English by Zakhao with title: Albiruni’s India and Al-Biruni’s encyclopedic work on India [7-10]. Several Islamic travelogues have described the behavior of European peoples and societies in the Middle Ages .as Reporting and Ibn Khaldun, whom European orientalists have called him Montesquieu the Arab. he is the founder of the science of historical sociology. he has examined the socialpolitical behavior of heads of state and communities. His study is a kind of social psychology and is based on understanding human emotions .he has considered the kind of human feeling that can be studied simultaneously in the sciences of behavior, political science, ethics, and history as the driving force behind individual behaviors and community behaviors. he has written articles on sciences of soul and Islamic psychology, his theories on social dilemma and human behavioral education have been compared to those of contemporary psychologists, He has explored human thought and learned from the empirical reason for acquiring knowledge. his views of man are similar to Martin E. P. “Marty” Seligman in Positive Psychology.

Historical value and content accuracy of teachings known as Islamic medicine

Titles as Islamic medicine, health, psychology, means set of teachings that Islamic societies have prepared and attributed to some of the great men of Islam. Including Imam Sadegh’s medicine, Imam Reza’s medicine, the Prophet’s medicine, this attribution may be correct and may be rejected by experts in Islamic history and civilization, This issue is very similar in Islamic civilization and has been disputed for several centuries, and in the history of science and civilization of Christian and Jewish communities, the situation is similar. Is it possible to say that Islamic mathematics and medicine and psychology is opposite to Christian, Jewish and Jewish mathematics? Or that there is only mathematics in Islamic, Christian, Jewish, and Iranian societies.

In the present article, Islamic Health and Islamic Psychology refers to the collection of traditions and teachings and psychology courses that Islamic societies and Muslim people have researched, and the collection of innovative and physical services of Islamic societies to the history of health and behaviors sciences and psychology . And using title of Islamic behavior science and Islamic Psychology is a virtual application. As Ibn Khaldun, an expert on Islamic civilization in ninth century of AH and fourteenth century of AD, has denied existence of Islamic medicine in a critical statement. He said the prophet has no mission as health and medical orders but His mission has been to communicate jurisprudence, sharia, and the laws of religion. Therefore, reader of these studies and similar cases should always realize that he is researching in the context of historical knowledge.

Materials and Methods, Heritage Of Islamic Dating Material in Medieval

It was mentioned in introduction there is great legacy of Oriental and Western writings on behavior and character and lifestyle of Muhammad and his psychological saying , which are in Arabic, Persian, Latin, English , French , Indian , Chinese, and there are big flow of knowledge of Muhammad has become one of sources of science in world and Christian West begun extensive studies of knowledge of Muhammad five hundred years ago in eleventh century of Spain from Toledo but in eighteenth and nineteenth centuries it culminated [11], Italian prince wrote a book in forty volumes that examines evidence for forty years of Prophet’s behavior, The Biography of Muhammad: the Issue of the Sources, It is noteworthy that these historical materials related to Muhammad’s lifestyle came at the time were compiled that until the fourth century AH, the world witnessed a great urban movement based on the Prophet’s behavior in the urban development of Medina. Medina is the birthplace of the most civilized people in the Islamic world who have the behavior of an Islamic human being against the behavior of an ignorant human being .And the Prophet rejected ignorant behavior and replaced it with Islamic behavior [12-16].

Result, analyzing prophet’s behavior, observation in Mohammad style life

Behavioral science and psychology in Islamic philosophy One of the sciences that emerged in Islamic civilization is the science of psychology that scientifically examines the behavior, actions, and reactions of the human soul. the volume of Islamic teachings about the human soul and its behavior is modest that the Islamic civilization then became the most productive In Psychology and Ethics and Human Behavior that heretofore have been seen in the world. In this civilization it had been created unique results such as Avicenna an unparalleled man who co-founded the topic of sensory perception, which is a common theme of the behavioral sciences and cognitive sciences , In an empirical experiment, he proved the human soul, and several centuries after that, German Emperor Frederick II posed questions to his contemporary philosophers and sought to replicate and execute Avicenna’s experiment on the soul in Sicily al-Farabi who first examined the behavior of human societies. he separated individual behavior from social behavior and divided the types of behaviors into virtual cities and non-virtual societies. he is indeed a philosopher of societal behavior, he divided societies on the basis of human behavior to Ignorant cities and misguided communities.

One of the behaviors of misguided and ignorant societies is the struggle for survival over water, food, housing, clothing, and material necessities. Farabi has returned the root of society’s behavior to the innate, inherent of human being. This theory on the behavior of societies was repeated by seven centuries later [17]. he has identified the material cause of the struggle for survival with the inherent selfishness of man [18], the historical induction into the minds of philosophers before Farabi and after Hobbes and philosophers between the two, the analysis and explanation of the behavior of societies depends on a psychological theory of human nature, and the behavior of societies is subject to the self and psyche of human individuals. Societal behavior is a function of one’s self and psyche [19].

Monopoly of writing daily life to Muhammad, prophet of Islam by orientalis

The possibility of historiography of Muhammad’s complete lifestyle is a fact in field of orientalism and many orientalist have concluded that it is only possible to trace the Prophet’s daily lifestyle because only his body and grave are known, and there is a rich legacy of teachings on his behavior, interests, and tastes about food. , Clothing, socializingetc. There studied in his book behavior of Arab in two societies with two different life styles. “Muhammad in Mecca, Muhammad in Medina” examined Muhammad’s influence on behavior of two different societies and his change in behavior and attitudes has determined them. After Qur’an, which describes behavior man’s first book that wrote was book of Prophet’s behavior. The Prophet’s behavior writing is still prevalent among Islamic and non-Islamic scholars as in her book ,those are in his book La vie in his book Muhammad, His Life Based on the Earliest Sources, and watt in Mohammad in Meca and medina, F. E. Peters,in his book The Quest for Historical Muhammad, at the top of the teachings of Mohammad is a behavioral doctrine that is the main reason for his being a prophet.

The tradition of writing the Prophet’s behavior in Islamic civilization

In medieval literature and history there are texts that are the written legacy of Islamic civilization on the behaviors of individuals and nations. At the forefront is the travelogue of Shiite scholar. he traveled to India in the tenth century to report on the behavior of the India people, Several Islamic travelogues have described the behavior of European peoples and societies in the Middle Ages. as Reporting of They talked about the difference between the morals and the behavior of the people of the capital and the behavior of the people of the cities (Ibn Jubayr, Ibn Battuta and Ibn Khaldun, whom European orientalists have called him Montesquieu the Arab. he is the founder of the science of historical sociology.

He has examined the social-political behavior of heads of state and communities. His study is a kind of social psychology and is based on understanding human emotions .he has considered the kind of human feeling that can be studied simultaneously in the sciences of behavior, political science, ethics, and history as the driving force behind individual behaviors and community behaviors. he has written articles on sciences of soul and Islamic psychology, his theories on social dilemma and human behavioral education have been compared to those of contemporary psychologists, He has explored human thought and learned from the empirical reason for acquiring knowledge. his views of man are similar to Martin E. P. “Marty” Seligman in Positive Psychology.

Hygiene from prophet to averroes

There are in history of Islamic civilization in medieval The Prophet’s teachings on mental health and body and social behaviors culminated in five centuries by Ibn Rushd in his book in medicine “general in medicine“, (al-Koliyaat fi tab) “that is final version of Islamic medicine in medieval and and it was Ibn Rushd’s medical encyclopedia of medicine that studied in Europe until nineteenth century in Europe, which was called Colgate( Hunkke,….). It is dedicated to the evolution of the teachings of the Prophet. More than a hundred treatises on health and hygiene were written from the time of the Prophet to Ibn Rushd. These works begun with work of Prophet’s close successors such as who compiled in his book Islamic health education in the framework of the science of nutrition and medicine [20-24].

Divisions and Types of Hygiene in Prophet’s Hygiene and Health

The Prophet’s medical heritage shows that he drew the right pattern for a social and individual hygiene and person’s health behavior. The focus of his teachings is cleanliness and hygiene. In his teachings, he has introduced faith as a direct and dependent function of health and cleanliness. The Prophet’s instructions and rites in hygiene have been researched a lot so far. Among them is the book The First University and the Last Prophet in various issue of hygiene , behavior sciences , psychology in Islamic texts of medieval in forty volumes in the twentieth century, [11,25,26] The Prophet’s instructions for the protection of the body and the soul were collected after that, and so far it has been the main subject of research, and some, such as Ibn Khaldun, have looked at it critically and has discussed whether Prophet is obliged and present Shari’a and religion or whether he has issued health orders medical heritage left by the Prophet includes to heritage of body , soul, society , animals, trees, waters, clothes.

Some of these commands are as follows

a. Mental health: that the Prophet has many instructions about choosing the right color for belt shoes and all kinds of clothing.

b. Hygiene of the body.

c. The Prophet’s instructions on skin hygiene by choosing the right types of cotton yarn and the quality of clothing in terms of volume and materials.

d. Prophet’s instructions about dairy products.

e. 4-The Prophet’s instructions regarding food - in some cases, for example, he has mentioned sheep members for better quality nutrition.

f. 6- The Prophet’s advice on the quality of drinking and eating etiquette.

g. 7- Prophet’s instructions on walking etiquette

h. 8- Prophet’s instructions about the properties of fruits i. 9- Prophet’s instructions on speaking etiquette.

j. 10- Prophet’s instructions on marriage.

k. 11-The instructions of the Prophet during the occurrence of diseases and epidemics such as cholera and plague

Discussion in Aristotelian Roots of Islamic Civilization in Behavioral Sciences

Islamic Paradigm of Aristotle’s Book on the Soul Aristotle is Funder of psychology by his book on the soul and many scholars introduced this book as a book on psychology but this book reached Europe through Arabic literature and Islamic and Iranian teachings, and it is an Islamic paradigm. Therefore the most important aspect of this research paper is originality of psychology in Islam civilization [27-30]. Because in appearance, main capital of Islamic civilization in production of Islamic psychology is Aristotle’s book on soul but in historical reality, Aristotle’s book on the soul has been critiqued and analyzed by Muslim scholars for about seven centuries, and new scientific perspectives on soul have been presented. After Aristotle’s book on soul, writing essays in soul based this book is one of the initiatives and achievements of behavioral sciences in Islamic civilization. Aristotle’s Treatise on the Soul was translated into Arabic in second half of the eighth century A D, A later Arabic translation of Aristotle book on soul into Arabic by Ishaq ibn made a translation into Arabic from Syriac. The Arabic versions show a complicated history of mutual influence. Avicenna and al-Farabi wrote independent writings on nature of human soul, study of soul in works of, then Ibn Rushd analyze process of soul and natural and perfect behavior of man in relation to behavior of perfect man. The Aristotelian paradigm of the soul is an Islamic paradigm that was formed by Muslims, led by Ibn Sina in the Middle Ages, and entered the field of Christian philosophy and Christian theology through Islamic theology. Encouragement of Frederick II the study of Islamic sciences including Aristotelian psychology, had been developed. This is one of obvious issues in the history of philosophy and humanity and literature of medieval [30-34].

Perfect man behavior, capital of psychology, attitude, behavior, emotion

Jesus and Muhammad are perfect man in systematic theology of Christian and Islam in medieval. Common denominator of selfstudy analyzed, explained, and accepted and understandable in psychology school of Gestalt and within framework of intuitive theories about social behavior. Our intuitive efforts to make scientific arguments about everyday life are fruitful, if intuitive understanding of behavior was validated by humans, and if intuitive theories about human behavior were not valid, our social interactions would be severely impaired.

Conclusion

The Prophet’s tradition is capital of human and social attitudes, and social psychologists consider attitude to be the symbol of three components: cognitive, emotional, and behavioral function. Attitudes help us to understand our surroundings and to express our values through function (and the function of self-defense. No on e has ever been able to find a better alternative to Muhammad’s lifestyle to determine human behavior, and all efforts have been in vain because one of essential purposes of Prophet’s behaviors and traditions is to provide a solid foundation for good human behavior. For centuries, some philosophers have tried, like, to find new ethics based on biology and other sciences.

https://lupinepublishers.com/psychology-behavioral-science-journal/pdf/SJPBS.MS.ID.000182.pdf

https://lupinepublishers.com/psychology-behavioral-science-journal/fulltext/the-concept-of-science-in-islamic-civilization-the-case-psychology-and-behavior-sciences.ID.000182.php

For more Lupine Publishers Open Access Journals Please visit our website: https://lupinepublishersgroup.com/

For more Psychology And Behavioral Sciences Please Click

Here: https://lupinepublishers.com/psychology-behavioral-science-journal/

To Know more Open Access Publishers Click on Lupine Publishers

Follow on Linkedin : https://www.linkedin.com/company/lupinepublishers

Follow on Twitter : https://twitter.com/lupine_online

0 notes

Text

Rajma Masala Might Be the Perfect Cupboard Comfort Dish for Our Times

Getty Images/iStockphoto

The north Indian kidney bean curry is a dish that forgives you if you do not have all the spices, and rewards you for patience and generosity

In the first few weeks of sheltering in place, I found a packet of old rajma in my pantry — that is to say, I stumbled upon a small treasure. Strictly speaking, it was an American brand, so the label on the bag read “kidney beans,” but their magic was the same.

I soaked them overnight and they bloomed into large, toothy beans already splitting at the seams. Boiling them turned their surrounding water brown and thick; I cooked them with onions, tomatoes, and whatever spices I had, and simmered it for hours, using the liquid from bean boiling to thicken the mix. In the end I had made the perfect dish of rajma masala — a rich North Indian kidney bean curry — even if it took me two extra hours of simmering, since I didn’t account for the added cook time for old beans.

Like so many of the world’s recipes that rely on hardy pantry staples, rajma masala is an ideal pandemic dish. You can turn to it when grocery runs are limited and time at home abundant. Its base recipe demands largely shelf-stable ingredients, and like the various bean chili riffs of the Americas, is a soothing comfort food for those who grew up with it. (To New York Times restaurant critic Tejal Rao, rajma masala is “her family’s store-cupboard comfort food” and the “indisputable king” of bean dishes.) Also like chili, there’s an acidic tomato base to cut through the bean’s inherent creaminess, and though it’s heavily spiced, it is a dish that forgives you if you do not have all the spices, and rewards you for patience and generosity.

“The beauty is that it is not instant gratification,” says Oxford, Mississippi-based chef Vishwesh Bhatt, who makes batches of Louisiana red beans to share with his neighbors. “Beans and rice are universal comfort foods, communal, big pot dishes— they lend themselves to sharing.”

After I posted photos of my own rajma masala efforts to Instagram, friends, both South Asian and otherwise, slid into my DMs to ask for the recipe and tips. Similarly, when food writer Priya Krishna posted a photo of her rajma chawal — rajma masala with rice — 10 people responded immediately, and more the next day, telling her that they too had been making rajma at home. Krishna, who grew up eating rajma, had cooked it with her mother while sheltering in place with her family in Dallas, but notes, “I hesitate to call what millions of people do everyday a trend.” Fair point.

It is true that what seems remarkable in the diaspora is not really so remarkable in the subcontinent. Would anyone in India really care that anecdotally, about 20 people also made rajma masala the same day that Krishna and I did? While I had finished the bulk of this essay before Alison Roman’s comments about two Asian women’s business endeavors kicked up a storm in food media, I am finishing it in the aftermath. It is true that writing about food is a fraught endeavor that skirts appropriation and neocolonialism — that often, food personalities exploit other cultures and their own. Exotification is, after all, an orientalist, capitalist ploy. And in learning more about the rajma bean, I have uncovered another complication in my notion of what is traditional desi, or Indian, cuisine, and — as an Indian immigrant to Turtle Island, another reason to honor the ancestors of this land.

Rajma masala may taste and feel like an ancient Indian dish, but its past is marked by cultural and colonial exchange, its recipe scarcely older than my grandfather. While rajma masala is a modern icon of North Indian food, the bean itself is not indigenous to the subcontinent, and neither is the dish’s base, tomato. “Ingredients that seem to many to be inextricably part of an Indian diet are not always autochthonously Indian,” writes historian Anita Mannur in her 2010 book Culinary Fictions: Food in South Asian Diasporic Culture.

The kidney bean originates in the Americas, with sources pointing to Mexico and Peru. The bean journeyed from the New World to the Old, and then onward through the spice trade routes to Asia, in what is known as the Columbian exchange, where beans and other plants and animals and peoples and information and diseases were passed between continents in the 15th and 16th centuries. “We think we’re globalizing now, but look to the 1500s,” says Mannur, who co-edited Eating Asian America: A Food Studies Reader. “The irony is that in looking for India, Columbus bizarrely transformed the Indian diet.”

The bean’s beneficial properties as a nutrient-dense dried protein source, Mannur tells me, made it a good food for long nautical journeys. Portugal’s ships, filled largely with degredados — convict exiles who often died of dysentery and typhoid along the spice route, and were promised one chest worth of expensive spices to take home if they made the journey — arrived on the western coast of India. Goa, which became Portugal’s capital in India in 1530, was a hub for much internal trade — and was how the tomato and chile pepper took root in Indian cuisine.

It is possible that the bean made it up through the cattle caravan routes to the Mughal Empire in the north — but the recipe for rajma masala doesn’t really crop up until as recently as around 130 years ago, says culinary archaeologist Kurush Dalal. Dalal thinks it’s unlikely the kidney bean was traded by the Portuguese, even if they ate it themselves, because it is not mentioned in medieval Indian texts.

“There is evidence that the French brought the rajma bean from Mexico to Pondicherry,” he tells me, calling the French the “best conduit.” The French, who colonized Pondicherry on the Eastern coast of India, had mounted the Second French Intervention in Mexico in the 1860s, spearheaded by Emperor Napoleon III. (Cinco De Mayo celebrates the day the French were defeated by the Mexicans in 1862.) There is no paper trail of how it ends up in the hills of the North — though logically, it makes sense for the hearty bean to become more popular in cooler climates, where one would burn more calories. In the wetter, hotter south, such a bean would throw off the Ayurvedic energies of vata and pitta, Dalal speculates.

Rajma masala, which made a place for itself in North Indian cuisine, is not as popular in the South. Mannur remembers being told at a restaurant in Mangalore — another erstwhile Portuguese capture — that the North Indian thali was unique because it featured rajma masala.

“Methods of preparing rajma masala are not too different from how Latin Americans made chili,” says Mannur. Like Goan vindaloo, which retained both its Portuguese name and the foreign ingredient of vinegar, rajma masala folded in local ingredients like its spices and the Asian-origin onion, but kept its base of tomatoes and chile peppers, imports from long ago.

Of course, the bean’s entree into the international plate was accompanied by pandemics brought on by Columbus and his ilk, who pillaged the global south, devastating populations and colonizing them along the way.

And this is where a cruel mirror image emerges: A few hundred years ago, millions of Indigenous people died after European contact brought with it an onslaught of new diseases, then departed with native foods, including beans. Now here we are again in the midst of another pandemic, hastened and marked by irresponsible tourism, largely impacting vulnerable populations, especially Native Americans for whom “disease has never been just disease.”

Food exchange has historically been a story of carnage, and the hegemony established continues to benefit from these massacres that unwittingly introduced foods like beans to the world.

Beans that we’re now all staring at in our pantries, wondering how to best cook. Rajma masala came together on the other side of the world — to cook the beans in their “land of origin” feels like a nod to its history. Here, then, are some tips on how best to cook these lovely, storied beans.

How to Make Rajma Masala

Step 1: Procure

Red kidney beans are available at most grocery stories, whether canned or dry. Buy some onions and tomatoes (or tomato paste) while you’re at it. Cilantro leaves will brighten your finished dish. Check your pantry for the usual suspects: chiles, garlic, ginger, cumin, cardamom, cinnamon, bay leaves. If you’re missing any ingredients, or just want to punch up the flavor, the easiest cheat is to buy garam masala — well, the actual easiest would be to buy some rajma masala powder.

Step 2: Soak

“Not all beans are created equally,” says molecular biologist and food writer Nik Sharma. Rajma is a fatty bean, while the chickpea is both fatty and carby — these properties affect how you cook a bean. And while it’s a beautiful thing that the kidney bean can sit on a shelf for a year and still be delicious, the older the bean, the longer it takes to cook. “The skin contains magnesium and calcium,” which create water barriers. It holds in itself pectin, the same tough ingredient that makes jam gel together, and the calcium makes it insoluble.

If you’re using dry beans, you’ll have to soak them. Mannur cautions that faster processes may reduce some of the nutrients. She soaks beans overnight — “My mother was right, but I’ll never tell her.”

Step 3: Boil

Not all food legends are true. For example, we’re told that we must shave off the foam buildup from boiling beans because that foam contains whatever makes you gassy. Sharma, whose book The Flavor Equation will come out this October, says that this is a common misconception. The foam does not make you gassy; improperly cooked kidney beans do, though, if the complex carbohydrate does not break down. The precipitate is removed during the canning process, he says, so you don’t get it confused with bacteria — “it’s not poisonous itself, it’s just quality assurance.”

And Sharma has a secret that he’s willing to share as a tip, and it’s baking soda. “I did an experiment,” he says. Adding baking soda to boiling water and beans cut down the cook time from 4 hours to a mere 30 minutes.

Step 4: Make the Base

“You cook the masala with tomato and onion until the fat separates,” says Sharma, and know that canned tomato is chemically different from fresh tomato, that its acids and sugars have changed in the canning process — so start with fresh tomato, and judiciously add canned slowly, tasting every time. The rest (the spices, that is) is tweakable. I like to use garlic, ginger, cumin, red chile powder, a bit of garam masala, cardamom, and cinnamon.

Step 5: Combine

Hopefully your beans are cooked, somewhere between al dente and exploded. Throw them into the onion-tomato base and add the leftover bean water. I did this gradually. It renders a much thicker base than if you were to use water. Simmer for 20 minutes, checking for consistency. It should be thick and stew-like, not dry or watery.

Step 6: Eat and share

Serve it to yourself with rice. Squeeze a bit of lemon to cut the richness, and sprinkle on some chopped cilantro for sparkle. Or better yet, take a page out of Vishwesh Bhatt’s book, and make a ton. Separate the servings into jam jars. Leave them on your neighbor’s doorsteps as a contactless embrace and a reminder of the bean, its story, and how far it traveled.

Aditi Natasha Kini writes cultural criticism, essays, and other text objects from her apartment in Ridgewood, Queens.

from Eater - All https://ift.tt/2B4rzET

https://ift.tt/3fGeAZa

Getty Images/iStockphoto

The north Indian kidney bean curry is a dish that forgives you if you do not have all the spices, and rewards you for patience and generosity

In the first few weeks of sheltering in place, I found a packet of old rajma in my pantry — that is to say, I stumbled upon a small treasure. Strictly speaking, it was an American brand, so the label on the bag read “kidney beans,” but their magic was the same.

I soaked them overnight and they bloomed into large, toothy beans already splitting at the seams. Boiling them turned their surrounding water brown and thick; I cooked them with onions, tomatoes, and whatever spices I had, and simmered it for hours, using the liquid from bean boiling to thicken the mix. In the end I had made the perfect dish of rajma masala — a rich North Indian kidney bean curry — even if it took me two extra hours of simmering, since I didn’t account for the added cook time for old beans.

Like so many of the world’s recipes that rely on hardy pantry staples, rajma masala is an ideal pandemic dish. You can turn to it when grocery runs are limited and time at home abundant. Its base recipe demands largely shelf-stable ingredients, and like the various bean chili riffs of the Americas, is a soothing comfort food for those who grew up with it. (To New York Times restaurant critic Tejal Rao, rajma masala is “her family’s store-cupboard comfort food” and the “indisputable king” of bean dishes.) Also like chili, there’s an acidic tomato base to cut through the bean’s inherent creaminess, and though it’s heavily spiced, it is a dish that forgives you if you do not have all the spices, and rewards you for patience and generosity.

“The beauty is that it is not instant gratification,” says Oxford, Mississippi-based chef Vishwesh Bhatt, who makes batches of Louisiana red beans to share with his neighbors. “Beans and rice are universal comfort foods, communal, big pot dishes— they lend themselves to sharing.”

After I posted photos of my own rajma masala efforts to Instagram, friends, both South Asian and otherwise, slid into my DMs to ask for the recipe and tips. Similarly, when food writer Priya Krishna posted a photo of her rajma chawal — rajma masala with rice — 10 people responded immediately, and more the next day, telling her that they too had been making rajma at home. Krishna, who grew up eating rajma, had cooked it with her mother while sheltering in place with her family in Dallas, but notes, “I hesitate to call what millions of people do everyday a trend.” Fair point.

It is true that what seems remarkable in the diaspora is not really so remarkable in the subcontinent. Would anyone in India really care that anecdotally, about 20 people also made rajma masala the same day that Krishna and I did? While I had finished the bulk of this essay before Alison Roman’s comments about two Asian women’s business endeavors kicked up a storm in food media, I am finishing it in the aftermath. It is true that writing about food is a fraught endeavor that skirts appropriation and neocolonialism — that often, food personalities exploit other cultures and their own. Exotification is, after all, an orientalist, capitalist ploy. And in learning more about the rajma bean, I have uncovered another complication in my notion of what is traditional desi, or Indian, cuisine, and — as an Indian immigrant to Turtle Island, another reason to honor the ancestors of this land.

Rajma masala may taste and feel like an ancient Indian dish, but its past is marked by cultural and colonial exchange, its recipe scarcely older than my grandfather. While rajma masala is a modern icon of North Indian food, the bean itself is not indigenous to the subcontinent, and neither is the dish’s base, tomato. “Ingredients that seem to many to be inextricably part of an Indian diet are not always autochthonously Indian,” writes historian Anita Mannur in her 2010 book Culinary Fictions: Food in South Asian Diasporic Culture.

The kidney bean originates in the Americas, with sources pointing to Mexico and Peru. The bean journeyed from the New World to the Old, and then onward through the spice trade routes to Asia, in what is known as the Columbian exchange, where beans and other plants and animals and peoples and information and diseases were passed between continents in the 15th and 16th centuries. “We think we’re globalizing now, but look to the 1500s,” says Mannur, who co-edited Eating Asian America: A Food Studies Reader. “The irony is that in looking for India, Columbus bizarrely transformed the Indian diet.”

The bean’s beneficial properties as a nutrient-dense dried protein source, Mannur tells me, made it a good food for long nautical journeys. Portugal’s ships, filled largely with degredados — convict exiles who often died of dysentery and typhoid along the spice route, and were promised one chest worth of expensive spices to take home if they made the journey — arrived on the western coast of India. Goa, which became Portugal’s capital in India in 1530, was a hub for much internal trade — and was how the tomato and chile pepper took root in Indian cuisine.

It is possible that the bean made it up through the cattle caravan routes to the Mughal Empire in the north — but the recipe for rajma masala doesn’t really crop up until as recently as around 130 years ago, says culinary archaeologist Kurush Dalal. Dalal thinks it’s unlikely the kidney bean was traded by the Portuguese, even if they ate it themselves, because it is not mentioned in medieval Indian texts.

“There is evidence that the French brought the rajma bean from Mexico to Pondicherry,” he tells me, calling the French the “best conduit.” The French, who colonized Pondicherry on the Eastern coast of India, had mounted the Second French Intervention in Mexico in the 1860s, spearheaded by Emperor Napoleon III. (Cinco De Mayo celebrates the day the French were defeated by the Mexicans in 1862.) There is no paper trail of how it ends up in the hills of the North — though logically, it makes sense for the hearty bean to become more popular in cooler climates, where one would burn more calories. In the wetter, hotter south, such a bean would throw off the Ayurvedic energies of vata and pitta, Dalal speculates.

Rajma masala, which made a place for itself in North Indian cuisine, is not as popular in the South. Mannur remembers being told at a restaurant in Mangalore — another erstwhile Portuguese capture — that the North Indian thali was unique because it featured rajma masala.

“Methods of preparing rajma masala are not too different from how Latin Americans made chili,” says Mannur. Like Goan vindaloo, which retained both its Portuguese name and the foreign ingredient of vinegar, rajma masala folded in local ingredients like its spices and the Asian-origin onion, but kept its base of tomatoes and chile peppers, imports from long ago.

Of course, the bean’s entree into the international plate was accompanied by pandemics brought on by Columbus and his ilk, who pillaged the global south, devastating populations and colonizing them along the way.

And this is where a cruel mirror image emerges: A few hundred years ago, millions of Indigenous people died after European contact brought with it an onslaught of new diseases, then departed with native foods, including beans. Now here we are again in the midst of another pandemic, hastened and marked by irresponsible tourism, largely impacting vulnerable populations, especially Native Americans for whom “disease has never been just disease.”

Food exchange has historically been a story of carnage, and the hegemony established continues to benefit from these massacres that unwittingly introduced foods like beans to the world.

Beans that we’re now all staring at in our pantries, wondering how to best cook. Rajma masala came together on the other side of the world — to cook the beans in their “land of origin” feels like a nod to its history. Here, then, are some tips on how best to cook these lovely, storied beans.

How to Make Rajma Masala

Step 1: Procure

Red kidney beans are available at most grocery stories, whether canned or dry. Buy some onions and tomatoes (or tomato paste) while you’re at it. Cilantro leaves will brighten your finished dish. Check your pantry for the usual suspects: chiles, garlic, ginger, cumin, cardamom, cinnamon, bay leaves. If you’re missing any ingredients, or just want to punch up the flavor, the easiest cheat is to buy garam masala — well, the actual easiest would be to buy some rajma masala powder.

Step 2: Soak

“Not all beans are created equally,” says molecular biologist and food writer Nik Sharma. Rajma is a fatty bean, while the chickpea is both fatty and carby — these properties affect how you cook a bean. And while it’s a beautiful thing that the kidney bean can sit on a shelf for a year and still be delicious, the older the bean, the longer it takes to cook. “The skin contains magnesium and calcium,” which create water barriers. It holds in itself pectin, the same tough ingredient that makes jam gel together, and the calcium makes it insoluble.

If you’re using dry beans, you’ll have to soak them. Mannur cautions that faster processes may reduce some of the nutrients. She soaks beans overnight — “My mother was right, but I’ll never tell her.”

Step 3: Boil

Not all food legends are true. For example, we’re told that we must shave off the foam buildup from boiling beans because that foam contains whatever makes you gassy. Sharma, whose book The Flavor Equation will come out this October, says that this is a common misconception. The foam does not make you gassy; improperly cooked kidney beans do, though, if the complex carbohydrate does not break down. The precipitate is removed during the canning process, he says, so you don’t get it confused with bacteria — “it’s not poisonous itself, it’s just quality assurance.”

And Sharma has a secret that he’s willing to share as a tip, and it’s baking soda. “I did an experiment,” he says. Adding baking soda to boiling water and beans cut down the cook time from 4 hours to a mere 30 minutes.

Step 4: Make the Base

“You cook the masala with tomato and onion until the fat separates,” says Sharma, and know that canned tomato is chemically different from fresh tomato, that its acids and sugars have changed in the canning process — so start with fresh tomato, and judiciously add canned slowly, tasting every time. The rest (the spices, that is) is tweakable. I like to use garlic, ginger, cumin, red chile powder, a bit of garam masala, cardamom, and cinnamon.

Step 5: Combine