#and the rise series took a risk and tried new things resulting in the franchise having a fresh new personality

Text

TMNT 1987 had the Nostalgia

TMNT 2003 had the Story

TMNT 2012 had the Heart

ROTTMNT had the Personality

#we stan all tmnt versions on this blog#we love the 87 series for its nostalgic feeling#The 2003 series honestly had the best continuing story and plot#The 2012 series had so much passion put into its characters and how much they wanted to explore new stories/elements in the show#and the rise series took a risk and tried new things resulting in the franchise having a fresh new personality#if I see hate I’m blocking#tmnt#teenage mutant ninja turtles#tmnt 1987#tmnt 2003#tmnt 2012#tmnt 2018#rottmnt#rise of the tmnt#rise of the teenage mutant ninja turtles#I saw a comment on YouTube say this I feel this is the best way to describe the four tmnt tv shows

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Shin Megami Tensei II

(Part 7 of the MegaTen thing)

WARNING: This review contains some moderate spoilers for SMT1 and 2! Read at your own risk!

At last! After two years and three games of questionable quality under their belt, Atlus finally decided to stop fooling around and got its shit together to develop a proper sequel to SMT1. Honestly, the time frame between Majin Tensei and SMT2 means they were probably developed concurrently. There were likely several teams working on these games and Majin Tensei just happened to have been finished first or something like that. Regardless, as one playing through the series in order, I was pleased after Majin Tensei was over, first because it was over, and second because the next title in line was Shin Megami Tensei II.

I was really looking forward to SMT2 at the time. I remember I was in my dentist grandfather’s home about 80 miles away from mine because a tooth restoration had gone somewhat awry and I needed a root canal. During the final moments of Majin Tensei, I had to deal with severe tooth pain, which only heightened the distress of the whole situation, but now - I thought - maybe my gaming experience of the day will alleviate the pain instead of making things worse.

As you boot up the game, you’re treated to a “no relation to real life persons” screen, which I found kind of funny. SMT2 is, in general, much less close to real life than SMT1 was, and no game so far concerned itself with the disclaimer, so I wonder what could have happened behind the scenes to warrant it here. I guess it was because of the intense religious symbolism and inspiration, much bigger than in any other game of the series so far, but I’m not 100% sure. Anyway, I found it interesting.

Anyway, once you get past that, some introductory exposition begins. The game takes place after the Neutral ending of SMT1, and during this cutscene, you are informed that a city, Tokyo Millenium, was built on the site of the ruins of the final dungeon in that game by member of the Messian church, the Law faction representatives of the series.

Of course, this means that the grip of the Messians reaches far in SMT2. Huge chunks of the plot are dedicated to things related to them, their methods, and their relation with Millenium itself. It’s pretty surreal to see a game from this franchise embrace such an overbearing anti-Law philosophy for major, obligatory bullet points in the script, and the whole time I kept thinking “the axis is still there, right? What could the Law path possibly even be about?” and thinking back to how this dynamic existed in SMT1. As I said in my review of that game, on some levels it was a bit arbitrary to select which side you wanted to join, and there were a lot of parallels between them that made the choices feel like they were just giving me an illusion of control. I’m really glad they decided to mature from that and offer a narrative that seems to directly challenge the notion of parallelism that was built in the first installment. Well, spoiler alert, even the Law path is a tad antiestablishment this time around - there’s really no way it couldn’t have been, given the ambitions of the story - and goes against the unrighteousness of the Messians behind Millenium’s stranger, more questionable happenings.

I will say though, it still doesn’t feel like there’s a lot of basic difference between law and chaos, but for different reasons this time around. There is definitely no parallels as to story significance here, but the goals of all alignment paths end up feeling pretty similar. I think the best way to illustrate my point is to note that SMT1 had 3 ways the final part of the game could go, depending on your alignment, but they were basically 2 mirrors of each other and you could either go one way for Law, the other way for Chaos, or both ways for Neutral. In this game, the conditions at which you reach the final point are pretty different (though Neutral feels extremely close to Chaos all the way through SMT2 and the end is no exception), but the final boss is always the same for all three alignments. It makes things a bit of an interesting experience and a definite change of pace from SMT1, but I can’t help but feel, way in the back of my mind, that this story… wasn’t supposed to have the SMT axis, you know? As I said, Neutral and Chaos are very similar and kind of work the same, while Law is basically the game coming up with excuses as to why the player engages in the same activities as the other two, but with different intentions. Frankly, I don’t really need alignment, particularly. I never thought it was an essential element of the series, so it didn’t truly bother me at all, and I mostly thought about this after having already finished playing. For those who might be expecting a more exciting, more philosophical clash of visions and well-developed ideologies, however, I’m afraid SMT2 still falls short of that. But hey, it’s still a commendable effort for 1994, and it feels a lot more adult than its peers at the time.

The plot itself, as is, is very enjoyable. Whereas 1 had a more episodic structure with clear events separating one part of the game from the next, 2 opts for a more continuous progression. There are still momentous events that break up the game and result in major landscape changes, but they’re not as prominent as the ones from the first game. Everything has a bit of a surreal tone to it, and it borrows far more from classic cyberpunk tropes than 1 did. While 1 eventually engages in a post-apocalyptic scenario, it’s more just an excuse to start putting in motion its more outlandish plot points regarding demons and the rising relevance of its fictional figures. 2 fully embraces its setting and extrapolates quite a lot on stuff that had been set up, tackling themes of classism and social discrimination through the tried-and-true methods of a city that’s divided into multiple sectors with a different quality of life and purpose for each of them, as well as several slum-like locales where you come across the people that fell victim to the injustice and cruelty of the governmental powers that be. It also expands quite a bit on the personalities of the different demon races. A new axis was properly established, Light vs. Dark, the axis of virtue, which for now doesn’t serve much of a gameplay purpose but possibly helped the devs more clearly visualize the roles of all the dozens of demon subfactions that exist in the game. Though there is still no shortage of human character-based interaction, a significant amount of time was dedicated to giving the demons themselves more of a persnality and inner quarrels between one another. These elements I described kind of interact with each other; there are some correlations between them and sometimes you have to use items acquired in a certain arc to progress in a different, mostly unrelated arc later on, but I feel like the interconnectivity of the game as a big picture thing could have been deeper.

On that note, we can go on to say that, while I felt like the characters in 1 had more permanence overall, sticking around for longer periods of time before something made the relevant cast rotate around, 2 feels more cyclical with them, making you stumble upon each of the relevant ones at a larger number of points in the storyline but keeping their appearances shorter in comparison. In my opinion, it’s preferrable that way, because old games like these tended to not really develop characters too much while they were with you, instead choosing to further their role in the story at select few moments, so with a larger number of them, a greater amount of interesting developments can occur. However, by the same note, it also feels like they were juggling more separate plot threads of their own as the player’s involvement switches between each faster than they did in 1, which mostly had a central focus for each of its “episodes”.

Even the protagonist himself, while still silent, receives some plot development of his own, perhaps a lesson learned from Last Bible 2 and Majin Tensei. His particular role and how it relates to the other relevant characters is actually one of the highlights of the plot, but I find it doesn’t pay off much in regards to the third act, besides possibly explaining his ability to take down hordes of powerful demons. It’s still interesting to witness though.

Speaking of hordes of demons, I find the game to be as easy as ever. This time, magic effect ammunition has been significantly nerfed, but now it kind of seems like most the time the enemies are just… not really threatening. The first proper arc of the game managed to kill me twice because it’s the beginning and the game has greater control of the circumstances before the huge amount of levels starts piling on and making build possibilities ever more variable. After that, though, the rest is a cakewalk. I’m not a particularly diligent demon recruiter, I didn’t go out of my way to farm for valuable equipment, I never found any sword fusion candidates worth my time, yet I still managed to blaze through the entire game with no problems whatsoever. I wish it had been more difficult, because SMT2 starts losing control of itself again and tossing ridiculosuly powerful - in lore terms - demons at you as you get close to the end. However, the simplicity and repeatability of attack strategies which prove reliable through the entire game means that, for the fifth time, that auto-battle option was put under quite a bit of use, even for these powerful guys. It took out some of the visceral, immersive quality that a properly set up, difficult enemy can have.

Still, I feel like this time, the interesting, juicy plot and the exploration factor kept me from being really bothered by the lack of difficulty. Things are much more streamlined than they were in 1 now. I will admit, conceptually I don’t appreciate the layout and presentation of the world map. As in SMT1, you’re represented by a blue spinning pointer thing, but everything around you is, as mentioned previously, sectioned off, and each section consists of a relatively short, linear walk through a bland, bluish cityscape with token building decorations that feel like you’re dragging your finger through a board game or a chalk drawing on the ground acting like that stands in for movement. It’s very artificial, and when you enter a battle in the world map, you can actually catch a glimpse of what the city looks like, with what seems to be some verticality and layers and quite a dense skyline. It’s the first glimpse in the entire series of a truly awe-inspiring, immersive setting. I wish it were like that all the way through.

Furthermore, first-person areas are as labyrinthine as ever, with maze-like designs with no regard for how it would actually translate to any real place, and a repeated texture that prevents the addition of decoration, flavor or personality. By 1994, it has started to get on my nerves, and it feels unbecoming of a story that, in my opinion, oozes personality on its own. They’re not boring, per se, as they interact nicely with the world map and with their own setpiece trigger tiles (a series staple at this point) to create a raw gameplay experience that feels stimulating as you work through to your next destination. There’s some enjoyment to be had in going really far in one direction, going out into the world map, then into a new area, then out through another exit, then into some other place and so on, progressing with no save point in sight and an ever dwindling supply of resources, getting more and more uncertain you’re even going the right way, until the game gives you some cutscene that confirms that you were doing the right thing all along. I’m glad that, even though there’s a new system in place that basically tells you whete you need to go, it’s still used in a way that leaves the player guessing the internal elements of the journey, and the game balances short bursts of activity and long treks in a satisfying way that kept things interesting from a gameplay perspective. There is an arc where you’re directly going after McGuffins, but I think it’s pulled of with some grace here; there’s a point to it, and once again the ways in which you collect them are an excuse for the designers to get a little cuter with their level design.

Speaking of which, one of the biggest draws for me is that SMT2 starts getting really quirky. Copyright protected versions of Beetlejuice and Michael Jackson make an appearance, there’s a silly reference to Berserk, you barge in on Belphegor sitting in his toilet and kill him while he takes a dump, some demons ask you if you’re gonna turn them into a bundle of experience points, you have to enter a dance contest and steal chameleon-esque robes from a nymph while she takes a shower… A lot of crazy, quirky, funny things happen that help elevate the game and the series’s personality quite a bit, and I feel like there’s a level of confidence and playfulness on the part of the designers, having put in so many things that can go against the somber tone of the narrative, that I can truly appreciate. It’s sort of the same balance of silly and mature/horrifying that would exist in Shadow Hearts a few years down the line, but I feel like SMT2 is much more careful and restrained about it, mostly relegating the silliness to short setpieces to spice up the progression, and it ends up better for it.

When I first heard about the Shin Megami Tensei series, working my way back from Persona 3 and researching some fundamental aspects of the mythos, as well as hearing about how good it all was, I formed a certain image in my mind. It wasn’t very tangible, but it was a high-expectations fueled idealization of what a game with this kind of potential could be like. So far, games in the series haven’t really been able to deliver on that so much. Shin Megami Tensei II is, I believe, the first one to take steps in the direction of this idealization. It plays a lot more with its tropes, it isn’t afraid of utilizing whichever established figure it had througout the series to make a little bit more of a philosophical point this time around, there’s development by the hands of the human characters, and by the end, it feels grand and satisfying. My rating for this game is a very appreciative 7.6 out of 10. Though the gameplay still needs work, I had a blast playing it and enjoying its wackiness and its more somber points on human relationships. They’re simplistic, yes, nothing compared to literary works presenting the same kinds of fundamental points, but in those, you can’t pump the devil’s face full of lead after a chinese turtle god cast tarukaja on you several times in a row so that your bullets come out with the world’s vengeance on their shoulders. If you’re a fan of old-school games, and would like to try out a more complete, more fully visualized old MegaTen story, I really think you should try this game. I liked it quite a bit.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Celebrating the undersung heroism of The Peanuts Movie

In December 2015, a movie reboot of one of history’s most beloved entertainment brands was released in cinemas, and it took the world by storm. That movie was not The Peanuts Movie.

Not that I’m setting myself up as an exception to that. Like pretty much everyone else, I spent the tail-end of 2015 thoroughly immersing myself in all things Star Wars: The Force Awakens, drinking deeply of the hype before seeing it as many times as I could - five in total - before it left theatres. In the midst of all that Jedi madness, I ended up totally forgetting to see The Peanuts Movie, Blue Sky Studios’ well-reviewed adaptation of Charles M. Schulz’s classic newspaper strip, which I’d been meaning to catch over the festive period. But then, it’s not as though the schedulers made it easy for me; in the US, there had been a buffer zone of a month between the launches of the two films, but here in the UK, Peanuts came out a week after Star Wars; even for this animation enthusiast, when it came to a choice between seeing the new Star Wars again or literally any other film, there was really no contest at all.

A year later, belatedly catching up with the movie I missed at the height of my rekindled Star Wars mania proved an eye-opening experience, and places Blue Sky’s film in an interesting context. With a $246.2 million worldwide gross, The Peanuts Movie did well enough to qualify as a hit, but it remains the studio’s lowest earner to date; in retrospect, it seems likely that going head-to-head with Star Wars and the James Bond movie Spectre didn’t exactly maximise its chances of blockbuster receipts. Yet in an odd way, modest, unnoticed success feels like a fitting outcome for The Peanuts Movie, a film that acts as a perfectly-formed celebration of underappreciated decency in a world of bombast and bluster. Charlie Brown, pop culture’s ultimate underdog, was never fated to emerge victorious in a commercial battle against Han Solo and James Bond, but his movie contains a grounded level of heartfelt sympathy for the small-scale struggles of unassumingly ordinary folk that higher-concept properties don’t have the time to express. The Peanuts Movie is a humbly heroic film about a quietly laudable person, made with understated bravery by underrated artists; I hope sincerely that more people will discover it like I did for years to come, and recognise just how much of what it says, does and represents is worth celebrating.

CELEBRATING... BLUE SKY STUDIOS

Before giving praise to The Peanuts Movie itself, it’d be remiss of me not to throw at least a few kind words in the direction of Blue Sky Studios - a group of filmmakers who I’m inclined to like, somewhat despite themselves, and who don’t always get very kind things written about them. After all, the 20th Century Fox subsidiary have been in the CGI feature animation mix since 2002, meaning they have a more established pedigree than most studios, and their long-running Ice Age franchise is a legitimately important, formative success story within the modern era of American animation. Under the creative leadership of Chris Wedge, they’ve managed to carve and hold a niche for themselves in a competitive ecosystem, hewing close to the Shrek-inspired DreamWorks model of fast-talking, kinetic comedy, but with a physical slapstick edge that marked their work out as distinct, at least initially. Sure, the subsequent rise of Illumination Entertainment and their ubiquitous Minions has stolen that thunder a little, but it’s important to remember that Ice Age’s bedraggled sabretooth squirrel Scrat was the CGI era’s original silent comedy superstar, and to recognise Blue Sky’s vital role in pioneering that stylistic connection between the animation techniques of the 21st century and the knockabout nonverbal physicality of formative 20th century cartooning, several years before anyone else thought to do so.

For all their years of experience, though, there’s a prevailing sense that Blue Sky have made a habit of punching below their weight, and that they haven’t - Scrat aside - established the kind of memorable legacy you’d expect from a veteran studio with 15 years of movies under their belt. Like Illumination - the studio subsequently founded by former Blue Sky bigwig Chris Meledandri - they remain very much defined by the influence of their debut movie, but Blue Sky have unarguably been a lot less successful in escaping the shadow of Ice Age than Illumination have in pulling away from the orbit of the Despicable Me/Minions franchise. Outside of the Ice Age series, Blue Sky’s filmography is largely composed of forgettable one-offs (Robots, Epic), the second-tier Rio franchise (which, colour palette aside, feels pretty stylistically indistinct from Ice Age), and a pair of adaptations (Horton Hears a Who!, The Peanuts Movie) that, in many ways, feel like uncharacteristic outliers rather than thoroughbred Blue Sky movies. Their Ice Age flagship, meanwhile, appears to be leaking and listing considerably, with a successful first instalment followed by three sequels (The Meltdown, Dawn of the Dinosaurs and Continental Drift) that garnered successively poorer reviews while cleaning up at the international box office, before last year’s fifth instalment (Collision Course) was essentially shunned by critics and audiences alike. Eleven movies in, Blue Sky are yet to produce their first cast-iron classic, which is unfortunate but not unforgivable; much more troubling is how difficult the studio seems to find it to even scrape a mediocre passing grade half the time.

Nevertheless, while Blue Sky’s output doesn’t bear comparison to a Disney, a Pixar or even a DreamWorks, there’s something about them that I find easy to root for, even if I’m only really a fan of a small percentage of their movies. Even their most middling works have a certain sense of honest effort and ambition about them, even if it didn’t come off: for example, Robots and Epic - both directed by founder Chris Wedge - feel like the work of a team trying to push their movies away from cosy comedy in the direction of larger-scale adventure storytelling, while the Rio movies, for all their generic antics and pratfalls, do at least benefit from the undoubted passion that director Carlos Saldanha tried to bring to his animated realisation of his hometown of Rio de Janeiro. I’ll also continue to celebrate the original Ice Age movie as a charismatic, well-realised children’s road movie, weakened somewhat by its instinct to pull its emotional punches, but gently likeable nevertheless; sure, the series is looking a little worse for wear these days, but at least part of the somewhat misguided instinct to keep churning them out seems to stem from a genuine fondness for the characters. Heck, I’m even inclined to look favourably on Chris Wedge’s ill-fated decision to dabble in live-action with the recent fantasy flop Monster Trucks; after all, the jump from directing animation to live-action is a tricky manoeuvre that even Pixar veterans like Andrew Stanton (John Carter) and Brad Bird (Tomorrowland) have struggled to execute smoothly, and the fact he attempted it at all feels indicative of his studio’s instinct to try their best to expand their horizons, even if their reach sometimes exceeds their grasp.

Besides, it’s not as though their efforts so far have gone totally unrewarded. The third and fourth Ice Age movies scored record-breaking box office results outside the US, while there have also been a handful of notable successes in critical terms - most prominently, Horton Hears a Who! and The Peanuts Movie, the two adaptations of classic American children’s literature directed for the studio by Steve Martino. I suppose you can put a negative spin on the fact that Blue Sky’s two best-reviewed movies were the ones based on iconic source material - as I’ve noted, the films do feel a little bit like stylistic outliers, rather than organic expressions of the studio’s strengths - but let’s not kid ourselves that working from a beloved source text isn’t a double-edged sword. Blue Sky’s rivals at Illumination proved that much in their botching of Dr Seuss’ The Lorax, as have Sony Pictures Animation with their repeated crimes against the Smurfs, and these kinds of examples provide a better context to appreciate Blue Sky’s sensitive, respectful treatments of Seuss and Charles Schulz as the laudable achievements they are. If anything, it may actually be MORE impressive that a studio that’s often had difficulty finding a strong voice with their own material have been able to twice go toe-to-toe with genuine giants of American culture and emerge not only without embarrassing themselves, but arguably having added something to the legacies of the respective properties.

CELEBRATING... GENUINE INNOVATION IN CG ANIMATION

Of course, adding something to a familiar mix is part and parcel of the adaptation process, but the challenge for any studio is to make sure that anything they add works to enrich the material they’re working with, rather than diluting it. In the case of The Peanuts Movie - a lavish computer-generated 3D film based on a newspaper strip with a famously sketchy, spartan aesthetic - it was clear from the outset that the risk of over-egging the pudding was going to be high, and that getting the look right would require a creative, bespoke approach. Still, it’s hard to overstate just how bracingly, strikingly fresh the finalised aesthetic of The Peanuts Movie feels, to the degree where it represents more than just a new paradigm for Schulz’s characters, but instead feels like a genuinely exciting step forward for the medium of CG animation in general.

Now, I’m certainly not one of those old-school puritans who’ll claim that 2D cel animation is somehow a better, purer medium than modern CGI, but I do share the common concern that mainstream animated features have become a little bit aesthetically samey since computers took over as the primary tools. There’s been a tendency to follow a sort of informal Pixar-esque playbook when it comes to stylisation and movement, and it’s only been relatively recently that studios like Disney, Illumination and Sony have tried to bring back some of that old-school 2D squash-and-stretch, giving them more scope to diversify. No doubt, we’re starting to see a spirit of visual experimentation return to the medium - the recent stylisation of movies like Minions, Cloudy With a Chance of Meatballs, Hotel Transylvania and Storks are testament to that - but even so, it feels like there’s a limit to how far studios are willing to push things on a feature film. Sure, Disney and Pixar will do gorgeous, eye-popping visual style experiments in short movies like Paperman, Inner Workings and Piper, but when it comes to the big movies, a more conservative house style invariably reasserts itself.

With the exception of a greater-than-average emphasis on physicality, Blue Sky’s typical playbook hasn’t really differed that much from their peers, which is partly why their approach to adapting Seuss and Schulz - two artists with immutable, iconic art styles of their own - have stood out so much. Their visual work on Horton Hears a Who! was groundbreaking in its own way - it was, after all, the first CG adaptation of Dr Seuss, and the result captured the eccentric impossibilities and flourishes of the source material much better than Illumination managed four years with The Lorax - yet The Peanuts Movie presented a whole new level of challenge. Where Seuss’s worlds exploded off the page with colour and life and elastic movement, Schulz’s were the very model of scribbled understatement, often eschewing backgrounds completely to preserve an expressive but essentially sparse minimalism. Seuss’s characters invited 3D interpretation with their expressive curves and body language; the Peanuts cast, by contrast, make no three-dimensional sense at all, existing only as a limited series of anatomically inconsistent stock poses and impressionist linework that breaks down the moment volume is added. It’s not that Charlie Brown, Snoopy and co are totally resistant to animation - after all, the Peanuts legacy of animated specials and movies is almost as treasured as the comic strip itself - but it’s still worth noting that the Bill Melendez/Lee Mendelson-produced cartoons succeeded mostly by committing fully to the static, spare, rigidly two-dimensional look of Schulz’s comic art, a far cry from the hyper-malleable Chuck Jones/Friz Freleng-produced style of the most famous Seuss adaptations.

Perhaps realising that Schulz cannot be made to adapt to 3D, Blue Sky went the opposite route: making 3D adapt to Schulz. The results are honestly startling to behold - a richly colourful, textured, fluidly dynamic world, populated by low-framerate characters who pop and spasm and glide along 2D planes, creating a visual experience that’s halfway between stop-motion and Paper Mario. It’s an experiment in style that breaks all the established rules and feels quite unlike anything that’s been done in CGI animation on this scale - with the possible exception of The Lego Movie - and it absolutely 100% works in a way that no other visual approach could have done for this particular property. Each moment somehow manages to ride the line of contradiction between comforting familiarity and virtuoso innovation; I’m still scratching my head, for example, about how Blue Sky managed to so perfectly translate Linus’s hair - a series of wavy lines that make no anatomical sense - into meticulously rendered 3D, or how the extended Red Baron fantasy sequences are able to keep Snoopy snapping between jerky staccato keyframes while the world around him spins and revolves with complete fluidity. Snoopy “speaks”, as ever, with nonverbal vocalisations provided by the late Bill Melendez, director of so many classic Peanuts animations; the use of his archived performance in this way is a sweet tribute to the man, but one that hardly seems necessary when the entire movie is essentially a $100 million love letter to his signature style.

I do wonder how Melendez would’ve reacted to seeing his work aggrandised in such a lavish fashion, because it’s not as though those films were designed to be historic touchstones; indeed, much of the stripped-back nature of those early Peanuts animations owed as much to budgetary constraints and tight production cycles as they did to stylistic bravery. Melendez’s visuals emerged as they did out of necessity; it’s an odd quirk of fate that his success ended up making it necessary for Blue Sky to take such bold steps to match up with his template so many decades later. Sure, you can argue that The Peanuts Movie is technically experimental because it had to be, but that doesn’t diminish the impressiveness of the final result at all, particularly given how much easier it would have been to make the film look so much worse than this. It’d be nice to see future generations of CG animators pick up the gauntlet that films like this and The Lego Movie have thrown down by daring to be adventurous with the medium and pushing the boundaries of what a 3D movie can look and move like. After all, trailblazing is a defining component of Peanuts’ DNA; if Blue Sky’s movie can be seen as a groundbreaking achievement in years to come, then they’ll really have honoured Schulz and Melendez in the best way possible.

CELEBRATING... THE COURAGE TO BE SMALL

In scaling up the visual palette of the Peanuts universe, Blue Sky overcame a key hurdle in making the dormant series feel worthy of a first full cinematic outing in 35 years, but this wasn’t the only scale-related challenge the makers of The Peanuts Movie faced. There’s always been a perception that transferring a property to the big screen requires a story to match the size of the canvas; in the animation industry, that’s probably more true now than it’s ever been. Looking back at the classic animated movies made prior to around the 1980s and 1990s, it’s striking how many of them are content to tell episodic, rambling shaggy dog stories that prioritise colourful antics and larger-than-life personalities over ambitious narrative, but since then it feels like conventions have shifted. Most of today’s crop of successful animations favour three-act structures, high-stakes adventure stories and screen-filling spectacle - all of which presents an obvious problem for a movie based on a newspaper strip about a mopey prepubescent underachiever and his daydreaming dog.

Of course, this isn’t the first time that Charlie and Snoopy have had to manage a transition to feature-length narrative, but it was always unlikely that Blue Sky would follow too closely in the footsteps of the four previous theatrical efforts that debuted between 1969 and 1980. All four are characterised by the kind of meandering, episodic structure that was popular in the day, which made it easier to assemble scripts from Schulz-devised gag sequences in an essentially modular fashion; the latter three (Snoopy, Come Home from 1972, Race for Your Life, Charlie Brown from 1977 and Bon Voyage, Charlie Brown (and Don't Come Back!!) from 1980) also made their own lives easier by incorporating road trips or journeys into their storylines, which gave audiences the opportunity to see the Peanuts gang in different settings. The first movie, 1969’s A Boy Named Charlie Brown, also features a road trip aspect to its plotline, but in most respects offers the most typical and undiluted Peanuts experience of the four original films; perhaps as a result, it also feels quite aggressively padded, while its limited cast (lacking later additions like Peppermint Patty and Marcie) and intimately dour focus made it a sometimes claustrophobic cinematic experience.

Given The Peanuts Movie’s intention to reintroduce the franchise to modern audiences who may not necessarily be familiar with the original strip’s melancholic sensibilities, the temptation was always going to be to balloon the property outwards into something broad, overinflated and grand in a way that Schulz never was; it’s to be applauded, then, that The Peanuts Movie ends up as that rare CGI animation that tells a small-scale story in a focused manner over 90 minutes, resisting the urge to dilute the purity of its core character-driven comedy material with any of the family adventure elements modern audiences are used to. Even more so than previous feature-length Peanuts movies, this isn’t a film with any kind of high-concept premise; rather than sending Charlie Brown out on any kind of physical quest, The Peanuts Movie is content to offer a simple character portrait, showing us various sides of our protagonist’s personality as he strives to better himself in order to impress his unrequited love, the ever-elusive Little Red-Haired Girl. The resulting film is certainly episodic - each attempt to impress his object of affection sends Charlie Brown into new little mini-storylines that bring different classic characters to the foreground and evoke the stop-start format of Schulz’s strip, even though the content and style feel fresh - but all of the disparate episodes feel unified by the kind of coherent forward momentum and progressive character growth that Bill Melendez’s older movies never really reached for.

Indeed, it’s probably most telling that the film’s sole major concession to conventional cinematic scale - its extended fantasy side-story featuring Snoopy engaging in aerial battles in his imaginary World War I Flying Ace alter-ego - is probably its weakest element. These high-flying action sequences are intelligently conceived, injecting some real visual splendour and scope without intruding on the intimacy of the main story, but they feel overextended and only infrequently connected to the rest of the film in any meaningful way. This would be less of a problem if the Snoopy-centric narrative had effective emotional hooks of its own, but sadly there’s really not much there beyond the Boys’ Own parody trappings; any real investment in Snoopy’s dreamed pursuit of his poodle love interest Fifi is undermined by her very un-Schulz-like drippy damselness, and it becomes hard to avoid feeling that you’re watching an extended distraction from the parts of the movie you’re actually interested in. Of course, it’s arguable that an overindulgent fondness for Snoopy-related flights of fancy drawing attention away from the more grounded, meaningful exploits of Charlie Brown and friends is actually a fair reflection of the Peanuts franchise in its latter years, showing that Blue Sky were faithful to Schulz to a fault, but I wouldn’t like to focus too much on a minor misstep in a film that’s intelligent and committed about its approach to small-canvas storytelling in a way you don’t often see from mainstream animated films on the big screen.

CELEBRATING... LETTING THE ULTIMATE UNDERDOG HAVE HIS DAY

All of these achievements would count for very little, though, if Blue Sky’s movie wasn’t able to adequately capture the intellect and essence of Schulz’s work, a task that seems simultaneously simple and impossible. For such a sprawling franchise, Peanuts has proven remarkably resilient to tampering, meddling or ruination, with each incarnation - whether in print or in animation - remaining stylistically and tonally consistent, thanks to the strict control Schulz and his fastidious estate have kept over the creative direction of the series. On the one hand, this is a blessing of sorts for future stewards of the franchise, as it gives them a clear playbook to work from when producing new material; on the other hand, the unyielding strictness of that formula hints heavily at a certain brittleness to the Peanuts template, suggesting to would-be reinventors that it would take only a small misapplication of ambition to irrevocably damage the essential Schulz-ness of the property and see the result crumble to dust. This has certainly proven the case with Schulz’s contemporary Dr Seuss, one of few American children’s literature writers with a comparable standing to the Peanuts creator, and an artist whose literate, lyrical and contemplative work has proven eminently easy to ruin by misguided adapters who tried and failed to put their own spin on his classic material.

There’s no guesswork involved in saying these concerns were of paramount importance to the Schulz estate when prepping The Peanuts Movie - director Steve Martino was selected specifically on the strength of his faithful adaptation of Seuss’ Horton Hears a Who!, and the film’s screenplay was co-written by Schulz’s son Craig and grandson Bryan - but even taking a cautious approach, there are challenges to adapting Schulz for mainstream feature animation that surpass even those posed by Seuss’ politically-charged poetry. For all his vaulting thematic ambition, Seuss routinely founded his work on a bedrock of visual whimsy and adventurous, primary-colours mayhem, acting as a spoonful of sugar for the intellectual medicine he administered. Schulz, on the other hand, preferred to serve up his sobering, melancholic life lessons neat and unadulterated, with the static suburban backdrops and simply-rendered characters providing a fairly direct vessel for the strip’s cerebral, poignant or downbeat musings. The cartoonist’s willingness to honestly embrace life’s cruel indignities, the callousness of human nature and the feeling of unfulfilment that defines so much of regular existence is perhaps the defining element of his work and the foundational principle that couldn’t be removed without denying Charlie Brown his soul - but it’s also something that might have felt incompatible with the needs and expectations of a big studio movie in the modern era, particularly without being able to use the surface-level aesthetic pleasure that a Seuss adaptation provides as a crutch.

I’ve already addressed the impressive way The Peanuts Movie was able to make up the deficit on visual splendour and split the difference in terms of the story’s sense of scale, but the most laudable aspect of the film is the sure-footed navigation of the tonal tightrope it had to tread, deftly balancing the demands of the material against the needs of a modern audience, which are honestly just as important. Schulz may have been a visionary, but his work didn’t exist in a vacuum; the sometime brutal nature of his emotional outlook was at least in part a reaction to the somewhat sanitised children’s media landscape that existed around him at the time, and his work acted as an antidote that was perhaps more necessary then than it is now. That’s not to say the medicinal qualities of Schulz’s psychological insights don’t still have validity, but to put it bluntly I don’t think children lack reminders in today’s social landscape that the world can be a dark, daunting and depressing place, and it feels like Martino and his team realised that when trying to find the centre of their script. Thus, The Peanuts Movie takes the sharp and sometimes bitter flavour of classic Schulz and filters it, finding notes of sweetness implicit in the Peanuts recipe and making them more explicit, creating a gentler blend that goes down smoother while still feeling like it’s drawn from the original source.

The core of this delicate work of adaptation is the film’s Charlie Brown version 2.0 - still fundamentally the same unlucky totem of self-doubt and doomed ambition he’s always been, but with the permeating air of accepted defeat diminished somewhat. This Charlie Brown (voiced by Stranger Things’ Noah Schnapp) shares the shortcomings of his predecessors, but wears them better, stands a little taller and feels less vulnerable to the slings and arrows that life - and ill-wishers like Lucy Van Pelt - throw at him. Certainly, he still thinks of himself as an “insecure, wishy-washy failure”, but his determination to become more than that shines through, with even his trademark “good grief” sometimes accompanied by a wry smile that demonstrates a level of perspective that previous incarnations of the character didn’t possess. Blue Sky’s Charlie Brown is, in short, a tryer - a facet of the character that always existed, but was never really foregrounded in quite the way The Peanuts Movie does. In the words of Martino:

“Here’s where I lean thematically. I want to go through this journey. … Charlie Brown is that guy who, in the face of repeated failure, picks himself back up and tries again. That’s no small task. I have kids who aspire to be something big and great. … a star football player or on Broadway. I think what Charlie Brown is - what I hope to show in this film - is the everyday qualities of perseverance… to pick yourself back up with a positive attitude - that’s every bit as heroic … as having a star on the Walk of Fame or being a star on Broadway. That’s the story’s core.”

It’s possible to argue that leavening the sometimes crippling depression in Charlie Brown’s soul robs him of some of his uniqueness, but it’s also not as though it’s a complete departure from Schulz’s presentation of him, either. Writer Christopher Caldwell, in a famous 2000 essay on the complex cultural legacy of the Peanuts strip, aptly described its star as a character who remains “optimistic enough to think he can earn a sense of self-worth”, rather than rolling over and accepting the status that his endless failures would seem to bestow upon him. Even at his most downbeat and “Charlie-Browniest”, he’s always been a tryer, someone with enough drive to stand up and be counted that he keeps coming back to manage and lead his hopeless baseball team to defeat year after year; someone with the determination to try fruitlessly again and again to get his kite in the air and out of the trees; someone with enough lingering misplaced faith in Lucy’s human decency to keep believing that this time she’ll let him kick that football, no matter how logical the argument for giving up might be.

Indeed, Charlie Brown’s dogged determination to make contact with that damn ball was enough to thaw the heart of Schulz himself, his creator and most committed tormentor - having once claimed that allowing his put-upon protagonist to ever kick the ball would be a “terrible disservice to him”, the act of signing off his final ever Peanuts strip prompted a change of heart and a tearful confession:

“All of a sudden I thought, 'You know, that poor, poor kid, he never even got to kick the football. What a dirty trick - he never had a chance to kick the football.”

If that comment - made in December 1999, barely two months before his death - represented Schulz’s sincere desire for clemency for the character he had doomed to a 50-year losing streak, then The Peanuts Movie can be considered the fulfilment of a dying wish. No, Charlie Brown still doesn’t get to kick the football, but he receives something a lot more meaningful - a long-awaited conversation with the Little Red-Haired Girl, realised on screen as a fully verbalised character for the first time, who provides Charlie Brown with a gentle but quietly overwhelming affirmation of his value and qualities as a human being. In dramatic terms, it’s a small-scale end to a low-key story; in emotional terms, it’s an moment of enormous catharsis, particularly in the context of the franchise as a whole. It’s in this moment that Martino’s film shows its thematic hand - the celebration of tryers the world over, a statement that you don’t need to accomplish epic feats to be a good person, that persevering, giving your all and maintaining your morality and compassion in the face of setbacks is its own kind of heroism. The impact feels even greater on a character level, though; after decades of Sisyphean struggle and disappointment, the ending of The Peanuts Movie is an act of beatific mercy for Charlie Brown, placing a warm arm around the shoulders of one of American culture’s most undeservedly downtrodden characters and telling him he is worth far more than the sum of his failures, that his essential goodness and honesty did not go unnoticed, and that he is deserving of admiration - not for being a sporting champion or winning a prize, but for having the strength to hold on to the best parts of himself even when the entire world seems to reject everything he is.

Maybe that isn’t how your grandfather’s Peanuts worked, and maybe it isn’t how Bryan Schulz’s grandfather’s Peanuts worked either, but it would take a hard-hearted, inflexible critic to claim that any of The Peanuts Movie’s adjustments to the classic formula are damaging to the soul of the property, particularly when the intent behind the changes feels so pure. The flaws and foibles of the characters are preserved intact, as is the punishingly fickle nature of the world’s morality; however, in tipping the bittersweet balance away from bitterness towards sweetness, Martino’s movie escapes the accusation of mere imitation and emerges as a genuine work of multifaceted adaptation, simultaneously acting as a tribute, a response to and a modernisation of Charles Schulz’s canon. The Peanuts Movie is clearly designed to work as an audience’s first exposure to Peanuts, but it works equally well if treated as an ultimate conclusion, providing an emotional closure to the epic Charlie Brown morality play that Schulz himself never provided, but that feels consistent with the core of the lessons he always tried to teach.

In reality, it’s unlikely Peanuts will ever be truly over - indeed, a new French-animated TV series based on the comics aired just last year - but there’s still something warmly comforting about drawing a rough-edged line under The Peanuts Movie, letting Charlie Brown live on in a moment of understated triumph 65 years in the making, remembered not for his failings but by his embodiment of the undersung heroism of simply getting back up and trying again. It’s not easy to make a meaningful contribution to the legacy of a character and property that’s already achieved legendary status on a global scale, but with The Peanuts Movie, the perennially undervalued Blue Sky gave good ol’ Charlie Brown a send-off that a spiritually-minded humanist like Charles Schulz would have been proud of - and in my book, that makes them heroes, too.

#peanuts#peanutsmovie#charles schulz#charles m. schulz#charlie brown#peppermint patty#lucy van pelt#linus van pelt#snoopy#woodstock#blue sky#blue sky studios#animation#film analysis#movies#movie critique#long post

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

In this essay I will

After obsessively researching the history of Cartoon Network, broadcast TV, and the production of Adventure Time and other shows, I've come to the conclusion that Cartoon Network is run by Slimer, the green slimy ghost from Ghostbusters (1984).

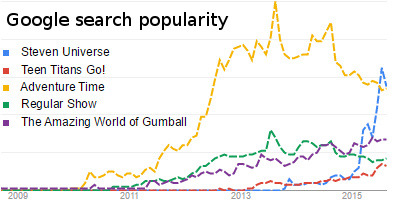

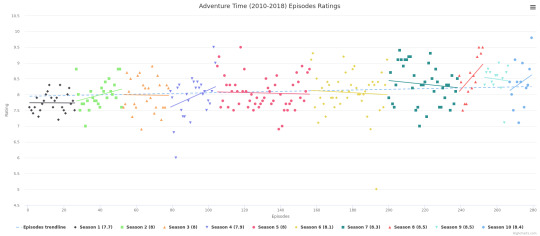

When Adventure Time made its debut in 2010, it was an smash hit. It more than doubled 2009 viewership ratings in its time slot, and more than tripled ratings in the 9-14 age group. Its popularity only increased from there, with ratings steadily growing for the first 5 seasons. The show received strong reviews from critics, got dozens of awards, and amassed a large and devoted fan base. Comics and other products were successfully marketed alongside the show. For years, AT was consistently CN's top franchise.

Then, in 2014, after five and a half seasons of rising ratings, viewership fell. Season 7 ratings were a third of those of season 6. By season 9, AT’s ratings were a fifth of what they were at its peak. In 2016, it was announced that the show, CN's most popular show just two years prior, was cancelled.

Now, if the show had actually gotten worse in its second half, as many long-running shows do, this decline would be understandable. However, most fans agree that AT only got better with time after season 6. Furthermore, the show received consistent praise from critics throughout seasons 6-10. It earned six of its eight Primetime Emmy Awards after 2014.

So what happened?

In November of 2014, halfway through season 6, CN made several changes to AT's broadcasting schedule. The weekly release schedule was abandoned, and new episodes were released in sporadic week-long bursts, with gaps of weeks or even months between new releases. Advertising for new episodes ceased. Reruns were never aired. These decisions disrupted most fans’ viewing schedules, and left many fans of the show simply unable to watch new episodes, or know when new episodes were released. Some even wondered if the show had been quietly taken off the air.

One has to ask why CN would do this to their biggest franchise.

I believe that it was ultimately a bad decision, for reasons I’ll get to later. However, to understand why the decision was made, we have to first understand the current state of television.

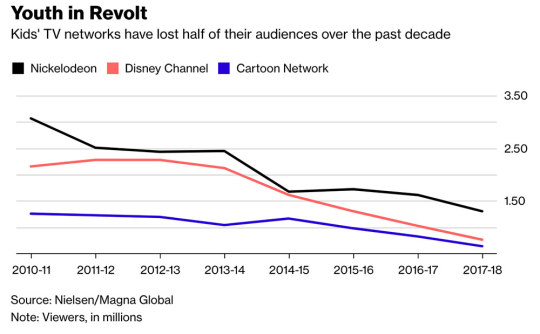

Simply put, the advent of the internet has led to indomitable competitors for traditional broadcast TV. The meteoric rise of Netflix, Hulu, Amazon Prime Video, Youtube, and others have all contributed to what some journalists describe as a “freefall” in ratings for channels including Cartoon Network, Nickelodeon, and the Disney Channel. For most people today, it’s more convenient and cheaper to watch your shows on literally anything but a TV.

Another part of the answer is that every show is an investment with a potential risk and reward. Risk and reward have to be balanced differently depending on the economic environment of the time. In a world where TV is being rapidly eclipsed by internet-based streaming services, CN perceived AT as too “risky” compared to "safer" shows. Even if CN was doomed, its life could be prolonged by sticking to tried and tested formulas.

Several things made AT a risky venture from the start. The show broke the status quo in multiple ways, with non-traditional story elements, devices, setting, tone, character development, and subject matter. Also, the show's wide appeal and arc-driven story clashed with CN's focus on the 7-15 year old demographic and non-serialized content. Ironically, the things which made AT “risky” were the same things which made it popular.

Then why did CN take up AT in the first place? In 2010, CN was in decline after a series of popular shows in the 2000s ended, and several other late-2000s shows had failed to take off. Ratings were falling, so they wanted something good to bring the viewers back. Enter Adventure Time.

CN saw AT from the start as a risky venture which could let it escape its late 2000s ratings slump. CN execs never expected such a non-traditional show to become so popular. Nobody had any idea if the success of the show would continue; nobody had ever done this before. This made it a risky venture (in the eyes of network CN executives). Episodes took 8-9 months to produce, and entire seasons were worked on concurrently, which meant that if viewership suddenly fell through, the money that was poured into production would go nowhere. Now, with the accelerating decline of television, CN felt that it needed to return to cartoons built on a more reliable model.

In 2014, after a small dip in viewership from season 5 to season 6, and having reaped an adequate rebound in channel viewership thanks to AT, CN adopted a new strategy, in which AT and several more nontraditional shows were pushed to the wayside in favor of new shows based on a more traditional model. Many CN shows, including Steven Universe and Regular Show, began to receive a similar sporadic broadcast treatment shortly after AT.

If CN didn’t want to lose money producing shows that it believed catered to unreliable audiences, why did it continue to produce them at all, only to air them so sporadically? Apparently, the internet is again the answer.

The idea was that shows which were especially popular on the internet could be treated differently from other shows. Through the internet, fans would find out about airing times from official announcements and from other fans. This would mean three things: 1) The airing schedule could be more inconsistent, since fans wouldn’t be reliant upon a consistent schedule to know when the show airs; 2) Promotions for the show could be reduced, since fans would find out about airing times through other means, and the show would promote itself via the internet; 3) Re-runs of the show could be reduced, since fans would mostly watch only the first run.

All three of these things would save money, something any company is always keen on doing. This lead to the idea of releasing new episodes of certain shows in sporadic “bomb weeks”. Hypothetically, fans would tune in for their shows and tune out, and the rest of the channel could be dedicated to programming for audiences who still play by the rules of old TV. An additional hypothetical benefit of this strategy was that releasing multiple episodes in quick succession would result in a brief spike in online popularity of the cartoon, leading more people to find out about it, more so than a regular release schedule would. (Like how the intermittent gonging of a grandfather clock is much more noticeable than the regular ticking of a second hand.)

If the internet worked like it does in the imagination of a middle-aged Cartoon Network executive, then maybe everything would’ve worked out, and CN’s ratings wouldn’t be in freefall. The reality is that many of those fans who reside on the internet simply don’t tune in; many don’t even have TV subscriptions. This meant that the “bomb week” strategy actually led to a decline in the popularity of shows the network perceived as “risky” to begin with, leading to the cancellation or early conclusion of many shows, including Adventure Time, Regular Show, Clarence, and others.

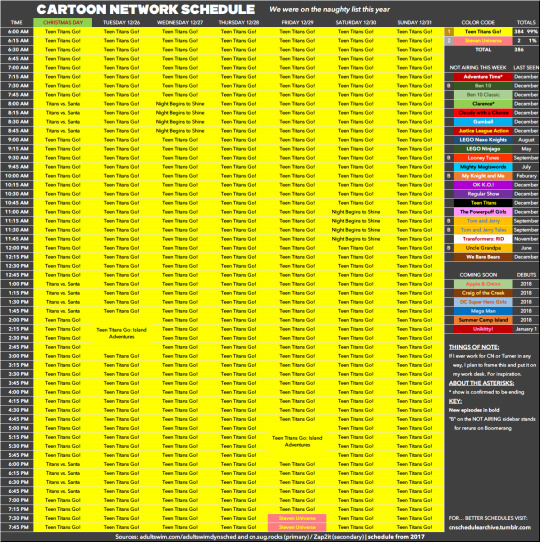

Cartoons like The Amazing World of Gumball and Teen Titans Go, which fit the model of a “safe” cartoon and appealed to younger (and ostensibly-but-not-really less internet-suave) audiences were given more airtime and more advertisement. By late 2014, Gumball and TTG alone occupied half of CN's airtime, with the other half being mostly reruns and a few other new shows.

Now, most of the channel’s content is mostly aimed at a younger audience, with looser story progressions which allow for out-of-order viewing of episodes and reruns. Squeezed into weekends and evenings here and there are shows whose fans reside on the internet, who (ostensibly-but-not-really) learn about airing times on the internet and tune in just to watch their shows.

In other words, the way in which CN had treated its audience and its shows has only led to a further decline in overall channel ratings. Remember that time that CN aired a week of only TTG episodes, with 2 episodes of Steven Universe at random times? This is the kind of thing that only seems like a good decision if you have no idea how the internet works or what kids want from a TV channel.

From a financial viewpoint, CN’s decision made some degree of sense. Television has been on the decline for decades, and is even more so now with the rise of Netflix and other alternative platforms. Focusing resources on shows which are more likely to give returns on those investments in years to come is a logical decision, even if it’s a sucky one from the perspective of a fan. However, I think that it was still a bad one. The move to drop anything which was too strange or too new was in itself a risk which relied on the idea that cartoons would forever be shown on TV, and that “slow and steady wins the race”, so risks aren’t worth taking. TV will inevitably die. If anything, CN could’ve licensed out some of its IPs to producers like Netflix and the like. I don’t have any conclusion to this thread. There is no really good way forward for CN, and cable TV in general, short of a miracle of some sort.

To counter some counterarguments...

Many would say that every show has to end, and I agree. I only disagree with the manner in which CN treated AT in the second half of its run. Despite consistently positive reviews, CN cut the show’s air time, which caused viewership ratings to drop. This drop in ratings then directly led to an early cancellation in 2016. The production team originally had an entire extra season planned, and at some point had thoughts of producing a movie; these ideas had to be thrown out and cut down to fit within CN’s constraints and mandates.

Some would say that the show actually got worse as it progressed. This is a matter of personal opinion, just as is my opinion that it got better. The general opinion, as shown by polls of the fanbase, is that the quality of the show was at the very least consistent throughout all ten seasons.

Some might counter-argue that the show was cancelled due to low ratings. This is actually something I agree with. However, the low ratings were caused by CN’s dramatic changes to AT’s airing schedule.

Some might say that creator Pendleton Ward stepping down as showrunner mid-season 5 led to a decline in AT’s quality and therefore popularity. While I agree that season 5 was something of a high point in the show’s quality, and season 6 is a bit of a low point, the quality during and after Ward’s tenure as showrunner was mostly the same. I do think that Ward’s stepping down may be related to the timing of CN’s decision to dump the show. The very first season in which Adam Muto was the sole showrunner, season 6, was the very first season in which the season premiere had lower ratings than the last season’s premiere. From the perspective of a CN executive trying to save a channel in a dying industry, this is a red flag.

...

tl;dr

Cable and broadcast TV is dying, Adventure Time was a casualty in its ongoing death throes

#adventure time#my post#a REALLY LONG ASS POST#which i spent all of like a full day researching and writing#for no reason other than to vent a little bit#really wish that CN had just licensed the IP to Netflix or something#Netflix would've just funded the same crew on that fat Netflix payroll and with fewer constraints and less censorship#I would have watched the fuck out of adventure time if it was on netflix#but then they only put up the episodes on amazon after release#and then moved them all to hulu#the main channel of new releases still being the CN channel#with a completely random schedule#the crew kept producing a great show even as fans dwindled thanks to CN's dumb moves#great show that couldve been better if CN didnt make several bad decisions

0 notes

Text

Forget heroes: The Marvel Cinematic Universe needs more supervillains

Thanos deserves more than this.

Image: marvel studios

Warning: This post contains MAJOR spoilers for the end of Avengers: Infinity War

Maybe I’m a monster, but the moment I cheered the loudest during Avengers: Infinity War was when all the superheroes disintegrated and the bad guy got his happy ending.

I’m certainly not a fan of genocide (to put it mildly), or even a Thanos groupie. But I do like compelling stories, and a villain-centric arc that refused to let the heroes win was the first time a Marvel movie has surprised me.

SEE ALSO: After ‘Infinity War,’ which ‘Avengers 4’ heroes will lead the fight?

So what’s the problem? Well, the ending leaves me itching for a Thanos prequel instead of the next Avengers or even Captain Marvel — which will undoubtedly undo this unhappy ending. And the knowledge that we’ll probably never get that prequel is why the Marvel Cinematic Universe is starting to lose me.

Every two-bit comic book fan will tell you heroes are only as great as their villains. Everyone, it seems, except for the folks at Marvel Studios.

I’m not the first to point out Marvel’s “villain problem,” or how evil characters tend to be disposable onscreen. Many had high hopes that the introduction of Thanos would fix this problem, but he’s only shined a spotlight on it. Marvel’s villain problem runs deep, requiring a total shift in the MCU franchise formula.

But it won’t be fixed until Marvel actually admits it’s a problem. Head of studio Kevin Feige told io9 that he recognizes the issue with their villains — yet he feels pretty OK about it. “It always starts with what serves the story the most and what serves the hero the most,” he said.

I could do with getting rid of, like, two-thirds of these characters.

Image: marvel studios

But by failing to see how villains are as integral as heroes, the MCU fundamentally misunderstands what makes a good superhero story.

At first, the MCU got away with wasting great superheroes on forgettable villains who were plot devices disguised as characters. But Avengers: Infinity War showed how short-sighted that was. And it ain’t gonna cut it anymore.

SEE ALSO: What happens in the end credits of ‘Avengers: Infinity War’

I’m tired of paint-by-numbers movies introducing hordes of new bad guys that the hero can Hulk-smash until the next round and round and around we go, ad infinitum. Infinity War’s ending was powerful because it finally broke from that cycle … until the end credits, at which point Nick Fury reminds us it’ll be business as usual soon enough.

What’s next for the MCU once it wraps on the biggest bad’s inevitable defeat in Avengers 4? I hope investing in villains is a top priority. From the looks of Venom, it just might be (though don’t put all your eggs in that basket).

Once the Infinity Gauntlet conflict ends, villains will be key to keeping audiences engaged in this increasingly expansive crossover machine. Here’s why, and how.

Villains need their own arcs, developed over multiple movies

The first step is to invest time and effort into establishing villains who evolve throughout the franchise. Marvel was so careful about slowly introducing and incorporating its heroes into the larger MCU. Why don’t villains get half as much thought?

I’m legitimately crying.

Image: marvel studios

This shift toward villains would set the stage for more meaningful conflicts, and allow for experimentation with the kind of stories Marvel tells. Why not bring Ryan Coogler and Michael B. Jordan back for a prequel? Or zoom in on Thanos and Gamora’s backstory?

There’s a reason Loki was crowned “best Marvel villain” for so long. It’s because the first Thor movie was as much his origin story as Thor’s. Loki’s reappearances across the franchise made us as attached to him as we were to any Avenger.

Then there’s Captain America: Winter Soldier and Civil War, which succeeded because the original Captain America established the foundation of Bucky’s character — and then twisted it and his relationship to Cap in a gut-wrenching way.

SEE ALSO: Jeff Goldblum picks his Avengers champion (and it’s not Thor)

And don’t forget Erik Killmonger, who captivated our hearts and minds in about 30 minutes of screen time. Black Panther started with Killmonger, as J’Bou tells his son the story of Wakanda, leading to an entire opening scene establishing Erik’s motivations.

Thanos had the best Infinity War arc, but it was still wasted

Sure, Thanos was better than, say, Ultron.

I was really hoping Thanos would kill Tony Stark.

Image: Marvel Studios

But many comic book fans felt the movie squandered his story. Our own Adam Rosenberg wrote an explainer on the character’s comic book iteration, showing moviegoers just how many missed opportunities there were in Infinity War. Like how “the sight of a rough-skinned, misshapen Baby Thanos was too much for his mother to bear. It drove her instantly mad, and she tried to kill her newborn.”

It’s a detail that would have given much more depth to his and Gamora’s story.

For general audiences, Thanos came across as, at first, laughable. So much so that Peter Quill feels the need to speak roast Thanos, almost as if the movie anticipated the criticism. Marvel probably did anticipate it, because despite 10 years and 19 movies of carefully fitting superheroes into the Infinity War puzzle, it’s never really been about the villain. When the time came, they were like, “Shit — no one even knows why this big dumb purple gummy bear even matters.”

SEE ALSO: Thanos isn’t as lame as the MCU has made him seem

Thanos was basically relegated to after-credits scenes for 10 years, only being more prominently featured in Guardians of the Galaxy Vol 1. as a disembodied giant stone monster.

Marvel’s run out of heroes — but there are plenty of great villains left

Marvel’s done such a good job of establishing a wide array of heroes that it’s basically run out of top tier IP for more franchises. Ant-Man should be indication enough that we’re scraping the bottom of the barrel, and it only gets Hawkeye levels of mediocre from here.

You know what Marvel Studios hasn’t capitalized on? Its fantastic villain-centric comics.

We’ve already mentioned the wasted material of Thanos Rising. But in the comicverse, there’s also a whole run after Civil War where Green Goblin takes control of S.H.I.E.L.D. and assembles a “Dark Avengers,” re-appropriating our favorite hero costumes as villains: Bullseye becomes Daredevil and Venom takes over for Spider-Man. That’s just two relevant examples.

You can get rid of all of these except Spidey and the big dude.

Image: marvel studios

Fix Marvel’s arms race for bigger, badder threats with better villains

Ever since the first Avengers, Marvel’s been chasing bigger catastrophes than the attack on New York — but that’s the wrong way to go about it.

The result is a franchise stuck in a disaster-porn arms race. The cost of this increasingly enormous and ridiculous scale is personal stakes (and apartment buildings). Infinity War kept needing to remind us that the risk of Thanos winning was universal genocide, because we’re that desensitized to world-ending threats.

Spider-Man: Homecoming, on the other hand, is a great example of how villains can ground the whole story, introducing personal stakes on a smaller scale. Yes, that’s kinda Spidey’s thing, while the Avengers deal with universe-ending stuff. But actually, Captain America: Winter Soldier, Civil War, Black Panther, and even Logan all took similar approaches to villains and scale.

SEE ALSO: One Doctor Strange line from ‘Infinity War’ basically sets up ‘Avengers 4’

We live in the age of the anti-hero

Just look at some of the biggest pop culture phenomenons over the past few years: Breaking Bad, Dexter, Mad Men. Or, if you want to go closer to home, Marvel’s own Jessica Jones or Deadpool.

No one is wholly good or wholly bad. That’s why we adore Game of Thrones, with its heroes who commit villainous act and its villains who have undeniable humanity. Blurring the lines between good and evil is the point of George R.R. Martin’s series, which deconstructs the common fantasy genre trope.

I need about 100x more of this.

Image: marvel studios

Marvel movies almost always fail at making even the heroes relatable. Save for Black Panther, Marvel stories are usually irrelevant to the real world. But it doesn’t have to be that way. Superheroes inherently engage with our society’s ideals, morals, and struggle to be good. Shouldn’t Marvel reflect how difficult that question is to answer?

Which reminds me…

This sanctimonious heroic bullshit is getting old

Show of hands: How many times did you yell at the heroes of Infinity War for repeatedly losing stone after stone to Thanos because of an aggressively simple-minded and selfish moral compass?

Yes, I know Cap: “We don’t trade lives.” That’s the summary of this entire movie’s conflict. Thanos believes in sacrificing half the universe’s population for a greater good, while the Avengers think they shouldn’t have to sacrifice anything at all to save half of the universe’s population.

SEE ALSO: The Marvel Cinematic Universe would be 1,000 times better if EVERY hero rocked facial hair

That’s not only a really narrow definition of heroism, but also astoundingly unsophisticated ethics.

The Avengers could use some lessons from The Good Place, namely the trolley problem. Because the idea of sacrificing one to save the lives of many isn’t a rosy concept, but there’s enough ethical grounds to warrant some debate!

But no. Cap grunts, everyone agrees. Ultimately, we have their moral high horses to thank for saving Vision (not even) at the cost of half a universe full of lives. Hope that clean conscience is worth it!

Avengers’ morality is tired, outdated, and underdeveloped. Sacrifice is part of the superhero job description. Heroes do trade lives. Just ask 9/11 first responders, or other everyday people risking their lives for others. Hell, ask Groot! Or Peter Quill! Even annoyingly uncompromising heroes like Batman are willing to sacrifice reputation and love for the greater good of Gotham.

I’m only watching Avengers 4 if Vision stays dead.

Image: marvel studios

This Care Bear heroism plagues the Marvel franchise, preventing fresh, original storytelling. Black Panther was the first movie in a long time to complicate the Marvel moral ethos. We can’t just keep relying on Cap and Iron Man’s creative differences.

It’ll be increasingly hard for us to care about another two hours of dudes in tights fighting when we know the good guy wins, almost always without consequence. Infinity War dared to break that mold, and we hope Avengers 4 genuinely wrestles with the mistakes the heroes made in it. But I’ll eat my laptop if the Infinity Gauntlet story doesn’t end with most of the heroes being revived.

I’m not arguing the bad guys should take over the MCU. But the MCU needs to let bad guys do what they do best: Force us and our heroes to complicate our understanding of what it means to fight for good.

If it doesn’t, we’re just going to keep getting superhero movies where the good guys win — because that’s how the MCU business model works. And that’s not ultimately very entertaining.

WATCH: Everything you need recapped about the Marvel Cinematic Universe before ‘Avengers: Infinity War’

Read more: https://mashable.com/2018/05/01/avengers-infinity-war-villain-movies-mcu-thanos/

from Viral News HQ https://ift.tt/2wlfurM

via Viral News HQ

0 notes

Text

Blockbusters assemble: can the mega movie exist the digital epoch?

From Star Wars sequels to superhero franchises, blockbusters still regulate the film industry. But with Amazon and Netflix tearing up the release planneds, are they on shaky dirt?

Is the blockbuster in difficulty? On the surface, to intimate such a thing might seem as foolhardy as siding out the incorrect envelope at the most difficult contest of the cinema docket because you were busy tweeting photographs of Emma Stone. This is the blockbuster were talking about. Its Luke Skywalker, Jurassic World, Disney, The Avengers, Batman, Superman, Spider-Man, Pixar. Its the Rock punching his fist through a structure. Its the effects-driven cultural juggernaut that powers the entire film industry. Does it look as if its in trouble?

A glance at the balance sheet for its first year to year would cement the view that the blockbuster is in insulting health. Total gross are higher at this stage than any of the past five years. Logan, the Lego Batman Movie and Kong: Skull Island have already been attracted in big audiences globally. And then theres Beauty and the Beast, a genuine culture phenomenon, currently hastening its room up the all-time higher-rankings. All this and theres still a new Star Wars instalment, another Spider-Man reboot, Wonder Woman, Justice League, Alien: Agreement, Blade Runner 2049, plus sequels of (* deep breath *) Guardians of the Galaxy, Cars, World War Z, Kingsman, Transformers, Fast and the Furious, Planet of the Apes, Despicable Me, Thor and Pirates of the Caribbean still to come. Hardly the signs of a crisis, it would be fair to say.

Dig a bit deeper though and the foundations that blockbusters are built on start to look precariou. Last-place month, Variety published a fib that covered a picture of an manufacture scared to death by its own future, as shopper flavors change with changes in engineering. Increased influence from Netflix and Amazon, those digital-disruption barbarians, has caused the big studios to consider changing the style they secrete movies. The theatrical window, the 90 -day cushion between a films debut in cinema and its liberation on DVD or stream, is set to be reduced to as little as three weeks in an attempt to bolster diminishing residence entertainment marketings. Its a move that service industries sees as necessary, as younger viewers develop more adaptable, portable considering procedures, and certainly many smaller creations have begun to liberate their films on-demand on the same day as in cinemas it was one of the reasons that Shia LaBeoufs Man Down grossed a much-mocked 7 in cinemas.

Ana De Armas and Ryan Gosling in Blade Runner 2049. Photograph: Allstar/ WARNER BROS.

At the same time, investors from China long thought to be Hollywoods saviour have suddenly refrigerated their interest, cancelling major studio bargains as the Chinese box office digests growing sufferings( with domestic ticket sales merely increasing 2.4% in 2016 against a 49% rise its first year before)and the governments crackdown on overseas investment starts to bite. Add to that got a couple of high-profile recent flops Scarlett Johanssons Ghost in the Shell, Matt Damons The Great Wall, the unintentionally creepy Chris Pratt/ Jennifer Lawerence sci-fi Passengers, Jake Gyllenhaals Alien knock-off Life and you have an manufacture thats not as prospering as the blockbuster bluster might suggest.

Hollywoods response to this instability has been to double down, places great importance on blockbusters to the exclusion of just about everything else. In the past few decades the summer blockbuster season has mission-crept its practice well into outpouring, a phenomenon that has been period cultural global warming; this year, Logan was released a merely three days after the Oscars resolved. The arising influence is of a full calendar year of blockbusters, with a small drop-off for Oscars season in January and February and even in that point this year we are continuing insured the secretes of The Lego Batman Movie, The Great Wall, John Wick 2 and the lamentable Monster Trucks.

Meanwhile, the mid-budget movie that hardy perennial that used to help prop up the industry by expenditure relatively little and often paying fortunes( belief Sophies Choice or LA Confidential) has significantly been abandoned by the major studios, its potential profit margins seen as insufficiently high when the cost of things such as sell is factored in. Which isnt to say that mid-budget movies dont subsist, its simply that theyre being made by smaller, independent studios witness Arrival and Get Out for recent successful precedents or most commonly as TV series.( Theres that Netflix, interrupting stuffs again .)

In essence, what this all means for service industries is that its blockbuster or bust. Studios have looked at the altering scenery and decided to react by filling it with superheroes, activity aces and CGI creatures, doing more blockbusters than they used to, but fewer cinemas in total. The old tentpole formula, where a few large-scale films would shelter the mid-range and low-budget material, has significantly been abandoned. The blockbusters are about reducing the films these studios cause down to a minimum, suggest Steven Gaydos, vice-president and executive editor at Variety. They represent nothing but large-hearted bets. You have to keep improving a bigger and more efficient spaceship.

Its a high-risk strategy and one that, in accordance with the arrangements of Disney and their Marvel, Star Wars and Pixar franchises, has brought large-scale reinforces. But this sudden ratcheting up of the stakes means that the cost of flop has already become far more pronounced. Last year Viacom was forced to take a $ 115 m( 92 m) writedown on Monster Trucks, while Sony took a writedown of nearly$ 1bn on their entire cinema disagreement after a faltering couple of years.

Hugh Jackman in Logan. Photo: Allstar/ 20 TH CENTURY FOX

While those losses might be explained away as research results of bad bets on bad cinemas Monster Trucks was infamously based on an idea by an managers five-year-old son they hint at the cataclysm who are able to ensue if a broader, industry-wide trouble were to present itself. Namely, what if the public loses its appetite for the blockbuster?

Its not entirely without precedent: in the late 1950 s, as video threatened to plagiarized a march on cinema, studios responded by croaking large-hearted. Spectacle was seen as the key: westerns, musicals and sword-and-sandal epics reigned. But gatherings soon flourished tired of these hackneyed categories and ticket sales continued to shrink. That experience service industries lived, thanks firstly to the insertion of vitality provided for under the edgy, arty New Hollywood movies, then later with the early blockbusters such as Jaws and Star Wars.