A blog for fans of animation, and fans of reading things some guy wrote

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Audio

Introducing: my new podcast, Serious Disness, with DemonTomatoDave!

Hello, faithful Jehanimation readers! I know there haven’t been many updates on here recently, but hopefully I’m about to make that up to you by unveiling my newest project - Serious Disness, a Disney-focused podcast with my good friend Dave Bulmer, who you may know best as YouTube’s DemonTomatoDave! And if you don’t know him, check him out, he’s a cool dude.

In this podcast, Dave and I will be putting our heads together for some SUPER-SERIOUS analysis of various Disney movies. First up is a detailed deconstruction of the mega-blockbuster Frozen, the biggest animated movie of all time, and the first film I ever wrote about for Jehanimation. When I say detailed, I mean it; this is the first of six parts, edited down from a marathon eight-hour conversation we held over two nights back in 2016. But don’t be daunted; we are goofy folk, so expect plenty of comical meandering and odd detours amongst all the critique and thematic analysis.

These Frozen episodes will be the first in what we’re hoping is a regular series of long-form chats about various Disney movies; our next big undertaking after this initial batch will probably be an examination of the live-action Disney remakes (another familiar topic!), so stay tuned! Feel free to follow us on Twitter (@seriousdisness) for all the latest updates; we’ll hopefully have the podcast up on iTunes soon as well. Can you handle the SERIOUSNESS? And the DISNESS? There’s only one way to find out!

(PS - don’t worry, I will be returning to written blogging in the near future! Truth be told, there hasn’t been a lot that’s caught my attention during the first half of 2017, but I’m sure there’s an article to be written about that in itself. Regardless, expect more from Jehanimation in the months to come, in one format or another!)

#SoundCloud#music#Serious Disness#Podcast#Disney#Frozen#In-depth#animation#walt disney pictures#walt disney#disney animation#anna#elsa#olaf

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Jehanimation Awards: separating the best of 2016′s animated movies from the rest

Between all the political turmoil, the near-relentless stream of high-profile deaths and the release of Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice, it has been widely accepted that 2016 was A Bad Year. As a member of the human race, last year probably was a bit of a disappointment in most respects; look at it as an animation enthusiast, though, and the picture starts to look quite a bit rosier.

In fact, I’m going to go a step farther than that and call 2016 one of the best years for feature animation in recent memory - which is saying a lot given how much the bar has been raised since the 1990s. Since the advent of CGI tore up the rulebook and made it easier for newer studios to compete with Disney on an equal footing, it’s felt like we’ve been constantly on the cusp of a new, more diverse landscape for mainstream animation, allowing a wider range of studios and directors to present wildly different visions in a competitive marketplace, rather than a single company monotonously ruling the roost. Obviously, the conservative and formula-driven nature of the business has meant that potential hasn’t always been realised, but in 2016 we got a glimpse of how that theoretical vision would play out in reality - and it was a pretty exciting thing to behold. I can’t think of many previous years in which so many companies - from the US and elsewhere - were able to produce such a broad spread of high-quality movies for different audiences, resulting in a glut of animated movies occupying the top spots in not only the worldwide box office rankings, but also in lists of the best-reviewed films of the year.

Faced with such an embarrassment of riches, it feels difficult and somewhat reductive to pit them against each other and pick out a small handful as being the best - but that’s just what we do around this time of year anyway, so who am I to argue? Still, my intention here is not to add to the somewhat adversarial sentiments that awards season can sometimes generate; this is simply my personal evaluation of all the new animated movies I got to see in 2016, with my favourites highlighted. Your own mileage will, of course, vary, because such variety is the spice of life; with that said, I’m pretty sure this list is 100% objectively correct, so I’ve no idea why you’d disagree.

Immense thanks go to the wonderful Jamie Carr for the header image and icon for this blog! Go follow her on Twitter at @neurodolphin!

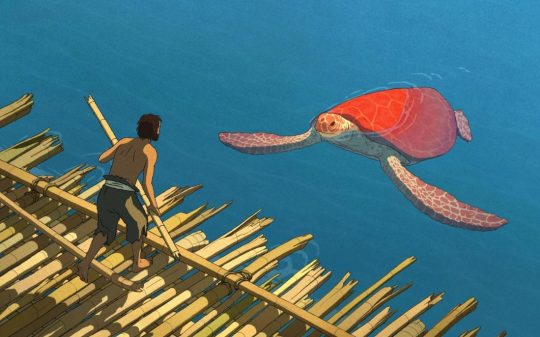

THE NOTABLE OMISSIONS

Before I get into evaluating the best of 2016’s crop, I should probably acknowledge that, contrary to assumption, I am not omniscient, and was therefore unable to see every animated movie that came out last year. There are upsides to this, as it means I missed out on having to watch bargain-bin garbage like Norm of the North or Robinson Crusoe (aka The Wild Life), and was able to judiciously pass on higher-profile but poorly-reviewed efforts like Blue Sky’s Ice Age: Collision Course and Rainmaker Entertainment’s Ratchet & Clank; unfortunately, it also meant not getting to see most of the less widely-screened animated movies from overseas, which is a great shame. I haven’t, for example, been able to see The Red Turtle or My Life as a Zucchini - two of the five nominations for this year’s Best Animated Feature Oscar - nor did I catch the well-reviewed French-Canadian production Ballerina (known in the US as Leap!). I also freely confess to being underexposed to anime, meaning I didn’t see anything from Japan this year - with one important exception, which I’ll come to later. I’ll certainly hope to correct some of these oversights at a later date.

THE ALSO-RANS

The following movies are the films that - for one reason or another - didn’t quite connect with me this year. Some are better than others, but to some degree or another I wouldn’t say they succeeded at what they set out to do.

The Angry Birds Movie

This was probably the weakest animated film I saw last year, which - given its essentially functional mediocrity - reflects pretty well on 2016’s lineup as a whole, even though it doesn’t retroactively make The Angry Birds Movie any more impressive.

I’ve already written a complete review of this film, so I don’t want to waste too much additional time on this one, but looking back I do find it striking just how middling this film was, especially when viewed in the context of everything else that came out after it. It remains deeply frustrating that The Angry Birds Movie actually did a lot of the groundwork necessary to produce a better-than-expected adaptation of a plotless physics-based puzzle game - devising a striking look, hiring great actors and laying the foundation for a potentially interesting thematic discussion on the role of anger in a healthy society - before totally squandering that potential on a script that favours lightweight, rambling and puerile comedy over any opportunity to advance the characters or emotional stakes. It’s a film that lazily follows a bog-standard Shrek-lite formula of cheap pop culture gags, toilet humour and sitcom punchlines, seemingly without realising that said playbook is now several years out of date - which, I suppose, is somewhat fitting for a belated spinoff to a mobile app whose popularity peaked about five years ago.

As I say, there are aspects of The Angry Birds Movie that are slightly better than they needed to be - and I’m willing to accept that it’s not easy to reverse-engineer a script that culminates in birds launching themselves into a pig’s castle via catapult - but I feel less charitable towards it in hindsight having since seen DreamWorks’ Trolls, another brand-derived movie that applied infinitely more honest craft and creativity to its subject matter, and achieved exponentially superior results as a consequence. The fact that Angry Birds was able to utilise its stronger brand recognition and well-timed release window to ultimately outgross Trolls on a worldwide basis just emphasises the point that this isn’t a film in need of my charity, or one worth holding up for any reason other than as an example of the kind of lazy work the rest of the industry has long moved beyond.

The Secret Life of Pets

2016 was a banner year for Illumination Entertainment, as the studio not only made the jump to releasing two films within 12 months for the first time ever, but was also able to turn both into bona fide global smash hits without any reliance on their flagship Despicable Me/Minions franchise. The Secret Life of Pets was the more conventional of the two outings, with its higher box office takings showcasing the strength of the Illumination brand as it exists today; however, the film itself also offers an equally sharp insight into the how much room the studio has to grow.

As I alluded to in my recent post about Illumination, there’s a lot to admire in The Secret Life of Pets, and its great success is no mystery to me. It leans heavily on many of the studio’s established strengths, including a flair for kinetic caricature and imaginative physical comedy, and its bright visual style and design work meant it played a significant role in a broader reawakening of the general public’s love affair with talking animal movies. However, it’s also an unintentional showcase of Illumination at its weakest, particularly in its willingness to foreground shallow slapstick over meaningful story development, and its allergic reluctance to challenge the audience emotionally. That the film’s plot is essentially a beat-for-beat pet-oriented remake of the original Toy Story invites comparisons that do not flatter Illumination’s movie, as The Secret Life of Pets is an infinitely shallower film that passes up several golden opportunities to give its characters proper dimension, resulting in an experience that’s basically sweet-natured and inoffensive, but never comes close to making a lasting impression.

With $875 million grossed worldwide, The Secret Life of Pets was undoubtedly one of the year’s biggest success stories, and represents the start of a franchise with considerable potential mileage; however, the series will require a significant injection of depth, pathos and substance if the resulting series is ever going to be able to aspire to anything more than a vehicle for the episodic and rote delivery of middlebrow gags with a bare minimum of investment.

Kubo and the Two Strings

A passion project by Laika Entertainment’s president and CEO (and sadly forgotten rap legend) Travis Knight, Kubo and the Two Strings didn’t do huge business at the box office, but it’s quickly emerged as one of the critical darlings of the year, and a major awards contender. While I love pretty much everything this hugely admirable piece of work represents, I can’t quite bring myself to extend the same feeling to the film itself as a piece of storytelling.

In fact, I’d probably rate Kubo and the Two Strings as one of the bigger disappointments I experienced last year, which is a real bummer, as I have a deep and unbroken fondness for Laika’s work, dating back to their days in their previous incarnation as Will Vinton Studios. Kubo is in most respects their most ambitious film yet, blending their traditional focus on emotional intimacy and dark atmospherics with an epic fantasy sweep. When it works, it’s absolutely magnificent - their stop motion animation and design work has now evolved to the point where it almost looks indistinguishable from CGI at times, and their grasp of subtle melancholy is as peerless - but there’s a shakiness to the story’s fundamentals that I’m unused to seeing from a studio as famed for their attention to detail as Laika are. The tone lurches wildly from tearjerking grimness to flippant buddy comedy and back again; the actual quest narrative is irritatingly coincidence-driven and never more than vaguely explained, giving the audience little scope to share the journey of discovery; and most damagingly, the script doesn’t seem to know what it wants the lead characters of Monkey and Beetle, setting them up as jovially bickering sidekicks before saddling them with dramatically pivotal backstories that feel overly on-the-nose and don’t mesh with their personalities at all. The result is a film to which I gradually lost my emotional connection as it progressed, which is pretty fatal for a story that ends as intimately as this one does.

Add to that some questionable decisions regarding casting - I won’t harp on this too much, but I will say that it’s weird for a film this conscious about authenticity and tone to pass up the benefits that an Asian cast would provide in that regard, and that none of the actual cast give such indelible performances that they couldn’t have been swapped out - and you get a film ranks as my least favourite Laika movie to date. Admittedly, it’s a difficult category in which to compete, but it’s still a shame not to be able to join in the general chorus of appreciation surrounding a film that generally reflects so much of what I love about animation. I still thoroughly appreciate Laika’s work in almost single-handedly propping up the medium of stop-motion through sheer passion and bloody-mindedness, but for me the narrative elements of Kubo and the Two Strings got away from them - and when you’re making a film specifically designed to celebrate the power of storytelling, that creates a hole in the middle of the movie that no amount of technical splendour can fill.

Finding Dory

The top-grossing animated movie of the year, Pixar’s Finding Dory was always going to be a commercial slam-dunk, given the special place its predecessor Finding Nemo holds in the hearts of many; the big question was whether it was going to be able to measure up to the first movie’s legacy in terms of filmmaking. The answer? Ehhh.

That’s certainly not due to a lack of effort, of course; as I’ve touched upon in my previous post concerning this movie, Finding Dory is not a phoned-in sequel, and you can tell that returning director Andrew Stanton has put thought and consideration into how to expand the self-contained story of Finding Nemo outwards in a way that feels organic. The resulting development of the character of Dory - a mentally impaired protagonist seeking to make peace not only with her own past, but also with herself and the way her condition affects her - is rich with emotional pathos and feels like a natural continuation of Finding Nemo’s key themes, as well as forming a meaningful statement on disability in its own right.

Beyond the oasis of that central storyline, however, Finding Dory enters choppier waters. Dory’s journey may be significant in emotional terms, but dramatically it feels small, with the epic, sweeping journey of the first movie swapped for a claustrophobic single-location setting for the majority of the sequel. That reduced sense of scale isn’t helped by the flimsiness of the supporting cast, populated by half-formed ideas like Hank the octopus (who feels like he has a character-defining backstory lying on a cutting room floor somewhere) or one-note gag characters like Destiny, Bailey, Rudder and Fluke (who never come close to being properly developed). Worst of all, Finding Nemo’s protagonist Marlin is purely along for the ride this time, with very little to do other than complain in a way that becomes grating and unentertaining fairly rapidly. The result is a two-hander where one hand is significantly more developed than the other, which - as Nemo himself would tell you - makes it much harder for Finding Dory to swim in the smooth, straight lines you’d expect from a Pixar film.

That said, I’m not sure exactly what I expect from a Pixar film these days. Finding Dory is far from a bad movie, but it’s a pedestrian effort from a studio that seemed to effortlessly maintain a much higher orbit before the turn of the decade. Finding Dory owes a lot of its success to goodwill left over from those peak years, but the lack of love the movie has received on the awards circuit suggests that at least some of that is starting to run dry. There’s a Dory-style lesson to be learned there: old memories aren’t enough to sustain you forever - you have to be able to form new ones, too.

THE RECOMMENDATIONS

The following movies are the films I saw that didn’t quite make my best-of list, but nevertheless worked well enough to make a positive impression. These aren’t the year’s best animated movies - but they are good ones.

Storks

Storks seemed to come and go without anyone really noticing it happened. I myself missed it at the cinema, and catching up with it many months later, I can sort of understand why; it’s a thoroughly odd duck that doesn’t quite fit with any preconceived notion of what an animated feature would look, sound or play like. The aesthetic splits the difference between big-screen polish and Cartoon Network stylisation; the tone wants to be manic, but grounded; flippant, yet also heartfelt; rambling, but wholly plot-driven.

You know what? For all that, I rather enjoyed Storks, although I’m not sure I’d call it a completely functional film. The first animated movie from live-action comedy director Nicholas Stoller (Forgetting Sarah Marshall, Neighbors) is a relentlessly high-energy experience that is inevitably irritating and wearying at times, but feels full of a certain kid-in-a-candy-store enthusiasm for the boundless absurdist possibilities that animation can provide; it is also a movie that understands the importance of having a heart, and keeps it beating in the right place. Ultimately, Storks doesn’t have anything more profound to say than “babies are nice, and finding your family is great”, but it’s sincere about the way it says it, whether that’s through the oddly charming quasi-romantic chemistry between the avian middle manager Junior and scatterbrained teenage orphan Tulip, or through the engaging B-plot of a young boy reconnecting with his workaholic parents as they wait for delivery of a new baby brother. It’s also an understatedly progressive movie in a couple of ways - it’s nice to focus on a mixed-gender comedic pairing where the female member gets to be the zany one for a change, and you even get some pleasantly matter-of-fact representation of LGBT parent couples thrown in towards the end for good measure, albeit in blink-and-you’ll-miss-it fashion.

That said, this is also an incredibly ramshackle piece of work, full of non-sequitur narrative detours and extended joke sequences that don’t really land - antagonist Toady, an obnoxious business-bro pigeon, feels like an out-of-control SNL skit in place of an actual character, for example. That’s a weakness that cuts across many parts of the film, in fact; Stoller gives the script more of a mannered, improvisational feel than is strictly good for it, resulting in a whole lot of gag lines that feel purely like punchlines crafted by a writer, rather than effective expressions of character. Nevertheless, on balance, I’m happy that the revamped Warner Animation Group are using their post-The Lego Movie relaunch to establish a distinct identity for themselves, rather than going down the me-too route of their Quest for Camelot days; I think it’s even better that their chosen identity is one that tries to honour the company’s offbeat Looney Tunes legacy, as that’s a style we don’t see often enough in the modern feature animation landscape. Clearly, we’re going to be getting a lot of Lego spinoffs and sequels that uphold a Phil Lord/Chris Miller-flavoured variation of that approach, but that type of comedy is good for more than just endless Lego movies - and so are Warner Bros. In that respect, I’d like for Storks to be the beginning of a more diversified lineup from Warner Bros, not the end, which is why this imperfect little movie just about edged its way into my recommendations category; the quality isn’t always there, but the right spirit is there in spades.

Kung Fu Panda 3

In another year, Kung Fu Panda 3 would have been a much bigger deal than it ended up being. It was a very good animated movie in a year full of them, a talking animal film coming out just as the genre suddenly became ubiquitous, and a high-quality sequel to a franchise that had probably been away from the big screen a few years too long for audiences to still be invested. Heck, even in China - the market where this US-Chinese co-production was clearly ordained to sweep aside all comers - this belated threequel had its thunder stolen, reigning briefly as the region’s highest-grossing animated movie ever before the breakout success of Disney’s Zootopia took the title away after only one month.

All of that is a bit of a shame, because - as I’ve mentioned - Kung Fu Panda 3 is a very good movie, even if it is unquestionably the weakest instalment in the trilogy. It lacks the energetic freshness of the 2008 original and the impressive emotional scope of 2011’s Kung Fu Panda 2, the bracing darkness of which Kung Fu Panda 3 largely backs away from in favour of something a bit cosier and smaller-scale. In that respect, this is very much the Return of the Jedi of this series, with all that entails - right down to being set in a hidden village of cuddly bears - but none of that makes it anything like a bad film. For one thing, it’s absolutely beautiful to look at - one of the most aesthetically gorgeous pieces of animation I’ve seen for a while, with vivid colours, stylised action, stunning 2D sequences and masterful incorporation of the look of Chinese paintings into its visual style. That respectfulness goes beyond the visual elements, though; the first Kung Fu Panda may have been a watershed movie for DreamWorks in adopting a tone of loving pastiche rather than broad spoof, but the sequels have been so reverential to the genre and culture that inspired them that you almost wish they’d dropped the comedy focus altogether and pivoted the series in the direction of full-on anthropomorphic wuxia adventure, with a tone closer to the How to Train Your Dragon movies.

Still, what we’ve got from Kung Fu Panda is pretty great, thanks not only to their embrace of the excitement and philosophies of martial arts cinema, but also to their commitment to strong characterisation of their key players. Po the panda remains a delightful creation, with Jack Black consistently finding and underplaying the notes of earthy wisdom and spiritual growth in a character who could easily have come across as 100% fanboy goofball, and his relationship with the elderly goose Mr Ping - voiced with wonderful warmth and eccentricity by the brilliant James Hong - remains one of the most oddly affecting father-son relationships in animated cinema. The addition of Po’s birth father Li Shan (Bryan Cranston) to that dynamic in Kung Fu Panda 3 is handled maturely, in a way that celebrates unconventional family structures, and that emotional throughline works in tandem with the spiritual concepts of the story to provide a strong foundation. In truth, there’s not all that much going on beyond that, other than colourful action setpieces - once again the supporting cast, including Po’s brothers-in-arms the Furious Five, are left frustratingly underused and underdeveloped - leaving Kung Fu Panda 3 feeling like the slightest entry in the series; nevertheless, it’s still a satisfying, funny adventure that brings the series to a fitting thematic conclusion. In truth, Kung Fu Panda probably is a series whose time has passed; if that’s the case, I’m glad it got to impart a few more words of wisdom before moving on.

Sing

The second and less conventional of Illumination Entertainment’s 2016 efforts, the musical extravaganza Sing may have been the lower-grossing and slightly less well-reviewed of the two outings, but for my money it outdoes The Secret Life of Pets on every level creatively - to the point where I’m wondering if everyone else saw these two movies the wrong way around.

When I call Sing “unconventional”, I’m not really talking about its approach to genre and storytelling, because frankly it really couldn’t be any more conventional in those respects. This is a big, broad, goofy, follow-your-dreams jukebox musical that garnishes the X Factor/American Idol template with a sprig of Muppets-style save-the-theatre backstage drama - you know, in case the overstuffed ensemble cast didn’t already have enough underdogs to root for. Said ensemble, which includes a shy teen elephant with an angel’s voice, an overworked mother pig with dreams of stardom, a young gorilla seeking to escape a life of crime and a punk rock porcupine breaking away from her controlling jerk boyfriend, is packed to bursting with character arcs that you’ll be able to predict with perfect accuracy the moment they begin - or perhaps even before then, if you’ve seen any of the too-numerous trailers for Sing that essentially summarise the entire story beat for beat.

But when judging a movie like this, it’s important to remember that cliche is not inherently a sin - a familiar recipe can still taste fabulous when the ingredients are prepared with care and attention, and so it proves with Sing, a movie that’s made with infinitely more sincerity and ambition than it’s been given credit for. It feels good to be able to praise an Illumination movie for those qualities, and that’s where the “unconventional” aspect comes into play, as this is a film that has clearly benefited from the studio searching outside its usual creative talent pool and taking a punt on Garth Jennings, the likeable British filmmaker responsible for The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy and Son of Rambow. A prolific director of music videos, Jennings is clearly someone with a passion for music that saturates Sing, turning what could have been an empty exercise in celebrity animal karaoke into a genuine celebration of the restorative power of music. That earnestness also bleeds into the characterisation, which - for as formulaic as it unarguably is - is written and performed with enough heart-on-sleeve honesty to paper over many more cracks than Sing actually has. Sure, there are times where it feels like the sheer multitude of characters means certain moments don’t get the focus they need, and there are certainly notes and song choices - particularly the use of Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah” during a moment of sombre redemption - that will be too on-the-nose for even the most wide-eyed audience member, but beyond that there’s really nothing wrong with this movie at all, to the extent that I’m a little confused every time I see a bad review of it. It’s certainly not perfect, but it’s assembled with such professionalism and such a conscious eagerness to make you happy - especially during its barnstorming, impossibly fleet-footed finale - that it seems churlish to refuse.

Despite what I perceived to be a relative lack of appreciation of its full merits, I’m happy to see that this film did well for itself, and I hope it encourages Illumination to make more movies with this kind of heart behind it. Sing’s emotional stakes may be somewhat prosaic, but they’re big and bold and dominant in a way that prior Illumination movies, with their focus on slapstick silliness, have seemed shy about embracing. In a previous post, I lamented the studio’s inability to produce a truly classic movie up until this point, and expressed a hope that Sing might be a step along the right path; in that respect, it delivered. Sing may not be the first great Illumination movie, but if they keep going in this direction, they may just get there.

THE BEST OF THE YEAR

In descending order, these are my top five animated movies of the year. They may be very different films operating and succeeding on different levels, but in my view these are the films that really encapsulated all the facets of what I love about animated cinema, and exemplify the form’s boundless versatility.

5. Sausage Party

In film criticism, originality is often taken to be a cardinal virtue; we mark films down for adhering to weathered formulas or archetypes, and give credit for the ones that do things we haven’t seen before. When Sausage Party was released last year to rock-solid reviews, many were shocked, but really, they ought not have been that surprised - after all, it’s not often that we get to see what a truly original movie looks like.

On paper, Sausage Party seems transgressive without being all that groundbreaking; after all, we’ve seen crude animated movies for adult audiences before, from Fritz the Cat through to the works of Trey Parker and Matt Stone, but there’s something about the way Sausage Party was positioned that made it unique - sure, it was made for a mere $19 million, but this was that rare R-rated animated film that was ordained to compete in the big leagues, rather than breaking out from some underground niche. US-produced adult animations usually accept their status as esoteric oddities, embracing unfashionable visual styles and anti-mainstream sensibilities; Sausage Party rejects that, using modern tools and an aesthetic that credibly approximates the familiar look of its Disney/Pixar contemporaries to mark itself as a film designed to be seen and embraced by the biggest possible audience. Regardless of what you might think of the film itself, the manner of Sausage Party’s release was trailblazing - the first proper attempt by a studio in years to break American adult animation out of its enthusiasts-only ghetto and show that cartoons for older audiences can be appeal on the same level as a live-action movie of the same genre. That Sausage Party went on to gross of nearly $100 million in the US should be seen a massive win for the medium, and will hopefully embolden the industry to further experiment with the kinds of animated stories and visions they’re willing to bankroll in future.

Of course, this victory would feel tainted if Sausage Party had turned out to be exploitative trash, but watching the final film, even hardcore Sausage-sceptics would have to admit it’s a movie that embraces substantive ideas and commits to them, hard. Your mileage is likely to depend on how well you click with the sensibilities of Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg (Superbad, This is the End, The Interview), who’ve made a career on exploring challenging concepts in unabashedly juvenile terms, because this movie represents the apotheosis of their operating model to date; taking the Pixar template of “what if X had feelings?” to its most lurid conclusion, Sausage Party is a deceptively literate spiritual odyssey that confronts sentient food items with the brutal reality of what they were created for, sending them spiralling into existential crisis and surreal voyages of self-actualisation. As a deconstruction and critique of religious thought, it’s intelligent in a number of ways, opting against abrasive confrontationalism in favour of a humanist, pluralist conclusion that encourages people to reject the limits that society places on them and be their authentic selves in a non-judgemental fashion; what’s just as impressive is the way it’s able to explore this essentially benign, moderate message in such relentlessly coarse, taboo-shattering terms, without feeling like it’s working at crossed purposes with itself. This is a film with legitimately interesting things to say about the evils of dogma, the need for respectful discourse, the importance of actualising your sexual identity and the destructiveness of identity-based conflict - and does so almost entirely through the medium of cartoon violence and dick jokes. All of this builds to a jaw-dropping third act of insanely violent, sexualised excess that’s honestly unlike anything I’ve ever seen in a mainstream movie - and yet somehow still feels reverent enough to the spirit of Toy Story that its credentials as a legitimate entry in the same animated adventure genre remain unbroken.

I’m ardent in my admiration for what Sausage Party represents, and I say that with full acceptance of its problems. Its gleeful indulgence of ethnic stereotyping, for example, doesn’t really pay off with a satirical point clever enough to justify it all, while the sheer crudeness of the film - the villain is literally an anthropomorphic douche - is likely to stop a lot of people from connecting. I also need to give acknowledgement to the widespread stories of mistreatment and exploitation of the animation team by production company Nitrogen Studios and co-director Greg Tiernan, which puts that thrifty $19 million budget in a different light; that can’t really be excused, but it also doesn’t invalidate the fact that the resulting film is a valuable, singular piece of pop art that’s worth much more than the sum of its parts. It’s up to you to decide whether knowing how the sausage was made is enough to put you off; all I’m saying is that it’s worth trying, because Sausage Party is both tastier and more nutritious than you might expect.

4. Trolls

One of the main reasons why 2016 ended up such a good year for animation is that, due to some strange quirk of scheduling, many of the major studios ended up releasing two films during the year. I’ve covered Illumination’s pair already, and I’ll be coming to Disney’s duo momentarily; for now, I want to give some much-needed kudos to the oft-criticised DreamWorks, who not only turned out a fine Kung Fu Panda sequel, but also somehow elevated a reboot of the Trolls toy franchise from cultural detritus into a genuinely joyous moviegoing experiences.

I expounded at length quite recently about the many virtues of Mike Mitchell and Walt Dohrn’s cuddly little movie, so I won’t add too much here, other than to say that my admiration for a film that still stands out as a surprise of the most pleasant variety hasn’t dimmed. There’s always a special kind of joy that comes with being blindsided by a great film that comes out of nowhere, and Trolls is the very definition of that: the concept sounded terrible, the early marketing was appalling, and yet the final film is confident, earnest, visually beguiling and bursting with an infectiously guileless goodwill that’s much harder to evoke in a sincere way than Trolls makes it look. Indeed, in a world where Sony Pictures Animation continues to struggle to strike the right tone with its various adaptations of the esteemed Smurfs franchise, DreamWorks deserves applause for nailing the right mix of sweetness and spice on the first attempt at what’s essentially the same concept. That’s not to say Trolls is wholly derivative, though; if the “happy forest friends” setup isn’t exactly groundbreaking, there’s ambition to its lightly-sketched philosophical exploration of the spiritual origins of happiness, while its sharp humour and aesthetic exuberance ensure it never forgets to make you feel the emotion it’s examining. If there’s one lingering disappointment, it’s that more people didn’t notice exactly how impressive this fluffy and genuinely uplifting jukebox musical turned out to be; with its theatrical run topping out at a solid but unspectacular $339.5 million worldwide, Trolls remains one of 2016’s better-kept secrets, a movie that seemed to pass most people by. That’s an unfortunate outcome for a film that I’m willing to list among the best animations of the year, but it does at least preserve its status as a surprise package waiting to be opened, shared and discovered by more people.

I hope, too, that DreamWorks take solace and pride in the quality of the work they put out in 2016. Both Kung Fu Panda 3 and Trolls both ended up as modest rather than overwhelming commercial successes, but there was a solidity and assuredness to both movies that the studio hasn’t always found easy to come by; these are qualities that will serve the company well as it prepares for life under the new ownership of Universal. Of course, DreamWorks will always be DreamWorks, and maybe inconsistency is baked into their DNA: the fact they’re following up such a strong 2016 with a 2017 slate consisting of The Boss Baby and Captain Underpants: The First Epic Movie seems like a testament to that. But hey, this time last year I was busy writing off Trolls, so what the hell do I know?

3. Moana

It’s weird for me to think about this, but most people born after about 1990 or so probably don’t actually remember a time when Disney were the undisputed kings of feature animation. Ever since Pixar released Toy Story in 1995, they’ve ceased to be the only game in town, and there were times during the mid-2000s when they looked to be drifting into irrelevance; since then, however, they’ve come roaring back, and I feel as though 2016 will be seen in years to come as a point where Walt Disney Animation Studios really reasserted their dominance, even more so than their historic success with Frozen in 2013. I’ve praised Illumination and DreamWorks for the impressive feat of releasing two good movies in the same year, but that pales in comparison to Disney, whose achievement in releasing two potential all-time classics within eight months is little short of a miracle.

Due to its choice of genre, Moana was probably seen as the safe option out of the two movies, but anyone who’s seen it will know that writing it off as just another Disney princess musical is doing the film a massively reductive disservice. Veteran directors Ron Clements and John Musker’s (The Little Mermaid, Aladdin, The Princess and the Frog) first CGI movie feels like a substantial and welcome reinvention not just of their filmmaking approach, but of the “princess movie” template in general. This is a formula that Disney have been committed to tinkering with since the 1990s Disney Renaissance era, but never to such a root-and-branch degree as Moana, which takes only the most essential components of the template - to paraphrase the script itself, the fact that its protagonist “is the daughter of a chief, wears a dress and has an animal sidekick” - and builds a rousingly individualistic seafaring action-adventure with a refreshing perspective. It’s not just the fact that Moana feels different from her predecessors, with her Polynesian origins and stockier build, it’s that she functions differently; unlike any other Disney princess, she’s a swashbuckling hero first and foremost, embarking on a world-saving quest through active choice, rather than stumbling into one as a byproduct of some mission of family duty. On that foundation, Musker and Clements build a film that consistently zags where other Disney movies zig. This is an action-adventure that’s basically without a true villain; where the male lead, the blustering demigod Maui, remains strictly a supporting player, with no hint of unnecessary romantic intrigue; where the main animal sidekick is a scraggly idiot rooster that actively hinders the quest, while the cute, marketable pig stays home.

Of course, different isn’t necessarily better, but it certainly feels like a value-added bonus when your film is already as good as Moana is. Technically, it’s one of Disney’s most accomplished efforts, with astounding water effects and a beautiful oceanic palette, and it benefits from the same sparky dialogue and buddy-comedy chemistry between its leads that’s become a Disney trademark. Musker and Clements seem to have made progress on overcoming the somewhat episodic feel of their previous movies, with more of a sense of coherent driving momentum pushing forward the story, and they’ve certainly come on leaps and bounds in terms of cultural authenticity since the days of, say, Aladdin, with the Pacific Island setting treated with great respect in aesthetic, spiritual and casting terms. Then, of course, there’s Lin-Manuel Miranda, Opetaia Foa’i and Mark Mancina’s compositionally intricate and effortlessly catchy soundtrack, which is probably the finest from Disney since The Lion King - and hell, even The Lion King didn’t have a glam rock David Bowie style parody sung by a giant kleptomaniac crab, so maybe Moana has even that one beaten. It’s not all perfect, though; much as I loved the film, it does have a few pacing problems; the story spends an unusually long time getting Moana to leave her home island of Motunui, only to occasionally feel becalmed once the journey actually gets underway. The open ocean is an evocative setting, but it can also get pretty repetitive, and there are points in Moana where you start to miss the broader ensemble cast and diverse backdrops that we might have gotten if not for all the lonely, endless blue.

None of that was enough to prevent Moana from becoming one of the best and biggest animated movies of the year - though you get the sense that some pundits were expecting a bit more commercially from Disney’s first big princess musical since Frozen. It’s true that Moana’s solid $575 million-and-counting worldwide total doesn’t bear comparison to Frozen’s record-setting $1.27 billion - but then, when you think about it, Moana didn’t really turn out to be all that comparable to Frozen anyway. It’s possible that Moana reinvented so much about what makes a princess movie that it no longer registered as being one in the eyes of the audience - or perhaps it was never really a princess movie in the first place, and scored its own success on its own terms. Princess or not, she is Moana, and that’s good enough for me.

2. Your Name (Kimi no Na wa)

As I mentioned before, I have an unfortunate blind spot when it comes to anime, with my exposure to Japan’s prolific feature output basically limited to Studio Ghibli films and a small handful of others. That’s something I’d like to work on, so I jumped at the chance to see Makoto Shinkai’s blockbusting romance Your Name at the cinema last year as a way of putting that right; what I got was an outstanding and emotionally overwhelming reminder of everything I’ve been missing out on.

Your Name is a difficult movie to categorise - my best attempt would be “supernatural gender/body-swap tragicomedy-drama disaster romance epic”, but even that would be underselling the deft changeability and tonal fluidity of this marvellously-constructed movie, which came within a hair’s breadth of ranking as my favourite of the year. Part of that versatility comes from its mastery of the medium - I know it’s not intended to function as a primer on anime, but it couldn’t have done a better job if it tried, such is its command of everything that defines the format at its best. Here’s a 2D animated film that feels truly modern, that pushes hand-drawn animation to new levels of technical beauty and adventurous stylisation without feeling even slightly retro; here’s an animated film that can speak directly to a teenage and young adult audience, with a pop soundtrack and frank allusion to concepts of sexuality and gender identity, and evoke that lived experience of yearning adolescence in a way that feels sophisticated and universal; here’s an animated film that knows how to bring metaphysical mystery, power and spirituality to its narrative with a light touch, leaving just enough traces of magic to lend an edge of unknowable enormity to the intimate character story we’re being told. These are areas in which the best anime movies uniquely excel, and Shinkai seems to understand implicitly how to leverage these strengths without any of the weaknesses.

But Your Name isn’t designed to be appreciated on a beard-stroking conceptual level; for all its artistic accomplishment, it’s a weepy teenage romance at heart, and you couldn’t ask for one better. Its protagonists - small town girl Mitsuha and Tokyo boy Taki, who mysteriously find themselves intermittently swapping bodies - are enormously likeable leads with whom it’s easy to empathise, whether it’s Mitsuha’s longing to experience life beyond her idyllic but fishbowl-like rural community, or Taki’s increasingly passionate desire to connect directly with the girl who’s literally changing his life from the inside. The latter quest comes to form the driving emotional engine of the film, and writer-director Shinkai does a fine job of creating a palpable closeness between the two characters, whilst at the same time putting them in a situation where every conceivable obstacle - time, space, fate - stand in the way of them ever meeting. If that sounds melodramatic, that’s because it is, but Your Name knows exactly how to sell a brand of epic romance that makes the audience feel like they’re seeing something much more profound than the feelings of two people; that’s partly a function of the gorgeous hyperreality of the visuals, but also a testament to the way Shinkai unfolds the story, expanding what starts out as a light, sweet body-swap fantasy into something larger and more mythic. To say more about how Your Name pivots and pirouettes through different plot ideas and genres would give too much away about a film that benefits greatly from being unpacked at its own pace, so I won’t go further, other than to say it builds to something that’s sweeping, exhilarating and wistful in all the right ways.

If it sounds like I’m giving this movie the hard sell, that’s very much intentional - certainly, Your Name doesn’t need any more of a push in Asia, where it’s been a record-breaking success, but Western audiences seem to be much less aware of it, as evidenced by its surprise omission from this year’s Best Animated Feature Oscar nominees. This may be partly because because the film isn’t actually due to be released in US theatres until April 7th 2017, a stunningly long delay that nevertheless gives me an opportunity to urge any American readers to make sure they catch it on the biggest possible screen. After all, Your Name helped to show me everything I’m missing by not watching enough good anime; the least I can do to return the favour is to make sure nobody misses this one.

1. Zootopia

Nobody who’s followed this blog for any length of time will be shocked by this choice; in fact, nobody who saw the Oscars or pays any attention to the film industry in general will be too surprised, as Disney’s Zootopia has proven a commercial phenomenon, a darling among reviewers and an awards magnet. Inevitably, this means the film has started to attract a few contrarian potshots, but I’m not interested in engaging with that; after all if we can’t take a moment to earnestly celebrate one of the best and bravest films Disney have made in decades, then why do we even watch movies?

I’ve spent a lot of words talking about Zootopia over the last 12 months, and yet it still doesn’t feel like it’s left my system; with its incredible visual design, instantly lovable character chemistry, deft pacing and bubbling comedic energy, it encapsulates pretty much every one of Disney’s traditional strengths, while also excelling in areas where the studio have never traditionally dared to tread. As a piece of worldbuilding, its thoroughness exceeds many science-fiction films - the breathtaking wonder of the first train ride into the city of Zootopia is a Disney moment for the ages, rendered with such immersive intimacy that I’d love to see it retrofitted as a VR experience - while the film’s vaulting thematic ambitions and willingness to delve into challenging social commentary feel like a seismic sea change for a company with a reputation for corporatised artistic conservatism. That I rate Zootopia as the best animated film of an incredibly strong year doesn’t preclude acknowledgement of its imperfections - the police procedural elements are a little oversimplified, it can be episodic at times, the metaphors can sometimes be heavy-handed - but it’s the intelligent, open-hearted generosity of the thematic dialogue it opens up with its audience that makes those concerns feel small. This is a pointed, satirical and often overtly politicised piece of work, addressing deeply divisive issues of prejudice, system bias, internalised privilege and societal identity, and yet it manages to do so in a way that feels pluralistic, universally empowering and non-judgemental - a feat that most adult-oriented media struggles to achieve. It’s a film that educates without lecturing, that shows asks you to find your own answers rather than spoonfeeding you solutions, that shines a light on the problems that society faces but still lets you walk out feeling energised, rather than depressed. That’s difficult for any movie to achieve; for Disney, with almost no experience of making topical satire, to be able to pull this off while still ticking all the boxes of a superlative, adorable and hilarious family adventure is one of the greatest accomplishments in their entire 80-year history of feature animation.

Honestly, if I have any lingering feeling of disappointment about Zootopia, it’s the question of why the message it expressed so eloquently didn’t end up making a bigger impression on those who saw it. That a movie with such an explicitly educational theme of cultural unification and overcoming differences was able to gross more than $1 billion in a year as riven by political division and opprobrium as 2016 is a testament to cinema’s value as a means of escape; unfortunately, it also probably tells us a lot about the cognitive dissonance that prevents people from actually living up to the virtues expressed by the media they enjoy. I started the year wondering whether Zootopia would be as good a movie as we deserve from Disney in 2016; I ended it wondering whether 2016 deserved Zootopia. Nevertheless, I’ll try to hold on the virtues the film embodied, and take heart from the fact that children raised with this heartfelt, articulate and deeply empathetic movie stand a much better chance of learning the right lessons from it than the rest of us did. After all, if a naive rabbit and a jaded fox can learn to overcome prejudice, see things from other perspectives and make the world a better place, maybe there’s hope for the rest of us mammals as well.

#Zootopia#zootropolis#your name#kimi no na wa#moana#trolls#dreamworks trolls#sausage party#sing movie#kung fu panda#storks#Finding Dory#kubo and the two strings#the secret life of pets#The Angry Birds Movie#best of 2016#oscar#academy awards#Disney#film analysis

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Celebrating the undersung heroism of The Peanuts Movie

In December 2015, a movie reboot of one of history’s most beloved entertainment brands was released in cinemas, and it took the world by storm. That movie was not The Peanuts Movie.

Not that I’m setting myself up as an exception to that. Like pretty much everyone else, I spent the tail-end of 2015 thoroughly immersing myself in all things Star Wars: The Force Awakens, drinking deeply of the hype before seeing it as many times as I could - five in total - before it left theatres. In the midst of all that Jedi madness, I ended up totally forgetting to see The Peanuts Movie, Blue Sky Studios’ well-reviewed adaptation of Charles M. Schulz’s classic newspaper strip, which I’d been meaning to catch over the festive period. But then, it’s not as though the schedulers made it easy for me; in the US, there had been a buffer zone of a month between the launches of the two films, but here in the UK, Peanuts came out a week after Star Wars; even for this animation enthusiast, when it came to a choice between seeing the new Star Wars again or literally any other film, there was really no contest at all.

A year later, belatedly catching up with the movie I missed at the height of my rekindled Star Wars mania proved an eye-opening experience, and places Blue Sky’s film in an interesting context. With a $246.2 million worldwide gross, The Peanuts Movie did well enough to qualify as a hit, but it remains the studio’s lowest earner to date; in retrospect, it seems likely that going head-to-head with Star Wars and the James Bond movie Spectre didn’t exactly maximise its chances of blockbuster receipts. Yet in an odd way, modest, unnoticed success feels like a fitting outcome for The Peanuts Movie, a film that acts as a perfectly-formed celebration of underappreciated decency in a world of bombast and bluster. Charlie Brown, pop culture’s ultimate underdog, was never fated to emerge victorious in a commercial battle against Han Solo and James Bond, but his movie contains a grounded level of heartfelt sympathy for the small-scale struggles of unassumingly ordinary folk that higher-concept properties don’t have the time to express. The Peanuts Movie is a humbly heroic film about a quietly laudable person, made with understated bravery by underrated artists; I hope sincerely that more people will discover it like I did for years to come, and recognise just how much of what it says, does and represents is worth celebrating.

CELEBRATING... BLUE SKY STUDIOS

Before giving praise to The Peanuts Movie itself, it’d be remiss of me not to throw at least a few kind words in the direction of Blue Sky Studios - a group of filmmakers who I’m inclined to like, somewhat despite themselves, and who don’t always get very kind things written about them. After all, the 20th Century Fox subsidiary have been in the CGI feature animation mix since 2002, meaning they have a more established pedigree than most studios, and their long-running Ice Age franchise is a legitimately important, formative success story within the modern era of American animation. Under the creative leadership of Chris Wedge, they’ve managed to carve and hold a niche for themselves in a competitive ecosystem, hewing close to the Shrek-inspired DreamWorks model of fast-talking, kinetic comedy, but with a physical slapstick edge that marked their work out as distinct, at least initially. Sure, the subsequent rise of Illumination Entertainment and their ubiquitous Minions has stolen that thunder a little, but it’s important to remember that Ice Age’s bedraggled sabretooth squirrel Scrat was the CGI era’s original silent comedy superstar, and to recognise Blue Sky’s vital role in pioneering that stylistic connection between the animation techniques of the 21st century and the knockabout nonverbal physicality of formative 20th century cartooning, several years before anyone else thought to do so.

For all their years of experience, though, there’s a prevailing sense that Blue Sky have made a habit of punching below their weight, and that they haven’t - Scrat aside - established the kind of memorable legacy you’d expect from a veteran studio with 15 years of movies under their belt. Like Illumination - the studio subsequently founded by former Blue Sky bigwig Chris Meledandri - they remain very much defined by the influence of their debut movie, but Blue Sky have unarguably been a lot less successful in escaping the shadow of Ice Age than Illumination have in pulling away from the orbit of the Despicable Me/Minions franchise. Outside of the Ice Age series, Blue Sky’s filmography is largely composed of forgettable one-offs (Robots, Epic), the second-tier Rio franchise (which, colour palette aside, feels pretty stylistically indistinct from Ice Age), and a pair of adaptations (Horton Hears a Who!, The Peanuts Movie) that, in many ways, feel like uncharacteristic outliers rather than thoroughbred Blue Sky movies. Their Ice Age flagship, meanwhile, appears to be leaking and listing considerably, with a successful first instalment followed by three sequels (The Meltdown, Dawn of the Dinosaurs and Continental Drift) that garnered successively poorer reviews while cleaning up at the international box office, before last year’s fifth instalment (Collision Course) was essentially shunned by critics and audiences alike. Eleven movies in, Blue Sky are yet to produce their first cast-iron classic, which is unfortunate but not unforgivable; much more troubling is how difficult the studio seems to find it to even scrape a mediocre passing grade half the time.

Nevertheless, while Blue Sky’s output doesn’t bear comparison to a Disney, a Pixar or even a DreamWorks, there’s something about them that I find easy to root for, even if I’m only really a fan of a small percentage of their movies. Even their most middling works have a certain sense of honest effort and ambition about them, even if it didn’t come off: for example, Robots and Epic - both directed by founder Chris Wedge - feel like the work of a team trying to push their movies away from cosy comedy in the direction of larger-scale adventure storytelling, while the Rio movies, for all their generic antics and pratfalls, do at least benefit from the undoubted passion that director Carlos Saldanha tried to bring to his animated realisation of his hometown of Rio de Janeiro. I’ll also continue to celebrate the original Ice Age movie as a charismatic, well-realised children’s road movie, weakened somewhat by its instinct to pull its emotional punches, but gently likeable nevertheless; sure, the series is looking a little worse for wear these days, but at least part of the somewhat misguided instinct to keep churning them out seems to stem from a genuine fondness for the characters. Heck, I’m even inclined to look favourably on Chris Wedge’s ill-fated decision to dabble in live-action with the recent fantasy flop Monster Trucks; after all, the jump from directing animation to live-action is a tricky manoeuvre that even Pixar veterans like Andrew Stanton (John Carter) and Brad Bird (Tomorrowland) have struggled to execute smoothly, and the fact he attempted it at all feels indicative of his studio’s instinct to try their best to expand their horizons, even if their reach sometimes exceeds their grasp.

Besides, it’s not as though their efforts so far have gone totally unrewarded. The third and fourth Ice Age movies scored record-breaking box office results outside the US, while there have also been a handful of notable successes in critical terms - most prominently, Horton Hears a Who! and The Peanuts Movie, the two adaptations of classic American children’s literature directed for the studio by Steve Martino. I suppose you can put a negative spin on the fact that Blue Sky’s two best-reviewed movies were the ones based on iconic source material - as I’ve noted, the films do feel a little bit like stylistic outliers, rather than organic expressions of the studio’s strengths - but let’s not kid ourselves that working from a beloved source text isn’t a double-edged sword. Blue Sky’s rivals at Illumination proved that much in their botching of Dr Seuss’ The Lorax, as have Sony Pictures Animation with their repeated crimes against the Smurfs, and these kinds of examples provide a better context to appreciate Blue Sky’s sensitive, respectful treatments of Seuss and Charles Schulz as the laudable achievements they are. If anything, it may actually be MORE impressive that a studio that’s often had difficulty finding a strong voice with their own material have been able to twice go toe-to-toe with genuine giants of American culture and emerge not only without embarrassing themselves, but arguably having added something to the legacies of the respective properties.

CELEBRATING... GENUINE INNOVATION IN CG ANIMATION

Of course, adding something to a familiar mix is part and parcel of the adaptation process, but the challenge for any studio is to make sure that anything they add works to enrich the material they’re working with, rather than diluting it. In the case of The Peanuts Movie - a lavish computer-generated 3D film based on a newspaper strip with a famously sketchy, spartan aesthetic - it was clear from the outset that the risk of over-egging the pudding was going to be high, and that getting the look right would require a creative, bespoke approach. Still, it’s hard to overstate just how bracingly, strikingly fresh the finalised aesthetic of The Peanuts Movie feels, to the degree where it represents more than just a new paradigm for Schulz’s characters, but instead feels like a genuinely exciting step forward for the medium of CG animation in general.

Now, I’m certainly not one of those old-school puritans who’ll claim that 2D cel animation is somehow a better, purer medium than modern CGI, but I do share the common concern that mainstream animated features have become a little bit aesthetically samey since computers took over as the primary tools. There’s been a tendency to follow a sort of informal Pixar-esque playbook when it comes to stylisation and movement, and it’s only been relatively recently that studios like Disney, Illumination and Sony have tried to bring back some of that old-school 2D squash-and-stretch, giving them more scope to diversify. No doubt, we’re starting to see a spirit of visual experimentation return to the medium - the recent stylisation of movies like Minions, Cloudy With a Chance of Meatballs, Hotel Transylvania and Storks are testament to that - but even so, it feels like there’s a limit to how far studios are willing to push things on a feature film. Sure, Disney and Pixar will do gorgeous, eye-popping visual style experiments in short movies like Paperman, Inner Workings and Piper, but when it comes to the big movies, a more conservative house style invariably reasserts itself.

With the exception of a greater-than-average emphasis on physicality, Blue Sky’s typical playbook hasn’t really differed that much from their peers, which is partly why their approach to adapting Seuss and Schulz - two artists with immutable, iconic art styles of their own - have stood out so much. Their visual work on Horton Hears a Who! was groundbreaking in its own way - it was, after all, the first CG adaptation of Dr Seuss, and the result captured the eccentric impossibilities and flourishes of the source material much better than Illumination managed four years with The Lorax - yet The Peanuts Movie presented a whole new level of challenge. Where Seuss’s worlds exploded off the page with colour and life and elastic movement, Schulz’s were the very model of scribbled understatement, often eschewing backgrounds completely to preserve an expressive but essentially sparse minimalism. Seuss’s characters invited 3D interpretation with their expressive curves and body language; the Peanuts cast, by contrast, make no three-dimensional sense at all, existing only as a limited series of anatomically inconsistent stock poses and impressionist linework that breaks down the moment volume is added. It’s not that Charlie Brown, Snoopy and co are totally resistant to animation - after all, the Peanuts legacy of animated specials and movies is almost as treasured as the comic strip itself - but it’s still worth noting that the Bill Melendez/Lee Mendelson-produced cartoons succeeded mostly by committing fully to the static, spare, rigidly two-dimensional look of Schulz’s comic art, a far cry from the hyper-malleable Chuck Jones/Friz Freleng-produced style of the most famous Seuss adaptations.

Perhaps realising that Schulz cannot be made to adapt to 3D, Blue Sky went the opposite route: making 3D adapt to Schulz. The results are honestly startling to behold - a richly colourful, textured, fluidly dynamic world, populated by low-framerate characters who pop and spasm and glide along 2D planes, creating a visual experience that’s halfway between stop-motion and Paper Mario. It’s an experiment in style that breaks all the established rules and feels quite unlike anything that’s been done in CGI animation on this scale - with the possible exception of The Lego Movie - and it absolutely 100% works in a way that no other visual approach could have done for this particular property. Each moment somehow manages to ride the line of contradiction between comforting familiarity and virtuoso innovation; I’m still scratching my head, for example, about how Blue Sky managed to so perfectly translate Linus’s hair - a series of wavy lines that make no anatomical sense - into meticulously rendered 3D, or how the extended Red Baron fantasy sequences are able to keep Snoopy snapping between jerky staccato keyframes while the world around him spins and revolves with complete fluidity. Snoopy “speaks”, as ever, with nonverbal vocalisations provided by the late Bill Melendez, director of so many classic Peanuts animations; the use of his archived performance in this way is a sweet tribute to the man, but one that hardly seems necessary when the entire movie is essentially a $100 million love letter to his signature style.

I do wonder how Melendez would’ve reacted to seeing his work aggrandised in such a lavish fashion, because it’s not as though those films were designed to be historic touchstones; indeed, much of the stripped-back nature of those early Peanuts animations owed as much to budgetary constraints and tight production cycles as they did to stylistic bravery. Melendez’s visuals emerged as they did out of necessity; it’s an odd quirk of fate that his success ended up making it necessary for Blue Sky to take such bold steps to match up with his template so many decades later. Sure, you can argue that The Peanuts Movie is technically experimental because it had to be, but that doesn’t diminish the impressiveness of the final result at all, particularly given how much easier it would have been to make the film look so much worse than this. It’d be nice to see future generations of CG animators pick up the gauntlet that films like this and The Lego Movie have thrown down by daring to be adventurous with the medium and pushing the boundaries of what a 3D movie can look and move like. After all, trailblazing is a defining component of Peanuts’ DNA; if Blue Sky’s movie can be seen as a groundbreaking achievement in years to come, then they’ll really have honoured Schulz and Melendez in the best way possible.

CELEBRATING... THE COURAGE TO BE SMALL

In scaling up the visual palette of the Peanuts universe, Blue Sky overcame a key hurdle in making the dormant series feel worthy of a first full cinematic outing in 35 years, but this wasn’t the only scale-related challenge the makers of The Peanuts Movie faced. There’s always been a perception that transferring a property to the big screen requires a story to match the size of the canvas; in the animation industry, that’s probably more true now than it’s ever been. Looking back at the classic animated movies made prior to around the 1980s and 1990s, it’s striking how many of them are content to tell episodic, rambling shaggy dog stories that prioritise colourful antics and larger-than-life personalities over ambitious narrative, but since then it feels like conventions have shifted. Most of today’s crop of successful animations favour three-act structures, high-stakes adventure stories and screen-filling spectacle - all of which presents an obvious problem for a movie based on a newspaper strip about a mopey prepubescent underachiever and his daydreaming dog.

Of course, this isn’t the first time that Charlie and Snoopy have had to manage a transition to feature-length narrative, but it was always unlikely that Blue Sky would follow too closely in the footsteps of the four previous theatrical efforts that debuted between 1969 and 1980. All four are characterised by the kind of meandering, episodic structure that was popular in the day, which made it easier to assemble scripts from Schulz-devised gag sequences in an essentially modular fashion; the latter three (Snoopy, Come Home from 1972, Race for Your Life, Charlie Brown from 1977 and Bon Voyage, Charlie Brown (and Don't Come Back!!) from 1980) also made their own lives easier by incorporating road trips or journeys into their storylines, which gave audiences the opportunity to see the Peanuts gang in different settings. The first movie, 1969’s A Boy Named Charlie Brown, also features a road trip aspect to its plotline, but in most respects offers the most typical and undiluted Peanuts experience of the four original films; perhaps as a result, it also feels quite aggressively padded, while its limited cast (lacking later additions like Peppermint Patty and Marcie) and intimately dour focus made it a sometimes claustrophobic cinematic experience.

Given The Peanuts Movie’s intention to reintroduce the franchise to modern audiences who may not necessarily be familiar with the original strip’s melancholic sensibilities, the temptation was always going to be to balloon the property outwards into something broad, overinflated and grand in a way that Schulz never was; it’s to be applauded, then, that The Peanuts Movie ends up as that rare CGI animation that tells a small-scale story in a focused manner over 90 minutes, resisting the urge to dilute the purity of its core character-driven comedy material with any of the family adventure elements modern audiences are used to. Even more so than previous feature-length Peanuts movies, this isn’t a film with any kind of high-concept premise; rather than sending Charlie Brown out on any kind of physical quest, The Peanuts Movie is content to offer a simple character portrait, showing us various sides of our protagonist’s personality as he strives to better himself in order to impress his unrequited love, the ever-elusive Little Red-Haired Girl. The resulting film is certainly episodic - each attempt to impress his object of affection sends Charlie Brown into new little mini-storylines that bring different classic characters to the foreground and evoke the stop-start format of Schulz’s strip, even though the content and style feel fresh - but all of the disparate episodes feel unified by the kind of coherent forward momentum and progressive character growth that Bill Melendez’s older movies never really reached for.

Indeed, it’s probably most telling that the film’s sole major concession to conventional cinematic scale - its extended fantasy side-story featuring Snoopy engaging in aerial battles in his imaginary World War I Flying Ace alter-ego - is probably its weakest element. These high-flying action sequences are intelligently conceived, injecting some real visual splendour and scope without intruding on the intimacy of the main story, but they feel overextended and only infrequently connected to the rest of the film in any meaningful way. This would be less of a problem if the Snoopy-centric narrative had effective emotional hooks of its own, but sadly there’s really not much there beyond the Boys’ Own parody trappings; any real investment in Snoopy’s dreamed pursuit of his poodle love interest Fifi is undermined by her very un-Schulz-like drippy damselness, and it becomes hard to avoid feeling that you’re watching an extended distraction from the parts of the movie you’re actually interested in. Of course, it’s arguable that an overindulgent fondness for Snoopy-related flights of fancy drawing attention away from the more grounded, meaningful exploits of Charlie Brown and friends is actually a fair reflection of the Peanuts franchise in its latter years, showing that Blue Sky were faithful to Schulz to a fault, but I wouldn’t like to focus too much on a minor misstep in a film that’s intelligent and committed about its approach to small-canvas storytelling in a way you don’t often see from mainstream animated films on the big screen.

CELEBRATING... LETTING THE ULTIMATE UNDERDOG HAVE HIS DAY

All of these achievements would count for very little, though, if Blue Sky’s movie wasn’t able to adequately capture the intellect and essence of Schulz’s work, a task that seems simultaneously simple and impossible. For such a sprawling franchise, Peanuts has proven remarkably resilient to tampering, meddling or ruination, with each incarnation - whether in print or in animation - remaining stylistically and tonally consistent, thanks to the strict control Schulz and his fastidious estate have kept over the creative direction of the series. On the one hand, this is a blessing of sorts for future stewards of the franchise, as it gives them a clear playbook to work from when producing new material; on the other hand, the unyielding strictness of that formula hints heavily at a certain brittleness to the Peanuts template, suggesting to would-be reinventors that it would take only a small misapplication of ambition to irrevocably damage the essential Schulz-ness of the property and see the result crumble to dust. This has certainly proven the case with Schulz’s contemporary Dr Seuss, one of few American children’s literature writers with a comparable standing to the Peanuts creator, and an artist whose literate, lyrical and contemplative work has proven eminently easy to ruin by misguided adapters who tried and failed to put their own spin on his classic material.

There’s no guesswork involved in saying these concerns were of paramount importance to the Schulz estate when prepping The Peanuts Movie - director Steve Martino was selected specifically on the strength of his faithful adaptation of Seuss’ Horton Hears a Who!, and the film’s screenplay was co-written by Schulz’s son Craig and grandson Bryan - but even taking a cautious approach, there are challenges to adapting Schulz for mainstream feature animation that surpass even those posed by Seuss’ politically-charged poetry. For all his vaulting thematic ambition, Seuss routinely founded his work on a bedrock of visual whimsy and adventurous, primary-colours mayhem, acting as a spoonful of sugar for the intellectual medicine he administered. Schulz, on the other hand, preferred to serve up his sobering, melancholic life lessons neat and unadulterated, with the static suburban backdrops and simply-rendered characters providing a fairly direct vessel for the strip’s cerebral, poignant or downbeat musings. The cartoonist’s willingness to honestly embrace life’s cruel indignities, the callousness of human nature and the feeling of unfulfilment that defines so much of regular existence is perhaps the defining element of his work and the foundational principle that couldn’t be removed without denying Charlie Brown his soul - but it’s also something that might have felt incompatible with the needs and expectations of a big studio movie in the modern era, particularly without being able to use the surface-level aesthetic pleasure that a Seuss adaptation provides as a crutch.

I’ve already addressed the impressive way The Peanuts Movie was able to make up the deficit on visual splendour and split the difference in terms of the story’s sense of scale, but the most laudable aspect of the film is the sure-footed navigation of the tonal tightrope it had to tread, deftly balancing the demands of the material against the needs of a modern audience, which are honestly just as important. Schulz may have been a visionary, but his work didn’t exist in a vacuum; the sometime brutal nature of his emotional outlook was at least in part a reaction to the somewhat sanitised children’s media landscape that existed around him at the time, and his work acted as an antidote that was perhaps more necessary then than it is now. That’s not to say the medicinal qualities of Schulz’s psychological insights don’t still have validity, but to put it bluntly I don’t think children lack reminders in today’s social landscape that the world can be a dark, daunting and depressing place, and it feels like Martino and his team realised that when trying to find the centre of their script. Thus, The Peanuts Movie takes the sharp and sometimes bitter flavour of classic Schulz and filters it, finding notes of sweetness implicit in the Peanuts recipe and making them more explicit, creating a gentler blend that goes down smoother while still feeling like it’s drawn from the original source.

The core of this delicate work of adaptation is the film’s Charlie Brown version 2.0 - still fundamentally the same unlucky totem of self-doubt and doomed ambition he’s always been, but with the permeating air of accepted defeat diminished somewhat. This Charlie Brown (voiced by Stranger Things’ Noah Schnapp) shares the shortcomings of his predecessors, but wears them better, stands a little taller and feels less vulnerable to the slings and arrows that life - and ill-wishers like Lucy Van Pelt - throw at him. Certainly, he still thinks of himself as an “insecure, wishy-washy failure”, but his determination to become more than that shines through, with even his trademark “good grief” sometimes accompanied by a wry smile that demonstrates a level of perspective that previous incarnations of the character didn’t possess. Blue Sky’s Charlie Brown is, in short, a tryer - a facet of the character that always existed, but was never really foregrounded in quite the way The Peanuts Movie does. In the words of Martino:

“Here’s where I lean thematically. I want to go through this journey. … Charlie Brown is that guy who, in the face of repeated failure, picks himself back up and tries again. That’s no small task. I have kids who aspire to be something big and great. … a star football player or on Broadway. I think what Charlie Brown is - what I hope to show in this film - is the everyday qualities of perseverance… to pick yourself back up with a positive attitude - that’s every bit as heroic … as having a star on the Walk of Fame or being a star on Broadway. That’s the story’s core.”

It’s possible to argue that leavening the sometimes crippling depression in Charlie Brown’s soul robs him of some of his uniqueness, but it’s also not as though it’s a complete departure from Schulz’s presentation of him, either. Writer Christopher Caldwell, in a famous 2000 essay on the complex cultural legacy of the Peanuts strip, aptly described its star as a character who remains “optimistic enough to think he can earn a sense of self-worth”, rather than rolling over and accepting the status that his endless failures would seem to bestow upon him. Even at his most downbeat and “Charlie-Browniest”, he’s always been a tryer, someone with enough drive to stand up and be counted that he keeps coming back to manage and lead his hopeless baseball team to defeat year after year; someone with the determination to try fruitlessly again and again to get his kite in the air and out of the trees; someone with enough lingering misplaced faith in Lucy’s human decency to keep believing that this time she’ll let him kick that football, no matter how logical the argument for giving up might be.

Indeed, Charlie Brown’s dogged determination to make contact with that damn ball was enough to thaw the heart of Schulz himself, his creator and most committed tormentor - having once claimed that allowing his put-upon protagonist to ever kick the ball would be a “terrible disservice to him”, the act of signing off his final ever Peanuts strip prompted a change of heart and a tearful confession:

“All of a sudden I thought, 'You know, that poor, poor kid, he never even got to kick the football. What a dirty trick - he never had a chance to kick the football.”