#and with the gods being one god composed from both feminine and masculine aspects...

Text

Controversial statement but i do think there's an aspect of womb envy in Jaime's relationship to both Cersei herself, and the idea of Cersei. The fact she can create, and has created, life, and he can only cause death. They have created life together but he has no part in them and can never truly have, but she also created death for them (Robert's babies, Robert himself) which he never could. The fact he wants to kill Robert so many times but never gets to, but she does. The fact he means to kill bran but never gets to. There's something there

#jaime lannister#cersei lannister#meta#asoiaf#valyrianscrolls#we gotta have more womb envy in this series#i love this concept so much#and with the gods being one god composed from both feminine and masculine aspects...#i'm just saying we could use more womb envy ok.#mine

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Buddhist references in Saiyuki (part 1)

English translation of this post.

I love this scene a lot because of both how it was drawn (the style is very beautiful, linear, clean and detailed) and Hakkai's words. When Goku says "He looks like the real one", Hakkai replies with "Because he is the real one". Despite he is not always like a Sanzo, he is a real Sanzo due to his title and the sutra he brings on his shoulders. Here we can notice the "dual nature" of Minekura characters, in this case Genjo Sanzo, who usually does not behave like a "real" Sanzo (we know his defects well) but depending on the occasion (religious ceremony) he knows how to be one (thank god observant people don't see him when he is not in the limelight XD). Depending on the occasion we have to wear masks that do not always fit the situation.

What I like the most about Reload Blast (I actually like everything about it) are the Buddhist references that I have found in this image and will analyse here.

The first symbol that caught my interest was the Endless Knot ( srivatsa in Sanskrit , dpal be'u in Tibetan) or Eternal Knot. It is composed of closed lines intersecting at right angles and symbolizes the beginningless cycle of existence, the inextricable bond of wisdom and compassionate method of Buddha's enlightenment and infinite love and harmony. Originally it seems to have been connected to the Nagas (klu in Tibetan) serpentine beings, half human and half serpent, linked to the water element, protectors of treasures, Sutras (the Prajnaparamita Sutra was hidden by the Buddha in the Naga realm) and also many Teachings. Some of them are Dharmapala (protectors of the Dharma). This symbol is also linked to nandyavarta, a variant of swastika a primordial symbol of constant, endless flux. It is also one of Eight Auspicious Signs, why "auspicious sign"? Because it is the highest symbol of good omen if it is offered together with a gift or a writing and indicates the bond between the giver and the recipient, remembering that every positive and favorable effect for us in the future has its roots, its causes from our actions in the present. As mentioned, it represents the link between Wisdom and Method and these two, from a tantric perspective, are the feminine (Wisdom) and masculine (Method) energy. Since it has neither beginning nor end it also symbolizes the infinite wisdom and knowledge of the Buddha and the eternity of the Dharma through its ceaseless becoming and being in its manifesting for the benefit of all sentient beings. Here is a picture of it:

Author Dontpanic (DogCow in German Wikipedia)

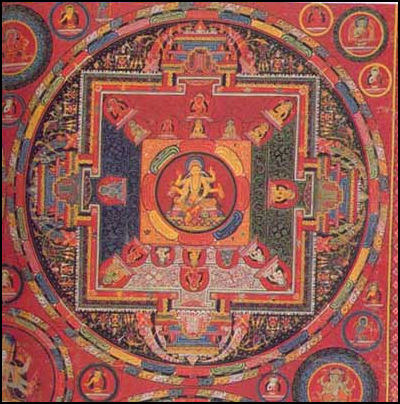

Another thing that leapt out at me is the Mandala (dkyil khor in Tibetan) which more generally represents the palace, the energy field, the Enlightened environment, the Pure Land of the Yidam taken into account. The drawing of the image is very generic, but if I get a close-up of the center I think there might be a seed syllable which is linked to Yidam (1). Mandala represents the quintessence of all phenomenal perceptions, it is the support that allows the practitioner to access these perceptions and the center is none other than the mind of the Buddhas. The Mandala is therefore a skillful means of purifying and transmuting the darkened perception of ordinary beings into enlightened perception. We have three ways to look at the Mandala:

Mandala of the Base: it is the natural Mandala of the Vision, the purity of all phenomena, the intrinsic potential of all things ans beings.

Mandala of the Way: it is the means to integrate the practice with this Vision and is divided into two aspects. The graphic Mandala which represents the plane of reality and the Mandala of significance which concerns the experiences of the practitioner, which in turn concerns the outer Mandala of external perceptions, the inner Mandala of internal perceptions and the secret Mandala which reveal the mind of wisdom.

Mandala of the Fruit: it is achieved when one obtains Buddha's (both trikaya and five wisdoms) Enlightenment (the Fruit of the Way).

Depending on the context a Mandala can have multiple meanings, i.e. it can symbolize the Guru/Master surrounded by his/her/their disciples (2). The Mandala can be divided into "Divine residence Mandala" and "Resident divinity Mandala": it must be imagined as a building of light, square with four doors that rests on an enormous cross-shaped vajra. The four doors symbolize the "Four Noble Truths", the four equal sides of the base of the Mandala represent the Equanimity of the Buddhas towards creatures. The palace is surrounded by a barrier of vajras that prevent anyone and anything from penetrating, in turn this barrier is surrounded by flames, the flames of primordial wisdom. Externally or internally (depending on the type of Tantra, but here you can't see it well, because as mentioned it is a very generic Mandala) at this line of fire or rather circle of fire there are eight cemeteries inhabited by terrible and frightening beings (I wouldn't like to hazard a guess, I think they could be the Eight cemeteries of ancient India considered suitable for meditation but I could also be wrong). This symbolizes the understanding of Emptiness, which goes beyond the dualist division of impure/pure since in Tantrism (not only in Tibetan but also in Japanese, Kashmir and other forms of Tantrism) one is beyond the dualist dichotomy of things and everything is a manifestation of primordial purity. These three barriers (the cemeteries, the vajras and the fire) teach us a very important thing: to access the Yidam palace and tantric practice you must have the ability to abandon Samsara, to develop altruistic aspiration and understand Emptiness. The "Mandala of the deities who reside there" is made up of all the deities, the main one and his retinue. At the center of each mandala there is the main Yidam, which represents the primordial condition of existence, corresponding to the space element, the Mandala is therefore a sacred space charged with the energy of the Yidam and its retinue is capable of transforming the disciple, here I put the peaceful (3) Mahamayuri Mandala:

The other object that can be seen is the incense holder which is very important in altars and offerings as can also be seen well here in this page.

As functional as these objects and symbols may seem (and I know they are in part) to the graphic representation of the place, here elements with a profound meaning that must make us reflect have been inserted. I really appreciate that Minekura included them.

Notes:

(1) In Sanskrit, iṣṭadevatā, it is translated as "meditational deity", literally "cherished divinity", but I do not like this translation choice because it can lead to the erroneous idea that in Buddhism, especially in Vajrayana, there is a god worship kind of which is not true because in Buddhism practitioner focuses on Enlightened beings and takes refuge only in them. Gods are sentient beings residing on ārūpadhātu, rūpadhātu and kāmadhātu and are all subject to the merciless rules of karma and twelve nidānas. They are in the same boat as humans, asuras, animals, pretas and naraka beings. This is why I prefer the Tibetan term Yidam which means "effort of the mind". The word is said to be a contraction of ཡིད་ཀྱི་དམ་ཚིག (yid kyi dam tshig), which means to bind one’s mind ཡིད (yid)་ by promise་དམ་ཚིག (dam tshig). I know very little of Tibetan but it intrigues me as language because of deep and interesting implications it has from a doctrinal and academic level it gives to Buddhist terms and concepts.

(2) I do not rule out that in the manga page there might be a symbolic connection between Sanzo who recites the Sutra and disciples around him.

(3) "Peaceful" here means in opposition to wrathful Yidams which use violent means to destroy obstacles to Enlightenment. Peaceful Yidams on the other hand use subduing methods to deal with obstacles.

---------------------------------------------------

Final thoughts: sorry if this description of Mandala and endless knot is not precise at describing in a more concise and spoon-fed way with types of mandalas, their meanings, symbolism etc. Information provided here are based on my personal experience with Buddhist practice, Buddhist forums, resources, books, academic texts (especially the ones made by Alexander Berzin) and experiences from other practitioners. Maybe in future I might talk in a more descriptive yet very detailed way. Here I wanted to focus more on core essence of these objects shown in the manga page. Hope you like it and have a nice day/evening.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

To celebrate Loki being confirmed as canonically queer in the Loki series, please enjoy this 12,000 word, fully referenced dissertation exploring Loki’s genderfluidity in Norse Mythology and Marvel comics....

Myth-gendering Loki: Changing attitudes to gender non-binary in the afterlives of the Prose Edda.

Abstract

This dissertation focuses on the character of Loki in the Prose Edda and in Marvel Comics as a way of exploring non-binary gender. The first chapter will use myths involving Loki as case studies through which a queer reading of the Prose Edda can be performed. Developing on the notion that the gender ambiguity in the Edda sets the foundation for Loki being a queer character, the second chapter will acknowledge how some of the most recent interpretations of Loki have fully embraced this aspect of his character and will therefore examine how this is presented through the two different mediums of comics and novels. The value of queer reading means that greater representation can be found not just in modern texts but can be sought out in the historical as well. Through the course of this dissertation, the importance of queer representation has been argued with regards to its place in history and to young adult audiences.

List of Illustrations

Figure Page

1. Stan Lee et al Journey into Mystery (New York: Marvel Comics, 1952), #85 35

2. Al Ewing et al Loki: Agent of Asgard (New York: Marvel Comics, 2020), #2 35

3. Al Ewing et al Loki: Agent of Asgard (New York: Marvel Comics, 2020), #14 35

4. Al Ewing et al Loki: Agent of Asgard (New York: Marvel Comics, 2020), #2 35

5. Al Ewing et al Loki: Agent of Asgard (New York: Marvel Comics, 2020), #5 36

6. Al Ewing et al Loki: Agent of Asgard (New York: Marvel Comics, 2020), #16 36

7. Walter Simonson et al, Thor (New York: Marvel Comics, 1966). #353 36

Contents

List of Illustrations

Introduction: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 1

Chapter One: Loki in the Edda: ………………………………………………………………………………….. 4

Gender Ambiguity: ………………………………………………………………………………………… 5

Sexual Deviance: …………………………………………………………………………………………… 10

Race: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 15

Chapter Two: Loki in Marvel: ……………………………………………………………………………………. 20

Genderfluidity: ………………………………………………………………………………………………. 21

Existing as Queer: ………………………………………………………………………………………….. 28

Identity: …………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 30

Conclusion: ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 37

Bibliography: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 39

Introduction

‘The greatest power of myth: it never stops changing, yet its appeal is eternal’.[1]

Mythology is not something which is set. With every telling and retelling it changes over and over. Even before Snorri Sturluson wrote the Prose Edda in C.1220, the myths he would commit to paper had undergone countless changes innumerable times. Once they had found their way onto the page, the assumption that they would remain there, unchanged, is therefore unwarranted. As Christopher Abram states: ‘Myths of the Pagan North have grown, changed and developed to meet the needs of the new situations in which they find themselves’.[2] With regards to this concept of changeable mythology, this dissertation sets out to examine how the Prose Edda has been changed and developed to adapt to the requirements of modern societies. Using the character of Loki as a point of entry, this dissertation will examine how the Prose Edda has been interpreted to meet these requirements, centring around the concept of non-binary gender. To achieve this, both the original text and Marvel Comic’s interpretation of Loki will be examined through a critical gender and queer perspective.

Gender as something else which is not fixed is an idea first suggested by Judith Butler. Her 1990 book Gender Trouble theorises the concept of performative gender, suggesting that masculinity and femininity are not fixed and are instead performed identities which are acted out constantly. In short gender is not a matter of biology, but instead something governed by the arbitrary rules of a heteronormative ethos. These rules, therefore, can be broken leading to the rise of gender identities that exist outside the sphere of heteronormativity. Genderfluidity and non-binarism define themselves as resistive to the conformed ideas of a binary between masculine and feminine. These terms are not only useful for defining gender identities found in our modern societies but can also be used as tools to re-examine the Edda with, using a queer lens to scrutinize gender performance in this text.

The queer lends itself effectively to the Edda because of the numerous examples of gender inversions. The Poetic Edda especially features gender deviance, with Thor crossdressing in the Thrymskviða,[3] and the questioning of Odin’s masculinity in the Lokasenna.[4] However, for the purpose of this dissertation, only Loki’s role in the Prose Edda will be examined due to it being the most consistent in terms of gender ambiguity and elements of the queer. Although Loki changes between male and female in both this text and the Marvel texts, the pronouns of he/ him will be used to remain consistent with the primary texts. Queer scholarship of the Edda does have some recent precedents, with critics like Brit Solli examining the role of Odin as a queer god, but historically the queer elements of the Edda have been explained away.[5] The main reason cited for this is the difference between the perception of the queer today and of its perception during the composing of the Edda. Although it is true that placing modern terms onto historical texts and forcing certain characters into categories that did not exist at the time can be problematic, this does not mean that a queer reading does not have relevance. Instead, it opens a new way of understanding a culturally significant text.

The Edda has experienced multiple literary afterlives, from Wagner’s Ring Cycle to a significant influence on Tolkien’s work. Most people, however, will first encounter Norse mythology through the medium of Marvel, especially after the phenomenon of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. This is why two Marvel texts, Al Ewing’s 2014-15 comic series Loki: Agent of Asgard and Mackenzi Lee’s 2019 Young Adult novel Loki: Where Mischief Lies, have been selected as examples of how mythology has been adapted to meet the needs of their new situation, namely queer representation. Loki is canonically queer in these texts, both in his sexual orientation and gender identity. Increasing diversity has been a clear part of Marvel’s agenda over the last decade, though usually through the introductions of new characters, like Kamala Khan as Ms Marvel. Loki is one of the few already established characters to be reinvented as queer. Although Marvel’s Loki is an entirely separate character to the one found in the Edda, he retains the same archetypical characteristics ensuring he resonates with the original. Whether queerness is one of these innate to Loki and is therefore essential to his character will be examined.

Why Loki so effortlessly lends himself to queer interpretations, evidence of his genderfluidity as well as the intersection of the queer, gender and race will be explored in the first chapter. Marvel’s interpretation and embracement of Loki as a genderfluid and queer character will be the focus of the second, examining how genderfluidity is presented, the pressure to conform to heteronormative societies, and the overarching issue of identity. More widely, this dissertation will argue for the queering of characters from the Edda in modern adaptations.

Chapter One: Loki in the Edda

The Prose Edda is one of our main sources for Norse Mythology. However, as it was written in Iceland around C.1220, the Edda was composed several centuries after Norse paganism had been widely practiced with Christianity replacing it as Iceland’s main religion.[6] The author Snorri Sturluson himself was a Christian and, according to Robert Kellogg, ‘largely functions as a collector or reteller’.[7] I mention this not to question the authenticity of the Edda, but to demonstrate that mythology is always subjected to change. Jan de Vries argues that Norse Mythology has undergone three different stages; a period without Christian influence, suppression from Christian forces, and a final version corrupted by a Christian presence.[8] Those backlashing against diversifying mythological figures often cite ‘original’ texts like the Edda, suggesting diversifying is corrupting the ‘real’ version of this figure. If the oldest existing version of Loki was changed to fit a Christian narrative, why should he not be changed again in modern texts to fit a narrative of queer representation? Nevertheless, this chapter will use the Edda as a way of finding evidence that even this version of Loki has innate queerness.

In the Gylfaginning, where Snorri lists all the main gods, Loki is positioned in between the male Æsir and female Asyniur.[9] Anna Birgitta Rooth refers to this position as a ‘special appendix’[10] which separates Loki from the Æsir gods he is ‘reckoned among’.[11] He is listed after the minor Æsir, making him the last of all the male gods, as this denotes his position as an outsider in the gods society. It also places him in between the male and female categories, hinting at his gender ambiguity. Snorri makes sure that Loki’s sexual deviancy is presented to his audience by listing Loki’s monstrous offspring alongside him, ‘One was Fenriswolf, the second Iormungand (i.e. the Midgard serpent), the third is Hel’, in addition to his mixed racial heritage. [12] When stating Loki’s name, ‘He is Loki or Lopt, son of the giant Fabauti’, Snorri identifies him as the child of the enemies of the gods. [13]

In Loki’s first significant appearance in the Edda, it is possible to read gender ambiguity, queer sexual deviance, and racial anxiety. Some readings of the Edda will try to explain these elements of Loki away. [14] For example, Rooth argues against examples of Loki sexual ambiguity as ‘a motif used to produce comical effects and situations’.[15] This dissertation will instead embrace queerness in the Edda, using Loki as a focal point that intersects gender ambiguity, sexual deviance, and racial anxiety. These three elements of Loki will form the structure of this queer reading of the Edda.

Gender Ambiguity

Before analysing the gender binary found in the Edda, it is important to establish what this meant to medieval Scandinavian societies. For the time of the Edda’s creation and the subsequent oral tradition of Norse myths, Thomas Laqueur defines a ‘one sex model’ where ‘to be a man or a woman was to hold a social rank, a place in society, to assume a cultural role, not to be organically one or the other of two incommensurable sexes.’[16] With regards to this model, Carol J. Clover argues that male and female were not considered opposite in the way modern societies tend to view them. Instead there was ‘a social binary, a set of two categories, into which all persons were divided, the fault line runs not between males and females per se, but between able-bodied men (and the exceptional woman) on one hand and, on the other, a kind of rainbow coalition of everyone else’.[17] This meant that gender was not necessarily assigned to biological characteristics but social ones and, consequently, fluctuated with social status. This can be linked to modern gender theories regarding the connection, or lack of, between biological sex and gender identity. Butler’s theory is particularly notable, arguing that ‘there is no gender identity behind the expressions of gender; that identity is performatively constituted by the very “expressions” that are said to be its results’.[18] However, during the Norse period, Clover notes the peril that came with this one-sex system: ‘Not only losable by men, but achievable by women, masculinity was in a kind of double jeopardy for the Norse man’.[19]

The notion of losable and achievable masculinity is illustrated by a story found in the Skaldskaparmal section of the Edda. After the kidnapping of Idunn (which Loki both caused and remedied), the giantess Skadi ‘took helmet and mail-coat and all weapons of war and went to Asgard to avenge her father’ the giant Thassi, who had been killed by the Æsir gods. [20] As part of her compensation for this, Skadi demanded that the gods made her laugh, believing this would be impossible. The task fell to Loki who uses a rather unconventional method: ‘he tied a cord round the beard of a certain nanny-goat and the end round his testicles, and they drew each other back and forth and both squealed loudly. Then Loki let himself drop into Skadi’s lap, and she laughed’.[21] Each character in this tale represents a different aspect of fluidity within the Norse gender binary: Loki represents the loss of masculinity; Skadi represents the gaining of masculinity and the goat itself represents a kind of sexual ambivalence.

Loki’s loss of symbolic masculinity is demonstrated through physical loss in this mock castration. Stefanie von Schnurbein describes this as ‘an act that places his dubious sexuality and gender identity in a grotesque light’.[22] Loki is not only physically sacrificing his masculinity, but his symbolic masculinity simultaneously. This demonstrates ‘dubious sexuality’ because Loki is displaying his testicles in a show of masculinity only to have them symbolically removed by an animal. This willingness to sacrifice his physical gender characteristics supports Butler’s concept that gender is performative and therefore has no relation to biological sex because Loki takes on a performative role, playing a sexually impotent male. Consequently, he is placed into the gendered jeopardy that Clover suggests since he loses his maleness and, therefore, his social status. This reduction in status is a fitting punishment for Loki who betrays both the gods and the giants earlier in this myth so ends up being humiliated for their entertainment. Clover notes how in Medieval Scandinavian society ‘there was finally just one "gender," one standard by which persons were judged adequate or inadequate, and it was something like masculine’.[23] In this system, Loki is undoubtedly found inadequate, and fails to meet the standard of masculinity, placing him on the opposite side of the binary.

Evidence of this decreased masculinity can be found in the position Loki ends up in. He falls into Skadi’s lap, thus ends up sitting on top of her which, in addition to his exposed genitals, creates a sexually charged image.[24] However, Loki is in the female position while Skadi is in the male for this pseudo sex position.[25] Clover notes how, despite gender not being connected to biological sex, the Norse gender system has a ‘dependence on sexual imagery’, meaning that Loki being positioned sexually as female adds to his decreased masculine status. [26] This demonstrates not only how Loki has lost his masculine status, but how Skadi has gained her own masculinity.

This increase in masculinity therefore increases Skadi’s status. She wears a helmet and mail-coat to take on the celebrated masculine image of a warrior; a position that was accessible to women in medieval Scandinavian society as long as they gained the necessarily masculine traits and became, as Clover states, ‘exceptional’.[27] It is this embodiment of the ‘exceptional woman’ that allows Skadi to take revenge in the first place. Preben Meulengracht Sørensen argues that in Medieval Scandinavian society ‘a woman cannot herself take revenge; she must do so through the agency of a man’.[28] Skadi refutes this. Although she does not repay the death of her father in violence, she succeeds avenging her loss through the humiliation of Loki, whose betrayal led to her father’s demise. On the other hand, Sørensen may be right to say only men can take revenge. Skadi has gained enough masculinity to be perceived as socially male within the Norse gender binary. She takes on the image of a warrior and goes to Asgard to demand compensation to restore her family’s honour. The fact her biological sex is female makes little difference. Clover explains that Medieval Scandinavian society was ‘a world in which a physical woman could become a social man’, and this is what Skadi achieves. [29] In later myths, such as the Lokasenna, she is seen feasting with the gods demonstrating her heightened status considering she is not only female, but a giant as well. Moreover, Skadi lives independently without a male guardian. Although she may replace her father with Niord, the husband she gains as part of her compensation for her father’s death, this marriage fails and Skadi lives alone. According to Clover, Medieval Scandinavian society was ‘a universe in which maleness and femaleness were always negotiable, always up for grabs, always susceptible to ‘conditions’.[30] Snorri’s literature provided a safe space to explore these ideas and push the limits of this system. A system that accepted a certain fluidity between genders, but the condition was always one that supported a transition from female to social male but derided the reverse.

The final and most surprising character in this myth is the goat itself. Although seemingly playing only a minor role, the goat symbolises sexual ambiguity and the transition between genders. The nanny-goat is a female animal with male characteristics such as a beard thus combines masculine and feminine in one form, making it a symbol of gender non-conformity. Beards particularly in Norse literature are symbolic of male vitality.[31] There is a connection, quite literally, between Loki and the goat which implies Loki himself is sexual ambiguous. The goat is the one who removes Loki’s masculinity, and therefore, is the vessel through which Loki transitions from physically male to socially female. Margaret Clunies Ross highlights the ‘symbolic equation here between Loki, who plays at his own castration and has a reputation for sex changing, and the sexually ambivalent nanny-goat with the beard and horns’.[32] John Lindow also suggests the presence of the nanny-goat creates doubt over Loki’s perceived masculinity: ‘if the beard attached to one end of the rope is here a false symbol of masculinity, what are we to make of the genitals attached to the other end?’.[33] It is important to remember that Loki himself ties the goat around his testicles. He chooses this method to make Skadi laugh and does so willingly. This disproves Rooth’s notion that Loki’s gender ambivalence is depicted by ‘the epic course of events’[34] since the feminine display here is Loki’s choice and raises the question: why would Loki willingly sacrifice his own physical and symbolic masculinity? Perhaps he does not. It would only be a sacrifice of masculinity if Loki had already embodied the ideals of a Norse man. Loki famously takes on physical female forms throughout the Prose Edda, such as during Baldur’s death[35] and The Fortification of Asgard[36] myths, meaning his masculinity is already questionable. If Loki is prepared to become physically female, becoming socially female matters little by comparison. Loki, after all, is the trickster god; he will use whatever shape, form, or gender to his advantage.

Clover describes the Norse sexual system as a ‘permeable membrane’[37] and stresses an interest in the ‘fluidity implied by that system’.[38] This is a system in which a person can choose to move between feminine and masculine if they do not care about the social consequences for their actions. As discussed previously with reference to Loki’s position in Snorri’s list of gods, Loki is already socially at the bottom of the male Æsir and his status places him in between them and the female Asyniur. With a status already this low, Loki loses nothing when he reduces his masculinity and embraces his position as a social female. To navigate the Norse universe with such a diminished status, Loki uses everything to his advantage, including embracing his own femininity.

Sexual Deviancy

There are multiple terms in Old Norse relating to sexual deviancy with ergi, nið, ragr, and argr, as the most common. Although their meanings do differ slightly, essentially, they are all insults declaring someone as cowardly, weak, and unmanly due to an association with queer sexuality. Ergi especially encapsulates this idea of weakness being associated with sexual deviance, making it the most fitting term to use in this subsection. It fits within Laqueur’s one sex model aligning courage and strength with the masculine, and weakness with the non-masculine. Evidence of the seriousness of these insults can be found within Icelandic law. Grágás, the oldest Icelandic law text to survive, states that ‘one is entitled to kill on account of these words’. [39] Floke Ström also states that ‘the law prescribes its most severe penalty, outlawry, for anyone who imputes womanly behaviour to another in the form of nið’.[40] The severity of the punishment highlights just how negatively sexual deviancy was viewed. Those guilty could be anything from accused magic users, effeminate men or those taking the receptive position in homosexual intercourse, referred to problematically as ‘passive homosexuality’ by some Norse scholars. Loki is associated with all three of these elements, even exhibiting all at same time in the myth of the Fortification of Asgard.

This myth is found Gylfaginning chapter of the Edda. To prevent a disguised giant builder from completing the fortifications around Asgard and claiming the sun, moon and Freyia as his payment, Loki transformed into a mare to seduce the builder’s horse Svadilfæri, which stopped the completion of the wall. However, ‘Loki had such dealings with Svadilfæri that somewhat later he gave birth to a foal’ called Sleipnir who becomes Odin’s own horse. [41] In this myth Loki is clearly ergi; he uses magic to become a female, is sexually penetrated leading to pregnancy thus proving his unmanliness.

Magic, or seiðr to use the Norse term, is associated with the feminine to the extent that ‘males are forbidden to practice seiðr because of its power to damage their essential, defining qualities as males’, according to Ross, and male gods use ‘its power at the price of moral impairment and symbolic feminisation’. [42] It is this moral impairment that closely links Loki and his ergi nature, raising an interesting debate surrounding this association. Is ergi considered immoral because of its association with Loki, or is Loki considered immoral because of he is ergi? Despite also being a seiðr user, Odin escapes most of its negative association with being ergi. It is not mentioned in the Gylfaginning and Kathleen Self explains Odin ‘is made more masculine through the omission of his performance of seiðr, and the distinction between masculine and feminine is maintained’.[43] It is no coincidence that the Gylfaginning, the part of the Edda that contains the introductions of the gods, omits Odin’s magic use while containing myths that highlight Loki’s morally dubious nature. This is the chapter that sets the expectations and conventions for the rest of the Edda and Snorri makes certain that his audience takes away these specified associations. It is only in the Lokasenna that Odin’s dubious use of feminine magic is addressed by Loki himself. Accusations of sexual deviance of are exchanged between the two of them, yet only appears to have a negative effect on Odin.[44] Ström describes Loki as ‘a shameless ergi’.[45] It is this word ‘shameless’ that is the distinguishing difference between the two gods. Like the previous myth, Loki embraces his dubious gender to his advantage, and it is this acceptance that makes Loki so problematic in the Norse conceptual universe. As von Schnurbein notes “(Loki) represents the "effeminate" man and, for that reason, not necessarily because of his malevolence, is subject to derision and considered evil’.[46] He threatens the gods by undermining their one sex system. By embracing magic and resulting unmanliness, Loki challenges the concept that masculine is the pinnacle gender to which members of both genders should strive to achieve.

Further challenge to this system is seen in Loki through the connection his ergi nature has to femininity, specifically effeminate men. According to Ström, if the term was used to insult a woman, it was ‘virtually synonymous with nymphomania, which was a characteristic as much despised in women as unmanliness was in a man’, meaning its connotation of femininity were only applicable to men. [47] In the Fortification of Asgard myth, Loki performs the ultimate female act by both conceiving and giving birth to an eight-legged horse. A further old Scandinavian law that demonstrates just how transgressive this was: ‘the Norwegian laws already mentioned include insults likening a man to a female animal (berendi) among the words liable to the highest personal recompense. To liken a man to a male animal cost only half as much (halfréttisorð). Accusing a man of having given birth to a child… is added by the Gulathing Law to list of ‘full penalty words’ indicating the severest recompense to be paid’.[48] Both insults are applicable to Loki in this myth, demonstrating how morally corrupt he was in the eyes of Medieval Scandinavian society. The fact that these insults are gendered, with the female insult being the costliest, demonstrates how the one sex system impacted life within Medieval Scandinavian society. Everything comes back to the idea that masculine was not just the desirable gender, but the only gender which could gain honour and respect. Sørensen examines the moral repercussions of this connection: ‘the effect of nið was founded on the accepted complex of ideas about effeminacy and of effeminacy as identical with immoral, despicable nature’.[49] The reason these Norse terms for sexual deviance were so offensive is because of their association with femininity; whether it be seiðr’s connection with women, or the idea that a receptive male in homosexual intercourse was taking the female position. Ström agrees ‘that it is the feminine sexual role which makes allegations of ergi particularly injurious and in fact intolerable for the recipient’.[50] This is another aspect of ergi that Loki fulfils.

It is important to note that ergi and the other terms do not translate into modern ideas of homosexuality, something Brit Solli emphasises: ‘the term ergi must be understood contextually and not as a synonym for homosexuality, as we understand it today’.[51] The term is only applicable to those seen as taking the female position, whereas Clover notes ‘the role of the penetrator is regarded as not only masculine but boastworthy regardless of the sex of the object’.[52] Loki represents the concept of the penetrated male in this myth, considering the conception of Sleipnir, and this is an example of his immoral character. Although Loki’s negotiations and tricks save the Æsir, he is not the hero of the myth. That role goes to Thor who kills the giant with his hypermasculine, physical prowess, thus embodying the image of ultimate masculinity and its valued perception within the one sex system. Loki cannot be the hero because of his queer nature with its connotations of cowardice and corruption. Snorri explains that Loki ‘being afraid’ of the Æsir gods’ threats was the reason he changes shape and gender to seduce Svadilfæri which conveys the link between ergi and cowardice. [53] Sørensen explains how ‘in ancient Iceland consciousness, the idea of passive homosexuality was so closely linked with notions of immorality in general that the sexual sense could serve to express the moral sense’.[54] This means that, despite saving the Æsir, Loki still represents immorality. Snorri states Loki ‘is responsible for most evil’ in this myth, even though his only offense was to give poor advice. [55] His supposed evilness therefore comes from the queer gender inversion employed to fix his mistake.

Although not a hero, Loki is still powerful despite deflating his status by transgressing against the Norse gender system. In fact, it is this very transition that gives him power. Anthony Adams acknowledges that ‘Loki represents a type of imprecise, androgynous (or even hermaphroditic), yet still potent sexuality that is entirely at odds with the simpler, overt masculinity of the sagas’.[56] This conflict between Loki’s transgressive position as a queer character and the hyper masculine gives Loki power despite his low status. As much as they distrust Loki, the Æsir need him. The very fact they allow Loki to live amongst them demonstrates how important his transgressive abilities are, especially those associated with ergi such as magic. Soli reasons that ‘Seiðr must have been so important for the maintenance of society that the queerness of its practice had to be accepted as a cosmological necessity’.[57] Therefore, all the Æsir are guilty of engaging with queerness through their tolerance of Loki but only when he can be used to meet their needs.

When it comes to summarizing Loki’s sexual deviance, Ross best expresses how Loki and Odin ‘make good use of their ‘weakness’ (ergi) which allows them access to resources or patterns of behaviour normally regarded as female and hence unavailable to male beings’.[58] By embracing his ‘unmanly’ nature, Loki takes advantage of areas of power restricted from the higher status masculine gods and suppressed within female gods. Unlike Odin, whose ergi is ‘undoubtedly a burden’ (Ström), Loki does not care about the social (or any) consequences of his actions as long as he can use them to survive within the one sex system he simultaneously transgresses against. [59]

Race

Loki’s resistance to fitting within the gender binary is paralleled in his resistance to fit within the mythological race binary between the gods and the giants. His very existence bridges these two opposing races. According to Snorri, Loki is the ‘son of the giant Farbauti. Laufey or Nal is his mother’,[60] the latter Ross theorises was ‘presumably among the Æsir’.[61] This dual heritage unites the two enemy races within one being, meaning Loki is neither giant nor god but an unconventional combination of both.[62] Ross goes on to explain that this means Loki ‘is the embodiment of the most tabooed social relationship in Medieval Scandinavian society’.[63] Existing in between these races, Loki brings together the cultural aspects of both races despite their clear binary differences. By examining the threat Loki’s heritage presents amongst the gods and its connections to femininity, it is possible to see how Loki’s lack of conformity to the Norse racial binary demonstrates his resistance to the gender binary system too.

Loki is not only a product of a taboo relationship, but the participator in one too. From his relationship with the giantess Angrboda, Loki has three children who take the monstrous forms of Fenris, a giant wolf, Iormungand, a giant serpent, and Hel with her half dead body.[64] The gods ‘felt evil was all to be expected of them’[65] and imprison Loki’s children ‘because of their mother’s nature, but still worse because of their father’s’.[66] Despite possibly being half Æsir, it is Loki’s lineage the gods fear more than the full giant blood of Angrboda. This is because he embodies the union of two races whose conflict makes up a key aspect the Norse conceptual fabric. A typical trope of Norse mythology involves the morally superior Æsir gods defeating the monstrous giants, thus maintaining their system of ideals throughout the realms. Even when there is an exception to this, such as Thor being out-witted by Utgarda-Loki, the story still centres around the opposition of gods and giants, not their union as Loki represents. [67]

Loki does not fit within the usual racial structure of the society within Norse mythology. Ross describes Loki as an ‘anomalous being’[68] and notes how ‘the myth of Loki and his offspring indicates the kinds of disorders the gods oppose is not only ‘out there’ in the other world they associate with giants but exists within their own society’.[69] Loki is the product of two races that should be always in contrasting conflict, not uniting sexually, and even his presence amongst the Æsir presents a threat to their strict structures that maintain order. The very fact Loki exists undermines the whole system which sees gods and giants as opposite and opposing binaries.

One reason why the gods and giants live in such opposition is due to their opposing gender systems. While the gods live within a one sex model where hyper masculinity is the true gender and all others are inadequate, the giants’ system contrasts this. They fall within Clover’s ‘rainbow coalition’ making them ‘other’ to the Æsir. [70] Ross explains the connection between giants and femininity as a result of both concepts being treated as ‘other’ and ‘so the combination of the category ‘giant’ with the category ‘female’ represents an intensification of the nation of otherness and therefore an intensification of the association of danger with it’.[71] This adds to the threat of Loki existing within the Æsir gender system. Not only does he embody femininity through his non-binary gender and sexually deviant nature, his giant blood also adds to his innate gender inversion. Self also examines the connection between race and gender: ‘the binary of the gods and the giants echoes the male/female divide with the giantesses appearing more masculine at times and certain giants having a malleable gender’.[72] Skadi is example of this, but her gender is malleable in a way that is in tune with the Æsir one sex system meaning she is the only giant who is welcomed into their society.

Loki also uses his divine heritage as a way of embracing aspects of his femininity. Ross points out that Loki is ‘always referred to as Loki Laufeyjarson (which) indicates the precedence of his divine kinship through his mother’s family’.[73] While it does make sense that Loki would want to be associated with the parent with the higher status and assimilate with the gods by emphasising his racial connection to them, this still transgresses against the Norse patronymic system. By taking a matronymic surname in place of his father’s name, Loki is bestowing an honour usually reserved for men to his mother. This demonstrates his willingness to embrace femininity if it results in increasing his status amongst the gods, therefore we again see Loki using typically eschewed femininity to his advantage.

Although treated as an anomaly, Loki is not the only member counted among the Æsir to have giant ancestry. Both Tyr and Odin also are descended from giants; a fact the Gylfaginning conveniently forgets during their introductions. However, it is no coincidence that both these gods are hypermasculine war gods which places them firmly at the top of the one sex model. Therefore, their desirable masculine traits compensate for their undesirable, unorthodox lineage. Loki’s lack of conformity within the gender system is what makes his mix heritage a problem for the rest of the gods. By not fitting within their system of gender, his race is just another aspect that makes him a threat. Nevertheless, as with his queer nature, the gods will often use Loki’s liminal position between the two races. Rooth notes that Loki’s ‘role is frequently that of mediator’[74] between the gods and the giants but John McKinnell also notes his ‘special role is as a traitor’.[75] The gods depend on Loki’s nonconformity to navigate situations which their strict morality prevents them engaging with, such as magic and interrace relations, and still hold the very aspects of Loki that they need against him. McKinnell reasons that Loki shares these undesirable yet essential traits with other gods but ‘unlike the others makes no attempt to hide them’.[76] This is what makes Loki a true threat to the gods. It is not so much his engagement with taboo practices, but his openness. His refusal to hide his transgressive nature highlights the hypocrisy within the gods and flaws within their binary systems they try to hide.

Conclusion

Loki in the Prose Edda is clearly a transgressive character who resists categorization within the concept on the one sex model. His race, sexual deviance, and complete disregard to gender binaries combine to create a male entity who openly and happily engages with femininity without shame or fear of the social ramifications. However, while modern terms such as gender non-binary, or genderfluid may seem applicable to him, it is important to remember that the gods of the Edda are not characters but mythological concepts, with Thor embodying the concept of strength, Odin wisdom and so on. Loki’s mythology offers a safe arena in which cultural taboos can be broken and their consequences examined. Therefore, he does not have a gender identity in the same sense a modern fictional character has, so cannot identify as gender non-binary or fluid. As A. S. Byatt states mythological figures ‘do not have psychology.... They have attributes’.[77] Loki is instead a vessel through which the concept of gender binary within a one gender system can be explored and ultimately critiqued and punished. As the antagonist of the Edda, he brings forth the destruction of the gods. Loki destroys not only the Æsir hierarchy but the entire Norse universe during Ragnarök.[78] The Norse universe is one that relied on these binaries to exist and collapses once they are destroyed. The concept of Loki cannot survive in the one sex model, and the model cannot last with Loki in it. However, if Loki is removed from this gender system and placed within a modern one, his role and his outcome is entirely different.

Chapter Two: Loki in Marvel

Prior to the 2014 release of Loki: Agent of Asgard, a new comic series which centred around the reimagined, teenage version of the trickster god, the writer Al Ewing confirmed that Loki would indeed be a queer character who would switch between genders.[79] This came as no surprise to many in Loki’s fanbase since evidence of Loki’s queerness can be found throughout his history in Marvel comics. Examples of this include; flirting with a male teammate in Young Avengers Vol 2,[80] the ambiguous sexuality that comes with possessing a female body in Dark Reign[81], to even his first appearance in the modern era of comics in Journey into Mystery #85[82] where he is given a feminised, hourglass figure in contrast to the broad masculine figure of his counterpart Thor. (Fig. 1) However, in his own comic book, Loki’s character could now embrace his queerness and his gender fluidity in his own body much more openly than before.

The recent 2019 young adult novel Loki: Where Mischief Lies written by Mackenzi Lee will be examined alongside this comic. Like the comic, this novel also features an openly queer and gender non-conforming Loki. Both versions of this character face similar problems as they struggle to find their place within the wider narratives of the Marvel universe, especially concerning where they fit within the gender structures and heteronormative worlds and their roles as presumed antagonists.

Unlike the Loki found in the Edda, both Loki in Agent of Asgard and Loki in Where Mischief Lies are fully fleshed out characters with their own identities and motives, especially now they are the protagonists of their stories rather than just antagonists used to highlight the heroism of their adversaries. As a result of their enhanced characterisation, they become representative of genderfluid and non-binary people. Marvel’s acceptance of queer characters is something to be commended. As Mathew McAllister notes ‘comics mirror a pluralistic society’, therefore Marvel presents a fictional society that reflects our own. [83] Underneath stories of gods and heroes, the two texts explore queer gender identities and what it means to exist as ‘other’. This chapter will explore this by analysing how gender non-binarism, transgression and identity feature within Ewing’s and Lee’s stories.

Genderfluidity

By reimagining the mythological concept of Loki in a modern society, he is removed from the one sex model Laqueur suggests for Norse literature and placed in a new gender system. This new system, according to a contemporary critical lens using Butler’s theory of gender, is one based on the notion of performative gender and therefore allows for fluidity between them. However, the concept of gender being directly related to biological sex along with ideas of masculine and feminine being separate and opposite are still prevalent in most societies. Agent of Asgard is set within a society reflective of our own. The comic takes place across Earth and Asgard within their similar performative gender systems.

Where Mischief Lies is slightly more complicated, taking place across two very different societies: the ‘idyllic paradise’ of Asgard and nineteenth-century London. [84] Gender binaries are strictly upheld in the latter, following a system in which women are perceived as inferior to men to such an extent that even wearing trousers is seen as being transgressive, and where homosexuality is criminalised. [85] Asgard contrastingly does not have ‘such a limited view of sex’, instead it is seemingly a society in which all genders are treated equally. [86] Yet, there still is a binary system in place that echoes the one sex model in the Edda. Rather than between male and female, it is between sorcerers and warriors with the latter viewed as the desirable trait and the other as inferior. Loki is encouraged to hide is magical ability and ‘dedicated himself to becoming a warrior’[87] because ‘no one wanted a sorcerer for a king’.[88] There is still a gendered aspect to this system, however. Similarly to the Edda, magic is closely associated with women, with the only magic users in the novel being female (Frigga, Karnilla, Amora) or Loki who is feminised. Whether magic is viewed as inferior because of this feminine association is unclear. Reflective of the one sex model found in the Edda, background female characters who pursue hypermasculine warrior lifestyles, Sif and the Valkyries, are praised while magicians are viewed with fear and suspicion. To observe Lee’s Loki in this system, and Ewing’s Loki in the Agent of Asgard system, this section will examine how the characters exists as both genders, how this is physically presented and how this disrupts each of their gender systems.

Although Loki changes genders several times throughout the comic series, the term non-binary or genderfluid is never used. Nancy Hirschmann identifies the issue of ‘what queer… individuals are called, by themselves and by others,’ as a ‘political, ontological, and epistemological issue’, however, this does not negate from the validity of an identity just because it is not labelled nor means it is not applicable. [89] The first example of Loki changing gender is in issue #2 where Loki takes the pseudonym ‘Trixie’ to infiltrate a heist. Although it could be argued that Loki only becomes female because it is a necessary disguise, as Rooth argues in the Edda, Loki explains that his illusion magic would not have worked in that situation. [90] ‘I am always myself,’ Loki states explaining that being female is no different from being male. [91] This is best demonstrated by a single borderless panel depicting Loki shifting between female and male. (Fig. 2) The lack of borders symbolises the lack of boundaries between Loki’s genders and the single panel means both genders are contained in a singular space as both genders exist within Loki. Panelling in issue #14 again demonstrates how Loki regards shifting between genders. (Fig. 3) The three panels picture male Loki putting on a shirt as he changes to female as if changing gender is no different from changing a shirt. According to Sandra Bem, an individual can contain both female and male traits, which means Loki exists as both female and male simultaneously; changing genders therefore is not an artificial act made capable through his magic abilities and is not done just because it is convenient for the situation. [92]

The most obvious evidence of Loki’s genderfluidity in Where Mischief Lies takes place in Victorian London, due to the scrutiny Loki faces when removed from the supposedly gender equal Asgardian society. Theo, trying to find out Loki’s sexual orientation, asks his preferred gender which Loki misinterprets and answers ‘I feel equally comfortable as either’.[93] When Theo argues that this is again simply because of Loki’s magical abilities allowing him to change appearance, Loki states ‘I don’t change my gender. I exist as both’.[94] The confusion between gender and sexuality highlights, according to Jonathan Alexander, how ‘sexuality intersects with and complicates are understanding of gender’ and further demonstrates the difference between the two gender systems of Asgard and Earth. [95] Loki’s misunderstanding conveys how gender and sexuality intersect so frequently on Asgard that he cannot separate them, while Theo is accepting of homosexuality yet struggles to understand genderfluidity. This is perhaps because Loki has to appear more masculine during his time in London, ‘he missed his heeled boots’, although, he still defends his feminine identity. [96] Whenever feminine terms are applied to him, Loki accepts them: ‘“It’s the feminine version of enchanter.” “Does that matter?”’.[97] The setting of Victorian era with its stricter gender binaries is effective for demonstrating the ‘the arbitrariness of the Western gender system’ through Loki’s critiques of it. [98] By framing these critiques as being ‘small-minded’ and associating them with conservative Victorians, Lee helps to validate queerness and genderfluidity, reflecting the diversity of her young adult audience. [99]

The visual medium of the comic means appearance becomes key for demonstrating Loki’s genderfluidity in Agent of Asgard and consequently meaning his genderfluidity is always present through the art of the comic. Like in his very first issue in Journey into Mystery, Loki’s male appearance is feminised. Black nail varnish, a fur lined coat and V-necked tunic all hint at his feminine nature while scaled armour and greaves are typically more masculine. (Fig. 4) The fact that both male and female aspects exist in one costume demonstrates how Loki is consistently both genders, especially because the costume does not change when Loki’ changes from male to female, or even a fox. (Fig. 5) Terrence R. Wandtke notes how a superhero’s costume is ‘a marker of self’, thus Loki’s androgynous costume represents his genderfluid self. [100] This also reflects Loki’s queerness in terms of his sexual attraction to both genders which is not particularly explored in depth in the comic. Aaron Blashill and Kimberly Powlishta refer to ‘cross-gendered characteristics’ in homosexual people which Loki’s costume captures, demonstrating not only is genderfluidity but his homosexual orientation as well. [101] It is also notable that Loki’s physical female appearance is very similar to his male. In the example of ‘Trixie’ in #2, the only difference between the male and female Loki is make-up and hair length. This accurately reflects how potential genderfluid readers use cosmetics to reflect their own transitions between genders thus proving how Loki becomes a representative for genderfluidity in literature.

Where Mischief Lies also relies on appearance to demonstrate Loki’s lack of gender boundaries. This is because, unlike Agent of Asgard Lee’s Loki never becomes completely female meaning clothing is often used to symbolise his innate femininity. Loki’s femininity is introduced when the novel opens with Loki worrying about his appearance. These concerns focus on aspects typically associated with feminine appearance, such as his love of ‘a bit of sparkle’[102] and his boots which ‘made him feel like doing a strut down the middle of the hall …(and had) heels as long and thin as the knives he kept up his sleeves’.[103] This evokes a feminine image of Loki with ‘strut’ in particular conjuring the queer image of a drag queen. The simile of knives as heels is particularly demonstrative of Loki’s gender fluidity, combining the feminine heel and weapons with their connection to masculinity within the hypermasculine Asgardian gender system. The use of clothes further validates the performative aspect of gender. Although Loki is biologically male, his choice of clothes demonstrates the feminine image he wishes to portray to the world. Lisa Walker expresses how the whole concept of performative gender relies on an individual performing the gender they think they are; Loki’s performance suggests he views himself as both male and female. [104]

A further way to examine Loki’s queer nature is to explore how it exists in contrast to the gender system in which it is found. Although the performative system in Agent of Asgard is in theory accepting of genderfluidity, there are still queerphobic elements that demonstrate that strict binary views of gender still exist. Loki is referred to as a ‘precious little girl-child’[105] and a ‘preening half-a-man’.[106] These both use Loki’s feminine gender as an insult, suggesting either the idea of femininity being a weakness, or that queerness is ‘viewed negatively due to a presumption … (of) cross-gendered characteristics’.[107] However, these are the only two queerphobic instances in a comic that is overall thoroughly embracing of Loki’s genderfluid identity. While some commentators on comics, such as Norma Pecora[108] and Carol Stabile[109], criticise the innate sexism in the comics of the 1990s, Marvel has made a substantial effort to improve female and queer representation in recent years, including recently featuring a pride parade consisting entirely of their LGBTQ+ characters, including Loki.[110] McAllister notes the power the comic book has ‘to both legitimate dominant social values and provide an avenue for cultural criticism’, therefore highlighting the importance of representation in comics and providing an accepting society to legitimise their presence both on and off the page. [111]A comic being void of any criticism of queer people would not accurately represent the prejudices LGBTQ+ people face, justifying the use of limited queerphobic remarks. Therefore, even in a fictional society that recognises the performativity of gender and provides a system Loki should exist easily within, the lingering prejudices of gender binaries means Loki is still seen as transgressive and, like the Edda, his queerness is used to insult him.

Despite Where Mischief Lies featuring two distinct binary systems, one sentiment combines how Loki transgresses both: ‘Be the witch’.[112] This sentence, which is not only repeated throughout the novel, but concludes it, brings together the idea of transgressing the gender binary of Victorian London as well as the sorcerer/warrior binary of Asgard. By being transgressive, Loki is a threat to both systems and the social hierarchies they uphold. In term of gender binaries, Hirschmann suggests that ‘those boundaries may be established by cultural practices as a way to protect social hierarchies’.[113] Victorian London has this system to defend the patriarchy from threats of female power. This can be seen from the character of Mrs Sharp whose masculine trousers brings her into conflict with the male authority, ‘“Why do you try so hard to look like a man, Mrs Sharp?”’,[114] and the use of ‘witch’[115] to insult Loki due to its association with powerful women. Loki’s presence as someone who openly embraces multiple genders threatens the rigid binary that protects the patriarchal system, resulting in his femininity being ridiculed due to the anxiety created from its threat to male power.

Within terms of the hierarchy system of Lee’s Asgard, in which magic is seen as inferior to warrior prowess, Loki transgresses through his magical ability rather than his genderfluidity. While Thor’s expression of physical power is praised, Loki’s magical power is punished or regarded with fear: ‘His father was afraid of him. Afraid of his power’.[116] Magic users who remain subservient, ‘Karnilla… Odin’s royal sorceress, stood like a soldier’[117] and Frigga, Odin’s wife ‘who supported him’,[118] are accepted in Asgardian society, while those who transgress, like Amora who is ‘too powerful to control’, are banished. [119] There is an obvious gendered narrative reflecting a woman’s place in society; her power must be subservient to the masculine ruler or she will be rejected. The concept of the witch, being a feminine magic wielder who exists outside of society, accurately reflects how Loki does not fit within either binary of the two systems found in Lee’s novel. For much of the novel, Loki struggles to be the subservient sorcerer Asgardian society desires him to be, but ultimately decides to embrace his transgressive nature and ‘be the witch’.[120]

Existing as Queer

In both texts, Loki exists as an outsider to the societies he seeks acceptance within. Although his queer identity and orientation are never directly cited as the reasons for this ostracization, they are emblematic of why he is never accepted. In Agent of Asgard, Loki’s genderfluidity translates into to a wider desire to resist being categorized as either a villain or hero, while shame over his magical abilities in Where Mischief Lies reflects a struggle to accept homosexual attraction. Loki’s othering as a queer character will be explored by examining how it is reflected through other aspects of his characterisation.

Categorization is expressed in Agent of Asgard through the repeated metaphor of boxes and cages. They symbolise a conformity with conflicts with Loki’s fluid and transgressive nature. Loki connects this idea of identity and boxes, ‘I am my own and will not sit long in any box built for me’, demonstrating how being his own means being innately transgressive. [121] Throughout the narrative Loki is trying to prove he is no longer the archetypal villain he had been for most of Marvel’s history. He will no longer fit neatly into that category nor the one of hero, instead existing between the two as an antihero. Like with gender, Loki does not fit in either binary meaning the threat of literal imprisonment is used to symbolise conformity as either a villain or as a single gender. At the climax of the novel when Asgard goes to war with Hel, Loki does not choose either of the binaries presented to him, stating ‘I don’t do sides’ in a panel that heavily shades half his face. [122] (Fig. 6) The combination of both dark and light colouring creates the impression that Loki is neither entirely good nor evil, instead he is both and neither; he has found a way to exist outside the binary of good and evil, reflective of his ability to exist outside a gender binary. Binary gender as being restive and box-like is something explored by Jennifer Nye: ‘the range of human possibilities extends far beyond that recognized by the gender box.’[123] Loki’s resistance to imprisonments represents a desire to break free of restrictive gender categories.

The concept of the gender box goes beyond just gender identity to include sexual orientation. Nye definition of the masculine gender box relies on the assumption that ‘if your sex is male, your gender is masculine, and you are sexually attracted to women’.[124] Of course this excludes anyone who is not a cisgender heterosexual, but it does demonstrate the traditional expectations of gender and sexual orientation, therefore making anyone who exists outside the gender box automatically an outsider. In Where Mischief Lies Loki and Theo’s homosexual feelings for each other mark them as outsiders in Victorian London where Theo has been previously imprisoned for being ‘a boy who likes boys’.[125] This is something Loki instantly relates to as ‘he knew what it was to be cast out and unwanted and taunted for the fabric you were stitched from.[126] While Asgard, according to Loki, is accepting of homosexuality, it is possible to map the clichés of closeted homosexuality onto Loki’s struggle to hide his magical abilities: ‘wriggling with a shame he didn’t understand, before his mother finally came and explained that it would be best if he did not use the magic’.[127] Unintentionally paralleling the Edda, magic becomes an othering force like seiðr in Norse literature. Like Theo, there is also a threat of punishment for this othering, which Amora experiences in her banishment. This connection between Theo and Loki being forced to hide who they really are leads to the shared sentiment: ‘I wish I could make your world want you’.[128] Existing as queer means embracing what makes you other. Something both Theo and Loki accept by the end of the novel with Theo kissing Loki[129] and Loki using his magic to save Asgard.[130]

No matter how accepting the society of Asgard is in Agent of Asgard or Where Mischief Lie’s, there is always the tendency to cast anyone who transgresses traditional views of gender and sexuality as a villain. Mark LaPointe and Meredith Li-Vollmer argue that ‘gender transgression may also cast doubt on a person’s competence, social acceptability, and morality’ in cultures that still hold on to ideas of ‘naturalized constructions of gender’. [131] Consequently, if Loki is to stay true to his own identity, he must exist outside of society, often causing conflict with it that presents him as antagonistic.

Identity

Loki’s exploration of his identity is a key theme not just in these two texts, but in the wider Marvel universe as well, with rumours an upcoming television series will also delve into this.[132] A fundamental aspect of Loki’s identity is of course his gender but this is just one aspect of many that result in Loki finding conflict between his own identity and the societies he longs to belong to. The way Loki is othered from society, how he exists as an othered being and his acceptance of his othered position will be examined in this section.

In Agent of Asgard Loki becomes increasingly othered throughout the comic. His position in this society has always been precarious; like in the Edda, Loki is racially other to the Asgardians[133] which is used to test his loyalties: ‘your race and mine are old allies’.[134] Although this is unsuccessful ‘We gave you a family’, ‘Yes, but I already have one of those’, Loki’s heritage is other enough for this to pose a threat, at least in the eyes of those within Asgardian society. [135] Loki begins the comic desperately trying to earn a place in this society by atoning for his crimes of the past, trading ‘new legends for old’,[136] but by issue #10 Loki’s secret of killing his child self, ‘the crime that will not be forgiven’,[137] is revealed leading to ostracization from Asgardian society. Loki consequently loses a key element of his identity: ‘I’m no longer an Asgardian’.[138] This concept of losable racial identity is not unlike the concept of losable masculinity in the Edda because Loki must meet the heroic requirements of Asgard or be cast out. Adam Green also argues that ‘identity as an ongoing social process marked by multiplicity, instability, and flux’ therefore can be lost or gained. [139] Loki’s exile ultimately frees him from the constraints of a society he was constantly in conflict with. Exile came because of Loki’s inability to live up to the expectation of Asgardian identity, with ideals of heroism that did not coincide with the trickster elements of Loki’s identity. While genderfluidity does not directly violate the concept of Asgardian identity, it is an expression of Loki’s malleable character that contrasts with the traditional image of the heroes of Asgard. Now he is separated from this society, Loki is finally free to explore his identity without restraints.

In Where Mischief Lies, Loki’s othering comes from his inability to find his place in a society that only values qualities such as physical strength and a warrior prowess. Like Ewing’s Loki, Lee’s is also desperate to find acceptance in society, ‘working to be a better soldier, a better sorcerer, a better prince’, with little success. Loki is aware of his otherness. [140] He is worried that magic will ‘make (him) unnatural’, and Amora’s banishment demonstrates how dangerous otherness is in Asgardian society. [141] Alexander argues that ‘our identities are shaped and communicated through a variety of interesting social processes’, therefore this othering would have significantly impacted Loki’s identity, particularly his gender. [142] Asgard is supposedly accepting of Loki’s genderfluidity, yet he is the only genderfluid character found in Asgard and his femininity associates him with the otherness of magic as the only male user. The concept of otherness in this society consequently forces conformity on Loki in his desperation to be accepted. Paradoxically, it is when Loki enters the more oppressive society of Victorian London that he realises his identity cannot be suppressed; to be true to himself, he must exist as other in Asgardian society.

Loki’s acceptance of his place as an outsider to Asgardian society is central to the development of his identity as a transgressive character. By being ostracised from his society, Loki no longer needs to fulfil any expectations apart from his own. This allegiance to nobody but himself if something that has been part of Loki throughout his history in Marvel comics. Ewing turns the idea of Loki’s selfishness into an idea of self-preservation of an identity othered by Asgardian society. In Agent of Asgard’s introduction Ewing cites the iconic panel from Thor #353, which Odin’s battle cry is ‘For Asgard!’, Thor’s is ‘For Midgard!’, while Loki’s is ‘For Myself!’. [143] (Fig. 7) While humorous, Ewing argues that ‘when your self is a thing you have to fight the very cosmos to decide… it’s almost kind of… heroic?’, demonstrating how Loki’s perceived selfishness is evidence of him fighting to preserve his own identity. [144] To be true his identity, Loki must exist outside the society he had been trying to appease: ‘I probably shouldn’t care what they think, then, should I?’.[145] Agent of Asgard is ‘a comic about being For Yourself’, about existing without apologising. [146] Loki’s genderfluidity is just one aspect of his identity that causes him to transgress against the society he tries to exist within. Rather than sacrifice his identity to be accepted by others, Loki choses to exist as an outsider.

Loki in Where Mischief Lies also accepts his place as being an outsider. He tries to find his identity through his position in society, by trying to prove that he is a worthy contender for the throne. However, throughout the novel Loki is forced to question his own sense of identity due to the way others perceive him: ‘He did not know who he was. Everyone knew but him’.[147] It is only at the very end of the novel once Loki finds out he will never be king that he accepts that he will always exist as other to his society, choosing to ‘serve no man but himself, no heart but his own’.[148] Forming an identity othered from society, Loki gives in to fulfilling the expectations of others, becoming ‘the self-serving God of Chaos’, but is also free to be true to himself. [149] This impacts Loki’s gender identity because he no longer needs to worry about what others think of him, leaving him free to explore his gender to its full extent.

The final, and most important, aspect of identity both texts explore is self-acceptance. After revealing that the antagonist of the narrative was really himself, Loki embraces him and tells him ‘it’s all right’, meaning Loki finally accepts himself and no longer strives to conform to become something he is not. [150] Lee’s Loki also accepts himself. While on Earth he meets other people othered by their societies, such as Mrs Sharp and Theo, and it is through their friendship that Loki learns to accept his otherness. Theo and Loki are both othered in their own societies, so instead find acceptance in each other, sharing a ‘soft kiss’.[151] Through this action, Theo accepts his sexual orientation and Loki accepts that he can receive affection without having to meet the impossible standards society expects of him. Self-acceptance is key to embracing one’s own identity, especially transgressive gender identities such as genderfluidity. McAllister highlights the importance of comic books and ‘the degree of cultural argument they permit or encourage’ meaning that Loki becomes a figure representative of genderfluid identities and validates their presence not just in literature, but in the world of the reader as well. [152] Therefore, it is critical that Loki in both texts learns to accept himself and his entire self. Not just as a genderfluid individual, but all aspects of his identity that makes him a fully fleshed character and not just a symbol of deviance as Loki in the Edda is.

Conclusion

The two texts explore Loki, not as simply a figure representative of transgressive gender, but as a character with a genderfluid identity that brings both internal and external conflict. Although Loki’s genderfluidity is an essential part of his identity, these texts prove that he is more than just his gender and that gender is more than just one aspect of his identity; it is a foundation in his otherness and symbolic of the malleability of his personality. The comic book industry was once notoriously slow to adapt to changes in the treatment of gender, with stories revolving around a hypermasculine hero protecting the delicate female, is now significantly more embracing of social progress. Loki is just one of a growing number of characters from LGBTQ+ backgrounds, yet he is one of the oldest to exist in Marvel comics. This is testament to the gender ambiguous legacy that the original mythological Loki left behind. The mythological Loki’s transgressive approach to gender reverberated across centuries, until it reached this modern medium where it could be expressed fully.

(Fig.1) Stan Lee et al, Journey into Mystery (New York: Marvel Comics, 1952). #85

(Fig.3) Loki: Agent of Asgard #14

(Fig.2) Al Ewing et al, Loki: Agent of Asgard (New York: Marvel Comics, 2020), #2

(Fig.4) Loki: Agent of Asgard #2 Jamie McKelvie Cover Variant

(Fig.5) Loki: Agent of Asgard #5

(Fig.6) Loki: Agent of Asgard #16

(Fig.7) Walter Simonson, Thor (New York: Marvel Comics, 1966). #353

Conclusion

‘Loki makes the world more interesting but less safe.’[153]

When Neil Gaiman wrote this in Norse Mythology, he was referring to the threat Loki poses to the gods of Asgard as the bringer of their downfall. However, I think that there is another way to interpret this. A world made ‘less safe’ does not necessarily mean a world of danger, but a world less conservative, less static, where diversity makes the world more interesting. To help this world come into being, it first must be accepted. This means not only in wider society but in popular culture too, by finding its way onto our screens and pages.

While this dissertation has praised Marvel’s efforts to increase diversity in its comic books, the Marvel Cinematic Universe is far behind its comic counterpart, especially in queer representation. At the forefront of this fight for LGBTQ+ depiction is the Thor franchise, with Tessa Thompson’s Valkyrie being the first, although unconfirmed, LGBTQ+ character originating in Thor Ragnarok.[154] Thor: Love and Thunder is also rumoured to introduce a transgender character and, while Loki’s place in this film is yet to be confirmed, there are again rumours he may be genderfluid in his upcoming TV series. There has always been controversy surrounding Marvel’s queer diversity, such as Brazil recently banning a Young Avengers comic due to a same-sex kiss being featured in it, which is the reason why Marvel’s mainstream movies have been so slow to increase representation in comparison to its comics. [155] However, the fact that it raises such controversy only heightens the need for greater representation.

Rick Roidan, during his acceptance speech at the 2016 Stonewall Awards, expressed the how important it is for ‘LGBTQ kids see themselves reflected and valued in the larger world of mass media’.[156] He too identified the connection between genderfluidity and Loki with his genderfluid character Alex Fierro being the child of Loki in Magnus Chase and the Gods of Asgard. Another example of mythology being repurposed for a modern audience, it furthers Abram’s argument that mythology will change to meet what is required of it. It also conveys the importance of representation that goes deeper than appearing in mass media, with these LGBTQ+ kids being connected to something even more engrained in culture.

The target audience of the modern texts explored in this dissertation are mainly young adults, many of whom will be beginning to explore their sexual identities and orientations. By queer reading mythology then using this as a basis for representation, queer identity is established as something validated by its presence in the past and position in popular culture.

Bibliography

Abram, Christopher, Myths of the Pagan North: the Gods of the Norsemen (London: Continuum, 2011)