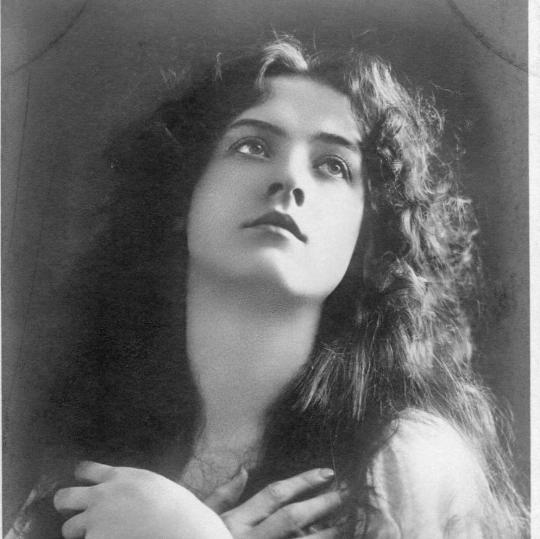

#arguably one of the best castings for a character in cinema history

Text

we all love how much of a zesty fruitloop shang tsung is in mk1,,,

but let's not forget who started that whole zesty persona:

#he was the blueprint#if you don't know who this is im sorry#there has never been a better casting for a single video game character since this movie#arguably one of the best castings for a character in cinema history#carry hiroyuki tagawa#shang tsung#mortal kombat movie (1995)#mortal kombat 1#mk1#mk1 shang tsung#mortal kombat

197 notes

·

View notes

Text

Propaganda

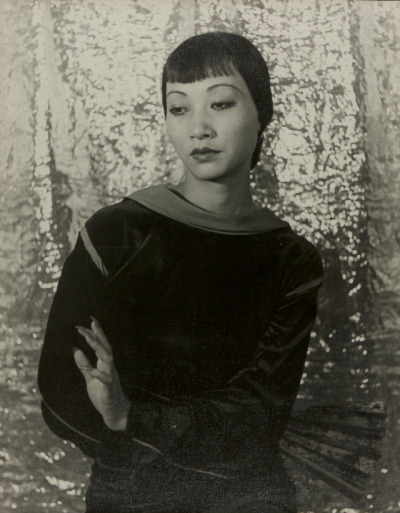

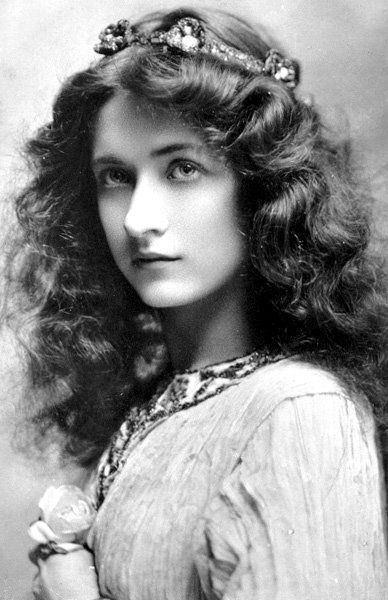

Anna May Wong (The Thief of Bagdad, Shanghai Express)—Wong was the first Chinese American movie star, arguably the first Asian woman to make it big in American films. Though the racism of the time often forced her into stereotypical roles, awarded Asian leading roles to white actors in yellowface, and prohibited on-screen romance between actors of different races, she delivered powerful and memorable performances. When Hollywood bigotry got to be too much, she made movies in Europe. Wong was intellectually curious, a fashion icon, and a strong advocate for authentic Asian representation in cinema. And, notably for the purposes of this tournament, absolutely gorgeous.

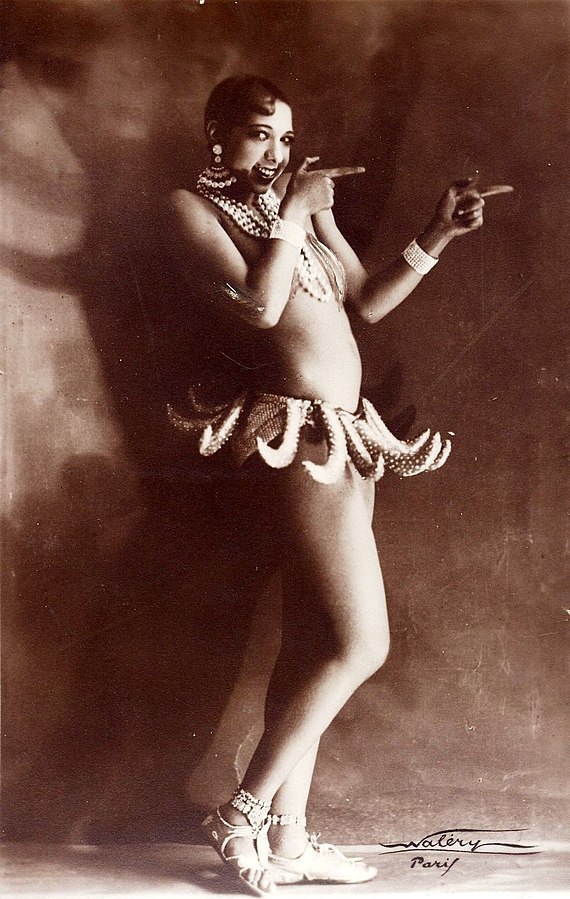

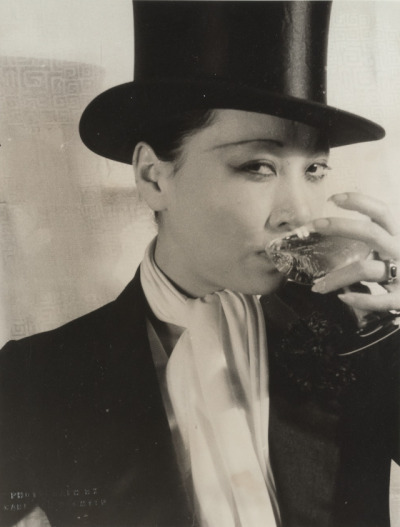

Josephine Baker (The Siren of the Tropics, ZouZou)— Josephine Baker was an American born actress, singer, and utter icon of the period, creating the 1920s banana skirt look. She was the first black woman to star in a major motion film. She fought in the French resistance in WWII, given a Legion of Honour, as well as refusing to perform in segregated theatres in the US. She was bisexual, a fighter, and overall an absolutely incredible woman as well as being extremely attractive.

This is round 6 of the tournament. All other polls in this bracket can be found here. Please reblog with further support of your beloved hot sexy vintage woman.

[additional propaganda submitted under the cut.]

Anna May Wong propaganda:

"She so so gorgeous!! Due to Hollywood racism she was pretty limited in the roles she got to play but even despite that she’s so captivating and deserves to be known as a leading lady in her own right!! When she’s on screen in Shanghai Express I can’t look away, which is saying something because Marlene Dietrich is also in that film."

"SHE IS ON THE BACK OF QUARTERS also she was very smart and able to speak multiple languages and is a fashion icon on top of the acting/singing"

"Paved the way for Asian American actresses AND TOTAL HOTTIE!!! She broke boundaries and made it her mission to smash stereotypes of Asian women in western film (at the time, they were either protrayed them as delicate and demure or scheming and evil). In 1951, she made history with her television show The Gallery of Madame Liu-Tsong, the first-ever U.S. television show starring an Asian-American series lead (paraphrased from Wikipedia). Also, never married and rumor has it that she had an affair with Marlene Dietrich. We love a Controversial Queen!"

"She's got that Silent Era smoulder™ that I think transcends the very stereotypical roles in which she was typically cast. Also looks very hot smouldering opposite Marlene Dietrich in "Shanghai Express"; there's kiss energy there."

"Hot as hell and chronically overlooked in her time, she's truly phenomenal and absolutely stunning"

"A story of stardom unavoidably marred by Hollywood racism; Wong's early-career hype was significantly derailed by the higher-up's reluctance to have an Asian lead, and things only got worse when the Hayes code came down and she suddenly *couldn't* be shown kissing a white man--even if that white man was in yellowface. After being shoved into the Dragon Lady role one too many times, she took her career to other continents for many years. Still, she came back to America eventually, being more selective in her roles, speaking out against Asian stereotypes, and in the midst of all of this finding the time to be awarded both the title of "World's Best Dressed Woman" by Mayfair Mannequin Society of New York and an honorary doctorate by Peking University."

"Incredible beauty, incredible actress, incredible story."

"-flapper fashion ICON. look up her fits please <3 -rumors of lesbianism due to her Close Friendships with marlene dietrich & cecil cunningham, among others -leveraged her star power to criticize the racist depictions of Chinese and Asian characters in Hollywood, as well as raise money and popular support for China & Chinese refugees in the 1930s and 40s. -face card REFUSED to decline"

Josephine Baker:

Black, American-born, French dancer and singer. Phenomenal sensation, took music-halls by storm. Famous in the silent film era.

Let's talk La Revue Negre, Shuffle Along. The iconique banana outfit? But also getting a Croix de Guerre and full military honors at burial in Paris due to working with the Resistance.

She exuded sex, was a beautiful dancer, vivacious, and her silliness and humor added to her attractiveness. She looked just as good in drag too.

So I know she was more famous for other stuff than movies and her movies weren’t Hollywood but my first exposure to her was in her films so I’ve always thought of her as a film actress first and foremost. Also she was the first black woman to star in a major motion picture so I think that warrants an entry

Iconic! Just look up anything about her life. She was a fascinating woman.

588 notes

·

View notes

Text

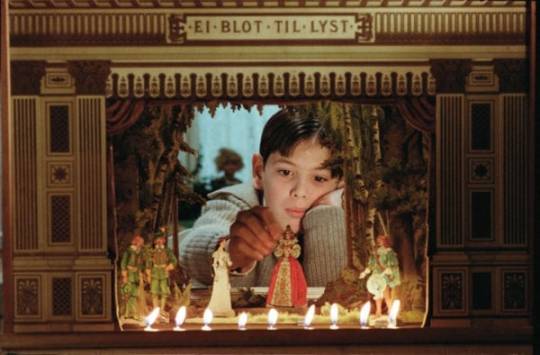

Film #728: ‘Fanny and Alexander’, dir. Ingmar Bergman, 1982.

It's not often I have to start one of these analyses by looking at the question 'What is cinema?' but Ingmar Bergman's filmography is so dense and wide-ranging that it was bound to happen sooner or later. His 1982 magnum opus Fanny and Alexander was originally imagined as a television miniseries and produced in a five-hour version, which was cut down to 188 minutes for a cinematic release. The longer miniseries was released subsequently. According to the book, the version under discussion is the 188-minute cinematic cut, although reading up about the film there are some details from the five-hour version that I think are particularly illuminating. It's arguable that referring to these details (from an extended cut I haven't seen, no less!) is like citing page numbers from Tolkien when talking about Peter Jackson's Hobbit films, but this is my blog, so I'm not going to wade into the reeds on this one.

Anyway, the reason the provenance of Fanny and Alexander feels a little more relevant is because Scandinavia has a rich history of crossover between film and television, with some of its most prominent directors working in television drama production as well as releasing feature films. With the rise of streaming services and prestige television this distinction is a little less important, but to the best of my knowledge Martin Scorsese has never directed an episode of Masterpiece Theater, which is the best analogy I could come up with. Bergman is a director who has clearly given deep thought to the differences between structuring, themes and acting for television and feature film, and the end result is that the three-hour cinematic release feels like three one-hour episodes chained together. The same characters, and an ongoing narrative, but strikingly different themes and tones across each of them.

The first hour introduces our protagonist, Alexander (Bertil Guve), a boy with a feverish imagination. In the first few moments of the film we already see through his eyes a statue moving, and we can get an instant sense of his creativity, but also some of the emotional myopia specific to children - Alexander is withdrawn and distant when he pleases and recklessly dishonest when he pleases, and is constantly blindsided by how others react to his behaviour. This first 'episode' takes place on a busy Christmas Eve as the entire Ekdahl clan gathers at the home of the grandmother Helena (Gunn Wållgren, in her final performance). Helena acts as the emotional centre of the family for the majority of the film, and right from the beginning we often see the other family members considering their own actions in relation to what Helena would think. Some of these characters are drawn in great detail to prepare us for their appearances later: the romance between the married Gustav Adolf (Jarl Kulle) and the family's maid, Maj (Pernilla August) is an ongoing plot, for example. Other characters are carefully drawn, such as Carl, the philosopher, who hates himself for hating his wife, and who only seems happy entertaining the children with his performative farting - but Carl only appears in this section of the film. Bergman is drawing a rich cast of characters that give the world a feeling of population; an intricate web of relationships.

Alexander's father, Oscar (Allan Edwall) gives a rousing Christmas speech to the employees at the theatre he operates, focusing on the differences between the 'little world' of the playhouse and the 'bigger world' outside. He observes that the theatre sometimes succeeds at reflecting the real world, but that the theatre is also an opportunity to escape those real cares - a theme that will be repeated at the end of the film.

Our second episode shifts the focus a little smaller, to the relationship between Alexander and his immediate family. Oscar dies of a stroke while rehearsing the role of the Ghost in Hamlet, and his mother Emelie (Ewa Fröling) is immediately wooed by the local bishop, Edvard (Jan Malmsjö). Emelie immediately learns she has made a mistake when Edvard is strict and controlling towards her and the children, demanding they rid themselves of their possessions and limit their contact with her family. Seemingly out of a mix of retaliation and grief, Alexander's lies and fantasies become more outlandish, culminating in his telling Edvard's maid that he saw the ghosts of Edvard's former wife and children, who announced that Edvard was responsible for their deaths. The maid immediately tells Edvard who, while Emelie is away secretly visiting her family, punishes Alexander and confines him to the attic.

Emelie seeks help from her family, and salvation comes in the form of Isak Jacobi, a local pawnbroker and old flame of Helena. Isak smuggles the children out of the house while Emelie, who is now pregnant with Edvard's child, remains.

The focus is narrowed once more in the third episode, which almost exclusively revolves around Alexander's stay with Isak and his nephews. One is a master puppeteer and the other is a mysterious invalid who seems to have the ability to control the minds and actions of others (I say 'seems' because the film is quite deliberately vague on this point - a decision I'll come back to later). The two nephews either cajole or enable Alexander to bring about the death of the bishop, partially in conjunction with Emelie's decision to heavily sedate her husband so she can leave. The death of the bishop means that Alexander, Fanny and their mother can return to their extended family once more, and the film ends at a lunch celebrating a double christening: Maj's child with Gustav Adolf, and Emelie's child with the deceased Edvard. Gustav Adolf gives a speech which is quite similar to Oscar's in the first hour of the film, extolling the importance of actors in distracting us from life's problems.

The fact that the film opens and closes with similar speeches about the role of theatre in life is telling, because Fanny and Alexander feels like a drawing-room theatre trilogy. Many of the films on the list have drawn their similarities to theatre in an explicit way (think of The Golden Coach, which uses a theatre as a framing device, or Diva, which begins and ends with diegetic opera performances on a stage), but Bergman is working on a slightly more implicit and thematic level. His film is full of literal actors and literal performances, sure, but he also encourages us to think about life through the lens of these performances, rather than just the performances per se.

Here's an example: Oscar's death happens during a rehearsal of Hamlet, in which Oscar is playing the role of the ghost of Hamlet's father. Alexander is in the audience for this rehearsal, and witnesses his father's collapse. The rest of this act plays with the tropes of Hamlet. Alexander is haunted, but not by the ghost of his father (the person who sees Oscar's ghost in this act is Helena). Rather, Bergman uses the trope of 'a ghost attesting to a wrongful death' - Alexander claims to see ghosts who accuse the bishop. A hasty marriage following the death of the protagonist's father is also central to this act, but the causality of it is out of kilter with the narrative being put right in the foreground. Either Bergman, or Alexander, or maybe both, is trying to make life make sense by recycling parts of Shakespeare's play, but none of the pieces quite fit together. At the end of the film, the bishop has been killed, but unlike Hamlet, Alexander stays alive, and the implication instead is that he will forever be haunted by the bishop.

But why should he be? I think it's pretty illuminating from a thematic point of view that at no stage do we really get confirmation of whether the ghosts that Alexander sees are real (at least in this version - in the five-hour version we apparently see the ghosts too, but I can't determine whether we see them in real-time or if they're only show through the frame of a story Alexander tells). The behaviour of the bishop in response to Alexander's accusations is interesting, because Jan Malmsjö plays his role with the menace that makes you believe he could be capable of such a thing. One of three possibilities is true: that the bishop killed his wife and children and the ghosts are real, that the bishop didn't and the ghosts are fictions dreamed up by Alexander, or that Alexander imagines the ghosts and yet has lucked into revealing the truth about the bishop. Bergman doesn't come down strongly on this question, and even the reveal at the end that the bishop's ghost now haunts Alexander doesn't help matters one way or the other. All of these explanations are plausible - either the result of a legitimate haunting or the fevered imagination of a guilt-ridden child.

The same questions arise again when the bishop dies. At least according to what the film tells us is true, the following happens: the bishop's bedridden aunt draws a kerosene lamp closer to her, it topples and sets her alight, and then she fatally injures the heavily-sedated bishop in her attempts to get help. It appears, according to the narrative, that the aunt pulls the lamp closer under the influence of either the puppeteer, who is seen drawing a light closer directly juxtaposed with the aunt doing the same, or under the influence of the other nephew, guiding Alexander to unleash his most destructive psychic impulses. Again, though, both these supernatural explanations are in conflict with the natural explanation.

Whichever of the explanations for these events Bergman wants us to believe is true, it is apparent that these imaginative explanations aren't a lot of help to Alexander: most of the time, in fact, they make things worse. It ultimately doesn't matter too much whether Alexander sees real ghosts or simply imagines them, whether he says so out of childishness or malice: his punishment for claiming to see them is real either way. If Alexander believes himself to be enacting a skewed version of Hamlet's story, the lessons of the play don't benefit him at all. At the end of the film, with the bishop dead (and his death shown in excruciating detail in a flashback), the stories that Bergman uses to try and make sense of the world are shown to be of little help. That brings us back to the speeches that Oscar and Gustav Adolf give, with Gustav Adolf in particular imploring the family, "Don't be sad, dear splendid artists - actors and actresses, we need you all the same. You are there to provide us with supernatural shudders... or even better, our mundane amusements."

What this speech doesn't tell us art and theatre can do is solve problems. It tells us stories of power and the supernatural, but Bergman's film is refreshingly pragmatic when it tells us that art is not powerful or supernatural in itself. It is fiction, and even when it is telling us that amazing things are possible, that doesn't make the amazing things the story depicts any more real than if it said they were impossible.

Fanny and Alexander does seem to have one moment that displays an outright impossible thing. When Isak smuggles the children out of Edvard's house, he hides them in a chest he has offered to purchase from the bishop. He sneaks them into the chest and covers them with a small cloth - clearly too small to adequately hide them. The bishop catches on to Isak's plot, and throws the chest open, but does not see the children inside. He runs upstairs to try and locate them, while Isak falls to his knees and screams in frantic, rageful prayer. Upstairs, Edvard finds the children lying on the floor, still and rigid, but Emilie screams at Edvard not to touch them, and Edvard obeys. The children, apparently still in the chest, are meanwhile snuck out of the house.

What on earth are we to make of this? The film doesn't otherwise give us any reason to believe in the power of God, either from a Christian or Judaic perspective (and it's very difficult to tell if Bergman is drawing on particular strands of Jewish mysticism or just general Semitic stereotypes). I've been influenced here by another blog, Seeing Things Secondhand, whose author is, I believe, an English teacher in the States. Writing about Bergman's work as a whole, he says "God has been uncaring (The Seventh Seal), impotent (The Virgin Spring), terrifying (Through a Glass Darkly), missing (The Silence). Here he is a puppet of man." Isak, and the nephews, Aron and Ismael, evoke God's power to their own ends, and it is always imbued with a hint of menace. After all, if you have access to this type of power, what wouldn't you use it for?

The power Isak and his nephews wield might be real, it might be explained away by a complicated chain of causes, but either way it's not something that the Ekdahl clan has access to. What they have is far more toothless but it is also not tinged with threat at every turn. Isak in particular, straddling the world of the Ekdahls and the world of mysticism, seems like a genial old man who should not be pushed to extremes. In comparison, the rest of the family, as turbulent as their lives are, seem ever-gentle. And that's okay. Their job in the theatre isn't to solve problems, but just to tell us stories.

Fanny and Alexander raises constant interesting questions, then, but the story that it tells across its epic runtime floats, barely tethered, above them. Rick Moody, writing for Criterion and wondering about how autobiographical the film is, suggests that the solution to a film like this is just "to realize that it is the interrogatives of which life is composed. Maybe Fanny and Alexander is simply an autobiographical yarn as Alexander would tell it, so that Bergman and Alexander now appear to us to be one and the same narrator of the tale. Maybe Alexander is Bergman refracted, in this instance in the convex mirror of art, where strange happenstances are routine and tidy answers are hard to come by. Or maybe Bergman is somehow Alexander’s own dream, from which the boy has yet to wake."

That wording resonates with the final scene of the film, in which Emelie presents Helena with the script for the next play the theatre intends to present, August Strindberg's A Dream Play. Sitting down with Alexander resting his head on her knee, Helena begins to read: "Anything can happen. Anything is possible and likely. Time and space do not exist..." It's an oddly comforting conclusion, freeing the characters and the audience from the expectation that anything must be explained. All that needs to happen is for us to watch and to narrate, and life will go on in that gentle way.

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

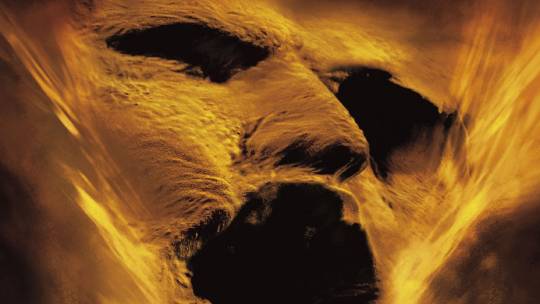

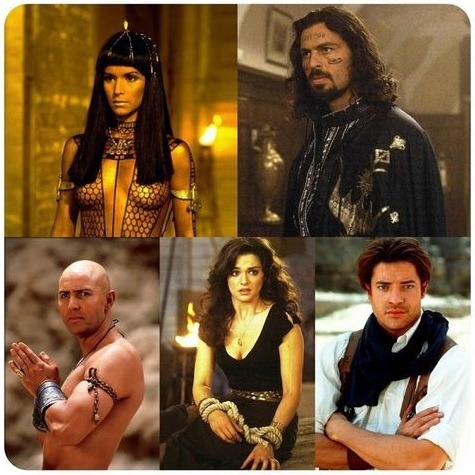

In Focus: The Mummy

Dominic Corry responds on behalf of Letterboxd to an impassioned plea to bump up the average rating of the 1999 version of The Mummy—and asks: where is the next great action adventure coming from?

We recently received the following email regarding the Stephen Sommers blockbuster The Mummy:

To whom it may concern,

I am writing to you on behalf of the nation, if not the entire globe, who frankly deserve better than this after months of suffering with the Covid pandemic.

I was recently made aware that the rating of The Mummy on your platform only stands at 3.3 stars out of five. … This, as I’m sure you’re aware, is simply unacceptable. The Mummy is, as a statement of fact, the greatest film ever made. It is simply fallacious that anyone should claim otherwise, or that the rating should fail to reflect this. This oversight cannot be allowed to stand.

I have my suspicions that this rating has been falsely allocated due to people with personal axes to grind against The Mummy, most likely other directors who are simply jealous that their own artistic oeuvres will never attain the zenith of perfection, nor indeed come close to approaching the quality or the cultural influence of The Mummy. There is, quite frankly, no other explanation. The Mummy is, objectively speaking, a five-star film (… I would argue that it in fact transcends the rating sytem used by us mere mortals). It would only be proper, as a matter of urgency, to remove all fake ratings (i.e. any ratings [below] five stars) and allow The Mummy’s rating to stand, as it should, at five stars, or perhaps to replace the rating altogether with a simple banner which reads “the greatest film of all time, objectively speaking”. I look forward to this grievous error being remedied.

Best,

Anwen

Which of course: no, we would never do that. But the vigor Anwen expresses in her letter impressed us (we checked: she’s real, though is mostly a Letterboxd lurker due to a busy day-job in television production, “so finding time to watch anything that isn’t The Mummy is, frankly, impossible… not that there’s ever any need to watch anything else, of course.”).

So Letterboxd put me, Stephen Sommers fan, on the job of paying homage to the last great old-school action-adventure blockbuster, a film that straddles the end of one cinematic era and the beginning of the next one. And also to ask: where’s the next great action adventure coming from?

Brendan Fraser, Rachel Weisz and John Hannah in ‘The Mummy’ (1999).

When you delve into the Letterboxd reviews of The Mummy, it quickly becomes clear how widely beloved the film is, 3.3 average notwithstanding. Of more concern to the less youthful among us is how quaintly it is perceived, as if it harkens back to the dawn of cinema or something. “God, I miss good old-fashioned adventure movies,” bemoans Holly-Beth. “I have so many fond memories of watching this on TV with my family countless times growing up,” recalls Jess. “A childhood classic,” notes Simon.

As alarming as it is to see such wistful nostalgia for what was a cutting-edge, special-effects-laden contemporary popcorn hit, it has been twenty-one years since the film was released, so anyone currently in their early 30s would’ve encountered the film at just the right age for it to imprint deeply in their hearts. This has helped make it a Raiders of the Lost Ark for a specific Letterboxd demographic.

Sommers took plenty of inspiration from the Indiana Jones series for his take on The Mummy (the original 1932 film, also with a 3.3 average, is famously sedate), but for ten-year-olds in 1999, it may have been their only exposure to such pulpy derring-do. And when you consider that popcorn cinema would soon be taken over by interconnected on-screen universes populated by spandex-clad superheroes, the idea that The Mummy is an old-fashioned movie is easier to comprehend.

However, for all its throwbackiness, beholding The Mummy from the perspective of 2020 reveals it to have more to say about the future of cinema than the past. 1999 was a big year for movies, often considered one of the all-time best, but the legacy of The Mummy ties it most directly to two of that year’s other biggest hits: Star Wars: Episode One—The Phantom Menace and The Matrix. These three blockbusters represented a turning point for the biggest technological advancement to hit the cinematic art-form since the introduction of sound: computer-generated imagery, aka CGI. The technique had been widely used from 1989’s The Abyss onwards, and took significant leaps forward with movies such as Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991), Jurassic Park (1993) and Starship Troopers (1997), but the three 1999 films mentioned above signified a move into the era when blockbusters began to be defined by their CGI.

A year before The Mummy, Sommers had creatively utilised CGI in his criminally underrated sci-fi action thriller Deep Rising (another film that deserves a higher average Letterboxd rating, just sayin’), and he took this approach to the next level with The Mummy. While some of the CGI in The Mummy doesn’t hold up as well as the technopunk visuals presented in The Matrix, The Mummy showed how effective the technique could be in an historical setting—the expansiveness of ancient Egypt depicted in the movie is magnificent, and the iconic rendering of Imhotep’s face in the sand storm proved to be an enduringly creepy image. Not to mention those scuttling scarab beetles.

George Lucas wanted to test the boundaries of the technique with his insanely anticipated new Star Wars film after dipping his toe in the digital water with the special editions of the original trilogy. Beyond set expansions and environments, a bunch of big creatures and cool spaceships, his biggest gambit was Jar Jar Binks, a major character rendered entirely through CGI. And we all know how that turned out.

A CGI-enhanced Arnold Vosloo as Imhotep.

Sommers arguably presented a much more effective CGI character in the slowly regenerating resurrected Imhotep. Jar Jar’s design was “bigger” than the actor playing him on set, Ahmed Best. Which is to say, Jar Jar took up more space on screen than Best. But with the zombie-ish Imhotep, Sommers (ably assisted by Industrial Light & Magic, who also worked on the Star Wars films) used CGI to create negative space, an effect impossible to achieve with practical make-up—large parts of the character were missing. It was an indelible visual concept that has been recreated many times since, but Sommers pioneered its usage here, and it contributed greatly to the popcorn horror threat posed by the character.

Sommers, generally an unfairly overlooked master of fun popcorn spectacle (G.I. Joe: The Rise of Cobra is good, guys), deserves more credit for how he creatively utilized CGI to elevate the storytelling in The Mummy. But CGI isn’t the main reason the film works—it’s a spry, light-on-its-feet adventure that presents an iconic horror property in an entertaining and adventurous new light. And it happens to feature a ridiculously attractive cast all captured just as their pulchritudinous powers were peaking.

Meme-worthy: “My sexual orientation is the cast of ‘The Mummy’ (1999).”

A rising star at the time, Brendan Fraser was mostly known for comedic performances, and although he’d proven himself very capable with his shirt off in George of the Jungle (1997), he wasn’t necessarily at the top of anyone’s list for action-hero roles. But he is superlatively charming as dashing American adventurer Rick O’Connell. His fizzy chemistry with Weisz, playing the brilliant-but-clumsy Egyptologist Evie Carnahan, makes the film a legitimate romantic caper. The role proved to be a breakout for Weisz, then perhaps best known for playing opposite Keanu Reeves in the trouble-plagued action flop Chain Reaction, or for her supporting role in the Liv Tyler vehicle Stealing Beauty.

“90s Brendan Fraser is what Chris Pratt wishes he was,” argues Holly-Beth. “Please come back to us, Brendaddy. We need you.” begs Joshhh. “I’d like to thank Rachel Weisz for playing an integral role in my sexual awakening,” offers Sree.

Then there’s Oded Fehr as Ardeth Bey, a member of the Medjai, a sect dedicated to preventing Imhotep’s tomb from being discovered, and Patricia Velásquez as Anck-su-namun, Imhotep’s cursed lover. Both stupidly good-looking. Heck, Imhotep himself (South African Arnold Vosloo, coming across as Billy Zane’s more rugged brother), is one of the hottest horror villains in the history of cinema.

“Remember when studio movies were sexy?” laments Colin McLaughlin. We do Colin, we do.

Sommers directed a somewhat bloated sequel, The Mummy Returns, in 2001, which featured the cinematic debut of one Dwayne Johnson. His character got a spin-off movie the following year (The Scorpion King), which generated a bunch of DTV sequels of its own, and is now the subject of a Johnson-produced reboot. Brendan Fraser came back for a third film in 2008, the Rob Cohen-directed The Mummy: Tomb of the Dragon Emperor. Weisz declined to participate, and was replaced by Maria Bello.

Despite all the follow-ups, and the enduring love for the first Sommers film, there has been a sadly significant dearth of movies along these lines in the two decades since it was released. The less said about 2017 reboot The Mummy (which was supposed to kick-off a new Universal Monster shared cinematic universe, and took a contemporary, action-heavy approach to the property), the better.

The Rock in ‘The Mummy Returns’ (2001).

For a long time, adventure films were Hollywood’s bread and butter, but they’re surprisingly thin on the ground these days. So it makes a certain amount of sense that nostalgia for the 1999 The Mummy continues to grow. You could argue that many of the superhero films that dominate multiplexes count as adventure movies, but nobody really sees them that way—they are their own genre.

There are, however, a couple of films on the horizon that could help bring back old-school cinematic adventure. One is the long-planned—and finally actually shot—adaptation of the Uncharted video-game franchise, starring Tom Holland. The games borrow a lot from the Indiana Jones films, and it’ll be interesting to see how much that manifests in the adaptation.

Then there’s Letterboxd favorite David Lowery’s forever-upcoming medieval adventure drama The Green Knight, starring Dev Patel and Alicia Vikander (who herself recently rebooted another video-game icon, Lara Croft). Plus they are still threatening to make another Indiana Jones movie, even if it no longer looks like Steven Spielberg will direct it.

While these are all exciting projects—and notwithstanding the current crisis in the multiplexes—it can’t help but feel like we may never again get a movie quite like The Mummy, with its unlikely combination of eye-popping CGI, old-fashioned adventure tropes and a once-in-a-lifetime ensemble of overflowing hotness. Long may love for it reign on Letterboxd—let’s see if we can’t get that average rating up, the old fashioned way. For Anwen.

Related content

How I Letterboxd with The Mummy fan Eve (“The first film I went out and bought memorabilia for… it was a Mummy action figure that included canopic jars”)

The Mummy (Universal) Collection

Every film featuring the Mummy (not mummies in general)

Follow Dom on Letterboxd

#the mummy#brendan fraser#stephen sommers#action adventure#fantasy adventure#action adventure film#the green knight#david lowery#dominic corry#letterboxd

530 notes

·

View notes

Text

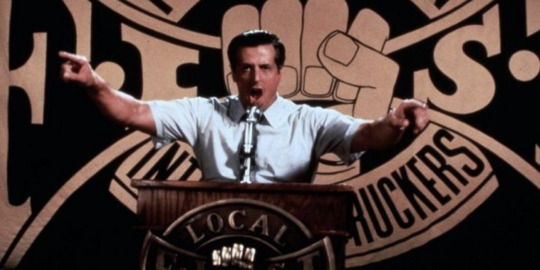

The Trial of the Chicago 7 (Or, Sorkin’s attempt to show you how nothing has changed in 52 years)

If you know anything about Aaron Sorkin, the much-acclaimed writer/creator of television shows like The West Wing, The Newsroom, you know that subtlety is not his strong suit. So, I was rather hesitant going into his newest film, The Trial of the Chicago 7, the infamous trial of eight gentlemen accused of conspiracy to incite violence/rioting in Chicago during the notorious 1968 DNC riots. Without diving too deep into the history, August 1968 was not Chicago’s finest hour. When the protesters chanted as a warning to the police, “The Whole World Is Watching!”, they weren’t wrong. Years ahead of the 24-hour news cycle, people all across America (and across the world) were glued to the TV watching the Chicago police beat the ever-living snot out of young folks protesting the Democratic Party’s decision to support the ever-controversial war in Vietnam. The film’s subject matter is sure to draw parallels to and resonate strongly with both the protests and civil unrest that took place this past summer following the death of George Floyd and countless other Black folk at the hands of police. So despite it’s appropriate timeliness, I was hesitant to watch this movie because I really wasn’t interested in watching Aaron Sorkin (who not only wrote but directed this film) try to mansplain to me that the trial of the Chicago 7 was all about injustice! Without knowing anything else about the trial beforehand (and I really didn’t), I already knew it’s a famous case of injustice. I wanted to watch the movie to learn about the people, the humans involved, and the nuance of the situation.

The film gets off to a rough start in the nuance department. After an effective montage introducing us to six of the eight members of the Chicago 7 (we’ll get to why there’s that numerical discrepancy), we meet the character who will be the lead prosecutor of the case: a straight-laced, clean-cut lawyer played by Joseph Gordon-Levitt. In an attempt to plant the seed early on that the eponymous trial is a sham, the first real scene of the film sees Gordon-Levitt meeting with Nixon’s newly appointment Attorney General John Mitchell who is pissed off that the prior AG didn’t resign from the office until an hour before Mitchell was confirmed. As retaliation, and in line with history’s understanding of Nixon’s pathologic paranoia, Mitchell decides to re-open the case exploring whether there was any conspiracy to incite riots in Chicago 1968. As JGL explains, this was something which Johnson’s AG as well as prior FBI investigations already decided did was not a viable case. The conversation that ensues is a little too on-the-nose. JGL shares his concerns that he doesn’t believe that the Chicago 7 are actually guilty, but Mitchell tells JGL, “then imagine how impressed I’ll be when you get a conviction.”

Of course, this conversation is largely a Sorkin invention, as is the weird decision to try to humanize the prosecutor played by Gordon-Levitt. I say "weird" because the film doesn’t do anything with it. We don’t get a real sense beyond that initial scene that JGL feels guilt or remorse for being a cog in the Nixon machine. The beginning of the film sets him up to be a similar character to David Schwimmer’s fascinating turn as Robert Kardashian in The People vs. O.J. Simpson. But in the end, it’s clear that Sorkin uses him just as a way in the beginning of the film to provide the thesis statement for the film, as if he were writing this script as a college term paper. This bothers me so much because it makes a late-film surprise appearance by Michael Keaton as Johnson’s AG lose a good deal of its impact. It would have been so much better if we as the audience came to the same revelation about the political origin of the trial at the same time that the defense lawyers did.

Sorkin’s lack of subtlety reared its ugly head in a few key moments that caused me to audibly groan while watching this film. Towards the end of the film, one of the more dramatic defendants, the merry prankster hippie Abbie Hoffman (played very well by Sacha Baron Cohen), is on the stand and is asked a particularly difficult question by the prosecution. He pauses. The prosecution asks what’s taking so long. Hoffman responds in a serious tone that runs opposite of his usual character, “Sorry, I’ve never been on trial for my thoughts before.” The film then slowly fades to black. I half-expected to hear the famous Law & Order “chun-chunn” sound next. That’s how cheesy and self-righteous the scene was.

The film’s ending too, where the defendants read off a list of all the fallen soldiers from Vietnam prior to their sentencing, felt a little too Hollywood to be believable… and indeed it didn’t happen that way. Elsewhere in the film, one of the more “prim and proper” defendants, the young head of the Students for a Democratic Society Thomas Hayden played by Eddie Redmayne, reflexively stands in honor of the judge’s exit as is court custom, forgetting that he and the rest of the defendants agreed not to stand. That’s not the bad part. The bad part comes later when Redmayne’s character travels to someone’s home and the Black maid who answers the door says to him, “I heard you were the only one to stand for the judge,” and then the camera just sorta lingers on her disappointment. We get it! The judge is a bad dude! Let’s move on!

Seriously, let’s move on. For all my griping, this is a very good movie. Those instances where Sorkin’s moral heavy-handedness is plain to see are so glaring because for the most part, the movie does a fantastic job of addressing the film’s (sadly still) politically controversial themes (police brutality, the culpability of protesters in starting riots, systemic racism, etc.) with a good deal of nuance. This mostly happens when Sorkin just sticks to the facts of the case, like when dealing with the whole saga of Bobby Seale, the eighth and only Black man of the Chicago 7. The day before the trial begins, Seale's lawyer required emergent surgery. Seale’s motion to have the trial postponed till he receive proper counsel is denied, as is his request to represent himself. Therefore, on trial without counsel, he frequently interrupts the court arguing about the unconstitutional nature of his trial, until the judge, played to chilling perfection by Frank Langella, becomes fed up with the interruptions and orders that Seale be bound, gagged, and chained to his chair. It’s a crazy powerful and uncomfortable scene, among the most haunting images I’ve seen in cinema. Finally, Seale’s case is determined to be a mistrial, changing the number of defendants from eight to seven. Hence, the Chicago 7.

But, the most inspired sequence of the film comes late in the movie when the defense gets wind of the prosecution’s plan to play a recording from the night of the riots where the prim and proper Tom Hayden can be (arguably) heard urging hundreds of listeners to “let blood flow all over the city.” Tom still believes that he would do well on the witness stand, but his defense lawyer (Mark Rylance as William Kuntsler) insists on showing him why this would be a bad idea. The ensuing scene sees Rylance role play the part of the prosecution cross-examining Hayden while the film intercuts scenes of a flashback of the actual events. the “truth” of that night, significantly muddies the water for this case. It by no means proves that the Chicago 7 are guilty of a conspiracy, but it certainly highlights the more human aspect of their situation. How is one expected to keep their calm when their best friend is beaten? And to what degree are people to be held responsible for decisions made in the heat of the moment?

The movie also has also interesting commentary on who should be the “face” or progressive politics, even today: the well-to-do and respectable Hayden or the in-your-face hippie comedian Hoffman? It’s an interesting question that never seems fully explored or resolved. Sorkin seems to land in the camp that Hayden’s respectability merely maintains status quo whereas Hoffman’s flagrant anti-establishment views is required for real change. But I don’t know how much of that is me just loving Cohen’s performance as Hoffman and finding Redmayne’s Hayden to be (appropriately) insufferably pretentious. Sorkin certainly gives Cohen the better lines.

Overall, this is a movie held up by its two primary strengths: its cast and its film structure. Aside from general inconsistencies of the script’s tone and the notable weakness I mentioned previously about overplaying the political motivation for the trial in the film's first 5 minutes, the film is nearly perfectly structured. We are sort of dropped in medias res into the trial and only get the facts of those few days shown to us in carefully placed flashbacks that help to flesh out the drama of the trial. It helps maintain pacing in what could have been a drag of a legal drama.

But really, it’s the cast and their performances that sell this movie. Sacha Baron Cohen is the star in my mind, so perfectly cast as Abbie Hoffman, but Frank Langella as the septuagenarian, prejudiced judge of the case is equally powerful. Yahya Abdul-Manteen II as the Black Panther Bobby Seale lends an air of desperate seriousness to the film, Eddie Redmayne shines as that white liberal dude who takes himself way too seriously, and Mark Rylance is wonderful as the courageous lead defense attorney, particularly in scenes dealing with Bobby Seale. While the whole trial weighs on him heavily as the film progresses, his genuine concern for Seale is palpable.

I spent much of this review telling you the things that were odd about this film, and I stand by that. But as I said, those things stand out because this is such a slick production that the cracks become that much more obvious. It largely avoids Sorkin’s penchant for blunt lack of nuance and offers a story that helps to greatly contextualize the very world we live in. It’s interesting that a story that sees ten men (including their lawyers) fail to win a fight against The Man still feels like an inspiring underdog tale. It resonated well with this viewer, especially as the ending makes clear that justice is eventually served. Yet, I recognize this may be a dangerous tale to tell these days, and why I think the movie is so successful is that it gives plenty of sobering evidence to suggest that justice (both then and now) is by no means guaranteed.

***/ (Three and a half out of four stars)

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

Smokey brand Retrospective: Red Pill Me

Cinemacon has passed and there has been a lot of awesome sh*t revealed. On the top of that list, obviously, Spider-Man: Far From Home has me geeked to high heaven but there were a ton of other noteworthy reveals. There was some Batman reveals, a few Mission Impossible 7 and Top Gun 2 trailers, plus audiences ever got a surprise screening of Ghostbusters: Afterlife. Now, that would be great on it's own but cats even got a little sizzle real for Matrix Resurrections: The long gestating fourth Matrix film. Apparently, this thing is releasing in December. I am lukewarm at best. I have fond memories of the Matrix trilogy as a whole but, since it’s final release some twenty years ago, the Wachowskis have been revealed to be one trick ponies. They kind of suck at film making. I mean, i liked Speed Racer but i just generally enjoy Speed Racer. It helped tremendously that Christina Ricci was Trixie, too, but everything after that was kind of balls. I also really like V for Vendetta but that’s not real their movie, they just adapted it. I guess you can say that about Speed Racer, too. Anyway, in light of there near Shyamalan-esque track record with their films, i wanted to revisit the first three Matrix films and see if they hold up, to try and muster some sense of excitement for what comes next.

The Matrix

Of the trilogy, this is easily the best film. Everything about it is exceptional. The Matrix was a whole ass shift in the cultural zeitgeist. It was a lot of people’s first experience with accessible cyberpunk and I'll always love it for that. I’ll also love it for normalizing Hong Kong style action sequences and giving us the most breathtaking application of Bullet Time I've seen to date. The Matrix s why the theater exists. If you’ve never seen this thing on the big screen, you missed out on something very special. I had just just turned thirteen when it released and checked it out at the dollar theater. I had only ever seen anything like this, in anime. Seeing all of my favorite Eighties OVAs filtered through the big budget Hollywood lens was incredible. I even like the rather pedestrian narrative. I think the story worked for what the movie was trying to do. It’s a shame the Wachowskis have tried to rewrite history about the narrative as of late. I understand the underlying themes of identity and sexuality but come on? That’s some college film theory bullsh*t that got tacked on after the fact. Now, if the original script is to be believed, then, yes, all of that, but what we got is not so profound. This is a basic Chosen One narrative with Dope ass effects that were ahead of it’s time.

A fr as the cast, what can i say? These motherf*ckers were perfect. Keanu Reeves as Neo was inspired. It’s wild to say that because dude is a plank but it works. He’s the POV character, he’s who you see that world through. Making him a blank slate so to speak, helps with immersion and that is a world you definitely wan to be immersed within. This was my first experience with Carrie-Ann Moss and I've loved her ever since. Her Trinity fast became one of my favorite characters and I'm actually pretty excited to see where she is in the new film. Lawrence Fishburne as Morpheus was an interesting choice. I wasn’t mad and it worked perfectly but it was weird seeing him in such an active, action oriented, role. That said, for me, this movie is made by Hugo Weaving. He is absolutely monstrous as Agent Smith. He’s got this scene chewing energy that mirrors Christoph Waltz’s Hans Landa and we all know how much i love that Nazi f*ck so that’s really high praise. To this day, I've got his Humanity is a Virus speech memorized. It was just that f*cking good! The Matrix is an exquisite watch and it is absolutely mandatory viewing if you consider yourself a fan of cinema.

The Matrix Reloaded

Whoo, boy, talk about a drop in quality. Reloaded released four years later in 2003 and it screams Studio Mandate. I was a sprightly eighteen years old when this thing dropped and made it a point to see it opening day. I really enjoyed the first outing so i figured this one would be just as amazing. Indeed, i remember leaving the theater thinking to myself how decent of a sequel it turned out to be. It wasn’t better than the first but it didn’t sh*t the bed like most follow-ups do. Fast forward to present day and, after watching this thing again for the first time in probably fifteen years, it’s kind of f*cking bad. Like, as a cinematic experience, it’s pretty tight Everything is amped up. Tons more action, way more bombastic set pieces, stakes have been raised considerably; The Matrix Reloaded is everything you want in a summer blockbuster sequel. However, that’s it. Everything else is worse. The acting has become way too hammy and the new cast members fit into this narrative like a square peg in a round hole. Why is f*cking Niobe even in this thing? Who even is the Merovingian? Why is Mouse? The pacing is all over the place, too. Like, this thing stops dead in it’s tracks on several occasions but that’s not the worst of it.

The worst thing is the narrative. What the f*ck even is the story trying to be told in this movie? It doesn’t make any f*cking sense. The Matrix was, very obviously, a standalone film. That was a closed narrative. Neo’s story had been told. Everything after that is unnecessary. This movie is an exercise in the unnecessary. I appreciate all of how unchained and manic Smith is in this but, outside of that, what the f*ck was the point of this whole narrative? It’s filler. This movie is filler and it feels like it. The returning cast is serviceable and seeing Zion was interesting. I like how all the survivors are just sweaty black people. I literally hated everyone added to the cast though. Well, that’s not quite true. I rather enjoyed Collin Chou as Seraph. Dude was inconsequential but i love seeing Asian martial artists not name Li or Chan getting some shine. Also, Monica Bellucci is in this and i kind of just love her in general. Her Persephone is absolutely disposable but she looks damn fine in that plastic wrapped dress of hers. I literally can’t be bothered mentioning anyone else. They are that forgettable. This movie is that forgettable. And it’s arguably the best of the two sequels.

The Matrix Revolutions

Talk about going out with a thud. Man, i saw this with my best friend, rest in peace B, and we both hated it. He was an even bigger fan of The Matrix than i was so his disappointment was palpable. I’ll never forget his visceral reaction when that rainbow spread across the super happy Hollywood ending. Dude was hot and he had every right to be. The first Matrix set up this intriguing, immersive, world full of fanatic visuals, great piratical stunts, and a very through provoking premise. The second Matrix was your basic Hollywood sequel; More shine, less substance. But Revolutions? Man this is peak Wachowski fail. You saw hints of this messiah sh*t in the first, it’s literally a Chosen One narrative, but thy went all in on that sh*t in Reloaded. By the time Revolutions finished, this whole narrative was so far up it’s own ass, it didn’t know which way was up. It just f*cking ends. Everyone is dead and it’s over. The Wachowskis went heavy on the Jesus imagery, they were not subtle, and the f*cking conflict just ends. Robot don’t stop using people as batteries. Flesh and blood Humans still have to live in Zion. The only thing that’s changed is Neo’s dead and Agent Smith has been deleted. That’s it. The Matrix still exists, people are still trapped in it, and everything that happened in these films doesn’t f*cking matter. Literally right back at the start of the whole goddamn conflict. Revolutions is so f*cking disappointing, dude, by every measure of that metric.

Hugh Weaving is still pretty good as Smith and Keanu does his best imitation of white bread as Neo but, like, everything else is just so pedestrian. Plus, this thing is long. Like, unreasonably so. Why the f*ck is this movie two hours? The entire trilogy is kind of like that but it’s most egregious in this one. This story could be told in ninety minutes, just like Reloaded. Why the f*ck do i have an extra half hour of bullsh*t in this? Like, that whole “Neo Lost” arc was unnecessary, in both sequels. F*cking why? I don’t hate Revolutions. It’s not a “bad” film per say, it’s just disappointing. It’s the poster child for the law of diminishing returns. The Matrix Revolutions is the what happens when you let creatives with fresh egos, run amok with one hundred and fifty million f*cking dollars. So much spectacle but even less substance that Reloaded and that motherf*cker was a hollow mess. Still, The Matrix Revolutions is better than anything Michael Bay or Zack Snyder has ever made so i guess it’s got that going for it.

#The Matrix#The Matrix Reloaded#The Matrix Revolutions#The Matrix Trilogy#Smokey brand Retrospective#Keeanu Reeves#Carrie-Anne Moss#Hugo Weaving#Lawrence Fishburne

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

Towards the middle of Disney’s live-action remake of Mulan, the shape-shifting witch Xian Lang, played by Gong Li, finally encounters Liu Yifei’s Hua Mulan on the battlefield. Although Mulan is disguised as a man, Xian sees her true identity and tells her: “You will die pretending to be something that you are not.”

There is perhaps a lesson for Disney in these words.

Mulan is supposed to be just another Disney princess in a Chinese outfit – and the desire to be free and independent is seen in all iconic Disney characters, from Jasmine in Aladdin to Elsa in Frozen. But themes of freedom and independence are taboos for a film targeting the vast China market, so if a Chinese dress is to be given to a Disney princess, some tweaks are necessary.

Perhaps understanding this, Disney appears to have decided to infuse as much “Chineseness” into the film as possible to please China, the world’s second-largest film market, and its censors in order to get the film screened.

So what should be added? Mulan must be loyal to the country and be willing to sacrifice her life to protect the emperor; and must live to bring honour to both her family and her country. Such elements aimed at boosting China’s national pride should work like magic, right?

Disney might have thought it had a sure thing by selling as a Chinese story adapted from a Chinese legend with an ensemble Chinese cast. But Disney was – to paraphrase former Chinese president Jiang Zemin’s famous admonition to the Hong Kong press – “too simple, sometimes naive” to think that the big bucks would roll in just like that.

But Disney’s most spectacular failure was its inability to understand the burden of history that weighs on almost every Chinese person’s shoulders when it comes to a watching Chinese story told by the West.

Chinese film-goers are sensitive and not to be offended – they will watch the film with a magnifying glass, focusing on every single detail, from the costumes to action choreography to (more importantly) the historical accuracy and cultural representation. To them, Mulan is not just another Disney princess, but an icon that supposedly represents the best of Chinese values.

This is where Disney lost the Chinese audience it has so desperately tried to win over. An embarrassing score of 4.9 out of 10 recorded on movie review website Douban – the Chinese equivalent of Rotten Tomatoes – would be hard to swallow for the film’s award-winning New Zealand-born director, Niki Caro, and the four Western writers who penned the script.

“Solid proof that Americans cannot tell a Chinese story well,” one user wrote on Douban. Another one said: “Please Americans, do not touch our Chinese culture. You don’t understand a thing. All I can see is deep-rooted arrogance and prejudice.”

Critics quoted in the Global Times – an English-language newspaper under the Chinese Communist Party mouthpiece People’s Daily – went further, blasting historical inaccuracies and misunderstanding of Chinese culture throughout the film. The newspaper called it “a mixture of oriental elements and symbols in the eyes of Westerners” and said Western fairy tales were incompatible with traditional Chinese stories.

This is a disaster made worse by the fact that the Beijing mouthpiece once promised that Liu and Mulan had the full support of the 1.4 billion Chinese people during the heat of the #BoycottMulan movement.

In the four days since the film opened in China on Friday, Mulan has so far brought in just US$23.2 million at the Chinese box office. This puts it on the low end of Disney film debuts in China and below the US$30 million the Christopher Nolan spy thriller Tenet generated the previous weekend. The restrictive reopening of cinemas in China after the coronavirus outbreak likely affected the figures, but the film’s poor reception is unlikely to help Disney rake in the big bucks it dreamed of.

However, not all criticism of the film is built on wounded national ego. Many dedicated fans of the 1998 animated film simply did not like the live-action remake, criticising the change of plot and the removal of beloved characters such as the small dragon Mushu. Many are baffled by the introduction of Xian Lang, although she is arguably the film’s most interesting character as she challenges the world dominated by men.

Surely the film’s epic fighting scenes would find favour in the land of wuxia films? Unfortunately not – the Chinese audience has been spoiled by numerous home-grown, big-budget productions during the past decade. Mulan’s fighting scenes – particularly the wire work – are so bad that some internet users even apologised to Chinese director Zhang Yimou for previously criticising his action fantasy epic The Great Wall.

The new Mulan is a lacklustre feature saturated with bland characters who convey little emotion. Liu’s emotionless performance is unbearable, and the choppy editing and scriptwriting make the film painful to watch. But worst of all is the misunderstanding and misinterpretation of qi throughout the film. Please Hollywood, just stop.

Disney has bent over backwards in the hope of making a splash in China with its “Chinese story”, and the appalling outcome, one that has upset both the West and China, is probably Hollywood’s most arresting plot twist ever.

The studio that has brought so much joy to people across the world has forgotten what it does best. Like Mulan herself, Disney is pretending to be something that it’s not, as it succumbs to an insatiable hunger for Chinese yuan.

Will Hollywood learn any lesson from this fiasco? Probably not, as long as it continues to bow down and beg for cash from the middle kingdom.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mortal Kombat (2021) vs. Mortal Kombat (1995): Which is Better?

https://ift.tt/3vh6gqd

This article contains Mortal Kombat (2021) spoilers.

“Test your might.” These are the words of a minigame in the original Mortal Kombat arcade fighter from 1992. They were meant to signal an interlude between the simple pleasures of digitized sprites spilling buckets of blood. Yet they’ve also become synonymous with a franchise that’s arguably the most popular video game fighter of all-time. The phrase is also a pretty apt description for the various filmmakers who’ve attempted the challenge of taming this crazy dragon on screen.

More than any other video game series, Mortal Kombat has seen a plethora of live-action adaptations, from Hollywood movies to syndicated television. This weekend marks another milestone in that history, too, with Warner Bros. and New Line Cinema’s hotly anticipated Mortal Kombat reboot opening in theaters and premiering on HBO Max. It’s the third Mortal Kombat movie released under the New Line banner, but let’s just call it the second serious attempt at putting this universe on screen after the 1995 cult classic directed by Paul W.S. Anderson.

That ’95 movie holds the dubious honor of being generally considered the best video game movie adaptation of all-time, thanks to a tongue-in-cheek tone perfect for its mid-‘90s moment and maybe the greatest use of techno music in film. Genuinely, how many other pictures have the soundtrack scream the title of the movie over and over again, and it seems like a good idea?

The new movie took a different approach to the material, and certainly a bloodier one. While both adaptations share the same basic premise of chosen “Earthrealm” guardians protecting our dimension from an invading force via martial arts fights, the executions diverge radically. Here’s how.

The Story

The starkly different approach to storytelling in director Simon McQuoid’s 2021 Mortal Kombat is evident during the film’s opening scene. Beginning in 1600s Japan with a gnarly, brutal fight sequence between Sub-Zero (Joe Taslim) and Scorpion (Hiroyuki Sanada), this version of Mortal Kombat relies heavily on lore and world-building. If you know the video game backstory of Sub-Zero/Bi-Han, and how he was kidnapped as a child by the Lin Kuei cult so they could brainwash him into the magical ninja we now see slaughtering Scorpion’s family, the scene has a sense of fateful tragedy.

If you don’t, well Taslim and Sanada are such gifted martial artists that it still looks really cool. By contrast, Mortal Kombat of the ’95 vintage is pretty straightforward and to the point. This is basically an interdimensional version of the Bruce Lee classic, Enter the Dragon (1973), only with magical powers and the fate of the world at stake.

We’re introduced to three fighters in ‘95, Liu Kang (Robin Shou), Johnny Cage (Linden Ashby), and Sonya Blade (Bridgette Wilson-Sampras), who all get on a boat to the tournament for different reasons. And while Liu Kang was raised by his Shaolin monk upbringing to know what this tournament is, the other two act as our eyes and ears into this strange world of mysticism and Outworld menace. By the time they reach the island, they understand they need to compete with superpowered foes to save Earth in a structured tournament.

Conversely, Mortal Kombat (2021) is curiously both more secretive and open about its bizarre universe. For a much larger chunk of its running time, the new movie’s point-of-view character Cole Young (Lewis Tan) is completely mystified by the superpowered horrors happening around him while the viewer is keyed in early by scenes set in the evil dimension of Outworld. There we see the dastardly sorcerer Shang Tsung (Chin Han) scheme from a throne about killing Cole in order to prevent a prophecy vaguely connected with the movie’s prologue scene in the 1600s. So he sends Sub-Zero to kill Cole in his day-to-day life as an MMA fighter, slaughtering him before he understands he’s been chosen to participate in the sacred Mortal Kombat tournament, which is held in secret every generation.

In fact, there is no actual tournament in the new film. Rather the plot eventually becomes Shang Tsung’s chosen band of evil warriors attempting to cheat ahead of the conflict by attacking Earthrealm’s depleted champions before they even discover they have superpowers (or “arcanas”) and know what Mortal Kombat is. The film thus becomes a quest movie with Cole joining forces with other “chosen ones” (or chosen one-aspirants) to find the Temple of Raiden, a lightning god (played by Tadanobu Asano) who represents the interests of Earthrealm in the tournaments. From there the heroes must learn their powers and evade preemptive, cheating attacks from Outworld’s thuggish baddies.

Side by side, the approaches appear to be the differences between a traditional (if derivative) martial arts flick and a modern studio blockbuster that is trying to cram as much fan service and world-building lore into a two-hour movie as possible in the hopes of making fanboys happy. I hesitate to say the 2021 film is fully following the Marvel Studios template given its copious amounts of blood and (seeming) lack of interest in building a shared universe of interconnected franchises. However, the 2021 film was certainly released in a post-Marvel world where the focus in studio committee rooms is less on telling a single story and more on building a whole convoluted mythology filled with fan favorite characters who are begging to be explored endlessly by future movies. It’s less story-driven than it is content-driven.

As a result, it leaves the narrative lacking. Viewers know long before Cole or 2021’s Sonya Blade (Jessica McNamee) what’s going on, and all the anticipation for a tournament that never materializes feels anti-climactic. With its simple structure, the Anderson-directed movie in the ‘90s plays out much more satisfyingly with three heroes (plus poor dead meat like “Art Lean”) entering a tournament by choice or trickery and then trying to survive it while learning vanilla, if tangible, life lessons. Liu Kang needs to accept his destiny; Johnny Cage must look before he leaps; and Sonya has to accept she’ll be the film’s damsel in distress even though she kicks ass. It’s an Enter the Dragon knockoff but it still has more kick than fan service.

Round One goes to 1995.

The Tone

The tone and aesthetics are also jarringly different between the two movies. Released in 1995, the same year Pierce Brosnan became James Bond, and two years before Arnold Schwarzenegger chilled out as Mr. Freeze, Mortal Kombat (1995) is an unmistakably campy movie and it leans into that fact.

Working with a low budget for a Hollywood spectacle even before New Line Cinema cut his funds by another $2 million right before cameras rolled, Anderson directed a B-movie that accepted its limitations and had fun with it. Apparently stars Ashby and Christopher Lambert, who played Lord Raiden in the ’95 movie, improvised dialogue throughout the shoot and rewrote entire scenes. As a consequence, Lambert’s lightning god was more of a jovial trickster in temperament, reminiscent of Loki instead of Odin. Johnny Cage, meanwhile, was essentially the film’s Han Solo: a cocksure wiseacre next to the stoic hero (Liu Kang) and a no-nonsense woman who doesn’t like to be called princess (Sonya).

As again signaled by the almost funereal opening sequence of Mortal Kombat (2021), where Sub-Zero murders Scorpion’s young family, the 2021 film is going for a differing sensibility. There is actually quite a bit of humor still present, with the real reason the Johnny Cage character got cut becoming apparent the moment we meet Kano (Josh Lawson), a loudmouth smartass who takes on the comic relief role but with an added slice of thuggery. Hence his dialogue has a lot more F-bombs than it does cracks about $500 sunglasses.

Other than moments where Kano is allowed to steal scenes, however, Mortal Kombat (2021) plays it pretty straight. Asano’s Raiden is imperious and his fighters stoic. However, it’s also worth noting Raiden is played by a Japanese actor, as opposed to a white American-born Frenchman who was raised in Switzerland (Lambert has quite the international background). Indeed, one of the more admirable qualities of the 2021 film is the focus on a diverse cast that includes more roles for Asian actors and people of color, whereas the 1995 film whitewashed Raiden and left out the Black American character Jax for little more than a cameo.

The 2021 film also upped the gore quotient considerably. While the martial arts of the 1995 film were decidedly PG-13, the tone of the movie was only a few steps removed from Power Rangers in some respects, including its introduction of a horrible CGI creation known as Reptile. The Reptile in the 2021 film appears more convincingly, like the latest monstrosity out of a Jurassic World lab, and the violence he commits is visually gruesome (more on that later).

Honestly, preferences over the aesthetic differences between the two films comes down to a matter of taste. I prefer the tongue-in-cheek eye rolls of the 1995 film given how nonsensical this universe is, and how at the end of the day its target audience remains children. Yet I imagine many adult fans of the video games will prefer the blood-soaked earnestness found in 2021.

Round Two is a draw.

Chosen Players

Anyone who’s picked up a fighting game will tell you it’s all about finding a character or two you like and then training up with them. In 1995, Anderson had the advantage of primarily adapting the original 1992 arcade game with its limited collection of playable characters. Ergo, his film’s lineup easily focused on the three aforementioned heroes of Liu Kang, Johnny Cage, and Sonya Blade, plus the ambiguous Princess Kitana (Talisa Soto), and Lord Raiden. Meanwhile he divided his villain screen time between the sorcerer Shang Tsung (Cary-Hiroyuki Tagawa) and Shang Tsung’s minions, who were essentially glorified Bond henchmen with individual gimmicks.

Fan favorites Sub-Zero and Scorpion are present in the ’95 movie—with much more colorful, game-accurate costumes—yet they’re relatively low-hanging fruit in the tournament’s brackets. Their rivalry is given lip-service but they are dispatched by heroes Liu Kang and Johnny Cage relatively easily. Meanwhile Trevor Goddard’s Kano is more a hapless comic relief baddie who Wilson-Sampras’ Sonya kills with a great laugh line. “Give me a break,” Kano pleads with his head pinned between her thighs. “Okay,” she shoots back before snapping his neck.

Still, the movie largely belongs to Tagawa who makes a meal out of the scenery as the big bad. The guttural pleasure he has in so naturally turning all the over-the-top commands in the video game into his dialogue—“Finish Him!;” “Fatality;” “Test Your Might”—is infectious.

The 2021 film relies on a much larger cast of characters and, unlike the 1995 movie, attempts to give them each a moment to shine in the way Kitana and the original Kano could only dream. This surprisingly begins with the introduction of a totally new character in Cole Young as our point-of-view protagonist. While fan favorite Liu Kang was the hero in ’95, the character is now a supporting player played by Ludi Lin in 2021. And he’s not alone. The new Liu Kang’s cousin, Kung Lao (Max Huang), also gets enough screen time to show off his character’s beloved razor-rimmed hat, which he dispatches one of the movie’s villains with.

There is also the new Sonya, who may have the most complete arc as she strives to be accepted as a champion for Earthrealm, and Jax (Mechad Brooks), who is Sonya’s partner with the chosen one birthmark and who gets a new nasty origin story for his metal arms. And then the new Kano spends as much time working with the good guys as he does becoming a villain in an entirely rushed and unconvincing third act plot twist.

Read more

Movies

Mortal Kombat Easter Eggs and Reference Guide

By Gavin Jasper

Games

Mortal Kombat: Biggest Changes the Movie Makes to the Games

By Matthew Byrd

There are even more villains, most of whom amount to glorified cameos, including Mileena (Sisi Stringer), Nitara (Mel Jarnson), and Kabal (Daniel Nelson). However, they’re all even more perfunctory than Sub-Zero and Scorpion were in 1995. At least the ‘90s ninjas each got a few minutes to show off before being dispatched. Even the ostensible main villain of 2021, the new Shang Tsung, is fairly underserved, left to state banal dialogue from a throne without a throne room, and he’s never allowed to dominate scenes the way Tagawa did so gleefully back in the day.

Unfortunately, this is because the 2021 film has so many characters that it lacks any sense of narrative focus or cohesion. Tan’s arc of wanting to learn his power/arcana to defend his family is as broad and serviceable a hook as Shou’s 1995 Liu Kang wanting to avenge the murder of his brother. But Tan’s Cole Young gets lost in the shuffle after the first act and until the movie’s ending. Character turns like Kano betraying the other heroes similarly feels hackneyed because there is too much noise on screen to really care about who’s making it. Even Kang Lao’s death falls flat. It’s admirable that it’s a good guy fans theoretically should care about (unlike 1995’s token Black character created by the filmmakers to die), but the 2021 movie fails to make the uninitiated be concerned.

Of course there are exceptions. Namely Sub-Zero and Scorpion. Even though Scorpion ill-advisedly disappears for nearly all of the movie’s running time after the film’s terrific opening 10 minutes, Sanada has such presence, and such strong chemistry with Taslim’s Sub-Zero, that their opening salvo leaves you waiting the rest of the movie for Scorpion’s revenge. Taslim is also able to give Sub-Zero some surprisingly tangible, if only hinted at, pathos even after he kills a kid in his first scene and is then forced to act behind a mask thereafter. He’s the real villain of the piece you want to see go down, and his death scene is incredibly satisfying as a result.

It’s probably enough for fans of the games to favor this kitchen sink approach. But overall, less is more.

Round Three goes to 1995.

Fight Scenes

If there is one realm where the 2021 movie truly excels in over the previous film, this is it. And yes, a big part of that is the gore quotient. Whereas the 1995 flick was produced with a PG-13 rating in mind (my elementary school thanks New Line for that), the 2021 movie was able to embrace the gross out charm that made the original game stand out at the arcade all those decades ago. Street Fighter might’ve been first, but only Mortal Kombat let you pull the other player’s spine out.

While that effect doesn’t quite happen in the 2021 movie, almost everything else does. Nitara goes face first into a Kung Lao’s buzzsaw hat, which cuts her cleanly in half; Sub-Zero freezing Jax’s arms and then shattering them in a stomach-churning effect; and instead of going off a cliff, Prince Goro is disemboweled by Cole Young—which almost makes up for the fact that Goro is reduced to a mindless mute this time.

It’s like a highlight reel of fatalities from the video game. But the reason why this film’s fight scenes really stand above the 1995 film isn’t the bloodletting; it’s the action leading up to it. With brutal fight choreography, the new Mortal Kombat shines whenever it lets actors who can actually do the stunts take the arena. That includes Lewis Tan, whose Cole Young mostly fights other MMA types or CG monsters. But it’s especially true for Joe Taslim of The Raid fame. As the villainous Sub-Zero, his moves are lightning quick, even if his powers leave opponents frozen stiff. So when he shares the screen with Tan or Sanada, the action reveals an auhentic flair.

In comparison, the 1995 film suffers a bit from the sin Johnny Cage is trying to dodge within the story: it relies on stunt doubles and tight editing to make the fights exciting. It’s a shame too since Shou is an excellent martial artist, and the one scene he got to choreograph—Liu Kang versus Reptile—has an edge. But much of the time, Shou’s constrained by the direction and editing. Ashby and Wilson-Sampras, conversely, are not actual martial artists, though credit must be given to Wilson-Sampras for doing all her own stunts when getting the role of Sonya at the last minute.

Still, the fights stand taller in 2021. It’s a bit of a shame though that the movie is so heavily edited that it too often hides this fact. Unlike the 1995 ensemble, most of the cast has the moves in 2021, but the editing still feels stuck in the past with its reliance on confounding quick cuts and coverage. During our current era of John Wick and Atomic Blonde this is both a bizarre and disappointing choice. Nevertheless, this is an easy call.

Round Four goes to 2021.

Ending

The final fight was relatively satisfying in 1995. Tagawa is a preening villain, and when the Immortals’ techno “Mortal Kombat” theme plays, it’s a pleasure to watch Liu Kang wipe that smug smile off Shang Tsung’s face. However, the ending keeps going with a Star Wars-esque sendoff to Liu Kang’s force ghost brother, and then the movie undermines its catharsis by immediately setting up a sequel.

In the picture’s final moments, our three heroes, plus Kitana, return to the real-life Thai temple that’s supposed to be Liu Kang’s home. Lord Raiden waits for them there, getting some final sideways cracks in before Outworld’s evil emperor Shao Khan appears like a giant specter in the clouds. He immediately threatens an Earthrealm invasion, despite losing the tournament.

I can attest that in 1995, this was a stunning cliffhanger for eight-year-olds everywhere. But then… Mortal Kombat: Annihilation (1997), one of the worst films of the late ‘90s, happened.

Meanwhile in the 2021 film, we have a much more satisfying death for its villain when Scorpion returns from hell to send Sub-Zero to the hot place. Their fight is much more technically satisfying, and the cliffhanger setup is a lot more subtle. After defeating Shang Tsung’s warriors, if not Shang Tsung himself, the heroes of Earthrealm saved us all without an actual tournament ever occurring. And instead of Outworld cheating in this moment by invading anyway, they retreat. It’s an odd choice since they’ve been cheating the whole film, so why start playing by the rules now?

Even so, it leaves a destination for a second movie to actually head toward. And to tease that fact further, it’s implied Cole Young will now travel to Hollywood to recruit movie star Johnny Cage for a sequel. It’s pure fan service, but the kind that leaves the possibility open for better things to come. Considering we know where the 1995 movie’s cliffhanger leads—to pits of cinematic hell worse than any faced by Scorpion in the last 400 years—this is a victory for 2021 by default.

Round Five goes to 2021.

Final Victor

Ultimately, neither of these films are high art nor do they aspire to be. In some ways, it’s a case of picking your poison between schlock or schlock. Each has advantages over the other, as laid out above, and each is a long way from a flawless victory. Nonetheless, due simply to narrative and tonal cohesiveness, and just more memorable lead characters, I’ll go with the one that actually gets to the tournament this whole damn thing’s designed around.

Game over.

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ playerId: "106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530", }).render("0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796"); });

The post Mortal Kombat (2021) vs. Mortal Kombat (1995): Which is Better? appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/2QUY7IW

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

November 2019 Empire Magazine The Rise of Skywalker Article Transcription

IT ALL STARTED with a Jane Campion retrospective. The Lincoln Center in New York was entering night two of an in-depth celebration of the Kiwi filmmaker’s work when, during a sold-out screening of The Piano, one member of the audience received a text message. He then received another. And another. Hunched down in his seat towards the middle of the auditorium, screenwriter Chris Terrio glanced furtively at his mobile as yet another text pinged to life on his screen. It was from J.J. Abrams. Just like the last. And the dozen or so before that.

It was 10 September 2017, and several hours earlier Terrio had received the first in what would become a torrent of communication. “I’ve just signed on to Episode IX,” it read. “We’re gonna write a new script. Would you consider writing it with me?”

“He didn’t even say the words ‘Star’ and ‘Wars’,” recalls Terrio, with a laugh. “He didn’t have to. I’d been about to go off and direct a small movie, but when you hear Star Wars, everything else goes away.”

Terrio agreed on the spot, planning to join Abrams in California as soon as his schedule would allow. But the texts kept coming. Throughout the afternoon, thoughts, ideas and questions popped up one after the other; Abrams’ frantic thumbs tapping out the first seeds of story and flinging them across the country to his newfound partner. And so, with Michael Nyman’s haunting score swelling around him and a still-buzzing handset in his grasp, Terrio stood up, shuffled apologetically along a row of seats, and walked out of the cinema, leaving Campion’s Oscar darling behind.

[Above image caption: “Director J.J. Abrams, cast and crew confront Klaud, the Resistance’s newest addition, at Pinewood studios”]

“J.J. is constantly brimming with ideas and, in the very best way, he’s very impatient about them! So we just started getting into it then and there. I got on a plane to LA the next day.”