#art's repression haunting the narrative again

Text

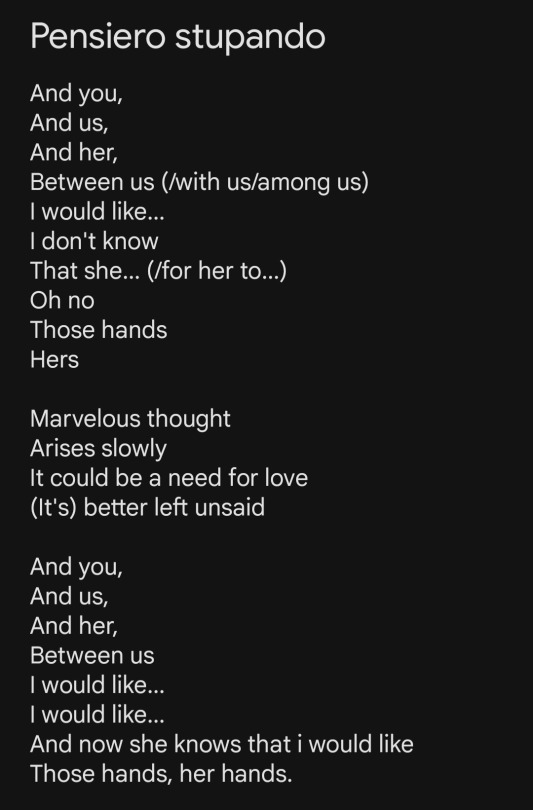

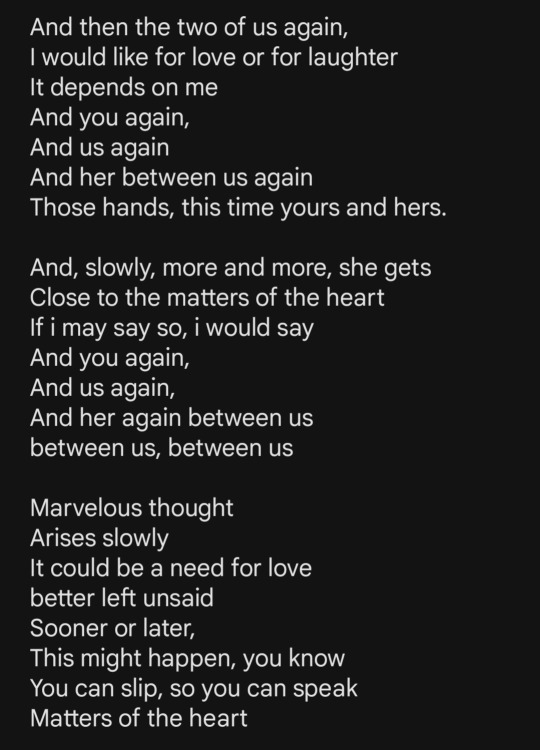

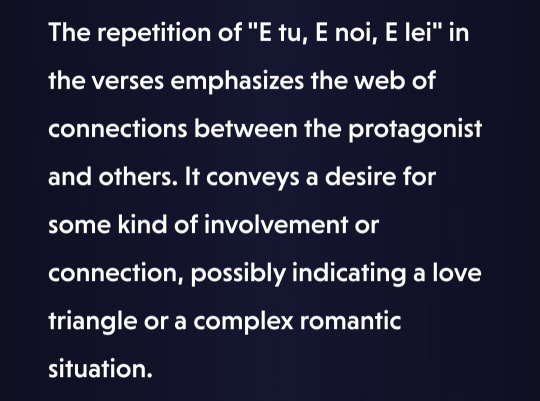

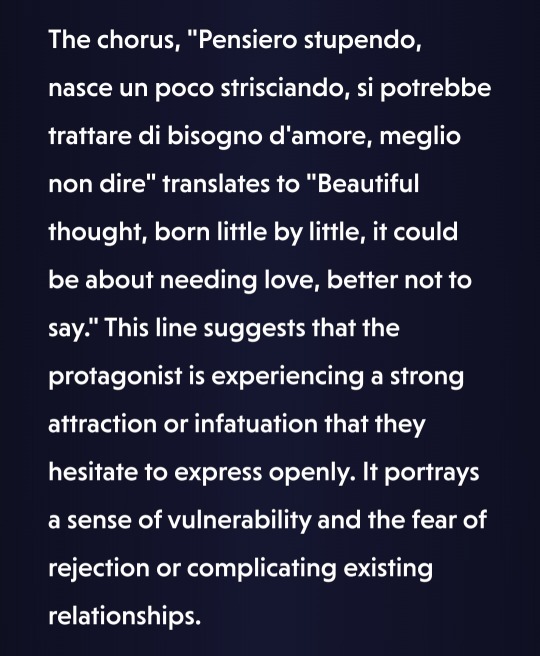

Pensiero Stupendo by Patty Pravo

since nobody talked about it except italian fans: just before the sauna scene, during the storm, a song about a throuple is playing!

and this is so from art's pov and fitting the ending so well. the interpretations of the song are also very interesting. i'll never stop thanking luca for all of this.

#pensiero stupendo#patty pravo#challengers#art donaldson#tashi duncan#patrick zweig#you (the man)=tashi; us (the female singer + the man)= art and tashi; her (the other woman)= patrick#i feel like so many songs in it are from art's pov#art's repression haunting the narrative again#the “now she knows that i would like” and the ending of the song fit the ending of the movie so well

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cotton Mendings — a WIP intro by yours truly

finally doing a proper introduction yayy!! who would have foreseen this .

stage: drafting (rip it's been so long and it's going soo slow)

tags: #wip: cotton mendings ; #aes: cotton mendings

genres: historical fiction, literary fiction

themes and tropes: idealisation and romanticisation of people, queer love and toxic queer relationships, friends to lovers, tenderness and love for the world, hope, grief, obsession, mythological and religious imagery, breaking out of other people's perceptions of you, relearning gentleness after having it beaten out of you, being loved as being known

warnings: emotional and physical abuse, character death and mentioned animal death, period-typical homophobia & transphobia (will add on)

pov: 3rd person past tense

setting: 1920s England

summary: Oscar ignites a relationship with an old friend – charismatic socialite Salvatore – whom he has had repressed love for for years. But despite everything their relationship is haunted by the death of Oscar's brother and a series of portraits simply called Percy, made by a German artist: paintings of a red haired man who appears perfect and soft and yet incredibly, beautifully tragic. It makes Oscar question Salvatore and their relationship and wonder about the life and seemingly inherent sorrow of the subject, while Salvatore grows ever more enticed by ruthless, enigmatic Yvonne. Their separate obsessions grow and push them apart, while at the center of everything is Percy, devastatingly alive and spiteful, trapped in a narrative he did not create. Who is Percy, who is Salvatore, who is Oscar in rotation to them? Does he want to know at all?

characters, notes, excerpt & taglist under the cut <33

characters:

Oscar (he/him, bi): world's #1 most pathetic sad boy. romanticises everything to the point of self destruction. scared of acting on his desires but full of soooo much love. obsessive, incredibly sensitive, artistic, melancholy. also sooo autism.

Salvatore (he/him, bi): charismatic, intelligent, flamboyant, philosophical, hedonistic. he sees everything in a very realistic and nihilistic way. emotionally detached yet surprisingly protective and gentle with the people he loves.

Percy (he/him, bi, trans): babyboy !! baby!!!!!!!! full of so much life and love and poetry. he is very sweet and sarcastic and loves going on little adventures. mentally ill & physically disabled. he's suffered more than jesus but his wonder and whimsy are unmatched.

Yvonne (she/her, bi): hot evil woman❤️ ruthless, vicious and cold. her love is almost violent and repugnant. she only cares about few people but if they are in danger she knows no morality or law. also she's mischievous like a little cat <3

notes: Cotton Mendings is my passion project, my Magnum Opus, my baby. I have worked very hard on it and I've developed the character dynamics and symbolism sooooo much I could talk about them for hours. It all started with the song Angie by The Rolling Stones, but it has strayed very far from its original concept (actually Angie isn't even on the playlist — it is now completely a product of my obsession with The Smiths I'm afraid). It has helped me through so much and I will be very happy if people like it :] I love my horrible insane bisexuals. Why is everyone bisexual, you ask? well. I ❤️ bisexuals.

excerpt:

He thought again of Percy, of the way he glowed as if coated in honey and sunlight, the sweet smile on his face. What if Percy had spent his life failing at it, too? Trying to be the perfect picture of a beautiful boy. Turning hazy and translucent, like a ghost, from trying. And those few minutes with him, how the light extended and held Oscar too, how Percy was perfect and beautiful but couldn't possibly be only that. How they were both an image without a body.

(general) taglist: @ribelleribelle @talesofsorrowandofruin @writing-is-a-martial-art @alexwritesfiction @aether-wasteland-s @sculpture-in-a-period-drama @phantomnations @olimpias (ask to be added or removed)

55 notes

·

View notes

Note

"recoiling from self-recognition through the other etc etc" please talk about this more 👀

ohh i'd love to! thank you anon, i'm desperate to unleash these thoughts on someone. sorry if they're a bit long, i unfortunately care deeply about stede and izzy and the Things They Share.

to start with: stede and izzy are obviously extremely different people. that's like, 90% of where their conflict stems from, and i'm not trying to argue that they're in any way on the same journey, so to say, from a narrative point of view. still, i think it's fun to wonder if there isn't some element of inward cringing to their very visceral hatred of one another. these two loathe each other before they're even competing for anything substantial, certainly before it becomes clear that they're both in love with ed. so what else is there about the other person that sets their teeth on edge so much? in part, i think the polarity's off; they're quite similar in a few ways that neither of them likes, or cares to look at too hard.

a few things izzy and stede have in common, some more and some less significant, all of which notably also set them apart from ed and the rest of the crew:

they're neat – ed cares about how he looks, so do all the crew, to some extent, but most of them tend to have some level of artful dishevelment going on. the crew don't really have the means to not look grubby, ed does, but still wants his appearance to seem effortless, but stede and izzy visibly care. stede with his meticulously coordinated wardrobe and outfits matched to occasions, izzy with his perfect posture, his One outfit and its neatly tied cravat and securely placed ring, both of them with not a single hair out of place. looking at izzy, you just sort of know that this man would love a manicure. you'll just never hear him say it.

they're intense, in ways that maybe don't seem immediately similar because their intensity has such different expressions. you can tell from izzy's stance, from his outbursts and his snappiness and bullying how tightly wound he is; with stede, it really tends to show more in his thin skin, his over-eagerness, his bossy little fits with the crew. “is he always this highly strung?” ed asks about stede, and who might that make him think of?

in connection to that last point: they're both so repressed, and so disastrously bad at saying what they want out loud. barely anyone on this show has a tighter lid on their more intimate emotions than stede and izzy do between eps 1 and 9. two events s1 shows us in direct succession are 1. izzy trying to manipulate ed into killing stede, then stabbing stede himself, in order to separate him from ed; and 2. stede contriving an entire treasure hunt in order to get ed to stay with him. these aren't equally deranged responses, izzy clearly takes the cake here, but they're both very elaborate ways of failing to say one and the same thing to ed, which is basically just don't leave me.

to end on a lighter note, they're extra. their entire first meeting is them trying to out-drama each other (and not hating it at all, for a second there). we only see this a few times, but whenever izzy thinks he has the upper hand, he's kind of funny and almost like. playful? in a way that i find mostly comparable to stede when he's planning his fuckery in ep 6. so when the two of them meet in ep 2, they're actually so fun and dynamic together! izzy's silly little flourishes when he shreds stede's shirt, stede's stupid haunted island story, “this isn't over mr bonnet” with that evil little smile. “good, 'cause i kind of enjoyed it”. they both did. i know this

i think especially on izzy's part, there's an element of “i have that same weakness, but i repress/handle/ignore it as any man/pirate should” to his abject loathing of stede, a begrudging of liberties taken that's not entirely without envy. stede cares a lot less, which is where their differences come in again; stede is nowhere near as obsessive, possessive, or angry as izzy. he is, for all his hard-headedness, a lot more well-adjusted, and has no real reason to single this one man out as the bane of his existence. but i still think their few similarities play some role in their (imo endlessly entertaining) relationship – they did, after all, fall for the same complex, difficult, layered and loveable man.

#they're soooo good together and i mean that in a way a roman plebeian means it re: the gladiators mauling each other for his entertainment#i hope s2 puts them on a desert island together. i hope izzy is incapable of dying#our flag means death#asks#anon#ofmd

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beyond the Bottle Episode- How Inside No.9 uses a single location

Contains discussion of plot points/ spoilers for Twelve Days of Christine, Bernie Clifton’s Dressing Room, Diddle Diddle Dumpling, Tom and Gerri, Love’s Great Adventure, Misdirection, Lip Service, The Stakeout , La Couchette, Nana’s party, Last Night of the Proms , To have and to hold

One of the many interesting aspects of Inside No.9 which many commentators has praised the show for is how each episode manages to tell its story within a single location. It could be argued the location is a character in each story in its own right. I cannot possibly do justice to the many ways the show utilises single locations to tell its various narratives but hopefully this essay will give an interesting introduction.

There is a convention on television of setting an episode of an established show in a single location. These are referred to as ‘Bottle episodes’. Many successful television shows (particularly comedies) have a bottle episode, and they can be found across genres with episodes such as Breaking Bad’s ‘Fly’, Mad Men’s ‘The suitcase’ Dr Who’s ‘Midnight’ and a personal favourite Peep Show’s ‘Neither zone’. Bottle episodes are often used to explore the relationships between central characters in more depth and occasionally allow long held secrets to be revealed. These points are all worth bearing in mind when examining how Inside No.9 utilises single locations/spaces.

The show works with several genres (sometimes within the same episode!) such as comedy, horror and psychological thriller. These genres routinely use a single location to help to create a particular atmosphere, explore how characters interact and play with narrative forms- all things Inside no. 9 do wonderfully. Pemberton and Shearsmith have discussed how these genres, particularly horror, have informed their work. Directors such as Hitchcock (who made films such as Lifeboat, Rear Window and The Lady vanishes ) have utilised single locations in their narratives to create suspense and explore character dynamics. The concept of Inside no.9 grew out of the Psychoville episode ‘David and Maureen’ was inspired by the Hitchcock film ‘Rope’ which is set in a single location. Pemberton and Shearsmith have also performed extensively on stage and bring this experience to their ability to set a story within a single location. It has been commented that many episodes would work well on stage.

Pemberton and Shearsmith also build on the traditions in the horror genre of using a single location such as a haunted house to create atmosphere and tell a compelling narrative Indeed the horror episodes of ‘Inside No.9’ such as ‘The Harrowing’, ‘Séance Time’ and ‘ Private view’ acknowledge and pay tribute to these horror conventions.

Spoilers below

In episodes such as ‘Sardines’, ‘Nana’s party’, ‘Last night of the Proms’ , ‘Empty orchestra’ and ‘The referee’s a wxxxer’ the single space represents the claustrophobic and dysfunctional relationships of the characters. It also represents how central characters are trapped by their secrets and the unhappiness of their lives. This can still lead to a considerable amount of comedy through the frequently uncomfortable interactions of the characters and the various misunderstandings that occur. It is no accident that three of the five episodes listed occur at family parties. These episodes explore the tensions and difficult dynamics of families and the impact of a mixture of enforced joviality and too much alcohol of these events can permanently have on family relationships.

In episodes such a ‘La Couchette’, ‘Hurry up and wait’ and ‘Zanzibar’ we see strangers who otherwise would not have met thrown together in a small space, and the comedy and tension that ensues from the interactions that result. It is interesting to compare ‘La Couchette’ to Hitchcock’s ‘The lady vanishes’ – both of which are set on trains and which deal with characters who are thrown together dealing with a moral dilemma.

In episodes such as ‘The Riddle of the Sphinx’, ‘Tom and Gerri’, ‘Cold Comfort’ and ‘Simon says’ the single space becomes representative of the psychological conflict between the main characters, with control of the space itself being one of the areas of conflict. It is worth noting several of these episodes revolve around a character allowing a stranger into their lives by allowing them into a personal space such as their home, and the subsequent upending of their lives.

Some episodes also uses a single location to explore the psychology of its central character.

In Diddle Diddle Dumpling the house reflects David’s emotional state. It is all too neat and ordered, reflecting David’s emotional repression and failure to deal with his grief. The house also is filled with twinned and paired objects (Is this deliberate on David’s part?). It has been noted that ‘Diddle Diddle Dumpling’ is almost Kubrickian in the care and attention of the set design and uncanny atmosphere it creates. This is probably down to director Guillem Morales.

In ‘Tom and Gerri’ the deteriorating state of the flat reflects Tom’s worsening mental state. The growing number of empty alcoholic drink cans and bottles, junk food containers, and general mess reflect Tom’s growing dependence on alcohol, depression and lack of self -care.

Two of the most interesting uses of the single location are ‘The twelve days of Christine’ and ‘Bernie Clifton’s dressing Room’.

‘The Twelve days of Christine’ uses Christine’s flat as the backdrop for memories of significant moments of her life. The meaning of the flat changes as her situation in life changes. It goes from a carefree single pad to family home to a place where she must raise her young son alone. It is worth noting we see the day Adam moves in and apparently moves out (Jack’s first day at school).

‘Bernie Clifton’s Dressing Room’ uses the church hall as a space where Tommy and Len discuss and reflect on their different experiences of their career. The church hall is filled with mementos and props from Tommy and Len’s career and becomes the place Tommy tries to make his peace with his past with Len and how their personal and professional relationship ended. It is very probable Tommy set up the room in the particular way to prompt these memories (We see Tommy moving items around in the opening sequence). Just to discuss the specific use of location in a few other episodes.

I have previously written about ‘The Stakeout’. But just want to discuss again how in my opinion one of the central themes of the episode is how men relate and interact with each other. Thompson and Varney’s relationship plays out in the confined space of the police car.

In ‘Love’s great adventure’ the Mowbury’s house (specifically the kitchen) represents the Mowbury family itself and the strength of their commitment to each other. Patrick will always be made welcome into the family home in-spite of his problems and Alex will find support and company to help in his grief there.

In ‘To have and to hold’, the actual house itself conceals a major secret. The whole foundation of Adrian and Harriet’s marriage is quite literally compromised by what is at its foundations.

In ‘Lip Service’ the hotel room with its slightly sleazy and uncomfortable atmosphere of the hotel helps us understand Felix’s unhappiness and lonliness. It also puts the lead character into a space he is not familiar with which in part helps bring about events at the episode’s conclusion.

Sets are frequently full of detail, helping to add information about the characters and the situations they are in. In ‘The Riddle of the Sphinx’ the props reflect Prof. Squire’s long and illustrious career. In ‘Last night of the proms’ the clutter of the house reflects a family which is burdened by difficult debates about national identity and destiny and which is trapped in its past. Stubagful in his review of ‘Misdirection’ makes the point the fact we are given so much to look at in Neville Griffin’s studio it helps distract us from what is actually happening and how this complements how the episode comments on the art of the magician.

Inside No.9 continues to find interesting new locations to set its stories in and continues to show how you can use a single location to tell a compelling story.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Civilians Announces Tenth Annual R&D Group

The Civilians will present the newest members of The R&D Group, marking the Group's 10th season, and The Civilians 20th Anniversary Season. The R&D Group is comprised of playwrights, composers, and directors who work together as a writing group for nine months to develop new plays and musicals. The season culminates in the Findings Series, a works-in-progress reading series anticipated taking place in June 2021. The artists were selected from a competitive application process. The open call received a record number of 268 applications, a 60% increase from last year.

The members of The Civilians' 2020-21 R&D Group are Galia Backal, Nana Dakin, Isabella Dawis, Jacinth Greywoode, Jaime Lozano, Emily Lyon, AriDy Nox, Reynaldo Piniella, Tylie Shider, Tidtaya Sinutoke, Rachel Stevens, Ken Urban, and Noelle Viñas.

Led by R&D Program Director Ilana Becker, the artists share work as it develops, discuss their creative processes, and provide a community of support for one another. Each project develops according to its unique methods of creative inquiry, offering new approaches to the idea of "investigative theater." Methods may include interviews, community engagement, research, or other experimental methods of inquiry. The artists will meet twice a month, virtually.

"The sheer talent and curiosity we encountered in this year's applicants proved exceptionally heartening. This season's R&D Group artists, in particular, inspired us with their visionary and deeply personal approaches to questions that demand illumination," said Becker. Artistic Director Steve Cosson added, "I am overjoyed to mark the 10th Anniversary of The Civilians' R&D Group with these exceptional artists; I'm immensely excited as they embark on the process of developing these vital new projects."

Ken Urban's project, THE MODERATE, joins the group through The Civilians' new work development program; his play is commissioned by the EST/Sloan Project, developed by The Civilians, and will receive its first reading at EST. This season, Cosson and Becker will also hold two virtual roundtable sessions with Finalist Directors in order to better get to know their work, and to expand community.

The 2020-21 R&D Group projects are as follows:

SUNWATCHER

Libretto by Isabella Dawis, Music by Tidtaya Sinutoke, Directed by Nana Dakin, with support from Producer/Cultural Consultant Ikumi Kuronaga

SUNWATCHER, a Noh-inspired musical, is the story of astronomer Hisako Koyama (1916-1997) - intertwined with the ancient Japanese myth of the sun goddess Amaterasu, in a retelling inspired by the structure of classical Noh theatre. Hisako was a woman with no formal scientific training - also a survivor of the 1945 US air raid of Tokyo, the deadliest bombing in history - who managed to rise to the stature of Galileo. She did so by drawing the sun in painstaking detail every day for 40 years, a landmark achievement for solar science. SUNWATCHER is a celebration of Hisako's extraordinary dedication to ordinary observation, reminding us how seemingly small acts can have an immense impact over time and space.

BLACK GIRL IN PARIS

Music by Jacinth Greywoode, Book and Lyrics by AriDy Nox

BLACK GIRL IN PARIS is a musical about one of the most famous and least known black women in the American historical canon: Sally Hemmings. It hones in on her years spent in Paris, a point in her life where she both had the most access to freedom ever afforded her and the beginnings of the relationship that would forever define her legacy. Black Girl in Paris seeks to explore the inherent contradictions of an enslaved young black woman held in bondage in a city where slavery has been outlawed, under a man widely considered to be one of the architects of one of the greatest articulations of the necessity of freedom in the western world. It also centers an ensemble cast of Ancestors who chide and guide Sally along her journey, interweaving fables and history to craft the nuanced world Sally is forced to grapple with. At the heart of this musical is the question "What does it mean to be free?", a question black Americans have been grappling with since the original kidnapping and enslavement of Africans for The American Project.

DESAPARECIDAS (Working Title)

Lyrics and Music Jaime Lozano, Directed by Rachel M. Stevens, Co-Created by Lozano and Stevens

Told through the lens of Mexican folklore, our story explores the psychology behind societal suppression and the strategic erasure of female voices in the fight to end gender-based violence and the killing of women and girls. A female ensemble assumes a community of characters in a tapestried play of dramatized accounts, fictionalized scenes and musical sequences to unearth and dismantle the moral behind the 'myth' of violence against women.

DISSENTARY

Written by Reynaldo Piniella, Directed by Emily Lyon

Tasked with escaping your neighborhood, you inevitably run across environmental hazards that impede your progress. Especially if you're Black, Indigenous or Latinx. Dissentary takes inspiration from the classic game The Oregon Trail and adds an environmental justice lens; your group can do one of two things - leave in pursuit of clean air, water and healthy food, or stay and defeat the corporations focused only on profits. Dissentary will both be a participatory theatrical piece as well as an accompanying card game that will allow people to play the game off-line themselves, thus giving access to people who normally don't have access to the arts.

RESET: RACE and CULTURE CONTACTS in the MODERN WORLD

Written by Tylie Shider

an investigative work of theatre

about how incidents between police and black Americans

continues to reset race relations in the country.

THE MODERATE

a new play by Ken Urban, directed by Steve Cosson, commissioned by the EST/Sloan Project and developed by The Civilians.

ACCEPT. ACCEPT. REJECT. ACCEPT. REJECT. For a minimum of eight hours a day, with a target of at least 2,000 videos a day, Frank evaluates the videos and photos uploaded on the world's largest social media site. What Frank sees, he can't un-see, but he soon realizes he has the power to change the world. Playwright Ken Urban and director Steve Cosson will interview scientists, researchers and policymakers in order to dramatize the hidden human cost of the internet and imagine a future when a free exchange of knowledge and information is possible again. This project is an EST/Alfred P. Sloan Science & Technology Project Commission.

EL CÓNDOR MÁGICO

Written by Noelle Viñas, Directed by Galia Backal

El Cóndor Mágico examines the events of Operation Condor, the US-backed campaign of right-wing dictatorships and repressive regimes in South America throughout the 1970s-80s via oral history, research, and satire. It will also explore the American fascination with magical realism, a Latin American narrative tool rooted in history in a region where people have been known to "disappear," problems miraculously go away, and corruption can serve as a curtain behind which history does tricks. Research will unravel how the political imprisonment of over 400,000 people, varied intimidation/torture tactics taught by the US, and unknown thousands of "disappeared" people set a precedent for relations between the US and Latin America that haunt us today. With an eye on Operation Condor's long shadow and impressive wingspan, it asks: who is the magician behind the "magical realism" when it comes to the relationship between Latin America and the US?

FINALISTS

In honor of the overwhelming amount of talent and curiosity displayed amongst this year's applicants, The Civilians are pleased to share the exceptional finalists considered for this season's R&D Group:

Finalist Projects were proposed by Calley N. Anderson; Masi Asare; Helen Banner; Aaron Coleman; Sara Cooper & Kira Stone; Annalisa Dias; Dominic Finocchiaro & Stephen Bennett; Franky D. Gonzalez; Suzy Jane Hunt; Rachel Gita Karp, Ben Hoover & Jacob Russell; Divya Mangwani & Kate Moore Heaney; Talene Monahon & Adam Chanler-Berat; Brett Robinson; Dominique Rider & Nissy Aya; Marcus Antwan Scott, Ryan Kerr, & Dev Bondarin; David B. Thomas, Nick Hatcher, & Sheridan Merrick; Xandra Nur Clark; and Sim Yan Ying "YY" & Alvin Tan.

Finalist Directors are é boylan, Britt Berke, Matt Dickson, Joan Sergay, Noam Shapiro, Emerie Snyder, Leia Squillance, Alex Tobey, and Michael T. Williams.

1 note

·

View note

Text

“Absence, darkness, death: things which are not”: 14x18 watching notes

“What’s Deal with Catharsis?”

Let’s talk about catharsis. 13x04 has been haunting me since it aired. I couldn’t get over Dean sitting on a therapist’s sofa asking “So what’s the deal with catharsis?”. I know it’s obvious but it is also a dramatic term and we are hardcore missing some catharsis in this show. Essentially, it’s the purging of negative emotions that are typically repressed which, in drama, enables renewal or restoration. One of SPN’s narrative problems, for me, is that it gives us precious little in the way of catharsis. There are notable exceptions (12x22 when Dean confronts Mary in his dream, for instance) but for the most part negative emotions are repressed, sublimated, and remain unaddressed.

This is especially (haha, autocorrect turned that to “epically,” which is also true) for Dean and Cas. And it’s not sustainable. We need some purgation of their negative emotions, we NEED them to know crucial bits of information that reveal their true feelings instead of repressing them: Cas killed a million Deans but Dean doesn’t know! Dean was nihilistically depressed when Cas died but Cas doesn’t know! Cas sacrificed his soul (and happiness) to save Jack and Dean doesn’t know! The layering of dramatic irony is all very well and good, but we need to stop it at some point.

“A quintessence even from nothingness”: Absence and Negative Space

Do I actually think that will happen soon? No. I was interested in “Absence” being the title of this episode since absence is defined by the things it is not. Cas explains it in terms of Jack--not bad but the absence of good. And that’s kind of where we are with DeanCas too. It’s not definitively one thing (romance) but it’s the absence of any other convincing explanation. If they aren’t these other things--brothers, friends, war buddies--then what are they? “Absence” also refers to Mary, of course, who was absent from their lives once and now is again to be experienced not as a person but a lack. Their whole maternal relationship is defined by feelings of loss and absence so in a sad and terrible way it’s returned to normal. SPN is full of things that are not definitively one thing but which are NOT a bunch of other things and, in all cases, the slipperiness of the definition is itself the narrative problem.

SHAMELESS RENAISSANCE POETRY PLUG please go read this poem by John Donne on the winter solstice, which is all about death and renewal:

Study me then, you who shall lovers be

At the next world, that is, at the next spring;

For I am every dead thing,

In whom Love wrought new alchemy.

For his art did express

A quintessence even from nothingness,

From dull privations, and lean emptiness;

He ruin'd me, and I am re-begot

Of absence, darkness, death: things which are not.

It’s called, “A Noctournal upon St. Lucy’s Day, being the shortest day” and I adore it. Also...it (along with a lot of Donne) seems so SPN-appropriate that I think he would have been a fan. (Donne is the preacher who wrote the “no man is an island” sermon and asked “not for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee”. He had a massive command of rhetoric, yo.)

Anyway, “absence, darkness, death: things which are not” is what the title immediately made me think of. Jack promised a new beginning, forged from the darkness that was Lucifer, and part of me is still convinced that this is what he’ll bring, despite appearances. We all predicted early on that he’d have a moment to go darkside and, yeah, this is it! His choices would also matter--because this is Team Free Will--but it would then be his choice to act evilly. Even if that happens, though, he can choose not to and part of me thinks he will. We don’t have other Big Bads on deck for the end of this season/start of S15 so I’m assuming episodes 19 and 20 will focus on the Jack problem until it reaches a crisis that carries us through to the summer. But how they will resolve it, I hope, has more to do with the power Jack holds to create as well as destroy. Or maybe Chuck’s reappearance will set this balance off? We’ll see.

Also, “absence makes the heart grow fonder,” which I’m going to keep an eye on as the season goes on.

Destiel is Pain

It’s fascinating that the promos were edited to suggest that this was an episode with MAXIMUM DEANCAS DRAMA OMG!! when it kinda...wasn’t. I know @occamshipper pointed out that they edited it just like a het romance drama, centering on the “you’re dead to me” and building up the angst and tension. And that was there, but it wasn’t everything. PR isn’t showrunning, yes, but it does mean something; it means they think the GA cares. And that’s kind of a big fucking deal at this point because what the GA cares about determines what we’ll see more of in the show. It’s not definitive at all. But it’s a trend and an important one that some fine folks have been tracking for a while.

The “you’re dead to me” was not not a big deal--and I had hoped very much that we’d get an apology along the lines of, “Cas, I’m sorry. What I said--I put the whole Jack thing on you and that’s not fair. I did the same thing. We all did. You didn’t fail us.” Let’s cross fingers and hope we hear that the next time they talk (since Sam stopped Cas from trying to give comfort in this episode...pray4Sam who was SUCH a brother-in-law/marriage counselor here). But it’s a Buckleming next so I don’t hold out hope. In any case, it’s a big deal because while Sam now knows that Dean doesn’t consider the whole thing Cas’s fault Cas doesn’t know that and will continue to go on thinking that a) he’s only good the Winchesters insofar as he’s “useful” and b) he’s a failure to Dean specifically. THAT’S TERRIBLE AND WE NEED TO CORRECT IT IMMEDIATELY!!

But we won’t correct it immediately because the show is riding DeanCas tension as basically the A plot at this point. Building angst to a breaking point surrounding Jack just emphasizes that. Jack caused our biggest DeanCas rift to date, both by Cas’s unwavering support in him that led to betraying Dean (running off with SOME WOMAN after stealing the colt from under his pillow after the mixtape scene, layering romance trope on romance trope) and by coming into existence the same day Cas died. Jack’s essential good or evil nature has been the biggest disagreement in their relationship for 3 seasons now so it makes sense to center a crisis on it.

And Dean doesn’t even KNOW about Castiel’s deal with The Empty! He doesn’t know that Cas traded his soul to return Jack’s to earth...only to have it be destroyed. True, The Empty said it would only come when Cas was happy and the thick angst we have now doesn’t suggest he’ll be happy anytime soon, but I think Dean and Sam are about to find out about the deal and Dean’s about to be pissed the fuck off at Cas for doing something SO STUPID (so like a Winchester). Maybe in the same conversation where Dean apologizes we can have Cas tell him the truth about the deal? Like, can they talk please? The real villain was miscommunication all along though, right?

Zombie Moms

Just a little sidebar to tell myself to return to 13x12, “Various and Sundry Villains” (a Yockey ep) and the two witches who were able to get Rowena the Book of the Damned (crucial in this episode, as Rowena unwittingly leaves it with Jack) try to resurrect their mom and bring her back...wrong. Because necromancy is extremely tough (and why didn’t Jack need any victim blood to bring Mary back the way that the Plum sisters did??) what they bring back is just a murderous simulacrum that was, honestly, what I was afraid they were planning to do with Mary. I’m relieved that they didn’t.

Both episodes owe a great debt to the Buffy episode “Forever” (5x17) where SPOILERS FOR BUFFY after their mother’s death her younger sister attempts to bring her back, only to realize at the last second that it’s not possible and the thing outside the door is a horror. It’s a very intense episode about grief, following “The Body” (5x16), one of the most devastating TV episodes to ever air. It was obvious to me that Yockey et al. were using that episode in 13x12, though not totally clear how. They even cast the zombie Mom like Joyce!!

In any case, in 13x12 the sisters’ refusal to let their mom go was an example of the toxic sibling codependency that Rowena used to kill them (as they beat each other to death, one using a hammer just like demon!Dean). In 14x18 Jack’s desire to bring Mary back is an example of his being unable to cope with the reality of his actions and his fear of losing the Winchesters. That’s not toxic codependency, but it is a refusal to go through the stages of grief. There’s definitely something going on here--and going on about Moms--that I can’t pick apart now but want to (or hope someone else will!!).

On which note, my chemo fatigue has found me so I’m gonna sign off. Apologies for typos or lack of clarity. I have really missed doing episode notes, though, so maybe I’ll be back to it soon. I’m psyched to see how this season wraps up, how about you?

#14x18#14x18 meta#14x18 analysis#watching notes#what's the deal with catharsis#catharsis#negative space#the empty#absence#destiel and the ga#pr is not showrunning#but this is intriguing#miscommunication#USE YOUR WORDS#let dean and cas have a conversation 2kforever#grieving!dean#castiel's deal#13x12#btvs#spn and other shows#spn and btvs#pop culture parallels#spn and literature#john donne#prof me#WILL GET YOU ALL TO LOVE POETRY IF IT KILLS ME#jk but I hope you do#nerd me#season 14 speculation#season 15 speculation

69 notes

·

View notes

Photo

BELT BOW CAPE

by Réginald-Jérôme de Mans

Three different superhero trajectories, represented by their accessories, resonate with me. The first, the essential human superhero. The second, the hero that could have been – the hero who could have indicted the system. The last: unexpectedly, the one who did. Rather astonishingly, it’s by far the sunniest of them, the CW’s Supergirl, who most thoughtfully and deeply engages with the current dark moment of our reality. Her metonym – her cape – symbolizes both her protective role and the inclusion the last season of her show espouses.

Superheroes have been the idiom of entertainment for at least a decade, after all: movie, network TV and streaming franchises generated billions of dollars and whirls of sometimes conflicting continuities. They supposedly fight for right in a world that is ultimately binary: good confronts evil reduced to and personified by a couple of arch-villains, defeated in the final minutes. A part of their outfits – each a vital accessory – serves as a shorthand for their respective personae and their relations to our current dark historical moment.

Batman, of course, is the first. His utility belt makes him the definitive #iGent superhero: he has an accessory that prepares him for every occasion, the endless control over every variable that requires endless wealth, the same wealth that protects him from discovery and accountability. Also appealing to the #iGentry is the playboy pose he adopts in his civilian identity to deflect identification with the hardened crimefighter of the dark streets. That is what Batman is: he fights crime, the symptoms of a problematic system, and external threats to that system (the Joker, Ra’s al-Ghul, Bane), but no amount of Wayne Foundation charity can resolve the problems inherent to that system, exploitative as it may be.

Green Arrow has often been treated as the poor man’s Batman (Batman when TV execs can’t get the rights to use him) in various superhero narratives. Similarly wealthy, similarly profligate in his public persona, wielding instead of a belt a bow, an offensive weapon firing a collection of arrows as diverse as the contents of Batman’s belt. But in the 1970s Denny O’Neil and Neal Adams leaned into and updated the Robin Hood association of this green-attired and goateed figure. They made Arrow raise, if not always satisfactorily address, the structural issues that give rise to lawlessness and inequality. If Batman’s drive is vengeance for the murder of his parents in a mugging, Green Arrow’s became rage at a system that exploited the most vulnerable, a system that created the crime that plagued 1970s cities and that reinforced divisions between rich and poor – even if the narratives sometimes foundered in 1970s clumsiness.

This social conscience manifested early and briefly in Arrow, the CW network’s version of Green Arrow, where the hero returns to eliminate the powerful establishment figures he believes responsible for exploiting his city and its most vulnerable. Debuting in the wake of Occupy Wall Street and the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, the first season liberally throws around terms like “one-percenters.” Over the ensuing six or so meandering seasons, that social sensibility, already weak, sublimates. Like in the comic books, the CW Green Arrow loses his fortune, but only in a rich person’s version of poverty: still able to travel to the ends of the earth at the drop of a hat to battle evildoers; able to build a nuke-proof state-of-the-art bunker; able to pay for boarding school for his son. Seasonal plots and archenemies have afforded but squandered ample opportunity for the CW Green Arrow to face if not address systemic societal crimes. The most recent season raises but then recontains issues of prison abuse and decarceration, and has Green Arrow battle a terrorist financier played by Highlander great Adrian Paul. The headlines of the last decade prove that this figure could just as easily have been a mainstream international banker rather than an illicit off-the-books marginal figure. He never again attacks crime at a societal level, meaning that his vigilantism, like that of Batman, is inherently fascistic, the more so as Green Arrow actually becomes a police deputy (in costume), in other words an instrument of structural repression.

If Superman’s symbol is his shield, the “S” on his chest, that of his cousin Supergirl (at least in her current TV incarnation) must be her cape. His shield and its symbol are personal (in canon a heraldic device of Superman’s family). Supergirl’s cape is protective against all weapons, and over the course of the series also becomes her secret weapon. Multifunctional, both drapey and inflexibly solid when needed. Capacious: like her heart and her mission it contains millions.

Supergirl is an alien, unlike Batman and Green Arrow. They are the ultimate insiders in their secret identities. Their wealth means they have power and access within the system. Supergirl has neither in her civilian persona, only physical – not political -- invulnerability as Supergirl. The writers of Supergirl the show have leaned into that alienness over its seasons, culminating in the season just ended that with surprising thoughtfulness raises issues of alienness, xenophobia and institutionalized bigotry.

Aliens in Supergirl are literal extraterrestrials from all over the galaxy, often refugees fleeing persecution, some better able to pass as human than others, some better behaved than others. Destruction caused by the superpowered aliens like Supergirl and many of her alien enemies have turned some humans against aliens. Other humans have never lacked for good old-fashioned racism, or opportunistic grifting. Drawing on all three motivations, perhaps, is the galvanizing Agent Liberty, a charismatic erstwhile academic turned masked rabble-rouser and, later, chickenhawk member of the government: in short, a lightly fictionalized version of certain pretentious scoundrels from the current administration.

Various other characters set out different approaches to confronting Agent Liberty’s state-sponsored pogroms: J’onn J’onzz (Martian Manhunter) is haunted by his own escape from genocide but tries (and fails) to peacefully oppose this; the human vigilante Manchester Black readily, nihilistically, engages in the same sadism as Agent Liberty’s followers to try to defeat them.

Agent Liberty’s rise turns out to be a smokescreen for corrupt members of the government, and those corrupting them, to divert attention from their other activities and neutralize alien superheroes at the same time. Supergirl, with her superpowers, and her reporter alter ego Kara Danvers, with access to the media, ultimately triumphs, with the support of a diverse network of alien and human friends: her adoptive human sister; the transsexual alien superhero Dreamer (whose name can’t be coincidental); the time-travelling alien android and reformed supervillain Brainiac 5; and a human friend energized with alien superpowers.

Of course, the conventions of a network superhero show, at least a CW network show, require a neat resolution. As soon as Supergirl and her friends publicly expose the corruption of those in power, it appears all government has been cleansed of these hatemongers and evildoers. And the crimes whose exposure drove the villains, up to the President of the United States, from power were not so much espousing xenophobia and putting aliens in concentration camps, but conspiring with American’s enemies. As we know, even evidence of that leading to actual repercussions is wishful thinking in the real world today. It is hard to say, as Supergirl does, that “[t]he fourth estate saved the day” when it in fact got us to this place. With Arrow, a dream of social engagement disappeared. Supergirl reminded us of a hope as distant as the fragments of a fictional Krypton.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Never Look Away (2/3) - Review

LOVE & CREATION IN A WORLD OF AUTHORITY & REPRESSION

I’m beginning my series of reviews with a special Film Trio centered around the theme above. The three films reviewed and discussed are:

1) Cold War; 2) Never Look Away & 3) If Beale Street Could Talk.

Having seen those three films with a few weeks interval, I feel they shared really great similitudes in their treatment of love, of the artist’s place in society and of the importance of memory.

I hope you’ll enjoy what I finally came up with!

Never Look Away (2/3)

Florian Henckel Von DonnersMarck, 2019

Historical Dramatic Romance

After Cold War (see previous review), here comes another interesting take on an artist’s life during wartime period - but from the German side this time. Loosely based on Gerhard Richter’s art and life, Never Look Away(Werk Ohne Autor– Work Without An Authorin its German title) follows the artistic and love journey of a young aspiring painter, whose aunt has been the victim of Nazi atrocities during the War.Profoundly scarred by the locking of his aunt Elizabeth in a sanatorium and then her sending to a certain death, Kurt decides, from the day he witnesses her arrest, to study art and make painting the center of his life. But what he doesn’t suspect is the meeting with the love of his life, Ellie, who’s also gonna act as the main revelatory and instigator of his art - for her father seems to hide more than one secret, one of them being linked to Kurt’s very own past…

The film is set in Nazi Germany during Kurt’s childhood and then moves on to post-war East Berlin where the hunt for war murderers begins.

Following Kurt’s evolution throughout the years, focused on the period from childhood to his very first exhibition, the three hours and nine minutes of Never Look Away never feel like it and actually allow for the emotions, the characters and the sensations to settle deeply and durably. It is exhilarating and reassuring to see that some filmmakers still fight and stand for their artistic vision by daring to release in the movies such long films, as Titanic or King Kong in their time. By not taking shortcuts or simplifying his narrative, Von Donnersmarck remains close to his characters and allow for us to fully live with them and feel like a part of their very intimate journey, in the middle of a troubled era and family secrets.

Similar to Cold War is this perfect balance between historical intrigue and love story, the subtle combination of the inner struggles linked to the combats of a nation to reestablish the truth and keep the memories of the victims alive.

One of the (many) strengths of the film, just as in Cold War again, is the couple and their love relationship. Beautifully shot, alternating between really crude - yet poetic – scenes and more suggesting ones, Florian Henckel and his cinematographer Caleb Deschanel (known for his work on The Passion of the Christ) really embrace the fiery and burning passion between our two lovers, which you know from start are bond for life – just as were Wiktor and Zula.

Tom Schilling’s fervor and mad dog attitude finds the perfect match with Paula Beer’s wit and softness as her dedicated lover – and later on, wife.

Both in an obvious chemistry, the film then seen through their eyes (mostly the ones of Kurt of course) is an incredible gem and an absorbing intimate quest about what makes one an artist, what really lies behind a work of art and how personal traumas can help through works of art reestablishing a sense of truth and emotion. All of these, which could just sound like a boring philosophical demonstration, are only underlying themes that are not pretentiously elaborated but rather suggested and in the most subtle and touching way.

Through out the blurry/not blurry memory shots of Kurt’s past, Florian Heckel puts us in his shoes, forcing us to see through his eyes and confronting ourselves with what we’re willing to see… or rather not, preferring blinding ourselves.

As in Cold War, we observe the same idea of control and authority upon art, over freedom and experiment. This idea is represented in both films by a figure of domination and authority: in Cold War, it’s the larger-than-life and omnipresent photograph of Staline; in Never Look Away, it’s the character of Professor Carl Seeband, Ellie’s father. Both of the films portray artists looking for some kind of purity in art, far from the rigidity and ‘in the box’ canons of a regime which takes control over its citizens and their tools of self-expression.Talking about purity, it’s interesting to look at the character of Kurt’s aunt, Elizabeth.

She represents the duality that’s gonna haunt Kurt’s life and work, thinking of creations for the Fürher (creations in all senses, when she evokes giving him a baby…) but also disagreeing with the established notions of good art. Her madness seems to make her perceive the poetry of the world she’s evolving in and, maybe, attaining some kind of purity in that way cause she’s thinking “out-of-the-box” – extremely for sure, but nevertheless, not influenced by preconceived ideas or by any moral standards.

After such a beginning and a look through Kurt’s childhood, one understands and sympathizes even more with Kurt and his struggle to reach the emergence of his affirmed self through art, first occulted by the pleasure of newness but quickly returning to the essence of what he is and where he comes from, thanks to an harsh, though enlightening, comment on his first works: “This is not you”, his teacher simply puts it.

It then takes Kurt a lot of courage but also trust in his unconscious to go back to the unspoken traumas of his past and finally reconnect to his inner child, who’s gonna deliver the truth through his paintings. And that’s also when the filming of the colors and the come-and-go of the brush on the canvases get more intimate, with beautiful close-ups and the impression of being carried away by the brush and Kurt’s imagination, just as he is.

All of that accompanied during the whole feature with music by the prolific and always remarkable Max Richter, who, again, gifts us with a melancholic and dreamy score thatenhances the experience. Combined with the camera used as the painter’s brush, it offers a final painting of true beauty, amidst the carnage of horror.

VERDICT?

GO AND GET FRAMED BY THIS BEAUTY!

#never look away#film#review#florian henckel von donnersmarck#cinema#the lives of others#max richter#love theme#war#art#gerhard richter#director#score#paula beer#tom schilling#academy award winner#masterpiece

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

What the Candyman Ending Means for a Sequel and His Immortal Legend

https://ift.tt/3gNNBgZ

This article contains Candyman spoilers.

It is an exquisite final image. Swarmed in a symphony of bees and standing triumphant over his latest victim—a police officer sprawled out in an alleyway’s gutter—Candyman looks joyful. He’s the monster who’s haunted the ruins of what was once Cabrini-Green for more than a hundred years, and the legend who frightened children and caused lovers to cling closer in their rapture, and now he’s at last returned to his flock. Only this time Candyman is saving the woman who summoned him instead of destroying her.

As Teyonah Parris’ Brianna Cartwright looks on, her salvation is a wondrous thing—both a ghost and a living ghost story—who has killed something far scarier than his legend. The truth of this is told by the bodies of corrupt police officers strewn around the scene. Moments earlier, those same cops in cold blood killed Brianna’s boyfriend, artist Anthony McCoy (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II), after assuming from a glance this Black man was the criminal they sought. In doing so, they permanently secured Anthony’s place in the Candyman mythos, crafting his sad story onto the enduring larger one written in blood by the Black bodies that’ve been destroyed on these lands for more than a century. So when Brianna summons Anthony back by saying “Candyman” five times, it is not Abdul-Mateen’s face we see. Rather a de-aged Tony Todd stands defiant again. The everlasting saga of the Candyman walks again among us.

It’s a loaded image that speaks greatly about the movie we’ve just watched… and the inevitable Candyman sequel we are about to get.

Because rest assured, there will be a Candyman 2 (or Candyman 5, if we’re getting technical). After all, this new movie just grossed an impressive $22.4 million in its opening weekend, which nearly matches the film’s entire $25 million budget. There is thus little doubt about whether Universal Pictures will want to continue the story. But of course the entire point of Candyman is that this is a story which never ends, not in the last vestiges of Cabrini-Green, and not in America. All of which makes the prospects of another movie fascinating…

A New Candyman for a New Type of Victim

If Bernard Rose’s original Candyman (1992) was a Gothic Romance of the nihilistic order—complete with the loaded imagery of a Black man haunting the dreams of a white woman—then Candyman circa 2021 is functionally something else. At its barest bones, it’s a werewolf movie, and a Jekyll and Hyde reimagining. Abdul-Mateen’s Anthony is a good man who says his prayers by night (or at least kisses Brianna before bed), but when the moon rises, and “Candyman” is whispered five times before a mirror, something supernatural and beyond his control takes hold.

If Virginia Madsen’s Helen was bedeviled by the assumption that she was responsible for Candyman’s murders in the original movie, Anthony is damned by the much worse realization that he is becoming Candyman. Of course the idea of what that means is something far more tangible than urban legends about mirrors and spirits.

As eventually explained by Colman Domingo’s William Burke, Candyman is more than just a ghost story; it’s the tale of systemic oppression of Black men since time immemorial. The original Candyman might’ve been Daniel Robitaille, a Black artist in 1890s Chicago who dared to fall in love with and impregnate a white woman—which led to his body being mutilated by a lynch mob—but as Burke explains in Candyman, all those innocent Black men who’ve been brutally murdered by white authority over the decades were real men who existed beyond the confines of campfire stories. They lived, they loved, and they died horrible, gruesome deaths. In the case of Burke’s own childhood boogeyman, Sherman Fields (Michael Hargrove), that came in the form of a simple neighborhood man who liked giving candy to children, and the cops naturally assumed he was responsible for the recent death of a white child before shooting him.

These real stories are twisted into an urban legend that shrouds the ugliness under a veneer of Gothic horror and romance. That is the true tragedy of Candyman. Hence the horror of Anthony becoming just another Black face to fear for those with the power, another boogeyman whom cops will eventually shoot on sight simply for being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Society is literally forcing and contorting these Black men’s bodies to fit a prejudiced assumption.

That is why, according to Burke, and by extension Nia DaCosta and Jordan Peele’s script, the Candyman story lives on with a mystical sort of power. Throughout the movie, Anthony McCoy is haunted by Candyman’s reflection in the mirror, even though we rarely get a good look at him. The role of a monster is being thrust upon him.

Yet who does the revived Candyman kill? Whereas in the original film he considered the impoverished residents of Cabrini-Green’s projects his “children” and “flock,” whom he occasionally would select victims from to keep his legend alive, the Candyman of 2021 has few Black faces to cull from. Gentrification has literally pushed them out, and the high-rises Rose and Tony Todd shot the original Candyman in have been torn down and erased.

So Candyman’s victims in the 21st century are largely the white faces who’ve displaced the original flock. Tellingly, the first victim in the new movie is Clive Privler (Brian King), a white man who curates Black art and generates wealth for himself by exploiting local trauma. What sets Anthony on his fateful descent is being told by Clive that art about Black struggle in the South Side is played out; dig into that Candyman nonsense in Cabrini-Green instead. So it is that Clive and his girlfriend, who pay no credence to the rituals and awe Cabrini’s previous residents had for Candyman, are among the first to summon the ghost—tasting his glorious treats.

The next victim is a white art critic who has little interest in Anthony’s art when she first sees it. Rather she has the chutzpah to tell a Black man about why he is guilty of gentrification and dismiss his art as blunt and common. Yet when she sees commercial appeal in the story following Clive’s gruesome murder—suspecting there is now a Black story to benefit from telling herself—she circles back to Anthony’s Candyman art and seals her fate.

In the original Candyman, Tony Todd purrs, “They will say that I have shed innocent blood. What’s blood for, if not for shedding?” In 2021, no one who dies by Candyman’s hook is particularly innocent. Even the teenagers who summon him to a high school bathroom have benefitted from a culture that relies on complicity. They were of course too young to know they’re part of that system… but then so was Anthony when he was taken as a baby by the Candyman 30 years ago, and doomed to the same cyclical violence perpetrated against Black men each generation. Innocence and ignorance save none in this story we’ve built for ourselves.

Which brings us back to that ending with Anthony dying so as to fully resurrect Candyman’s legend. As Burke plainly spells out, a ghost story for Black communities could be laughed off by the elite and bourgeois white classes in the past. Now Candyman can live forever if the blood he is spilling belongs to white culture—beginning with the cops summoned to the scene.

Where Does This Leave the Candyman Sequel?

The last line of the new Candyman is Tony Todd’s visage commanding Brianna to “tell everyone.” He’s back. The full impact of that is revealed during Candyman’s end credits. Initially, the film fades out on DaCosta’s use of haunting paper shadow puppets, which were used throughout the movie to recreate old myths about Candyman: Helen Lyle’s fate and Daniel Robitaille’s courtship of a wealthy white daughter and a father’s terrible vengeance. Yet if you stay long enough in the theater, a new shadow play is enacted, one in which an artist loses his mind, and his paint brush is replaced by a hook.

This puppet play ends like the movie: Candyman has risen and five treacherous police officers are left in pieces. The implication is, clearly, that Brianna has obeyed Candyman’s edict and spread the good word.

Yet if this is the new legend, where can that lead a potential follow-up? Is Candyman essentially a superhero movie? The story of a ghost who punishes those white faces that dare dismiss the Black culture they’ve supplanted and profited from?

Possibly, although I think that is too reductive and simplistic for DaCosta and Peele, as well as somewhat of a betrayal of Candyman’s appeal if it stops there. Like the beautifully haunting melody of Phillip Glass’ original Candyman musical theme, there is an intoxicating allure found in the sorrow and tragedy wrought by this character. If Candyman’s story is transitioning from one about meta-textual mythmaking to one about cultural revenge against repression, then it must still remain a revenger’s tragedy.

Read more

Movies

What to Expect from the Candyman Reimagining

By David Crow

Movies

Candyman Origins Explored in Haunting Video from Nia DaCosta

By David Crow

As Burke said in the new movie, Candyman is a tale folks use to comprehend and organize their thoughts around long systemic violence against Black people in this community, beginning with Daniel and carried on through Anthony in this particular case. That story is, sadly, unending in American life, but it can be told in a new way by a Candyman sequel.

If the 2021 movie is, in its barebones, a werewolf narrative with a central victim coming to terms with his transformation, then a follow-up could pivot to returning to the heightened operatic quality of the original Gothic film. For instance, as brutal and merciless as DaCosta’s on screen violence is in the new picture, I would argue there is nothing as unnerving or unforgettable as Tony Todd’s big entrance in 1992.

Halfway through the original movie, after being told repeatedly there is no such thing as Candyman, Helen and the audience eventually turn the corner in a parking deck and there he is: formally draped in a fashionable coat and standing at a posture that is simultaneously inviting and foreboding. He’s no slasher killer who will float across the floor to get you. He is an almost godlike presence who has the infinite patience of a spirit that knows time is on his side, and his reach is inescapable. The more Helen attempts to resist, the more she and the audience are helplessly drawn in by the irrepressible power derived from a legend.

A sequel to Candyman (2021) could lean into those abilities and allow Abdul-Mateen to fully inhabit the role in the way Todd did for a previous generation. Abdul-Mateen certainly has the talent to use a soft-spoken voice to dominate the screen. However, the trick could be to use it to a different end.

With Candyman returned as a spirit of revenge against a white society that has finally grown forgetful enough to move into his domain—the ruins of Cabrini-Green—he can now be a presence that at last victimizes those who oppressed Daniel Robitaille, Anthony McCoy, and all the others. By virtue of that long sad history, the melancholic fatalism of the character can never feel empowering… but it can be righteous.

Anthony becoming the face of Candyman for this new era makes sense as the story of the artist’s madness and demise is now forever coupled to the legend. Just as Anthony saw Sherman Fields in the mirror because William Burke told him the Candyman story of his youth, so will new generations see Anthony McCoy when they dare summon Candyman.

And if Anthony is the face of Candyman going forward, he can continue to haunt Brianna’s dreams while drawing her into providing him more victims—sweets for the sweet—which would recontextualize the fatalist romance from the original movie. Theirs could be the ultimate art piece in the new Candyman’s mind, one where he cuts a bloody canvas so vast that even Lakeshore Drive cannot look away. How delicious.

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ playerId: "106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530", }).render("0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796"); });

The post What the Candyman Ending Means for a Sequel and His Immortal Legend appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/38nbpDM

0 notes

Text

“Two Weeks”

Pairing: Steve Rogers x Reader

Summary: A narrative that explores how Steve copes after your tragic death.

notes: implied character death (reader), a failed attempt at writing sad things

A/N: thank you to @buckyywiththegoodhair for beta-reading this mess. i adore you, and god rest this old bitch’s soul.

One week has passed since you left New York for a month-long guest curatorship in Germany. Before leaving, you kissed Steve goodbye and promised to return in one piece.

One week has passed since HYDRA agents infiltrated the museum. They put the entire museum on lockdown, claiming it had World War II documents that were essential to the HYDRA agenda. Even the Avengers wouldn't stop their mission to obtain these documents, they declared.

One week has passed since a certain HYDRA agent recognized your face from a tabloid, the headline screaming “Captain America Finally Finds Love!” He also deduced your title as one of the United States' leading experts on Nazi Germany. It was the perfect coincidence.

One week has passed since HYDRA attempted to use you as a bargaining tool. "Give up the documents, and we'll let you go back to your precious boyfriend," they said. Much to their surprise, behind your simple dress and ballet flats was a woman not afraid to kick men in the balls, both figuratively and literally. You proceeded to do the latter.

One week has passed since the Avengers compromised the guards and rescued most of the hostages at the museum. Only one remained, but when it became clear that they're wouldn’t gain access to any of the documents, HYDRA decided to inflict pain in the best way they knew how - by taking away the remaining innocent life.

One week has passed since your tragic death.

One week has passed since Steve Rogers buried the love of his life.

Everyone is shocked at how well Steve is dealing with the tragedy. Though he's a bit quieter, he seems to be his usual, collected self. He insists that he's fine and carries on with his daily routine. It's odd, especially because the super soldier is well-known for wearing his heart on his sleeve. Even Bucky is confused by his best friend's calm demeanor.

"Should we force it out of him? Blast some Metallica and have him exert his true feelings onto a punching bag? Tony, you installed the new speakers in the gym, right?"

"I did, but that’s a bad idea. Cap's already ruined about ten punching bags, and I haven't upgraded the punching bag hook yet."

"But what he really is fine? What if he’s really okay?"

"The man just lost his girlfriend, the woman he was and probably still is infatuatedly in love with. There's no way he's fine. He's repressing his emotions," Sam theorizes.

Natasha tilts her wine glass in Sam's direction. "I agree. This whole," she pauses and gestures as she tries to come up with an accurate term, "charade is out of character for him."

Clint clears his throat. "No one really knows what's on Cap's mind so -"

"Actually -"

Firmly shaking her head, Wanda holds up her finger and silences Tony. "No, I said I'm not digging into people's minds unless it's for the greater good," the Sokovian says, a slight ice lacing her gentle tone. She proudly smiles while Tony holds up his hands in both understanding and mock surrender.

"Let's just be there for him. Tony, I know this is an impossible request, but please refrain from being an asshole," Clint warns.

Over the course of the week, the Avengers do exactly that. Even though both of them are clueless about art, Sam and Bucky buy year-long passes and offer to take him to the exhibits. Wanda fills the pantry with the tasteless, healthy snacks that no one but Steve likes while Vision has the blonde's coffee ready every morning. Bruce leaves vitamin supplements specially created for Steve's serum-enhanced body at his door. Nat and Clint offer to accompany Steve on his ridiculously early runs - something the two assassins refused to do in the past. Even Tony is on his best behavior, biting down on the witty remarks that have potential to trigger.

But Steve continues to insist that he's fine. He claps a hand on the respective Avenger's shoulder and gives a gentle squeeze before returning to whatever he was doing.

Friday rolls by. Two weeks have passed since your death.

"Cap, um... I hate to be the bearer of bad news..."

Sam uncomfortably shifts his weight from one foot to the other, bearing the posture of someone who has to deactivate a ticking bomb. Steve looks up from the mission reports. "It's fine, Sam. Just say it," he encourages.

"Erm, (Y/N)'s former landlord called. She needs us to clean and sort out the apartment."

The light in Steve's eyes slightly dims as he takes in this information. This is the first time anyone's said your name out loud since the funeral, and it sounds a little foreign coming from Sam's mouth. But something pangs in Steve's heart, and all of a sudden his chest starts to hurt. He forces himself to smile and says, "I'll head over there later tonight. Thanks, Sam."

"Hey," Sam murmurs, waiting until Steve looks up from the mission report again. "If you want, a few of us could go with you and help."

Hesitation lines the super soldier's eyes, but he slowly nods. "Okay. I'd appreciate that."

The chest pains grow in intensity when Steve steps into the small one-bedroom apartment, and a shiver runs up his spine as he takes in the place you called a second home. Memories float around everywhere, haunting almost every piece furniture or decor.

The kitchen island rings of lazy Sunday mornings. You always hopped into the island while Steve made breakfast. Standing in between your legs, your arms winding around his neck, he could never resist planting sweet kisses all over your face. The pancake batter would be long forgotten as the kisses turned hot and frantic.

The baby succulents lined up on the window frame speaks of trips to the farmer's markets. Knowing you were notorious for being an unintentional plant killer, Steve made a point of gifting you with plants you couldn't kill.

The couch holds memories of embraces. Whether they were sinfully infused with desire or meant to seek comfort, Steve loved to hug you, claiming that your hugs had the power to placate him and bring peace like nothing else could.

Bucky taps Steve's shoulder, bringing the blonde back to reality. For the second time today, Steve forces a smile onto his face. "I'm going to clean her room. Do you guys mind doing the living room and kitchen for now?"

"Go, we got this."

Your room is a treasure cove filled with knick knacks and books, but the first thing that comes into Steve's line of sight is your beloved vintage film camera. You had a knack for film photography, and he was your favorite subject.

Steve walks over to your desk, two photos neatly placed on top of a thick textbook capturing his attention. He carefully holds up the photos by the edges - a habit you've instilled in him.

The first photo was taken the day the city flooded the streets to celebrate the victorious return of the Avengers. Still clad in his stealth suit, Steve is rushing towards the viewfinder, happiness etched on his face. A number of people are reaching out to congratulate him, but Steve only has eyes for the camera. Well, the person behind the camera, that is.

Steve flips the photo over, a soft snort of laughter huffing out of his nose. In addition to the date, you'd written out the second stanza of Walt Whitman's "O Captain! My Captain."

O Captain! My Captain! rise up and hear the bells;

Rise up -for you the flag is flung- for you the bugle trills;

For you bouquets and ribbon'd wreaths -for you the shores a-crowding;

The second photo is less hectic. It's a candid of him leaning against the doorway with his arms crossed against his chest. He's looking off into space with remnants of laughter on his lips.

The blonde flips the second photo over to read what you've written as the description. It's one word, but it's powerful enough to make his heart crumble.

Home.

"This wasn't too bad... I guess it helped that she was a neat minimalist."

"True. Natasha, everything good with Stark?"

"Mmhmm. He's arranged for people to pick up the boxes and donate them to schools, women's shelters, the Salvation Army, the museum, library... A lot of people will benefit from her things."

"Classic (Y/N). Always helping others."

Scanning the rest of the now-empty living room and kitchen, Natasha lets out a satisfied nod. "Okay, we should check in on Steve and see how he's doing with the bedroom."

Bucky pushes himself off the ground and tosses Sam the roll of duct tape he was using. "I'll do it. Finish this box up for me?"

The brunette wanders down the short hallway of the apartment and gently knocks on the closed door, but Steve doesn't answer. Bucky pushes open the door and he opens his mouth to speak, but the view in front of him immediately halts his steps and words.

Steve sits on your bed, silently sobbing and clutching your favorite sweater to his chest. His chest heaves up and down, his silent sobs turning from violently loud. Inhuman wails come from deep within his soul. The dam inside him has finally burst open, and every emotion he swiftly blockaded in the back of his heart spills out with fury. Each gasp claws through his throat and sends him deeper into a storm of loss and grief.

Two weeks have passed since your death, and Steve Rogers is finally unleashing his pent-up emotions.

His heart and head kaleidoscopes with memories both good and bad. The time he returned his old Cap uniform, only to be stunned into awe while you berated him for stealing from the museum. Your smile that sang of sunshine and spice and easily became his favorite thing about the twenty-first century. How his blood ran cold at the sound of a gunshot, only growing colder when finding your lifeless body a few minutes later. The heavens mourning through rain on the day he put you to rest.

It hits him that you wouldn’t be able to fulfill your promise of returning to him. No more kisses on the kitchen island, no more trips to the farmer's market, no more warm cuddles on the couch. All remnants of you are being packed away in boxes and given to other people. All that will remain of you are intangible memories and the love he had for you in his heart.

Two weeks have passed since your death, and all Steve can do is cry his heart out for the one who was unjustly and tragically whisked away from him.

#steve rogers fanfic#steve rogers x reader#steve rogers x you#steve rogers fanfiction#steve x reader#steve x you#steve rogers x oc#steve rogers one shot#steve rogers oneshot#steve rogers imagine#captain america x reader#captain america imagine#captain america x you#captain america fanfic#captain america x oc#ourpeachskies#ourpeachskies writes

817 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fucked Up ME

Hello everyone. For those of you who still doesn’t know me, I am Joshua Brendon, author of this mentally fucked up blog. To my avid readers, Lamelle & MJ: welcome back! To the people who don’t read what I post but sees this: hello and welcome!

In this new piece of art (or piece of shit) that I’m going to write and publish will discuss how and why I became mentally fucked up. I know my posts are usually the “angsty-lovey-dovey” shit dedicated to either my two-timing ex, the girl I once knew and broke her heart, rum cola, and the most prominent today, M. This is much more personal than the rest and even more personal than my supposed suicide note and lame quotes I post about my inner feelings. Today, I’m gonna spill the tea about me.

Some of you may already know this but I’m gonna say it anyway (it as an essential part of this narrative): I am part of a broken family; my parents are separated. It happened about 10 years ago when I was young and innocent. Still, up to this day, what happened 10 years ago haunts me. It’s a narrative that I didn’t wish to be a part of yet I was placed in the said narrative. What happened 10 years ago became the cause of my fucked up entirety.

A little back story, my mother and father married young. They were nineteen at that time. My father got my mother pregnant at a very young age resulting to the marriage. They only knew each other for a few months. Back then, they claim to love each other. They even eloped and hid me (while I was still in the womb) from their parents. Originally, my mother did not want to get married but my father did. The plan was for my mother to fly the US with me and would leave my father here in Manila. That didn’t happen.

One forced marriage and nine months later, I was born. Poor innocent me, born into this harsh and cruel world; not knowing the shit-hole of a life I would be plunge into. Four years in the marriage, my mother gave birth to my sister. In those four years, nothing was perfect (looking back nothing was perfect, and my childhood memories that I thought were pure weren’t). Two families who never did like each other were forced to communicate and interact with one another because of the one little me trying to pull them together.

Years later, nothing’s change. I have grown up and I was this happy-go-lucky little boy. You may see me now as a happy-go-lucky person but that is just a facade. Underneath this seemingly perfect exterior is a fucked up person waiting for death to arrive.

Question! How do you break a family? Answer: take an early wed couple, add some financial issues multiplied by personal family issues, then add infidelity on both sides. Presto! You now have a broken family. Now, how do you make a mentally fucked up kid with deep issues and psychological and emotional problems? Use the same equation.

A couple who got married early and doesn’t really know each other well has the most probability of separating due to infidelity. How did my parents became adulterers you asked? Well, they were on a break because of their financial issues. They lived separately for a short period of time. During that short period of time, my father had a “fling” and to make matters worse, my mother “revenge-cheated” on my father. Loos like the bitch apple doesn’t fall far from the bitch tree because look at me now. A series of flings and lack of commitment. Thanks mom and dad!

Don’t get me wrong. I love my parents with all my heart and soul has to offer but sometimes they’re just fucking me up unintentionally. Do you know the snowball effect? If you let a snow ball roll down a slope it gets bigger. My life is excatly like that. The snowball being the fornication and sin my parents committed when they were young. They never thought that it would turn out to be a big problem, it was never planned anyway.

Who knew that a simple premarital sex and early pregnancy would result to a damaged person which is me. Well, I should have seen it coming. My mother is a possessive and controlling woman. My father is a passive-aggressive man. Both are neurotic and controlling in many many ways. Their offspring? A psychotic child. Like I said, the bitch apple doesn’t fall far from the bitch tree.

You have probably heard of the cliche sayings that child with separated parents say so I would spare the agony of reading them once again. Although it is cliche, it is still true as fuck. Growing up is really really hard. I rebel. I lost my innocence. I lost my hope. I lost my faith. I lost my spirit. I died. Thank God I was reborn.