#bajazid elmaz doda

Text

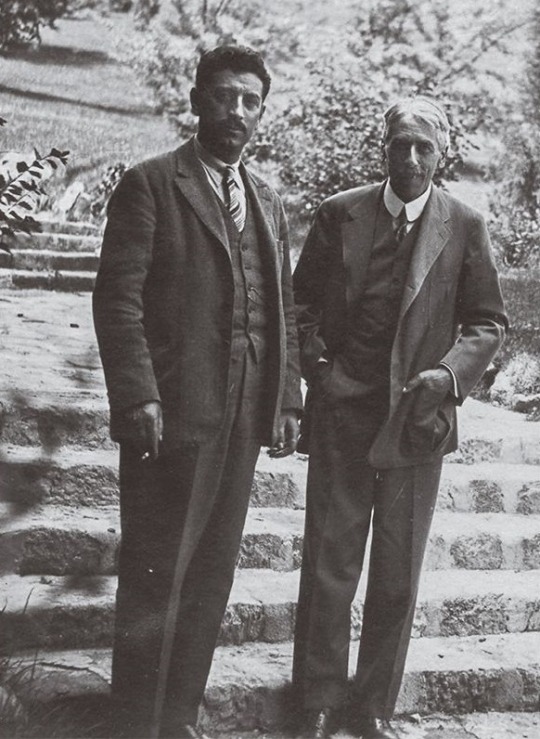

Bajazid Elmaz Doda (left) and Franz Nopcsa (right).

Bajazid and Franz met in Bucharest in 1906. Bajazid was a young man who had left his Albanian village looking for work. Franz was an aristocratic palaeontologist and ethnographer with an interest in Albania. The two men became lovers, and spent the next 27 years together, travelling Albania and then settling in Austria. Bajazid wrote his own ethnographic work, recording the culture of Upper Reka Valley where he had grown up, and his fears for its destruction in WWI. His village, Stirovica, was razed by the Bulgarian army in 1916.

Sadly, suffering from depression, on 25 April 1933, Franz shot Bajazid, and then himself, killing both men.

Learn more

#bajazid elmaz doda#franz nopcsa#queer history#suicide cw#murder cw#lgbt history#lgbt#queer#gay history#albania

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

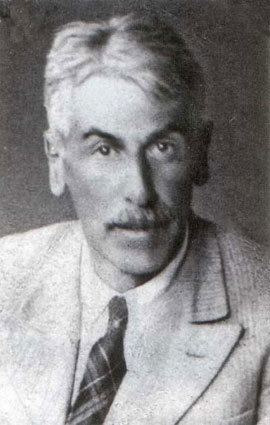

Baron Franz Nopsca:

Linguist, WW1 spy, Austro-Hungarian Nobleman, Seducer of wealthy women, Self-taught Paleontologist, gun runner, guerilla fighter, motorcycle enthusiast, one time claimant to the Albanian throne, first in history to hijack a plane and well known arrogant trust fund baby, I present the Shepard Prince of Transylvania, namer of turtles and lover of men, The Baron Franz Nopcsa von Felső-Szilvás.

Born in Deva Transylvania (modern Romania) to an aristocratic family of Romanian and Hungarian origin.

Franz was the son of Baron Elek Nopsca, a member of parliament in the Hungarian government.

Franz developed a love of paleontology in his teens after his sister discovered bones on the family estate. It was in this field where he would meet the love of his life, Bajazid Elmaz Doda.

The two men would travel to Doda's homeland of Alabania to study fossils and perhaps take part in local dissent against the Ottoman overlords of the region.

After being rescued from a local warlord by his boyfriend's father, Nopsca turned to espionage, posing as a Shepard to spy during both the Balkan Wars and the First World War.

In 1919, Nopsca became the first person in history to hijack a plane when he fled a communist uprising in Hungary.

This story does not have a happy ending however, despite all its swashbuckling adventures and thrills.

Pressed financially and depossessed of his holdings in Transylvania, Nopsca turned to suicide in 1933 after drugging and killing Doda with a handgun.

#ww1#edwardian#first world war#1910s#wwi#edwardian era#history#lgbt history#queer history#austro hungarian empire#austria hungary#albania#old post remaster

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

can u believe that the first man who ever hijacked an aircraft was a gay hungarian paleontologist ??? he was trying to escape from the hungarian soviet republic in 1919

#he also unearthed a dinosaur which he named magyarosaurus!!!#he did a lot of other cool stuff too! well i mean he kinda shot himself and his albanian lover bc he became depressed...... but . yknow#he was very cool in other things#nopcsa ferenc#franz nopcsa#bajazid elmaz doda#hungarian#zsófi rambles

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The love story of Baron Franz Nopcsa and Bajazid Elmaz Doda

Bajazid Elmaz Doda was born ca. 1888 in the mountain village of Shtirovica in Upper Reka (Reka e Epërme / Gorna Reka) region of western Macedonia. Like many young men from Reka, he left the mountains and emigrated to Romania in search of work. In Bucharest on 20 November 1906, he met the noted Hungarian scholar, Baron Franz Nopcsa (1877-1933), who hired the eighteen-year-old lad as his servant.

This relationship evolved into a love affair and a long-term domestic partnership. In his memoirs, published in German in 2001 under the title Reisen in den Balkan (Travels in the Balkans), Nopcsa describes his first meeting with his young lover, disguised as his private secretary:

"On 20 November 1906, in Bucharest, I met Bajazid Doda. Since that time, Bajazid has been with me and, since the death of Louis Draškovic, he has been the only person who has truly loved me and in whom I had full confidence, never doubting for a moment that he would misuse my trust. He of course had his failing, but I was more than willing to put up with them. The Serbs murdered Bajazid's father and brother in 1913 out of hatred for everything Austro- Hungarian, and in particular out of hatred for me, because I was active in Albania."

From Bucharest, Nopcsa and his young servant travelled to the Nopcsa family estate in Szacsal (Sacel) near Hatzeg in Transylvania and, several months later, on to London where Bajazid caught influenza. In mid November 1907, the two journeyed to Shkodra where Nopcsa had a house in 1907-1910 and from October 1913 onwards. They carried on over the mountains of Mirdita to Kalis where they were taken hostage by the notorious robber Mustafa Lita. After their release in Prizren, they travelled to Skopje and no doubt on to the upper Reka valley, as originally planned. They then returned to Shkodra in order to explore the territory of the Hoti and Gruda tribes.

In the years before and during the Balkan Wars, Nopcsa and his temperamental Albanian secretary travelled throughout northern Albanian, Kosova and Macedonia. In the autumn of 1913, Nopcsa reported:

"Once, when Nikol Gega and Bajazid, in a fit of sudden fury, seized their revolvers and were only prevented from killing one another by the intervention of Gjok Prenga and Mehmet Zeneli, I was able to arbitrate to the detriment of neither, and make peace between them so that they were eventually reconciled. Many Europeans were amazed at how I was able to keep all these very different characters together, who like all Albanians incline to envy and jealousy... From Shkodra, once I had put my household affairs in order, I set off for the mountains. My plan was firstly to climb the southern slopes of the northern Albanian Alps and then the area just west of the Prokletije, the Accursed Mountains. Due to malaria, however, I was obliged to abandon this part of my plan and limited myself to the upland parts of Kastrati which were easier to scale. Bajazid scaled Mount Veleçik, the Kunora e Keneshdolit and some other mountains in my place and took the photographs needed for the topographical maps of the northern Albanian Alps."

In the war years, 1915-1916, Nopcsa took his secretary with him while he was serving with Austro-Hungarian troops in Kosova. After the First World War, Bajazid Elmaz Doda and Franz Nopcsa lived mostly in Vienna, where the Hungarian scholar published several works of note, and enjoyed fame as a specialist not only in Albanian studies, but also in palaeontology and geology.

On 25 April 1933, Baron Nopcsa, who had long been suffering from depression, committed suicide by shooting himself in the mouth. Just before his death, he shot his faithful secretary and partner, Bajazid Doda. In a suicide note to the police, Nopcsa confirmed:

"The reason for my suicide is my nervous system which is at its end. The fact that I killed my long-term friend and secretary, Mr Bajazid Elmaz Doda, in his sleep, without him having an inkling as to what was going in, was because I did not want to leave him behind sick, in misery and in poverty because since he could have suffered too much. I wish to be cremated."

Bajazid Elmaz Doda is the author of the book Albanisches Bauerleben im oberen Rekatal bei Dibra (Makedonien), [Albanian Peasant Life in the Upper Reka Valley near Dibra (Macedonia)], that he completed as a typescript in Vienna in April 1914 and that was finally published in Vienna in 2007. The original typescript and the 2007 edition are accompanied by photographs taken, according to the author, by Doda himself. They are probably from the year 1907. The pictures are primarily of the author's native village of Shtirovica and surroundings, though there are also two photos of Skopje. This photo material is of particular historical value because the village in question has disappeared - nothing remained but a grassy meadow and a few piles of stones. Its native Albanian inhabitants were expelled from the Reka valley by Bulgarian troops in about 1916.

The book "Albanian Peasant Life in the Upper Reka Valley near Dibra (Macedonia)" contains a wide range of material and information on various fields and should prove useful for many subjects of research. It would also seem to be the first ethnological study ever written in German by an Albanian. Doda explains his objectives in a preface:

“During the Turkish period, my homeland, the Upper Reka Valley, was isolated from the outside world due to a short- sighted policy aimed at propping up a barbaric regime. As a result of recent events, it has come under Serb rule, and it is now to be feared that the Muslim element in Upper Reka, in view of its traditional isolation, will vanish and leave no trace. The purpose of this book describing the life of the Muslims in the Upper Reka Valley is to counter this trend, to help my fellow Muslim villagers preserve their identity, and to create a lasting monument among the publications dealing with Albania. What Spiridion Gopcevic has to say about Reka in his notorious book on Macedonia (Makedonien und Alt-Serbien, 1889) is all tendentious lies, something which has been noted by other travellers before me. I did not intend to write an academic treatise on ethnography or some serious dissertation, but simply to describe this part of the world as I experienced it myself on a daily basis. When those who exterminated the Albanians in the region of Nish [Niš] have also wiped out my people, the simplest accurate description of their daily life will suffice to serve both as a permanent monument to their one-time existence and as an indictment to those who annihilated them.”

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today I read about Franz Nopcsa von Felső-Szilvás (aka Baron Nopcsa von Felső-Szilvás), a complex man who made interesting contributions to palaeontology, and also named a species of toad Kallokibotion bajazidi, which literally means 'beautiful box of Bajazid'. The reason for this name was that the shell reminded him of the arse of his effectively-husband, Bajazid Elmaz Doda.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Of all the people who have ever studied dinosaurs, collected dinosaur bones, or even thought about dinosaurs in any serious way, there’s never been anybody quite like Franz Nopcsa von Felső-Szilvás.

Baron Franz Nopcsa von Felső-Szilvás, I should say, because this man was literally an aristocrat who dug up dinosaur bones. He seems like the invention of a mad novelist, a character so outlandish, so ridiculous, that he must be a trick of fiction. But he was very real – a flamboyant dandy and a tragic genuis, whose exploits hunting dinosaurs in Transylvania were brief respites from the insanity of the rest of his life. Dracula, in all seriousness, has nothing on the Dinosaur Baron.

Nopcsa was born in 1877 to a noble family in the gentle hills of Transylvania, in what is now Romania but was then on the fringes of the decaying Austro-Hungarian Empire. He spoke several languages at home, and they instilled within him an urge to wander. He also had urges of another kind, and when he was in his twenties, he became the lover of a Transylvanian count, an older man who regaled him with tales of a hidden kingdom of mountains to the south, where tribesmen wore dapper costumes, brandished long swords, and spoke in an indecipherable tongue. The local mountain men called their homeland Shqipёri. We know it today as Albania, but then it was a backwater on the southern edge of Europe, occupied for centuries by another great empire, the Ottoman.

The baron decided to check it out for himself. He headed south, through the borderlands that separated two empires, and when he arrived in Albania, he was welcomed with a gunshot, which sliced through his hat and narrowly missed his skull. Undeterred, he proceeded to cross much of the country on foot. He picked up the language, grew his hair long, started dressing like the natives, and earned the respect of the insular tribes nestled among the mountain peaks. But the tribesmen might not have been so welcoming if they’d known the truth: Nopcsa was a spy. He was being paid by the Austro-Hungarian government to provide intelligence on their Ottoman neighbors, a mission that became even more critical – and dangerous – as the empires collapsed and the map of Europe was redrawn in the hellfires of World War I.

That’s not to say that the baron was merely a mercenary. He was enamored of Albania – obsessed, really. He became one of Europe’s leading experts on Albanian culture and came to truly love its people – one in particular. Nopcsa fell for a young man from a sheepherding village in the high mountains. This man – Bajazid Elmaz Doda – nominally became Nopcsa’s secretary, but he was so much more, although it wasn’t spoken about so openly in those less accepting times. The two lovers would remain together for nearly three decades, enduring the leers of their peers, surviving the disintegration of their respective empires, traveling Europe by motorcycle (Nopcsa on the bike, Doda in the sidecar). Doda was by Nopcsa’s side when, in the chaos before the Great War, the baron plotted an insurgency of mountain men against the Turks – even smuggling in firearms to build an arsenal – and then later tried to install himself as king of Albania. Both schemes failed, so Nopcsa turned to other pursuits.

As it turned out, that would be dinosaurs.

In fact, Nopcsa became interested in dinosaurs before he knew anything of Albania, before he met Doda. When he was eighteen, his sister picked up a mangled skull on the family estate. The bones had turned to stone, and it didn’t look like any animal the young baron had ever seen scurrying or soaring across his stately grounds. He brought it with him when he started university in Vienna later that year, and upon showing it to one of his geology instructors, he was told to go find more. And so he did, obsessively exploring the fields, hills, and riverbeds of the land he would later inherit, on foot and horseback. Four years later, a blueblood in name but still just a student, he stood up in front of the learned men of the Austrian Academy of Sciences and announced what he had been up to and what he had found: a whole ecosystem of strange dinosaurs.

Nopcsa continued to collect Transylvanian dinosaurs for much of the rest of his life, taking breaks here and there when his services were needed in Albania. He studied them, too, and in doing so was one of the first people who made any attempts to grasp what dinosaurs were like as real animals, not simply bones to be classified. He had a genius when it came to interpreting fossils, and it didn’t take him very long to notice that something was odd about the bones he was finding on his estate. He could tell that they belonged to groups that were common in other parts of the world – a new species that he named Telmatosaurus was a duckbill, a long-necked critter called Magyarosaurus was a sauropod, and he also found the bones of armored dinosaurs. However, they were smaller than their mainland relatives, in some cases, astoundingly so; while its cousins were shaking the Earth with their thirty-ton frames in Brazil, Magyarosaurus was barely the size of a cow. At first Nopcsa thought the bones belonged to juveniles, but when he put them under microscope, he realized that they had the characteristic textures of adults. There was only one suitable explanation: the Transylvanian dinosaurs were miniatures.

This raised an obvious question: why were they so tiny? Nopcsa had an idea. Along with his expertise in espionage, linguistics, cultural anthropology, paleontology, motorbiking and general scheming, the baron was also a very good geologist. He mapped the rocks that held the dinosaur fossils and could tell that they had formed in rivers – thick sequences of sandstones and mudstones that were deposited either in the channels or off to the side when the rivers flooded. Underneath these rocks were other layers that came from the ocean – fine clays and shales bursting with microscopic plankton fossils. Tracing out the aerial extent of the river rocks and scrutinizing the contacts between the river and ocean layers, Nopcsa realized that his estate used t be part of an island, which emerged from the water some time during the latest Cretaceous. The mini-dinosaurs were living on a small bit of turf, probably around thirty thousand square miles (eighty thousand square kilometers) in area, about the size of Hispaniola.

Maybe, Nopcsa conjectured, the dinosaurs were small because of their island habitat. It stemmed from an idea that some biologist of the time were beginning to entertain, based on studies of modern species living on islands and the discovery of some strange small mammal fossils in the middle of the Mediterranean. This theory held that islands are akin to laboratories of evolution, where some of the normal rules that govern larger landmasses break down. Islands are remote, so it is always a little bit random as to which species can make their way out to them, being carried by the wind or rafting in on floating logs. There is less space on islands, so fewer resources, so some species may not be able to get so big. And, because islands are severed from the mainland, their plants and animals can evolve in splendid isolation, their DNA cut off from that of their continental cousins, each inbred island-living generation becoming more different, more peculiar over time. This, Nopcsa thought, is why his island-dwelling dinosaurs were so tiny, so funny looking.

Later research showed that Nopcsa was correct, and his dwarf dinosaurs are now regarded as a prime example of the „island effect” in action. Otherwise, fate wasn’t so kind to the baron. Austria-Hungary was on the losing side in the Great War, and Transylvania was handed over to one of he winners, Romania. Nopcsa lost his lands and his castle, and a senseless attempt to reclaim his estate ended with him getting pummeled by a gang of peasants and left for dead by the side of the road. With little money to support his lavish lifestyle, Nopcsa grudgingly accepted the directorship of the Hungarian Geological Institute in Budapest, but bureaucratic life was not for him, so he quit. He sold off his fossils and moved to Vienna with Doda, destitute and overcome with melancholy that we would probably today recognize as depression. Eventually he had enough. In April 1933, the erstwhile baron slipped some sedative into his lover’s tea. When Doda drifted off to sleep, Nopcsa put a bullet into him, then turned the gun on himself.

(Steve Brusatte: The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs)

#:-f#quote#franz nopcsa#von felső-szilvás#nopcse ferenc#steve brusatte#book#the rise and fall of dinosaurs

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

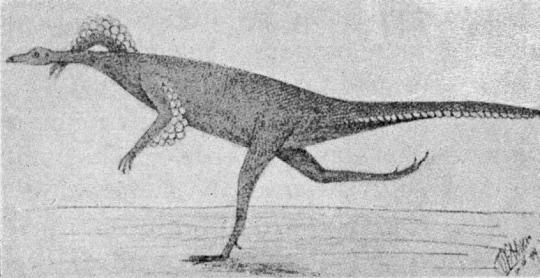

Two highlights from the sketches of gay Hungarian palaeontologist Franz Nopcsa (1877-1933). After his sister discovered dinosaur bones on the family estate when Franz was 17, he dedicated his life to their study, often working alongside his partner, Bajazid Elmaz Doda.

Sadly, in 1933, suffering from poor mental health, Franz shot himself and Bajazid, killing both men.

Learn more

Top image: 1907 illustration of the 'running proavis' theory of the development of flight in dinosaurs. Source

Bottom image: Sketch of Struthiosaurus, 1915. Source

#dinosaurs#queer history#franz nopcsa#bajazid elmas doda#gay history#suicide cw#murder cw#queer#lgbt#gay

51 notes

·

View notes