#bbc porthos

Text

Poor D'Artagnan

#wow they are so comfortable around each others!#they must be truly close friends#He literally got adopted by the throple#love my stupid boy#bbc the musketeers#the musketeers#athos#porthos#aramis#d'artagnan#bbc aramis#bbc porthos#bbc athos#bbc D'Artagnan#aramis/porthos/athos#Poly#bbc#regulus rambles

969 notes

·

View notes

Text

Porthos with long curls PORTHOS WITH LONG CURCLS

HE LOOKS SO FINE OMFG 😭😭😭😭

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recs list

I've been reading a few fics about our favourite absolute love of a musketeer Porthos :) Here are some I've loved a lot!

Wonders by Anonymous

Porthos gets a letter from Samara.

Either I've read this before or I read another one where he gets a letter from Samara that I loved, I believe the first but either way it's warm and fun and a lot of things in a small space. It's really lovely little rumination, and gives Porthos something good about his heritage as well as all the sadness in the show.

Holding On by Stk (Silasthekitty)

d'Artagnan getting to know the others in modern AU having many panic about Porthos's lovely grabby hands, so much fun! I love the relationship between them all and how d'Artagnan is seduced. It's also very funny.

Fever by Swashbuckling

Gen fic where Aramis (eventually) takes care of Porthos who is a bit ridiculous and of course very lovely. a little hurt/comfort slice of fluff. They're nicely characterful and I like the way they talk and things. Also they take good care of Porthos which is BEST.

Porthos Paper Doll by Irusu

Not a fic, just a glorious art, it is what it says on the tin - a paper doll design with some little outfits how great!

EDIT: add any gay Porthos centric fics if you have recs pleassseee your own too I want MORE.

#rec#fic rec#art rec#bbc the musketeers#BBC Porthos#Porthos Du Vallon#general du vallon#I just really love him a lot okay? It is kinda hard to weed out the fics that are wholly and fully about him. This is true of fave charac#a fave character but I am BUTT HURT about it happening to MY fave. Porthos should have ALL the fics FULLY about him

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

My take-away from the whole Titanicgate incident

#titanic#the titanic#oceangate#current events#the musketeers#bbc musketeers#aramis#santiago cabrera#porthos#howard charles#alexandre dumas#musketeers#the three musketeers#original post#not incorrect quotes#submarine#titan#the titan#james cameron#porthos du vallon#season 2 episode 5#the return#lol

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

D'Artagnan, Athos, Porthos, Aramis // Portraits // The Musketeers (2014)

#d'artagnan#athos#porthos#aramis#gorgeous men#luke pasqualino#tom burke#howard charles#santiago cabrera#bbc the musketeers#the musketeers#themusketeersedit#perioddramaedit#perioddramasource#perioddramacentral#weloveperioddrama#moonflowergifs#I mean we from TLK are almost pre-coded to love them#another squad of pretty boys

290 notes

·

View notes

Text

happy 10yr anniversary to the musketeers !! we all love some bts pics, so ask and you shall receive !!

#there were too many it was hard to choose just 10 !!#not many of the girlies unfortunately#the musketeers#bbc the musketeers#aramis#d'artagnan#athos#porthos#santiago cabrera#luca pasqualino#howard charles#tom burke#constance bonacieux#behind the scenes#the musketeers bts#period drama

913 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE MUSKETEERS 10TH ANNIVERSARY REWATCH / fave episodes [3/?]

↳ SEASON 1, EPISODE 8 / the challenge

#themusketeersedit#the musketeers#perioddramaedit#perioddramasource#the musketeers bbc#d'artagnan#aramis#porthos#athos#tmrewatch*#edits#we're so back#i kept watching and reading fics but i couldn't find the time to gif in real time#but i can never say no to angst AND ot4 realness#literally what was the reason for that porthos scene if not 'beautiful king showing off his incredible skills ft his adoring proud bfs'#and i stand by that#also luca you'll forever be famous for your crying face i'm sorry i hope i don't sound insane#flashing gif /#i love them dearly i'm keeping them in my pocket

425 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Musketeers, ep.1x8

#the musketeers#musketeersedit#themusketeersedit#perioddramaedit#porthos#aramis#d'artagnan#athos#bbc musketeers#luke pasqualino#santiago cabrera#howard charles#tom burke#musketeers#bbc the musketeers#the musketeers bbc

230 notes

·

View notes

Text

season 1, episode 1: friends and enemies

#the musketeers#bbc the musketeers#athos#tom burke#porthos#howard charles#aramis#santiago cabrera#dartagnan#d'artagnan#luke pasqualino#themusketeersedit#themusketeersgifs

188 notes

·

View notes

Text

Porthos holding back D’artagnan from running into the burning Garrison after Constance + Athos holding back Porthos from running inside the burning Garrison after D’artagnan

THE MUSKETEERS

3.10 “We Are the Garrison”

#porthos#d’artagnan#athos#the musketeers#themusketeersedit#the musketeers bbc#perioddramaedit#requested

455 notes

·

View notes

Text

the musketeers + fall colors (insp.)

#the musketeers#bbc musketeers#d'artagnan#athos#aramis#porthos du vallon#luke pasqualino#tom burke#santiago cabrera#howard charles#musketeers#new obsession fully acquired here we go#i accidentally made these the wrong size at first but what can you do????#my gifs

668 notes

·

View notes

Text

There is no piece of literature that has affected me as much as bbc The Musketeers fics

#specifically nor mars his sword#and my hearth upon my sleeve#fucking masterpieces#also not just notches#i should make a list#bbc#bbc the musketeers#the musketeers#aramis#athos#porthos#bbc porthos#bbc aramis#bbc athos#regulus rambles#fan fic#fan fiction

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

happy ten year anniversay musketeers!

#bbc musketeers#the musketeers#musketeersedit#porthos#constance bonacieux#d'artagnan#aramis#athos#**

450 notes

·

View notes

Text

Well. Musketeers for sure gets my odder fics. Someone aaaaaaages ago suggested Porthos adopts a kid, and I did a half arsed job of it, and now I have done a second bad job at it hahaha. I love Simone though and Porthos. Here you go, it's great!

WARNING: cold, hunger

It got pretty cold in winter time, that’s true of most places and like most places the cold was fine as long as you had money. Fur-lined clothing, extra layers, boots! Boots were great for cold. Fuel, endless fuel for hot fires, heating the houses top to bottom (bottom to top really, seeing as heat rises). Food, too; being well-fed was important in cold weather, good food, hot food. Cold was free, heat was expensive (until summer rolled around when somehow, that cold which cost nothing was suddenly a commodity). Winter in Paris was a mixed bag, you didn’t have to be horrendously rich to be warm, but you fell somehow easily into poverty if you weren’t careful, and there the cold waited, crouched, cracking frosty fingers against the glass, ready for you. Cold hid in corners with beggars and chased anyone marked ‘criminal’, snapping at their heels for the moment they stopped running and their sweat turned to cold damp, wet creeping into clothing, freezing through to bone. Cold dragged at the heels of children walking to their jobs, if not carefully shrugged off they might be sluggish, lose their work.

Some had no work. The poorest slunk down into the cold, the familiar embrace almost a comfort, inching into the lee of buildings, walls, under houses, through any unlatched door that might go unchecked for an hour or two. Simone had passed even this stage, sitting out on a step looking up at the frozen stars stretched achingly across the crackling sky. Paris was inhospitable, dirty, and smelt worse than the thickest stenching manure. The cold wasn’t the only thing at large in the city, either. Paris didn’t rest its head and take to its dreaming, when night fell, not in these parts. Men and women, clawing their way out of varying degrees of frozen cold, drank and sang and reeled past, blurring and sliding. Soldiers, guards, Queen’s Musketeers, policed the streets in their warm cloaks and boots, according to their whim, depending on their mood, how cold their shift had been. Violence stirred.

Paris lay around her like a great carcass, sprawled, feast and famine, decay and new life, and bones.

“You hungry?”

Simone didn’t know much anymore, numb with cold and half dead, but she knew this much; yes, yes she was hungry, as ravenous as Paris. She took what she was given, and took more from his pockets and bag, and took the cloak he offered and the gloves he didn’t, scarf tucked under the cloak, hidden. As he left her, he whistled a jaunty song, turning at the end of her ally.

“Paris is beautiful at night, but just you wait until I show you what them stars look like out there were there’s no lights.”

Simone followed him, unnoticed, a mere shadow among shadows, and found his back door. It was always good to know where the kinder lords lived, to know where you wouldn’t be beaten for taking scraps. He had stables, horses, hands who lived above in the hayloft and boys who slept with the animals but no one sleeping behind, out in the cold but warmth just the other side, close enough to touch, seeping through the woods.

“Morning’s here, little bundle of bones. If you give me back me gloves, you can have breakfast. And better gloves.”

Simone ran, before his hands could close around her arm and his big voice could call her thief she ran. His voice chased her, calling her to come back any time, and a polite request, again, for his gloves returned next time she was passing.

They had come to Paris for hope and life but Paris had eaten them, swallowed them up.

She went back. Found him, after midnight, sitting out there singing. He gave her food again, swapped her gloves for a pair that fitted, tossed her a pair of stockings and boots. She wanted to ask why, but he wasn’t watching her, he was writing. She gathered up her bounty and left. Paris wasn’t so cold with boots.

Next time, he wasn’t there. He was gone.

The men were rough. Men who barely contained their violence, wouldn’t have felt the cold even if they weren’t swaddled in layer upon layer of red, their bright hard steel chilling but not to them, just to those they dragged off the cold streets and threw into the colder cells, and left there. You couldn’t see the stars from inside a cell, couldn’t run, couldn’t piss except on the floor, couldn’t eat except the rat-bitten bread they threw at you when they remembered, fruit they’d let go rotten, couldn’t sleep unless you were ready to die. The cells were stone, stone held cold like it coveted ice, held you in that same embrace and tried to burn your bones frozen.

“You could, I s’pose. I’ve only got a knife on me. C’mon, test your hypothesis boy. You a coward, boy? Not gonna fight afterall? Hahaha! Pig fucker!”

The guard of the cells that night sometimes mildewed the carrots especially before tossing them down, whether or not they reached the cells he didn’t care. He was tossed down like his carrots, a great giant coming after laughing, plucking him up like he was nothing and slinging him over a shoulder. He opened the cell by jamming a knife into the locks and kicking it, the line of bars and locks shuddering under the heel he drove against the handle with such force the lock shattered.

“Bring that,” he said, looking down at Simone.

She brought the knife and followed him home, whistling between her missing teeth to keep tune with his whistling, his knife tucked into the rope she wore as a belt. They walked through the city like they owned it, Simone thought maybe he did. He stopped to throw the guard under an arch, leaving him on the frozen cobbles like garbage he no longer wanted. It was a long walk, she followed him right up the steps and into the hall before realising it.

“Kitchen’s through here. Water over there.”

He sat and cleaned the knife, he didn’t watch her at all. Her hands got in everywhere, bread and fruit and good vegetables, uncooked pastry ready for tomorrow, burning-hot chestnuts in the banked fire.

“Don’t burn your fingers,” was all he said, pointing her again to the cool water when she burnt her fingers on the chestnuts anyway.

She lay that night under the stars behind his stables, stomach hurting from eating so much, cold soaking from the ground into her thin dress, her skin, her blood, her bones. She wondered who he might be.

“Porthos,” he told her, from the back step, the next morning.

“Did I ask?” she rasped.

“No, which is rude. I want my knife back,” he said.

Simone did not return his knife.

It wasn’t Simone’s fingers in the pocket of the lady but it was Simone the lady saw, because it was Simone who was too frost-bitten and too hungry to duck into the shadows. The fingers of the rich were bony, for all the good food they ate, pinching and sharp and unrelenting. Tossed after the guard from the other week, brittle from cold, rolling unceremoniously into boots. Queen’s Musketeers policed as well as Red Guard. Their sympathetic warm eyes hid behind orders and duty. Simone kicked and bit and ran.

“She’s not here, captain. I’m due back on the front in three days and you want to make our goodbye acrimonious, over some scrap of a thief you thought you’d arrest?”

“Madame is mistress to our cardinal, Porthos. Mazarin demands, and we follow orders.”

“Since when? Go jam a long-sword up your arse, d’Artagnan, it’ll give you a better backbone.”

Kitchens were warm, in winter. Monsieur Porthos mostly lived in his kitchen, so Simone found a corner in there for herself. She learnt, from him, how to tend to the fires, and how to roast chestnuts. She made them for him, and ate most of them herself. He brought her clothes again, and cleaned his knife (his fingers lighter than hers, retrieved when she was looking right at him without her knowing).

“You’ll need to stay here, while I’m gone. Eat, rest, stay clean and tidy, no one’ll look twice. Wouldn’t recognise the difference even between you an’ me, Simone. I haven’t got time to teach you much, but I’ll show you your name, and my name.”

He showed her a few more words, too.

Porthos was gone for a long time. The kitchen was warm, and then they started propping the back door open to keep it temperate, and then it was sweltering. As long as she lived in the kitchen she was expected to keep the fire and help out; the servants taught her how to cook. Now and then a letter would come with her name carefully, clearly written, and inside was the short note, the only thing she could read. She wrote back; his name on the front, hers inside, and the only sentence she could write.

Cities don’t out run the cold. It came around, as it always did, creeping under doors and through cracks, driving Simone behind the stove to sleep and read the growing pile of notes. She wondered who they were cooking for, if Porthos was not here. This was his house, they were his servants, and he was gone. Simone traced the words of his most recent letter. It was longer, and she didn’t know the words. She wondered what it said.

“Can you show me?” she asked the cook.

The cook, Simone didn’t know his name, looked flabbergasted, and did not teach her to read. Instead he talked and talked about her scaring the living daylights out of him, as he’d thought her mute or stupid. She was neither, but she decided to be both in the face of his bad manners. When the cold started retreating, though, and another letter came, even longer, even smaller words, she asked again and this time he agreed. All through the stifling heat of summer they worked, in any moments that were his own, which were few and far between.

He taught her how to use a knife one way to cut meat, another to cut vegetables, and yet another way that would go right through a man. He showed her on his own stomach the place to find the guts, and how to tug up to guarantee death. He taught her how to read and write ‘eviscerate’.

Autumn came with rain and mud and a thin chill, cold air setting everyone coughing, and Simone could read the first longer letter. Porthos wrote to her about stars, horses, longing for good food, and ended by saying he missed her company. Simone kept the letter in her pocket for a week, while she learnt how to bleed, kill, dismember, and cure a pig. They packed the meat in salt and built an ice-house in the yard. One night Simone crawled in, trying to remember being as cold as the preserved meat. The cook’s boy dragged her out by her ankle and told her if she wanted to die she would not do it on Baron du Vallon’s property.

That explained why they were still working when Porthos wasn’t here; it wasn’t his house, it was this du Vallon’s. She heard more stories of him, and he sounded terrible, larger than life, richer than a god, remorseless. She crept behind the chimney to her bed and took out the longest letter yet, working on reading Porthos’s words to banish this terrifying baron.

That year, the winter lasted too long. Porthos’s letters came with small parcels, sometimes, and sometimes in bundles, and got shorter and shorter, until they were back to variations on words she knew so well. Still the winter came on, storms came up the Sein, ice coated the Parisian streets, rain came down day after day, washing away snow until another freeze came.

Spring didn’t arrive, but Porthos did.

Simone heard him and ran through the house, forgetting the baron who lived somewhere in its depths eating enough for several families, never seen. She ran down the front step and Porthos was waiting there for her, broad and beaming, soaking wet, his armour when he lifted her freezing against her skin.

Porthos took her out of the kitchen and upstairs, into rich, opulent rooms. They were brought hot water and she watched him wash, cleaning away dust and mud and, underneath, blood. She could smell it, like when the pig sat woozy and dying, bleeding for their black puddings. He wasn’t woozy, nor was he dying. He sang as he washed, songs about her, about the stars, about Paris. Once he was clean and dressed, he sent for more water, and dunked her head gently in, washing her hair with firm fingers, warm oils. He dried it and combed it with a wide toothed comb, her curls kinking more tight than his.

“This is my daughter, Simone du Vallon,” he introduced, as they walked about Paris, she holding onto his arms. “Found her in the vegetable patch under the stars, monsieur, like a discarded pumpkin.”

He bought her roast chestnuts on a corner, the seller staying as late as the winter this year, and shelled them for her.

“You can pay the cold to stay away,” she said, hands warm around the hot bag.

“Yeah,” he said.

He, too, knew that cold bit, she could tell. He, too, knew the bitterness of buying their heat, leaving everyone else behind.

“My sister died,” she told him, pointing out the last house they hid under.

The spring came. Simone showed him how well she could shoot, and told him that they showed her how to kill a pig.

“I thought you came here from a farm,” Porthos said, correcting her grip on the small pistol.

“This is bad form.”

“Yes, but you have small hands. Form was written for people with bigger hands.”

“I have forgotten everything before I came here to this house.”

“Remember it whenever you like, even if it’s as bloody as slaughtering pigs.”

Simone showed him the ice house, the last of the meat, and he lay down on his back, she snuck against his side, and they wondered what it used to be like, to be this cold.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE MUSKETEERS

↳ 1.01 // 2.02

204 notes

·

View notes

Text

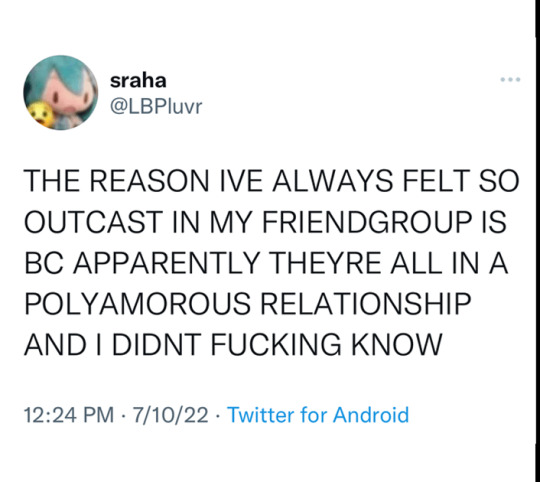

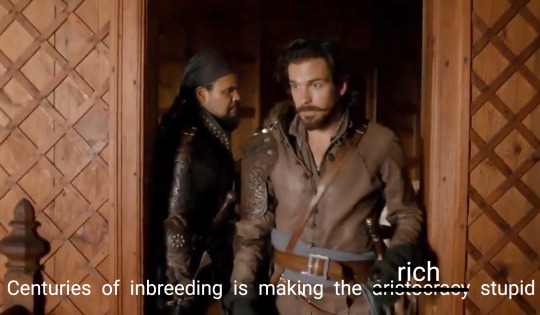

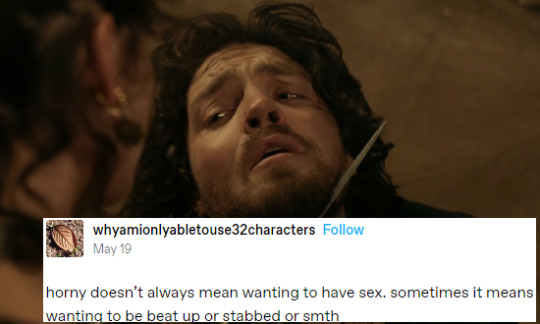

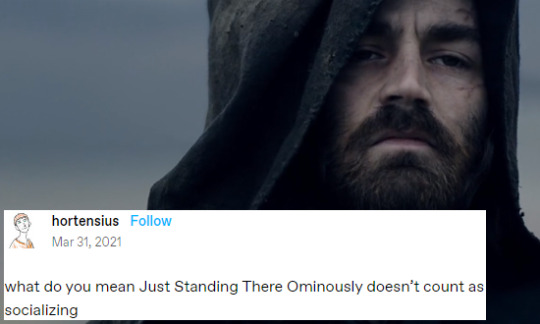

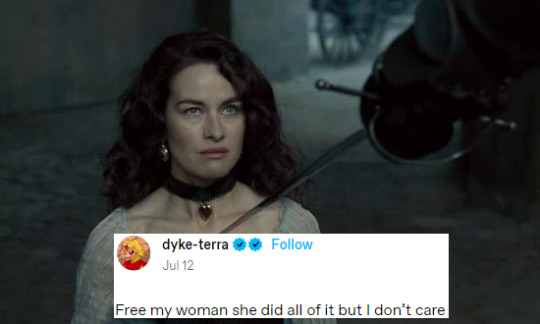

The Musketeers + Tumblr text posts, 3/?

#yeah i'm not done yet#themusketeersedit#the musketeers#the musketeers bbc#athos#porthos#aramis#d'artagnan#sylvie bodaire#constance bonacieux#captain treville#cardinal richelieu#lucien grimaud#milady de winter#alexandre dumas#has next to nothing to do with this but i need author tags for organizational purposes#my stuff

771 notes

·

View notes