#blackhistoryeverymonth

Text

Loving this so much 🥰 I definitely have to do more like this! 🤎

Song: The Staple Singers - Respect Yourself

#blackhistorymonth#blackhistory#black culture#nina simone#chaka khan#blackisbeautiful#black music#black tumblr#blackhistoryeverymonth#Spotify

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

i can feel the peace

#asexual#black women#art#artist on tumblr#blackhistoryeverymonth#photoart#photoshoot#creative#contentcreator#black girls are beautiful#ace culture#christian blog#ethereal#my muse#pieceofart#black girls#black girls of tumblr#black girls rock#black girl fashion#y2kcore#black girl aesthetic#fairy aesthetic

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Symone Seven

#black women#aesthetic#art#blackgirlmagic#black femininity#black girl aesthetic#beauty#afroamerican#blackhistoryeverymonth#blackhistory365#black models#photography#natural hair#ancestors#brown skin#dark skin#afro

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

big mami

ig:raeskrilla

#blackout#self improvement#self love#blackhistoryeverymonth#rastafari#melanin#caribbean#dreads#african#redhaiired

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐤𝐢𝐝𝐝𝐨𝐬 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐈 𝐝𝐞𝐜𝐢𝐝𝐞𝐝 𝐭𝐨 𝐯𝐢𝐬𝐢𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐊𝐚𝐥𝐚𝐤𝐮𝐭𝐚 𝐌𝐮𝐬𝐞𝐮𝐦 𝐭𝐨 𝐥𝐞𝐚𝐫𝐧 𝐚𝐛𝐨𝐮𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐥𝐢𝐟𝐞 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐥𝐞𝐠𝐚𝐜𝐲 𝐨𝐟 𝐅𝐞𝐥𝐚 🤍

Kalakuta Museum Lot by @shopheritage Link

#blacksimmer#sims4#sims#sims4roleplay#simstagram#sims4rp#ts4#ts4 story#sims4poses#simslove#Dani#kiddos#blackhistoryeverymonth

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prince: Emerging Black Identities in the 1980s

Breaking Stereotypes, Defining Black Excellence

Every few decades, a musical artist registers on our cultural radar that redefines a sound of a generation. See Taylor Swift. In the 1980s, that artist was Prince Rogers Nelson. Born in Minneapolis, MN, Prince released his second album, Controversy, in 1981. Only twenty-three at the time, he captured the imaginations of critics and funk fans alike. But the nation-at-large was not ready for an “album posters show[ing] Prince in a shower stall, half-naked and dripping wet, posed next to a small crucifix.” Expressions of black sexuality, as proliferated by whites. Those who have held ignorant, fucked up, and racist views, prove how the fetishization of blackness since first Africans touched terra firma.

Malcolm X said, and Denzel Washington made famously, “We didn’t land on Plymouth Rock.Plymouth Rock landed on us.” X’s racial metaphor was a reinterpretation of DuBois’ metaphor of the veil. Both men, having had access to information that negated white-perceived notions of biological differences between the races, could have also applied the same philosophy to gender. Labeling race and gender do nothing more than cloak individuals by controlling and setting societal norms, while also moderating and moralizing personal behavior. Labels like male and female or black and white are not intuitively defined but are learned patterns of behavior set by their Anglo-American parents. Those teachings firmly reinforced the fear, racism, sexism, misogyny, anti-intellectualism, selfishness, and entitlement that whites have enjoyed since the rape and genocide of Indigenous peoples.

Anglo-Americans were waking from their 1970s slumber as a certain slack-jawed president, awed by the “disgusting” cultural events of the 1970s (gays, disco), promised “Morning in America” at the decade’s open. Luckily, President Frederick D. Roosevelt had already signed into law a policy that forbade racial discrimination in government services including contractors and all other government-contracted agencies. The impact of the law raised the incomes of many black families. As Black Americans continued to gain strides in the middle-class, Anglo-Americans’ assholes pinched even tighter.

In the wake of the civil rights struggle, fissures grew in the black community as more blacks, mirroring the trajectory of their white counterparts, fled the ghetto for the relative safety of the suburbs. Fearing the encroaching darkness, whites (and some blacks) found political comfort in the only place they knew to look, in the arms of their white daddy, Ronald Reagan. Burning disco records were not just backlash against the music itself. Anglo-Americans who sat at the top of the nation’s music industry revealed received ideas about the black and feminized culture it produced.

Steve Dahl is famous for one thing alone, blowing up disco records. In 1979, the Chicago disc jockey promoted an event that was designed to fill seats at a double-header at Comiskey Park, but it “turned into a mass anti-disco movement from which disco never recovered.” After factoring in the musical artist, music genre and popular culture, and trending “street” styles, America has, throughout history, been gender-coded by its space and time as either feminine or masculine. Disco, heavy with black, female, and gay participation as both musician and spectator, was received and gendered feminine. Therefore, anything or anyone who claimed association with disco was accused of being a part of a secretive, gay, black cabal whose sole goal was to tear asunder the fabric of our great, white, paternalistic nation.

Out of Dahl’s ashes, rose a beautiful, black, sexually ambiguous Prince. Nelson George wrote that “no black performer since Little Richard had toyed with the heterosexual sensibilities of Black America so brazenly” It is true that Prince’s performances of gender and race were rooted in a deep history of black artistic expression, but like his slow-to-appear successor, his popularity was predicated on his ability to influence the social agenda. Unlike Little Richard, however, Prince had MTV (Music Television). Although resistant to incorporating black acts into its line-up, MTV would prove to be the greatest tool for disseminating popular culture’s blueprint.

The 1980s stand as a decade of massive change in the United States. Back scholarship on race and gender were being seriously studied. Reaping the rights that Anglo-Americans had stolen from them, Black Americans entered more institutes of higher learning aided by Affirmative Action and desegregation. Middle-class blacks seized greater control over our own images unmitigated by stares from Anglo-Americans. Just as DuBois had predicted, the talented tenth proved responsible for changing Anglo-America’s perception of what, exactly, it meant to be black in their own country.

Prince led the musical pack with his gender-bending offerings echoing the early years of David Bowie’s career. Prince blurred the lines between masculine and feminine clearly upsetting the binaries held by most Americans. And he was black? Prince confirmed what Anglo-Americans already feared. After lifetimes of fear-mongering and pearl-clutching, their worst dreams came true. Their Anglo-American daughters were all about Prince. They loved him. They even wanted to (gasp) fuck him! And that’s what happened. White girls drove all into Black American females’ lane. That’s why we’re a nation of multicultural/biracial individuals. Coffee colored, indeed.

What is most interesting about Prince is that he defied preconceived notions of what blackness and, black sexuality were. Unlike Michael Jackson who refused to acknowledge his sexuality (Elvis’ daughter? Really?), Prince refused to be veiled by his audience or critics. In the lyrics to his song “Controversy,” Prince asks, “Am I black or white/Am I straight or gay?” By asking others to clarify and define who he is, he exerts full control by refusing to be limited by what those questions infer. As a nation built upon divisive racial and gender practices, we have been conditioned to view others based upon exterior representations of self.

Similar to DuBois’ urgent call for the black community to control or own their images, Prince had already established a tight grip on his self-image by the time he became the youngest producer in the history of Warner Bros. Records. This “first” was largely ignored due to the mainstream press’ obsession with categorizing the artist not based on his musical abilities, but on their perceptions of gender and race. Shipler writes, “The notion that blacks are not as smart, not as competent, not as energetic as whites is woven so tightly into American culture it cannot be untangled from everyday thought,” These ideas are exactly what DuBois’ argued veiled his people.

Prince’s image becomes an obsession with white critics leaving both blacks and whites to question his authenticity. “When he's off, his bombast and swagger seem flimsy and forced, a cheap charade,” wrote one critic in a review for the Chicago Sun-Times that referred to Prince’s music as a “mongrel mix of creamy ballads and brittle funk” before calling the artist a “silly poseur.” Because whites have traditionally been in charge of the media they controlled both how whites saw blacks and, worse, how many blacks saw themselves. But, again, Prince challenged the veil by presenting himself precisely as he wanted.

It has been over 100 years since DuBois declared the problems of the 20th Century would be racially motivated. He was prescient, indeed. With blacks entering the middle-class in record numbers, however, racial veils parted once gaining control of black representation. On the micro-level, Prince refused to allow the color of his skin to keep him from expanding personal boundaries. Anglo-Americans, except for some white females and white, gay-identified individuals, despised Prince for the same reasons they roundly ignored Ernie Isley. They played better than they could. Anglo-Americans have never produced any music that did not exist in black communities. We invented soloing, for instance, something that is credited today to white musicians. Prince’s accomplishments paved the way for the many blacks who wanted to live their truth.

While Prince reveals the emerging identities of blackness that appeared in the 1980s-today, there are several other examples from R&B to punk. He is a symbol of Black American freedom. Prince, of course, went on to become one of the nation’s most controversial artists of the 20th Century. Constantly toying with his image, he mitigated opportunities of veiling by successfully counter-veiling (revealing) his critics as homophobic and/or racist. Like DuBois before him, Prince knew that “life is just a game/we’re all the same” freeing himself from racial and gender stereotypes. Whether consciously or not, Prince understood the power of history, not just remembering it but creating it too.

#prince#miscegenation#race#americanracism#blackness#whiteness#blackidentity#music#musician#funky#racism#black history is american history#blackhistoryeverymonth#white thievery

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

My guy Chubbs getting ready to heat the summer up!

@chubbs_flee

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jackie Ormes (August 1, 1911 – December 26, 1985) was an American cartoonist. She is known as the first African-American woman cartoonist and creator of the Torchy Brown comic strip and the Patty-Jo 'n' Ginger panel.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jackie_Ormes

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

TIC TAC TOE - AFRICAN ANIMALS ELEPHANT AND LION

This beautifully crafted Tic-Tac-Toe board game board game will make the perfect gift for lovers of wildlife and Africa. The noughts and crosses substituted with different African animals, which has been hand-casted and hand-painted in incredible detail, showcasing these species in all their grander and splendor.

As this is a small board game, it is the perfect option for shoppers with limited space and budget.

The game, known in Africa and Europe as Noughts and Crosses or "X" and "O's", in North America as Tic-Tac-Toe is normally played on a piece of paper by drawing x's and o's in boxes. African Tic-Tac-Toe is the same game on with different components representing the African continent.

Play a game of "X" and "O's" with Lions and Elephants, or display the African game as an art piece in your home. .

This pieces, both of which have been cast by hand in polystone (a mixture of resin and crushed stone), from a hand-made mold. Thereafter, the board and playing pieces are hand-painted in exquisite detail by a skilled team of local community artists, using Winsor and Newton oil and acrylic paints. The crafting process from beginning to completion takes approximately four (4) hours.

Dimensions of board - approximately 6-1/2" x 6-1/2". Animal pieces approximately 1-1/4" high.

Please PM me with any questions and pricing inquiries, or email me at [email protected].

Thank you.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Black History Month

#black woman#blackgirlmagic#black women#blackhistory2022#blackhistorymonth#blacklivesmatter#black men#black melanin#grey hoodie#blackhistoryeveryday#black365#buyblack#mlkday#america#blackhistoryeverymonth

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rev Velma Maia Thomas talks about the hidden messages in negro spirituals 🖤

Happy Black History Month 🖤🤎🖤🤎

#black culture#blackhistoryfacts#blackhistoryeveryday#blackhistory#blackhistoryeverymonth#black history matters#blackhistorymonth#blackisbeautiful#black music#blackpower#blackpride#black panther#harriet tubman

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

(Source: IG, black women's lives matter)

#black women's lives matter#black lives matter#black women#blackhistorymonth#blackhistoryeveryday#blackmoms#blackhistoryeverymonth#black beauty#brown skin#black girl

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

#drawing#original character#artists on tumblr#digital art#artist#illustration#artwork#graphic design#art#digital painting#tumblr draw#blackhistoryeverymonth

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Norah Jones-Don't Know Why

#music#blackgirlmagic#singing#blackhistoryeverymonth#womensupportingwomen#women history#words#singersongwriter#coversong#norah jones#sza#beyonce#jazmine sullivan#jheneakio#blackpink#911

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

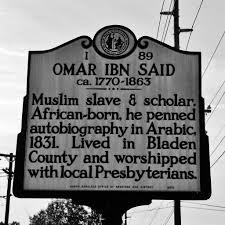

BHM: the life of omar ibn said

In today’s racially charged climate, the call to learn from and reckon America’s violently colorful history with people of color has reached a fever pitch. In order to move forward, we must first study our past. This Black History Month should be more than just a time elementary school teachers rattle off facts about Madam C.J. Walker and George Washington Carver. Rather, we as a people must use this opportunity to allow ourselves to feel the long suppressed pain of our black brothers and sisters so that we may begin to heal together. Surely, much of the racial injustice that is prevalent today stems from the conscious decision to enslave masses of people against their will whilst forcing them to desert their culture, land, and families.

One such story is that of West African slave and author Omar ibn Said. In early 2019, the Library of Congress acquired the Omar Ibn Saeed collection, including his original Arabic autobiography written in the early 1800s, along with its English translation The Life of Omar Ibn Said from the 1860s. Now that these documents have been made public, we have access to firsthand accounts of slavery in America which are unedited by ibn Saeed’s owners, unlike other slave’s autobiographies that were written in English. In fact, many of the accounts of slavery and the treatment of enslaved people we read today are derived from white abolitionist writers, rather than black enslaved people. This is often because slaves did not have the time, the ability, or the resources to record their conditions, and even if an enslaved person did dare to write an autobiography, he or she risked being caught by an “owner” and being severely punished. Still, there are written accounts of some enslaved people’s experiences, but these accounts are tainted by the possibility of being dictated or altered by an “owner”. What makes ibn Said’s work exceptional is that he chose to record his life in Arabic, a medium his “owner” was unlikely to have been able to read, let alone contour to his whims. Due to his foresight, today we have access to a work that facilitates an enhanced understanding of the complications of slavery in America and what it meant to be Muslim in the 19th century.

Ibn Said begins his autobiography with Al-Mulk, the sixty-seventh chapter from the Quran. After praising Allah ﷻ and sending salutations of peace and blessings upon Muhammad ﷺ, he begins quoting the Quranic passage,

“Blessed be He in whose hand is the kingdom and who is Almighty; who created death and life that He may make you the best of his works” {67:1}.

It is no accident that ibn Said chose, out of 114 chapters, consisting of a total 6,236 verses, to begin with Al-Mulk, which means “The Sovereignty.” The very first ayah (verse) he pens establishes that Allah ﷻ is the owner of all and that he controls both life and death, which leaves no room for the ownership of man over any form of life. “It is a fundamental criticism of the institution of slavery,” says Mary-Jane Deeb, chief of the African and Middle Eastern Division at the Library of Congress.

Personally, what I find astounding is the stark contrast between his manner of writing and the way in which other writers of the time incorporate religion into their work. For instance, we can observe a less nuanced tone in American author Ralph Waldo Emersons’ "Nature," published in 1836, in which he declares,

“I become a transparent eye-ball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God.”

While Emerson sees God through the world around him, ibn Said understands the world around him through God. Perhaps this difference arises as a result of each writer’s position in life. Emerson already had access to material possessions, which led him on a journey to “find” God amongst a world he had already defined materialistically. On the other hand, ibn Said had very little to nothing to his name, thus his world view was shaped by the beliefs he brought with him in the long boat ride over from Futa Toro. This fundamental difference illustrates the disparity of conditions faced by free and enslaved Americans.

Interestingly, when recalling his life within America, ibn Said’s description of his experiences do not mirror the general perception of enslaved life most carry. Although he does mention the abuse he endured at the hands of Johnson, the man who he was sold to in Charleston, his dislike for Johnson isn’t solely due to him being a “wicked man,” rather he repeatedly mentions that he “had no fear of God at all.” Contrary to the notion that enslaved people fled the persecution and excruciating labor of the fields as some form of refugees, ibn Said mentions in his manuscript that he made the choice not to stay with Johnson, as he, “was afraid to remain with a man so depraved and who committed so many crimes.” Yet, when speaking of North Carolina’s governor John Owen and his brother Jim Owen, who ibn Said “remained in the place of” after being caught, he describes them as “good men” and praises them for reading the gospel and “having so much love to God.” In fact, when asked if he “were willing to go to Charleston City,” ibn Said responds, “No, no, no, no, no, no, no, I not willing to go to Charleston. I stay in the house of Jim Owen.” Despite being able to depict the Owens in a negative light, given that they wouldn’t understand his criticism since it was written in Arabic, he talks highly of each member of the family and even refers to Jim Owen as sied, or master, postulating that enslaved people might have had a relationship of respect and fondness towards their “masters.”

Intriguingly, ibn Said never refers to himself as a slave, and speaks about his circumstances with a refreshing air of self- reliance. To him, he didn’t flee slavery in Charleston; rather, he left a “wicked man” who ibn Said made the choice not to stay with. Perhaps the aspect of ibn Said’s life that vastly sets him apart from the mainstream understanding of a slave’s life is his advanced education. While most enslaved people are regarded as being illiterate, ibn Said wrote letters and personal writings in beautiful calligraphy and had many passages of the Qur’an committed to memory. Along with his manuscript being evidence enough of just how highly educated he was, ibn Said writes, “I continued my studies twenty-five years,” which means he was only six when he first “sought knowledge under the instruction of a Sheikh called Mohammed Seid.” Similarly, the elegance with which he writes is truly a testament to his intelligence. Aside from his cross examination of Christianity and Islam, and his interwoven subtle critisms of the institution of slavery, ibn Said masterfully uses language that illustrates both his wisdom and humility as he looks back on his life. In fact, he even includes an effective introduction and conclusion to his work. From ibn Said’s outlook on life, which allows him to describe his “master” fondly, to his blaring sense of self-determination, he redefines what it means to be an enslaved person in America.

Ibn Said, within his autobiography, attempts to analyze the interwoven tale of his experiences in regards to both Islam and Christianity. He mentions his past rituals of walking to the mosque for prayer in the daytime and at night, and the zeal with which he read the Quran, all before he came to America. Yet, he repeatedly praises the Owen’s for reading the gospel, mentioning that they would read it to him, and implies that he may have converted to Christianity. Due to the many Quranic verses and prayers scattered in his writing, it is difficult to tell whether ibn Said truly brought faith in the Christian religion or only accepted it as an outwardly gesture to ensure his safety in the South. Either way, he was able to examine each religion objectively. At one point, ibn Said even contrasts the manner in which he prayed as a Muslim in opposition to how he prays as a Christian by providing the entire chapter of Al-Fatiha from the Quran, while adding that now he prays, “Our Father.” Interestingly, he never criticizes, gives his opinion on, nor shows a preference towards either religion. This neutrality drives home not only ibn Said’s intellect, but the fact that he was simply searching for the true path, without blindly following whatever he was told.

Perhaps what sets ibn Said apart from other enslaved people in regards to religious aspirations is his twenty-five years spent in seeking out knowledge in Foto Turo. This disciplined early education instilled in him a zeal which followed him across the Atlantic, allowing him to become a lifelong learner. In fact, he was eager to listen to the gospel whenever someone would read it to him. Although he doesn’t specifically mention that he is Christian, ibn Said places a substantially large emphasis on the relationship between God and human beings, as well as the need to read and understand scripture. Even if he remained Muslim, ibn Said never makes clear his opposition to Chrisitan ideology. Rather he reiterates the necessity of faith in one’s life by praising the Owens for being a religious family while cursing at his first “owner” Johnson for his lack of attachment to God.

Aside from The Life of Omar Ibn Said’s literary brilliance and historical significance when analyzing slavery in America, the work resonates with me on a personal level. When I first heard that the Library of Congress had published this work as a collection, along with other hand written pieces such as personal letters, my interest was sufficiently piqued. What I didn’t anticipate, however, is just how much I would relate to the story of a West African slave living in the 19th century. Before reading the English manuscript of The Life of Omar Ibn Said, I first made my way through the Arabic documents. Written in mesmerizing handwriting which, due to my severe lack of knowledge, I can only describe as 19th century African calligraphy, ibn Said begins with the basmallah. As Muslims, we recognize this prayer as one to recite before embarking on any task or journey, even as small as lifting the lid off of a pot. Then he goes on to send salutations upon the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ in a manner so customary that I caught myself doing so involuntarily. When I realized he was quoting surah Al- Mulk, one that my mother helped me commit to memory and would read with me every night before going to bed as a child, I was touched. Despite being stripped of his culture, isolated from his people, and forced onto a new land, ibn Said did not forget the essentials of his religion. It was at that moment that I resolved to start reciting Al- Mulk at night again. When he mentions the Shuyukh, or scholars, under whom he gained his education, I felt the respect emanating from his words. In that moment, the oft- quoted words came to mind, “I am a slave to the one who teaches me even a single letter.”

Perhaps the most striking part of ibn Said’s journey is the fact that while on the run for nearly a month, he risked capture to stop at a church and pray. Although he knew the inherent dangers that would stem from being apprehended, ibn Said’s imaan (faith) proved stronger than his fear, as he was eventually caught and sold back into slavery. In this defiant act of his, I find reasons to feel both ashamed and hopeful. Ibn Said actually faced the possibility of being killed, yet he still chose to preserve his religious traditions. Meanwhile, when prayer time rolls in while I am still on campus, I feel the need to squeeze into the tiniest corner I can find to quickly pray just the bare minimum so that I don't inconvenience anyone else around me. Yet, the fact that ibn Said was caught and sold to a man about whom he mentions, “During the last 20 years, I have known no want in the hand of Jim Owen,” is cause enough for me to be hopeful that the slight stress I endure while praying in public will surely bring about, through Allah’s ﷻ unlimited Grace, great fortune in my own life. Although we are separated by a span of almost two centuries, ibn Said’s struggle is inspiring in ways I couldn’t have anticipated.

In the ever-divisive times in which we now find ourselves living, The Life of Omar Ibn Said is a welcome triumph of human spirit and optimism. Not only are ibn Said’s life and work subjects of intrigue, but the implications of his writing reaffirm a story that many of us have long since forgotten: American slavery does not take one shape, size, or form. Although the institution itself was horrific, we must contend that some enslaved people did find a greater purpose in their lives. Ibn Said was one of them. He rose above the hatred surrounding him, and speaks of the men who held him in captivity with astonishing reverence. How ibn Said was able to look back at the progression of events in his life and not be angered that a scholar as learned as he could be enslaved is a lesson for us all. Truly, ibn Said’s knowledge provided him with humility and wisdom. Perhaps, if he had succumbed to human nature and only displayed outrage at his conditions, which would have been completely justified, we would not have the masterpiece that is the Omar Ibn Said collection today. As we continue to engage literature and history as a way of understanding the world, Omar ibn Said stands as a reminder to value the narrative of every individual, because, rather than a large-scale standpoint in viewing the world, personal experiences speak to the very core of what it means to be human. We all deserve the chance to live prosperously and this cannot be the case until we rectify the mistakes of our past and work towards ensuring the sanctity of every life.

Carey, Jonathan. “The Extraordinary Autobiography of an Enslaved Muslim Man Is Now Online.” Atlas Obscura, Atlas Obscura, 26 Jan. 2019, https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/omar-ibn-said-autobiography-digitized.

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. “Nature.” EMERSON - NATURE--Web Text, https://archive.vcu.edu/english/engweb/transcendentalism/authors/emerson/nature.html.

ibn Said, Omar. “About This Collection : Omar Ibn Said Collection : Digital Collections : Library of Congress.” The Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/collections/omar-ibn-said-collection/about-this-collection/

#omaribnsaid#blackhistory#black history matters#blackhistoryisamericanhistory#blackhistoryisworldhistory#blackhistory365#blackhistoryeveryday#blackhistoryeverymonth#blackhistory2021#black history year#blackhistoryfacts#blackhistorymonth#african american#africanamericanhistory#african#africanhistory365#blacklivesmatter#blackamericans#support blm#blm2021#blm movement#black lives have value#black lives are human lives#black lives are needed#black lives still matter#black lives have always mattered#blacklivesalwaysmatter#black lives are important#black lives are worthy

2 notes

·

View notes