#blood of elves

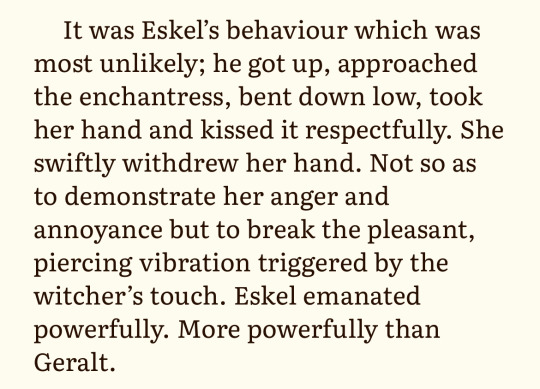

Text

ummmm he’s the man of all time actually. did you guys know that he’s courteous and a gentleman and willing to admit his mistakes and he has a powerful magic energy around him that's stronger than any of the other witchers And that he's also the sexiest man alive

#eskelposting#i think about this passage all the fucking time#one of the most men ever. for real#💕💕💕💕💕#witcher reread#blood of elves#witcher eskel

609 notes

·

View notes

Text

-the Academy had taken great pains to have him visit and give guest lectures. Dandelion yielded to their requests only sporadically, for his love of wandering was constantly at odds with his predilection for comfort, luxury and a regular income.

He's just like me for real

75 notes

·

View notes

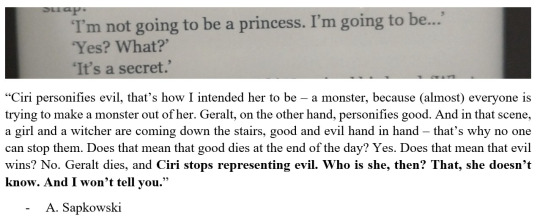

Text

🥲

That it was foreshadowed all along.

#wiedźmin#the witcher#the witcher books#ciri#cirilla fiona elen riannon#geralt#andrzej sapkowski#blood of elves#lady of the lake

260 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝘛𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦 𝘪𝘴 𝘯𝘰 𝘨𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘵𝘦𝘳 𝘫𝘰𝘺 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘯 𝘨𝘰𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘰𝘯 𝘢 𝘸𝘢𝘭𝘬 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘓𝘢𝘥𝘺 𝘠𝘦𝘯𝘯𝘦𝘧𝘦𝘳. 𝘈𝘧𝘵𝘦𝘳 𝘢𝘭𝘭, 𝘪𝘵 𝘸𝘢𝘴 𝘢𝘭𝘴𝘰 𝘢 𝘣𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘵𝘩 𝘰𝘧 𝘧𝘳𝘦𝘴𝘩 𝘢𝘪𝘳 𝘧𝘳𝘰𝘮 𝘢𝘭𝘭 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘥𝘢𝘺𝘴 𝘴𝘱𝘦𝘯𝘵 𝘪𝘯𝘥𝘰𝘰𝘳𝘴 𝘰𝘯 𝘩𝘦𝘳 𝘮𝘢𝘨𝘪𝘤 𝘴𝘵𝘶𝘥𝘪𝘦𝘴. ✨

-

Just finished rereading Blood of Elves and I think I can reread Chapter 7 forever 😂 The development of their relationship is just too cute and heartwarming...and I always picture them walking back to the temple together after their excursions outside, with Yen holding Ciri's hand tightly :') I really wish the game and the books had more of their interactions together, other than just the earlier books 🥲

Yennefer and Ciri outfit mod by ringkvinna , Yennefer hair and Ciri's headband by @witcherscreenshotsdump ✨

#the witcher#the witcher 3#the witcher books#witcher fan art#tw3 mods#yennefer and ciri#yennefer of vengerberg#cirilla of cintra#ciri#ellander#yennefer#blood of elves#geraltyen of corvobianco#archive of the continent

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

i think we as a society should indulge in trans masc ciri a little bit more

#girl i thought this when i was 12 too#not very cis in my humble opinion#transphobic triss smh /j#if we are being real medically transitioning in the witch’s universe isn’t far fetched at all#yennefer’s transformation is more physically changing than like top surgery or bottom surgery tbh!#also ciri is already like canonically queer so her being trans masc doesn’t actually seem that far fetched#the witcher#the witcher books#blood of elves#the witcher blood of elves#ciri#cirilla of cintra

278 notes

·

View notes

Text

Missing scene from Blood of Elves. Coën argues with Lambert about responsibility, nobility and their fate.

“I believe that. But I’m not gallant enough. Nor valiant enough. I’m not suited to be a soldier or a hero. And having an acute fear of pain, mutilation and death is not the only reason. You can’t stop a soldier from being frightened but you can give him motivation to help him overcome that fear. I have no such motivation. I can’t have. I’m a witcher: an artificially created mutant. I kill monsters for money. I defend children when their parents pay me to. If a Nilfgaardian parent pays me, I’ll defend Nilfgaardian children. And even if the world lies in ruin—which does not seem likely to me—I’ll carry on killing monsters in the ruins of this world until some monster kills me. That is my fate, my reason, my life and my attitude to the world. And it it not what I chose. It was chosen for me.” —Geralt of Rivia in the Blood of Elves.

Coën drew in a deep breath through his nose. The smell of pine filled his chest, mixed with the subtle fishy odour of the lake, and the sprawling bryonia clinging to the rocky outcrops at his back. The mountains around Kaer Morhen were peaceful and familiar in a way that made his chest tight and his eyes prickle; it reminded him of home. He didn’t resent the ache, but cherished it, for it was one of the few things he had left. A tenuous link to something he could never get back.

His head lolled back between his shoulders and he held that breath deep in torso for as long as he could, expelling it through pursed lips only when the ache became a tight pain. Splashing at the lake edge drew his attention and he watched through slitted eyes as his companion stumbled ungracefully through the shallows.

When Lambert had invited Coën to winter with him, Coën had accepted without hesitation, and had been most bewildered by the relieved grin on Lambert’s face at the time. It had been many years since Coën had wintered with other witchers, and Kaer Morhen’s hospitality had not disappointed. Lambert seemed to be bending over backwards to make sure Coën was included in every part of the wolf’s life here, and for that Coën was grateful.

“Ahh, just as bollock-shrinking cold as always!” Lambert crowed, before swearing as he stubbed his toe on a pebble buried deep in the silt and sand. It was an uncharacteristically warm day, but the mountains could be like that. When the skies cleared and the snows had cleared a little, it could almost feel like early summer, when the cool spring breezes stirred the first buds of wakening meadows but your cuirass became itchy and close.

Lambert flopped down on the threadbare tablecloth they had pilfered from Vesemir’s kitchens as a makeshift picnic blanket—Lambert’s words, said with a wry smirk as they had tiptoed out of the larder like errant trainees. He ran a hand through his dark hair, ruffling it out to dry. Not for the first time, Coën was struck by just how good-looking his companion was when the lines of anger and frustration had smoothed out, the shadows in his yellow eyes chased away by good sleep and good food. “Urf, fuck,” Lambert lifted his hips and pulled the damp cloth of his trews away from his crotch.

“Dunno why you didn’t take ‘em off,” Coën said lightly, tilting his head back again to bask in the warmth of the sun some more.

“Told you, not the type of tackle I tend to fish with. If you’d seen the teeth on some of the fish I get from here, you’d understand why.” Lambert shuffled some more and flipped to his front to grab one of the unopened bottoms of ale tucked in the shade of a large boulder. “No drowner spawn that I could find in the usual places. No idea about the far banks though, that’ll have to wait ‘til—,” Lambert waved vaguely towards the derelict old boat he had been working on half-arsed for the majority of the morning.

“Mmhm, and when’s that then?”

“Fuck knows. Between Geralt’s princess and Vesemir bellyaching about the west wing falling down on his head, dunno when I’ll get back down here.”

Coën opened his eyes, squinting into the great expanse of unclouded blue above. Cirilla. Sweet child, mischievous and bright, despite all the trials and loss she had faced. And yet, the shadow of destiny loomed over her, ever present and threatening. Coën had hoped that, with Triss’ arrival, they might have felt slightly more sure of her path forward, but the magess’ presence seemed to have brought new tensions to the fort. The wolf witchers had invited her in, and yet not a single one seemed to trust her intentions, except old Vesemir, who seemed relieved to have someone take a little responsibility from his shoulders; the girl was beyond even the old wolf’s knowledge.

Geralt appeared somewhat exhausted by her and Coën sensed by her advances that there was a history there that Geralt did not wish to revisit, Lambert was confrontational and ice cold, even more so than usual, and Eskel was the most peculiar of all. He was beyond polite, magnanimous, quick to take the knee and open doors for the magess, scurrying around the castle at her beck and call; if Lambert hadn’t told Coën which way Eskel’s appetites leaned, Coën would have assumed it to be flirtation. Yet, it had been Eskel that had gazed at Triss with distrust and apprehension when they had discussed her whisking Ciri away to her Chapter as in days of old.

They had called Triss out of desperation, but not a single one of the wolves were willing to let her take Ciri from them. They were guarded, protective, Lambert perhaps most of all. He treated Merigold with open disdain, dismissing all pleas from his brothers and master to remain civil. Coën surmised it might be more than a distrust of mages in general, but he hadn’t found the opportunity to probe further.

“None of you trust, Triss Merigold. That much is obvious. But Ciri’s peculiarity worries you. Would it not be best for Triss to take on the burden? To let her take the child with her to Aretuza or wherever destination she has in mind?” Coën asked.

Lambert didn’t answer immediately. They had spoken some of the school’s previous experience with such a girl, but the conversation had been stilted and tight, like it was a source of pain and shame. Coën found out little of the girl’s fate, only that she had left her mark on one of Lambert’s kin. Lambert sighed. “N’aw, she’s just another lost kid. Nothin’ new, nothin’ special.” He didn’t look up as he said it, focusing instead on a blade of grass. “As I said, we’ll teach her the sword, let her grow big and strong, and she’ll be like any other warrioress out there.” He flicked the blade of grass away and drew a swig of ale.

“You don’t believe that. I know you too well, Lambert of Kaer Morhen, you may lie to yourself, but you cannot lie to me. You care for the girl, I’ve seen it. You wouldn’t drive her so hard if you didn't, and you would not see her whisked away by the magess. And yet you know there is more to her—”

Lambert rolled his eyes, settling them upon Coën’s face with one eyebrow quirked towards his scruff of dark hair. “It doesn’t make a difference either way. What can we do? Train her to be one of us, but without the poisons. This—that—“ Lambert waved over his shoulder vaguely southward, towards the majority of the Continent, “is so far beyond us, so fuckin’ bigger, we’re just witchers. We fight monsters, that’s it. We don’t get involved, no matter what Merigold might want. No matter the moralistic fuckin’ rants she wants to have over our own fuckin’ mead in our own fuckin’ keep. Arrogant bitch.”

Coën winced and fell silent, giving Lambert’s anger time to settle to an even ebb again. Such was the way with Lambert; whereas the older witchers of the keep seemed to have suppressed their emotions to the point of ambivalence, Lambert’s raged all the fiercer as if out of spite. It was one of the things that Coën admired so ardently about him; the way he took on the world unapologetically and refused to succumb to its darkness. When Coën sensed the turbulent waters had settled, he continued. “You agree with Geralt, then. That there is no side for us to take in this conflict in the South, no greater good for us to fight for.”

“The only greater good for us is coin,” Lambert murmured. “Come spring, we should head south and we can clear up in the wake of the armies. Wade through the shit and the corpses to find the monsters. It’s what we’re built for.”

Coën huffed. “You sound like a cultist reciting a mantra you don’t even believe yours—“

“Where’s this goin’? Out with it. I’ve had enough of politics, euphemisms and bloody philosophising from Merigold this winter; I don’t need it from you too.”

Coën gazed over the lake to the far bank where a mist hung unnaturally among the trees. Foglets, no doubt. The recorded voices and shapes of hundreds of trainees that had perished in the mountains. Souls that were never given the opportunity to realise their potential, to breathe free air beyond the confines of the brotherhood. “I’ve been thinking more on those orphans Triss spoke of. How she works to prevent them from being orphans in the first place, whereas we’re just there after the fact to pick up the pieces.”

“You let her get into your head,” Lambert shook his, adjusting his trews once more, nose wrinkled in discomfort. “She was just trying to take a cheap shot. Get a knife in your ribs and twist.”

“What if she’s right? We may be mutants, but can’t we rise above? Become more? We are worth twenty Cintran soldiers. Having witchers fight on the side of the North, we—we could turn the tide of this war, we—“

“Delusions of grandeur.”

Coën’s blood ran hot with anger. While he admired Lambert’s sass and sarcasm when it was directed at others, he didn’t much enjoy being the target of it. Such dismissal bit at him, and he didn’t much want to examine why it hurt so very much. “So we stand by and watch the world burn so long as we line our purses, how very noble. We pick over the corpses of children like graveir, thugs and mercenaries with yellow eyes.”

“I never pretended to be otherwise,” Lambert snapped back. “You seem to think we owe this world something. We don’t. You think they’d care if us mutants fought at their side? You think they’ll give you a fuckin’ medal? Accept you back with open arms? Write stories and songs about you? Grow up. You’ve got yourself all wrapped up in those fairytales you read to Ciri.”

“And so what if they don’t? It’s not about that—it’s about doing the right thing, it’s—“

“There is no right thing. There is survival. There is getting through another pissin’ year and getting back here. Drinking with the people who actually give half a shit about whether you live or die. That’s it!”

Lambert was shouting now, his eyes furious, and Coën’s belly had tied itself in knots. Defensively, Coën raised his own voice, shoulders bunching. “For you, maybe. But I’m done with it. Maybe I want to become more! Rise above. Maybe I want to fight for something meaningful, defend the innocent, protect the—“

Lambert’s eyes narrowed, his fist tightening around his bottle, and he spoke through clenched teeth. “Throwing your life away won’t bring them back, Coën. Get your head out your arse. They’re dead, and you’re alive. Foolish sacrifice for those who don’t give a shit about you is just that, foolish. You’re a witcher, not a hero, stop trying to be more than you were made to be.”

Lambert’s words cut sharper than any knife. His lip lifted in a sneer of what looked like contempt, but there was an unnameable hurt in his eyes. Coën couldn’t parse it, he couldn’t even begin to, because his own anger and hurt was making his head ache. “Then perhaps I am a fool,” he snapped, rolling to his feet and snatching his shirt from the grass. “And as my foolishness seems to vex you so, I shall relieve you of my presence.”

“Fine! Why don’t you scurry off to Merigold? I’m sure she could tell you exactly the best way to piss your life away on her crusade.”

Coën stalked away and didn’t look back. He found Eskel weaving baskets with Ciri in one of the stillrooms and sat with them. The older witcher studied him closely, one of his large hands pawing at the scars on his face om thought, but he said nothing.

The rest of the winter passed much the same as before, but Lambert was no longer open and jovial in the evenings. He festered by the fire, muttering darkly about the cold and throwing an occasional scathing remark in Merigold’s direction, only to be chastised by Eskel, Vesemir or both. He drove Ciri just as hard—harder, when Triss wasn’t looking—and picked fault with everything she did.

Coën found her sitting by the fire one evening, picking dejectedly a the scabs on her hands, and staring into the flames. He brought her a blanket and hot mug of juice. “A penny for your thoughts?”

“Half an oren, and we’re talking!”

He thumped her lightly on the shoulder as he sat at her side, and she heaved a sigh. He pressed gently. “Come, a burden shared is a burden halved. Talk to me.”

“I think Lambert hates me, thinks I’m weak.”

“No,” Coën said quickly. “He loves you. Very much.”

Ciri blinked at him in surprise. “But he berates me every day. I disappoint him with everything I do. I need to get it right, I need—“

“Princess, Lambert is harshest to those he loves the most.”

“Well, he must absolutely worship Triss…”

Coën winced. “Ah, yes, no, perhaps there are exceptions, but…”

Ciri sniffled and turned her head away, one of her small, broken hands lifting to her face. He placed an arm around her shoulders and pulled her close. “Come, there’s no need to hide your tears.”

“He’s right, I am weak…”

“No.” Coën lifted her chin so that their eyes met. “When I lost Kaer Seren, I cried for many days, and when I thought there could not possibly be a single tear left, they kept coming. Do you think me weak?”

“No, you’re so strong. You can shoot an apple from the air at a billion miles away! You make Lambert sweat in fencing and you can do ten backflips in a row, and—”

Coën smiled crookedly. “Your emotions aren’t something to be overcome, they are part of you. They make you stronger.”

“I need to get this right, I need to get strong, I need to kill him. I need to avenge them all. I need to—“

“And you will,” Coën said. “But Cintra was not built in a day, and its lioness is still a cub with a lot of growing to do. You must give yourself time. Strength is something that is forged through hardship, through failure. It will come.”

She gave him a watery smile and wiped her nose with her sleeve. “I will get strong, Coën. I’ll listen to everything he teaches me, everything you teach me, Geralt, Eskel… I’ll get strong enough that I can protect people. Save people, you know, just like you do.”

“Yes,” Coën said, smiling. “You will be the greatest of us. Now, drink your juice. It’s past bedtime and Lambert wants me to teach you the crossbow tomorrow.”

“He does?”

“I found him stuffing targets only an hour ago.”

She squealed with excitement and downed her juice. He carried her to bed shortly after, tucking the heavy furs around her narrow frame. But that night sleep wouldn’t reach him; he listened to the others snore as he stared at the ceiling, thinking of orphans, monsters and war.

Come spring, he would head to the front, Coën decided. He could not stand by. He would rise above. He would become more.

#the witcher#witcher lambert#witcher coën#cirilla fiona elen riannon#blood of elves#missing scene#witcher books#witcher games#coën/lambert

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Triss and Lambert mutual hate being canon is such a gift. On the surface they should get along because they’re both the ‘young, naïve, frightened, unable to save Ciri but able to be kind to her in the meantime’ characters but no they are not friends they call each other losers and their beef induces such strong second-hand embarrassment in everyone else that Geralt and Eskel are forced to take responsibility for Lambert for the first and maybe last time ever.

like what if I was Lambert and I was so dedicated to being a weird asshole to this woman who admittedly has atrocious vibes that my brothers were forced to acknowledge that I was their brother just so I’d shut up. wouldn’t that be crazy aha

#netflix also dropped the ball when they got a ginger lambert. like i’m so you could have had a line about#ginger in ginger violence but you did not. pathetic#lambert#triss merigold#blood of elves#the witcher books#double shot

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Finished reading Blood of Elves and the mood of the book is slapstick comedy one second then serious commentary on neutrality and the horrors of war and then back to jokes about diarrhea.

Incredible

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve finally gotten my hands on the witcher books and I’m three chapters into blood of elves and these are my thoughts so far

Geralt is a fucking sweetheart and the show doesn’t understand him

Dandelion and Jaskier are The Same. I want to marry him and also subject him to the ice bucket challenge. He is my silly little bisexual fun time girlboy boyfriend you’re too late sonic he’s forklift certified and he’s never going to die <3

the joey batey cake video is basically how I’m imagining how dandelion behaves as a person. “You’ve just caught me reading. Literature. *drops book on the floor* “we really don’t know how to-” *cabinet door comes off in his hand “FUCKING COCK” *pulling random things out of a cabinet* “lasagna sheets! we’re fucking in business” *bowl falls on the floor* “AW, COCK” “Jamie Oliver you’ve lied to me” “when in doubt—” *starts chugging wine* *mashing cake batter with a cucumber* “WHY WONT YOU DIE” *various cuts to him lying on the floor in stages of despair* “I don’t even like cake”

Timeline? Don’t know her. the show has certainly never met her

I would die and kill for Triss Merigold the show got her wrong too

Eskel <3333

Vesemir I love you

Ciri calls him “uncle vesemir” my found family heart is crying

Yennefer and Dandelion are friends

The show did them all dirty

Himbo witchers do not understand ibuprofen😔 but they drink their respect women juice so I will forgive them

Kaer Morons is a very very fitting term

Lambert <3333

There is more emotional maturity in the first 99 pages of the first book than in the entire netflix series

#the witcher#the witcher books#blood of elves#geralt of rivia#dandelion the witcher#triss merigold#cirilla of cintra#eskel the witcher#lambert the witcher#vesemir the witcher#kaer morons

140 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The sword looks sharp. The beam looks slippery and unstable. And Lambert looks like an idiot" - Triss Merigold, Blood of Elves

#i cut off some of the actual quote because this is funnier#😭#i love triss#i love lambert#lambert lambert what a prick#the witcher lambert#triss merigold#the witcher#the witcher books#witcher books#andrzej sapkowski#blood of elves#the witcher blood of elves#book quotes#books

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

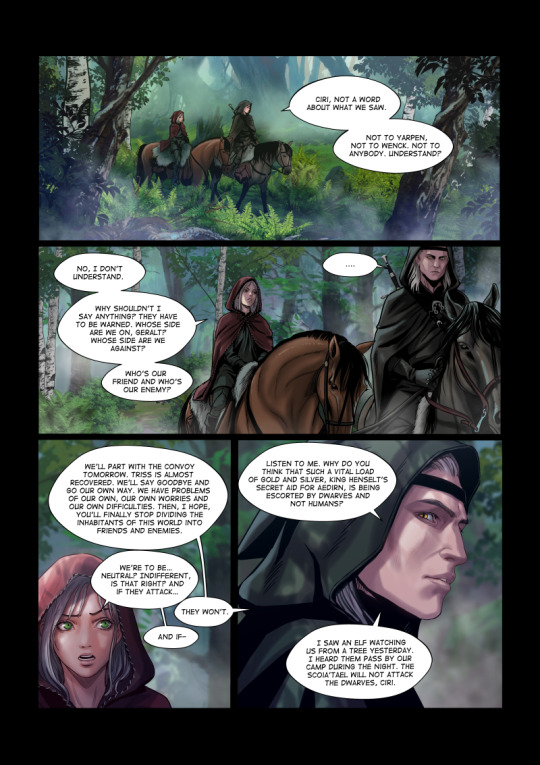

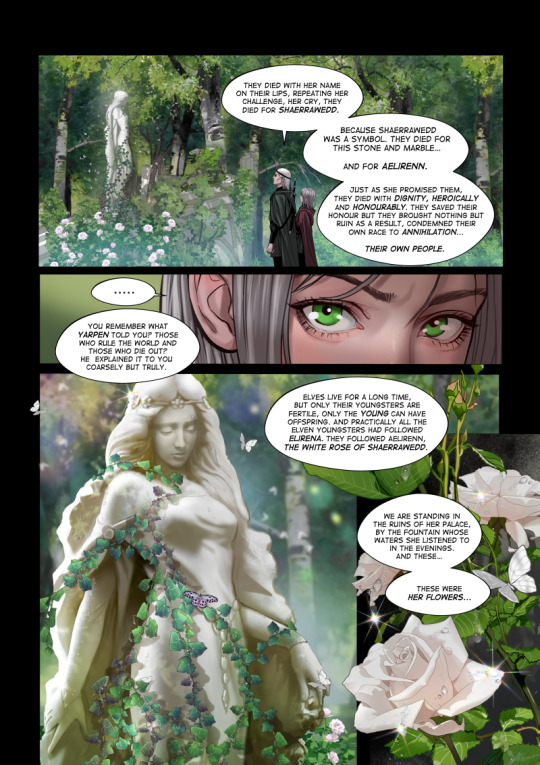

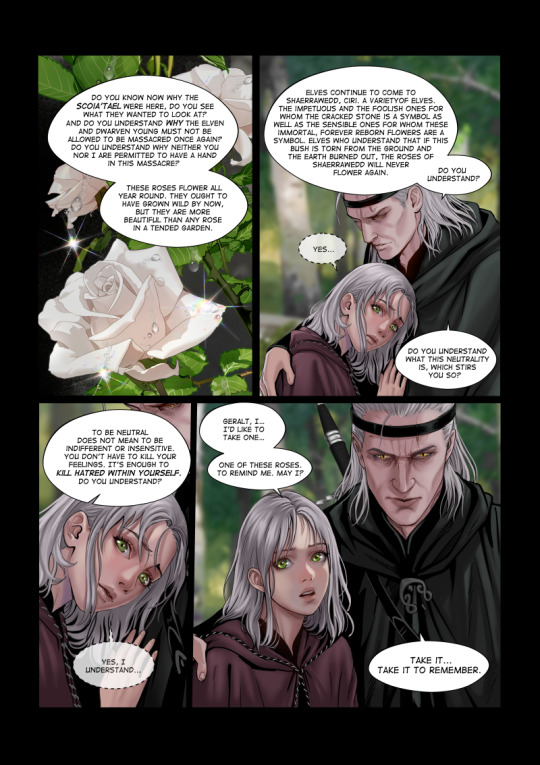

Ciri, The Child of Destiny chapter 16 "Elves and humans"

Part 1 "Shaerrawedd"

Read manga here: https://ciri.the-comic.org

Manga on Russian language : https://ru-ciri.the-comic.org/

Also you can support the project on Patreon : https://www.patreon.com/yagihikaru

Or Boosty : https://boosty.to/hikaruyagi

#the witcher#ciri the child of destiny#ciri#manga#comic#aen seidhe#shaerrawedd#scoia'tael#Aelirenn#blood of elves#andrzej sapkowski

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ciri asking Triss if she can turn her into a boy is so real cause that's also the first thing I'd ask if I ever met a sorcerer.

#girlie got a single period and was like im done with the whole being a girl thing#yeah me too ciri me too#the witcher#blood of elves#the witcher books#transmasc#cirilla fiona elen riannon#triss merigold#transgender

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

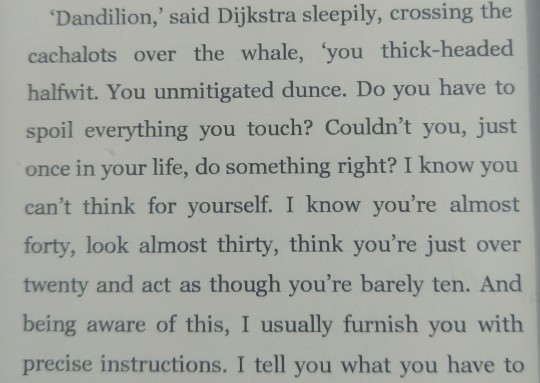

GIRLLLL

Would you look at this INSANE roasting session???

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marriage & Sexual Politics among the Elves

I've been thinking -- we don't know if elven cultures have had a concept of marriage, right? Auberon remembers Shiadhal fondly but he doesn't call her his "wife" iirc, and Lara was supposed to "mate" with another Elder Blood elf, not to marry him.

Musings on the nature of elven desire and sexual politics (and nationalism, apparently); in response to a friend on Discord. As always, long; like your grandmother’s knitting.

I & II - Sapkowski's elves compared to Tolkien's.

III - Elven biology & demographic predicament.

IV - Elven nationalism as tied with their reproductive politics.

V - Wild speculation on elven bonds & pacts.

-----

Would elven cultures in the Witcher have a concept of marriage? Probably. Marriage is a contractual agreement (with excellent PR) designed to achieve a particular end by way of the participant parties agreeing to terms advantageous of that end. As happens, everything in the Witcher ultimately comes down to sex and babies; especially as concerns the elves. Thus, enter: marriage.

Selective breeding, i.e. mating with someone particular as opposed to just anyone, entails at least temporary sexual exclusivity.[1] As a social construct, the primary function of marriage is usually to regulate sexual behaviour, encourage procreation while stipulating the concomitant economic and social responsibilities, and to pre-empt or solve various problems arising from the results of procreation (e.g. care duty, inheritance, kinship loyalties, tax and benefits).[2] So far, marriage fits the purpose.

Of course, marriage can also be – and is – a meaningful ritual between two (childless) lovers. More than that: in a species with a disperse procreation pattern a contractual agreement might also be struck for other reasons (e.g. political, ceremonial, benefactorial, amorous), for a fixed period, and between multiple parties (simultaneously or sequentially). There really is no reason to think nuclear family and perpetual monogamy must be the gold standard for Sapkowski’s elves. However, there might be cause to think that eternal love in the vein of Tolkien might be an ideal the elves in the Witcher’s universe cannot help but fall short of.

I entertain this thought as part of the difference between idealized and gritty fantasy. The difference, on average, seems like it comes down to attachment to a preconceived blueprint. For example, mixed-race marriages produce strange and tragic fates in both authors’ works, but only in Tolkien is the concept of marriage inherently necessary and sacred – and its sacrality affects the physical nature of an entire race – while in Sapkowski every kind of an affair, however mundane or ennobled, is treated seriously as a potential cause for conflict. Tolkien’s ideals feel more top-down and Sapkowski’s grit feels more emergent.

The most extensive documentation and interpretation of marriage between elves as we have come to know them comes from Tolkien. His influence might be felt in Sapkowski’s take on elves, though I dare say mostly by way of inciting a response rather than an imitation.

I

The most widely-known treatise on elven love life out there must be the Laws and Customs among the Eldar. Tolkien’s choices, while impossible to overlook in today’s fantasy canon, diverge from the majority of folklorish matter on fae spirits. He makes elves human again (in the vein of the semi-divine elves of the Anglo-Saxon and the Celtic Aos sí), but then he also makes them the poster children of Catholicism.[3]

For Tolkien, elves were the idealized humans before the Fall. Even after their own brand of Fall (war in paradise: the First Kinslaying, Fëanor’s Oath, and the resulting war for the Silmarils) the Eldar retain a certain idealized nobility in their very nature and bear a fate that makes it seem to mortal yokels as if the Firstborn are especially favoured by the gods. Indeed, perhaps it is the existence of a Creator God – the Great Demiurge – and his Plan in Tolkien’s cosmology that really sets his narrative apart from Sapkowski’s in the first place? Because while there is worship and many deity-like figures, faiths, and organized cults in The Witcher Saga, theism does not really manifest as a certain, fundamental feature of the ultimate order of things. Tolkien’s worldview is primarily providential; all acts of free will ultimately reinforce the Plan. Sapkowski’s take is distinctly suspect of there being any ultimate Plan, and Geralt rejects the notion of a Demiurge’s playground; acts of free will can and do alter things, though as often for the worse as for the better. And yet… Faith is real. Having faith – in a world full of mysteries.

The Witcher is secular in tone but pagan at heart.[4] Wicca is written all over the Saga; the worship of the (Triple) Goddess, Mother Nature and her cycles. Especially in respect to the elves. Indeed, it is hinted in Tower of the Swallow that elves believe themselves to have been created as opposed to having evolved like humans.[5] But we would be looking in vain for their Creator God. Elves are strangers in the worlds they occupy in the Saga, and even should we like to consider them Sapkowski’s equivalent for the Children of Danu (Tuatha Dé Danann), the Dana we encounter in The Edge of the World is either an independent being altogether or… an aspect of a diminished Goddess? As the Witcher elves themselves are in some sense diminished and diminishing; perhaps for this very reason not reluctant to perfect their divinely created selves through genetic engineering; to restore some of their once lost divinity.

Conceptually, The Witcher’s elves have gone through a Fall of their own – from idealized to gritty fantasy. If Tolkien sets an “elven ideal” and makes his Firstborn fit with it, then Sapkowski looks at cause and effect – in biology, material world, and history – and draws conclusions about his elves’ existence and outlook based on that. Not ruling out cause and effect in Tolkien’s imagination, of course, but I feel like the pivot of his work’s tone is somewhere different than Sapkowski’s. Both authors anthropomorphize elves, but Tolkien’s is one of idealization and Sapkowski’s is something of an attempt at “realistic” fantasy. Because depicting the truly alien is, indeed, very hard. Myth and folklore, however, do not aim at establishing unique differences; more often quite the opposite. They toy with the similarities they can draw between you and the “other”; to see which conclusions they can help you reach about yourself. And so, as concerns elven love life, Sapkowski’s elves resemble the creatures in fae folklore more than Tolkien’s. Just as folklore is more often concerned with magical cattle thieving than struggling with cosmological fate (but since The Witcher is still inspired by myths just the same – and myths allow for the grandiose – Sapkowski can involve major cosmological struggles in his work, only indirectly, in the backdrop to the folklorish focus on daily realities and emotions).

I will have to generalize a little bit now, though I do not wish to go on saying silly things about a faith I do not share even while being subconsciously influenced by it.

With some exceptions (e.g. Aredhel & Eöl or Luthien’s kidnapping by Celegorm & Curufin), Tolkien’s elven ideal amounted to a “monogamous, one true love = marriage for life.” On steroids. No casual sex, no premarital sex. No adultery. Intercourse = marriage = a bond of souls. Marriage (and sex) was for begetting children. To the point where Tolkien made his elves biologically unable to be anything but the icons of the aforementioned equation in body and spirit: if they married then they bonded for life and remained monogamously married for the entirety of their existence.

Sapkowski’s elves came out a little more based than that.

II

You might say that in devising the elves’ outlook Sapkowski took sex seriously, and plainly.

The notion that one of longevity’s snags is sex is actually shared by both authors, but Tolkien never really made a point of it. Sapkowski, meanwhile, set the idea under a microscope, letting it seep into the very essence of the Witcher’s plot and themes. Relations between men and women, procreation and familial ties, sexual freedom, bodily autonomy, and sexual politics – all questions of power on several levels – permeate the story. Not on the level of metaphor only either, but very straightforwardly.[6] By contrast, Tolkien ennobled the question of elven sex in footnotes, and then wrote it off.

‘By their very nature, they [elves] are “seldom swayed by the desires of the body” or influenced by lust.’ ‘Even when in after days... [when] many of the Eldar in Middle-Earth became corrupted, and their hearts darkened by the shadow that lies upon Arda, seldom is any tale told of deeds of lust among them.’

- Laws and Customs among the Eldar

This is very much not the case in the Witcher.Lust pretty much capitalizes the elves’ demographic predicament; corrupted hearts or just plain hearts. Sapkowski did not prescribe a normative frame for what elves ought to be like, instead letting circumstances dictate what might make narrative sense. Both Tolkien’s and Sapkowski’s elves have few offspring. But Tolkien’s reasons for it were a little spiritual and a little conventional, whereas Sapkowski tried to be somewhat scientific about it; and definitely unconventionally specific.

“In the begetting, and still more in bearing of children, greater share and strength of their being, in mind and in body, goes forth than in the making of mortal children. For these reasons it came to pass that the Eldar brought forth few children; and also that their time of generation was in their youth or earlier life, unless strange and hard fates befell them.”

- Laws and Customs among the Eldar

Theoretically, the immortal Eldar have an eternity for procreation. Except they simply will not be interested in sex later in life because their author deemed their biological life cycle as such: they marry in their youth (when they are not yet world-weary), have a few children shortly after, and turn asexual as they age because their desires change and they carry on with the pursuit of artistic and cerebral pleasures instead. (Never mind the thought of sex as of a cerebral pleasure.) A scale-model of an idyllic married love idealized in the patriarchal, Christian world.

And just in case (though it is also written that the Eldar can be reincarnated as themselves):

"The Eldar dwell till the Great End unless they be slain or waste in grief (for to both of these deaths are they subject), nor doth eld subdue their strength, except it may be in ten thousand centuries; and dying they are reborn in their children, so that their number diminishes not, nor grows."

- The Book of Lost Tales: Part 1

Tolkien’s elves are like a ready-made set of chess pieces, replenishing itself eternally, until Arda lasts.

Sapkowski’s elves on the other hand are not immortal, and what becomes of them after death is unknown. There is no One World (Arda) to which they are tied; their origin is unknown. They are travellers in a multiverse of realities. They do not have a millennia and reproduction is a real, time-sensitive issue. As is sex in general – an issue. If Tolkien’s elves simply lose interest in sex because they get nerd sniped (and because they are good Catholics), elves in the Witcher experience ordinary sexual frustration. Their longer life-span induces a craving for novelty, which becomes harder and harder to satisfy. Avallac’h’s lecture at Tir na Bea Arainne isn’t, in my opinion, to be taken as evidence of the elves’ biological inability to feel sexual desire after a while. As their history has shown, the opposite is relevant – where has their lust for novelty led them? (A graveyard at Tir na Bea Arainne?)

Sexually frustrated, elven men, just like elven women, begin bedding the newly arriving humans. Because it seems that humans are, well, easy.

‘”You multiply like rabbits.” The dwarf ground his teeth. “You’d do nothing but screw day in day out, without discrimination, with just anyone and anywhere. And it’s enough for your women to just sit on a man’s trousers and it makes their bellies swell…’

But Avallac’h – for self-evident reasons – downplays the role of elven men in the resultant demographic catastrophe. Because as it turns out, elven women, who have a normal ovulation window every 10-20 years with elven men, suddenly become induced ovulators with human men. And as in this gritty fantasy elves and humans are competitors in a race for survival, this gives human genes an advantage.

‘…the honest truth and faithful history of a world where he who shatters the skulls of others most efficiently and swells women’s bellies fastest, reigns.’

- Blood of Elves

III

Biology and demographics, then.

Elven women get the chance to have children only a handful of times in their youth. An average elf lives maybe half a millennia, maybe less. But a male elf of 600+ years is not considered too old to sire offspring, while the upper bound for female elves might arrive around 200-250 years.[7] Depending on when female elves are first considered mature for childbearing, this might result in 20-25 fertility windows (if ovulation every 10 years) or 10-12.5 chances if ovulation occurs every 20 years. The numbers are wholly speculative; we don’t know the age at which pregnancy becomes unlikely to impossible for elven women and we don’t know when elves are considered sexually mature both physically and culturally. However, if we bear in mind that individuals may also experience natural difficulties with conception on top of this diffuse ovulation cycle then elven children are, indeed, very rare.

The elves’ low fertility is compensated by their longevity; in peaceful circumstances their numbers don’t fluctuate drastically. But the circumstances of their existence in Sapkowki’s universe are not, by default, peaceful. Elves in the Witcher do not have their Aman (and even in Aman, if we recall, elf on elf violence still occurred). They exist in competition with other humanoids. Insofar, we must look at elven traits as their potential competitive advantage over likely aggressors: elves are resistant to disease, they are physically very fast and move unheard and unnoticed, they live long lives which enables them to become untouchable in most arts and crafts, and they have a special affinity to magic. Above all, elves have much more time to spread, refine, and maintain their memes. Elven fertility though is a nail in their coffin.[8] Even more so when one of the species they must compete with is able to inter-breed with them; and, to add insult to injury, does so more effectively than elves are able to amongst themselves.

Elven couples are disadvantaged in the numbers game. A human female ovulates approximately 300-450 eggs over the course of her fertile years and the wait between each ovulation is a matter of weeks. The wait for elven women in-between each potential pregnancy is decades. It is possible Sapkowski’s elves might also require a longer recuperation period after each successful pregnancy, mirroring Tolkien. Or, alternatively, they may be more resilient to disease and injury instead and the problems with pregnancies might lie in the conception phase rather than in carrying to term. I would not be surprised, however, if in our “realistic” fantasy at least the Aen Elle had not developed IVF or ovulation induction drugs to level the playing ground somewhat; potentially even independently of the need to compete with humans. We know fertility elixirs exist.

Effectively though, elven women’s reproductive sparseness means that for the majority of the time they do not have to worry about unwanted pregnancies resulting from relationships with elven men. The other side of that coin being that during their fertile phases, the social pressure to reproduce could be pretty immense. Particularly as concerns selective breeding. The period for which a male loses the opportunity to reproduce with a particular female is much longer than for human or mixed couples. This is pretty damning if trying to reproduce magically gifted individuals, and a nightmare for elven nationalists (more about that later). Consequently, absolutely any social construct (e.g. marriage, a pair-bond cementer) that helps ascertain a particular pair ends up conceiving should be very much in demand. Especially with humans added to the equation.

(For the funsies, you can speculate if a recurring period of heightened sexual proclivity in both males and females dovetails with she-elves’ menstrual cycle. Do elves experience something akin to a heat? Which, given how Sapkowski made elven women induced ovulators triggered by the orgasms human males give, I would not even be shocked about. Perhaps it’s his subversive response to Tolkien’s elves having tight control over their biology and being able to choose when they want children to happen. But seriously: ovulation with each powerful orgasm? So… if the orgasm was, let’s say, middling – or there was no orgasm at all; a depressingly realistic prospect – then no dice? An incentive for human men who are not keen on paternity to never-ever learn about the existence of an elven clitoris? I…)

IV

“They want our blood!” howled Baron Vilibert.

“And our land!” someone cried from the crowd of peasants.

“And our women!” chimed in Sheldon Skaggs, with a ferocious glower.

- Blood of Elves

Blood, land and women are often equated, and sexual jealousy features heavily in the elven narrative.[9]

The opening scene of the Blood of Elves under Bleobheris shows the racial and social divisions permeating the Northern Kingdoms, and includes commentary on mixing and women’s bodies. An elven maid in a beautiful toque hat enjoys the attention of human knights, students and goliards; playing into it. Under the gaze of her companions – male elves, who have nothing but antipathy toward the human admirers, proceeding to mate-guard (a tall, fair-haired male elf puts an arm around the beauty with the toque, dispelling any lingering doubts). Sapkowski may have had the folk under Bleobheris poke fun at dwarves for believing everyone desires their women.[10] In the Continent’s recent history though, it was in the war between elves and humans where women’s bodies fast became objects to guard and gatekeep; elves being exceptionally attractive to humans, while humans to elves – a curiosity, a novelty, and an easy (and perhaps useful) lay.

‘Elves, bored by she-elves, court the always-willing human females. Bored she-elves give themselves, out of perverse curiosity, to human males, always full of vigour and verve. And something happens that no one can explain … some hidden hormone, or combination of hormones, became active. She-elves suddenly understand they can, in practice, only have children with humans. So, owing to the she-elves, we didn’t exterminate you when we were still the more powerful race. And later you were more powerful and began to exterminate us. But you still had allies in the she-elves. For they were the advocates of coexistence and cooperation… and they didn’t want to admit that essentially it was about commingling.’

- Tower of the Swallow

There is a lot to unpack here.

Blood, land, women. Technically, the inter-group conflict in the Witcher is an inter-species one, but the surrounding discourse is patently nationalist. Among elves, this is compounded by the worship of Mother Nature. Because in Sapkowski’s Wicca-influenced take, nature is inherently female. Ergo, land is female. And in Baptism of Fire, Regis notes: “Land and territory is what integrates elves.” Adapting to the influx of humans was therefore all the more difficult for elves because their “land and territory” was shared with the invader. Their women were shared.

One of the most common features of fairy mythology is marriage or affair between a human being and a fairy.[11] The one particularly interesting feature of such marriages is that the fairy is almost invariably the female party. Equally, there is almost always either some reluctance involved on the part of the fairy or some suggestion of the use of force by the human; or, on the contrary, it’s the fairy who seduces the human male, which usually ends woefully for him (abduction, death, maiming). The human-elf marriage is strictly conditional (e.g. striking your fairy wife or reproaching her with her origin guarantees she will leave for the Otherworld) and should the wife vanish, she usually tries to take the children with her. The prehistoric theory about the origins of fairy folklore ascribes its existence to reminiscences of earlier inhabitants, crowded out by later immigrants. The colonisers mythologizing the colonized.[12] This fits within the narrative of the Witcher, which makes a point about the inter-group conflict between different waves of migrants being fought both on the battlefield and in bed. [13] In this light, the marriage of a fairy and a human effectively amounts to a narrativization of marriage by capture: the migrants driving the natives into the forests, marshes, and other inhospitable places, where their lifestyle could easily come to be regarded as deteriorating and wild, leading to seeing them as inferior and non-human, at length even as supernatural beings or spirits of nature (i.e. as beings which later, in our folklore, developed into fairies (elves)). The migrants drive the earlier inhabitants off, while breeding with their women and thus inserting themselves into the notional line of inheritance for the conquered land through the creation of common ancestry. A bloodline that inherits the earth it walks on. Something similar is happening between humans and the Aen Seidhe in the Continent. By the 1200s, it is hard to find a human who does not have a dash of Seidhe Ichaer, the blood of elves, flowing through their veins, and pure-blooded Aen Seidhe have become a de facto minority “ethnic group.”

In nationalist discourse, the connection between the land and the people is forged through common ancestry. Blood-ties derive from the land and nourish one’s roots in the land. Women reproduce the nation biologically and under patriarchal relations are also expected to do so ideologically; recreating boundaries between groups.[14] Genes and memes. Women’s role is made to hinge on motherhood, and in national mythologies the identification of the fertile, life-giving land as the nurturing mother and wife is set to mobilize and lend legitimacy to the protection of the land by the male against those who seek to defile it. The option to deal with the invading humans aggressively had been on the table; it’s the elves’ appreciation for new life that had stayed their hand. Sexual jealousy features so prominently in the elven narrative then because the conflict they are immersed in is not only an inter-species one over the proverbial life-giving territory. It is also a conflict between elven men and women.

How do elven women position in elven societies then, politically and personally? Nationalism entails the protection and re-forging of group affiliations through ensuring similarity in its members’ biological and cultural markers, but the power relations of reproduction hinge on the nature of gender politics. In contrast to humans, elves are ostensibly egalitarian. Elven children, for example, are brought up without reinforcing arbitrary distinctions between male and female skills and practices. Insofar as elves, unlike humans, don’t seek to dominate nature (that is “the female”) – and should this mindset carry over to their social relations – the status of elven women might be greater still; also considering the commensurately more precarious situation with reproduction. The ball is in the women’s court, though so, apparently, are the stakes. After all, it seems elven women, at the time when elves still held power over humans, were in a position to steer history and choose freely whether to procreate with them. They decided in favour of it – almost as a matter of policy? – because of their love of children. And if it was a calculated decision, did elven men – who also lay with human women – see this then as either a fad or a potential?

Going down the eugenics rabbit hole for a minute: theoretically, in a controlled mixing environment, inter-breeding with particular humans could have worked out beneficially for the elves by increasing their numbers and by introducing useful mutations into their gene pool. It’s not clear though if heterosis in any form would have really occurred as a result. But if selective breeding is, indeed, widespread among them then I would not rule out at least debate among their elite. (By the way, might it be that only half-elves born of elven women would have been admitted among pure-blooded elves? (With the one notable exception being Riannon.) Perhaps due to the perception of a mother being more tied to the child and more integrated into her own people’s culture, traditions, and values?)

As it turned out, cross-breeding did not encourage peaceful relations. And insofar as sex can be a political tool (just as sexual violence a weapon of war), the choices of elven women went from being a subject of cultural reflection and appreciation to an active political liability. If previously all motherhood would have been revered for its own sake, now not all motherhood would have been perceived to lead to positive outcomes. Especially not for the group, and especially not in the eyes of elven ultranationalists. If the symbolic elevation of (nature as) “the female” thanks to her ability to bring forth new life was a distinct and possibly positive feature of elven societies beforehand, now – in this new world of competition with another species – the placement of procreation at the heart of the turns of elven history rather shifts the narrative toward the sexist objectification we are used to seeing in human cultures. Except on the whole and on average, elves remain an egalitarian species, and the overall value of life for its own sake – of hope and of new beginnings – persists.

It begs the question then if the changes in ideology that elven societies went through were wholly negative to elven women in a similar vein as they are usually negative to humans. An aureole of semi-religious significance does not necessarily result in a gilded existence – the Saga hammers this home with Ciri’s entire life – but motherhood seems to be a sought-after experience among elven women regardless. Their faces are noted to reflect boundless odium and surprise at Ciri’s disgust over the prospect of pregnancy and motherhood.[15] The gendering particulars of elven nationalism remain up for debate then: in which direction is their script askew – patriarchal, matriarchal, or some secret third thing? To what extent did it shift from one perspective toward another? If the objectification of the female body post-humans intensified commensurately with the elves’ increased procreative predicament, then an elven maid’s choice, while remaining still a choice, might have become culturally encouraged, traditionally supported, strongly recommended. But still a choice.

V

Let’s leave humans out of the equation. Let’s speculate.

There are three things Sapkowski’s elves value above all else, as far as I can tell: beauty, novelty, and the preservation of life in its particularity. The number of truly novel experiences decreases fast and nothing truly lasts in the material world. Worse, the virgin feeling of any experience loses its shine in memory. To be perpetually nostalgic then for the mental state reminiscent of a newborn for whom every new thing encountered seems permanent and never-ending – such seems the fate of elves who have no guarantees of a paradise of their own or of eternal life.

Insofar as putting a label on it goes, I suspect elven relationships are quite intricate but precisely defined per the time they intend for them to last, even if they may seem messy and opaque to the human eye. The majority of folklore depicts fae spirits as sexually liberal[16]. A mix of serial monogamy intersected with polyamory? Patch-work families and age differences also seem all but assured. Neither would I rule out the ideal of eternal, monogamous love, which rings precisely of the kind of experience that remains elusive, unreachable, and yet, desirable for these a-Tolkinesque elves. They have the time, and love has many faces. Since novelty and the particularity of experiences matters though, the general population may be tempted to maximize for variety, and their social structure and socialisation may well have had to develop to accommodate the different bonding-configurations desire and time can birth.

There is a catch, though – the fine print.

A prolonged lifespan implies every stage of elven life and their every decision – every action and non-action – will stretch in its impact; on themselves, on their society, on history. Either great foresight or a plethora of little balancing devices seem necessary in order to guard against civilizational, interpersonal, and individual breakdown. Ida Emean would not describe elven race’s strength as arising out of excessive rationality, and truly, an oath, a promise or an action that is born as a result of irrational desire, momentary impulse, or chance opportunity can be a weighty and dangerous thing for an elf. Consequently, negotiations of terms are to be expected whenever a contract is to be entered into; both before and after the bond has come into effect. But a contract is in the interests of everyone involved. Reliance on formal agreements and debts is likely as normalised as being shockingly straightforward in delineating one’s wants and expectations. Even in sensitive matters that benefit from illusions, such as love. The flipside of the coin – the catch – is that elves are incentivized to allow for and find ambiguity in the wording of their own terms, and, provided they are not ideal beings, are wont to try and re-define the precise manner of the satisfaction of the terms in their contracts.

Marriage is, first and foremost, a bargain.

Depending on the specifics of the relationship, the length and nature of a marriage may differ wildly. The notion of the immutability of sacred vows may not be quite as idealized among ordinary elves as it is among humans; in fact, it might be quite a frightening concept. If we allow for the fallen nature of the Witcher’s elves – from an idealized to a gritty depiction – then marriage as an eternal commitment is much like an impossible bind; in a universe where nothing is by virtue of design guaranteed to last, where the notion of fate itself is dubious. Moreover, not all love or lust necessitates marriage; not even real romantic love. If marriage is first and foremost a bargain, a social construct for (temporarily) regulating sexual behaviour, and a social safeguard of procreation, then I imagine elves may be quite a bit less deluded about its function; which is practical first and idealized second. Unless you belong among elven mystics (though I don’t know if they too get tax benefits).

Generally though, the ball is in an elf-maid’s court. If children are the aim, and unless subject to a selective breeding programme, she can be picky in who to mate with as her time-sensitive choices carry that much more weight. It’s up to the groom to be up to par, really. Being up to par, however, can mean many things. Is love part of the bargain? Moreover, is it “lasting” love that is being promised or sought, or a seasonal one, or something entirely, wonderfully specific and different? Tricky. No elven maid would enter into a marriage contract without first considering the terms carefully; in order not to over-promise or to be extorted of more than was seemingly agreed upon. And should true, lasting love be baked into the ideal of marriage then there would be plenty to be wary of as The Witcher’s elves maintain only the veneer of the Tolkinesque ideal and not a nature that would necessarily be able to live up to the idealization. To be tricked into performing the impossible – whether by your own feelings or by another’s – can be dire.

I think marriage is a very real concept among elves, but also a quite de-mystified one, except for a few special cases.

-----

[1] Naturally this begs the question if all elves (amongst themselves) practice selective breeding, or only some? We don’t know, and the topic is a little too broad to broach here, but we do know that at least the elven elite among the Aen Elle does selectively breed the magically gifted (who also happen to belong to the upper strata of their society).

[2] An interesting question in its own right would be about the nature of inheritance laws in a species that lives half a millennia a piece.

[3] The incorporation of fae spirits and their associated folklore into Christian cosmology in sub-Roman Britain is a topic of ideologically-motivated revisionism in its own right.

[4] In an interview to Stanisław Bereś (Historia i fantastyka), AS mentions his worldview is pagan: ‘Yes. Even the term "agnostic" is too weak for me. My worldview is not agnostic, atheistic or secular. This is pure paganism. I really am a pagan in the textbook sense of the word.’

[5] AS mentions creationist elves in The Manuscript.

[6] One of the metaphors being: sex -> rebirth -> hope (hopefully). Or: Grail = Woman; leading to hopeful new beginnings or the opposite, death and destruction (either by not “realising its hope” or by giving new life to what will invariably have a high chance of causing more evil). As I said, Wicca is everywhere.

[7] This is probably a generous estimate. We don’t really know the details about elven life span.

[8] No wonder elves are hell-bent on controlling Ard Gaeth; if they cannot outcompete their co-habitants or negotiate favorably for themselves, they can at least find a new universe to thrive in.

[9] In other examples, the burning of Birka – the later Jealousy – occurred in consequence of a human girl not reciprocating an elf’s feelings and, as the people say, mocking his feelings on top of it by sleeping around. Or in yet another pivotal occasion, the semi-mythical love triangle between Crevan, Lara, and Cragen gives the Witcher’s plot one of its major catalysts.

[10] ‘Several people started to laugh – as quietly and furtively as they could. Even though the idea that anyone other than another dwarf would desire one of the exceptionally unattractive dwarf-women was highly amusing, it was not a safe subject for teasing or jests… the dwarves, for some unknown reason, were entirely convinced that the rest of the world was lecherously lying in wait for their wives and daughters, and were extremely touchy about it.’ – Blood of Elves

[11] H. N. Gibson (1955) The Human-Fairy Marriage, Folklore, 66:3, pp. 357-360

[12] In case of the Witcher, the colonized Aen Seidhe were obviously technologically more advanced than the colonizing humans. A case is to be made then that infantilization plays an important part in the narrative the colonizers create against the colonized (equally to narratives emphasizing the elves’ cruelty or Otherness).

[13] It is noteworthy though, that Sapkowski’s elves are both the colonizers and the colonized, which is true to real life in many places and times; even if in particular AS drew on the several waves of migration that saw various peoples landing in Ireland and the British Isles, fighting and driving out the earlier inhabitants on each occasion. Aen Elle’s position to their human servants is diametrically opposite to that of humans’ to Aen Seidhe; possibly also in terms of reproducing with them. All servants Ciri saw at Tir na Lia were female.

[14] Yuval-Davis, N. 1988.

[15] To some extent it begs the question, do elven women on average even mind their politically and symbolically-vested position, deriving from their unique ability to create life? In ancient Celtic societies, motherhood and nurturing were considered sacred feminine qualities. There is only a small step from holding this view kindly to holding it as espoused in various patriarchal, traditionalist and nationalist discourses, though.

[16] While depicted as sexually liberal among their own, they are notably stringent with the humans they elope with.

#wiedźmin#the witcher#aen seidhe#aen elle#elves#andrzej sapkowski#j.r.r. tolkien#the witcher lore#blood of elves#baptism of fire#tower of the swallow#lady of the lake#the witcher books#auberon muircetach#lara dorren#avallac'h#wicca#nationalism#reproductive politics#fae#fairies

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝘚𝘩𝘦 𝘧𝘦𝘭𝘭 𝘢𝘴𝘭𝘦𝘦𝘱 𝘩𝘰𝘭𝘥𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘵𝘪𝘨𝘩𝘵 𝘵𝘰 𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘩𝘢𝘯𝘥.

~ Blood of Elves, Chapter 1.

The first scene of Ciri waking up from a nightmare with Geralt right beside her, while still on the path to Kaer Morhen.

#the witcher#geralt of rivia#witcher fan art#cirilla of cintra#the witcher books#the witcher 3#blood of elves#ciri#archive of the continent

68 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Witcher: Aen Hanse members

↳ [6/6] Geralt of Rivia, the witcher, also known as Gwynbleidd (or White Wolf) and by many other aliases

To be neutral does not mean to be indifferent or insensitive. You don't have to kill your feelings. It's enough to kill hatred within yourself.

— "Blood of Elves" by Andrzej Sapkowski

#wiedźmin#the witcher saga#aesthetic#geralt of rivia#geralt#aen hanse#i never really wanted to do geralt's personal moodboard (for many reasons)#but he is still an integral part of the hanza#and this aen hanse series cannot be completed without him#hanza#the witcher books#witcher#blood of elves#my edit

33 notes

·

View notes