#brout

Text

remembering my 30k note post i made in 4 seconds about mens tits and some of the weird tags i've gotten on it. ppl on here will nitpick the weirdest shit. i used the word "tummy" instead of "belly" bc i hate how the word belly sounds. not for any deeper reason and not bc i'm too shy to say it but i literally just do not like how it sounds in my head. someone on that post called me a coward for saying tummy instead of belly. they are synonyms?

#ppl tagged that post as the worst men ever#also thinking abt the one person who brout up ter/fs out of nowhere on a post about men. like ok. thanks for that. really makes me feel safe

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

ÊTRE UNE FEMME À VÉLO

youtube

"T'es conne ou allemande ?" Je meurs.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Émilie Brout & Maxime Marion, IDLE (acts α and β), 2023. 4K video, 25 min

1 note

·

View note

Text

Oui, oui, je sais, personne n'aime lire du smut en français, mais essayez quand même pour la science

#débat secondaire que pensez vous du mot “lèvres”. pour une fois je trouve ça plus évocateur et charmant que l'anglais si scientifique#upthebaguette#poll#pardon my french#french side of tumblr

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

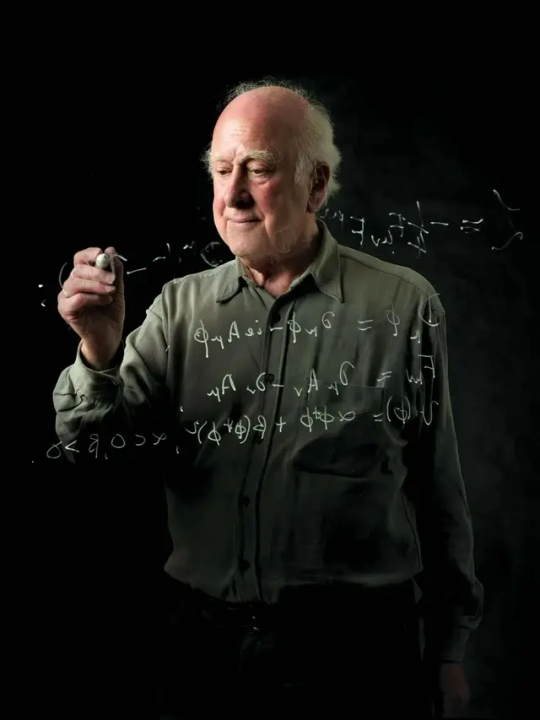

In 1964 the theoretical physicist Peter Higgs, who has died aged 94, suggested that the universe contains an all-pervading essence that can be manifested in the form of particles. This idea inspired governments to spend billions to find what became known as Higgs bosons.

The so-called “Higgs mechanism” controls the rate of thermonuclear fusion that powers the sun, but for which this engine of the solar system would have expired long before evolution had time to work its miracles on earth. The structure of atoms and matter and, arguably, existence itself are all suspected to arise as a result of the mechanism, whose veracity was proved with the experimental discovery of the Higgs boson in 2012.

The Nobel laureate physicist Leon Lederman infamously described the boson as “the God particle”. Higgs, an atheist, found this inappropriate and misleading, but the name stuck and helped bring fame to the idea, and to Higgs. He in turn became a Nobel prizewinner in 2013.

It was at Edinburgh University, as a young lecturer in mathematical physics in the early 1960s, that Higgs became interested in the profound and tantalising ways in which properties – mathematical symmetries – in the equations describing fundamental laws can be hidden in the structures that arise.

For example, in space, unaffected by the earth’s gravity, a droplet of water looks the same in all directions: it is spherically symmetric, in agreement with the symmetry implied by the underlying mathematical equations describing the behaviour of water molecules. Yet when water freezes, the resulting snowflake takes up a different symmetry – its shape only appearing the same when rotated through multiples of 60 degrees – even though the underlying equations remain the same.

The Japanese-American physicist Yoichiro Nambu first inspired interest in this phenomenon, known as spontaneous symmetry breaking, in 1960.

Inspired by Nambu’s work, in 1964 Higgs’s own theory emerged with its explanation of how equations that call for massless particles (such as the quantum theory of the electromagnetic field, which leads to the massless photon) can, via the so-called Higgs mechanism, give rise to particles with a mass.

This idea would later be at the root of Gerardus ’t Hooft’s proof in 1971 that unification of the electromagnetic force and the weak force, responsible for radioactivity, where a massive “W” particle plays the analogous role to the massless photon, is viable. The subsequent discovery of the W in 1983 gained Nobel prizes, both for the experiment and for theorists who had foreseen this. Underlying this success was the so-called Higgs mechanism, which controlled the mathematics in this explanation of the weak force.

When Nambu won the Nobel prize in 2008, it began to seem likely that the way was being prepared for Higgs’s eventual recognition.

A problem though, as Higgs was always the first to stress, was that he had not been alone in discovering the possibility of mass “spontaneously” appearing. Similar ideas had already been articulated: by the condensed matter physicist Philip Anderson, though in a more restricted way, and by Robert Brout and François Englert in Belgium, who beat Higgs into print by a few weeks. A former colleague of Higgs at Imperial College, Tom Kibble, and two colleagues were to write a paper along similar lines weeks later.

Where Higgs had justifiable claims to uniqueness was in the boson. He drew attention to the fact that in certain circumstances spontaneously broken symmetry implied that a massive particle should appear, whose affinity for interacting with other particles would be in proportion to their masses.

It would be discovery of this particle that could give experimental verification that the theory is indeed a description of nature. Although even this boson was arguably implicit in other work, it was Higgs who articulated most sharply its implications in particle physics.

The eponymous “Higgs boson” became the standard-bearer for the Large Hadron Collider. In the early 1990s the science minister William Waldegrave issued his challenge: explain the Higgs boson on a sheet of paper and help me to convince the government to fund this.

Among the winners, the most famous was the analogy, by David Miller of University College London, of Margaret Thatcher – a massive particle – wandering through a cocktail party at the Tory conference and gathering hangers-on as she moved. Higgs, whose politics were diametrically opposite to hers, expressed himself as being “very comfortable” with the description.

He was always uncomfortable as a celebrity. When Cern – the European Organisation for Nuclear Research – prepared to switch on the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) in 2008, the media promoted it as a quest for the Higgs boson.

Higgs felt that Cern was misguided to talk up “the” boson – he was always the first to stress that others had had much the same idea and that naming it after him was unfair. He once modestly described the detection of the boson as “tying up loose ends” and regarded the main excitement of the LHC as its potential to reveal the secrets of dark matter and other kinds of new physics.

Nonetheless, in July 2012, Cern announced the discovery of a particle “with Higgs-like properties”. Media frenzy grew, and Higgs bravely accepted his fate as a centre of attention.

Although most physicists were sure that the eponymous boson had been discovered, several months’ more study would be needed before complete confirmation could be assured: the Nobel prize for 2012 went elsewhere. By 2013 the evidence was compelling; there was a general expectation that 2013 would be the year.

By this stage, 49 years had elapsed since Higgs had written his first paper on the subject. In a final, nailbiting twist, the announcement of his long-awaited success was delayed by an hour as the Nobel committee struggled to reach the famously reclusive scientist. Aware of the media attention he was likely to get, Higgs had decided to be “somewhere else” when the announcement was made, and told colleagues that he planned to take a holiday in the north-west highlands of Scotland.

As the date approached, however, he realised that this was not a good plan for that time of the year, so he decided to stay at home and be somewhere else at the right time. At around 11am on 8 October, he left home and by noon, when the announcement should have been made, he was in Leith, by the shore, in a bar called the Vintage, which Higgs famously attested sold both food and “rather good beers”.

Thus with Higgs incommunicado (he largely avoided using mobile phones or the internet), after more than an hour of unsuccessful attempts to reach him, the Swedish Academy decided to make the public announcement anyway. The ironic result was that by 2pm, the news that Peter Higgs and Englert, of the Université Libre de Bruxelles, were the winners of the Nobel prize for physics was known to the world, but not to Higgs himself. (Englert’s colleague Brout had died in 2011, and was unable to be included as Nobel prizes are not awarded posthumously.)

Higgs later recalled how, “after a suitable interval”, but still ignorant of the news, he had made his way home from lunch. However, he delayed further by visiting an art exhibition, as “it seemed too early to get home, where reporters would probably be gathered”.

At about three o’clock he was walking along Heriot Row, heading for his flat in the next street, when a car pulled up near Queen Street Gardens. A lady got out “in a very excited state” and told Higgs: “My daughter’s just phoned from London and told me about the award.” To which Higgs replied: “What award?” As he explained, he was joking, but that is when his expectations were confirmed.

His plan had been a success, as, “I managed to get in my front door with no more damage than one photographer lying in wait.” A little more than a decade later, the main focus of the LHC has been to produce large numbers of Higgs bosons in order to understand the nature of the omnipresent essence that they form.

During the coronavirus lockdown I talked with him for hours on the phone at weekends in the course of researching the biography Elusive: How Peter Higgs Solved the Mystery of Mass (2022). When asked to summarise his perspective on public reaction to the boson he said: “It ruined my life.” To know nature through mathematics, to see your theory confirmed, to win the plaudits of peers and win a Nobel prize, how could this equate with ruin? He explained: “My relatively peaceful existence was ending. I dont enjoy this sort of publicity. My style is to work in isolation, and occasionally have a bright idea.”

Higgs spent more than half a century as a theoretical physicist at Edinburgh University. Perhaps because of this, he was described in many media reports as a “Scottish physicist”, whereas in fact he was born in Newcastle, of English parents, Thomas Ware Higgs and Gertrude Maud (nee Coghill).

His father was a sound engineer with the BBC, and the family moved almost immediately to Birmingham, where Peter spent his first 11 years. In 1941, with the second world war intensifying, the BBC decided that Birmingham was too dangerous, and its operations were transferred to Bristol. The Higgs family duly moved there, with the intention of avoiding aerial bombardment, but the following weekend the centre of Bristol was heavily bombed.

In Bristol, Higgs attended Cotham grammar school, where a famous former pupil had been the Nobel physicist Paul Dirac. Dirac’s name was prominent on the honours board. Higgs followed him, but initially in mathematics rather than physics. Higgs’s father had a collection of maths books, which inspired Peter and enabled him to be become far ahead of the class. His interest in physics was sparked in 1946, upon hearing the Bristol physicists, later Nobel laureates, Cecil Powell and Nevill Mott describing the background to the atomic bomb programme. Although this helped determine his career, Higgs himself later became a member of CND.

At King’s College London he studied theoretical physics, going on to gain his PhD in 1954. He was working on molecular physics, applying ideas of symmetry to molecular structure. His interests moved towards particle physics, although his office was on the same corridor as those of Rosalind Franklin and Maurice Wilkins, two of the co-discoverers of the structure of DNA, though his own work had no immediate link to their programme.

He won research fellowships, first at the University of Edinburgh (1954-56), then in London at University College (1956–57), and at Imperial College(1957–58). He was appointed lecturer in mathematics at University College London in 1958, and then moved to the University of Edinburgh in 1960, where he spent the rest of his research career. Initially lecturer in mathematical physics, in 1970 he was appointed reader and, in 1980, professor of theoretical physics. He was elected Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1974, and FRS in 1983.

He met his future wife, the linguist Jody Williamson, at a CND meeting in 1960. They married in 1963, and had two sons, Christopher and Jonathan. Although they separated, they remained friends until her death in 2008.

Higgs won several awards in addition to the 2013 Nobel prize. In addition to numerous honorary degrees, these included the 1997 Dirac medal and prize from the Institute of Physics, the 2004 Wolf prize in physics, the Sakurai prize of the American Physical Society in 2010, and the Edinburgh medal in 2013. That year he was also appointed Companion of Honour, and two years later he won the Copley medal of the Royal Society, the world’s oldest scientific prize.

His sons survive him.

🔔 Peter Ware Higgs, theoretical physicist, born 29 May 1929; died 8 April 2024

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Canard Colvert - Pour se nourrir, il plonge tête la première dans l'eau et fait basculer son corps à l'aide de sa queue. Il trouve sous la surface de l'eau des petits poissons, petits invertébrés, ainsi que des plantes aquatiques sous forme de graines, racines ou pousses. Lorsque la nourriture se raréfie dans l'eau il broute alors le sol.

Lieu : Parc Charles Bertin, Douai

#jardin public#public garden#canard#duck#oiseau#bird#animaux#animals#animaux sauvages#wild animals#canard colvert#mallard#mallard duck

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Richard's charge at Bosworth, according to Edward Hall's chronicle.

...And being inflamed with ire and vexed with outragious malice, he pit his spurres to his horse and rose out of the dyde of y range of his battaile, leyung auntgardes fighting and like a hungry lion ran with spere in rest towards him.

Therle of Richmonde perceyued wel the king furiusly commying towards him, and by cause the hole hope of his welth and purpose was to be determined by battaill, he gladly proferred to encoutre with him body to body and man to man.

Kyng Rychard set on so sharpely at thefirst Brout y he ouerthew therles standarde, and slew Sir William Brandon, his standarde bearer(which was father to Sir Charles Brandon by kynge Henry VIII. created duke of Suffolke) and marched hand to hand w sir Ihon Cheinye, a man of great force and strenght which would haue resisted him, and the said Ihon was by him manfully ouerthrowen, and so he making open passage by dent of swerde as he went foward,

therle of Richmond with stode his violence and kept him at the swerdes poincte without auantage longer than his companions other thought or iudged, which beying almost in dispaire of victorie, were sodainly recomforted by Sir William Stanley, whiche came to succours with III. thousand tall men, at which very instant kyge Richardes men were dryuen back and fledde, and he himself manfully fyghtynge in the mydell of his enemies was slayne and brought to his death as he worthely had deserued.

Edward Hall's Chronicle was first published in 1548, admitably many decades after Bosworth(1485). But interestingly, not just Vergil describes Henry VII withstanding brunt of Richard's charge for at least a while...

Not all details are same as in my previous post about battle of Bosworth(because i tried to find more contemporary sources) but it is very interesting to hear what more common people(not noblemen and courtiers) thought happened in Bosworth.

If anybody would wish to read in Hall's chronicle, it's online!

And here is the link:

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

me: hey yknow i should try to at least finish the art project that we’re doing in class

me: ……..bean brout

@chillibeanos :3c

4 notes

·

View notes

Quote

「Higgsヒッグズ粒子」に名前を与え2013年にノーベル物理学賞を受賞した英国人物理学者Peter Higgsピーター・ヒッグズが、2024年4月8日に、エディンバラで亡くなりました。

Le Mondeル・モンド紙も、2024年4月11日付けで第25面に追悼記事を出しています。

業績も世界的に有名ですが、F爺の注意を惹いたことが二つあります。

[1] 1964年に、Peter Higgs (1929~2024)よりも少し早く、同じ理論をベルギー人のRobert Brout (1928~2011)とFrançois Englertも独自に打ち立てていた。従って、「ヒッグズのボース粒子」は、「Brout-Englert-Higgsのボース粒子」と名付けるべきものであった。François EnglertはPeter Higgsと同時にノーベル賞を受賞したが、Robert Broutは、その前に死去していたため、栄誉に与(あずか)ることは叶わなかった。

[2] Peter Higgsピーター・ヒッグズは、存命中、テレビを見ず、コンピューターを使わず、携帯電話も持たなかった。本人宛にメールの着信したことが分ると、手紙を書いて郵便で返信していた。

学問研究に関して偉人であるだけでなく、なかなか独特の人物だったのですね。「情報弱者」でも大科学者であり得る実例です。

物理学者Peter Higgsピーター・ヒッグズは、存命中、コンピューターを使わず、携帯電話も持たず、メールの送信もしなかった - F爺・小島剛一のブログ

3 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Self-regulating in the face of a trigger sound or visual stimulus is made extraordinarily challenging by the almost-immediate neurophysiologic response that causes a person to feel out of control. Coping with misophonia is not about willpower or choice. Instead, coping with misophonia is about developing better self-regulatino. Willpower is not the antidote to misophonic reactivity; self-regulation is.

An Adult's Guide to Misophonia by Dr. Jennifer Jo Brout

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Au moins maintenant quand au lieu de gueuler dans sa voiture comme un con, il gueule sur un vélo et il fait face !

youtube

1 note

·

View note

Note

Mam.a want mi tel yu they brout snaks

-erina

no wana ea.t dem

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"../...Tu le sais je suis né d'un père et d'une mère humains. Mes soeurs, pas plus qu'eux, n'ont quatre pattes, une tête bête, ni des yeux rouges. Mes enfants non plus. De mon côté, j'ai aussi l'apparence d'un être humain, un peu sombre, peut-être. J'aime l'herbe, mais ne la broute pas, et j'habite un studio donnant sur les arbres à Montmartre, au pied du Sacré-Coeur. C'est là où je reprends conscience de ma vie. Il y a certainement eu en elle des choses qui m'ont totalement échappé...car je ne les cherchais pas.

Ces phrases que je transcris sont les premières d'un texte intitulé le mouton noir mélancolique. Près de deux cents pages rédigées à la main d'une écriture soignée, corrigées et annotées jusqu'à la fin. Sur la chemise bleue qui les renferme, mon père a écrit "à romancer". Ce texte, il le destinait à d'autres. Ma soeur et moi pour commencer. Il a passé les derniers mois de sa vie à l'écrire, dans le petit appartement que nous lui avions aménagé: une pièce blanche et claire, au rez-de-chaussée d'un immeuble moderne précédée d'un couloir en coude , sur lequel ouvraient une cuisine, une salle de bain, une penderie, et dont la paroi du fond était entièrement occupée par une baie vitrée qui donnait sur voie plantée d'arbres. Il y avait dans ce lieu comme dans certaines chambres d'hôtel, quelque chose d'impersonnel et de rassurant. Dès que nous l'avons vu nous avons su qu'il y serait bien, qu'il y échapperait à la peur. Nous y avons installé les meubles et les bibelots rescapés de la vente à Drouot, une grande bibliothèque où tenaient ses livres de droit et les cartons remplis de ses cahiers, un divan et un bureau, des tapis usés, une console Empire, des tableaux de mon grand-père, une photographie en noir et blanc de la Malouinère de Saint-Méloir-des Ondes: les reliques d'une dynastie de notables qui recomposeraient autour de lui le décor d'une vie respectable, lente et feutrée. Les psychiatres l'ont autorisé à quitter la clinique où depuis un an il était enfermé. Il allait pouvoir recommencer à vivre. C'est dans cette chambre qu'il est mort, neuf mois après.Tout de suite, il s'est approprié cette nouvelle scène. Et durant ces neuf mois, le temps d'une gestation, il s'est inventé un nouveau rôle. Il avait été le Malade, il serait le Médecin; il avait été le Fou, il serait le Sage. Il s'est remis à lire; pas de romans mais des essais, saint Thomas et Hannah Arendt, Jung et Plotin ( ce sont les névrosés qui lisent des romans m'avait dit un psychiatre rencontré peu après sa mort, les psychotiques préfèrent la poésie et la philosophie, ils creusent plus loin dans le réel). Lui-même, dans sa chambre blanche, il se rêvait penseur, moine-savant. il était Abélard isolé et banni, ou l'un de ces mélancoliques de la Renaissance assis à son écritoire, entouré de livres, de globes, de vanités et de miroirs ternis. Ce texte qu'il écrivait, n'est pas l'histoire de sa vie mais celle de sa maladie. J'ignore qui est ce "Tu" auquel il s'adresse d'emblée, ce tu qui "sait"; un autre malade, compagnon d'armes, frère d'âme? Celui que la maladie avait, en lui, laissé invaincu, impassible? Ce "Procureur implacable" dont il dit que, sa vie entière, il l'a redouté et qu'il espérait fléchir enfin? Ou bien encore une femme, une compagne rêvée comme celle que s'inventent les enfants tristes et les adolescents solitaires, une Héloïse, dit-il: Que n'ai-je une Héloïse à qui écrire parfois dans ma solitude?" ../..."

Citation et extrait de "Personne" un roman de Gwenaëlle Aubry-Editions Mercure de France-

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bruno Le Mohair n’a pas froid aux yeux, nanti de son col roulé de pensée complexe, il broute l’herbe sur le dos du français moyen cognitivement incapable de comprendre les enjeux énergétiques… Hume est dépassé, l’homme est un mouton pour l’homme.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Newsies as weird thing i’ve said or heard part one

Jack, so i have a crush on a spoiled brat

Mush, it is 1am you can’t ask for toilet paper

Spot to race,your the one who brout it with you so you have to carry it

Albert to wezel, go away no one likes you

2 notes

·

View notes