#but at the same time when it comes to my identity as being salvadoran it's just me myself and i.

Text

*rocking in the corner of the room* i am comfortable in my identity people respect my identity i am wanted i fit in with others who share my identity i am not an outcast nor am i an anomaly

#jelly.txt#i'm doing BAD. i hate being mixed so much man#this wouldn't be nearly as bad if parents would've actually raised me but here we are!!!! i hate this this sucks i want to be adopted but#i hate the adoption terms. you take one look at me and you automatically know i'm hispanic but there's nobody else like me in this family#everybody in this family is white!! and at family gatherings before they have made it abundantly clear they don't want me there!!#but i have nowhere else to go!! i have no family who will ever understand me!! and this family said they'll only adopt me#IF i change my last name to theirs. and i said no so they're being stubborn and said they won't adopt me until i agree#and it's stressing me out because i don't wanna give up my last name. these are the last ties i have to my heritage#and they told me that's exactly why they want me to change my last name cause they want me to not have ties to my heritage#not only that but i also found out the reason why my records are so wonky and have different race/ethnicities on each file#for me is because my mom was ashamed of it and so she purposefully put in the wrong information for me at first#so now that's got me thinking about. if i had to fill out a forum for myself what would i put#because technically i'm mixed but i've been shunned from the white ppl of my family and i feel pride in being salvadoran#but at the same time when it comes to my identity as being salvadoran it's just me myself and i.#my family didn't even want to throw me a quince. because i'm the only hispanic person in the family so they saw no point#i just feel like theres so so many cultural experiences i've missed out on cause i'm all alone here. to the point where it's like#do i even have the right to identify as salvadoran? when documents ask for my race who will i be betraying with my answer.#because. i feel like the identity that fits me most on an entirely racial level would be indigenous salvadoran. it feels good to me#i've never liked the labels hispanic or latino because of the colonial aspect of it. but then there's the dilemma i talked about earlier#about not really fitting in anywhere. cause it's like. if i identify as this i'll be totally dismissing my white family members#but at the same time there's been very few of them that have showed me kindness. and none who haven't been insensitive to my heritage#so should i really feel bad about that? but at the same time... would other people agree with me? would other ppl be fine with me#identifying as indigenous salvadoran even though i've been abandoned by my family so never learned the culture authentically...?#sorry. this is long and i'm repeating myself but i'm just. so tired. so so tired. of everything.

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Valerie i liked this backstory on her. Considering she's brown skin latina and lesbian of course she's an easy target of abuse and bullying then she's also emo. The backstory of her was actually quite good in vivzie lore but the constant joke about genitalia and her view of sex worker is disgusting. So thank you changing her name also giving her proper backstory

Of course! When I started doing this obviously the show hadn't come out yet and we didn't know Valerie (not calling her her original name) was a exterminator. Honestly, I think they should have kept her a human sinner. Yeah I think a fallen angel finding redemption at the Hotel could have been a really good plot line! But personally I think they should have used that on a ESTABLISHED angel.

How fucked up would it be that Emily, someone who is heavens ideal angel, gets outlasted because she's sided with the child of the man that caused all the pain and suffering on humanity. Hell it wouldn't just effect her, it would effect Sera too. Sera obviously doesn't like the extermination but doesn't have the power to stop them. Imagine the FEAR and PANIC that she would be feeling now that her precious little sister is in hell, where she could be exterminated.

Sorry that was a ramble 🙏🏿

Valerie is a character I don't spend nearly enough time on and it's not because I don't like her, her background is increasingly sensitive though. The three most important parts of her background I would argue is her: Salvadoran identity, her LGBTQ identity, and her abusive relationship.

I am White. I have never experienced racial discrimination, something I am increasingly grateful for. How I write racism has to be sensitive because I could spew some racist bullshit if I'm not careful. (Actually my best friend T (not using their real name) is Mexican and has told me about their experiences as being a WOC in my, VERY white southern school. It's so sorry you moved here)

Her LGBTQ background is something I have more experience with. I am a Pansexual but no one respects that. The best I get labeled with is Bisexual and half the time people think I'm a lesbian because my one relationship was a girl. It's alot easier for me to write homophobia because I've experienced homophobia.

Her abusive relationship is something I need to research more. Same things with racism, I've never experiences a abusive relationship.

Valerie is someone I have to include more because I love her so much 💜

Asks are always open, art is always here, commissions are open, clock racists in the face with a rock and or heavy stick.

- ⭐️StarClown⭐️

#hazbin hotel rewrite#hazbin hotel critical#hazbin hotel criticism#hazbin hotel rewrite blog#hazbin hotel#hazbin hotel redesign#vivziepop critical#vivziepop criticism#hazbin hotel valerie#vivziepop critique#hazbin hotel critique#art blog

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Miguel O'Hara Analysis from a First Gen Latine Perspective; Crab in a Bucket.

Alright, I'm gonna start this by saying this: I am definitely not the most articulated person when it comes to explaining my thoughts. Most of this is just putting my heart on the page by relating what I saw in Miguel's behavior and just one outlook out of many layered analyses.

Anyways, here's my analysis of Miguel O'Hara and how his internalized racism and generational trauma/jealousy stands out to me, especially as a first gen mixed Latine.

Let's lay some groundwork for my perspective first! Hey, you can call me Moonie or Blue. I use it/they pronouns, proud to be queer! I'm a highschool dropout, and both of my parents were immigrants from rural and abusive families. Mexican and Salvadoran/Salvi to be clear. Have lived in poverty my entire life, and been whitewashed and forced to assimilate to keep up appearances for a good chunk of life.

I've heard bits and pieces about Miguel's comic origin, but haven't read them myself so apologies if I get some things wrong. I have seen Spiderverse 5 times so I feel like that's good enough. Anyways here's a story anecdote;

I went to Mexico not that long ago, to learn a trade from some family. Real blue collar, labor intensive, factory work. I was there for a while, and really got to marinate in what it's like to live in a country where you're not the minority anymore. I'm not targeted, I wasn't (entirely) racialized anymore. I was able to explore my family's culture more. Not that I've ever been entirely separated from it. But growing up in a white school where knowing Spanish forces you to go to English classes even though I had proved myself multiple times does something to you.

You assimilate, you're taken away from your culture. Anyone like you. It's lonely. And when you do find someone else like you, even if it's not the same country, but just latine, it's usually a fun experience to share our lives. Like a little secret between us no one else has. But as you grow and see more people, you realize how separate you are from the rest. I can't exactly relate to the latine-american experience (tm) like others do. I don't call myself Mexican or Salvi American, I don't like to. I didn't grow up that way. Ive always preferred to use the first generation. Or child of immigrants.

Miguel O'Hara is a mixed Mexican/Irish man. And from what I've seen; not all that attached to his Mexican identity either. It's made more prevalent in the movie however. He doesn't have a strong accent, he has the high cheekbones and eyes I'd recognize on a cousin. But the strong jawline and sunken face of a mixed man who's certainly not taking care of himself.

He reminds me of my cousins. Or my uncles.

He displayed a familiar rage to my own; lashing out and stressed. But it's got some sinister machismo underlaid in it. When he yells at Miles, all I see is my dad yelling at me, or myself yelling at my dad. Bc anger is the only way we knew how to communicate and express ourselves living under so much scrutiny all the damn time.

Bc yes; the spiderverse is amazingly diverse, and anyone can be the mask. But Miguel obviously doesn't really see it that way. There are exceptions. It's always come off to me how most of the maskless spiders we see have black and brown faces. And while I'm sure it's not all white. The amount of Peter Parkers. I'm sure they are the large majority. Or at least it feels like that.

Maybe he sees the spiders that aren't peters as straddling a thin line. A tenuous canonicity in a sea of Parkers. They don't break canon, but they're outliers. It just reminds me of the few black kids or brown kids I'd see in my white school. Maybe one or two in my own classes. And none of us reached out to each other often. We were left alone.

And left to be scrutinized by our white peers and teachers and school staff.

They might not say anything; but you feel that weight. That gaze on you at all times. I was lucky for being light skinned and ambiguous in my appearance. Some confused me for the few East Asian kids even. A more 'model' minority and free from more gazes able to 'pass'. Miguel is darker, but he's conventionally attractive, tall with straight hair and a sharp jawline instead of short, chubby cheeks, round face and curly hair.

I get praised for being light skinned and largely unblemished, for being skinnier than my siblings and having a more traditionally feminine fashion and hobbies. But my anger, temper, and lack of 'respect' downgrades me. My lack of education? More so.

My uncles would say;

"Well! Since you won't finish school, you might as well get a job wherever you can and support your family!"

"Yes, I'm trying my best, but I don't want to work for pennies and bad hours. A lot of places don't want to compensate me."

"How ungrateful! When we were your age, back in our day none of us were blessed to be in your position! You live in America, where you ungratefully gave up such great education and life! We were lucky to even go to elementary school! Your grandfather had us working in the fields, or fishing instead. And when we could work? We took what we could! It didn't matter if the company treated us right, paid us good, or gave us good hours, we did what we had to for the family! Your generation knows nothing of hard work!"

"But how can you have pride in that? How can you not understand how exploitative that was? Letting them work you like mules and destroy your bodies? Why did you not fight? Why would you want to suffer like that?"

"We know we were not treated right. But we have the guts to do work no one else wants to do! We're men! It's our duty to take pride in providing for the family. We break our bodies for our children and love– your parents did not do the same for you to copy our hardships. But if you won't take that opportunity given to you– then you'll face the consequences and learn your place. The companies will never treat us better; you should've been better sso you wouldn't have to face the same as us."

"So you agree? They won't change and they'll keep exploiting you or anyone else who doesn't exceed great expectations? That these companies are taking advantage of people as desperate as you to get away with it and shrugging off any attempts to unionize and make things better? They're enslaving our people. And you're just going to go along with it? Because that suffering makes you feel prideful, meaningful? Do you really just accept this shitty undeserving position in your life? All because you feel like you deserve it for the outcome of your life you had no control over?"

That is to say. My relatives could not understand why I do not fit their perception of America. Even in Mexico, where although they are poor and the majority; they idolize the US. They boast about working illegally in the US under exploitive companies to bring the mighty American dollar home. They scoff at the notion of unions, government aid and compensation bc they think those that live in the US and work in blue collar jobs are undeserving of the scraps we get for being undereducated or face institutional racism at every corner. Even in their position it reeks of classism. For them the US is a temporary shitty job to work in order to make themselves richer bc the dollar is worth more than the peso. They can't empathize with their struggling relatives across the border bc hey! The US, is amazing. Nevermind it's the exact reason why their own country and many others face the hardships that they do.

They don't realize the internalized racism in their pride. Feeling as if their lack of education and standing makes them only deserving of the worst jobs. That it's the only thing they can do right and are worth for. That anyone who doesn't succeed even after getting a better chance only deserves the same pain in order to uplift someone else's worth and has a chance. You become a lost cause; your only worth is a cog in the system and uphold the status quo. Never to question it, never to try to reach above your station after you missed your chance.

Like crabs in a bucket, they want to drag you down with them. Out of jealousy and misdirected anger. And for not meeting expectations. And for your own good, to learn your place.

Older relatives, and even immigrant parents often become extremely jealous of their children. For getting better lives they tried so hard to secure for them and for having the things they never had; or for not going through their own hardships. So they try to live vicariously through their children. Giving them great expectations to live up to bc they don't know how to compartmentalize all the racist trauma it took for them to get there and the real faceless enemy that put them through it. But their children have faces, their children are theirs– not people but property says America, and Catholic/Christian culture.

Immigrant parents love to pull the card of how indebted their children are to them, guilt trip them with their own pasts and current struggles. God forbid if you try to fight back and question the one authority and control they have over you.

Not all parents of course; But Miguel reflects this too me.

He may be more coded as being whitewashed and excluded from his culture. But he tries to fit in a curated collection he doesn't fit with. He puts up appearances as a strict, competent leader, but since he has an unremovable aspect to him that separates him from the rest- he wasn't bitten, he was mutated with a spider- which everyone makes clear to you.

Everyone makes it clear that you're not white, even when white culture is all you know having been so sanitized, defanged and removed from your own. That you wont ever fit in and must grovel for the rest of your life to make up for it. Even if it's all you've ever known.

Miguel is a spider, but he wasn't bitten so he's not a 'true' spider he tells himself. He's othered as well with what I interpret as unintentional microaggressions.

"He's like a ninja vampire but a good guy."

"you're just gonna have to shut up and trust me, I'm a good guy!" "You don't look like a good guy."

"You're like the only spiderman who isn't funny!"

"Dude are you sure you're even spiderman?"

-

"You're like a feisty Latina!"

"Wait, you were born here?"

"You don't look Latina!"

"Are you sure you're even Mexican if you can't speak it?"

He uses English more often, and Spanish as a quick add in. English is obviously preferred due to the fact his accent isn't all that strong and uses short repeated words or phrases.

He's violent when he first meets Miles. Throwing a trash can at him, rejecting his food, and admonishing him for something that wasn't necessarily his fault. But he does 'cool down'.

Him throwing the can reminds me of machismo, and how violent Latino men can get. It's a bad stereotype but for the movie- this struck me more as a critique of it. Enforcing some weird dominance and need to be aggressive to follow that weird expectation and allowances but also– it feels in line with who he is.

I have had more than a few rough patches being physically violent to express my anger when I couldn't win something or felt too small and had to lash out to make myself feel heard. Hitting someone, slamming doors, breaking things, yelling, and destroying things. I moved past that stage as I grew older and wasn't a child anymore. But hell. I've don't things I'm not proud of yet can't help because all my life you're told to be the model brown person. To never express rage and seem like the monster everyone is waiting for you to show. To it lies festering until you can use it behind closed doors. Latina girls aren't allowed to be visibly angry like that- and while it's expected from Latino boys, and feared when Latino men express it. Most of the time, we're not allowed to spread anger at all. Otherwise it does make us unreasonable, angry monsters.

You're not allowed to be angry or frustrated. Which only makes it worse.

I'm not excusing his actions. But his rage reminds me of my father or a relative, or even my own lashing out on a younger family member because it's so normalized to do it only to family and the young- the only excusable people to express it at without repercussions.

But then he cools down, he gets quieter, when Peter B walks in. And reminds himself of his audience and a fellow adult.

He then tried to be more rational and explains to Miles what he believes he did wrong. Tries to even relate his own trauma to convince and prep him to not put up a fight when he inevitably tells him the truth of what's to come.

"you can't ask me to just let my dad die!"

"I'm not asking."

It's a familiar emotion. When an adult, a father, a mother, an aunt, an uncle, or even a sibling tells you that something is going to happen whether you like it or not. Enforcing that will onto you for 'your own good.' Or because it's what 'has to happen."

Miguel is jealous of Miles. He got bit, he's more traditional in origin than Miguel, but he won't follow the expectations and 'bright future' he's been set up for. For 'wasting' his chance. A chance Miguel would die for. One similar to his own. As an anomaly that replaced/continued the mantle of spiderman after their original perished.

Because why would Miguel only mess with Miles now, instead of when he had a chance? If he had all this time and knew about him, why wouldn't he just cut the problem from the root earlier? Why would he let Miles live and work so hard just to restrain him for the canon even of his dad dying to pass? Why would he let Miles be this 'Original' Anomaly and run free?

Bc he knows on some level, he's spiderman too. More than he is. Miles still fulfills his position as spiderman in his verse. There's no need for Miguel to kill him or do anything other than make sure the canon still happens in that verse and then never let him escape his own world again. Nor does he likely really want to hurt/kill Miles. Honestly, it seems if Miguel had it his way from the start; Miles would have been left completely alone and isolated from ever knowing about the Spider Society at large and let him be Spiderman of his world. If he didn't know about the society he wouldn't know about the canon even and try to circumvent it and everything would have been smooth.

Bc what happens if Miguel won and kept Miles at HQ? His dad died and he's sent back to being Spiderman forever excluded from HQ? He never tries to get rid of him. And it's obvious; he never did anything to help the 42! Miles' universe beforehand either. Content to just let it be before Miles gets there. It doesn't seem like he has any plans to actually do anything about a verse missing a spiderman so long as it's not destabilizing.

He's mad that now there has to be a spiderman that took the place of one that didn't need to die; but that world still needed a spiderman Miles fulfilled. Now there's one without a spiderman too, but he can't take the spiderman from one world to the other– not when, although it's in shambles, it is still intact. He doesn't need to intervene. He just need to uphold the status quo and never question it.

He's jealous that Miles got to be a more traditional spiderman, but none of the hardship because he feels like Miles didn't do anything to deserve becoming spiderman in the first place. But if he's going to be one, then he better fit his exact mold to make it up to him. To prove he has worth in the cog. Accept the shitty hand he's been dealt and take pride in the awful like he has bc that's the only way to make him feel like he has any worth too anymore.

Miguel tried to rise above his station, he aimed for that better life. And what did it get him? Nothing. Everything was taken away from him. It was just proof by the universe telling him he did not deserve a better life than the shitty one he was dealt. He's just like my uncles, traumatized from working hard for pennies, and thinks he's deserving of it, because he wasn't educated/a traditional spiderman. And that anyone else who doesn't take the better opportunities needs to be taken down with him in shared suffering.

He sees Miles: another mixed kid, optimistic and worthy, confusingly rejecting every opportunity in the face of a little short term pain. Giving it all up bc of one small hiccup. He thinks Miles is ungrateful and greedy, wanting it all; after all he's seen what happens when you try to have it all.

In a twisted way. He thinks having his father die is the lesser evil, the smaller pain. A singular familial death is a small piece to pay for an entire stable universe and the glory spiderman brings. That by showing this reasoning to Miles, not giving him a choice and just enforcing it like he knows better than an ignorant child will save him the pain and effort. He's teaching Miles his internalized racism and trauma. Passing it down to him like it's a survival lesson. Telling him to swallow it like a bitter pill that will make him feel better. He treats Miles like getting bit was a moral failure and that he has to make up for it.

But like me to my Uncles. And Miles to Miguel, he tells him it isn't right. That thinking is wrong. This system isn't my fault. It's a bad system that needs to change so this never happens again. You don't have to suffer to succeed and survive. You don't have to accept scraps when you can reach for the full meal. You have to try for something better, no matter how hard, and fight to make things better.

Don't let sleeping dogs lie. Miguel can wallow for all Miles cares, but he isn't going to let himself lose that same fire for doing what's right and aiming for a life that he wants for himself and his friends that they actually deserve.

Elders let the status quo remain, they often feel like nothing will change, but we can't accept that otherwise nothing will actually get better, never going out of that system that beat them down. Constantly expecting the younger generation to bend to their will and experiences. Miles and Hobie make it a point to show that no, they can put up a fight and they should and shame everyone else for just accepting that false narrative blindly.

There's so much more I could get into but this is long. Like how he contradicts himself to better suit his argument and what not. I have so much to say but this was all what I've been rotating since watching the movie a ton of times. None of this even low-key touched on my issues on how he's viewed and portrayed by fans but- I hope this outlook kinda helps to humanize him? Like. Of course I know he's being unreasonable and violent/aggressive towards a kid. But at the same time, I feel like most people just see him as this angry violent person who is just on some self righteous power trip asshole instead of a complex character and TO ME- a reflection on latine elders and yet also what it's like to grow up whitewashed/undervalued and trying to bestow that trauma to a younger Latino boy as a bad way of teaching a life lesson, to assimilate him. It comes from a bad place of… not love, but just. Wanting to prepare someone for hardship and yet not questioning why he have to deal with that hardship in the first place.

Anyways good night! It's 3:30 am dear God excuse any mistakes I needed this out of my system.

#atsv#atsv analysis#spiderverse analysis#miguel o'hara#miles morales#atsv miguel#blue speaks#blue's analysis#do not clown on my post so help me god i will turn off rb and replies of someone acts stupid#anyways personal hc but Miguel is also aroace and theres nothing u can do about it taking him to the movies cousin time#he was not my initial fave or anything but theres so many uh. bsd takes or just. idk i felt like i had to say my piece on this man from my#own personal experiences#long post#that vibe u get when the family considers you a failureeeee and shares their unwarented advice/opinions#and think they know whats best for youuuuu

44 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey I don't want to start an argument or anything because it really isn't that serious but American Latinos didn't really have a choice to assimilate. They weren't allowed to speak Spanish in public, they were segregated and a lot of older generations carry that trauma on similar to how Indigenous Americans have. This causes a lot of (especially non white) Latinos to have identity issues because they're constantly told to speak Spanish and constantly ostracized by Latinos from Latin America who don't understand what it's like to live in the U.S as a poc. Tbh It's really interesting to me how white Latinos from Latin America will claim every American White Latino while not claiming any black or brown Latinos and dismissing them when they try to reconnect with their Indigenous half. I understand why Jenna Ortega and other actresses weren't taught Spanish. White Latinos are seen as superior to black and brown Latinos in the U.S and are rarely if ever treated with the same amount of disgust. As an American Latino I agree we can be really annoying but I don't understand why mostly white Latinos have an issue with American Latinos trying to claim their culture. There's just something weird to me about white Latinos trying to gatekeep the term "Latino" while not even trying to hear what non white American Latinos have to say. I guess I have a more personal take on this because I'm half Salvadoran half Mexican, and Central Americans are commonly looked down upon by other Latinos so much that many Salvadoran Americans lie about being Mexican because it's more accepted. Which is something I've personally experienced in the past few years with the newer president suddenly everyone wants to claim being half or full Salvadoran when they acted like it was a slur before. My Salvadoran family even has some identity issues because they ignore their Indigenous heritage in favor of being Mestizo. Now this is only my opinion as one American Latino I'm not their rrepresentative and you can have your opinions lol just wanted to give some context I guess.

If you checked my tags you’d see I imply I was talking mainly about American white Latinos.

Idk which white Latinos you interact with but most Brazilians don’t claim any white American Latino lol I’ve never seen that happening before.

I don’t disagree with you about how white Latinos are better treated than POC Latinos, I’ve never said otherwise 😃

It’s definitely not only white Latinos “having issues”, maybe this is just your experience. And based on my own opinion I have issues because when it comes to media outside Latin America American Latinos are definitely way more represented than us (and I say Latinos born and raised in LatAm in general). A lot of them like to speak over born and raised Latinos as if they’ve ever been here. A lot of them treat race just like Americans and are not willing to listen to how race and ethnicity are seen differently here because, just like most Americans, they think their views are universal. You implied white Latinos as if also talking about me so according to your (and I mean the American view of race and ethnicity) views I wouldn’t be white lol

I hope you can understand why I am so annoyed of this because it’s truly annoying how (talking about outside LatAm) we don’t seem to have much voice, and when we do we’re represented most of the time by American Latinos.

Not to mention how annoying some people (like I said in my other post, especially white people) treat being Latino as an aesthetic, and when it comes to actually getting in touch with LatAm culture and language they treat us as inferior.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fear the Walking Dead Season 6 Episode 2 Review: Welcome to the Club

https://ift.tt/37iTzCl

This Fear the Walking Dead review contains spoilers.

Fear the Walking Dead Season 6 Episode 2

Generally speaking, I tend to take a more philosophical approach to writing my reviews. Zombie shows in particular have a lot of meat on the bone in this regard, and offer a lot of food for thought. Puns aside, this week’s “Welcome to the Club,” directed by none other than Fear the Walking Dead’s own Lennie James, tackles the notion of identity-defining morality in an episode that’s filled with plenty of twists and turns. You can read more about James’s first time in the director’s chair in our interview with him here.

This may be James’s directorial debut, but he nonetheless delivers one of Fear’s strongest episodes. I certainly appreciated the old-school horror movie vibe he brought to this week’s morality play. And he gets strong performances from Rubén Blades and especially from Colman Domingo in particular. Which makes sense, given “Welcome to the Club” is really Strand’s story. Indeed, Nazrin Choudhury’s script posits that who we are versus who we want to be can seem like an insurmountable distance. As far as dramatic conceits go, this “conscience gap” is fertile ground when deconstructing someone as morally conflicted as Victor Strand.

As we soon find out, though, Strand’s gap is really more of a gaping chasm. He’s quick to point fingers at Alicia and Daniel for his moral deficiencies, but the blame is really his alone to bear, as it should be. But more on that in a bit.

In the meantime, “Welcome to the Club” busies itself with several unexpected reunions. As you’ll recall, Virginia arbitrarily split the bigger group up at the end of last season. Strand and Alicia wound up at the same settlement, pulling latrine duty since their arrival two months earlier. So imagine their surprise when they later discover Daniel cutting Virginia’s hair. What’s more surprising is that he has no recollection of Strand or Alicia. Naturally, his friends believe he’s putting on an act. How else to explain how a once-ruthless member of a Salvadoran death squad could be so easily intimidated by Virginia? He doesn’t seem to remember Charlie (Alexa Nisenson) either, even after she plays a bit of a Traveling Wilburys song he once taught to her.

In one of the episode’s better twists, and in another surprise reunion, this time between Daniel and Morgan, we discover his amnesia is nothing more than a clever ruse. Blades is great at portraying two very different states of mind, proving that Daniel is just as cunning as ever.

Read more

TV

Fear the Walking Dead Season 6 Episode 1 Review: The End Is the Beginning

By David Zapanta

Strand hasn’t lost his edge either, when it comes to pulling the wool over people’s eyes. He would have Alicia believe he is a changed man, no longer capable of the selfish behavior that’s gotten people killed in the past. He’s trying hard to retain his identity, to honor Daniel’s parting words to remember who he is. This is interesting advice, given their acrimonious history. So I wonder if what Daniel really meant was for Strand to embrace his cowardly instinct for self-preservation. Luckily, Colman Domingo is at his best when he’s bringing out the worst in Strand.

Strand’s not the only coward in the group, however.

Enter Sanjay (Satya Nikhil Polisetti). He’s part of a bigger group of prisoners that now also includes Strand, Alicia, Charlie and Janis (Holly Curran), which is tasked with clearing out an old sugar warehouse. As we already know, this is way more difficult (and deadly) than it sounds. But when Strand and Alicia learn from Virginia’s younger sister Dakota (Zoe Colletti) that there’s a secret weapon stored in the derelict building, they decide to acquire the weapon for themselves.

That the weapon is housed in an old sugar warehouse is important, if only because we encounter molasses-infused zombies. Not only is the spilled molasses sticky, it means the undead now possess a sticky, inescapable death grip. There’s a B-movie schlockiness to this that’s fun without being too silly. The makeshift cattle chute the prisoners construct to corral the zombie horde is also a clever bit of fun. That is, until the walkers begin to overwhelm the jerry-rigged barriers. Two armed rangers are easily taken out by the horde while the prisoners manage to defend themselves with nothing more than spears.

But things go from bad to worse when Sanjay abandons his post at the gate. Strand tracks him down to the trailer where he’s hiding. There can only be one coward in the group—and in this case, it’s Strand. In a particularly dark turn of events, he sacrifices Sanjay to save everyone else. But by killing Sanjay, Strand is also surrendering any last traces of his humanity. In other words, he’s finally embracing his true nature. He doubles down on this later by lying about trying to save Sanjay, but this is vintage Strand. While his actions might be morally repugnant, I still much prefer this version of Strand to the watered down version we got last season.

In another neat twist, the secret weapon turns out to be a MacGuffin. By demonstrating his mettle and ingenuity in clearing out the warehouse, Strand has proven to be the very weapon Virginia was searching for all along. He even receives a key to the city for his troubles—which means his days of cleaning latrines are over.

Now that he’s able to call his own shots, Strand reassigns Alicia to another settlement, where she can no longer remind him of the decent person he might have been. He’s not comfortable being a sheep, even if only by outward appearances; Strand would rather be a wolf in wolf’s clothing.

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ playerId: "106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530", }).render("0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796"); });

My only quibble with the episode is that Alicia didn’t have more to do. Yes, I realize this was really more Strand’s story this week, and Debnam-Carey does well with what she’s given. But, in my mind, a day-one character and the last remaining member of the Clark family should be shouldering more of the story. Here’s to hoping Alicia’s best moments are still ahead of her this season.

The post Fear the Walking Dead Season 6 Episode 2 Review: Welcome to the Club appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/2T2HA3I

0 notes

Photo

Traditions and Assimilation

American and Latina

Last fall was the first time our niece, who’s 8 years old, carved a pumpkin for Halloween. Andrea and her boyfriend showed her how one weekend while she was over visiting our parents’ house. While she’s been trick-or-treating, carving pumpkins isn’t a part of her parents’ culture. When she took the jack-o-lantern home, they weren’t sure where to put it or what to do with it.

My siblings and I grew up in small, rural towns where our family was one of only a handful of non-white families. I think that played a large role in why our family assimilated very well. Growing up my parents embraced a lot of American traditions. We decorated for Halloween and went trick-or-treating. We celebrate Thanksgiving and have all the traditional foods from turkey to green bean casserole to pumpkin pie. Each year (even now) we get Easter baskets. The tooth fairy came and took all of our baby teeth away. All of these American things, we did.

It’s true that my parents infused some of these American traditions with Salvadoran flavor. We never believed in Santa Claus because instead of celebrating Christmas morning, our family had a big Christmas Eve dinner of tamales and then stayed up until midnight to open presents. And New Year's Eve isn’t the same without the 12 grapes you eat while making wishes for the new year in the last minute of the old year.

So when I first found out that our niece had never carved a pumpkin until now, I was a little sad for her. But the more I thought about it, the more I wondered if I should really be feeling sad for me and my siblings? Did our family assimilate too much? Did we miss out on learning about our Salvadoran and Honduran heritage? Should we have been celebrating those holidays in addition to American ones? I couldn’t even tell you what traditional Salvadoran and Honduran holidays are.

This is something I have always struggled with. I have never felt Latina enough. I relate very strongly to being a child of Latino immigrants and all that means, but for me to personally claim the identity of Latina sometimes feels disingenuous. I don’t speak Spanish fluently. My husband and closest friends are white. When I told my doctor in our first meeting I was Latina, she was visibly surprised and pointed out that our skin color was roughly the same. She’s white.

A part of me feels like I missed out on my chance to connect to our culture. With our parents moving, celebrating the major American holidays is going to be hard enough. I know I could make an effort to learn more about our culture and the history of what it’s meant to be Latina in the U.S., but I don’t know that I will. And maybe embracing my child of immigrants narrative should be enough for me to feel confident about my Latina credentials. Afterall, Latinos come in all shapes and shades. Our stories are all different and who’s to say one is better than the other.

-Vicki

#LatinoAmerican#LatinaAmerican#assimilation#twocultures#latinaandproud#self identity#threemijitas#sisterswhoblog#browngirlswhoblog#VickisPost

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Argueta, J. (2016). Somos como las nubes. We are like the clouds. Toronto, ON: Groundwood Books.

Illustrated by Alfonso Ruano.

Translated by Elisa Amado.

Review # 9

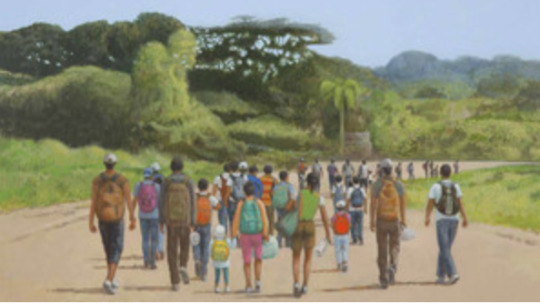

Somos como las nubes (Argueta & Ruano, 2016) is a realistic fiction picturebook story for children and youth, told in verse. Collectively, the poems and accompanying artwork done in acrylic utilize both first and third person narratives and “describes the odyssey that thousands of boys, girls and young people from El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Mexico undertake when they flee their countries because of extreme poverty and fear of violence. They abandon everything in hope of a better life” according to author Jorge Argueta. Jorge Argueta is a “native Salvadoran and Pipil Nahua Indian” who “spent much of his life in rural El Salvador [and now] lives in San Francisco.” The poems and accompanying illustrations do not shy away from the real and realized fears and dangers experienced by young persons who migrate from Central America and Mexico to the United States of America with conversations of gangs, poverty, coyotes, migra, border-crossings, and homelessness. Through reading this text, “poetry demands a filling in of detail and mood on the part of the reader plus an understanding of the characters’ feelings and thoughts as well as intepretations of symbolic language and its implications” (Botelho & Rudman, 2009, p. 195). Argueta & Ruano juxtapose the dark - darkness both physical and spiritual with illuminations and use of brightness and color through their sharing of places rich in culture and lush landscapes adorned with beautiful flora and fauna and native animals and birds, and beautiful people and friendships.

Argueta’s telling of the odyssey of young persons from El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Mexico is told from a Salvadoran perspective and utilizes his own language - Salvadoran Spanish, whilst providing translations for both other Spanish language speakers and English speakers. Argueta provides explanations of some of the translations, as some readers may not be familiar with that naming/calling of the particular item. For example, he uses the word “cuches” for pigs in one of the poems, but provides also “puercos and cerdos” in the footnotes - cognizant and respectful of the diversity of his Spanish-speaking audience; demonstrative of his diasporic view and approach to the (im)migration conversation. This is also demonstrative of his (re)claiming of identities of persons from various parts of Mexico and Central America, against a homogenized American narrative of the immigrants from those regions.

How are they like the clouds? Is it that the clouds take on many different shapes and move - with help of the wind - across space, sometimes the skies are calm and other times not, sometimes there are many clouds together, other times there are just a few wispy ones, sometimes there is only one or none at all. The use of the metaphor, immigrants as clouds, speaks volumes. Clouds can float beyond borders and above walls. Clouds are needed because they bring rain that helps our plants and vegetation grow, supplying us with food. To see immigrants as clouds, is to see that there will always be migration and immigration; and that there is great value in that. We are Like the Clouds (Argueta & Ruano, 2016) invites readers to travel through space and time, like the clouds, and take in the many sights, sounds, smells, tastes that reminds and speaks of home. Why would a young person choose to leave their home and all that they knew and with which they were familiar?

Though this is a work of poetry, Argueta’s collection informs readers of many of the elements - natural and unnatural, human and inhumane - of the journey of young persons traveling from Central America and Mexico, evoking some of the many elements and senses involved.

Nature - Flora, fauna, and birds

The reader’s journey begins in El Salvador with a young boy flying amongst the clouds looking at “the huge San Salvador volcano” in the distance. He flies amongst the cows, horses, pumpkins, and even elephants while he reminisces about home and childhood, thinking about “papusas, tamales, popcorn balls, cotton candy” and “cornfields in bloom, pumpkins and watermelons, parrots and kites, and the huge San Salvador volcano.” “Mi barrio” “My Neighborhood” opens up space for closer examination of what is home. What is home? Here Ruano provides fantastical or imagined recollections of home in the form of el gallo in a track suit, holding a mirror in one hand and a candy in the other. It reminds me of the Martina the Beautiful Cockroach: A Cuban Folktale (Deedy, 2007) and Don Gallo and his big beautiful shoes with sunglasses on his head.

These fantasy elements easily coexist with real and natural elements like “The Azacuanes” - these are birds of prey which travel together, aves rapaces de El Salvador. “Twice a year, an estimated 10 million migratory raptors and other birds cross Guatemala heading South in mid-October, and North in March-April. This phenomena is known in Guatemala and Central America as Azacuanes” (www.arcasguatemala.org). “Flame tree” is another natural element that shares a space in this recollection of home with its beautiful red blooms. Though it is not centered, one cannot help but to notice its bright foliage existing in contrast to the pale ground and the pale colors of the buildings. Whilst admiring its beauty, you could almost miss the persons - their backs to us - walking away from all they know, towards the distance.

La Campanera Neighborhood

The journey continues and again we see the fantastical mixed-in with the realistic in Ruano’s illustration of “the painted people” “their arms, faces, chests and backs are homes to tattoos like snakes” “A mí me da miedo que esas culebras me vayan a picar.” This neighborhood, “La Campanera” is not like the neighborhood readers were first introduced. La Campanera appears to be a scary place, inhabited by scary people who resemble cyclopses. When researching “La Campanera” in El Salvador, I learned that it is a densely populated place that is home to many gangs and gang-member initiated violence, soldiers, and abandoned homes. La Campanera is not considered a desired place to live. “El Palabrero” is the gang leader and the person who coordinates all of the criminal activities of the gang,

“He is the boss. He is the one who tells the gang, Hit this one, hit that one. I don’t want to be this one or that one. Let’s go, I say to my father. Let’s go, I say to my mother. Let’s go as far away as we can, where those words can’t touch us.”

Given the fear of the possibility of violence, harm, and possible death at the hands of the gang members, it is no wonder that young people would want to go. Yet not all were able to afford the cost of going - at least by bus. The poem “iPod” is accompanied by an illustration of a young boy holding a dog, waving at a departing bus. “iPod left today for Guatemala” he has managed to sell his possession “you sold it to buy your bus ticket” and is hopeful “I will go to Mexico. And if I can to Arizona. And if I can to Washington where my mother is living.” It is not uncommon for members of a family to travel separately - it costs a lot of money to purchase a bus ticket. It is possible that iPod had to wait until his mother got settled in Washington before she could send him the iPod which would be his passage. Reading “iPod” left me curious about how much it would cost to travel from San Salvador to Guatemala (one-way). I am ever aware of my privilege - middle-class, American, with an income and education, who has travelled to and from many countries in my lifetime without ever having to really consider how was going to pay for my travel. At any rate, when I visited www.pullmantur.com and searched for the cost of travel - turista-class, the lowest available class - for a child aged 12 and under, one-way it was $27.00. This doesn’t seem like much, but when I think of a young person having to part with their dog and iPod to buy a bus ticket, the cost then seems so much higher than I could ever fathom.

There is a pause in the midst of the telling of this journey in the form of a two-page spread - again Ruano shows readers the backs of persons, several more than before, wearing backpacks, some in jeans and t-shirts, others with hats or ball caps, some carry water jugs, young and old, men, women, and children, some holding hands, others walking alone, all moving together. They walk along a narrowing pathway with the dense forestation serving as the backdrop.

“Las Chinamas” is the border between El Salvador and Guatemala.

youtube

It seems so unnatural to have la frontera/the border here. Ruano’s depiction of Las Chinamas shows people moving from a more lush and green space to a space of almost barrenness and different colors. In reality, the border is a socially constructed one represented by the bridge that sits above the Rio Paz/Paz river, on both sides the lush vegetation, the same trees and birds. “When we crossed the border at Las Chinamas, I saw the river Paz. Its water runs smiling between the rocks. Here the cenzontles never stop singing.”

Bestia - The Beast

Argueta shares about the Beast - “the name for the trains the migrants travel on” in his poem “My Father Tells Me.” Similar to the train traveled on by the protagonists in Two White Rabbits (Buitrago & Yockteng, 2015), the Beast has been come to be known as such because of the dangers of traveling in such a manner. These are not passenger trains. They are cargo trains that travel taking merchandise to the North. Migrants gather at outposts to catch the train. They then travel precariously on the tops and sides of any Bestia, hopeful to not get severely injured, maimed, or worse killed.

youtube

Unaccompanied young children making the journey North, travel with dreams of being reunited with loved ones, family members who have traveled ahead of them. Many rely on the help of “the coyote [who] tells us we are almost there.” The coyote is shown sitting with his arms crossed looking over the younger migrants as they sleep in the night. The coyote is not the only person who migrants look to for safe passage to the North. “Santo Toribio, saint of the immigrants, show us the way.” Santo Toribio is a Roman Catholic saint who is believed to be the “good coyote” who will “protect us, lead us. Deliver us from all evil. Amen.” https://www.facebook.com/univisionnoticias/videos/10156716466589796/

Santo Toribio protects our young protagonist and unaccompanied minor all the way across the border into the United States - Los Angeles, the city of angels, “The angels are not in the sky. They are behind the hills, beyond the desert.” Hopefully the angels will watch over him as he navigates the space that he has dreamed of occupying.

The Paleta Seller

With “Paletas” - fruit popsicles - especially paletas de coco from “Mi Barrio,” Argueta evokes those good feelings of home. The colorful buildings are replaced with the colorful balloons, the flaming tree is seen in the mother wearing a brightly colored shirt. Señor Celsio “pushes his cloud-like cart through the streets of Los Angeles.” It is as though all of the sounds, sights, smells, and tastes have traveled all this way...still traveling aboard this cart now. The story, como las nubes, never stops...it keeps moving, traveling.

My favorite paleta is the paleta de coco. When I lived in Austin, TX, home to many (im)migrants - documented and undocumented, some in constant movement fearing the migra could come and get them at anytime, I remember el vendedor de paletas selling paletas from his cart outside the school at which I worked. It is quite a contrast of bitter and sweet - the fear of deportation, living homeless and the paleta - a sweet treat that possesses the ability to transport you back home through an explosion of coconut...if only for a moment.

0 notes

Photo

Louie: So where did you grow up?

Freddy: I was born in West Covina, California and was raised by both my parents in La Puente, California but when my parents divorced my mom moved to Phoenix, Arizona, which is where I spend most of my time now. We moved to a somewhat rural town that has primarily Black and Latinx populations where the white people live in the nice neighborhoods and the people of color lived in the "other neighborhoods." I almost never interacted with white people. My classmates were always people of color with a sprinkle of white people every now and then. However, growing up here was a living hell.

Louie: How so?

Freddy: The first time I was ever bullied was in 5th grade when someone wrote "FAG" in one of my notebooks and it just got worse from there. At that point in my life I knew I was gay but just tried not to think about it and I was also pretty religious so I tried to "pray the gay away.” It didn’t work (lol). 7th grade was the worst year of my life because I was physically, emotionally, and psychologically bullied every single day that resulted in me switching schools. There was not one day where someone wouldn't call me a “fag” or try to fight me because I was "looking at their dick". They would also call me a cocksucker which I never really understood why they called me that because they were just stating a fact. My mom got worried when I came home crying one day from basically being assaulted and we went to the principal and he did absolutely nothing. It was a really dark time for me because even my friends at the time would tell me, "Just come out already" and at that point I just was not ready.

Louie: How did you sustain yourself during that time?

Freddy: I've always used humor to deflect my feelings and emotions so I would just laugh because it was all I could do. In high school it got better but people still would call me a fag and other annoying ass terms. I also dated girls, which blows my mind now but it was the easiest way to deflect rumors. I came out to my friends as bisexual my junior year and my senior year of high school but when I got my first boyfriend and I came out as gay. My friends weren’t surprised but were happy I was living my truth. I came out to my mom October of 2015, which is pretty recent, and while it didn't damage our relationship she doesn’t acknowledge my queerness but it'll take time and I know she'll get there.

Louie: Who was the first person you told actually told?

Freddy: My senior year of high school when I had my first boyfriend. I was so in love with him and because of him I realized that I was gay. I had dated girls before but being with a boy was just so different. I loved this boy, truly, and because of that I wanted to come out and tell everyone I was with him because for once in my life I was happy. One of the most important people in my life is my Grandma on my dad’s side and I decided to tell her first. She did not react the way I expected her to. She told me I was a disappointment to the family and that my family had high hopes for me and now they were gone. She also told me to keep it a secret forever and to never ever tell anyone else. It hurt. It hurt a lot. I cried for a while and told myself I was not going to tell anyone else until I graduated college and had a career. I didn’t talk to my grandma for a while and talked to her for the first time a couple months ago. I do want to have a relationship with her again but every time I see her, her words echo in the back of my head, so it’s a work in progress.

A couple months later I came out to my little brother because one: He is one of the most important people in my life and two: I wanted him to know so I could hookup with guys easier in my room. I told him in the car when I picked him up from school and I remember being so nervous and feeling my heart beat so fast. So I tell him “I’m gay" and he just looked at me and said "Yeah, that’s cool, can we go eat?" I was in shock because it was big secret and he just like curved it completely. Later on he told me he loved me and I lowkey cried because it was the first time a family member had said that. I always look back at that moment because I feel like that’s what coming out should be, not a big deal because I would've reacted the same way if my brother came out to me as straight.

Louie: Did you have any Latino gay men to look up to when you were growing up?

Freddy: I had absolutely zero gay Latino men to look up to. No one is gay in my family except for yours truly. It wasn't until a couple years ago that I found out that I did have a gay cousin but he was kicked out of the family for being gay so he moved to Spain. He reached out to me in 2013 and we talked for a bit but at that time I didn't know he was gay. Unfortunately, he died of AIDS complications a couple months after. I still wish I could have gotten to know him better.

Oddly enough even though my mom is a cis-heterosexual woman, she took a part in developing my queer identity because I felt like she always knew and lowkey supported it. My mom is a very religious woman from El Salvador who fled her home country because it was going through a violent civil war. She came to the States and married my dad but they divorced after 7 years and she raised me as a single mother. Growing up, she always took me shopping and I always helped her pick her outfits and she would always ask me for my opinion. She would always sit me down after her long work shifts and gossiped about her coworkers which I lived for because Latinx chisme is the absolute best. I also remember she would always tell me "Los hombres no sirven para nada" which basically is "men ain’t shit" and would warn me to be watchful of men. Which is why I now have IMPECCABLE fashion (not really), a big ol chismoso, and have always been watchful of the men that try to enter my life.

Louie: What did you think we as a community need to do to survive the next four years?

Freddy: There is so much we need to do as a community to survive the next four years. First we need to talk about anti-blackness in the Latinx community and start by talking to our racist ass family members who are contributing to the problem. The fact that we stay silent when our Tia'sbe saying racist shit is a problem. Also acknowledging our privilege for those of us who are citizens of the United States and stand up for the rights of undocumented immigrants. The easiest thing to do is to stop referring to immigrants as illegal because it paints them as criminals which contributes to this rhetoric that immigrants are dangerous when they're just trying to escape from their home countries that in most cases the US has fucked up. I'm also going to need gay men to stop with this obsession with performing masculinity and femme shaming because its toxic as fuck. I fucking hate it when guys ask me if I'm masc or femme and I’m just like “the fuck???” What does that even mean? Also destigmatize HIV and stop othering those who are HIV+ because it’s dehumanizing as fuck. I’ve heard some pretty ignorant shit about HIV and it’s something that we need to work on. We need to stand up for Trans women of color because the LGB+ community be forgetting that T especially when they are out here dying with a presidential administration who doesn't give a fuck about people of color and even less about the LGBT+ community and even less about our trans siblings. I mention all these problems in our community because in order to survive an oppressive, fascist, racist, misogynistic, homophobic, transphobic, xenophobic government, we have to be able to dismantle these in our own communities so we can come together to resist combat and survive the Trump Administration. We literally cannot afford to be silent any longer. This country hates my existence but my existence is also resisting and I am absolutely proud of being a Queer Ecuadorian/Salvadoran man living in a country that despises me. To survive these next four years, we just need to keep living, keep resisting, keep protesting, keep dismantling systems of oppression, keep holding our government accountable, keep being unapologetically Latinx and of course keep being unapologetically queer as fuck.

Freddy Christian Bernardino, Phoenix, AZ

Interviewed and photographed by: Louie A. Ortiz-Fonseca

#thegranvarones#granvarones#queer#gay#latinx#latino#storytelling#portrait#phototgraphy#resist#familia#photojournalism#lgbtq

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

If the migrant caravan didn’t exist, President Donald Trump might have needed to invent it.

The existence of a massive group of Central Americans pushing toward the US without papers — even if they are still hundreds of miles away — seems like something Trump’s GOP might create in a lab to unleash on the eve of the midterms.

But the caravan is real. The migrants in it — mostly Hondurans (with some Guatemalans), half of whom are girls and women, many intending to seek asylum in the US — are real people.

They made the decision to leave their home countries, assessing that the danger of leaving was outstripped by the danger of facing gang death threats or feeding a family on $5 per day. And they made the decision to go together, joining the caravan as it progressed, instead of alone like tens of thousands of their fellow Guatemalans and Hondurans (and Salvadorans) do every year.

The caravan has provided an irresistible visual for Republican closing arguments about immigration. In Trump’s first TV ad of the presidential primary in 2015, he used an image of a mass of immigrants; fact-checkers revealed the picture was in fact taken in Morocco. Now, as he nears the midterm elections, Trump has the image he wanted all along.

The decision about 160 Honduran migrants made to travel as a group in the open to the US — and the decision thousands have made to join them en route — is the result of a situation that predates Trump. The United States and Mexico have worked to make the journey to the US less appealing to Central Americans, but many residents of the Northern Triangle find the prospect of eventual asylum in the US — however difficult it is to get there — more appealing than the insecurity they’re facing at home.

The current wave of Northern Triangle migration raises hard questions about the distinction between economic and humanitarian migration, the US’s ability to process asylum seekers, and the role Mexico plays in the region. Those are emphatically not the questions that are coming up in the Trump-driven conversation about the caravan — which is using the sheer fact of a mass of people traveling northward to activate fears of an invasion by unknowable foreigners.

Over the past decade, there’s been a rise in the number of unaccompanied children and families crossing the US-Mexico border. Increasingly, they are people fleeing violence and insecurity, coming from the Northern Triangle of Central America — Guatemala, Honduras, and Central America.

Meanwhile, unauthorized border crossings of single adults, Mexicans, and people looking for seasonal work have greatly declined. The result is a change in the character of who is seeking to cross into the US:

To get to the US-Mexico border, Northern Triangle emigrants have to get through Mexico, a journey that takes weeks.

Under current US and international law, asylum seekers from Central America are allowed to apply for asylum either in Mexico or in the US. Many take the first option: Asylum applications in Mexico have gone up more than 1,000 percent since 2013, and most are from citizens of Northern Triangle countries. But applying for asylum in Mexico isn’t a walk in the park. Mexico has been accused of indiscriminate long-term detention of asylum seekers (exacerbated by a two-year backlog in processing applications), and some parts of Mexico aren’t safe for people who are already fleeing violence.

The US has enlisted Mexico to apprehend Central American migrants before they get to the US. Some 950,000 Central Americans have been deported from Mexico over the past several years, and human rights groups have reported torture and disappearance by Mexican security forces.

The crackdown has made an already dangerous journey more dangerous. The harder it is to get through Mexico without attracting attention from the authorities, the more that task falls to professional criminal organizations who might smuggle drugs alongside migrants or abuse migrants physically or sexually. The involvement of criminal organizations makes Mexico even more anxious to crack down.

For some Central Americans, the solution to this problem is hypervisibility: traveling out in the open, as part of a large group of people that can’t simply be grabbed or disappeared. That’s the reason small human rights organizations have gotten people together, on occasion, in “caravans” — and the appeal to hundreds or thousands of migrants who’ve joined them in trying to get to the US.

For some, it’s a way to call political attention to what they’re fleeing and what migrants have to endure; to others, it’s a desperate exodus; to some, it’s simply an opportunity that came along to hope for a better, safer life.

On October 12, 2018, a group of about 160 Hondurans set forth from the town of San Pedro Sula — which in the first half of the decade was often referred to as the “murder capital of the world” — in hopes of arriving to present themselves for asylum in Mexico or the United States.

Seventy-five miles and two days later, the caravan was more than 1,000 strong, according to the estimates of Associated Press reporters. By October 15, the AP estimated about 1,600 Hondurans had amassed at the border with Guatemala.

Jsvier Zarracina/Vox; location and date information via Associated Press

The earliest spokespeople for the caravan were a journalist and former leftist legislator named Bartolo Fuentes and his wife, human rights activist Dunia Montoya. The conservative government of Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández (with the help of friendly media outlets) has accused Fuentes of organizing the caravan to embarrass the Hernandez administration and promote instability.

Fuentes has vehemently denied that he organized the caravan even in its early stages, and has laughed off any idea that he coordinated an exodus of 1,600 people. Instead, he’s painted the caravan as an illustration of how miserable life is in Hernandez’s Honduras: The situation is bad enough, he argues, that so many people have been inspired to pick up and leave.

The government of Guatemala attempted to close the Guatemalan-Honduran border to the caravan on October 15; after a standoff of several hours, Guatemalan officials backed down. The caravan continued to grow as it crossed Guatemala, and arrived about 3,000 strong at the Mexican-Guatemalan border on October 19, when the members slept overnight on a bridge at the border after being driven back by Mexican riot police with pepper spray.

Mexico has begun slowly admitting caravan members to ask for asylum, and several hundred have complied. But more have decided to stop waiting and swim across the river to enter without papers. On Sunday, a surging group of migrants — thousands bigger than the group that had waited on the bridge — agreed to continue onward from Chiapas, Mexico, to the US.

Caravan members have given journalists a variety of answers to this question.

Some of them have pointed to concerns for their safety. One woman told the AP’s Sonia Perez D. that she’d been in hiding after a local gang threatened to kill her because they’d mistaken a tattoo of her parents’ names for a symbol of a rival gang. Another, traveling with her husband and two sons, told the Los Angeles Times’s Kate Linthicum that after her 16-year-old son refused to sell drugs for a gang, “they were going to kill him or kill us.”

Others have cited poverty, and the inability to support their families on $5 a day.

A few are trying to get back to America after having been deported, to return to their families (including US-born, US-citizen kids) and the lives they’d built. “I miss my PlayStation,” one caravan member told Linthicum. “I miss Buffalo Wild Wings.”

In a lot of cases, people are probably motivated by more than one of these — a generalized sense of desperation and a generalized sense of hope for a better life.

But the reasons given by caravan members are squarely representative of the current wave of Central American migration to the US.

In US law, there’s a firm distinction between “asylum seekers” (who are fleeing persecution because of their identity, usually from their governments) and “economic migrants” who are looking for a job. But the division in real life isn’t always so neat, and few of the people trying to come to the US from the Northern Triangle right now fit just one of those boxes.

Many people are leaving because they fear for their lives if they stay, because they’re being threatened by gangs and the local government is either complicit or absentee. They’re seeking asylum, even if their circumstances may not fit neatly into the definition of “persecution” in US asylum law. (Attorney General Jeff Sessions has used his authority to make it harder for people to claim asylum based on domestic or gang violence.)

Others are technically “economic migrants,” but they’re not simply coming for a better job — they’re fleeing desperate poverty. And with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) stepping up deportations of unauthorized immigrants since its inception in 2003, especially of Mexican and Central American men, many migrants who’ve been deported have every incentive to try again.

US law treats these groups of people very differently — deportees who reenter illegally, for example, are permanently barred from ever getting legal status in the US, while people who can claim a “credible fear” of persecution are allowed to stay and seek asylum. But as far as the journey is concerned, that doesn’t matter. They’re all facing the same dangers, so they’re all traveling together.

On October 22, as the caravan regrouped on the Mexican side of the Mexico-Guatemala border, the United Nations estimated its size at 7,322 migrants. The UN estimate is the only official estimate of any sort, so it’s the best thing to go on for now. (Prior to the UN’s assessment, the AP had been estimating the caravan as slightly smaller — 3,000 on the Guatemalan side of the border — and it’s not clear whether the caravan has grown or the AP was underestimating its size.)

Estimating crowd size is an inexact science even when the crowd is stationary. But the caravan isn’t just on the move; it’s stretched out — people go at their own pace, hitching rides or resting. It’s possible while the leading edge of the caravan was stuck on the border bridge between Mexico and Guatemala, the rest caught up, causing the estimate to grow.

It’s hard to tell where the caravan ends and typical everyday Northern Triangle emigration begins. As Bartolo Fuentes pointed out in an interview with CNN Español, the size of the caravan as it left Honduras was roughly equal to the number of Hondurans who emigrate every 15 days. And the coverage of the caravan appears to have inspired others to plan their own.

The size of the caravan has led a lot of people to assume that someone must be organizing and supporting it. A video that appears to be from near the start of the caravan route, which shows money being handed out to women, has been used by conservatives in the US as evidence that the caravan is a liberal plot (Florida Republican Rep. Matt Gaetz has blamed George Soros) and by the Honduran government as evidence that Fuentes and Libre, the political movement to which he belongs, are behind the caravan.

But whatever that video actually captured, it doesn’t represent the truth of the caravan as it’s continued into Guatemala and Mexico — a straggling procession of people relying on humanitarian organizations and sympathetic locals for food, transportation, and medical assistance.

It’s hard to guarantee safety for such a sprawling group. The Honduran government has confirmed that at least two caravan members have been killed in accidents since the departure; several police officers and caravan members were injured when the caravan burst through a border fence on the Guatemala-Mexico bridge on October 19. The bet that caravan members are making is that it would be more dangerous to travel alone.

Because the caravan is large and not centrally coordinated, however, it’s impossible to know the identity of every migrant traveling with it. That makes it very easy to raise the specter of criminals or terrorists hiding within the caravan — to use any question mark to paint the whole caravan as a faceless and threatening mass.

The short answer is b-roll.

B-roll is a TV industry term for the brief clips that run on mute to illustrate a segment while an anchor is narrating or a talking head is commentating. If a channel is giving a lot of coverage to a particular story, the b-roll clips it has for that story will get a lot of play — making it hard for any but the most dedicated viewer to tell when or where something happened, or even whether it’s happened more than once.

Caravans make for evocative b-roll: masses of people pressing toward the United States. Fox News leaped on the story of the caravan the minute it reached Guatemala with captions that talk about a press of people at the “border” and only a tiny note in the corner identifying that “border” as a Central American one.

And the president, Fox News-watcher-in-chief, has taken his cues on the caravan from the cable news channel. He started railing about it when Fox started covering it on October 16.

The caravan is a perfect obsession for Trump for the same reason it’s a perfect obsession for Fox: powerful images that appear to validate conservative base fears of “invasion” by “lawless” foreigners and the countries that “send” them. Trump himself has been using imagery like this since he started his presidential campaign in 2015 and talked about Mexico “sending” rapists and murderers over the US-Mexico border.

The caravan has provided more fodder. It’s a constant motif of his near-daily rallies and his morning and evening tweetstorms as the midterm elections approach.

His rage is being fed by hardliners in the administration who want to do more to crack down on families and asylum seekers at the US-Mexico border (options being considered include forcing parents to choose between months-long detention and family separation). It’s also being fed by Fox.

Other Republicans were already following Trump’s lead in making immigration their key issue in the closing weeks of the midterm campaign, amid concerns that the Republican base won’t turn out without Trump on the ballot. They’ve followed his lead on the caravan too. While GOP hardliners within the administration are using the caravan as a reason to push for a change to the laws governing children and asylum seekers who arrive at the border, Republicans have turned the caravan into a reason that Democrats shouldn’t be allowed to take Congress — because they would let in untold numbers of migrants.

The Trump administration absolutely believes this is the way to fire up the Republican base for the midterms. But it’s hard to tell how much of this is deliberate strategy and how much is Trump’s personal obsession — or if there’s any difference between the two.

Even before the caravan set out, the administration was raising alarms about families coming to the US-Mexico border. But the current situation isn’t really a crisis of numbers so much as a crisis of resources.

Overall, apprehension levels in August and September 2018 were only a little above average for the past several years at this time. And they’re still way, way below pre-Great Recession levels. (For context, apprehensions in fiscal year 2018 were a little more than half as high as fiscal year 2008, and about a quarter of fiscal year 1998 levels.)

But the people coming in are different.

Over the past several years, apprehensions of single adults at the US-Mexico border have declined. At the same time, apprehensions of unaccompanied children, and of parents with children, have continued to increase. In September 2018, children and families made up more than half of all people apprehended crossing the border illegally — up from 17 percent in September 2013.

The US has developed a border policy that’s designed to maximize the efficient apprehension and deportation of everyone trying to cross the border illegally and not get caught. It is not designed to facilitate the processing of families who are seeking asylum, a decision that is not immediate. Nor can families be kept in conventional ICE detention centers while they wait.

Refusing to offer asylum would violate international law. So the Trump administration has been trying to crack down on how families are treated after they arrive — by detaining or separating them, for example.

There is some evidence that efforts to deport families leads to fewer people seeking asylum. But there isn’t evidence that harsher treatment of asylum seekers accomplishes the same goal. Neither the 2017 pilot nor the widespread 2018 policy of family separation had the effects that officials hoped for at the border. Neither did Obama’s efforts to expand family detention in fall 2015.

The Trump administration’s sweeping border crackdown has, in fact, made it harder for people to seek and receive asylum. But it hasn’t been enough to persuade people that they’d be better off staying in their home countries.

There’s only so much the US can do with the caravan still weeks from US soil. Sending US officials to stop a group of people from crossing a border from one non-US country into another — or trying to disperse them within Mexico, for example — would be a pretty straightforward invasion of national sovereignty. (Trump has threatened to send “the military” to the US-Mexico border, but the only option that appears to have been seriously discussed in is sending additional National Guard troops to the border.)

As far as Donald Trump is concerned, though, the failure of the governments of Guatemala and Honduras (and, somehow, El Salvador) to stop the caravan from leaving their countries is an insult to the United States — and a reason to slash foreign aid to those countries.

Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador were not able to do the job of stopping people from leaving their country and coming illegally to the U.S. We will now begin cutting off, or substantially reducing, the massive foreign aid routinely given to them.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) October 22, 2018

Agencies say they haven’t received any guidance over foreign aid cuts. And plenty of key Trump administration officials believe that the only way to reduce emigration from Central America to the US is to invest more in Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador.

Trump does not buy into this narrative. In a February speech, he said that the governments of Mexico and the Northern Triangle are “not our friends” — and that the US was getting played for a fool by sending them millions of dollars in aid.