#captain marryat: seaman writer and adventurer

Text

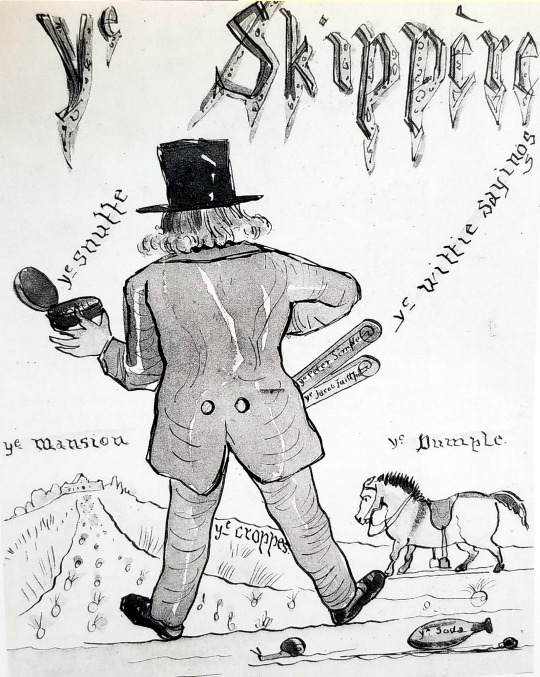

YE SKIPPÈRE

With artistic credit to Frank Marryat, one of the Captain's sons: an utterly ridiculous 1840s portrait of Frederick Marryat at home in Langham, Norfolk where he spent his last years.

This isn't the first time I've shared Frank Marryat's art, he also drew "A Happy Family." Both pictures are reproduced in Tom Pocock's book Captain Marryat: Seaman, Writer, and Adventurer—but only in the print version, not the ebook—and are printed in greyscale, although they may have originally been in colour. The source is given as the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, but I can't find any references on the NMM website.

In the spirit of Eighteen-Forties Friday, Frank's artwork of his father demonstrates that 1840s pop culture was not only fascinated with medieval aesthetics: they could also spoof it in Ye Olde Memes. Marryat holds "ye snuffe" tobacco in one hand, and "ye Peter Simple" and "ye Jacob Faithful" represented as scrolls in his pocket are "ye wittie sayings." He has ye mansion (Langham Manor Cottage, no longer standing), ye croppes, and ye Dumple—his slightly notorious pet horse, Dumpling.

And there is literally a snail. (You can't have medieval marginalia without one!) The bottle of "ye soda" on the ground was unexpected, but soda fountains in pharmacies existed at the time, and sweetened carbonated beverages as well as mineral waters were commercially produced and sold in the early 19th century.

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#1840s#Eighteen-Forties Friday#frank marryat#marryat family#victorian#medieval memes#early victorian era#biography#tom pocock#captain marryat: seaman writer and adventurer#frank drew another pseudo-medieval pic of one of marryat's friends in langham#rip frank marryat you would have loved the internet

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

I want to write about Captain Marryat and his talent with foreign languages, because there was a time when I genuinely wondered if he was some kind of multilingual genius.

There is a trend of his characters learning to speak a second language conversationally in a matter of months (e.g. Willy Seymour learning French in The King's Own, and Jack Easy learning Spanish in Mr. Midshipman Easy). Marryat himself was known for confidently touring Europe, speaking multiple languages to the locals. His biographer Tom Pocock wrote, "he was a linguist, speaking French, Italian and Spanish", and he taught his daughters Italian (Captain Marryat: Seaman, Writer, and Adventurer).

Florence Marryat does not speak on the quality of her father's language lessons in his Life and Letters; but the anonymous friend of the Captain who published "Captain Marryat at Langham" in The Cornhill Magazine doesn't hold back:

There was hardly a modern language of which he had not some knowledge; grammatical knowledge, I mean. So far as speaking them went, although he would rattle off unhesitatingly French or German, or Italian, or whatever was called for at the moment, his thoroughly British tongue imbued them all with so much of the same accent, that it was difficult to know what the language was meant for: indeed, he used to tell a story of how an Italian, after listening to one of his long speeches in his purest Tuscan, apologized to him and said he did not understand English.

— "Captain Marryat at Langham," The Cornhill Magazine, August 1867 (full text on Google Books)

This really sounds like biggest self-own, but one of Marryat's better qualities was his ability to poke fun of himself. And there's the answer: Marryat wasn't exceptionally gifted at acquiring new languages, but he was supremely confident at using his limited skills. The complete opposite of most second language speakers, who feel ashamed for having a slight accent or lacking total mastery of their second language. To all of you language learners: may you have a fraction of Captain Marryat's self-confidence!

The reference to Marryat having a terrible accent in his non-native languages also fits with his writing style. He loved to spell out the accents of lower-class or foreign characters (the better to make fun of them), but other than his insider knowledge of a lower-class London accent he never seems to do a very convincing job. Whether the character is British, American, Caribbean, whatever, it's always Talk Like A Pirate Day and they're going to say "sar" instead of "sir." The sarvice, sarve her out, old-country sarpents. And a few words of Irish or West Indian dialect for localisation if he's being thorough.

Marryat could probably make himself understood in French since he spent so much time in France and francophone Belgium. Amusingly enough, an 1826 letter from Marryat in the collection of the New York Public Library is described as being written "in poor French."

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#biography#language#life and letters#captain marryat at langham#tom pocock#captain marryat: seaman writer and adventurer#english literature#british literature#local englishman unfazed by foreigners staring at him in mute incomprehension

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Throughout that stormy winter [of 1806], Marryat was recording this almost daily in his log: ‘Engaged a battery and took two prizes … engaged a battery and received a shot in the counter … anchored and stormed a battery … trying to get a prize off that was ashore, lost five men.’ Daily, Marryat heard the drums beat to quarters and the squeal of the boatswain’s calls as the ship’s company made or took in sail, ran out the guns and manned boats. As he put it, he thrilled to ‘the rapidity of the frigate’s movements, night and day; the hasty sleep, snatched at all hours; the waking up at the report of the guns, which seemed the only key-note to the hearts of those on board; the beautiful precision of our fire … the coolness and courage of our captain.’

— Tom Pocock, Captain Marryat: Seaman, Writer, and Adventurer

Man of War in Torbay, by Thomas Luny, 1809.

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#age of sail#naval art#biography#napoleonic wars#thomas luny#man of war#tom pocock#royal navy#maritime art#midshipman marryat

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Heir to the ninth Earl of Dundonald, but to no fortune, Thomas Cochrane had already made his own at sea. That same year, soon after Nelson’s funeral, he had brought his frigate, the Pallas, into Plymouth Sound, after a successful cruise, with three golden candelabra lashed to her mastheads. He was even more famous for his capture of a Spanish frigate with a little sloop he had commanded, boarding the enemy and bringing her into Gibraltar with two hundred and sixty-three prisoners below deck. [...] A word from Joseph Marryat to Cochrane and the latter agreed to take the former’s son to sea with him as a first class volunteer.

— Tom Pocock, Captain Marryat: Seaman, Writer, and Adventurer

The Action and Capture of the Spanish Xebeque Frigate 'El Gamo' (detail) by Clarkson Stanfield c. 1845.

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#lord thomas cochrane#age of sail#thomas cochrane#napoleonic wars#earl of dundonald#clarkson stanfield#naval art#el gamo#hms speedy#lord cochrane#biography#tom pocock

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

By an irony of fate, which would not have escaped Captain Marryat, his first chance of high command on active service came nearly eight years after the Great War had ended. On 31 March 1823, he was appointed to command the Larne, a small, fir-built frigate of 20 guns, hurriedly ordered for operations off the American coast in the War of 1812; her size suited the work the Admiralty had in mind.

India and what were known as the East Indies were increasingly seen as replacing the West Indies as the principal source of overseas profit. The threat to this from France had been eliminated but there was another, which, once removed, could present vast opportunities for trade and the exploitation of natural resources.

— Tom Pocock, Captain Marryat: Seaman, Writer, and Adventurer

H.M.S. Larne, H.C. Cruizer Mercury, Heroine, Carron & Lotus, Transports attacking the Stockades at the entrance of Bassein River, on the 26th Feby 1825, 1826 print after a sketch by Captain Frederick Marryat.

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#age of sail#royal navy#first anglo-burmese war#1820s#biography#naval art#marryat's artwork#hms larne#tom pocock#naval history

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Americans have reason to be proud of their women, for they are really good wives—much too good for them; I have no hesitation in asserting this, and should there be any unfortunate difference between any married couple in America, all the lady has to say is, “The fact is, Sir, I’m much too good for you, and Captain Marryat says so.” (I flatter myself there’s a little mischief in that last sentence.)

— Frederick Marryat, Diary in America

I had to laugh at "a little mischief"—as if Marryat wasn't involved in a public scandal with a married woman during his American tour. As described by his biographer Tom Pocock in Captain Marryat: Seaman, Writer, and Adventurer:

Returning to Louisville in mid-September [1838], he, for the first time, became embroiled in a sexual scandal. There he met a Mrs Collyer, the flirtatious wife of a phrenologist, a couple who were staying at the same hotel. The husband’s jealousy was so aroused that he announced that he would be away for the night, then furtively returned to their room and hid under the bed. At one o’clock next morning, his patience was rewarded by the arrival of his wife and the captain in night attire. At this the phrenologist emerged from hiding, shouting, ‘Fire!’, ‘Rape!’, ‘Treason!’ and attacked Marryat, while the wife collapsed, weeping, on the bed. When the hotel manager and most of the other guests crowded into the room, Marryat protested that he had heard Mrs Collyer was adept at the treatment of sprained joints and he had been seeking her ministrations for this. The story appeared in the local newspaper and litigation seemed certain. Then, surprisingly, the wronged husband wrote to the newspaper that he himself had been under the influence of drink that night and had misunderstood Marryat’s intentions. Few believed him and a theory circulated that he had withdrawn his charges in order to avoid a duel.

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#diary in america#biography#tom pocock#1830s#captain marryat: seaman writer and adventurer#treason?? lmao is this because marryat is british#also 'fire'(??)

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some years ago, I bought a first edition of [Marryat's] first novel, The Naval Officer, or Scenes and Adventures in the Life of Frank Mildmay, at a second-hand bookshop in Paris and was surprised by what I read. It was not only that his descriptions of sea and war and people were so vivid but the character of the hero was so unexpected. In 1829, when it was written, most such stories were of ordeals survived, problems solved and virtues rewarded. In this case the hero was an unpleasant young man, selfish and ruthless, yet he still triumphed in the end.

— Tom Pocock, Captain Marryat: Seaman, Writer, and Adventurer

A Man-of-War at Sea, British School 19th century.

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#age of sail#tom pocock#biography#frank mildmay#captain marryat: seaman writer and adventurer#english literature#british literature#frank mildmay is so underappreciated#both the book and the character

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Naval historian Tom Pocock on Frederick Marryat's home near Langham, Norfolk, where he spent most of the 1840s, and his last years:

When Marryat finally arrived, he was enchanted. The house stood on a low ridge two miles from the coast and three from the open sea beyond Morston salt-marshes and the sand-dunes of Blakeney Point. It was sheltered by a belt of trees, surrounded by gardens and woodland – ‘pleasure grounds, shrubberies and plantations’ – and some seven hundred acres of farmland, with coach-houses, barns and cottages nearby; from the house, his land stretched half a mile to the village of Langham and its fourteenth century church. Despite its mock-cottage appearance, it was a roomy house with handsome reception rooms opening on to a terrace, four large bedrooms upstairs and four more for the children and guests. From the windows could be seen the sea to the north and, to the south, across the shallow valley of the little Stiffkey river, the billowing treetops along the ridge beyond. He determined to make this his home, staying at his mother’s house at Wimbledon when visiting London.

— Tom Pocock, Captain Marryat: Seaman, Writer, and Adventurer

Blakeney, Norfolk, by Archibald David Reid (1844–1908)

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#biography#norfolk#england#1840s#marryat's house is now gone#also his mother outlived him#tom pocock#captain marryat: seaman writer and adventurer#archibald david reid

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

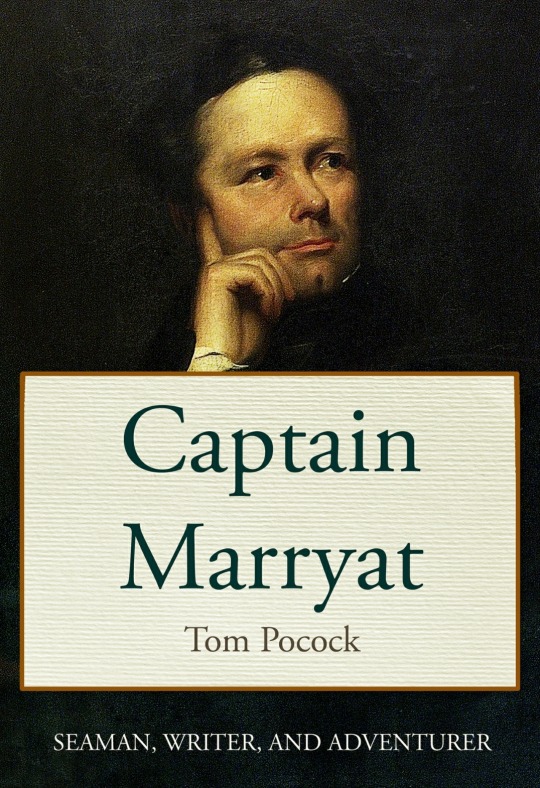

Although I already own this book in a hardcover print version, I just bought the Kindle edition of Tom Pocock's Captain Marryat: Seaman, Writer, and Adventurer. It was only $3.99, and I love having searchable, electronic copies of favourite books. I recommend Pocock's biography of Frederick Marryat, it's a lively and captivating read (and Marryat's most recent biography).

The graphic design of the Kindle edition cover is more appealing than the original print edition. Instead of the more familiar painting of Marryat by John Simpson on the cover, it has the underrated and charming portrait by E. Dixon. I have written about this portrait, and how well it seems to capture Marryat's appearance and personality as his daughter described him.

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#tom pocock#captain marryat: seaman writer and adventurer#biography#portrait#british literature#english literature#naval history#maritime history

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

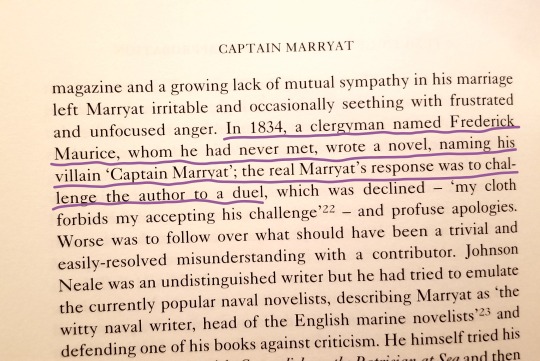

I would name the villain in my novel "Captain Marryat" HOPING the real Captain Marryat would challenge me to a duel omg

#captain marryat#frederick marryat#age of sail#nautical fiction#tom pocock#captain marryat: seaman writer and adventurer#biography#as much as i love marryat i am often reminded of why i would fight him#lmao

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

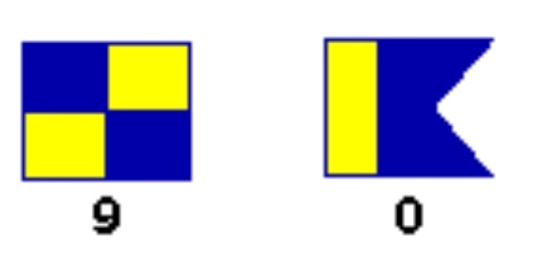

Signalling her number

William John Huggins (1781-1845), A Frigate Signalling Her Number Off Ramsgate.

This painting is a current listing on the marine art auction market, brought to my attention by a person who regularly scours auction sites. I can't find any additional information on Bonhams besides the title, and the lifespan of the artist (so we know that this was made in 1845 or earlier).

She flies the Red Ensign, also known as the "Red Duster", of the British merchant navy. The flags at her foremast and mainmast are from Captain Marryat's Code of Signals.

First Distinguishing Pennant: this shows that she is signalling the number of a merchantman. Other distinguishing pennants or flags would be used to express places, bearings, or sentences from Marryat's code. @ussporcupine demonstrated how Marryat's flags were used to send messages in AMC's Franklin expedition TV series, 'The Terror'. Even Royal Navy ships would use Marryat's code—and a Franklin expedition officer posed with a copy of Marryat's signal book, which might explain why the TV series chose to employ it.

So the numerical flags in Huggins' painting are a merchant ship:

This is 4230 or 4239. The last flag is slightly obscured, and I have tried reading it as both a zero or a nine:

If it were a 9, the upper left corner would be blue, not yellow, which is not what the painting appears to show. If it was important enough for the ship's owner to commission this painting, you would think that the artist would take care to show the correct signal flags.

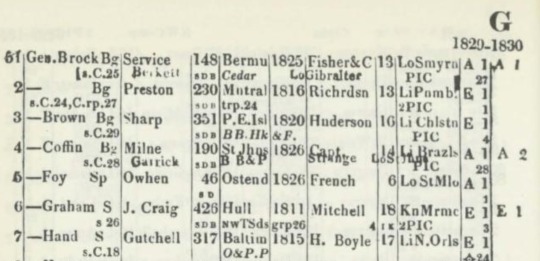

The earliest edition of Marryat's Code of Signals online is from 1847 (Google Books link), which is a potential problem. If this ship was wrecked soon after 1845 (or even earlier, since the painting is undated), the corresponding merchant ship number in the 1847 edition wouldn't be her. But it's the best reference I have, and I looked up merchant ships using the first distinguishing pennant (the second pennant was also used for merchant ships, but that's not ambiguous here):

General Brock? Like Sir Isaac Brock? (The indentation appears to function as a "ditto"). Conveniently on the same page, merchant ship 4239 is General Graham. The list of ships is from Lloyd's Register, a company which is still around today, and they have their historical records online.

The connection between Captain Marryat and his Code of Signals and the powerful Lloyd's Register is not an accidental one. Joseph Marryat Sr., Frederick Marryat's father, happened to be both a Member of Parliament and an important board member at Lloyd's, which didn't go unnoticed at the time the Code of Signals was first published in 1817:

Urged on by his father, Marryat devised his Code of Signals for merchant shipping, which could be employed in parallel with naval signals. It divided into six parts: the first two, lists of warships and merchantmen, each identified by a number; thirdly, signals representing named ports, headlands, channels and reefs; fourth, signals for sentences commonly used at sea; finally a section for vocabulary and another for the alphabet. Published in 1817, it was promoted by Joseph Marryat, through his influence at Lloyd’s, prompting the sour comment from one ship-owner that, ‘When it is considered that Captain Marryat is the son of the chairman of the Committee of Lloyd’s, I am sure the ship-owners and the public will do every justice to the very ingenuous manner in which it has been brought forward.’ But influence, or ‘interest’, as it was known in the Navy, was one of the principal driving-forces of society and was taken for granted. Once the new code had been accepted by Lloyd’s, all its insurance agents, every ship-owner, the master of every merchantman, every pilot, coastguard and excise officer and soon every warship had to have a copy. Its success, both practical and commercial, was assured.

— Tom Pocock, Captain Marryat: Seaman, Writer, and Adventurer (2000)

So far, my attempts to cross-reference this ship in Lloyd's Register have yielded confusing results. The 1847 edition, which should match up with the Code of Signals I used, doesn't have a General Brock or General Graham. But both names are in the 1830 edition.

Here General Brock is identified as a brig (Bg), which is a two-masted vessel and can't be the ship in the painting. s.C. means copper sheathed. General Graham is a ship (S), and the most likely candidate at this point. Both vessels are 'SDB' or single deck with beams.

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#age of sail#code of signals#naval art#william john huggins#naval history#lloyd's register#merchant navy#frigate#maritime signal flags#joseph marryat#tom pocock#about to pretend i have £5000 lying around so i can get more info on this painting lol

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Captain Marryat, Man of Fashion (and Jewellery)

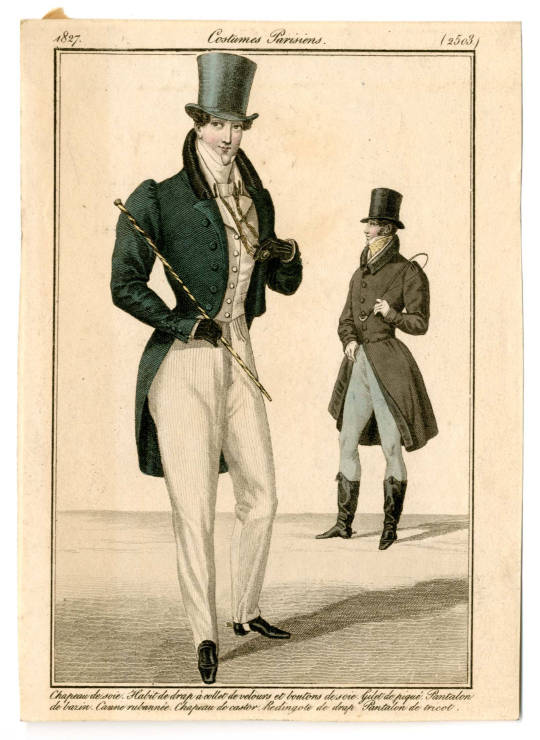

In this engraving, based on his 1827 portrait by William Behnes, Frederick Marryat is a gentleman-in-waiting to the Duke of Sussex. "He had become a fashionable captain," Tom Pocock writes of this time in his biography, Captain Marryat: Seaman, Writer, and Adventurer.

Throughout the 1820s and 1830s, Marryat moved in fashionable society, socialising with the luminaries of his day. At his London residence at 3 Spanish Place—which has his blue plaque today—Alan Buster notes that "he received Dickens, Forster, Ainsworth, Bulwer and other literary notables, as well as painters and navy men." (Captain Marryat: Sea-Officer Novelist Country Squire) Among his friends in the literary circle of Lady Blessington was Alfred d'Orsay: the famous dandy, man of fashion, and amateur artist (d'Orsay also sketched Marryat).

I think it goes without saying that Marryat can be regarded as something of an authority on the fashionable man of the early 19th century, even if it's not what he is primarily known for. His heroes are often fashion-conscious, like Frank Mildmay, who "perceived that the best-dressed midshipmen had always the most pleasant duties to perform."

Details on the fashionable man's attire in Marryat's novels are more scarce. An offhand reference to a watch and seals in Peter Simple was eye-opening to me, but he usually doesn't describe costume details. The most fashion-focused Marryat novel is arguably Japhet in Search of a Father. The title character moves between high society and low, in diverse groups, and along the way he needs many changes of costume. ("Costume" is a good word for Japhet, a clever schemer who pretends to be a young nobleman despite his humble origins).

Japhet has a solid grasp of style on his own, but he blossoms under the tutelage of Major Carbonnell, a notoriously well-dressed rake. Japhet describes him:

He was tall and well made, and with an air of fashion about him that was undeniable. His linen was beautifully clean and carefully arranged, and he had as many rings on his fingers, and, when he was dressed, chains and trinkets, as ever were put on by a lady.

Carbonnell hooks up Japhet with his personal tailor, and he also takes him shopping for masculine jewellery. This is particularly interesting to me, because period fashion plates do not necessarily provide much information about accessories, and I feel like the historical fashion guides I have read take pains to emphasize that 19th century men wore minimal jewellery. (The entire 19th century consists of somber late Victorians, apparently).

Carbonnell is not only loaded with jewellery, he gives specific advice on how much to buy:

"Don't you want some bijouterie? or have you any at home?"

"I may as well have a few trifles," replied I.

We entered a celebrated jeweller's, and he selected for me to the amount of about forty pounds. "That will do—never buy much; for it is necessary to change every three months at least. What is the price of this chain?"

"It is only fifteen guineas, major."

"Well, I shall take it; but recollect," continued the major, "I tell you honestly I never shall pay you."

The jeweller smiled, bowed, and laughed; the major threw the chain round his neck, and we quitted the shop.

"Chains" and "bijouterie" are two distinct things. ("'You, sir,' replied the governor, surveying my fashionable exterior, my chains, and bijouterie.") The chains are presumably for pocket watches, seals, or perhaps around the neck for a quizzing-glass, like this gentleman in an 1827 fashion plate:

(Source: Metropolitan Museum of New York.)

The other bijouterie are rings, trinkets, pins, jewelled brooches and clasps. Japhet refers to his diamond solitaire ring as a piece of bijouterie.

It is difficult to find either portraits or fashion plates that display the quantity of jewellery that Marryat's Major Carbonnell recommends. Using a historical currency converter for 1836, the last year Japhet in Search of a Father was serialized, £40 is equivalent to $5287.64 current USD, and fifteen guineas is equal to $2082.01. Carbonnell advises spending a small fortune on a man's jewellery—and changing it out for new styles every three months!

I greatly appreciate this c. 1832 portrait of the fashionable José María Benítez Bragaña, by the Spanish artist Rafael Tejeo:

(Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Bragaña is in the right time period for Japhet (which is set in the "present day" i.e. early 1830s), and he even has a luxurious amount of chains! (How many trinkets does he have attached to those things?!) Sadly, his hands are tucked out of sight, so we can't assess his rings.

It's true that Carbonnell is flamboyant, and not intended to represent the average man any more that the colourful boatswain Mr. Chucks of Peter Simple, who also loves jewellery. But Marryat endorses a healthy amount of bijouterie even on his most heroic, traditionally masculine characters, like the smuggler Jack Pickersgill of The Three Cutters.

Jack Pickersgill is introduced as "remarkably handsome, very clean, and rather a dandy in his dress." He aspires to eventually quit smuggling, after he has made his fortune, and reappear in society as a gentleman. He avoids smoking and drinking and remains scrupulously clean and polite, but his men respect his competence and skill:

He keeps his hands clean, wears rings, and sports a gold snuff-box; notwithstanding which, Jack is one of the boldest and best of sailors, and the men know it. He is full of fun, and as keen as a razor.

Finally, a portrait detail of a Royal Navy officer, c. 1847-57, showing his gold rings with square-cut sapphires and an elongated baroque pearl. (Source: NMM) If the identification of the sitter as Captain Joseph Nias is correct, he is contemporary with Marryat and almost the same age.

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#historical fashion#men's fashion#1820s#1830s#historical men's fashion#jewellery#jewelry#fashion history#biography#japhet in search of a father#peter simple#frank mildmay#the three cutters#masculinity#bijouterie#fashion

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Captain Marryat sketched by George Cruikshank, and Florence Marryat photographed c.1870.

Catherine Pope's biography Florence Marryat makes father and daughter sound very much alike: their heavily autobiographical fiction, spirited defiance of convention, somewhat scandalous personal lives, and apparently, being perceived as physically intimidating.

Tom Pocock wrote of Frederick Marryat's "formidable physical presence – broad shoulders, deep chest – and a hint of lurking violence", and at one point stated that one of Marryat's commanding officers was "wary of Marryat, who was strongly built and had a dangerous glint in his eye." (Pocock, Captain Marryat: Seaman, Writer, and Adventurer)

In comparison, here's Pope on the Captain's daughter:

She was an imposing figure, both physically and professionally, and letters from her male contributors show deference and respect. Edmund Downey, assistant to Marryat's publisher William Tinsley, was warned: "She is a tall, striking-looking woman, and she'll talk to you just like a man."

— Catherine Pope, Florence Marryat.

It's a wonderful glimpse at the talented, determined writer who assembled the most important primary source of her father's biographies, The Life and Letters of Captain Frederick Marryat.

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#florence marryat#biography#tom pocock#catherine pope#being 'warned' about florence marryat that way!#i suppose for a victorian man it was shocking#life and letters#english literature#british literature#victorian#victorian women writers#literature#marryat family

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

As the prospect of war—with the United States in alliance with France—darkened, Midshipman Marryat was, in November 1811, appointed to another frigate, the Spartan, commanded by another such officer as he would himself have chosen. Captain Edward Brenton had succeeded his brother Jahleel in the command and both were gentlemen of literary tastes as well as fighting captains. The Brentons belonged to an American loyalist family and this was a bond with Marryat as Edward Brenton recognised the boy’s latent qualities and encouraged them. The captain was, declared Marryat, ‘refined in his manner, a scholar and a gentleman. Kind and friendly with his officers, his library was at their disposal; the fore-cabin, where his books were kept, was open to all; it was the schoolroom of the young midshipmen and the study of the old ones. He was an excellent draughtsman and I profited not a little by his instruction.’ Marryat, profiting by this and the former influence of Captain Webley, had begun to amuse himself and his messmates with caricatures and he added what was, for him, becoming a new and exciting interest: ‘He loved the society of ladies and so did I.’

— Tom Pocock, Captain Marryat: Seaman, Writer, and Adventurer

I think this passage from Pocock's biography of Frederick Marryat is accurate, when it comes to describing the relationship between Midshipman Marryat and Captain Brenton, but the quotes are from the (admittedly very autobiographical) novel Frank Mildmay (The Naval Officer). Throughout his biography, Pocock uses quotes from Marryat's novels to stand in for the experiences of Marryat himself.

It's part of a long tradition of parsing Marryat's writing as reflecting his own experiences (and his daughter lends a lot of support to this in her father's Life and Letters), but not without pitfalls. His novels are works of fiction, even though they often draw from his lived experiences.

Frank Mildmay, in particular, describes Marryat's experiences in the War of 1812 off the coast of New England and Maritime Canada (awkwardly, his mother's family of American loyalists lived in the same areas targeted by the Royal Navy). As much as it flatters Marryat with Mildmay being a handsome officer who has every girl in Halifax swooning over him, it leaves out some of his most truly heroic acts.

It was up to Captain Joseph Pierce of the privateer Ida, American War of 1812 veteran and former prisoner of war, to recount how Lieutenant Mildmay defied the orders of his tyrannical captain to bring necessary supplies and comforts to American prisoners. Captain Lord Stuart ("his lordship" of Frank Mildmay) had forbidden his officers from so much as communicating with the American prisoners of war, and only Marryat defied him. It took real bravery to do that.

Frank Mildmay is a heartbreaker and a rogue who in some ways is more appealing and heroic than the real Captain Marryat, but Marryat also made his self-insert character more selfish and cold-hearted. There is a distance between Marryat's fiction and his real life.

HMS Spartan at Quebec, Heights of Abraham, original drawing by Captain Edward Brenton, 1818. Marryat might have been present in the original scene that his former captain captured in this work of art.

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#age of sail#royal navy#war of 1812#hms spartan#frank mildmay#biography#tom pocock#reading marryat#edward pelham brenton#edward brenton#naval art#maritime art#military history

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joseph Marryat tried to plan his sons’ futures. There would be no problem over the eldest, Joseph; as his heir, he would inherit money and property and so could indulge his interest in art, notably porcelain. Frederick was different, but he had shown interest in a life at sea, which would not only keep the troublesome boy out of the way but, if he survived, could present the opportunities for making a fortune in prize-money, freelance cargo-carrying and the other means by which naval officers could supplement their pay.

— Tom Pocock, Captain Marryat: Seaman, Writer, and Adventurer

The Frigate 'Triton' (detail), Nicholas Pocock, 1797

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#age of sail#royal navy#biography#tom pocock#nicholas pocock#yes they're actually related#frigate#naval art#marryat family#joseph marryat jr also wrote a book about collecting porcelain#the whole gigantic family writes books#joseph marryat

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Captain Marryat the naturalist

In the same year as his marriage [1819], Marryat became a Fellow of the Royal Society. This was due to his friend [Charles] Babbage, who was his proposer. As may be imagined, the distinction did not then approach its present grandeur, but Marryat was rightly proud of it.

— Oliver Warner, Captain Marryat: A Rediscovery

Frederick Marryat was keenly interested in the natural world. The study of the wading bird is his own artwork, now in the collection of the British Museum. Before his first command in 1820, Marryat even identified a new genus of marine gastropod molluscs by the type species Cyclostrema cancellatum, a dainty animal of the Caribbean Sea.

The surgeon and naturalist Macallan of The King’s Own has a part of his author in him, waxing poetic about ocean-going gastropods; Marryat even comments on pelagic shells in a footnote to “correct” his character’s ignorance, since the novel is set in an earlier time period.

“What shell is this, Mr. Macallan, which I have picked up? It floated on the surface of the water, by means of these air bladders, which are attached to it.”

“That shell, Willy,” replied Macallan, who, mounting his favourite hobby, immediately spouted his pompous truths, “is called, by Naturalists, the ianthina fragilis, perhaps the weakest and most delicate in its texture which exists, and yet the only one which ventures to contend with the stormy ocean. The varieties of the nautili have the same property of floating on the surface of the water, but they seldom are found many miles from land. They are only coasters, in comparison with this adventurous little navigator, which alone braves the Atlantic, and floats about in the same fathomless deep which is ranged by the devouring shark, and lashed by the stupendous whale. I have picked up these little sailors nearly one thousand miles from the land."

— Frederick Marryat, The King's Own

(In a footnote, Marryat states, “I am aware that there are two or three other pelagic shells, but, at the time of this narrative, they were not known.”)

Frederick Marryat was a childhood friend of the famous mathematician Charles Babbage, they attended the same school at one point and remained life-long friends. Babbage suggested that Marryat should also be elected to the Astronomical Society, “for which there would be some justification through his professional skill in navigation,” Tom Pocock wrote in Captain Marryat: Seaman, Writer and Adventurer.

If Marryat’s later career was busy with his novels and other projects, he enjoyed educating children when he had the opportunity, as his daughter Florence described it:

His knowledge of nature was most extensive, and he might often be seen surrounded by an audience of delighted little ones, listening with open eyes and mouths to his descriptions of the wonders of the deep or the natural history of the creation.

— Florence Marryat, The Life and Letters of Captain Frederick Marryat

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#age of sail#fellow of the royal society#natural history#naturalist#marryat's artwork#life and letters#biography#oliver warner#tom pocock#the king's own#macallan is said to be a big inspo for patrick o'brian's dr maturin

75 notes

·

View notes