#clint's letter

Note

What do you think Clint’s letter was like in “last wish” and his reaction to her death

Oooooo I actually thought a lot about this while building the story, sooooo..........

here's a little drabble in bullet format :)

Clint's Letter

words: 850

If you haven't read Last Wish, you should probably read it first :)

Clint tried to call you immediately after getting off the phone with Wanda.

When you didn't answer, worry gnawed at his stomach.

He immediately grabbed his keys.

He’s almost there when Bruce calls and tells him to come to the compound.

When he got there, Clint saw Nat sitting in the common area with her head in her hands.

He was actually happy to see her for like 0.0001 second before he realized she was crying...

crying like she did when Wanda was dusted

His heart falls to his stomach. He’s too scared to ask.

Bruce enters with a very broken Wanda lingering in the doorway.

“Where is Y/n?”

No one speaks. The two women only cry harder at the sound of your name.

“Where is my sister?!?!”

Bruce is the one to answer him, "she brought Nat back.”

"How?"

The green gentle giant looks up regretfully, "she traded herself."

Clint turns to the widow.

All she can say between sobs is “I’m sorry.” She repeats it over and over again. "I'm so sorry."

He shakes his head in disbelief, “no.”

He didn't want to believe it. You wouldn't leave him. You wouldn't leave your family.

Would you?

But here Nat is, and Clint knows the constant, excruciating pain you have felt since you came back with the soul stone.

Pain tears through his body as the reality of the situation sinks in.

You're gone.

His baby sister, his teammate, his partner at game night, his best friend, all gone.

As quick as it came, the pain melted in unfiltered rage. He turns to Wanda standing in the doorway,

and the screaming begins...

"YOU DID THIS!"

"You resented her from the moment you came back!"

"What did you say to her?!"

"SHE LOVED YOU, and you hated her!"

"HOW COULD YOU DO THAT TO HER?"

"She did this for you! YOU MADE HER DO THIS!!!"

"ARE YOU HAPPY NOW!?!?!"

Bruce has to grab him before he does something he can't take back.

"If I ever see you again-"

Bruce drags him out of the room to cool off.

Once they're alone in the conference room, Clint collapses onto the floor. Lying on his back, he stairs up at the ceiling.

Grief overcomes him, and he sobs, crying your name every so often.

Eventually, he works up the courage to go home with your unopened letter shoved in his pocket.

He refuses to read it.

Reading it means accepting them as your final words, and he's not ready to do that.

He wants to destroy the letter, but you wrote it for him. It's the last thing you'll ever write for him.

So, he tosses it in a drawer in his bedroom and leaves it there.

... until the day Nat shows up on his doorstep looking for a place to stay.

She tells him about the fight, about the memory Wanda shared, about the guilt and pain on your face when Wanda blamed you for Natasha's death.

How nothing is worse than the moment Wanda said she'd trade you for Nat.

She tells him about your letter to her. How she's trying to honor your wishes by forgiving the witch, but she's not sure she can.

Clint's anger returns, but more so, does the pain.

The regret of knowing you were hurting so much, and there was nothing he could have done to stop it.

That night, he finally opens your letter.

There are so many "I'm sorry"s.

Sorry for leaving him. Sorry for not being strong enough. Sorry for not telling him your plans. Sorry for not saying a proper goodbye.

There are equally as many "thank you"s.

Thank you for being my big brother. Thank you for being my friend. Thank you for always being there when you needed him.

Then you make a request.

You ask him not to blame Wanda. You love her deeply, and you made this decision, not her.

You ask him to look after your girls. You don't want them to be alone. You want them to be happy together. You plead for him to help them get through this.

You end with an "I love you" and "until we meet again"

Clint cries that night..... and for several nights after that.

but he makes a promise to do as you ask.

He starts with Natasha, building her back up while she stays with him. He can't fill the hole that's missing, but he can help her learn to live with it.

Several times he tries convincing her to reach out to Wanda, but every time, she says that she is not ready yet. He respects that.

Eventually, he works up the courage to check on Wanda himself.

It's not easy, but she has to check that she's ok. He promised.

When he learns of her desperate plans, he runs home to get Nat. She's the only one that can pull Wanda out of this.

He's the one to finally convince her to go back to the house.

He's the one to bring them back together.

Now, for the really hard part:

the healing,

and he'll help them through that too.

#wandanat x reader#barton!reader#clint barton x reader (siblings)#last wish#clint's letter#grief#mourning#loss#wanda x reader#natasha x reader#wanda x natasha#wandanat#fem!reader#angst#all the angst#with a happy ending?#this is sad#grab a tissue#avengers#natasha romanoff#wanda maximoff#clint barton#bruce banner#wanda x nat x reader#wanda x reader x natasha#askkate

135 notes

·

View notes

Text

[CITATIONS NEEDED]

#love Nat and all but I can't think of a single thing she's sacrificed for you!#and you helped natasha in your very last storyline together!#you tried to help her so many times that she had to write you a letter telling you to fuck off!#clint barton#black widow & hawkeye#yet another unearned dynamic pulled out of thin air for them

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

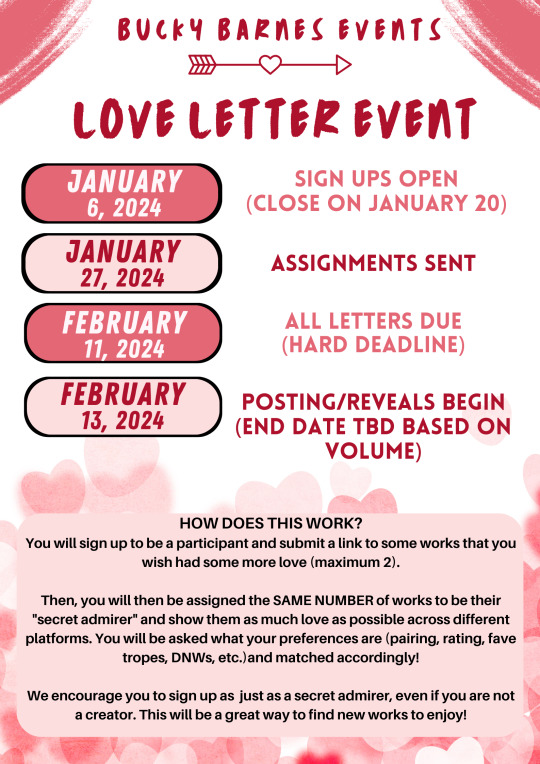

Valentine's Day will soon be upon us! What better way to spend it than by spreading some love?

Sign Up Forms: https://forms.gle/5EU3wR5rPcehLb6C9

Notes:

This event falls under our blanket rules as well, so please ensure you read those first.

While you can submit any works of your choosing, please be aware that we cannot guarantee a match up if your works fall under a more niche category. We will do our best to reach out and have you resubmit your sign up if we cannot find a match for you.

Of course, you don't have to sign up for an event to show your appreciation for your readers or content creators - be sure to tell them you love them any day you can!

#bucky barnes events#bucky barnes#bucky barnes fanfiction#bucky barnes fanart#bucky barnes fanworks#fandom event#valentines day#bucky barnes x reader#bucky barnes x natasha romanoff#bucky barnes x steve rogers#bucky barnes x clint barton#bucky barnes x tony stark#bucky barnes content#bbe love letters 2024#bbe valentines event 2024

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Bridges of Madison County (1995)

#the bridges of madison county#clint eastwood#meryl streep#film#movies#cinematography#romance#drama#letter#poetry#byron

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

'The key word in Christopher Nolan’s “Oppenheimer” is “compartmentalization.” It’s a security strategy, introduced and repeatedly enforced by Col. Leslie R. Groves (Matt Damon) in his capacity as director of the Manhattan Project, which is racing to build a weapon mighty enough to bring World War II to an end. In Groves’ mind, keeping his various teams walled off from one another will help ensure the strictest secrecy. But J. Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy), the brilliant theoretical physicist he’s hired to run the project laboratory in Los Alamos, N.M., knows that compartmentalization has its limits. The success of their mission will hinge not on isolation but on an extraordinary collaborative synthesis — of physics and chemistry, theory and practice, science and the military, the professional and the personal.

In the weeks since “Oppenheimer” opened to much critical acclaim and commercial success, Groves’ key word has taken on an unsettling new meaning. Compartmentalization, after all, is a pretty good synonym for rationalization, the act of setting aside, or even tucking away, whatever we find morally troubling. And for its toughest critics, many of them interviewed for a recent Times piece by Emily Zemler, “Oppenheimer” compartmentalizes to an outrageous degree: In not depicting the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, they argue, the movie submits to a historical blindness that it risks passing on to its audience. Nolan, known for crafting fastidiously well-organized narratives in which nothing appears by accident, has been taken to task for what he chooses not to show.

Most of those decisions, of course, flow directly from his source material, “American Prometheus,” Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s authoritative 2005 Oppenheimer biography. With the exception of one key narrative thread, everything onscreen is framed, per biopic convention, through its subject’s eyes. And so you see Oppenheimer as an excitable young physics student, and you behold his eerie, captivating visions of the subatomic world. You see him become one of America’s leading physicists, take a major role in the secret race to the A-bomb and, together with his recruits, devise and build the world’s first nuclear weapons. You see his shock and awe when the Trinity test proves successful, lighting up the desert sky and landscape with a blinding flash of white and a 40,000-foot pillar of fire and smoke.

What you don’t see — because Oppenheimer doesn’t see them either — are the bomb’s first victims: the thousands of New Mexicans, most of them Native American and Hispanic, who dwell within a 50-mile radius of the Trinity test site and whose exposure to radiation will have deadly health consequences for generations. You don’t see the bombs being dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki; you don’t see the lethal conflagrations and ash-covered rubble, and you don’t see the bodies of Japanese victims burned beyond recognition, or hear the screams and wails of survivors. (Estimates place the eventual death toll at close to 200,000.)

In refusing to visualize these horrors, is Nolan showing admirable dramatic restraint or committing unforgivable sins of omission? Is he merely sticking to his subject’s perspective or conveniently dodging the kind of imagery that would trouble Oppenheimer’s conscience?

As it happens, the scientist does in fact see that imagery, and his conscience is duly troubled. In one key scene, the camera studies Oppenheimer and his colleagues as they watch disturbing footage of the bombings’ aftermath. An offscreen speaker describes how thousands of Japanese civilians were incinerated in an instant, while thousands more died excruciating deaths from radiation poisoning. You see Oppenheimer recoil, even if what he recoils from is left pointedly out of frame.

These are not the only images of WWII that the movie withholds. It’s a measure of the formal and structural rigor of “Oppenheimer” that we see nothing of the Pacific theater conflict, and nothing of the European theater conflict, either — not even when Oppenheimer fears that the Nazis might be building a nuclear weapon of their own. Nolan, who always trusts us to keep up with his elaborately constructed puzzle-box narratives, also trusts us to know a thing or two about history. And crucially, he wants to open up a different perspective on the war, to show how some of its most crucial tactics and maneuvers played out not on battlefields but in classrooms and laboratories — and, finally, in the theater of Oppenheimer’s mind.

We are sometimes told, in matters of art and storytelling, that depiction is not endorsement; we are not reminded nearly as often that omission is not erasure.

It’s a brilliant mind, to say the least. It’s also ill prepared for the terrifying, world-altering reality that it ushers into being. Oppenheimer may see footage of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but images are a poor substitute for reality; he will never walk among the ruins, witness the despair of the survivors or behold the devastation up close. Nolan knows that we can’t either. What’s more, he clearly believes that we shouldn’t be able to.

Seen in this light, the director’s refusal to thrust his camera onto Japanese soil, far from being an act of historical vagueness or obliviousness, instead represents a carefully thought-out, rigorously executed solution to the problem of how to represent history. And his solution speaks not to his insensitivity but his integrity, his refusal to exploit or trivialize Japanese suffering by re-enacting it for the camera. Nolan lays the groundwork in one of his most revealing scenes, shortly before the decision is made to target Hiroshima and Nagasaki. As Oppenheimer looks on, U.S. Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson (James Remar) removes Kyoto from the list of potential targets, citing the city’s cultural and historical significance and fondly recalling that he and his wife honeymooned there years earlier.

Before the bombings have even taken place, Nolan, in this one scene, indicts the arbitrary callousness of a U.S. war machine that cloaks its destructive intentions in cultural high-mindedness and rank sentimentality. It’s an appalling moment, and Stimson unambiguously solicits Oppenheimer’s contempt as well as the viewer’s; watch that scene in a packed house and you’ll hear the audience scoff as one. You might also begin to suspect, if you haven’t already, that Nolan isn’t going to dramatize the bombings in straightforward fashion, if he means to dramatize them at all.

Nolan has never been turned on by spectacles of violence. Even “Dunkirk,” a harrowing if ultimately optimistic World War II bookend of sorts to “Oppenheimer’s” apocalyptic despair, is a combat picture far more driven by ideas than by carnage. Violence certainly plays its part in Nolan’s movies, but seldom is it an end in itself. Reviewing “Oppenheimer” in the New York Times, Manohla Dargis noted, “There are no documentary images of the dead or panoramas of cities in ashes, decisions that read as [Nolan’s] ethical absolutes.” And in a recent Decider essay, the critic Glenn Kenny shrewdly examined “Oppenheimer” alongside Alain Resnais’ elliptical 1959 masterpiece, “Hiroshima Mon Amour,” itself a powerful commentary on the futility of trying to represent the unrepresentable. “Had Nolan chosen to somehow ‘recreate’ the bombing of Hiroshima,” Kenny writes, “we, the viewers, would really see nothing.”

Japanese filmmakers, of course, have been powerfully evoking and re-creating the bombings for decades: Kaneto Shindo’s “Children of Hiroshima” (1952) and especially Shohei Imamura’s devastating “Black Rain” (1989) are just two well-known examples. Over the past few weeks, social media users have circulated clips of Mori Masaki’s 1983 anime “Barefoot Gen,” an adaptation of Keiji Nakazawa’s manga series of the same title. It contains what is surely one of the cinema’s most upsetting, unsparingly graphic depictions of the atomic blast and its casualties. It’s one of several animated films, including Renzo and Sayoko Kinoshita’s 1978 short “Pica-don” and Sunao Katabuchi’s “In This Corner of the World” (2016), that have confronted the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki with a boldness and artistry that live-action cinema can be hard-pressed to match.

Much of this evidence has been marshaled in Nolan’s defense: Surely this is Japan’s story to tell, not his. I’m reluctant to embrace that particular stay-in-your-lane logic, which is ultimately deadening to the cause of art and empathy. As Clint Eastwood demonstrated in “Letters From Iwo Jima,” it is not beyond a white Hollywood filmmaker’s ability to enter persuasively and movingly into the mindset of a wartime enemy. Even so, that clearly isn’t the story Nolan is telling. And with such a wealth and variety of Japanese fiction and nonfiction filmmaking on the atomic bombings already, why should “Oppenheimer” bear the responsibility of representing events and experiences that fall outside its subject’s perspective?

Some would rebut that “Oppenheimer,” being a Hollywood blockbuster with serious global reach (whether it will play Japanese theaters remains uncertain), will be many audiences’ only exposure to the events in question and thus might “create a limit on public consciousness and concern,” as the poet, writer and professor Brandon Shimoda told The Times. A corollary of this argument: The crimes committed against the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were so unspeakable, so outsized in their impact, that Oppenheimer’s perspective does and should dwindle into insignificance by comparison. For Nolan to focus so exclusively on an American physicist’s story, some insist, ultimately diminishes history and humanity, even as it reinforces the Hollywood hegemony of the great-man biopic and of white men’s narratives in general.

I get those complaints. I also think they betray an inherent disrespect for the audience’s intelligence and curiosity, as well as a fundamental misunderstanding of how movies operate. It’s telling that few of these criticisms of perspective were leveled at “American Prometheus” when it was published in 2005, that no one begrudged Bird and Sherwin for offering a meticulously researched, morally ambivalent portrait of their subject’s life and consigning the destruction of two Japanese cities to a few pages. That’s because books are books, the argument goes, and movies are movies — and this perceived difference, it must be said, reveals a pernicious double standard.

Because they seldom achieve the narrative penetration and richness of detail of, say, a 700-page biography, movies, especially those about history, often are hailed as achievements of breadth over depth, emotion over intellect. They are assumed to be fundamentally shallow experiences, distillations of real life rather than sharply angled explorations of it, propelled by broad brushstrokes and easy expository shortcuts, and beholden to the audience’s presumably voracious appetite for thrilling, traumatizing spectacle. And because movies offer a visual immediacy and narrative immersion that books don’t, they are expected to be sweeping if not omniscient in their narrative scope, to reach for a comprehensive, even definitive vantage.

Movies that attempt something different, that recognize that less can indeed be more, are thus easily taken to task. “It’s so subjective!” and “It omits a crucial P.O.V.!” are assumed to be substantive criticisms rather than essentially value-neutral statements. We are sometimes told, in matters of art and storytelling, that depiction is not endorsement; we are not reminded nearly as often that omission is not erasure. But because viewers of course cannot be trusted to know any history or muster any empathy on their own — and if anything unites those who criticize “Oppenheimer” on representational grounds, it’s their reflexive assumption of the audience’s stupidity — anything that isn’t explicitly shown onscreen is denigrated as a dodge or an oversight, rather than a carefully considered decision.

A film like “Oppenheimer” offers a welcome challenge to these assumptions. Like nearly all Nolan’s movies, from “Memento” to “Dunkirk,” it’s a crafty exercise in radical subjectivity and narrative misdirection, in which the most significant subjects — lost memories, lost time, lost loves — often are invisible and all the more powerful for it. We can certainly imagine a version of “Oppenheimer” that tossed in a few startling but desultory minutes of Japanese destruction footage. Such a version might have flirted with kitsch, but it might well have satisfied the representational completists in the audience. It also would have reduced Hiroshima and Nagasaki to a piddling afterthought; Nolan treats them instead as a profound absence, an indictment by silence.

That’s true even in one of the movie’s most powerful and contested sequences. Not long after news of Hiroshima’s destruction arrives, Oppenheimer gives a would-be-triumphant speech to a euphoric Los Alamos crowd, only for his words to turn to dust in his mouth. For a moment, Nolan abandons realism altogether — but not, crucially, Oppenheimer’s perspective — to embrace a hallucinatory horror-movie expressionism. A piercing scream erupts in the crowd; a woman’s face crumples and flutters, like a paper mask about to disintegrate. The crowd is there and then suddenly, with much sonic rumbling, image blurring and an obliterating flash of white light, it is not.

For “Oppenheimer’s” detractors, this sequence constitutes its most grievous act of erasure: Even in the movie’s one evocation of nuclear disaster, the true victims have been obscured and whitewashed. The absence of Japanese faces and bodies in these visions is indeed striking. It’s also consistent with Nolan’s strict representational parameters, and it produces a tension, even a contradiction, that the movie wants us to recognize and wrestle with. Is Oppenheimer trying (and failing) to imagine the hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians murdered by the weapon he devised? Or is he envisioning some hypothetical doomsday scenario still to come?

I think the answer is a blur of both, and also something more: In this moment, one of the movie’s most abstract, Nolan advances a longer view of his protagonist’s history and his future. Oppenheimer’s blindness to Japanese victims and survivors foreshadows his own stubborn inability to confront the consequences of his actions in years to come. He will speak out against nuclear weaponry, but he will never apologize for the atomic bombings of Japan — not even when he visits Tokyo and Osaka in 1960 and is questioned by a reporter about his perspective now. “I do not think coming to Japan changed my sense of anguish about my part in this whole piece of history,” he will respond. “Nor has it fully made me regret my responsibility for the technical success of the enterprise.”

Talk about compartmentalization. That episode, by the way, doesn’t find its way into “Oppenheimer,” which knows better than to offer itself up as the last word on anything. To the end, Nolan trusts us to seek out and think about history for ourselves. If we elect not to, that’s on us.'

#Christopher Nolan#Oppenheimer#Leslie Groves#Matt Damon#Cillian Murphy#Los Alamos#The Manhattan Project#Hiroshima#Nagasaki#American Prometheus#Kai Bird#Martin J. Sherwin#Hiroshima Mon Amour#Dunkirk#Letters from Iwo Jima#Clint Eastwood

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

Last minute Clint Walker propaganda...

A few years ago my parents started rewatching old westerns together as their evening entertainment. At some point during the course of their Cheyenne run my mom made up new words to the theme song. Her version went something along the lines of

"Cheyenne, Cheyenne!

Who will you be smooching tonight?

What a man! Cheyenne!"

Jazz hands were incorporated on the "Cheyenne"s.

For this alone he's earned a soft spot in the hearts of our family

This is so incredibly wholesome, and a testament to Clint Walker's hotness. Thanks for the propaganda!

- mod violet

This is adorable! Thank you for sharing! 🥰

- mod vintage

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

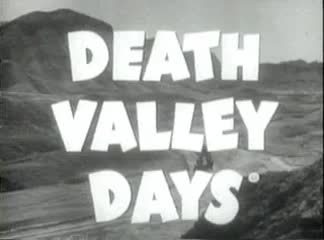

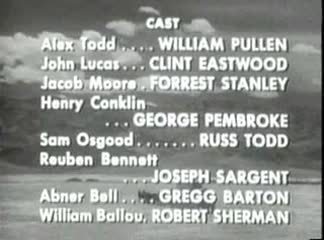

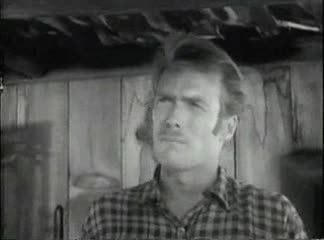

From the Golden Age of Television

The Last Letter - Syndicated - December 8, 1956

A presentation of "Death Valley Days" Season 5 Episode 7

Western

Running Time: 30 minutes

Directed by Stuart E. McGowan

Hosted by Stanley Andrews (as The Old Ranger)

Stars:

William Pullen as Alex Todd

Clint Eastwood as John Lucas

Forrest Stanley as Jacob Moore

George Pembroke as Henry Conklin

Russ Todd as Sam Osgood

Joseph Sargent as Reuben Bennett

Greg Barton as Abner Bell

Robert Sherman as Willam Ballou

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Letters from Iwo Jima (2006) dir. Clint Eastwood

#letters from iwo jima#cartas desde iwo jima#clint eastwood#shido nakamura#yuki matsuzaki#kazunari ninomiya#ken watanabe#movies#films#cinema#peliculas#drama#warlike#belico#second world war#segunda guerra mundial

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Letters from Iwo Jima (2006) Clint Eastwood.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

#redlettermedia#red letter media#youtube#rich evans#jay bauman#gorilla interrupted#half in the bag#mike stoklasa#best of the worst#jack packard#the good the bad and the ugly#clint eastwood#sergio leone#dollars trilogy#spaghetti#spaghetti western#west#western#western movie#wild west

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I?????

#do I want this????#hawkeye#clint barton#marvel comics#I have so many questions#like??? why are we at Lowe’s#what are we building and growing#why does it just randomly say quinjet kn LARGE LETTERS

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Valentine's Day, @kidd-you-not!

This is just a small snippet of what your admirer thought of "Rain in my Head", which was nominated by one of our particpants!

Title: Rain in my Head

Pairing: James "Bucky" Barnes/Clint Barton

Rating: Teen And Up Audiences

Tags/Warnings: Angst with a Happy Ending; Non-Linear Narrative; Vacation Romance; falling in love without knowing you'll ever see the person again; Bucky Barnes Needs a Hug; Falling In Love

Summary: Bucky and Clint meet on a team building retreat organised to improve cooperation at the workplace. Neither one of them is particularly interested in sack racing with people they barely know and cannot stand, so they skip and instead spend time with each other. But the vacation can only last so long and all too soon, they have to return to their regular lives.

As part of our Valentine's Event, we encourage everyone to come check out this work and also drop some love! 💟

#bbe valentines event 2024#bbe love letters 2024#bucky barnes fanfiction#bucky barnes events#bucky barnes#James “Bucky” Barnes/Clint Barton#kidd-you-not

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Natasha: Why are you lying to me? Is it because of my thing with Bucky?

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

@shieldshawk liked for a starter (a long time ago xD )

Since he'd found his dad, Francis had gone through almost every emotion imaginable, which was to be expected. After about a few months, most of them had calmed down. One thought, and feeling, that hadn't was the 'imposter' one. The feeling that this was all wrong. Not the living in the middle of nowhere hillbilly land, Francis enjoyed the farm more than he had expected as the city kid he was, but him sneaking his way into the Barton family. And then there was also the forbidden, and unfair, feeling of jealousy. His mum hadn't told Clint about her pregnancy due to him not being a 'family man', but here he was. A part of Francis was jealous and furious over that, even though he knew that wasn't Clint's fault.

After a comment earlier that day, one that he had both overheard and misunderstood, Francis had now decided it was best for everyone if he just left. He packed his backpack, took the bow Clint had given him, trying not to think of the joy of practicing with him, and sneaked out. Left behind was a letter, barely legible, but you could decipher 'Thanks. I'm ok. Don't worry. Bye.'

#shieldshawk#some early clint and francis#it's up to you how far francis gets before clint#notices the letter he left

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

You know Clint doesn’t want to ask but he’s going to ask to say at the mansion for the 90 day period to complete his detox.

#But it’s not chaotic unhinged clint#its the old clint#the clint that used to wake up before sunrise to shoot arrows in the yard and cook eggs on the stove#the clint that used to write letters and stand up straight and speak like he had something to really say

4 notes

·

View notes