#concrete shear wall buildings

Link

When it comes to constructing buildings, load distribution is a crucial factor that needs to be taken into consideration. The distribution of loads can have a significant impact on the stability and safety of the structure. Therefore, it is imperative to optimize load distribution to ensure that the structure can withstand all types of forces, including lateral forces. Shear walls and bends are two commonly used techniques to optimize load distribution in construction. In this article, we will explore how to optimize load distribution by shear walls and bends in construction.

What is Load Distribution?

Before we delve into the optimization techniques, it is essential to understand what load distribution is. Load distribution is the process of distributing the weight or force of the structure evenly across all its components. It is necessary to distribute the load in a way that each component can carry its share of the weight, without putting undue pressure on any particular area. Load distribution is essential to ensure that the structure can withstand all types of forces and remain stable.

What are Shear Walls?

Shear walls are vertical elements used to resist lateral forces such as wind and earthquakes. These walls are designed to take the majority of the lateral load and transfer it to the foundation. Shear walls are typically made of concrete, masonry, or steel. They are placed strategically in a building to resist lateral forces and ensure that the structure remains stable. Shear walls are designed to provide stiffness and resistance to lateral forces.

How to Optimize Load Distribution by Shear Walls?

To optimize load distribution by shear walls, the walls must be strategically placed in the building. The walls should be placed at locations where lateral forces are likely to occur. The number and thickness of the walls should be determined based on the building's height, location, and expected lateral forces. The walls should be designed to be strong enough to resist the lateral forces and transfer the load to the foundation. The placement and design of shear walls are critical to ensure the stability and safety of the structure.

Read more

1 note

·

View note

Text

Submitted via Google Form:

I'm having trouble trying to calculate the costs of how much a city could save purely on lighting alone by building taller buildings above ground rather than deep into the ground. There are so many factors to lighting costs that seem impossible to compare something above ground to something very similar underground and then I get all the costs that don't even matter i.e. street lights.

In my world costs to build underground would be cheaper than building up due to extreme (almost magical) advances in tunnelling technology. So really, the only big issue is lighting. Above ground saves on lighting because you can turn them off during the day which you basically can't at all underground.

How should I go about this?

Addy: You can have dimmable lights, where you turn lights down real low at night. And you can still turn off lights inside of buildings that aren't being used. That doesn't change at all. Sure, you might have really dim hallway lights (like nightlights), but you don't need lights on full blast 24/7.

If you wanna look at lighting cost savings, I'd say to look at the cost differences in lighting in modern standard buildings vs buildings with adaptive lighting (lights near windows dimmer when it's bright outside).

Or just look at the cost of lighting inside large office buildings - modern office buildings don't make much use of windows, as the buildings are much larger and deeper. Older office buildings made more use of natural light, which has also made them easier to turn into apartments and the like.

Tunneling tech can make it easier and cheaper to build underground, but the main thing about building underground is the sideways pressure from the ground itself. Soil wants to make piles, and building underground means that you have straight walls (aboveground equivalent is a retaining wall), which soil doesn't really like. Still totally doable, though! But you might want to add some kind of soil anchoring mechanism to your tunneling tech.

I'd say that you might want to add in some very high wind speeds at high elevations (say >300' aboveground), which would make building up more than 30 stories difficult to manage. You'd get a lot of lateral shear acting on the building (which is annoying to deal with), plus you'd get a lot of swaying. There are code requirements about the maximum amount a building can sway in the wind – too much movement, and people get vertigo. Or nauseous. You can make a building stiffer to reduce the amount of sway, but it's a hassle and it costs more to do. Steel is especially flexible (concrete is very stiff), so if you've got poor concrete formulations (either weaker concrete or more expensive concrete), or if steel is especially cheap, then building up can become more expensive and just more of a hassle.

Also, if you have soft soil near the surface and good rock further down, that'll also limit your aboveground building height. Heavy buildings put a lot of pressure on the ground. If the ground is rock, that's easy to manage. If it's something soft, then you need to build a larger foundation to spread out the weight into a lower pressure. If you have an area where the top is soft but you've got good bedrock a bit of a ways down, you're going to want to build piles down that far anyways, might as well make a basement. If you've got a basement, well, you've got a building.

On the other hand, it's also a pain to dig through bedrock (especially hard rock), so that's going to add cost once you get further down. Also, in places like Denmark or Florida (places with lots and lots of sand and no bedrock for miles), that brings issues of its own - nothing solid to build anything heavy on. Clay soils are also a pain to deal with, since they swell and shrink based on water content. Imagine if you were trying to build a tower on top of a waterbed…. Except your walls moved just as much. Walls don't like being squished or pulled, and that's what clay soils do.

So if you want extensive underground development, you're probably going to want a place with high winds, soil that'll cooperate (sand, silt, and dry clay (in an area without many trees, say a savanna) could all be suitable), and a rock layer that isn't too close to the surface. That'll help reduce construction costs.

Also, as long as it's plausible, you don't need to know the costs down to the dollar (or similar). Something rough is more than enough.

Feral: Okay so lighting design happens to be the niche within built environment design where my career resides. So… you’re about to get a lot of information you probably don’t need. Sorry.

To calculate costs, you need to need to know the number of lamps (light sources), the initial cost of each lamp, the wattage of each lamp, the number of hours per day* the lamp is on at what percentage of full output,** the cost of energy per kilowatt hour, and the estimated useful life in hours of each lamp.

*When I’m doing these calculations for real, we typically assume 8 hours a day for a kitchen, which is a) used a lot and b) requires artificial lighting for task lighting even when ambient lighting can be provided naturally, but we assume 3 hours a day for a bathroom because even though it may not have natural light, depending on local codes at the time it was built, it’s not used that much.

**If you’re using an electroluminescent source, like an LED, the percentage of total watts used will be the same(-ish) as the percentage of full light output. An electric incandescent source, like a tungsten filament bulb, will not have this one to one relationship; they are more inefficient as they are dimmed.

We’ve talked before about underground living, but it’s really important to recognize that the sun is a lot more important than just “it’s a free light source.”

Now, if you want to get into photometry, it’s a lot. Godspeed. But basically, the thing about lighting a space that a lot of people don’t get is that humans don’t perceive light output. We perceive relative brightness, or contrast. In other words, we are sensitive to the context of the light and the difference between lighting levels rather than the luminance itself.

So what does all this have to do with your world-building question. Frankly, I don’t know. I’m not actually sure what your question has to do with your worldbuilding.

However, visual comfort is a very important aspect of how we perceive an environment. So, if you are trying to build a setting that you can then describe in these terms, you might want to know more about it. So, further reading:

How to Measure Visual Comfort in Buildings (by window manufacturer SageGlass)

How to Design for Visual Comfort Using Natural Light (by ArchDaily)

Guidelines for Optimum Visual Comfort, derived by key performance factors (by The Energy and Resource Institute)

How to Design Buildings for Visual and Acoustical Comfort (by DesignHub1610)

Optimization of Visual Comfort: Building Openings (originally published in the Journal of Building Engineering)

Daylight in Buildings and Visual Comfort Evaluation: the Advantages and Limitations (published in the Journal of Daylighting)

Conditions Required for Visual Comfort (by the Encyclopedia of Occupational Health and Safety)

Provide Comfortable Environments (by the Whole Building Design Guide)

You’ll notice that daylight is an assumption in pretty much all of the above. So, for your world-building, consider what is lost when daylight is removed. Note: it’s more than just energy savings.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

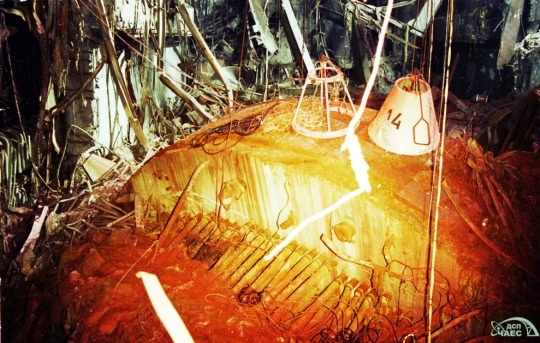

A photo of the 2,000 ton upper biological shield of Chernobyl Reactor 4 after the 1986 disaster.

The reactor cover, shown here in its final resting position, is a circular stainless steel structure seventeen meters across and three meters deep. To keep radiation from the core to a minimum in the reactor hall, the structure was filled with pebbles of serpentinite, a neutron absorbing material. It was labeled as “Structure E” in diagrams of the station, and was affectionately known by plant personnel as “Elena”. Held in place almost exclusively by gravity, the steam explosion in the early hours of April 26th blew Elena off the top of the reactor and flipped partially onto her side. She is still in this position today, resting at about 15 degrees. The piping seem emerging from the bottom of the structure are fuel channels, which contained the fuel that gave the reactor life. She also had pipes for cooling and feed water within her. Also seen in this photo are monitoring “bouys” (the white cone labeled ‘14’) which were equipment suites lowered into the reactor hall during the construction of the Sarcophagus to monitor radiation, temperature, and several other conditions to alert scientists if the fuel started another criticality and to send back general data from the inside of the building.

You can find video footage of Elena here

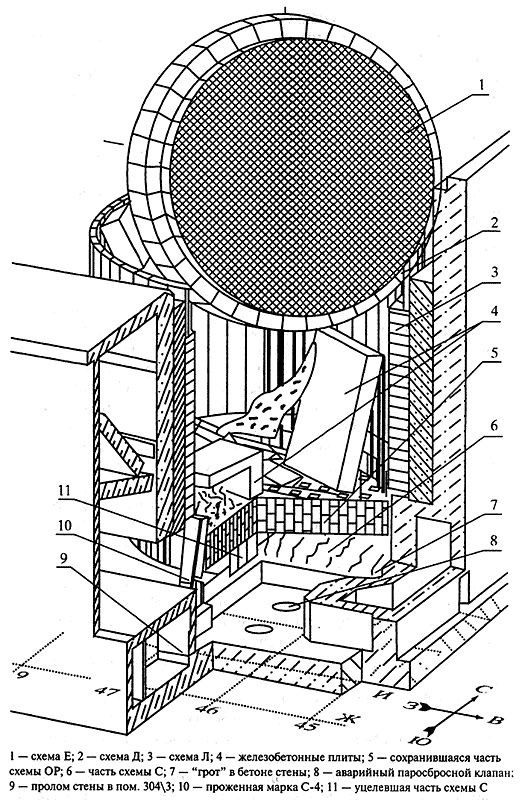

Two diagrams illustrating the current position of Elena within the reactor hall.

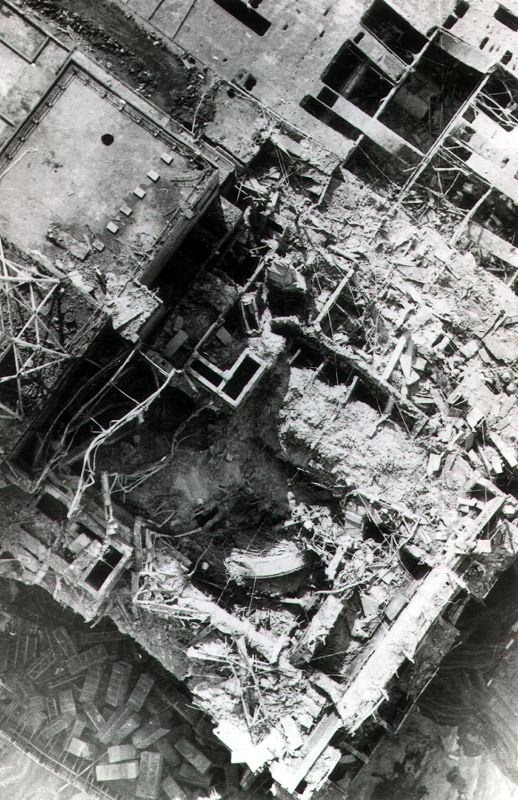

An aerial photo of the interior of the reactor hall during the construction of the Cascade Wall of the Sarcophagus. Elena can be seen in the center of the destruction.

[Image descriptions:

Top image: this is a close up photo of Elena. She sits partially obscured by rubble sticking out of the reactor vessel with her underside exposed to the camera. Hundreds of fuel channel pipes, each about five inches across, stick out of the bottom. They are all ruptured and sheared off due to the explosion. On top of Elena sits a white cone with the number 14 emblazoned on it. This is a bouy used to monitor the conditions in the reactor hall. The background of the photo is the ruined reactor hall. Twisted pipes and other metal pieces sit with a layer of tarnish and char on them, and the concrete walls of the hall are charred as well. The entire scene is extremely eerie, as it is functionally an explosion site that was allowed to sit unchanged for several years.

Second image: This is a cross section diagram showing Elena’s position within the hall, as well as the remaining structure of the plant. The complex warren of rooms and corridors within the reactor building is shown clearly. They are on all sides of the core region, except above.

Third image: A close up diagram of the core region showing Elena and the debris inside the core region, which once held the fuel. It is now empty but for some chunks of concrete and some other rubbles. It is clear that Elena is balanced precariously, as she is essentially a wide flat cylinder wedged between two edges of a slightly smaller, far deeper cylinder.

Final image: An aerial shot of the destroyed reactor hall. The outline of the reactor building is apparent, but it is filled by rubble from the explosion. Elena sits clearly visible in the middle, over the maw of the reactor. Twisted metal and concrete blocks are strewn all over the hall.]

#chernobyl#chernobyl hbo#nuclear#nuclear power#autism#radiation#accidents and disasters#history#reactor#disaster#ussr history#ussr#ussr (former soviet union)#soviet union#soviet

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Secret Life and Anonymous Death of the Most Prolific War-Crimes Investigator in History

When Mustafa Died, in the Earthquakes in Türkiye, his Work in Syria had Assisted in the Prosecutions of Numerous Figures in Bashar al-Assad’s Regime.

— By Ben Taub | September 14, 2023

Photo Illustration By Cristiana Couceiro; Source Photograph From Getty Images

It Was 4:17 A.M. on February 6th in Antakya, an Ancient Turkish City Near the Syrian Border, when the earth tore open and people’s beds began to shake. On the third floor of an apartment in the Ekinci neighborhood, Anwar Saadeddin, a former brigadier general in the Syrian Army, awoke to the sounds of glass breaking, cupboard doors banging, and jars of tahini and cured eggplant spilling onto the floor. He climbed out of bed, but, for almost thirty seconds, he was unable to keep his footing; the building was moving side to side. When the earthquake subsided, he tried to call his daughter Rula, who lived down the road, but the cellular network was down.

Thirty seconds after the first quake, the building started moving again, this time up and down, with such violence that an exterior wall sheared open, and rain started pouring in. The noise was tremendous—concrete splitting, rebar bending, plates shattering, neighbors screaming. When the shaking stopped, about a minute later, Saadeddin, who is in his late sixties, and his wife walked down three flights of stairs, dressed in pajamas and sandals, and went out into the cold.

“All of Antakya was black—there was no electricity anywhere,” Saadeddin recalled. Thousands of the city’s buildings had collapsed. Survivors spilled into the streets, crowding rubble-strewn alleyways and searching for open ground, as minarets toppled and glass shards fluttered down from tower blocks. The general and his wife set off in the direction of the building where Rula lived, with her husband, Mustafa, and their four children.

A third quake shook the ground. When Saadeddin made it to his daughter’s apartment block, flashes of lighting illuminated what was now a fourteen-story grave. The building—which had been completed less than two years earlier—had twisted as it toppled over, crushing many of the residents. Saadeddin felt his body drained of all emotion, almost as if it didn’t belong to him.

Saadeddin was not the only person searching for Rula and her family. For the past decade, her husband, Mustafa, had quietly served as the deputy chief of Syria investigations for the Commission for International Justice and Accountability, a group that has captured more than a million pages of documents from Syrian military and intelligence facilities. Using these files, lawyers at the cija have prepared some of the most comprehensive war-crimes cases since the Nuremberg trials, targeting senior Syrian regime officers—including the President, Bashar al-Assad. After the earthquake, the group directed its investigative focus into a search-and-rescue operation for members of its own Syrian team, many of whom had been displaced to southern Turkey after more than a decade of war. By the end of the third day, nearly everyone was accounted for. Two investigators had lost children; one of them had also lost his wife. But Mustafa was still missing.

For as long as Mustafa had been working for the cija, the group had kept his identity secret—even after it captured a Syrian intelligence document that showed that the regime knew about his investigative work and was actively hunting him down. “He was probably my best investigator,” Mustafa’s supervisor, an Australian who goes by Mick, told me, during a recent visit to the Turkish-Syrian border. Documents that Mustafa obtained, and witness interviews that he conducted, have assisted judicial proceedings in the United States, France, Belgium, Germany, and several other European jurisdictions. According to a cija estimate, Mustafa “either directly obtained or supported in the acquisition” of more than two hundred thousand pages of internal Syrian regime documents, likely making him—by sheer volume of evidence collected—the most prolific war-crimes investigator in history.

Twelve years into the Syrian war, at least half the population has been displaced, often multiple times, under varied circumstances of individual tragedy. No one knows the actual death toll—not even to the nearest hundred thousand. And yet the Syrian regime’s crimes continue apace. “The prisons are full,” Bill Wiley, the cija’s founder and executive director, told me. “All the offenses that started being carried out at scale in 2011 are still being perpetrated. Unlawful detention, physical abuse amounting to torture, extrajudicial killing, sexual offenses—all of that continues. War crimes on the battlefield, particularly in the context of aerial operations. There are still chemical attacks. It all continues. But, as long as there’s the drip, drip, drip of Western prosecutions, pursuant to universal jurisdiction, it’s really difficult to envision the normalization of the regime.”

Before the Syrian Revolution, Mustafa was a trial lawyer, living and working in Al-Rastan, a suburb of the central city of Homs. He and his wife, Rula, had three small children, and Rula was pregnant with the fourth. In early 2011, when Syrians took to the streets to protest against the regime—which had ruled for almost half a century—Assad declared that anyone who did not contribute to “burying sedition” was “a part of it.” Suddenly Mustafa was caught in a delicate position, since many of Rula’s male relatives were military officers.

Her father and her uncles had joined the Syrian armed forces as young men, and served Assad’s father for many years before they served him. In the mid-nineties, Assad’s older brother died in a car crash, and he was called back from his studies in London and sent to a military academy in Homs. Eventually, he joined a staff officers’ course, where Anwar Saadeddin—then a colonel and a military engineer—says he spent a year and a half in his class.

Assad became President in 2000, after his father died, and for the next decade Saadeddin carried on with his duties without complaint. In 2003, Saadeddin was promoted to the rank of brigadier general. At the outset of the revolution, his younger son was a lieutenant, and he was two years from retirement.

Mustafa and Rula’s fourth child was born on April 5, 2011. Three days later, security forces shot a number of protesters in the Baba Amr neighborhood of Homs, including a disabled man, who was unable to run away. They dragged him from the site and returned his mutilated corpse to his family the following evening. From then on, Homs was the site of some of the largest anti-regime protests—and the most violent crackdown.

On April 19th, thousands of people gathered for a sit-in beneath a clock tower. At about midnight, officers warned that anyone who didn’t leave voluntarily would be removed by force. A couple of hours passed; a thousand people remained. At dawn, the people of Homs awoke to traces of a massacre. A witness later reported that religious leaders who had stayed to treat the wounded and to tend to the dead were summarily executed. Several others recalled that the bodies were removed with dump trucks, and that the blood of the dead and wounded was washed away with hoses.

The day after the massacre, according to documents that were later captured from Assad’s highest-level security committee, the regime decided to embark on a “new phase” in the crackdown, to “demonstrate the power and capacity of the state.” Nine days later, regime forces killed at least nineteen protesters in Al-Rastan, where Mustafa and Rula lived. Mustafa wasn’t involved in politics or human-rights work, beyond discussions of basic democratic reforms, but he was appalled by the overtly criminal manner in which security forces and associated militias carried out their campaign with impunity. Locals formed neighborhood-protection units, and soon took up arms against the state.

A few months later, Mustafa briefly sneaked out of Syria to attend a training session in Turkey, led by Bill Wiley, a Canadian war-crimes investigator who had previously worked for various tribunals and the International Criminal Court. Wiley, and others in his world, had noticed a jurisdictional gap in accountability for Syria and had begun casting about for Syrian lawyers who might be up for a perilous, but worthy, task. Although there was no tribunal set up for Syria, and Russia and China had blocked efforts to refer Syria to the I.C.C., Wiley and his associates had reasoned that the process of collecting evidence is purely a matter of risk tolerance and logistics. The work of criminal investigators is different from that of human-rights N.G.O.s: groups like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch produce and disseminate reports on horrific violations and abuse, but Wiley trained Mustafa and the other Syrians in attendance to collect the kind of evidence that could allow prosecutors to assign individual criminal responsibility to senior military and intelligence officers. A video showing tanks firing on unarmed protesters might influence public opinion, but a pile of military communications that proved which commanders were in charge of the operation could one day land someone in jail.

“The first task was to ferret out primary-source material—documents, in particular, generated by the regime,” Wiley told me. “We were looking for prima-facie evidence, not intelligence product or information to inform the public.”

Mustafa instantly grasped the urgency of the project. By day, he carried on with his law practice. But, in secret, he started building up sources within the armed opposition. As they captured new territory, he would go into security and intelligence facilities, box up documents, and move them to secret locations, like farmhouses or caves, farther from the confrontation lines.

“By 2012, we had already started to get some structure,” Wiley recalled. He secured funding from Western governments, and eventually the group settled on a name: the Commission for International Justice and Accountability. “We had our guys in Raqqa, Idlib, Aleppo, and so forth—at least one guy in all the key areas,” he said. From there, the cija built out each team—between two and four individuals, working under the head of each provincial cell. “And Mustafa was our core guy in Homs.”

Anwar Saadeddin soon found himself wielding his position in order to rescue relatives who were caught up in the conflict. His younger son, an Army lieutenant, was detained by military operatives on the outskirts of Damascus, after another officer in his brigade reported him for watching Al Arabiya and Al Jazeera. According to an internal military communication, which was later captured by the cija, Assad believed that foreign reporting on Syria amounted to “psychological warfare aimed at creating a state of internal chaos.”

When Saadeddin’s son was detained, he recalled, “I interfered just to decrease the detention period to thirty days.” Soon afterward, he learned that Mustafa was a target of military intelligence in Homs, where the local facility, Branch 261, was headed by one of Saadeddin’s friends: Mohammed Zamrini.

Mustafa wasn’t calling for an armed rebellion, and, at the time, neither the regime nor his father-in-law knew of his connection to Wiley and the cija. But rebel factions were active in Al-Rastan, and Mustafa was known to have urged them not to destroy any public establishments. To hard-liners in the regime, such interaction was considered tantamount to collaboration. “So I went with Mustafa to the branch,” Saadeddin told me. Zamrini agreed to detain him as a formality—for about twelve hours, with light interrogations and no torture or abuse—so that he could essentially cross Mustafa off the list.

In the next few months, the security situation rapidly deteriorated. The Army encircled rebellious neighborhoods near Homs and shelled them to the ground. Saadeddin’s son, who was serving near Damascus, was arrested a second time, and in order to get him released Saadeddin had to supplicate himself in the office of Assef Shawkat, Assad’s brother-in-law and the deputy minister of defense. In Homs, Saadeddin started driving Mustafa to and from work in his light-blue Kia; as a brigadier general, he could move passengers through checkpoints without them being searched or arrested.

But Saadeddin was beginning to find his position untenable. He sensed that the regime’s policy of total violence would lead to the destruction of the country. That spring, he began to share his fears and frustrations with close colleagues and friends, including the commander of his son’s brigade. But it was a perilous game: Assad’s highest-level security committee had instructed the heads of regional security branches to hunt down “security agents who are irresolute or unenthusiastic” in carrying out their duties. According to a U.N. inquiry, some officers were detained and tortured for having “attempted to spare civilians” on whom they had been ordered to fire.

That spring, Saadeddin’s car was stopped at one of the checkpoints that ordinarily waved him through. It was the first time that his position served not as protection against interrogation but as a reason to question his loyalty. The regime was quickly losing territory, and as the conflict spiralled out of control many senior officers found themselves approaching the limits of their willingness to go along. He and his brothers had “reached a point where we would either stand by the regime and have to take part in atrocities, or we would have to defect,” he told me.

That July, Saadeddin gathered his brothers, his sons, two nephews, and several other military officers in front of a small camera, somewhere near the Turkish-Syrian border. Dressed in his uniform, he announced that the army to which he had pledged his allegiance some four decades earlier had “deviated from its mission” and turned on its citizens instead. To honor the Syrian public’s “steadfastness in the face of barbaric assaults by Assad’s bloody gangs, we have decided to defect from the Army,” he said. It was one of the largest mass defections of Syrian officers, and his plan was to take a leading role in the rebellion—to fight for freedom “until martyrdom or victory.” In response, Saadeddin told me, their former colleagues sent troops to destroy their houses and those of their family members. They expropriated their land and killed several of their relatives.

By now, the regime had ceded swaths of Syria’s border with Turkey to various rebel forces. Saadeddin moved his family across the border and into a refugee camp that the Turkish government had set up for military and intelligence officers who defected. Then he went back to Syria, to try to bring some order and unity to the rebel factions that were battling his former colleagues.

But Mustafa and his family stayed behind in Al-Rastan, which was now firmly in rebel hands. The regime’s loss of control at the Turkish border meant that the cija could start moving its captured documents out of the country.

“It was complicated, reaching the border, because the confrontation lines were so fluid,” Wiley recalled. “And there were multiple bodies who were overtly hostile to cija”—not only the regime but also a growing number of extremist groups who were suspicious of anyone working for a Western N.G.O. During the first document extraction, a courier was shot and injured. During the next, another courier vanished with a suitcase full of documents. “Just fucking disappeared,” Wiley said. “Probably thought he could sell them.” Mustafa recruited a cousin to transport some files to Turkey. But, after the delivery, on the way back to Al-Rastan, the cousin took a minibus, and the vehicle was ambushed by regime troops. “He was shot, but it was unclear if he was wounded or dead when they took him away,” another Syrian cija investigator, whom I’ll call Omar, told me. For the next several weeks, regime agents blackmailed Mustafa, saying that for twenty thousand dollars they would release his cousin from custody. But, when Mustafa asked for proof of life, they failed to provide it—suggesting that the cousin had already died in custody.

By now, Wiley had issued new orders for the extraction process. “I said, ‘O.K., there needs to be a plan, and I need to know what the plan is,’ ” he recalled. “ ‘How are you getting from A to B? What risks are there between point A and point B? And how are you going to ameliorate those risks?’ As opposed to just throwing the shit in the car and going, ‘Well, God decides.’ ”

Saadeddin Spent Much of the next eighteen months trying to organize disparate rebel groups into a unified command. He travelled all over northern Syria, as rebels took new ground, and met with all manner of revolutionaries—from secular defectors to hard-line field commanders. By the summer of 2013, the regime had ceded control of most of northern Syria. But there was little cohesion between the rebel factions, and isis and Al Qaeda had come to exploit the power vacuum in rebel territory. At some point, Saadeddin recalled, he scolded a Tunisian isis commander for arousing sectarian and ethnic tensions, and imposing extremism onto local communities. “He responded that I was an apostate, and suggested that I should be killed,” Saadeddin told me.

In Al-Rastan, a regime shell penetrated the walls of Mustafa’s house, but it didn’t explode. At that point, Rula and the children moved to Reyhanli, a small Turkish village that is so close to the border that you can eat at a kebab shop there while watching sheep graze in Syria. It was also a short drive from the defected officers’ camp, where Rula’s mother and several other relatives were living. But Mustafa stayed behind, to carry out his investigative work for the cija.

“When new areas were liberated, the security branches were raided, and many people took files,” Omar recalled. Some of them didn’t grasp the significance of the files; at least one soldier burned them for warmth. “But most people knew the documents would be useful, someday—they just didn’t know what to do with them. So they just kept them. And the challenge was in identifying who had what, where.”

But, before long, Omar continued, “Mustafa built a wide network of contacts in rebel territory. Word got out that he was collecting documents, and so eventually people would refer others who had taken documents to him.” Sometimes he encountered a reluctance to turn over the originals, until he shared with them the outlines of the cija’s objective and paths to accountability. “At that point, they would usually relent, understanding that his use for them was the best use.”

As his profile in rebel territory grew, Mustafa remained highly secretive. But, from time to time, he asked his father-in-law for introductions to other defected military and intelligence officers. By now, Saadeddin recalled, “I knew the nature of his work, but I didn’t discuss it with him.” There was an understanding that it was best to compartmentalize any sensitive information, for the sake of the family. “Sometimes my wife didn’t even know what I was doing,” Saadeddin said. “But I do know that, at a certain point, through his interviews, Mustafa came to know these defected officers even better than I did.”

In 2014, Wiley restructured the cija’s Syrian team; as deputy chief of investigations, Mustafa now presided over all the group’s provincial cells. “He was very good at finding documents, and he understood evidence and law,” Wiley said. “But he was also respected by his peers. And he had a natural empathy, which translated into him being a very good interviewer” of victims and perpetrators alike. According to Omar, Mustafa often cut short his appearances at social gatherings, citing family or work. “I know it’s a cliché, but he really was a family guy,” Wiley told me. “But where he excelled in our view—because we don’t need a bunch of good family guys, to be blunt—is that he could execute.”

That July, Assad’s General Intelligence Directorate apparently learned of the cija’s activities, long before the group had been named in the press. In a document that was sent to at least ten intelligence branches—and which was later captured by the cija—the directorate identified Mustafa as “vice-chairman” of the group, and also listed the names of the leading investigators within each of the cija’s governorate cells. At the bottom of the document, the head of the directorate handwrote orders to “arrest them along with their collaborators.”

By now, Western governments, which had pledged to support secular opposition groups, found the situation in northern Syria unpalatable; there was no way to guarantee that weapons given to a secular armed faction would not end up in jihadi hands. Saadeddin had begun to lose hope in the revolution—a sentiment that grew only stronger when Assad’s forces killed more than a thousand civilians with sarin gas, and the Obama Administration backed away from its “red-line” warning of retaliation. “At that point, I lost all faith in the international community,” Saadeddin told me. “I felt that they didn’t want Syria to become liberated—they wanted Syria to stay as it was.” He moved into the defected officers’ camp in southern Turkey, where he remained—feeling “rotten,” consumed by a sense of impotence and frustration—for most of the next decade.

I First Came Into Contact with the cija late in the summer of 2015. By that point, the group had smuggled more than six hundred thousand documents out of Syria, and had prepared a legal brief that assigned individual criminal responsibility for the torture and murder of thousands of people in detention centers to senior members of the Syrian security-intelligence apparatus—including Assad himself. In the following years, the cija expanded its operations to Iraq, Myanmar, Libya, and Ukraine. But Syria was always at the core.

“In terms of the opposition overrunning regime territory—that effectively ceased in September, 2015, when the Russians came in,” Wiley recalled. In the following years, Russian fighter jets pummelled areas under rebel control, while fighters from Russian mercenary groups, Iranian militias, and Hezbollah reinforced Assad’s troops on the ground. In time, the confrontation lines settled, with the country effectively carved into areas under regime, opposition, Turkish, and Kurdish control. But Mustafa and other investigators continued to identify troves of documents, scattered among various hidden sites. “We’d acquire them from different places, and then concentrate them,” Wiley said. Omar told me that it was best to keep files as close to the border as possible, to limit the chance of their being destroyed in the event that the regime took back ground. “Mustafa would sometimes spend a week or more prepping for document extractions,” Omar said. “He would sleep in tents,” in camps filled with other displaced civilians, “while he waited for the right moment to move the files closer to the border.”

At the cija’s headquarters, in Western Europe, the organization built cases against senior intelligence officers, like the double agent Khaled al-Halabi, and provided evidence to European prosecutors who were investigating lesser targets all over the continent. In recent years, Western prosecutors and police agencies have sent hundreds of requests for investigative assistance to the cija headquarters; when the answers can’t be found in the existing files, analysts refer the inquiries, via Mick, the Australian in southern Turkey, to the Syrians on the ground. “We wouldn’t tell them who’s asking, or who the suspects are,” Wiley said. “We’d just say, ‘O.K., we’re interested in witnesses to a particular crime base’—a security-intelligence facility, a static killing, an execution, that kind of thing. And then they would identify witnesses and do a screening interview.” When requests came through, Mick told me, “Mustafa was usually the first team member that I went to, because his networks were so good.”

During the peak years of the pandemic, Mustafa identified and collected witness statements against a trio of Syrian isis members who had been active in a remote village in the deserts of central Syria and were now scattered across Western Europe. All three men were arrested after his death.

Perhaps Mustafa’s most enduring contribution to the cija’s casework is found in one of the group’s most comprehensive, confidential investigative briefs, which I read at the headquarters this spring. It’s a three-hundred-page document, with almost thirteen hundred footnotes, establishing individual criminal responsibility for war crimes carried out during the regime’s 2012 siege of Baba Amr, a neighborhood in the southern part of Mustafa’s home city, Homs. Other cases have centered on torture in detention facilities; this is the first Syrian war-crimes brief that focusses on the conduct of hostilities, and it spells out, in astonishing and historic detail, a litany of crimes, ranging from indiscriminate shelling to mass executions of civilians who were rounded up and killed in warehouses and factories as regime forces swept through. The Homs Brief—for which Mustafa collected much of the underlying evidence—also assigns criminal responsibility to individual commanders within the Syrian Army’s 18th Tank Division, which carried out the assault.

“He thought he was contributing to a better Syria,” Wiley said. “When—and what it would look like—was unsure. But he believed in what he was doing. He could have fucked off years ago. We probably could have gotten him to Canada. We talked about it, because one of his daughters had a congenital heart issue.” Nevertheless, he stayed.

Last year, Mustafa bought an apartment on the eleventh floor of a new tower block in Antakya. Rula’s aunt moved into the same building, a couple of stories below. Her parents left the defected officers’ camp and moved into another apartment block, a short walk up the road. A few months later, Mick recalled, “Mustafa said to me, ‘When I’m at home with my family, it doesn’t matter what’s happening outside—it doesn’t matter if there’s a war. When I’m at home, I’m at peace.’ ”

Last December, Mick was visiting Mustafa’s apartment when the floor began to shake. “It spooked me—it was my first time feeling this kind of tremor,” Mick recalled. Mustafa laughed and said that they happen “all the time.” Then he went to check on Rula and the children, who reported that they hadn’t even felt it.

A couple of months later, Mick awoke to news of the catastrophic earthquake and tried to call members of his Syrian team. But the cellular networks were down in Antakya, and it was impossible for him to travel there, because the local airport’s runway had buckled, along with many local roads.

Saadeddin’s sister was dug out of the complex alive; her husband survived as well, but died in a hospital soon afterward, without anyone in the family knowing where he was. On the fourth day of search-and-rescue operations, Mustafa’s passport was found in the rubble. Then his laptop, then his wife’s handbag. “When they found the bodies,” Omar said, “Mustafa was hugging his daughter, his wife was hugging their son, and the other two children were hugging each other.”

Omar spent the next several days sleeping in his car, along with his wife and six children. Thousands of aftershocks shook the region, and, by the time I met with him, a few hundred metres from the Syrian border, he was so rattled that he reacted to everyday sounds as if they might signal a building’s collapse. His breath was short and his eyes welled with tears; Mustafa had been one of his best friends, and he had also lost eleven relatives to the quake, all of whom had been displaced from the same village in northern Syria. Then his young son walked into the room, and he turned his head. “We try to hide from our children our fear and our grief, so that they don’t feel as if we are weak,” he said.

A few weeks after the earthquake, there was an empty seat at a prestigious international-criminal-investigations course, in the Hague. Mustafa had been scheduled to attend. “We can mitigate the effects of war, except bad luck, but we didn’t factor an earthquake into the plan, institutionally,” Wiley told me. Mick coördinated humanitarian assistance for displaced investigators, and, as Wiley put it, “the operational posture came back really quickly.” Omar has now taken over Mustafa’s leadership duties. “Keep in mind how resilient this cadre is,” Wiley continued. “They’re already all refugees, perhaps with the rare exception. They had already lost their homes, lost all their stuff.”

It was the middle of April, more than two months after the quake. Much of Antakya had been completely flattened, and what still stood was cracked and broken, completely abandoned, and poised to collapse. Mick and I made our way through the old city on foot; the alleys were too narrow for digging equipment to go through, and so we found ourselves climbing over rubble, as if the buildings had fallen the day before. The pets of those entombed in the collapsed buildings followed us, still wearing their collars—bewildered, brand-new strays. ♦

#Syria 🇸🇾 | Earthquakes | Türkiye 🇹🇷 | War Crimes#President Bashar al-Assad#War-Crimes Investigator#Secret Life#Anonymous Death#History#Ben Taub#The New Yorker#Mustafa | Trial Lawyer

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

It was 4:17 A.M. on February 6th in Antakya, an ancient Turkish city near the Syrian border, when the earth tore open and people’s beds began to shake. On the third floor of an apartment in the Ekinci neighborhood, Anwar Saadeddin, a former brigadier general in the Syrian Army, awoke to the sounds of glass breaking, cupboard doors banging, and jars of tahini and cured eggplant spilling onto the floor. He climbed out of bed, but, for almost thirty seconds, he was unable to keep his footing; the building was moving side to side. When the earthquake subsided, he tried to call his daughter Rula, who lived down the road, but the cellular network was down.

Thirty seconds after the first quake, the building started moving again, this time up and down, with such violence that an exterior wall sheared open, and rain started pouring in. The noise was tremendous—concrete splitting, rebar bending, plates shattering, neighbors screaming. When the shaking stopped, about a minute later, Saadeddin, who is in his late sixties, and his wife walked down three flights of stairs, dressed in pajamas and sandals, and went out into the cold.

“All of Antakya was black—there was no electricity anywhere,” Saadeddin recalled. Thousands of the city’s buildings had collapsed. Survivors spilled into the streets, crowding rubble-strewn alleyways and searching for open ground, as minarets toppled and glass shards fluttered down from tower blocks. The general and his wife set off in the direction of the building where Rula lived, with her husband, Mustafa, and their four children.

A third quake shook the ground. When Saadeddin made it to his daughter’s apartment block, flashes of lighting illuminated what was now a fourteen-story grave. The building—which had been completed less than two years earlier—had twisted as it toppled over, crushing many of the residents. Saadeddin felt his body drained of all emotion, almost as if it didn’t belong to him.

Saadeddin was not the only person searching for Rula and her family. For the past decade, her husband, Mustafa, had quietly served as the deputy chief of Syria investigations for the Commission for International Justice and Accountability, a group that has captured more than a million pages of documents from Syrian military and intelligence facilities. Using these files, lawyers at the CIJA have prepared some of the most comprehensive war-crimes cases since the Nuremberg trials, targeting senior Syrian regime officers—including the President, Bashar al-Assad. After the earthquake, the group directed its investigative focus into a search-and-rescue operation for members of its own Syrian team, many of whom had been displaced to southern Turkey after more than a decade of war. By the end of the third day, nearly everyone was accounted for. Two investigators had lost children; one of them had also lost his wife. But Mustafa was still missing.

For as long as Mustafa had been working for the CIJA, the group had kept his identity secret—even after it captured a Syrian intelligence document that showed that the regime knew about his investigative work and was actively hunting him down. “He was probably my best investigator,” Mustafa’s supervisor, an Australian who goes by Mick, told me, during a recent visit to the Turkish-Syrian border. Documents that Mustafa obtained, and witness interviews that he conducted, have assisted judicial proceedings in the United States, France, Belgium, Germany, and several other European jurisdictions. According to a CIJA estimate, Mustafa “either directly obtained or supported in the acquisition” of more than two hundred thousand pages of internal Syrian regime documents, likely making him—by sheer volume of evidence collected—the most prolific war-crimes investigator in history.

Twelve years into the Syrian war, at least half the population has been displaced, often multiple times, under varied circumstances of individual tragedy. No one knows the actual death toll—not even to the nearest hundred thousand. And yet the Syrian regime’s crimes continue apace. “The prisons are full,” Bill Wiley, the CIJA’s founder and executive director, told me. “All the offenses that started being carried out at scale in 2011 are still being perpetrated. Unlawful detention, physical abuse amounting to torture, extrajudicial killing, sexual offenses—all of that continues. War crimes on the battlefield, particularly in the context of aerial operations. There are still chemical attacks. It all continues. But, as long as there’s the drip, drip, drip of Western prosecutions, pursuant to universal jurisdiction, it’s really difficult to envision the normalization of the regime.”

Before the Syrian revolution, Mustafa was a trial lawyer, living and working in Al-Rastan, a suburb of the central city of Homs. He and his wife, Rula, had three small children, and Rula was pregnant with the fourth. In early 2011, when Syrians took to the streets to protest against the regime—which had ruled for almost half a century—Assad declared that anyone who did not contribute to “burying sedition” was “a part of it.” Suddenly Mustafa was caught in a delicate position, since many of Rula’s male relatives were military officers.

Her father and her uncles had joined the Syrian armed forces as young men, and served Assad’s father for many years before they served him. In the mid-nineties, Assad’s older brother died in a car crash, and he was called back from his studies in London and sent to a military academy in Homs. Eventually, he joined a staff officers’ course, where Anwar Saadeddin—then a colonel and a military engineer—says he spent a year and a half in his class.

Assad became President in 2000, after his father died, and for the next decade Saadeddin carried on with his duties without complaint. In 2003, Saadeddin was promoted to the rank of brigadier general. At the outset of the revolution, his younger son was a lieutenant, and he was two years from retirement.

Mustafa and Rula’s fourth child was born on April 5, 2011. Three days later, security forces shot a number of protesters in the Baba Amr neighborhood of Homs, including a disabled man, who was unable to run away. They dragged him from the site and returned his mutilated corpse to his family the following evening. From then on, Homs was the site of some of the largest anti-regime protests—and the most violent crackdown.

On April 19th, thousands of people gathered for a sit-in beneath a clock tower. At about midnight, officers warned that anyone who didn’t leave voluntarily would be removed by force. A couple of hours passed; a thousand people remained. At dawn, the people of Homs awoke to traces of a massacre. A witness later reported that religious leaders who had stayed to treat the wounded and to tend to the dead were summarily executed. Several others recalled that the bodies were removed with dump trucks, and that the blood of the dead and wounded was washed away with hoses.

The day after the massacre, according to documents that were later captured from Assad’s highest-level security committee, the regime decided to embark on a “new phase” in the crackdown, to “demonstrate the power and capacity of the state.” Nine days later, regime forces killed at least nineteen protesters in Al-Rastan, where Mustafa and Rula lived. Mustafa wasn’t involved in politics or human-rights work, beyond discussions of basic democratic reforms, but he was appalled by the overtly criminal manner in which security forces and associated militias carried out their campaign with impunity. Locals formed neighborhood-protection units, and soon took up arms against the state.

A few months later, Mustafa briefly sneaked out of Syria to attend a training session in Turkey, led by Bill Wiley, a Canadian war-crimes investigator who had previously worked for various tribunals and the International Criminal Court. Wiley, and others in his world, had noticed a jurisdictional gap in accountability for Syria and had begun casting about for Syrian lawyers who might be up for a perilous, but worthy, task. Although there was no tribunal set up for Syria, and Russia and China had blocked efforts to refer Syria to the I.C.C., Wiley and his associates had reasoned that the process of collecting evidence is purely a matter of risk tolerance and logistics. The work of criminal investigators is different from that of human-rights N.G.O.s: groups like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch produce and disseminate reports on horrific violations and abuse, but Wiley trained Mustafa and the other Syrians in attendance to collect the kind of evidence that could allow prosecutors to assign individual criminal responsibility to senior military and intelligence officers. A video showing tanks firing on unarmed protesters might influence public opinion, but a pile of military communications that proved which commanders were in charge of the operation could one day land someone in jail.

“The first task was to ferret out primary-source material—documents, in particular, generated by the regime,” Wiley told me. “We were looking for prima-facie evidence, not intelligence product or information to inform the public.”

Mustafa instantly grasped the urgency of the project. By day, he carried on with his law practice. But, in secret, he started building up sources within the armed opposition. As they captured new territory, he would go into security and intelligence facilities, box up documents, and move them to secret locations, like farmhouses or caves, farther from the confrontation lines.

“By 2012, we had already started to get some structure,” Wiley recalled. He secured funding from Western governments, and eventually the group settled on a name: the Commission for International Justice and Accountability. “We had our guys in Raqqa, Idlib, Aleppo, and so forth—at least one guy in all the key areas,” he said. From there, the CIJA built out each team—between two and four individuals, working under the head of each provincial cell. “And Mustafa was our core guy in Homs.”

Anwar Saadeddin soon found himself wielding his position in order to rescue relatives who were caught up in the conflict. His younger son, an Army lieutenant, was detained by military operatives on the outskirts of Damascus, after another officer in his brigade reported him for watching Al Arabiya and Al Jazeera. According to an internal military communication, which was later captured by the CIJA, Assad believed that foreign reporting on Syria amounted to “psychological warfare aimed at creating a state of internal chaos.”

When Saadeddin’s son was detained, he recalled, “I interfered just to decrease the detention period to thirty days.” Soon afterward, he learned that Mustafa was a target of military intelligence in Homs, where the local facility, Branch 261, was headed by one of Saadeddin’s friends: Mohammed Zamrini.

Mustafa wasn’t calling for an armed rebellion, and, at the time, neither the regime nor his father-in-law knew of his connection to Wiley and the CIJA. But rebel factions were active in Al-Rastan, and Mustafa was known to have urged them not to destroy any public establishments. To hard-liners in the regime, such interaction was considered tantamount to collaboration. “So I went with Mustafa to the branch,” Saadeddin told me. Zamrini agreed to detain him as a formality—for about twelve hours, with light interrogations and no torture or abuse—so that he could essentially cross Mustafa off the list.

In the next few months, the security situation rapidly deteriorated. The Army encircled rebellious neighborhoods near Homs and shelled them to the ground. Saadeddin’s son, who was serving near Damascus, was arrested a second time, and in order to get him released Saadeddin had to supplicate himself in the office of Assef Shawkat, Assad’s brother-in-law and the deputy minister of defense. In Homs, Saadeddin started driving Mustafa to and from work in his light-blue Kia; as a brigadier general, he could move passengers through checkpoints without them being searched or arrested.

But Saadeddin was beginning to find his position untenable. He sensed that the regime’s policy of total violence would lead to the destruction of the country. That spring, he began to share his fears and frustrations with close colleagues and friends, including the commander of his son’s brigade. But it was a perilous game: Assad’s highest-level security committee had instructed the heads of regional security branches to hunt down “security agents who are irresolute or unenthusiastic” in carrying out their duties. According to a U.N. inquiry, some officers were detained and tortured for having “attempted to spare civilians” on whom they had been ordered to fire.

That spring, Saadeddin’s car was stopped at one of the checkpoints that ordinarily waved him through. It was the first time that his position served not as protection against interrogation but as a reason to question his loyalty. The regime was quickly losing territory, and as the conflict spiralled out of control many senior officers found themselves approaching the limits of their willingness to go along. He and his brothers had “reached a point where we would either stand by the regime and have to take part in atrocities, or we would have to defect,” he told me.

That July, Saadeddin gathered his brothers, his sons, two nephews, and several other military officers in front of a small camera, somewhere near the Turkish-Syrian border. Dressed in his uniform, he announced that the army to which he had pledged his allegiance some four decades earlier had “deviated from its mission” and turned on its citizens instead. To honor the Syrian public’s “steadfastness in the face of barbaric assaults by Assad’s bloody gangs, we have decided to defect from the Army,” he said. It was one of the largest mass defections of Syrian officers, and his plan was to take a leading role in the rebellion—to fight for freedom “until martyrdom or victory.” In response, Saadeddin told me, their former colleagues sent troops to destroy their houses and those of their family members. They expropriated their land and killed several of their relatives.

By now, the regime had ceded swaths of Syria’s border with Turkey to various rebel forces. Saadeddin moved his family across the border and into a refugee camp that the Turkish government had set up for military and intelligence officers who defected. Then he went back to Syria, to try to bring some order and unity to the rebel factions that were battling his former colleagues.

But Mustafa and his family stayed behind in Al-Rastan, which was now firmly in rebel hands. The regime’s loss of control at the Turkish border meant that the CIJA could start moving its captured documents out of the country.

“It was complicated, reaching the border, because the confrontation lines were so fluid,” Wiley recalled. “And there were multiple bodies who were overtly hostile to CIJA”—not only the regime but also a growing number of extremist groups who were suspicious of anyone working for a Western N.G.O. During the first document extraction, a courier was shot and injured. During the next, another courier vanished with a suitcase full of documents. “Just fucking disappeared,” Wiley said. “Probably thought he could sell them.” Mustafa recruited a cousin to transport some files to Turkey. But, after the delivery, on the way back to Al-Rastan, the cousin took a minibus, and the vehicle was ambushed by regime troops. “He was shot, but it was unclear if he was wounded or dead when they took him away,” another Syrian CIJA investigator, whom I’ll call Omar, told me. For the next several weeks, regime agents blackmailed Mustafa, saying that for twenty thousand dollars they would release his cousin from custody. But, when Mustafa asked for proof of life, they failed to provide it—suggesting that the cousin had already died in custody.

By now, Wiley had issued new orders for the extraction process. “I said, ‘O.K., there needs to be a plan, and I need to know what the plan is,’ ” he recalled. “ ‘How are you getting from A to B? What risks are there between point A and point B? And how are you going to ameliorate those risks?’ As opposed to just throwing the shit in the car and going, ‘Well, God decides.’ ”

Saadeddin spent much of the next eighteen months trying to organize disparate rebel groups into a unified command. He travelled all over northern Syria, as rebels took new ground, and met with all manner of revolutionaries—from secular defectors to hard-line field commanders. By the summer of 2013, the regime had ceded control of most of northern Syria. But there was little cohesion between the rebel factions, and ISIS and Al Qaeda had come to exploit the power vacuum in rebel territory. At some point, Saadeddin recalled, he scolded a Tunisian ISIS commander for arousing sectarian and ethnic tensions, and imposing extremism onto local communities. “He responded that I was an apostate, and suggested that I should be killed,” Saadeddin told me.

In Al-Rastan, a regime shell penetrated the walls of Mustafa’s house, but it didn’t explode. At that point, Rula and the children moved to Reyhanli, a small Turkish village that is so close to the border that you can eat at a kebab shop there while watching sheep graze in Syria. It was also a short drive from the defected officers’ camp, where Rula’s mother and several other relatives were living. But Mustafa stayed behind, to carry out his investigative work for the CIJA.

“When new areas were liberated, the security branches were raided, and many people took files,” Omar recalled. Some of them didn’t grasp the significance of the files; at least one soldier burned them for warmth. “But most people knew the documents would be useful, someday—they just didn’t know what to do with them. So they just kept them. And the challenge was in identifying who had what, where.”

But, before long, Omar continued, “Mustafa built a wide network of contacts in rebel territory. Word got out that he was collecting documents, and so eventually people would refer others who had taken documents to him.” Sometimes he encountered a reluctance to turn over the originals, until he shared with them the outlines of the CIJA’s objective and paths to accountability. “At that point, they would usually relent, understanding that his use for them was the best use.”

As his profile in rebel territory grew, Mustafa remained highly secretive. But, from time to time, he asked his father-in-law for introductions to other defected military and intelligence officers. By now, Saadeddin recalled, “I knew the nature of his work, but I didn’t discuss it with him.” There was an understanding that it was best to compartmentalize any sensitive information, for the sake of the family. “Sometimes my wife didn’t even know what I was doing,” Saadeddin said. “But I do know that, at a certain point, through his interviews, Mustafa came to know these defected officers even better than I did.”

In 2014, Wiley restructured the CIJA’s Syrian team; as deputy chief of investigations, Mustafa now presided over all the group’s provincial cells. “He was very good at finding documents, and he understood evidence and law,” Wiley said. “But he was also respected by his peers. And he had a natural empathy, which translated into him being a very good interviewer” of victims and perpetrators alike. According to Omar, Mustafa often cut short his appearances at social gatherings, citing family or work. “I know it’s a cliché, but he really was a family guy,” Wiley told me. “But where he excelled in our view—because we don’t need a bunch of good family guys, to be blunt—is that he could execute.”

That July, Assad’s General Intelligence Directorate apparently learned of the CIJA’s activities, long before the group had been named in the press. In a document that was sent to at least ten intelligence branches—and which was later captured by the CIJA—the directorate identified Mustafa as “vice-chairman” of the group, and also listed the names of the leading investigators within each of the CIJA’s governorate cells. At the bottom of the document, the head of the directorate handwrote orders to “arrest them along with their collaborators.”

By now, Western governments, which had pledged to support secular opposition groups, found the situation in northern Syria unpalatable; there was no way to guarantee that weapons given to a secular armed faction would not end up in jihadi hands. Saadeddin had begun to lose hope in the revolution—a sentiment that grew only stronger when Assad’s forces killed more than a thousand civilians with sarin gas, and the Obama Administration backed away from its “red-line” warning of retaliation. “At that point, I lost all faith in the international community,” Saadeddin told me. “I felt that they didn’t want Syria to become liberated—they wanted Syria to stay as it was.” He moved into the defected officers’ camp in southern Turkey, where he remained—feeling “rotten,” consumed by a sense of impotence and frustration—for most of the next decade.

I first came into contact with the CIJA late in the summer of 2015. By that point, the group had smuggled more than six hundred thousand documents out of Syria, and had prepared a legal brief that assigned individual criminal responsibility for the torture and murder of thousands of people in detention centers to senior members of the Syrian security-intelligence apparatus—including Assad himself. In the following years, the CIJA expanded its operations to Iraq, Myanmar, Libya, and Ukraine. But Syria was always at the core.

“In terms of the opposition overrunning regime territory—that effectively ceased in September, 2015, when the Russians came in,” Wiley recalled. In the following years, Russian fighter jets pummelled areas under rebel control, while fighters from Russian mercenary groups, Iranian militias, and Hezbollah reinforced Assad’s troops on the ground. In time, the confrontation lines settled, with the country effectively carved into areas under regime, opposition, Turkish, and Kurdish control. But Mustafa and other investigators continued to identify troves of documents, scattered among various hidden sites. “We’d acquire them from different places, and then concentrate them,” Wiley said. Omar told me that it was best to keep files as close to the border as possible, to limit the chance of their being destroyed in the event that the regime took back ground. “Mustafa would sometimes spend a week or more prepping for document extractions,” Omar said. “He would sleep in tents,” in camps filled with other displaced civilians, “while he waited for the right moment to move the files closer to the border.”

At the CIJA’s headquarters, in Western Europe, the organization built cases against senior intelligence officers, like the double agent Khaled al-Halabi, and provided evidence to European prosecutors who were investigating lesser targets all over the continent. In recent years, Western prosecutors and police agencies have sent hundreds of requests for investigative assistance to the CIJA headquarters; when the answers can’t be found in the existing files, analysts refer the inquiries, via Mick, the Australian in southern Turkey, to the Syrians on the ground. “We wouldn’t tell them who’s asking, or who the suspects are,” Wiley said. “We’d just say, ‘O.K., we’re interested in witnesses to a particular crime base’—a security-intelligence facility, a static killing, an execution, that kind of thing. And then they would identify witnesses and do a screening interview.” When requests came through, Mick told me, “Mustafa was usually the first team member that I went to, because his networks were so good.”

During the peak years of the pandemic, Mustafa identified and collected witness statements against a trio of Syrian ISIS members who had been active in a remote village in the deserts of central Syria and were now scattered across Western Europe. All three men were arrested after his death.

Perhaps Mustafa’s most enduring contribution to the CIJA’s casework is found in one of the group’s most comprehensive, confidential investigative briefs, which I read at the headquarters this spring. It’s a three-hundred-page document, with almost thirteen hundred footnotes, establishing individual criminal responsibility for war crimes carried out during the regime’s 2012 siege of Baba Amr, a neighborhood in the southern part of Mustafa’s home city, Homs. Other cases have centered on torture in detention facilities; this is the first Syrian war-crimes brief that focusses on the conduct of hostilities, and it spells out, in astonishing and historic detail, a litany of crimes, ranging from indiscriminate shelling to mass executions of civilians who were rounded up and killed in warehouses and factories as regime forces swept through. The Homs Brief—for which Mustafa collected much of the underlying evidence—also assigns criminal responsibility to individual commanders within the Syrian Army’s 18th Tank Division, which carried out the assault.

“He thought he was contributing to a better Syria,” Wiley said. “When—and what it would look like—was unsure. But he believed in what he was doing. He could have fucked off years ago. We probably could have gotten him to Canada. We talked about it, because one of his daughters had a congenital heart issue.” Nevertheless, he stayed.

Last year, Mustafa bought an apartment on the eleventh floor of a new tower block in Antakya. Rula’s aunt moved into the same building, a couple of stories below. Her parents left the defected officers’ camp and moved into another apartment block, a short walk up the road. A few months later, Mick recalled, “Mustafa said to me, ‘When I’m at home with my family, it doesn’t matter what’s happening outside—it doesn’t matter if there’s a war. When I’m at home, I’m at peace.’ ”

Last December, Mick was visiting Mustafa’s apartment when the floor began to shake. “It spooked me—it was my first time feeling this kind of tremor,” Mick recalled. Mustafa laughed and said that they happen “all the time.” Then he went to check on Rula and the children, who reported that they hadn’t even felt it.

A couple of months later, Mick awoke to news of the catastrophic earthquake and tried to call members of his Syrian team. But the cellular networks were down in Antakya, and it was impossible for him to travel there, because the local airport’s runway had buckled, along with many local roads.

Saadeddin’s sister was dug out of the complex alive; her husband survived as well, but died in a hospital soon afterward, without anyone in the family knowing where he was. On the fourth day of search-and-rescue operations, Mustafa’s passport was found in the rubble. Then his laptop, then his wife’s handbag. “When they found the bodies,” Omar said, “Mustafa was hugging his daughter, his wife was hugging their son, and the other two children were hugging each other.”

Omar spent the next several days sleeping in his car, along with his wife and six children. Thousands of aftershocks shook the region, and, by the time I met with him, a few hundred metres from the Syrian border, he was so rattled that he reacted to everyday sounds as if they might signal a building’s collapse. His breath was short and his eyes welled with tears; Mustafa had been one of his best friends, and he had also lost eleven relatives to the quake, all of whom had been displaced from the same village in northern Syria. Then his young son walked into the room, and he turned his head. “We try to hide from our children our fear and our grief, so that they don’t feel as if we are weak,” he said.

A few weeks after the earthquake, there was an empty seat at a prestigious international-criminal-investigations course, in the Hague. Mustafa had been scheduled to attend. “We can mitigate the effects of war, except bad luck, but we didn’t factor an earthquake into the plan, institutionally,” Wiley told me. Mick coördinated humanitarian assistance for displaced investigators, and, as Wiley put it, “the operational posture came back really quickly.” Omar has now taken over Mustafa’s leadership duties. “Keep in mind how resilient this cadre is,” Wiley continued. “They’re already all refugees, perhaps with the rare exception. They had already lost their homes, lost all their stuff.”

It was the middle of April, more than two months after the quake. Much of Antakya had been completely flattened, and what still stood was cracked and broken, completely abandoned, and poised to collapse. Mick and I made our way through the old city on foot; the alleys were too narrow for digging equipment to go through, and so we found ourselves climbing over rubble, as if the buildings had fallen the day before. The pets of those entombed in the collapsed buildings followed us, still wearing their collars—bewildered, brand-new strays.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is the Role of Demolition Contractors in Renovation Projects?

Demolition contractors play a critical role in construction and renovation projects. They are responsible for safely and efficiently bringing down buildings or structures. The process of demolition involves careful planning, expertise, and specialized equipment. Here’s a breakdown of how professional demolition contractors work.

Initial Assessment

Before any demolition work begins, contractors conduct a thorough assessment of the structure. This stage is crucial for determining the safest and most efficient way to proceed. Contractors look at:

The size and height of the building.

Materials used in the construction.

Surrounding buildings or obstacles.

Utilities such as water, gas, and electricity. They will also assess potential hazards, such as asbestos or harmful chemicals, that may need special handling.

Planning the Demolition

Once the assessment is complete, demolition contractors create a detailed demolition plan. This plan outlines the sequence of steps for taking down the structure. It includes safety measures, equipment needed, and the best method for the demolition. Common methods include:

Mechanical demolition – using machinery like excavators or wrecking balls.

Implosion – controlled explosions that bring down the structure in a planned way.

Deconstruction – dismantling the building piece by piece, often used for recycling materials.

The plan also considers environmental factors, such as noise and dust control, and ensures the demolition complies with local laws and regulations.

Obtaining Permits

Demolition work requires various permits from local authorities. Contractors handle this process by submitting detailed plans to local government bodies. The permits ensure the demolition follows safety standards and environmental guidelines. Without proper permits, the project cannot proceed.

Safety Preparations

Safety is a top priority in demolition work. Contractors implement strict safety measures to protect workers, nearby residents, and properties. This may involve:

Setting up barriers to keep unauthorized people away from the site.

Alert neighbors and provide information on the demolition schedule.

Wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) like hard hats, goggles, and gloves.

Establishing emergency protocols in case of accidents or unexpected situations.

Additionally, utilities like gas, electricity, and water are disconnected to prevent any risks during the demolition.

How to Choose the Right Equipment?

Professional demolition contractors use specialized equipment based on the type of demolition. Common tools include:

Excavators are equipped with hydraulic attachments to tear down buildings.

Wrecking balls for large structures, though this is less common today.

Crushers and shears for breaking down concrete and steel. The choice of equipment ensures the job is done efficiently and safely.

Executing the Demolition

Once everything is in place, the actual demolition work begins. Contractors follow the demolition plan, working methodically to take down the structure. In mechanical demolition, machines start tearing down walls and breaking up concrete. For implosions, explosives are strategically placed, and the building collapses inward.

During the demolition, contractors constantly monitor the process to ensure everything goes according to plan. If issues arise, they are addressed immediately to prevent delays or accidents.

Waste Management and Recycling

After the demolition is complete, debris must be handled properly. Professional demolition contractors prioritize waste management and recycling. Materials such as steel, concrete, and wood are often separated for recycling or reuse, reducing environmental impact and lowering the cost of waste disposal.

Contractors use dumpsters, trucks, and sorting equipment to manage the debris efficiently. Hazardous materials, if any, are handled carefully and disposed of according to legal requirements.

Site Cleanup

Once all the debris is cleared, the site is cleaned thoroughly. Contractors ensure that the area is free of hazards and ready for the next construction phase. Depending on the requirements, the ground may be leveled or prepared for new building projects.

Conclusion

Professional demolition contractors bring expertise, precision, and safety to every project. From the initial assessment to site cleanup, their work ensures that structures are taken down, controlled, and efficiently. By following strict safety protocols and using the right equipment, demolition contractors minimize risks and prepare the site for future development.

0 notes

Text

The following types of walls are generally found in building construction.

Types of Walls:

Load Bearing Walls - Precast Concrete Wall, Retaining Wall, Masonry Wall, Pre Panelized Load Bearing Metal Stud Walls, Engineering Brick Wall, Stone Wall

Non-Load Bearing Wall - Hollow Concrete Block, Facade Bricks, Hollow Bricks, Brick Walls, Cavity Walls, Shear Walls, Partition Walls, Panel Walls, Veneered Walls, Faced Walls.

Given below, the details of these walls.

Load Bearing Walls: Load bearing wall belongs to a structural component. It bears the weight of a house from the roof and upper floors and transmits the weight to the foundation. It provides support to the structural members like beams, slab and walls situated over floors. A wall that is situated directly over the beam is known as load bearing wall. The purpose of load bearing wall is to bear the vertical load. On contrary, if a wall doesn?t contain any walls, posts or other supports directly over it, it is prone to be a load-bearing wall.

Load bearing walls also bear their self weight. This wall is normally situated over one another on each floor. Load bearing walls are utilized as interior or exterior wall. This type of wall will often be perpendicular to floor joists or ridge. Concrete is a useful material to support these loads. The beams enter directly into the concrete foundation. Load bearing walls inside the house is likely to run the equivalent direction as the ridge.

Various types of load bearing walls:

Precast Concrete Wall, Retaining Wall, Masonry Wall, Pre Panelized Load Bearing Metal Stud Walls, Engineering Brick Wall, Stone Wall.

Non-Load Bearing Walls: Non-load bearing wall means a wall that doesn?t allow the structure to stand up and retain itself. It doesn?t deal with floor roof loads over. It is a framed structure. Normally, these belong to interior walls whose purpose is to separate the structure into rooms. They are constructed lighter.

Read more

0 notes

Text

Global Roofing Chemicals Market Assessment, Opportunities and Forecast, 2030