#eddie: crosses the california state border

Text

something that's really interesting about the 9-1-1 canon timeline is that the first time buck's developing cooking skills are mentioned is in 204 and 204 is the episode directly after the 202/203 arc where he learns about eddie being a single dad and while it could be argued that buck's relationship with cooking is meant to be tangible evidence of his growth and maturity as well as a plot device to signify his father-son relationship with bobby, I personally like to think that sometime around when eddie first joined the station, or maybe even a little bit before, some intrinsic kill bill siren started going off in his head and the housewife instincts in him rose like a phoenix from the ashes

#eddie: crosses the california state border#buck: yes I do the cooking yes I do the cleaning#evan buckley#eddie diaz#buddie#weewoo brainrot#911 abc

525 notes

·

View notes

Text

Several Sentences Sunday

Thank you @cal-daisies-and-briars for tagging me!

Apparently I can share small bits of my Big Bang fic and since that's been my focus for the last month and a half, here it goes!

--------

Eddie placed his paws carefully, climbing his way up a narrow ridge of rock. Cold, steady rain hit his muzzle and blurred his vision, but he kept moving.

He wasn’t on this journey for himself.

He was doing this for Chris. For his son.

For Chris he would cross deserts and climb mountains.

They had done exactly that over the past few weeks. Making there way from Texas, west through the New Mexico and Arizona. They’s crossed the border into California over a week ago.

California had been Eddie’s biggest worry. Even now, after a week of skirting by towns and going unnoticed, he still worried.

Texas had several large packs who fought over territory, but the El Paso pack he and Chris had left was close enough to the border that they had been able to sneak away and out of the state without anyone tracking them down. New Mexico and Arizona were mostly unclaimed, no packs were known to be fighting over territory there.

California, though... battles between warring packs in California were bloody enough that news of the casaulties and destruction made it all the way to Texas.

In the typical duality of the world, for all its reputation for violence and unrest, California was also home to one of only four known safe havens in all of the North America, only two of which were in what used to be the United States.

-----

And that is a peak at my Big Bang fic, which will be very long and will likely undergo man edits over the next few months.

I tag: @ongreenergrasses, @lindstromm, and anyone else who'd like to join in (I don't know who's writing these days...)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

ILLINOIS Migrant motorist law now in effect

Some in state via Texas are now eligible for state driver’s licenses

CHICAGO — Motorists who are not U.S. citizens will be able to acquire a standard Illinois driver’s license as the result of a law meant to alleviate a stigma for immigrants in their interactions with law enforcement and expand their abilities to seek consumer services.

youtube

In addition, an annual state gas tax hike tied to inflation kicks in, bringing the levy to 47 cents a gallon while the diesel fuel tax climbs to about 55 cents a gallon.

The roughly 3% increases over last year are part of a 2019 measure that doubled the gas tax to help pay for Gov. J.B. Pritzker’s $45 billion Rebuild Illinois construction program.

The state’s decision to grant standard driver’s licenses to noncitizens comes as Illinois takes an increasingly progressive stance toward immigration, an issue that has divided the nation and become a major flashpoint as migrants crossing the southern border have been shipped to Chicago by Texas Gov. Greg Abbott.

Pritzker signed the driver’s license measure into law shortly after it passed through the Democrat-led General Assembly during the 2023 spring legislative session.

It puts Illinois in line with states like California, New York, New Jersey and Oregon that have similar laws.

Secretary of State Alexi Giannoulias said the law promotes “equality and fairness” for motorists but also believes it’s “an unequivocal no-brainer” for other reasons.

“It’s critically important, and it comes down to safer roads, safer roads, safer roads,” Giannoulias said in an interview.

“Let’s make sure that they have a driver’s license, they pass a road [test], an eye exam and learn the Rules of the Road.”

Immigrant advocates have been trying to get Illinois to allow noncitizens to acquire some form of driver’s licenses since at least 2007, when then-state Rep. Eddie Acevedo, a Chicago Democrat, sponsored a bill to give special driving certificates to immigrants without citizenship.

0 notes

Text

The in-betweens

I type now with my laptop bouncing on my thighs, the keyboard occasionally coming up to meet my fingertips before they've even completed a keystroke. I sit sideways on a Greyhound bus, back against the window and feet poking into the aisle. I’d never dare be so antisocial, but there’s barely a soul here to disturb. It's half past midnight and seven other travellers roll northward with me, our cabin pitch-black save for the glow of laptops and phones.

The only two noises I can hear above the engine are the persistent squeak of the hardworking wipers and the distant notes from the driver's radio. The latter is turned way down to avoid waking anyone, the former a reminder of the insistent rain of the Pacific Northwest. This spring it will soften everything on shivering mornings and collect in puddles too pallid to reflect afternoon clouds. I haven’t seen all those mornings yet, with their drowsy dew, nor the fog that embraces sleepy afternoons, but I’ll live for a thousand days in this corner of the world and love it enough to hope to die here. Not to die the death of some tragic and tortured artist, but simply to have my bones lie in the ground and nourish whatever may come next. Some ultimate act of giving back.

I can’t make out what the radio is singing but there’s an easy way to find out. A strange quirk of the acoustics or the design of this coach is that you can hear that radio in the toilet at the back. There aren't speakers in the toilet, mind. No. Instead, the radio can be heard coming out of the toilet. Also coming up from that spooky, steel pit is a strange surge of warmth. I can offer no explanation for this, nor do I solicit one. It feels better not to think about it.

Everyone should use a toilet on a Greyhound at least once. It's like using a toilet in some sort of tank or submarine. It's smaller even than anything you'll use on most planes and it's glorious in how rudimentary it manages to be. For me, it’s a little like using a toilet on a trampoline and I’m content to halt my description there, except to add that I looked over at the tiny sink to see it had been deliberately blocked, a large black slab of metal screwed over it to emphasise just how much it could not be used. I stepped back out into darkness, my eyes ruined by the light, as we bolted out of Bellingham and made our way to the Canadian border.

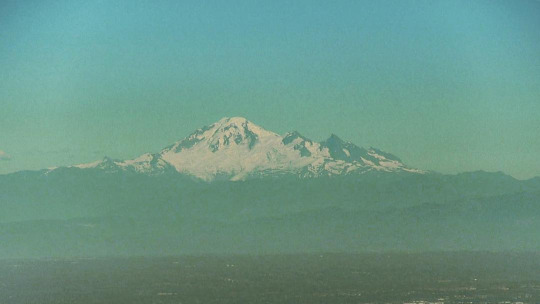

Outside, the world is nothing but colourless cutouts of tall pines and telegraph poles. If it were daytime, I might be able to see as far as the mountains and, in their foreground, the tiny and helpless humps of farms, barns and silos. The upturned teeth of the Cascades bite into the sky every day here. From the road they look like nothing more than the silent and sleeping guardians between the coast and a very different land beyond, but their serenity belies their jagged bodies and freezing peaks. It also gives no hint of a history in which, in the year of my birth and a mere fraction of a second ago in their grand geological lifespans, one of their cousins tore its face off in the largest landslide in recorded history, turned a lake to steam by drenching it in boiling rock and exploded so violently it threw its insides out at the speed of sound.

It’s impossible to imagine in the early hours of a new morning, on the first day of a new week, the merest hint that any natural violence has or could visit this corner of the world. Its forests are silent, its shores are peaceful and its old stones wear wrinkles of kindness. The biggest disturbances I feel are the irregularities of the road. The highways are straight, but they aren't always flat and every other mile is punctuated by a thump or a twitch.

There's a weird familiarity to all this, even if I've never been much of a coach traveller before. It's the half-tired, half-focused attempts to write, as I stare at either a screen or a sheet of paper, throwing down ideas and impressions before they dissolve inside the ever-broiling eddies of my brain. It's the abrupt distraction of some view or happening, like suddenly discovering I'm driving across the Port Mann Bridge. It's the nowhere places whose only identity is signs that point to somewhere else or their emptiness in the early hours. Places with other solo travellers, sleepy people happy to be alone, or perhaps with no choice but to press on to whatever destination is supposed to be accepting them. In the end, a bus station or train station or airport is exactly the same when it's all but empty, when it's only a node between where you're leaving from and where you need to be.

We are nowhere, the road reminds us. It reminds us in brash and blaring lights that advertise malls or food courts or department stores, or endless signs always pointing toward what’s next. This is where you should go, they all say in their bold and black lettering, to be somewhere. Anything to escape the now.

But I like this coach right now. It's dark. It's quiet. It's intimate. All that means it’s easy. It's been a while since I've had an easy trip, a trip where everything around me went away and I was left contentedly with myself. There's a kind of wooziness to everything, a dream-like state that I’ve slid myself inside of. No wonder I dream about travel so often, in one form or another. Dreams and travel are almost one and the same to me. Both are hyper-vivid, both slightly abstract, both full of details that are sharp, particular and even bizarre, the sort of things that you tell everyone about later while wondering if anyone will believe them.

The driver and his marshal are talking up front. They're exchanging stories about journeys across this side of the continent, journeys from California to Idaho. We prepare to cross a border. We cross a border. We drop two young women off in a suburb and then there are less than half a dozen people on an entire coach busy thumping and twitching its way through a dream. Travel is not departures and destinations, but moments. It's moments like these, the in-betweens, the bits that happen while you wait to see what comes next.

All these photos are (daytime) sights from journeys along routes like this one, from 2015 to 2017. This post was generously funded by my supporters on Patreon, who got to see it first last month and who get to see many others that aren’t released to the wider world. If you enjoyed this and would like to see more like it, please consider supporting my work there. Thank you!

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The New York Times: Who Are America’s Undocumented Immigrants? You Might Not Recognize Them.

Nearly HALF of the estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants now in the country did not trek through the desert or wade across the Rio Grande to enter the country; they flew in with a visa, passed inspection at the airport — and stayed.

Of the roughly 3.5 million undocumented immigrants who entered the country between 2010 and 2017, 65 percent arrived with full permission stamped into their passports.

Example:

Eddie Oh, an industrial engineer, lost his job during the financial crisis that gripped South Korea in 1998. With no prospects, he scrounged together his savings to pay his family’s airfare to California. They were going on vacation, he told the United States embassy, which issued six-month visitor visas for the family.

Over half million Indian independent programming contractors are only part of the story. Many undocumented Indians here in Sunnyvale have low-skilled service jobs, catering to their well-heeled brethren who frequent the Indian supermarkets, eateries and clothing shops that line El Camino Real, the main commercial corridor.

0 notes

Text

‘The American Dream has turned into hell’: In test of a deterrent, Juarez scrambles before U.S. dumps thousands of migrants

https://wapo.st/2MS4Cdj

Trump vows mass immigration arrests, removals of ‘millions of illegal aliens’ starting next week

‘The American Dream has turned into hell’: In test of a deterrent, Juarez scrambles before U.S. dumps thousands of migrants

By Maria SACCHETTI | Published June 17 at 6:53 PM ET | Washington Post |

Posted June 18, 2019 |

CIUDAD JUAREZ, Mexico — This gritty, industrial city on the banks of the murky Rio Grande is bracing for the Trump administration to dump thousands of migrants from Central America and other lands here under a new agreement to curb mass migration to the United States. But frantic Mexican officials say they likely cannot handle the rapid influx, as they are desperate for more shelter space, food and supplies.

With days to prepare, a top state official said he expects a fivefold increase in the number of migrants who will be sent to Juarez as a result of the expansion of the Trump administration’s Migrant Protection Protocols. The program, which is under court challenge, sends migrants who are seeking refuge in the United States back across the border into Mexico to await their asylum hearings.

More than 200 migrants were sent back to Juarez on Thursday, double the previous day, and officials expect as many as 500 migrants each day will be returned from El Paso to Juarez in coming weeks.

“We didn’t expect this many, but it’s our job and we’re trying to handle the situation,” said Enrique Valenzuela, head of the Chihuahua State Population Council, which registers migrants in Juarez. Valenzuela said Mexico’s federal government brokered the deal to accept the migrants with the White House, part of a diplomatic effort to avoid President Trump’s threatened tariffs on Mexican goods. “We had no say. We had no choice.”

Returning migrants from the United States into Mexico is the cornerstone of an agreement between the two countries to stanch historic flows of migrant families and unaccompanied minors into the United States. Migrant families with young children are overwhelming almost all aspects of the U.S. immigration system and are frustrating Trump’s campaign promises to block illegal immigration.

The agreement already is testing the infrastructure in Juarez, a city that is crowded and lacking in shelter space. Juarez has about a dozen migrant shelters — most run by churches — with room for 1,500 people.

That many people could be turned away from the U.S. border every few days, and Valenzuela said the city could use 20 to 30 more shelters to house potentially thousands more migrants.

Valenzuela estimated that as many as 70,000 migrants could be returned from the United States to Juarez this calendar year, a number that would equate to about 5 percent of the city’s population. Borderwide, Mexico has accepted about 10,000 migrants this year.

Trump threatened to slap increasing tariffs on Mexico unless the country stepped up immigration enforcement with the goal of preventing northward movement from Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador and several other countries with populations that are attempting to flee violence and extreme poverty. Since the June 7 agreement, Mexico has deployed police and newly created national guard units to the southern border with Guatemala, intensified highway checkpoints, and directed border cities to host asylum seekers who make it to the United States and are turned away.

Mexico’s crackdown aims to deter migrants from attempting to enter the United States, though officials say it is too soon to tell whether it has had any effect on the number of people crossing from Juarez into the southwest Texas city of El Paso. U.S. Border Patrol agents here in the El Paso region have not seen a significant dip in apprehensions since the agreement was signed, said Border Patrol Agent Ramiro Cordero. Agents arrested between 600 and 800 migrants each day in the past week, and migrants still cross the border so often that the sand is dotted with their footprints.

Some migrants said in recent days that the early stages of Mexico’s increased enforcement already has exposed vulnerabilities. Several migrants said in separate interviews that Mexican federal police and other public security forces had demanded bribes of $15 to $20 per person to pass through checkpoints and reach the U.S. border. As buses passed through in recent days, the bribes of hundreds of dollars meant their travel north was essentially unimpeded if Mexican authorities were paid off.

“They said if you want to enter you have to pay,” said Martha Velasquez, 54, of Honduras, who was planning to join her sister, a U.S. citizen, and their mother, a green card holder, in Atlanta. She was returned to Juarez after crossing the U.S. border. “This is extortion.”

Migrants in Juarez said returning asylum seekers to Mexico — if it becomes the inevitable result of trying to cross into the United States — could deter future migrants because conditions there are dangerous and inhospitable. Juarez, once the world’s murder capital, can be a frightening alternative for migrants who had dreamed of reuniting with friends and family in the relative safety of cities across the United States.

When the ramp-up began Thursday, stunned migrants, some of whom had spent days in border jails, trudged out of Mexico’s immigration office into the sweltering sun. Many had not showered in a week. They had no water, no cellphones, no money and no place to live.

“The American Dream has turned into hell,” said Damarys Perez Carrillo, 38, who said she fled Guatemala after her brother-in-law was murdered. She could not find her 22-year-old nephew Eddy, who was separated from her after they surrendered to Border Patrol in Texas.

“They’re sending us all back,” said Julio Alberto Lopez, a 45-year-old bricklayer from Guatemala who had paid $6,500 to a smuggler for safe passage through Mexico. With his son Abner, 14, he thought he would gain easy entry into the United States, because officials rarely deport families. But within hours, he was returned to Juarez.

“I thought they would give me a chance, with my son,” Lopez said.

‘WHAT ARE WE GOING TO DO ?

Many issues surrounding the anticipated influx remain unresolved: Migrants returned to Mexico are allowed to wait there for their hearings in U.S. courts — a period that sometimes spans months — but they do not have permission to work to support themselves. Many do not have relatives there who can take them in, as they do in the United States. Some are sick and in need of doctors or hospitalization.

“What worries me is that the city and the state, we’re not that prepared,” said the Rev. Javier Calvillo Salazar, who runs the city’s largest migrant shelter, Casa del Migrante. “That could plunge us into a crisis.”

Mexico is under intense pressure to help the U.S. Department of Homeland Security expand MPP, which is also known informally as “Remain in Mexico.” Returns could soar from 250 a day to 1,000 a day along the entire border from California to Texas.

One city that could see more returns is Piedras Negras, a city of 150,000 that sits across the border from Eagle Pass, Tex. The Mexican city has prospered via trade with the United States and has sought to mitigate the migration crush at the border in an effort to appease the U.S. government.

City officials helped block a caravan headed toward the U.S. border and has appointed a steakhouse owner, Hector Menchaca, to run a waitlist that requires migrants to take a number and get in line until the United States invites them in to apply for asylum.

But Menchaca said it would be “catastrophic” for the United States to force those migrants to return to Piedras Negras while they await a decision in the clogged immigration courts.

“What are we going to do on the border with all the migrants, waiting a year for their court date?” Menchaca said. “If they’re illegal, how are they going to work in Piedras Negras? Who’s going to feed them? Where are they going to go?

‘THE DREAM IS OVER ’

The U.S. Border Patrol’s El Paso sector, which runs from west Texas into desolate stretches of New Mexico desert, has seen some of the sharpest increases in apprehensions during the migration surge and is likely to see some of the largest increases in returns to Mexico, U.S. officials said.

In Juarez, where violent crime is widespread, migrants must decide whether to return home to their families or test their luck in a nation where they have no connections or support.

Of the 4,500 migrants returned to this city from March to June, municipal officials estimate about 40 percent return to their homelands at their own expense. Sixty percent remain in shelters, rented apartments or with friends.

“That’s where you really see it, the need,” said Rogelio Pinal Castellanos, the human rights director for Juarez’s municipal government. “There are people who say, ‘I’ll die of hunger in Juarez before I’d return to my country,’ because these are people who are really fleeing a critically violent situation. They fear for their lives. And there are those who tell us they’re going home to their country. Or their asylum petition is false.”

Advocates for immigrants caution that migrants with valid cases might flee Juarez because it is dangerous, and they do not have regular access to U.S. lawyers to build their asylum cases.

Ruben Garcia, executive director of Annunciation House, a migrant shelter in El Paso, said expelling asylum seekers is a “wholesale abdication” of the United States’ commitment to refugee protocols.

“This is about ‘keep them out,’ ” he said.

At Valenzuela’s state office this week, some dejected migrants were ready to give up.

“The dream is over,” said Ana Julia Rojas, 46, who officials returned to Juarez with her son Ricardo, 10, dressed in a Captain America T-shirt. She had her brother’s phone number in New York written in ink on her left hand.

Her time in immigration jail soured her on the United States: “I’m going back to Honduras. It’s a poor country, but we’re fighters.”

In a new shelter that opened Friday in a modern white house in Juarez, women shook their heads when Valenzuela asked if they wanted to go home.

One woman’s husband had been shot. Another woman fled an abusive relationship.

But they also did not want to stay in Mexico.

ALWAYS ANOTHER WAY

Hundreds of miles away along Mexico’s southern border with Guatemala, migrants were continuing to take risks to head north.

In Huixtla, 50 miles north of the Guatemala border, migrants waited to jump atop a northbound cargo train, just west of the nearest checkpoint.

“We were taking buses, but when we saw the checkpoints, we got off and left the highway,” said Kilber Saul, 17, from San Pedro Sula, Honduras.

Saul and his friend Jose Hernández, 21, had crossed the Suchiate river, between Mexico and Guatemala, a few days earlier. They said they were fleeing violence in their hometown, and the lack of opportunity for young people outside of organized crime.

On Friday morning, they were walking on the train tracks in Huixtla, their only plan to avoid being detained. Mexico’s surge in enforcement has focused on highways, leaving vast stretches of land — and railway — unpatrolled.

“Either we’ll keep walking, or, if the train comes, we’ll ride it,” Saul said.

Advocates said migrants will continue to find their way north until the United States and other nations address the reasons migrants flee their home countries: poverty, hunger, and a lack of security and opportunity.

“Here they put up a wall,” said Pinal Castellanos, Juarez’s human rights director, gesturing to the 18-foot fence that divides Juarez from the United States. “Has this stopped anything? No. People will always find another way, even if it’s risky.”

Kevin Sieff in Huixtla, Mexico, and Nick Miroff in Washington contributed to this report.

Maria Sacchetti covers immigration for the Washington Post, including U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and the court system. She previously reported for the Boston Globe, where her work led to the release of several immigrants from jail. She lived for several years in Latin America and is fluent in Spanish.

#donald trump#u.s. news#politics#trump administration#president donald trump#trump#republican politics#white house#politics and government#international news#trump scandals#republican party#immigration#borderwall#racism#national security#must reads#elections#maga#civil-rights#democracy#immigration reform#mexico#humanitarian crisis

0 notes

Text

A California Law Is Helping Immigrants Wipe Slates Clean

By reclassifying certain nonviolent felonies as misdemeanors, Prop. 47 has helped undocumented immigrants with criminal records. Even one day of a sentence reduction can make a difference between being deported or not.

“If you plead guilty, you will get out of jail very fast. I guarantee.”

Stephanie Flores, Eddy Zheng and a woman named Lucero all heard this exact phrase from their respective public defenders following arrests for different crimes committed in California. Confused, scared and without the ability to pay a private lawyer, they entered the criminal justice system with an additional handicap: Because they were undocumented immigrants or were in the process of gaining lawful permanent status, their criminal convictions put them on the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) priority deportation list.

“We have the burden of being undocumented, not being able to afford bails and knowing little about how to clean our records,” says 30-year-old Stephanie Flores. She arrived from Puebla, Mexico when she was a year old, together with her mother and four siblings. Flores’ sweet voice speaks volumes behind a seven-month pregnant belly. As a community activist, she recently learned how to become a ‘lobbyist,’ driving every week from her San Jose home to Sacramento to call on legislators to enact bail-bond reform. Although the measure was defeated, Flores continues campaigning in Santa Clara County to end its money bail system.

Flores is a Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) recipient, a benefit that protects from deportation about 1.2 million young undocumented immigrants who entered the United States as children. She could graduate as a communication specialist at San Francisco State University. She was, however, accused of first-degree robbery and assault and battery, after a January altercation with a waitress at a Santa Clara restaurant. According to court records, the waitress accused Flores of beating her and stealing money from the register.

Flores spent a month imprisoned at the Elmwood Correctional Facility Jail in Milpitas, alongside 50 other women, mostly Latinas and African Americans. “We didn’t have enough beds or potable water available; drugs fly free inside prison and we were treated like animals,” she recalls. Her bail was set at $100,000 – a sum normally suggested for kidnapping and voluntary manslaughter cases.

While in jail, Flores lost her apartment for nonpayment of rent and her car was impounded.

“I was afraid that my baby was going to be born in jail and that if I were sentenced for any crime, I could be deported,” she says. After six months of preliminary hearings, Stephanie was charged with petty theft, which is now considered a misdemeanor under Proposition 47, a 2014 measure approved by California voters. Prop. 47 reclassified certain nonviolent felonies as misdemeanors, including simple drug possession, petty theft and shoplifting. It works retroactively, so individuals can apply to have their sentences reduced or their records changed, regardless of when their convictions happened.

A felony conviction can bar immigrants from applying for a permanent lawful status and increases the risk of deportation.

Every year, according to Hillary Blout, a staff attorney with the Oakland-based nonprofit Californians for Safety and Justice, 3,300 fewer people are incarcerated due to Prop. 47, and more than a million have benefited from having their criminal records changed. There are not specific numbers on immigrants benefiting from the measure.

California has one of the largest prison populations in the country, and Latino and African American males together make up three of every four men in prison, according to the Public Policy Institute of California. Each person sent to prison costs the state $70,000 a year and, since 1980, California has built 22 prisons against only one new university. The cost of operating the state prison system in California is $10.5 billion annually, while, explains Blout, 49 of the state’s 58 counties have no public residential drug treatment programs.

People with criminal convictions face almost 5,000 restrictions: Although in California former felons can re-register to vote, they lose the right to public assistance, housing, education, jobs — and even parental rights are terminated. For immigrants, a felony conviction can bar them from applying for a permanent lawful status and increases the risk of deportation.

On the other hand, “reducing a felony to a misdemeanor can remove undocumented immigrants from an ICE “enforcement priority” list, explains Rose Cahn, the Criminal and Immigrant Justice Attorney at San Francisco’s Immigrant Legal Resource Center (ILRC).

When Eddy Zheng walked out of San Quentin after 19 years inside, ICE detained him for deportation.

“Although every undocumented person could be targeted for removal, she or he could [theoretically] apply for lawful immigration status – i.e., through U.S. citizen family members,” Cahn says. “But, certain criminal convictions can foreclose this path. There is a permanent failure in the justice system to warn immigrants about the consequences of plea bargaining.”

Lucero, 38, who did not wish to give her last name, was born in Michoacán, Mexico and grew up in a small village facing constant shortages of water and electricity. At 16, she crossed the U.S. border.

“I was very young and didn’t have any idea what ‘illegal’ meant,” she recalls today in her San Jose home. “People don’t know how powerful and devastating that word. is.” Lucero barely finished second grade in Mexico because she started working at an early age. She was taught, paradoxically, that school was for lazy people. “Enrolling in high school in California was a big shock for me… I left the classes and started to work in a kitchen-products company from 1995 to 2014, when I was arrested.”

Lucero suffered from alcoholism, which became a source of violent encounters with her former partner, who filed a restraining order and accused her of a cellphone robbery. “I spent just three days in jail but it was the most humiliating experience,” she adds. “I couldn’t make a call and my 17-year-old son kept waiting for me at his school. The next time he saw me I was wearing an orange suit and handcuffs in court.”

Lucero had to attend anger management classes, was ordered 30 hours of community service and to report herself every Monday to a probation officer over the course of a year. She didn’t know this situation put her closer to deportation, although she has been in a successful rehab program. “I lost my home and spent three months in a profound depression,” she says. “I have applied for jobs but didn’t get those due to my criminal record. Now I am working with a lawyer to expunge it.”

Flores and Lucero are receiving help through the Participatory Defense System, a model for communities to impact the outcome of court cases, by partnering with, or pushing public defenders, “to shine a light on felons’ humanity and potential,” according to the group’s website. Implemented six years ago in San Jose by Silicon Valley De-Bug, the model teaches families and community members how to gather pictures, family trees, school and medical records, and how to dissect police reports and court transcripts. “The idea is to build a sustained community presence in the courtroom to let judges and prosecutors know the person facing charges is not alone,” says De-Bug co-founder Raj Jayadev.

For undocumented immigrants, this system has proved more successful than free legal clinics and Live Scan events — where people get fingerprinted — which are more tailored for connecting former prisoners who are citizens with various resources. Immigrants are often afraid of showing up in public places and being detained by ICE, given the current increase in raids for deportation purposes, since the beginning of Donald Trump’s administration. “We use more word of mouth than big advertisement,” says Cahn from ILRC. “Through counties like Santa Clara or organizations like Silicon Valley De-Bug, we host clearing-record opportunities where immigrants can request a copy of their rap sheets and have legal assistance”

Although Flores and Lucero are cleaning their records through Prop. 47, the attorney notes that this is only one instrument in the toolbox of remedies known as post-conviction relief. Immigrants can go back into criminal court and alter their convictions through reduction, vacation (challenging a conviction’s legality) or expungement (removing the offense). Clean Slate programs at public defenders’ offices also help people to clean up their criminal records.

“We’re training legal service providers in how to implement these laws because even one day of a sentence reduction can make a difference between being deported or not, or having access to other benefits like DACA, asylum or U visas [for victims of crimes],” says Cahn.

Data from the Department of Homeland Security show that from 2006 to 2015, the number of people deported as a result of criminal convictions has increased gradually, hitting a record of more than 200,000 removals in 2012. In 2016, 58 percent of all ICE removals, almost 140,000 people, were convicted criminals.

The contrast in immigration politics between California’s and the federal government’s is stark. United States Attorney General Jeff Sessions instructed federal prosecutors to throw the highest possible charges at those who commit minor crimes, while doubling penalties in mandatory minimum sentencing laws that judges can not reduce, even with mitigating circumstances.

“The system has a strong impact on Latino families” notes George Galvis, 43, executive director of Communities United for Restorative Youth Justice. “If someone has a DUI conviction or a drug possession, that may complicate their immigration case. I’ve seen families torn apart for minor offenses.”

Galvis himself was incarcerated at age 17, charged with multiple felonies for his involvement in a drive-by shooting. Born and raised in the Bay Area but from a Peruvian family, Galvis witnessed how his father tried to kill his mother, and says he was bullied at school for being a student of color.

“Teens who lived like me understand the concept that hurting people hurts more people; while healing people heals more people,” says Galvis, who focuses his advocacy work on at-risk youth, prisoners and formerly imprisoned individuals with children. “We need to stop the cycle of sending young people to prison, especially minorities of color, without offering them something different than punitive discipline.”

Eddy Zheng was charged as an adult for participating, as a minor, in a 1986 home-invasion robbery and kidnapping. At the age of 16, four years after immigrating with his parents and two siblings from Guangzhou Province in southern China to Oakland’s Chinatown, he was convicted and sent to San Quentin State Prison.

“In jail I taught myself English through reading novels, and helped other young prisoners with counseling,” he says in Oakland, where he works with the Asian Prisoner Support Committee, helping youth at risk. He spent a total of 19 years in prison, until his 2005 release. When he walked out of San Quentin, ICE detained him and put him under a deportation procedure.

“I spent 23 months in Yuba County Jail and when released I had to wear an ankle monitor for a month, and check in with a probation officer three times a week.”After another eight years of immigration hearings, letters from prominent members of the community praising his rehabilitation and contributions to society, appeals, habeas corpus motions and a pardon petition to then-Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger that was denied, Governor Jerry Brown finally granted Zheng a full pardon in 2015.

“Many undocumented people qualify for post-conviction relief and they are fearful to come forward, afraid that their names show up in an ICE database if they look for legal assistance,” says Zheng, for whom the big challenge with the system is fighting misinformation. “We are here to show them solidarity and to change the narrative of the formerly incarcerated. They too have rights.”

Originally published here

#Immigration#English#California#Misdemeanors#Criminal justice#undocumented#deportation#USCIS#ICE#criminal records#DUI#prison

0 notes

Text

Pot Tourism Hasn’t Changed the Oregon Economy But It’s an Ancillary Service

In a May 17, 2017 photo, marijuana buds are available at Touch of Aloha Cannabis Dispensary outside Depoe Bay along the Oregon Coast. The state has licensed pot dealers in every Oregon county bordering the Pacific Ocean, with the highest number near the beach here in Lincoln County, state data show. Anna Reed / Statesman-Journal via Associated Press

Skift Take: Tourists can add buying weed to their things to do list when traveling the Pacific Coast of Oregon. Pot tourism isn't transforming Oregon tourism — just think of it as an additive to the state's diversity of offerings.

— Dennis Schaal

Eddie Biggar sports a black-and-green suit dotted with tiny green leaves as he dances jovially on a corner of the Pacific Coast Highway.

Some two-and-a-half hours southwest of Portland in Newport, Oregon, he owns the sidewalk. Just like a sign-waver might promote the local pizzeria, The Weedman boasts $5 grams, urging customers down the street to CannaMedicine.

The state has licensed pot dealers in every Oregon county bordering the Pacific Ocean, with the highest number near the beach here in Lincoln County, state data show. But there’s little so far to suggest marijuana is changing the coastal economy, which is already largely fueled by tourism.

Still, there’s no question many out-of-towners are heading into coastal pot shops. Retailers say they’ve seen people from China, Mexico, the Dominican Republic and South Korea.

“I’ve never seen so many different IDs in my life,” Shane Ramos-Harrington said in Touch of Aloha, his Hawaii-themed marijuana outpost in the area of Depoe Bay, a community boasting the “world’s smallest harbor.”

In the sales room, a chalk board displaying daily deals promised a 5-percent discount to customers outfitted in Hawaiian shirts.

Ramos-Harrington came from Oahu and opened the business, now looking to spread a little aloha to Oregon. That means putting energy into people — if they come into his store upset, hopefully they’ll leave happy.

Oregon’s stretch of oceanfront is no Southern California doppelganger. Regular dark clouds over the ocean and towns sometimes make it feel like the sky sits on people’s shoulders. The sun rises over thick forests in the morning, setting over the water come evening.

“If you brought a swimsuit to the Oregon Coast, don’t worry, someone will loan you a sweater,” the Oregon Tourism Commission assures.

Near the coastal town of Yachats (yah-hawts), where hills cascade toward the ocean and visitors can buy crab fresh off the boat, Deb Cardy opened her uncluttered home for business.

Northeast Forest Hill Street branches off U.S. Highway 101 like a pine needle on a branch — that is, if the branch crossed through three states.

Hang a left onto the dirt street and you’re practically at Cardy’s front door. The nearby ocean is her white noise. “You can hear the seals barking at night,” the 61-year-old said.

Cardy has found a market for those wanting a place to stay the night and partake, with one of only five cannabis-friendly lodgings in Oregon listed on website Kush Tourism. She is running a new kind of bed-and-breakfast: a 420-friendly house within earshot of the Pacific.

She keeps hints of how welcome the crop is scattered around her house: “The Cannabis Kitchen Cookbook” on a counter; a small green cross above the numbers 420 and a smiley face on a wooden sign in her window; and three jars of her stash on a shelf near the front door.

“You don’t have to have marijuana leaves on everything,” she said.

The house is a one-story setup built in 1938 on enough land for her Artic Wolf-Huskie mix, Mia, and a fire pit.

Cardy came to this laid-back patch of Oregon after working almost four decades as a Colorado property manager.

“This is the most relaxing thing that you can do,” she said.

Cardy, a medical marijuana patient, said she first used at age 12.

She wants to join other property owners up and down the coast to give vacationers a comfortable way to enjoy weed and the water.

“I live in one of the most beautiful places on the planet,” Cardy said. “Why would I not want to share it?”

Larry Aguayo booked a stay with his wife last year.

Aguayo, a drummer, did a wedding gig about half an hour away in Newport, a much bigger city north of Yachats. They roomed at Cardy’s afterward.

“It was just like being at home, knowing that we can go in there, we could medicate, not having to worry about going outside in the rain,” Aguayo said. “At the motels, you’ve got to go outside.”

During the trip, the Myrtle Creek, Oregon, couple also celebrated their anniversary at Cardy’s place, which now runs $110 a night on home-sharing website Airbnb.com.

When they arrived, Cardy was ready to make dinner for them, Aguayo said, and there was a “big fat apple pie just like Mom makes.”

And snacks in the bedroom, his wife Cindy said.

Larry Aguayo said: “Snacks. That’s a big thing. In the 420 world, we like to eat.”

A wave of retailers followed in the wake of the crop’s legalization here, even though it remains federally illegal.

At Pipe Dreams Dispensary in oceanfront Lincoln City, a map on an interior wall inviting visitors to stick a pin in it to mark where they’re from shows people come in from all manner of countries: Canada. India. Saudi Arabia. Spain.

Anyone can buy marijuana if they’re old enough and have identification, Pipe Dreams owner Randy Mallette said.

“They can buy it, but there’s nowhere for them to enjoy it. They can’t take it to a hotel room,” Mallette said. “Maybe if they get an edible — but vaporizing, smoking and that whole culture is muted in a way.”

___

Information from: Statesman Journal, http://stjr.nl/2fka4W4

Copyright (2017) Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed.

This article was written by Jonathan Bach from The Associated Press and was legally licensed through the NewsCred publisher network. Please direct all licensing questions to [email protected].

0 notes