Hello! I'm Paul Dean, a writer, games designer and narrative designer, journalist and speaker. I have a Patreon which funds much of the independent work you read here. I'm known for features such as the hugely successful A Year in Stardew Valley and On Poverty, for my writing on video games like Pacific Drive or Maia, or on a host of tabletop games that include Paranoia, Feng Shui 2 and Magical Kitties Save the Day. You might've caught me speaking at the Games Developers Conference or another convention, at a university or on the radio, know me as a founder of Shut Up & Sit Down and the SHUX convention, or read one of the thousands of things that I've written over the years. If you'd like to get in touch, email me at paullicino at gmail.com. You can sometimes catch me on BlueSky, Twitter (sparingly) and Instagram, too. As well as posting my work here, I share blog posts (such as 2016's Wednesday Blog) and occasional reflections on my Favourite Things. If you enjoy my work and supporting my Patreon doesn't appeal, you can instead drop something in my PayPal tip jar. Thank you so much! I'm interested in how information propagates and changes, science fiction, technology, philosophy (which I studied), progressive causes, games of all types, how the internet changes our culture, Forteana and lots more besides. People I like include Kurt Vonnegut, Ursula Le Guin, Anne Frank, Carl Sagan and every bear.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

On Fascism

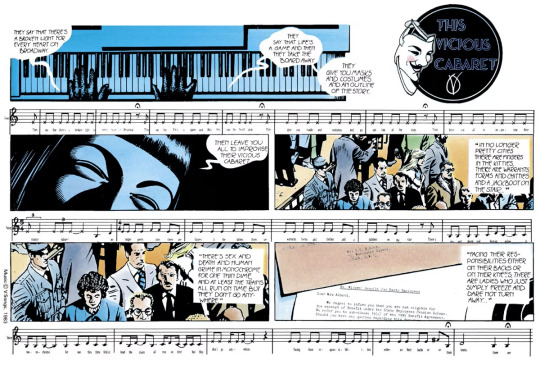

(Image credit: V for Vendetta, Lloyd/Moore. Larger version available here.)

Taken from my Patreon and originally posted on January 20th.

Even before I was born, so much of the arc of my life had already been defined, already been set out, as a result of actions taken by fascists. The dates of birth of most of the siblings on my mother’s side of the family were measured out, with a nine and a half month delay, exactly according to the dates of my grandfather’s shore leave from the Royal Navy. Their births correlated with the times he was not at sea, fighting fascists who had spent several years trying to take over Europe. The war was of such scale that, even at home, everyone was still on the front lines. My grandparents’ relocation to a port on the south coast meant nobody was home when a representative of the Luftwaffe’s Urban Redevelopment Committee hurled a bomb down into the neighbourhood that damaged the family house (including, to my grandfather’s consternation, blowing the door clean off). The necessity of the fight against the fascists had, ironically, moved my family out of harm’s way.

The Luftwaffe would continue making sweeping changes to the urban geography of London, as well as several other British towns and cities, for quite some time. Enough so that, by the time I came to live in the city, decades later, a significant amount of its infrastructure existed as a direct result of efforts to rebuild and redesign. The consequences of fascist aggression were not abstract and historical, they were physically present in the world around me, much as they were directly responsible for guiding the growth and the branching of my family tree. Without twentieth century fascism, I might have been born at a different time. I would certainly have explored a differently designed country and even flown out of different airports that would have existed in different places, rather than have developed from the legacy of my nation’s air defence demands.

The Europe that those airports took me to would have looked different. Cities like Paris or Prague wouldn’t have had to advertise themselves as unspoiled, a word that we all knew meant you’d been spared remarkable new forms of warfare such as blitzkrieg or carpet bombing, where fascists found ways to wage war even faster and even fiercer, our continent their canvas. The people I met in many interesting journeys over many years would have told me different stories, none of which would have involved how their country was occupied or attacked. A man in Norway wouldn’t have told me how his family had to hide a gun under a tea cosy during a surprise visit by members of the fascist garrison. Veterans in Denmark wouldn’t have told me how they can’t forget what a burned body looks and smells like. Malta would not wear a medal on its flag after the small island spent years suffering some of the most intense air attacks of any place on the planet.

Fascists love to project power, and by far the most significant part of that projection effort involved the widespread use of force across Europe, manifested in generous bombing, shelling and demolition efforts. This was served alongside that new cocktail known as blitzkrieg, which combined lavish helpings of air and land forces mixed in with new military technologies to quickly seize land and objectives. Like London, a wealth of towns and cities were dramatically redesigned by this historic effort, resulting in the patchwork present we all grew up with. And, of course, countless hundreds of millions of lives were changed as a result of everything from deployment to displacement, not to mention the tens of millions who died in combat, as a result of collateral damage, or as a result of state sanctioned genocide.

Fascists have to project power, have to manifest aggression, because otherwise they can’t get things done. They can’t achieve what they want. They are bad at exercising logic, reason or empathy. They are bad at co-operation or compromise. Other people don’t want the things that the fascists want, so they have to use force, manipulation and coercion. Sometimes a lot, an awful lot. Maybe even a whole continent’s worth of people don’t want what the fascists want, so the fascists respond with continent-wide, even world-wide force, manipulation and coercion. It doesn’t matter how many people oppose the fascists. They’re fascists, so they think they’re better.

Fascists aren’t very good at self-reflection.

Fascists reshaped the twentieth century the only way they knew how, which was through this pugilistic persistence, through trying to punch their world into the shape that they wanted it to be, like a boxer trying to attack clay with the belief it will become a statue. Their legacy is craters and body counts and death camps and occasionally the shapes of sunken ships that are laid bare by low tide. Most of the things that they focused their efforts on, the technologies or ideologies they bent their brains toward, were things designed to punish, subjugate or kill anyone they decided was an opponent. Those opponents were other kinds of people, not only in other nations, but also in their own, should those people be deemed too different, or even simply dissenters. Conformity was really important to the fascists. Everyone should get along like one big, happy family. One, big, wholly identical, eternally harmonious family.

Fascists love to project conformity. And obedience. Neither of which tend to encourage criticism, compassion, analysis or new ideas. In fact, projecting power and conformity and obedience creates a culture of punishment. I guess punishing people makes you feel strong. And like you’re getting somewhere.

Their opponents, by their own definitions, turned out to be an awful lot of people. I’m going to step out on a limb here as I suggest that attempting to subjugate or to kill people, especially increasing numbers of them, might just alienate a lot of folks.

The fascists, projecting all that force, manipulation and coercion in all kinds of directions, all that power and conformity and obedience, were not very clever and, as their legacy shows, not very successful. It was a bad idea for them to try the things they tried and it caused a lot of problems for a lot of people, though ultimately the fascists found themselves among those suffering the most. They didn’t have the foresight to anticipate this. They didn’t possess the self-reflection to stop. They didn’t tolerate the kind of dissent and disagreement that would have allowed the development of any other ideas beyond their own very narrow, very tiny philosophy.

The fascists weren’t very clever and, unfortunately, they kept hating all the people who were clever. The people able to use empathy and intelligence and deduction and reasoning and data and research and patience and analysis and debate and discussion to point out when and where the fascists were wrong, over and over and over. It seems pretty obvious to me that repeatedly getting rid of anyone or anything that disagrees with you, whether a person or a piece of information, is a terrible idea. You will end up with people who are unable or unwilling to object. You will lose all perspective.

In spite of their carpet bombing and their blitzkrieg and their blowing the door off my grandparents’ house, the fascists were defeated by a combination of co-operation, innovation and their own colossal stupidity. The co-operation came from a remarkably diverse alliance of nations and peoples working together to use everything that they had, including widespread resistance in the countries the fascists occupied and even in their homelands. The innovation came from all these many different people offering new ideas and new technologies, some of which were even developed by people that the fascists had hated and alienated and tried to silence, discredit, expel or kill. The stupidity, as you can probably guess, also came from the fascists trying to silence, discredit, expel or kill just so, so many people who disagreed with them. Over and over. Like they were engaged in some sick, extremist form of absurdist performance art. Their inability to self-reflect, disagree or handle dissent lead to the fascists making a series of monumentally batshit fucknut book-of-records-level-idiot decisions across the years. Over and over. Their greatest hits included such things as invading new territories in which they didn’t have the strength to fight, ignoring such obvious strategic elements as predictable but horrific weather or the challenge presented by bodies of water, changing their minds constantly, hurling time and money after stupid projects or inventions, disregarding battle projections or reports they didn’t like, failing to follow through on plans, failing to correctly provision themselves for conflicts, inventing planes that frequently blew up and, at one point, building a tank that was so melodramatically heavy that not only would it sink into the ground, but it was also unable to cross almost any bridge.

The fascists invested time devising, funding and then constructing to completion a fighting machine that was too heavy to go anywhere and actually fight, not to mention too slow to get itself either into or out of trouble.

Think about that for a moment. They continued to consider themselves superior. These fascists thought they were a type of extra special, extra clever human being. They really weren’t very good at self-reflection. They had begun to lose imagination, creativity and, increasingly, even common sense. It turned out that people excited by power and force weren’t able to sustain much together, to foster much beyond infighting, bullying and corruption.

I talk about absurdist performance art but it’s perhaps important to remember the fascists' own relationship to art. Like dissenting people and dissenting ideas, the fascists would throw out or reject or destroy great swathes of art that they decided was inferior, irrelevant or insulting. Before the war in Europe started, some of the fascists actually staged two concurrent art exhibitions, one of which showcased only their own, superior art, the other of which contained a variety of other art they had decided was “degenerate” and unworthy. They were attempting to make a statement, but it seems that the irony was lost on them when the attendance figures made their own statement, showing that far, far more people, their own people, had visited the degenerate art exhibition.

The fascists sometimes made buildings. Fascist architecture was, like fascists, not very subtle or inventive or original. It was all about conformity and repetition and re-using old ideas, but in simpler and less expressive formats.

Part of the problem of hating everything that is different is that you are also doomed to hate things that are new.

Isn’t that sad?

Being born in nineteen eighty, I grew up under the still receding silhouette of twentieth century fascism. Not only had it shaped my family tree, remapped my country and reshaped my continent, it also remained fresh in the minds of so many millions of people. Its consequences were marked in stone in every town and village around the country. It was depicted in every type of media I consumed, whether that was films or music or books or the simple comics I’d read as a child. Again and again, they all showed how the fascists had done such terrible things, often simply by telling us relatively unvarnished, even uncritical facts. The fascists would be near caricatures, almost unbelievable but for all the evidence and all the personal accounts and even the ongoing discoveries, decades later, of some new transgression or travesty.

It was pretty obvious how bad the fascists were and how much worse they made everything. For everyone. Still, evidence and personal accounts and education, to remind people about the fascists and help them learn for themselves what had happened and how, was sure to help everyone remain disgusted and dismayed by it all. You wouldn’t want it to happen again and, even more so, you wouldn’t want to find yourself somehow ignorant of or even involved in something fascist. That would be unthinkable. That receding silhouette of fascism may shrink, but the harsh lessons of it all were too valuable to lose, in much the same way it would be foolish to throw away any other progress gained from such collective human effort.

Yet now I wonder if that receding silhouette was only the shadow cast by a sundial, ready to return again and fall over anyone ignorant or hateful enough to entertain the same ideas, to build the same habits, to express the same love for projections of power and conformity and obedience, the same desire to force, manipulate and coerce. I wonder about those who express such disdain for, and turn away from, examples of empathy and intelligence and deduction and reasoning and data and research and patience and analysis and debate and discussion. I wonder about the superiority they feel. I wonder about their capacity for self-reflection.

Even before I was born, so much of the arc of my life had already been defined, already been set out, as a result of actions taken by fascists. I have a feeling my future will be, too. And like those of the world who stood against it so that people like me might live a better, safer life, I will find my place in the collective struggle.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Six Years - On PTSD and Choosing Life

Content warning: This essay very frankly discusses mental health, trauma, gaslighting and suicide. It also links to discussions of abuse and sexual assault.

If you are experiencing thoughts of suicide, know that you are not alone and help is available to you or anyone who might need it, such as the Samaritans, the Suicide Prevention Hotline, or this list of other crisis hotlines and this list of international support resources.

This was reposted from my Patreon.

There are blue skies today. The sun bounces off the mirrored windows of a skyscraper downtown. It cuts straight across my balcony and shines onto my wall. A few blocks away, the staff of my favourite café will share their latest gossip with me, as they always like to do, and maybe later tonight I will make good food and play games with friends until unwise times in the morning. Isn’t life full of wonderful things?

You can find them everywhere. And I certainly do. Sometimes I’ve found them in the intimate, up-close details of a famous oil painting, between the notes of a new song heard by chance, even in the rustling at the bottom of a dumpster, which becomes chittering and then fur and a tail and then direct eye contact with a tiny criminal whose only felony was hunger. I’ve found them amongst perfectly crafted sentences that capture thoughts and feelings and hold them forever on the page, in the silence of the impossibly wild mountain wilderness a thousand miles from home, in the first moments that I’ve taken someone’s hand and watched the gaudy lights of some forgettable venue play across the lines and the shapes of their face.

That’s so many wonderful things to live for. And I can get overdramatically passionate about the tiniest, silliest little details.

I’ve been trying to write this for a long time. I had three significant dreams during that period. In the most recent, I had moved into a dark and barren basement, with most of my possessions still in boxes. Some old friends from long ago came knocking. They pressed their faces against the small windows and tried to force the ageing door. “Where did you go?” they kept asking, their voices entering through every crack. “What happened?”

Six years ago this month I destroyed my suicide note. I burned it on a rainy August night and watched it curl into a tiny, helpless twisting of ashes and charred plastic that no longer had any power or purpose. The note was inside of a ziploc bag, a choice I’d made to ensure its integrity and survival against any of the several different plans I’d made to end my life, and this had melted into black strands of hair-like debris that reached up to nothing. One or two of my handwritten words remained half legible in this mess and tried to reach beyond the flames, to share their intent with the world, but they would never again mean anything to anyone.

I made videos of the burning and took a few pictures, a sort of ritual of recording, then I told a close friend what I’d just done, and then, for a very long time, I set the image as the wallpaper on my phone. It would be an ever-present reminder to me of my choice to stay alive. It was supposed to help me feel strong, though the truth is that I rarely did. It was the worst, most harrowing and most damaging period of my life and with help, honesty, insight, therapy, time and invaluable connection with others who have either seen the same things that I have or had comparable experiences, I managed to fumble and fight my way through it all. But I will never be the same. Six years is a long time and I am still profoundly affected by so much. I am still trying to understand things. I am still trying to figure myself out, to make sense of my identity, my situation, my experiences. To work out where I went and what happened. And I am still trying to move on.

These words are something about that ongoing experience, that work in progress, and about the dual significance of a span of six years. It is not so much about causes or causers, but instead about consequences and changes, and that’s for three reasons.

The first is because what happens after and as a result of trauma is so enduring and significant, perhaps even the most significant consideration of all, and it’s how we find ourselves discussing things like spans of six years or, for some people, far longer. I want to try to explain some of that sort of intensity and that sort of timescale.

The second is because it’s my hope that this is the most helpful way for me to talk about all this, the most illustrative to other people, the most constructive. I could have chosen many approaches, some which I believe might have been more harmful and destructive, and I don’t generally want to be a punitive or destructive person. Ultimately I think this is the most positive and productive approach.

The third is because I’m still not ready to unpack many things, as so much is still ongoing. I am not at the end of this, not out of the woods, and I think I need to know that I’ve reached the end of whatever journey I’m on before I can return to the start.

There is, allegedly, a power in choosing how your own story is told. So I’m choosing to tell it this way and, I hope, with the awareness that any exercise of power requires consideration and responsibility.

Six years is a long time, and while I’ve been trying to write and rewrite this thing for months, those months still pale in comparison to more than half a decade. A lot has changed in six years, and yet I also wish some things weren’t still the same, that I would have been able to make more progress, that I would have been able to create more distance.

Because, while I am six years from that burning note, from that summer rain, in my memory and my mind it doesn’t work like that. I still find myself beside that moment in time, like I could open the door to the next room and once again be right there.

---

Writing this has been very difficult. Writing is supposed to be one of the things that I am best at, and in the past words used to spill out of me so regularly that I wrote a tri-weekly diary, but I’ve had to come to terms with the fact that my relationship to writing has changed. It’s not just that this is a difficult topic. It’s that words don’t come as easily or as fluidly as they once did, making it much easier, all too appealing, to simply not push myself. To avoid things entirely.

But I wanted to write this, in part, because it would be another act of not giving up. I wanted to show myself what I could do, what I still can do, and that, even if I’m changed, I’m still stubborn enough to fumble and fight my way through.

---

I want you to imagine a house. It can be any kind of house, that part isn’t important. What is important is that the house is your home and you have lived there for a very, very long time. It is comfortable. It is safe. It is so intimately familiar that it is a part of your identity. Perhaps you grew up there, or you raised a family there, or you retired there. It doesn’t matter. What matters is that it’s your home and that everyone knows you live there.

Next, imagine that you have a terrible day. The worst day. And at the end of this terrible, terrible day, on a bleak and dusky evening, you expect at least to be able to come back to your house, your home. You take the same route back to the same address, where you see the same building stood before you and open the same front door, ready for the comfort of a place you’ve made your own.

You enter this space that you’ve known for so long and you notice something is wrong. The first clue is something small, perhaps a lamp missing from its usual spot, or you collide with furniture moved somewhere unexpected. You feel for a light switch that is now on a different wall. You stumble on the stairs as you make your way to a bed that is hard and unwelcoming. In the morning, the light from the window is not only a different shape, but cast in the opposite direction.

The changes stop being so subtle. After you notice that a carpet is suddenly faded and pale, you open a closet to find it is twice as deep. Some of your possessions are missing. The spare room no longer has a skylight. The kitchen is a different colour, with different appliances, with no back door, half the size it once was because the walls have been moved. There are new rooms whose arrival and contents are both equally inexplicable. Your most cozy corner is now cold and uncomfortable. You must relearn the entire layout, from bathroom to basement, because moving around the way you once would only causes you to stub your toes, to trip, even to fall.

Your friends don’t understand why you no longer enjoy going back to your house, your home. They don’t understand why you screamed at the different closet, why the sunlight on the wall makes you nervous. Being in your own home now hurts and scares you. How can you possibly relax here? But this is still your same house, at your same address, the one that everybody knows. You can’t argue that it isn’t. And if you invite a friend inside, after ranting about everything that is different, they ask “Why did you change all this? It’s so much worse.”

What can you even say in return? “I didn’t”? That shit’s insane.

But that is how it feels, like I live in a house that isn’t my home. Sometimes I don’t recognise myself. Sometimes, on the worst days, I don’t know who I am any more.

“Where did you go?” ask the voices, entering through every crack. “What happened?”

---

Last summer, a man came roaring down my street in his flawless luxury emerald convertible. I remember him well. He had dark sunglasses and a tan suit jacket and a hairstyle slick with oil, like he was being a parody of a rich man from an eighties film. He surged through the stop sign right in front of me and I let him know what I thought of his public display of privilege and indifference.

“Go a little faster, you cunt,” I yelled. “Maybe you can hit a kid.”

He swivelled his head, looked back over his shoulder and stared straight at me.

He also slowed down.

It was then that I realised the volume I must have used to project myself, over the noise of his engine and toward a driver already continuing down the street, meant a few of my neighbours had likely heard me too.

I’m not sure I cared.

I used to be a more modest and deferential person, and often that is still the case. But often it is not. I have less patience. I have less fear. And I have less trust.

The fear thing is great. Last autumn I walked across a narrow, quivering suspension bridge with no care for the drop below. Later, I found another far narrower, far smaller one and, all by myself, alone in the woods sixteen kilometres up a trail, I jumped up and down on the thing until it shook and swung.

I used to be terrified of heights.

My sense of fear isn’t gone. But it’s both so much more manageable and also, quite often, a thrill. It’s taken me a while to realise that I increasingly seek out things that are exciting, risky or extremely stimulating. I am frank with strangers. I am quick to make decisions. I am keen to try new things.

It doesn’t sound so bad, does it? That’s because it isn’t. Not all change is bad and not every consequence of my experience has been negative. Slowly, gradually, I am learning to appreciate a few of the changes, to lean into them. While one part of me feels sad that I’m less trusting than I used to be, another part of me sees this as more practical. I’m far quicker to drop something or someone like a rock the moment I sense things that I don’t like, and my sense for such things is certainly sharper than it used to be. Am I always right? I don’t know about that. Perhaps some people have been casualties of an overabundance of caution. Or paranoia.

That might just be the new cost of doing business.

---

It was some time in early 2020, while talking with my GP and taking some evaluations, that we began to look at my behaviour more closely. A year before, I’d talked extensively with a therapist about anxiety and about a growing sense of discomfort and distrust. I had far less patience, particularly for those who pushed boundaries, violated or were exploitative, often regardless of whether these things even involved or affected me. Anything that felt uncomfortably familiar, whether it was something I saw in a film, caught on the news or heard about on social media, could ruin my day. I would become jumpy, irritable, scared, or simply unable to do much beyond lie down and try everything I could to banish the feeling that my chest was being crushed. This might take hours. One evening, an ex found me curled up on the floor, ashamed of my own sadness. On another evening, a routine trip to see an exciting film turned into a sleepless night of panic and distress.

I began taking tests and found myself either dismissing the results or retaking them over and over in an attempt to get different answers. The outcomes kept telling me I had the symptoms of PTSD. This was far too dramatic a result and there had already been enough drama in my life already. I myself was too much drama.

Anyway, I thought, having the symptoms isn’t the same as having.

Sometimes I think about how, during some of my most difficult moments, the toughest weeks and months that I didn’t really know how I was going to get through, I made a lot of haphazard decisions motivated by panic and fear and ignorance, by doing my best to improvise and cope and adapt. Some things worked out. Some things did not. Probably the deciding factor there was luck and I’m not really sure I can look back with any wisdom or insight.

I didn’t always know what to do, what to say, who to trust, or how much to trust, how to respond to new information and changing situations, or what in holy hell might ever work out. My response to all of this was to keep secrets or to be cagey, to avoid places and people, to suddenly and liberally cut others off through a mix of ghosting, avoidance and outright blocking, or to occasionally have three-day long anxiety spikes in which I remained highly activated, oversensitive and endlessly insecure. During one of these, someone teasingly pushed me to take part in something that I didn’t want to, something that wasn’t even a big deal, and I was so close to breaking down that I had to almost run from my friends and find a quiet place to catch my breath, all the emotions in my body somehow pinched into a single point somewhere in my gut. During another, a laptop accidentally nudged half an inch sent me into panic mode, manifesting a feeling like a blade of ice slicing straight through my pulmonary artery.

These sorts of responses and behaviours would happen even in spite of all the various combinations of therapy and medication and support I was cycling my way through. I don’t feel proud of how I handled many of these things. I would love to be able to say that I handle them so much better now, with the aid of wisdom and insight. Perhaps sometimes I do.

Sometimes I have simply made terrible decisions and, looking back, I am still not sure how I might have ever done any different. I am lucky that the vast, vast majority of those decisions didn’t fuck things up further.

---

It’s a magnificent day as I write this. The world is jade and azure and gold. The sky is exquisitely, flawlessly blue. Every leaf is rich with the gloss of summer. The sun is setting into the sparkling sea beside a succession of fading distant mountain ridges, each hazier than the last, the furthest so indistinct it looks almost like mist, a ghost of an idea two thousand metres tall. Container ships the size of city blocks sleep in the bay, their hulls traced and wrinkled with rust from a lifetime of global migration. As the growing shadows of slowly swaying trees reach their way toward me, the last light of the day glides over the ground, over the grass and even over my body itself, like spilled wine gushing from a glass. It colours everything the sweet shade of nostalgia. The air is gently warm and the grass is soft beneath me.

I love days like this. They are one of the reasons why I moved here, why I put so much time and effort and energy into relocating halfway around the world. Into building the life that I wanted, piece by piece.

And I love so many of those pieces. I love my little apartment, with the balcony that I always wanted, with its ragtag assortment of secondhand furniture collected one item at a time, with its shelves tucked in here or squeezed in there, never quite tidy enough to look presentable. I love my walkable neighbourhood, with its shops and cafés and cats that follow me from block to block, or critters that peer out from between bushes in the rustling dusk. I love how low cloud creeps in to cover the tips of the skyscrapers downtown, or how the jagged outline of mountains shape the horizon in almost every direction. I love trying to make things, especially with other people, and the reward of being creative, of being silly or being funny. I love all the things I’ve learned to cook, or the ways I can warm myself up on a cold day, or the late nights I can so often indulge, with no care for what might come tomorrow.

I have so much to be grateful for and so much to be proud of. So much here. So much now.

Pretty soon, the sunset will transform the whole sky into a gradient of colour. Someone somewhere will be playing guitar on the beach, and maybe they’ll be good. Stars will appear in the sky, above the familiar urban zodiac traced out by the city lights of apartment buildings. If I stay up late again, the dawn sky will turn the royal blue of an emperor’s cloak. And then all of this will happen again.

I have so much to be grateful for. So much to appreciate.

---

A few weeks ago I had my first nightmare in some time. They still happen. The specifics matter less than the broad themes. Deception. Gaslighting. Manipulation. Boundary violation. All of it in plain sight, yet still unseen, making me feel like I’m helpless, like I’m crazy, like I have no hope of ever being believed.

I thought about it all day. The situations, the faces and the fears. This is the way it’s always been and once one of these nightmares visits you, it stays for a while. It’s like a small stain, an odour that gets into your clothes, the stink of cigarettes after a party the evening before.

Can you wash out a stain? Sometimes. With the right substances, with the correct regimen. And with some aggressive, persistent scrubbing.

One summer night years ago an ex woke me up because I had been thrashing about in my sleep. I had worried her by rolling around and muttering like a madman. Was I having a nightmare, she asked, and it wasn’t just that I was, but that I had them all the time. Every week, at least, each leaving that same gross feeling of violation and abuse. The anxiety medication that I had been prescribed was helping me sleep more, but it also seemed to make my dreams more vivid and profound. It was either that or barely being able to sleep at all, woken by the slightest of noises, up before the crack of dawn because some unresolved tension in my body overpowered all tiredness and fatigue. Even with medication, the smallest of things could still turn me into a nervous wreck, and one night I cried cross-legged on my bed as I explained to my ex not just that I had interpreted a few of her utterly inconsequential actions as a sign she wanted to leave me, but also that I might always be like this. Forever.

The nightmares began a few months after I burned my note. It was right after I opened up to another friend about what was going on in my life, and their response was to tell me about something else that had happened, the full story of an event from another six years before, from distant 2012.

It’s not my tale to tell, but six years is a long time to not know the full story of something. A long time to be deceived, to find out you’ve been lied to by someone you trust and that your ignorance has affected many decisions that you’ve made. Again, I am lucky that the vast, vast majority of those decisions didn’t fuck things up further. But some did.

Six years. It hit me then how long it can take for people to feel able to talk about something, as well as continue to be affected by it. How far the ripples travel and who they touch. And now, here I am, with my own six years.

That discovery was one of several experiences that transformed me into that person having three-day long anxiety spikes, remaining highly activated, oversensitive and endlessly insecure. That person thrashing about in his sleep. That person yelling “You cunt,” down his street.

---

I’ve written before about my physical health and my relationship to my body. I was anxious about things being wrong with it long before I had thorough examinations and validating diagnoses, but as part of those treatments I wrote about, a trio of doctors warned me about how stress was worsening every condition and symptom I experienced. Stress was ruining my health. I was having so many migraines that my GP sent me for an MRI that revealed how those migraines were changing the white matter in my brain.

I would have to do something about this.

Those doctors would help me do something about this, as would other professionals, and their help was invaluable. This would be impossible to tackle alone.

Sometimes I think about people I’ve heard say such things as “It’s not your responsibility to fix someone else,” and, while I don’t disagree, doesn’t such a phrase also imply it’s surely somebody’s responsibility, in this society that we all share, built from things that help us support one another?

Otherwise we’d be suggesting that people fix themselves.

Sometimes I think about people I’ve heard tell others, or themselves, or sometimes the world via the spontaneous and sneeze-like broadcasts of social media “It’s on you to fix your shit,” and I wonder if that’s where that sentence should terminate, if that’s exactly how it should be phrased, if those are really the words that everyone, or anyone, needs to hear.

Because sometimes I also think of another clumsy analogy I once put together. It’s a scenario in which I describe a pedestrian struck by a car, perhaps one driven by a rich cunt with dark sunglasses and a tan suit jacket, perhaps even one that has mounted the curb or surged into a crossing. The pedestrian is knocked down, maybe immobile from the pain and injury that comes from a broken pelvis or fractured leg. An ambulance is summoned, a customised vehicle equipped to transport them to a hospital. In that hospital, that specialised medical facility, a team of trained experts will use skills and equipment to triage and manage, to analyse the pedestrian’s injuries, to provide relief and to chart a course toward recovery. There will be x-rays, there will be drugs, there may well be physiotherapy. I doubt at any point that the person lying in the street would be told, by someone coming upon the scene, “It’s on you to fix your shit.”

No. Not any more than they’d be expected to walk to the hospital, to interpret their x-rays or to prescribe their own medication. Indeed, if they attempted any of these things themselves I wouldn’t be surprised if someone along the way communicated to them some more polite version of “What the holy fucking fuck do you think you’re doing?” and “You’re in no state to do this yourself, let alone know what you need,” and “Fucking hell. You’re at your most vulnerable right now. Fuuuck.”

Hopefully.

Once, many years ago, I knew someone who broke their pelvis. It takes months to recover, maybe a year or more for a limp to fully disappear. And it requires all kinds of help and oversight. It worked out. Doctors and medical professionals can be remarkable.

I have read a lot of books and papers over the last six years. I have listened to a lot of podcasts and interviews. I have been recommended a lot of material by therapists, by friends, by fellow PTSD sufferers. One well-known trauma expert I was pointed toward is Canadian psychologist Dr. Gabor Maté. And he says this:

”Everybody is born needing help.”

He means that it’s a fundamental element of the human experience.

---

Sometimes I go running and sometimes I go to the gym. The reasons I do this are complex, ranging from wanting to be healthier, to wanting to feel better about my body and how it behaves, to feeling like I am making progress with something. That last one is particularly important, because I’m doing something where I’m objectively able to recognise change.

When I run, an app tells me how far I ran and how long it took. I can’t disagree with the app, because it’s entirely objective, and so when I have a bad day, feel terrible and wonder what the point of anything is, the app still shows me that I achieved a reasonable or even an improved time.

It wasn’t always like this. I was bad at these things. I run better than I used to. I perform better at the gym than I used to. I have the metrics to prove it, and while I’m not a particularly dedicated or regular person with my exercise, I still keep at it and I still see improvements.

Whatever it is I’m doing, these apps and their statistics all offer me the same, very simple analysis:

“You’re doing better.”

I motivate myself to run, to go to the gym, to go on twenty-five kilometre hikes over difficult terrain, but I don’t do these things without some kind of help that comes from either expert resources, advice or training.

I don’t exist in a vacuum. None of us do.

---

Help is important because it offers things like perspective and expertise and informed advice. And don’t all of those things sound so extremely important?

How about we imagine that our immobilised pedestrian wasn’t collected by an ambulance. Let’s imagine instead that the driver of the car that hit them stepped out of their vehicle, shook their head, put their hands on their hips and said “Look what you’ve done.”

And then “It’s okay, I know what’s best for you,” before carrying the inert person into their car and driving away. Perhaps even unseen. No witnesses.

If such a thing happened, in this society that we all share, with that person at their most vulnerable, who is responsible then? Who is responsible for what happens next? Who is responsible when that pedestrian, forever limping, says things like “It was my fault, I shouldn’t have been walking there,” or “I should have been looking out,” or “I should have been more visible,” and so on?

A lot of accidents and injuries and collisions and whatnot can be traumatic, scary, confusing. “How do I make sense of this?” asks that person, whether carried away alone in a car, or surrounded by doctors in the emergency room, or anywhere else they may happen to find themselves. “How do I deal with this?” And who might be around them at that moment to help answer such things?

And what will they say?

Perhaps you know someone who was, metaphorically, struck by such a car, before being then carried away by a driver with all sorts of ideas about what’s best, and who later blamed themselves for everything that happened. I don’t know.

I do know how important it was to receive the right help from the right people.

---

It’s hard to know exactly what to do. You may respond to your trauma with a desire for revenge, retribution or restoration. You may not have the insight or the time or the means to do anything much at all. There is the ideal of what could or should happen when harm has been caused, but there is also the uncomfortable reality of how such things actually play out, of how long justice can take, of who is granted credibility, of how complex social dynamics can quickly become, of how awkwardly and uncomfortably people can react when they discover something they would rather not have, or that they have been misled, or so much more. We’ve all seen such things play out secondhand and firsthand.

I have had six years to consider the most helpful way to respond, the most constructive, the most positive and productive. I am still considering. I don’t have much in the way of answers or advice there.

Sometimes I think about the anonymous Broken Teapot essay, with all it has to say about the complexity of dealing with abuse dynamics, of harm happening within a group or community, about social consequences. It was written over a decade ago now, but it remains a very relevant piece of writing that brings up all sorts of considerations around responsibility, about trying to come to terms with trauma and abuse, and about how people might try to use systems or processes to try to solve things in unhelpful ways or even for their own ends.

People can have a lot of opinions about how to handle trauma, how to respond to abuse and how to leap into some sort of process of justice or accountability or reparation or even plain old revenge. So many opinions.

It’s exhausting.

Back in 2020 I tried to write something about all these complications and considerations that I was going to title The Calculus of Abuse. Like much else, it rots in my drafts folder.

Sometimes I think about how many of the ways that we push people to address both their trauma and the things or people that have caused their trauma only makes things worse. I am sceptical about the practicality, value and effectiveness of processes of justice, reparation and accountability. I think a lot of people believe that they will fix things, that they will be fair, that they will spotlight situations and systems and people that cause harm. That, in this cold and unflinching exposure, justice will be done and books will be closed on long and difficult stories.

And I think that’s because we see this happen now and then. Sometimes it happens very publicly. It seems to at least occasionally all work out.

Sometimes I think about friends who were excluded from social circles because they spoke up about something creepy or problematic, because it mattered less what actions or behaviour someone had demonstrated, even what could be proven, and much more who was more popular, or that the status quo be maintained, or that applecarts not be upset. I think about how different people share or don’t share their traumas and their experiences, what they include and what they leave out. I think about people who weren’t believed, people who were misrepresented, people who were shut down. I think about people who spent so long trying to get a handle on their trauma that any thing or person they might want to stand up to already had so much time to prepare, to seed the ground, to dig in, to get a head start. And I even think about the capacity people have to improve, to feel regret, to move forward as better humans. It’s a potential that I hope exists in us all and the writer Kai Cheng Thom seems to agree, saying that even those who cause harm themselves need help to “exit harmful behaviour patterns.”

Sometimes I think about what a friend of mine said about abusive people just being "regular people with very limited tools." And that’s not so different from a child. Doesn’t that make you feel sad?

I think about all of these things because how could you not? How could you not worry about how taking action to address a terrible thing would, in fact, only make that terrible thing even worse?

There is a paper by the American psychiatrist Judith Lewis Herman called Justice From the Victim’s Perspective that touches on how many processes and pushes toward addressing abuse and trauma can be retraumatising, without any guarantee they will lead to a meaningful outcome or significant change. It touches on how legal processes and systems can be manipulated to further harm and harass those seeking redress, or how disparities of power and status and money can immediately put the damaged and disadvantaged people who try this on the back foot. It touches on difficulties presented by such things as burden of proof, especially combined with the challenge of a memory minced by traumatic events. How does someone demonstrate and prove trauma, or gaslighting, or manipulation, or anything else?

It also talks about how not everybody seeks such things as justice, restitution, revenge, or not always in the ways that we think, and for a multitude of reasons. These can vary from worrying they won’t be believed or that the process will serve them, to wanting to move on, to the idea that it may be pointless, as some “offenders are empathetically disabled… not capable of a meaningful apology, so they can never provide anything to victims that would be useful.”

Both this and the Broken Teapot essay also feature people examining how they themselves have handled abuse and trauma. I think this is probably the most difficult part of many years of therapy, reading and reflection. Sure, it sucks to have been harmed by an event, a situation, a person or a system, but at some point you also start asking yourself difficult questions like “How do I avoid something like this again?” and “Did I do anything that made this worse?” and “Was I codependent, did I enable someone or did I perpetuate something with my reactions or my responses?”

“Abuse dynamics aren’t so simple,” says the Broken Teapot essay, at one small but very important moment, not long after “I was not solely ‘a victim’. Is anyone?” And, after all those years of therapy, reading and reflection, I’ve come to believe that abusive people and systems gain at least some of their power from how you interact with and respond to them. If we were, all of us, perhaps better informed, we might understand, avoid or escape so many difficult things so much sooner.

And while both the Broken Teapot essay and Justice From the Victim’s Perspective talk a lot about sexual assault, their considerations and their examinations of consequence are more broadly applicable. This reflects how I find myself relating to so many stories of trauma and abuse, regardless of what the specifics of any incidents might be. It’s because I recognise the same things in the subsequent developments, reactions and outcomes, much like I might recognise the same chord pattern in different songs. I see people trying to understand their own changing behaviours, trying to articulate why they won’t do a particular thing or go to a particular place any more, trying to both explain and understand how their body or their health has been affected. The specifics don’t need to be the same for so many of the consequences to be. And I recognise and am much more attuned to recognising those consequences.

Both these pieces of writing are also very good at illustrating one of the most important things that you can learn about trauma, and that is, whatever happens or whatever choices you make, things can never be put back in the box.

Trauma is never erased.

---

Here’s what I think is another of the most important things we can learn about trauma, which is that people are generally very bad at dealing with it and are even worse at dealing with it if they are unsupported. And even if they have all the support in the world, they are probably still going to make bad choices, self-sabotage, lose perspective and do things they regret.

They will probably be foolish, be confused and be likely to make choices that could hurt other people. They may not have great insight or work against their own best interests. That doesn’t mean that they get a free pass. It doesn’t mean we are obliged to simply accept these behaviours. But I think these are realistic expectations that we should have.

In his pioneering book The Body Keeps the Score, the psychiatrist Bessel van der Kolk writes that many trauma responses are “irrational and largely outside people's control,” coming from people who are “rarely in touch with the origins of their alienation.” An awful lot of the book is about helping such people to find ways past this, rather than disregarding them or pushing them away, even though this will be difficult. I don’t remember anything in the book that comes close to “It’s on you to fix your shit.”

---

While one part of me wishes many things had not happened, feeling both weaker and sadder, another part of me acknowledges that I have gained new skills and strengths. And one of the best things about what I’ve gained is that all this doesn’t just help me, but can also be applied to help others.

That’s a good thing.

I’m a tiny bit wiser than I used to be. A lot of reading and talking to experts and digesting all sorts of media leaves its mark. It’s not just that I know a little more about myself and my experiences, it’s that I can now better recognise parallels to those experiences in other people’s situations, behaviours and pasts. I anticipate slightly better, seeing problems further ahead, and I have a stronger sense of what I need to drop or to avoid.

I’m doing better.

---

I don’t have much that I can write here in terms of the specifics of therapy. I would describe a lot of the process of unpacking and analysing the causes of my PTSD as being extremely painful, like trying to both tidy up and then reassemble broken glass with your bare hands. The things that brought about your PTSD are shameful and harrowing. Their analysis can also be, through a process that can variously be sad, scary, frustrating, educational, validating and empowering. It takes a long time and requires expert assistance, which means the help you need can be a somewhat scarce resource and very, very expensive.

You pay for your trauma for a very long time.

---

I discovered one of the most beautiful sounds in the world some time after 2016, some unknown amount of time after I moved into this apartment of mine, with its balcony and its skyscraper views. I don’t remember now when I first heard it, but it’s been years now and I still adore it whenever it happens. It’s small and subtle and can happen at almost any time of night or day. It’s a sound that makes me think of safety and independence, of making my own space and then occupying it. Of security and stability.

I really, really appreciate security and stability. Much as I increasingly seek out change and crave new experiences or opportunities, these things feel so much better if I can enjoy them with the understanding that I have some sort of foundation under me. Something solid. No matter how small or how far away. Some place of safety.

The sound happens when it’s raining. Whatever metal it is that rings my balcony is hollow, so that when rainfall strikes it, it responds with a kind of subtle but sonorous singing. This ringing isn’t the specific sound I’m talking about, though. That sound is slightly different, something that rises above this other background arrangement.

When a particularly large drop of water hits my balcony railing, it gives a flat, gentle ping of appreciation. The background patter of the other raindrops will continue and then, again, after some irregular interval, presumably as water has collected from the balcony above into a particularly large drop, the ping will sound again.

I heard it one morning this spring, months ago now, right after I woke up and not long after I had started writing all this. I lay there in bed on a day the colour of slate and cigarette smoke and I thought about how the world is made up of so many beautiful, tiny things. Ping, goes one of them, and maybe nobody else on the planet notices or cares. But I try to remind myself of this and how my life is full of so many other probably stupid little things that I like, that I love. Don’t lose these things, I try to tell myself. Don’t forget about them and don’t forget to notice them when they happen. You gave yourself so many more of them when you chose to stay alive.

You get a lot of time to think on days the colour of slate and cigarette smoke.

---

You’ll notice I say “sometimes I think about” a lot here, when reflecting on less positive things, and you might consider this a writing device or a cheap hook or some other writer’s cheat. It partly is, but it’s also a truth. I do think about these things, and so many other things, very often. I think about one or another of them almost all of the time. I find it very hard not to think, to turn my brain off, and the unfortunate truth is that it reminds me about things to do with my trauma almost every day. It has done so for six years now and, as we’ve already established, six years is a long time.

Evenings can be the most difficult time. While I’ve always had a flippant attitude toward sleep schedules, I never used to have trouble going to bed. Some nights my brain will never switch off. My memory is overflowing. It doesn’t matter if I’m tired, it makes no difference if I’m exhausted. The rules around sleep are different now and I think I’m still trying to relearn them.

One therapist described the traumatised mind as like an overflowing wastepaper basket full of difficult memories that are constantly falling out. Any new addition can cause one or many of them to spill and scatter. Time and therapy can help to more properly sort them and make space for other, new things.

What a good analogy.

Occasionally, there might be a suggestion of ADHD sent my way. I can understand why things would look that way and a lot has been said by people more experienced than I about how ADHD and PTSD can seem similar. I think if ADHD had ever been the case some mental health professional or other member of the medical community that I’ve dealt with would have spotted this by now. But no. I’m distracted by some memory or flashback. I’m avoidant, or I’m in need of some thrill or stimulation. I might be full of nervous energy or unusually, intensely focused on something because it feels so good to be thinking about something I enjoy.

And sometimes things are bounding out of that wastepaper basket like clowns out of a clown car. I can feel like I've lost a lot of control over my mind and it's all I can do to rein it in. Some days I have coping strategies and some days I'm sick of it and wish I didn't need to have to cope.

And so I keep myself busy with the stimulation and the novelty that I crave. With people. With events. With runs, with the gym and with twenty-five kilometre hikes. Whatever it takes, whenever I can. It’s not ideal. I’m still figuring out what I need. I don’t always get the balance right. Sometimes unexpected things make me very emotional, either very sad or very frustrated, and I rarely know in advance what might do that. Sometimes I sleep less than four hours a night. Sometimes I want to be alone. Sometimes I desperately need company. I probably seem very strange.

But, let’s not forget, in the past I would lose whole days. For hours, my chest would feel like it was being crushed. I might be found curled up on the floor, ashamed of my own sadness. The nightmares would come every week. So things have clearly, obviously, demonstrably improved.

I’m doing better.

---

I still suck at writing. I don’t know how to fix that yet. I still very regularly feel like there is a gulf between me and so many other people, even my friends. I still have outsize reactions to irrelevant, immaterial things. I still lack confidence in my own personal calibration. "Many traumatised people find themselves chronically out of sync with the people around them,” writes Bessel van der Kolk. Yeah.

Toward the end of its six season existence there is an episode of BoJack Horseman where an actor reacts angrily to some improvisation and unexpected physical contact that happens during filming. Her colleagues are confused as to why she does this, and perhaps she doesn’t understand herself, but we the audience know that this a response to a physical assault by the titular character some time before. She never finds out, but this leads to her missing out on perhaps the biggest opportunity of her life, after a director discreetly describes her as erratic.

There is no further development with this plotline, no resolution to be had. Nobody finds out why she is like this, nor wants to, nor sets things on a new, better course. I try to remind myself that this sort of thing can be happening all the time, to try and grant people some grace and compassion, but also I try to remind myself that this is me. I have my versions of this behaviour. Maybe fewer than I used to, but still. I can be erratic and I have to face the consequences of that, as well as minimise it as much as I can.

I recently stopped buying fresh fruit from my local store because they would repeatedly put mouldy, furry produce on display. The last time I discovered this, I was holding up a box of ostensibly shiny, blood-red strawberries to once again discover the mass of fuzz hidden underneath. Food is expensive enough as it is, I thought, and it doesn’t also need to be garbage. Too late, the look on the face of the customer standing next to me clued me in to how vocal I’d been with my three-word expression of disgust and displeasure.

“Jesus fucking Christ.”

---

You’ve read a little about my first dream, about old friends. You’ve read a little about my second dream, the nightmare. Here comes my third, from earlier this summer.

I dreamt that I was trying to get home again. I was confused about where I was, trying to remember a route through unfamiliar Vancouver alleys. It was evening, not yet dark, but the time between when you lose the long shadows cast by the last of the sunlight and begin to wear the rich, jewelled canvas of the stars. None of the people I stopped and spoke to knew the streets I named. None of the alleyways I walked down took me in familiar directions.

I never found my way home, but I never stopped trying. Perhaps this does indeed mean I haven’t reached the end of whatever journey I’m on, that I can’t yet return to the start. I think it’s both practical and pragmatic for me to accept that the next six years might still present me with many challenges. That I will have bad, directionless days. That sometimes I’m going to fuck up and fall short.

I woke up to another bright, warm summer’s day, far later than I meant to, and I made myself a fine cup of coffee and a rich breakfast that I would be foolish not to enjoy.

Sometimes I think about suicide. Those thoughts haven’t left me yet and I’m not sure they ever will. Sometimes they arrive strong and loud and insistent, from out of nowhere and with all the power of a thunderbolt in a storm. Sometimes I want to be a shining example of how to conquer PTSD and sometimes I'm so sad I can’t get out of bed and sometimes I am just pissed off and angry. Each day is still different. But tomorrow I will wake up and perhaps I will think to myself “There are blue skies today,” or perhaps I will hear ping, or perhaps I won’t need anything at all to feel great. And perhaps there will be some undeniable sign in the day’s events, in my behaviour, even in the world around me, that demonstrates to me how much I’ve improved.

Each day is still different and today the glib part of my personality says “I sure hope you’ve improved, it’s been six years! That’s six years of painful PTSD examination, therapy, medication, reading, research, specialist appointments, many thousands of dollars spent and a god damn MRI of your weird and messed up brain.” And am I being disrespectfully flippant of my own experiences when I add that having an MRI of my brain was, at least, kind of cool?

Because another part of my personality wants to remind me I’m wiser, braver and maybe even a little more able to help others, people who I will remind myself can’t be expected to fix their own shit alone. People who shouldn’t be pushed aside, in this society that we all share.

And I don’t regret calling that cunt a cunt.

It’s been six years and each day is still different and this morning, when I pause to ask myself how I’m doing, I find I have the most simple of answers.

It’s three words.

“I’m doing better.”

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ascent, Part 1

The first of two parts. Written May 2024, from an idea initially sketched out around 2021.

The ground was the colour of slate and smoke, a gradient of greys marbled like the surface of some faux kitchen counter, but it wasn’t snow that veined all those cracks and crevices, spreading like capillaries under skin. It was ice. There was no snow anywhere here on the ground, not at base camp, not on the lower slope, not even on the winding, meandering roads that brought visitors here, almost five thousand metres above sea level and so very far from the last of the tenacious mountain villages that marked the route. There was snow everywhere across the horizon, snow decorating every peak, but right here the nearest bank was seven hundred metres further up the mountain, gradually shrouding the great stone god that rose up to the west, piercing the sky like the poorly-hewn tip of an iron-age spear.

Taken from my Patreon, where you can read all this for free.

1 note

·

View note

Text

On Relaxing

Taken from my Patreon.

Sometimes I’m getting fitter. To help me in this ongoing endeavour I have a hugely supportive personal trainer who I usually see about once a week, and who very patiently guides me through various fumbling attempts to pick up progressively heavier objects while I wobble like a weathervane atop an old church. At the same time, we talk about lots of things, because she’s a great conversationalist and because there’s almost always something interesting that we want to exchange ideas about (I also think she might secretly enjoy making people try to form words while they struggle with all their hoisting and hauling, but who knows). During one of our recent sessions she asked me both what I would like to be doing next and how my current rest period was going. That’s when I shamelessly stole the idea of The Bingo Card.

First, a little context: I’m not really working right now. I don’t want to be and I don’t need to be and I’m lucky enough that I can afford to take a lot of time off. It’s been fantastic, but also a little alien. This is a position I have never, ever been in before. I’ve certainly spent stretches of time not working, but these have been more likely to involve me worrying how I’ll pay the bills, combing through employment listings or making another futile trip to what in Britain was hilariously known as the Job Centre (and has since been rebranded, for utterly unknowable reasons, as Jobcentre Plus, perhaps reflecting how it is now even more potent in its ability to be both punitive and pointless). That means I don’t associate not working with concepts like relaxation or security. Instead, a better way of describing things would be to tell you what I associate the concept of working with. Chiefly, success and survival. And, in particular, survival.

Staying afloat.

By the beginning of December I’d wound up all the game writing that I needed to do and had already set off on the first part of a long, relatively complex rail trip down the west coast of the United States. I busied myself by booking multiple things across a four leg journey in three states. I arranged to meet lots of people. I went to a work-related event. I had museums to visit and sights to see. I was endlessly stimulated, delighted and inspired.

It was all extremely good. It also probably wasn’t what you’d call relaxing. Or a rest.

As the year wound up and January chilled its way across the calendar I booked every appointment I might have neglected or delayed during the previous year. I saw my dentist and my doctor and my therapist and made sure to go to the gym more often. I snatched up furniture that I’d procrastinated buying for so long. I resolved to create all kinds of new routines for myself based around fitness and completing personal projects. I was Getting Organised and I certainly had all the free time to devote to this. I did indeed get a lot of things done.

It probably doesn’t sound like what you’d call relaxing. Or a rest.

And as my personal trainer and I talked about the year gone and the year to come, she told me about an idea shared amongst some friends of creating a sort of bingo card of goals, tasks and ambitions. Not so much a to-do list, but a grid of things to tackle, perhaps with a reward waiting when some are ticked off. Perfect, I thought. Great. Another way to organise myself, to motivate myself. The card could be categorised, I said. Rows are types of task, while columns are a ranking of how challenging they are. The rightmost task in the writing row is the most difficult. The leftmost apartment-related task is something I could do in a day.

I built The Bingo Card a couple of days later, collating a few different to-do lists that I had lying around (because I always do). I sorted and ranked it. It was a very effective act of organisation, satisfying, but it probably doesn’t sound like what you’d call relaxing. Or a rest.

A little while ago I talked to one of my closest friends and they told me how, now that they’re finally enjoying a period of downtime after a couple of stressful years, their body is tense and confused. They feel both strangely anxious and sometimes depressed, like there is some sense of urgency coming from somewhere, even manifesting from thin air, and at times this is exhausting.

I hadn’t yet said anything about what was going on with me.

Some of my old anxiety symptoms have returned. It’s not a big deal and it’s nothing I can’t deal with, but it’s confusing in light of there being nothing I need to be anxious about. Still, there’s that shortness of breath or that pressure on my chest, or those occasional strong reactions to the silliest or most mild of things. At times this is exhausting and some days I don’t seem to have the energy that carried me through all the work I managed last year.

Another friend sent me information about a potential job while I was drafting all this, which came about two weeks after yet another friend sent me information about another potential job. I have six listings open in my browser. I feel like I should apply to something, perhaps to all of them, even though that doesn’t sound like what you’d call relaxing. Or a rest.

My mind writes at night. As I climb into bed and pull up the covers and turn out the light, it offers me all sorts of ideas about what I can do next. It creates characters and concepts and forms complete sentences that quickly grow into entire paragraphs, somehow already fully formed. It remembers things I haven’t finished and suggests new projects I could begin. It can be exciting, inspiring, but it probably doesn’t sound like what you’d call relaxing.

Or a rest.

I know all of this is ridiculous, because at the same time I’m so happy. I have freedom, I have the ability to indulge in so much more and I’m enjoying things I haven’t had time for in months. I feel very good about myself and the choices I’ve made, as well as acutely aware of how fortunate I am. But things happen when you have time and money to burn, and one of those things is the rise of a nagging guilt about how you could just not burn those things and instead apply yourself to something much more practical or productive. You could even sit down and write something to help you dissect and deconstruct all the experiences and the feelings you find you’ve been having.

All of this is far from the worst problem a person can face. I’ve certainly had to wrestle with things infinitely more difficult, but it’s a reminder that a change in circumstances doesn’t mean an immediate change in outlook, in attitude. I am trying to alter the way that my mind operates and, at some point, my body will also decide to make some alterations too. I have no timeframe for exactly when that may happen. In the meantime, I will try to get on with as little as possible and, armed with the knowledge that I'm not about to sink if take a break from paddling, I may almost be on the verge of relaxing.

0 notes

Text

youtube

https://www.patreon.com/paullicino Whoops! I've been sharing things on Patreon for over five years now and I missed this huge anniversary. Here are some reflections on that, thoughts about the future and an encouragement for you to, first of all, support minority and underrepresented creators before you continue to give money to someone like me! A huge thank you to everyone who has supported me over the years. You've made such a difference!

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Questions from a Worker Who Reads

by Bertolt Brecht

Who built Thebes of the 7 gates? In the books you will read the names of kings. Did the kings haul up the lumps of rock?

And Babylon, many times demolished, Who raised it up so many times?

In what houses of gold glittering Lima did its builders live? Where, the evening that the Great Wall of China was finished, did the masons go?

Great Rome is full of triumphal arches. Who erected them?

Over whom did the Caesars triumph? Had Byzantium, much praised in song, only palaces for its inhabitants?

Even in fabled Atlantis, the night that the ocean engulfed it, The drowning still cried out for their slaves.

The young Alexander conquered India. Was he alone?

Caesar defeated the Gauls. Did he not even have a cook with him?

Philip of Spain wept when his armada went down. Was he the only one to weep?

Frederick the 2nd won the 7 Years War. Who else won it?

Every page a victory. Who cooked the feast for the victors?

Every 10 years a great man. Who paid the bill?

So many reports. So many questions.

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

On Poverty and Comfort

Taken from, and funded by, my Patreon. Please check it out.

It’s happening again.

I just got forced back a place in line, mere seconds from being served. Another patron, presumptive and impatient, slid between me and the server working the till in a move that I would describe as all too practised, as smooth, to ask what soup flavours were available. This patron, surfacing from nowhere like a submarine, came up on my starboard side. She cut in, pitched her question across the counter, then cast a glance my way and, to use a phrase my mother would, “looked at me like I was shit on her shoe.”

While I’m not exactly shuffling about in my tracksuit bottoms today, there’s nothing special about what I’ve chosen to wear. I should perhaps have picked The Other Coat, which has magically caused several strangers here to strike up conversations with me. In particular, I feel it’s no small deal for a young woman to decide to start talking to a man she doesn’t know, but one day I was suddenly being told that I am classy and refined, being English and so smartly dressed. Perhaps on a different day I might have felt flattered, but I felt more like some sort of fraud was being committed. I was wearing class camouflage.

It’s something I try to do here, in my local fancy café, because otherwise I feel uncomfortable. But I realise that it’s also something I’ve unconsciously done for so much of my life.

I’ve got a few things that I want to write about here today, everything from sandwiches to suits to submarines, but before I go on I have to ask: Do you know that phrase “like I was shit on her shoe”? Do people say that where you’re from? Some of my lexicon is loaned from Chiswick and Southall, passed down from people who worked as labourers and long-suffering housewives, from bricklayers or from the lower decks of the Royal Navy, from homes that had no hot water and outside toilets. It’s the sort of language muttered past cigarettes on brick stairwells, or yelled across loading docks embellished with incoherent graffiti.

Sometimes these things slip out of me and no-one has any idea what I’m talking about. I make a right pig’s ear of it. And in those moments I’m suddenly somewhere else. I’m in a different time, a different place. And a different income bracket.

Or perhaps the different income bracket is where I am now. So in which do I really belong? Tell me, which would you associate me with? Graffiti and slang? Or poise and politeness?

It’s a question we can return to, if you want, because this piece of writing is in part about returning to things. When I began drafting it, months ago now, I didn’t realise just how much it echoed something I had written nine years before. I was already trying to articulate trends and patterns, without realising I had fallen into one myself.

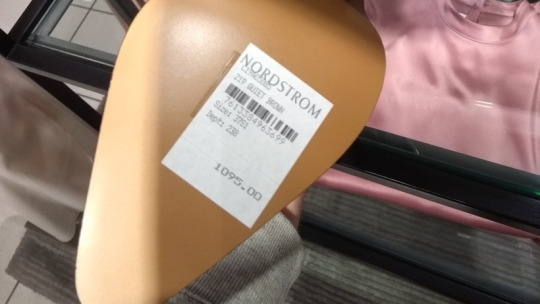

For now, I have a different question. Did you know that one of Vancouver’s most infamous shortcuts has just closed? The three story, two hundred and twenty thousand square foot Nordstrom store that sits right between the city’s central plaza and two of its busiest stations is no more. Vancouverites will no longer be able to use it to pass diagonally through a whole block, as the crow flies, weaving dreamily amongst racks of designer handbags and thousand dollar flip-flops, before finally returning from this fantasy realm like Dante stumbling out from the underworld.

It’s a shortcut I’ve taken hundreds of times. Sometimes I would stop to inspect a shoe, or to check the price on a tie. The shoe would be upward of seven hundred dollars. The last tie I looked at was one hundred and eighty.

This Nordstrom had its own coffee shop, restaurant and even a cocktail bar. Curiously, its drinks were no more expensive than any other café nearby and, as I began drafting this in the early spring, I stopped for a drink on my way through. I asked the person serving me about her Totoro tattoo and she beamed. “Nobody who shops here recognises Totoro,” she said, and began talking about her clientele. They don’t have that kind of thing on their minds, she said.

She told me that the stations serving drinks were closing within a week and that she didn’t know if she’d have a job after that. “They’ll probably put us on the shop floor with everyone else at minimum wage.” Her colleague, selling suits that ranged from fifteen hundred dollars to eight thousand, told me he didn’t know when his last day of work would be, nor what kind of severance package anyone would have. Apparently, more than six hundred staff didn’t know when their jobs would end, but if Nordstrom did know one thing it was that it certainly wasn’t making enough money in Canada, with its thousand dollar flip-flops sold by minimum wage staff. It was time for the retailer to skedaddle.

I like talking to working people. Often, the conversations are more grounded than the kind of armchair politics you can abruptly find yourself enmeshed in at a house party, trapped suddenly in a kitchen surrounded by revellers armed with dangerously articulated glasses of wine.

The suit-seller had to go. He was run off his feet. Nearby, a rack of torn, pre-ripped jeans was on sale for three hundred dollars, more than seven times what I paid for my pristine pair. They were hung within grasping distance of some thousand dollar dresses.

I’m not an expert on dresses, but the thing about many of those seven hundred dollar shoes, those thousand dollar flip-flops, is that they were shit. They looked absolutely terrible.