#edward iii

Text

David Tennant in Shakespeare plays

[As you like it , love's labor lost, Richard II, Hamlet, The Comedy of errors, King Lear, Romeo and Juliet, much Ado about nothing, Macbeth]

P.s. he had also been in Edward III as Edward the black prince and the midsummer night's dream as Lysander/flute but I couldn't find any pictures from those plays.

#shakespeare#david tennant#literature#theatre#as you like it#macbeth#hamlet#love's labour's lost#much ado about nothing#romeo and juliet#richard ii#the comedy of errors#king lear#edward iii#a midsummer night's dream#i updated the Macbeth photo because it's fuckin stunning

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

If you want to know who was on the British throne when a ghost died

#bbc ghosts#horrible histories#edward iii#elizabeth i#James vi and I#george iii#george v#meme#george iv

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

ROYALTY MEME | Granddaughters of Edward III & Philippa of Hainault (part two) / (part one)

through their sons: John of Gaunt, Edmund of Langley, and Thomas of Woodstock

#historyedit#historicwomendaily#catherine of lancaster#constance of york#joan beaufort#anne of gloucester#joan lady talbot#perioddramaedit#history#women in history#weloveperioddrama#onlyperioddramas#perioddramasource#cortegiania#userbennet#userperioddrama#edward iii#philippa of hainault#*royalty meme#my edit

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

#hundred years war#art#medieval#middle ages#france#england#knights#knight#soldiers#soldier#armour#banner#standard#pennant#history#europe#european#english#french#edward iii#philip vi#john the good#john ii#jean le bon#philippe de valois#edouard iii d'angleterre#battle of crécy#battle of poitiers#warfare#battle

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

The only case in which a woman was put to trial in Parliament during the later Middle Ages was that of Alice Perrers, the mistress of Edward III. An analysis of this case reveals the deeply misogynistic attitude of Parliament towards women who dared to challenge the patriarchy by acting independently of male authority.

-W. Mark Ormrod, "Women and Parliament in Later Medieval England."

"...In the first Parliament to be held after Edward III’s death in October 1377, there was significant clamour from the Commons for Alice to be put to a further, full-scale parliamentary trial.

Richard II’s minority administration, run by Gaunt, reluctantly bowed to pressure and, at the end of the assembly, brought Alice into Parliament to answer a series of major political charges. In addition, all those wishing to sue her in a private capacity were encouraged to submit petitions under a proclamation announced in the city of London. Although Parliament was formally dissolved before Perrers’ trial was concluded, most of the Commons seem to have remained in the capital to observe the spectacle and did not go down until after the final judgment was given on 3 December. One by one, members of the court of Edward III lined up to confirm the charges against the former king’s mistress [...] Alice was declared guilty of all charges. Her punishment was to be perpetual banishment from the realm, with all her property confiscated to the Crown. The trial of 1377 therefore resulted in a re-affirmation of the ordinance of 1376 and the full—and apparently final—forfeiture of Perrers’ considerable landed estate.

In the next Parliament to meet, the assembly that convened at Gloucester in October 1378, some forty petitions were received in response to the 1377 call for private suits against the former king’s mistress, revealing Alice’s alleged interference in the workings of the courts for personal gain, her unscrupulous property transactions and her persistent disinclination to pay her debts. A number of these petitions were submitted by women acting as femmes soles or in conjunction with husbands [...] Other petitions, from men of various classes, complained of the way in which Alice had brought her influence to bear in the courts such as to block any proceedings they might take against her. Robert Osprynge of London claimed that gold and silver had been worthless when confronted with Alice’s influence in the course of justice.

Ironically, however, this body of private petitions had mostly to be set aside by the royal Council when it was discovered that Alice Perrers had— probably during her period of disgrace in 1376—undertaken a clandestine marriage with Sir William Windsor, Edward III’s former lieutenant of Ireland. Windsor and Alice submitted a joint petition as husband and wife in the Gloucester Parliament, complaining of various procedural errors in Perrers’ trial of 1377. Most seriously and substantively, they reported that they had already been married at the time of that trial. The presumption that Alice, widowed from her first husband, had been put to answer as femme sole was therefore false, and the judgment against her should be nullified. In the end, Windsor did not press his case and preferred the arts of compromise: he reached an informal accommodation with the Council, which allowed him to take over the majority of his wife’s former landed property, but which left her still technically subject to the judgment of 1377. The result was that Alice was doubly compromised, first by her marriage and secondly by her husband’s desire to have complete control of her property and dispose of it to the benefit of his own relatives. Alice remained trapped in this anomalous position until Windsor’s death in 1384, at which point she was able, once again as femme sole, to petition in Parliament for the annulment of the 1377 judgment and the restoration of her estate. Even this, however, did not end Alice’s difficulties, since it proved remarkably difficult to wrest back control of a number of her most valuable properties; and for the rest of her widowhood, Perrers continued assiduously to petition in Parliament for the restoration of her rights.

#historicwomendaily#alice perrers#william windsor#(he seems to have been a shitty husband btw there's evidence that alice felt very bitter about his actions after his death)#edward iii#(kinda not really?)#my post#english history#gender tag#queue

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shakespeare poll tag, for all the different genres!

#shakespeare#king john#richard ii#henry iv#henry v#henry vi#richard iii#henry viii#edward iii#shakespearepolls

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert dressed as the medieval monarchs Edward III and his consort Queen Philippa of Hainault in 1842 for the Queens costume ball. 🎨 Sir Edwin Landseer.

#queen victoria#prince albert#sir edwin landseer#edwin landseer#ktd#british royal family#throwback#brf#art#art history#artwork#medieval#medieval core#Edward iii#queen Philippa#royalty#middle ages#history#victorian#1840s#19th century

37 notes

·

View notes

Photo

↳ the children of Edward III & Philippa of Hainault (that survived infancy)

(requested by anonymous)

#edward iii#philippa of hainault#edward the black prince#isabella of england#joan of england#lionel of antwerp#john of gaunt#edmund of langley#mary of waltham#margaret of england#thomas of woodstock#english history#house plantagenet#*requests#my gifs#historyedit#creations*

387 notes

·

View notes

Note

Isabella of FranceDelayed the coronation of her daughter-in-law, right?

That is the general consensus, right! It was something of a scandal that Philippa of Hainault was pregnant and hadn't been coronated, and that probably forced Isabella's hand into allowing the coronation. Philippa was around six months pregnant with their first child (the future Edward of Woodstock, known famously but anachronistically as the Black Prince) and the ceremony was shortened because of her pregnancy.

Here's Lisa Benz St. John (Three Medieval Queens) on it:

Philippa’s first pregnancy in 1330 may also have marked a coming of age and may have given her symbolic power when she had previously been allowed very little power or authority. Edward and Philippa married in 1328, but she was not crowned until 1330, when she was five months pregnant. This delay was unusual, and it was probably Isabella who stood in the way. There have been several studies linking the legitimacy of the heir and the status of the queen with her coronation rather than her marriage. Philippa’s pregnancy forced Isabella’s hand; an uncrowned consort could not give birth to a rightful heir. The coronation did not change Philippa’s inability to act as queen during Edward III’s minority. Even so, a coronation, like a pregnancy, would create the perception of Philippa’s status as queen consort among her contemporaries. The perception that the queen possessed power, as discussed in Chapter Three, was connected to the actual practice of power in highly complex ways. Once contemporaries believed in her power as queen, they might actively begin to seek her aid, which would allow her to practice queenship and manipulate this agency further, increasing her power and authority. By delaying Philippa’s coronation for as long as possible, Isabella was signifying to the court and to the realm her position as the only true queen with any power, both symbolic and achieved.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

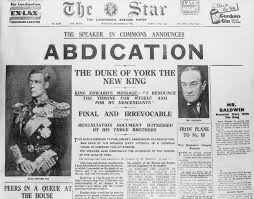

After ruling for less than one year, Edward VIII abdicates #OnThisDay in 1936.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

In such wise did the Prince make stay in Gascony, and abode there the space of eight months or more. Very great was his valour. When it came towards summer then he assembled his forces, and rode again into Saintonge, Périgord and Quercy, and came as far as Romorantin. There he took the tower by assault, and the Lord Bouciquaut also, and the great Lord of Craon and a goodly number of others; more than two hundred were taken there, all men-at-arms of high renown, fifteen days before the battle of Poitiers. Thereafter he rode into Berry, and through Gascony also, and up to Tours in Tourayne. Then the tidings came to King John, whereat he made great lamentation, and said that he would lightly esteem himself if he did not take great vengeance.

#perioddramaedit#history#edit#middle ages#medieval#edward of woodstock#edward the black prince#the black prince#edward iii#santiago cabrera#perioddramasource#perioddramacentral#plantagenet#philippa of hainault#joan of kent#period drama#edward woodstock#english history#historical figures#historical#historyedit#14th century

79 notes

·

View notes

Link

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

ROYALTY MEME | Granddaughters of Edward III & Philippa of Hainault (part one)

through their children: Lionel of Antwerp, John of Gaunt, and Isabella of England

#historyedit#historicwomendaily#philippa plantagenet#philippa of lancaster#elizabeth of lancaster#marie de coucy#philippa de coucy#edward iii#philippa of hainault#history#women in history#weloveperioddrama#cortegiania#userperioddrama#perioddramaedit#userbennet#perioddramasource#onlyperioddramas#*royalty meme#my edit

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

Edward III Crossing the Somme by Benjamin West

#edward iii#somme#art#benjamin west#battle of blanchetaque#king edward iii#history#europe#european#france#england#knights#medieval#middle ages#knight#the hundred years war#hundred years war#kingdom of england#kingdom of france#armour#flags#english

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

"In the early 1360s Edward III took as his mistress Alice Perrers, the daughter of a London goldsmith and widow of one of the King’s jewellers, Janyn Perrers. Alice’s opponents would later viciously exaggerate her low birth—Thomas Walsingham claimed that her father was a thatcher—so it has only been in this century that her true identity was revealed by Mark Ormrod and Laura Tompkins. Alice became one of Philippa’s demoiselles, but supplemented her income from Philippa with a role as a moneylender to merchants and gentry. During Philippa’s lifetime she began investing her wealth in property that, Tompkins has estimated, would eventually approach £2000 per annum in value—an income that exceeded that of some earls.

Alice bore the King a son, John Southeray, in about 1365 and from 1367 she received a number of royal grants. Her name is notably absent from the list of Philippa’s ladies who received bequests in the Queen’s will. Philippa died in 1369 and, unlike other widowed kings of the later Middle Ages, Edward III seems to have made no attempt to look for a replacement queen. Alice then emerged as a public figure, richly rewarded by the King, and sought out by courtiers for her influence over him. In 1373 Edward gave her a collection of the queen’s jewels and the following year the Pope himself included her among those he petitioned to influence Edward III to engineer his brother’s freedom from captivity. Alice subsequently stole the show at a royal tournament at Smithfeld when she dressed as “the Lady of the Sun.” Her choice of outft was probably a deliberate spin on Edward III’s own sunburst emblem.

Alice was indubitably a skilled businesswoman with an impressive grasp of property law, but she was also abusing her closeness to the King in order to build up her wealth. Moreover, contemporaries identifed her as the heart of a disruptive and malign court clique. Tompkins has argued that Alice’s powerful and self-serving influence over the King was perceived as “inverting queenship.” During the Good Parliament of 1376, Alice was condemned for the use of maintenance, accused of taking thousands of pounds from the Exchequer, and ordered to stay away from the court, under threat of banishment.

Thomas Walsingham reported that at this time her accomplice in seducing the King was also arrested, a Dominican friar who was an “evil magician” and had used wax effgies of the King and Alice to enable her to “get whatever she wanted from the King.” There is no corroborating evidence for this story of arrest, but the idea that low status women could only attract the admiration of kings or nobles through witchcraft was a pervasive one, especially apparent in Elizabeth Woodville’s story [...], and probably also in that of a later quasi-queen, Eleanor Cobham [...].

Just months after the Good Parliament, the King had pardoned Alice, but he died the following year. At some point in the 1370s she had taken a second husband, Sir William Windsor, who spent most of his career in Ireland. In the autumn of 1377, Alice was accused of having persuaded Edward III to countermand an order to investigate charges against Windsor the previous year and to pardon one of her business associates. Alice was sentenced to banishment and forfeiture of all goods and lands. Although this banishment was revoked in 1379, her subsequent attempts to regain her possessions were consistently frustrated. She died in the winter of 1401–1402, bequeathing her “usurped” lands to her two daughters by the King. Their son had predeceased her.

Unlike the later quasi-queens, Alice’s position came from sharing a king’s bed and was thus closer to that of an actual consort. By contrast, her low social status and ineligibility to produce an heir to the throne made her less like a queen consort than her successors. She was thus better physically positioned to exert influence but ideologically wholly separated from any authority to do so."

J.L Laynesmith and Elena Woodacre, "The Later Medieval English Consorts: Power, Infuence, Dynasty", "Later Plantagenets and Wars of the Roses Consorts"

#she 💜#historicwomendaily#alice perrers#edward iii#i guess#14th century#english history#the way people talk about her is so disgusting#imagine thinking that a teenage commoner 'seduced' or 'took advantage of' the 50+ year King of England#my post

46 notes

·

View notes