#empire français

Text

Portrait of Napoleon III, Emperor of the French, in Coronation Robes. After Franz Xaver Winterhalter.

#franz xaver winterhalter#coronation robes#napoleon iii#empereur#maison bonaparte#buonaparte#bonaparte#dynastie bonapsrte#official portrait#costume de sacre#full length portrait#empire français#french empire#full-length portrait

23 notes

·

View notes

Link

Wavre. Reconstitution de la bataille oubliée en 2017

#Wavre#Reconstitution#Bataille oubliée#Armée#Chevaux#Emmanuel Grouchy#Napoléon#Empire#Empire français

0 notes

Photo

3 avril 1814 : Napoléon est destitué par le Sénat ➽ http://bit.ly/Decheance-Napoleon En mars 1814, Napoléon est battu, la France est envahie, et l’Empire s’effondre, le Sénat reprochant bientôt à Napoléon les violations du pacte constitutionnel et prononçant sa déchéance, fixant également que le droit d’hérédité établi dans sa famille est aboli

#CeJourLà#3Avril#Napoléon#empereur#décret#déchéance#destitution#Sénat#Empire#politique#histoire#france#history#passé#past#français#french#news#événement#newsfromthepast

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Napoleon and Universities

From University of Bordeaux — Our History page, updated 28/06/2022

“In 1793, the University of Bordeaux disappeared like all French universities following a decision of the Convention (Parliament that governed France from September 1792 to October 1795 during the French Revolution) which saw in these corporations a remnant of the Ancien Régime.”

“Napoleon Bonaparte restored the concept of the university in 1806. In Bordeaux, the Faculty of Theology was recreated in 1808 and those of Letters and Sciences in 1838.”

[bold in original]

———

In original French:

Source: Université de Bordeaux — Notre histoire

#Bordeaux#France#Université de Bordeaux#university#Napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#University of Bordeaux#college#universities#1806#1800s#napoleonic era#napoleonic#first french empire#french empire#19th century#academia#Napoleon and education#education#convention#the convention#french revolution#history#french history#la révolution français#napoleonic reforms#Napoleon’s reforms#reforms

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tirs de nuit à Na San et “lucioles” éclairantes. Le PA mo. 9 tire sur le PA 24, enlevé par le Viêt-minh. Nuit du 30 novembre au 1er décembre 1952.

Photo par Raymond Cauchetier.

Marina Berthier, La bataille de Na San Indochine. ECPAD, Fonds Indochine. p. 19.

#na san#bataille de na san#guerre d'indochine#guerrilla warfare#night attack#night photography#flares#corps expéditionnaire français#counterinsurgency#indochina war#indochine française#french colonial empire#stronghold

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

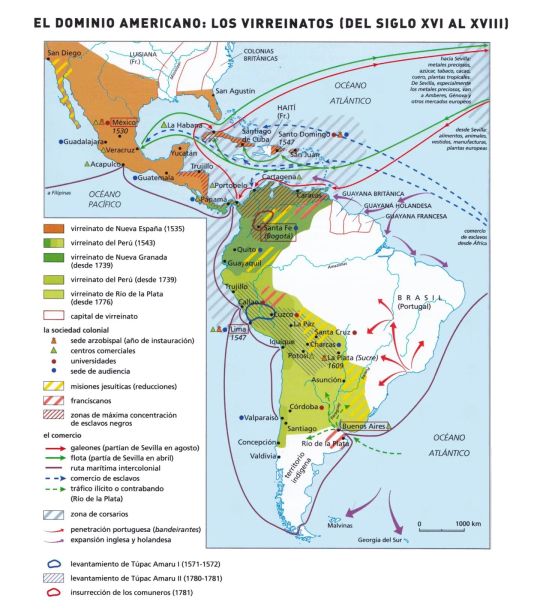

The evolution of the Spanish West Indian Empire

« Atlas histórico de España », Jordi Induráin Pons, Larousse, 2021

by cartesdhistoire

In the 18th century, Spanish America was firmly established: the conquest phase having been completed, pacification opened the way to a reorganization of the administration of this immense territory. It was necessary to take into account the evolution of the population (since the law of 1514 allowing marriage between Spaniards and Indians, interbreeding was the central axis) and the rapid integration of the Río de la Plata to the south. Furthermore, the rise of the English and French Caribbean islands encouraged Spain to see its own islands as something other than naval relays to the continent.

The real administrative structure was the urban network, which allowed the Spaniards to immediately have control of the territory. Cities were political, administrative and religious centers, defensive sites and points of convergence for commercial and economic activities. They were created at the outlets of rich agricultural lands, most often at altitude to avoid tropical diseases, even if commercial necessities sometimes led to exceptions, as for Lima, built at sea level.

The plan of these new towns followed the same logic: a central square, with the church, the palace of the governor or viceroy, the town hall, seat of municipal power. The checkerboard plan structured the city. According to the Castilian model, the municipal power representing the local elites, the “cabildo”, was elected. Urban power was, throughout the colonial era, a center of passive resistance to distant injunctions from central power. Richly decorated, with public and private buildings of grandiose architecture, Spanish cities were incomparably more luxurious than their British or French counterparts in America. Montreal, Philadelphia or Cap-Français could not compare to the splendors of Bogotá, Caracas and even less so with Havana and Cartagena de Indias.

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

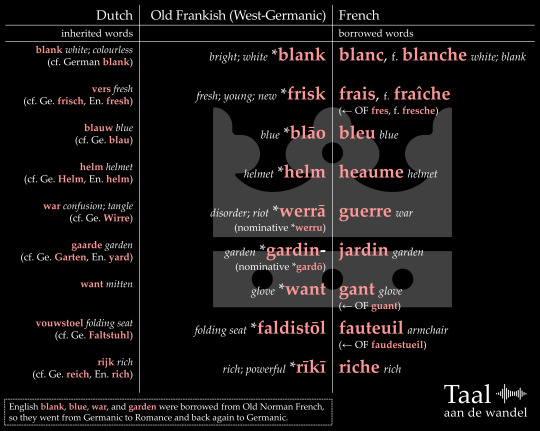

In the Early Middle Ages, the ancestor of French borrowed many words from Old Frankish, a Germanic language spoken by the elite of the Frankish Empire. When this elite adopted the Romance language, it got their name: françois, now français: French. Here are some of the borrowings.

#french#old french#old frankish#west germanic#dutch#german#english#borrowing#historical linguistics#linguistics#language#etymology#latin#lingblr

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Le Maréchal Berthier : Pilier de l'Empire Napoléonien

Né le 20 novembre 1753 à Versailles, Louis Alexandre Berthier est bien plus qu'un simple militaire. Sa destinée est intimement liée à celle de Napoléon Bonaparte, forgeant ainsi une alliance indéfectible au service de la France.

Dès son jeune âge, Berthier se distingue par son esprit vif et son dévouement à la patrie. Son ascension fulgurante au sein de l'armée française le mène rapidement à croiser la route du futur Empereur des Français.

Berthier participe sous les ordres de Bonaparte aux campagnes d'Italie puis d'Égypte et soutient le coup d'État du 18 Brumaire.

En tant que chef d'état-major de Napoléon, Berthier joue un rôle crucial dans la planification et l'exécution des campagnes militaires qui ont marqué l'histoire. Sa rigueur tactique et son génie organisationnel contribuent grandement aux victoires éclatantes de l'Empire, malgré son incapacité à diriger lui-même une armée.

La mort tragique de Berthier en 1815, suite à une chute mystérieuse d'une fenêtre de l'hôtel de son épouse à Bamberg, laisse un vide profond dans l'entourage de Napoléon.

Son décès précède en effet de quelques jours la bataille de Waterloo, où l'absence de cet excellent chef d'état-major se fait cruellement sentir pour l'Empereur qui dira de lui : "Nul autre n'eût pu le remplacer"

Berthier décide pourtant de suivre Louis XVIII lors de la Restauration, et adhére même au décret du Sénat qui exclut Napoléon du trône.

***

L'héritage du maréchal Berthier perdure à travers les pages de l'histoire. Son influence indélébile sur la stratégie militaire et l'administration de l'Empire demeure incontestée, faisant de lui l'un des piliers incontournables de l'épopée napoléonienne.

***

Marshal Berthier: Pillar of the Napoleonic Empire

Born on November 20, 1753, in Versailles, Louis Alexandre Berthier is much more than a mere military figure. His destiny is intimately intertwined with that of Napoleon Bonaparte, thus forging an unbreakable alliance in service to France.

From a young age, Berthier distinguished himself with his sharp intellect and dedication to his homeland. His rapid ascent within the French army quickly led him to cross paths with the future Emperor of the French.

Berthier participated under Bonaparte's command in the campaigns in Italy and Egypt, and supported the coup d'état of the 18th Brumaire.As Napoleon's chief of staff, Berthier played a crucial role in the planning and execution of military campaigns that have left an indelible mark on history. His tactical rigor and organizational genius greatly contributed to the Empire's resounding victories, despite his own inability to lead an army himself.

The tragic death of Berthier in 1815, following a mysterious fall from a window of his wife's hotel in Bamberg, left a profound void in Napoleon's inner circle.Indeed, his death preceded by a few days the Battle of Waterloo, where the absence of this excellent chief of staff was keenly felt by the Emperor who said of him: "No other could have replaced him."

However, Berthier decided to follow Louis XVIII during the Restoration, and even adhered to the Senate decree which excluded Napoleon from the throne.

***

The legacy of Marshal Berthier endures through the pages of history. His indelible influence on military strategy and the administration of the Empire remains unquestioned, making him one of the indispensable pillars of the Napoleonic epic.

#bonaparte#france#napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#guerre#soldats#Maréchal#Berthier#louis alexandre berthier#napoleonic wars#napoleonic era#napoleonic

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Victor Hugo wrote from Jersey, "You are restoring Voltaire to us, supreme consolation for France, humbled and silent." Would it be well to publish this compromising letter? Dumas wanted to. He loved Hugo's poems, Les Chatiments, stanzas of which he recited on every occasion, for he had brought back from Belgium steady animosity against the Empire...

But the police held the press in an iron grip and so Dumas listened to the counsels of prudence and let the great Victor's letter go unpublished. Later he regretted it and three years after, in March, 1857, he seized the opportunity to express again his admiration for the exile. When the actress Augustine Brohan dared to attack Hugo in Le Figaro, he took her violently to task and even ventured to demand of the Théâtre-Français that this person should not act in any of his plays. He had of course neither the right nor the power to prevent her, but Hugo was grateful for the gesture. "I love you more every day," he wrote from Hauteville House, "not alone because you are one of the brilliant lights of my century, but because you are one of its consolations."- The Fourth Musketeer

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ruthless Representatives, Unjust Executions (1/3): the Death of an Artillery Captain

This is a response to @josefavomjaaga's recent post, which partially deals with the alleged arrest and execution of an artillery captain by Saint-Just, then a representative on mission, during the siege of Charleroi, and the representatives' abuse of military men around the time of the battle of Fleurus. Josefa enquired whether anyone could shed light on this incident from the FRev community. While I am not well-versed in FRev events, I would like to offer some of my findings about military justice in the army during the Revolution in relation to the representatives in three parts. The first part deals directly with the tale of Saint-Just's execution of the artillery captain, and how it was turned into a symbol that exemplifies the Revolution's extrajudicial violence. All translation errors are my own.

The source about Saint-Just's terrorisation and execution of the artillery captain that is cited the most is from Soult’s memoirs (1854). Writers, including Colonel Phipps, use this source verbatim without questioning it, because Saint-Just and all the representatives were obviously Stupid Civilians who thought that any incompletion of their orders amounted to betrayal:

It was above all the siege division which deployed with activity before Charleroi. The colonel Marescot directed the engineering operations, under the eyes of Generals Jourdan and Hatry; we had a sufficient artilery crew, and the representatives Saint-Just and Lebas stood at the foot of the trench to speed up the work. One day, they visited the site of a battery that had just been marked out: "At what time will it be finished?" asked Saint-Just of the captain responsible for having it executed. "That depends on the number of workers that I will be given; but we will work relentlessly," responded the officer. "If tomorrow, at six o'clock, she is not ready to fire, your head will fall off!..."

In this short time, it was impossible for the work to be completed; even though as many men were put there as the space could contain. It was not entirely finished when the fatal hour struck; Saint-Just kept his horrible promise: the artillery captain was immediately arrested and sent to his death, because the scaffold marched in the wake of the ferocious representatives. (pp. 156-157)

Saint-Just, in Soult's depiction, is the proper Archangel of Death, guillotining everything that stands in his path. In portraying Saint-Just thus, Soult criticizes the representatives' murder of an innocent man. Worse, he depicts representatives as civilians that can only stand around instead of hardworking soldiers bringing the siege to fruition, making their commands unjustified. Soult condemns the fact that a civilian's word could be the injust law that separated soldiers from life or death.

That said, as Soult is no friend of the political figures of the Revolution, his remembered account requires precise corroboration to be valid. I found one earlier source that describes, presumably, the same incident, from Victoires, conquêtes, désastres, revers et guerres civiles des Français, de 1792 à 1815, vol. 3. It was written in 1817 by "a society of soldiers and men of letters", and edited by Charles Théodore Beauvais de Préau, a general of the Revolution and Empire. Though this anonymisation may have been taken to avoid the wrath of the Bourbons in the Restoration, it means we have no idea who wrote the following section, nor their intentions:

This fierce man [Saint-Just], who never showed himself in the trench, informed that a captain of the first regiment of artillery had been somewhat negligent in the construction of a battery of which he was in charge, had him shot in the trench. At the same time, he gave General Jourdan the order to arrest, and consequently have shot on the spot, the General Hatry, commander of the besieging troops, the General Bellemont, commander of the artillery, and the commander Marescot. The General Jourdan had, at the risk of his own life, the courage to resist the wishes of this gutless representative. The officers of whom we have just spoken of had the audacity of protesting against the cruel sentence which condemned the unfortunate artillery captain Méras, and, in his his atrocious delirium, Saint-Just dared to accuse them of complicity. (p. 47)

If we infer from the title of this source that the editor compiled the accounts of his comrades, then this account was written by a former Revolutionary and Imperial officer who could have some memory of the incident. However, many aspects of this text don’t line up with Soult’s account, including the way the captain was executed (shot in the trench here, guillotined in Soult's account). Saint-Just's successive condemnation of high-ranking officers, which highlights how much power he had over even the highest echelons of the army, also does not appear in Soult's account. But we do have a name for the captain: Méras. His name, in fact, appears in a 1797 publication: L'observateur impartial aux armées de la Moselle, des Ardennes, de Sambre et Meuse, et la Rhine et Moselle, a memoir by Pierre Charles Lecomte, at the time "the conducteur general of the artillery in the Army of the Rhin-Moselle [sic]". This is his account on the affair, relegated to a footnote:

Before giving the details of the capitulation of Charleroi, I must cite a horrible feature of the role of Representative Saint-Just.

The French proconsul ordered the construction of a battery that he thought was necessary.*

The general Bollemont [sic] entrusted its execution to an artillery captain, named Méras. All the shovels, pickaxes, and other utensils happened to be employed in other work, the orders of the Representative could not be executed. The morning of the next day, passing close to the location where the battery was supposed to be constructed, he [Saint-Just] shouted, raged, sent to search for the captain; and, without listening to his reasons, he had him arrested. Two days later, when his [Méras’] company was battling against the enemy, he [Saint-Just] had him taken from the prison, he had him conducted to the middle of his works; and there, o misery! o inhumanity! he had him assassinated. At night his company returned to the camp covered in glory; they learned that their chief had been shot; they surrendered to despair. They wanted to go to the tyrant: they were stopped, under the fear that some of these brave soldiers would have become new victims. Méras was so much loved, that all of the artillery wanted to enact vengeance on his assassin. This almost universal rumour made itself heard amongst the trenches; and, for preventing it from having consequences, the company of the unfortunate Méras was sent into the interior.

*We know that there was a time when the Representatives, often little-instructed in the military arts, dared impudently to command old soldiers whose arms had dulled, and obliged them to sacrifice, according to their whims, some thousands of brave soldiers. (p. 38-39)

Once again, the details contradict even more with Soult’s account, and with that of the 1817 one. Soult says as much help as possible was given to the artillery captian, but Lecomte says all other workers were occupied and that captain received little help (presumably because the battery was militrarily unimportant). Méras’ misery is stretched out over two days instead of him being shot immediately, and it is not the generals who protested against Méras' execution that Saint-Just raises a hand against, but Méras' entire company, which the civilian government sends to the Vendée. The message could not be clearer: under "tyrannical representatives" like Saint-Just, the Revolution is eating its soldiers, the common people it was supposed to protect.

Is this the truth of the matter, since it is the earliest version? The publication is contemporary enough, but I am inclined to doubt the reliability of a text explicitly titled “impartial”. A look at the author's background reveals his attitudes. Lecomte was, according to BnF data, the maître de pension in Versailles until 1792 (presumably up to the abolishment of the monarchy), then the inspector of octroi taxes in Paris until 1815. Seeing that he served the First Empire, I am inclined to think that he was no die-hard revolutionary, and certainly not part of the Montagnard faction. Furthermore, he published his account after the fall of the Montagnards, during the height of the Directory. This makes the affair more likely to be Thermidorian propaganda, and indeed Lecomte even admits that his account was an “almost universal rumour”, not a fact, because in his story, no one is present at the scene of Méras’ death other than Saint-Just and his executioner. This makes the account unverifiable, and makes it more likely to be fabrication.

It would seem that, after Saint-Just’s death, the army’s fear and hatred of representatives turned into slander against their characters, often resulting in widely circulated variants of the same tale to emphasise different effects. The 1797 version highlights Saint-Just’s cruelties as a tyrant against the “small folk” of the Revolution and uses exclamatory language to amplify the reader's pathos. The 1817 version emphasises Saint-Just’s power over even the generals of the army, exaggerating his dictatorship. Finally, in Soult’s memoir, Saint-Just is not just a dictator who could dismiss soldiers with a wave of a hand. He and the representatives were synonymous with the guillotine and the excesses of the Revolution themselves.

The accounts of Saint-Just condemning Méras to death are inconsistent, and should amount to nothing more than invalid hearsay, which tells us nothing of the representatives' historical actions. If anyone has more information on the topic or the wider subject, feel free to add to this.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Empress Joséphine.

#engravings#josephine de beauharnais#bonaparte#maison bonaparte#full length portrait#dynastie bonaparte#buonaparte#french empire#empire français#impératrice joséphine#full-length portrait

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

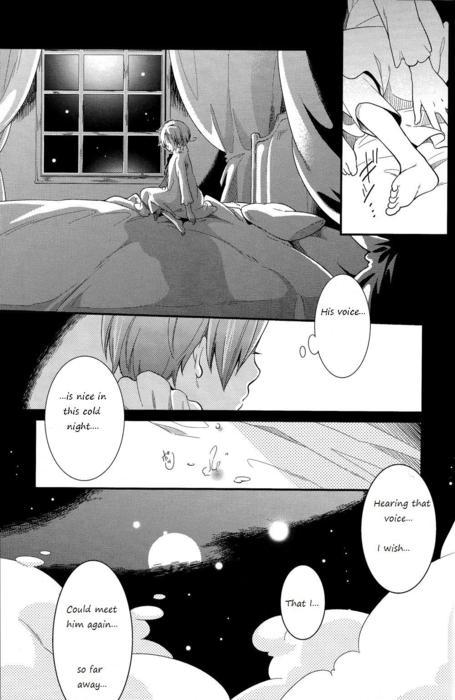

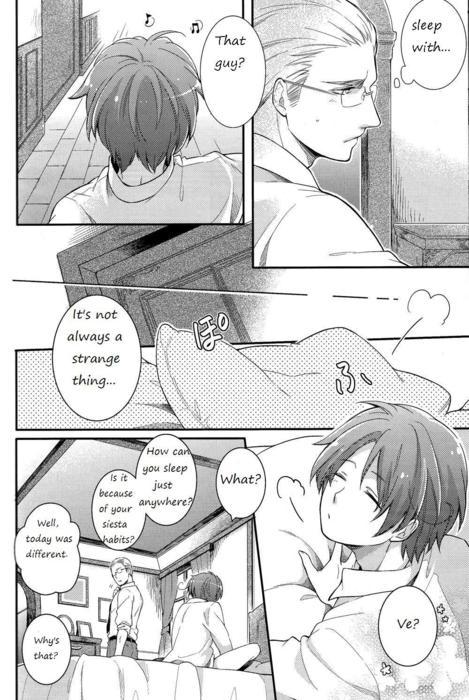

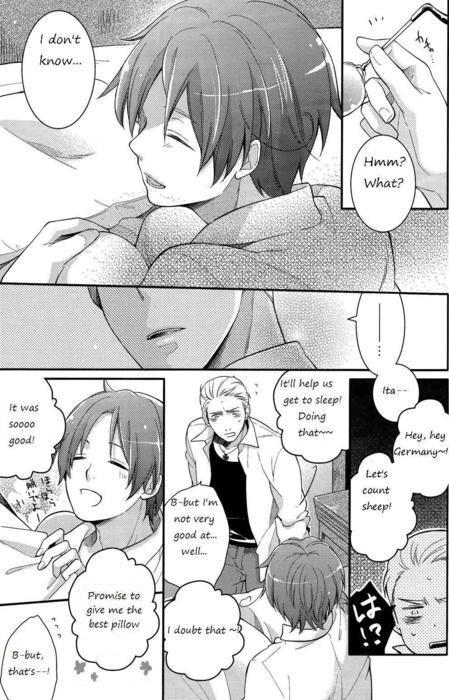

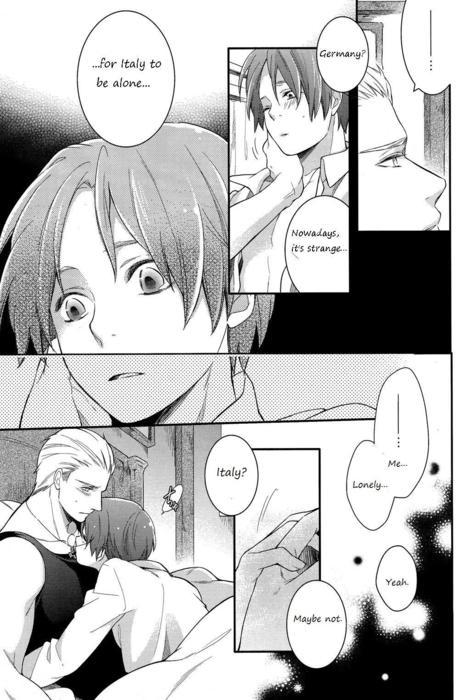

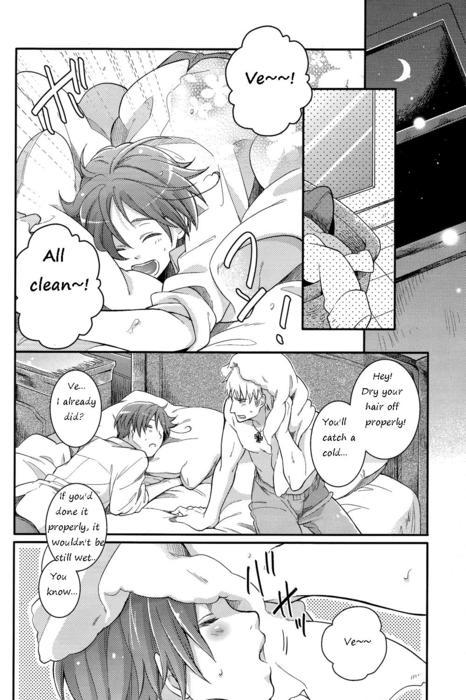

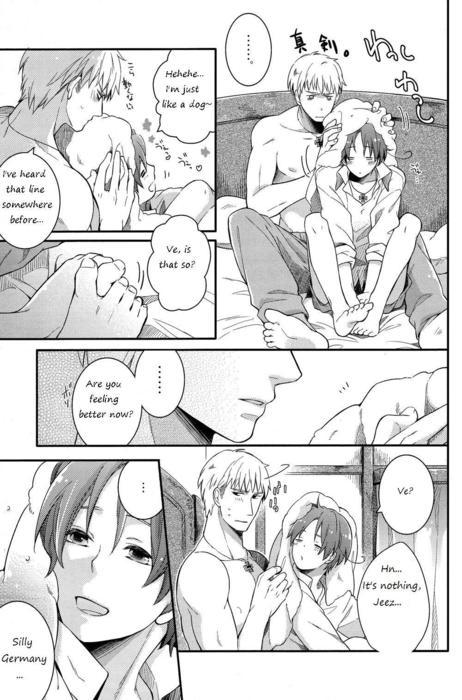

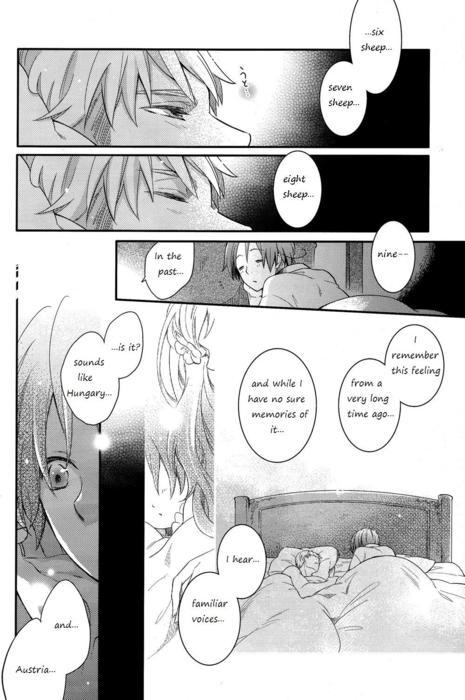

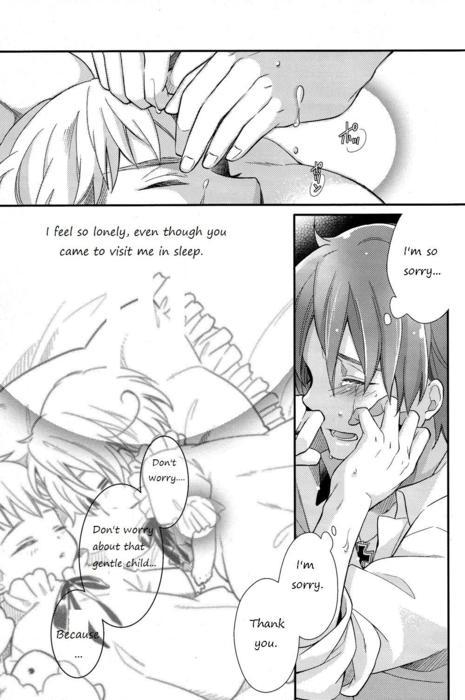

Hetalia “Little Sheep”/”Counting Sheep” [Censored]

Characters: Italy, Holy Roman Empire, Germany

Pages: 44

Translated by: ai jinsei

Vibes: emotional, sad, painful, mellow, cute

CW: used to be nsfw but I have removed the pages 👍

Summary: Italy has trouble sleeping remembering his days with Holy Rome

Other languages: Spanish/Español, French/Français

Text below: “For my sake, Italy is...!”

#hetalia#hetalia doujinshi#hetalia italy#hetalia holy roman empire#hetalia chibitalia#hetalia germany#hetalia GerIta#aph italy#aph holy roman empire#aph germany#aph gerita#aph hretalia#aph hretaly#aph chibirome#feliciano vargas#ludwig beilschmidt#gerita#hretalia#spanish#french

38 notes

·

View notes

Photo

8 février 1807 : bataille d’Eylau ➽ http://bit.ly/Bataille-Eylau La victoire d’Iéna (octobre 1806) livrait à Napoléon la monarchie prussienne. Déjà l’armée française occupait tout le pays situé de l’Elbe à l’Oder, lorsque l’armée russe parut sur la Vistule : elle arrivait tard, parce que l’empereur Alexandre n’avait pu prévoir une conquête si rapide

#CeJourLà#8Février#bataille#Eylau#Napoléon#Bonaparte#Empereur#armée#guerre#empire#histoire#france#history#passé#past#français#french#news#événement#newsfromthepast

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Napoleon I, Emperor of the French, King of Italy

Friedrich Wilhelm Reuter

1806

#Napoleon#king of Italy#emperor of the French#France#Italy#first French empire#french empire#19th century#histories#napoleonic era#art#napoleonic#empire#Napoleon Bonaparte#poster#history#historical#emperu#empereur des français#empereur#1er empire#first empire#French Revolution#1806#Friedrich Wilhelm Reuter#Reuter#friedrich#Germany#German art#italia

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

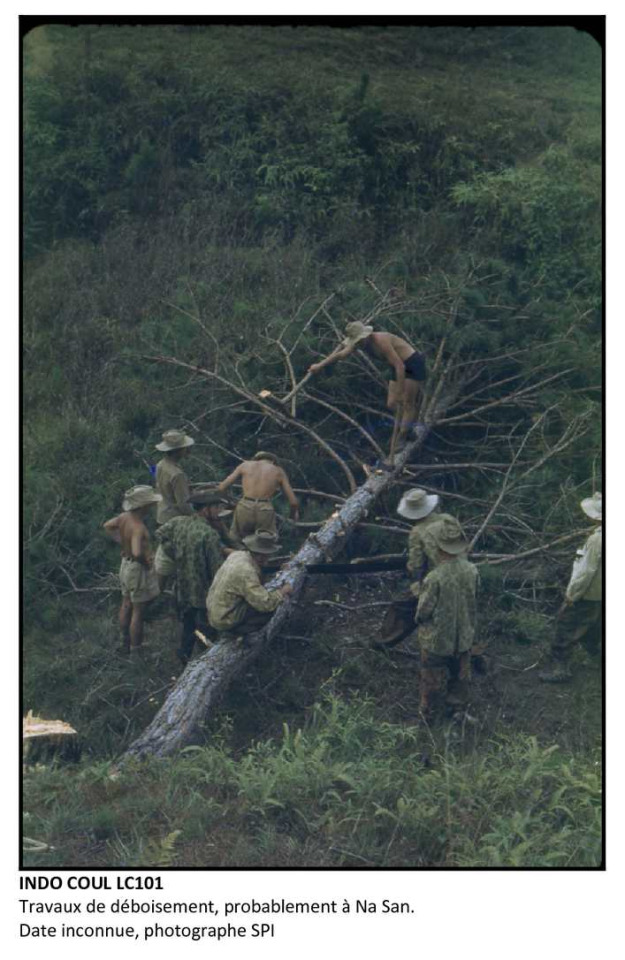

“Travaux de déboisement, probablement à Na San.”

Date inconnue, photographe SPI.

Marina Berthier, La bataille de Na San Indochine. ECPAD, Fonds Indochine. Page 10.

#na san#bataille de na san#guerre d'indochine#armée française#corps expéditionnaire français#military base#camp retranché#military preparations#déboisement#counterinsurgency#indochina war#french indochina#french colonial empire

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Napoléon V: Dear deputies, dear senators,

We French have the reputation of waiting for a great political upheaval to satisfy public opinion. Personally, I am deeply convinced that we must do Good in order to earn the country's trust. My Government will dedicate itself entirely to this task.

I must, in view of the many questions, answer them. Only well-defined causes create deep convictions, just as highly deployed flags inspire sincere devotion.

Is the Empire an enemy? Some of us see it as a retrograde policy, an enemy of the Enlightenment, eager to prevent world peace through its ambitions. The Empire would be the antithesis of the civilizing French Revolution.

No. See for yourself, the Third Empire has kept all these revolutionary principles at the head of its Constitution. That is exactly what the Empire is: it frankly adopts everything that can ennoble hearts and exalt minds for the Good. Against abstraction, the Emperor, who embodies the Constitution, must have a strong Power, because the march of any new power is a struggle.

The prerogatives of the Power of the Emperor are a decoy which serves as a pretext to the hostile parties. Many of you expect a crackdown on the rebels. How can the death of a man benefit a supposedly noble cause in the very country of the Rights of Man and Citizen?

One saw some men, during the tragic night of the death of my father the Emperor, agitating the country and confessing themselves highly enemies of the national institutions. They reject with disdain your votes. They use their political rights only to undermine our institutions.

Members of Parliament, you will not allow such violence to be repeated. Since the pacification of spirits must be the constant goal of our efforts, you will help me to seek the means to silence extreme opposition. I eagerly welcome all those who recognize the national will. To the others, let them know that their time is over.

⚜ Le Cabinet Noir | Palais des Tuileries, 1 Floréal An 230

Beginning ▬ Previous ▬ Next

Emperor Napoléon V makes a speech to the French Parliament. He calls for the union of parties for the protection of national institutions. He also called for the opening of parliamentary discussions on the repression of revolts. Finally, the coronation of Emperor Napoléon V will take place in autumn of the year 230.

Napoléon V : Chers députés, chers sénateurs,

Nous, Français, avons la réputation d'attendre un grand bouleversement politique pour satisfaire les opinions publiques. Personnellement, je suis intimement convaincu qu'il faut plutôt faire le Bien pour mériter la confiance du pays. L'action de mon Gouvernement s'y consacrera entièrement.

Je me dois, au-vu des nombreuses interrogations, d'y répondre. Il n'y a que les causes bien définies qui créent de convictions profondes, tout comme les drapeaux hautement déployés inspirent des dévouements sincères.

L'Empire est-il un ennemi ? Certains d'entre nous y voient une politique rétrograde, ennemi des Lumières, désireux d'empêcher la paix dans le monde par ses ambitions. L'Empire serait aux antipodes de la Révolution Française civilisatrice.

Non. Voyez par vous-même, le Troisième Empire a gardé tous ces principes révolutionnaires en tête de sa Constitution. C'est exactement cela, l'Empire : il adopte franchement tout ce qui peut ennoblir les cœurs et exalter les esprits pour le Bien. Contre l'abstraction, l'Empereur qui incarne la Constitution, doit avoir un pouvoir Fort, car la marche de tout nouveau pouvoir est une lutte.

Les prérogatives du Pouvoir de l'Empereur sont un leurre qui sert de prétexte aux partis hostiles. Beaucoup d'entre vous attendent une répression face aux révoltés. Comment la mort d'un homme peut-elle profiter à une cause prétendue noble au sein même du pays des Droits de l'Homme et du Citoyen ?

On a vu quelques hommes, durant la nuit tragique de la mort de mon père l'Empereur, agiter le pays et s'avouant hautement ennemis des institutions nationales. Ils rejettent avec dédain vos suffrages. Ils n'usent de leurs droits politiques que pour miner nos institutions.

Membres du Parlement, vous ne permettrez pas qu'une telle violence se renouvelle. La pacification des esprits devant être le but constant de nos efforts, vous m'aiderez à rechercher les moyens de réduire au silence les oppositions extrêmes. J'accueille avec empressement tous ceux qui reconnaissent la volonté nationale. Aux autres, qu'ils sachent que leur temps est révolu.

#simparte#gen 2#sim : louis#sim : charlemagne#ts4#sims 4#sims 4 royalty#sims royalty#royal sims#le cabinet noir#tuileries#ts4 royal#ts4 royalty#ts4 royal legacy#ts4 royals#ts4 royal simblr#ts4 royal story#sims 4 royal story#sims 4 royal#sim : annie#sim : henri#sim : philippevictor

39 notes

·

View notes