#george klauber

Text

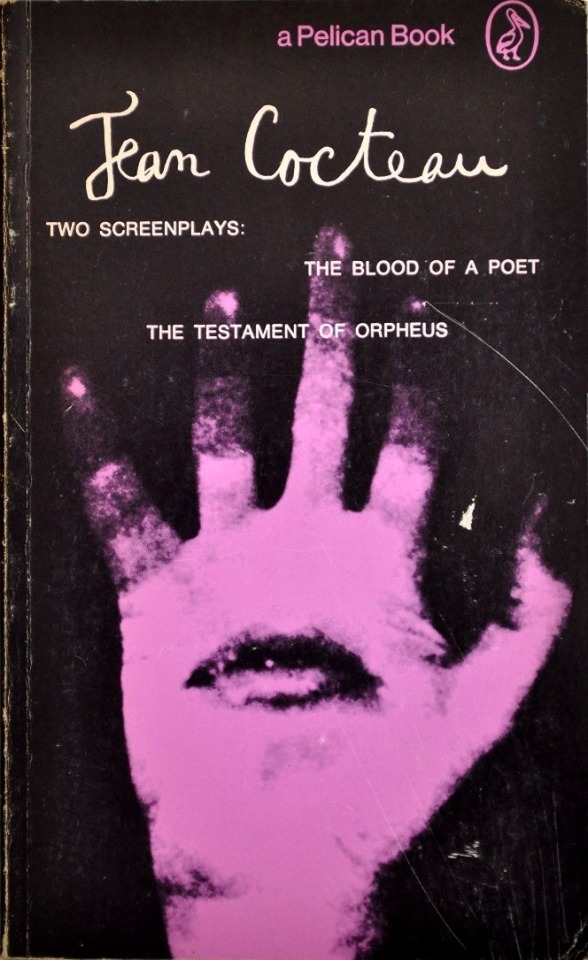

Jean Cocteau - Two Screenplays - Pelican - 1969 (cover design by George Klauber)

#witches#screenplayers#occult#vintage#two screenplays#screenplays#the blood of a poet#the testament of orpheus#pelican books#jean cocteau#1969#george klauber

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Saint: Vendetta for the Saint - Part 2 (6.16, ITC, 1969)

"Out of everyone in this room, only two people have no reason to lie: you and I."

"And how do you reason this?"

"We are both about to die."

#the saint#vendetta for the saint#1969#leslie charteris#john kruse#harry w. junkin#jim o'connolly#roger moore#ian hendry#rosemary dexter#aimi macdonald#finlay currie#george pastell#marie burke#peter madden#alex scott#anthony newlands#steve plytas#gertan klauber#steven berkoff#ricardo montez#where the fiction makers was shot as two episodes planned to be stitched together for cinema release‚ Vendetta had the opposite production#ie. it was shot as a film and then cut into two for tv; this means that this 2nd ep is the only episode in 118 not to feature Simon being#introduced by name and getting the halo effect before the credits. instead we get a montage of last week's events! some other small tics#are evidence of this backwards creation; this ep also carries the film's 'the end' onscreen title before the proper end credits#truthfully this second part can't quite live up to the first; all the plot and intrigue is more or less sorted out in part 1 and so this#ep is mostly concerned with back and forth chases‚ gun fights and showdowns. they're pretty good (we're still in Malta after all) but it#does mean that it's sort of all show and no brains for the wrap up. oddly‚ despite the two eps heavily playing up the vendetta aspect and#Simon hinting more than once that he's willing to outright kill Hendry's big bad‚ he survives the finale. it would make more sense if Simon#had got a line about mercy or something or just acknowledged it‚ but nothing. ho hum. not a bad two parter!

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

BAD TIMING (1980)

Grade: B-

I didn’t think it was a mystery film, but more an exotic thriller. It will be made different now for sure. The ending is pretty good.

#Bad Timging#1980#C#Drama Films#Nicolas Roeg#Vienna#Overdose#Art Garfunkel#Theresa Russell#Denholm Elliott#Dana Gillespie#Harvey Keitel#Daniel Massey#William Hootkins#Eugene Lipinski#George Roubicek#Gertan Klauber#Cheating#Rape

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Self Portrait/Portrait of George Klauber, Philip Pearlstein, 1948-1949, Brooklyn Museum: Contemporary Art

© Philip Pearlstein

Size: 25 x 18 x 1/4 in. (63.5 x 45.7 x 0.6 cm) frame: 31 15/16 x 24 7/16 x 4 7/8 in. (81.2 x 62 x 12.4 cm)

Medium: Casein on masonite

https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/168771

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ida Estelle Taylor (May 20, 1894 – April 15, 1958) was an American actress, singer, model, and animal rights activist. With "dark-brown, almost black hair and brown eyes," she was regarded as one of the most beautiful silent film stars of the 1920s.

After her stage debut in 1919, Taylor began appearing in small roles in World and Vitagraph films. She achieved her first notable success with While New York Sleeps (1920), in which she played three different roles, including a "vamp." She was a contract player of Fox Film Corporation and, later, Paramount Pictures, but for the majority of her career she freelanced. She became famous and was commended by critics for her portrayals of historical women in important films: Miriam in The Ten Commandments (1923), Mary, Queen of Scots in Dorothy Vernon of Haddon Hall (1924), and Lucrezia Borgia in Don Juan (1926).

Although she made a successful transition to sound films, she retired from film acting in 1932 and decided to focus entirely on her singing career. She was also active in animal welfare before her death from cancer in 1958. She was posthumously honored in 1960 with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in the motion pictures category.

Ida Estelle Taylor was born on May 20, 1894 in Wilmington, Delaware. Her father, Harry D. Taylor (born 1871), was born in Harrington, Delaware. Her mother, Ida LaBertha "Bertha" Barrett (November 29, 1874 – August 25, 1965), was born in Easton, Pennsylvania, and later worked as a freelance makeup artist. The Taylors had another daughter, Helen (May 19, 1898 – December 22, 1990), who also became an actress. According to the 1900 census, the family lived in a rented house at 805 Washington Street in Wilmington. In 1903, Ida LaBertha was granted a divorce from Harry on the ground of nonsupport; the following year, she married a cooper named Fred T. Krech.[9] Ida LaBertha's third husband was Harry J. Boylan, a vaudevillian.

Taylor was raised by her maternal grandparents, Charles Christopher Barrett and Ida Lauber Barrett. Charles Barrett ran a piano store in Wilmington, and Taylor studied piano. Her childhood ambition was to become a stage actress, but her grandparents initially disapproved of her theatrical aspirations. When she was ten years old she sang the role of "Buttercup" in a benefit performance of the opera H.M.S. Pinafore in Wilmington. She attended high school but dropped out because she refused to apologize after a troublesome classmate caused her to spill ink from her inkwell on the floor. In 1911, she married bank cashier Kenneth M. Peacock. The couple remained together for five years until Taylor decided to become an actress. She soon found work as an artists' model, posing for Howard Pyle, Harvey Dunn, Leslie Thrasher, and other painters and illustrators.

In April 1918, Taylor moved to New York City to study acting at the Sargent Dramatic School. She worked as a hat model for a wholesale millinery store to earn money for her tuition and living expenses. At Sargent Dramatic School, she wrote and performed one-act plays, studied voice inflection and diction, and was noticed by a singing teacher named Mr. Samoiloff who thought her voice was suitable for opera. Samoiloff gave Taylor singing lessons on a contingent basis and, within several months, recommended her to theatrical manager Henry Wilson Savage for a part in the musical Lady Billy. She auditioned for Savage and he offered her work as an understudy to the actress who had the second role in the musical. At the same time, playwright George V. Hobart offered her a role as a "comedy vamp" in his play Come-On, Charlie, and Taylor, who had no experience in stage musicals, preferred the non-musical role and accepted Hobart's offer.

Taylor made her Broadway stage début in George V. Hobart's Come-On, Charlie, which opened on April 8, 1919 at 48th Street Theatre in New York City. The story was about a shoe clerk who has a dream in which he inherits one million dollars and must make another million within six months. It was not a great success and closed after sixteen weeks. Taylor, the only person in the play who wore red beads, was praised by a New York City critic who wrote, "The only point of interest in the show was the girl with the red beads." During the play's run, producer Adolph Klauber saw Taylor's performance and said to the play's leading actress Aimee Lee Dennis: "You know, I think Miss Taylor should go into motion pictures. That's where her greatest future lies. Her dark eyes would screen excellently." Dennis told Taylor what Klauber said, and Taylor began looking for work in films. With the help of J. Gordon Edwards, she got a small role in the film A Broadway Saint (1919). She was hired by the Vitagraph Company for a role with Corinne Griffith in The Tower of Jewels (1920), and also played William Farnum's leading lady in The Adventurer (1920) for the Fox Film Corporation.

One of Taylor's early successes was in 1920 in Fox's While New York Sleeps with Marc McDermott. Charles Brabin directed the film, and Taylor and McDermott play three sets of characters in different time periods. This film was lost for decades, but has been recently discovered and screened at a film festival in Los Angeles. Her next film for Fox, Blind Wives (1920), was based on Edward Knoblock's play My Lady's Dress and reteamed her with director Brabin and co-star McDermott. William Fox then sent her to Fox Film's Hollywood studios to play a supporting role in a Tom Mix film. Just before she boarded the train for Hollywood, Brabin gave her some advice: "Don't think of supporting Mix in that play. Don't play in program pictures. Never play anything but specials. Mr. Fox is about to put on Monte Cristo. You should play the part of Mercedes. Concentrate on that role and when you get to Los Angeles, see that you play it."

Taylor traveled with her mother, her canary bird, and her bull terrier, Winkle. She was excited about playing Mercedes and reread Alexandre Dumas' The Count of Monte Cristo on the train. When she arrived in Hollywood, she reported to Fox Studios and introduced herself to director Emmett J. Flynn, who gave her a copy of the script, but warned her that he already had another actress in mind for the role. Flynn offered her another part in the film, but she insisted on playing Mercedes and after much conversation was cast in the role. John Gilbert played Edmond Dantès in the film, which was eventually titled Monte Cristo (1922). Taylor later said that she, "saw then that he [Gilbert] had every requisite of a splendid actor." The New York Herald critic wrote, "Miss Taylor was as effective in the revenge section of the film as she was in the first or love part of the screened play. Here is a class of face that can stand a close-up without becoming a mere speechless automaton."

Fox also cast her as Gilda Fontaine, a "vamp", in the 1922 remake of the 1915 Fox production A Fool There Was, the film that made Theda Bara a star. Robert E. Sherwood of Life magazine gave it a mixed review and observed: "Times and movies have changed materially since then [1915]. The vamp gave way to the baby vamp some years back, and the latter has now been superseded by the flapper. It was therefore a questionable move on Mr. Fox's part to produce a revised version of A Fool There Was in this advanced age." She played a Russian princess in the film Bavu (1923), a Universal Pictures production with Wallace Beery as the villain and Forrest Stanley as her leading ma

One of her most memorable roles is that of Miriam, the sister of Moses (portrayed by Theodore Roberts), in the biblical prologue of Cecil B. DeMille's The Ten Commandments (1923), one of the most successful films of the silent era. Her performance in the DeMille film was considered a great acting achievement. Taylor's younger sister, Helen, was hired by Sid Grauman to play Miriam in the Egyptian Theatre's onstage prologue to the film.

Despite being ill with arthritis, she won the supporting role of Mary, Queen of Scots in Dorothy Vernon of Haddon Hall (1924), starring Mary Pickford. "I've since wondered if my long illness did not, in some measure at least, make for realism in registering the suffering of the unhappy and tormented Scotch queen," she told a reporter in 1926.

She played Lucrezia Borgia in Don Juan (1926), Warner Bros.' first feature-length film with synchronized Vitaphone sound effects and musical soundtrack. The film also starred John Barrymore, Mary Astor and Warner Oland. Variety praised her characterization of Lucrezia: "The complete surprise is the performance of Estelle Taylor as Lucretia [sic] Borgia. Her Lucretia is a fine piece of work. She makes it sardonic in treatment, conveying precisely the woman Lucretia is presumed to have been."

She was to have co-starred in a film with Rudolph Valentino, but he died just before production was to begin. One of her last silent films was New York (1927), featuring Ricardo Cortez and Lois Wilson.

In 1928, she and husband Dempsey starred in a Broadway play titled The Big Fight, loosely based around Dempsey's boxing popularity, which ran for 31 performances at the Majestic Theatre.

She made a successful transition to sound films or "talkies." Her first sound film was the comical sketch Pusher in the Face (1929).

Notable sound films in which she appeared include Street Scene (1931), with Sylvia Sidney; the Academy Award for Best Picture-winning Cimarron (1931), with Richard Dix and Irene Dunne; and Call Her Savage (1932), with Clara Bow.

Taylor returned to films in 1944 with a small part in the Jean Renoir drama The Southerner (released in 1945), playing what journalist Erskine Johnson described as "a bar fly with a roving eye. There's a big brawl and she starts throwing beer bottles." Johnson was delighted with Taylor's reappearance in the film industry: "[Interviewing] Estelle was a pleasant surprise. The lady is as beautiful and as vivacious as ever, with the curves still in the right places." The Southerner was her last film.

Taylor married three times, but never had children. In 1911 at aged 17, she married a bank cashier named Kenneth Malcolm Peacock, the son of a prominent Wilmington businessman. They lived together for five years and then separated so she could pursue her acting career in New York. Taylor later claimed the marriage was annulled. In August 1924, the press mentioned Taylor's engagement to boxer and world heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey. In September, Peacock announced he would sue Taylor for divorce on the ground of desertion. He denied he would name Dempsey as co-respondent, saying "If she wants to marry Dempsey, it is all right with me." Taylor was granted a divorce from Peacock on January 9, 1925.

Taylor and Dempsey were married on February 7, 1925 at First Presbyterian Church in San Diego, California. They lived in Los Feliz, Los Angeles. Her marriage to Dempsey ended in divorce in 1931.

Her third husband was theatrical producer Paul Small. Of her last husband and their marriage, she said: "We have been friends and Paul has managed my stage career for five years, so it seemed logical that marriage should work out for us, but I'm afraid I'll have to say that the reason it has not worked out is incompatibility."

In her later years, Taylor devoted her free time to her pets and was known for her work as an animal rights activist. "Whenever the subject of compulsory rabies inoculation or vivisection came up," wrote the United Press, "Miss Taylor was always in the fore to lead the battle against the measure." She was the president and founder of the California Pet Owners' Protective League, an organization that focused on finding homes for pets to prevent them from going to local animal shelters. In 1953, Taylor was appointed to the Los Angeles City Animal Regulation Commission, which she served as vice president.

Taylor died of cancer at her home in Los Angeles on April 15, 1958, at the age of 63. The Los Angeles City Council adjourned that same day "out of respect to her memory." Ex-husband Jack Dempsey said, "I'm very sorry to hear of her death. I didn't know she was that ill. We hadn't seen each other for about 10 years. She was a wonderful person." Her funeral was held on April 17 in Pierce Bros. Hollywood Chapel. She was interred at Hollywood Forever Cemetery, then known as Hollywood Memorial Park Cemetery.

She was survived by her mother, Ida "Bertha" Barrett Boylan; her sister, Helen Taylor Clark; and a niece, Frances Iblings. She left an estate of more than $10,000, most of it to her family and $200 for the care and maintenance of her three dogs, which she left to her friend Ella Mae Abrams.

Taylor was known for her dark features and for the sensuality she brought to the films in which she appeared. Journalist Erskine Johnson considered her "the screen's No. 1 oomph girl of the 20s." For her contribution to the motion picture industry, Estelle Taylor was awarded a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 1620 Vine Street in Hollywood, California.

#estelle taylor#silent era#silent hollywood#silent movie stars#golden age of hollywood#classic movie stars#1920s hollywood#1930s hollywood#1940s hollywood

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Want to learn more about an artist in our collection? Download our Ask Brooklyn Museum app and chat with one of our experts! 💬

Kenojuak Ashevak (Inuit, 1927-2013). The Enchanted Owl, 1960. Stone cut on paper. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of George Klauber, 1998.122. © artist or artist's estate

#askbkm#bkmartsofamericas#brooklyn museum#app#technology#museums#Kenojuak Ashevak#inuit#art#artist#arts of the americas#owl#print#stune cut

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ida Estelle Taylor (May 20, 1894 – April 15, 1958) was an American actress, singer, model, and animal rights activist. With "dark-brown, almost black hair and brown eyes," she was regarded as one of the most beautiful silent film stars of the 1920s.

After her stage debut in 1919, Taylor began appearing in small roles in World and Vitagraph films. She achieved her first notable success with While New York Sleeps (1920), in which she played three different roles, including a "vamp." She was a contract player of Fox Film Corporation and, later, Paramount Pictures, but for the most part of her career she freelanced. She became famous and was commended by critics for her portrayals of historical women in important films: Miriam in The Ten Commandments (1923), Mary, Queen of Scots in Dorothy Vernon of Haddon Hall (1924), and Lucrezia Borgia in Don Juan (1926).

Although she made a successful transition to sound films, she retired from film acting in 1932 and decided to focus entirely on her singing career. She was also active in animal welfare before her death from cancer in 1958. She was posthumously honored in 1960 with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in the motion pictures category.

Ida Estelle Taylor was born on May 20, 1894 in Wilmington, Delaware. Her father, Harry D. Taylor (born 1871), was born in Harrington, Delaware.[8] Her mother, Ida LaBertha "Bertha" Barrett (November 29, 1874 – August 25, 1965), was born in Easton, Pennsylvania, and later worked as a freelance makeup artist. The Taylors had another daughter, Helen (May 19, 1898 – December 22, 1990), who also became an actress. According to the 1900 census, the family lived in a rented house at 805 Washington Street in Wilmington In 1903, Ida LaBertha was granted a divorce from Harry on the ground of nonsupport; the following year, she married a cooper named Fred T. Krech. Ida LaBertha's third husband was Harry J. Boylan, a vaudevillian.

Taylor was raised by her maternal grandparents, Charles Christopher Barrett and Ida Lauber Barrett. Charles Barrett ran a piano store in Wilmington, and Taylor studied piano. Her childhood ambition was to become a stage actress, but her grandparents initially disapproved of her theatrical aspirations. When she was ten years old she sang the role of "Buttercup" in a benefit performance of the opera H.M.S. Pinafore in Wilmington. She attended high school[6] but dropped out because she refused to apologize after a troublesome classmate caused her to spill ink from her inkwell on the floor. In 1911, she married bank cashier Kenneth M. Peacock. The couple remained together for five years until Taylor decided to become an actress. She soon found work as an artists' model, posing for Howard Pyle, Harvey Dunn, Leslie Thrasher, and other painters and illustrators.

In April 1918, Taylor moved to New York City to study acting at the Sargent Dramatic School. She worked as a hat model for a wholesale millinery store to earn money for her tuition and living expenses. At Sargent Dramatic School, she wrote and performed one-act plays, studied voice inflection and diction, and was noticed by a singing teacher named Mr. Samoiloff who thought her voice was suitable for opera. Samoiloff gave Taylor singing lessons on a contingent basis and, within several months, recommended her to theatrical manager Henry Wilson Savage for a part in the musical Lady Billy. She auditioned for Savage and he offered her work as an understudy to the actress who had the second role in the musical. At the same time, playwright George V. Hobart offered her a role as a "comedy vamp" in his play Come-On, Charlie, and Taylor, who had no experience in stage musicals, preferred the non-musical role and accepted Hobart's offer.

Taylor made her Broadway stage début in George V. Hobart's Come-On, Charlie, which opened on April 8, 1919 at 48th Street Theatre in New York City. The story was about a shoe clerk who has a dream in which he inherits one million dollars and must make another million within six months. It was not a great success and closed after sixteen weeks. Taylor, the only person in the play who wore red beads, was praised by a New York City critic who wrote, "The only point of interest in the show was the girl with the red beads." During the play's run, producer Adolph Klauber saw Taylor's performance and said to the play's leading actress Aimee Lee Dennis: "You know, I think Miss Taylor should go into motion pictures. That's where her greatest future lies. Her dark eyes would screen excellently." Dennis told Taylor what Klauber said, and Taylor began looking for work in films. With the help of J. Gordon Edwards, she got a small role in the film A Broadway Saint (1919).nShe was hired by the Vitagraph Company for a role with Corinne Griffith in The Tower of Jewels (1920), and also played William Farnum's leading lady in The Adventurer (1920) for the Fox Film Corporation.

One of Taylor's early successes was in 1920 in Fox's While New York Sleeps with Marc McDermott. Charles Brabin directed the film, and Taylor and McDermott play three sets of characters in different time periods. This film was lost for decades, but has been recently discovered and screened at a film festival in Los Angeles. Her next film for Fox, Blind Wives (1920), was based on Edward Knoblock's play My Lady's Dress and reteamed her with director Brabin and co-star McDermott. William Fox then sent her to Fox Film's Hollywood studios to play a supporting role in a Tom Mix film. Just before she boarded the train for Hollywood, Brabin gave her some advice: "Don't think of supporting Mix in that play. Don't play in program pictures. Never play anything but specials. Mr. Fox is about to put on Monte Cristo. You should play the part of Mercedes. Concentrate on that role and when you get to Los Angeles, see that you play it."

Taylor traveled with her mother, her canary bird, and her bull terrier, Winkle. She was excited about playing Mercedes and reread Alexandre Dumas' The Count of Monte Cristo on the train. When she arrived in Hollywood, she reported to the Fox studios and introduced herself to director Emmett J. Flynn, who gave her a copy of the script but warned her that he already had another actress in mind for the role. Flynn offered her another part in the film, but she insisted on playing Mercedes and after much conversation was cast in the role. John Gilbert played Edmond Dantès in the film, which was eventually titled Monte Cristo (1922). Taylor later said that she "saw then that he [Gilbert] had every requisite of a splendid actor." The New York Herald critic wrote "Miss Taylor was as effective in the revenge section of the film as she was in the first or love part of the screened play. Here is a class of face that can stand a close-up without becoming a mere speechless automaton."

Fox also cast her as Gilda Fontaine, a "vamp", in the 1922 remake of the 1915 Fox production A Fool There Was, the film that made Theda Bara a star. Robert E. Sherwood of Life magazine gave it a mixed review and observed: "Times and movies have changed materially since then [1915]. The vamp gave way to the baby vamp some years back, and the latter has now been superseded by the flapper. It was therefore a questionable move on Mr. Fox's part to produce a revised version of A Fool There Was in this advanced age." She played a Russian princess in the film Bavu (1923), a Universal Pictures production with Wallace Beery as the villain and Forrest Stanley as her leading man.

One of her most memorable roles is that of Miriam, the sister of Moses (portrayed by Theodore Roberts), in the biblical prologue of Cecil B. DeMille's The Ten Commandments (1923), one of the most successful films of the silent era. Her performance in the DeMille film was considered a great acting achievement. Taylor's younger sister, Helen, was hired by Sid Grauman to play Miriam in the Egyptian Theatre's onstage prologue to the film.

Despite being ill with arthritis, she won the supporting role of Mary, Queen of Scots in Dorothy Vernon of Haddon Hall (1924), starring Mary Pickford. "I've since wondered if my long illness did not, in some measure at least, make for realism in registering the suffering of the unhappy and tormented Scotch queen," she told a reporter in 1926.

She played Lucrezia Borgia in Don Juan (1926), Warner Bros.' first feature-length film with synchronized Vitaphone sound effects and musical soundtrack. The film also starred John Barrymore, Mary Astor and Warner Oland. Variety praised her characterization of Lucrezia: "The complete surprise is the performance of Estelle Taylor as Lucretia [sic] Borgia. Her Lucretia is a fine piece of work. She makes it sardonic in treatment, conveying precisely the woman Lucretia is presumed to have been."

She was to have co-starred in a film with Rudolph Valentino, but he died just before production was to begin. One of her last silent films was New York (1927), featuring Ricardo Cortez and Lois Wilson.

In 1928, she and husband Dempsey starred in a Broadway play titled The Big Fight, loosely based around Dempsey's boxing popularity, which ran for 31 performances at the Majestic Theatre.

She made a successful transition to sound films or "talkies." Her first sound film was the comical sketch Pusher in the Face (1929).

Notable sound films in which she appeared include Street Scene (1931), with Sylvia Sidney; the Academy Award for Best Picture-winning Cimarron (1931), with Richard Dix and Irene Dunne; and Call Her Savage (1932), with Clara Bow.

Taylor returned to films in 1944 with a small part in the Jean Renoir drama The Southerner (released in 1945), playing what journalist Erskine Johnson described as "a bar fly with a roving eye. There's a big brawl and she starts throwing beer bottles." Johnson was delighted with Taylor's reappearance in the film industry: "[Interviewing] Estelle was a pleasant surprise. The lady is as beautiful and as vivacious as ever, with the curves still in the right places." The Southerner was her last film.

Taylor married three times, but never had children. In 1911 at aged 17, she married a bank cashier named Kenneth Malcolm Peacock, the son of a prominent Wilmington businessman. They lived together for five years and then separated so she could pursue her acting career in New York. Taylor later claimed the marriage was annulled. In August 1924, the press mentioned Taylor's engagement to boxer and world heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey.[36] In September, Peacock announced he would sue Taylor for divorce on the ground of desertion. He denied he would name Dempsey as co-respondent, saying "If she wants to marry Dempsey, it is all right with me." Taylor was granted a divorce from Peacock on January 9, 1925.

Taylor and Dempsey were married on February 7, 1925 at First Presbyterian Church in San Diego, California. They lived in Los Feliz, Los Angeles. Her marriage to Dempsey ended in divorce in 1931.

Her third husband was theatrical producer Paul Small. Of her last husband and their marriage, she said: "We have been friends and Paul has managed my stage career for five years, so it seemed logical that marriage should work out for us, but I'm afraid I'll have to say that the reason it has not worked out is incompatibility."

In her later years, Taylor devoted her free time to her pets and was known for her work as an animal rights activist. "Whenever the subject of compulsory rabies inoculation or vivisection came up," wrote the United Press, "Miss Taylor was always in the fore to lead the battle against the measure." She was the president and founder of the California Pet Owners' Protective League, an organization that focused on finding homes for pets to prevent them from going to local animal shelters. In 1953, Taylor was appointed to the Los Angeles City Animal Regulation Commission, which she served as vice president.

Taylor died of cancer at her home in Los Angeles on April 15, 1958, at the age of 63. The Los Angeles City Council adjourned that same day "out of respect to her memory." Ex-husband Jack Dempsey said, "I'm very sorry to hear of her death. I didn't know she was that ill. We hadn't seen each other for about 10 years. She was a wonderful person." Her funeral was held on April 17 in Pierce Bros. Hollywood Chapel. She was interred at Hollywood Forever Cemetery, then known as Hollywood Memorial Park Cemetery.

She was survived by her mother, Ida "Bertha" Barrett Boylan; her sister, Helen Taylor Clark; and a niece, Frances Iblings. She left an estate of more than $10,000, most of it to her family and $200 for the care and maintenance of her three dogs, which she left to friend Ella Mae Abrams.

Taylor was known for her dark features and for the sensuality she brought to the films in which she appeared. Journalist Erskine Johnson considered her "the screen's No. 1 oomph girl of the 20s." For her contribution to the motion picture industry, Estelle Taylor was awarded a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 1620 Vine Street in Hollywood, California.

#estelle taylor#classic hollywood#golden age of hollywood#classic movie stars#classic cinema#old hollywood#classic movies#silent era#silent stars#silent cinema

0 notes

Link

For just $3.99 Carnival Story Released April 16, 1954: A carnival that failed in the U.S. travels to Munich, Germany to see if the Germans will like the corny carnival acts any better than the U.S. did. Directed by: Kurt Neumann Written by: Hans Jacoby, Charles Williams, Marcy Klauber and Kurt Neumann The Actors: Anne Baxter Willie, Steve Cochran Joe Hammond, Lyle Bettger Frank Colloni, George Nader Bill Vines, Jay C. Flippen Charley Grayson, Helene Stanley Peggy, Ady Berber Groppo Runtime: 1h 35m *** This item will be supplied on a quality disc and will be sent in a sleeve that is designed for posting CD's DVDs *** This item will be sent by 1st class post for quick delivery. Should you not receive your item within 12 working days of making payment, please contact us as it is unusual for any item to take this long to be delivered. Note: All my products are either my own work, licensed to me directly or supplied to me under a GPL/GNU License. No Trademarks, copyrights or rules have been violated by this item. This product complies withs rules on compilations, international media and downloadable media. All items are supplied on CD or DVD. On Dec-13-16 at 14:29:07 PST, seller added the following information:

0 notes

Photo

ANDY WARHOL’S FIRST WORK IN A MUSEUM

The image I’m posting today, apparently unknown even to most experts, turns out to be the very first work by Andy Warhol ever to be shown in a museum. (Apologies for the watermarked jpeg; it was the only one I could find.)

I came across the painting last week when I reached out to the Addison Gallery, at the Phillips Academy in Massachusetts, in search of some quite different information about the contents of a show called “Art Schools, U.S.A.” that the Addison mounted in the summer of 1948 and then toured across the country. Despite our corona-virus lockdown, Addison curator Gordon Wilkins graciously answered my query, quoting a gallery publication from 1996 that mentioned a few of the 110 student artists included in the show, ending with the following phrase: ��And from the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh, Hayes had chosen a painting called Everywhere I Look This Is What I See by one Andrew Warhola” — a.k.a., of course, Andy Warhol.

Warhol had just finished his junior year of college when he won this honor. The full exhibition checklist shows him sharing it with six other Tech classmates including his close friend Art Elias and also George Klauber, an older student who went on to launch Warhol into both his gay life and commercial career in New York.

Warhol had had at least one hit of public exposure before the Addison show: A few months before being chosen for “Art Schools, U.S.A.,” he was included in a group show mounted by the Associated Artists of Pittsburgh. But that was a purely local organization with no home of its own, and couldn’t compare to the prestigious Addison Gallery, which had notable holdings of important American art and was known for collecting and showing all the latest trends. Its director had been covered in the Pittsburgh press as one of the curators of the major exhibition called “Painting in the United States” that happened annually at the Carnegie Institute’s art museum.

Warhol’s pleasure at being shown at the Addison must have been tempered by the fact that his work wasn’t included in the version of the exhibition that toured nationally, and got national coverage. But it’s not clear his piece deserved more attention than it got. It’s still distinctly awkward student work, of no particular distinction beyond the strong if generic nod it gives to modern avant-gardism—which, in the Pittsburgh context, would have still given it some appreciable edge. (A local critic had bashed Warhol’s instructors for their modernist contributions to the same AAP show he was in.) Despite the figures in Warhol’s painting, it would have counted as daringly “abstract,” as the word was used in his hometown.

The one thing that strikes me as truly notable in the work is its title, which just about begs for some kind of allegorical reading. What is it that Warhol, the art student, sees whenever he looks around? Given what we know about his nascent gay identity at this moment, I can’t help feeling that what he sees are people who are desperately busy looking down at the floor, up at the ceiling, into their armpits — anywhere but at him as he stands proudly, serenely before them.

Following its display at the Addison, the painting seems to have gone missing—buried in Warhol’s attic, perhaps, or some relative’s garage—until it went up for auction at Christie’s, New York, on February 23, 1990, just three years and one day after Warhol's death. It sold for $26,400, and might go for far more than that now—but even I have to admit that that would be because of the signature on the painting’s back, not the image on its front. (Artwork © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.)

1 note

·

View note

Text

By Michael Good

Let’s rethink the historic designation process by populating architectural homes with historical homeowners

For better or worse, California’s Mills Act has come to define what it means for a house to be historic in San Diego.

A house can qualify based on a number of criteria but, basically, historians are looking for a “yes” to any one of four questions: Is the architect or builder a recognized master? Is the house a significant part of an already designated historic neighborhood? Does the house represent an outstanding example of a recognized house type or style? Was a former resident a historic figure?

It’s the answer to that last question that most people associate with historic houses — in the popular imagination it’s not enough that a house is architecturally significant. People want to know that something historical happened there — and that it happened to an historical person. George Washington was born there. George Washington slept there. George Washington had a beer, had an argument, made a plan, started a revolution, told a lie, chopped down a tree, danced with his wife, danced with John Adams’s wife. Something. But in reality, very, very rarely in San Diego is a house declared historic because of a former resident.

The reason is simple: There are no established criteria for what makes a person historic in San Diego. For the builder, there is a list. Getting on that list is the result of a steady drip, drip, drip of evidence. It’s like a court case where circumstantial evidence piles up until the verdict is inescapable: The builder was responsible for five houses in an historic neighborhood; six more of his houses in other neighborhoods are excellent examples of Spanish Eclectic architecture; he apprenticed with Richard Requa; he partnered with master builder Carl B. Hays; he built more than 100 houses in Mission Hills, North Park, South Park and Kensington. The evidence mounts. Eventually there’s a tipping point, and the builder gets added to the all-important list of master builders.

But there’s no list for historic homeowners. And it doesn’t really make sense to have one, since this historic house process starts with, well, a house. What we need is a framework for establishing whether a person — not a house — deserves historic designation. Here are my suggestions:

Anyone who had anything to do with the 1915 Panama California Exposition. The 1915 Expo is the biggest thing San Diegans have ever agreed to do together. And this is a city that has a hard time agreeing on anything. Airports, stadiums, football teams, how thoroughly to sanitize our sewage. But pretty much the entire city agreed on the Expo — and attended it.

Admittedly, “anyone who had anything to do with” is a pretty wide net. But a good place to start is with the 100 or so tuxedo-clad fellows who attended the epic dinner party where the plan was hatched. (The guest list was printed in the newspaper, so we know who was there.) The principal architects of the Expo — Goodhue, Davidson, Collier, Spreckels, etc. — deserve a nod, of course, as do the movers and shakers listed in Richard Amero’s book on the Exposition.

Political figures. Let’s at least start with the mayor. A president or two would be nice. A governor perhaps. But if a sitting mayor conducts business in his home, from his bedroom, while propped up in bed, really, that should be enough to designate the house as historic. (It wasn’t, however, in a case from a couple years ago.)

Industry leaders. Particularly industries that have shaped our city: The military. Fishing. Airplane manufacturing. Aerospace. Telecom. Bioscience. Education.

Those who lived in infamy. History is not always pretty. How society actually works becomes clear when someone screws up. The backroom deals only become apparent when someone gets caught. San Diego has had its share of scandals. And we’ve usually had the press to record them. And Genealogy Bank to look them up. And Ancestry.com to check if the woman our infamous historical figure took that cruise to Hawaii with was really his wife.

Hidden figures. In recent months I’ve written about women builders, architects and designers. Some, such as Louise Severin, were for many years all but ignored by history (and the Historic Resources Board). Others, such as Alice Klauber, seemed to court anonymity. Klauber’s behind-the-scenes negotiations to get women accommodated at the 1915 Expo weren’t widely reported at the time. Her decorations for the women’s building were. She was too well-mannered to require recognition. People of African, Mexican, Chinese, Japanese and Native American descent were also often overlooked by history. It’s not that they weren’t out there doing stuff, it’s that polite society wasn’t there to record it.

Trendsetters. We recognize the architects who were on the cutting edge of fashion — for example, the first to bring arts and crafts to San Diego. We should recognize people who set social trends as well. Not just the first woman president of a college, but the first woman president to wear a pantsuit, flash the peace sign, join a commune and retire to raise alpacas on Mt. Woodson. And lets not forget the first guy to mount skateboard wheels to a flexible board, the first San Diegan to ride a redwood surfboard, and Ted Williams, the first Major League ballplayer to emerge from the shadow of the water tower, who became a great ballplayer because he happened to live across the street from a baseball diamond in North Park (and why isn’t that house designated?).

People who built houses, but weren’t master builders. The carpenters who designed and built the built-ins. The stained glass artists, the tile designers, the guy (still unidentified) who designed the pyrographic, art deco style front doors for Spanish houses in 1929 and 1930. We already recognize the master builders. Let’s celebrate the master plasterer who could make stucco look like stone and the master painter who rag-rolled ceilings to look like clouds at sunset.

Establishing historic significance for residents should be no different than determining master status for builders: It would require the steady accumulation of evidence. Being the mayor is good. Being a civil engineer as well as mayor is better. Designing a magnificent suspension footbridge that has stood the test of time would seal the deal, as it should for Mayor and City Engineer Edwin Capps, who designed the Spruce Street Suspension Bridge. (Having a street named after you doesn’t hurt either. Capps even dipped his toe in a juicy, or at least damp, scandal: he hired rainmaker Charles Hatfield in 1915.)

Let’s consider another mayor, Enrique Aldrete, who was the president of the municipality of Tijuana at the time of the Mexican Revolution in 1913 and 1914, Mexican Consul in San Ysidro after that, and secretary of the Baja government prior to those two appointments. In 1929, Aldrete moved to a house on Marlborough in Kensington that was recently designated historic by the HRB (but not because of its first owner).

The Enrique and Esperanza Aldrete house during restoration, in 2015, master builder Carl. B Hays. (Photo by Michael Good)

Aldrete later wrote a book about his experiences during the revolution. He was also a custom broker, had an early version of a department store (Cinco de Mayo) in Tijuana, operated a store on this side of the border as well, and was, with his brother Alberto and Miguel Gonzalez, among the first Mexicans to live in North Park (he and his brother also lived in South Park and then moved with their families to Kensington in the late 1920s — during a time when many neighborhoods had deed restrictions designed to keep Mexicans out.

His family owned land in the center of Tijuana (which became the country club), he was the president of Tijuana Chamber of Commerce, and the Aldretes were among the oldest and most established families in northern Baja. He was related by marriage to the Estudillo family, one of the oldest in San Diego (their house in Old Town is now a historic museum). Aldrete was also friendly with mayors, governors and presidents. Two Mexican presidents, when they retired, moved to Kensington, presumably because the Aldretes lived there. (President Abelardo Rodriquez purchased his brother Alberto’s house.) Enrique could cross the border without papers, because the agents knew him by name (this according to a border agent’s notes on Aldrete’s crossing card).

Enrique Aldrete

So … Enrique Aldrete. Trendsetter, check. Major politician, check. Hidden figure, check. (In fact, he had been pretty much forgotten on this side of the border until the current owners of his Marlborough house looked him up at the San Diego History Center’s research library.) Aldrete was also a business leader; he was a founder of the Tijuana Chamber of Commerce and the Tijuana Country Club. Online I found an account by his daughter Carmen, on the occasion of her 100th birthday in 1913, remembering fondly Jefferson Elementary in North Park, which she attended, and the house on Marlborough, where she lived as a young woman. She also recalled how when she and her father crossed the border, everyone on both sides, Mexican and U.S. agents alike, greeted him by name.

Like a slowly dripping faucet, the evidence accumulates and pretty soon it just seems reasonable and prudent to stop fighting it and accept that Enrique Aldrete is a historic person. In fact, he represents someone who can’t exist today: a binational businessman and politician who could freely cross the border and exist with feet planted in both countries. Rather than look for reasons why he can’t be considered historic (such as the claim that his biggest accomplishments were on the other side of the border) we should consider how he represents a historic type that has long gone unrecognized, a member of the Mexican aristocracy that provides a bridge between the California of the Dons and the California of the dot-coms, between Mexican Territorial-era San Diego and 21st-century San Diego in the age of the Great Big Beautiful Wall.

We don’t know where the future will take us but we do have the opportunity to discover where we’ve been — and to find, perhaps, a clue to our future.

—Contact Michael Good at [email protected].

The post A modest proposal appeared first on San Diego Uptown News.

#gallery-0-6 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-6 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 33%; } #gallery-0-6 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-6 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

Conor Chinn

La Jolla Cave

Demographics of La Jolla

Community Groups La Jolla

Landmarks in La Jolla

Rolf Benirschke

Gerry Driscoll

Dick Enberg

Doug Flutie

J. J. Isler

Gene Littler

Rey Mysterio

Bob Skinner

Joel Skinner

Craig Stadler

Alexandra Stevenson

Lou Thesz

John Michels

Izetta Jewel Miller

Religious Institutions in La Jolla

Beach Barber Tract

Beach Barber La Jolla High School

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

San Diego Short Sale Real Estate Investing

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Rehabbing San Diego Real Estate

Rehabbing San Diego Real Estate

Rehabbing San Diego Real Estate

Rehabbing San Diego Real Estate

Rehabbing San Diego Real Estate

Rehabbing San Diego Real Estate

seven bridge walk

bridge balboa park

bridge balboa park walk

balboa park bridge

banker hill walk

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Missing Attachment

Mission Valley Carjacking at Promenade

p-89EKCgBk8MZdE

Original Article Provided By: SDUptownNews.com A modest proposal By Michael Good Let’s rethink the historic designation process by populating architectural homes with historical homeowners…

0 notes

Photo

Andy Warhol photographed by George Klauber, 1951

757 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Kitchen (1961)

"You have to make me care? In forty years, suddenly, you have to make me care? You? You? Who are you? Tell me, in all this big world, who are you, for God's sake?"

#the kitchen#arnold wesker#british cinema#kitchen sink drama#modern drama#1961#films i done watched#carl möhner#mary yeomans#eric pohlmann#brian phelan#tom bell#charles lloyd pack#scott finch#gertan klauber#martin boddey#frank pettitt#rosalind knight#george eugeniou#sean lynch#josef behrmann#james hill#this presumably looked to be a sure fire hit in 1961. with room at the top and look back in anger both having made the kitchen#sink drama a viable money maker. the kitchen had been a notable stage success too thanks to its show stopping lunch time rush scene#that aspect translates well to this film. its a hectic hellish ballet of plates and pans and steam. i worked in a kitchen years ago and god#i wouldn't do it again. but this felt very real. otherwise tho it misses some of the intimacy of wesker's play. the brief scenes of a walk#around london are unnecessary and in some ways kill the film dead for a few moments. but there are things that do work. the ensemble cast#are all brilliant. pohl is weariness personified and a very young tom bell shines in his one big scene in which he describes the horror of#his fellow man (he's playing wesker's self insert too). for whatever reason this wasn't the success that those other dramas were#and while his work would still be adapted for television to the best of my knowledge nobody has attempted a film of weskers work since

0 notes

Photo

Korea: The Limited War (1964, cover design by George Klauber)

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Self Portrait/Portrait of George Klauber, Philip Pearlstein, 1948-1949, Brooklyn Museum: Contemporary Art

© Philip Pearlstein

Size: 25 x 18 x 1/4 in. (63.5 x 45.7 x 0.6 cm) frame: 31 15/16 x 24 7/16 x 4 7/8 in. (81.2 x 62 x 12.4 cm)

Medium: Casein on masonite

https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/168771

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ida Estelle Taylor (May 20, 1894 – April 15, 1958) was an American actress, singer, model, and animal rights activist. With "dark-brown, almost black hair and brown eyes," she was regarded as one of the most beautiful silent film stars of the 1920s.

After her stage debut in 1919, Taylor began appearing in small roles in World and Vitagraph films. She achieved her first notable success with While New York Sleeps (1920), in which she played three different roles, including a "vamp." She was a contract player of Fox Film Corporation and, later, Paramount Pictures, but for the most part of her career she freelanced. She became famous and was commended by critics for her portrayals of historical women in important films: Miriam in The Ten Commandments (1923), Mary, Queen of Scots in Dorothy Vernon of Haddon Hall (1924), and Lucrezia Borgia in Don Juan (1926).

Although she made a successful transition to sound films, she retired from film acting in 1932 and decided to focus entirely on her singing career. She was also active in animal welfare before her death from cancer in 1958. She was posthumously honored in 1960 with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in the motion pictures category.

Ida Estelle Taylor was born on May 20, 1894 in Wilmington, Delaware. Her father, Harry D. Taylor (born 1871), was born in Harrington, Delaware.[8] Her mother, Ida LaBertha "Bertha" Barrett (November 29, 1874 – August 25, 1965), was born in Easton, Pennsylvania, and later worked as a freelance makeup artist. The Taylors had another daughter, Helen (May 19, 1898 – December 22, 1990), who also became an actress. According to the 1900 census, the family lived in a rented house at 805 Washington Street in Wilmington In 1903, Ida LaBertha was granted a divorce from Harry on the ground of nonsupport; the following year, she married a cooper named Fred T. Krech. Ida LaBertha's third husband was Harry J. Boylan, a vaudevillian.

Taylor was raised by her maternal grandparents, Charles Christopher Barrett and Ida Lauber Barrett. Charles Barrett ran a piano store in Wilmington, and Taylor studied piano. Her childhood ambition was to become a stage actress, but her grandparents initially disapproved of her theatrical aspirations. When she was ten years old she sang the role of "Buttercup" in a benefit performance of the opera H.M.S. Pinafore in Wilmington. She attended high school[6] but dropped out because she refused to apologize after a troublesome classmate caused her to spill ink from her inkwell on the floor. In 1911, she married bank cashier Kenneth M. Peacock. The couple remained together for five years until Taylor decided to become an actress. She soon found work as an artists' model, posing for Howard Pyle, Harvey Dunn, Leslie Thrasher, and other painters and illustrators.

In April 1918, Taylor moved to New York City to study acting at the Sargent Dramatic School. She worked as a hat model for a wholesale millinery store to earn money for her tuition and living expenses. At Sargent Dramatic School, she wrote and performed one-act plays, studied voice inflection and diction, and was noticed by a singing teacher named Mr. Samoiloff who thought her voice was suitable for opera. Samoiloff gave Taylor singing lessons on a contingent basis and, within several months, recommended her to theatrical manager Henry Wilson Savage for a part in the musical Lady Billy. She auditioned for Savage and he offered her work as an understudy to the actress who had the second role in the musical. At the same time, playwright George V. Hobart offered her a role as a "comedy vamp" in his play Come-On, Charlie, and Taylor, who had no experience in stage musicals, preferred the non-musical role and accepted Hobart's offer.

Taylor made her Broadway stage début in George V. Hobart's Come-On, Charlie, which opened on April 8, 1919 at 48th Street Theatre in New York City. The story was about a shoe clerk who has a dream in which he inherits one million dollars and must make another million within six months. It was not a great success and closed after sixteen weeks. Taylor, the only person in the play who wore red beads, was praised by a New York City critic who wrote, "The only point of interest in the show was the girl with the red beads." During the play's run, producer Adolph Klauber saw Taylor's performance and said to the play's leading actress Aimee Lee Dennis: "You know, I think Miss Taylor should go into motion pictures. That's where her greatest future lies. Her dark eyes would screen excellently." Dennis told Taylor what Klauber said, and Taylor began looking for work in films. With the help of J. Gordon Edwards, she got a small role in the film A Broadway Saint (1919).nShe was hired by the Vitagraph Company for a role with Corinne Griffith in The Tower of Jewels (1920), and also played William Farnum's leading lady in The Adventurer (1920) for the Fox Film Corporation.

One of Taylor's early successes was in 1920 in Fox's While New York Sleeps with Marc McDermott. Charles Brabin directed the film, and Taylor and McDermott play three sets of characters in different time periods. This film was lost for decades, but has been recently discovered and screened at a film festival in Los Angeles. Her next film for Fox, Blind Wives (1920), was based on Edward Knoblock's play My Lady's Dress and reteamed her with director Brabin and co-star McDermott. William Fox then sent her to Fox Film's Hollywood studios to play a supporting role in a Tom Mix film. Just before she boarded the train for Hollywood, Brabin gave her some advice: "Don't think of supporting Mix in that play. Don't play in program pictures. Never play anything but specials. Mr. Fox is about to put on Monte Cristo. You should play the part of Mercedes. Concentrate on that role and when you get to Los Angeles, see that you play it."

Taylor traveled with her mother, her canary bird, and her bull terrier, Winkle. She was excited about playing Mercedes and reread Alexandre Dumas' The Count of Monte Cristo on the train. When she arrived in Hollywood, she reported to the Fox studios and introduced herself to director Emmett J. Flynn, who gave her a copy of the script but warned her that he already had another actress in mind for the role. Flynn offered her another part in the film, but she insisted on playing Mercedes and after much conversation was cast in the role. John Gilbert played Edmond Dantès in the film, which was eventually titled Monte Cristo (1922). Taylor later said that she "saw then that he [Gilbert] had every requisite of a splendid actor." The New York Herald critic wrote "Miss Taylor was as effective in the revenge section of the film as she was in the first or love part of the screened play. Here is a class of face that can stand a close-up without becoming a mere speechless automaton."

Fox also cast her as Gilda Fontaine, a "vamp", in the 1922 remake of the 1915 Fox production A Fool There Was, the film that made Theda Bara a star. Robert E. Sherwood of Life magazine gave it a mixed review and observed: "Times and movies have changed materially since then [1915]. The vamp gave way to the baby vamp some years back, and the latter has now been superseded by the flapper. It was therefore a questionable move on Mr. Fox's part to produce a revised version of A Fool There Was in this advanced age." She played a Russian princess in the film Bavu (1923), a Universal Pictures production with Wallace Beery as the villain and Forrest Stanley as her leading man.

One of her most memorable roles is that of Miriam, the sister of Moses (portrayed by Theodore Roberts), in the biblical prologue of Cecil B. DeMille's The Ten Commandments (1923), one of the most successful films of the silent era. Her performance in the DeMille film was considered a great acting achievement. Taylor's younger sister, Helen, was hired by Sid Grauman to play Miriam in the Egyptian Theatre's onstage prologue to the film.

Despite being ill with arthritis, she won the supporting role of Mary, Queen of Scots in Dorothy Vernon of Haddon Hall (1924), starring Mary Pickford. "I've since wondered if my long illness did not, in some measure at least, make for realism in registering the suffering of the unhappy and tormented Scotch queen," she told a reporter in 1926.

She played Lucrezia Borgia in Don Juan (1926), Warner Bros.' first feature-length film with synchronized Vitaphone sound effects and musical soundtrack. The film also starred John Barrymore, Mary Astor and Warner Oland. Variety praised her characterization of Lucrezia: "The complete surprise is the performance of Estelle Taylor as Lucretia [sic] Borgia. Her Lucretia is a fine piece of work. She makes it sardonic in treatment, conveying precisely the woman Lucretia is presumed to have been."

She was to have co-starred in a film with Rudolph Valentino, but he died just before production was to begin. One of her last silent films was New York (1927), featuring Ricardo Cortez and Lois Wilson.

In 1928, she and husband Dempsey starred in a Broadway play titled The Big Fight, loosely based around Dempsey's boxing popularity, which ran for 31 performances at the Majestic Theatre.

She made a successful transition to sound films or "talkies." Her first sound film was the comical sketch Pusher in the Face (1929).

Notable sound films in which she appeared include Street Scene (1931), with Sylvia Sidney; the Academy Award for Best Picture-winning Cimarron (1931), with Richard Dix and Irene Dunne; and Call Her Savage (1932), with Clara Bow.

Taylor returned to films in 1944 with a small part in the Jean Renoir drama The Southerner (released in 1945), playing what journalist Erskine Johnson described as "a bar fly with a roving eye. There's a big brawl and she starts throwing beer bottles." Johnson was delighted with Taylor's reappearance in the film industry: "[Interviewing] Estelle was a pleasant surprise. The lady is as beautiful and as vivacious as ever, with the curves still in the right places." The Southerner was her last film.

Taylor married three times, but never had children. In 1911 at aged 17, she married a bank cashier named Kenneth Malcolm Peacock, the son of a prominent Wilmington businessman. They lived together for five years and then separated so she could pursue her acting career in New York. Taylor later claimed the marriage was annulled. In August 1924, the press mentioned Taylor's engagement to boxer and world heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey.[36] In September, Peacock announced he would sue Taylor for divorce on the ground of desertion. He denied he would name Dempsey as co-respondent, saying "If she wants to marry Dempsey, it is all right with me." Taylor was granted a divorce from Peacock on January 9, 1925.

Taylor and Dempsey were married on February 7, 1925 at First Presbyterian Church in San Diego, California. They lived in Los Feliz, Los Angeles. Her marriage to Dempsey ended in divorce in 1931.

Her third husband was theatrical producer Paul Small. Of her last husband and their marriage, she said: "We have been friends and Paul has managed my stage career for five years, so it seemed logical that marriage should work out for us, but I'm afraid I'll have to say that the reason it has not worked out is incompatibility."

In her later years, Taylor devoted her free time to her pets and was known for her work as an animal rights activist. "Whenever the subject of compulsory rabies inoculation or vivisection came up," wrote the United Press, "Miss Taylor was always in the fore to lead the battle against the measure." She was the president and founder of the California Pet Owners' Protective League, an organization that focused on finding homes for pets to prevent them from going to local animal shelters. In 1953, Taylor was appointed to the Los Angeles City Animal Regulation Commission, which she served as vice president.

Taylor died of cancer at her home in Los Angeles on April 15, 1958, at the age of 63. The Los Angeles City Council adjourned that same day "out of respect to her memory." Ex-husband Jack Dempsey said, "I'm very sorry to hear of her death. I didn't know she was that ill. We hadn't seen each other for about 10 years. She was a wonderful person." Her funeral was held on April 17 in Pierce Bros. Hollywood Chapel. She was interred at Hollywood Forever Cemetery, then known as Hollywood Memorial Park Cemetery.

She was survived by her mother, Ida "Bertha" Barrett Boylan; her sister, Helen Taylor Clark; and a niece, Frances Iblings. She left an estate of more than $10,000, most of it to her family and $200 for the care and maintenance of her three dogs, which she left to friend Ella Mae Abrams.

Taylor was known for her dark features and for the sensuality she brought to the films in which she appeared. Journalist Erskine Johnson considered her "the screen's No. 1 oomph girl of the 20s." For her contribution to the motion picture industry, Estelle Taylor was awarded a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 1620 Vine Street in Hollywood, California.

#estelle taylor#silent movie stars#silent era#silent hollywood#golden age of hollywood#classic movie stars#classic hollywood#silent cinema

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Portrait of George Klauber, Philip Pearlstein, 1976, Brooklyn Museum: Contemporary Art

© Philip Pearlstein

Medium: Oil on canvas

https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/168772

2 notes

·

View notes