#ghriba

Text

Moroccan Lemon Semolina Cookies / Lemon Ghriba (Vegan)

#vegan#desserts#moroccan cuisine#north african cuisine#african cuisine#cookies#ghriba#semolina#lemon#almond flour#applesauce#vanilla#olive oil#cane sugar#sea salt

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

The El Ghriba Synagogue, Djerba, Tunisia, 1995

182 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Natanel […] told me that two days before Purim, a few months before the Lag BaOmer attack, someone had come and shattered his jug art piece in the Djerba neighborhood. It was a heavy blow to him as an artist; he had spent weeks working on the installation and was proud of what he had accomplished. The jug beside him, inscribed in Arabic, was untouched.

I reflected on the words of the piyut written on the jug that Natanel had inscribed. The song is sung from the perspective of Serah, daughter of Asher, granddaughter of Jacob: “Baba Yacub Tlmali, Ml’ach El Mut Ma Yutzlali,” one stanza says. Translated from Judeo-Arabic it means: “My father Jacob told me, the angel of death won’t touch me.”

Natanel said that was his sign. “The two jugs side by side in Hebrew and Arabic were symbols of peace,” he told me. “The shattering of the Hebrew jug meant the shattering of peace. The song on the Hebrew jug represented a promise to protect El Ghriba and I understood after the attack that protection for El Ghriba was broken as well.” He shared photos with me of the broken shards of pottery speckled with his calligraphy. He lamented the destruction of his hard work and expressed sadness about the state of affairs in his community.

129 notes

·

View notes

Text

[ID: First image shows small cookies with cracked surfaces in a silver tin with pointed lid embossed with geometric designs; second image shows the same cookies on an engraved silver tray with a tea glass in the background. End ID]

غُريبة لبهلة / Ghriba l'behla (Moroccan shortbread cookies)

Ghriba l'behla (literally, "strange silly"), a popular teatime cookie, are perhaps so named because of the distinctive cracks that form on the surface of the cookies as they rise. Cookies without these distinctive cracks may be ghriba, but they are not ghriba l'behla. The melt-in-your-mouth, crumbly texture of ghriba is traditionally achieved with a 4 : 1 : 1 ratio of flour : sugar : oil.

Ghriba l'behla are commonly made with a specialized mold that gives them a concave bottom, thins them out around the edges, and causes them to crack more dramatically—the underside of a Dutch pancake pan or a mini idli tray would work for this purpose, but ghriba may also be made with a flat cookie sheet.

Though they may be made plain, ghriba are often flavored with toasted sesame, cinnamon, almonds, orange blossom water, and even lemon or orange zest. This recipe is for sesame-cinnamon ghriba, but you may also press an almond into the center of each cookie, coat them in powdered sugar, or add a couple teaspoons of orange blossom water or brine from a jar of Moroccan preserved lemons.

Recipe under the cut!

Patreon | Tip jar

Ingredients:

About 3 cups (360 - 390g) all-purpose flour

1/2 tsp fresh yeast (optional)

1/2 cup (70g) hulled sesame seeds, divided

1/2 cup (118mL) vegetable oil

1/2 cup vegan margarine or shortening, melted

3/4 cup (150 grams) vegetarian granulated sugar

Pinch of salt

1/4 tsp ground cinnamon

2 tsp baking powder

Instructions:

1. In a dry skillet over medium heat, toast sesame seeds until they are fragrant and a shade darker. Coarsely grind about half of the toasted sesame seeds in a mortar and pestle or spice mill. Set aside.

2. Melt margarine or shortening in a microwave or on the stovetop. Add sugar and stir to dissolve.

3. Combine margarine mixture and all other ingredients except for four in a large mixing bowl. Add flour a little at a time to make a dry, crumbly mixture that doesn't quite hold together when pressed; you may need more than 3 cups.

4. Knead the dough by hand, or use a stand mixer with the paddle attachment on its lowest setting, for 20 minutes. The dough should appear crumbly, like damp sand, but should now pack into a ball easily when pressed. Add more flour or oil if necessary to achieve this texture, kneading for another few minutes to incorporate.

5. Preheat your oven to 320 °F (160 °C) with the rack in its lowest position. Form the ghriba dough into balls about 3/4” (2cm) in width, packing them together with both hands and then flattening them silghtly between your palms. The edges of the dough should not crack or separate.

If you have a ghriba mold, gently press each ball of dough down over a bump on the mold, pressing down and thinning out the edges slightly to ensure a dramatic, concave bottom.

If you don't have a ghriba mold, place the ghriba on a baking sheet prepared with parchment paper. Make sure to separate them by about an inch, because they will rise slightly.

6. Turn on the broiler and broil the ghriba in the lower rack of your oven for 2-5 minutes, until cracks begin to appear on the surface.

7. Turn the broiler off and move the ghriba to the upper third of the oven. Continue to bake at 320 °F for 3-5 minutes, until very lightly golden brown and not quite firm to the touch.

8. Allow the ghriba to cool for 2 minutes, then transfer them to a wire cooling rack and allow to cool completely. Store in an airtight container.

262 notes

·

View notes

Photo

La Ghriba, the oldest synagogue in Africa, believed to have been founded in 586 BCE by Jews fleeing the destruction of the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem.

JERBA, TUNISIA.

995 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can i just say i LOVE all the little things you share about jewish culture.I am a goy who grew up in a place with an almost non existent jewish community and i only got introduced to it much later in life.I love seeing it through your eyes and adoption, it seems so precious to you

What are the favorite things you learned ?Is there anythings you would like to share about it you havent yet ?

I've been thinking about this a lot, because you sent me this ask a very long time ago and I could never settle on one thing. As soon as I started writing up one thing, I'd think of another. In fact, I just wrote up a whole thing about the "mezinke," a popular custom at frum weddings which seems to have been adopted into Jewish culture about 130 years ago and popularized by klezmer band leaders, but which people often think is much older.

But then I deleted it, because what I really love is this:

No matter how much I learn about Jewish culture, there is always more to learn. We have been everywhere, and we have been an integral part of the culture of everywhere that we've been. Jewish culture includes Sephardic recipes and Desi customs, its DNA contains strands from every settled continent and it continues to change, to grow, and to adapt. There are synagogues from Tokyo to Tasmania, from Recife to Regensburg. The El Ghriba Synagogue in Djerba, Tunisia was built in either 586 BCE or 70 CE (depending on your source) which makes it the oldest synagogue still standing and still in use. Jewish culture is a conversation l'dor v'dor -- from generation to generation -- and if there's one constant about us, wherever we are, it's that we never stop talking about the things that matter to us.

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

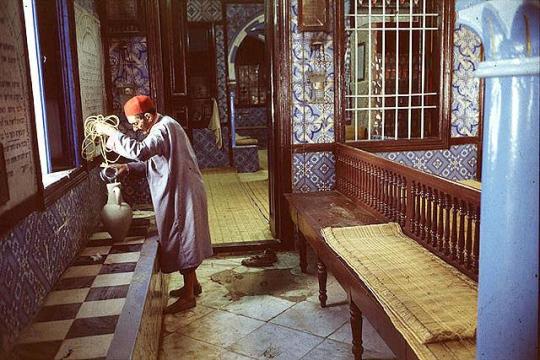

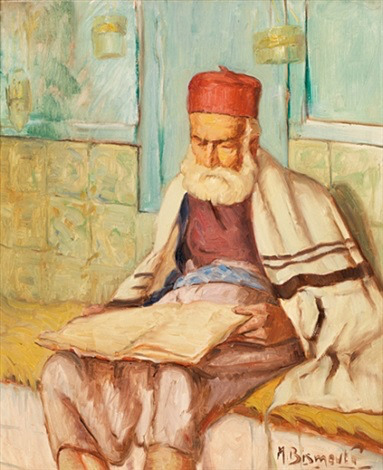

Portraits of Rabbis by Maurice Bismouth (Tunis, 1891–1965)

rabbis at the synagogue in al-hara (jewish quarter and ex ghetto of tunis), rabbi in prayer, rabbi in la ghriba (Djerba)

#mine*#my life if I could find his art in hd >>>>#art#יא אמנא#he has SO MANY more paintings of rabbis…

263 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lemon Ghriba; Classic Moroccan Semolina Cookie

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

May 2023: A Jewish pilgrim prays at the Ghriba Synagogue. [Yassine Mahjoub/AFP]

56 notes

·

View notes

Note

I will sign up for your Patreon for the sole purpose of voting for this caramelized onions and date basil pesto recipe. It looks so good! And thank you for the posting as always Miss Najia, always learning a lot and engaging with new ideas thanks to your blog.

yesss.... come over the dark side..... we have ghriba....

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

French court to investigate murder of Djerba pilgrim

Following the shooting attack on the Tunisian synagogue of La Ghriba during the Lag Ba’Omer pilgrimage, a French court dealing with terrorist incidents (PNAT) has launched an investigation into the death of Benjamin Hadad, 42, who had French nationality, according to i-24 News. The other victim, Aviel Hadad, had joint Tunisian-Israeli nationality

Benjamin Hadad (left) and Aviel Hadad, the murder victims

The court opened on Wednesday “an investigation of the head of the assassination in relation to a terrorist enterprise”. The investigations were entrusted to the General Directorate of Internal Security ( DGSI).

The attack, which took place as hundreds of worshippers were completing the annual Jewish pilgrimage to the Ghriba Synagogue, the oldest in Africa, left five dead: three security guards and the two aforementioned Jewish worshippers. The five victims were shot in front of the synagogue by the assailant.

“The attack on the Ghriba synagogue upsets us. We are thinking with pain of the victims, of the Tunisian people, our friends. We stand alongside the family of our murdered compatriot”, President Emmanuel Macron responded in a message published on Twitter. The Central Consistory of France on Wednesday condemned the attack “as cowardly as it is odious”.

In Tunisia, “a preliminary criminal investigation has been opened,” said Fethi Bakkouche, spokesperson for the court in Medenine (southeast Tunisia), whose jurisdiction covers the island of Djerba.

Read article in full (French)

Details emerge of the murder of five at Tunisian synagogue

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pilgrims celebrate Lag Ba-Omer at the El Ghriba Synagogue near Er Riadh, on Djerba, Tunisia. 1970.

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tunisia has largely moved on from the May 9 killing of five people at the El Ghriba synagogue on the island of Djerba by a National Guardsman. The event’s prominence on the country’s news sites has diminished and its claim on Tunisian conversation has largely been ceded to the other items competing for space at the national table.

On-air criticism of police recruitment methods by radio hosts Haythem El Mekki and Elyes Gharbi swiftly resulted in a legal complaint from the security services and, essentially, an end to discussion.

Thus far, Tunisia has steadfastly refused to publicly address the anti-Semitic nature of the attack, preferring instead to characterize it as “criminal.” However, the fact that the Jewish tourists and locals gathering to celebrate the festival of Lag B’Omer were specifically targeted by the attacker, 30-year-old National Guardsman Wissam Khazri, is hard to dispute.

After killing his colleague, Khazri donned body armor and rode 12 miles by quad bike to attack the pilgrims at the synagogue. However, beyond the arrest of four conspirators, his motivation for doing so, or details of any radicalization, remains unknown.

Responding to the murders, Germany and France characterized the attack as anti-Semitic, with Paris going even further and launching a terrorism probe into the killing of one of its citizens—a dual-national who was among the victims.

For Tunisian President Kais Saied’s government, the story was simply too messy. This year’s tourism revenues, which are vital following the uncertainty surrounding the hard-pressed country’s latest bailout from the International Monetary Fund, represent one of the few economic bright spots on a dark financial horizon. That security around the synagogue appeared to have failed—the attack was undertaken by one of the island’s supposed defenders—despite the massive expense and planning involved was also pushed to the sidelines.

However, underpinning all of this was the identity of the targeted victims and the deliberate and premeditated assault upon the Jewish community.

The Jewish presence in Tunisia reaches back almost 2,000 years. Over the centuries, through occupation by Phoenicians and Romans, conquest by Arabs, and colonization by Ottomans and the French, Tunisia’s Jews have maintained an unbroken thread linking past and present Tunisia. However, since World War II and the establishment of Israel in 1948, their numbers have dwindled. Pressure at home and opportunities overseas have reduced the population from around 100,000 in 1948 to less than 1,800 today.

Of all the Jewish communities that once dotted northern Tunisia, only that on the island of Djerba remains. The synagogue there, whose foundations are said to date back to Jerusalem’s Temple of Solomon, remains a cornerstone of not simply Tunisian Jewish identity, but Jewish identity as a whole.

The reasons for this declining population are rooted in recent history. Tunisia’s steadfast support of the Palestinian cause, a matter of profound faith for many, has embedded itself across all levels of society. From 1982 to 1985, Tunisia hosted the headquarters of the Palestinian Liberation Organization in a suburb just south of the capital, Tunis, until an Israeli air campaign essentially wiped it from the map, inspiring one of the first isolated assaults on the synagogue on Djerba by way of reprisal.

Many Tunisians are acutely aware of every injustice visited upon the Palestinian population. That, along with years of unflinching official opposition to the Israeli state, has almost certainly combined to make life in the country uncomfortable for many Tunisian Jews. By way of evidence, we only need to look to the spikes in emigration to both France and Israel that followed the Six-Day War in 1967 and the Yom Kippur War of 1973.

Whatever some may say, it is clear that what happens in the Middle East carries consequences for Tunisia’s Jews and how they’re regarded by their compatriots.

In the wake of the synagogue attack last month, one Twitter user achieved temporary notoriety after discovering that one of the victims, Aviel Hadad, was to be buried in Israel. Hadad had held dual citizenship with Israel and—in much the same way as many Muslims ask to be buried in Mecca, without opining on Saudi politics—had asked to be interred there. Nevertheless, one Tunisian blogger called for Hadad’s Tunisian family to be expelled from the country and any officials who knew of his wishes to be prosecuted.

A prominent journalist, on discovering that a victim of the attack held an Israeli passport, asked if the country was mourning Zionists. Across the country’s ubiquitous radio channels, a major source of news and information for many, conversations on Tunisia’s attitudes to Jews came to be almost exclusively couched in discussions on the Palestinian and Israeli conflict, with the fate and welfare of Tunisian citizens judged by the actions of a distant state that few had any connections with.

Unsurprisingly, the president has proven no exception. On a visit to the Tunis suburb of Ariana the weekend after the attack, Saied rejected accusations of anti-Semitism, recalling his own family’s history of offering shelter to Tunisia’s Jews during the 1942-43 Nazi occupation of the country, when Tunisia’s Jews faced extreme persecution. From there, he demonstrated little difficulty in segueing effortlessly into a discussion on Israeli attacks on Palestine. Their relevance to Tunisia’s Jews was not made clear.

“Despite the fact that most of the Jews of Tunisia have never set foot in Israel and that their homeland has been Tunisia for centuries, they are taken as scapegoats for actions committed in another part of the world,” said Joachim Lellouche, the son of Jacob Lellouche, a prominent member of the Tunisia’s Jewish community. The younger Lellouche, who grew up spending time in both France and Tunisia, told FP, “Most of the Jews in the world feel close to Israel—because of their ancestral history; that does not mean that they support the internal policy of the government.”

Lellouche, who spent his childhood shuttling between France and his father’s busy restaurant in La Goulette, a port town near Tunis, recalled the kind of prejudice his family encountered. “It’s ridiculous, but there’s this thing about Jews smelling of the dead,” he said. “Around 15, maybe 20 years ago, my father told us about a [Tunisian] man who came up and sniffed him. The thing is, that was a poor and uneducated man. Now, since the revolution, mass media and fake news, those attitudes are everywhere.”

Lellouche has seen the consequences of Tunisia’s anti-Semitism. In 2015, his father’s kosher restaurant, Mama Lily, a mainstay of cultural life in the city, closed due to anti-Semitic threats.

“Tunisia’s Jews are always held to a higher account,” Amine Snoussi, a Tunisian political analyst, said. “People always expect them to prove their loyalty to Tunisia and to reject Israel before they’ll even engage with them. No one else has to deal with that.”

“Jews, or minorities even, don’t really fit with [Saied’s] agenda,” Snoussi continued. “He doesn’t have time for them. He deals in a very utopian vision. Anything that contradicts that—such as anti-Semitism or the recent attacks on the country’s undocumented black migrants—has to be rejected and denied.”

In Snoussi’s opinion, Saied’s entire reaction to the synagogue attack has been shaped, not so much by any sense of anti-Semitism, but by his almost exclusively populist mindset. “He’s sought to frame this in terms of Palestine,” Snoussi said. “That fits with his ideas of what the country thinks, as well as the wider Arab nationalist world. He doesn’t think about Tunisia’s Jews. He doesn’t think about minorities. He doesn’t care how linking them so clearly to Israel puts them at risk.”

That attitude is causing real damage. In early May, the University of Manouba in Tunis announced it would revoke the title of professor emeritus from Habib Kazdaghli, a Muslim-born historian of Tunisia’s Jewish traditions who had attended a French conference alongside Israelis.

Hardline attitudes to Israel appear hardwired into entire strata of Tunisian society. “It’s not just me,” Kazdaghli told Foreign Policy via a translator. “It goes further. Tunisia’s wrestlers and tennis players have all been accused of normalizing relations with Israel through sporting events.

“I’ve been studying this for 25 years,” he said. “This bothers them. Every time they do this”—referring to the implicit barriers placed in the way of his research by both government and academia—“they’re saying they’re anti-Semitic without actually saying they’re anti-Semitic.”

Beyond his own academic specialism, Kazdaghli has grounds to speak with authority on the topic. He was on the bus outside El Ghriba synagogue when the May attack took place.

“Now when something happens, the state doesn’t address it,” he said. “I don’t think it’s anti-Semitism on their part. It’s more about being scared of even addressing the issue, and that’s worse.”

3 notes

·

View notes