#goat!ivan

Photo

“I don’t want to hurt anyone...”

Ko-fi | Patreon

#I thought Ivan's hair would be hard to transform but it really wasn't#minotaurox#my art#minotaurox redesign#goat!ivan#ox!ivan#dog!ivan#rooster!ivan#mouse!ivan#ml#miraculous ladybug#mouse miraculous#rat trap#rooster miraculous#spring chicken#dog miraculous#bull terror#goat miraculous#battering ram#ox miraculous#kwami swap

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

a hat-wearing man.

#original character#oc#ivan the terrible (oc)#sketch#didgital art#illustration#character design#artists on tumblr#artwins#horacek#he'll probably take some stupid nickname like#Johnny the Goat

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

View of Seaside Town in the Evening with a Lighthouse by Ivan Aivazovsky // You Were Cool by the Mountain Goats

207 notes

·

View notes

Text

CHAT. i just finished reading all the worlds a (alien) stage by @realfakedokja and it genuinely altered my brain chemistry. PLEASE GO READ IT AND SEND 8970 KUDOS IT IS SO GOOD IT MADE ME KICK MY FEET AND GIGGLE UNCONTROLLABLY.

#🦢🍸 thoughts !!#alien stage#alnst#ivantill#ivantill fic#alnst fic#alien stage ivan#alien stage till#guys i’m literally frothing at the mouth that was so good#ngl i was also really invested in the toxic exes hyuluka sub plot happening in the background#HYUNA THE GOAT I LOVED HER SO MUCH IN THIS FIC#there’s a cheer up reference in there and it made me want to bash my head against a wall#CHAT PLEASE READ IT ITS ACTUALLY SO GOOD#i love fanfics that portray luka as the loser he really is ❤️#this fic also uses the source material so creatively?!#like it translates events from canon alnst into real modern events that could happen#LIKE IM NOT GONNA SPOIL BUT THE WAY THE METEOR SHOWER SCENE GOT HANDLED MADE ME CRY AND SCREAM MY HEAD OFF. AND THE BAR SCENE IN ROUND 6#i’m genuinely so ill i am going insane

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

My favorite players on the field at the same time 🥹 I need to record it. Let me cry.

*Have a long time not draw kroos bc of some crazy fanclub n journalists, but I still love you Toni. *

#luka modric#ivan rakitic#toni kroos#fanart#art#football#real madrid#sevilla#10/22#my goats#my favourite midfielders#you never get old#23

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

A domestic goat.

© Ivan Radic / Flickr

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Now for the goat. The ability to create an item? Useless power. Lucky charm exists. And the "Kwami of Passion" doesn't really make itself clear. How about instead, we make Ziggy the Kwami of Evolution as opposed to the rabbit. It fits with Nathaniel's constant growth.

Now, with "Ramify" ( meaning branch out/grow and develop) the Goat has the power to unlock a hidden ability for all of the other miraculous. It can actually fix a lot. So instead of the whole "The only limits are the ones you put on yourself" thing from Pidgeon 72, we actually have an evolved form for all the Kwamis and use them.

For instance, giving the turtle shape-shifting light constructs out of "Shellter" or the fox the ability to actually camoflage. Seriously, Alya? Baby blue camo?

Anyway. I think a good weapon would be the tonfa. They're defensive weapon for Nathaniel to use while he mostly hangs back. Also, attacking would be like getting hit by a goat.

As for the Ox. The mallet? Good. But I personally prefer the concept art for it. More personality. Honestly, it's not bad. Though we all seem to agree that the costume is bland.

Is it a cultural thing? Cause I didn't get "biker leather" from this.

For the power, it fits, but a lot of us were thinking of something like strength. I'm thinking of something that involves hurling enemies(taken by tiger) or enlarging different parts of the users body. Maybe even enlarging other objects as a counterpart to the mouse.

Instead of the Kwami of Determination, we now have the Kwami of Expansion. I just want more Yin-Yang in this show. T_T

I will conquer all of these concepts if it's the last thing I do

#ivan bruel#ox miraculous#stompp#nathaniel kurtzberg#goat miraculous#Ziggy mlb#miraculous lb#miraculous fandom#miraculous ladybug#miraculous ladybug and chat noir#thomas astruc#concept art#miraculous kwamis

38 notes

·

View notes

Photo

ecstatic when he stands defiant, wild with abandon when he’s gone

“i’ve been blinded by the violence, me hand... hold me...”

#renchanting#martyn littlewood#rendog#spent gladiator 2 mountain goats#also inspired by ivan the terrible and his son#fallen angel cabanel#war pieta ginsberg#and also croweclips instantdamage martyrdom of saint denis piece#maybe a little bit inspired by treesekai bad ending#my art

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tumblr's Guide to Shostakovich- Asides- Ivan Sollertinsky

So, in addition to my weekly posting for Tumblr's Guide to Shostakovich, I decided I want to do a series of related "asides" posts. These will be posted irregularly (as opposed to weekly) and cover aspects related to Shostakovich that don't fit neatly into one post focusing on one part of the chronological timeline. In this case, I want to talk about Ivan Ivanovich Sollertinsky, specifically his role in Shostakovich's life and music. Sources I'll be citing include Elizabeth Wilson's Shostakovich: A Life Remembered, Shostakovich's own letters to Sollertinsky and Isaak Glikman, Dmitri and Lyudmila Sollertinsky's Pages from the Life of Dmitri Shostakovich, Pamyati I.I. Sollertinskogo (Memories of I.I. Sollertinsky), and I.I. Sollertinsky: Zhizn' i naslediye (Life and Legacy), the latter two both by Lyudmila Mikheeva. Photo citations include the DSCH Publishers website and the DSCH Journal photo archive.

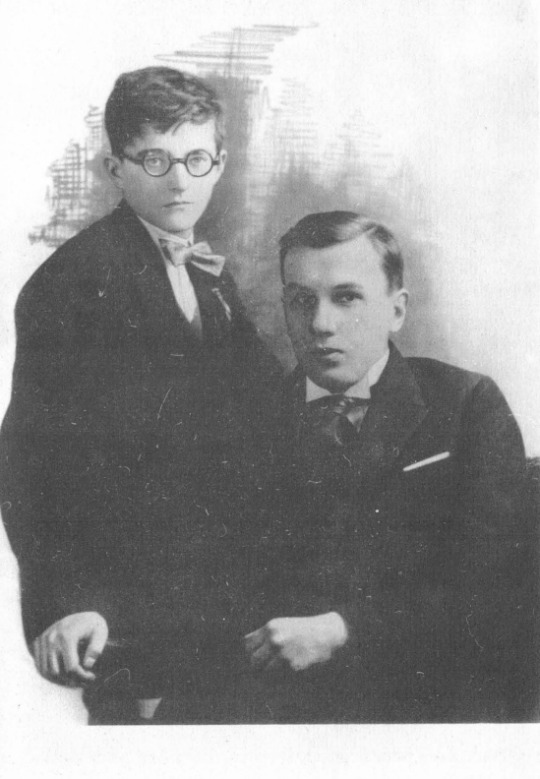

(Dmitri Shostakovich and Ivan Sollertinsky, Novosibirsk, 1942.)

Ivan Ivanovich Sollertinsky was born in Vitebsk, present-day Belarus, on December 3, 1902. He was a polymath, excelling in humanities fields, including linguistics, philosophy, musicology, history, and literature- particularly that of Cervantes. He specialized in Romano-Germanic philology, and spoke a wide range of languages; sources I've read vary from claiming he spoke anywhere from 25 to 30. (He specialized in Romance languages, but I can also confirm from sources that he studied Hungarian, Japanese, Greek, Sanskrit, and German. I've heard it said that he kept a diary in ancient Portuguese so nobody could read it, but I haven't seen this verified.) He had a ferocious wit, which he used to uplift friends and skewer enemies (there's a hilarious anecdote where he once saddled a critic opposed to Shostakovich with the nickname "Carbohydrates" for life), and worked as a professor, orator, and artistic director of the Leningrad Philharmonic. And yet, this impossibly bright star would burn out all too soon at the age of 41 due to a terminal heart condition, leaving his closest friend devastated- and inspired.

Dmitri Shostakovich first met Ivan Sollertinsky in 1921, when they were both students at the Petrograd Conservatory. While Shostakovich claimed he was at first too intimidated to talk to Sollertinsky the first time he saw him, when they met again in 1926, Shostakovich was waiting outside a classroom to take an exam on Marxism-Leninism. When Sollertinsky walked out of the classroom, Shostakovich "plucked up courage and asked him":

"Excuse me, was the exam very difficult?"

"No, not at all," [Sollertinsky] replied.

"What did they ask you?"

"Oh, the easiest things: the growth of materialism in Ancient

Greece; Sophocles' poetry as an expression of materialist tendencies; English seventeenth-century philosophers and something else besides!"

Shostakovich then goes on to state he was "filled with horror at his reply."

(...Yes, these are real people we are talking about. According to Shostakovich, this actually happened. And I love it.)

Later, in 1927, they met at a gathering hosted by the conductor Nikolai Malko, where they hit it off immediately. Malko recalls that they "became fast friends, and one could not seem to do without the other." He further characterizes their friendship:

When Shostakovich and Sollertinsky were together, they were always fooling. Jokes ran riot and each tried to outdo the other in making witty remarks. It was a veritable competition. Each had a sharply developed sense of humour; both were bright and observant; they knew a great deal; and their tongues were itching to say something funny or sarcastic, no matter whom it might concern. They were each quite indiscriminate when it came

to being humorous, and if they were too young to be bitter they could still come mercilessly close to being malicious.

(Shostakovich and Sollertinsky, 1920s.)

Sollertinsky and Shostakovich appeared to be perfect complements of each other- one brash, extroverted, and confident, and the other shy, withdrawn, and insecure, but each sharing a sarcastic sense of humour and love for the arts that would carry throughout their friendship. In Shostakovich's letters to Sollertinsky, we see him confide in him time and again, in everything from drama with women to fears in the midst of the worsening political atmosphere. When worrying about the reception of his ballet "The Limpid Stream," Shostakovich writes in a letter from October 31, 1935:

I strongly believe that in this case, you won't leave me in an extremely difficult moment of my life, and that the only person whose friendship I cherish, the apple of my eye, is you.

So, write to me, for god's sake.

And, in a moment of frustration from August 2, 1930 Shostakovich writes:

"You have a rich personal life. And mine, generally, is shit."

(Famous composers, am I right? They're just like us.)

In addition to a friendship that would last until Sollertinsky's untimely death, he and Shostakovich would influence each other greatly in the artistic spheres as well. Sollertinsky dedicated himself primarily to musicology after meeting Shostakovich (his first review of an opera, Krenek's Johnny, appeared in 1928, after they had become friends), and in turn, Sollertinsky introduced Shostakovich to one of his greatest musical inspirations- the works of Gustav Mahler. Much is to be said about Mahler's influence on Shostakovich's music, to the point where it deserves its own post, but it goes without saying that without Sollertinsky, Shostakovich's entire body of work would have turned out much differently. Starting with the Fourth Symphony (1936), Shostakovich's symphonic works began to take on a heavily Mahlerian angle (in addition to many vocal works), becoming a permanent fixture in his distinct musical style.

(Colorized image of Shostakovich, his wife Nina Vasiliyevna, and Sollertinsky, 1932. One of my absolute favourite photographs.)

Shostakovich's letters to Sollertinsky, from the 20s to early 30s, are characterized by puns and literary references, snide remarks, nervous confessions, and vivid descriptions of the locations he traveled to during his early career. However, as the 1930s progressed and censorship in the arts became more restrictive, signs of worry begin to take shape in the letters. This would all culminate in January 1936, with the denunciation of Shostakovich's opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District in Pravda. I'll go further into detail about the opera and its denunciation in a later post, but for now, I want to focus on its impact on Shostakovich and Sollertinsky's friendship.

As one of the first world-famous composers whose career began in the then-relatively young Soviet Union, targeting Shostakovich proved to be a calculated move. Due to his prominence and the acclaim he had previously received, both in the USSR and abroad, the portrayal of Shostakovich as a "formalist" meant someone had to take the blame for his supposed "corruption" towards western-inspired music and the avant-garde. The blame fell upon Sollertinsky, who was lambasted in the papers as the "troubadour of formalism." To make matters worse, Sollertinsky had long showed a fascination with western European composers, such as the Second Viennese School, and had previously praised Lady Macbeth in a review as the "future of Soviet art." An article in Pravda from February 14, 1936, about less than a month after the denunciation, stated:

“Shostakovich should in his creation entirely free himself from the disastrous influence of the ideologists of the ‘Leftist Ugliness’ type of Sollertinsky and take the road of truthful Soviet art, to advance in a new direction, leading to the sunny kingdom of Soviet art.”

Critics who had initially praised Lady Macbeth had begun to retract their positive reviews in favour of negative ones, and a vote was cast on a resolution on whether or not to condemn the opera. According to Isaak Glikman, their mutual friend, Shostakovich spoke with Sollertinsky, who was conflicted on what to do, beforehand. Although Sollertinsky didn’t want to condemn his friend, he supposedly told Glikman that Shostakovich had given him permission to “vote for any resolution whatsoever, in case of dire necessity.” When denouncing the opera (supposedly with Shostakovich's permission), Sollertinsky had commented that in order to develop a ��true connection” to the Soviet public, Shostakovich would have to develop a “true heroic pathos, and that Shostakovich would ultimately succeed “in the genre of Soviet musical tragedy and the Soviet heroic symphony.” After Shostakovich’s second denunciation in Pravda of his ballet, “The Limpid Stream,” and the withdrawal of his Fourth Symphony- arguably the most Mahlerian of his middle period works- the Fifth Symphony, easily interpreted to follow these criteria, had indeed restored him to favour. Sollertinsky’s reputation, too, was saved.

(Aleksandr Gauk, Shostakovich, Sollertinsky, Nina Vasiliyevna, and an unidentified person, 1930s.)

In 1938, Sollertinsky contracted diphtheria. Ever tireless, he continued to dictate opera reviews and even learned Hungarian while hospitalized, although he became paralyzed in the limbs and jaw. Shostakovich wrote to him often with touching concern:

Dear friend,

It's terribly sad that you are spending your much needed and precious vacation still sick. In any case, when you get better, you need to get plenty of rest.

By the time the letters from this period break off, it's because Shostakovich was able to visit Sollertinsky in the hospital, which he did whenever he was able.

While Sollertinsky was able to recover, their friendship would face yet another test in 1941, due to the German invasion of the Soviet Union during WWII. Sollertinsky evacuated with the Leningrad Philharmonic to Novosibirsk, while Shostakovich chose to stay in Leningrad. However, as the city fell under siege, due to the safety of his family, Shostakovich fled with Nina Vasiliyevna and their two children to Kubiyshev (now Samara) that October, having spent about a month in Leningrad during what would be one of the deadliest sieges of the 20th century. It was in Kubiyshev that Shostakovich would finish his famous Seventh Symphony (which, again, will receive its own post), before eventually moving permanently to Moscow (although he still taught for a time at the Leningrad Conservatory).

During this period of evacuation, Shostakovich's letters to Sollertinsky are heartbreaking. We not only see him pining for his friend, but worrying for his safety and that of his family, including his mother and sister, who were still in Leningrad at the time. Still, he reminisces of their time together before the war, with the hope that he and Sollertinsky would be back home soon. In a letter from 12th February, 1942:

Dear friend, I painfully miss you, and believe that soon, we will be home, and will visit each other and chat about this and that over a bottle of good Kakhetian no. 8 [a Georgian wine]. Take care of yourself and your health. Remember: You have children for which you are responsible, and friends, and among them is D. Shostakovich.

In 1943, Sollertinsky arrived in Moscow, where Shostakovich was living at the time, to give a speech on the anniversary of Tchaikovsky’s death. At long last, they finally were able to see each other, and anticipated that soon enough, their long period of separation, made bearable only by letters and phone calls, would come to an end: Sollertinsky, living in Novosibirsk, was planning to return to Moscow in February of 1944 to teach a course on music history at the conservatory. When he and Shostakovich said their goodbyes at the train station, neither of them knew it would be the last time they saw one another.

Sollertinsky's heart condition, coupled with his tendency to overwork, poor living conditions, heavy drinking, and added stress, often left him fatigued. On the night of February 10th, 1944, due to a sudden bout of exhaustion, he stayed the night with conductor Andrei Porfiriyevich Novikov, where he died unexpectedly in his sleep. His last public appearance had been the speeches he gave on February 5th and 6th of that year- the opening comments for the Novosibirsk premiere of Shostakovich’s 8th Symphony. A remarkable amount of telegrams and letters from Shostakovich to Sollertinsky survive and have been published in Russian. Some seem hardly significant; others carry great historical importance. Sollertinsky took many of them with him from Leningrad during evacuation; those letters were considered among his most prized possession. His son, Dmitri Ivanovich Sollertinsky, was named after Shostakovich- breaking a long tradition in his family in which the first son was always named "Ivan."

As for Shostakovich, we have letters to multiple correspondents detailing just how distraught he was for months after receiving news via telegram of Sollertinsky’s death. To Sollertinsky’s widow, Olga Pantaleimonovna Sollertinskaya, he wrote:

“It will be unbelievably hard for me to live without him. [...] In the last few years I rarely saw him or spoke with him. But I was always cheered by the knowledge that Ivan Ivanovich, with his remarkable mind, clear vision, and inexhaustible energy, was alive somewhere. [...] Ivan lvanovich and I talked a great deal about everything. We talked about that inevitable thing waiting for us at the end of our lives- about death. Both of us feared and dreaded it. We loved life, but knew that sooner or later we would have to leave it. Ivan lvanovich has gone from us terribly young. Death has wrenched him from life. He is dead, I am still here. When we spoke of death we always remembered the people near and dear to us. We thought anxiously about our children, wives, and parents, and always solemnly promised each other that in the event of one of us dying, the other would use every possible means to help the bereaved family. ”

Shostakovich stuck to his word, making arrangements for Sollertinsky's surviving family to return to Leningrad after it had been liberated, going through the painstaking process of acquiring the necessary documentation and allowing them to stay at his home in Moscow in the meantime.

In 1969, he would write to Glikman:

“On 10 February, I remembered Ivan Ivanovich. It is incredible to think that twenty-five years have passed since he died.”

Furthermore, Shostakovich recalled:

Ivan Ivanovich loved different dates. So he planned to celebrate the twentieth anniversary of our acquaintance in the winter of 1941. This celebration did not take place, since the war had ruined us. When in our last meetings, we planned the 25th anniversary of our friendship for 1947. But in 1947, I will only remember that twenty-five years ago life sent me a wonderful friend, and that in 1944 death took him away from me.

And yet, there was still one more tribute left to make. Shostakovich had already dedicated a movement of a work to Sollertinsky- a setting of Pasternak's translation of Shakespeare Sonnet no. 66 in Six Romances on Verses by English Poets- but after Sollertinsky's death, he completed his Piano Trio no. 2 in August of 1944, a work that had taken months to finish. While he had started the work before Sollertinsky's death and mentions it in a letter to Glikman as early as December 1943, it would since bear a dedication to Sollertinsky's memory.

The second movement of the Trio is a dizzying, electrifying Allegro con Brio- and probably my favourite work of classical music, ever. Sollertinsky's sister, Ekaterina Ivanovna, was said to have considered it a "musical portrait" of her illustrious brother in life, with its fast-paced, jubilant air. The call-and-response between the strings and piano seem, to me, to reflect one of Shostakovich and Sollertinsky's early Leningrad dialogues- the image of two friends out of breath with laughter, each talking over each other as they deliver witty comebacks and jokes that only they understand. For the few minutes that this movement lasts, it is as if Shostakovich and Sollertinsky are revived, if not for just a moment, the unbreakable bond that defied decades of hardship now immortalized in the classical canon, forever carefree and happy in each other's company.

And then comes the pause.

It is this silence between the Allegro con Brio and Adagio that is the loudest, most powerful moment of this piece as eight solemn chords snap us into reality, like the sudden revelation of Sollertinsky's death- as Shostakovich said, "he is dead; I am still here." These eight chords form the base of a passacaglia, the piano cycling through them and nearly devoid of dynamics as the cello and violin sing a lugubrious dirge. The piano- Shostakovich's instrument- seems to mirror the stasis of grief, the inability to move on when paralyzed by loss.

The final movement of the Trio, the Allegretto, seems to speak to a wider form of grief. By 1943, the Soviet Union was receiving news of the Holocaust, and the Allegretto of Shostakovich's Trio no. 2 is among the first instances of Klezmer-inspired themes in Shostakovich's work (not counting the opera Rothschild's Violin, a work by his student Veniamin Fleischman that he finished after Fleischman's death in the war). The idea that the fourth movement is a commentary on the Holocaust is the most popular interpretation for Shostakovich's use of themes inspired by Jewish folk music, but other interpretations include a tribute to Fleischman (who was Jewish), or a nod to Sollertinsky's birthplace of Vitebsk, which had a substantial Jewish population until the Vitebsk Ghetto Massacre in 1941 by the Nazis. (While I haven't read anything confirming that Sollertinsky was ethnically Jewish, the painter Marc Chagall and pianist Maria Yudina, both carrying associations with Vitebsk, were.) Whether the grief expressed here was personal or referencing the larger global situation, the quotation of the fourth movement's ostinato followed by the final E major chords suggest a peaceful resolution after a long movement of aggressive tumult and grotesque rage.

Shostakovich would continue to grieve and remember Sollertinsky, but the ending of this piece- composed over the course of about nine months- perhaps implied closure and healing. In the following years, the war would end, Shostakovich would form new connections (such as a lasting friendship with the composer Mieczyslaw Weinberg), and, as he had done through tragedy before, would continue to write music. Sollertinsky was gone, but left a mark on Shostakovich's life and work, his memory carried in every musical joke and Mahlerian quotation that found its way onto the page.

(Shostakovich at Sollertinsky's grave, 1961, Novosibirsk.)

(By the way, check the tags. ;) )

#shostakovich#dmitri shostakovich#tumblr's guide to shostakovich#classical music#music history#soviet history#ivan sollertinsky#russian history#classical music history#composer#music#history#also fun fact sollertinsky and shostakovich almost wrote a don quixote ballet together but that didn't work out bc shost got denounced#they had an inside joke about a fake composer named persianinov. they invented goncharov you guys#there's one letter from shost to sollertinsky about the time a ballet worker tricked another worker into eating goat shit#sollertinsky would apparently come over to shost's house and sing mahler symphonies in a 'high squeaky voice'#like from memory#they'd write riddles to each other in letters#i love them so much#they are everything to me#apparently they'd also run over to each others' houses to deliver letters if they couldn't see each other#in leningrad ofc#sollertinsky got REALLY PISSED once bc someone suggested changing a bit of shost's music in lady macbeth it was really funny#shost once said sollertinsky had a 'magical influence on the female sex' and like . look at him#he's not wrong#oh btw it's 3 am and I have work tomorrow#oh one last fact they loved to go on roller coasters together (in russia they call them 'american mountains') but#the one they liked burned down lol

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

My tag for this series is 'fairy tales'.

#polls#fairy tales#folktales#the naughty boy#the moon#masha and the bear#ivan the fool#the wolf the goat and the cabbage#the three princes and their beasts#the dragon princess#the clever cat#the girl with the golden gizzard

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Greatest male tennis player of all time

Determining the greatest male tennis player of all time is a complex and subjective matter, as there are many factors to consider, such as Grand Slam titles, weeks at No. 1, overall win-loss record, dominance against other top players, and impact on the sport

For more detail click the link

#greatesttennisplayerofalltime#novakdjokovic#rafaelnadal#rogerfederer#grandslamtitles#tennis#goat#winner#champion#menstennis#sport#andre agassi#John McEnroe#Ivan Lendl#Jimmy Connors#Bjorn Borg#Pete Sampras#Rod Laver

0 notes

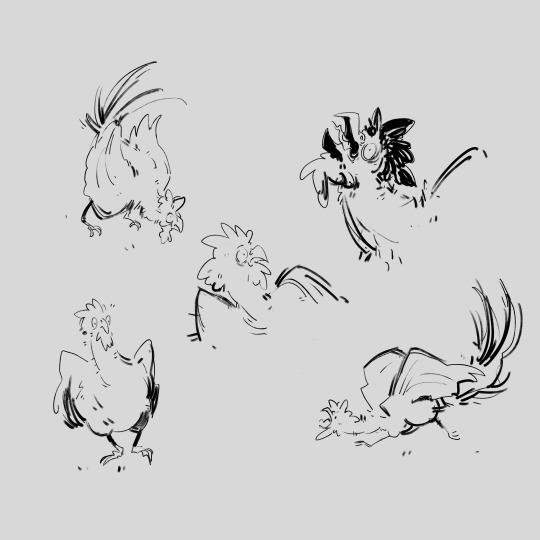

Photo

hhhhhh

#sketches#original character#oc#chort#goat#ivan the terrible (oc)#rooster#sketch dump#slavic mythology#slavic folklore#didgital art#artists on tumblr#artwins#horacek#evgen the rooster

185 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Alexander the Great vs Ivan the Terrible. Epic Rap Battles of History

1 note

·

View note

Text

i love you, i do, but i cannot fucking stomach you

1. richard siken | 2. david foster wallace | 3. slavoj žižek | 4. x? | 5. succession, jesse armstrong. gif by @lesbiankendall | 6. orla gartland | 7. trista mateer | 8. ilya repin | 9. iain thomas | 10. thoroughbreds, cory finley | 11. yrsa daley-ward |

text id below

1. sometimes you get so close to someone you end up on the other side of them

2. [in red highlight] everything i’ve ever let go of has claw marks on it.

3. [white text on a background of a field] A FRIEND HAS TO BE OUTSIDE MY REACH, BEYOND MY GRASP. AND THERE CAN BE NO FRIENDSHIP WITH SOMEONE WHOM I AM NOT READY TO BETRAY: A FRIEND IS SOMEONE I CAN BETRAY WITH LOVE.

4. Long before Caesar and Brutus were lessons, they were friends. // They played with stick swords in their kingdom of trees // and dressed up in crowns of flowers // and painted mud on each other's faces. // The pair was often found walking down dirt roads, // Caesar stomping proud and tall, // and Brutus- step by step- placing his feet into the footprints left behind. // Caesar grew into a strong Roman man. // Brutus grew into Caesar's shoes. // They walked to a wishing well and they threw in their weapons // and Caesar whispered a prophecy: // "We live and die together." // The day before the slaughter, Brutus took pause. // He turned to Caesar and thought // "I'll love you twice as hard today to make up // for tomorrow," // and they stayed up and played cards on the kitchen floor. // It wasn't until the next morning that Brutus realized how cold the tile was. // Life and death are not mutually exclusive. // When Caesar died, so did Brutus, in the sense that he never really lived again. // In the present, when someone mentions one of them, // they seldom exclude mention of the other.

5. a scene from succession. the characters kendall and stewy are in a dimly lit alley, one walks away from the other while saying “you’re my third oldest friend. you fucked me like a tied goat. we’re great.”

6. I'm not happy if you're not happy // And swear that you're always sad // You're pathetic, I resent it // When you're down, it hurts so bad

7. I've gotten so good about not flinching at the sound of your name that people don't know I'd still throw myself mouth-open into the ocean for the chance to drown somewhere you might see it.

8. the painting ‘Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivana’. it depicts a man holding another man who is bleeding profusely from his head.

9. there are a million ways to bleed, but you are by far my favorite.

10. scene from the movie thoroughbreds. a character lays crying wrapped around her friend, she is covered in blood, her friend is unconscious.

11. [in pink highlight] and be wary of friends, yeah? they are the ones who kill you, in the end.

#web weaving#toxic frienship#toxic friends#toxic relationship#parallels#succession#thoroughbreds#yrsa daley ward#orla gartland#richard siken#david foster wallace#iain thomas#mine <3#requested <3#1k

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

don't think too hard about fang. don't think too had about fang. don't think too hard about this intelligent, sweet, wise man on a boat for 20 years watching his boss get yanked around by the middle manager. and also getting yanked around by the middle manager himself. don't think about fang watching his boss, a once energetic and enthusiastic man, slowly becoming more and more a shell of himself because of said middle manager. who he refuses to fire. for some reason. maybe fang has some theories, but he doesn't know for sure. he doesn't see the boss as much anymore. any interaction with him is mediated by the middle manger, who's just gotten crueler as the years go by too. he keeps his head down and does what he's told. he's been doing this for a very, very long time, and knows what he has to do to live. and he enjoys the work, more or less, don't get me wrong. but, you know... maybe not as much as he could. and then they invade some crazy guy's boat, and then the boss is happier than fang's seen him in literal years. and this boat is cool! the people are nice! he doesn't have to be aggro all the time.

and then the middle manager blows a fuse and gets the british navy. and fang resigns himself back to business as usual. because that's how he's gonna survive. but then the boss comes back!! without the lunatic man. and for a second everything might be okay, but then something goes wrong, and again, fang doesn't know what, and then things are worse than they ever were before in the 20 years he'd been working for this man. and he keeps his head down and does what he's told because that's how he's gonna survive. and then his buddy dies. and his boss, who fang knows by this point can be very sensitive, doesn't cry a single tear. fang breaks down a little after a while. they can't keep going like this.

but it's okay!! the lunatic comes back and so does everyone else. and things are good, the middle manager mellows out, he and the boss have a talk and sort things out. life is good. he has a goat!

and then the middle manager dies. and that's weird, you know? and the boss decides he's done, so he hangs back on land while everyone else sails off into the sunset. and fang's happy, but it's irrevocably different. two men he spent at least a decade with are dead. one man, who he sometimes felt like an older brother to despite the other man being the boss, is now on land, and no longer part of his day-to-day life. he's the most experienced guy on this boat. well, it's possible a few others, like zheng, have been doing this for over 20 years, but chances are he's been in this world the longest. and a chapter just ended and a new one's beginning. and he'll keep doing his thing, following captain's orders. maybe give a gentle suggestion from time to time.

he was in this world before ivan, before izzy, before ed. and now they're retired or dead and he's still here. why is he still here? why did he outlive them? why did ivan and izzy have to die? why did... well, he understands why ed retired. but still.

now he has inside jokes and no one to share them with. memories and no one around to share in the bizarre nostalgia. but on this boat, this silly boat that breaks all the rules, he can make new memories and create a million more inside jokes, and be around people who really truly like him. love him, even.

185 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rakitic🥹🥹🥹 how beautiful day today

my two man one assist one goal

38 n 35 years = good wine 🍷

7 notes

·

View notes