#harald braun

Text

kabale und liebe, harald braun 1959

*

youtube

#kabale und liebe#harald braun#friedrich schiller#1959#inge meysel#heidi mentz#marie-luise etzel#herta fahrenkrog#christian wolff#boy gobert#herbert fleischmann#der alte und der junge könig#1935#fridericus#1936#tanz auf dem vulkan#1938#kohlberg#1945#marie antoinette#2006#the wicked lady#barry lyndon#the shooting party#lost highway#russian ark#i want candy#bow wow wow#mozart i saljeri

1 note

·

View note

Text

Cartel película "Mientras estés a mi lado" (Solange du da bist) 1953, de Harald Braun.

1 note

·

View note

Text

youtube

Tem no youtube: Sob Fogo Cruzado (The Last Escape, 1970)

#The Last Escape#70's movies#Walter Grauman#war movies#Stuart Whitman#John Collin#Martin Jarvis#Margit Saad#Harald Dietl#Pinkas Braun#Patrick Jordan#Johnny Briggs#Gerd Vespermann#Youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

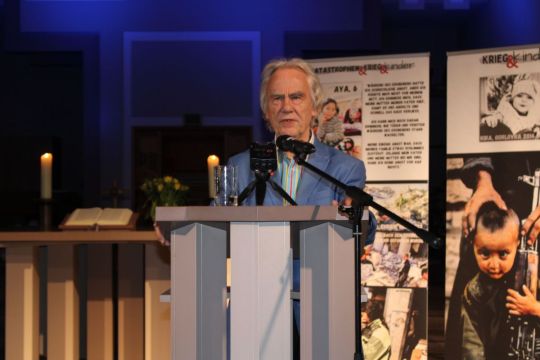

Reiner Brauns interessanter Vortrag "Wie ist Frieden in der Ukraine möglich?" in der Dortmunder Pauluskirche

Reiner Brauns Arbeit ist seit Jahrzehnten intensiv in der Friedensbewegung aktiv. Nicht zuletzt versteht er sich als Brückenbauer, um auch widerstreitende Positionen in der Sache zusammenzuführen. Willy Brandts Worte sind ihm Verpflichtung: «Der Frieden ist nicht alles, aber alles ist ohne den Frieden nichts.« Braun hat seinerzeit den „Krefelder Appell“ wesentlich mit initiiert.

Diese Woche…

View On WordPress

#Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists#Dort#Erich Vad#friedrich laker#Harald Kujat#IPPNW#Krieg&Kinder#Nato#pauluskirche und kultur dortmund#reiner braun

0 notes

Text

In zehn Jahren über 5.500 Einsätze

In zehn Jahren über 5.500 Einsätze

Dr. Harald Genzwürker übernimmt am 01. Juli die Jubiläumsschicht am Notarztstandort Osterburken an der DRK-Rettungswache. (Foto: Braun) Notarztstandort Osterburken feiert Jubiläum Osterburken. (pm) Die „Jubiläumsschicht“ am Montag, 01. Juli, fährt der Leitende Notarzt Dr. Harald Genzwürker selbst. An diesem Datum kann der Notarztstandort Osterburken auf seinen zehnten Geburtstag zurückblicken. Dass dieser Standort etabliert wurde, war unter anderem dem beharrlichen „Bohren“ von Dr. Genzwürker zu verdanken. Auch Landrat Dr. Achim Brötel und die beiden DRK-Kreisverbände Mosbach und Buchen setzten sich stark für den damals vierten Notarztstandort im Neckar-Odenwald-Kreis ein. Inzwischen wurden von Osterburken aus über 5.500 (Stand Mai) Notarzteinsätze gefahren. Hintergrund

Lesen Sie den ganzen Artikel

0 notes

Text

Cancel Culture erklärt Menschen für dumm

Compact:»Zitat des Tages: „Ob Otto, Harald Schmidt, Winnetou oder Pippi Langstrumpf: Alles ist auf einmal rassistisch oder zumindest diskriminierend. Es wird gewarnt und verändert. Die Menschen werden so entmündigt und für dumm erklärt.“ (Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung) „Mittlerweile sind die Tugendwächter hinter so ziemlich allen Büchern her, die uns die Jugend versüßten. ‚Unsere braune Biene Maja‘ [...]

Der Beitrag Cancel Culture erklärt Menschen für dumm erschien zuerst auf COMPACT. http://dlvr.it/Sv8SLg «

0 notes

Video

youtube

Maria Schell als Eva Berger und O. W. Fischer als Frank Tornau in “Solange du da bist” (1953)

Durch einen Unglücksfall während der Dreharbeiten zu seinem neuesten Film lernt der Regisseur Frank Tornau die sich als Komparsin betätigende junge Flüchtlingsfrau Eva Berger kennen. Der von der Monotonie seiner belanglosen Filme ausgebrannte, rücksichtslose Erfolgsmensch Tornau wittert in dem von Eva und ihrem Mann Stefan inmitten der Krieges erfahrenen Leid die Story zu einem gänzlich anderen Filmstoff, der ihm wieder zu echtem künstlerischem Erfolg verhelfen soll, und so inszeniert er mit Eva in der Hauptrolle einen Film über ihr eigenes Schicksal. Die unprätentiöse junge Frau wird immer mehr von der charismatischen Aura von Frank Tornau fasziniert. Er wiederum glaubt in ihr endlich den Menschen gefunden zu haben, der ihn von seiner innerlichen Leere befreien kann - und gefährdet damit bewusst Evas Ehe.

Das anspruchsvolle Melodram von Harald Braun markiert die dritte Zusammenarbeit von Maria Schell und O. W. Fischer und lebt ganz und gar von dem nuancenreichen und emotional intensiven Zusammenspiel der Beiden.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Leaving the Summer Behind

While it is a true pleasure to discover something new in the rich history of cinema, there always lurks a danger when it comes to evaluating these novel discoveries. The danger is due to the fact that one is usually more easily lured by the enchantment of exoticism, the allure of the unknown, than the ordinariness of the familiar. This Spring proved to include one of the most interesting program series in years for the Finnish film archive: a series of West-German films from the 1950′s curated by the film critic Olaf Möller who is insanely familiar with the blind spots of film history. Perhaps telling of the oblivion surrounding the era is that I had seen only one film from it prior to the series [1]. I was able to catch eleven films out of the fourteen films of the series [2], which surely makes me less than a connoisseur of the period, but provides me with enough information to prefer one film over another (I think) in a fashion cleared from the diversions of exoticism (I hope). The two films I was most fascinated by were Helmut Käutner’s The Rest Is Silence (1959, Der Rest ist Schweigen) and Harald Braun’s The Last Summer (1954, Der letzte Sommer). Discussion on the former shall be postponed and the latter shall be tackled now. The Last Summer is less well-known than Käutner’s semi-classic; it is, in fact, incredibly unknown outside Germany, though it is available on YouTube in poor quality, to the extent that it has less than 20 ratings on IMDb and that this is the first post on this site with the tags of the film’s title and its director both of whom are, however, very worthy of attention.

Based on a novel by Ricarda Huch, The Last Summer tells the story about a young man, Rikola Valbo (played by Hardy Krüger) arriving to a small fictional town by train in order to assassinate the president just roughly two weeks before the next election. Aided by his partner-in-crime Gawan, Rikola sabotages a bridge which the president is about to cross in his car. As the girl who Rikola has met earlier, Jessika (played by Liselotte Pulver) approaches from the other side of the bridge, Rikola waves at her to warn her which is simultaneously seen as a sign directed to the president whose car is approaching from the opposite side. As the president exits his car and comes to Rikola, Gawan escapes from his hideout under the bridge, but Rikola is mistakenly perceived by the president as his savior which makes Rikola the-son-he-never-had for him. When Rikola moves to the president’s residence, he finds out that Jessika is the president’s daughter. Rikola is torn by a dilemma: his obligation toward Gawan and the mission, his budding romance with Jessika, and his ever-growing understanding for the president. His dilemma deepens as Gawan is killed by the president’s guards during an intense sequence of duck hunting. Rikola struggles between the options to assassinate and not to assassinate, but ends up letting go of the mission as well as his relationship with Jessika.

Reasons for the film’s worthiness to my mind are plenty. Its exquisite functionality comes down essentially to a fluent stylistic program, great acting by Krüger and Pulver especially, and polished dramaturgy where all that is not necessary has been excluded. The milieu is a fictional village whose gorgeous mountains, lakes, and landscapes remind one of Switzerland. There is a surreal quality to this milieu as the townspeople gather around big speakers from where the president’s voice emerges to proclaim political truths. In a word, the film has a tone and a mood like no other.

Braun’s precise and detailed mise-en-scène in The Last Summer creates the setting for a layered utilization of both deeper and shallower planes in beautiful dynamic compositions. The classical three-point-lighting is soft, giving an impression of the Sun gently shining in the summer sky on the space inhabited by the characters as well as the Moon lightly shining in the dusk. The editing rhythm is calm, and the camera moves as it follows the characters. Besides such following shots, camera movement also occurs often when the camera tracks forward to the characters, compressing the framing as well as the atmosphere, or backward from the characters, expanding the framing and amplifying the characters’ embeddedness to the environment. Changes to the consistent stylistic program include a canned camera angle when Rikola reveals his original intentions of assassination to Jessika, thus emphasizing the dramatic effect: something is about to break in a way that cannot be fixed. Another is the way how Braun leaves the camera to linger on an empty space for a brief moment after Rikola leaves the railway station where he went after the above revelation and where he encountered the grief-stricken wife of Gawan. The accusing gaze of the wife directed to Rikola is utterly stirring in the film’s only (to the best of my knowledge) point of view shot. It is convincing enough to convince Rikola to consider the assassination once more, though he gives it up again after talking with the president, as well as to convince the spectator of the utilization of the cinematic device which would seem contradictory to the stylistic consistency of the film.

In addition to guilt, integral themes concern the moral and political questions which arise from the conversations between Rikola and the president. In one of his speeches through the speakers, the president divides the politicians into two groups: those who believe in change and those who believe in preservation. Rikola represents the former, that is, liberalism, while the president does the latter, that is, conservatism, though he might wish to see himself in a middle ground between such opposites. In one of their conversations, Rikola demands in a nearly Rousseauesque fashion that a leader ought to govern for the people, whereas the president puts emphasis on the mission of helping the people. Both notions could have their paternalistic connotations, but surprisingly enough Rikola seems to lie more into this direction in his quasi-enlightenment faith in the general will à la Rousseau. In the great finale, where Rikola returns to the president’s residence, which he left after revealing his plan of assassination to Jessika, to try to avenge Gawan’s death, the president manages to make Rikola give up his bullets which he shoots into the cold solitude of the moonlit night. The president manages to do this by claiming that violence can be just as well a form of weakness as it can of strength. He considers Rikola’s solutions and the thought processes behind them to be simple and naive. In a powerful speech, he proclaims that it is much more difficult to still have faith in humanity after all one has been through, adding that he himself does, nonetheless.

There are many ways to interpret this ending, I believe. First, it could be seen as reactionary. One could argue that Braun shows signs of reactionary thought before the radical 60′s as the youth dreaming of social change have to give up on their naive dreams on the threshold of maturity. This interpretation could, in fact, be wider when it comes to the German cinema of the 50′s and as such explain why the era was buried after the Oberhausen manifesto of 1962 changed German cinema for good. Second, the ending could be seen as pessimistic. One could argue that Braun portrays the president as a manipulating figure who succeeds in deceiving Rikola to give up his ideals which are a threat to his established republican power. On the level of explicit meaning, perhaps the first interpretation seems more appropriate, emphasizing an uplifting moral, but on the level of implicit meaning, many questions are left open with regards to the president and his potential tyranny. For one, why were Rikola and his associates so keen on assassinating him had he not done anything wrong? Why does he proclaim his political messages through speakers rather than talking to the people of his nation directly, something that is never seen in the film? Third, the ending could be seen as a mutual synthesis where Rikola leaves extreme radicalism and violence behind, but where his presence has also provoked a reconsideration of social values in the president’s family: we see, for example, that Jessika begins to question the moral entitlement of the privileged position of her presidential family.

Braun’s film refuses to give easy answers which makes it an exception in political cinema of the time. Few comparisons come to mind when it comes to films of the 50′s which tackled such complex social questions in such a layered fashion. Though quite a different film, Kazan’s Face in the Crowd (1957) does come close. It is interesting to compare Braun’s The Last Summer with two films in particular. In the program series I saw, it was screened right after Falk Harnack’s Der 20. Juli (1955), which is one of the many films about the famous Operation Valkyrie, the attempt of high German officials to assassinate Adolf Hitler during WWII. In Harnack’s film, the assassination, of course, fails, but the film ends with an uplifting, nearly spiritual note where the attempt in itself is felt as something vital. In Braun’s film, on the other hand, the assassination does not fail, but it is abandoned due to a more or less ambiguous change of heart. As the above discussion might point out, Braun’s film comes across surprisingly as more pessimistic. The other comparison I would like to draw is a peculiar one, that is, Michelangelo Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point (1970) which ends with the phoenix-like ideological reawakening of a young woman who fantasizes a political mass destruction. The film famously ends in a montage where the American capitalist society blows up to pieces followed by a serene shot of a sunset accompanied by Roy Orbison’s song “So Young”. In both Zabriskie Point and The Last Summer, there is at play an intriguing undertone which gives a melancholic if not pessimistic touch to the seemingly happy end; it is a pessimism for the death of dreams as well as the loss of youth. If the protagonist of Zabriskie Point wakes up, the protagonist of The Last Summer might fall asleep, but regardless both films share a similar darker undertone as if saying that neither really mattered.

In order to appreciate this undertone, it might be beneficial to take a closer look at the film’s two last shots. The first of these is a dynamic shot where the camera tracks slowly forward to Rikola’s face as he stands by the open door of the president’s residence after deciding to give up on the assassination plan. Next to his face is a window’s curtain waving due to a mild breeze as if concealing him into the tranquility of dreams. The second of these shots, that is, the final shot of the film, is a static shot, a long shot, where Rikola is seen crossing the bridge almost as a mere silhouette due to nightfall. The bridge is, of course, the same bridge where Rikola and Gawan tried to kill the president but failed and thus established the relationship Rikola subsequently developed with the president. Another bridge is seen during the opening credits of the film as Rikola arrives to the town by train. This feeling of arrival and beginning surely ties into the final shot, thus working as a narrative seal, but it most obviously associates with the key scene where Rikola and Gawan attempt to assassinate the president. The failure is due to Rikola’s unconscious (or subconscious, your choice) desire not to kill which manifests itself as his love for Jessika, a token of his respect for humanity which eventually prevents him from killing the president even when he has a gun targeted straight to the man’s head during the intense duck hunting sequence. The bridge is the place where new connections emerge. The accolades granted to Rikola by the president are but the first seeds of his ever-growing guilt. This guilt is, in part, due to the double meaning of the place: something new begins there while something utterly different was supposed to begin. It is an ambiguous place of both failure and success.

Now the question arises: what does the crossing of the bridge in the end mean? One answer, in line with the first interpretation presented above, is that Rikola outdoes himself and crosses the gulf of his own naive radicalism. Another, in line with the third interpretation, is that Rikola steps into the middle ground between liberalism and conservatism where the president proclaims to reside in. Finally, in line with the second pessimistic interpretation, one could argue that Rikola’s gesture of crossing the bridge is nearly suicidal, an identification with destruction and oblivion. He has, after all, just lost everything: the budding intellectual connection to the president, his friend Gawan and the respect of Gawan’s wife, his self-respect for that matter, and, of course, the love of his life, Jessika who simply cannot get over the fact that Rikola was planning the assassination of her father while their romance was starting to blossom. The act of crossing the bridge is the act of leaving. Rikola leaves the town, and in that sense everything, behind. Perhaps he goes back to the university where he is studying law. He returns from his summer vacation. He leaves this one summer behind, a summer which was, of course, something more than any other summer; it was, just as grim as it sounds, the last summer.

When it comes to the subject matter and especially the milieu of The Last Summer, the film could be seen as a critical comment on the genre of Heimatfilm. Heimatfilme were a series of films produced in Germany from the late 40′s to the late 60′s which were characterized by sentimentality, conservative values, and formulaic love triangle narratives where a “good boy” wins the girl from a “bad boy”. Many national cinemas have showed signs of a similar genre, modified for the characteristics of that nation, which bloomed around the same time, but Heimatfilm might be the best known internationally, perhaps due to ridicule, perhaps due to critical commentary. What is interesting about The Last Summer with regards to the genre of Heimatfilm is that the group of the Oberhausen manifesto as well as the New German Cinema, which took shape around that group essentially, criticized Heimatfilme very strongly and some of their films have been seen as taking a critical stance toward Heimatfilme. Now, both of those groups are also responsible for the oblivion surrounding the era of postwar German cinema in general in a fashion similar to the way French New Wave buried the postwar French cinéma de qualité under its own innovation. I would not be surprised if Braun’s The Last Summer had dropped into the category of Heimatfilm in the eyes of the new German filmmakers, but the intriguing thing is that The Last Summer is essentially a very subtle and mature criticism of Heimatfilm and its lack of moral ambiguity. The film addresses profound moral as well as romantic or human questions which become more complex than those in Heimatfilme, but this address takes place in a similarly idyllic environment which thus, in a sense, is elevated into a higher level of critical discourse.

Already by its very title, Braun’s The Last Summer seems to declare opposition toward Heimatfilm, or homeland films of the summer. It is about leaving the summer behind in the sense that the summer captures not only Heimatfilm but also youth, naivety of dreams, and perhaps even a radical or reformative ideology. Like in Zabriskie Point, there is something deeply melancholic about this departure from the summer of dreams, the faith in humanity, which seems to have something to do with aging and death. It is as if The Last Summer came across as the summer film to end all summer films whose summers might never have really existed in the first place.

Notes:

[1] This is Peter Lorre’s Der Verlorene (1951)

[2] These are, in chronological order, Der letzte Sommer (1954, Braun), So war der deutsche Landser (1955, Baumeister), Der 20. Juli (1955, Harnack), Das dritte Geschlecht (1957, Harlan), Wir Wunderkinder (1958, Hoffmann), Das Mädchen Rosemarie (1958, Thiele), Rose Bernd (1958, Staudte), Der Rest ist Schweigen (1959, Käutner), Am Galgen hängt die Liebe (1960, Zbonek), Kirmes (1960, Staudte), and Das Spukschloss im Spessart (1960, Hoffmann).

1 note

·

View note

Text

When, If Not Now?

When, If Not Now?

by Dr.Harald Wiesendanger– Klartext

Background journalism instead of court reporting.

Independent. Uncomfortable. Incorruptible.

When, if not now?

First Great Britain. Then Denmark. Now Norway too. In Europe, more and more countries are lifting all corona restrictions. Sweden did not even copy Red China’s hygiene staging of Wuhan, which tends to fall under the category of “ruse of war.” But a…

View On WordPress

#Andreas Gassen#Boris Johnson#Corona#Corona-measures#Corona-restrictions#Corona-Rules#Daniel Grein#Erna Solberg#Erwin Rüddel#Eugen Brysch#flatten the curve#freedom day#Geir Bukholm#Harald Wiesendanger#Heiko Maas#Helge Braun#Impfquote#Inzidenz#Janosch Dahmen#Jens Spahn#Karl Lauterbach#lockdown#Magnus Heunicke#mask compulsory#overload of the health system#pandemic#R-Wert#Stephan Hofmeister#Wolfgang Kubicki

0 notes

Photo

HERBSTLICHE WEGE

Des Sommers weiße Wolkengrüße

zieh'n stumm den Vogelschwärmen nach,

die letzte Beere gärt voll Süße,

zärtliches Wort liegt wieder brach.

Und Schatten folgt den langen Wegen

aus Bäumen, die das Licht verfärbt,

der Himmel wächst, in Wind und Regen

stirbt Laub, verdorrt und braun gegerbt.

Der Duft der Blume ist vergessen,

Frucht birgt und Sonne nun der Wein

und du trägst, was dir zugemessen,

geklärt in deinen Herbst hinein.

(Joachim Ringelnatz)

Bild: by Harald Gjerholm on flickr - Oktober Morning

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eSexGB94A-I

#vater braucht eine frau#harald braun#1952#ruth leuwerik#bruni löbel#therese giehse#dieter borsche#kvinnodröm#ingmar bergman#about photography#otto#dittsche#immenhof#träumerei#nora#frühlingssinfonie

0 notes

Text

Maria Schell-Hardy Krüger "Mientras estés a mi lado" (Solange du da bist) 1953, de Harald Braun.

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Organic Figure by Harald J. Braun

0 notes

Text

TOP 2020

25/12/2020

A) Great movies made since 2015 seen for the first time in 2020:

Buoyancy(Freedom;Rodd Rathjen, 2019)

Les choses qu’on dit, les choses qu’on fait(Emmanuel Mouret, 2020)

L’Île au trésor(Guillaume Brac, 2018)

Le Sel des larmes(Philippe Garrel, 2019/20)

Ghawre Bairey Aaj(Home and the World;Aparna Sen, 2019)

Undine(Christian Petzold, 2020)

Happī awā(Happy Hour;Hamaguchi Ryūsuke, 2015)

Netemo Sametemo(Asako I & II;Hamaguchi Ryūsuke, 2018)

Adolescentes(Sébastien Lifshitz, 2013-9/20)

Family Romance, LLC.(Werner Herzog, 2019)

Demain et tous les autres jours(Noémie Lvovsky, 2017)

Gamak Ghar(Achal Mishra, 2019)

Lunana:A Yak in the Classroom(Pawo Choyning Dorji, 2019)

Semina il vento(Sow the Wind;Danilo Caputo, 2020)

Objector(Molly Stuart, 2019)

La France contre les robots(Jean-Marie Straub, 2020)

Paris Calligrammes(Ulrike Ottinger, 2019/20)

Un film dramatique(Éric Baudelaire, 2019)

B) Great movies made before 2015 seen for the first time in 2020:

Là-Haut, un Roi au-dessus des nuages(Pierre Schoendoerffer, 2003)

Pangarap ng Puso(Demons/Whispers of the Demon/Hope of the Heart;Mario O’Hara, 2000)

Les Films rêvés(Eric Pauwels, 2009)

La vida en rojo(Andrés Linares, 2007/8)

Come Next Spring(R.G. Springsteen, 1955/6)

Song of Surrender(Mitchell Leisen, 1948/9)

Adventure in Manhattan(Edward Ludwig, 1936)

Strannaia zhenshchina(A Strange Woman;Iuli Raízman, 1978)

Chastnaia zhízn(Private Life;Iuli Raízman, 1982)

Málva(Vladimir Braun, 1956/7)

Zhila-byla devochka(Once There Was a Girl;Viktor Eisimont, 1944)

The Unknown Man(Richard Thorpe, 1951)

Aisai Monogatari(Story of a Beloved Wife;Shindō Kaneto, 1951)

Practically Yours(Mitchell Leisen, 1944)

A Summer Storm(Robert Wise, 1999/2000)

Lettre d’un cinéaste à sa fille(Eric Pauwels, 2000)

Sombra verde(Untouched;Roberto Gavaldón, 1954)

Fantasma d’amore(Dino Risi, 1981)

Adieu, Mascotte(Das Modell vom Montparnasse;Wilhelm Thiele, 1929)

Mori no kajiya(The Blacksmith of the Forest;Shimizu Hiroshi, 1928/9;fragment)

Zwischen Gestern und Morgen(Between Yesterday and Tomorrow;Harald Braun, 1947)

Last Holiday(Henry Cass, 1950)

Dialogue d’ombres(Danièle Huillet & Jean-Marie Straub, 1954-2013)

Out-Takes from the Life of a Happy Man(Jonas Mekas, 2012)

Nice Time(Claude Goretta & Alain Tanner, 1957)

Aloma of the South Seas(Alfred Santell, 1941)

A Feather in Her Hat(Alfred Santell, 1935)

La Danseuse Orchidée(Léonce Perret, 1928)

Underground(Vincent Sherman, 1941)

Time Out(in Twilight Zone-The Movie)(John Landis, 1983)

Lackawanna Blues(George C. Wolfe, 2005)

Janie(Michael Curtiz, 1944)

Dernier Amour(Léonce Perret, 2016)

Jeunes Filles en détresse(Georg Wilhelm Pabst, 1939)

Kisapmata(Blink of an Eye;Mike De Leon, 1981)

La Dernière Lettre(Frederick Wiseman, 2002)

The Lady of the Dig-Out(W.S. Van Dyke II, 1918)

Their Own Desire(E.Mason Hopper, 1929)

C) Very good movies made since 2015 seen for the first time in 2020:

Zumiriki(Oskar Alegria, 2019)

Atlantique(Mati Diop, 2019)

J’accuse(An Officier and A Spy;Roman Polanski, 2019)

Richard Jewell(Clint Eastwood, 2019)

Alice et le Maire(Nicolas Pariser, 2019)

Contes de Juillet(July Tales;Guillaume Brac, 2017)

Dark Waters(Todd Haynes, 2019)

Ofrenda a la tormenta(Fernando González Molina, 2020)

Nomad:In the Footsteps of Bruce Chatwin(Werner Herzog, 2019)

Into the Inferno(Werner Herzog, 2016)

The Zookeeper’s Wife(Niki Caro, 2017)

Journal de septembre(Eric Pauwels, 2019)

La Deuxième Nuit(Eric Pauwels, 2016)

Kaze no denwa(Voices in the Wind;Suwa Nobuhiro, 2019/20)

Da 5 Bloods(Spike Lee, 2020)

Izaokas(Isaac;Jurgis Matulevičius, 2019)

A Metamorfose dos Pássaros(Catarina Vasconcelos, 2020)

Tabi no Owari Sekai no Hajimari(To the Ends of the Earth;Kurosawa Kiyoshi, 2019)

La Nuit d’avant(Pablo García Canga, 2019)

My Mexican Bretzel(Nuria Giménez, 2018-9)

Domangchin yeoja(The Woman Who Ran;Hong Sang-soo, 2019/20)

Öndög(Wang Quanan, 2019)

Hatsukoi(First Love;Miike Takashi, 1959)

Million raz pogivaet odin Cheloviek(One man dies a million times;Jessica Oreck, 2018/9)

The Two Popes(Fernando Meirelles, 2019)

Félicité(Alain Gomis, 2016/7)

Salt and Fire(Werner Herzog, 2016)

Ni de lian(Your Face;Tsai Ming-liang, 2018)

Qi qiu(Balloon;Pema Tseden, 2019)

River Silence(Rogério Soares, 2019)

Charlie’s Angels(Elizabeth Banks, 2019)

La boda de Rosa(Iciar Bollain, 2020)

Guerra(War;José Oliveira & Marta Ramos, 2020)

My Thoughts Are Silent/Moyi dumky tykhi(Antonio Lukich, 2019)

Namo(The Alien;Nader Saeivar;co-script-Jafar Panahi, 2020)

Los silencios(The Silences;Beatriz Seigner, 2018)

Terminal Sud(Rabah Ameur-Zaïmeche, 2019)

Tu mérites un amour(You Deserve a Lover;Hafsia Herzi, 2019)

Les Misérables(Ladj Ly, 2019)

Padre no hay más que uno(Santiago Segura, 2019)

Honeyland(Tamara Kotovska & Ljubomir Stefanov, 2019)

Izbrisana(Erased;Miha Mazzini & Dusan Joksimovic, 2018)

This Is Not A Burial, It’s A Resurrection(Lemohang Jeremiah Mosese, 2019)

Primero Enero(Darío Mascambroni, 2016)

Lahi, Hayop(Pan, Genus/Genus Pan;Lav Diaz, 2020)

D) Very good movies made before 2015 seen for the first time in 2020:

Topaze(Marcel Pagnol, 1936)

The SIGN OF THE RAM(John Sturges, 1947/8)

Abandoned(Joseph M. Newman, 1949)

Bewitched(Arch Oboler, 1944/5)

La Femme du Bout du Monde((Jean Epstein, 1937)

The Outcast(William Witney, 1954)

Saadia(Albert Lewin, 1953)

Un monde sans femmes(Guillaume Brac, 2011)

Dishonored Lady(Robert Stevenson, 1947)

Always Goodbye(Signey Lanfield, 1938)

A Blueprint for Murder(Andrew L. Stone, 1953)

Bedevilled(Mitchell Leisen, 1955)

That Forsyte Woman(Compton Bennett, 1949)

The Miracle(Irving Rapper, 1959)

The Madonna’s Secret(Wilhelm Thiele, 1946)

The Town That Dreaded Sundown(Charles B. Pierce, 1976)

Grayeagle(Charles B. Pierce, 1977)

Barricade(Peter Godfrey, 1949/50)

Tomorrow is Forever(Irving Pichel, 1945/6)

David Harum(James Cruze, 1934)

The Vanquished(Edward Ludwig, 1953)

Keisatsukan(Uchida Tomu, 1933)

...Enfants des courants d’air(Édouard Luntz, 1959, short)

The Winds of Autumn(Charles B. Pierce, 1976)

Suddenly It’s Spring(Mitchell Leisen, 1946)

Uchūjin Tōkyō ni arawaru(Warning from Space;Shima Kōji, 1956)

Swiss Family Robinson(Edward Ludwig, 1940)

Ludwig der Zweite, König von Bayern(Wilhelm Dieterle, 1930)

Faithless(Harry Beaumont, 1932)

Botan-dorō(Peony Lanterns;Yamamoto Satsuo, 1968)

Ginza 24 chou(Tales of Ginza;Kawashima Yūzō, 1955)

Goodbye Again(Michael Curtiz, 1933)

Lines of White on a Sullen Sea(D.W. Griffith, 1909)

You Gotta Stay Happy(H.C. Potter, 1948)

Cave of Forgotten Dreams(Werner Herzog, 2010)

Riff-Raff(Ted Tetzlaff, 1947)

The Moon is Down(Irving Pichel, 1943)

The Bride Wore Boots(Irving Pichel, 1946)

Adventures in Silverado(Phil Karlson, 1948)

The Stolen Ranch(William Wyler, 1926)

Congo Maisie(H.C. Potter, 1940)

Marcides(Mercedes;Yousry Nasrallah, 1993)

Hell’s Five Hours(Jack L. Copeland, 1958)

Daniel(in Stimulantia;Ingmar Bergman, 1967)

Diên Biên Phú(Pierre Schoendoerffer, 1992)

Canyon River(Cattle King;Harmon Jones, 1956)

Dos Basuras(Kurt Land, 1958)

Smart Girls Don’t Talk(Richard L. Bare, 1948)

The Big Shakedown(John Francis Dillon, 1933/4)

Corvette K-225(Richard Rosson;p.,collab.Howard Hawks, 1943)

The Gay Deception(William Wyler, 1935)

The Invisible Woman(A.Edward Sutherland, 1940)

Rage in Heaven(W.S. Van Dyke II;collab.Robert B. Sinclair,Richard Thorpe, 1941)

Wild Side(Sébastien Lifshitz, 2004)

I bambini e noi(Luigi Comencini, 1970//7)

The House Across The Street(Richard L. Bare, 1948/9)

The Doughgirls(James V. Kern, 1944)

The Love Trap(William Wyler, 1929)

Torch Song(Charles Walters, 1953)

The Meanest Man in the World(Sidney Lanfield, 1942/3)

Cole Younger, Gunfighter(R.G. Springsteen, 1958)

Ballerine(Gustav Machatý, 1936)

Via Mala(Josef von Báky, 1945//8)

Sky Giant(Lew Landers, 1938)

Les Invisibles(Sébastien Lifshitz, 2012)

Promène toi donc tout nu(Emmanuel Mouret, 1998)

A Story for the Modlins(Una historia para los Modlin;Sergio Oksman, 2012)

Something in the Wind(Irving Pichel, 1947)

Spoveď(Confession;Pavol Skýkova, 1968)

Guilty Hands(W.S. Van Dyke II;collab.Lionel Barrymore, 1931)

Atto di accusa(Giacomo Gentilomo, 1950)

Suspense(Frank Tuttle, 1956)

This Is The Night(Frank Tuttle, 1932)

Escape in the Fog(Oscar ‘Budd’ Boetticher,Jr., 1945)

The Price of Fear(Abner Biberman, 1956)

Happy People:A Year in the Taiga(Werner Herzog, 2010)

Urok(The Lesson;Kristina Grozeva & Petar Valchanov, 2014)

Le Naufragé(Guillaume Brac, 2009)

Lili Marlen(Peter Mihálik;script.Dušan Hanák, 1970;short)

Deseo(Antonio Zavala Kugler, 2013)

E) Great movies that improved by new watchings:

Shanghai Express(Josef von Sternberg, 1932)

The Best Years of Our Lives(William Wyler, 1946)

Till We Meet Again(Frank Borzage, 1944)

Man’s Favorite Sport?(Howard Hawks, 1963/4)

Along The Great Divide(Raoul Walsh, 1951)

Hondo(John V. Farrow, 1953)

Where The Sidewalk Ends(Otto Preminger, 1950)

Mrs. Miniver(William Wyler, 1942)

Driftwood(Allan Dwan, 1947)

‘Good-bye, My Lady’(William A. Wellman, 1956)

Touch of Evil(Preview version, 1975;not later ‘improvements’)(Orson Welles, 1958)

Le Crabe-Tambour(Pierre Schoendoerffer, 1977)

Unfinished Business(Gregory LaCava, 1941)

Madigan(Don Siegel, 1968)

Big Business(James Wesley Horne;s.Leo McCarey, 1929)

Putting Pants on Philip(Clyde A. Bruckman;s.Leo McCarey, 1927)

The Runner Stumbles(Stanley Kramer, 1979)

Yushima no Shiraume(Romance at Yushima;Kinugasa Teinosukē, 1955)

David Harum(Allan Dwan, 1915)

The Virginian(Cecil B. DeMille, 1914)

Island in the Sky(William A. Wellman, 1953)

All About Eve(Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1950)

L’Eclisse(Michelangelo Antonioni, 1962)

The Roaring Twenties(Raoul Walsh, 1939)

The Plainsman(Cecil B. DeMille, 1936)

JLG/JLG-Autoportrait de décembre(Jean-Luc Godard, 1994)

‘Je vous salue, Marie’(Hail Mary;Jean-Luc Godard, 1984)

La Roue(Abel Gance, 1923)

They All Laughed(Peter Bogdanovich, 1981)

Innocent Blood(John Landis, 1992)

An American Werewolf in London(John Landis, 1981)

The Thing Called Love(Peter Bogdanovich, 1993)

Into the Night(John Landis, 1985)

The File On Thelma Jordon(Thelma Jordon;Robert Siodmak, 1949)

The Little American(Cecil B. DeMille, 1917)

In Our Time(Vincent Sherman, 1944)

The Hunters(Dick Powell, 1958)

Phase IV(Saul Bass, 1974)

L’Honneur d’un Capitaine(Pierre Schoendoerffer, 1982)

Backfire(Vincent Sherman, 1948//50)

Five(Arch Oboler, 1951)

Somewhere in the Night(Joseph L. Mankiewiz, 1946)

A Man Alone(Ray Milland, 1955)

Die Geiger von Florez(Paul Czinner, 1926)

Living on Velvet(Frank Borzage, 1934/5)

La Recta provincia(Raúl Ruiz, 2007//15)

La Noche de enfrente(Raúl Ruiz, 2012)

Carrie(Sister Carrie;William Wyler, 1951/2)

The Spiral Staircase(Robert Siodmak, 1945/6)

The Paradine Case(Alfred Hitchcock, 1947)

L’Amore(Una voce umana+Il Miracolo)(Roberto Rossellini, 1947/8)

The Heiress(William Wyler, 1949)

F) Very good movies watched again

Bluebeard’s 10 Honeymoons(W.Lee Wilder, 1960)

The Five Pennies(Melville Shavelson, 1958)

Take a Letter, Darling(Mitchell Leisen, 1942)

Escape(Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1948)

Appassionatamente(Giacomo Gentilomo, 1954)

Así como habían sido(Trío)(Andrés Linares, 1986/7)

San Antone(Joseph Kane, 1953)

The High and the Mighty(William A. Wellman, 1954)

Taki no Shiraito(The Water Magician;Mizoguchi Kenji, 1933)

The Web(Michael Gordon, 1947)

The Buccaneer(Anthony Quinn;s.Cecil B. DeMille, 1958)

The Buccaneer(Cecil B. DeMille, 1938)

Desire Me(uncredited:George Cukor/Jack Conway/Mervyn LeRoy/Victor Saville, 1946)

Flaxy Martin(Richard L. Bare, 1948/9)

Swing High, Swing Low(Mitchell Leien, 1937)

Death Takes A Holiday(Mitchell Leisen, 1934)

Irene(Herbert Wilcox, 1940)

Beloved Enemy(H.C. Potter, 1936)

The Cowboy and the Lady(H.C. Potter, 1938)

Der Golem, wie er in die Welt kam(Paul Wegener, 1920)

Mia madre(Nanni Moretti, 2015)

Hell On Frisco Bay(Frank Tuttle, 1955)

Stormy Weather(Andrew L. Stone, 1943)

The Milky Way(Leo McCarey;w.Harold Lloyd, 1936)

Pietà per chi cade(Mario Costa, 1954)

Repeat Performance(Alfred L. Werker, 1947)

Das indische Grabmal:1.Die Sendung des Yoghi,2.Der Tiger von Eschnapur(Joe May, 1921)

Julie(Andrew L. Stone, 1956)

The Member of the Wedding(Fred Zinnemann, 1953)

Winterset(Alfred Santell, 1936)

The Right to Romance(Alfred Santell, 1933)

As Young as You Feel(Harmon Jones, 1951)

You’ll Never Get Rich(Sidney Lanfield, 1941)

The Woman Accused(Paul Sloane, 1933)

Foma Gordeiev(Mark Donskoí, 1959)

The Parent Trap(David Swift, 1961)

High Wall(Curtis Bernhardt, 1947)

Mr. Lucky(H.C. Potter, 1943)

Un Marido de Ida y Vuelta(Luis Lucia, 1957)

The Safecracker(Ray Milland, 1957/8)

She’s Funny That Way(Peter Bogdanovich, 2014)

Oh...Rosalinda!!(Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger, 1955)

Caribbean(Edward Ludwig, 1952)

Harper(The Moving Target;Jack Smight, 1966)

For You I Die(John Reinhardt, 1947)

Crashing Hollywood(Lew Landers, 1937/8)

Le Souvenir d’un avenir(Chris. Marker & Yannick Bellon, 2001)

Susan Slept Here(Frank Tashlin, 1954)

Bishkanyar Deshot(In the Land of Poison Women;Manju Borah, 2019)

Pollyanna(David Swift, 1960)

A Tale of Two Cities(Jack Conway;collab.Val Lewton & Jacques Tourneur, 1935)

Café Society(Woody Allen, 2016)

Shadow on the Wall(Patrick Jackson, 1949/50)

Tonnerre(Guillaume Brac, 2013)

Le Jouet criminel(Adolfo G. Arrieta, 1969)

‘Once more, with feeling!’(Stanley Donen, 1959)

The Shopworn Angel(H.C. Potter, 1938)

The Absent Minded Professor(Robert Stevenson, 1961)

Gavaznha(The Deer;Masud Kimiai, 1974)

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

skate park, Munich [Harald Braun]

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

20 Inventions of all time.

Introduction

Since the time primordial man first picked up a rock and thwacked a scurrying rodent on its head to fix his dinner, mankind has always been inventing things. Improvising, innovating, crafting tools out of almost nothing to overcome the many difficulties of day-to-day life. Whether it was the rudimentary spear crafted by sharpening the end of a stick or much later a simple chair, inventions have shaped our very evolution.

Before you get worried we’ll assure you we’ve not gone that far back in time.

The inventions we’ve covered span core-science aeronautics, biology, physics, medicine, automobiles, electronics and of course technology. We’ve avoided things like “fire” or “the wheel” because quite frankly no one really knows how the former was discovered (not invented) and who invented the latter.

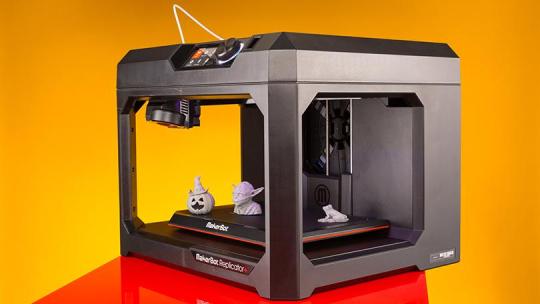

1.3D Printers

The 3D Printer is one of the greatest inventions of the 21st century allowing you to turn your ideas into real objects.

The latest Bond movie, Skyfall used a 3D printer from a German company called Voxeljet to produce three 1:3 scaled models of 007’s Aston Martin just to blow up during the movie!

What sounds like a really cool toy to have is actually used for some very serious operations. Let’s first understand how it works.

3D printing is achieved using an additive process in which successive layers of materials are laid out in different shapes. Cutting and drilling (also known as subtractive processes) are not involved at all making the process easy, efficient and highly suitable for prototyping.

The biggest consumer of the 3D Printer is the medical industry. So far it has produced prosthetics and bones and the ability to generate human

organs from these machines is currently being tried out. If this is managed, it could revolutionize medicine and completely obliterate the need for organ donation. Using a 3D printer in conjunction with CAT scans, surgeons can print out tumours so that they know exactly what they’re dealing with.

We’re sure you’re familiar with Pirate Bay, the file sharing company. It has launched a new content category called ‘Physibles’ i.e. data objects that can be made into physical products. 3D blueprints are uploaded and shared with those who want to print out the actual objects.

2. Airplane

The Wright brothers are given credit for the invention of the Airplane in 1903. The first flight lasted a little over 12 seconds at Kill Devil Hill, Northern Carolina. Since then, much progress has been made in the world of aviation. The sky wasn’t the limit here. War and sci-fi stories inspired great minds like Konstantin Tsiolkovsky and Werner von Braun to achieve flight beyond the atmosphere, making space travel a possibility.

The invention of the airplane sped up services in every single field starting with the postal service in 1920. World War II in 1939 kick-started developments in the aviation sector. Countries competed with each other to one-up the others’ sophisticated developments, with the British developing the airplanedetecting radar followed by the Germans developing radio wave navigation techniques. Fighter jets, advanced landing systems and high altitude aircrafts followed.

In 1947, US Air Force Pilot Captain Charles Yeager broke the sound barrier in the first supersonic flight becoming the fastest man alive.

Commercial flights started not long after and now, well, an airplane makes a landing somewhere around the world every three seconds!

Air travel is considered to be the safest form of travel in the world. A funny but true fact reveals that donkeys kill more people annually than plane crashes. Inspite of these phenomenal odds, 80% of the population of the world has Aerophobia, viz fear of flying. In some (5%) this fear is so intense that they abandon flights and opt for other modes of transport.

We’ve come a long way since 1903. In fact the wingspan of a Boeing 747 is longer than the Wright brothers’ first flight! The world today would be crippled without the discovery of flight. Businesses would crash, economies would slow down, worse still, holidays would be cancelled!

3.Artificial Intelligence

AI could be on either end of two extremes – man’s best invention or worst. In its best light, Artificial Intelligence would showcase robots, drones, machines serving us making daily life easier and more efficient or, as seen in movies, taking over the human race and entirely replacing the work force leading to unemployment, depression and general laziness.

The study of Artificial Intelligence formally began in Dartmouth College in 1956, as an effort by a group of research scientists to evaluate and mechanically replicate human intelligence. That is, they wanted to program machines to think and respond like humans. Their research was based on the assumption that a machine can be made to simulate learning, reasoning, logic and intelligence demonstrated by humans when given proper description and direction.

Every future invention by man will have its base in AI. Every invention will require an intelligently thinking bot to perform tasks faster and more efficiently than their human counterparts.

Essay grading software, weapons that have minds of their own, Siri by Apple, Kinect the 3D gaming interface, Watson by IBM – formerly a trivia expert machine now used to make decisions on lung cancer treatment and smart CCTVs that can identify crime as it happens: these are the varied and most advanced productions of AI.

4.Biometric Scanners

Biometrics – turning yourself into an identity card. No need for passwords, ids, pin numbers, etc. All you need is you. It’s a move from traditional access control systems to feature-based authentication that provides access based on physical presence rather than token (such as passport or drivers license) and knowledge based (password or PIN) methods.

With advancements in e-commerce and e-transactions, individuals have to retain a large number of passwords, PINs and identity cards. This number will only grow in size with passing time. Passwords and PINs are easy to crack by the right hacker, thus compromising your security. Biometrics couldn’t have come at a better time offering the ideal kind of security since no two fingerprints are alike.

The use of Biometric Scanners could unleash an era of super secure gadgets. It is already being used in cars programmed to operate only when a known driver is in the driver’s seat, weapons which fire only on detecting the owner’s fingerprints and smart household security systems that keep intruders out, among other applications. Not only fingerprints, facial scanning biometric devices are also not rare. Take the Samsung Galaxy S III for example. It has a Face Unlock feature which makes sure that only its owner can unlock the phone.

Fingerprint scanners are the cheapest and hence most commonly used biometric devices. Face and voice recognition follow, as iris and retinal scanning are concepts that most people find intrusive and are not too comfortable using.

The invention of Biometric Scanners was a big step into the future. They’ve led to the creation of the ultimate unique identifiers – those that cannot be forgotten, changed or lost.

5.Bluetooth

A wireless technology used to exchange data over short distances using short-wavelength radio transmission, Bluetooth was created by Ericsson in 1994 as an alternative to data cables. The term “Bluetooth” is an anglicized version of Blatand, the epithet of 10th century Danish king Harald who united separated Danish tribes into a single kingdom. The technology was named after him as Bluetooth does what Blatand did but with communications protocols – unites them into one universal standard.

Since its introduction, Bluetooth has increased in popularity over the years – while in 2008, only 5% of mobile devices were Bluetooth-enabled, in 2013, roughly 95% of mobile devices support it. Also, while traditional Bluetooth devices only worked within a range of 10 feet of each other the newest versions now enable transfers to a distance of up to 100 feet. However, what makes Bluetooth stand out as a form of wireless data transfer is that it uses very little power, can be incorporated into a wide variety of devices and can have up to eight devices communicating with each other at once and automatically without a user’s prompt.

Coming soon (15 more)

1 note

·

View note