#having a sense of catharsis knowing the character they liked growing up was representing them all along :)

Text

ik this had to have been such a massive W for the neurodivergent/autistic chicanos out there when this was announced

#i think it's so cool how manny a staple of iconic 2000s action cartoons was a brown autistic boy#i can't imagine how many other mexicans who likely felt similar to jorge getting diagnosed later in adulthood and who grew up w the show#having a sense of catharsis knowing the character they liked growing up was representing them all along :)#esp given how the conversation surrounding autism and/or neurodivergency in mexican community is still v much stigmatized#in part bc anything related to seeking out resources for mental health (depression anxiety ptsd etc)#anyways yeah we love to see it#el tigre#robi rambles

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Tragic Hero Full of Fear

Hello everyone! Before I get into this, I’d like to thank @jasontoddiefor for both the name and being the main enabler of this fun piece of writing. I also want to thank all my wonderful friends over on Discord for letting me bounce ideas off of them and helping me. You are all amazing!!

Ok, so let’s get into it!

The first six Star Wars movies (the Original and Prequel trilogies) are commonly referred to as “the Tragedy of Darth Vader.” But what makes these movies a tragedy? How is Anakin Skywalker himself, the main character of said tragedy, a tragic hero? In this meta/essay, I will discuss how Anakin himself is definitionally a tragic hero and outline his story as it relates to the structure of a classic Greek tragedy.

This essay will focus solely on Anakin’s character as he is canonically portrayed.

The Hero

Let’s go through the main traits of a tragic hero (as per early literature) and discuss them in the context of Anakin Skywalker.

Possesses immense courage and strength and is usually favored by the gods

Anakin’s courage is evident throughout his entire life, such as when he participates in the pod race in TPM or on the front lines during the Clone Wars.

While we cannot definitively ascribe Anakin’s abilities to any deity, we can associate them with the Force. The Force is able to somewhat influence the happenings of the universe in certain ways and takes the place of any sort of deity.

Whether Anakin is the “Chosen One” or not, his connection to the Force is stronger than that of any other Force-sensitive being, so he is consequently closer to it than most, if not all, other Force-sensitive beings.

Extreme loyalty to family and country

Anakin is consistent in his demonstrations of loyalty to those he has strong feelings for (whether those feelings be romantic or platonic).

His devotion to Padmé surpasses his loyalty to the Jedi, and he is always willing to go to great lengths to ensure their safety and well-being.

Anakin also exhibits a strong sense of devotion to his mother, Shmi. His devotion to her, and by extension her wellbeing, surpasses his duties as Jedi.

In ROTS, Anakin says, “I will not betray the Republic… my loyalties lie with the Chancellor and with the Senate… and with you” (you, in this case, referring to Padmé). In this quotation, Anakin’s loyalties are made quite clear. At this point, he is not faithful to the Jedi, but to his government, its leaders, and, of course, his wife.

Representative of society’s current values

During the Clone Wars, Anakin is known by the moniker, “the Hero with No Fear,” and is one of the Republic’s “poster boys.” He is charismatic, kind, seemingly fearless (obviously) and a strong fighter, thus representing the values that were important to the Republic at the time. The last characteristic is especially important because of the assurance it instills in times of war. As a representation of the Republic, Anakin’s prowess on the battlefield creates hope for its citizens that victory is possible.

Anakin also empathizes with the opinion that the seemingly outdated Jedi Code holds them back. In the Citadel Arc, Tarkin remarks that “the Jedi Code prevents [the Jedi] from going far enough to achieve victory.” Anakin actually agrees with this statement, replying that “[he’s] also found that [the Jedi] sometimes fall short of victory because of [their] methods” (Season 3, Episode 19). He shows a sense of allegiance not to the ancient ways of the Jedi, but to the newer, more modern ideals regarding military action.

Anakin claims to have brought “peace, justice, freedom, and security” to his “new Empire.” While the Empire's interpretations of the aforementioned values are skewed, Anakin continues to represent them as Darth Vader.

Anakin’s statement to Obi-Wan also mirrors Palpatine’s declaration to the Senate: “In order to ensure our security and continuing stability, the Republic will be reorganized into the first Galactic Empire, for a safe and secure society which I assure you will last for ten thousand years.” The people applaud this statement, demonstrating a general sense of exhaustion in regards to the war and a yearning for what this new Empire is promising them.

Lead astray/challenged by strong feelings

Though there are many, many examples of Anakin’s emotions getting the better of him, we’re simply going to list two:

Anakin’s fury and anguish after the death of his mom leads to his slaughter of the Tuskens

Anakin’s overwhelming fear of losing Padmé is ultimately what leads to his Fall.

Every tragic hero possesses what is called a hamartia, or a fatal flaw. This trait largely contributes to the hero’s catastrophic downfall. Anakin’s hamartia is his need for control, which partially manifests through his fear of loss.

Let’s explore this idea in more detail.

Though Anakin grows up as a slave, the movies neglect to explicitly cover the trauma left from his time in slavery. However, it is worth noting that slaves did not have the ability to make many choices for themselves; they didn’t even own their bodies. After being freed, Anakin is whisked away to become a Jedi. He does not possess much control over his life as Jedi, for he is simply told what path he is going to take. While Anakin does make this decision on his own, becoming a Jedi is a disciplined and somewhat-strict way of life and not one that allows for an abundance of reckless autonomy as he is wont to engage in.

(Side note: I’m not here to argue about Qui-Gon’s decision-making abilities, nor do I wish to engage in discourse regarding the Jedi’s way of life. I am simply presenting and objectively stating these facts in relation to Anakin because they are pertinent to my point.)

During AOTC, Anakin is unable to save his mother from death. As Shmi dies in his arms, Anakin is absolutely helpless. The situation is completely out of his control, and he is forced to contend with the reality that despite all of his power, he cannot control everything that happens.

He also feels that he has a larger potential for power and is being held back by Obi-Wan: “although I'm a Padawan learner, in some ways... a lot of ways... I'm ahead of him. I'm ready for the trials. I know I am! He knows it too. He believes I'm too unpredictable… I know I started my training late... but he won't let me move on.” Anakin believes Obi-Wan, his teacher and mentor, is holding him back. He expresses a self-held conviction of his status and skills and does not trust the word of his superior.

In ROTS, Anakin starts dreaming of Padmé’s death. Considering what occurred the last time he dreamt of a loved one’s demise, Anakin is justifiably (or at least justifiably from his point of view) worried. He consequently wants to stop these dreams from coming true in any way possible. His fear of death, especially that of his loved ones, represents his need for control over everything, even things that are uncontrollable. This overwhelming desire leads to Anakin’s drastic actions.

As Darth Vader, he no longer possesses such fears, for everyone that he loved is either dead or has betrayed him. He is the epitome of order and control, eliminating any who disturb this perceived equilibrium.

However, this changes because of one person: Luke Skywalker.

Luke reintroduces something that was (arguably) long-absent in Vader’s life, which is interpersonal attachment. Vader yearns for his son to join him by his side. When Luke refuses, Vader continues to attempt to seek him out. In ROTJ, Vader is forced to choose between the Emperor, a man he has long trusted and followed, and Luke, the son he never knew he had. Out of a desire to protect and keep what little family he has left (and likely a sense of “I couldn’t save Padmé but at least I can save her legacy by keeping her child(ren) alive and safe”), Vader defeats the Emperor and saves his son. Though his actions are definitionally heroic, Anakin never truly overcomes his hamartia.

The Structure of a Tragedy

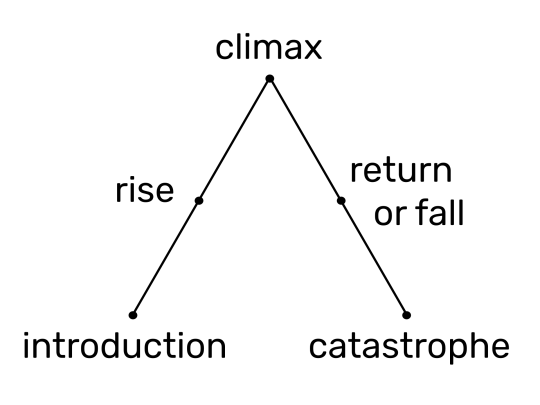

Classic Greek tragedies follow a specific story structure, which, according to the German playwright Gustav Freytag, is as follows:

We’re going to focus on the three aspects that best represent Anakin’s story as a tragedy: The peripeteia, the anagnorisis, and the catastrophe/denouement. These occur during and/or after the climax.

The peripeteia is the climax/the turning point in the plot. Said change usually involves the protagonist's good luck and prosperity taking a turn for the worse.

Within the tragedy we are discussing, the peripeteia occurs when Anakin chooses Sidious over Mace Windu and solidifies his allegiance to the Dark side, becoming the very thing he swore to destroy. It is at this point that things really start to go downhill. He kills children, chokes his wife, fights his best friend, gets his remaining limbs cut off, etc.

The anagnorisis is the point in the tragedy when the protagonist recognizes their error, seeing the true nature of that which they were previously ignorant of, usually regarding their circumstances or a specific relationship (such as Oedipus’ realization that his wife was actually his mother). In most tragedies, the anagnorisis is in close proximity to the peripeteia. In Anakin’s story, the anagnorisis occurs during ROTJ. After being wounded in his fight against Luke, Vader watches as his son is brutally electrocuted by Sidious. It is at this moment that Darth Vader realizes that Luke was right—there is good in him, and he still has the chance to redeem himself.

The catastrophe/denouement (since this is a tragedy, we’re going to go with “catastrophe”) is the end of the tragedy. Events and conflicts are resolved and brought to a close, and a new sort of “normality” is established. The catastrophe often provides a sense of catharsis (release of tension) for the viewer. The protagonist is worse off than they were at the beginning of the tragedy.

The catastrophe within “The Tragedy of Darth Vader” transpires soon after the anagnorisis at the end of ROTJ. Though the realization of his capacity for good is the anagnorisis, the follow-through (via his actions), as well as what consequently occurs, is the catastrophe. As previously discussed, Vader saves Luke by killing the Emperor but does so at the cost of his own life. This serves as the resolution of the tragedy, for the hero’s fate has been confirmed—Darth Vader fulfills his destined role as the Chosen One and, in doing so, brings about his own redemption and dies as Anakin Skywalker.

In conclusion, the categorization of Star Wars as a tragedy is a choice that heavily influences Anakin, the protagonist and hero, of the story. He is without a doubt a tragic hero whose fatal flaw leads to his downfall. In accordance with Aristotle’s theory of tragedy, Anakin’s tragedy is constructed not by personal agency, but by the narrative itself.

Works Cited

“Darth Vader.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 15 Mar. 2021, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Darth_Vader.

“Dramatic Structure.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 20 Feb. 2021, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dramatic_structure.

“Hero.” Encyclopaedia Britannica, Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., 19 Oct. 2016, www.britannica.com/art/hero-literary-and-cultural-figure.

Lucas, George, director. Star Wars: Episode III— Revenge of the Sith. Lucasfilm Ltd., 2005.

Lucas, George, director. Star Wars: Episode II— Attack of the Clones. Lucasfilm Ltd. , 2002.

Michnovetz, Matt. “Star Wars: The Clone Wars, ‘Counterattack.’” Season 3, episode 19, 4 Mar. 2011.

“Sophocles: the Purest Artist.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., www.britannica.com/art/tragedy-literature/Sophocles-the-purest-artist.

“Theory of Tragedy.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., www.britannica.com/art/tragedy-literature/Theory-of-tragedy.

“Tragic Hero.” Dictionary.com, Dictionary.com, www.dictionary.com/browse/tragic-hero.

#star wars#Anakin Skywalker#greek tragedy#anakin the tragic hero#meta#so many meta ideas not enough time#wow thanks tumblr formatting for being terrible

183 notes

·

View notes

Text

Burning as a Motif for Humanity in Violet Evergarden

I think, when watching Violet Evergarden, most of us picked up on fire as a motif for Violet’s trauma – the violence and destruction she witnessed in the war, and the violence and destruction she engendered with her own hands. I’m not going to go into this too much because it’s all pretty self-explanatory, if not trite, but here are some quick examples of fire as a motif for her trauma just to lay the groundwork for the rest of the essay:

In frame 1 (episode 8), Violet draws first blood on the battlefield, and the once contained fire from the felled soldiers’ lanterns spread quickly through the forest, a symbol for how one small act of violence can cascade into large scale destruction. In frame 2, Gilbert stares at the carnage in front of him, horrified. In frame 3, the major is shot, and all we get to see is a screen of flames. In frame 4 (episode 12), Merkulov stares into a fire as he schemes about re-kindling the war.

I want to follow this (well trodden) opinion up with a more encompassing statement. That is, fire, in Violet Evergarden, is not limited to representing the destructive power of violence and trauma. Instead, it is a motif for humanity itself – an embodiment of the full range of experiences and emotions that make us human.

To show this, I’m going to start off at the beginning of Violet’s journey, focusing on how her disconnect (from herself as well as others) is illustrated in episode one. For instance, her initial struggle to move her now mechanical arms as she sits in her hospital bed in the opening sequence is an excellent embodiment of her dissociation from her own body and lack of agency. I want to, however, focus on two scenes that are particularly relevant for our discussion:

First, the scene where Violet spills tea on her hand:

And second, the scene where Hodgins insists that Violet is burning:

These scenes are similar: in both, someone asserts that Violet must be in pain, specifically due to burning, and in both, Violet rejects that statement. In the first, however, that burning is physical. And in the second, that burning is emotional. Regardless, Violet is so removed from her own body that she is incapable of feeling either. Her mechanical hand is therefore an embodiment of her inhumanity (ie. her “dollness” or “weapon-ness”). Like her, it is cold, mechanical, insensitive, without life or agency. After all, up until now, all she’s been doing is killing on command, without the ability to think for herself, experience her own pain, or sympathize with her victims’ pain.

When the screen shows that Hodgins is indeed correct, that Violet is literally on fire (frame 1), that fire is depicted with restraint. Flames engulfs Violet’s body, but those flames are from a streetlamp enclosed in glass. It is controlled and distant. This encapsulates Violet’s current state; she is literally on fire, but that fire is so compartmentalized and suppressed, and she is so far removed from her own experience, that she is incapable of feeling it.

In frame 2, we are viewing Violet in a flashback, from Hodgin’s point of view. Although we’re offered a close up shot of her bloodied hands, we see, about two cuts later, that Hodgin is actually observing Violet from afar (frame 2.5). This distance demonstrates that he cannot bring himself to reach out to her, something that Hodgin confesses he feels guilty about literally 5 seconds later. They were, at that point in time, and perhaps even now, unable to connect.

In frames 3 and 4, Hodgin is speaking again. We get this super far shot of Violet’s body. The camera is straight on, objective, and unfeeling. This unsympathetic framing has two functions. First, it distances us from Violet. Our inability to see the details on her face and her relatively neutral body language gives us, the audience, no real way inidication her thoughts. Second, it distances Violet from herself. As someone who experiences dissociative symptoms from PTSD, this is a very poignant way of framing what it feels like to be removed from your own experience. Hodgin’s line, “You’ll understand what I’m saying one day. And, for the first time, you’ll notice all your burn scars,” further drives home the sense that Violet is completely estranged from herself. It almost feels like we are looking at her, from her own detached point of view.

We’re going to move on now, but we’ll get back to these frames later in the analysis, so hold onto them.

Throughout Violet’s journey, fire comes up again and again. Specifically, it shows up in moments of emotional intimacy, connection, and healing. Let’s see what I mean by this:

I have here a collection of moments that all occur at the same narrative point in their respective mini-stories: the moment where one character reaches out to another, sympathizes with them, and literally pulls them of their darkness. For example, frame 1 (episode 3) shows Violet bringing a letter from Luculia to her brother. It expresses Luculia’s gratitude and love for him, and ultimately mends their relationship. In frame 2 (episode 4), Violet and Iris share a moment of emotional intimacy and connection, which is the beginning of Iris’ story’s resolution. In frame 3 (episode 9), Violet’s suicidal despondency is interrupted by the mailman, bringing her a heartwarming letter from all her friends. In frame 4 (episode 11), Violet comforts a dying solder by a fireplace.

It’s not that other modes of lighting do not exist – modern looking lamps show up repeatedly in the show. Even Iris’ rural family has them, so I can reasonably assume that, no, the above moments do not all coincidentally use lamps because that’s all there is in this universe; the usage of fire during moments of catharsis is deliberate, and establishes that fire can also bring hope, kindness, and love.

Now that we’ve explored the dual nature of fire as both destructive/constructive, painful/cathartic, let’s go onto the thesis of my essay. Why do I say that being on fire is to be human? Let’s go back to the scene where Hodgin tells Violet she’s on fire (episode 1, on the left), and compare it to the scene where Violet finally realizes that Hodgin was right and that she is on fire (episode 7, on the right):

In these sequences, there is a notable shift in framing and perspective. In frame 1b, we finally get to see Violet’s blood-stained hands from her point of view, as opposed to from Hodgin’s point of view in 1a. Violet becomes aware of her past as an actual agent choosing to kill, shown through the first-person point of view. Similarly, the medium, straight on shot of Violet looking down at her hands (frame 2a) is replaced with an intimate first-person, close-up view (frame 2b). In shots 3a and 3b, the difference in framing is most pronounced. In 3a, we get this straight on, long shot. In frame 3b, the camera’s detachment is replaced by a claustrophobic closeness. While this framing does an excellent job at conveying the panicked feeling of “everything crashing down all at once”, it also demonstrates Violet’s new-found awareness of herself. While before, the camera was used to alienate, now it is used to create a sense of painful awareness and intimacy.

These series of shots are the first in the entire show, I believe, of Violet's body from her own point of view. Their co-incidence with her awakening self-awareness characterizes the state of “being in one’s body” as a precondition to self-connection, or more specifically, to Violet’s understanding of herself as neither a weapon nor a doll, but as a human. Correspondingly, this pivotal moment serves as a catalyst for her subsequent emotional development. From this episode on towards the finale, we’re launched into a heart wrenching sequence of events: Violet’s desperate grieving for Gilbert’s apparent death, her attempted suicide driven by newfound grief, and most importantly, Violet receiving her first written letter, an act that is strongly representative of genuine human connection. Following these events, Violet’s emotional connection to both herself and others only continues to grow; during her two final jobs of the story, she breaks down crying in response to the suffering of her clients, demonstrating a level of compassion—if not empathy—that she seems to have never been able to tap into before.

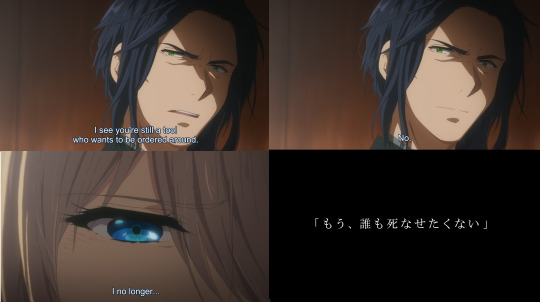

At the same time, Violet acquires a new sense of agency, making plot-driving decisions that no longer require other characters’ validations. Most poignantly, in episode 12, she chooses to stay on the train to fight Merkulov, explicitly going against Dietfried’s order for her to leave. Her reason?

She doesn’t want anyone to die anymore.

And it’s this moment, for me, that consolidated her as a character with true agency. Up until now, all her major decisions have been framed in relation to Gilbert: she killed in the war because Gilbert ordered her to, and she became an Auto Memories Doll because she wanted to understand Gilbert’s enigmatic “I love you”. Now, however, her motivation is purely her own—she fights, simply because she doesn’t want anyone else to die. It’s a line implies an intimate knowledge of loss. It’s a sentiment motivated by compassion. It’s a raw and extraordinarily human thing to say.

When Violet embarks on her journey to decipher Gilbert’s love, she is devoid of many traits we consider inherent and possibly even unique to being human—suffering, compassion, altruism, love, agency, and the interplay between them. As an Auto Memories Doll, she learns to live, experiencing all these emotions she had never had the luxury to experience before, and we quickly realize that she cannot know what love is without simultaneously wrestling with her trauma. She learns that yes, sometimes the fire destroys and sometimes it burns, but sometimes it thaws too, and you cannot have one without the other. You cannot choose what the fire does to you; you cannot choose what you want to feel. Thus, to be on fire is to know the anguish of its destruction, but it is also, and more importantly, to know the catharsis of human connection, to be the warm flame that pulls someone else out of the dark, to be pulled out of the dark yourself. To be on fire is to be human.

#violet evergarden#violet evergarden analysis#anime analysis#anime#anime essay#anime meta#violet evergarden meta#analysis#w.writing#w.analysis

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

so... i finally saw Midsommar

Those who recall how much I did NOT enjoy Hereditary (even though I wanted to, I swear!) will be gratified / vindicated / indifferent to learn that I enjoyed Midsommar much, MUCH more, and like it better and better the more I digest it. Folk horror in general is much more up my alley in terms of themes and tropes and tone, I suppose, and I love / sympathize with / want to communally wail in empathy with Dani a lot. I’ve seen a lot of talk about the intense emotional catharsis of her character arc and how it is arguably a freeing, liberating experience for her and yet simultaneously subsumes her into the very cultish, very boundary-erasing community of Hårga, a community in which individual lives and experiences are very much secondary to the community as a whole. And I find all of that fascinating. But one thing I haven’t really seen touched on is how this same sort of loss of identity is expressed through the particular way this film handles not death itself — we don’t even see half the deaths — but the remains of the dead.

Something I think about a lot when it comes to horror in general is the idea of the human body as meat: not the flesh of a person but the meat of an animal, which is, after all, what we all are, and what we will all become, in the end. And many of us don’t like to think about that! We don’t like to think about dying, and we don’t like to think about what will happen to our bodies after we die, and we don’t like to think of ourselves as meat because meat is fallible, meat is ephemeral, meat is food — something that will inevitably be devoured and digested and broken down. Many (though not all) of us have tried to forestall this process, of course... Speaking particularly from my own modern Western/American perspective (a cultural perspective similar to what the outsiders in Midsommar bring with them to Hårga), we commonly treat our cadavers with cosmetics and preservatives to prolong the illusion of life; we handle our loved one’s remains (however they are disposed of) with reverence and respect, we fear and avoid corpses in general, and we regard mistreating a corpse as an insult and an act of violence irrespective of the corpse’s actual sentience or ability to feel pain. Even if we believe that the soul persists in some afterlife and/or that the body is but a shell, our actions tend to reflect a strongly held feeling that human remains are still, in some way, people rather than just objects.

And where Midsommar derives much of its horror, I think, is from its very stark denial of that mind-set. Not every horror film really engages with this idea of bodies as meat, in my opinion, not even the ones with corpses strewn over every frame... I’m struggling to articulate my point here and didn’t really mean to go on like this in the first place, but I think one doesn’t necessarily engage with this concept simply by reducing a character to blood and guts. In fact, I think the relative lack of blood in Midsommar contributes to this theme by virtue of not visually obscuring what happens to the characters’ flesh, particularly when it comes to the many lingering close-ups on the sacrifices of the attestupa. The presentation of their ruined faces is starkly clear, unartificial, unadorned, and unsentimental. The face, the part of the human body most associated with identity and personhood, reduced to a very clearly visible tangle of meat and bone. Other faces are flayed and passed around as masks; other bodies are used to feed the chickens, or buried in the garden in much the same way grain and meat were buried so that the May Queen could bless the crops and livestock. And in general, the way the camera presents these corpses to the audience is extremely... matter of fact. No jump scares, no spooky lighting or gushing blood. Just plain shots in plain daylight. Most of the time, the camera handles the corpses as casually and comfortably as the Hårga themselves do when they lug them about and prop them up as though there’s nothing disturbing about touching a bloated or mangled corpse. Why would there be? These are farm people, after all, accustomed to butchering livestock. The bodies they hoist from those wheelbarrows are just more meat.

And if that seems to fly in the fact of the fact that these corpses are part of a very holy ritual — and therefore would surely be imbued with a certain holiness themselves — I would argue that the Hårga regard those corpses as no more holy than the slab of livestock meat they buried with the grain. (And no less holy, either.) I would argue that their ancestral tree is far more holy and more of a person to them than the actual bodies that are burned to be scattered upon it. I would argue that the erasure of individual identity and the transformation of Human Person into Organic Object is, in fact, essential in a society and a ritual centered around ideas of growth and rebirth and harvest and being intimately connected to each other and to nature and regarding death, very unflinchingly, as the natural conclusion of one cycle and the beginning of another. Before the elders jump from the precipice, they are honored, they are regarded as individuals, they are loved. Before the volunteers are consumed by the fire, we see them embrace the members of their community in farewell. The people of Hårga truly care for each other, I really believe, and do not take lightly the sacrifice of their lives. They simply are not very sentimental about their flesh.

So the horror of this film, then — or part of the horror, at least — comes from this disconnect between Hårga’s very blase and matter-of-fact view of bodies as organic objects that grow, breed, reproduce, age, die, and then become food for other things (be they trees or chickens or flames), versus the outsiders’ view of bodies as intrinsic extensions of personhood (and thus horrific to violate or disrespect or kill). The audience (or at least most people I know) tend to be aligned with the outsiders’ perspective on this. The camera tends to be aligned with Hårga’s. And Dani, who starts out haunted by the corpse of her sister and all the grief and horror it represents, ultimately becomes complicit in the making of corpses via becoming something of a metaphorical corpse herself: her old life destroyed, her new life just on the cusp of beginning, her sense of self having been chewed up and devoured and digested into something new.

#local blogger has never been succinct in her life#anyway i think about this concept All The Time#and the various ways it's expressed in the horror genre & the grotesque genre & irl & etc etc etc#and how it underpins so much of what ppl tend to find frightening or uncomfortable or uncanny... good stuff good stuff#midsommar#my meta#op

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

God, We're All Tired: Female Conflict in Killing Eve's Season One Finale

So I'm sure 1x08 has been analysed to death, but seeing as we're winding up to the end of Killing Eve's second season (sad face), I thought I'd jump in with a completely unsolicited reflection on the ultimate culmination of Villanelle and Eve's mutual obsession and pursuit.

I'll kick off by saying that from the start, we knew this moment would be interesting, for a whole slew of reasons:

Firstly, from the get-go, we were shown that Killing Eve was here to subvert and reconstruct; it's deeply oriented within its genre, but it's irreverent, and even what I would describe as a reclamation of spy-fi. Specifically, it's a female-led narrative taking ownership of a set of texts and tropes that have consistently objectified and excluded women by turns. From its inception, the psychological thriller genre has delighted in a) withholding women's agency, and killing/torturing/assaulting them, both to shock viewers and to lend pathos to the motivations of male characters, and b) revelling in their "expiration" from sexual desirability, and casting the "ailing crone" as the villain orchestrating events. Killing Eve has absolutely no interest in ever reducing its women to their component parts. There are no pedestals, and there are no pitchforks. As a show, it hits all the golden points of suspense television, and completely reimagines the rest; it's a masterpiece balacing act of keeping the classic cat-and-mouse recogniseable, while allowing Eve and Villanelle to each be both the predator and the prey.

Secondly, our two protagonists are women. Highly unusual and exceptional women -- that's inarguable -- but nevertheless, they've been socialised in particular ways. What's so fascinating here is that both have been injected with a comfort in and enjoyment of theatrical violence that's usually reserved for male villains. However, even at their most ruthless, there's an innate intimacy to both of them -- unlike, say, for example, the Joker, Villanelle's flamboyance and love affair with destruction never manifest as mass-killings or the eradication of infrastructure (like blowing up a hospital). Villanelle exacts each murder with the creativity of the truly engaged and passionate, but it's always personal and unique, usually one-on-one. She doesn't have a vendetta against the world, either; she finds beauty in it -- in ice-cream and movies and nice architecture or fun clothes. Similarly, Eve is enthralled by Villanelle's flair for the deadly and the dramatic, but it's not born out of a spite for humanity, but a sense of artistry and a consuming need for some adrenaline in her otherwise numb and mundane life. These complexities muddle their emotions and motivations, and make it difficult for even the most television-literate to semi-accurately predict their storylines.

Thirdly, Eve and Villanelle are never positioned as diametrically opposed. This in itself is not exactly out of the left field -- a lot of media with a dark focal point or mature subjects introduce heroes and villains who share key traits (e.g. Sherlock and Irene, in CBS's Elementary), or even comparable goals (e.g. Black Panther's Killmonger and Nadia both want to open Wakanda's borders). In most cases, though, the antagonist will represent some kind of seduction to the 'other side', that the protagonist inevitably resists the allure of (e.g. Andy realising Miranda isn't who she wants to grow up to be -- successful but alienated -- and goes back to her excuse of a boyfriend in TDWP). But while Eve and Villanelle are very much established as one another's temptations, we also see that they'll grant the other access to a part of the world that is, for now, barred from them: Villanelle and Eve will stop each other from being bored. They "resist the allure" not because they fear moral wrongdoing, but because they cling to their respective images of themselves -- Eve, as someone "nice and normal", who happens to have a grey area for a hobby, and Villanelle, as someone independent, in control, with no lines she wouldn't cross.

Way back in the pilot, we're shown that they don't actually WANT to destroy each other. Villanelle is too interesting to Eve, Eve is too attractive to Villanelle. Yes, they pose a significant threat to their respective lifestyles, but as we've had proven, they're becoming willing to risk that if it means gaining something more. They don't reflect a sinister alternative timeline of "look what you could've been" (which is inherently hero-centric, and Killing Eve pays as much attention to Villanelle as Eve), they offer each other a "look what you could still be", that is at once dark and hopeful -- something that they've really elaborated on in this second season.

But 1x08, even though it is very much the symbolic collision that is the centrepiece of all chase stories, is not their first meeting. Villanelle goes to Eve's house in the (iconic) 1x05. So why not save that for the finale? Why not build and build and have that tension released right at the end? Because, crucially, 1x05 generated more tension. The show's writing is so substantial that it doesn't worry about losing its audience after the moment they've been waiting for happens. It's one of the reasons you could have the entire plot of Killing Eve spoiled, and then still enjoy every episode when you watch it yourself: it's the How that we love as much as the What. Killing Eve takes the time and space to revel in its style, characters, and setting -- but that's another essay.

In 1x05, their meeting is high-octane, and crucially, it's brief. We get a snapshot of how their infatuation and fixation translates into chemistry. And they both become real to one another. Eve's last reservations begin to fade as she realises that she can survive an encounter with Villanelle, and her sense of self -- most importantly, the subconscious idea that she's somehow special -- is vindicated (Eve's slight narcissism, and how the show makes it compelling and intoxicating, is yet another thing I could go on about). For Villanelle, Eve is allowed to be more than just great hair and a worthy threat. She's someone challenging and entertaining. What's so incredible about that first meeting is that it's proof that this dynamic isn't running on mystery and fumes. It's sustainable. They continue to appeal to one another once they're in the same room together. They appeal even more. Their sexual tension skyrockets, and the whole dance becomes extremely personal. They can't write one another off as playthings, although they largely continue to attempt that, at least for a short while.

With this in mind, let's move on to that finale. Not only is Eve trashing Villanelle's apartment hilarious, and a perfect articulation of the humour/danger cantilever that makes Killing Eve awesome, but it provides a critical catharsis for the audience before the actual confrontation. By this point, the price for Eve's obsession is starting to rack up -- her job is circling the drain, Niko's dodging her calls, her self-image is blurring. Eve has a whole lot of feelings, but she's allowed to express them on her own, symbolically taking them out on Villanelle by ruining her things, which become a vehicle for venting her frustrations without actually affecting their relationship.

When Villanelle does arrive, Eve's ready. This scene would've worked if it was some sexy wall-leaning, banter, and Eve surprise-stabbing Villanelle in the middle of a conversation. I think that's probably how a lot of screenwriters today would've done it, scrawling it off by rote and relying on Villaneve's chemistry and Comer and Oh's excellent acting to nail the bit. Instead, we get this civil conversation, and then they lie down together, first relaxing, and then gravitating towards one another. I don't believe that Eve knew until the millisecond she decided to do it that she would actually try and stab Villanelle.

I actually gave this mini-essay a title, and it's "female conflict". That's because I think that this entire sequence wouldn't have happened in a show created by men, or featuring male characters. In violent shows, we get violent conflict. Killing Eve is unquestionably a violent show, but it's distinct from its contemporaries in that the characters aren't there to prop up the violence; the violence is there to reveal and develop the characters.

But after a whole season of elaborate murder and tyre-squealing pursuit, we get this stillness. Yet, it doesn't feel for even a beat like bathos. It's absolutely a climax, and it's both suspenseful and arresting. It really illustrates that the show is about fascination: they're hungry to know everything, like Eve says. There's no performative combat. We can't guess what's going to happen because neither can they. Their obsession isn't a "this town ain’t big enough for the both of us" situation. It's a "this town is only the both of us". Their worlds are reduced to each other and they don't want to squander it with fighting, because fundamentally, Eve and Villanelle are so much more similar than they are different.

Again, I say this is so fitting for female characters because they see this co-existence as an option. It's so simple, but the idea of your protagonist and antagonist sighing, "Fuck, can't we just have a lie down after all this?" and making it satisfying is incredibly radical. Because it's so personal, and intimate, and human. At every interval, the writing asks, What would we actually do at this moment? Not, What precedent has popular culture set for this moment? Too often, I think we give characters responses that we've seen before in texts, because we watched/read it, accepted it, and just filed it into our own work, knowing it's what the audience expects. But this scene with Eve and Villanelle is so heart-wrenchingly in-character. It's two people charging at each other full speed, not to hit each other but to be close to one another. And like so many other tiny beats over the course of the season, Killing Eve luxuriates in this proximity.

We get to breathe. It's gentle. It's a gentle pause between two people who could utterly eradicate one another, but choose not to. It's ladden as well with such a specific but familiar kind of exhaustion, and it's an act of defiance, too. Killing Eve rejects the hegemonic (and predominantly masculine) cultural assertion that conflict (or even sometimes, in the less typical texts, debate and negotiation) is the way to resolve difference, and indeed, that difference must be resolved. That one must overpower the other. That your enemy is an alien and cannot be connected with, related to.

The fact is, a lot of even this first season isn't spent chasing, it's spent running. Eve and Villanelle take an interest in each other early on, and it quickly escalates from intellectual to sexual to emotional (insofar as either of them are capable of that). By 1x05, they've caught up to each other. The rest of the time, though, they're fleeing from how much they want each other, how alike they might be. And in Villanelle's Paris apartment, they concede: I love you more than I hate you. I need you more than I should.

And it's with that concession that we as an audience can experience their relaxation, too. It's what we've -- consciously or not -- been waiting for. That acknowledgement.

But Margot, you say, you've been talking about how this isn't about violence -- have your forgotten that Eve STABS Villanelle, literally three seconds after this?

I have not, The Only Follower Who Read This Far. So why engineer all this, and then have Eve knife Villanelle straight in the gut?

Because even though they have this liminal second together, their story isn't resolved. Killing Eve goes absolutely wild with power dynamics, and I could discuss that for hours, too -- Eve is older, but Villanelle is more experienced; Eve is more stable, but Villanelle is more adaptable, etc. But generally speaking -- partially because Eve is, at the beginning, something of an audience surrogate -- the scales are in Villanelle's favour. She's dangerous, clever, has no fear of legal consequences, and has more freedom and greater resources.

Killing Eve is allergic to any pedestrian predictability, so it shakes up this arrangement. In stabbing Villanelle, Eve proves to both of them what she's capable of. Prior to this, they had an impression of their similarities, but this throws into sharp relief exactly how deep those run. Eve immediately regrets the stabbing, because it wasn't about getting rid of Villanelle. She doesn't want to hurt her so much as show her that Eve has power too, has recklessness too, can keep up.

This interaction isn't the product of an inability to relate, but a desperation to connect. This joins them together, affirms their relationship. Eve isn't trying to dominate her, to win, not really. She's telling Villanelle what she's capable of, and equating them. We get this confirmed in how Villanelle perceives in the stab wound as a symbol of affection (2x02, 2x05), and how Eve says she continues to think about it constantly (2x05).

I believe that while Villanelle always respected Eve, if Eve hadn't stabbed her, Villanelle would've remained confident that she, quietly, had the upper hand. That if ever need be, she could be more cunning and cruel and decisive than Eve. But Eve's put them in the same ring, and also removed one major wall between them -- Villanelle's murderous side is a key part of her character, and after this, she knows that Eve isn't intruiged by her despite this, but because of it, and because it’s at least partially common ground. Eve isn't Anna (another comparison I could go off on a tangent about, but I'll spare you).

In sum, I think that the season one finale was beautifully rendered, and reflected Killing Eve's appreciation of itself. It let the characters interact genuinely, it refreshed their dynamic, and allowed them development separately (Eve's new understanding of her own capacity for harm; Villanelle's new experience with vulnerability, and not being able to predict others) and together (intertwining them irrevocably, further aligning them). It's one of those rare scenes where it's completely surprising at the time of viewing, but in hindsight, seems inevitable, and you can't imagine it any different.

I can't make any predictions for the season two final episode other than I expect something equally unexpected, something just as loyal to the characters and their relationship, and their capacity to embrace and antagonise each other.

This essay is probably borderline incoherent. It really got away from me. I set a timer for half an hour and told myself that whatever I got written in that time, I'd post. Thanks so much for your kind comments on my rant yesterday, and I hope this is at least vaguely what you were looking for, @ the people who said they'd read another. You're my favs.

If you've got something else Killing Eve-related you'd like me to yell about, let me know! Or if you want to come chat, I promise I'm friendly! I’m using the tag “#villainever writes” for this rambly stuff atm, so if I ever write another of these I’ll have a digital drawer to put it in hahah

#villainever writes#villaneve#killing eve#killing eve essay#ke analysis#killing eve analysis#villanelle#eve polastri#eve x villanelle#eve x oksana#villanelle x eve#villainever#villanevest writes

132 notes

·

View notes

Text

How some stoners named “Harold & Kumar” made Asian Americans proud

Being Asian American can make you feel invisible at times or worst, the butt of every bad joke.

Sure, lots of Americans love Asian things like sushi, kung fu, anime, and tacky calligraphy tattoos that don’t mean what they say they mean but they don’t particularly care about having the people themselves present or even represented.

And typically when we are represented it tends to look like this.

Or this.

Or this.

(I said what I SAID!)

Now Asian Americans are not by any stretch the most marginalized or even the least represented people in the larger American cultural diaspora, but they’re fairly consistently forgotten or grossly stereotyped in our media regardless and this has larger consequences. Representation is important because it makes a people’s presence known to the larger majority.

Our pop culture has unfortunately played a role in erasing, appropriating, and misrepresenting Asian folk. An action movie may feature a white actor with extreme martial arts skills fighting in Hong Kong but might not have a single prominent Asian voice throughout the plot and those that do are typically gross caricatures. The Cyberpunk genre loves Asian aesthetics from its Tokyo inspired neon lighting, futurist cityscape, and ramen carts abound but boy, is the populace typically dominantly white.

(I love this movie but considering how many Asian things and aesthetic choices there are in it would it have killed Denis Villeneuve to have at least ONE background Asian person??)

It’s not shocking then that 2004’s stoner comedy classic “Harold & Kumar” starts with a pair of white dudes beginning their own adventure by leaving one of the titular heroes in the dust to do their dirty work because “Asians love math” or something. Despite not being a stoner, at the time at least, I related hard to this movie and its characters as the film touched on a number of triggers I had growing up.

2004 was a formative year for me as an Asian American. For the first time ever, my history classes were touching on Asian culture with discussions on Japanese feudalism which awakened a deep sense of pride I didn’t know I had at the time. I was watching NHK samurai dramas about Miyamoto Musashi and later the Shinsengumi which led to me begin training in kendo. Anime had suddenly become more mainstream with the premiere of Shonen Jump and pirated subtitled anime littering all of YouTube. But more importantly, and distressingly, I became more aware of my identity because it was increasingly getting called out as I was getting older.

I’ve been labeled a number of different pejoratives growing up through my teens.

“Nerd.”

“Weirdo.”

“Loser”

But none cut deeper than “Chinese boy.”

I’m not Chinese, of course, in fact I’m half white and half Japanese but try telling the various ignorant lunkheads I knew growing up to respect and differentiate between them all. Hell, better yet tell them I’m just as American as they are too.

Being labeled “Chinese” hit a very personal chord with me. To lots of Americans, unfortunately, we’re all “Chinese” and the various qualities that make each of our cultures unique are inconsequential to them. We AAPI’s all individually take a measure of pride in those unique qualities and to have it all sequestered under a blanket “Chinese” label was beyond insulting.

(And I don’t care what you tell me or how much you hate China’s government, this is a THOUSAND percent a dog whistle.)

For Asian Americans, there have been various ways one reacts to these insults. Some of course, who learned confidence at a younger age, would shrug it off or ignore it, some would outright resent it but for me at least it only made me dig my heels in deeper. Yeah, I’m Asian, so fuck you!

That energy is deep “Harold & Kumar Go To White Castle” as these two Asian American characters not only navigate a crazy night of searching for an open White Castle to satisfy their stoner cravings but also confront various microaggressions from outside and within the Asian community.

Harold, of course, struggles with his confidence. He can’t stand up for himself when the aforementioned two white bros from the start of the film saddle him with extra work. He laments doing the typical Asian thing of being too passive when confronted by authority. He can’t find the will to ask the girl next door out because again he sees himself as an impotent Asian guy unwilling to make the first move. The whole movie he struggles with his inner feelings because he’s been taught and programmed to a certain extent to be timid because that’s the Asian identity.

Meanwhile, Kumar’s character is about resisting conformity to those same stereotypes but in the worst ways. He co-opts black and hip-hop culture as seen in his messy apartment room. He fights his dad who is forcing him to take his doctor's exam, something he doesn’t want. Generational pressure is common in all cultures but it’s an entirely different animal when it comes to the Asian upbringing. Kumar embodies this resist from beginning to the end of the film and though he does decide to take the test, it’s important that he chooses to do it, not his dad, and certainly not because he’s Indian. He decides that choosing to be a great doctor doesn’t mean he is becoming a stereotype because his identity is not just about being Asian.

(Every Asian kid has heard their parent make an unintentional innuendo.)

Harold and Kumar’s differing approaches create a charming pair for the film to bounce off as Kumar’s brashness often lands them in trouble and Harold’s timid demure keeps them down in its own way and the two finally come together when Kumar learns to understand the difference between conformity and choice and Harold learns conformity doesn’t define him.

Both characters confront all kinds of microaggressions against their identity throughout the film. Cops making fun of their names. The extreme sports bros making every racist joke every Asian kid has every heard growing up at them. All Asian Americans have grown up wanting to deliver the perfect comeback or “fuck you” moment against these types of people and when our heroes triumph and put them all in their place there is undeniable catharsis as it happens for everyone who has seen this movie.

youtube

(Seriously, there isn’t a more satisfying good triumphing over evil moment in film for me than the conclusion of this particular plot.)

The movie confronts stereotypes in more ways than one though. Throughout the movie Harold and Kumar are confronted by a situation that makes them think it’ll go one direction but ends up (usually comedically) the opposite. Harold and Kumar try to hook up with two beautiful transfer students who turn out to have horrible bowel issues. Harold is reluctant to go to the Asian American club party because even he believes in his own ethnic stereotypes of them but it turns out it’s a banger of a party with plenty of weed to boot. Harold and Kumar are picked up by a lonesome, disfigured tow truck driver and are shocked to find he’s married to a beautiful woman. And the aforementioned extreme sports bros turn out to love cheesy pop music and romantic songs.

Basically, the whole movie is about giving a big middle finger to all our preconceived notions we have about identity and it's brilliant.

(Nothing wrong with cheesy pop music, of course.)

“Harold & Kumar” is great for other reasons too. John Cho and Kal Penn still play greatly off each other. There’s plenty of great one-liners sprinkled between each scene. The entire journey to find White Castle burgers in the middle of the night is a fairly genius premise for a stoner comedy still. And Neil Patrick Harris playing “himself” is still iconic.

Parts of the movie haven’t aged, well of course. There’s some bad gross-out humor, some lazy gay panic jokes and not to mention some sexist quips that don’t land well in 2020. Also, let’s just not talk about the sequels.

youtube

(I still find this scene amusing though.)

That said, “Harold & Kumar’s” first film in this munchie saga is not only a grade-A stoner flick but simply one of the best films ever when it comes to bringing that much needed representation of the time to Asian Americans. Watching Harold & Kumar stick it to their annoying white antagonists while delivering a “fuck you” to every racist joke I ever heard growing up is still cathartic as hell and made me feel proud to be Asian American during a turbulent time for myself growing up.

Though it’s not Masterpiece Theater by any stretch, Harold & Kumar will always hold a special place in my heart and remains forever “high” on my list of favorite movies of all-time.

Happy 4/20, y’all!

#harold and kumar#Harold and Kumar Go To White Castle#John Cho#Kal Penn#Asian American creative voices#asian american#aapi#Pacific Islander#4/20#420#weed#marijuana#getting high#movie#films#stoner#stoner films#big lebowski#Indian american#Japan#Korean American#Chinese#China#Asia#munchies#White Castle#Burgers#cheeseburgers#cyberpunk#Ghost in the Shell

1 note

·

View note

Note

u should answer the questions for the letters: c r i s p y. no real reason for those letters, in that order. obviously

henlo friend and thank you!!! I had a lot of fun with these and also did not shut up.

C: What member do you identify with most?

Oh man. That’s actually really hard? Obviously I’ve done a fair bit of ego-involvement with the crispy boy (no really??) but overall in terms of personality I’d say I identify most with Maia, show!Jace, or Simon.

Maia has had a lot of shit happen but she’s incredible in how much she keeps working towards her dreams and supporting the people she cares about. As much as she knows and has learned to value and protect herself, she’s ferociously protective of her loved ones. She also has a fair bit of ambition, a strong sense of morality and justice, and feeling of responsibility--towards the pack, and for herself. I do see a bit of myself in her but more than anything I aspire to be more like her.

Show!Jace I relate to a lot mostly because I’ve projected on him so much (lol) but I really get a deep sense of struggling with himself and being closeted. He’s kind of depressed and sad and who can’t relate to that? But underlying all that he has a deep and almost desperate need for human connection and also he has daddy issues, so like, worm.

Simon is a giddy nerd who has a lot of weird shit happen to him and more than anything I think he’s just kind of...the everyman in terms of pop culture references etc. But he also has a heart of gold and loves like a golden retriever and who doesn’t want to be that?

To be honest I don’t really know why I latched onto Jonathan so much, other than the obvious daddy issues thing. Maybe it’s the frustrated sense of longing for belonging and connection, or the deep feeling of self-hatred or the profound desire to be better or different than he is. I think there are a lot of things Jonathan’s demon blood could represent that are a lot less esoteric or boring than “pure evil.” Also I just love tragic, powerful dumb bitches so yknow.

R: Are there any writers (fanfic or otherwise) you consider an influence?

Man I was literally JUST thinking about how much I’ve taken from JKR as a writer, not even on purpose but just in...she was the first writer whose work I truly soaked in daily for years and years, it’s not surprising I see her voice or her humor or her narrative/structural quirks coming out in my own writing.

I: Do you have a guilty pleasure in fic (reading or writing)?

Oh god, do I. I would say unhealthy power dynamics are both my catnip and kryptonite. I was actually just thinking about this too--I think the attraction for me is the catharsis of “controlled horror.” Abusive or coercive relationships in real life do literally terrify me, but I find them just short of fascinating in fiction. It’s like fiction allows me to experience and access and interact with that fear in controlled doses (like watching horror movies does for horror buffs), and that catharsis somehow translates as weirdly alluring.

S: Any fandom tropes you can’t resist?

I already answered this but I’d say the above paragraph expresses it better.

P: Are you what George R. R. Martin would call an “architect” or a “gardener”? (How much do you plan in advance, versus letting the story unfold as you go?)

I’m very much an obsessive planner, but weirdly neurotic about needing to be able to spin off whims or ideas as I go. I think having a sense of structure is essential, but allowing yourself the flexibility to look at the events you’ve planned or your ideas in new and creative ways is necessary to have anything new or spontaneous.

The backbone of the idea or plot usually comes to me as a whole, but I believe very strongly you need to allow yourself to innovate and spin off those ideas as the organic connections made as you write grow and mutuate the structure.

so like, both. also fuck grrm

Y: A character you want to protect.

Maia Roberts, Izzy Lightwood, Clary Fray, Luke Garroway, Aline Penhallow, Sebastian Verlac and Victor Aldertree.

Unprotect JCM at all costs. (but also protect him)

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

Eric here. Today, I’m posting a fair chunk of the current Conviction and Loyalty section of Deviant. If conspiracies drive the actions of the entire cohort, Conviction and Loyalty Touchstones provide specific motivation to each individual Remade. Ready? Here we go:

Divergence damages the part of the Remade’s soul that once guided her senses of self and identity, replacing Virtue and Vice with the twin Anchors of Loyalty and Conviction. She defines herself by her interactions with others — specifically those actions driven by love and hate and directed toward a specific person, group, cause, or location.

A Remade’s Conviction can run white hot or blisteringly cold. It compels the transformed to do what needs to be done, often forcing her to make hard choices in the pursuit of her designated enemies. It dictates her need to confront anyone who would keep her from pursuing her goals. Conviction is the churning, seething anger that always lurks at the edges of her emotions. It is what makes a Renegade fight, what gives her the courage to escape, and what pushes her to determine her own fate. Conviction serves as a source of Willpower based on her actions.

Where anger and hate guide Conviction, Loyalty represents the Remade’s ties to those she cares about deeply and strives to protect — both from herself and from the sinister forces she tangles with. These are those few people who have stood by her since her Divergence, who accepted her how she was before and how she is now. They’re the friends and family who refuse to be scared off even when she insists they ought to run, that it’s for their own good. They’re also the new friends she’s made since everything changed. It’s hard for a Deviant to maintain relationships, but these ones approach the sacred for her. She’ll do anything it takes to protect the people who have earned her trust to this degree. Loyalty restores the Broken’s Willpower when she acts to uphold it.

Touchstones

Touchstones invoke strong feelings of hate or love in the Remade, anchoring her to her remaining humanity. Acting for or against a Touchstone helps the Deviant keep her Instabilities from growing worse, while falling short of these obligations shakes her confidence and can trigger disastrous complications.

Whether Conviction or Loyalty, most Touchstones are individual people. Some Broken forge ties with an object, place, or organization, but these are always concrete and localized – something that can be threatened or destroyed by a single actor in a single time and place, whether with a gun or an explosive.

A Deviant hates her Conviction Touchstones with a limitless rage. She recalls them with a passion so deep it always seethes just beneath the surface, ready to boil over. Most are members of the conspiracy that stalks her or created her: her Progenitor, the school administrator who nominated her for the experimental program, the lab tech who injected her with the serum, or the old roommate who invited her along to participate in an obscure ritual. She might even wish to see the lab where she was experimented on destroyed, or the ritual altar smashed Others have earned her enmity in other ways, such as by threatening a Loyalty Touchstone, standing in the way of the Remade’s revenge, or inconveniencing her in other ways: the police officer who keeps hauling her in for questioning, or the neighborhood gang that’s always making trouble for the cohort and their allies.

If causing a Conviction Touchstone to suffer is satisfying, killing one outright offers a moment of catharsis. However, resolving a Conviction Touchstone by destroying it does not extinguish the yawning chasm of the Deviant’s need to protect or exact vengeance. The Remade who destroys one Conviction Touchstone almost always replaces it with another as soon as possible – or with a Loyalty Touchstone.

The focus of a Loyalty Touchstone is often someone the Deviant knew before her Divergence. This may be an old friend or lover, a partner in crime, or even a former enemy whose past sins now pale in comparison to what her Progenitor did to her. Some Touchstones form after the Renegade goes through her ordeal: the lab assistant who helped her escape, or the member of her cohort who bears an uncanny resemblance to her little sister. They are people who remind her that even though being Remade took away a piece of her humanity, it didn’t take all of it. They show the transformed kindness even when — especially when — she’s incapable of showing it to herself, and they have her back even if they don’t always agree with her choices.

Loyalty Touchstones are the source of both comfort and concern for the Deviant. The Touchstone is the person he goes to when he’s troubled, but that means if his enemies are watching, and he’s not careful enough, he’s putting his friend in the conspiracy’s crosshairs. Ruthless conspirators often threaten to harm the Touchstone, following her to work, watching her children on the playground. They make her life difficult, sometimes using bureaucratic frustrations to mask their involvement. Police show up on her doorstep, following up on a tip that she’s harboring the fugitive Renegade. Child services pays a visit based on an anonymous call from a concerned party. Some conspirators contact the Touchstone directly, attempting to turn her against the Remade or suggesting they can protect her from him if he grows violent. They try their best to sow seeds of doubt between them.

Upsetting the Broken’s loved ones is a combination of a taunt and a threat. The conspiracy wants the Renegade to know they’re watching, to know they’re keeping tabs on where he goes and who he values. Anything they can do to throw their target off-balance is just fine by the conspiracy. In extreme cases, the Deviant’s enemies kidnap his Touchstones or put them in physical danger. While this can draw the Remade out of hiding or make him come to the table and negotiate, it also serves to fuel his hate and determination against the conspirators involved. Overtly threatening a Touchstone can backfire — a Touchstone is much less likely to be off the grid, and therefore will be missed by other people in her life if she suddenly stops showing up for work or her children don’t come to school. Conspirators usually deploy these extreme tactics sparingly, and only when they’re certain they can minimize the fallout.

Systems

Starting Renegade characters begin with at least three dots in Conviction and one in Loyalty, which Origin then modifies (see Chapter One). The sum of Loyalty and Conviction is never more than five. Each dot has one associated Touchstone, a character toward whom the Renegade feels a particularly strong hatred or protectiveness.

After a scene in which the Renegade makes progress toward one of her Conviction Touchstones, she gains one Willpower and takes a Beat. Once per session, when she risks danger or suffers for her Loyalty Touchstone, she regains all Willpower.

If a Touchstone is destroyed or killed, or when a Touchstone falls to Wavering, the Broken’s Loyalty or Conviction falls by one (depending on which Trait the Touchstone was attached to). If both Loyalty and Conviction reach 0, the Deviant goes Feral (p. XX).

Once per chapter, the Remade may declare a new Touchstone to fill an open Touchstone slot. This Touchstone begins at Wavering, and therefore doesn’t increase the character’s Loyalty or Conviction, unless it is successfully affirmed (p. XX).

A Touchstone may switch from Loyalty to Conviction (or vice versa) without Wavering first, as long as the Touchstone itself remains the same. When the Broken’s best friend betrays her, for example, her rage is so instantaneous she doesn’t pause to consider why her friend might have done such a thing.

Abandoning an existing Touchstone and replacing it with a new one is a two-step process. First, the Remade must cut ties with the old Touchstone, therefore losing a point of Loyalty or Conviction. This counts the same as his declaring a new Touchstone action for the chapter. Once the next chapter begins, he may name his new Touchstone, which begins at Wavering.

Acting counter to his Touchstone — failing to pursue the subject of a Conviction Touchstone or abandoning a Loyalty Touchstone in a time of need — means the Renegade has Faltered. The player rolls his current trait rating as a dice pool to determine the severity of the damage to the relationship:

Roll Results

Success: The character believes he made the right choice. Both trait and Touchstone remain in place.

Exceptional Success: The character heals a minor Instability.

Failure: Remove a dot of the trait. The Touchstone remains in place but becomes Wavering.

Dramatic Failure: The character loses both a dot in the trait and the Touchstone and suffers a medium Instability.

When a character acts against a Wavering Touchstone, he rolls his current trait as above, but on a failed roll, the Touchstone is lost, in addition to the dot.

The Renegade can also attempt to affirm a Wavering Touchstone, strengthening his friendship or rekindling his hatred for a conspirator. When he acts in support of a Wavering Touchstone, he rolls the trait (Conviction or Loyalty) as a dice pool.

Roll Results

Success: The character has gone above and beyond for his friend, or done a job that reminded him just how deeply his hatred toward his enemy burns. The Touchstone is no longer Wavering, and the Renegade gains a dot in that trait.

Exceptional Success: In affirming his dedication to the Touchstone, the character discovers a new reservoir of rage or devotion within himself. The character successfully affirms the Touchstone as above. In addition, if the character has an open Touchstone slot, he may immediately assign a new Touchstone, even if he has already done so during the current chapter. This new Touchstone is initially Wavering, as normal.

Failure: Nothing changes. The character has done the bare minimum his friend expects a decent person to do, or has chased down a lead against his enemy without any tangible results. The character does not regain the dot in the trait, and the Touchstone remains Wavering.

Dramatic Failure: The character finds he cannot rekindle his love or hate of the Touchstone. The character loses the Wavering Touchstone.

Sometimes the Renegade is caught between pursuing a Conviction Touchstone and aiding a Loyalty one. He gains the benefits for the one he follows, and rolls Faltering for the one he failed.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dear Mr. Met:

The other day I was riding my bike and I blew right through a stop sign. Didn’t even slow down. Didn’t even see it. I blame the Mets, partly. I was listening to a Mets game on my phone and they were winning but the Orioles had the bases loaded in the eighth and I was getting nervous. It was only my second day as a dog walker, so the part of my brain that wasn’t worried about the Mets was worried that I’d left a dog outside or a door unlocked or maybe the owners thought my notes were weird and they didn’t want me walking their dog again. With my brain full of such thoughts and feelings, I blew right through the stop sign.

I don’t mean I saw the stop sign, slowed down, looked both ways, and rolled on through without coming to a full stop. I do that all the time. No, I’m talking about blowing right through it, not even knowing it was there.

I don’t normally listen to my phone when I’m out biking, running, or walking. I don’t like things in my ears, for one, and I genuinely like hearing the sounds of the city. I thought I might be okay listening to the game since I wasn’t wearing ear buds. I had the phone mounted on my handlebars, the volume turned all the way up. It worked right up until the bases were loaded and I got nervous and blew right through the stop sign.

A guy in a truck honked at me and called me an asshole. It could have been worse, he could have also been distracted, maybe also by the Mets. Who knows? It’s a big city in a big world. Maybe it was his second to last day on the job. Maybe it had been too many days since his last day on the job. Maybe his daughter was in the hospital. Maybe his daughter wasn’t talking to him. Maybe his daughter finally called him that morning after twenty-eight years. Maybe his boyfriend broke up with him. The multiplicity of possibilities boggles the mind.

The point is, the guy could have also been distracted and blown right through the stop sign and then I really would have been in a jackpot. I still didn’t like being called an asshole, though, so I hit my brakes and turned around.

Oh, he said, yeah?

Yeah, I said, and rode right back at him.

*

You know how there’s this idea that if we put energy out into the world our desires can manifest? I believe that to be true. I’m not sure exactly how it works, I just know it works because I’ve seen it work. Rather, I’ve seen the inverse work. The energy I put out disintegrates the objects of my desire, which Buddhists say is good, I think, but I don’t know. I find it to be frustrating more than anything.

It makes sense when you think about it. If there is a law of attraction, then there has to be a law of repulsion. No light without dark. No day without night. No hot without cold. No pleasure without pain. No sweet without salty. No joy without sorrow. No life without death. No attraction without repulsion. Imagine someone out there setting an intention for something. As the thing is moving toward them, it has to be moving away from someone else. In order for them to attract, someone else must repel. That’s physics.

Even the great Jacob deGrom is not immune. In a game against the Rockies, he struck out nine batters in a row. Ten, as you know, is the record, held by the greatest Met of all, The Franchise, Tom Seaver. deGrom looked untouchable. He looked inevitable. I got excited. I texted my friends. The next batter got a hit.

*

Boy, was the guy in the truck mad. Understandably. I broke the law and put myself and others in danger, including him. He honked and yelled at me, which was freedom of expression at its finest. I stopped and turned back toward him and rode right back at him. I did that because he called me an asshole. I was wrong to blow through the stop sign, but I’m too proud to let someone call me an asshole.

God and Ben Franklin gave that man every right to shoot me dead in the street (Freedom of Worship), but he didn’t shoot me, even though I charged at him like a wild beast.

Instead of shooting me, he said, Oh, yeah?

Instead of apologizing, I said, Yeah. You don’t get to call me names.

I said this because I’m a man and deserve to be treated as such, even when I fuck up. I dared to look the man in the pickup truck in the eye and demand he treat me with basic dignity. To which he responded, You’re right. I was wrong about that.

*

Organized religion is dying but religiosity is alive and well. Prayers of Confession are all the rage.

Everybody wants confession, everybody wants some cathartic narrative for it. The guilty especially. I’m watching True Detective, Season One.

Look: Ellie Kemper should not have been in that Veiled Prophet debutant ball mostly because debutant balls are dumb, but raking her over the Twitter-coals until she apologized did nothing good. She was nineteen. At nineteen she was just as much a Victim of the Patriarchy as a Perpetrator of White Supremacy, but the crowd demanded atonement. Atonement for what? For being born into and participating in the life of a particular place with particular people at a particular time?

Maybe you never had to navigate growing up with racists. Maybe you never had to navigate the complexity of loving racists. Or being loved by racists. Maybe you never had to do the emotional labor of depending on racists to drive you to the hospital. Of knowing racists are more than their racism. Knowing they are capable of great acts of love, which make them beautifully human, but makes their racism more stark, more deliberate, more sinful, awful, frustrating, heartbreaking. Of having to choose as a child, then as an adolescent, between participating or feeling completely alone. In a time and a place where there were no counselors, or the counselors were also racist. Maybe you’ve never had to parse out different subcategories of racism as you try to discern which relationships are worth it, whatever that might mean, and which are completely irredeemable, and then finding the courage to act accordingly. If you haven’t, you’re lucky. Privileged, even.

Twitter got its confession, but neither you, nor I, nor Ellie Kemper, nor America is any less racist for it. I submit that Twitter only got its confession because Ellie Kemper was already prone to introspection, has been introspecting most of her life, and has done more introspecting than the average Twitter-activist. She didn’t change her mind, she was forced to dig up her past shit and lay it on the table to be picked over by people who only just took a seat. The new arrivals took a look at the shit and said, Boy that stinks. Then they felt better, and Ellie Kemper felt worse, and nothing else changed and that’s called progress.

*

My tension and adrenaline drained away. I saw his face, his particular face. He wasn’t a Man In a Pickup Truck, representative of everyman in a pickup truck; he was who he was. He had a round nose and bags under his eyes. Two or three days of stubble on his cheeks and chin. I wonder if he has grandchildren who complain about how scratchy it is? He looked scared, like a tired man who’d almost hit a careless cyclist. He didn’t to kill anyone and he was angry that I almost caused him to kill someone. I didn’t want this man to kill anyone, and I certainly didn’t want him to kill me.

It was then that I apologized for blowing right through the stop sign. Well, I was wrong about that.

He looked a little confused. It was a confusing situation. So, he said, we’re good then?

I felt a little confused. Weren’t we supposed to keep yelling?

We’re good then, I said.

His last words to me were either, I love that, or I love you. I’m 99% sure he said, I love that, but isn’t it pretty to think that he said, I love you?

*

Listen: it’s not that I’m anti-confession, but I’m wary and increasingly wary of proforma Prayers of Confession, especially when they are religiously proscribed by a demographic that claims to be Not Religious. (In the words of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: Ask them a question and you are told the answer is to repeat a mantra.) Public confessions do, for better or worse, what religion does, for better or worse: tell us a story, give us a sense of control, shape our experience, and help us think we’re actually doing something – Look what we did, we extracted a confession! Private confessions don’t provide narrative, characters, or catharsis. All they offer is humanity, complexity, intimacy, vulnerability, and, occasionally, transformation.

*

I’m working on non-attachment, and, accordingly, on non-judgment, judgement being a form of attachment to the story we tell ourselves about how things should be.

It’s difficult. I remain attached to the story that thirteen-year-old boys should be allowed to grow up, no matter how much they fuck up when they are thirteen-years-old, therefore I judge the officer who killed Adam Toledo. I judge the adult who gave the boy a gun and showed him how to shoot. I judge the people who made the gun and all the hands that carried the gun to the boy. I judge people who love guns more than they love thirteen-year-old boys.

*