#historical knitting

Text

OK, so I've been knitting since 2010, and I just learned 2 things.

[1] Magic loop was invented around 2002

[2] Circular needles were invented in the 1910s

That means that, if you were knitting as recently as just over 100 years ago, you either were knitting with straight needles or with double points

??????????????

I fucking hate straight needles, and I fucking despise double points [personally, I know not everyone does]

I like to imagine knitting as this craft that goes back hundreds of years and connects me to history and all that. And in some ways it is

But then I find out that I've been ALIVE longer than the magic loop method? If my grandmother had been able to teach me to knit [she died around the time I was born but was apparently a very experienced knitter], she wouldn't have even known what magic loop was???????

I also wonder if I would have even liked knitting at all If I was stuck with straight needles and double points

Idk my mind is blown over this and I guess I just need to remember that my knitting is a modern craft that is only in some ways related to historical knitting

400 notes

·

View notes

Text

Knitting in Victorian England

I wrote this for a class on Victorian Literature because my professor let me research knittinf and make a cape instead of writing a literary analysis paper. The cape that is discussed from The Art of Knitting is what I created for this project, with the illustration from the book on the top right and the cape I knit on the left. The book is from 1892 and is free on Internet Archive, and Engineering Knits on YouTube made a wonderful video about it. (More photos of the cape at the end!)

Knitting experienced a surge of popularity in Victorian England, and was even a topic of discussion in Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre. After gaining popularity due to industrialization, knitting became a common pastime for women. Knitting was important because it existed as a way for Victorian women of all classes to be seen as virtuous and gave them the look of domesticity, while additionally functioning as a means of income for working-class women by either knitting or writing about knitting.

Industrialization shifted the view of knitting from economic necessity to a fashionable pastime for gentry women. In 1589 the first mechanical knitting machine was invented in Nottingham, which industrialized the knitting industry (“The History of Hand-Knitting"). Dyed wool trade with Germany and the subsequent booming industry of knitting pattern books turned knitting into something more accessible and artistic than solely practical (Rutt 112). Knitting became popular and fashionable for gentry women around 1835 (Rutt 111). Women of all classes have knitted long before the Victorian period, but the industrial changes shifted knitting to a popular and fashionable pastime for gentry women, in addition to the economic necessity for working-class women.

Knitting served as a way to keep women wholesomely busy. In The Art of Knitting, a quote from the beginning by Richter reads “A letter or a book distracts a woman more than four pair of stockings knit by herself” (qtd in The Art of Knitting 2). Knitting kept women busy without opening them up to new ideas that came from letters and books. Furthermore, a writer in The Magazine of Domestic Economy writes how useless the items (upper-class) women made were, but praises knitting in its effort “to rid of those hours which, but for their aid, might not be so innocently disposed of” (qtd in Rutt 112). Concentrating on knitting produces something at the end of the hours of challenging work but does not expose women to any material that the Victorians would deem dangerous or immoral. Thus, even when women made something useless, they were keeping themselves busy in a virtuous way.

Knitting also gave women the feminine and domestic look that was expected of them in the Victorian era. This can be seen in Jane Eyre with Jane’s description of Mrs. Fairfax upon their meeting. Jane thinks, “[Mrs. Fairfax] was occupied in knitting; a large cat sat demurely at her feet; nothing in short was wanting to complete the beau-ideal of domestic comfort” (Bronte 145). This is the first time the reader sees Mrs. Fairfax, surrounded by a warm fire, a cat and engaged in a feminine pastime. She is the image of domesticity. Jane admires Mrs. Fairfax, in part, for the comfort her nature, including knitting, brings. Mrs. Fairfax shows the role knitting plays into the idea of women as domestic creatures.

Certain forms of knitting made women appear elegant. Frances Lambert, author of 1842 manual The Handbook of Needlework, advises women to knit using the common Dutch knitting method, in which the yarn is held over the fingers of the left hand and the needles pointed upwards, because it was seen as a more elegant style of knitting (Rutt 113). While Rutt notes that this method was a faster way of knitting, Lambert does not comment on this, but instead focuses on its aesthetic qualities. This style of knitting was popular because it allowed for the look of style that was mandatory in women’s lives.

While gentry women were often restricted to making less practical knit items, some knitting authors disparaged this for frivolity and immorality. Working-class women did not have this criticism as the things they made were out of practicality and meant for regular use. In picking yarn color and material, Mlle Riego de la Branchardiere, author of Ladies Handbook of Knitting, Netting and Crochet writes “...and let her be careful to make all she does a sacrifice acceptable to her God” (qtd in Rutt 116). Rutt asserts that although Victorian knitting is seen as producing useless knits, some authors disparaged this (117). They instead encouraged women to focus on what they saw as the spiritual aspects rather than on aesthetics, as everything women did, including knitting, should enhance their virtue.

While knitting was popular as a pastime, it was still used out of economic need and served as a way for working-class women to earn money. Knitting was taught in orphanages and poor houses, with the first knitting school opened in Lincoln, Leicester, and York in the late 1500s. One school in Yorkshire was established for boys and girls who were “not in affluence” (“The History of Hand-Knitting"). The first knitting book, titled The National Society's Instructions on Needlework and Knitting, published in 1838, was an instructional manual for teachers to teach poor students the art of knitting and needlework. Knitting was used as a personal hobby, but also as a way for working-class people to support themselves.

The importance of knitting to working-class women can be seen in Jane Eyre. St John tells Jane, “It is a village school: your scholars will be only poor girls—cottagers’ children—at the best, farmers’ daughters. Knitting, sewing, reading, writing, ciphering, will be all you will have to teach” (Bronte 541). Knitting will be a way for these young girls to get jobs and to be able to make clothes for themselves and their families. In this way, knitting was more than a fashionable and artistic hobby, but a necessity for many working-class women.

In addition to manufacturing knitwear, women were able to make substantial livings writing about knitting. There was a boom in knitting and needlework publications during the 19th century (“The History of Hand-Knitting"). Some, such as The Art of Knitting, were published directly by publishers with no one associated author. Others were authored by women and were immensely successful. Cornelia Mee, who published shorter pamphlet-type knitting books, sold over 300,000 copies during their run in print (Rutt 115). Francis Lambert, author of two editions of My Knitting Book, sold a combined 65,000 copies and was translated into several languages across Europe (Rutt 113). Knitting gave working-class women opportunities to earn money, whether it was making knitwear or writing about knitting.

Knitting manuals contained various topics, such as some focusing on the religious and virtuous aspects of knitting as discussed previously, but most, if not all, had patterns in them. Under the chapter “Hoods, Capes, Shawls, Jackets, Fascinators, Petticoats, Leggings, Slippers, etc., etc.” in The Art of Knitting there is a pattern to knit a cape. Victorian knitting patterns tended to be broad and vague. Today's patterns are quite concerned with needle size and gauge, unlike many Victorian patterns. For instance, the cape pattern instructs the reader to “use quite coarse needles and work rather loosely,” (60).

Knitting was an important skill for women in the Victorian era, and they knit for a multitude of reasons. Knitting gave women the look of virtue, elegance, and domesticity. Working-class women used their knitting skills to support themselves and their families through making knitwear or writing about knitting.

Sources:

The Art of Knitting. The Butterick Publishing Co. 1892. https://archive.org/details/artofknitting00butt/page/60/mode/2up?ref=ol&vi ew=theater

Bronte, Charlotte. Jane Eyre. Planet eBooks. 1847.

“The History of Hand-Knitting" Victoria and Albert Museum.

Rutt, Richard. A History of Hand Knitting. Interweave Press. 1987. https://archive.org/details/historyofhandkni0000rutt/page/n7/mode/2up?vie w=theater

#knitting#historical knitting#history bounding#Victorian knitting#knitting history#cottagecore#victorian#knit cape#gothic#slow fashion#handmade#my knits

163 notes

·

View notes

Text

Interesting knitting insights in Knitting Stockings in Wales—A Domestic Craft, S. Minwel Tibbott in the Journel of Ethnological Studies.

1. Dyed vs undyed yarn

…it was regular practice in Cardiganshire to knit the west and toe in natural white yarn while the bulk of the stocking would be knitted in the blue-grey dyed yarn. Some informants stressed that the natural colour yarn wore better than the dyed one and therefore was more suitable for the toe-caps. A scientific reason given for knitting the welt and toe-caps in natural colour yarn was that the oil or lanolin present in it gave added warmth and protection to the wearer’s toes. The oil would also weatherproof the welts of the stocking which were often exposed to the wearer when worn above the tops of boots; they would thus readily shed any moisture. (Pg 67)

2. Methods of blocking/finishing

The completed garments were pressed beneath stocking boards (styllod sanau) and then were ready for market. These boards were cut to the shape of a stocking and informants from Cardiganshire described how a pile of stockings would be positioned between two boards and were then pressed by the weight of a heavy stone resting on the upper board for a whole week. Another method practiced in north Wales was that of placing a pre-heated board inside the stockings. (Pg 68)

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

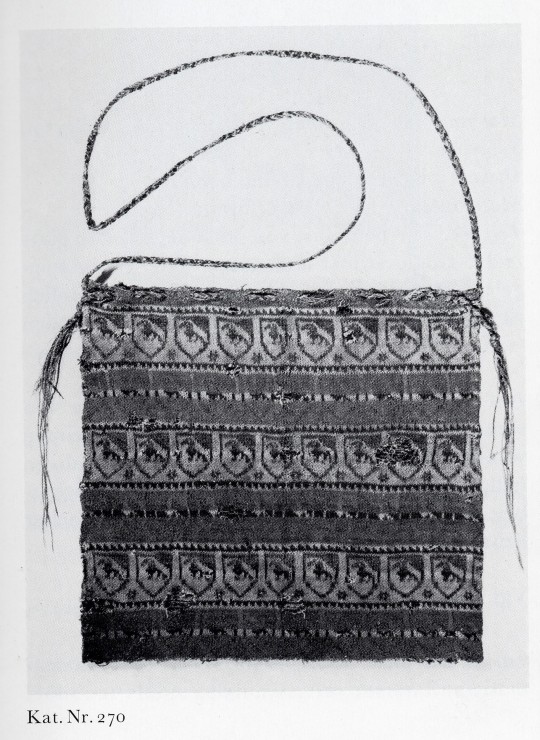

Over the weekend I used some sock yarn scraps to knit a replica of the purse found with the Gunnister Man! The pattern I used included lots of fun info, including instructions on how to copy the really unusual cast-on he used, & the fact that he had an unfinished knitting project in another one of his pockets.

It was really fun & I want to knit more sometime! I ended up making this one a few inches longer to hold my phone & wallet, so some of the colorwork is me doodling instead of a direct copy. Maybe I'll pick 'accurate' colors in the future, but hey, I figure if he had access to a broader range of colors, maybe he'd've used a little hot pink too. 🧶

#knitblr#knitters of tumblr#historical knitting#Gunnister Man#bog body#my knitting#i am thinking of using this specifically at the renn faire but i'm sure other ideas will pop up for me at some point#Also honestly the unfinished knitting project bit was mostly NOT fun to learn it made me sad he didn't get to finish it.#but it was nice to have a moment of recognition with someone from long ago!! as a guy who also often has unfinished knitting in his pockets

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

I knit the 1880s glove from Knitty, dapted by Franklin Habit from Weldon's Practical Knitter, 1st Series (1880s)

I used a sock yarn that I dyed. The original colour was a steel blue and I wanted it to be brown but it turned out more rust red

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

I made this welsh wig a while ago out of real wool. These were a very popular type of hat in the victorian era. Also seen in amc The Terror 2018. Should I start selling these??

#the terror#the franklin expedition#amc the terror#knitting#hand knitted#knitwear#wool#history#historical knitting

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

WIP: Sion Relic-Purse V - revenge of the birds

Apparently it's time for me to start another incredibly punishing knitting project and break out the crochet thread. I picked Sion V, as I haven't done this pattern yet and the birdies are DARLING. The extant is supposed to be frankly garishly colored, beige and blue birdies alternated with red and green birdies, and purple and white interstitial bands.

“Each band is composed of identical shields, with a small star at the bottom of the space between each two shields. The bands of shields are staggered by a lateral half-drop; each carries a bird. The bands alternate: one band of beige with the shields outlined and decorated in blue, one band of red with shields in green; all bands counter-changed with stripes across the middle of the shields in which the colors are reversed. The bands of shields are separated by a narrow saw-tooth design in violet and white.”

-Richard Rutt, on Sion V

I chose to change some of the colors for the preferences of the modern-day recipient while still maintaining the spirit of the wildly colored original. I swapped the beige for more white, the red for a different shade of green, and the violet for a lovely maroon. I did all this color swapping and planning in GIMP 2.8, comparing an approximation of the extant's coloration and different combinations of the colors I'd like to use. All in all I'm delighted with the way the colors are coming out.

Considering this is my third sion bag and it's been more than 3 years since my first, I'm not surprised that my tension is a lot more consistent and resulting in a lovely texture on the front of the design. I've only bothered tacking down floats on stretches of 9 or more, which only occur at 2 points in the pattern. I'd love to see a picture of the inside of the extant, to know if the artisan tacked ANY floats down, or relied on their own consistency of stitching. Is the bag lined? I have so many questions and have struggled finding answers.

I originally cast on August 15, 2023, on 2.00mm needles and 10 crochet thread. My original plan was with 18 repeats, as the extant seems to have that many. However, 18 repeats of an 18 stitch large pattern resulted in 324 stitches, a number that I struggled to keep on the needles and seemed overall unwieldy after knitting 15 rows. I then tried 15 repeats (270), which was similarly unwieldy. I settled on 12 repeats at 216 stitches (or 54 on each needle), having knit and ripped out more than 2000 stitches in the search for the Right Count.

Somewhere along the way, I seem to have knit two stitches together between the bottom of the first stripe of blue shields and the top of the first stripe of green shields. After much searching, no culprit showed, so I've included a sneaky m1L near the BOR jog. Fixing dumb mistakes is period, look at the Pourpoint of Charles de Blois.

I also finally made a needle cozy for my 8 inch us0s, since they dont fit in the cozy i use for my 6 inch sock needles. No more stitches slipping and dropping!!!

You may notice my birdies face the opposite direction of those on the shields. I encourage you not to notice this fact. One thing this project has proven to me is that even when I think i understand the geometry involved in a knitting project, I am bound to make mistakes.

When I finish this, I think I'd like to submit it for competition unlined to show off the floats, then I'd like to line it before giving it to the recipient for use. I don't want anybody worried about messing up the bag by using it.

#sca#arts & sciences#a&s#society for creative anachronism#historical knitting#knitting#colorwork knitting#wip#thank you for tolerating my rambly WIP post

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

A handknitted Italian jacket, c.17th century. From the V&A's description: "Knitted silk jackets were fashionable in the early 17th century as informal dress. This example is very finely knit by hand in plain silk yarn and silk partially wrapped in silver thread, in contrasting colours of blue and yellow. Characteristic of this style of jacket, it has a border of basket weave stitch and an abstract floral design worked in stocking and reverse stocking stitches. The pattern imitates the designs seen in woven silk textiles. The jacket is finely finished with the sleeves lined in silk and completed with knitted cuffs. Along each centre front, a narrow strip of linen covered in blue silk has been added, with button holes and passementerie buttons, worked in silver thread."

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another current project, a Tudor cap made for a friend in the reenactment group I play in (SCA). The pattern is based after the style of several portraits, notably Prince Arthur's. I'm on the front brim right now with the wider back brim to go. Then my friend will do the felting to fit it to his head.

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm curious, would these victorian patterns also include gauge the way modern patterns do (as in number of stitches per inch in stockinette), or something similar? Or did you just have to hope your gauge was the same as the pattern maker's and hope for the best?

I have never seen a Victorian knitting manual say anything about a gauge swatch. I don’t think the concept had come to be yet. The most that early writers of knitting manuals have to say about the matter is that a knitter should be careful to knit neither too loose nor too tight, but to keep a medium tension.

A YouTube video by Roxanne Richardson describes her attempting to take on a late 19th-century stocking pattern, only to become confused when the number of stitches and rows given for each part of the stocking produced something that didn't fit her foot. She eventually discovered that these patterns were probably distilled from 16th-century stocking-making philosophy that laid out what proportions a stocking should be knit to based on some kind of ideal (e.g. the circumference of the thigh is equal to 1 1/3 the length of the foot, the circumference around the ankle is the same as the circumference at the ball of the foot, &c.). The Victorian pattern used these same imagined proportions across all of the sizes that it gave instructions for, but provided no insight on how to alter the pattern if your body differed from them. She says "they'll tell you how many to cast on, how many rounds to work straight, how many decreases to work over how many rounds [...]. They never tell you what the gauge is! Stitch gauge or row gauge. So you don't know what size this stocking is." (time stamp 26:48)

More information than you asked for:

The thing about these manuals is that some of them claim to be able to teach someone to knit from scratch, but they’re nigh incomprehensible unless (and often even if) you have a good deal of experience knitting. There are a lot of things that aren’t specified (e.g. the text says “repeat”—but from where? Or the stitch repeat is clear, but it doesn't go evenly into the number of stitches you have. Or the pattern just sort of... ends before the garment is finished), and there are a lot of errata. In many places, you need to be able to figure out what something should look like from the name or description of the stitch, or from knowing what the garment the pattern is for is shaped like, and then figure out the appropriate actions to take to bring that to fruition.

There was also no language of the type used in patterns today, which ime is almost entirely standardised (knit, purl/pearl, K2Tog, Sl1-K1-PSSO, &c.). Patterns were often rendered entirely in longhand prose. Writers generally used “plain” or “knit” for what we would call a knit stitch, and “turned” (n. “turn stitch” or “turned stitch”; v. “turn a stitch”) or “back stitch” or “pearl stitch” for what we would call a pearl stitch. Usually K2Tog and P2Tog are rendered “knit two stitches / loops together” or “take two together,” and “knit two stitches together in turn stitch” or “turn two together,” respectively. Yarning over is generally “make a stitch” or "make a loop." Past this, there is almost no consensus on terminology.

Writers generally got around how long and unwieldy a pattern would be if complex stitches needed to be described anew each time they appeared by creating an index, which gave a brief phrase (or a symbol!!) followed by a description of how to perform that stitch or series of stitches. A lot of these can be ‘translated’ pretty 1:1 with modern stitch notation; others I had never seen called for.

[Jane Gaugain, The lady's assistant. Index shewing symbols such as "O," "O sub B," "S sub upside-down F" etc. and explaining each with a sentence or a few words of instruction.]

One thing I’ve noticed, though, is that some writers will describe a sequence of actions taken, whereas modern notation prefers to notate stitches created. The Winchester Fancy Needlework Instructor, for example, often tells you to bring the yarn forward and then knit the next stitch, which pair of actions will do of course create what we would call a yarn over; a modern pattern would tend to just say “YO” and expect you to know which actions to perform to create that YO based on what kind of stitch the previous and next stitches are (yarn forward if between two K stitches, yarn around if between two P stitches, yarn, yarn backwards if between a P and a K stitch &c.). As a consequence, these knitting manuals often have separate index entries or symbols for each of these actions (as above), though we would consider them to create the same ‘type’ of stitch.

Sometimes a writer seems to have simply messed up and included a phrase in a pattern that was not descried in the index (Workwoman's Guide—otherwise one of the clearer ones out there—asks me to "Put the needle into two stitches, and knit them backwards." Does this mean to purl them? K2Tog tbl?). No other instance of the word "backwards" appears in the book. The author also wrote a pattern that calls for a stitch that was not mentioned in the "stitches" section—it instructs me to

Set on an even number of stitches,

Knit the second row in the Hole-stitch, the next row in Turn-stitch, and so on.

But nothing in the book has been described as "hole-stitch." So you have to look for other patterns that use this stitch, ask yourself what it makes sense for these garments to look like, assume what this might look like from the name (it has. holes in it?) and guess what you're supposed to do to make that happen (perhaps a plain open stitch alternating YO and K2Tog), hunt for engravings illustrating an object intended to be made with this stitch, &c. Or maybe on the description of another stitch (the embossed diamond from this same volume!) the instructions on how to repeat the pattern create completely senseless results, so you have to use the first few correct rows + an assumption about what the stitch should look like (you know.... like diamonds...) to figure out how the rest should go.

So, yeah. Tackling Victorian knitting patterns. Not for the faint of heart.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

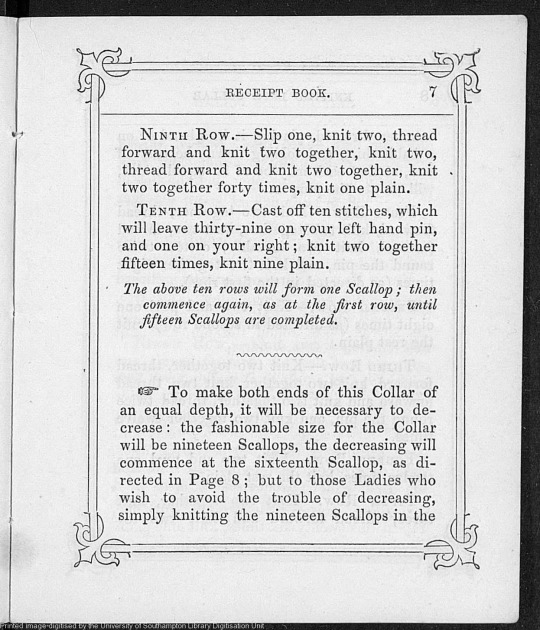

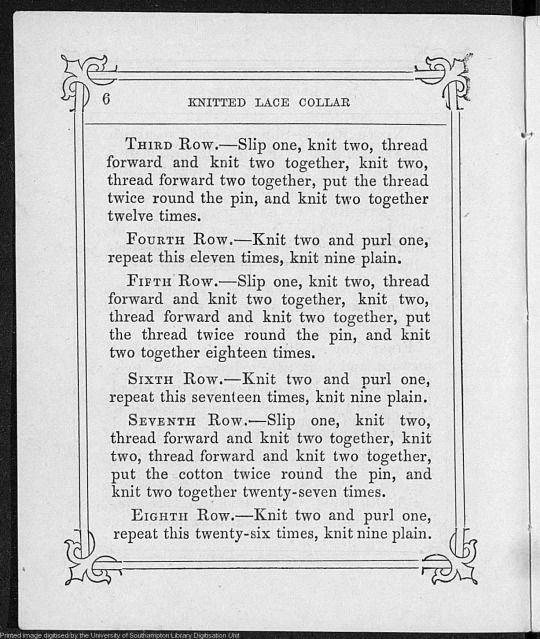

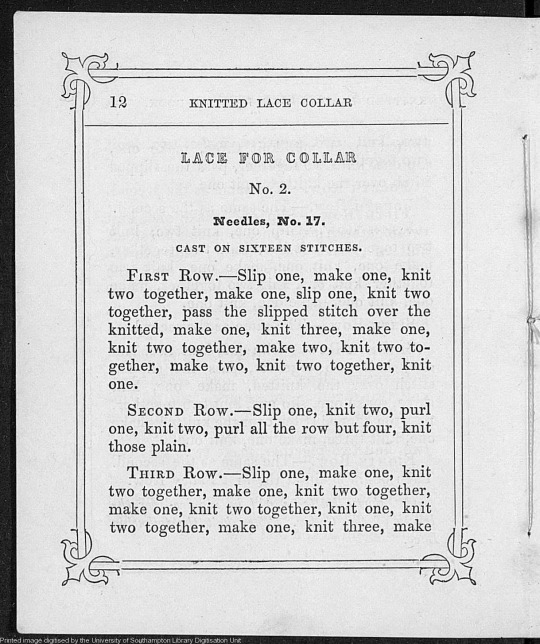

Pattern for lace collar no. 1 is above, Lace collar no. 2 is below!

Today we have a big dump of victorian knitting patterns from 1846 by Mrs. G. J. Baynes!

Just saw that tumblr fixed the image issues and upped the max image amount and it's wonderful. Now I can do these two without having to break them up into parts!

The alt text for some reason doesn't let me backspace anymore to correct mistakes, so I have to use notepad to transcribe, but all in all it's much better haha.

an fyi for newbie knitters, make refers to increasing. so Make one is increase one.

CORRECTION: It was brought to my attention by @the-fibre-stuff that it's supposed to be yarn over/ yarn forward stitch and not the M1 or M1l Stitch. Big thanks to them for pointing that out! and you can see photos of my (failed) sampler attempts in my reply to them!

Bonus image:

#knitting#historical knitting#historical knitting patterns#victorian knitting#victorian#early victorian#1840's#1840's fashion#victorian knitting patterns#collars

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Rox really does rock.

#knitting#video#historical knitting#purl#purling#purls#purl stitch#fashion#fashion history#youtube#spinning#textile history#history#stocking knitting#knitting in art#knitblr#Roxanne Richardson#rox rocks

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The waistcoat I knitted clashes wonderfully with the rest of my boy clothes 😂

#i had already started knitting it before i got the breeches#otherwise I'd have chosen a different color#knit#knitting#knitwear#historical knitting#historical clothing#living history#living history museum

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fancy mittens from Ladies Home Journal October 1885.

I finally finished these mittens! I started them last year as part of translating the pattern to something a contemporary knitter could use. I have written up the notes for the pattern but I haven't actually got the pattern to a publishable form. Not sure if I am going to. Let me know if you think I should maybe that will motivate me.

#knitting#historybounding#victorian#victorianmittens#historical knitting#knittinghistory#historicalmittens#fancy mittens

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Parasol

c.1805

Europe

LACMA (Accession Number: M.67.8.123)

#parasol#fashion history#historical fashion#1800s#1805#19th century#empire era#accessories#silk#knit#fringe#europe#lacma#popular

2K notes

·

View notes