#how to phylogeny

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Bird-reptiles is a butterfly-moth situation?

Precisely! These kinds of situations show us how wrong we have been for so long about the relationships among various animals. The pretty little boxes we like to make are often very, very wrong, phylogenetically, i.e., they are not compatible with the *actual* relationships among the organisms.

Here are a few other mind-fucks that have come to light as a result of modern methods being applied to traditional categories that turned out to be wrong:

• Snakes are lizards

• Termites are cockroaches

• Birds belong to lizard-hipped dinosaurs (Saurischia), not the bird-hipped ones (Ornithischia)

• All tetrapods are fish

• Insects are crustaceans

#the more you know#science#phylogeny#taxonomy#I find these kinds of situations hilarious#but also beautiful#they show us just how much we have learned over the last few centuries#many of these revelations simply could not have been interpreted correctly without the light of modern methods#and I think that's beautiful#Who knows what kinds of additional mindfucks await us#Answers by Mark

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Biology is so crazy

Like what do you mean this fucken thing is more closely related to humans than to other goopy looking things like jellyfish?

Like cmon

Insane

#salps are such cool little goobers#shoutout to their larval notochord#and how falcons are closer to parrots than other birds of prey like hawks#I love phylogeny and evolution#funny#meme#funny meme#biology#zoology#tunicates#evolution#phylogeny#animals#marine biology

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

I cannot jive with the idea of or with people who insist on tes books being accurate at all times, a large amount of them come off like books you find from weird dudes in the 1800s who had some Thoughts and Theories and Scientific Ideas that are just, y'know. wrong. Also propaganda in various ranges of Obvious to so subtle you don't notice if you aren't actively conscious of trying to catch it. Especially in a world where access to publishing books is way more difficult and the privileged and those with governmental and religious ties would have more access to this

It's not like modern literature or science is fully objective, devoid of propaganda, and 100% scientifically accurate either. I think it's fun and refreshing when literature in series aren't just "we tell you about lore and mechanics all of this is objectively true and somehow there are no varying (and misremembered or lied about) accounts on some of these things on paper and progress on something was entirely, neatly linear and without recorded failures" man idk have a little fun, especially a series where so much shit needs to be filled in and interpreted with so much leeway to do so

#anyway if anyone tries to tell me racial phylogeny is how things HAVE to work I'm hitting them in the head with a wood chair#I just know there are people out there take all the literature about the tribunal as all sincere and true and not tailored propaganda#vena vents#not art

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

not even joking i should get an extension on this upcoming project for bereavement :( due on monday afternoon and i haven't even started

#it's been difficult to do anything uni related this week#at least this project has a fun component - i get to take a crack at building a phylogeny again#haven't done that since last semester and i kinda forgot how so it's nice to relearn it#like hm i need a highly conserved mitochondrial gene... but which?! ah yes my friend COI of course :)#but then i have to write a paper and make a presentation for it. not fun. don't like that part

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

ONE of these fucks does NOT belong.

#shitpost?#instead of taking my meds i went and looked at taxonomy stuff on wikipedia#i mean i already *knew* about the whale thing#but it's still wild to me that most of these are more closely related to the whale than the odd-man-out here#so very fun evolution is#i have so much fun learning about taxonomic classifications and wild shit like that#and gene sequencing and how fuckin' morphology can be a vastly inaccurate tell-er-apart-er for true genomic relationships#oh how much FUN i have with the fun little phylogeny graphy thingies#i should go to bed

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

being a student is so crazy because how am i supposed to care about creating phylogenies when i have to deal with the Horrors

#applied to subjects other than bio but i was looking at my bio paper sitting in front of me as i typed this#also how am i supposed to care about restored behaviors#(< average theatre major)#anyways gang i am Going Through it#college#student#student life#college life#idfk man#do tags for reach even work here#studyblr#biology#phylogenies#or whatever#nerd#i give up /j

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

about to get wild tonight… found an insect field guide (!!!) while going through the garage with my mom today and oh buddy. it’s from 1970, so obviously there’s some holes from the missing half a century of research and discovery (it still relies on a near entirely structure based system of phylogeny!!), but for what we knew from 1970 it is comprehensive!!! anyways I’m about to have a few drinks and go HAM on this thing so prepare. I’m gonna be full fucking up on insect facts after this you have no IDEA.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Look at these idiots. They're holding hands. I just didn't wanna draw said hands.

As with previous OC sketches, details about them are under the read more. There's a lot of overlap because, obviously, Edwyn and Ingja are a couple.

Edwyn Verne

Edwyn never felt the strongest of ties to his homeland of High Rock. He had no family so to speak of, and never really had the confidence to settle down anywhere for long. It was just him, his handful of books, and his conjurations for company and had been that way since he was a young teen... but even then, he had difficulty controlling the conjurations.

Once the Great War was over, just as he reached adulthood, he decided to try and hone his magic, and ventured over the border into Skyrim, to join the College of Winterhold. His studies were going incredibly well after just a few months there, and he had made extensive progress in taming his wolf familiar, Spectre. But one day, a little rabbit interrupted them, sending Spectre crazy as he began to chase the creature - unfortunately injuring Ingja, who had been out hunting in the frozen lands around Winterhold, in the process.

After helping to return the injured Ingja to Winterhold, she begrudgingly offers to thank him with a drink at the inn. One drink turned to two, and a night out in thanks turns to numerous nights out, and even a few days, as a curiosity in magic had been ignited in her and he had offered to teach her.

He falls for her hard over those few month - just as she did for him. Unfortunately, their first kiss gets disturbed by her brother, and Edwyn ends up with a bounty on his head for 'clearly controlling Ingja with his foul magic', when he didn't know an ounce of illusion magic - not that her family knew or cared for the differences between the schools of magic, it was all the same for them.

But that doesn't deter them from seeing each other. Or running away from Winterhold together, for that matter. Or getting married and even having a child, their beloved daugher Elyse.

They find themselves in High Rock once more, and he takes on various teaching positions to try and earn money whilst Ingja takes on more dangerous tasks as a hunter and mercenary for hire. He would constantly fret about her any time that she was gone for more than a day, though always hid his worry from the ever-curious Elyse, and would relish in the relief whenever she would return home.

As soon as they had enough money to do so, the family moved to somewhere more stable - Chorrol. Life almost seemed perfect... until the love of his life began to fade away before his eyes.

Ingja Frosthand

Ingja had always been taught never to interact with and never trust the mages in the College, and she had no reason not to believe that. Unless it came from her mother, who always seemed to have a bone to pick with her and only seemed to care about her younger brother. She only really cared about what her father thought on matters though, and that was what he believed.

One of her favourite pasttimes had always been hunting from as soon as she was taught to wield a bow, which even in spite of the lands around Winterhold being sparce, she could easily spend days upon days exploring the environment and making sure that her family could eat well for a time. On one of her hunting trips, following an argument with her mother, she ends up getting injured as a result of Edwyn's experiments with his conjurations. He helped her return to Winterhold, and though it went against every instinct in her body, because he was a mage, she offered to buy him a drink in thanks.

Much to her surprise... she realises that Edwyn, and in turn the mages in the College, were just as much people as she and the other residents of Winterhold were. And she found his clumsiness and enthusiasm to be endearing... and she fell in love with him after asking him to teach her how to use magic herself. On the day that she finally created a flame with his tutelage, she couldn't help but pull him in for a kiss... just for her brother to witness it, freak out, and run to tell her parents.

Enraged that her father had the gall to get a bounty placed on Edwyn's head, and to ground her in spite of her being an adult in her own right whilst also planning to have her sent away from Winterhold to distance her from Edwyn, she manages to earn her way into the College before planning to run away with Edwyn so that they could be together.

Putting Winterhold behind her for Edwyn was one of the few reckless decisions she knew that she would never regret, especially from the moment she held their daughter in her arms for the first time. She only returned to Winterhold after thirteen years, Elyse in tow, on the day of her father's funeral. Edwyn kept himself hidden away in Windhelm on that day on her request, knowing full well that the bounty had never been removed from his head.

Though life was incredibly unstable whilst Elyse was young, her jobs putting her into increasingly dangerous situations, the day that she and Edwyn paid for a house of their own in Chorrol was enough to make her cry because she no longer needed to put herself in danger. She actually picked up some hobbies, like alchemy and baking, but never put down her bow... at least until her bones grew weary and weak, before she fell into death's grasp.

To say that she was horrified when her daughter appeared in Sovngarde saying that she was Dragonborn, and there to defeat Alduin, was an understatement.

#meg has done some drawing#skyrim oc edwyn#skyrim oc ingja#unhappy with edwyn's hair but I'm hoping adding colour will help with that.....#i've drawn them at a point in their lives where they've just about started settling down in chorrol? so they're like. early thirties?#about the time where elyse was just about a teenager or thereabouts.#elyse has the same facial features as ingja whereas almost everything else comes from edwyn because fuck the lore#if i had to pick on the spot a part of tes lore that I would get rid of it would be that 'notes on racial phylogeny' book#anyway! these two fuckers!!! they're very in love!!! they make their daughter cringe with how sappy they get with each other#edwyn is freezing cold. he is wearing a shirt which covers his neck and at least two sets of robes.#whereas ingja is just like 'let me just roll up my sleeves to cool down'.#they have vastly different temperature tolerances but he loves his ice cube of a wife and she loves her boiling hot husband#was going to draw the whiterun guard squad but not arsed at this point of the day now!!!! might even leave them be for a time.....#whoops forgot ingja's info added that in now....

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"We prefer a phenotypic definition of species" oh so we're just doing evolution denialism.

To anyone who follows me, I don't care about nor trust Colossal Biosciences anymore (The people behind the "Wooly Mice"). They have proven themselves to be headline-chasing grifters after this latest stunt. They are claiming to have de-extincted *Aenocyon dirus*, aka the Dire Wolf, by editing just 20 genes from the the DNA of a Grey Wolf (*Canis lupus*) to make this thing:

If it wasn't clear from their scientific names, Grey Wolves and Dire Wolves aren't remotely related to one another aside from being Canids, despite what pop culture like Game of Thrones would have you believe. If they did look like each other, it would have had to be via convergent evolution, as they only shared a common ancestor over 5 million years ago.

This distinction, however, isn't found in the publicized articles about this so-called resurrected Dire Wolf and makes their claim that they brought the Dire Wolf back by simply editing *20* genes from the genome of a Grey Wolf laughable. A Dire Wolf would have shared more in common genetically with a Maned Wolf (*Chrysocyon brachyurus*) or Bush Dog (*Speothos venaticus*) than it would with a Grey Wolf.

Bottom line, don't fall for whatever this company is trying to tell you. If the Dire Wolf were to be brought back, it wouldn't be via something like this, and certainly wouldn't *look* like this. If you want an idea as to how a real Dire Wolf would look like in life, here is some fantastic paleoart by artist Mauricio Antón:

Addendum: I seem to have partially miscalculated Dire Wolf genetics. They were not closer to Maned Wolves or Bush Dogs, but they were still not closely related to Grey Wolves. They were basal members of Canini, related to canids like Jackals (genus Lupulella) but distinct from them. I am sorry for this misinformation in my attempt to correct other misinformation. My main point, however, is still correct.

#for reference: phylogeny is way biologists classify living things#and phylogeny is based on the evolutionary relationships and lineages#not what they look like which is how things were done before the 19th century

18K notes

·

View notes

Text

i've been working on a research paper for my butterfly tutorial and the one thing i know for absolute certain is that eco-devo lepidopterists are absolutely obsessed with nymphalids

#melonposting#i'm writing my paper on pattern homology and phylogenetic distance right? and i've chosen to focus on eyespots cuz leps also looooove those#like when considering two species w/ eyespots -- did the same genes/mechanisms produce the eyespots in both?#and to the extent that it is the same/different i'm seeing how that correlates with how related the two species are#the intuitive idea being that if the species are closely related then it'll more likely be the same genes/mechanisms producing the eyespots#and so for part of my research i want to see the genetic/developmental basis of eyespots in non-nymphalid butterflies#(hoping to compare that with the nymphalids)#but it's allllllllll nymphalids!!!!!!!#i get one article on spots in pierid butterflies but those aren't even eyespots. c'mon now#i thought you guys loved eyespots </3 you only love them in nymphalids i guess#i'm also finding very little about the relationship between homology and phylogeny in lepidoptera. but i guess that's a bit specific huh#pubmed save me. save me google scholar

1 note

·

View note

Text

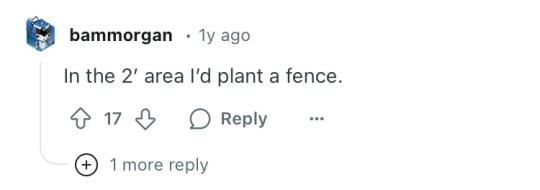

Rose genetics and the law of unintended consequences (or, ten rose bushes, reviewed)

I have a number of longposts in the backlog, including updates on a number of garden improvement projects I undertook over the winter, but I kept putting off posting them because there kept being Horrors. However, spring is here - in California anyway - and plants wait for no one.

Over the winter of 2025, as a coping mechanism for the aforementioned Horrors, I got really into roses. Because of who I am as a person, deciding what roses I wanted to buy also made me feel obliged to reconstruct the history of rose breeding, just to make sense of the teeming confusion of the tens of thousands of named rose varieties. Humans have been raising roses for food, medicine, and beauty for untold centuries, and so they've really grown up with us. The history of the development of roses, it turns out, is the history of the development of humanity in miniature.

This post has it all: history, some light phylogeny discussion, material analysis of English folk ballads, a conceptual framework for understanding how different kinds of roses vary and why, a #haul breakdown of what bare-root roses I got and what I thought of them, and some philosophical musings on what it means for an organism to be subjected to a long-term selective breeding process, to be remade wholly in the image of human desire. All that, and pictures of roses, under the cut.

My general region of California is considered to have a good climate for roses, much good may it do us. It never gets too hot or too cold, so they essentially never go out of season, and even though our winters are wet, the rest of the year is fairly dry. This is absolutely critical, because the main problem that makes garden roses hard to grow is fungal disease. Modern roses are incredibly susceptible to fungal diseases, which are caused, roughly, by Damp. This has typically been combated with toxic sprays (though there are now less-toxic options) and aggressive pruning regimens.

Needless to say, this is a ridiculous fucking problem for a plant to have. California natives, by comparison, hate irrigation - they have a natural life cycle involving being dry in summer and wet in winter, like California itself, so if you grow them in a climate resembling their natural range, without too much added water, they will be mostly OK. Roses, as far as I can tell, actually hate all water, including rain and humidity, which is much worse because gardeners do not control the weather. If it rains too often after, say, noon, the rose's leaves might get wet, fail to dry off, get a fungal disease, and die. If there is too much fog, or it is humid, as it is in most of the country in the summer, the rose's leaves might get wet &c. If you have a sprinkler system - you get the idea.

Fungal disease can also weaken roses and make them more prone to insect infestations. This is bad because modern garden roses are, without any help from The Weather, already incredibly prone to infestations from aphids, mites, beetles, and a mite-borne disease undescriptively called "rose rosette disease", which produces a habitus that I can only describe as "rose bush eldritch horror".

Now, this may all have you asking one question. Probably, that question is "why are you so obsessed with a plant that wants so badly to die?" I will not be answering this question today. Instead, I will be answering a different question, which is "Why do modern garden roses suck so bad?"

Now, if roses are subject to some manner of curse, then it isn't a family curse, phylogenically speaking. Roses - genus Rosa species extremely miscellaneous - are a member of the family Rosaceae, which contains a massive number of useful and delightful plants. It is possibly the most economically important family of plants next to the brassicas. The rose family brings us not just roses, but apples, strawberries, raspberries, blackberries, plums, peaches, apricots, and almonds. And the wild rose, untouched by human efforts, is a lot like a raspberry, actually.

Its flowers have only five petals, in pink or white. It’s got thorny stems that form thickets, and oval (or, technically, lanceolate) leaves with lightly serrated edges. Its flowers are fragrant, which is an adaptation to their long and necessary coexistence with pollinators and other insects - fragrance serves as a chemical signal for insects to "come here" or "go away", depending. The wild rose is hardy, like all wild plants, tolerant of various environmental problems that would kill a garden rose: shade, salt, normal levels of ambient insect and fungal disease pressure, drought, being consistently rained on in the afternoon or evening. It may reproduce asexually from suckers - strong shoots from near the base of the plant - and this makes it able to withstand browsing pressure from e.g. deer. (Put a pin in that.) It also can reproduce in the normal way, by having its flowers pollinated and forming seeds, which are borne in prominent reddish-orange fruits called "hips".

This is not a rose I bought, but here’s Rosa gymnocarpa, a California native rose. It’s a wood rose, so it’s shade-tolerant, and it’s often found in redwood forests specifically, so it tolerates relatively dry soil and very acidic soil.

Honorable mention: Rosa gymnocarpa (wood rose)

Source: Calscape

A raspberry plant in flower, for comparison. Source

The wild rose has another trait, which may be surprising to those who have only ever seen garden roses: it blooms once, usually in the summer. This is typical of flowers, which almost always have a season, for the exact same reason fresh fruit has a season. Flowering plants are on a tight schedule: they need to finish up their blooming, so they can set fruit, so they can get their seeds out before winter, in case the frost kills them off. And mostly we’re used to that: tulips are for spring, so you don't expect a tulip to make a second showing in fall, or to flower continuously throughout the summer. But roses have been bred to do this, and have done it for centuries, for so long we barely remember what it was like when "roses blooming" was a time of year, an event.

It's possible that for most of human history, roses were all the more treasured for being fleeting, which simply isn't an aspect of how we moderns understand roses. I am constantly subjected to traditional ballads at home, both in English and German, so I am very aware that multiple Child ballads mention roses as a way of placing the events of the ballad at a particular time of year. In 'Lady Isobel and the Elf-Knight', a song traditionally associated with May Day, one version of the chorus references the events as occurring 'as the rose is blown'. And at the start of 'Tam Lin', the protagonist meets her fairy lover while plucking a double rose, is "laid down among... the roses red" by him, and finishes the ballad on Halloween night heavily pregnant with his child. The course of the ballad is inextricably intertwined with the course of the seasons, and the bloom of roses is synonymous with early summer. (There's so much symbolism in 'Tam Lin', but especially around roses. Can I interest you in tam-lin.org at this time?)

European religious literature even uses "a rose e'er blooming" as a purely figurative phrase, something impossible and magical enough to be a metonym for the Virgin Mary - but in the modern era, most garden roses are ever-blooming. The perpetual-blooming rose is not the natural state of the rose plant, but a kind of technology that had to be developed. And I don't know, I just think that's neat.

So what have we learned? The wild rose is: once-blooming, tough, possibly shade-tolerant depending on species, very thorny, bearing simple pink or white five-petaled flowers, that are fragrant, pollinator-friendly, and produce fruit readily enough. In short, a practical, normal sort of plant.

The garden rose is…not that. There’s no other way to put this: the modern garden rose is the wild rose, but bimboified.

Now, in case today is your first day on the Internet - well, first of all, welcome, it’s bad here - but secondly, bimboification is a niche fetish where someone is transformed into a hypersexualized version of themselves that is also very stupid. Plant domestication is obviously analogous. I didn’t originate this joke; in fact, I reblogged a joke like this just last week.

Roses are like this but even more so. Like, wheat is clearly bimboified. Its sexual parts (seeds) have been remade, swollen to ludicrous proportions, and wheat is probably worse at being a plant than wild grasses. But we created modern wheat from wild grass because it was more useful that way, and wheat could in theory survive and spread without human cultivation. Roses are Like That purely because we wanted to make them a more perfect decorative object. Centuries of intensive selection pressure for appearance have rendered roses useless as an independent plant: they are so disease-prone they need extensive intervention to even survive, and they are often physically incapable of propagating themselves - one of the basic features of plants! - without human aid. That’s plant bimboification.

Source: Heirloom Roses. This one is called 'Oranges 'n' Lemons. Hardly seems like the same plant!

Here are just a few examples, of what we've done to roses. Humans love rose petals - eating them, distilling them into perfume, smelling them, just looking at them - so the garden rose has massive flowers that are so stuffed with petals that pollinators cannot get at their centers, rendering the rose incapable of reproducing except possibly with the help of a human equipped with a paintbrush. Humans love bright colors, so modern roses come in every color their natural pigments allow. Garden roses are often - though not always - less thorny than their wild cousins, because thorns are inconvenient to humans, and so have been somewhat bred out.

And what’s just as important is what was bred out of wild roses in the process of becoming modern roses - by accident. As mentioned above, modern roses are often useless to pollinators, and, not unrelatedly, can’t reproduce without human help. They often lose their fragrance, if not specifically bred for it. They are very susceptible to disease, because gardeners can keep alive, through sheer stubbornness, plants that natural selection would have culled. Likewise, they need full sun where many wild roses can get by even in the shade of big evergreens, and they can't tolerate nearly as much cold, heat, or salt exposure as their wild relatives.

This 'use it or lose it' thing, by the way, is a general principle of selective processes like plant breeding, or like evolution. If you have two independent traits, A and B, and you select hard for A, then B is likely to gradually drop out of the population, simply because the subset of A carriers that also have B is likely to be small. It's pure statistics. (It essentially is a human-created population bottleneck.) The more intense and ruthless the selection pressure, the stronger the effect. Evolution cares a lot about seed production and hardly at all about color, so wild roses are plain but make enormous rose hips; humans like beautiful roses the color of sunsets, and are indifferent to seed production, so modern roses don’t make hips at all. The failure to select for eventually becomes an implicit selection pressure against.

(Highly-bred organisms are thus less, I guess, well-rounded genetically even before you get to issues of inbreeding, and if you assume there is no biological link between your selected-for traits and other ridealong traits, e.g. domestication syndrome. Genetics is complicated!)

One adapted wild-type trait that - I speculate - was not bred out, due to its direct usefulness to humans, was the ability of roses to grow back vigorously from having leaves or branches removed. This is, it seems to me, an adaptation to herbivore browsing - if you are a rose with minimal regrowth ability, and a deer chews on half your canes, it’s curtains for you. But humans also fully remove half of the canes of their garden roses every winter - it’s critical to controlling the fungal disease that so plagues them. Specifically, pruning improves airflow through the plant, which evaporates the water that keeps falling on the leaves from the sky. (You know. The rain, that roses both hate and need to live.) In some sense, we are acting as caretakers here, shaping the plant in inscrutable ways for its own good. But to the plant, we are basically deer: just another in a long line of animals that want to steal its leaves. Unbelievable! It needs those! Fuck you too, buddy: here’s a faceful of thorns.

Truly, a tale as old as time.

This brings me to my first actual rose review, a kind of bridge between wild roses and the world of cultivated roses.

#1: Rosa rugosa, probably "Hansa"

Source: the author's yard.

This is a sucker - a vigorous young ground-level shoot - from an unnamed rosebush from my mother's house. I say "probably 'Hansa'" because we have no idea what this actually is, only that it is a rugosa hybrid, purchased from an unknown nursery in the Midwest sometime during the Bush administration.

'Hybrid rugosas' are crosses between garden-type roses and a wild rose species called Rosa rugosa, which is native to much of Asia. This particular rose bush has many traits carried over from its wild parent: it's violently fragrant, a glorious sweet-spicy combo that smells to me like childhood and home; it has wrinkly leaves (characteristic of Rosa rugosa in particular); its stems are practically coated in prickles; and it's quite tolerant of shade, drought, and salt (Rosa rugosa is a beach rose).

The main virtue evinced by this rose, derived from its wild parent, is the same reason that it is still here in my garden: it is extremely difficult to kill. My mother, after hearing me say I wanted this specific rose bush at my house the same way it had been at my childhood home, dug up a sucker from her instance, put it in a bag with some wet dirt, carried it by hand on a multi-hour cross-country plane flight, and handed it off to me. Once I received it, I stuck it in a pot, because I was ripping up my lawn and had nowhere to plant it, and mostly forgot about it, because I was busy ripping up my entire lawn. It lost its leaves suspiciously early in the fall. ("That's not good," my mother said, over FaceTime, brow furrowed. "Are the rest of your roses doing that?")

But as the saying doesn't go, "where there's green cambium, there's hope", and I continued to take care of it throughout the winter. I eventually even remembered to put it in the ground. It is now March, and in defiance of the mockery of certain judgemental housemates, who said things like "why do you have a stick in a pot?" and "it's giving 'dead', my guy", this "stick" has now decided to become a rosebush, and has a grand total of (approximately) twenty-five leaves.

Like I said: extremely difficult to kill. It is currently planted 10-ish feet from the base of a redwood tree, a tough environment where some hardy garden-style roses have nonetheless been known to thrive. Given that its resurrection has occurred entirely while it was planted under the redwood, it doesn't seem too mad about its environment.

Review: holy shit, it’s alive???

#2: Zéphirine Drouhin, the "old garden rose"

Source: Heirloom Roses

Rosarians have conceived of many groupings of garden roses, based on known ancestry, phenotype, genetic studies, and Vibes, but one major breakpoint is those bred before 1867, the "old garden roses", and after 1867, the "modern garden roses".

The old garden roses were derived mostly from ancient European and Middle Eastern stock, which had themselves been created from wild roses centuries prior. For example, this is Rosa x alba, an ancient European rose strain; it was used as the heraldic badge of the medieval House of York during the English conflict known as the War of the Roses.

Source: not mine

Some of these roses are perpetual-blooming, a trait introduced as late as the eighteenth century, and which is entirely due to trade contact with China: as far as I can tell, the genes for strong reblooming only come from the Chinese rose-breeding tradition, which was itself centuries old by that point. So the modern Western concept of perpetual-blooming roses as the default kind of rose - like so many other aspects of modernity - is a direct result of Europeans cribbing from everybody else.

Interestingly, France was a major center for rose development during the early modern period. You can see it in the way old garden roses are named: overwhelmingly after some eminent madame or monsieur. This is probably connected to the fact that Josephine, Napoleon Bonaparte’s empress, was a rose fiend: she had two hundred and fifty new varieties of rose to be brought to her gardens at Château de Malmaison, which was probably pretty much all the named varieties of rose that existed then, and many of which were new to European cultivation at that time. Again, this represented a massive inflow of rose genes that were previously restricted to other countries or continents entirely. Inextricably, these gardens also represent the proceeds of early modern global trade, and of empire: Napoleon, on campaign abroad, himself sent her hundreds of specimens of flowering plants, and the French navy confiscated plants and seeds from ships captured and sea and sent them to her.

Anyway, Zéphirine Drouhin, created at the end of the "old garden rose" period and named for some now-forgotten madame or mademoiselle, is highly fragrant - one of the few roses said to really perfume the air - with a vibrant but old-fashioned color palette. (Apricot and yellow roses were also characteristic of the Chinese rose gene pool, and so were significantly less common in old garden roses.) Zéphirine Drouhin is also thornless, a rare trait that we nonetheless see in some old-fashioned garden roses, and a few modern garden roses as well.

Old garden roses have a variable but generally good level of disease resistance. Zéphirine Drouhin in particular, gets something of a bad rap for poor disease resistance; English rose breeder David Austin Roses says, tactfully, that it "prefers warmer climates" (versus, one must assume, rainy England) and that "controlling disease can be a problem". By this you should understand them to mean that it is a whiny little pissbaby that constantly gets blackspot, a diva that will defoliate at the drop of a hat (or the drop of, uh, water).

However, unlike certain other newer roses I will mention later, I have found Zéphirine Drouhin to be pretty healthy so far. I received this rose, like many in this post, "bare root", basically a stick, dormant in a bag of wood shavings. Upon being planted in a part-sun area, it has leafed out with only a scattering of aphids to show in terms of disease.

Review: So far, so good. Looking forward to the fragrance.

#3 and 4: 'Mister Lincoln' and 'Fragrant Cloud', the hybrid tea brothers

Remember how I mentioned that 1868 is the breakpoint between "old garden roses" and "modern garden roses"? That year marked the invention of a new type of rose, the 'hybrid tea', that is in some sense THE rose, the ARCHETYPE of a rose. If you ask someone who knows nothing about roses to draw 'a rose' - if you look up clipart of a rose - a hybrid tea rose is what you'll get.

Source: Star Nursery

This is Mister Lincoln, and although it was developed as late as the 1960s, it has the classic hybrid tea rose form. Hybrid teas have a very distinctive shape, described as "high-pointed", with a spiral of unfurling petals that curl at the edges, and they're borne singly on long stems, making them great for cutting and putting into vases and bouquets. They are not always strongly fragrant, and they are not generally very disease-resistant. They come in a very wide variety of colors, intense and subtle. They are reblooming.

Hybrid teas were developed by another East-meets-West cross, when the Chinese tea roses, freshly imported from Guangzhou in the early 19th century, were bred with the old garden roses. Tea roses have the same iconic form as the hybrid teas; they have those unique, pastel shades that were previously quite absent from European rose stocks; they smell like a fresh cup of tea. All these traits they impart to hybrid teas. Hybrid teas have been very popular ever since, and have been subject to a great deal of selective breeding for color and form.

Hybrid teas don't generally spark joy, to me. I find the 'cartoon rose' shape kind of twee, honestly. And the reputation for lack of disease tolerance puts me off. But I heard Mister Lincoln was incredibly fragrant, and that drew me in. Likewise Fragrant Cloud (1967), which also has the charming feature of being a violent neon coral that is allegedly very difficult to photograph.

Source: Heirloom Roses

“It'll be fine," I thought. "How much fungal disease can it get? It's not like it's humid here."

Never again. My trust is destroyed; fuck hybrid teas.

please, my son, he is very sick

This is my poor Mister Lincoln, planted from bare-root in mid-December. It has three different fungal diseases, and also an aphid infestation I can't seem to get it to shake. It looks like one of those diagrams of a liver in a medical textbook that has fatty liver and cirrhosis and liver cancer all at once, just so you can see what all the diseases look like. This is a rose that has every problem! No other rose in this flower bed comes close to having every problem! 'Munstead Wood' is also a modern garden rose (though from a very different lineage - see my review below) and it has no fungal diseases and not a single aphid!

Well, maybe the other hybrid tea I bought is doing better... well, nope, it rained last week and Fragrant Cloud has powdery mildew.

Review: Come on, man.

#5 Unidentified ‘sunset’ rose

I didn’t buy these roses; they came with my house. As a consequence, I have no idea what they are, but I am now intimately familiar with their traits, and I think they are very indicative of both the high and low points of modern garden roses.

On the surface level, the fact that these rose bushes are still with us is an impressive proof of their persistence under adversity. When I bought the house, these roses were being choked to death. Lily-of-the-nile had been planted way too close to them, and then permitted to grow unchecked and undivided for many years; their roots were completely infiltrated and surrounded with lily roots. The lily roots had also damaged the irrigation lines, which were dribbling uncontrolled amounts of water into the shared root zone. So when I excavated these roses, the whole area smelled strongly of rot, with visible mold throughout; the roots were fully wet even in the heat of August. The roses were also infested with blackspot, not surprisingly. I wasn’t sure if what I was doing was too little, too late.

But when they finally got some drainage, some direct sunlight, and some relief from the brutal root competition, they did start growing back, and even blooming. Come winter, I pruned hard, defoliated, and applied neem oil consistently. And they’ve made a comeback!

Source: these blooms are actually my roses.

They bloom, and they’re beautiful. They do this ombre thing, where the buds are bright yellow and as they open they go from yellow, to orange, and finally to red.

The growth is fairly vigorous, with no powdery mildew no matter how rainy it gets. But their foliage definitely suffers from blackspot, and occasional rose rust; the spores are probably ambiently present in the soil now, and they can’t quite seem to defend themselves, even with ample help from organic fungicides like neem oil.

They also have no fragrance. They smell like nothing. And that’s the standard modern garden rose in a nutshell, I think: beautiful color and form, shaky disease resistance, little fragrance. It’s a little sad, honestly.

Review: Okay, this one is really pretty, actually.

Interlude: Pesticides and the law of unintended consequences

So, yeah, you can sort of see how roses got a reputation for being picky divas. I can only imagine how bad this sort of thing must get in places that get (gasp!) rain or humidity in the summer.

Now, having created plants that are too disease-ridden to live, rose-lovers came up with practical and effective solutions to the disease problem they created. For the past century or so, the go-to fix for our increasingly disease-prone rose population has been chemicals: regular applications of synthetic insecticide and fungicide sprays, as well as plenty of fertilizer and herbicide to feed the roses and kill any competing weeds.

However, recall the theme of this post: the law of unintended consequences. In agriculture, the development of modern pesticides and fertilizers has been genuinely miraculous; the Green Revolution is estimated to have saved a billion people from starvation in the latter half of the twentieth century. Saving a billion people! Can you even begin to conceive of what it would be like to save a billion people, even grapple with the moral weight of that act? I know I can't; the number is simply too large for our moral intuitions to handle, I think. So I'm hesitant to bad-mouth pesticides and fertilizers too much.

But they do have massive downsides. Chemical fertilizers leach into the groundwater and cause algal blooms that make entire bodies of water go anoxic, rendering them uninhabitable to fish and the rest of the aquatic food chain. Insecticides are probably responsible for colony collapse, which endangers the pollinators that we rely on for our food supply.

And, well, even if you don't give a shit about the natural world - you are a part of the natural world. You are an animal, with all the frailty that implies. Our bodies use many of the same ancient metabolic pathways as insects and plants; the majority of your DNA is shared with a banana. And because you are an animal, it is very difficult indeed to create an insecticide that will poison other animals without poisoning you too, at least a little. Herbicides are somehow still worse, despite the more distant biological relationship between humans and dandelions: Roundup, for instance, is linked to non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, which has led to Monsanto paying out massive legal settlements to cancer patients who used their products.

So if we can't grow roses without coating them in poison, maybe we should just… not do that? Go back to growing super-hardy nearly-wild roses like rugosas, forgoing forever the elegance and sublime color of a modern rose?

Give up this? ‘Glowing Peace’, Heirloom Roses

Not so fast! Maybe this technological problem has a technological solution. If we bred roses so that they sucked, maybe we should just not do that! Make different roses! Make roses that don't suck!

#6-#8, ‘Ebb Tide', 'Eden', and 'Lavender Crush': roses that don't suck

Over the last fifty years, people have become increasingly aware of the impacts of modern lifestyles upon our health and the health of the planet and its ecosystems. So maybe this has made the public less willing to buy roses that need to be treated constantly with toxic sprays. Or maybe it's just that growing disease-prone roses is an enormous pain in the ass. Spray, prune, spray, defoliate, fertilize, spray, fertilize, spray, water - but not too much! Oops, powdery mildew. Defoliate and spray some more.

So the genetic health of the newer varieties of garden roses is greatly improved. The two hybrid teas I struggled with above were bred in the 1960s. All the named rose varieties in this section were bred since the 1990s or later: Eden in 1997, Ebb Tide in 2004, and Lavender Crush, the baby of the group, was introduced in 2016. All of them are vibrantly healthy and quite vigorous; Ebb Tide and Eden are shade-tolerant too, and Lavender Crush is allegedly very winter-hardy. After a scant two months in the ground, they've started to put out flower buds. And they keep some of the glorious color and form of older roses. Look at them!

Source: Heirloom Roses.

I don't mean to say all 20th century roses are bad and disease-ridden. I also have purchased 'New Dawn' (introduced 1930), due to it being the fifteen-dollarest rose at the Home Depot. (My toxic trait is that I am an absolute sucker for a good deal. I don't go into TJ Maxx anymore; it's too dangerous.) 'New Dawn' has all the ancestral, throwback traits I laud here: shade-tolerance, fragrance, disease resistance. It even brings in the pollinators! But it seems to me there's been a noticeable uptick in the quality of newer rose introductions, particularly when it comes to disease resistance. I'm not wired into the professional rose world to know what that is; I'm Literally Just Some Guy. But it's a good trend.

Review: I am so excited for the buds to open, you have no idea.

#9: 'Double Knockout': the 'landscape' rose

Wait, no, I take that back. These roses have too much ease of care. Put some back.

The Knockout rose has one virtue: you cannot kill it with an axe. Literally.

This rose was planted right at the foot of a redwood tree in my garden, because the previous owner of my house was an idiot. This is a terrifically bad setup for roses and redwoods: redwoods acidify the soil, and suck up water and nutrients aggressively, leaving little for surrounding plants, and of course they provide dense shade. Roses hate the acid, the dry and low-nutrient soil, and the shade; this plant never bloomed all last summer. For their part, the redwoods hate having anything planted in their inner root zone - their roots are relatively shallow for such a large tree. This is not a good situation for anyone, so I hacked this rose back to the ground, dug out as much of the root ball as I dared, and in my naivete thought that would be the end of it. Well, it has grown back. Now I am faced with the dilemma of whether to risk root injury to my redwood tree, or just let the rose be, bloomless as it is. Probably the latter is better for the redwood tree, on the whole. Maybe it’ll get choked out if I don’t water it? Anyone’s guess, really.

The category of landscape roses is a 2000s invention. The first Knockout rose was introduced in 2000 after years of intensive selective breeding for being easy-care, free-flowering, and disease-resistant; the similar Drift line was the product of an amateur rose breeder in 2006 to much the same ends. Landscape roses are so named because instead of being demanding prima donnas suited only to those who love roses enough to take on the Rose Tasks, they’re just another pretty shrub in the landscape.

And I will say this for them: in that bad, fungal spore–inundated flower bed I mentioned, my landscape roses (plus Munstead Wood, see below) are notably free of fungal disease.

Also, I think that's leaf tissue proliferating at the center of the bottom left bloom?? A rare but harmless growth disorder of flowering plants.

This comes at a cost, of course, at least if you’re a snob like me. I don’t think landscape roses are very interesting-looking - though of course they come in a wide variety of colors, the better to coordinate with the color scheme of your house! - and they are generally, tragically, without fragrance. While I can’t complain about anything that gets US gardeners to use less pesticides, they are barely roses to me. They are, in fact, the closest roses come to being an inanimate object, a decorative thing you can just plonk down in your garden wherever, like a tacky concrete statue. They’re a commodity; the enchantment is gone. I wouldn’t rip them out where they’re well-sited, but I sure wouldn’t plant more.

Now, this is incredibly mean to people who love landscape roses, but here goes. I’m reminded of a thread from r/Ceanothus, the California native gardening subreddit, that is now burned into my brain. OP asks for a native shrub recommendation, but not just any native shrub. OP wants a native shrub that will grow very tall, but also stay very narrow - 1’ wide in places. OP needs a native shrub that will grow thick and vigorous, to block out their view of the neighbors. OP needs this thing to be evergreen; OP presumably wants low water inputs. And OP needs all this, in a shrub that will grow in full shade.

In fairness, OP was polite about it, and this is a common problem for urban gardeners. The dark, untended canyon between buildings is a very common phenomenon in Californian cities. I too have a narrow, shaded side yard containing a tiny strip of crappy, gravelly dirt, that I’d love to grow something in: how do you think I found this post? Dear reader, I am very much at that devil's sacrament.

And the ceanothusheads of r/Ceanothus tried gamely. But one commenter replied with something that fully changed how I think about gardening:

Source: Reddit

Sometimes, what you need is not a living organism, with its own needs, that will change over time in ways you may not endorse, that interacts with the world around it. Sometimes what you really want is a man-made object. Sometimes what you want to grow in your tall, narrow, lightless, bone-dry side yard, for your privacy requirements, is a fence. And that’s what I think about landscape roses. In Mediterranean and desert climates, as long as there's enough sun, you can always fall back on planting a succulent. But not every location can grow succulents outdoors year-round. In temperate climates, landscape roses could probably be successfully replaced with a particularly attractive boulder. Or, if what you want is a smart-looking, easy-care hedge: consider a fence.

Review: I’d maybe rather plant a fence a succulent.

#10: 'Munstead Wood': the old English rose, reloaded

‘Munstead Wood’, my final acquisition, is a credit to another major modern rose breeding program, this time out of England: David Austin Roses. The main idea of the David Austin rose-breeding project seems to be combining the particular charms of traditional English old garden roses - their fragrance, their romantic, sophisticated forms - with the virtues of modern roses - continuous blooming, a wide range of highly Instagrammable colors - plus disease-tolerance that twenty-first century gardeners now expect. And judging by their singular impact on the contemporary rose market, they seem to have been very successful at that goal. The Reddit reviews are glowing, the forums are abuzz for their hottest new releases (Dannahue restock wen?), their most popular roses are often sold out, and other rose sellers have catalog filters for 'English shrub roses' that allegedly share the looks and fragrance of David Austin's best.

From the author's camera roll. 'I can't believe it's not Dave [sic] Austin!'

Their marketing is also very slick. Their website is very informative, with separate filters for various kinds of roses you might want to buy ('Best for fragrance', 'For a shady spot', 'Thornless or nearly so'), all the rose varieties have literary or historical names or else are named after charming British locations, and are all beautifully photographed in their idyllic show garden, and the prose is carefully engineered to incite lust in the winter-weary gardener. They even do periodic drops of new roses, like a sneaker company.

So last November, I allowed myself to buy one David Austin rose, 'Munstead Wood'.

Source: David Austin Roses

'Munstead Wood' is really gorgeous, I think, blooming in a deep burgundy color. The website claims the fragrance is "Old Rose, with fruity notes of blackberry, blueberry and damson".

An interesting fact about 'Munstead Wood' is that it is actually region-locked. David Austin Roses sells roses in both the US and UK (and maybe other places; sorry I am so American), but the climate of the UK has been changing, with more extreme weather events and even more rain. And you know how it is with roses and the rain. 'Munstead Wood' was no longer able to thrive, and has packed up its little rucksack and gone out to explore the world as a lone vagabond - specifically, America.

So how is it doing here? Great, actually. It may have been rained on every day for the past week, but at least it's not in England, I guess.

'Munstead Wood' has no fungal disease. It looks like it's never even heard of fungal disease. I'm pretty impressed! I can't actually tell you whether the roses are good, but this is a pretty good plant, which is a good start.

Review: I'm holding myself back from buying more David Austin roses right now. God help me, I have two more open full- to part-sun spots in my garden right now.

David Austin, "Lady of Shalott". Call me the Lady of Shalott the way I'm languishing in my tower, gazing only at the mere reflections of the real world (stuck inside, looking at my phone, because of the rain) and am about to throw myself in the river with longing (to be out in the garden)

#this was mostly written like a week and a half ago#delighted to report it has now stopped raining :)#gardening#plantblr#roses#botany#...kind of. not a botanist i just like reading about it#longpost#original content#(i hesitate to call this an 'effortpost': aside from spending an hour on wikipedia trying to graph out the various old garden roses#and their relationships with the species roses that spawned them - it just kind of happened.)

159 notes

·

View notes

Text

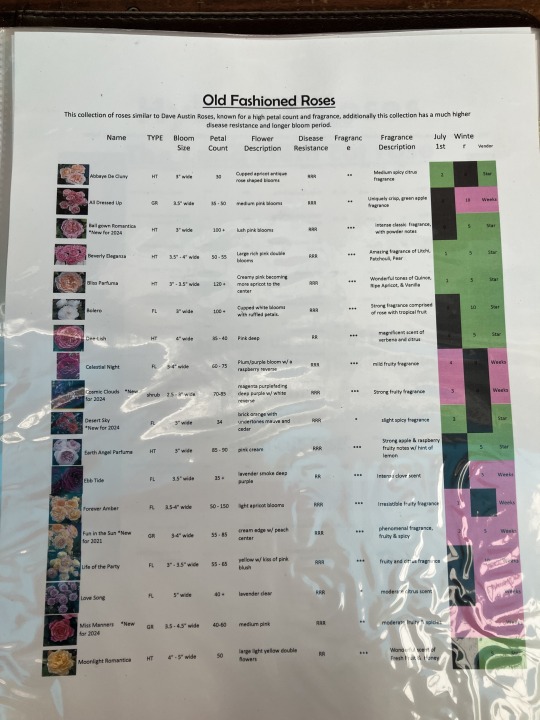

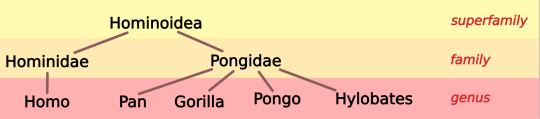

Apes are a kind of monkey, and that's ok

This is a pet peeve of mine in sci comm ESPECIALLY because many well respected scientific institutions are insistent about apes and monkeys being separate things, despite how it's been established for nearly a century that apes are just a specific kind of monkey.

Nearly every zoo I've visited that houses apes has a sign somewhere like the one below that explains the supposed distinction between the two groups, focusing on anatomy instead of phylogeny.

(Every time I see a graphic like this I age ten years) Movies even do this, especially when they want to sound credible. Take this scene from Rise of the Planet of the Apes:

This guy Franklin is presented as the authority on apes in this scene, and he treats James Franco calling a chimpanzee a monkey like it's insulting.

But when you actually look at a primate family tree, you can see that apes are on the same branch as Old World monkeys, while New World monkeys branched off much earlier.

(I'm assuming bushbabies are included as "lorises" here?)

To put it simply, that means you and I are more closely related to a baboon than a baboon is to a capuchin.

Either the definition of monkey includes apes OR we can keep using an anatomical definition and Barbary macaques get to be an ape because they're tailless.

"I've got no tails on me!"

SO

Why did all this happen? Why did we start insisting apes are monkeys, especially considering the two words were pretty much interchangeable for centuries? Well I've got one word for ya...

This the attitude that puts humans on a pedestal over other life on Earth. That there are intrinsically important features of humanity, and other living things are simply stepping stones in that direction.

At the dawn of evolutionary study, anthropocentrism was enforced by using a model called evolutionary grades. And boy howdy do I hate evolutionary grades.

Basically, a grade is a way of defining a group of animals by using anatomical "complexity". It's the idea that evolution has milestones of importance that, once reached, makes an organism into a new kind of thing. You can almost think of it like evolutionary levels. An animal "levels up" once it gains a certain trait deemed "complex".

You can probably see the issue here; that complexity is an ephemeral idea defined through subjectivity, rather than based off anything truly observable. What makes walking on 2 legs more complex than walking on four? How are tails less complex than no tails? "Complexity" in this context is unmeasurable, therefore it is unscientific. That's why evolutionary grades suck and I never want to look at one.

For primates, this meant once some of them lost their tails, grew bigger brains, and started brachiating instead of leaping, they simply "leveled up" and became apes. Despite the early recognition that apes were simply a branch of the Old World monkey family tree (1785!), the idea of grades took precedent over the phylogenetic link.

In the early years of primatology, humans were even seen as a grade "above" apes, related but separated by our upright stance and supposed far greater intelligence (this was before other apes were recognized tool users).

It wasn't until the goddamn 1970s that it was recognized all great apes should be included in the clade Hominidae alongside humanity. This was a major shift in thinking, and required not just science, but the public, to recognize just how close we are to other living species. It seems like this change has, thankfully, happened and most institutions and science respecting folks have accepted this fact. Those who don't accept it tend to have a lot more issues with science than only accepting humans as apes.

And now, we come to the current problem. Why is there a persistent idea that monkeys and apes are separate?

I want to make it clear I don't believe there was a conscious movement at play here. I think there's a lot of things going on, but there isn't some anti-monkey lobby that is hiding the truth. I think the problem is more complicated and deals with how human brains and human culture often struggle to do too many changes at once.

Now, I haven't seen any studies on this topic, so everything I say going forward is based on my own experience of how people react to learning apes (and therefore, humans) are monkeys.

First off, there is a lot of mental rearranging you have to do to accept humans as monkeys. First you, gotta accept humans as apes, then you have to stop thinking in grades and look at the family tree. Then you have to accept that apes are on the Old World monkey branch, separate from the New World monkeys.

That's a lot of steps, and I've seen science-minded zoo educators struggle with that much mental rearranging. And even while they accept this to an extent, they often find it even harder to communicate these ideas to the public.

I think this is a big reason why zoos and museums often push this idea the hardest. Convincing the public humans are apes is already a challenge, teaching them that all apes are monkeys at the same time might seem impossible.

I believe the other big reason people cling to the "apes-aren't-monkeys" idea is that it still allows for that extra bit of comforting anthropocentrism. Think of it this way; anthropocentrism puts humans on a pedestal. When you learn that humans are apes, you can either remove the pedestal and place humans with other animals, OR, you can place the apes up on the pedestal with humanity. For those that have an anthropocentric worldview, it can actually be easier to "uplift" the apes than ditch the pedestal.

Too make things worse, monkeys are such a symbol of a "primitive" animal nature that many can't accept raising them to the "level" of humanity, but removing the pedestal altogether is equally painful. So they hold tight to an outdated idea despite all the evidence. This is why there's often offense taken when an ape is called a monkey. It's tantamount to someone calling you a monkey, and that's too much of a challenge to anthropocentrism.

Personally, I think recognizing myself as a monkey is wonderful. Non-ape monkeys are as "complex" as any ape. They make tools, they have dynamic social groups, they're adapted to a wide range of environments, AND they have the best hair of all primates.

I think we should be honored to be considered one of them.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

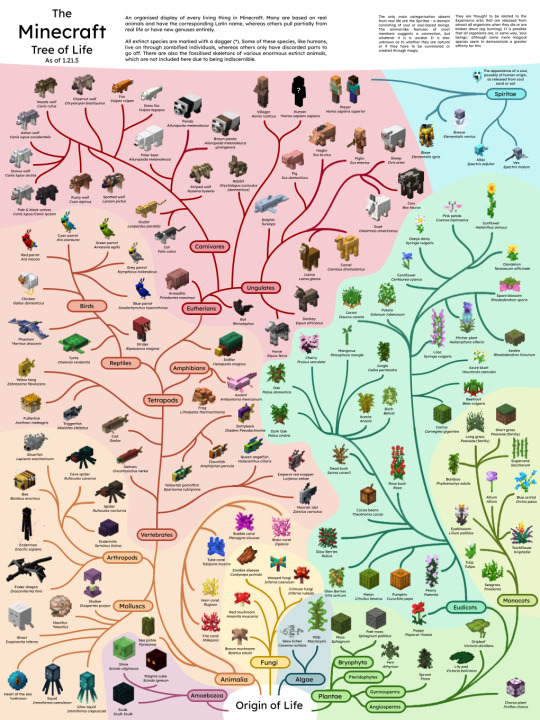

why are pandas classified as carnivores? And is there a reason why the striped wolf is seperate from the other wolves?

And while I don’t understand most of the categories, I Am most wondering about what ungulate means and why both a dolphin and a horse are in this category

Here's a big project I've been working on for a few weeks: a phylogenetic tree of everything in Minecraft! It would take ages to explain everything here, so if you want an explaination of any inclusions, exclusions, categorisations or Latin names PLEASE PLEASE PUHLEASE ask me I would love to answer any questions :3

Here's the slides I used to make it since i'm aware the text on the image there is pretty much unreadable.

Reblogs appreciated!

#minecraft#mineblr#zoology#biology#phylogeny#taxonomy#so freakin cool#I loooove this#it’s incredible#I can’t imagine how long this must’ve taken to make#just#it’s so incredible

11K notes

·

View notes

Text

i think one of the least used concepts in elder scrolls lore is its nebulous relationship to truth.

like something i do actually appreciate about that cunt kirkbride's writing in morrowind is that the mythology of the tribunal is allowed to be relatively ambiguous and there's room for poetry and fable and unreliable narrators. there's a strong general tendency in both fandom and dev to interpret lore quite literally and treat every text as reliable sources of fact about tamriel even when the text is like. fiction or written with a clear bias towards certain factions or prejudices.

the main example I'm thinking of is the 'notes on racial phylogeny' lore book. it's literally just racist pseudoscience and in a real life context would be considered unreliable and deeply offensive. but in tes, i rarely see anyone stop to actually consider that perhaps this lore isn't really a factual study of how bodies work but about how the imperial empire categorises the people it colonises and justifies it's supremacy. there's so much focus on determining the rules and metaphysical aspects of the world that there's no consideration that the way factions like the empire see the world is inherently flawed.

it's fun to think of a world where stars are literal holes punched in the fabric of the sky, or that water is made of memory, but i also think it would be a much more fun and flexible world if these theories are considered to be just a few of many lenses that people in tamriel use to try to understand their world. some of my favourite pieces of lore and world building are things like 'cherims heart of anequina' that imply a rich world of culture and art; i love the idea that tamriel has art and art critics and people who discuss ideas for other purposes than trying to figure out what's The Only True Lore.

#martin posts#tes#morrowind#the elder scrolls#ugh i do not feel that confident in my ability to analyse and write essays on stuff but i like to try anyway#when i started googling stuff i just got more confused and frustrated. these games must be very hard to write a wiki about#i would someday like to put these ideas into better words and gather more evidence. but writing it here is a start i guess

717 notes

·

View notes

Text

My phylogeny of frog monsters as of the release of wilds

The toxin toads: The most basal of this family of monstrous amphibians, these creatures can be found in a variety of habitats and take the chemical defenses common among frogs to the next level. Of the four species known, three can spew an aerosolized concoction from their mouths in self-defense, with the fourth regurgitating an explosive chyme. These toxins are potent enough to affect creatures hundreds of times their size upon contact, making them a handy species for hunters to use. It’s currently thought that these toxins are synthesized from their diet of bugs.

These creatures are, despite their basal position, already very distinct from other frogs. The genus has two sails supported by bony extensions of the ribs, a feature unique to them, which supports a dense network of blood vessels that can be constricted. This feature can be used to thermoregulate in the wide variety of environments they can be found in, constricting and reducing blood flow in cold environments to retain heat and flushing with blood to vent heat in hot environments.

The toxin toads also have very short tails, which is a feature common amongst this family. This is actually very weird for a frog as ordinarily they re-absorb their tails when transitioning from a tadpole to an adult, and genes responsible for the particular shape of the hip bones in frogs is also intrinsically linked with the re-absorption of the tail in their tadpole stage. The re-absorption of the tail allows for the specialized muscles and unique hip structure that allows frogs to jump to be present. Because of this, you can only really have one or the other.

It could be possible that the tails of the monster frogs could be extensions of the colon like the Tailed Frog, but we don’t see them squash or stretch like a boneless appendage and instead move like they have a rigid support structure. This doesn’t necessarily mean that they have vertebrae in their tails, but this is the logical conclusion. And if they are true tails then that implies that this family either descend from very early frogs or stem-frogs, splitting off before the loss of the tail as adults became hard baked into the genome of other frogs. This would also imply that their hips, and by extension how they leap, is very different from other frogs.

Armored frogs

Thorntoad: Amphibians native to the citadel and by extension the mega-forest it once was, in self defense they vomit noxious chemicals into the faces of attackers. This isn’t all too different from the toxin toads, implying that this could be an ancestral trait to the family.

Two defining features of this species are their long flexible tongues and armor.

Despite what is seen in media, frog tongues are not long or especially flexible. They are actually short and situated at the front of the mouth folded backwards, and when a frog opens its mouth to grab something the tongue flips forward into a more normal position to slap the prey item with its stickiness. So for a frog to have a long flexible tongue like that of say an anteater is rather fascinating, and could imply a diet specializing in animals that make small burrows. Unable to dig prey up, it simply sends its tongue down to probe for it.

The osteoderms, which are common among the monster frogs, is also strange as frogs famously lack scales. But that isn’t to say that they are unfamiliar with doing strange things with their skin, as many species have hard bony skin around the face and shoulders, and Leptobrachium boringii males can grow a mustache of keratinous spines during mating season. In a land with dragons and dinosaurs, large frogs might be pressured into dermal protection.

Chatacabra: Monstrous frogs with long tongues and upright limbs native to deserts. Chatacabra are perhaps most unique for their body plan that has converged with the cursorial old world monkeys such as Blagonga and Rajang, and they seem to have near similar range of movement in their limbs and can even knuckle walk. What could have possibly caused such an adaptation in a frog is unclear. While a more upright body posture would keep the underside off the hot sand, the arms are subject to guesswork. The unique range of arm movements in primates is a result of their arboreality and brachiation movements, so it could be possible that the ancestors of Chatacabra were arboreal.

The long tongue of Chatacabra seems to be a holdover from more basal armored frogs, and while still used for prey capture, is also used to smear the forelimbs with sticky mucus. This same mucus is used to attach rocks to their forelimbs to make their attacks more damaging to anything willing to attack them.

Three features present in Chatacabra are common to the rest of the monstrous frogs and is worth bringing up here. Teeth on the mandibles, claws, and supporting the organs without a ribcage.

Frogs lack teeth on their bottom jaws as they lost the genes for them 200 million years ago, but it is not impossible for the monstrous frogs to have re-evolved them. The frog Gastrotheca guentheri managed to do it, likely because the genes that tell teeth were to grow are tied to the genes for gums. Claws are also not impossible for a frog when faced with the right pressure, as the African Clawed Frog has keratinous extensions on three of its toes it uses for prey processing.

Frogs also don’t have a rib cage, and ordinarily this limits how big they can get as past a certain size their organs might threaten to fall out of their body or get jostled around. But the monstrous frogs get around this with very well developed obliquus externus and rectus abdominis muscles with a high amount of elastin to prevent damage when getting jostled around. They also have hypertrophied procoracoids, sternums, and xiphisternums to further mimic a proper ribcage.

In the desert there is rarely large long lasting water bodies for tadpoles, so Chatacabra had to develop a work-around. Much like Rain Frogs, Chatacabra mothers will dig a hole for her to lay eggs in, and these eggs will give birth to miniature fully formed Chatas via a process called direct development.

Tetranadon: Amphibians that can be found in river systems in more eastern parts of the world, Tetras are unique for their hard turtle-like shell and beak.

The species spends most time submerged and inactive for long stretches of time, as long wisps of algae are commonly seen growing off their bodies. They occasionally experience periods of activity where they forage along the bottom of water bodies, shuffling through the muck with their fleshy bill. This bill is lined with electroreceptors like a platypus, and they use it to detect prey, particularly a species of freshwater slug called Goocumbers, which is their preferred prey. Upon detection a Tetranadon then ravenously scarfs down its meal, along with the surrounding water and dirt.

The shell of a Tetranadon is composed of many large fused osteoderms, but unlike a turtle shell it is completely separate from the ribs and vertebrae. Tetranadon are also capable of standing and moving upright, and can even pick up objects with their forelimbs.

Tetsucabra: Possibly the most famous genus within this froggy family, Tetsucabra are a common sight in habitats with rocky terrain.

The species is fossorial, and creates elaborate dens and tunnels with their large claws and massive tusks. Their skulls are notoriously robust and their tusks and brows give them an intimidating appearence. They are equipped with rather flat peg shaped teeth, and this coupled with the fact they are capable of eating grains and rice indicates an omnivorous diet. Tetsu are also smart enough to be trained and tamed individuals exist, although they are very food motivated creatures.

If their powerful legs and massive jumps are unable to carry them to safety, their tough hide and powerful bite can deter attackers. They can even manipulate boulders with their mouths and toss them as well as spit a noxious substance much like the Thorn Toad and Toxin Toads.

During the breeding season male Tetsucabra fight violently for females like African Bullfrogs. A successful male will then dig out a nursery for his offspring that he maintains diligently.

Inflatable frogs

Zamitrios: Arctic amphibians known for their striking appearance, massive maw, and rapid metamorphic lifecycle.

The primary species is found around the polar seaway and its surrounding environments, and deals with the temperatures through antifreeze compounds in the blood and gigantothermy. The species is aquatic, swimming with powerful webbed feet and a fluked tail after prey which they dispatch via shark-like jaws and teeth. But they need to be careful not to fall prey to other monsters such as the massive parave Ukanlos.

They drink seawater, and their specialized kidneys can filter out the salt. In self defense they can spray some of their water reserves along with bits of liquid nitrogen from groves along their hide. In the freezing temperatures of their habitat this instantly freezes over their body to form ice armor. If that fails they can suck in a bunch of air to inflate themselves and make themselves look bigger.

Zamtrios tadpoles are already born with forelimbs and have large jagged cranial horns. They target large animals and drill into their hides to eat them alive from the inside, and then rapidly metabolize their meals to grow into subadults. Subadults are very similar to juveniles but have proper hind limbs. This rapid growth is a defensive mechanism, as without parental care it is in a juvenile’s best interest to grow big quickly since in such harsh arctic environments any predator is willing to make a quick snack of them.

There exists a desert dwelling subspecies that, as a water retention adaptation, has lost the ability to create ice armor.

Tricktoad: A small member of the family that takes the inflatable abilities of Zamtrios to the next level. Lighter than air gases are retained from their digestive system and used to float. They then use various fins to (clumsily) propel themselves. In self defense they can secrete a substance that smells good to large predators before making a hasty getaway in hopes of eliminating a would-be predator.

Yama Tsukami: Traditionally put in the slight wastebasket taxon that is the elder dragon class, its placement here is controversial. Not much is known about the species.

Yama spend very long periods of time on the forest floor of the forests and jungles they call home, long enough that flora grows on their skin and adds a layer of camouflage. Occasionally they experience periods of activity where they then proceed to quite literally inhale plants and any animals not fast enough to escape its massive maw, which is equipped with massive human-like teeth perfect for processing woody material. Great Thunderbugs also live symbiotically within their mouths where they keep it mostly clean of debris, plaque, and cavities.

They accomplish flight via the same way as Tricktoads, but instead of using fins for propulsion they use gas and inhaled air that is vented from “gills” on their underside. So reliant are Yama on floating for movement that the muscles in their limbs have atrophied and their skeleton isn’t ossified outside of their jaws as a weight saving adaptation. If they ever find themselves grounded they are incapable of movement until able to re-inflate.

As the species is very poorly understood, their reproductive habits are a mystery. But Mezeporta hunters have reported a variation of the monster called Yama Kurai, although these are likely just very old Yamas.

Other notes

Gelidron: A recently discovered species of giant salamander native to the oilwell basin. They live their lives in the slow lane in groups, lazily foraging for various endemic crustaceans. To navigate rough terrain they are equipped with claws and gecko-like foot pads.

They’re able to gradually shift their color to be darker when in oilslits and their iridescent mucus further aids in this camouflage. If threatened they open their mouths as a threat display, but are otherwise easy and nutritious meals. They primarily rely on their explosive reproduction for defense.

Yes I know I wouldn’t have needed to make various workarounds for these guys if I just made them Temnospondyls instead of frogs but shhhh let me have some fun and talk about weird frogs and frog anatomy.

#monster hunter#monhun#monster hunter biology#monsterhunter#speculative biology#speculative evolution#speculative zoology#taxonomy#phylogenetics#phylogeny#cladistics#tetsucabra#amphibians#zamtrios#chatacabra#yama tsukami#paratoad

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

Heehee-hoohoo (stealthily reaches for my paintbrushes)

I love how color is one of the very important ways of identifying a mushroom, except these guys think it's cute to just

browns? grays? cream? blues? tan? reddish? Hell yeah! Trametes versicolor. (plus two other scientific names, because apparently mushroom phylogeny almost as bad of a dumpster fire as fish phylogeny)

75 notes

·

View notes