#i like to think they were and these sprite similarities allude to that

Text

Hey. Sprite analysis folks what the fuck does this mean

Somewhat inspired by this post

#ace attorney#pwaa#mia fey#iris hawthorne#iris fey#iris of hazakura temple#sprite analysis#mine#one of my biggest unanswered questions of aa is how much the twins interacted with mia before dl-6/leaving kurain with their father#like were they close. or was morgan's jealousy so strong that she stopped any of that dead in its tracks#i like to think they were and these sprite similarities allude to that#but then WHY. does mia not recognize dahlia in 3-4 it makes absolutely no sense#she absolutely would have been old enough to remember her. i get they probably didn't want to spoil dahlia being a fey but like#her recognizing mia first (made more obvious in the anime) already points to that. i feel like another vague line would have been sufficien#anyway i could go on about this for hours but. if anyone has more thoughts feel free to add#iris lovers PLEASE interact she is everything to me

56 notes

·

View notes

Note

If a season 2 was gonna happen I thought KP would have still been the main storyline especially if you look at how the show ended. With so many questions about porsche's family, his mysterious background and this new dynamic with them both being leaders.

But I'm no longer sure about that and this is because of the following reasons:

1. I remember MA were in this farmhouse? event (Barcode was there too) and Apo confirmed a s2 was happening, boc had to do some auditioning/logistics or something before starting (this is what I remember). But besides KPTS there was this new project him and Mile were working on and fans should look forward to it. Obviously, Apo is going to promote his next project but I also felt— in the way he said that and how exited he was—that Apo/MA had moved on from KPTS. I put it aside for sometime and forgot about it but now it makes sense even more with the 2nd reason appearing.

2. Sprite confirming she might be in s2. "Might" so there are chances she wouldn't be there. But how could Yok not be there when she is part of the inner circle of Porsche (the main character). The only reason is because Porsche and Kinn are no longer the leads so their inner circles aren't as important to the main storyline.

3. Mile saying that he will stay with boc for a year and then focus on his career in ent. + family business. The one year with boc is for the film with Apo. That year would not be enough to film both the film and a s2 + promoting them.

Obviously, I could also be wrong but those are my observations.

No, you're absolutely right, anon. I have no disagreements with any of this because you're speaking my thoughts. The only reason Sprite/Yok would be in a season 2 is if Porsche is there. He's the only one she has a connection to. She doesn't have a connection to any of these other characters. Maybe that Tem (?) guy who was drunk in her bar, but that's not enough for people to care because Tem was barely a character to begin with. His story and his subsequent connection to TimeTay is a consequence of the novel readers, like I'm always talking about. Neither of these characters nor their stories mean anything to people who haven't read the novels. That's just the truth of the matter. We don't care about them because we don't know them and the show didn't give us an opportunity to really get to know them either, so .. 🤷🏿♀️

That year that Mile mentioned would mostly be spent with him and Apo filming, marketing, and promoting that movie. You're right, anon. That's not enough time to do all of that in regards to that movie AND film a second season of KPTS. It's not enough time, because I don't even think they've finished filming the movie. With everything they've been doing lately, they haven't had time to complete whatever they need to complete in regards to the movie. They may be able to drop in for guest appearances every now and then but I doubt it would be like it was where they're essentially in every single episode of the season and that's just not a show I'm willing to watch. Sorry not sorry.

I think some people are more worried about MileApo separating than they are about anything else, so they're unwilling to pick up on what's being alluded to in these interviews. I doubt they're going to be separated any time soon but it can always happen, and I would advise people to get ready for that if/when it comes. Even Apo is changing his tune in a lot of different ways in terms of actually promoting himself and not just the "family", and that's been an interesting thing to witness in real time. The way he's been on social media lately seems very similar to how Mile has been this whole time, and that's telling. There's been a shift, anon. Something has changed and we can't know for certain if it has to do with them wanting to move on from this show/BOC but I wouldn't blame them if it did.

But this is all conjecture and I'm willing to be wrong. It's just my opinion, and people are welcomed to disagree.

1 note

·

View note

Note

do you have more thoughts on keyblade fighting that you need to put somewhere, because i have two hands ready to catch Should The Need Arise

anon: hey I heard you mention you’d analysed the combat styles in KH and what you said in the tags was already alluding to really neat stuff, but I for one would love to hear more of what you came up with!! so if you ever wanted to share any of your analysis then the floor is yours

aHAH, MY EXCUSE!!

Okay, so first some words on “standardized wielding styles”. These are styles shared by Terra, Aqua, Vanitas, Riku, and Xehanort and every other scala and daybreak kid. I will make the argument that the red style is the fanciest standard style, while the purple is seen often to make it easier on the little chibi sprites. BUT, I cannot discredit Eraqus, who uses the purple variant in bbs, nor can I discredit half of the Foretellers (Gula and Ava, at least, use this. Invi and Aced use the first type). So, two standard styles. For simplicity, let’s say one for primary offense, one for primary defense. The standard offensive style really wasn’t popular before Scala-era society.

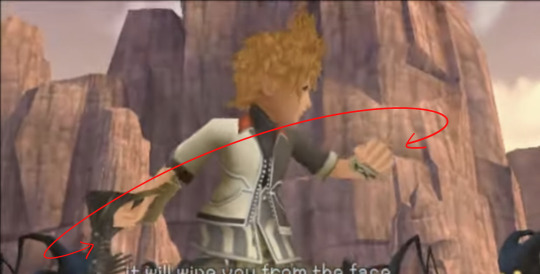

check this difference out, specifically between ava invi and gula:

then between eraqus, hermod, and xehanort, and eraqus and terra.

These two were likely popularized and standardized for education in Scala ad Caelum for their predominant lack of obvious weak spots.

After this, we have unique styles. Those include Sora Kairi and Xion’s (similar to standard defense, but more mobile at the expense of form — Kairi takes after Sora but less confident, she hasn’t been hit that heavily yet), Ven’s (backhand, heavy range and mobility), Roxas’ (modified for two keyblades, but takes after Sora), and Axel’s (taught himself, comfortable with chakrams).

So! Let’s go.

.

Standard (offensive)

All styles have sub-variations, of a sense. Different wielders can choose where their keyblade points, and how they hold it exactly, based on what makes them most comfortable. Terra and Aqua point theirs downward, while Vanitas and Riku hold theirs above their head. What is recognizeable to this style is a hand for the sword, and a hand for guarding/blocking/items/magic.

It’s incredibly efficient. With only one hand on the weapon, you not only free up a hand for other things, but increase your range of movement with said weapon. Test it out yourself! The keyblade hand is always your dominant hand, held behind you for increased power when attacking (since you lose a significant amount of it by choosing not to grip with both hands). This style also decreases the speed of the defense you have, but with that increased mobility and swing power, along with a hand free to brace against the keyblade (defense strength up!), it makes up for it. Many people who use this also have strong barrier spells — both a testament to their preference for coverage and an acknowledgement that any directional block will take a little longer and be weaker if they try it with one hand.

The pointy end, though. What difference does it actually make, the height it’s at?

I think it’s half a matter of attack style preference and half intention. Riku, Vanitas, and Xehanort stab quite a bit. Aqua and Terra slice more. Not that they don’t do both, but it’s the first instinct. Aqua and Terra are also likely taught to hold their keyblade neutrally, in a safe position, until someone starts attacking. It’s polite! Eraqus also holds his one-handed, neutrally, until he gets into position. Riku and Vanitas learned to fight assuming everyone was out to fight them. Invi and Aced may like this style because of range (i hc she’s blind and strikes very very quickly, and he’s already very powerful with just the one arm and wants better motion).

and on character specifics: Terra often switches to two-handed, to copy his dad and add extra power to his hits without always sacrificing the empty hand. Vanitas likely was forced to relearn how to fight, as instead of solely being trained to be better at withstanding, he was constantly being made to better his own attacks. The moves Xehanort uses would best be replicated in the same style. Vanitas is wild for holding the massive spiky x-blade like that.

Now, what‘s good on this style does not correlate to what’s bad in the other. The two standard styles simply have different ways of dealing with each con they create or taking advantage of each pro.

(Here’s an interesting side note — Gula uses standard defensive, but in this instance, swaps. One hand… likely to display confidence! Wrong move, but hey. He got cocky. He’s also doing it wrong, and swaps back to two-handed to take Aced’s attack.)

.

Standard (defensive)

The main detriment of this style is the lack of ease of long range movement. Hold a wrapping paper tube out in front of you with both hands, then run. It goes to the side, or tucks in to your stomach, right? Dodge. Your legs will get in the way unless you know where to move that sword. It requires, interestingly, a little more discipline. You’d think Aqua would like that, but no, she wants movement and practicality, and she loves magic, and remember that you must take a hand off this style to grab a potion. You’d think young Eraqus wouldn’t, but remember that he’s a fancy royal lad.

The main draw, though, is tankiness, readiness, and power. You don’t need to move as much if nothing dares hit you! Ava and Gula might be attracted to this style because they’re not as physically strong, but want protection in close-quarters fighting. Using this style when your muscles aren’t as big but you still want to Hit Things Good, or when you want to be a boy you can’t knock over with a pail of water (horse stance rules), is probably solid advice.

Traditionally, this is a lot less like fencing, and a lot more like a samurai sword or kendo. Your blade is held in front of you, giving you very easy access to blocks and frontal attack/defense. In losing some twirly spinniness, you gain power and minimize your opponent’s ability to parry and block.

you gotta dodge master Eraqus so mcuh

All styles will swap between one and two hands for different moves. Eraqus, notably, swaps to a stance very similar to Xehanort when channeling a metric ton of magic.

Both of these styles require a degree of upper body/core strength, as does all swordfighting. I would be interested to see someone whose keyblade style relies on leg strength.

.

Sora, Xion, and Kairi

please look at the difference between the foretellers’ or eraqus’ two-handed grip and Sora’s. Do this with your shoulders and a top-heavy object.

They’re both in a hard stance, but hon. What are you, a gremlin? Anyways, a traditionally taught master would have… better form, even if it’s harder to learn at first. It’s habitual. Sora nearly crouches, and holds his keyblade back-pointed with two hands, which makes it easier for him to dodge roll, push off his feet quickly, and pull off those spinning combos he loves. It‘s really gonna hurt his muscles, in the future, though, since he’s doing a squat for like…. hours. Pulling on those shoulderblades and neck. Xion, too. Replicas had better have correct muscle dynamics. Kairi is brand new, so… maybe Aqua can teach her how to hold a sword so it doesnt hurt you.

Okay, now look at the grip itself. Held in front versus held to the side-back. They’re really attempting to combine both standard styles subconsciously, giving themselves more attack power while really wanting to keep that hard defensive parry, wanting to prevent all attacks to the front while also wanting mobility. It’s working for them really well, they fight like an anime character, and manage to get the best of both, with a minor sacrifice of length range that they don’t care about. We’re flexible and full of magic, baby! Holding the blade like this makes it pretty easy to let go with one hand without sacrificing that crouched defense position.

Now, Sora, specifically, is very adaptive. He’s had two keyblades, claws, guns, yo-yos, and a giant shield, to name a couple. He retains a bit of that alert crouch no matter where he goes, but Sora knows how he wants to attack and how to balance that with the most effective way to use his current weapon. He’s a smart kid! Sora has the most ridiculous shotlocks, which are also probably due to not always wanting to go standard for it. He also prefers to keep his focus on the enemy, which is evident in his reprisals and lack of very many effective “escape” moves.

Xion is very similar to Sora, but she does have some moves that are all movement. She switches to one handed for strikes a lot — using two for defending, one for smacking. In her data battle I’d swear some of those heavy hits are claymore-like. But anyways, since we’re magic, Xion cares not for the laws of exhaustion, and will ping about as a ball of light everywhere. Short range? Up in your business. Mid-range? In your business with one hand. Long range? Throws a boomerang. Hit her? No you dont. Ball of light. She’s above you and wants to bash your head in. (Vanitas also does this! A lot. It’s an easy way to catch someone off-guard. I’ll argue that the soras are very tough and strong, but not tanky. they want to avoid being hit a lot)

Another interesting note about Kairi. I say “unconfident” not because she doesn’t hit hard, but because her stance is also often tilted back, ready to dodge. It’s two handed, but almost all her moves are one. She does love spinning and throwing the thing! It looks like she’s been taking notes from the wielders she knows. It would be easy to teach her a standard style, I think. See here, she lets go on the strike, and by trying to do both, actually ends up with an advantage (being confusing) and disadvantage (losing both the power of two handed and versatility of one handed).

A counter to Sora and Xion is difficult to pin down. Time? Probably. Lack of heating pads. Something that takes all their attention is about the only way to get a sneak attack in, and then you have to hit hard. A counter to Kairi would be anyone who can knock her off balance. She needs a sturdier stance.

.

Roxas

Roxas is interesting. He takes after Sora for the one blade. Wielding two, however, nets him a totally different way of fighting. Roxas’ clavicle muscles n… deltoids and stuff must be Ironclad. Also, two handed means you are very fast and sharp all the time. He has the advantage of standard defense (horse stance), and the advantage of offense (range of one sword, but twice).

Roxas generally attacks in two ways — simultaneous hits, and follow-up hits. Either he hits with both at once, or hits hard with the first one, and adds the second one as a bonus smack. He can attack by hitting in opposite directions with the two, like a drum, but that will be a little awkward and leave him prone to being tangled. That established, the follow-up hit method means he spins a bunch. As do we all.

Roxas gets a little complicated because we are not in the real world. We have magic and turning into light and physics that let you become a circular saw. So, typically, disadvantages would include: being unable to let go of a weapon to grab something or use an item, having just a very big silhouette to attack on, having difficulty with close-range attacks because Oathkeeper and Oblivion are kinda long, and convenience. Roxas gets to dodge #1 (keyblades can be unsummoned) and #4 (keyblades can be unsummoned). Speaking of dodging, he also gets to skirt the difficulty of dodging and rolling with two swords because he turns into a beam of light. But he can’t dodge how difficult it is to use two swords effectively — he needs to concentrate on fighting, and nothing else, or he risks messing up. He has to be very, very coordinated, and undistracted. Luckily he’s pretty good at making his opponents shut up, most of the time. Blocking is another thing — theoretically his blocks could be strong, but Roxas has no real brace: crossing your blades and taking a hefty stab might smack one of them back into your face. He mostly uses reversals and dodges, because of this.

The takeaway to this is Roxas is built for speed and power, and he is very strong. He’s a mid- to far- range fighter who if you’re not careful can snap you in half if you’re too close (be SO careful of that cross blade scissor).

A perfect counter to Roxas would be a tank that can grapple, and also be very distracting. If you can take hits, be talkative, and get close enough to stop his blades, you have a chance.

.

Ventus

This is a bizarre choice, my guy, but I get it.

Backhanded weapons are very impractical for a lot of... attacking, mainly in mid-range combat, and Ven likes to either fight very close or throw the keyblade like a boomerang (and hey, backhand gives it a good whip for throwing). His attacks aren’t meant to one hit KO, but they do come with a bit of power to them, especially on the backslash. Like holding a knife for gouging. It’s for very close defense — pretty good when Wayward Wind and Missing Ache have hooks.

Backhand also, while retaining that empty hand for potions and guarding, gives you an extreme coverage boost. By which I mean Ven’s sword hand now has a nearly 270 degree sweep of “I see you, don’t touch me”, very quickly, based on just flicking his wrist. It sacrifices a ton of strength/sturdiness, but you don’t need that if you’re dodging. You also don’t really need to block, which is slower, but relatively sturdy when Ven does it, as he blocks with mostly the chunky hilt between crossed arms. He sacrifices (again) a bit of strength for coverage — an attack would hurt his arms, not his chest, if he were hit head-on.

His attacks often have him flip the blade around in his hand, too. Quick swaps between standard moves and backhand ones. Basically, Ventus is built for moving, protecting himself, and quick attacks that wear down the enemy, not outclass it. Likely because he’s good at fighting, but everyone he’s fought hits harder than he can! It doesn’t matter how he holds it, getting hit will hurt. So he just. Doesn’t. He’s not a buff little guy — but he is a persistent one. Ven very likely made this up on his own, in Daybreak, and it was too hard to fix his whole style, but it was enough to correct most of his form so he doesn’t hurt himself too much. He is going to have to really stretch that shoulder and wrist (maybe get a brace), though. At least his neck is ok. … not sure about his knees tho dang boy that crouch

A perfect counter to Ven would be someone big and fast, who hits hard mid-range. He’s already been sparring with Terra, though, so when in doubt, try scruffing him?

.

Axel

Theres not a ton to say about him — he‘s not a swordfighter. He uses his keyblade like it’s a frisbee. Because that’s what he’s used to! His neutral is behind his back on his shoulder, which is terrible for readiness, but okay for chucking the thing. It’s good it has a sort of… ripstik like… boomerang quality.

Axel’s fighting style is completely made up, like most of the self-taught wielders’. His strengths lie in some of the benefits of standard offensive style (one-handed), and some of the same coverage stuff as Ven, having a cocked wrist most of the time so no one can sneak up around him without risking getting whacked very quickly, and having an interesting range due to the pointy end being basically on a spinny swivel wherever his hand moves. He’s not going to be good at close-range and he knows it — his attacks are mostly distance. And the guy has ZERO defense, combined with zero coverage when idle, so it’s for the better.

Distance-wise, though, he rocks. Treating the blade like it’s a flaming throwing weapon means his idle is actually great for sudden flick-tossing and attention-guiding for sneakier attacks, and his stance itself (…nonexistent) serves a different purpose: bait. Basically a big "come hit me". Fun, when you have a lot of fire magic and two friends who are beasts and love to take advantage of a distracted enemy — distance on the blade, proximity on the burning.

A perfect counter to Axel would be someone pinging around very close <—> very far and circling him incessantly. Like, data Xion could wreck him, as he has to wait for the boomerang to come back -- he no longer has two spinny wheels. Also someone with water magic.

.

SO! In conclusion! Having a teacher who teaches you correct sword usage rather than instinct may detract from overspecific styles that benefit you most but leave weak spots, but your muscles and your oversights will thank you. Everyone is glad we have the power of the Mouse and anime on our side.

Keep in mind again that I have done cursory research, and have had minimal actual sword instruction, I am not an expert and this is all for fun anyways :]

#I ran out of images which is homophobic#KH#ask#mojimallow#THANKS MOJI#If you’re wondering what the counter would be to Terra and Aqua; in terms of counters there are no counters#not style-wise anyways. That’s why they’re standard.#Terra can’t react very fast and Aqua needs more mp but that’s individual#and we are mostly talking BASE COMBAT here#of course lingering will can use keyblade transformations and there’s magic strategies — but that would make this post… much longer#brrrrrrr#kh analysis#kh meta#thanks to the handful of other people who asked me to expand on the same thing <3<3<3#REALLY wanted to include one of Invi blocking — just go watch invi and aced fight for two standard offense#it Shows off their strengths and weaknesses#… no living adults do the two handed grip. Watch Sora and Xion’s data battle for an approximation I guess??#you. Hey you. Look in the notes rn#metazone

211 notes

·

View notes

Text

i played deltarune chapter 2 right when it was released, and I was finishing omori at the same time, and now that i think about it there’s a lot of parallels between sunny/basil/mari and kris/noelle/dess, respectively. spoilers for both deltarune and omori ahead

stay with me here, ok?

let me just establish some things; I believe the theory that dess disappeared in the bunker, and also that she is the one saying the unused dialogue. whether that means she's dead or trapped in a dark world there's no way to be sure, but nonetheless she was never heard from again. I don't think they ever recovered a body. I think the events that led to her disappearance happened on the night that the four of them explored the woods. since we can see noelle's child sprite during the spelling of the word december puzzle, she was probably that small and that much younger when it happened. If they're high school age now, like around 14-16, I'd put the events of dess's disappearance at around 4-5 years ago. that would explain why the adults of the hometown don't really mention it but it's still a touchy subject for kris, noelle, and susie (her dialogue when you check the angel doll). I also believe that "Don't Forget" is dess's singing, and her motif.

how does omori relate to this?

- the 'don't forget' motif is present in a majority of the tracks in Deltarune. It seems pretty important, yet we don't know the true meaning of it just yet. in Omori, the Final Duet motif was present in a majority of the tracks before you actually hear the full duet at the end of the game, where it is revealed to be the song Sunny practiced with Mari and was the piece they were going to perform on the day she died. I think the big reveal is going to be that Don't Forget is Dess's song, and that kris would play the piano accompaniment for her. The ending could allude to Omori in that for kris to be able to heal from this traumatic event, they need to play through Their duet with Dess.

- This is also why I put Sunny with Kris instead of Noelle, despite dess and noelle being the ones who are actually related. I think Basil and/or kel matches best with noelle because basil and sunny were the closest to each other before mari died, and noelle was most likely kris's closest friend in hometown before dess died. Different from basil however, is that noelle actively invites you to hang out with her, and she herself says they've grown apart and is glad to be adventuring with them again, which is more similar to kel's role in omori. Noelle and kris definitely have a different dynamic than either character and sunny as I don't think they suffered the exact same way sunny and his friends have, but they definitely still have a shared trauma around Dess. I think they both know the truth of what happened to her and why she could never be found; similarly to how basil and sunny were the only people who knew what really happened to mari.

I'm uh. not really sure how asriel fits into this. I don't know if he also knows the truth of what happened to dess, or how it affected him, and we probably won't find that out (if at all) until he comes back in the last chapter.

tl;dr my strongest point from all of this is that Kris parallels sunny, they played the piano arrangement for Don't Forget and dess, who parallels mari, sang the song, and they were going to perform it before dess mysteriously disappeared and it haunts kris now, hearing the motif from the song everywhere they go.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lore Episode 32: Tampered (Transcript) - 18th April, 2016

tw: none

Disclaimer: This transcript is entirely non-profit and fan-made. All credit for this content goes to Aaron Mahnke, creator of Lore podcast. It is by a fan, for fans, and meant to make the content of the podcast more accessible to all. Also, there may be mistakes, despite rigorous re-reading on my part. Feel free to point them out, but please be nice!

I grew up watching a television show called MacGyver. If you’ve never had that chance to watch this icon of the 80s, do yourself a favour and give it a try. Sure, the clothes are outdated and the hair… oh my gosh, the hair. But aside from all the bits that didn’t age well, MacMullet and his trusty pocket knife managed to capture my imagination forever. Part of it was the adventure, part of it was the character of the man himself – I mean, the guy was essentially a spy who hated guns, played hockey and lived on a houseboat. But hovering above all those elements was the true core of the show. This man could make anything if his life depended on it. As humans, we have this innate drive inside ourselves to make things. This is how we managed to create things like the wheel, or stone tools and weapons. Our tendency towards technology pulled our ancient ancestors out of the Stone Age and into a more civilised world. Maybe for some of us, MacGyver represented what we wanted to achieve: complete mastery of our own world. But life is rarely that simple, and however hard we try to get our minds and hands around this world we want to rule, some things just slip through the cracks. Accidents happen. Ideas and concepts still allude our limited minds. We’re human, after all, not gods. So, when things go wrong, when our plans fall apart or our expectations fail to be met, we have this sense of pride that often refuses to admit defeat. So, we blame others, and when that doesn’t work, we look elsewhere for answers, and no realm holds more explanation for the unexplainable than folklore. 400 years ago, when women refused to follow the rules of society, they were labelled a witch. When Irish children failed to thrive it was because, of course, because they were a changeling. We’re good at excuses. So, when our ancestors found something broken or out of place, there was a very simple explanation – someone, or something, had tampered with it. I’m Aaron Mahnke, and this is Lore.

The idea of meddlesome creatures isn’t new to us. All around the world, we can find centuries-old folklore that speaks of creatures with a habit of getting in the way and making life difficult for humans. It’s an idea that seems to transcend borders and background, language and time. Some would say that it’s far too coincidental for all these stories of mischief-causing creatures to emerge in places separated by thousands of miles and vast oceans. The púca of Ireland and the ebu gogo of Indonesia are great examples of this – legends that seem to have no reason for their eerie similarities. Both legends speak of small, humanoid creatures that steal food and children, both recommend not making them angry, and both describe their creatures as intrusive pranksters. To many, the evidence is just too indisputable to ignore. Others would say it’s not coincidence at all, merely a product of human nature. We want to believe there’s something out there causing the problems we experience every day. So, of course, nearly every culture in the world has invented a scapegoat. This scapegoat would have to be small to avoid discovery, and they need respect because we’re afraid of what they can do. To a cultural anthropologist, it’s nothing more than logical evolution. Many European folktales include this universal archetype in the form of nature spirits, and much of it can be traced back to the idea of the daemon.

It’s an old word and concept, coming to us from the Greeks. In essence, a daemon is an otherworldly spirit that causes trouble. The root word, daomai, literally means to cut or divide. In many ways, it’s an ancient version of an excuse. If your horse was spooked while you were out for a ride, you’d probably blame it on a daemon. Ancient Minoans believed in them, and in the day of the Greek poet Homer, people would blame their illnesses on them. The daemon, in many ways, was fate. If it happened to you, there was a reason, and it was probably one of these little things that caused it. But over time, the daemon took on more and more names. Arab folklore has the djinn, Romans spoke of a personal companion known as the genius, in Japan, they tell tales of the kami, and Germanic cultures mention fylgja. The stories and names might be unique to each culture, but the core of them all is the same. There’s something interfering with humanity, and we don’t like it.

For the majority of the English-speaking world, the most common creature of this type in folklore, hands down, is the goblin. It’s not an ancient word, most likely originating from the middle ages, but it’s the one that’s front and centre in most of our minds, and from the start it’s been a creature associated with bad behaviour. A legend from the 10th century tells of how the first Catholic bishop of Évreux in France faced a daemon known to the locals there as Gobelinus. Why that name, though, is hard to trace. The best theory goes something like this: there’s a Greek myth about a creature named kobalos, who loved to trick and frighten people. That story influenced other cultures across Europe prior to Christianity’s spread, creating the notion of the kobold in ancient Germany. That word was most likely to root of the word goblin. Kobold, gobold, gobolin – you can practically hear it evolve. The root word of kobold is kobe, which literally means “beneath the earth”, or “cavity in a rock”. We get the English word “cove” from the same root, and so naturally kobolds and their English counterparts, the goblins, are said to live in caves underground, and if that reminds you of dwarves from fantasy literature, you’re closer than you think. The physical appearance of goblins in folklore vary greatly, but the common description is that they are dwarf-like creatures. They cause trouble, are known to steal, and they have tendency to break things and make life difficult. Because of this, people in Europe would put carvings of goblins in their homes to ward off the real thing. In fact, here’s something really crazy. Medieval door-knockers were often carved to resemble the faces of daemons or goblins, and it’s most likely purely coincidental, but in Welsh folklore, goblins are called coblyn, or more commonly, knockers. My point is this: for thousands of years, people have suspected that all of their misfortune could be blamed on small, meddlesome creatures. They feared them, told stories about them, and tried their best to protect their homes from them. But for all that time, they seemed like nothing more than story. In the early 20th century, though, people started to report actual sightings, and not just anyone. These sightings were documented by trained, respected military heroes. Pilots.

When the Wright brothers took their first controlled flight in December of 1903, it seemed like a revelation. It’s hard to imagine it today, but there was a time when flight wasn’t assumed as a method of travel. So, when Wilbur spent three full seconds in the air that day, he and his brother, Orville, did something else: they changed the way we think about our world. And however long it took humans to create and perfect the art of controllable, mechanical flight, once the cat was out of the bag, it bolted into the future without ever looking back. Within just nine years, someone had managed to mount a machine gun onto one of these primitive aeroplanes. Because of that, when the First World War broke out just two years later, military combat had a new element. Of course, guns weren’t the only weapon a plane could utilise, though. The very first aeroplane brought down in combat was an Austrian plane, which was literally rammed by a Russian pilot. Both pilots died after the wreckage plummeted to the ground below. It wasn’t the most efficient method of air combat, but it was a start. Clearly, we’ve spent the many decades since getting very, very good at it. Unfortunately, though, there have been more reasons for combat disasters than machine gun bullets and suicidal pilots, and one of the most unique and mysterious of those causes first appeared in British newspapers. In an article from the early 1900s, it was said that, and I quote, “the newly constituted royal air force in 1918 appears to have detected the existence of a hoard of mysterious and malicious sprites, whose sole purpose in life was to bring about as many as possible of the inexplicable mishaps which, in those days as now, trouble an airman’s life.” The description didn’t feature a name, but that was soon to follow. Some experts think that we can find roots of it in the old English word gremian, which means “to vex” or “to annoy”. It fits the behaviour of the creatures to the letter, and because of that they have been known from the beginning as gremlins.

Now, before we move forward, it might be helpful to take care of your memories of the 1984 classic film by the same name. I grew up in the 80s, and Gremlins was a fantastic bit of eye candy for my young, horror-loving mind, but the truth of the legend has little resemblance to the version that you and I witnessed on the big screen. The gremlins of folklore, at least the stories that came out of the early 20th century that is, describe the ancient stereotypical daemon, but with a twist. Yes, they were said to be small, ranging anywhere from six inches to three feet in height, and yes, they could appear and disappear at will, causing mischief and trouble wherever they went. But in addition, these modern versions of the legendary goblin seem to possess a supernatural grasp of human technology. In 1923, a British pilot was flying over open water when his engine stalled. He miraculously survived the crash into the sea and was rescued shortly after that. When he was safely aboard the rescue vessel, the pilot was quick to explain what had happened. Tiny creatures, he claimed, had appeared on the plane. Whether they appeared out of nowhere or smuggled themselves aboard prior to take-off, the pilot wasn’t sure. However they got there, he said that they proceeded to tamper with the plane’s engine and flight controls, and without power or control, he was left to drop helplessly into the sea.

These reports were infrequent in the 1920s, but as the world moved into the Second World War and the number of planes in the sky began to grow exponentially, more and more stories seemed to follow – small, troublesome creatures who had an almost supernatural ability to hold on to moving aircraft, and while they were there, to do damage and to cause accidents. In some cases, they were even cited inside planes, among the crew and cargo. Stories, as we’ve seen so many times before, have a tendency to spread like disease. Oftentimes, that’s because of fear, but sometimes it’s because of truth, and the trouble is in figuring out where to draw that line, and that line kept moving as the sightings were reported outside the British ranks. Pilots on the German side also reported seeing creatures during flights, as did some in India, Malta and the Middle East. Some might chalk these stories up to hallucinations, or a bit of pre-flight drinking. There are certainly a lot of stories of World War Two pilots climbing into the cockpit after a night of romancing the bottle – and who can blame them? In many cases, these pilots were going to their death, with a 20% chance of never coming back from a mission alive. But there are far too many reports to blame it all on drunkenness or delirium. Something unusual was happening to planes all throughout the Second World War, and with folklore as a lens, some of the reports are downright eerie. In 2014, a 92-year-old World War Two veteran from Jonesborough, Arkansas came forward to tell a story he had kept to himself for seven decades. He’d been a B-17 pilot during the war, one of the legendary flying fortresses that helped allied air forces carry out successful missions over Nazi territory, and it was on one of those missions that this man experienced something that, until recently, he had kept to himself. The pilot, who chose to identify himself with the initials L.W., spoke of how he was a 22-year-old flight commander on the B-17, when something very unusual happened on a combat mission in 1944. He described how, as he brought the aircraft to a higher altitude, the plane began to make strange noises. That wasn’t completely unusual, as the B-17 is an absolutely enormous plane and sometimes turbulence can rattle the structure, but he checked his instrument panel out of habit. According to his story, the instruments seemed broken and confused.

Looking for an answer to the mystery, he glanced out the right-side window, and then froze. There, outside the glass of the cockpit window, was the face of a small creature. The pilot described it as about three feet tall with red eyes and sharp teeth. The ears, he said, were almost owl-like, and its skin was grey and hairless. He looked back toward the front and noticed a second creature, this one moving along the nose of the aircraft. He said it was dancing and hammering away at the metal body of the plane. He immediately assumed he was hallucinating. I can picture him rubbing his eyes and blinking repeatedly like some old Loony Toons film. But according to him, he was as sharp and alert as ever. Whatever it was that he witnessed outside the body of the plane, he said that he managed to shake them off with a bit of “fancy flying”, and that’s his term, not mine. But while the creatures themselves might have vanished, the memory of them would haunt him for the rest of his life. He told only one person afterwards, a gunner on another B-17, but rather than laugh at him his friend acknowledged that he, too, had seen similar creatures on a flight just the day before.

Years prior, in the summer of 1939, an earlier encounter was reported, this time in the Pacific. According to the account, a transport plane took off from the airbase in San Diego in the middle of the afternoon and headed toward Hawaii. Onboard were 13 marines, some of whom were crew of the plane and others were passengers – it was a transport, after all. About halfway through the flight, whilst still over the vast expanse of the blue Pacific, the transport issued a distress signal. After that, the signal stopped, as did all other forms of communication. It was as if the plane had simply gone silent and then vanished, which made it all the more surprising when it reappeared later, outside the San Diego airfield and prepared for landing. But the landing didn’t seem right. The plane came in too fast, it bounced on the runway in rough, haphazard ways, and then finally came to a dramatic emergency stop. Crew on the runway immediately understood why, too – the exterior of the aircraft was extensively damaged, some said it looked like bombs had ripped apart the metal skin of the transport. It was a miracle, they said, that the thing even landed at all. When no one exited the plane to greet them, they opened it up themselves and stepped inside, only to be met with a scene of horror and chaos.

Inside, they discovered the bodies of 12 of the 13 passengers and crew. Each seemed to have died from the same types of wounds, large, vicious cuts and injuries that almost seemed to have originated from a wild animal. Added to that, the interior of the transport smelled horribly of sulphur and the acrid odour of blood. To complicate matters, empty shell casings were found scattered about the interior of the cockpit. The pistols responsible, belonging to the pilot and co-pilot, were found on the floor near their feet, completely spent. 12 men were found, but there was a thirteenth. The co-pilot had managed to stay conscious despite his extensive injuries, just long enough to land the transport at the base. He was alive but unresponsive when they found him, and quickly removed him for emergency medical care. Sadly, the man died a short while later. He never had the chance to report what happened.

Stories of the gremlins have stuck around in the decades since, but they live mostly in the past. Today they are mentioned more like a personified Murphy’s Law, muttered as a humorous superstition by modern pilots. I get the feeling that the persistence of the folklore is due more to its place as a cultural habit than anything else. We can ponder why, I suppose. Why would sightings stop after World War II? Some think it’s because of advancements in aeroplane technology: stronger structures, faster flight speeds, and higher altitudes. The assumption is that, sure, gremlins could hold on to our planes, but maybe we’ve gotten so fast that even that’s become impossible for them. The other answer could just be that the world has left those childhood tales of little creatures behind. We’ve moved beyond belief now. We’ve outgrown it. We know a lot more than we used to, after all, and to our thoroughly modern minds these stories of gremlins sound like just so much fantasy. Whatever reason you subscribe to, it’s important to remember that many people have believed with all their being that gremlins are real, factual creatures, people we would respect and believe.

In 1927, a pilot was over the Atlantic in a plane that, by today’s standards, would be considered primitive. He was alone, and he had been in the air for a very long time but was startled to discover that there were creatures in the cockpit with him. He described them as small, vaporous beings with a strange, otherworldly appearance. The pilot claimed that these creatures spoke to him and kept him alert in a moment when he was overly tired and passed the edge of exhaustion. They helped with the navigation for his journey and even adjusted some of his equipment. This was a rare account of gremlins who were benevolent rather than meddlesome or hostile. Even still, this pilot was so worried about what the public might think of his experience that he kept the details to himself for over 25 years. In 1953, this pilot included the experience in a memoir of his flight. It was a historic journey, after all, and recording it properly required honesty and transparency. The book, you see, was called The Spirit of St. Louis, and the man was more than just a pilot. He was a military officer, an explore, an inventor, and on top of all of that he was also a national hero because of his successful flight from New York to Paris – the first man to do so, in fact. This man, of course, was Charles Lindbergh.

[Closing Statements]

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

What's the appeal of Komahina (Yes, I know) since you said you enjoy answering shippy asks?

everything. its all the appeal of komahina. i’m love komahina. its top tier.

Okay real talk but the biggest Advantage™ to komahina is that there’s like so much to work with in canon. we have a whole game’s worth of content. And because of having so much shit to work with, there’s a lot to talk about! under the cut!

So the draw to end all draws is obviously that Komaeda is canonically gay, and specifically, gay for Hinata. That cop out confession is a work of art. It really is. The man literally says “I love--the hope sleeping within you, from the bottom of my heart” as if the last second subject switch is gonna do anything to disguise how gay it was. You used aishiteru Komaeda. We all know.

But you don’t even just need that free time event to confirm Komaeda’s Gay Feelings™, contrary to the belief of fools, Komaeda even alludes to it in chapter four. Sure he’s also busy being a total dick, but even then he can’t stop himself from commenting on how he’s still attached to Hinata, and that it’s making him emotional. The fact that Hinata, the man he loves, is the epitome of all the things he’s decided he’s supposed to hate, is what’s killing him inside, and you can argue its why he’s so vicious to Hinata in particular. it’s not something that Hinata deserves, of course, but its a side-effect of his perceived betrayal.

SPEAKING OF PERCEIVED BETRAYALS, let’s talk about chapter 1! So you’ll notice that I haven’t really talked about Hinata’s feelings towards Komaeda yet, and that’s because chapter 1 is what royally fucks those to high hell. Before the trial, Hinata really likes Komaeda. He enjoys spending time with him, and is happy to investigate with him. He considers Komaeda reliable, and that first free time event has him call Komaeda’s smile soothing, similar to how Naegi talked about Maizono’s. And we all know how Naegi felt about her. He doesn’t really think he knows Komaeda all that well, and Hinata is somewhat distrusting but not to an unhealthy degree, but despite all that, he still likes Komaeda. More than he’s probably aware of (hi Hinata I see you wrote down word for word Komaeda’s confession in your report card you wanna elaborate on that decision or--)

But that’s why trial fucks everything up so badly. Komaeda turned out to not be the person he thought. In that confrontation in trial, he’s incredibly distraught about having to do this despite only having known him for a few days. I think he even uses that sprite where he’s got tears in his eyes he’s that fucked up about it. He’s taken that perceived betrayal very personally.

I wanna make something clear though: Komaeda did betray the group but not to the extent Hinata takes it. Komaeda never really hides his issues or his true nature from people. His self deprecating nature is clearly visible and he does seem weirdly focused on hope a few times. Komaeda absolutely betrayed the group by kickstarting the killing game, however, he did not sell himself as anything other than himself, something Hinata firmly believes he did. It’s not that Komaeda ever behaved like a different person, it’s that they were unable to realize how deep his issues and complexes went until he acted on them. But because Komaeda is always personable and friendly, if not somewhat a nihilist, they didn’t realize what was wrong.

But despite that...Hinata’s still weirdly drawn to him. Despite wanting to hate Komaeda and feeling extraordinarily hurt by his betrayal...he still doesn’t quite let that go. Sure he’s pretty cold to Komaeda sometimes, but he still checks in on his despair fever. he still talks to him and tries to understand what makes him tick, even if he seems very unhappy about it. Hinata’s understanding of Komaeda in chapter 5 comes from this. In that final free time event, he’s even willing to forgive him before Komaeda backpedals hardcore. I think that’s proof enough that Hinata cannot hate Komaeda, and moreover deep down, that he doesn’t want to either.

But all that just kinda reeks of “tragically fucked up huh I doubt that would ever work out” but oh no you silly little potato chip. No it’ll be fine because sdr2 gave us the glorious virtual reality, maybe one day they’ll all wake up. And that’s the key place where things can get better. After canon, where they have all the time in the world to recover.

Chapter 6 tells Hinata a lot of things, but most importantly, he’s not better than Komaeda. They all fucked shit up. They were all fucked up and damaged emotionally; Komaeda just broke catastrophically before they did. They all need to recover and go past their issues; Komaeda is not exempt from that. And I think this key bit of information would help, at least in part, Hinata get past that perceived betrayal. Plus time and actually talking to Komaeda would do that too.

So what would either of them get out of a relationship? To me, that’s the most important thing about a ship to me: how either of them grows and become better, happier people. I think a lot that Hinata gets from it comes from helping Komaeda, and in doing so, he learns to understand more about himself. They both have similar complexes about talent, and feeling worthless in relation to it, and in helping Komaeda come to terms with that, among various other things, I think Hinata would come to terms with it himself, and be more confident.

They have a surprising amount in common with their lack of self-esteem and complexes around that. I also think Komaeda, in general, is encouraging, and if Hinata finds him soothing, it’ll help Hinata’s anxiety mellow out over time. Komaeda’s very good about taking things in stride which is something Hinata definitely needs in his life to help him.

And Komaeda? Boy. Well okay, Komaeda needs like a lot of actual therapy just. Just all the time. Hinata can’t really help much with that just support him. (To be clear Hinata also needs a therapist I just think talking to Komaeda will help him figure out what he needs to say to his therapist). But Komaeda desperately needs two things. The first is Komaeda really only feels like he can connect with someone he feels is the same level as him, which he definitely feels about Hinata. He has a line about them both being “bystanders to the other shsls.”

But moreover, Komaeda needs someone stable. Someone that can prove his life is not ruled over by a luck cycle. Komaeda’s luck is real, but it’s not the cycle he thinks it is. That’s just a coping mechanism he uses to cope with the immense tragedy in his life, because his “good luck” does not balance out his bad luck. Komaeda’s luck just tends to guarantee his success the more likely he is to fail. So he survives the plane crash, even though it should have killed him. So he gets the winning lotto ticket, even though the lottery is a scam designed to take your money. So he gets into hope’s peak, even though every other high school student his age was eligible for that slot. That’s how his luck works.

But his life is so tragic he has to assume its a good and bad cycle. He believes that anything good that happens has to cause something terrible, and vice versa, and its the basis of his worldview, but what he needs, is someone to stick around by him and prove him wrong. For someone to try to understand him, and not disappear on him. He needs a constant, and Hinata, who tries to understand him and is similar to him, is that constant. And I think by having that constant he’ll be able to let go of such a harmful worldview and move on into a happier place in his life.

Anyway tl;dr Komahina is good because it’s complex and mutually beneficial thank you good night!

222 notes

·

View notes

Text

Analysing Title Sequences

1. The Night Manager

Each shot transitioned into one another using Graphic Matches, which was really nice and helped the title sequence really flow better. They were very creative and also matched perfectly - especially with the telephone switching to the gun and the boats to the bubbles. All the shots blended really nicely into one another and seemed very sophisticated. The colour scheme was mostly cold, suggesting the serious tone to the sequence- also with little flashes of red to indicate possible violence in the TV series. The contrast between the luxurious expensive things and the weapons as well was aesthetically pleasing and also suggests the plot of the show without revealing too much. the music used was also very nice as the violins suggested a very upper class and serious motif, alluding to the genre of the series. The titles were also quite minimalist but easily stood out from the rest of the scene. They were written in a sans serif font that also hinted at the chosen sub-genre. In my opinion, this title sequence gives off a James Bond or posh spy movie vibe - which is also evident with the imagery of the martini.

2. Deadpool

I loved how the whole sequence is one continuous shot of a frozen scene- it’s a very creative choice and gives the audience a very detailed and intricate view to the scene - allowing us to see all the Easter eggs such as the Ryan Reynolds magazine and the green lantern card. It also really sets the tone of the movie due to the nature of the things happening: such as Deadpool giving the man a wedgie - which hints at the comedic nature of the film. I also really like the contrast between the serious fight scene and action motif (with the fire, dark colours and bullets) and then having the ‘angel of the morning’ music along with occasional hello kitty merchandise, which I think is both so out of place but also perfect at establishing the action/ridiculous comedy tone of the film. I also really love the fake credits sequence since it also indicates to the humour of the film. The font is very iconic, blocky and stands out well, as well as tracking nicely with the background, making it look like part of the scene. Overall, this is one of my favourite opening credits sequences of all time, it perfectly establishes the genre and contains many very unique aspects never seen before, it truly feels like a breath of fresh air.

I also like how you first see Deadpool during the chorus when the singer says ‘Angel of the morning’ as if he’s some kind of Angelic being.

3. Wonder Woman

This title sequence takes place during the end credits of the film and is very stylised - it doesn’t contain actual footage but is instead filled with concept art and silhouettes. It tells the story of the film. It is a sequence with very intense music in a similar style to the rest of the movie, and the entire thing is colourised with blue red and gold- the colours that are representative of Wonder Woman herself. The colour gold is very prominent and often seen with a glowing effect, as is the theme of fire; both of which are featured a lot the first part of the sequence. These themes are reflective of the main antagonist, as well as Diana’s golden truth Lasso. The background is mostly dark which makes the abstract imagery and shiny golden credits text really stand out and catch your eye. As the sequence progresses, the music is played in a major as the green and blue concept art for the island of Themyscria is shown - contrasting to the reds, blues, and fiery smoke effects which are used in most other parts (to indicate the war that takes place in the film). I also really like how Diana’s silhouettes are used in the credits sequence - it creates a 2D impression but then is also paired with 3D elements like the bullets hitting her shield - there’s different levels of animation in the sequence which I really like. I also like the appearance of the logo itself, how it starts off blurry and slowly becomes more crisp and bright really appealed to me.

4. GOTG Vol 2

This opening credits sequence focuses mainly on baby Groot dancing to music (as opposed to any of the other main characters or the fight sequence occurring at the same time). This, much like the Deadpool credits, also suggests the comedic nature of the film as it implies that Groot dancing is more important than the blurred battle sequence behind him - as Groot is always the one in focus and the centre of the shot. I also really like the choice of song - Mr Blue Sky - as it’s uplifting and happy, which again contrasts with the fight scene unfolding in the background and brutal imagery of the monster - adds to the humorous effect and sets the tone of the film nicely. Baby Groot also achieves this through his childish glee and carefree dancing. One of my favourite things about this title sequence is the bold colour palette which is used that contrasts the typical dark colours that are commonly used in the ‘space Sci-Fi movie’ stereotype - making it more memorable and unique. On top of this, they also give the movie a retro feel which is a key theme (the song also is reflective of this) as it’s Starlord’s motif. The names of the cast are also very bold and flashy so they are easily noticeable amongst all the action.

5. Wall-E

This end credits sequence tells the story of what happens after the film ends and features the song ‘Down to Earth’ which perfectly represents how the humans have to rebuild their world from the ground up - from the first plant. This sequence is very creative as it begins in a prehistoric style with drawings on the sides of walls depicting the story - but also with the addition of the futuristic robots and ships which makes for an interesting juxtaposition between the two. As the song progresses and the humans begin to live like normal people again- making wells and planting crops, the animation style changes to little animated drawings on a brown background- as if they too are progressing through time and becoming more advanced. The drawings eventually become painted and colourful as the world becomes more beautiful and the humans are able to live with nature again- suggesting that everything is finally okay. This colourful animation style also once again shows how time has changed the style. By the end of the sequence, the characters are drawn as pixel sprites - showing that finally everything is back to normal- they’ve progressed from being primitive like cavemen to living independently (like we do in our world)- much like the art style has advanced. I think the trailer is very clever in that aspect and makes me happy to know how the conclusion of the beloved film. I also like how this title sequence itself also seems to contrast with the futuristic motif of the ship and the world - with brown and green earthy colours instead of blues and whites that could connote technology.

artofthetitle.com

1 note

·

View note

Photo

@rice-22

So, we finished a review of this troll like a week ago, and you seem to have changed a lot of things, but save the sprite there are there very few pertaining to CD’s review? So in light of that I’m gonna be doing this second review instead of CD to see if I can bring anything different to the table. Furthermore, because your bio introduces multiple themes throughout, I’m going to go through once with light commentary and then make my changes at the very end when I’ve decided what themes to keep and which ones to toss.

Some info:in left i got him when he was the heir,i made an crown based on the fabric triangle some ghosts wear,also got an squid crown,got blinded for unknown reasons,got an squid cape that he hates and some cuffs that reflect how he is trapped on being the prince,on right theres him when ran from mean trollstodian,got an helmet and a bionic horn/tentacle,bad cover-up of his sign and the tentacles of his shoes are now off,id would like an re-design from the squid heir one,and the jelly runaway,also he does not look too muck jellyfishy….

Place:AU where theres an planet where trolls gets two custodians,an troll one and a lusus one,theres also a lot of communities like towns or villages,every one of them gets an fuschia leader and red bloods are important in society while limes are “trash”

Themes spotted: ghosts, squid, jellyfish?

Also, interesting concept of each principality having a fuchsia ruler! I guess in that context it makes sense for one to run away since there would be more fuchsias to fill the power vacuum.

Name:left is Glauce ?????? and right is Nomuro ??????,

Glauce is pluto’s twin and Nomuro comes from Nomura,one of the biggest species of jellyfish,and ro because is the termination on some japanese boy names

Additional theme: Pluto??? Also I assume that when you say left and right you just mean first and last name???

Age:7sweeps,god he looks like 4!!,(reference to the turritopsis nutricula)

Yeah that’s pretty cool. Especially since he’s starting a new life.

Strife Specibus:hornmade brush

Additonal theme: paint…ing? Based on CD’s review I guess in reference to squids.

Fetch Modus:shock modus,guessing game,the item that is needed will not shock and the other ones will give an i wish little shock

Additional theme: …electric eels, maybe, if we’re going with the underwater theme? Unless this is meant to be a reference to a jellyfish’s sting…

Blood color:fuschia/hemoanon

It looks like his second look is clearly tealblooded, though, instead of hemonanon!

Symbol and meaning: Pimini mixed with variant of planetary symbol of pluto

And this is also from CD’s review. Given how much you’ve changed I’m no longer sure this is the same squid troll as last time, though the visual similarities remain…

Trolltag:JovenBidente

Bidente is the combination of bident and seer on spanish,Joven is young

Hm so you seem to have fixated on “young” and “fuchsiablood,” which aren’t themes so much as parts of the character you want to highlight

Quirk: ]-ïmPortant stuff gets bidents-[

when theres an p and l together he types P_,double headed ï,uses symbols and caps,always cap P

I don’t think I fully understand this quirk beyond just being the first two letters of fuchsiablood signs?

Special Abilities (if any):seer powers like visions,also got mixed senses,can taste colors and feel sounds

And now we have a synesthesia ability? I guess that works pretty well with the squid thing…

Lusus:Jolly skid,an fusion between Jellyfish and an squid,also the name came from jolly rancher and skittles

Okay that’s pretty cute. Additional theme: candy? But maybe subsumed into the youth theme, which can be subsumed into the jellyfish one

Personality: shy,nervous but can flip to mad and brave

Interests:underrated stuff,jellyfish,necromancy

…ADDITIONAL THEME: NECROMANCY????

Title:seer of doom

Dream planet:Derse

Aight let’s go over the themes we found in this bio along with which themes can “eat” the other ones: squid (painting, synesthesia), jellyfish (ghosts/necromancy, youth/immortality (candy)), Pluto, and electric eels(?).

Hm. So if I wanted to collapse this into a couple broad and easily applicable themes, I’d probably stick with the jellyfish and squid? Which means I should go through and remove references to Pluto and electric eels?

Name: Which means, right off the bat, that we should change the first name from Glauce. Maybe Magfin, from the Bigfin Squid Magnapinna? They’re well known for being real freaky-looking squid with long, long tentacles that it uses to feed off the seabed, and are rarely even seen, which reinforces both the ghostly theme of hiding and the long chain of responsibilities that are difficult to escape.

Strife Specibus: Instead of paintbrushkid, maybe needlegun, like a tattoo machine?

Fetch Modus: I like the mechanic of the Shock Modus, so maybe we can just make it a Sting Modus with the same properties? We can also add in CD’s suggestion from last time of a Squid modus that works like a camouflaged tree modus.

Symbol: I agree that he’s a Doom player, a Dersite, and a Fuchsiablood, but I no longer think he needs the Pluto association? SO I might just make him straight-up Piminini again.

Trolltag: I think we can allude to him being “young,” to starting a new life, and to being a former heir without tipping our hand too strongly. How about splitImmortal? The “split” referencing his divided idenities as well as the bident, and “immortal” a reference to the immortal jellyfish you mentioned earlier as well as the fact that fuchsiabloods live significantly longer than their lower-blooded coutnerparts.

Quirk: I like the bident quirk, but I’d jettison the Pi quirk. For the rest maybe just a colon and an underlined equal sign after c? like so:

The quic:=k brown fox jumps over the lazy dog. Looks a little like a squid, or a jellyfish, or a ghost, or a skull.

Special Abilities: I like what you’ve given him! I would like if his visions of doom were similar confused due to his synesthesia.

Lusus: the lusis is cute as hell I wouldn’t take him away from you

Personality: I think it makes sense for this character to have two faces since so much of his character is based on splits, but I would expand on this a little more in terms of what circumstances would cause him to decide it’s worth standing up to someone. For example, it seems that he weighed the odds and decided that running away was the better option to standing up to his trollstodian.

Interests: I like the necromancy detail actually! Let’s add something arty to justify the whole ink thing.

Now to the redesign.

Both sprites are slightly edited from CD’s review last time!

Horns - This is an AU so I guess he doesn’t have to have Feferi’s horns, but I thought it would be worth trying on.

Hair - This is slightly edited from CD’s review of this troll since I felt it had the character you were going for.

Crown - The crown looked a little busy, so I gave him a tiara shaped like the top of a squid head and gave him a gem that imitated the top of the symbol!

Eyes - I know the “blind seer” is the most overplayed trope, but deep-sea squids and jellyfish often don’t have what we consider “eyes.” I went with a blind look more similar to when Sollux “died” rather than Terezi’s look

1) because a tealblood seer with red eyes would edge a little too close to Terezi

2) the black eyes look a little spookier, playing back into the ghost theme

3) this gives a stronger tie-in to his synesthesia since it will function similarly to Terezi’s strong sense of smell

Helmet - Since I made him blind, I wanted to give him a Geordie LaForge type visor for his helmet!

Scarf - most scarves in Homestuck just show the one side of it to get the visual across so that’s what I did.

Symbol - just changed it to straight-up Pimini

Shirt - for the teal sign, I gave his shirt a scalloped edge to better call back to the jellyfish/ghost themes, especially since his helmet gives his head a domes appearance. This way his fuchsiablood version leans more on squid themes and his tealblood version is more jellyfish!

Shoes - the tentacles made the design a little busy, so I took ‘em otu but kept the ink stains, since they’re a nice nod to the squiddyness of it all and also a reminder that no matter where he goes, he’ll leave some trace of himself.

And that’s everything! Hope this helped!

-TR

#rice-22#glauce nomuro#magfin nomuro#glauce#magfin#nomuro#seadweller#fuchsiablood#tealblood#(sorta)#review#redesign#tr review#submission#oh also for continuty I should add the prior tags#shinoi tanzul#shinoi#tanzul#dibran glauce#dibran#ok I think that should cover it for searchability

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

aa:p4 weaponry

I was thinking about it and maybe Pearls is the weaponsdealer this time round. Ok, to expand on this - I was thinking of giving them an item that would allow them to see clearly in the shadow world. A personal object that would, through spiritual energy, allows them to see clearly through the fogs in the shadow world like teddy’s glasses do for the p4 cast. Something like that.

I mostly got the idea from when Pearl imbued the magatama with spiritual energy, which allowed him to see Psyche Locks. I was wondering how to translate Pearl’s role here, since she’s an adorable little kid and I don’t want to leave her out, and this - spiritual sight clearing device! Which helps them channel certain powers, like Apollo’s Sight, Athena’s Hearing, Phoenix’s Psyche Locks, Miles Logic Chess etc., or help summon their personas. Or both.

My original thoughts were for Pearls to transform the Weapons into the form of their Personal Object, but small innocent Pearls getting access to weapons didn’t really sit right with me, so I changed it to Sight Clearing Object. I think it works better that way tbh.

Weapon dealers could be the detectives (at least for the first part - see this cool post by onyourwings for more details! Although nothing is set in stone yet haha :’D), but idk. hmm. I was kind of hoping to see them as support charas who have to go through their time in the tv world, but I think they could be the Real World Investigation Party Supporters or something. Again, not sure.

I wonder if I could get the Judge to be the Weapon dealer… but in terms of storyline he’s like Igor so… nggh I’ll just leave the slot open for now I guess.

Below lies their personal sight-clearing items and possible weapons Possible (not sure but here just in case) Spoilers for AA1-5.

DEFENCE ATTORNEYS

- Phoenix Wright -

Sight Clearing Object: Magatama | Weapon: Shield (mb with sword)

Magatama because that’s how he’s able to see all those psyche locks (like the fog!), which get him close to the truth. Plus, it is canon he gets his powers from the Magatama, leaving it out would be a gigantic travesty in my opinion haha.

Shield since I vision Phoenix as a very defence-based fighter, due to his ridiculous luck at escaping accidents. Seriously, coming out of a car crash with only a sprained ankle? A raging devil riverfall with only a cold? This guy’s stamina’s and defence is ridiculously high. Also, he just, I dunno, seems like someone who’s a really defensive fighter? Not the type to go all out attack straight off the bat, unlike some prosecutors we know. Not sure why I think that way tbh. So I gave him a shield.

But since he’s the original character, giving him a sword also works, since its unique in that he’s the only one who can switch into another stance, and gives him the chance to go more on the offensive. His defences would go down, but the boost in attack power should help cover for that. So his primary weapon is a shield, while his secondary weapon (which is admittedly not used much) is the sword. Preferably a guan dao or a sabre, since both can be used effectively in one hand and with a shield.

Darkness more than light, fire, ice, electricity, wind, the Wild card has all and protects them and humanity with his shield, sword hidden near his hip for the few cases when a defensive approach is no longer needed, when the time to attack is right.

- Apollo Justice -

Sight Clearing Object: Bracelet | Weapon: Bow

Bracelet! Because his bracelet is actually what he uses to concentrate his focusing power so eyy, too good to pass up. Also, its clearly very important to him. And aa5 proves that he’s unable to really turn it off so in this au I can just pass it off as a side effect that just revealed what was already there or something haha. So much plots I can use it for mwahahaha.

As for why the bow - Originally, it was gauntlets, but it didn’t feel right, and he has pretty much average strength. @onyourwings and @worldbeyondtheworld agreed and provided the perfect alternative - the Bow! Which fits ridiculously well considering that the God Apollo uses a bow. It’d put his sharp eyesight to good use too, and we definitely need more far-ranged members on this team. Pfft imagine him using his Chord of Steel to tell others to get out of the way while he shoots from a distance - it’d be both cute and badass!

Wind that carries his shouts to afar, that caresses his cheeks and ruffles his hair and guides his arrows directly to home, blowing back the enemies in a gale that is as determined as the hurricane of determination in his soul.

- Athena Cykes -

Sight Clearing Object: Widget | Weapon: Gauntlets

Ok, I chose Widget as the SCO because she often uses it to figure out the emotions she hears, which in turn helped her find the truth - and it’s important to her, as well, due to it being a memento from her mom. Plus, Widget is an emotional-measuring device, which can come in pretty handy to detecting emotional distress and helping people accept their shadow selves without another freakout. So Widget it is!

As for why she’s given gauntlets, well, canon states she’s got self defence training, and I still remember that scene where she body throws Apollo over her shoulder in AA5 (lol rip Apollo). She’s strong, pretty aggressive when angered and she’s also got a reaction gif of her smacking her fists together, like she’s preparing to punch someone, so. Gauntlets.

Bright, like fire and energetic, like the electricity that crackles around her body, sparking out of her fists as she slams them together in anticipation, thrumming and humming a tune so fine that only her ears can hear.

- Raymond shields -

Sight Clearing Object: Pink Notebook | Weapon: Hammer?

Ok, I know he only appears in AAI2. But he’s still kinda important (definitely more important than the Payne Brothers even though they appear nearly every game) and he’s a good guy. He’s definitely a key player, much like Sebastian and Kay. Plus, the defence team needs more people and I like him (I like all the charas in this game actually). And so here he is.

I chose the Pink Notebook as his SCO because its the only thing he had with him during the past and the present.

As for the hammer, well. We kind of needed one, and I couldn’t think of what would suit him well enough. So I just went with the hammer.

PROSECUTORS

- Miles Edgeworth -

Sight Clearing Object: White King Chess Piece | Weapon: Spear

Ok, the reason for the White King Chess Piece is because of the Logic Chess Sequences. In it, Edgeworth takes the white part of the chessboard, which is why his piece is White. And the King represents absolute authority and is the most important part of the game - without him you lose - So I figured that a King Chess Piece would work due to the symbolism. As the head Prosecutor and leader of Good on the Prosecuting Side, Miles more than deserves the White King Piece.

As for a Spear, well, I admittedly got the idea from aa1 case 5, the really long one that first introduced Emma Skye. The prosecuting award had the Spear so I thought ‘eyy, why not’ and thus, Spear. Plus it also serves as a good parallel to the Shield of Phoenix Wright - unbeatable Spear vs unbreakable Shield, which is alluded to in the awards in AA1 C5. Also! I forgot to add but World came up with the idea for Spear first - didn't include that bit because I was tired and forgot, sorry!

light and dark, intertwining with each other like yin and yang, centering around his spear and placing his soul to rest, driving him towards the truth.

- Franziska Von Karma -

Sight Clearing Object: Brooch |Weapon: Whip

I had trouble thinking this one up, but while I was looking over her character pictures I noticed a similarity - that blue brooch she wears at her neck. It appears in every single one of her sprites. Not even joking - official art, AA2, AA3, even AAI2 she has that same brooch at her neck. Clearly its an important part of her daily attire, so it serves pretty well as her SCO, I think.

She uses the whip in game as a tool of subjugation, so its pretty much canon for her already. Nine-O-Cat tails is probably the ultimate whip for her to unleash her wrath on the foolishly foolish shadows, although I don’t think she’d unleash that wrath onto people while holding the Nine-O-Cat tail whip. That thing was used as a torture weapon during the middle ages - its pretty brutal. I pity anyone who earns her wrath while she’s holding her normal whip, though.

Ice, so cold that it burns deep inside her heart like true fire, causing frostbite and ice to form wherever her whip struck.

- Sebastian Debeste -

Sight Clearing Object: Baton | Weapon: Knives

Sebestian uses the Baton in his animations, which is good enough for me. It’s probably pretty important to him, and somewhat iconic for him.

As for the knife, well. Originally I thought sword, to rival Edgeworth, but we’ve already got Simon as the Swordmaster. So I tried thinking about something similar to a baton in terms of length and maneuverability, and I came upon Knives. Around the same length as the baton, and serves as a good close-range weapon- although Sebastian with a knife is.... well, he’ll have to go straight up to fight them close range. And he seems a pretty scaredy guy. I dunno. But hey - he ran straight to the dumpster to dig up evidence! And stood up to his douchebag of a dad! So kid’s got guts.

Or alternatively chakra sticks! They’re like sticks, but held in both hands and used for attacking. That could work.