#intermontane

Text

Patagona chaski Williamson et al., 2024 (new species)

(Illustration of the type specimen of Patagona chaski by Jillian Ditner, from Williamson et al., 2024)

Meaning of name: chaski = messenger [in Quechua, referring to relay runners of the former Inka Empire, who exhibited exceptional speed, endurance, and memory, similar to this bird species]

Suggested common name: Northern giant hummingbird

Age: Holocene (Meghalayan), extant

Where found: Arid and semiarid habitats along the west slope of the Andes and in intermontane valleys, at altitudes of 1800–4300 m above sea level

How much is known: At least 193 collected specimens are held in museum collections.

Notes: P. chaski is a hummingbird. Weighing between 16–26 g, it is the largest known hummingbird in the world. Until recently, it was considered the same species as the closely related P. gigas. However, a new study on the migratory habits, genetics, and morphology of these hummingbirds suggests that two distinct species should be recognized.

Whereas P. gigas breeds at low elevations and migrates northward to higher elevations, P. chaski remains at high elevations all year round. P. chaski can be found further north than P. gigas (hence the proposed common name "northern giant hummingbird"), but it overlaps with the non-breeding range of P. gigas in the southern parts of its range.

Genetic comparisons suggest that the two species diverged from one another over 2 million years ago, though they remain difficult to tell apart based on appearance. In addition to being slightly larger than P. gigas on average, P. chaski generally has a whitish (as opposed to brownish) throat and a more obvious white ring around the eye.

Reference: Williamson, J.L., E.F. Gyllenhaal, S.M. Bauernfeind, E. Bautista, M.J. Baumann, C.R. Gadek, P.P. Marra, N. Ricote, T. Valqui, F. Bozinovic, N.D. Singh, and C.C. Witt. 2024. Extreme elevational migration spurred cryptic speciation in giant hummingbirds. PNAS 121: e2313599121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2313599121

#Birblr#Dinosaurs#Birds#Patagona chaski#Northern giant hummingbird#Holocene#South America#Strisores#2024#Extant#Animal remains#Animal death

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

Allen's Lookout, BC (No. 1)

The Liard River of the North American boreal forest flows through Yukon, British Columbia and the Northwest Territories, Canada. Rising in the Saint Cyr Range of the Pelly Mountains in southeastern Yukon, it flows 1,115 km (693 mi) southeast through British Columbia, marking the northern end of the Rocky Mountains and then curving northeast back into Yukon and Northwest Territories, draining into the Mackenzie River at Fort Simpson, Northwest Territories. The river drains approximately 277,100 km2 (107,000 sq mi) of boreal forest and muskeg.

The river habitats are a subsection of the Lower Mackenzie Freshwater Ecoregion. The area around the river in Yukon is called the Liard River Valley, and the Alaska Highway follows the river for part of its route. This surrounding area is also referred to as the Liard Plain, and is a physiographic section of the larger Yukon–Tanana Uplands province, which in turn is part of the larger Intermontane Plateaus physiographic division.

The Liard River is a crossing area for Nahanni wood bison.

Source: Wikipedia

#Allen's Lookout#BC#Liard River#travel#original photography#vacation#tourist attraction#landmark#landscape#countryside#British Columbia#woods#forest#nature#flora#tree#river bank#wildfire smoke#summer 2023#Canada#view#vista point#boreal forest#Northern Rockies#Rocky Mountains

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Climate of Oregon

See Weather Forecast for Oregon today: https://weatherusa.app/oregon

See more: https://edition.cnn.com/2024/05/08/weather/tornadoes-michigan-tuesday-storms-wednesday/index.html

Oregon's climate varies considerably due to its diverse geography, but it's generally characterized by mild, wet winters and warm, dry summers. The state is influenced by several factors including its proximity to the Pacific Ocean, the Cascade Range, and the Columbia River Gorge. Here's a breakdown:

Western Oregon:

Winter: Mild and wet, with temperatures averaging in the 40s to 50s Fahrenheit (4-10°C). Rain is frequent, especially from November to March.

Summer: Warm and dry, with temperatures typically in the 70s to 80s Fahrenheit (21-32°C). Some areas experience occasional fog in summer.

Eastern Oregon:

Winter: Colder than the western part of the state, with temperatures dropping below freezing. Snow is common in the mountains and higher elevations.

Summer: Hotter and drier than the western part, with temperatures often reaching the 90s Fahrenheit (32-37°C) and occasionally higher. It's also less cloudy and receives less precipitation.

Southern Oregon:

Winter: Generally milder compared to eastern Oregon, but cooler than the western region. Snow can occur in higher elevations.

Summer: Warm to hot, with temperatures ranging from the 80s to 90s Fahrenheit (27-37°C). It can get quite dry, especially in areas further from the coast.

Coastal Areas:

Winter: Mild and wet, with temperatures similar to western Oregon. Storms from the Pacific Ocean can bring heavy rainfall.

Summer: Cooler compared to inland areas, with temperatures often in the 60s to 70s Fahrenheit (15-26°C). Fog is common, particularly in the mornings.

See more: https://weatherusa.app/zip-code/weather-97308

https://weatherusa.app/zip-code/weather-97296

https://weatherusa.app/zip-code/weather-97281

The Cascade Range acts as a barrier, creating a rain shadow effect, which means that the western slopes receive more precipitation than the eastern slopes. Overall, Oregon's climate is conducive to lush forests in the west and semi-arid conditions in the east. However, microclimates can vary significantly based on factors such as elevation, proximity to water bodies, and local geography.

That's a comprehensive overview of the varied climates across Oregon!

Coastal Area:

Equable, mild, marine conditions.

Moderate temperatures with July averaging in the upper 50s °F (about 14 °C) and January in the low 40s °F (about 5 °C).

Relatively dry summers but with cloudy and wet seasons.

Annual precipitation ranging from 60 to 120 inches (1,500 to 3,000 mm) or more.

Lowlands (Willamette, Umpqua, and middle Rogue rivers):

Warmer summers and slightly cooler winters compared to the coast.

July temperatures average about 70 °F (21 °C) with 65 to 70 percent of possible sunshine; January averages about 40 °F (4 °C).

Rainy season from October through April with precipitation averaging 35 to 40 inches (900 to 1,000 mm), except in the middle Rogue valley, where it's 20 to 25 inches (500 to 650 mm).

Cascade Range:

Copious winter precipitation with significant snowfall.

Short, dry, sunny summers.

January temperatures below freezing above 3,000 feet (900 meters).

Snowfall from October to April with patches persisting until July.

July average temperatures between 50 and 60 °F (10 and 15 °C).

North-Central Oregon Plateau:

10 to 20 inches (250 to 500 mm) of annual precipitation, mainly in winter.

Sunny summers with July temperatures averaging in the low 70s °F (about 23 °C).

Brisk winters with January temperatures averaging in the low 30s °F (about 1 °C).

Blue-Wallowa Mountains:

Climates vary by location.

Intermontane basins and valleys similar to the north-central plateau but with colder winters.

Higher elevations receive heavy precipitation, much of it as snow during winter.

These diverse climate patterns in Oregon are influenced by factors such as proximity to the ocean, prevailing wind and storm paths, and topography and elevation, as you mentioned.

See more: https://weatherusa.app/zip-code/weather-97259

https://weatherusa.app/zip-code/weather-97258

https://weatherusa.app/zip-code/weather-97236

https://weatherusa.app/zip-code/weather-97231

Oregon's diverse forest landscapes and varied animal life contribute to its rich biodiversity.

Forest Cover:

Eastern Two-Thirds of the State: Dominated by ponderosa pine, large sagebrush, and western juniper, along with various annual grasses and wildflowers.

Blue-Wallowa Mountains and Eastern Slopes of the Cascades: Abundant stands of ponderosa pine along with bitterbrush, green manzanita, and herbaceous plants.

Western Slopes of the Cascade, Klamath, and Coast Ranges: Heavy forests primarily consisting of Douglas fir, with varying understory vegetation depending on the age of the stand. Cleared areas in the coastal region feature alder and noncommercial deciduous growth.

Alpine Zones:

Mountains: Alpine zones host larch, mountain hemlock, alpine firs, and mountain mahogany in the Blue Mountains.

Animal Life:

Deer and Elk: Flourish in less-populated areas.

Antelope: Found in the eastern high plateau.

Bear and Fox: Found in mountain foothills.

Coastal Waters: Home to sea lions and sea otters.

See more: https://weatherusa.app/zip-code/weather-97230

https://weatherusa.app/zip-code/weather-97064

https://weatherusa.app/zip-code/weather-97067

This description underscores how Oregon's flora and fauna are closely tied to its climatic zones and diverse ecosystems. The state's abundant forests provide habitats for a wide range of plant and animal species, contributing to its natural beauty and ecological importance.

0 notes

Text

Land of Japan:

youtube

-Taishō Pond in Kamikōchi Valley, central Honshu, Japan. Mount Hotaka behind.

The mountain arcs correlate to Japan's primary physiographic regions: Hokkaido, Northeastern (Tōhoku), Central (Chūbu), and Southwestern—as well as the Ryukyu and Bonin archipelagoes. The Chishima and Karafuto arcs merged to form the Hokkaido region. The backbone of the area runs north to south. The Chishima arc reaches Hokkaido as three volcanic chains with altitudes exceeding 6,000 feet (1,800 metres), which form a ladder and finish in the region's core. The Kitami Mountains in the north and the Hidaka Range in the south are the mountain system's main components.

-Lake Towada, Towada-Hachimantai National Park, northern Honshu, Japan.

The Northeastern Region runs from southwest Hokkaido to central Honshu, almost paralleling the northeastern mountain arc. Several rows of mountains, valleys, and volcanic zones are closely aligned with the insular arc of this region, which is convex towards the Pacific Ocean. The Kitakami and Abukuma mountains on the east coast deviate from the normal trend; they are primarily formed of older rocks, with plateau-like landforms surviving in the core. In the western zone, the formations follow the overall trend and consist of a basement complex overlain by thick accumulations of young rocks that have undergone modest folding. The East Japan Volcanic Belt includes the Ōu Mountains, which are separated from the coastal ranges by the Kitakami-Abukuma lowlands to the east and a succession of basins to the west.

-The Hida Range, part of the Japanese Alps, in central Honshu, Japan.

The Central Region in central and western Honshu is defined by the convergence of the Northeast, Southwest, and Shichito-Mariana mountain ranges around Mount Fuji. The mountain, lowland, and volcanic zones form a nearly right-angled pattern over the island. The Fossa Magna, a massive rift valley that runs from the Sea of Japan to the Pacific, is the most remarkable physical feature on Honshu. It is largely covered by mountains and volcanoes from the southern section of the East Japan Volcanic Belt. Intermontane basins are located between the partly glaciated Akaishi, Kiso, and Hida mountains (Japanese Alps) to the west and the Kantō Range to the east. The Kantō Plain, located east of the Kantō Range, is Japan's largest lowland. Tokyo, the country's largest metropolis, occupies a significant portion of the plain.

-Coast of the Inland Sea, Okayama prefecture, Japan.

The Southwestern Region, which comprises western Honshu (Chūgoku), Shikoku, and northern Kyushu, largely correlates with the southwestern mountain arc. The overall tendency of highlands and lowlands is broadly convex towards the Sea of Japan. The area is separated into two zones: the inner zone, generated by complicated faulting, and the outer zone, formed by warping. The Inner Zone is mostly made up of ancient granites, Paleozoic rocks (250 to 540 million years old), and geologically more recent volcanic rocks that are placed in complex juxtapositions. The Outer Zone, which includes the Akaishi, Kii, Shikoku, and Kyushu mountain groups, is distinguished by a consistent zonal arrangement from north to south of crystalline schists and Paleozoic, Mesozoic (65 to 250 million years old), and Cenozoic formations. The Inner Zone, focused on the Chūgoku Range, has a complex mosaic of fault blocks, whereas the Outer Zone is continuous except for sea straits that divide it into four autonomous groupings. The Inland Sea (Seto-naikai) is the location with the most depression, resulting in seawater incursion. The northern margin of the Inner Zone is studded with massive lava domes generated by Mount Dai, which, along with volcanic Mount Aso, conceal a large portion of the western extension of the Inland Sea in central Kyushu.

-The caldera of Mount Aso in central Kyushu, Japan

The Ryukyu Islands Region comprises the majority of the Ryukyu arc, which extends into Kyushu as the West Japan Volcanic Belt and ends with Mount Aso. The arc's effect may be observed in the pattern of elongated islands off western Kyushu, such as Koshiki, Gotō, and Tsushima. The Izu-Ogasawara Region, to the east of the Ryukyu arc, consists of a series of volcanoes on the undersea ridge of the Izu-Marina arc, and the Bonin Islands, which include Peel Island and Iwo Jima.

Havard referencing:

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (1998). The major physiographic regions. [Online]. britannica. Last Updated: 27 October 2023.. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/place/Japan/Soils [Accessed 19 February 2024].

1 note

·

View note

Text

“regions of north america:

far north, rocky mountains, pacific northwest, intermontane west, california, mexamerica, great plains, great lakes/corn belt, island south, coastal south, megalopolis, quebec, atlantic”

#screenshot#my screenshots#thoughts#ideas#regions#geography#North America#America#USA#Canada#Mexico#california#maps

0 notes

Text

Appalachian Mountains

DID YOU KNOW??? The Appalachians, Scottish Highlands & Atlas Mountains of Morocco were all connected as the Central Pangean Mountains, which were as tall as the Himalayas are today.

They are believed to be the oldest mountain ranges in the world.

During the Permian era (around 295 million years ago), they were subjected to intense weathering, reducing the peaks to around half their original size and creating numerous deep intermontane valleys.

Visiting the Scottish Highlands, it's easy to see why my Scots-Irish ancestors who immigrated to America found the Appalachians (of which the Blue Ridge Mountains are a sub-range) to remind them of home!

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Bromacker Fossil Project Part X: Tambaroter carrolli, an amphibian with a wedge- shaped head

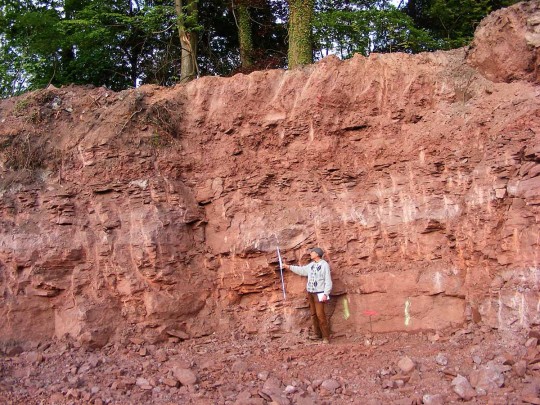

Thomas Martens at the construction site for a new store in Tambach-Dietharz where he found fossils by checking loose pieces of rock on the excavation floor. Photo by Stephanie Martens, 2008.

Paleontologist Thomas Martens has an amazing ability to find fossils. After he discovered the first vertebrate fossils at the Bromacker site in an abandoned commercial quarry in 1974, he and his father Max found additional fossils in the bottom of a deep pit they’d dug with hand tools, an excavation that Dave Berman, Stuart Sumida, and I fondly dubbed the “elevator shaft.” Years later, Thomas used funding from the German federal government to drill rock cores in the field surrounding the Bromacker quarry to help understand the geology of the fossil deposit. Amazingly, at one of the spots Thomas had selected, the drill core penetrated a skeleton of Diadectes absitus. So, it wasn’t surprising that in 2008 Thomas found a skull and partial skeleton of D. absitus and a small skull of a fossil animal new to science at a construction site for a new store in the nearby village of Tambach-Dietharz.

Dave Berman (left) and Stuart Sumida (right) pose with a shopping cart in front of the Netto Discount Store, which was built in the excavation site where Tambaroter was found. Rocks of the Tambach Formation can be seen behind the retaining wall. Photo by the author, 2008.

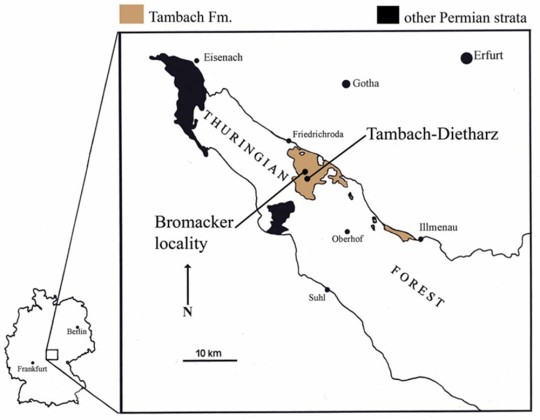

It makes sense, however, that vertebrate fossils were found close to the Bromacker quarry. Fossils from the Bromacker were preserved in the Tambach Formation, a 200–400-foot-thick unit of sediments that were deposited in the small intermontane Tambach Basin about 290—283 million years ago during the Early Permian Epoch. The Tambach Basin covered an area of about 155 square miles and was internally drained; that is, there were no rivers or streams flowing into and out of the basin. During periods of extremely heavy rain, water and mud would flow down the basin sides in what are called sheet floods and pool in the basin center, which is where the present day Bromacker quarry and Tambach-Dietharz are thought to be located. Any animals killed during these events would be carried by the sheet floods to the basin center where they’d have been quickly and deeply buried in mud settling out of the ponded water and later become fossilized. It is assumed that animals captured by the sheet flood events inhabited the Tambach Basin, because carcasses couldn’t have been carried into the basin by rivers and streams.

Map of Germany with inset showing the Bromacker locality and the nearby town of Tambach-Dietharz. Although the Tambach Basin in which the Tambach Formation was deposited covers about 155 square miles, outcrops of the Tambach Formation today occur in an area of only about 31 square miles.

While preparing Bromacker fossils, I’d typically read literature related to the fossil I was working on, write notes on what I thought were important features in the fossil, and give my notes to the person leading the project. When Dave was the lead, we’d typically have lots of discussion about certain features preserved in the animal, conversations that often directed the course of preparation. This time, in addition to preparing the new find, I was designated as the lead author for the publication that would name and describe it.

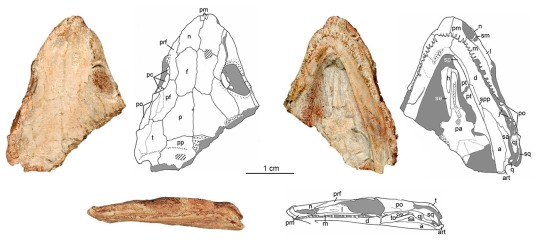

View of the underside of the skull of Tambaroter carrolli before preparation. The shiny area surrounding the skull is glue, which I applied to a crack to stabilize the specimen before preparation could begin. I had to free the skull from the surrounding rock before exposing as much of it as possible through preparation. Photo by the author, 2008.

Tambaroter is a member of the Microsauria, a diverse group of small amphibians that were once thought to be reptiles, a hypothesis that some paleontologists are currently revisiting. Microsaurs inhabited a variety of habitats and exhibited a range of body forms. Some were highly terrestrial with limb proportions similar to those of lizards, whereas others were aquatic and had elongated bodies and reduced girdles and limbs. Still others were adapted for burrowing or rooting through leaf litter. Tambaroter belongs to this latter-most group, which is named Recumbirostra for their recurved snout, in which the front of the mouth is overhung by the snout.

Photographs and line drawings of the skull of Tambaroter carrolli in (clockwise from upper left) dorsal (top), ventral (underside), and left lateral (side) views. Photographs by the author, 2008 and drawings by the author and modified from Henrici et al., 2011.

Tambaroter is member of the recumbirostran subgroup Ostodolepidae. I coined the name Tambaroter, which is derived from “Tamb,” for the Tambach Formation, and the Greek “aroter,” meaning plowman, in reference to the snout shape. Two previously named ostodolepids, Micraroter and Nannaroter, have the “aroter, suffix in their name, so usage of the “aroter” suffix was a continuation of this. The species name, carrolli, honors microsaur expert Robert Carroll (then Curator Emeritus at the Redpath Museum, McGill University, Montreal, Canada).

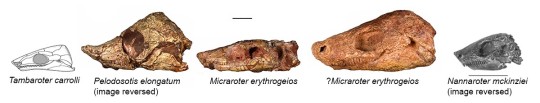

Skulls of representative ostodolepid microsaurs from geologically oldest (left) to youngest (right). A reconstruction drawing of the skull of Tambaroter was used instead of a photograph for comparison because the original fossil skull is extremely flattened (see previous image). Photographs, except for that of Nannaroter, by the author, 2009. The photograph of Nannaroter was modified from Anderson et al., 2009. Tambaroter skull reconstruction by the author and modified from Henrici et al., 2011. Scale bar of the tiny Nannaroter and other ostodolepids equals 1 cm.

When Tambaroter was published on in 2011, it was the first ostodolepid to be found outside of the USA (the others are from Oklahoma and Texas) and is the oldest one known. Other, possible ostodolepids have since been described from the American Midwest and Germany. All ostodolepids have a wedge-shaped skull and recumbent snout, which is accentuated in Pelodosotis. Based on these features, scientists think that ostodolepids burrowed or searched for worms and other prey in leaf litter. Remarkably, the skull of the tiny Nannaroter is so strongly built that it could have withstood burrowing headfirst into the ground by using its shovel-like snout to loosen dirt and its broad, flat head to push soil against the burrow ceiling. Because the sutures between individual skull bones in the Tambaroter type specimen are not tightly fused together, we think it belonged to a juvenile, so we don’t know if the adult skull would’ve been as strongly built as that of Nannaroter.

Life drawing of the ostodolepid microsaur Pelodosotis elongatum, which is known by a nearly complete specimen. Tambaroter probably had a similar body shape, though its skull would not have been as strongly wedge-shaped. Drawing modified by Carnegie Museum of Natural History Scientific Illustrator Andrew McAfee from outline drawing in Carroll and Gaskill (1978).

Stay tuned for my next post, which will feature one of the Bromacker’s top carnivores. To learn more about Tambaroter, read the publication that described the animal here.

Amy Henrici is Collection Manager in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

More on how the inland temperate rainforest region of the interior Pacific Northwest hosts one of the single most biodiverse epiphytic lichen communities in the world, with higher arboreal lichen biodiversity than the coastal temperate rainforest.

An old-growth cedar stand typical of inland temperate rainforest, at BC’s Ancient Forest / Chun t’oh Whudujut Provincial Park. [Photos from Ancient Forest Alliance.]

“Smoker’s lung lichen” (Lobaria reigera) is a rare arboreal lichen that is mostly limited to the temperate rainforests of the Great Bear Rainforest and Pacific coastline, but some isolated populations are also found in the inland temperate rainforest region. [Photo by P. Bartemucci.]

Since 2002, the Valhalla Wilderness Society has sponsored research on inland rainforest lichens by lichenologist Toby Spribille, formerly based at the University of Gottingen, Germany. Spribille has worked closely with BC lichenologists Curtis Bjork and Trevor Goward. They have found that the inland temperate rainforests contain one of the richest tree lichen floras in the world -- richer than BC’s coastal temperate rainforest. Spribille, Bjork, and Goward found more species of lichens in the Incomappleux Valley than tree, shrub, herb, grass and moss species combined. [Source: Valhalla Wilderness Society, 2008.]

Temperate rainforest ecosystems have been widely recognized as a major repository for biodiversity, particularly for organisms that live within forest canopies. In western North America, coastal temperate rainforest ecosystems have been the focus of increased attention in recent years. [...] However, in British Columbia (B.C.) a second major temperate rainforest ecosystem is found on the windward slopes of interior mountain ranges. This inland temperate rainforest (ITR) has many unique characteristics, including globally significant assemblages of canopy lichens and mosses. Some 40% of oceanic epiphytic macrolichens found in Pacific coastal rain forests also occur in these inland rainforests. Among oceanic epiphytic species found in the inland rainforest are the hanging moss (Antitrichia curtipendula) and lichen genera such as Chaenotheca, Chaenothecopsis, Collema, Fuscopannaria, Lichinodium, Lobaria, Nephroma, Parmeliella, Polychidium, Sphaerophorus, and Sticta conclude that “conifer forests of intermontane British Columbia support at least 31 cyanolichen species -- one of the richest epiphytic cyanolichen assemblages in the world”. They suggest that maximum cyanolichen diversity is associated with the co-occurrence of nutrient-rich sites in lowland old-growth inland rainforest sites. [Source: “Predicting canopy macrolichen diversity and abundance within old-growth inland temperate rainforest.” Forest Ecology and Management, 2009.]

We report our initial findings of 39 lichen taxa, including several rare species and cyanolichens, which may be especially sensitive to climate. […] Some of the world’s most famous temperate rainforests occur along the west coast of North America. A lesser known, but equally unique ecosystem is the inland temperate rainforest (ITR), which is predominantly located in British Columbia between 50° and 54°N. The ITR shares many characteristics with its coastal counterparts, including large diameter western redcedar (Thuja plicata), some speculated to be over 1000 years old (Radies et al. 2009), and a dense understorey of devil’s club (Oplopanax horridus). This ecosystem provides important habitat for many species, including the threatened mountain ecotype of woodland caribou, and many disjunct populations of characteristically coastal lichen species. Old-growth coniferous stands in the ITR support exceptionally rich epiphytic lichen communities, especially cyanolichens lichens that have a cyanobacterial photobiont as one of their symbiotic partners. [Source: “A Framework for Climate Monitoring with Lichens in British Columbia’s Inland Temperate Rainforest.” Journal of Ecosystems and Management.]

Biatora aureolepra, an arboreal lichen species formally described in 2009, from the inland temperate rainforest. Photo from: “Contributions to an epiphytic lichen flora of northwest North America: Eight new species from British Columbia inland rain forests” (2009).

Coral lichen (Sphaerophorus venerabilis), an arboreal lichen from the inland temperate rainforest that requires the presence of old-growth cedar-hemlock stands. [Photo by David Moskowitz.]

818 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Morava-Vardar depression must ultimately dominate

Austria’s ambition to seize for her own uses a channel to the sea which should not open on the enclosed Adriatic has been the mainspring of her reactionary policy in Balkan affairs. Bulgaria, realizing that the nation which dominates the Morava-Vardar depression must ultimately dominate the politics of the peninsula, precipitated the second Balkan war in order to make good by force of arms her claim to a section of the trench; and the same incentive played an important part in determining Bulgaria’s alliance with the Teutonic powers in the present conflict. Most of the friction between Greece and the Entente Allies had its inception in the fact that Greece controlled one section of a channel all of which was essential to the existence of Serbia. The Belgrade-Saloniki railway was the main artery of commerce which carried through the trench the lifeblood of a nation.

The physical characteristics of the Morava valley as far south as Nish have already been discussed in connection with the Morava-Maritza trench. Prom Nish southward to Leskovatz road and railway traverse one of the open intermontane basins which frequently occur in the midst of the Balkan ridges; but farther south the stream flows from a youthful gorge which continues up the river for ten or twenty miles before the valley again broadens out to a somewhat more mature form. Just north of Kumanovo lies the divide between the Morava and Vardar drainage, a low, inconspicuous water-parting some 1,500 feet above sea-level, located in the bottom of the continuous, through-going trench, and placing no serious difficulties in the way of railroad construction.

South of Kumanovo

South of Kumanovo the valley broadens into a triangular lowland, near the three corners of which stand Kumanovo, tiskiib, and Veles. The main Vardar River enters the lowland from the west, flowing out again at the south through a narrow, winding valley which carries the railway, but no good wagon road. At Demir Kapu the valley narrows to an almost impassable gorge for a distance of several miles but soon broadens again to a flat-floored valley in which the river follows a braided and occasionally meandering channel to the sea. The lower course of the Vardar lies in a very broad, marshy plain terminating in the delta southwest of Saloniki. The special strategic importance of the triangular lowland near Uskiib and the Demir Kapu gorge will be emphasized later.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Fossil flower

The exceptional preservation of this Eocene (56-34 million years ago) flower is due to the fine grained nature of the limestone in which it was entombed. The specimen comes from the Green River Formation covering parts of the North American Midwest towards the end of the uplift of the Rocky Mountains. The formation was deposited in the intermontane basins between the chains of growing peaks, and includes a mixture of terrestrial swamp and river sediments and deep lake sequences, which were surrounded by swampy areas with a profusion of warm climate plants. The formation is world famous for its fossil freshwater fish and the formation dates from between 53.5 and 48.5 million years ago.

Some of these plants turned into coal seams, while the spring algal blooms in the lakes produced oil shales in the anoxic lake bottom oozes. Some of the lake sediments are varved, with fine laminations that record seasonal changes between organic rich dark sediments from the short mountainous growing season and thin layers of light coloured sediment deposited in winter from suspended particles in the lake water. The best preserved fossils are found in these varved oozes, which are made of very fine grained limy mud. The fossils are well dated due to layers of volcanic ash interleaved in the sediments that were erupted from the nearby Yellowstone caldera and San Juan volcanic field. The area is designated as a Lagerstatte, a German word used to denote an area of rock with exceptional or important fossils.

Loz

Image credit: NPS

http://geology.com/articles/green-river-fossils/[_

_](https://www.facebook.com/TheEarthStory/photos/a.352867368107647/853838988010480/?type=3&theater#)

#Fossil#flower#plant#eocene#green river formation#paleontology#paleobotany#fossils#taphonomy#fossilfriday#lagerstatte#the earth story

307 notes

·

View notes

Text

Así fue definida la cuenca del Valle Superior del Magdalena

La cuenca de VSM fue clasificada como una intermontane basin formada en Mesozoico-Cenozoico por la orogenia de los Andes (Cediel, Shaw & Cáceres, 2003). Pero antes, de ese evento, ocurrieron otros 3: La colisión Orinoquiana (Grenvillian), La orogenia tipo cordillera (Ordovícico-Silúrico medio) y la formación y desarrollo del Aulacógeno Bolívar (Cediel et al.,2003).

Referencias

Sarmiento, L. F., & Rangel, A. (2004). Petroleum systems of the upper Magdalena Valley, Colombia. Marine and Petroleum Geology, 21(3), 373-391.

Cediel, F., Shaw, R. P., & Cáceres, C. (2003). Tectonic assembly of the Northern Andean block. The Circum-Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean: Hydrocarbon Habitats, Basin Formation and Plate Tectonics: American Association of Petroleum Geologists Memoir, 79, 815–848.

Roncancio, J., & Martínez, M. (2011). Upper Magdalena Basin Vol.

14 (p. 183). Medellín, Colombia: ANH-University EAFIT. Department of Geology.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Eddontenajon Lake, BC (No. 4)

The interior intermontane plateau receive about 400 mm of annual precipitation, much less than the 1000 to 1500 mm levels in the eastern mountains, and the even higher levels in the western mountains. Snowfall accounts for 35 to 60% of all precipitation. Winters are long and cold, with January mean temperatures between -15 °C and -27 °C. Summers are warm but short, with July mean temperatures between 12 °C and 15 °C.

Alpine weather is more typical beyond the tree line at elevations above 1000 m, where frost can develop year-round. Average temperatures here remain below freezing for most of the year, and snowfall accounts for at least 70% of precipitation. Permafrost is typical in these regions, allowing for the growth of only shrubs, mosses and lichens.

Sudden violent storms may occur in the area during the summer, usually due to moist air masses arriving from the Pacific Ocean. Usually, however, the Pacific moderates the climate in this ecozone.

Source: Wikipedia

#Eddontenajon Lake#Stewart Highway#original photography#travel#vacation#tourist attraction#landmark#landscape#countryside#nature#Canada#summer 2023#fir#the North#cityscape#forest#woods#flora#food#British Columbia#wildflower#Stikine Highway#reflection#mountains#Stikine Country#lake shore#clouds#beach

0 notes

Link

There’s an assumption B.C. is powered by ‘clean’ hydro, but the reality is most of the energy we use is fossil fuel: gasoline, diesel, natural gas and furnace oil.

Electrifying transport and buildings is our biggest opportunity to cut emissions. It could save households thousands of dollars a year, and create an army of good-paying local jobs.

But it will require a lot more juice. A pressing question is: do we rely on last century’s destructive meg dam model to create it? If we don’t build new renewable capacity quickly, we could find ourselves charging electric cars with coal power purchased from Alberta or Wyoming.

But rather than encourage people trying to generate clean, local electricity, BC Hydro is cancelling existing contracts and trying to kill new projects in the cradle.

The desire to improve people’s lives and fight climate change inspired Ktunaxa energy champion Marty Williams to propose a large scale solar farm in his home community of ʔaq̓am – a project he’s been working on for more than 10 years. I listened to his story while attending Clean Energy BC’s Generate 2019 conference. I’ll be interested to know if you feel the same conflicting emotions of inspiration and anger after you hear it.

Ktunaxa territory encompasses a vast stretch of land in what we call the Kootenays. It’s an almost indescribable place comprising broad valleys and high peaks with beautiful intermontane plains. Ktunaxa territory is where the Columbia, the most important river west of the Great Divide, originates. It’s also the breadbasket for British Columbia’s hydro-electric generation system. Half of all the electrical power produced in B.C. comes from the Kootenays.

British Columbians have derived huge benefits from, and may even feel a sense of pride in, the tremendous amount of stored hydro power we control. That’s probably because it didn’t cost us our land or livelihoods. When we travel through Nakusp, Revelstoke or Nelson today we see majestic lakes, huge slow-moving rivers and impressive dams. Ktunaxa elders like Marty see underwater graves, flooded village sites, unuseable hunting territories and rivers without salmon.

The proposed 26 megawatt Ktunaxa solar farm could be an affordable source of renewable power twenty times the size of anything built so far in the province.

ʔaq̓am has a construction partner signed and ready to go. They’ve selected a site and completed an archeological survey. The project would sit under power lines already running across the reserve. But BC Hydro refuses to sign.

Adding insult to injury, a visiting bureaucrat told the community at ʔaq̓am they should scale their project down. To dream small. And maybe, they said, hook up some solar panels to the local casino. This in a year when reservoirs across B.C. were low (proving to be a recurring phenomenon) and we imported $55 million worth of dirty energy to make up the shortfall.

Read More

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Koepcke’s Screech-Owl (Megascops koepckeae) is a poorly known owl that is endemic to northern and central Peru; it occurs along the west slope of the Andes from Cajamarca south to Lima, and in dry intermontane valleys from Amazonas south to Apurímac.

Koepcke's Screech-Owl is similar in appearance to Peruvian Screech-Owl (Megascops roboratus), and indeed Koecke's was not even recognized as a separate species until the early 1980s. Koepcke’s Screech-Owl is slightly larger than Peruvian, has a paler crown and forecrown, and lacks a pale band across the nape. The stuttering, staccato song of Koepcke's also is very different from the purring trill given by Peruvian.

Koepcke's Screech-Owls inhabit wooded areas and arid forest patches on Andean slopes, as well as Polypeis woodland in the upper montane zone. Koepcke's Screech-Owl is named in honor of Maria Koepcke, a pioneering field biologist and the leading ornithologist in Peru during the 1950s and 1960s. The biology of Koepcke's Screech-Owl is very poorly known, and while its life history no doubt is similar to that of other members of the genus, much further research is required to determine the status, ecology, and biology of this species.

[x]

72 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Purple-throated Euphonia | Eufonia de Garganta Púrpura | Euphonia chlorotica @ Tarapoto, Perú | August 2014 - In Perú, the beautiful Purple-throated Euphonia is common below 1,400 MASL in intermontane valleys, river-edge forests and second growth in Amazonia. They have a strong bill and short tail, and males are glossy blue above and yellow below, with a relatively small yellow cap. Fortunately, this small bird’s population appears to be stable, and thanks to its extremely large range throughout a great part of South America, it is also not threatened. - En Perú, la hermosa Eufonia de Garganta Púrpura es común por debajo de los 1,400 MSNM en valles, bosques ribereños y crecimientos secundarios en la Amazonía. Tienen el pico fuerte y la cola corta, y los machos son azul brillante encima y amarillo en el vientre, con un “gorro” amarillo relativamente pequeño. Afortunadamente, la población de esta pequeña ave parece ser estable, y gracias a su rango extremadamente extenso en gran parte de Sudamérica, tampoco está amenazada. - Canon PowerShot SX50 HS ƒ/6.5 | 1/160s | 215mm | ISO-250 - Follow us! | Síguenos! www.facebook.com/hillstarbirding www.instagram.com/hillstar_birding - References | Fuentes: Cornell Lab of Ornithology National Audubon Society BirdLife International Princeton Birds and Natural History Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive Corbidi - Centro de Ornitología y Biodiversidad Arkive - #birds #birding #birdwatching #nature #wildlife #animals #birdphotography #naturephotography #birdlovers #birdphotobooth #birdsofperu #peru #wildlifephotography #conservation #animalphotography #naturelover #wild #visitperu #liveauthentic #exploretocreate #adventureculture #wonderoutdoors #YTúQuéPlanes #PeruTheRichestCountry (at Tarapoto) https://www.instagram.com/p/BrFb2CQAXz2/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=1tizf72imbmh3

#birds#birding#birdwatching#nature#wildlife#animals#birdphotography#naturephotography#birdlovers#birdphotobooth#birdsofperu#peru#wildlifephotography#conservation#animalphotography#naturelover#wild#visitperu#liveauthentic#exploretocreate#adventureculture#wonderoutdoors#ytúquéplanes#perutherichestcountry

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Scottish Highlands, the Appalachians, and the Atlas are the same mountain range, once connected as the Central Pangean Mountains

The Central Pangean Mountains were a great mountain chain in the middle part of the supercontinent Pangaea that stretches across the continent from northeast to southwest during the Carboniferous, Permian Triassic periods. The ridge was formed as a consequence of a collision between the supercontinents Laurussia and Gondwana during the formation of Pangaea. It was similar to the present Himalayas at its highest elevation during the beginning of the Permian period.

It’s hard to imagine now that once upon a time that the Scottish Highlands, the Appalachians, the Ouachita Mountains, and the Little Atlas of Morocco are the same mountain range, once connected as the Central Pangean Mountains.

During the Permian period, the Central Pangean were subjected to significant physical weathering, decreasing the peaks and forming many deep intermontane plains. By the Middle Triassic, the mountain sierras had been considerably reduced in size. By the beginning of the Jurassic period (200 mln years ago), the Pangean chain in Western Europe disappeared to some highland regions separated by deep marine basins.

1 note

·

View note