#karl von hapsburg

Text

#my post#uniform#emperor#king#archduke#king of hungary#emperor of austria#karl i#charles i#hapsburgs#hapsburg#blessed karl of austria#army#austro-hungarian#austro-hungarian army#miltary#karl von hapsburg#austro-hungarian empire#catholic#roman catholic

1 note

·

View note

Text

instagram

Episode Thirty-Eight: Charles The Bewitched & Inbred Royals Photodump

Photo # 1 : The Spanish Hapsburgs Family Tree. Notice how the branches turn inwards instead of outward.

Photo #2: King Charles V’s Hapsburg Jaw depicted in painting and sculpture.

Photo #3: King Charles II of Spain’s Hapsburg jaw featured in a portrait.

Photo #4: “El Hechezado” suffered many illnesses and was unable to speak until the age of 4, and was carried everywhere until he was 8 years old to reduce strain on his body.

Photo #5: Jane Sharp’s “The Midwife’s Companion” published in 1671 is an insight into popular 17th century fertility methods and beliefs about the female reproductive system during the 1600’s.

Photo #6: A 17th century depiction of what pregnancy consisted of from Jane Sharp’s book.

Photo #7: Insert of “ The Midwife’s Companion”.

Photo #8: Insert 2 from “ The Midwife’s Companion” reveals how twins might exist in the womb.

Photo #9: Relatives of Charles II and Phillip V of the Spanish Hapsburgs, Karl Von Hapsburg and his wife Francesca Von Hapsburg are still alive today.

#Charles The Bewitched & Inbred Royals#Let's Get Haunted#Hapsburgs Family Tree#Spanish Royalty#Jane Sharp#Episode 38#Instagram

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

we are being prevented from establishing diplomatic relations with karl von hapsburg because of the authoritarian imposition of the One Austria Policy

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Defence of Vienna against the Turks 1683

by Karl von Blaas

#siege of vienna#battle of vienna#vienna#the holy roman empire#holy roman empire#ottoman empire#hapsburg#hapsburgs#europe#european#christianity#ottomans#austria#karl von blaas#artist#habsburg monarchy#habsburg empire#habsburg#siege

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

Karl von Hapsburg also commented on the Oprah interview: "The two are so far behind in the line of succession, if not to say practically non-existent, that they play no role at all in this regard. And for that reason alone, such a globally broadcast appearance seems completely inappropriate to me. If there are actually problems or dissonances in the private sphere, then it would be more appropriate to discuss and clarify such things specifically in a private setting."

I couldn't remember his name yesterday. Thank you.

34 notes

·

View notes

Conversation

APH Austria: Oh no! This is dreadful! The pretender to the Austrian-Hungarian throne, Karl von Hapsburg, has tested positive for the coronavirus...

APH Prussia: The first time a Hapsburg has gotten any new DNA in their system in generations.

#source: twitter#aph prussia#aph austria#hws austria#hws prussia#hetalia#aph#shit aph prussia says#hetalia incorrect quotes#srsly tho Its a pandemic here#and im freaking out#:( coping with memes#its bad#quco

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Things I learned today

The Hapsburgs are still a political force in Europe.

Their patriarch, Karl Von Hapsburg, still claims to be the rightful ruler of Austria, Hungary, Bohemia, and Croatia.

He now has coronavirus.

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The russeted and gilt child’s half harness of Archduke Ferdinand Karl von Hapsburg, Innsbruck, Austria, ca. 1641, housed at the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

#armor#armour#child#half armor#russet#europe#european#austrian#austria#innsbruck#hre#holy roman empire#early modern#khm#vienna#art#history

96 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Heir to Napoleon Bonaparte is set to marry the great-grand-daughter of Austria's last emperor.

More than 200 years after Napoleon married the Archduchess of Austria, the former Imperial House of France and the House of Hapsburg will unite once again, when Bonaparte's heir - who carries on the family name - marries the great-grand-daughter of Austria’s last emperor.

London-based private equity manager Jean-Christophe Napoleon Bonaparte, is the great-great-great nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte I, Emperor of France.

He's set to marry Countess Olympia von und zu Arco-Zinnerberg, the great-granddaughter of Karl I, after proposing with a ring set with a 40 carat diamond taken from the crown of Napoleon III's wife.

The pair are distantly related as Countess Olympia is the great-great-great niece of Napoleon's wife, Archduchess Marie-Louise of Austria.

The union has echoes of Napoleon's marriage to Archduchess Marie-Louise of Austria in 1810, which was designed to secure an ally in his war against Britain and Russia and bring conflict between the two countries to a halt.

However, the pair say that their wedding in October 2019 is a love match, and not designed to further any political ambitions.

He said: 'It's a story of love rather than a nod to history. When I met Olympia, I plunged into her eyes and not into her family tree. Afterwards we were able to smile at this historical coincidence.'

Bonaparte, who is fluent in French, English, and Spanish, has been working for Blackstone group, the private equity firm, in London since graduating Harvard Business school in 2017.

The couple plan to stay in London after the wedding.

(source: Dailymail)

86 notes

·

View notes

Link

More than 200 years after Napoleon married the Archduchess of Austria, the former Imperial House of France and the House of Hapsburg will unite once again, when Bonaparte's heir - who carries on the family name - marries the great-grand-daughter of Austria’s last emperor.

London-based private equity manager Jean-Christophe Napoleon Bonaparte, 32, is the great-great-great nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte I, Emperor of France.

He's set to marry Countess Olympia von und zu Arco-Zinnerberg, 31, the great-granddaughter of Karl I, after proposing with a ring set with a 40 carat diamond taken from the crown of Napoleon III's wife.

#daily mail#bonaparte#hapsburg#jean-christophe napoleon bonaparte#countess olympia von und zu arco-zinnerberg

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

You've talked before about the "protuberant eyes of the Hanovers". That made me major book vibes (think about the Stark look or Lannister look), and it made me curious; are there any distinct phyisical traits in real-life monarchies?

Ohhh boy let me tell you about perhaps the most infamous of all royal genetic markers: the Hapsburg jaw.

The House of Hapsburg (or Habsburg, as its original castle was called) needs virtually no introduction. Once a minor noble family from present-day Switzerland, the family ascended in power in the medieval period until it controlled the Duchy of Austria and one of its scions, Frederick III, was elected Holy Roman Emperor. Through the marriage of Philip, Duke of Burgundy to Juana of Castile, the Hapsburg empire expanded greatly, with the family controlling both its territories in the Holy Roman Empire and the territories of the recently united Spain (this is why the arms of their son Charles V were so complicated). The senior branch of the family ruled Spain until the death of Charles II in 1700, while the junior branch ruled the Holy Roman Empire until 1780 (with the death of Maria Theresa, the last of that male line, though the family continued to style itself as “Hapsburg” thereafter, even down to the modern pretender Karl von Habsburg).

Unrelated to their imperial ambitions, the Hapsburgs also tended to have very pronounced, Jay Leno-esque lower jaws - the result of a condition known as “mandibular prognathism”. No one is quite certain when the trait came into the family: popular legend has it that the Polish noblewoman Cymburga of Masovia, the mother of Holy Roman Emperor Frederick III, brought the trait into the family, but it can also be seen in more distant ancestors as well. Certainly, however, by the sixteenth century the Hapsburg jaw (or Hapsburg lip) was pretty evident in a number of members of the family.

So, for example, here’s Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain:

Here’s his son, Philip II of Spain:

Here’s his daughter-in-law, Margaret of Austria (who was also a granddaughter of Charles V’s younger brother Ferdinand I, Holy Roman Emperor):

Here’s Philip II’s grandson, Philip IV:

And Philip IV’s younger brother, the Infante Charles:

It got really bad in Philip IV’s only surviving son, Charles II (who, I can’t emphasize enough, was more inbred than if his parents had actually been siblings):

(Poor Charles’ case was so bad that he had great difficulty speaking and chewing, as his overlarge tongue could not fit completely in his mouth)

There was also Ferdinand I’s grandson Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor:

And another grandson of Ferdinand I, Archduke Ernest:

As well as Ferdinand II’s grandson Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperor:

It continued even into more modern Hapsburg descendants, like Ferdinand I, Austrian Emperor:

(To continue the inbreeding, Ferdinand I’s parents were double first cousins: his paternal grandfather, Leopold II, Holy Roman Emperor, was the brother of his maternal grandmother, Maria Carolina of Austria, while his maternal grandfather, Ferdinand I of Naples and Sicily, was the brother of his paternal grandmother, Maria Luisa of Spain. Poor Ferdinand suffered from hydrocephalus and severe epilepsy, as well as several neurological problems that made learning speech difficult for him.)

And one of Ferdinand I’s first cousins, Archduke Albert:

Even King Alfonso XIII of Spain (whose mother, Maria Christina of Austria, was Archduke Albert’s niece):

These are just some of the many Hapsburgs, and of course the trait did not always appear (even as inbred as many of the Hapsburgs were, there were non-Hapsburg marriages among them). Of course, that’s true for the families of Westeros as well: the Starks might be long-faced, grey-eyed, and dark-haired, but only one of the Stark-Tully children ended up with those features; there were plenty of Targaryen descendants who did not show the family’s famous silvery hair and purple eyes; and while Lannisters are often blond-haired and green eyes, there’s every probability (h/t @joannalannister) that red-haired Dancy the prostitute is the daughter of a Lannister.

107 notes

·

View notes

Link

The last ruler of the Austro-Hungarian Empire moved a little closer to Roman Catholic sainthood Thursday, thanks to a Baptist woman from Kissimmee who claims the monarch's intercession saved her from metastatic breast cancer. Emperor Karl von Habsburg, beatified by Pope John Paul II in 2004, needs a Vatican-approved miracle to be canonized, the final step to sainthood. The Central Florida woman claims she was cured of terminal cancer after she prayed to Karl of Austria to intercede with Jesus on her behalf.

The Kissimmee woman, who remains a devout Baptist, attended a Mass and ceremony at St. James Cathedral Chapel on Thursday, but she would not be identified or interviewed.

0 notes

Photo

Coronavirus Hits First Royal: Karl von Hapsburg, Archduke of Austria Diagnosed With COVID-19 The Archduke of Austria, Karl von Habsburg, is the first royal in the world to find himself facing quarantine after he was diagnosed with the novel Coronavirus (Covid-19).

0 notes

Photo

THE RING OF POWER

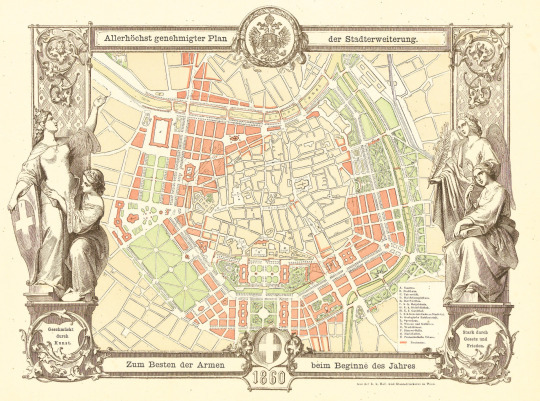

On 25 December 1857, a decree of Kaiser Franz-Josef I was published in the Wiener Zeitung announcing a civil-engineering project of unprecedented scale:

Es ist Mein Wille, daß die Erweiterung der inneren Stadt Wien mit Rücksicht auf eine entsprechende Verbindung derselben mit den Vorstädten ehemöglichst in Angriff genommen und hiebei auch auf die Regulirung und Verschönerung Meiner Residenz- und Reichshauptstadt Bedacht genommen werde. Zu diesem Ende bewillige Ich die Auflassung der Umwallung und Fortifikationen der inneren Stadt, so wie der Gräben um dieselbe … Auf die Herstellung öffentlicher Gebäude, namentlich eines neuen General-Kommando’s, einer Stadt-Kommandantur, eines Opernhauses, eines Reichsarchives, einer Bibliothek, eines Stadthauses, dann der nöthigen Gebäude für Museen und Gallerien ist Bedacht zu nehmen und sind die hiezu zu bestimmenden Plätze unter genauer Angabe des Flächenausmaßes zu bezeichnen.

The goal of this massive act of demolition and displacement was the expansion of the city beyond its historical boundaries and the assimilation of the outer suburbs to the city center. On the site of the former medieval walls, a road would be constructed:

Sonst soll aber im Anschlusse an den Quai längs dem Donaukanal rings um die innere Stadt ein Gürtel in der Breite von mindestens vierzig (40) Klafter, bestehend aus einer Fahrstraße mit Fuß- und Reitwegen zu beiden Seiten, auf dem Glacisgrunde in der Art angelegt werden, daß dieser Gürtel eine angemessene Einfassung von Gebäuden abwechselnd mit freien zu Gartenanlagen bestimmten Plätzen erhalte.

The circuit of grand boulevards, or Ringstraße, was officially opened by the Kaiser in May, 1865.

Stadtplan Wien, 1860.

The collection of public amenities, gardens, ministries and aristocratic residences erected along the Ringstraße transformed the provincial, medieval city into a modern metropolis on par with Paris and London. The reconfigured capital was also intended to reassert the authority of the Hapsburg dynasty in Eastern Europe and to forestall urban uprisings in the wake of the 1848 revolutions.

The major buildings on the Ringstraße were designed in historical-revival styles deemed appropriate to their function. Thus, the newly-founded Parlement’s democratic purpose is expressed in a Neo-Athenian, Ionic vocabulary, balanced by the Imperial Roman of the Neue Burg.

Theophil Hansen, Parlament, 1874/84, Dr-Karl-Lueger Ring.

The only religious structure on the ring, the Votivkirche, is Neo-Gothic. The Rathaus, funded by the the city fathers of Vienna replicates the burgerlich late Gothic style of Flemish Town Halls.

Heinrich von Ferstel, Votivkirche, 1855/79, Schottenting.

Friedrich von Schmidt, Rathaus, 1872/83, Dr-Karl-Lueger Ring.

The Renaissance and Baroque are represented by the poorly-received Staatsoper (which was likened to a gigantc coffin), the Burgtheater (largely destroyed in World War II.

Gottfried Semper and Karl Freiherr von Hasenauer, Burgtheater, 1888, Dr-Karl-Lueger Ring; Eduard van der Nüll, August Sicard von Sicardsburg, Staatsoper, 1869, Opernring.

subsequently rebuilt) and the vast Kunsthistorisches and Naturhistorisches Museen, erected to preserve and display the spectacular Hapsburg collections of art and natural specimens primarily amassed in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Museenplatz, Hofburg on the Burgring.

The architectural survey concludes with the modernist Postsparkasse (1904/06) designed by Secession architect Otto Wagner.

Otto Wagner, Postsparkasse, 1904/06

The planners of the Ring brilliantly deployed a multiplicity of architectural vernaculars to articulate a single, totalizing ideological message that proclaimed the supra-national and transcendent nature of the authority vested in the Hapsburg emperor and located in Vienna.

By 1900, however, the eclectic historicism of the Ringstraße had begun to look dated, even meretritious, and its main practitioners, including Wagner, had repudiated it. The Secession artists viewed it as an incoherent collection of kitsch, and the multiplicity of styles as symptoms of an artistic identity crisis that mirrored the schisms within the sprawling polyglot Austro-Hungarian empire.

#ringstraße#wien#vienna#austro-hungarian empire#kaiser franz josef#otto wagner#historical revival styles#staatsoper

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Man from Red Vienna

December 21, 2017 Issue

Karl Polanyi: A Life on the Left

by Gareth Dale Columbia University Press, 381 pp., $40.00; $27.00 (paper)

What a splendid era this was going to be, with one remaining superpower spreading capitalism and liberal democracy around the world. Instead, democracy and capitalism seem increasingly incompatible. Global capitalism has escaped the bounds of the postwar mixed economy that had reconciled dynamism with security through the regulation of finance, the empowerment of labor, a welfare state, and elements of public ownership. Wealth has crowded out citizenship, producing greater concentration of both income and influence, as well as loss of faith in democracy. The result is an economy of extreme inequality and instability, organized less for the many than for the few.

Not surprisingly, the many have reacted. To the chagrin of those who look to the democratic left to restrain markets, the reaction is mostly right-wing populist. And “populist” understates the nature of this reaction, whose nationalist rhetoric, principles, and practices border on neofascism. An increased flow of migrants, another feature of globalism, has compounded the anger of economically stressed locals who want to Make America (France, Norway, Hungary, Finland…) Great Again. This is occurring not just in weakly democratic nations such as Poland and Turkey, but in the established democracies—Britain, America, France, even social-democratic Scandinavia.

We have been here before. During the period between the two world wars, free-market liberals governing Britain, France, and the US tried to restore the pre–World War I laissez-faire system. They resurrected the gold standard and put war debts and reparations ahead of economic recovery. It was an era of free trade and rampant speculation, with no controls on private capital. The result was a decade of economic insecurity ending in depression, a weakening of parliamentary democracy, and fascist backlash. Right up until the German election of July 1932, when the Nazis became the largest party in the Reichstag, the pre-Hitler governing coalition was practicing the economic austerity commended by Germany’s creditors.

The great prophet of how market forces taken to an extreme destroy both democracy and a functioning economy was not Karl Marx but Karl Polanyi. Marx expected the crisis of capitalism to end in universal worker revolt and communism. Polanyi, with nearly a century more history to draw on, appreciated that the greater likelihood was fascism.

As Polanyi demonstrated in his masterwork The Great Transformation (1944), when markets become “dis-embedded” from their societies and create severe social dislocations, people eventually revolt. Polanyi saw the catastrophe of World War I, the interwar period, the Great Depression, fascism, and World War II as the logical culmination of market forces overwhelming society—“the utopian endeavor of economic liberalism to set up a self-regulating market system” that began in nineteenth-century England. This was a deliberate choice, he insisted, not a reversion to a natural economic state. Market society, Polanyi persuasively demonstrated, could only exist because of deliberate government action defining property rights, terms of labor, trade, and finance. “Laissez faire,” he impishly wrote, “was planned.”

Polanyi believed that the only way politically to temper the destructive influence of organized capital and its ultra-market ideology was with highly mobilized, shrewd, and sophisticated worker movements. He concluded this not from Marxist economic theory but from close observation of interwar Europe’s most successful experiment in municipal socialism: Red Vienna, where he worked as an economic journalist in the 1920s. And for a time in the post–World War II era, the entire West had an egalitarian form of capitalism built on the strength of the democratic state and underpinned by strong labor movements. But since the era of Thatcher and Reagan that countervailing power has been crushed, with predictable results.

In The Great Transformation, Polanyi emphasized that the core imperatives of nineteenth-century classical liberalism were free trade, the idea that labor had to “find its price on the market,” and enforcement of the gold standard. Today’s equivalents are uncannily similar. We have an ever more intense push for deregulated trade, the better to destroy the remnants of managed capitalism; and the dismantling of what remains of labor market safeguards to increase profits for multinational corporations. In place of the gold standard—whose nineteenth-century function was to force nations to put “sound money” and the interests of bondholders ahead of real economic well-being—we have austerity policies enforced by the European Commission, the International Monetary Fund, and German Chancellor Angela Merkel, with the American Federal Reserve tightening credit at the first signs of inflation.

This unholy trinity of economic policies that Polanyi identified is not working any more now than it did in the 1920s. They are practical failures, as economics, as social policy, and as politics. Polanyi’s historical analysis, in both earlier writings and The Great Transformation, has been vindicated three times, first by the events that culminated in World War II, then by the temporary containment of laissez-faire with resurgent democratic prosperity during the postwar boom, and now again by the restoration of primal economic liberalism and neofascist reaction to it. This should be the right sort of Polanyi moment; instead it is the wrong sort.

Gareth Dale’s intellectual biography, Karl Polanyi: A Life on the Left, does a fine job of exploring the man, his work, and the political and intellectual setting in which he developed. This is not the first Polanyi biography, but it is the most comprehensive. Dale, a political scientist who teaches at Brunel University in London, also wrote an earlier book, Karl Polanyi: The Limits of the Market (2010), on his economics.

Polanyi was born in 1886 in Vienna to an illustrious Jewish family. His father, Mihály Pollacsek, came from the Carpathian region of the Hapsburg Empire and acquired a Swiss engineering degree. He was a contractor for the empire’s growing rail system. In the late 1880s, Mihály moved the family to Budapest, according to the Polanyi Archive. He magyarized the children’s family name to Polanyi in 1904, the same year Karl began studies at the University of Budapest, though he kept his own surname. Karl’s mother, Cecile, the well-educated daughter of a Vilna rabbi, was a pioneering feminist. She founded a women’s college in 1912, wrote for German-language periodicals in Budapest and Berlin, and presided over one of Budapest’s literary salons.

At home, German and Hungarian were spoken (along with French “at table”), and English was learned, Dale reports. The five Polanyi children also studied Greek and Latin. In the quarter-century before World War I, Budapest was an oasis of liberal tolerance. As in Vienna, Berlin, and Prague, a large proportion of the professional and cultural elite consisted of assimilated Jews. In the mid-1890s, Dale notes, “the Jewish faith was accorded the same privileges as the Christian denominations, and Jewish representatives were accorded seats in the upper house of parliament.”

Drawing on interviews and correspondence as well as published writings, Dale vividly evokes the era. Polanyi’s milieu in Budapest, known as the Great Generation, included activists and social theorists such as his mentor, Oscar Jaszi; Karl Mannheim; the Marxist Georg Lukács; Karl’s younger brother and ideological sparring partner, the libertarian Michael Polanyi; the physicists Leo Szilard and Edward Teller; the mathematician John von Neumann; and the composers Béla Bartók and Zoltán Kodály, among many others. In this hothouse Polanyi thrived, attending the Minta Gymnasium, one of the city’s best, and then the University of Budapest. He was expelled in 1907 following a shoving match in which anti-Semitic right-wingers disrupted a lecture by a popular leftist professor, Gyula Pikler. He had to finish his doctor of law degree in 1908 at the provincial University of Kolozsvár (today Cluj in Romania). There, he was a founder of the left-humanist Galilei Circle and later served on the editorial board of its journal.

Polanyi became a leading member of Jaszi’s political party, the Radicals, and was named its general secretary in 1918. He was drawn to the Christian socialism of Robert Owen and Richard Tawney and the guild socialism of G.D.H. Cole. He mused about a fusion of Marxism and Christianity. Polanyi is best classified as a left-wing social democrat—but a lifelong skeptic of the possibility that a capitalist society would ever tolerate a hybrid economic system.

After World War I broke out, Polanyi enlisted as a cavalry officer. When he came home in late 1917, suffering from malnutrition, depression, and typhus, Budapest was in the throes of a chaotic conflict between the left and the right. In 1918 the Hungarian government made a separate peace with the Allies, breaking with Vienna and hoping to create a liberal republic. Events in the streets overtook parliamentary jockeying, and the Communist leader Béla Kun proclaimed what turned out to be a short-lived Hungarian Soviet Republic.

Polanyi decamped for Vienna, both to recover his health and to get off the political front lines. There he found his calling as a high-level economics journalist and the love of his life, Ilona Duczynska, a Polish-born radical well to his left. Their daughter, Kari, born in 1923, recalls, as a preteen, clipping marked-up newspaper articles in three languages for her father. At age ninety-four, she continues to help direct the Polanyi Archive in Montreal.

Central Europe’s equivalent of The Economist, the weekly Österreichische Volkswirt, hired Polanyi in 1924 as a writer on international affairs. He continued his quest for a feasible socialism, engaging with others on the left and challenging the right in ongoing arguments with the free-market theorist Ludwig von Mises. The debates, published in agonizing detail, turned on whether a socialist economy was capable of efficient pricing. Mises insisted it was not. Polanyi argued that a decentralized form of worker-led socialism could price necessities with good-enough accuracy. He ultimately concluded, Dale recounts, that these abstruse technical arguments had been a waste of his time.1

A practical answer to the debate with Mises was playing out in Red Vienna. Well-mobilized workers kept socialist municipal governments in power for nearly sixteen years after World War I. Gas, water, and electricity were provided by the government, which also built working-class housing financed by taxes on the rich—including a tax on servants. There were family allowances for parents and municipal unemployment insurance for the trade unions. None of this undermined the efficiency of Austria’s private economy, which was far more endangered by the hapless policies of economic austerity that were criticized by Polanyi. After 1927, unemployment relentlessly increased and wages fell, which helped bring to power in 1932–1933 an Austrofascist government.

To Polanyi, Red Vienna was as important for its politics as for its economics. The perverse policies of Dickensian England reflected the political weakness of its working class, but Red Vienna was an emblem of the strength of its working class. “While [English poor-law reform] caused a veritable disaster of the common people,” he wrote, “Vienna achieved one of the most spectacular triumphs of Western history.” But as Polanyi appreciated, an island of municipal socialism could not survive larger market turbulence and rising fascism.

In 1933, with homegrown fascists running the government, Polanyi left Vienna for London. There, with the help of Cole and Tawney, he eventually found work in an extension program sponsored by Oxford University, known as the Workers’ Educational Association. He taught, among other subjects, English industrial history. His original research for these lectures formed the first drafts of The Great Transformation.

His mentor Oscar Jaszi was also now in exile and teaching at Oberlin. To supplement his meager adjunct pay, Polanyi was able to put together lecture tours to colleges in the United States. He found Roosevelt’s America a hopeful counterpoint to Europe. After war broke out, one of those lecture trips evolved into a three-year appointment at Bennington College, where he completed his book.

The timing of publication was auspicious. The year 1944 included the Bretton Woods Agreement, Roosevelt’s call for an Economic Bill of Rights, and Lord Beverage’s epic blueprint Full Employment in a Free Society. What these had in common with Polanyi’s work was a conviction that an excessively free market should never again lead to human misery ending in fascism.

Yet Polanyi’s book was initially met with resounding silence. This, I think, was the result of two factors. First, Polanyi belonged to no academic discipline and was essentially self-taught. Dale writes that when he was finally offered a job teaching economic history at Columbia in 1947, “the sociologists saw him as an economist, while the economists thought the reverse.” Midcentury America was also a period when political economy, institutionalism, the history of economic thought, and economic history were going into a period of eclipse, in favor of formalistic modeling. Polanyi’s was not a hypothesis that could be tested.

Second and more important, Polanyi’s ideological adversaries enjoyed subsidy and promotion while he had only the power of his ideas. Mises, like Polanyi, had no academic credentials. But he conducted an influential private seminar from his post as secretary of the Austrian Chamber of Commerce. The seminar developed the ultra-laissez-faire Austrian school of economics. Mises’s prime student was Friedrich Hayek. As a laissez-faire theorist financed by organized business, Mises anticipated the Heritage Foundation by half a century.

Hayek later contended in The Road to Serfdom that well-intentioned state efforts to temper markets would end in despotism. But there is no case of social democracy drifting into dictatorship. History sided with Polanyi, demonstrating that an unrestrained free market leads to democratic breakdown. Yet Hayek ended up with a chair at the London School of Economics, which was founded by Fabians; the “Austrian School” got dignified as a formal school of libertarian economics; and Hayek later won the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences. The Road to Serfdom, also published in 1944, was a best seller, serialized in Reader’s Digest. Polanyi’s Great Transformation sold just 1,701 copies in 1944 and 1945.

When The Great Transformation appeared in 1944, the review in The New York Times was withering. The reviewer, John Chamberlain, wrote, “This beautifully written essay in the revaluation of a hundred and fifty years of history adds up to a subtle appeal for a new feudalism, a new slavery, a new status of economy that will tie men to their places of abode and their jobs.” If that sounds curiously like Hayek, the same Chamberlain had just written the effusive foreword to The Road to Serfdom. Such is the political economy of influence.

Yet Polanyi’s book refused to fade away. In 1982, his concepts were the centerpiece of an influential article by the international relations scholar John Gerard Ruggie, who termed the postwar economic order of 1944 “embedded liberalism.” The Bretton Woods system, Ruggie wrote, reconciled state with market by “re-embedding” the liberal economy in society via democratic politics.2 The Danish sociologist Gøsta Esping-Andersen, a major historian of social democracy, used the Polanyian concept “decommodification” in an important book, The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism (1990), to describe how social democrats contained and complemented the market.3

Other scholars who have valued Polanyi’s insights include the political historians Ira Katznelson, Jacob Hacker, and Richard Valelly, the late sociologist Daniel Bell, and the economists Joseph Stiglitz, Dani Rodrik, and Herman Daly. On the other hand, thinkers who seem quintessentially Polanyian in their concern about markets invading nonmarket realms, such as Michael Walzer, John Kenneth Galbraith, Albert Hirschman, and the Nobel laureate Elinor Ostrom, don’t invoke him at all. This is the price one pays for being, in Hirschman’s self-description, a trespasser.

Having been exiled three times—from Budapest to Vienna, from Vienna to London, and later to New York—Polanyi had to move yet again when the US authorities would not grant Ilona a visa, citing her onetime membership in the Communist Party in the 1920s. They ended up in a suburb of Toronto, from which Polanyi commuted to Columbia until his retirement in the mid-1950s.

Though his enthusiasts tend to focus only on The Great Transformation, Dale’s book is valuable for his discussion of Polanyi after 1944. He lived for another twenty years, working on what was then known as primitive economic systems, which gave him yet another basis to demonstrate that the free market is no natural condition, and that markets in fact do not have to overwhelm the rest of society. On the contrary, many early cultures effectively blended market and nonmarket forms of exchange. His subjects included the slave trade of Dahomey and the economy of ancient Athens, which “demonstrated that elements of redistribution, reciprocity, and market exchange could be effectively fused into ‘an organic whole.’” Dale writes, “For Polanyi, democratic Athens was truly antiquity’s forerunner to Red Vienna.” Athens, of course, was far from socialist, but its precapitalist economy did blend market and nonmarket forms of income.

Dale also addresses Polanyi’s views on the escalating cold war and on the mixed economy of the postwar era that many now view as a golden age. The trente glorieuses, combining egalitarian capitalism and restored democracy, should have felt to him like an affirmation. But Polanyi, having lived through two wars, the destruction of socialist Vienna, the loss of close family members to the Nazis, four separate exiles, and long separations from Ilona, was not so easily convinced. While he admired Roosevelt, he considered the British Labour government of 1945 a sellout—a welfare state atop a still capitalist system.

Half a century later, that concern proved all too accurate. Others saw the Bretton Woods system as an elegant way of restarting trade while creating shelter for each member nation to run full-employment economies, but Polanyi viewed it as an extension of the sway of capital. That may also have been prescient. By the 1980s, the IMF and the World Bank had been turned into enforcers of austerity, the opposite of what was intended by their architect, John Maynard Keynes. He blamed the cold war mostly on the Allies, praising Henry Wallace’s view that the West could have reached an accommodation with Stalin.

Dale makes no excuses for Polanyi’s blind spot about the Soviet Union. At various points in the 1920s and 1930s, he notes, Polanyi gave Stalin something of a pass, even blaming the 1940 Molotov–Ribbentrop pact on Whitehall’s anti-Sovietism. And he was sanguine about the intentions of the Russians in the immediate postwar period. As a member of the émigré Hungarian Council in London, he broke with its other leaders over whether the Red Army should be welcomed as a harbinger of democratic socialism. The Soviet liberation of Eastern Europe, Polanyi insisted, would bring “a form of representative government based on political parties.”

Having been proven badly wrong, Polanyi cheered the abortive Hungarian revolution of 1956, yet after it was crushed by Soviet tanks he also found reasons for hope in the mildly reformist “goulash communism” that followed. This was naive, yet not totally misplaced. Though Polanyi was no Marxist, there was enough openness in Hungary that in 1963, a year before his death and well before the Berlin Wall came down, he was invited to lecture at the University of Budapest, his first visit home in four decades.

On the centennial of his birth in 1986, Kari Polanyi-Levitt organized a symposium in his honor in Budapest. The conference volume makes a superb companion to the Dale biography.4 The twenty-five short articles are written by a mix of writers based in the West and several from what was still Communist Hungary—where Polanyi was widely read. The writing is surprisingly exploratory and nondogmatic. Even so, when her turn came to speak, Polanyi-Levitt took a moment to plead: “If I may be permitted one more request to the Hungarian Academy of Sciences…it is that The Great Transformation be made available to Hungarian readers in the Hungarian language.” This was finally done in 1990. Like many in the West, the Communist regime in Budapest was not quite sure what to do with Polanyi.

Today, after a democratic interlude, Hungary is a center of ultra-nationalist autocracy. Misguided policies of financial license played their usual part. After the 2008 financial collapse, Hungarian unemployment steadily rose, from under 8 percent before the crash to almost 12 percent by early 2010. And in the 2010 election, the far-right Fidesz Party swept a left-wing government out of power, winning more than two thirds of the parliamentary seats, which made possible the “illiberal democracy” of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. It was one more echo, and one more vindication, that Polanyi didn’t need.

What, finally, are we to make of Karl Polanyi? And what lessons might he offer for the present moment? As even his champions admit, some of his details were off. Earlier friendly critics, Fred Block and Margaret Somers, point out that his account of late-eighteenth-century Britain exaggerates the ubiquity of poor relief. His famous case of the poor law of Speenhamland of 1795, whose public assistance protected the poor from the early perturbations of capitalism, overstated its application in England as a whole. Yet his account of the liberal reform of the poor laws in the 1830s was spot on. The intent and effect were to push people off of relief and force workers to take jobs at the lowest going wage.

One might also argue that the failure of liberal democracy to take hold in Central Europe in the nineteenth century, which paved the way for right-wing nationalism, had more complex causes than the spread of economic liberalism. Yet Polanyi was correct to observe that it was the failed attempt to universalize market liberalism after World War I that left the democracies weak, divided, and incapable of resisting fascism until the outbreak of war. Neville Chamberlain is best remembered for his capitulation to Hitler at Munich in 1938. But at the nadir of the Great Depression in April 1933, when Hitler was consolidating power in Berlin and Chamberlain was serving as Tory chancellor of the exchequer in London, he said this: “We are free from that fear which besets so many less fortunately placed, the fear that things are going to get worse. We owe our freedom from that fear to the fact that we have balanced our budget.” Such was the perverse conventional wisdom, then and now. That line should be chiseled on some monument to Polanyi.

A recent article by three Danish political scientists in the Journal of Democracy questions whether it was reasonable to attribute the surge of fascism in the 1920s and 1930s to the long arc of laissez-faire and economic collapse.5 They reported that the well-established democracies of northwest Europe and the former British colonies Canada, the US, Australia, and New Zealand “were virtually immune to the repeated crises of the interwar period,” while the newer and more fragile democracies of southern, central, and eastern Europe succumbed. Indeed, fascists briefly assumed power in northwest Europe only through invasion and occupation. Yet that observation makes Polanyi a more prophetic and ominous voice for our own time. Today in much of Europe, far-right parties are now the second or third largest.

In sum, Polanyi got some details wrong, but he got the big picture right. Democracy cannot survive an excessively free market; and containing the market is the task of politics. To ignore that is to court fascism. Polanyi wrote that fascism solved the problem of the rampant market by destroying democracy. But unlike the fascists of the interwar period, today’s far-right leaders are not even bothering to contain market turbulence or to provide decent jobs through public works. Brexit, a spasm of anger by the dispossessed, will do nothing positive for the British working class; and Donald Trump’s program is a mash-up of nationalist rhetoric and even deeper government alliance with predatory capitalism. Discontent may yet go elsewhere. Assuming democracy holds, there could be a countermobilization more in the spirit of Polanyi’s feasible socialism. The pessimistic Polanyi would say that capitalism has won and democracy has lost. The optimist in him would look to resurgent popular politics.

http://www.nybooks.com/articles/2017/12/21/karl-polanyi-man-from-red-vienna/

@catcomaprada

0 notes

Photo

01-15 MARRIAGE OF KARL HAPSBURG & FRANCESCA VON THYSSEN (Photo by Reuter Raymond/Sygma via Getty Images) #mariazell http://dlvr.it/N6XT4L

0 notes