#kathleen warren

Text

San Diego comic con I think 2012. Starting on the left Peter David, Caroline Spector, George RR Martin, me, Warren Spector. Photo taker Chris Paolini.

#peter david#Caroline Spector#george rr martin#Kathleen O’Shea David#warren spector#christopher paolini#authors drinking#San Diego comicon

6 notes

·

View notes

Link

So, this episode is packed full of all the things. IN Krysta's Corner she discusses her first oratory AND her Halloween Costume and Mom chimes in with hers as well. Afterwards, we get into this week's topic, the house whose former address was 112 Ocean Avenue in Amityville, New York. We discuss it's construction, as well as debunk a few beliefs that taint the house's reputation to today. Then we discuss the DeFeo murders that happened in the house as well as the haunting of the Lutzes as they took possession of the house one year later. We get real spooky in this true crime and paranormal episode of the Family Plot Podcast!

#'butch'#alison#amityville#dawn#defeo#ed#george#haunting#john#junior#kathleen#lorraine#louise#lutz#marc#marlin#murder#rifle#ronald#warren

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"OUR MUTUAL FRIEND" (1976) Review

"OUR MUTUAL FRIEND" (1976) Review

I have a curious history with the 1998 adaptation of Charles Dickens' 1864-65 novel, "Our Mutual Friend". I had a lukewarm reaction to it when I first saw it. Following two re-watches of the miniseries, I became a major fan of it. So, when I discovered there had been an earlier adaptation of the novel, I did not hesitate to watch it. My efforts to view the 1976 miniseries, "OUR MUTUAL FRIEND" proved to be difficult, due more to availability reasons. But I finally managed to achieve it in the end.

Whether you are familiar with Dickens' tale or not, "OUR MUTUAL FRIEND" centered around the "death" of the heir to a fortune inherited from his father, a former collector from London's rubbish. The story begins with a solicitor named Mortimer Lightwood, who narrates the circumstances of the death of his client, a former dustman named Mr. Harmon, who collected London's rubbish, to his aunt and other guests at a society dinner. The terms of Old Harmon's will stipulated that his fortune should go to his estranged son John, who had returned to Britain after years spent abroad. John can inherit his father's fortune on the condition that he marry a woman he has never met, Miss Bella Wilfer. However, a Thames River waterman named Gaffar Hexam and his daughter Lizzie discover a corpse in the river with papers identifying the latter as John Harmon. When Mortimer learns of this death, he and his close friend Eugene Wrayburn head toward the river to identify the body. These events led to the following subplots:

*John Harmon fakes his death and assumes the identity of John Rokesmith, the Boffins' social secretary, in order to ascertain Bella Wilfer's character. John had recruited a sailor to impersonate him, but the latter betrayed him by drugging and later, robbing him. However, the sailor was later betrayed by others who not only robbed him, but also murdered him. The Hexams had discovered the sailor's body.

*Old Mr. Harmon's employees, Nicodemus and Henrietta Boffin inherit the Harmon fortune and take in Bella Wilfer as a ward to compensate for her loss, following John's "death".

*Gaffer Hexam's embittered former partner, Roger "Rogue" Riderhood falsely accused Hexam of murdering "Harmon".

*While accompanying his friend, Mortimer Lightwood, to identify Harmon's body, Eugene Wrayburn meets and falls in love with Hexam's daughter, Lizzie.

*Charley Hexam, Lizzie's younger brother, has a headmaster named Bradley Headstone, who becomes romantically and violently obsessed with Lizzie.

*Mr. Boffin hires a ballad-seller with a wooden leg named Silas Wegg to read for him. When he finds another will of Old Harmon's in the dust, he schemes with a taxidermist named Mr. Venus to blackmail his newly rich employer.

One of the reasons I had such difficulties in embracing the 1998 version of "OUR MUTUAL FRIEND" was the complex nature of the narrative. The story began with the death of the fake John Harmon and the latter's deception and spiraled out into different subplots. Years ago, I had made the mistake of assuming that most of these subplots had no connection whatsoever. Following my other viewings of the 1998 miniseries and this production, I now realize that the subplots had three major connections - money, class and John Harmon. Nearly every subplot had something to do with money, class or both. As for John Harmon . . . I found myself pondering on the fates of the main characters if John had not made that decision to recruit that sailor into his deception regarding his identity. Perhaps some of the subplots would have panned out - John and Bella's marriage (if he had agreed to the terms of his father's will), Charley Hexam's education, Lizzie Hexam's introduction to Bradley Headstone and her subsequent rejection of his marriage proposal. But there are some - Lizzie meeting Eugene Wrayburn, Eugene and Bradley's conflict, and Silas Wegg's attempt to blackmail Boffin - definitely would not have happened if John had not engaged in any deception on his part. Nearly the entire story seemed to be a case of "the Six Degrees of John Harmon".

One story arc from the novel seemed to be missing in this series - namely the attempt made by elite, yet impoverished newlyweds Alfred and Sophronia Lammle to befriend and scam a young heiress named Georgiana Podsnap. I can understand why the screenwriters had never included this arc into the miniseries, considering that the Lammles and Miss Podsnap had no connection to John Harmon, whatsoever. But apparently, the screenwriters had decided to delete them altogether, unlike screenwriter Sandy Welch, who had used the Lammles to go after Mr. Boffin in the 1998 adapation.

And how did "OUR MUTUAL FRIENDS" handled the narrative's multi-arcs? I thought director Peter Hammond, along with screenwriters Julia Jones and Donald Churchill managed to handle them quite well. Despite the various arcs being scattered to winds, all three managed to convey how they all connected in the end. My only complaint was how the director and the writers introduced the various arcs. I noticed that they mystery surrounding the discovery of John Harmon's body seemed to dominate the series' first episode, whereas the introductions of the Boffins and Bella Wilfer seemed to dominate the second. This seemed to give "OUR MUTUAL FRIEND"'s narrative a "paint-by-the-numbers" style in the miniseries' first third. From Episode Three and onward, Hammond, Jones and Churchill seemed to have no trouble juggling the various arcs within an episode.

But as much as I had enjoyed "OUR MUTUAL FRIEND", I have a few quibbles. Like a good number of BBC/ITV costume dramas between the 1950s and the 1980s, this production seemed to suffer from from the occasional slow pacing, due to Hammond shooting the miniseries more like a stage play. Granted, there were a few scenes that seemed avoid this fallacy, due to being filmed in an exterior setting - the Hexams' discovery of the fake John Harmon's body, Lizzie Hexam's discovery of the dying Betty Higden and Bradley Headstone's attack upon Eugene Wrayburn. But a good number of scenes - mainly those with interior settings and those that featured Silas Wegg and Mr. Venus' blackmail conspiracy - seemed to drag nearly forever, to the point that I found myself wondering if I was watching a televised stage play. I have one last complaint. The miniseries ended with the main characters briefly discussing Bradley Headstone's fate with a few words, not long after Eugene and Lizzie's marriage. As much as I had enjoyed this production, I found this ending rather abrupt and cold - quite disappointing, when I recall how the 1998 miniseries had ended.

As much as I had enjoyed many of the performances in the miniseries, there were the occasional bouts of hammy acting that left me wincing. For me, the biggest offenders proved to be Alfie Bass, Edmond Bennett, David Troughton, and Kathleen Harrison. Do not get me wrong. They all managed to convey their characters' personalities very well. But I believe they had indulged just a bit too much in stagey or hammy acting for my taste. But there were performances that I had actually enjoyed. Granted, performers like Leo McKern and Polly James, who portrayed Mr. Boffin and Jenny Wren respectively, had their moments of hammy acting. But I thought they managed to give first-rate performances in the long run, creating some memorable interpretations of their characters. However, the series featured some excellent supporting performances from the likes of Andrew Ray, Hilda Barry, John Collin, Ray Mort, Patricia Lawrence and Ronald Lacey.

The miniseries also featured some outstanding performances. They included John McInery as the intelligent, yet compassionate John Harmon; Lesley Dunlop, whose Lizzie Hexam managed to be warm and caring without any taint of treacly behavior; Jack Wild as Lizzie's eager and ambitious younger brother Charley Hexam; and Warren Clarke as Bradley Headstone, who managed to be both sympathetic, yet frightening at the same time. Yet, I believe the two best performances came from Nicholas Jones and Jane Seymour as Eugene Rayburn and Bella Wilfer. Jones gave a subtle, yet very complex performance as the roguish Eugene, who seemed torn by his love for Lizzie and his reluctance to pursue her honestly, due to her lower class. Seymour's portrayal of Bella struck me as equally complex, as she managed to convey her character's growing development from the mercenary and shallow girl to a warm, generous and yet spirited woman.

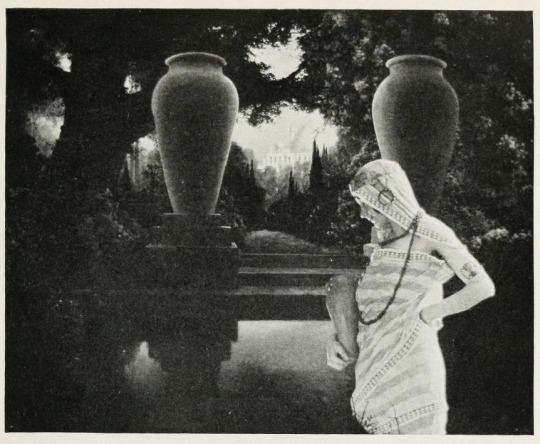

Aside from the opening shot of the Thames River for each episode, I must admit that I found myself unimpressed by Elmer Cossey's cinematography and Sam Barclay's lighting. Not only did I find the miniseries' visuals rather flat, but also a bit too dark. On the other hand, I thought Chris Pemsel's production designs pretty spot-on. I thought he did a competent job in re-creating mid-19th century London and England. I especially have to give praise to Robin Fraser-Paye's costume designs. I found his costumes - especially for female characters like Bella Wilfer, Lizzie Hexam, Mrs. Boffin and Jenny Wren - rather exquisite, as shown in the image below:

As for the hairstyles featured in "OUR MUTUAL FRIEND" . . . I have mixed feelings about them. I have no idea who the hairstylist was, but he or she did managed to come close in re-creating mid-19th century hairstyles. Only those worn by most of the younger female characters seemed to be loose curls or flowing curly hair in the style of those featured in many pre-Raphaelite paintings - especially by Lesley Dunlop and Polly James. Although such hairstyles were popular in mid-19th century art (especially in Britain), I have grave doubts that many women - or many young women between the 1840s and the 1860s wore their hair in such a manner.

Overall, I cannot deny that "OUR MUTUAL FRIEND" was a first-rate adaptation of Charles Dickens' 1864-1865 novel. Yes, I had a few issues that included the miniseries' photography, some writing decisions, a few over-the-top performances and the belief that I felt I was watching a filmed play. But despite these quibbles, "OUR MUTUAL FRIEND" also featured some top-notch performances from a cast led by John McInery and a screenplay by Julia Jones and Donald Churchill that did Dickens' novel proud.

#costume drama#period drama#period dramas#charles dickens#our mutual friend#our mutual friend 1976#victorian age#john mcinery#jane seymour#lesley dunlop#nicholas jones#warren clarke#leo mckern#polly james#andrew ray#ronald lacey#alfie bass#kathleen harrison#hilda barry#john collin#david troughton#ray mort#patricia lawrence#edmund bennett#peter hammond#john harmon#bbc drama#julia jones#donald churchill

1 note

·

View note

Text

Today in History: November 19, Lincoln speaks at Gettysburg

Today in History: November 19, Lincoln speaks at Gettysburg

Today in History

Today is Saturday, Nov. 19, the 323rd day of 2022. There are 42 days left in the year.

Today’s Highlight in History:

On Nov. 19, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln dedicated a national cemetery at the site of the Civil War battlefield of Gettysburg in Pennsylvania.

On this date:

In 1831, the 20th president of the United States, James Garfield, was born in Orange Township, Ohio.

In…

View On WordPress

#Adam Driver#Alan Bean#Ann Curry#Camaron Marvel Ochs#Charles Manson#Crime#Donald Trump#General news#Government and politics#joe biden#Kathleen Quinlan#Patrick Kane#Pervez Musharraf#Ronald Reagan#Sharon Tate#Tom Harkin#Tyga#Warren Rudman

0 notes

Text

Ilya Kaminsky, Deaf Republic

@LamechLamarch25 on Twitter

“Good Bones” by Maggie Smith

“The Last Song on Earth,” Adam Melchor & Emily Warren

Kathleen Dean Moore, If Your House is on Fire

#environmentalism#environmental justice#climate change#climate justice#environmental activism#shop local#eat local#poetry#writing#words#lyrics#nature#earth#take action#greta thunberg#climate activism#web weaving#web weave#parallels

259 notes

·

View notes

Text

By Jessica Corbett

Common Dreams

June 20, 2024

"Right-wing billionaires hoped an obscure legal case would blow up the tax code to avoid paying what they owe, but this effort failed," said the Democratic senator after the Moore v. United States decision.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren was among the economic justice advocates cheering Thursday after the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a tax on Americans with shares of certain foreign corporations—a win for the Massachusetts Democrat and other wealth tax advocates.

"Right-wing billionaires hoped an obscure legal case would blow up the tax code to avoid paying what they owe, but this effort failed at the Supreme Court," Warren said in response to the 7-2 ruling in Moore v. United States. "The fight goes on to tax the rich, pass a wealth tax on ultra-millionaires and billionaires, and make the system more fair."

Although the narrow decision doesn't explicitly affirm the constitutionality of federal wealth tax proposals from congressional progressives including Warren, court watchers had feared a ruling in favor of Charles and Kathleen Moore—a Washington couple who challenged the mandatory repatriation tax (MRT) in Republicans' 2017 tax law—would disrupt efforts to impose such policies.

The high court heard the case in December. Conservative Justice Brett Kavanaugh on Thursday delivered the majority opinion that the MRT "does not exceed Congress' constitutional authority." He was joined by Chief Justice John Roberts and the three liberals. Justice Amy Coney Barrett concurred in the judgment, joined by Justice Samuel Alito, who had faced calls to sit this case out.

Conservative Justice Clarence Thomas—who has provoked pressure to recuse himself from multiple cases or even leave the court by accepting and not reporting gifts from ultrarich Republicans—dissented, joined by Justice Neil Gorsuch. Thomas argued "the Moores are correct" that "a tax on unrealized investment gains is not a tax on 'incomes' within the meaning of the 16th Amendment, and it therefore cannot be imposed 'without apportionment among the several states.'"

The Roosevelt Institute and Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) warned in a September report that a decision siding with the Moores could have led nearly 400 multinational corporations to collectively receive more than $270 billion in tax relief.

"Today's ruling is a win for anyone who didn't shelter income in offshore tax havens before 2018," ITEP executive director Amy Hanauer said Thursday. "It preserves close to $300 billion of tax revenue paid by some of the biggest and most profitable corporations in human history."

"If the court had retroactively repealed this one-time tax, any other way of making up the resulting shortfall would have fallen far more heavily on middle-and-low-income families and small businesses," she added. "The Supreme Court also could have taken an activist turn of the worst kind by preemptively ruling federal wealth taxes unconstitutional today. To its credit, the court did not do so."

Groundwork Collaborative executive director Lindsay Owens similarly called the ruling "great news," adding that "next year, there is nothing standing in Congress' way to make the wealthy pay up."

Meanwhile, Morris Pearl, chair of the Patriotic Millionaires and a former managing director at BlackRock, had a more mixed response, saying that "we are relieved that the Supreme Court chose not to overreach in its Moore v. U.S. decision. The plaintiffs' patently absurd argument, based on incorrect and seemingly fabricated facts, threatened to upend the tax code and preemptively declare taxes on wealth and unrealized capital gains unconstitutional. The court chose not to do so."

"But we remain deeply alarmed for two reasons. First, it is now evident that four Supreme Court justices are enthralled by the influence of billionaires. In their concurring opinion, Justices Barrett and Alito asserted that unrealized capital gains cannot be taxed, as did Thomas and Gorsuch in their dissent, which said there is a realization requirement for income tax," Pearl said. "These justices have now signaled their intention to declare taxes on wealth and unrealized capital gains unconstitutional."

"Second, the Supreme Court should never have agreed to hear this case in the first place," he continued. "Billionaires are shamelessly buying influence on the Court. While seven Justices rejected this specific attempt by plutocrats to avoid their patriotic duty, this does not change the fact that several members of the Supreme Court have corrupt relationships with billionaire benefactors looking to purchase outcomes on the court."

This post has been updated with comment from the Patriotic Millionaires.

#elizabeth warren#groundwork collaborative#institute on taxation and economic policy#moore v. united states#tax the rich#taxation#wealth tax

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

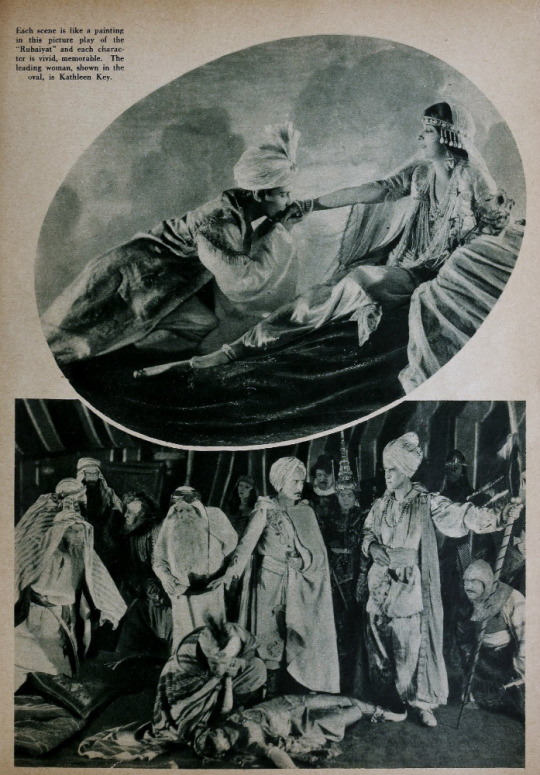

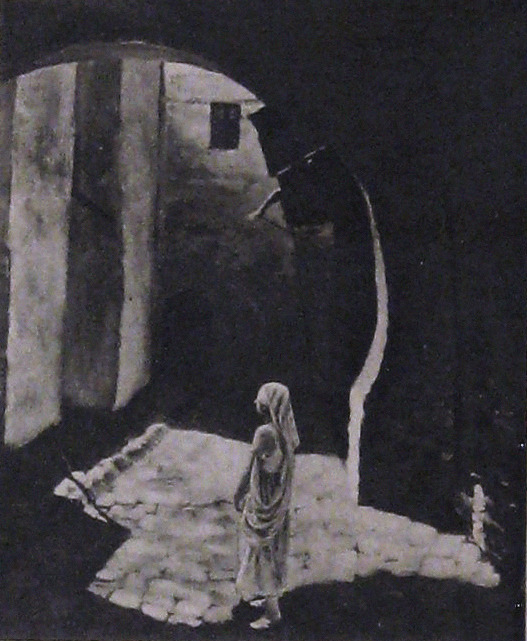

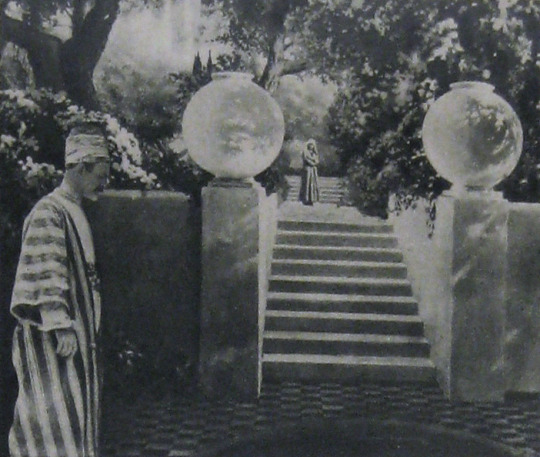

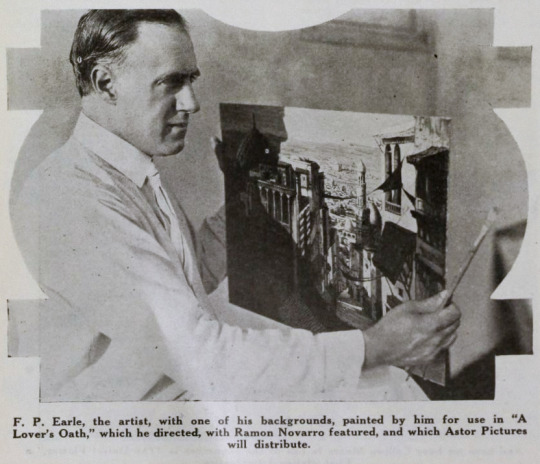

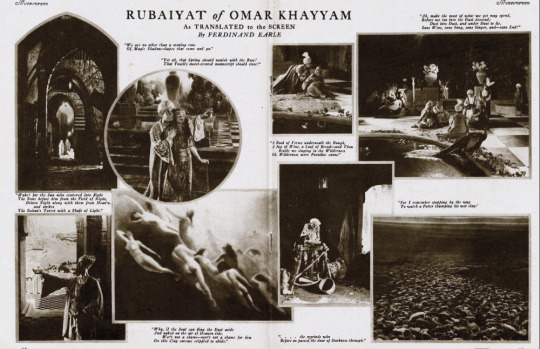

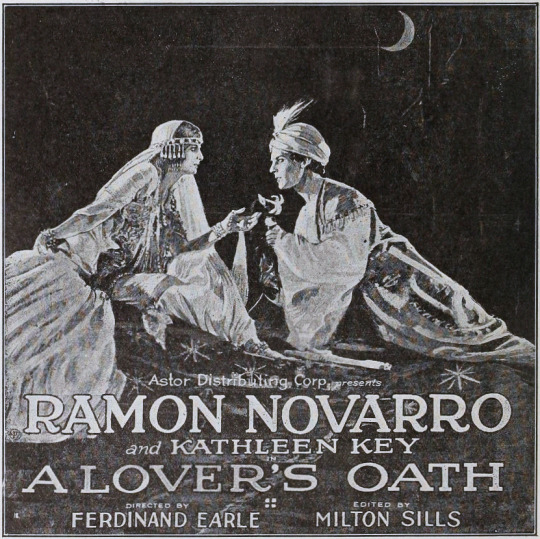

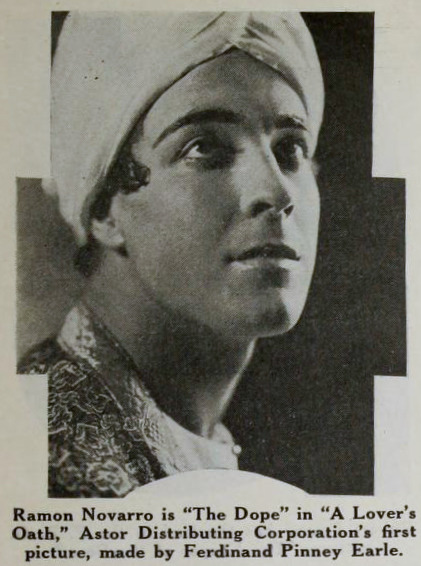

(Mostly) Lost, but Not Forgotten: Omar Khayyam (1923) / A Lover’s Oath (1925)

Alternate Titles: The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, The Rubaiyat, Omar Khayyam, Omar

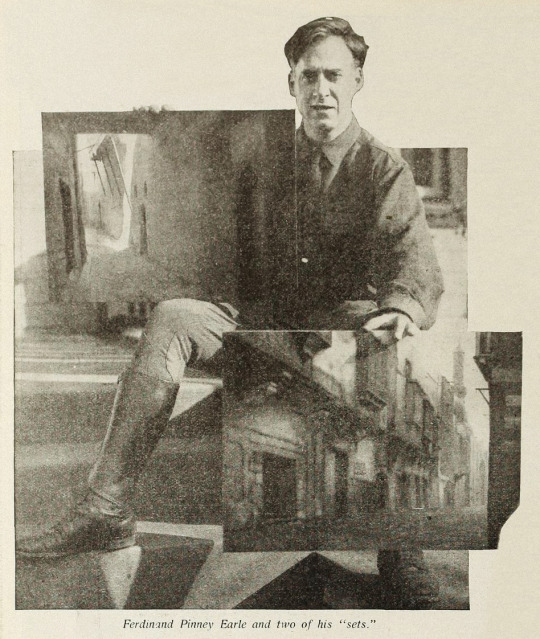

Direction: Ferdinand Pinney Earle; assisted by Walter Mayo

Scenario: Ferdinand P. Earle

Titles: Marion Ainslee, Ferdinand P. Earle (Omar), Louis Weadock (A Lover’s Oath)

Inspired by: The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, as edited & translated by Edward FitzGerald

Production Manager: Winthrop Kelly

Camera: Georges Benoit

Still Photography: Edward S. Curtis

Special Photographic Effects: Ferdinand P. Earle, Gordon Bishop Pollock

Composer: Charles Wakefield Cadman

Editors: Arthur D. Ripley (The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam version), Ethel Davey & Ferdinand P. Earle (Omar / Omar Khayyam, the Director’s cut of 1922), Milton Sills (A Lover’s Oath)

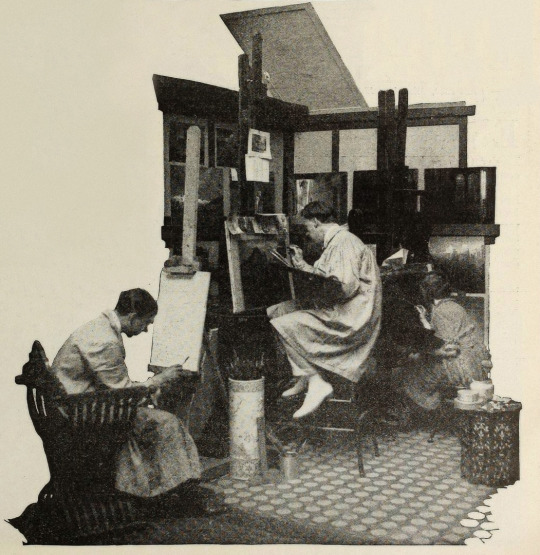

Scenic Artists: Frank E. Berier, Xavier Muchado, Anthony Vecchio, Paul Detlefsen, Flora Smith, Jean Little Cyr, Robert Sterner, Ralph Willis

Character Designer: Louis Hels

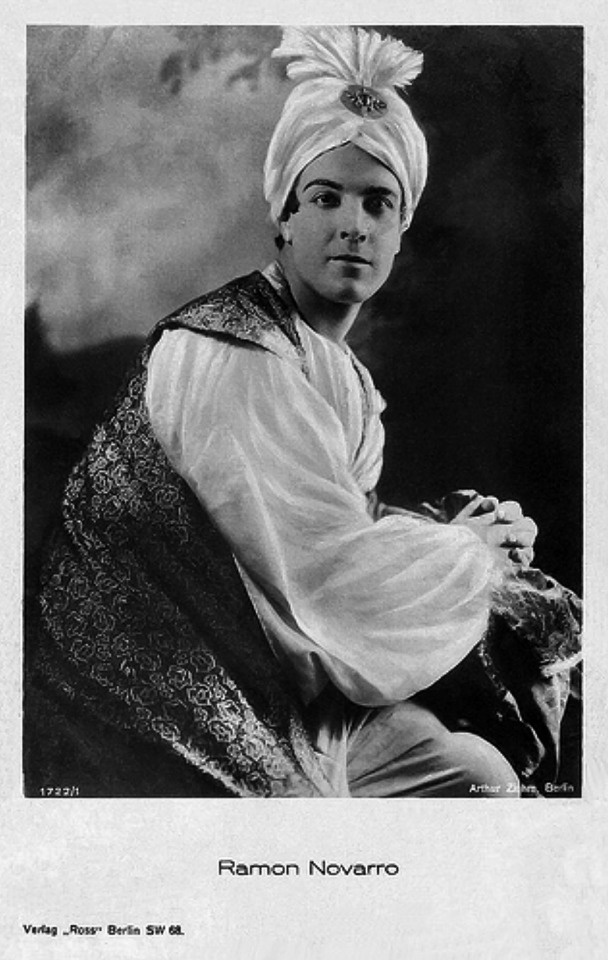

Choreography: Ramon Novarro (credited as Ramon Samaniegos)

Technical Advisors: Prince Raphael Emmanuel, Reverend Allan Moore, Captain Dudley S. Corlette, & Captain Montlock or Mortlock

Studio: Ferdinand P. Earle Productions / The Rubaiyat, Inc. (Production) & Eastern Film Corporation (Distribution, Omar), Astor Distribution Corporation [States Rights market] (Distribution, A Lover’s Oath)

Performers: Frederick Warde, Edwin Stevens, Hedwiga Reicher, Mariska Aldrich, Paul Weigel, Robert Anderson, Arthur Carewe, Jesse Weldon, Snitz Edwards, Warren Rogers, Ramon Novarro (originally credited as Ramon Samaniegos), Big Jim Marcus, Kathleen Key, Charles A. Post, Phillippe de Lacy, Ferdinand Pinney Earle

Premiere(s): Omar cut: April 1922 The Ambassador Theatre, New York, NY (Preview Screening), 12 October 1923, Loew’s New York, New York, NY (Preview Screening), 2 February 1923, Hoyt’s Theatre, Sydney, Australia (Initial Release)

Status: Presumed lost, save for one 30 second fragment preserved by the Academy Film Archive, and a 2.5 minute fragment preserved by a private collector (Old Films & Stuff)

Length: Omar Khayyam: 8 reels , 76 minutes; A Lover’s Oath: 6 reels, 5,845 feet (though once listed with a runtime of 76 minutes, which doesn’t line up with the stated length of this cut)

Synopsis (synthesized from magazine summaries of the plot):

Omar Khayyam:

Set in 12th century Persia, the story begins with a preface in the youth of Omar Khayyam (Warde). Omar and his friends, Nizam (Weigel) and Hassan (Stevens), make a pact that whichever one of them becomes a success in life first will help out the others. In adulthood, Nizam has become a potentate and has given Omar a position so that he may continue his studies in mathematics and astronomy. Hassan, however, has grown into quite the villain. When he is expelled from the kingdom, he plots to kidnap Shireen (Key), the sheik’s daughter. Shireen is in love with Ali (Novarro). In the end it’s Hassan’s wife (Reicher) who slays the villain then kills herself.

A Lover’s Oath:

The daughter of a sheik, Shireen (Key), is in love with Ali (Novarro), the son of the ruler of a neighboring kingdom. Hassan covets Shireen and plots to kidnap her. Hassan is foiled by his wife. [The Sills’ edit places Ali and Shireen as protagonists, but there was little to no re-shooting done (absolutely none with Key or Novarro). So, most critics note how odd it is that all Ali does in the film is pitch woo, and does not save Shireen himself. This obviously wouldn’t have been an issue in the earlier cut, where Ali is a supporting character, often not even named in summaries and news items. Additional note: Post’s credit changes from “Vizier” to “Commander of the Faithful”]

Additional sequence(s) featured in the film (but I’m not sure where they fit in the continuity):

Celestial sequences featuring stars and planets moving through the cosmos

Angels spinning in a cyclone up to the heavens

A Potters’ shop sequence (relevant to a specific section of the poems)

Harem dance sequence choreographed by Novarro

Locations: palace gardens, street and marketplace scenes, ancient ruins

Points of Interest:

“The screen has been described as the last word in realism, but why confine it there? It can also be the last word in imaginative expression.”

Ferdinand P. Earle as quoted in Exhibitors Trade Review, 4 March 1922

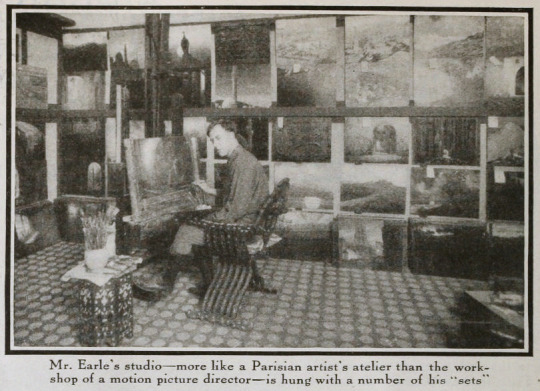

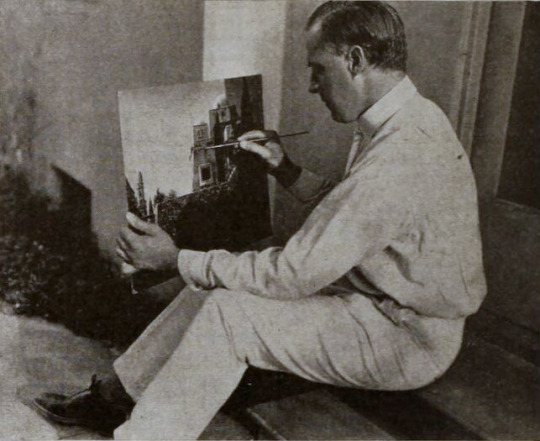

The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam was a massive best seller. Ferdinand Pinney Earle was a classically trained artist who studied under William-Adolphe Bougueraeu and James McNeill Whistler in his youth. He also had years of experience creating art backgrounds, matte paintings, and art titles for films. Charles Wakefield Cadman was an accomplished composer of songs, operas, and operettas. Georges Benoit and Gordon Pollock were experienced photographic technicians. Edward S. Curtis was a widely renowned still photographer. Ramon Novarro was a name nobody knew yet—but they would soon enough.

When Earle chose The Rubaiyat as the source material for his directorial debut and collected such skilled collaborators, it seemed likely that the resulting film would be a landmark in the art of American cinema. Quite a few people who saw Earle’s Rubaiyat truly thought it would be:

William E. Wing writing for Camera, 9 September 1922, wrote:

“Mr. Earle…came from the world of brush and canvass, to spread his art upon the greater screen. He created a new Rubaiyat with such spiritual colors, that they swayed.”

…

“It has been my fortune to see some of the most wonderful sets that this Old Earth possesses, but I may truly say that none seized me more suddenly, or broke with greater, sudden inspiration upon the view and the brain, than some of Ferdinand Earle’s backgrounds, in his Rubaiyat.

“His vision and inspired art seem to promise something bigger and better for the future screen.”

As quoted in an ad in Film Year Book, 1923:

“Ferdinand Earle has set a new standard of production to live up to.”

Rex Ingram

“Fifty years ahead of the time.”

Marshall Neilan

The film was also listed among Fritz Lang’s Siegfried, Chaplin’s Gold Rush, Fairbanks’ Don Q, Lon Chaney’s Phantom of the Opera and The Unholy Three, and Erich Von Stroheim’s Merry Widow by the National Board of Review as an exceptional film of 1925.

So why don’t we all know about this film? (Spoiler: it’s not just because it’s lost!)

The short answer is that multiple dubious legal challenges arose that prevented Omar’s general release in the US. The long answer follows BELOW THE JUMP!

Earle began the project in earnest in 1919. Committing The Rubaiyat to film was an ambitious undertaking for a first-time director and Earle was striking out at a time when the American film industry was developing an inferiority complex about the level of artistry in their creative output. Earle was one of a number of artists in the film colony who were going independent of the emergent studio system for greater protections of their creative freedoms.

In their adaptation of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, Earle and Co. hoped to develop new and perfect existing techniques for incorporating live-action performers with paintings and expand the idea of what could be accomplished with photographic effects in filmmaking. The Rubaiyat was an inspired choice. It’s not a narrative, but a collection of poetry. This gave Earle the opportunity to intersperse fantastical, poetic sequences throughout a story set in the lifetime of Omar Khayyam, the credited writer of the poems. In addition to the fantastic, Earle’s team would recreate 12th century Persia for the screen.

Earle was convinced that if his methods were perfected, it wouldn’t matter when or where a scene was set, it would not just be possible but practical to put on film. For The Rubaiyat, the majority of shooting was done against black velvet and various matte photography and multiple exposure techniques were employed to bring a setting 800+ years in the past and 1000s of miles removed to life before a camera in a cottage in Los Angeles.

Note: If you’d like to learn a bit more about how these effects were executed at the time, see the first installment of How’d They Do That.

Unfortunately, the few surviving minutes don’t feature much of this special photography, but what does survive looks exquisite:

see all gifs here

Earle, knowing that traditional stills could not be taken while filming, brought in Edward S. Curtis. Curtis developed techniques in still photography to replicate the look of the photographic effects used for the film. So, even though the film hasn’t survived, we have some pretty great looking representations of some of the 1000s of missing feet of the film.

Nearly a year before Curtis joined the crew, Earle began collaboration with composer Charles Wakefield Cadman. In another bold creative move, Cadman and Earle worked closely before principal photography began so that the score could inform the construction and rhythm of the film and vice versa.

By the end of 1921 the film was complete. After roughly 9 months and the creation of over 500 paintings, The Rubaiyat was almost ready to meet its public. However, the investors in The Rubaiyat, Inc., the corporation formed by Earle to produce the film, objected to the ample reference to wine drinking (a comical objection if you’ve read the poems) and wanted the roles of the young lovers (played by as yet unknown Ramon Novarro and Kathleen Key) to be expanded. The dispute with Earle became so heated that the financiers absconded with the bulk of the film to New York. Earle filed suit against them in December to prevent them from screening their butchered and incomplete cut. Cadman supported Earle by withholding the use of his score for the film.

Later, Eastern Film Corp. brokered a settlement between the two parties, where Earle would get final cut of the film and Eastern would handle its release. Earle and Eastern agreed to change the title from The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam to simply Omar. Omar had its first official preview in New York City. It was tentatively announced that the film would have a wide release in the autumn.

However, before that autumn, director Norman Dawn launched a dubious patent-infringement suit against Earle and others. Dawn claimed that he owned the sole right to use multiple exposures, glass painting for single exposure, and other techniques that involved combining live action with paintings. All the cited techniques had been widespread in the film industry for a decade already and eventually and expectedly Dawn lost the suit. Despite Earle’s victory, the suit effectively put the kibosh on Omar’s release in the US.

Earle moved on to other projects that didn’t come to fruition, like a Theda Bara film and a frankly amazing sounding collaboration with Cadman to craft a silent-film opera of Faust. Omar did finally get a release, albeit only in Australia. Australian news outlets praised the film as highly as those few lucky attendees of the American preview screenings did. The narrative was described as not especially original, but that it was good enough in view of the film’s artistry and its imaginative “visual phenomena” and the precision of its technical achievement.

One reviewer for The Register, Adelaide, SA, wrote:

“It seems almost an impossibility to make a connected story out of the short verse of the Persian of old, yet the producer of this classic of the screen… has succeeded in providing an entertainment that would scarcely have been considered possible. From first to last the story grips with its very dramatic intensity.”

While Omar’s American release was still in limbo, “Ramon Samaniegos” made a huge impression in Rex Ingram’s Prisoner of Zenda (1922, extant) and Scaramouche (1923, extant) and took on a new name: Ramon Novarro. Excitement was mounting for Novarro’s next big role as the lead in the epic Ben-Hur (1925, extant) and the Omar project was re-vivified.

A new company, Astor Distribution Corp., was formed and purchased the distribution rights to Omar. Astor hired actor (note, not an editor) Milton Sills to re-cut the film to make Novarro and Key more prominent. The company also re-wrote the intertitles, reduced the films runtime by more than ten minutes, and renamed the film A Lover’s Oath. Earle had moved on by this point, vowing to never direct again. In fact, Earle was indirectly working with Novarro and Key again at the time, as an art director on Ben-Hur!

Despite Omar’s seemingly auspicious start in 1920, it was only released in the US on the states rights market as a cash-in on the success of one of its actors in a re-cut form five years later.

That said, A Lover’s Oath still received some good reviews from those who did manage to see it. Most of the negative criticism went to the story, intertitles, and Sills’ editing.

What kind of legacy could/should Omar have had? I’m obviously limited in my speculation by the fact that the film is lost, but there are a few key facts about the film’s production, release, and timing to consider.

The production budget was stated to be $174,735. That is equivalent to $3,246,994.83 in 2024 dollars. That is a lot of money, but since the production was years long and Omar was a period film set in a remote locale and features fantastical special effects sequences, it’s a modest budget. For contemporary perspective, Robin Hood (1922, extant) cost just under a million dollars to produce and Thief of Bagdad (1924, extant) cost over a million. For a film similarly steeped in spectacle to have nearly 1/10th of the budget is really very noteworthy. And, perhaps if the film had ever had a proper release in the US—in Earle’s intended form (that is to say, not the Sills cut)—Omar may have made as big of a splash as other epics.

It’s worth noting here however that there are a number of instances in contemporary trade and fan magazines where journalists off-handedly make this filmmaking experiment about undermining union workers. Essentially implying that that value of Earle’s method would be to continue production when unionized workers were striking. I’m sure that that would absolutely be a primary thought for studio heads, but it certainly wasn’t Earle’s motivation. Often when Earle talks about the method, he focuses on being able to film things that were previously impossible or impracticable to film. Driving down filming costs from Earle’s perspective was more about highlighting the artistry of his own specialty in lieu of other, more demanding and time-consuming approaches, like location shooting.

This divide between artists and studio decision makers is still at issue in the American film and television industry. Studio heads with billion dollar salaries constantly try to subvert unions of skilled professionals by pursuing (as yet) non-unionized labor. The technical developments of the past century have made Earle’s approach easier to implement. However, just because you don’t have to do quite as much math, or time an actor’s movements to a metronome, does not mean that filming a combination of painted/animated and live-action elements does not involve skilled labor.

VFX artists and animators are underappreciated and underpaid. In every new movie or TV show you watch there’s scads of VFX work done even in films/shows that have mundane, realistic settings. So, if you love a film or TV show, take the effort to appreciate the work of the humans who made it, even if their work was so good you didn’t notice it was done. And, if you’ve somehow read this far, and are so out of the loop about modern filmmaking, Disney’s “live-action” remakes are animated films, but they’ve just finagled ways to circumvent unions and low-key delegitimize the skilled labor of VFX artists and animators in the eyes of the viewing public. Don’t fall for it.

VFX workers in North America have a union under IATSE, but it’s still developing as a union and Marvel & Disney workers only voted to unionize in the autumn of 2023. The Animation Guild (TAG), also under the IATSE umbrella, has a longer history, but it’s been growing rapidly in the past year. A strike might be upcoming this year for TAG, so keep an eye out and remember to support striking workers and don’t cross picket lines, be they physical or digital!

Speaking of artistry over cost-cutting, I began this post with a mention that in the early 1920s, the American film industry was developing an inferiority complex in regard to its own artistry. This was in comparison to the European industries, Germany’s being the largest at the time. It’s frustrating to look back at this period and see acceptance of the opinion that American filmmakers weren’t bringing art to film. While yes, the emergent studio system was highly capitalistic and commercial, that does not mean the American industry was devoid of home-grown artists.

United Artists was formed in 1919 by Douglas Fairbanks, Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford, and D.W. Griffith precisely because studios were holding them back from investing in their art—within the same year that Earle began his Omar project. While salaries and unforgiving production schedules were also paramount concerns in the filmmakers going independent, a primary impetus was that production/distribution heads exhibited too much control over what the artists were trying to create.

Fairbanks was quickly expanding his repertoire in a more classical and fantastic direction. Cecil B. DeMille made his first in a long and very successful string of ancient epics. And the foreign-born children of the American film industry, Charlie Chaplin, Rex Ingram, and Nazimova, were poppin’ off! Chaplin was redefining comedic filmmaking. Ingram was redefining epics. Nazimova independently produced what is often regarded as America’s first art film, Salome (1923, extant), a film designed by Natacha Rambova, who was *gasp* American. Earle and his brother, William, had ambitious artistic visions of what could be done in the American industry and they also had to self-produce to get their work done.

Meanwhile, studio heads, instead of investing in the artists they already had contracts with, tried to poach talent from Europe with mixed success (in this period, see: Ernst Lubitsch, F.W. Murnau, Benjamin Christensen, Mauritz Stiller, Victor Sjöström, and so on). I’m in no way saying it was the wrong call to sign these artists, but all of these filmmakers, even if they found success in America, had stories of being hired to inject the style and artistry that they developed in Europe into American cinema, and then had their plans shot down or cut down to a shadow of their creative vision. Even Stiller, who tragically died before he had the opportunity to establish himself in the US, faced this on his first American film, The Temptress (1926, extant), on which he was replaced. Essentially, the studio heads’ actions were all hot air and spite for the filmmakers who’d gone independent.

Finally I would like to highlight Ferdinand Earle’s statement to the industry, which he penned for from Camera in 14 January 1922, when his financial backers kidnapped his film to re-edit it on their terms:

MAGNA CHARTA

Until screen authors and producers obtain a charter specifying and guaranteeing their privileges and rights, the great slaughter of unprotected motion picture dramas will go merrily on.

Some of us who are half artists and half fighters and who are ready to expend ninety per cent of our energy in order to win the freedom to devote the remaining ten per cent to creative work on the screen, manage to bring to birth a piteous, half-starved art progeny.

The creative artist today labors without the stimulus of a public eager for his product, labors without the artistic momentum that fires the artist’s imagination and spurs his efforts as in any great art era.

Nowadays the taint of commercialism infects the seven arts, and the art pioneer meets with constant petty worries and handicaps.

Only once in a blue moon, in this matter-of-fact, dollar-wise age can the believer in better pictures hope to participate in a truely [sic] artistic treat.

In the seven years I have devoted to the screen, I have witnessed many splendid photodramas ruined by intruding upstarts and stubborn imbeciles. And I determined not to launch the production of my Opus No. 1 until I had adequately protected myself against all the usual evils of the way, especially as I was to make an entirely new type of picture.

In order that my film verison [sic] of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam might be produced under ideal conditions and safeguarded from intolerable interferences and outside worries, I entered into a contract with the Rubaiyat, Inc., that made me not only president of the corporation and on the board of directors, but which set forth that I was to be author, production manager, director, cutter and film editor as well as art director, and that no charge could be made against the production without my written consent, and that my word was to be final on all matters of production. The late George Loane Tucker helped my attorney word the contract, which read like a splendid document.

Alas, I am now told that only by keeping title to a production until it is declared by yourself to be completed is it safe for a scenario writer, an actor or a director, who is supposedly making his own productions, to contract with a corporation; otherwise he is merely the servant of that corporation, subject at any moment to discharge, with the dubious redress of a suit for damages that can with difficulty be estimated and proven.

Can there be any hope of better pictures as long as contracts and copyrights are no protection against financial brigands and bullies?

We have scarcely emerged from barbarism, for contracts, solemnly drawn up between human beings, in which the purposes are set forth in the King’s plainest English, serve only as hurdles over which justice-mocking financiers and their nimble attorneys travel with impunity, riding rough shod over the author or artist who cannot support a legal army to defend his rights. The phrase is passed about that no contract is invioliable [sic]—and yet we think we have reached a state of civilization!

The suit begun by my attorneys in the federal courts to prevent the present hashed and incomplete version of my story from being released and exhibited, may be of interest to screen writers. For the whole struggle revolves not in the slightest degree around the sanctity of the contract, but centers around the federal copyright of my story which I never transferred in writing otherwise, and which is being brazenly ignored.

Imagine my production without pictorial titles: and imagine “The Rubaiyat” with a spoken title as follows, “That bird is getting to talk too much!”—beside some of the immortal quatrains of Fitzgerald!

One weapon, fortunately, remains for the militant art creator, when all is gone save his dignity and his sense of humor; and that is the rapier blade of ridicule, that can send lumbering to his retreat the most brutal and elephant-hided lord of finance.

How edifying—the tableau of the man of millions playing legal pranks upon men such as Charles Wakefield Cadman, Edward S. Curtis and myself and others who were associated in the bloody venture of picturizing the Rubaiyat! It has been gratifying to find the press of the whole country ready to champion the artist’s cause.

When the artist forges his plowshare into a sword, so to speak, he does not always put up a mean fight.

What publisher would dare to rewrite a sonnet of John Keats or alter one chord of a Chopin ballade?

Creative art of a high order will become possible on the screen only when the rights of established, independent screen producers, such as Rex Ingram and Maurice Tourneur, are no longer interferred with and their work no longer mutilated or changed or added to by vandal hands. And art dramas, conceived and executed by masters of screen craft, cannot be turned out like sausages made by factory hands. A flavor of individuality and distinction of style cannot be preserved in machine-made melodramas—a drama that is passed from hand to hand and concocted by patchworkers and tinkerers.

A thousand times no! For it will always be cousin to the sausage, and be like all other—sausages.

The scenes of a master’s drama may have a subtle pictorial continuity and a power of suggestion quite like a melody that is lost when just one note is changed. And the public is the only test of what is eternally true or false. What right have two or three people to deprive millions of art lovers of enjoying an artist’s creation as it emerged from his workshop?

“The Rubaiyat” was my first picture and produced in spite of continual and infernal interferences. It has taught me several sad lessons, which I have endeavored in the above paragraphs to pass on to some of my fellow sufferers. It is the hope that I am fighting, to a certain extent, their battle that has given me the courage to continue, and that has prompted me to write this article. May such hubbubs eventually teach or inforce a decent regard for the rights of authors and directors and tend to make the existence of screen artisans more secure and soothing to the nerves.

FERDINAND EARLE.

---

☕Appreciate my work? Buy me a coffee! ☕

Transcribed Sources & Annotations over on the WMM Blog!

See the Timeline for Ferdinand P. Earle's Rubaiyat Adaptation

#1920s#1923#1925#omar khayyam#ferdinand pinney earle#ramon novarro#independent film#american film#silent cinema#silent era#silent film#classic cinema#classic movies#classic film#film history#history#Charles Wakefield Cadman#cinematography#The Rubaiyat#cinema#film#lost film

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lauren Aratani at The Guardian:

The US supreme court on Thursday ruled against a Washington couple who argued they were unconstitutionally taxed $15,000 for their investment in a foreign company – in a case some have argued was a backdoor attempt to ban future wealth taxes.

The case, Moore v US, put into question what assets are considered taxable income. Some experts say the case was used as a vehicle to give the supreme court an opportunity to weigh in on a hypothetical billionaire’s tax, which would raise similar questions on what assets can be taxed.

As the court was hearing the case in December, experts were worried that it put into question the long-established tax code, threatening to wreak havoc on what Americans may be taxed for.

The vote was 7-2 with Justice Clarence Thomas and Justice Neil Gorsuch dissenting. In his opinion, Justice Brett Kavanaugh described the ruling as “narrow”, leaving an opening for future challenges.

Senator Elizabeth Warren hailed the ruling. “Right-wing billionaires hoped an obscure legal case would blow up the tax code to avoid paying what they owe, but this effort failed at the supreme court. The fight goes on to tax the rich, pass a wealth tax on ultra-millionaires and billionaires, and make the system more fair,” she wrote on X.

The case focused on Charles and Kathleen Moore, a couple from Washington state who owned a small stake in an India-based company that sells affordable farm equipment in India.

Charles Moore met one of the future founders of the company, KisanKraft, when he was a software engineer at Microsoft. The Moores invested $40,000 into the company, which gave them an 11% stake.

In 2017, as part of a way to fund Donald Trump’s tax giveaway to US corporations, Americans who owned at least 10% of a foreign company were charged a one-time Mandatory Repatriation Tax (MRT) on their holding, regardless of whether the investment remained in the company, whereas such investments were previously exempt. Total tax revenue raised by the MRT is estimated to be $340bn.

SCOTUS issued a 7-2 (or 5-2-2) ruling in Moore v. United States dealing with the Mandatory Repatriation Tax in which Justice Brett Kavanaugh issued the ruling that rejected bans on wealth taxes.

See Also:

HuffPost: Supreme Court Turns Back Stealth Attack On Wealth Tax — For Now

#SCOTUS#Moore v. United States#Taxes#KisanKraft#Charles Moore#Kathleen Moore#Wealth Tax#Mandatory Repatriation Tax#Tax Cuts and Jobs Act#Repatriation#Taxation

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oscar Nominated Genre Film Performances of the 20th Century

HB Warner in Lost Horizon

Walter Huston in Devil and Daniel Webster

Robert Montgomery and James Gleason from Here Comes Mr Jordan

Angela Lansbury in Picture of Dorian Grey

James Stewart in Its a Wonderful Life

Ethel Barrymore fromThe Spiral Staircase

Cecil Kellaway from Luck of the Irish

Jean Simmons in Hamlet

Janet Leigh in Psycho

Bete Davis in What Ever Happened To Baby Jane

Agnes Moorhead in Hush Hush Sweet Charolotte

Linda Blaire,Jason Miller,and Ellen Burstyn in Exorcist

Sissie Spacek and Piper Laurie in Carrie

Alec Guiness in Star Wars

Melinda Dillon in Close Encounters of the Third Kind

LAurance Olivier in Boys from Brazil

Warren Beatty ,Dyan Cannon and Jack Warden in Heaven Can Wait

Jeff Bridges in Starman

Kathleen Turner in Peggy Sue Got Married

Sigourney Weaver in Aliens

Robin Williams in FIsher King

Brad Pitt in 12 Monkeys

Michael Clarke Duncan in Green Mile

Hayley Joel Osment and Toni Collete in 6th Sense

@ariel-seagull-wings @the-blue-fairie @themousefromfantasyland @princesssarisa @theancientvaleofsoulmaking @minimumheadroom

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Netflix true crime

Keep Sweet: Pray and Obey

Warren Jeffs saw himself as the spiritual leader of the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (FLDS), an extremist offshoot of mainstream Mormonism. In reality, he created a system of abuse and coercion, forcing members of his congregation — often underage — into marriage, blind obedience, and isolation. In this docuseries, former FLDS members and survivors come forward to share their stories. Using never-before-seen VCR footage from within the FLDS community, this series provides the well-known story with a deeply human and relatable face — told through current interviews with his wives and congregation.

Lover, Stalker, Killer

As the title suggests, Lover, Stalker, Killer is a story of a romance gone wrong. In 2012, Dave Kroupa created an online dating profile after just coming out of a long-term relationship. It’s there that he meets a single mom named Liz Golyar. Soon after, he encounters another single mother, Cari Farver, while repairing her car at his auto shop. It’s an instant connection for Kroupa and Farver, but what would unfold is a twisted love triangle that leads to harassment, digital deception, and murder.

Murdaugh Murders: A Southern Scandal

A tight-knit South Carolina community is ripped apart by a series of deadly crimes that all seem to involve one family: the Murdaughs. The two seasons of Murdaugh Murders: A Southern Scandal delve into how a prominent family used and abused their wealth and privilege to the extreme.

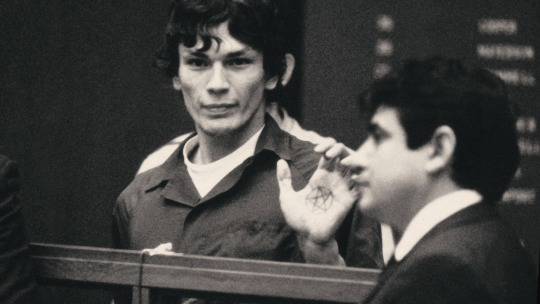

Night Stalker: The Hunt for a Serial Killer

Yeah, you’ll want to lock your doors and windows for this one. Beneath the glitz and glamor of 1985 LA lurked a prolific serial killer. Richard Ramirez hunted, tortured, and murdered his victims in terrifying ways while evading capture for one long year. Night Stalker focuses on Ramirez’s victims and the investigators behind the manhunt.

The Keepers

Who killed Sister Cathy? In 1969, the 26-year-old nun from suburban Baltimore was murdered. Her sudden death stunned the town, especially her students at Archbishop Keough High School. As investigators dug into this mystery, they learned that her death may not have been the only injustice. Was Sister Catherine Cesnik murdered to cover up sexual abuse by a school priest?

The Staircase

In 2001, novelist Michael Peterson found his wife, Kathleen Peterson, dead at the bottom of a staircase in their home. Although it was reported as an accidental death, investigators believed Peterson bludgeoned his wife and staged the murder. The Staircase documents the case against Peterson and poses the question: Did he do it?

Credit:

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

This week, the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in Moore v. United States, a case that centers on the mandatory repatriation tax (MRT). The MRT was enacted as part of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) and required corporations to a pay a one-time tax on deferred foreign profits. These are profits that were earned by foreign subsidiaries of American businesses, but not returned home and therefore not yet subjected to U.S. taxation.

The plaintiffs, Charles and Kathleen Moore, argue that a ruling in their favor would ensure Congress could never impose a wealth tax. Many on the right oppose such a tax, most famously proposed by Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and thus organizations like Americans for Tax Reform, the Cato Institute, FreedomWorks, and the Manhattan Institute have filed amicus briefs in support of the plaintiffs. In reality, the case has little to do with such a tax.

Rather, a ruling in favor of the Moores risks upending key elements of the current federal income tax and wreaking havoc on parts of the U.S. economy. As we detail with additional colleagues in an amicus brief in support of the respondent, the federal government, the Court should rule against the Moores and affirm the lower court ruling.

The Moores, shareholders in a manufacturing business based in India, were subject to the MRT on the business’s profits that had not yet been distributed to shareholders. The MRT rate is 15.5 percent if such profits were held in liquid assets such as cash or 8 percent if such profits were illiquid (invested in a factory abroad, for example). The TCJA allows taxpayers to pay the MRT in installments over eight years. The Moores’ MRT liability was approximately $15,000.

At enactment, the MTR was estimated to raise $338.8 billion and was used, in part, to finance the transition to a new system of taxing foreign profits of U.S. multinational corporations. To give a sense of the magnitude involved here: the entire TCJA was estimated to reduce revenue by $1.456 trillion, or just about four times the amount involved here.

Prior to the TCJA, the United States had a “worldwide” corporate income tax with deferred taxation of foreign profits. This meant that profits earned in a foreign country by U.S.-based multinational corporations first faced that jurisdiction’s corporate income tax. If and when those profits were repatriated to the United States, they were subject to additional taxation: the U.S. corporate tax minus a tax credit for any foreign income taxes paid. Because the U.S. corporate tax rate was among the highest in the world (35 percent), any foreign tax credit was almost never sufficient to fully offset additional U.S. tax.

This system created several perverse incentives. Corporations could avoid the additional U.S. tax by holding foreign profits overseas, which led to a significant accumulation of overseas profits. Prior to the TCJA, the Joint Committee on Taxation estimated that there were more than $3 trillion in retained foreign profits. The system also encouraged corporations to shift profits, mobile assets, and their headquarters overseas as strategies to minimize their tax liability.

The TCJA addressed these issues by moving to a “quasi-territorial” system. Under this system, U.S. corporations no longer face an additional U.S. tax when they repatriate earnings. At the same time, the TCJA enacted a minimum tax, without deferral, on foreign profits as a backstop. U.S. corporations now either pay a low-rate U.S. tax immediately on their foreign profits or not at all.

For foreign profits that were earned under the previous system but had yet to face U.S. tax, lawmakers decided that it would be an unfair windfall to completely excuse them from U.S. taxation. These profits had, after all, been earned with the expectation that they would eventually be subject to U.S. tax. And it would have been too complex to require corporations to track two stocks of profits for years or decades: pre-TCJA profits that would face tax when repatriated and post-TCJA profits that face no tax. It was far simpler and fairer to immediately wipe the slate clean with a one-time low tax on all existing unrepatriated profits.

The Moores disagree. They argue that the MRT is “an unapportioned direct tax in violation of the Constitution’s apportionment requirements.” There is an exception to this requirement: the 16th Amendment, which authorizes income taxation without apportionment among the states. But that amendment, they argue, only applies to taxes on realized income, while the MRT taxes unrealized income.

There is, however, no reason to think the MRT is unconstitutional. In fact, the Court need not even consider whether the 16th Amendment applies only to realized income for the simple reason that the MRT is not a direct tax. As an indirect tax, the MRT does not need to be apportioned among the states.

Court precedent clearly does not support the argument that a tax on foreign commerce is a direct tax. Historical sources are clear that all direct taxes are internal. In addition, the MRT is not a direct tax because it is a tax on the use of a certain business entity. Indeed, the Court cited similar grounds when, prior to the adoption of the 16th Amendment, it upheld the corporate income tax as an indirect tax.

Leaving aside any question of constitutionality, a ruling in favor of the Moores risks upending key elements of the income tax. A constitutional requirement that income be realized in order to be subject to tax would increase economic distortions, create policy uncertainty, and reduce federal revenue.

A realization requirement is undesirable because a realization-based tax system is economically incoherent. Economists generally favor one of two coherent tax bases: income or consumption. A realization-based income tax is neither. As a result, it creates economic distortions, such as an incentive to hold on to assets that have gone up in value, as well as unfairness, as equally well-off individuals are taxed differently based on when they buy and sell, and opportunities to avoid paying tax altogether.

A realization requirement would also introduce significant economic uncertainty by calling into question numerous provisions of the income tax that currently deviate from the realization principle. For example, partners in Subchapter K partnerships are taxed on their share of business profits whether or not those profits are distributed. This provision and many more could be subject to years of litigation. During this time, businesses could delay or forgo important investments.

A ruling in favor of the Moores could also put important pro-growth tax policy at risk. The current income tax system deviates from the realization principle by providing depreciation deductions. These provisions allow businesses to deduct the value of an asset prior to its disposal. Under a strict realization requirement, a taxpayer would need to wait until they sold or otherwise disposed of a fixed asset to deduct its cost, similar to how a corporate stock is treated under current law. Many proponents of pro-growth tax reform advocate for the immediate write-off (expensing) of some or all of the cost of these assets as an effective means of lowering the marginal effective tax rate on new investment. In fact, a key provision of the TCJA significantly strengthened this policy. A strict realization rule would risk upending this policy and would raise the effective tax burden on new investment.

A Moore victory could also reintroduce many of the problems with the taxation of multinational corporations that the TCJA sought to address. A realization requirement could undo elements known as Subpart F and GILTI, or global intangible low-taxed income, which tax foreign profits of U.S. multinational corporations without realization. Without these backstops, corporations would have a much greater incentive to shift profits and intellectual property into low-tax jurisdictions.

Besides introducing new economic distortions, a realization requirement could threaten a significant amount of federal revenue. The direct effect of a ruling would be a loss of hundreds of billions of dollars in revenue due to invalidation of the MRT. On top of that, the federal government also risks losing much more depending on the breadth of the ruling. Economist Eric Toder at the Tax Policy Center estimates that the federal government could lose more than $87 billion in 2024 and more than $124 billion by 2028 and every year thereafter. Congress may respond to this lost revenue by enacting taxes that are even more distortionary or by incurring even larger, and less sustainable, budget deficits.

Economists have long understood that whether or not income is realized, it is still income. Nevertheless, it is reasonable and prudent for administrative and other reasons for Congress to distinguish between realized and unrealized income in some situations. For example, measuring income from the appreciation of certain closely held businesses or other illiquid assets is difficult and Congress has reasonably decided not to subject those gains to tax until they are realized. On the other hand, the current tax treatment of partnerships is appropriate to avoid obvious tax avoidance: Such taxpayers could otherwise park their income in their business to avoid tax. It could also be reasonable for Congress to design a system to tax unrealized gains that are easy to measure, such as those that arise from the appreciation of publicly traded assets.

Finally, there is an additional, and somewhat peculiar, aspect to this case. The Moores and several amici argue that the realization requirement they believe is inherent to the 16th Amendment means that a wealth tax, unless apportioned, would also be unconstitutional. It appears as if this logic has served to motivate much of the support behind them.

While we agree that any plausible wealth tax would likely be unconstitutional, there are obvious problems with the Moores’ claim that the MRT is nothing like a wealth tax. A wealth tax applies to the full value of an asset each year. As such, it would not matter whether an asset appreciates or not: A taxpayer would be subject to tax as long as the asset had positive value. In contrast, the MRT applies to earnings and profits of a foreign enterprise, not the value of the foreign enterprise. If the Moores’ foreign business earned no profit or if prior profits had already been repatriated, they would have owed no additional tax.

Given the risks and economic shortcomings of a realization requirement, the Supreme Court should not enshrine it in the Constitution. Instead, Congress should be free to decide whether and how to tax unrealized income.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

BRIGADE FILES: ANGEL (Part 1)

Stars & Stripes Hotline [Version 1.09]

C: \login\BuddyHolly

C:\Users\mini\BrigadeFiles\Xmen

Directory of C: \BrigadeFiles\Xmen

04/25/2006 7:27 PM Total Files Listed: 15 File(s) 168,248 bytes

Directory of C:\BrigadeFiles\Xmen\WORTHINGTON_WREN.txt

[file data =

Main Alias/Moniker: Angel

Legal Name: Wren Kathleen Worthington

Other Aliases: Warren III, The Avenging Angel

Date of Birth: December 21st, 1984 (Age: 21)

Status: Alive

Species: Mutant

Sex: Female

Gender: Cisgender

Height/Weight: 5'9'' (1.75m) / 135 lbs (61.2kg)

Hair/Eye Color: Blonde / Blue

Timeline (1985 - 2002): Wren is the heiress to the Worthington Airlines travel empire. Her grandfather Warren aided in the war effort along the likes of Howard Stark, but exited defense after the war to pursue commercial travel. Under his son's ownership, Worthington Airlines became one of the biggest luxury airlines in the world. Warren Jr was so dead-set on continuing the family name that he had no other names planned but Warren III. When the baby turned out to be a girl, Wren's name was a suggestion from her mother after her birth.

Wren was an energetic child, which prompted her parents to sign her up for extracurriculars after her excitability became too much of a nuisance to both them and the family house staff. Athletics and pagentry were the two most noteworthy ventures, and the former being one Wren held in high regard all through childhood. Wren has often compared it to her wings: It's something wholly her own, and is only limited by her own applications. By adolescence, Wren was enrolled into the Massachusetts Academy. She was pressured by her parents to involve herself with the Hellions, a school clique made up of children of Hellfire Club members such as herself. Wren maintained a minimal association with the Hellions, preferring the company of the school jocks. Wren became a prized track and field star while at the Academy, and by the time she was sixteen she and her parents were routinely speaking with college and Olympic scouts.

Timeline (2002): Around her eighteenth birthday, however, when Wren's mutant traits began to develop. It reportedly started off as cramps and strains in her shoulders, then visible bruises that grew all over her upper back. Wren eventually awoke in the middle of the night from a sharp pain and discovered nubs growing out from the bruises. Wren's family was already in the area to pick her up for holiday, and Wren's father refused to send her to a hospital for alleged concern over unwanted attention on the family, and instead hired two specialists to meet with them in the Worthington winter cabin up in the Adirondack Mountains for personal treatment.

One of those specialists was none other than the Professor. Even in the short drive from the city to update, Wren's mutation was rapidly growing. By the time he has arrived, her wings had fully grown, feathers and all. Though her parents were distressed, once the pain and shock of her growing wings faded Wren was reportedly elated with her changes. The Professor has said that his and Wren's earliest exchanges mostly occurred telepathically, as Wren opted to spend winter break soaring across the area rather than he around her parents.

On the last day of holiday, Week checked her phone to find a series of voicemails from a school friend, Amanda Cobb. Amanda had confided to Wren in a moment of great distress over being abused by a coach at the Academy (Weeks earlier, Amanda had walked in on Wren inspecting the bruises along her back and assumed she was being abused by the coach as well). This revelation threw Wren into a blind rage, putting her abilities to the limit by flying uninterrupted from Adirondack to Massachusetts in little under an hour. Wren hauled the coach high into the sky and let him plummet back down. By all accounts, it was only through the Professor's psychic intervention that Wren was restrained from letting the coach crash back down to Earth. It was certainly enough to coerce the him to confess his crimes.

Timeline (2003): By the time classes resumed at the Academy, the school was so swept up in scandal that Wren's wings barely registered to most. The school board did request that Wren conceal them out of concern of "distracting" other students, to which she begrudgingly complied. To Wren's astonishment, the Hellions accepted her with open arms, revealing that they were all mutants themselves. Wren took every opportunity to abstain from the Academy grounds and finish her education through the Professor's personal tutoring, though she kept tabs with the Hellions, both out of the Professor's request and Wren's own curiosity.

Integrating with the rest of the group, Wren quickly took it upon herself to become the leader, something I didn't object to at the time. She had a far more blunt and proactive personality than I did at the time, and her background made her far better at working crowds and being a public figure than I was. At the time, Wren was also the only one of us who was an open mutant, and to her credit she took jer newfound duties as a mutant activist very seriously. This is best exemplified when Wren swooped to Bobby's defense when his own powers briefly put him in legal trouble.

Where Wren did display hesitance was when we all set out to intervene at Santo Marco. Not because she objected to us intervening, but because she recognized how her usual tactics not suit such a sensitive situation. Over the course of that mission, our group dynamic was forced to shift and adapt, and by the end congealed into the X-Men that people would come to know later that year. Wren continued to be the face of the group, but tactical duties had effectively fallen upon me.

continue data? y/n]

#earth93#comics#marvel#fanfic#comic books#x men comics#xmen#angel#archangel#genderbend#professor x#charles xavier#cyclops#scott summers#iceman#bobby drake

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Canons

These are our major canons on the site with activity monitored more closely as they're either part of our site subplots or will be in the future

Avengers

Tony Stark - taken by Kathleen

Steve Rogers (on MAC)

Sam Wilson

Bruce Banner

Natasha Romanoff (on MASH)

Clint Barton

Thor

Scott Lang

Hope van Dyne

Wanda Maximoff - adoptable NPC

Vision

Media

Christine Everhart

JJJ

Trish Walker

Mitchell Ellison

X-Men

(minor canons will be approved on a case by case basis as there are many X-men whose powers will not fit the site)

Charles Xavier - adoptable NPC (on MAC)

Jean Grey - played by rue

Scott Summers - played by kathleen

Hank McCoy (on MAC)

Bobby Drake

James Howlett - played by kathleen

Brotherhood

(same with the X-men, minor canons will be approved on a case by case basis)

Erik Lehnsherr - adoptable NPC (part of MASH)

Raven Darkholme

Lorna Dane

Amara Aquilla (part of MASH)

Hellfire

Warren Worthington III (part of MASH)

Sebastian Shaw - admin NPC (part of MASH)

Emma Frost - adoptable NPC (part of MAC)

Regan Wyngarde

Roberto da Costa

Government

Maria Hill

Nick Fury - admin NPC

Phil Coulson

Bobbi Morse

Daisy Johnson

Melinda May

Al Mackenzie

Everett Ross

Valentina de Fontaine

Sharon Carter

Stark Industries

Pepper Potts - played by rue

Happy Hogan

Leopold Fitz - played by kathleen

Jemma Simmons - played by rue

Street Teams

Peter Parker

MJ Watson - played by rue

Matt Murdock - played by rue

Frank Castle - played by kathleen

Danny Rand

Jessica Jones

Luke Cage

Young Avengers

(not yet a team but can be on the site)

Kamala Khan

Kate Bishop

Cassie Lang

Eli Bradley

America Chavez - admin NPC

David Alleyne

Fantastic Four

Reed Richards - played by rue

Sue Storm

Johnny Storm

Ben Grimm - played by kathleen

Victor von Doom - adoptable NPC

AIM/Villains

Aldrich Killian

Justin Hammer

Helmut Zemo

John Walker

Bucky Barnes - admin NPC

Alexander Pierce

Ophelia Sarkissian - adoptable NPC

Wilson Fisk

Billy Russo

Maya Lopez

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

— ❝ 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐡𝐞𝐚𝐯𝐞𝐧𝐬 𝐬𝐮𝐜𝐡 𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐜𝐞 𝐝𝐢𝐝 𝐥𝐞𝐧𝐝 𝐡𝐞𝐫, 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐬𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐢𝐠𝐡𝐭 𝐚𝐝𝐦𝐢𝐫𝐞𝐝 𝐛𝐞. ❞

𝐋𝐈𝐒𝐀 𝐂𝐑𝐎𝐖𝐍𝐄-𝐑𝐎𝐉𝐀𝐒 — daughter of comedian and actor rafael crowne, birth name juan rafael del toro, and model, actress and burlesque performer kathleen warwick. rafael's deadpan, scandalous comedy charmed many, including old money wild child kathleen warwick, leading to their faithful elopement, and many divorces and reunions. out of their union comes award winning actress lisa crowne-rojas. whether you prefer her fun, nuanced comedies or her more serious work with scorsese, or you were just around for her slinky red carpet looks or wild party stories, there's not a person in the business who didn't know her name in the 70's and 80's. married to drummer warren rojas since 1982, lisa has two wonderful twin daughters, cali and carla rojas-crowne.

#* to be tagged.#— ✧ ❝ 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐡𝐞𝐚𝐯𝐞𝐧𝐬 𝐬𝐮𝐜𝐡 𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐜𝐞 𝐝𝐢𝐝 𝐥𝐞𝐧𝐝 𝐡𝐞𝐫. ❞ reflection: lisa crowne.#— ✧ ❝ 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐬𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐢𝐠𝐡𝐭 𝐚𝐝𝐦𝐢𝐫𝐞𝐝 𝐛𝐞. ❞ musings: lisa crowne.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Remembering Carole Cook on what would have been her 99th birthday. Carole passed away just a few days ago on January 11th. Toward the end of the 1950's, Lucy hand picked young talent to be part of her 'Workshop' where she trained and put together a company of players that she needed for various Desilu shows. An actress named Mildred Cook was recommended and so Lucy tracked her down and found her doing summer stock with the Kenley Players at the Packard Music Hall in Warren, Ohio, and in that moment, plucked Mildred from the stage. Lucy suggested she change her name to Carole and the rest is history. 'Mildred thought it was a joke when she heard herself paged over the loudspeaker: "Mildred Cook, Lucille Ball is calling from Los Angeles." ...Mildred packed her clothes in a box and flew out to California for an audition and an overnight stay in Lucy's guest house. "When a maid asked me for a key to my luggage, I said 'Just cut it with a butcher knife,'" she recalled. With that remark, Lucy decided this was the person she most wanted to help.'—Kathleen Brady, The Life of Lucille Ball. #lucilleball #carolecook #happybirthday #packardmusichall #humblebeginnings #discovered #namechange #desilu #tutelage #butcherknife #inmemoryof #warrenohio #waynelvslcy https://www.instagram.com/p/CnZ1DaeO1A_/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#lucilleball#carolecook#happybirthday#packardmusichall#humblebeginnings#discovered#namechange#desilu#tutelage#butcherknife#inmemoryof#warrenohio#waynelvslcy

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes