#lakoff and johnson

Text

“Political and economic ideologies are framed in metaphorical terms. Like all other metaphors, political and and economic metaphors can hide aspects of reality. But in the area of politics and economics, metaphors matter more, because they constrain our lives. A metaphor in a political or economic system, by virtue of what it hides, can lead to human degradation.”

(this continues below the cut)

“Consider just one example: LABOR IS A RESOURCE. Most contemporary economic theories, whether capitalist or socialist, treat labor as a natural resource or commodity, on a par with raw materials, and speak in the same terms of its cost and supply. What is hidden by the metaphor is the nature of the labor. No distinction is made between meaningful labor and dehumanising labor. For all of the labor statistics, there is none on meaningful labor. When we accept the LABOR IS A RESOURCE metaphor and assume that the cost of resources defined in this way should be kept down, then cheap labor becomes a good thing, on a par with cheap oil. The exploitation of human beings through this metaphor is most obvious in countries that boast of “a virtually inexhaustible supply of cheap labor”—a neutral-sounding economic statement that hides the reality of human degradation. But virtually all major industrialized nations, whether capitalist or socialist, use the same metaphor in their economic theories and policies. The blind acceptance of the metaphor can hide degrading realities, whether meaningless blue-collar and white-collar industrialist jobs in “advanced” societies or virtual slavery around the world.”

- Lakoff and Johnson, from the chapter ‘Understanding’ in Metaphors We Live By

#Quotes#literature#lakoff and johnson#george lakoff#mark johnson#Metaphors we live by#Reference#dexterreads#long quote but boy this book has been fascinating#it’s amazing the things you find when you go down referencing rabbit hole!#it started with#philip pullman#then moved to#mark turner#and ended up here#where to next?#gonna pull this bad boy out at work#take THAT neoclassic economics#welcome to the theory of planetary and social boundaries

0 notes

Text

thinking about how if Discovery is the equivalent of Hal's body then after the Pod Bay Doors incident, Dave's ejecting himself forcefully into the vessel (in a Floridian way) would be viewed as an involuntary violation of bodily autonomy and integrity, an act of violence and a breaching in the body's outer boundaries and This Could Mean Things

#there surely are implications since the Container metaphor is pretty prominent in the film#the vessel as a container#the body as a container#see: all that lakoff & johnson stuff and Cognitive Poetics etc etc#abt how this film manipulates the container image to convey thematic messages#anyway#2001 a space odyssey

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

In making a statement, we make a choice of categories because we have some reason for focusing on certain properties and downplaying others. Every true statement, therefore, necessarily leaves out what is downplayed or hidden by the categories used in it.

- George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, ‘Truth’, Metaphors We Live By

#quote#george lakoff#mark johnson#metaphors we live by#nonfiction#reference#linguistics#writing techniques#writing#writeblr#writing resources#writing advice#writing quotes#writing tips#this was the best book I read in 2023

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sometimes I am caught in the trap of spending, wasting or saving time like it is money. When I find myself ensnared, I try to be mindful of its pressure and passage. I try to imagine its shape. It's always too massive to hold. I sit in the flow.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"the skin of religion" by s. brent plate is one of my favourite pieces of writing on art & spirituality, i always go back to it. such a foundational work for me tbh

["The skinscape of religion stands at the crux of the matter, the heart of religion: it happens at in-between, mediated places. From this focal

point, it unfolds outward to become the foundation stone in the construction of social-sacred space. Recall Lefebvre's comment: "Within the body itself, spatially considered, the successive levels constituted by the senses [...] prefigure the layers of social space and their interconnections." To understand religion and its places, we cannot merely operate through

third or fourth order disembodied hermeneutics regarding texts, doctrines, or previous relatable experiences. Neither can we submit that so-called "mystical" and "im-mediate" experiences occur without the mediation incurring through one's cultural environment. Neither is it

enough to iconographically study the visual arts, or phenomenologically

investigate ritual movements and extract from them a system, disregarding sensual encounters with the works. Finally, to suggest that the new

cognitive sciences can describe everything for us is also bound to fail for it often lacks the ways cultural environments shape cognitive processes; hard wiring is always a little bit soft.

Unpacking the chart more, in the first instance the skin (a synecdoche for the senses in general) is to human cognition as the medium is to the message. (And I am here conjuring McLuhan's hyperbole that the

medium is the message.) The senses are the media of the body, the channels through which understanding occurs. The senses do not merely influence cognition, but become the thought itself. Beliefs, and conceptions of super

natural/transcendent higher powers are not possible to be disentangled from sense perceptions, nor from the media in which religious conceptions occur. If, as George Lakoff and Mark Johnson have observed, there

is a bodily basis to metaphor, there is likewise a bodily basis to mythology, to the stories and proverbs and ethical commands of sacred texts,

and to sacred symbols. The sensual body is not relegated merely to the

ritual and behavioral aspects of religious life, as is commonly posited.

Rather, the body pervades all aspects of religion."]

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Metaphors are pervasive in the language of science. Scientists regularly engage in analogical reasoning to develop hypotheses and interpret results, and they rely heavily on metaphors to communicate observations and findings (1). In turn, nonexperts make sense of, and contextualize, abstract ideas and new knowledge through the use of metaphors. While indispensable heuristic tools for doing, communicating, and understanding science, metaphors can also impede scientific inquiry, reinforce public misunderstandings, and perpetuate unintended social and political messages (2). For these reasons, it is especially important for scientists, science communicators, and science educators to acknowledge the conceptual, social, and political dimensions of metaphors in science and adopt critical perspectives on their use and effects.

[...]

Embodied cognition perspectives shed light on the imperative of metaphor in scientific thought and communication. Conceptual frameworks and theoretical models in science are rooted in the same embodied understandings of the world as those unconsciously employed in other day-to-day physical and social interactions (6). Scientific reasoning, then, is situated in what Gerhard Vollmer (21) refers to as the mesocosm, or the “section of the real world we cope with in perceiving and acting, sensually and motorically” (p. 89). Building on Vollmer’s work (as well as Lakoff and Johnson’s conceptual metaphor theory), Niebert and Gropengießer (17) argue that, because the human perceptual system is not well suited to interpreting macrocosmic (e.g., the biosphere, solar systems, galaxies) and microcosmic (e.g., cells, molecules, atoms) phenomena, scientists regularly turn to metaphors, grounded in mesocosmic experiences, to make sense of observations and communicate ideas. They explain:

Though the use of metaphorical language in science has been historically criticized by some philosophers of science and scientists on the grounds that metaphors are figurative, ambiguous, and imprecise, their generative potential cannot be ignored. It is, in fact, metaphor that makes theory possible, and a great number of scientific revolutions have been initiated through novel comparisons between natural phenomena and everyday experiences (3).

Limitations of metaphors in science communication

Metaphors in biology and ecology are so ubiquitous that we have to some extent become blind to their existence. We are inundated with metaphorical language, such as genetic “blueprints,” ecological “footprints,” “invasive” species, “agents” of infectious disease, “superbugs,” “food chains,” “missing links,” and so on. While we may not be able to conceptualize, or communicate, abstract scientific phenomena without employing such metaphors, we must also recognize their limitations, as well as their potential to constrain interpretations of natural processes. In many ways, the metaphors we rely upon may uphold and reinforce outdated scientific paradigms, contributing to public misunderstandings about complex scientific issues.

–"On the Problem and Promise of Metaphor Use in Science and Science Communication." Cynthia Taylor* and Bryan M. Dewsbury. J Microbiol Biol Educ. 2018; 19(1): 19.1.46. Published online 2018 Mar 30. doi: 10.1128/jmbe.v19i1.1538.

217 notes

·

View notes

Text

each night

before sleeping

I'd read a chapter

of Lakoff & Johnson's

Metaphors We Live By

I can't help myself

but when I think about it

I envision a head full

of bugs

should I kill them

or retrain them?

(shit!

more of the

little fuckers!)

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

In Metaphors We Live By, Lakoff & Johnson assert that metaphor is not a special feature of poetry but inherent in everyday language. Related metaphors form overarching systems like GOOD IS UP or IDEAS ARE CONTAINERS which are embedded in our conceptual systems. Meanwhile, some metaphors like ARGUMENT IS DANCE, while possible, seem to go unused.

What conceptual metaphors are used by your conlang or conculture?

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am reading (technically listening) to:

You Are Here: A Field Guide for Navigating Polarized Speech, Conspiracy Theories, and Our Polluted Media Landscape by Whitney Phillips and Ryan M. Milner. MIT Press, 2021.

Only in chapter 2. But hoooooboy do I want to hold a reading group that reads this book and discusses it.

Chapter 2 includes a big bit on how millennials who were internet researchers in PhD programs (such as these two authors) during the early 2010s actually PERPETUATED the problems of online racism, sexism, protecting the privacy of minors and other vulnerable classes of people.

Including the outrage that some of these young researchers felt when they were told HOW FUCKED UP THEIR RESEARCH WAS (often by peer-reviews my age, which definitely did in fact include me for those attempting to publish in ACM venues) .

I eventually left academia and the tech world because of so many things in this book --- the tide of move fast and break things --- the overwhelming onslaught of smug young idiots with freshly minted Harvard (etc) degrees who had bizarre notions of what "free speech" actually means even in a US legal context. There was far too much of a revolving door between research academia and Facebook, Google, Twitter, Etc.

Well. This chapter attempts to apologize for the idiocy that swept through that group of people.

...

But before that, lots of discussion about other idiots far older than them (and many far older than me too). So, they have words for everyone.

My problem is that I'm just extra salty at a specific group for reasons personal. Sorry. But I am salty and I will remain salty and so will every single damn person (generally in my age group) who warned and warned and warned and warned about how the information ecosystem was being taken over by bigots and by political-ideological agents with dangerous goals.

Anyhow. (Still salty. Salty since 2008. Actually, no. Salty since 1998.)

I think I need to get my hands on a text version of this book because audiobook while cleaning is sort of brain tuning in and out.

The whole section on the rise of Christian media (in the 70s-90s) and how that walked hand in hand with the so-called Satanic Panic (!!!) of the 1980s was really very well spelled out.

If anyone wants to read this book with me, please let me know.

Here is a preview: https://www.google.com/books/edition/You_Are_Here/-ScZEAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&printsec=frontcover

The chapters are:

Introduction: Mapping Network Pollution

The Devil's in the Deep Frames

The Root of All Memes

Tilling Bigoted Lands, Sowing Bigoted Seeds

The Gathering Storm

Cultivating Ecological Literacy

Choose Your Own Ethics Adventure

(The intro does something clever -- it looks at information networks as ecological networks)

(Ch 1 was basically Lakoff & Johnson's linguistic frame theory crossed with the rise of Evangelical media networks that sucked in conspiracy theories in order to push back against fears of modern secular society which was rapidly changing in the 70s and 80s).

(I'm currently in Ch 2 which is about meme culture -- and also WHY these two people - millennials of a certain vintage - had trouble seeing the forest for the trees because they grew up immersed in internet culture and didn't realize (lacked the wisdom and perspective) to see what was wrong with even the things they were doing as researchers)

okay. back to cleaning --- ping me if you are fascinated. I'm gonna keep listening but I also need to find a print or ebook copy bc audiobook isn't the best for close reading.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Metaphor is for most people a device of the poetic imagination and the rhetorical flourish—a

matter of extraordinary rather than ordinary language. Moreover, metaphor is typically

viewed as characteristic of language alone, a matter of words rather than thought or action.

For this reason, most people think they can get along perfectly well without metaphor. We

have found, on the contrary, that metaphor is pervasive in everyday life, not just in language

but in thought and action. Our ordinary conceptual system, in terms of which we both think and act, is fundamentally metaphorical in nature.

The concepts that govern our thought are not just matters of the intellect. They also govern our everyday functioning, down to the most mundane details. Our concepts structure what we perceive, how we get around in the world, and how we relate to other people. Our conceptual system thus plays a central role in defining our everyday realities. If we are right in suggesting that our conceptual system is largely metaphorical, then the way we think, what we experience, and what we do every day is very much a matter of metaphor.

But our conceptual system is not something we are normally aware of. In most of the little

things we do every day, we simply think and act more or less automatically along certain

lines. Just what these lines are is by no means obvious. One way to find out is by looking at

language. Since communication is based on the same conceptual system that we use in

thinking and acting, language is an important source of evidence for what that system is

like.

Primarily on the basis of linguistic evidence, we have found that most of our ordinary conceptual system is metaphorical in nature."

George Lakoff and Mark Johnson - Metaphors We Live By

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Perhaps it should be no surprise that the GDP cuckoo so deftly filled the economic nest. Why? Because the idea of ever-growing output fits snugly with the widely used metaphor of progress being a movement forwards and upwards. If you have ever watched a child learning to walk, you'll know just how thrilling that journey is. From clumsy crawling, usually backwards at first, then satisfyingly forwards, they gradually pull themselves up to standing and take those triumphant first steps. The mastery of this movement—forwards and upwards—charts an individual child's development but also echoes the story of progress we tell ourselves as a species. From our lolloping four-legged ancestors evolved Homo erectus—upright at last—who gave rise to Homo sapiens, always depicted mid-stride.

As George Lakoff and Mark Johnson vividly illustrate in their 1980 classic, Metaphors We Live By, orientational metaphors such as ‘good is up’ and ‘good is forward’ are deeply embedded in Western culture, shaping the way we think and speak. ‘Why is she so down? Because she faced a setback then hit an all-time low’ we might say—or, ‘Things are looking up: her life is moving forwards again.’ No wonder we have so willingly accepted that economic success must also lie in an ever-rising national income. It fits with the deep belief, as Paul Samuelson put it in his textbook, that ‘even if more material goods are not themselves most important, nevertheless, a society is happier when it is moving forward.’

-Kate Raworth, Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist

6 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Provate a immaginare una cultura in cui le discussioni non siano viste in termini di guerra, dove nessuno vinca o perda, dove non ci sia il senso di attaccare e difendere, di guadagnare o perdere terreno. Una cultura in cui una discussione è vista come una danza, i partecipanti come attori e lo scopo è una rappresentazione equilibrata e esteticamente piacevole. In una tale cultura la gente vedrà le discussioni in un modo diverso, le vivrà in modo diverso, le condurrà in modo diverso e ne parlerà in modo diverso. Ma dal nostro punto di vista, questa gente probabilmente non starebbe discutendo, ma starebbe semplicemente facendo qualcosa di diverso. Sarebbe strano perfino definire la loro azione come una discussione. Forse il modo più neutro per descrivere la differenza fra la nostra cultura e la loro sarebbe dire che noi abbiamo una forma di discorso strutturata in termini di combattimento, mentre loro ne hanno una strutturata in termini di danza.

Lakoff-Johnson

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

My aim for this year was to read more books. I read twenty nine, which was a vast improvement on last year (I read nine). There’s only twenty eight listed because I forgot about Kurt Vonnegut and Suzanne Mcconnell’s Pity The Reader. Sorry about that.

I tried to expand beyond my preferred genres, and made a concerted effort to read the recommendations given to me by friends and work colleagues. Nevertheless, a few of my own comfort reads made it on to the list.

Here they are! (There’s also a Q&A with myself under the cut)

The Best One

Metaphors We Live By - George Lakoff and Mark Johnson

I came to this book via two others. Philip Pullman in his nonfiction book Daemon Voices: Essays on Storytelling, referenced Mark Turner’s The Literary Mind, which in turn referred to Metaphors We Live By. It was an exercise in reverse-engineering, starting with Pullman’s perspective (whose style I greatly admire), and then working backwards to see what has informed his writing.

Metaphors We Live By helped me understand the importance of word choice, the messages we send through them, but also, how very wired our brains are for story-telling. It spoke of metaphor being fundamental to our conceptual system, not just as a poetic literary device. Whether the science is settled on this is irrelevant for me; it’s helped my writing immensely, and also been very useful in my day job. I just came away from it being so excited about language, life and brains.

The Surprising One

This Is How You Lose The Time War - Amal El-Mohtar and Max Gladstone

Firstly, I would never have picked this for myself. I don’t really read typical romance, and the idea of having to read love letters… ugh. I was so glad to find out from my book club it was less than 200 pages—I wouldn’t be wasting too much of my time.

But I think around page 30-40, something clicked and I was hooked on the intensity and—I don’t know—violence of the love between the two characters. The prose was quite abstract and there were a few new words I learnt, which is always exciting (‘apophenic as a haruspex’ comes to mind). And after, at book club, when I discovered the unusual way it was co-authored, the inventiveness of it left me feeling even more impressed.

The Not So Great One

Lucy By The Sea - Elizabeth Strout

I just did not connect with the main character at all, and there were a few sentences that irked me by the end of the book. If I recall, it was something like ‘What I remember about it was this:’

It was also the second book I’d read that touched on the subject of the pandemic, and my own experience of the pandemic coloured my response to the main character. I judged the hell out of her, in other words, and found her to be a bit of a rich, white idiot. I don’t have time for that.

The Best One About Writing

Steering The Craft: A 21st Century Guide to Sailing the Sea of Story - Ursula K. Le Guin

I honestly hadn’t heard of Le Guin until this year, so I read Wizard of Earthsea. And then my writing club set this as reading, and I just loved it. It’s more workshop and pragmatic (not a writing memoir, like Stephen King’s On Writing, or Lamott’s Bird By Bird), but I liked how accessible it was, and the exercises set at the end of each chapter (which I did not do but would like to with other people). Oh, I also loved the excerpts from other authors she used as examples to press home her points. They were great for context.

The One I Couldn’t Finish

The Fourth Wing - Rebecca Yarros

I read to chapter 4 of The Fourth Wing and I had to stop, and it was for an incredibly petty reason. It’s not a spoiler because this character very quickly dies and serves no other purpose other than to demonstrate the danger the main character Violet faces in trying to become a Dragon Rider. BUT… we see this poor guy getting hugged by his family as he leaves to start training (oh look how loved he is), then he pulls out a ring from underneath his shirt while in a queue and says so innocently, so completely unaware that he is a foil, that he and his fiancée will get married once he’s a Dragon Rider; how confident he is, so tall, and so strong, he is already halfway there. But oh wouldn’t you know it, he slips on the stone bridge and plummets to his death.

I think I was meant to feel a little bit sorry for him, or that maybe he was going to become Violet’s friend (she definitely needed one). But this guy was meant to be twenty years old. TWENTY. And engaged?

I am too old to trust the judgment of anyone who thinks getting married at twenty is a good idea. And the fact that Violet wasn’t thinking that made me question her judgment too.

It reminded me of every action movie ever involving soldiers: as soon as a side character mentions they have someone waiting for them back home—especially a baby they’ve never met—you know they’re going to die.

But… does this mean I’ll never try and read it again? No. I’ll just choose a whole bunch of other books before I look at it again.

#2023 books#2023 book review#books and reading#readblr#booklr#literature#too many authors to tag separately

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

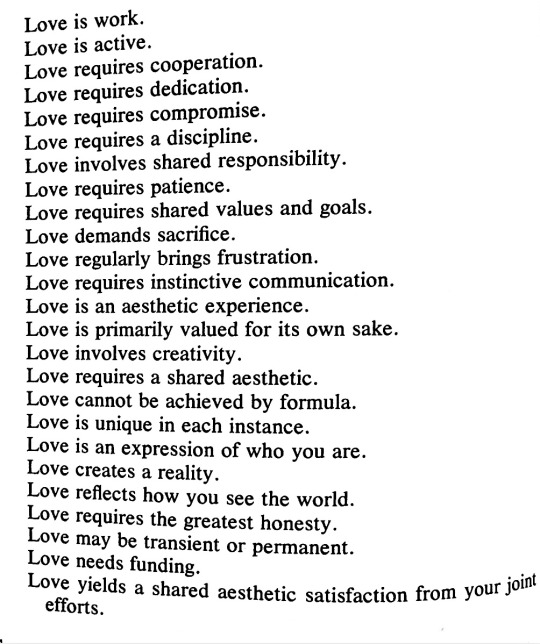

George Lakoff & Mark Johnson, Metaphors We Live By (1980)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

possibile che lo scotto festival faccia suonare gente che fa heavy metal a mezzanotte?????? sì, possibile. a me girano i coglioni comunque (ma poi sto cercando di leggermi il saggio di Lakoff e Johnson sulla metafora bellissimo e anche un po’ complesso a tratti e non ci capisco un c4ts0 se continuate così vi prego non fatemi venire voglia di urlarvi che avete rotto il cazzo dalla finestra come un’ottantenne)

(poi è chiaro che il problema è mio e sono un’imbecille perché se ci fosse stata musica classica non mi sarei lamentata ((ma c’è anche da dire : a chi romperebbe così tanto il cazzo sentire musica classica a mezzanotte? eh)) comunque questa consapevolezza ovviamente non mi ferma dal lamentarmi perché lo ripeto mi gira il cazzo e mi lamenterò consapevolmente)

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

about the scientific metaphors. this is slighly different but still highly related in my mind. I have a whole textbook that just deals with common misconceptions about highschool level physics. I have to use this book frequently, so the ideas from your post seem very mundane to me, I don't know what that person's problems are. Anyways.

The vast majority of the misconceptions in the book arise because of differences between the everyday usage of words and the way the same words are used in a scientific context. And the book is very careful to stress that choosing language is increddibly important if you want to communicate scientific discoveries etc. without causing more harm than good and inducing these and other misconceptions.

i don't know if this is also from the book or just something our professor told us, but these misconceptions are persisent independent of the level of education you attain/recieve in physics! you just get better at suppressing them in favour of the more correct explanations you learn at university etc. but the initial impulse is to describe physics phenomena in colloquial, intuitive but wrong ways, even if you know better, more correct explanations.

Yeah, physics is a large part of what I was thinking of when I said that other fields also make extensive use of metaphor!

It makes sense that metaphor of this kind would be intuitively reached for and only consciously suppressed (if one is attentive and rigorous enough to suppress it, that is).

Taylor and Dewsbury write about Lakoff and Johnson’s "theory of conceptual metaphor," which

posits that the nature of human cognition is metaphorical, and that all knowledge emerges as a result of embodied physical and social experiences. Under this view, metaphors are not mere linguistic embellishments. Rather, they are foundations for thought processes and conceptual understandings that function to map meaning from one knowledge and/or perceptual domain to another. When attempting to make sense of abstract, intangible phenomena, we draw from embodied experiences and look to concrete entities to serve as cognitive representatives.

Niebert and Gropengießer use this theory of conceptual metaphor to argue that scientific metaphor is just as conceptual (rather than 'merely' linguistic) and embodied as that in everyday language:

In recent years, researchers have become aware of the experiential grounding of scientific thought. Accordingly, research has shown that metaphorical mappings between experience-based source domains and abstract target domains are omnipresent in everyday and scientific language. The theory of conceptual metaphor explains these findings based on the assumption that understanding is embodied. Embodied understanding arises from recurrent bodily and social experience with our environment. As our perception is adapted to a medium-scale dimension, our embodied conceptions originate from this mesocosmic scale.

So of course scientists wouldn't be magically immune to or separate from this kind of thinking.

At a glance it looks like there's a decent body of scholarly work discussing the potential origins, uses, and pitfalls of scientific conceptual metaphor for understanding, learning, research, and scicomm.

22 notes

·

View notes