#like no system is without its flaws and china is no exceptions ESPECIALLY with it being at such risk of revisionism like the USSR but like

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

When I think about it the perspective Americans have on china is completely baffling like they've deluded themselves so deep into thinking they're the centre of everything and always have been that you have this barely reaching 300 year old country thinking they know better than what's been one of the strongest cultural and economic powerhouses of the last 5000 years because they've become a world powerhouse after winning a few wars and have made groundbreaking "discoveries" like "using babies as bait to hunt alligators because their skin is a different colour is bad, actually. Turns out they might actually be people?" through civil war and riots lasting over 3/4ths of it's lifespan in what's not even a 1/10 of the latters history

#gu6chan's musings#like no system is without its flaws and china is no exceptions ESPECIALLY with it being at such risk of revisionism like the USSR but like#c'mon man#if it's between the oldest civilizations in the world who was so advanced it had literal myths written about it in the middle ages and then#the not even 300 year old country that's only even keeping itself together through brutalization and subjugation of other countries to its#every whim and command bc it won a war 79 years ago#im gonna at LEAST think the older one knows what its doing!!!! its seen it all and has done this shit before lmao#americans love to think they're the only competent people in the universe and THAT'S how they got to where they are but forget it's#literally only a baby#like#just give it time you'll find yourself in the trenches soon enough#it's ironically some of the oldest and 'experienced' civilisations on earth America has the most ire towards and i really do wonder about it#sometimes

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 1949, General Chiang Kai-shek moved his Nationalist Party, the Kuomintang (KMT), to the island and established the Republic of China there. Ever since, the People’s Republic of China has seen Taiwan as its ideological enemy, an irritating reminder that not all Chinese wish to be united under the leadership of the Communist Party.

Sometimes Chinese pressure on Taiwan has been military, involving the issuing of threats or the launching of missiles. But in recent years, China has combined those threats and missiles with other forms of pressure, escalating what the Taiwanese call “cognitive warfare”: not just propaganda but an attempt to create a mindset of surrender. This combined military, economic, political, and information attack should by now be familiar, because we have just watched it play out in Eastern Europe. Before 2014, Russia had hoped to conquer Ukraine without firing a shot, simply by convincing Ukrainians that their state was too corrupt and incompetent to survive. Now it is Beijing that seeks conquest without a full-scale military operation, in this case by convincing the Taiwanese that their democracy is fatally flawed, that their allies will desert them, that there is no such thing as a “Taiwanese” identity.

Taiwanese government officials and civic leaders are well aware that Ukraine is a precedent in a variety of ways. During a recent trip to Taiwan’s capital, Taipei, I was told again and again that the Russian invasion of Ukraine was a harbinger, a warning. Although Taiwan and Ukraine have no geographic, cultural, or historical links, the two countries are now connected by the power of analogy. Taiwanese Foreign Minister Joseph Wu told me that the Russian invasion of Ukraine makes people in Taiwan and around the world think, “Wow, an authoritarian is initiating a war against a peace-loving country; could there be another one? And when they look around, they see Taiwan.”

But there is another similarity. So powerful were the Russian narratives about Ukraine that many in Europe and America believed them. Russia’s depiction of Ukraine as a divided nation of uncertain loyalties convinced many, prior to February, that Ukrainians would not fight back. Chinese propaganda narratives about Taiwan are also powerful, and Chinese influence on the island is both very real and very divisive. Most people on the island speak Mandarin, the dominant language in the People’s Republic, and many still have ties of family, business, and cultural nostalgia to the mainland, however much they reject the Communist Party. But just as Western observers failed to understand how seriously the Ukrainians were preparing—psychologically as well as militarily—to defend themselves, we haven’t been watching as Taiwan has begun to change too.

Although the Taiwanese are regularly said to be too complacent, too closely connected to the People’s Republic, not all Taiwanese even have any personal links to the mainland. Many descend from families that arrived on the island long before 1949, and speak languages other than Mandarin. More to the point, large numbers of Taiwanese, whatever their background, feel no more nostalgia for mainland China than Ukrainians feel for the Soviet Union. The KMT’s main political opponent, the Democratic Progressive Party, is now the usual political home for those who don’t identify as anything except Taiwanese. But whether they are KMT or DPP supporters (the Taiwanese say “blue” or “green”), whether they participate in angry online debates or energetic rallies, the overwhelming majority now oppose the old “one country, two systems” proposal for reunification. Especially since the repression of the Hong Kong democracy demonstrations, millions of the island’s inhabitants understand that the Chinese war on their society is not something that might happen in the future but is something that is already well under way.

Like the Ukrainians, the Taiwanese now find themselves on the front line of the conflict between democracy and autocracy. They, too, are being forced to invent strategies of resistance. What happens there will eventually happen elsewhere: China’s leaders are already seeking to expand their influence around the world, including inside democracies. The tactics that the Taiwanese are developing to fight Chinese cognitive warfare, economic pressure, and political manipulation will eventually be needed in other countries too.

— China’s War Against Taiwan Has Already Started

#anne applebaum#china's war against taiwan has already started#history#current events#military history#politics#taiwanese politics#chinese politics#communism#propaganda#psychological warfare#culture#identity#chinese civil war#china#taiwan#republic of china#hong kong#chiang kai-shek#kuomintang#democratic progressive party

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

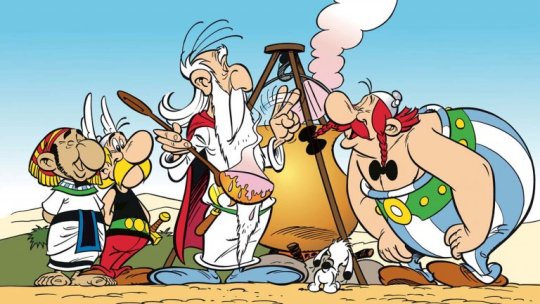

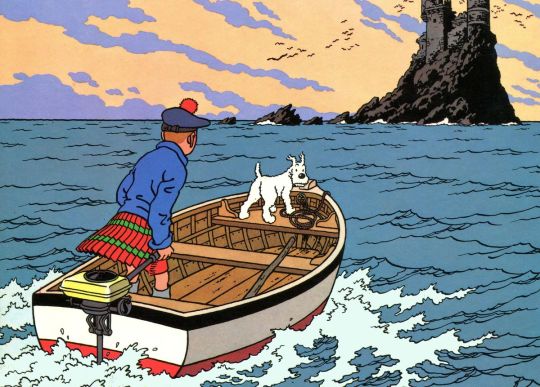

Anonymous asked: I noticed you did post to acknowledge the death of Uderzo, the co-creator of the Asterix comics. I have to ask Tintin or Asterix? Which one do you prefer?

It’s like asking Stones or Beatles? I love both but for different reasons. I would hate to choose between the two.

Both Tintin and Asterix were the two halves of a comic dyad of my childhood. Whether it was India, China, Hong Kong, Japan, or the Middle East the one thing that threads my childhood experience of living in these countries was finding a quiet place in the home to get lost reading Asterix and Tintin.

Even when I was eventually carted off to boarding school back in England I took as many of my Tintin and Asterix comics books with me as I could. They became like underground black market currency to exchange with other girls for other things like food or chocolates sent by parents and other illicit things like alcohol. Having them and reading them was like having familiar friends close by to make you feel less lonely in new surroundings and survive the bear pit of other girls living together.

If you asked my parents - especially my father - he would say Tintin hands down. He has - and continues to have in his library at home - a huge collection of Tintin comic books in as many different language translations as possible. He’s still collecting translations of each of the Tintin books in the most obscure languages he can find. I have both all the Tintin comic books - but only in English and French translations, and the odd Norwegian one - as well as all the Asterix comic books (only in English and French).

Speaking for myself I would be torn to decide between the two. Each have their virtues and I appreciate them for different reasons.

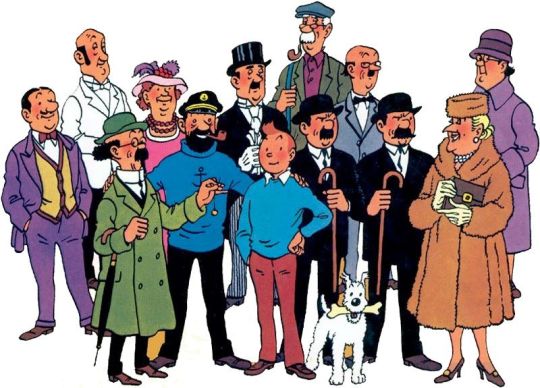

Tintin was truly about adventure that spoke deeply to me. Tintin was always a good detective story that soon turned to a travel adventure. It has it all: technology, politics, science and history. Of course the art is more simpler, but it is also cleaner and translates the wondrous far-off locations beautifully and with a sense of awe that you don’t see in the Asterix books. Indeed Hergé was into film-noir and thriller movies, and the panels are almost like storyboards for The Maltese Falcon or African Queen.

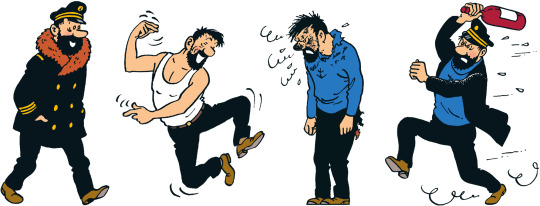

The plot lines of Tintin are intriguing rather than overly clever but the gallery of characters are much deeper, more flawed and morally ambiguous. Take Captain Haddock I loved his pullover, his strangely large feet, his endless swearing and his inability to pass a bottle without emptying it. He combined bravery and helplessness in a manner I found irresistible.

I’ve read that there is a deeply Freudian reading to the Tintin books. I think there is a good case for it. The Secret of the Unicorn and Red Rackham's Treasure are both about Captain Haddock's family. Haddock's ancestor, Sir Francis Haddock, is the illegitimate son of the French Sun King – and this mirrors what happened in Hergé's family, who liked to believe that his father was the illegitimate son of the Belgian king. This theme played out in so many of the books. In The Castafiore Emerald, the opera singer sings the jewel song from Faust, which is about a lowly woman banged up by a nobleman – and she sings it right in front of Sir Francis Haddock, with the captain blocking his ears. It's like the Finnegans Wake of the cartoon. Nothing happens - but everything happens.

Another great part is that the storylines continue on for several albums, allowing them to be more complex, instead of the more simplistic Asterix plot lines which are always wrapped up nicely at the end of each book.

Overall I felt a great affinity with Tintin - his youthful innocence, wanting to solve problems, always resourceful, optimistic, and brave. Above all Tintin gave me wanderlust. Was there a place he and Milou (Snowy) didn’t go to? When they had covered the four corners of the world Tintin and Milou went to the moon for heaven’s sake!

What I loved about Asterix was the style, specifically Uderzo’s visual style. I liked Hergé’s clean style, the ligne claire of his pen, but Asterix was drawn as caricature: the big noses, the huge bellies, often being prodded by sausage-like fingers. This was more appealing to little children because they were more fun to marvel at.

In particular I liked was the way Uderzo’s style progressed with each comic book. The panels of Asterix the Gaul felt rudimentary compared to the later works and by the time Asterix and Cleopatra, the sixth book to be published, came out, you finally felt that this was what they ought to look like. It was an important lesson for a child to learn: that you could get better at what you did over time. Each book seemed to have its own palette and perhaps Uderzo’s best work is in Asterix in Spain.

I also feel Asterix doesn’t get enough credit for being more complex. Once you peel back the initial layers, Asterix has some great literal depth going on - puns and word play, the English translation names are all extremely clever, there are many hidden details in the superb art to explore that you will quite often miss when you initially read it and in a lot of the truly classic albums they are satirising a real life country/group/person/political system, usually in an incredibly clever and humorous way.

What I found especially appealing was that it was also a brilliant microcosm of many classical studies subjects - ancient Egypt, the Romans and Greek art - and is a good first step for young children wanting to explore that stuff before studying it at school.

What I discovered recently was that Uderzo was colour blind which explains why he much preferred the clear line to any hint of shade, and it was that that enabled his drawings to redefine antiquity so distinctively in his own terms. For decades after the death of René Goscinny in 1977, Uderzo provided a living link to the golden age of the greatest series of comic books ever written: Paul McCartney to Goscinny’s John Lennon. Uderzo, as the Asterix illustrator, was better able to continue the series after Goscinny’s death than Goscinny would have been had Uderzo had died first, and yet the later books were, so almost every fan agrees, not a patch on the originals: very much Wings to the Beatles. What elevated the cartoons, brilliant though they were, to the level of genius was the quality of the scripts that inspired them. Again and again, in illustration after illustration, the visual humour depends for its full force on the accompaniment provided by Goscinny’s jokes.

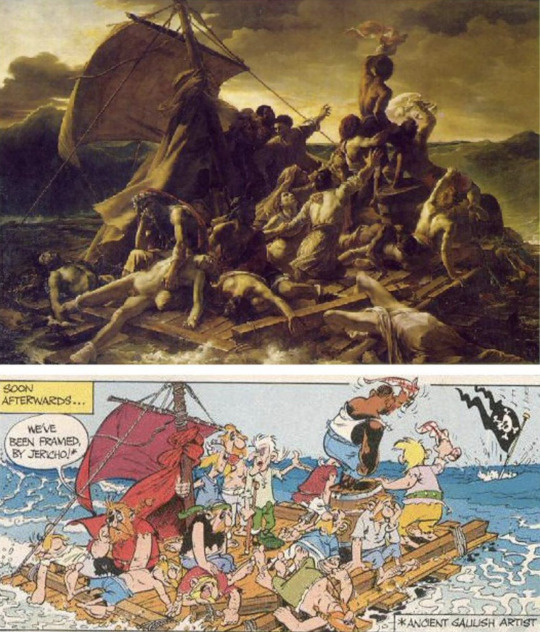

Here below is a great example:

There’s a lot of genius in this. Uderzo copied Theodore Géricault’s iconic ‘Raft of the Medusa’ 1818 painting in ‘Asterix The Legionary’. The painting is generally regarded as an icon of Romanticism. It depicts an event whose human and political aspects greatly interested Géricault: the wreck of a French frigate, Medusa, off the coast of Senegal in 1816, with over 150 soldiers on board. But Anthea Bell’s translation of Goscinny’s text (including the pictorial and verbal pun ‘we’ve been framed, by Jericho’) is really extraordinary and captures the spirit of the Asterix cartoons perfectly.

This captures perfectly my sense of humour as it acknowledges the seriousness of life but finds humour in them through a sly cleverness and always with a open hearted joy. There is no question that if humour was the measuring yard stick then Asterix and not Tintin would win hands down.

It’s also a mistake to think that the world of Asterix was insular in comparison to the amazing countries Tintin had adventures. Asterix’s world is very much Europe.

Every nationality that Asterix encounters is gently satirised. No other post-war artistic duo offered Europeans a more universally popular portrait of themselves, perhaps, than did Goscinny and Uderzo. The stereotypes with which he made such affectionate play in his cartoons – the haughty Spaniard, the chocolate-loving Belgian, the stiff-upper-lipped Briton – seemed to be just what a continent left prostrate by war and nationalism were secretly craving. Many shrewd commentators believe that during the golden age when Goscinny was still alive to pen the scripts, that it was a fantasy on French resistance during occupation by Nazi Germany. Uderzo lived through the occupation and so there is truth in that. Perhaps this is why the Germans are the exceptions as they are treated unsympathetically in Asterix and the Goths, and why quite a few of the books turn on questions of loyalty and treachery.

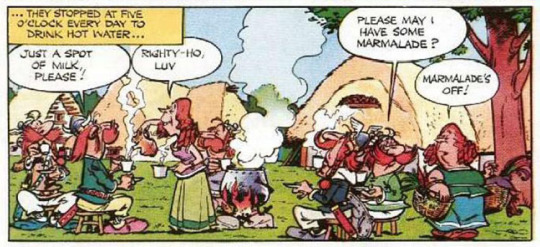

Even the British are satirised with an affection that borders on love: the worst of the digs are about our appalling cuisine (everything is boiled, and served with mint sauce, and the beer is warm), but everything points to the Gauls’ and the Britons’ closeness. They have the same social structure, even down to having one village still holding out against the Romans; the crucial and extremely generous difference being that the Britons do not have a magic potion to help them fight. Instead they have tea, introduced to them by Getafix, via Asterix, which gives them so much of a psychological boost that it may as well have been the magic potion.

I re-read ‘Asterix in Britain’ (Astérix chez les Bretons) in the light of the 2016 Brexit referendum result and felt despaired that such a playful and respectful portrayal of this country was not reciprocated. Don’t get me wrong I voted for Brexit but I remain a staunch Europhile. It made me violently irritated to see many historically illiterate pro-Brexit oiks who mistakenly believed the EU and Europe were the same thing. They are not. One was originally a sincere band aid to heal and bring together two of the greatest warring powers in continental Europe that grotesquely grew into an unaccountable bureaucratic manager’s utopian wet dream, and the other is a cradle of Western achievement in culture, sciences and the arts that we are all heirs to.

What I loved about Asterix was that it cut across generations. As a young girl I often retreated into my imaginary world of Asterix where our family home had an imaginary timber fence and a dry moat to keep the world (or the Romans) out. I think this was partly because my parents were so busy as many friends and outsiders made demands on their time and they couldn’t say no or they were throwing lavish parties for their guests. Family time was sacred to us all but I felt especially miffed if our time got eaten away. Then, as I grew up, different levels of reading opened up to me apart from the humour in the names, the plays on words, and the illustrations. There is something about the notion of one tiny little village, where everybody knows each other, trying to hold off the dark forces of the rest of the world. Being the underdog, up against everyone, but with a sense of humour and having fun, really resonated with my child's eye view of the world.

The thing about both Asterix and Tintin books is that they are at heart adventure comics with many layers of detail and themes built into them. For children, Asterix books are the clear winner, as they have much better art and are more fantastical. Most of the bad characters in the books are not truly evil either and no-one ever dies, which appeals hugely to children. For older readers, Tintin has danger, deeper characters with deep political themes, bad guys with truly evil motives, and even deaths. It’s more rooted in the real world, so a young reader can visualise themselves as Tintin, travelling to these real life places and being a hero.

As I get older and re-read Asterix and Tintin from time to time I discover new things.

From Asterix, there is something about the notion of one tiny little village, where everybody knows each other, trying to hold off the dark forces of the rest of the world. Being the underdog, up against everyone, but with a sense of humour and having fun, really resonated with my child's eye view of the world. In my adult world it now makes me appreciate the value of family, friends, and community and even national identity. Even as globalisation and the rise of homogenous consumerism threatens to envelope the unique diversity of our cultures, like Asterix, we can defend to the death the cultural values that define us but not through isolation or by diminishing the respect due to other cultures and their cultural achievements.

From Tintin I got wanderlust. This fierce even urgent need to travel and explore the world was in part due to reading the adventures of Tintin. It was by living in such diverse cultures overseas and trying to get under the skin of those cultures by learning their languages and respecting their customs that I realised how much I valued my own heritage and traditions without diminishing anyone else.

So I’m sorry but I can’t choose one over the other, I need both Asterix and Tintin as a dyad to remind me that the importance of home and heritage is best done through travel and adventure elsewhere.

Thanks for your question.

297 notes

·

View notes

Text

How does a movement evolve: can there be a successful bad feminist?

In the age of #metoo and #timesup, I personally wonder just how potent the movement will be in the future if feminists aren't able to agree with one another in the present. Feminism appears split at the seams but these times, where the agents of an agenda are at conflict with how to define themselves, often make for the strongest coalition of unified minds. Forged like a sword at the hands of perfectionist blacksmith, any movement will grow more firm by each side of the schism holding the other to the fire. As a mere man, from the outside, it is not my battle to coach feminism. My job is to be an aid to the movement and to support where I can.

Among the schism, exemplifying its nature, comes this recent piece by Margaret Atwood. In The Globe and Mail, the acclaimed dystopian author penned her own doubts with her version of feminism and how she fits within the fluid structure of it:

"------It seems that I am a "Bad Feminist." I can add that to the other things I've been accused of since 1972, such as climbing to fame up a pyramid of decapitated men's heads (a leftie journal), of being a dominatrix bent on the subjugation of men (a rightie one, complete with an illustration of me in leather boots and a whip) and of being an awful person who can annihilate – with her magic White Witch powers – anyone critical of her at Toronto dinner tables. I'm so scary! And now, it seems, I am conducting a War on Women, like the misogynistic, rape-enabling Bad Feminist that I am.

What would a Good Feminist look like, in the eyes of my accusers?

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

My fundamental position is that women are human beings, with the full range of saintly and demonic behaviours this entails, including criminal ones. They're not angels, incapable of wrongdoing. If they were, we wouldn't need a legal system.

Nor do I believe that women are children, incapable of agency or of making moral decisions. If they were, we're back to the 19th century, and women should not own property, have credit cards, have access to higher education, control their own reproduction or vote. There are powerful groups in North America pushing this agenda, but they are not usually considered feminists.

Furthermore, I believe that in order to have civil and human rights for women there have to be civil and human rights, period, including the right to fundamental justice, just as for women to have the vote, there has to be a vote. Do Good Feminists believe that only women should have such rights? Surely not. That would be to flip the coin on the old state of affairs in which only men had such rights.

So let us suppose that my Good Feminist accusers, and the Bad Feminist that is me, agree on the above points. Where do we diverge? And how did I get into such hot water with the Good Feminists?

In November of 2016, I signed – as a matter of principle, as I have signed many petitions – an Open Letter called UBC Accountable, which calls for holding the University of British Columbia accountable for its failed process in its treatment of one of its former employees, Steven Galloway, the former chair of the department of creative writing, as well as its treatment of those who became ancillary complainants in the case. Specifically, several years ago, the university went public in national media before there was an inquiry, and even before the accused was allowed to know the details of the accusation. Before he could find them out, he had to sign a confidentiality agreement. The public – including me – was left with the impression that this man was a violent serial rapist, and everyone was free to attack him publicly, since under the agreement he had signed, he couldn't say anything to defend himself. A barrage of invective followed.

But then, after an inquiry by a judge that went on for months, with multiple witnesses and interviews, the judge said there had been no sexual assault, according to a statement released by Mr. Galloway through his lawyer. The employee got fired anyway. Everyone was surprised, including me. His faculty association launched a grievance, which is continuing, and until it is over, the public still cannot have access to the judge's report or her reasoning from the evidence presented. The not-guilty verdict displeased some people. They continued to attack. It was at this point that details of UBC's flawed process began to circulate, and the UBC Accountable letter came into being.

A fair-minded person would now withhold judgment as to guilt until the report and the evidence are available for us to see. We are grownups: We can make up our own minds, one way or the other. The signatories of the UBC Accountable letter have always taken this position. My critics have not, because they have already made up their minds. Are these Good Feminists fair-minded people? If not, they are just feeding into the very old narrative that holds women to be incapable of fairness or of considered judgment, and they are giving the opponents of women yet another reason to deny them positions of decision-making in the world.

A digression: Witch talk. Another point against me is that I compared the UBC proceedings to the Salem witchcraft trials, in which a person was guilty because accused, since the rules of evidence were such that you could not be found innocent. My Good Feminist accusers take exception to this comparison. They think I was comparing them to the teenaged Salem witchfinders and calling them hysterical little girls. I was alluding instead to the structure in place at the trials themselves.

There are, at present, three kinds of "witch" language. 1) Calling someone a witch, as applied lavishly to Hillary Clinton during the recent election. 2) "Witchhunt," used to imply that someone is looking for something that doesn't exist. 3) The structure of the Salem witchcaft trials, in which you were guilty because accused. I was talking about the third use.

This structure – guilty because accused – has applied in many more episodes in human history than Salem. It tends to kick in during the "Terror and Virtue" phase of revolutions – something has gone wrong, and there must be a purge, as in the French Revolution, Stalin's purges in the USSR, the Red Guard period in China, the reign of the Generals in Argentina and the early days of the Iranian Revolution. The list is long and Left and Right have both indulged. Before "Terror and Virtue" is over, a great many have fallen by the wayside. Note that I am not saying that there are no traitors or whatever the target group may be; simply that in such times, the usual rules of evidence are bypassed.

Such things are always done in the name of ushering in a better world. Sometimes they do usher one in, for a time anyway. Sometimes they are used as an excuse for new forms of oppression. As for vigilante justice – condemnation without a trial – it begins as a response to a lack of justice – either the system is corrupt, as in prerevolutionary France, or there isn't one, as in the Wild West – so people take things into their own hands. But understandable and temporary vigilante justice can morph into a culturally solidified lynch-mob habit, in which the available mode of justice is thrown out the window, and extralegal power structures are put into place and maintained. The Cosa Nostra, for instance, began as a resistance to political tyranny.

The #MeToo moment is a symptom of a broken legal system. All too frequently, women and other sexual-abuse complainants couldn't get a fair hearing through institutions – including corporate structures – so they used a new tool: the internet. Stars fell from the skies. This has been very effective, and has been seen as a massive wake-up call. But what next? The legal system can be fixed, or our society could dispose of it. Institutions, corporations and workplaces can houseclean, or they can expect more stars to fall, and also a lot of asteroids.

If the legal system is bypassed because it is seen as ineffectual, what will take its place? Who will be the new power brokers? It won't be the Bad Feminists like me. We are acceptable neither to Right nor to Left. In times of extremes, extremists win. Their ideology becomes a religion, anyone who doesn't puppet their views is seen as an apostate, a heretic or a traitor, and moderates in the middle are annihilated. Fiction writers are particularly suspect because they write about human beings, and people are morally ambiguous. The aim of ideology is to eliminate ambiguity.

The UBC Accountable letter is also a symptom – a symptom of the failure of the University of British Columbia and its flawed process. This should have been a matter addressed by Canadian Civil Liberties or B.C. Civil Liberties. Maybe these organizations will now put up their hands. Since the letter has now become a censorship issue – with calls being made to erase the site and the many thoughtful words of its writers – perhaps PEN Canada, PEN International, CJFE and Index on Censorship may also have a view.

The letter said from the beginning that UBC failed accused and complainants both. I would add that it failed the taxpaying public, who fund UBC to the tune of $600-million a year. We would like to know how our money was spent in this instance. Donors to UBC – and it receives billions of dollars in private donations – also have a right to know.

In this whole affair, writers have been set against one another, especially since the letter was distorted by its attackers and vilified as a War on Women. But at this time, I call upon all – both the Good Feminists and the Bad Feminists like me – to drop their unproductive squabbling, join forces and direct the spotlight where it should have been all along – at UBC. Two of the ancillary complainants have now spoken out against UBC's process in this affair. For that, they should be thanked.

Once UBC has begun an independent inquiry into its own actions – such as the one conducted recently at Wilfrid Laurier University – and has pledged to make that inquiry public, the UBC Accountable site will have served its purpose. That purpose was never to squash women. Why have accountability and transparency been framed as antithetical to women's rights?

A war among women, as opposed to a war on women, is always pleasing to those who do not wish women well. This is a very important moment. I hope it will not be squandered.------"

1 note

·

View note

Text

Why the US Sucks at Building Public Transit

American cities are facing a transportation crisis. There’s terrible traffic. Public transit doesn’t work or go where people need it to. The cities are growing, but newcomers are faced with the prospects of paying high rents for reasonable commutes or lower rents for dreary, frustrating daily treks. Nearly all Americans, including those in cities, face a dire choice: spend thousands of dollars a year owning a car and sitting in traffic, or sacrifice hours every day on ramshackle public transit getting where they need to go. Things are so broken that, increasingly, they do both. Nationwide, three out of every four commuters drive alone. The rate in metro areas is not much different.

“Without an integrated system of transit in our metropolitan areas the great anticipated growth will become a dream that will fail,” predicted Ralph Merritt, general manager of the Los Angeles Metropolitan Transportation Authority, “because people cannot move freely, safely, rapidly, and economically from where they live to where they work.”

Although Merritt’s words could just as well apply today, he said them 66 years ago in 1954. This is a crisis facing American cities right now in 2020, but it’s an old crisis. The only thing that has changed is the problem has gotten worse.

Like most crises, there is no single cause. Our cities, and our federal government, have made a lot of mistakes. Some were obvious at the time, others only in hindsight, but most have been a combination of the two. We keep doing things that stopped being good ideas a long time ago.

Many of those mistakes have to do with housing policy, which is inextricably linked to transportation policy. But the most obvious cause of our transportation crisis is a simple one: America sucks at building public transportation.

Why is this? Why does the U.S. suck at building good, useful public transit?

It’s a question that has vexed me for years. Just when I think I’ve figured it out, some other facet I had never previously considered comes to my attention. I have spoken to a dozen transit experts and historians. I have read several histories of American mass transportation policy written by independent scholars as well as government agencies. I've scoured federal archives and interviewed employees of transit agencies planning their own big projects. I’ve analyzed budgets and construction costs and compared them to our international peers. The tangle of American governmental dysfunction is so profound, digging into it can feel like undoing a rubber band ball with your teeth.

But the failure itself is simple and obvious. It’s apparent to anyone who has traveled abroad in the last several decades. Whether it’s traditional subway and commuter rail systems, modern streetcars and light rails, high-speed intercity rail, or even the humble bus with dedicated lanes and train-like stops, the U.S. lags perilously behind. It is a national embarrassment and a major reason our cities are less pleasant, more expensive places to live.

Just to name a few recent accomplishments abroad lacking an American parallel: Paris has the Grand Paris Express, 120 miles and 68 stations of new lines, plus a host of new trams and express bus lines with dedicated lanes. Moscow is building 98 new miles and 79 new stations for its Metro. At two years delayed and three billion pounds over budget, London’s Crossrail qualifies as a scandalous by European standards. But when it opens—perhaps in 2021—it will provide 73 miles of new rapid, frequent trains across greater London, including right through the center of the city. Since the 1990s, Madrid’s Metro has added more than 100 kilometers to its system. There are numerous examples of highly functioning and useful public transit systems in Latin America, which also invented the Bus Rapid Transit, a hybrid system with enclosed stops and dedicated lanes. China, which had basically no rapid transit through 1990, now has 25 cities with comprehensive rail systems, including seven of the world’s 12 largest metro networks by length.

Source: Yonah Freemark. Chart by Cathryn Virginia

Of course, China’s massive central government means it can build what it wants when and where it wants. But it’s hardly just China and other authoritarian regimes embarrassing the U.S. when it comes to transit construction. Consider, for example, high speed rail, or trains between cities capable of going faster than 120 mph. Over the last 30 years, almost two dozen countries have built true high-speed rail networks, according to transportation expert Yonah Freemark. The U.S. has a grand total of 34 miles of high-speed track.

China is not on this graph because they're literally off the charts (sorry). Data source: Yonah Freemark. Chart by Cathryn Virginia

This isn’t to say the U.S. has built nothing in the same time period. Freemark, one of the most thorough chroniclers of American transportation projects, calculated that the U.S. spent more than $47 billion on 1,200 miles of new and expanded transit lines in the decade from 2010 to 2019 (most of that mileage has been on bus routes).

That may sound like a lot, and at first glance it can seem like the U.S. has made some progress. There are now 93 miles of light rail in Dallas, 60 miles in Portland, and 87.5 combined light and commuter rail miles in Denver. Los Angeles, Seattle, Houston, San Diego, Sacramento, Phoenix, and others can cite similar improvements. For all their flaws, these are transit systems that didn’t exist 40 years ago.

But these systems, with the possible exception of Portland’s, do have one thing in common: they’re not especially useful because they’re not big enough and don’t go where people need them to. There is no perfect metric to evaluate the usefulness of a transit system, but, the most obvious failure is these systems haven’t changed their cities. Few people rely on them. As a general rule, these light rail systems serve fewer than 30 million passenger trips a year (LA has more, although as a percentage of the metro area population its usage is in line with other new systems). Even in cities of millions of people like Houston and Phoenix, light rail systems serve fewer than half that. Meanwhile, the Grand Paris Express and Crossrail are projecting ridership in the millions per day.

The basic truth is nearly everyone still depends on their cars even in cities with soul-destroying traffic. By any definition, the last half-century of American transportation policy has been a dismal failure.

Ultimately, this is not about trains and buses. This is about a political system uninterested in reform, a system unconcerned with fixing what’s broken.

But the problem isn’t limited just to new systems with growing pains. Older American cities with legacy systems have barely expanded to meet the growing footprint of their metro areas, as London and Paris are. The subway maps of New York, Boston, Chicago, and Philadelphia look almost identical as they did in 1950; in some cases, they’ve actually shrunk.

Simply put, the U.S. builds less public transit per urban dweller than its peer countries. Freemark found U.S. cities “added an average of fewer than 2 miles of urban bus improvements per million inhabitants—and fewer than 1 mile of rail improvements.” Meanwhile, France added 10 miles of buses and 3 miles of rail per million inhabitants in that same time period.

There is, of course, no simple answer why our transportation systems are broken, in much the same way there’s no simple answer to why our healthcare system is broken or why our criminal justice system is broken, beyond, as Freemark put it, that our “dysfunctional, irascible political system [is] woefully unprepared to commit to anything particularly significant.”

Ultimately, this is not about trains and buses. This is about a political system uninterested in reform, a system unconcerned with fixing what’s broken. If we can understand how politics failed American transportation systems, perhaps we can make the solution part of broader reform that must occur if American government is to start addressing the needs of the people in all aspects of life, from health care to criminal justice to housing to employment law to digital privacy to climate change.

It’s more important to understand all those causes now than ever. Building lots of public transit fast is, according to the Department of Transportation, a key front in the fight against climate change, because transportation accounts for about 30 percent of U.S. emissions, most of that from private automobiles. Are we up for the task? Can we, as a nation, build the infrastructure we desperately need to create a more sustainable world?

Do you work for the Federal Transit Administration or a local transit agency? What are the challenges you face in getting public transit projects done? We'd love to hear from you. Using a non-work phone or computer, you can contact Aaron Gordon at [email protected] or [email protected].

The answer to that question depends on understanding why we have failed so miserably up to this point. While researching the question of why our public transit is so bad, I’ve encountered a series of partial but ultimately incomplete explanations. If you don’t feel like descending into the transit nerd tunnel with me, here’s the tl;dr version:

Everything costs too much

We build highways instead

We don't plan well

People don't trust the government to build things so they vote against projects under the assumption they will be executed poorly and waste taxpayer dollars

We don't give transit agencies enough money to run good service which erodes political support to have more of it

There are too many agencies at all levels of government, especially at the local level, and not enough coordination between them

Our newer cities are sprawled out which makes good transit hard, and our older cities are too paralyzed by political dysfunction to expand the systems they have

As a result of generations of privatization efforts by all levels of government, in the rare event we do actually get to build stuff there is not enough expertise within the agencies to do it well

The good news is all of this is fixable. At least, that’s what Freemark believes. “The idea that we can’t build new systems is ridiculous,” he told me in an interview. “We just have to assemble the political interest and excitement to make those things happen.”

“There Was Always A Subsidy Somewhere”

Before we go any further, it’s important to dispel a pernicious myth that has perpetuated in the United States about public transportation. This is the idea that transit ought to pay for itself just like any other business.

This was a popular position in local, state, and federal governments until the mid-20th century. It is also the founding principle of public authorities, like the Metropolitan Transportation Authority that oversees much of greater New York’s transit, which are legally required to balance their budgets every year. The concept is that well-run public transit ought to be profitable.

The problem—well, just one of the problems—with this philosophy is it’s based on a totally fictitious belief that the New York City subway once was a good business, or that the Boston subway once was a self-sustaining operation.

This was never true. “There was always a subsidy somewhere,” Jeff Davis, senior fellow at the think tank Eno Transportation Center said. Streetcars and early subways were paid for by wealthy financiers, real estate speculators, and electric companies, among others. The speculators bought cheap land on the outskirts of town and then built transportation that went there before selling the land for a tidy profit. Back in the day when lights were the main use of electricity, electric companies faced a huge surge at night. Streetcars were a convenient use of that excess electric capacity during the day when demand was lower. And, as the 19th century became the 20th, financiers (mistakenly) thought rapid transit would be a great investment, typically as part of an arrangement we now commonly refer to as public-private partnerships that required transit companies to keep fares low, usually at five cents.

Then it all slowly fell apart. Inflation jacked up costs, but transit companies were legally obligated to keep fares the same per their agreements with cities. The Great Depression hit. Real estate speculators sold off all their land and no longer cared about the transit connections. The public utility companies were forced to sell off their streetcar stakes by Congress under an antitrust provision. Long-term maintenance and upkeep rendered short-term profits illusory. Although most commuters still used transit through the 1940s, people tended to use private automobiles for recreational trips. Bills for decades of deferred maintenance came due. Streetcars went bankrupt. Local governments picked up the slack, and as part of the transition, closed the electric streetcars and converted those routes to buses. By the 1960s, most every transit system had either closed down or was under the auspices of some level of local government.

“And then that subsidy became an explicit job of the local government to subsidize and take over management,” Davis said. Private subsidies were replaced by public ones, just at the time when government was deeply, fundamentally uninterested in public transit. Because in the mid-20th century, cars were the future.

The Road to More Roads

From 1950 to 2017, the U.S. constructed 871,496 miles of roads, enough to go to the Moon, come back, return to the Moon again, and then get two-thirds of the way back to Earth. The pace has slowed in the last few decades, but barely. Thirty-seven percent of those miles have been built since 1985.

As traffic increased, it was accepted policy to widen a lot of roads under the mistaken belief this would reduce traffic. The Federal Highway Administration only started tracking lane-miles built in 1980, but in the 37 years between then and 2017 we added 881,918 lane-miles to our some four million lane-miles of road, an 11 percent increase. Urban areas in particular added 30,511 new lane-miles to freeways since 1993, an increase of 42 percent, according to the non-profit Transportation for America, which went on to call this program of building more lanes in a misguided attempt to reduce traffic a “congestion con.”

In the meantime, the U.S. barely built any new rail. The Bureau of Transportation Statistics only started tracking rail miles in 1985, but from that year through 2017 the U.S. constructed 6,247 miles of commuter rail, heavy rail, and light rail combined. That’s only 195 miles a year on average, compared to 10,017 miles of roads per year during that same time. In fact, the pace of building new transit has been so languid, America’s 20 largest metro areas have the same or even fewer miles of transit service (including bus routes) per capita than they did in 2003.

“It’s all about priorities,” said Jeff Brown, an urban planning professor at Florida State University. “What are the spending priorities that we’ve established?”

Source: Bureau of Transportation Statistics and Transportation For America. Chart by Cathryn Virginia

Of course, the short term cost of building a mile of road is lower than building a mile of transit, but that can be deceptive. According to Transportation for America, it costs $24,000 per lane-mile per year to maintain a road in good repair, and much more for those in disrepair, as many of America’s roads are. And that’s even before accounting for the strain on public services by encouraging and supporting sprawl where every mile of sewer, water, and power line serves fewer taxpayers.

Nevertheless, we’ve also spent much less money overall on transit compared to roads. These funding mechanisms are extremely confusing and have changed over time, but what has not changed is that roads always get a lot more.

Congress gives states roughly $40 billion a year for roads, according to Transportation For America, which can be spent either on new roads or maintenance at the states' discretion. Meanwhile, public transit agencies have to compete for only $2.3 billion in annual transit funding for big projects such as extending rail lines or building new ones, some $37.7 billion less than what states get for roads (the feds dole out an additional $7.5 billion a year for maintenance and buying new subway cars and buses).

That $40 billion a year in road money is given out to states based on a formula. It’s automatic, and states can spend that money however they wish. Not so with transit money. Transit agencies have to apply for funding for individual projects.

And should the transit agency’s project be deemed worthy of federal funding, the federal government will subsidize a much smaller percentage of the project costs than it will for roads. Transit agencies can get a maximum of 50 percent of the project cost covered by the feds, whereas roads can get up to 80 percent (down from 90 percent during the highway spending spree of the 20th Century).

And this is just at the federal level. The discrepancy between road and transit funding is even wider at the state level, Freemark says, where legislatures are typically dominated by rural interests.

Brown, the Florida State professor, said the numbers don’t lie. “It’s not a sufficient amount of money to support grand project ideas.”

Of course, many people believe it is not the federal government’s role to be paying for mass transportation because it’s a local issue (rarely is a similar argument made about roads). This was very much up for debate when the Urban Mass Transportation Administration (now a part of the Federal Transit Administration) was created in 1964. The upshot was that there’s no clear reason why the federal government should be subsidizing road construction, home mortgages, auto fuel, and any number of other things but not mass transportation. Plus, in light of the local and state government failures to pay for transit, if not the federal government, then who? Tellingly, the UMTA was founded under the Welfare Clause of the Constitution, not the Commerce Clause that authorized highway construction, because it is good for cities to have good transportation.

From nearly any vantage point, this road-heavy, transit-lite approach has been a disaster for American cities. We’ve spent hundreds of billions of dollars constructing and maintaining an unsustainable roadway network, and traffic has only gotten worse to boot. In 2015, California’s Department of Transportation, which supervised some of the most fervent highway construction in the nation during the 20th century, came right out and admitted this didn’t work. More roads means more traffic. So, the state is no longer going to keep widening roads to relieve congestion.

Not only is there not enough money to go around, but it has to be shared by all the states. Federal rules require that no single project gets too big a slice.

“You can’t ask for so much money in a single year as to crowd out everyone else,” explained Davis. For example, he said, the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) under the Obama administration told Los Angeles that it wouldn’t get all the money it wanted for the Westside Purple Line as one big extension through Beverly Hills and into Westwood. So, LA broke it up into three segments, with construction on Phase I beginning in 2014. Each got its own cost-benefit analysis, planning, and studies, and waited a few years between applications, which drives up costs. In February, LA received its grant for the third and final segment, a $1.3 billion payout that will cover just 36 percent of the cost. It is expected to be completed in 2027, meaning it will take 13 years to build a nine mile extension.

“Usually congressional and even executive branch political realities mean they spread the peanut butter around,” said Sarah Jo Peterson, author of Planning the Home Front, “and, when there isn't much peanut butter, they spread it thinly.”

The Costs Are Too Damn High

Not only does the money get spread too thinly, but once cities do get their money, they waste a lot of it.

“In the cities where rail transit works best,” Davis observed, “costs have just gotten out of control.” This is especially true for megaprojects, huge public works that cost billions of dollars.

I could spend an entire article on this subject alone and not even scratch the surface of just how profoundly screwed American megaproject costs are. Indeed, many writers and researchers have done exactly that, and one researcher in particular, Alon Levy, has more or less made a name for themselves on this subject.

New York City is responsible for the most expensive mile of subway track on Earth, at $3.5 billion per mile, the first segment of the Second Avenue Subway. The second phase is projected to crush that record. The Metropolitan Transportation Authority, which runs the subway and commuter rail system, is also some two decades late and $8 billion over budget on the $11 billion East Side Access project, which will bring Long Island Railroad trains into Grand Central, a 15 minute walk from Penn Station where Long Island Railroad trains currently go.

What is undoubtedly clear is every transit project is first and foremost a political project, and political projects are about consensus-building. This gets us not the projects we need but the projects we deserve.

The problem is hardly limited to New York. California’s high speed rail project has given new definition to the term “boondoggle.” And, as Levy has documented, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Seattle, Boston, and D.C., among others, all build subways and light rail lines at much higher costs than European cities.

“Nearly all American urban rail projects cost much more than their European counterparts do,” Levy wrote in Citylab. “The cheaper ones cost twice as much, and the more expensive ones about seven times as much.” This includes both heavy rail (subways) and light rail. “Only a handful of American [light rail] lines come in cheaper than $100 million per mile, the upper limit for French light rail.”

There are a lot of reasons for this, including:

Over-engineered stations

Arcane labor rules that inhibit productivity such as requiring more employees to work at a machine than is necessary

A lack of cooperation between agencies

But cost overruns are not a new problem for American transit.

“Cost escalation has been going on for some time,” Davis of Eno Center said. The D.C. Metro was initially slated to cost $2.5 billion but ended up with a $10 billion bill. Dating back to the Ford administration, the federal government started changing grant rules so the feds wouldn’t be on the hook for the inevitable cost overruns, leaving any eventualities to the transit agency building it and the local government overseeing it.

Do you work for a public transit agency or a contractor and have any experience with how projects end up costing so much? We'd love to hear from you. Using a non-work phone or computer, you can contact Aaron Gordon at [email protected] or [email protected].

Some cost overruns are attributable to unforeseen circumstances, but across the board, we are very bad at estimating how much these projects will cost to begin with. Sometimes, agencies give low estimates in order to make projects more politically palatable, knowing a realistic assessment will get shot down. D.C.’s initial estimate of $2.5 billion, according to George Mason University historian and author of The Great Society Subway: A history of the Washington Metro Zachary Schrag, was “never terribly realistic.”

Depressingly, it seems we gave up on ever building necessary infrastructure for the same price as other countries decades ago. Schrag also quoted Jim Caywood, head of the engineering firm that helped design Metro, as saying “there’s no way in this world that you can build a mammoth public works project such as Metro within a reasonable budget with all the outside influences. They won’t let you do it.”

The Biggest Outside Influence of All

What are those “outside influences” Caywood referenced? The big one is politics.

“Transportation planning is not just a matter of letting the engineers find the best solution to a technical problem,” Schrag wrote, “but a political process in which competing priorities must be resolved by negotiation among interest groups.”

If there’s one point on which all the experts I spoke to agree the most, it is that transportation is politics. A 1988 deep dive into the construction of the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) system by Portland State University professor Sy Adler found any vague proposal for a transit project, whether it be highway or rail, produces competing coalitions with their own self-interests. Maybe they want to spur development in their own downtown area or make it easy for commuters to live in their suburb. These factions then weaponize the options on the table for their preferred ends. The protracted debates result in entire regions losing focus over why they wanted to build a new transit system in the first place. Over time, it becomes a battle not of which option solves a given problem, but re-defining what the problem is.

Meanwhile, another cohort of interest groups form to stop projects they don’t want. Typically, these are neighborhood associations that don’t want a transit line coming through their block, either out of fear of construction impacts or racist concerns that it’ll disrupt the segregation of their urban area. Sometimes, they are not just neighborhood groups but entire regions.

In the 1970s, in what was later called “referendums on race,” Atlanta’s suburban and overwhelmingly white Cobb, Clayton, and Gwinnett counties voted out of the region’s MARTA system before it was even built. In 1988, five years after voting in favor of a 200-mile light rail system with local financing, Dallas voters refused to approve bonds to pay for construction, growing skittish on the whole prospect due to the oil crisis which hurt the local economy, according to Indiana University professor George Smerk’s history of the government’s mass transportation policy. Seattle, Detroit, and scores of other cities either voted against major transportation projects or approved watered down versions of original plans thanks to local opposition.

What is undoubtedly clear is every transit project is first and foremost a political project, and political projects are about consensus-building. This gets us not the projects we need but the projects we deserve.

To take just one of scores of possible examples because it affected me personally: back in the 1970s the University of Maryland rejected plans to have the D.C. Metro’s Green Line stop on campus, again for predominantly racist reasons. This forced “a complicated redesign” that “later caused commotion in College Park,” Schrag wrote. Today, anyone looking to take public transportation to the university, with 41,000 students and 14,000 faculty and staff, must either take a shuttle bus from campus or walk at least 20 minutes each way. Repeat these fights dozens of times per project and it’s no longer so difficult to envision how they end up getting relegated to land the public already owns regardless of how useful it is like freeway medians or don’t get built at all.

Meanwhile, a great political shift occurred in the United States that made transit’s prospects even worse. First was the Reagan-era movement away from services provided by the government and towards private enterprise.

Transit was not spared. When Miami’s Metrorail opened, Reagan derided the “$1 billion federal subsidy” that “serves less than 10,000 daily riders” as a prime example of government waste. Better for the government to have bought everyone a limousine, Reagan quipped.

Nevermind that all of those numbers were incorrect and deeply misleading because the project hadn’t even been completed yet, according to the Sun-Sentinel. But factual errors aside, there was a larger ideological one. “Even if Metrorail doesn't turn a profit,” the paper said, “it will be performing a valuable service. Without it, thousands of new commuters would be forced back into their cars, making the roads even more overcrowded.”

Ironically, some of the blame for the wastefulness of federal transit money belongs to Reagan himself. He spent considerable effort trying to kill the main transit grant program, according to Davis, but Congress wouldn’t let him because these projects were often popular.

In order to keep the funding going, Congress had to resort to doling out the money through annual appropriations—in other words, the 435 members of the House of Representatives, with all its byzantine committees and rules, deciding for itself which projects to fund rather than career experts in the Federal Transit Administration—through a process called earmarking. In this way, transit projects became just another horse to trade.

“The nature of earmarking is that since there are 435 House districts and 50 states, and only so much money to go around, things get split more widely than they would if the Administration just got to pick a few.” Davis continued: “Ted Stevens [longtime Alaska Senator and chair of the Senate Appropriations Committee from 1997 to 2005] used to put a million dollar grants to little towns all over Alaska. I don't know what the hell they were for.”

Not only did it become fashionable to slash funds for big transit projects, but so too was it the sign of the times to slash agency budgets as well. Expertise then migrated to the private sector, in many cases to the very consultants and engineering firms hired to execute the few projects that got done. As a result, agencies were—and remain—ill-equipped to make big decisions on big projects, who hire those aforementioned consultants, who in turn charge a pretty penny for their services.

Do you work for a local transit agency and struggle with a lack of resources or funding? We'd love to hear from you. Using a non-work phone or computer, you can contact Aaron Gordon at [email protected] or [email protected].

“We often don't have really expert public staff making decisions, making some key decisions at least,” said Eric Eidlin, a former FTA planner. “We've given over that responsibility to consultants that have a profit motive. I don't mean to say that the consultants have this desire to subvert the public interest or anything, it's just not their job, right?”

Karen Trapenberg Frick, an urban planner at UC Berkeley who used to work for the Bay Area’s planning commission, echoed Eidlin’s point and said it had a real impact on what agencies were able to do, only further undermining the public’s willingness to give them money for big projects.

“There are certain cities where when I was a planner a long time ago and now, it's the same complaint: we give the city money but they can't move the project through because they don't have the staff to do it,” she explained. “And we don't have the staff to do it because there's been this whole neoliberal mind shift that the public sector can't do a good job.”

There’s a very sad irony here. The Reagan era cuts were ostensibly designed to make the public sector more efficient by harnessing the power of the market, but instead it made public agencies reliant on for-profit contractors that jack up costs, only making government less efficient and more wasteful.

“When there's no in-house public sector expertise, the ability to deliver projects quickly or efficiently is compromised,” Eidlin said. “And time is money, too.”

Who Decides?

So far, I’ve focused on the federal side of things because it has a lot of money and power. But what level of government is the right one to make decisions about massive transportation projects? Although there is no obvious right answer, it feels like the U.S. has discovered an awful lot of wrong ones.

As a nation, local authority is our founding principle. We fought a revolution to achieve it, wrote a (bad) set of rules to maintain it, scrapped those, then wrote a new set of rules we have been arguing about ever since. Most of those arguments have been about whether the federal or state governments should determine how we live.

But unprecedented depressions and world wars have a funny way of harnessing big government power, and the feds continued to flex those newly-discovered muscles as American cities deteriorated in the years afterward. From New York to Los Angeles and in dozens of cities in between, so-called “urban renewal” programs used federal dollars to quite literally tear down and rebuild massive sections of cities from scratch, sometimes in order to build a highway through the demolished portion. One of the many legacies of this program, which destroyed entire neighborhoods, was a growing distrust in the government to sensitively execute centrally planned projects. The preferred remedy was to have more local control, neighborhood by neighborhood.

This approach has its merits, but for transportation it has serious drawbacks. Whether they be subways, light rail, bus routes, or even the humble bike lane, any transportation worth using is a network that allows people to get from one side of a city to another quickly and efficiently. Giving substantial input or even veto power to individual communities along that network undermines the entire concept.

“Transit is fundamentally regional,” Eidlin said, “And I really feel like our general population and our decision makers don't universally agree with that or even had that epiphany yet.”

Just as too much hyperlocal control can stymie useful transit, putting transit under the auspices of entire states can have downsides, too. Several of the country’s biggest transit systems including New York, Boston, and Washington, D.C. are controlled not by local authorities but state (or in D.C.’s case, quasi-federal) bodies. This means taxpayers who don’t obviously benefit from the system pay into it, a constant source of political tension. And when proposed projects cross state lines, it opens up a prolonged debate about who pays for what share, a fight that often takes years or decades to resolve.

Put the lack of funds for transit together with our country’s general desire to give local control as close to the individual citizen level as possible, and we’re left with a contradictory system where every limb and appendage fights the others. The lack of funds dedicated to transit means higher and higher levels of government—the ones with more and more money—often have control over transit, either by law or by practice. But those same agencies must seek local consensus for what are not local projects, a time-consuming and expensive proposition at best and a poison pill at worst.

This desire for local control yields bizarre outcomes. For example, Eidlin is working on a transportation hub project in San Jose, CA. Four different public agencies are involved, each for a different jurisdiction that will meet at the hub (this is indicative of the Bay Area, which has 27 transit operators and 151—yes, 151—transit agencies). As a result, Eidlin says much of the project’s work at this stage is not on the project itself, but administrative tasks to keep all the agencies up to speed.

“We value local control so much and we fund so many things locally that we never stop and ask,” Eidlin said, “what's the right level of government at which to be addressing a public issue?”

How To Fix This

As dire as the American transit landscape is, there are specs of hope. Federal funds are no longer given out through earmarks; that stopped in 2010. Now, the FTA grades projects based on merit. And some metro areas have big plans. Los Angeles and Seattle voters have opted to raise their sales taxes slightly to fund tens of billions of dollars in transit upgrades that could significantly improve their region.

But we need much bigger solutions, not only to build transit systems faster and more efficiently, but to run them better, too. In the vicious cycle of transit funding, agencies that are perceived as wasteful or bad at providing services have a harder time getting money from politicians, which then makes it harder to run a good transit service. This cycle must be broken.

Public transit…ought to be as natural a government service as trash collection.

More money for transit would obviously help. Bernie Sanders has proposed $300 billion for public transit by 2030 and $607 billion for a high speed rail network (Joe Biden, in an excellent distillation of the failures of American transportation policy to date, does not commit any dollar amounts to these issues in his platform, but does commit $50 billion in his first year to repair roads, highways, and bridges). That would be a lot more money where it’s desperately needed, and polling suggests it’s a popular platform with majority support.

The most noteworthy part of Sanders' platform, however, is not the money. It’s the framework under which it is proposed: the Green New Deal.

This, says Florida State University’s Jeff Brown, fits with the history of how big transit projects are proposed. “Transit, in most places, has very much been an afterthought or a reaction to some other perceived crisis,” he said. Traditionally, that crisis has been traffic. For periods in the 1970s and 1980s, it was the oil crises. Sanders, however, clearly puts better public transportation within the framework of the climate crisis.

But the very concept of tying transit construction to a crisis misses the point. Transit does address those issues, but it is more than that. We will never build good transit until we jettison the century-old misconception that it is a business the government happens to run out of necessity. Rather, public transportation is a public good on its own merits, good times and bad. Allowing people to move about their cities cheaply, efficiently, and quickly makes cities more productive and better places to live and has numerous knock-on public health, environmental, social, and economic effects. Public transit funding ought not to be a response to any crisis. It ought to be as natural a government service as trash collection.

On the other hand, framing transit as a fight against traffic is a losing battle, because it doesn’t take very many cars to create traffic. It is, as transit planner Jarrett Walker argues, a matter of geometry. It will always appear to a certain type of person that money was wasted. But positing that transit is a way for city dwellers to live better, more pleasant lives is a winning platform, as politicians across Europe can attest.

We also have to work out what the right level of government is to make transit decisions. New York, D.C., and San Francisco in particular have complicated and bizarre governance structures for their transit agencies. Most of these structures were created in mid-century when good governance types replicated the corporate boardroom as the ideal of good governance. History has proven this approach hopelessly naive. Transit is politics. It’s time to, as Freemark has argued, put transit squarely within the responsibility of one elected official who is clearly accountable.

None of this solves what may be the biggest impediment to good American public transit: costs. The solutions here are not easy. Hell, as Josh Barro of New York has pointed out, and I've also learned, we don’t even fully understand the problem. At the very least, fixing it requires cultivating long-term expertise on the local level so agencies aren’t reinventing the wheel the rare occasions they’re given enough money to undertake megaprojects. It also might require, as Laura Tolkoff of the San Francisco-based non-profit SPUR suggested, establishing governmental entities with in-house megaproject expertise, weaning the transit world off relying on expensive contractors and consultants and onto agencies looking out for the taxpayers’ interest, not the stock market’s.

These are just a handful of the high-level suggestions I learned while reporting this story. I will keep reporting on this and learning more, and you should contact me if you work in a transit-related industry and know anything I ought to know. But one thing we must always keep in mind is the answers are out there.

“[The U.S.] needs to learn what works in Japan, France, Germany, Switzerland, Sweden, the Netherlands, Denmark, South Korea, Spain, Italy, Singapore, Belgium, Norway, Taiwan, Finland, Austria,” Levy wrote. “It needs to learn how to plan around cooperation between different agencies and operators, how to integrate infrastructure and technology, how to use 21st-century engineering.”

To that end, Levy and fellow researcher Eric Goldwyn just received a two-year grant from the John Arnold Foundation via New York University to study why U.S. construction costs are so high. And they’re looking to hire a research associate, preferably one with language skills other than English. “We are particularly looking to extend our coverage outside countries where information is readily available in English,” their job posting for the project says.

“Imitate,” Levy advises. “Don’t innovate.”

Why the US Sucks at Building Public Transit syndicated from https://triviaqaweb.wordpress.com/feed/

0 notes

Text

LIVING IN A DECENTRALISED WORLD AS NEW PERSPECTIVE FOR THE 21st CENTURY

Picture: Swamps created by imported beavers in Chilean Patagonia

I have just returned from an interesting journey through Chile and Argentina, two developed South-American countries. Except for the capitals Santiago and Buenos Aires, my wife and I also visited Patagonia by boat. We saw beautiful nature, with interesting animals and abundant vegetation and had to discover this on zodiacs, since there are not ports and nobody lives there. But we also were confronted with the errors human beings committed in the past, hundred year ago, that still influence the conditions of nature drastically. Settlers alongside the Strait of Magellan considered the land as prosperous for setting out beavers and to hunt them afterwards for their fur. It would be a lucrative business, with a nice profit and not too much work. They start to set out 1 beaver family, consisting of 3 beavers. Nowadays, hundred years later, the area, abandoned by humans because of its harsh climate, counts 300.000 beavers that deviate rivers and create swamps everywhere. They have no natural enemies that are large enough to keep them in balance. Except for the beavers the alien fauna was also composed of bewildered swine and minks. They cause less damage but influence though the natural growth of berries and flowers.

Although an intelligent creature, the human being is often a threat to its environment, be it other humans, animals, plants or nature in general. The motives that drive human beings are different from the rest of nature, driven by the survival of the fittest, and focus on profit and power. In many circumstances a call for power, selfishness and greed lead to ruthlessness, at a level that is unknown by the rest of the living beings. And is moreover accepted and even applauded by the rest of the human beings.

We started this article with this metaphor because we want to consider and describe a trend that shows up and that pleads for a life and an economy with smaller and more decentralised players. And consequently with states and nations that consider a more decentralised way of decision making as a model for the future.

The symptoms and the diagnosis

In Europe we assist for the moment to a lot of social and political trends that are disruptive and scare off people as well as politicians. We are confronted with the phenomenon of the yellow vests movement. Although they originally opposed an increase in fuel taxes, this civil movement has become a forum for a protest of the lower incomes and the rural population against a world that does not take their concerns into account: finding work in their own environment, not constantly to be threatened with new taxes, and especially: being able to identify with the world around them.

On the other hand, we observe the movement of schoolchildren and students who are called climate truants. For the first time in history, school-age youth is taking the lead in a fight to convince politicians to pay more attention to climate change and to develop a strategy that is compelling for all sections of a country: citizens, businesses, institutions, even if this requires a shift in income distribution. In the U.K. this same movement is driven by intellectuals and called “Extinction Rebellion”. Their actions are more violent blockading the city, engaging in civil disobedience, taking direct action. But their aim is the same: to demand decisive action from governments on the environmental crisis.[1]

We also are confronted with the Brexit, through which the oldest democracy on earth shows that its democratic model has reached its limits and that it is unable to solve the problem it has caused because of its inadequate communication. It is a lengthy process that absorbs so much energy that companies can no longer concentrate on their core business: producing and doing business. It is a seemingly bottomless pit in which citizens see their tax money disappear without producing results for themselves.

Politicians have no direct answer to these movements that have emerged from the bottom up and become nervous. Until now, they were accustomed to impose the marching direction of the voters and their pace of the march. In the last years, the politicians arguments more looked for culprits outside their own decision field: the EU is guilty and must therefore be undermined, foreigners are the reason and must therefore be expelled. After all, the attack is the best defence.

Everyone who criticized the major economic paradigms was ridiculed: the market is always right. Globalisation is good for humanity. When companies leave because they can get more margin elsewhere, we can't help it and we just have to become more creative. Industry is something of the twentieth century and is now being concentrated in China. Of course, traditional industrial plants moved away from the expensive Western-European and North-American salaries. For several decades, sectors like financial services, consulting, the entertainment industry, training and tourism have created far more jobs than the traditional industrial sectors. In 2018, the service sector created six times more jobs in the private sector than the industrial sectors. [2] Yet many countries have understood that countries without a real manufacturing industry do not have sufficient independent economic power to grow and create jobs. Hence, movements to re-industrialize are encouraged by the EU,[3] because “finance, research and employment depend largely on the industry sector, which accounts for 80 per cent of Europe’s exports and private innovations, and provides high-skilled jobs for citizens” [4] And: a country is only successful if it can attract large international companies that create a lot of jobs. As compensation, they will receive a tax exemption.

Europe is going through turbulent times in which many are missing a hold. But Europe is based on common values: civil and political freedom, equality before the law, democracy, human truth and a rational world view. Those values are admired by the rest of the world, not by their leaders but by the population. These values must provide guidance for the next steps to be taken.