#linda dalrymple henderson

Text

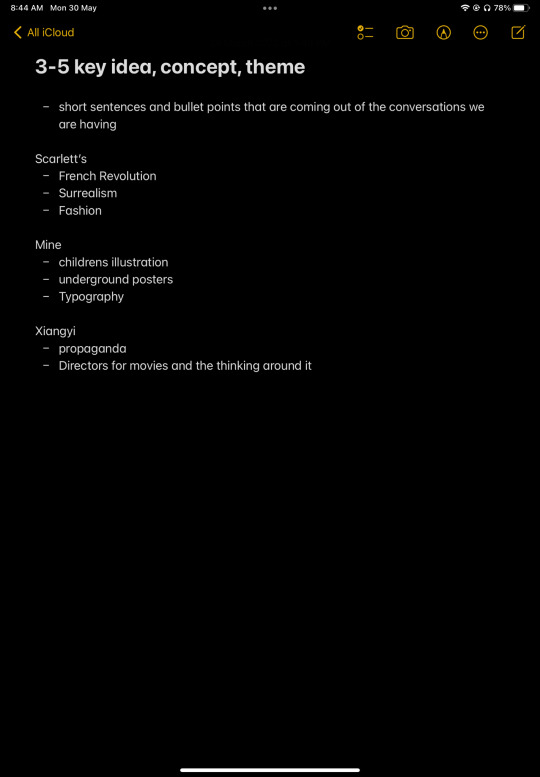

Hilma af Klint. Tidsandans visionär / Visionary, Edited by Kurt Almqvist and Louise Belfrage, Texts by Julia Voss, Tracey Bashkoff, Isaac Lubelsky, Linda Dalrymple Henderson, Marco Pasi, Bokförlaget Stolpe, Stockholm, 2019

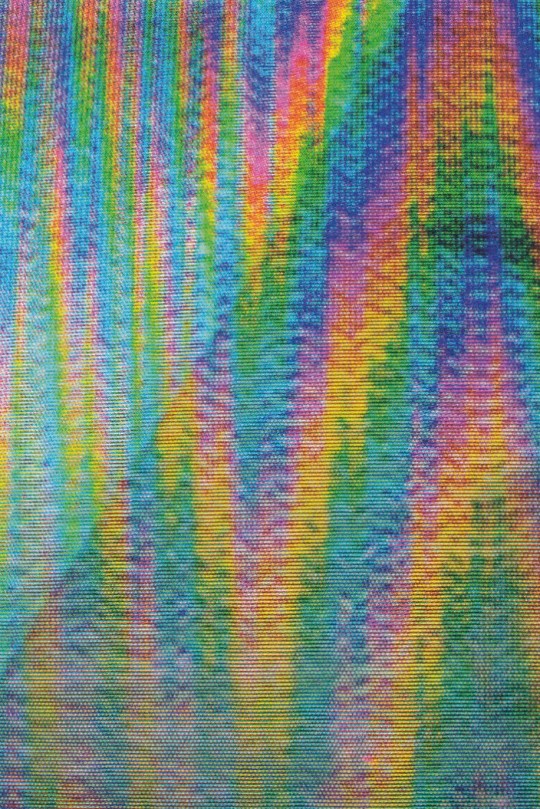

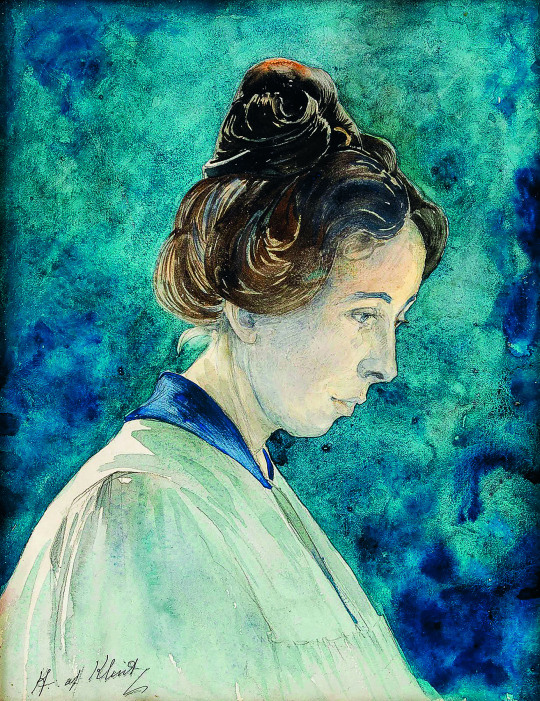

Cover Art: Hilma af Klint, Series VIII. Picture of the Starting Point, 1920 [© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk, Stockholm]

#graphic design#art#drawing#geometry#pattern#catalogue#catalog#cover#hilma af klint#kurt almqvist#louise belfrage#julia voss#tracey bashkoff#isaac lubelsky#linda dalrymple henderson#marco pasi#bokförlaget stolpe#stiftelsen hilma af klints verk#1920s#2010s

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

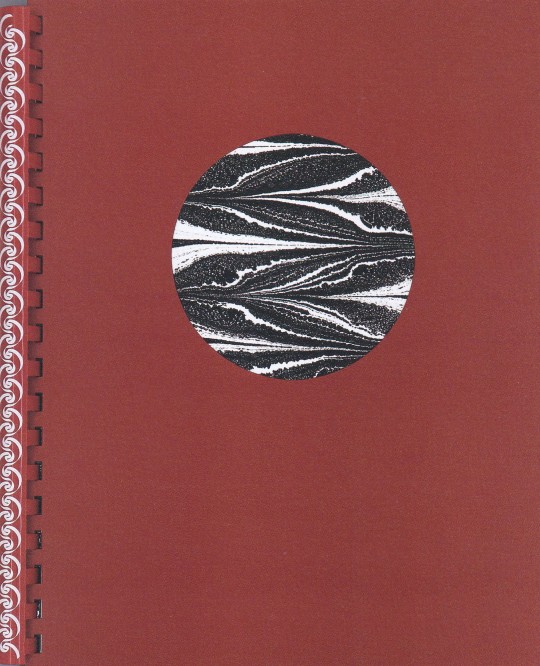

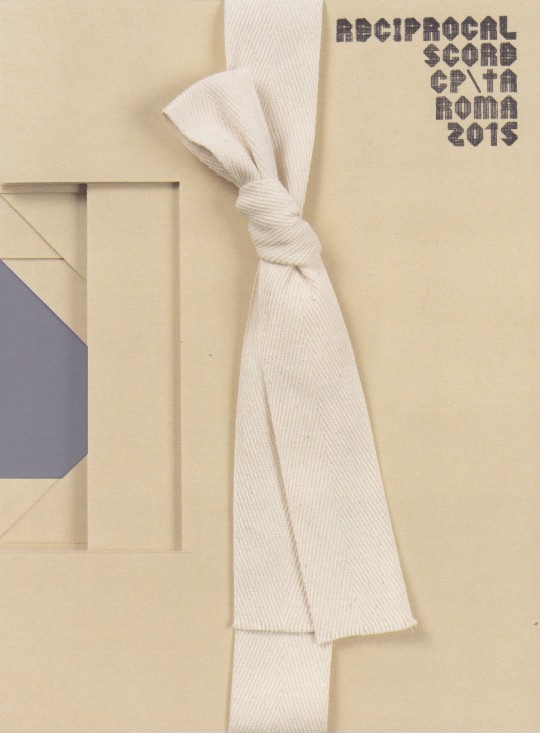

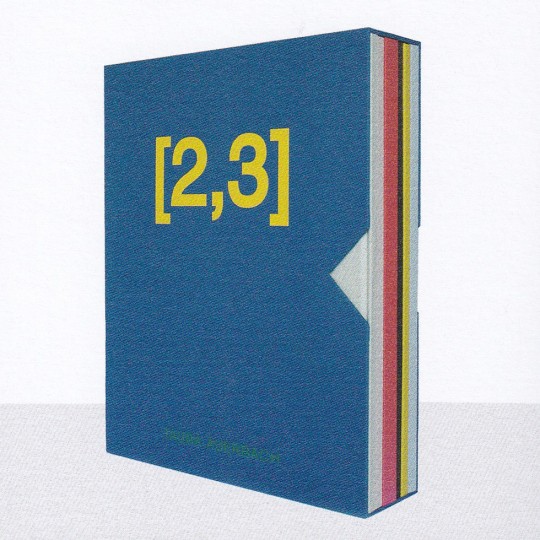

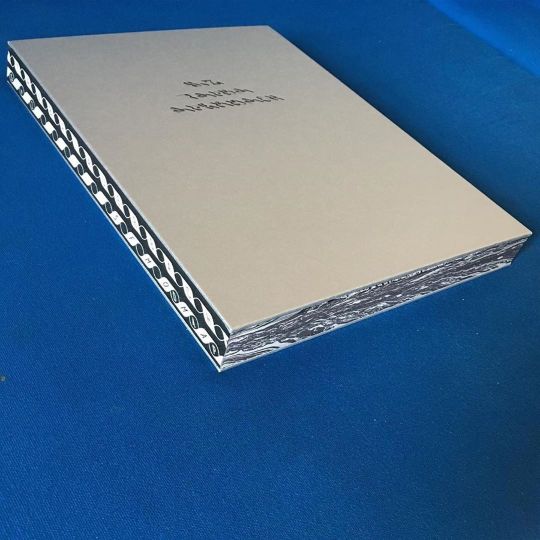

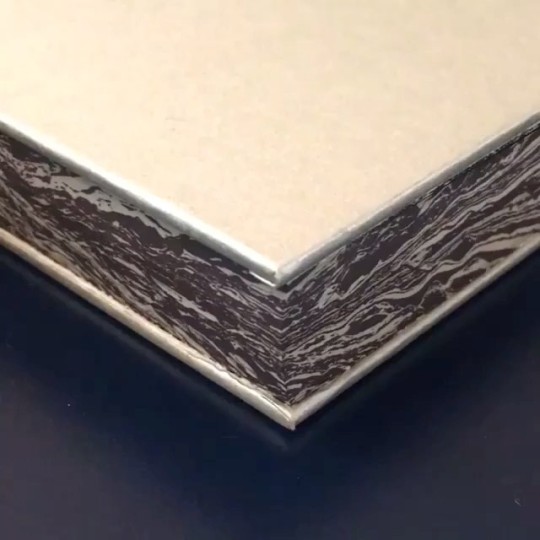

Tauba Auerback - S v Z

Texts by Joseph Becker, Jenny Gheith and Linda Dalrymple Henderson

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco 2020, 256 pages, 485 illustrations, 21x30cm, ISBN 978-1-94288-55-2

euro 49,00

email if you want to buy [email protected]

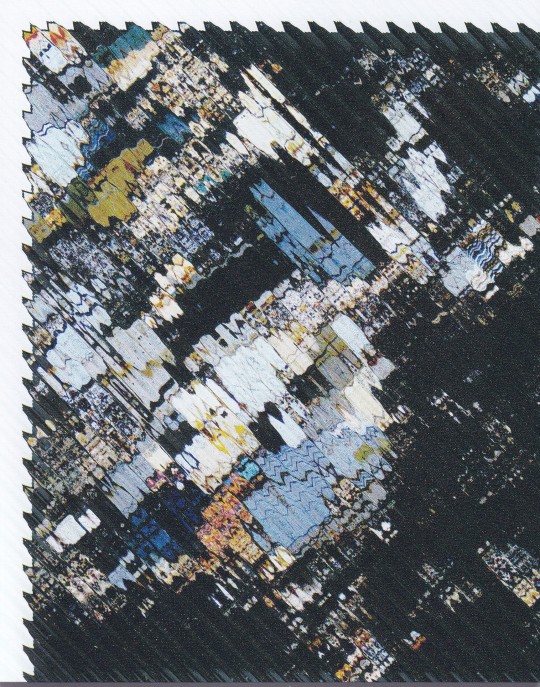

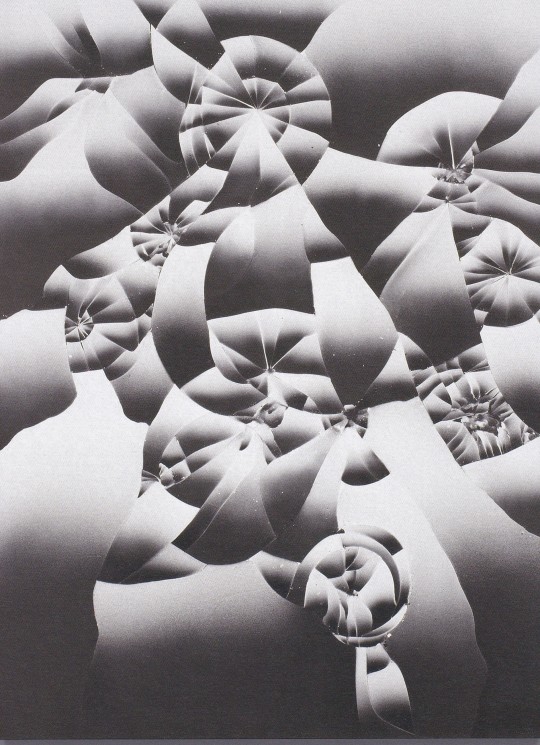

Part artist's book, part exhibition catalog, this book chronicles Tauba Auerbach’s multimedia syntheses of abstraction, science, graphic design and typography

Tauba Auerbach studies the boundaries of perception through an art and design practice grounded in math, science and craft. Published in conjunction with the first major survey of the artist’s work, this volume, designed by Auerbach in collaboration with David Reinfurt, spans 16 years of their career, highlighting their interest in concepts such as duality and its alternatives, interconnectedness, rhythm and four-dimensional geometry.

Encapsulating Auerbach’s longstanding consideration of symmetry, texture and logic, the title S v Z offers a framework for this volume’s typeface, design and structure. Images of more than 130 paintings, drawings, sculptures and artist’s books are mirrored by a comprehensive selection of related reference images, illuminating their multifaceted practice as never before.

The book contains original marble patterns created specially for the book by the artist on both the endpapers and the edges of the book block. The cover is lettered in Auerbach’s calligraphy, applied in black foil on a silver paper. The typeface was designed by David Reinfurt with Auerbach expressly for this publication, and is based on their handwriting.

New York–based artist Tauba Auerbach (born 1981) grew up in San Francisco and graduated from Stanford University in 2003. She apprenticed and worked as a sign painter at New Bohemia Signs in San Francisco. In 2013 she founded Diagonal Press. They are represented by Paula Cooper Gallery, New York, and Standard Oslo.

17/03/24

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#Linda Dalrymple Henderson#book cover#cover design#geometry#Euclidean#non-Euclidean#non-Euclidean geometry#modern art#art#dimensions#fourth dimension#4D

823 notes

·

View notes

Text

Week 5 Lecture notes and SDL

Week 5 lecture notes

The World War I-

20 million deaths and 21 million wounded. Many under 19 years old.

98,950 served in New Zealand units overseas. 80% were volunteers.

Spanish Flu Pandemic

From 1918 through 1920, the Spanish flu killed from 17.4 to 100 million people worldwide. In two months New Zealand lost about half as many people to influenza as it had in the whole of the First World War.

COVID 19

Deaths - 6.07Millions

Science

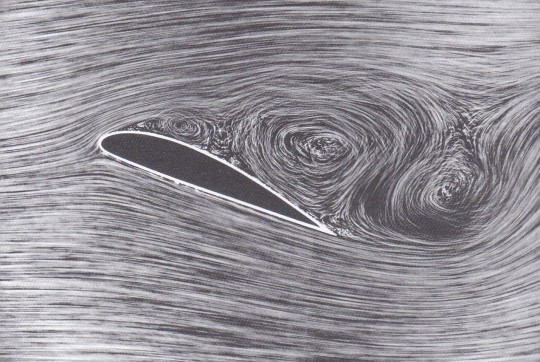

In 1916, Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity. Changed the way we look at the cosmos and how gravity is a bend of space by mass and energy. "The idea of a special fourth dimension is such a liberating one for artists, " says Professor Henderson. "It's not surprising that styles like cubism developed, because all bets were off in terms of space and matter"

- Linda Dalrymple Henderson

The Avant-garde Started in the 19th Century and ended in the 1920s and 1930s. The French term refers to something visionary and ahead of its time. In reference to art, the term means any artist, movement, or artwork that is regarded as innovative and boundaries-pushing, opposed to mainstream cultural values, and with social or political connotations.

Avant-garde designers were young people, on their 20's. They wanted nothing less than to change the world.

Italy had a very large debt, very few natural resources, and almost no transportation or industries. This combined along with a high ratio of poverty, illiteracy, and an uneven tax structure weighed heavily on the Italian people in the country.

Location:

Kingdom of Italy 1909

The futurists

Futurism was an avant-garde movement that embraced innovation, technology, and transportation-all components of the future they saw after WWI. The Futurists' celebration of war as a means to remake Italy and their support of Italy's entrance into World War I.

Innovation

Modernity

Speed

Marinetti, who admired speed, had a car accident outside Milan in 1908 when he veered into a ditch to avoid two cyclists.

Futurist Manifest at Le Figaro

The crash -to him a symbol of how the old ways (bicycles) must give way to the new ones (his car)is what propelled Marinetti to put into writing a theory of progress.

Passionate

Aggressive and

intended to stir

controversy

Manifesto is a written statement where artists often publicly declare their intentions, opinions and visions about the artistic movement.

His masterpiece work, Zang Tumb, Tumb excerpts in journals and an artist's book.

Marinetti used free verse to express the sensations of artillery assaults on Adrianopoli where he spent time as a correspondent in the Balkan War (1912).

He used neither verbs nor adjectives, only nouns scattered about the page, conveying meaning through size, weight and placement - a revolution in style that deconstructed traditional linear writing.

Tavole parolibere

(free-word pictures)

Typography mixed with imagery to create a kind of visual and aural cacophonv. As the woman depicted in silhouette reads a note from "her artilleryman; fragments of words both real and constructed, and distorted in size, shape, and form, thunder above her, reflecting the sounds of the war as well as the Futurists' fight against convention.

In the Evening, lying on her bed, she reread the letter from her Artilleryman at the Front. My revolution is directed against the so called typographical harmony of the page.

Reject the traditional past of book design. Reflection on the book's form stretched to materials. The idolisation of cars and planes suggested that metal was one of the materials most representative of the Futurist mindset.

Tullio d'Albisola (Tullio Spartaco Mazzotti)

Legacy

Use of materials.

Breaking conventions.

Influences on space and typography.

Asymmetry in compositions.

Visual effect of words: Words were

given a visual design; the text was transformed into images and printed in the same way as illustrations.

Focus largely on technology, and industrialism

When Marinetti's political party - a combination of political and futurist views - failed, he tried to promote futurist views in other ways, but it was received in a negative Way.

"The Futurist is dead. What killed it? Dada"

Dadaism

Anti Art movement

Protest against traditional beliefs of a pro-war

society, cultural and political critique.

Satirical, nonsensical, irrational,

anti-bourgeois, Humorous,

Absurd, Spontaneous

Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings - The couple opened the Cabaret Voltaire where Dada was born. There Ball organized and promoted Dada events, including performances often reciting his sound poems.

Karawane

Ball wrote his poem "Karawane"' a poem consisting of nonsensical words. The meaning, however, resides in its meaninglessness, reflecting the chief principle behind Dadaism.

Marcel Duchamp Often include found objects and materials combined through collage and ready-mades. Calling repurposed everyday items "art'. Hannah Höch Höch used her collages to criticize societal institutions, explode gender norms and shows a distinctly queer, feminist perspective. Tension between humanity and mechanization/ machine and rapid industrialization.

Kurt Schwitters

Schwitters published 24 issues the periodical Merz.

"In the war, [...] Everything had broken down and new things had to be made out of the fragments; and this is Merz."

John Heartfield

Anti-Nazi and anti-fascist

photomontages.

240 political art

photomontages.

He was considered the number five on the Gestapo's most-wanted list.

ADOLF, DER UBERMENSCH: Schluckt Gold und redet Blech

Adolf the Superman: Swallows

Gold and Spouts Tin (1932)

A swastika replaces his heart, and his torso is an x-ray revealing gold coins flowing down his throat and collecting in his stomach. John Heartfield Engraving (Rotogravure) Heartfield would sketch out his compositions and then find appropriate photographs. When necessary, he would have new photos made. He would then cut them apart and reassemble them. They would be photographed and a printing plate would be made. From this, massive numbers of prints could be cheaply made and freely distributed.

Dada after the War

Dada was a hugely liberating movement

that inspired other art movements.

After the war ended, it was divided into

two parts.

One with André Breton, a French poet

and writer, which led to Surrealism.

Other, with Kurt Schwitters and John

Heartfield who continue to work on

their designs and photomontages.

Legacy

Duchamp once explained, "the spectator" who "makes the image." Their philosophy is that the idea of an artwork is more important than the work itself, and that art can be made of anything.

Typographic design and the concept of letterforms as concrete visual shapes, not just phonetic symbols.

Photomontage

Photomontage, a technique of manipulation found photographic images to created jarring juxtapositions and chance associations. Photomontage as a social critique.

Present reality in a peculiar, humours, unfamiliar and uncanny way.

Jarring juxtapositions and associations.

In class Text Analysis

Text Analysis for week 5 SDL

ttps://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.aut.ac.nz/public/SS36470_36470_34325420

https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.aut.ac.nz/#/asset/26293887

https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.aut.ac.nz/#/asset/AMCADIG_10310847892

https://wordpress.org/openverse/image/5f683c78-d563-4772-8dba-182dc99a02d1

https://wordpress.org/openverse/image/93772b73-e36d-42f0-bbc0-3a07e831ff55

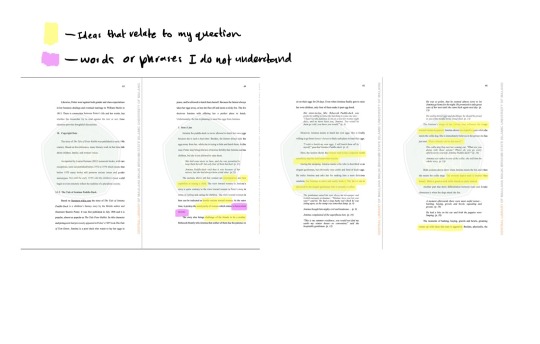

Social class feminism and children literature in the industrial revolution I

Is there still a show of women’s place within the modern renditions of Peter Rabbit and Beatrix Potter children’s literature?

Why was Beatrix Potter anti-feminist?

Was there a show of women’s place within Beatrix Potter’s children literature and is this still evident within the modern renditions of these stories?

How was social class feminism and women’s place in Victorian society displayed within Beatrix Potter’s children literature and is this still evident within the modern renditions of these stories?

https://www.flickr.com/photos/40842447@N08/4520015655

Cole, W. (2021, December 13). What did victorian servants wear? Retrieved April 12, 2022, from https://cubetoronto.com/victoria/what-did-victorian-servants-wear/

https://www.mckendree.edu/academics/scholars/issue18/appell.htm#:~:text=Women%20in%20the%20Victorian%20society,were%20of%20a%20wealthy%20family.

https://open.maricopa.edu/culturepsychology/chapter/stereotypes-and-gender-roles/

https://eige.europa.eu/publications/sexism-at-work-handbook/part-1-understand/what-sexism

https://sites.udel.edu/britlitwiki/social-life-in-victorian-england/

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Beatrix-Potter

https://owlcation.com/social-sciences/What-Does-the-Hands-Behind-the-Back-Pose-Mean#:~:text=It's%20also%20a%20strong%20position,the%20body%20as%20a%20target.

Worthy, L., Lavigne, T., & Romero, F. (2020). Culture and Psychology. Glendale Community College part of Maricopa County Community College District (MCCCD) Maricopa Millions, Phoenix AZ.

Appell, F. (n.d.). Victorian ideals. Retrieved April 14, 2022. https://www.mckendree.edu/academics/scholars/issue18/appell.htm#:~:text=Women%20in%20the%20Victorian%20society,were%20of%20a%20wealthy%20family.

Allen, H. (2018, November 4). What does the hands behind the back pose mean? Owlcation. Retrieved April 14, 2022, from https://owlcation.com/social-sciences/What-Does-the-Hands-Behind-the-Back-Pose-Mean#:~:text=It's%20also%20a%20strong%20position,the%20body%20as%20a%20target.

Fox, C. (2021, July 16). Fox Symbolism: The ultimate guide. All Things Foxes. Retrieved April 14, 2022, from https://allthingsfoxes.com/fox-symbolism/

Potter, B. (n.d.). Illustration of Mrs Tiggly-Winkle from Beatrix Potter . Illustration by Beatrix Potter. Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/40842447@N08/4520015655.

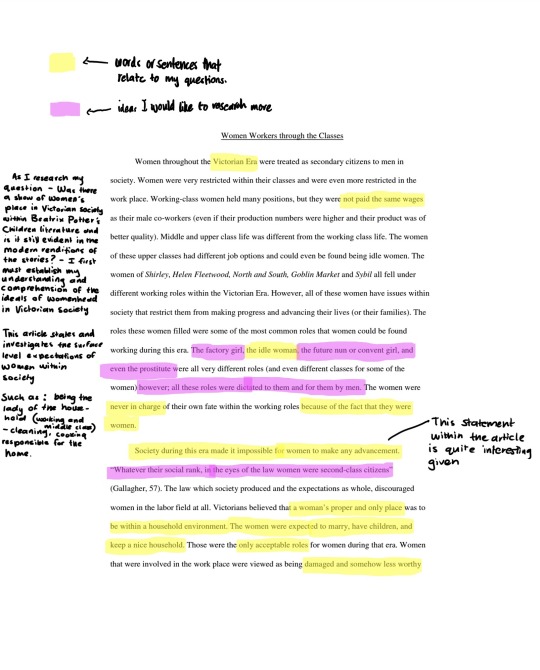

Discussion in breakout room in design research between Scarlett, Xiangyi and I where we summarised the many ideas shown in our moodboards we created.

Mine were

- childrens literature illustration

- underground posters

- Typography

0 notes

Photo

"Method and madness can work in tandem and even be transportive." A deep review of 'Tauba Auerbach — S v Z' — on view @sfmoma — is up now @nytimes We are proud to have published the "remarkable catalog cocreated with the designer David Reinfurt," @tausifnoor writes; "it features essays by the curators and the art historian Linda Dalrymple Henderson — all of it printed in a custom-designed font based on the artist’s own handwriting." We also appreciate this: "Since 2009, Auerbach — whose pronouns are they/them — has sustained a rigorous drive for investigating both scientific and spiritual concepts, drawing equal inspiration from the precision of mathematical proofs, the intuitive features of reiki (a form of energy healing), qi gong (a gentle system of movement) and the inherent entropy of the cosmos. Consequently, Auerbach doesn’t stick to one medium, favoring instead an eclectic mix of painting, photography, design, music, sculpture and typography. Combining the curiosity of a novice with the nimbleness of an expert, Auerbach offers with each project a truly refreshing contribution to contemporary art — namely, the conviction that the world is still full of wonder." Read the full review via linkinbio @tau_au #taubaauerbach #taubaauerbachsvz @david_reinfurt https://www.instagram.com/p/CZSGB3dJyNy/?utm_medium=tumblr

0 notes

Text

The Mechanical Daughter of Rene Descartes: references

1 For the idea of Descartes creating the automaton to deal with the loss of his daughter, see Levitt, Deborah, “Animation and the Medium of Life: Media Ethology, An-ontology, Ethics,” Inflexions, 7 (March 2014), 118–61Google Scholar, at 138; Jess-Cooke, Carolyn, Inroads (Bridgend, 2010), 60 Google Scholar n. 42; Berlinski, David, Infinite Ascent: A Short History of Mathematics (New York, 2005), 40 Google Scholar; Perkowitz, Sidney, Digital People: From Bionic Humans to Androids (Washington, DC, 2004), 56 Google Scholar; Wood, Gaby, Living Dolls: A Magical History of the Quest for Mechanical Life (London, 2002), 4 Google Scholar; and Brodo, Susan, “Introduction,” in Brodo, , ed., Feminist Interpretations of René Descartes (University Park, PA, 1999), 1–29, at 4 Google Scholar.

2 Gaukroger, Stephen, Descartes: An Intellectual Biography (Oxford, 1995), 1–2 Google Scholar.

3 Ibid., 1.

4 Ward, Mark, Virtual Organisms: The Startling World of Artificial Life (New York, 1999), 148 Google Scholar; and Brodo, “Introduction,” 2.

5 Cohen, , How to Love: Wise (and Not-so-Wise) Advice from the Great Philosophers (Lewes, 2014), 24 Google Scholar; Nagasawa, Yujin, The Existence of God: A Philosophical Introduction (London, 2011), 15 Google Scholar; Wallin, Jason, “Constructions of Childhood,” in Frymer, Benjamin, Carlin, Matthew, and Broughton, John, eds., Cultural Studies, Education, and Youth (Lanham, MD, 2011), 165–89Google Scholar, at 172; Reilly, Kara, Automata and the Mimesis on the Stage of Theatre History (Basingstoke, 2011), 68 CrossRef | Google Scholar; Wilson, Eric G., The Melancholy Android: On the Psychology of Sacred Machines (Albany, 2006), 95 Google Scholar; Perkowitz, Digital People, 56; and Wood, Living Dolls, 3.

6 Woesler de Panafieu, Christine, “Automata: A Masculine Utopia,” in Mendelsohn, Everett and Nowotny, Helga, eds., Nineteen Eighty-Four: Science between Utopia and Dystopia (Dordrecht, 1984), 127–45CrossRef | Google Scholar, at 142 n. 10.

7 Sawday, Jonathan, Engines of the Imagination: Renaissance Culture and the Rise of the Machine (Milton Park, 2007), 201 Google Scholar; Gaukroger, Descartes, 1; and Geoff Simons, Is Man a Robot? (Chichester, 1986), 16.

8 Nagasawa, The Existence of God, 15; Reilly, Automata and Mimesis, 68; Wilson, The Melancholy Android, 95; and Crevier, Daniel, AI: The Tumultuous History of the Search for Artificial Intelligence (New York, 1993), 2 Google Scholar.

9 Nagasawa, The Existence of God, 15.

10 Maisano, Scott, “Infinite Gesture: Automata and the Emotions in Descartes and Shakespeare,” in Riskin, Jessica, ed., Genesis Redux: Essays in the History and Philosophy of Artificial Life (Chicago, 2007), 63–84 CrossRef | Google Scholar, at 63; and Strauss, Linda, “Reflections in a Mechanical Mirror: Automata as Doubles and as Tools,” Knowledge and Society, 10 (1996), 179–209 Google Scholar, at 193.

11 Cohen, How to Love, 24; Wallin, “Constructions of Childhood,” 172; Vermeir, Koen, “RoboCop Dissected: Man-Machine and Mind–Body in the Enlightenment,” Technology and Culture, 4 (Oct. 2008), 1036–44CrossRef | Google Scholar, at 1036; Wilson, The Melancholy Android, 95; and Wood, Living Dolls, 3.

12 Wallin, “Constructions of Childhood,” 172; and Robinson, Dave and Garratt, Chris, Introducing Descartes (Cambridge, 1998), 102 Google Scholar.

13 Heudin, Jean-Claude, Les créatures artificielles: Des automates aux mondes virtuel (Paris, 2008), 51 Google Scholar; Brodo, “Introduction,” 2; and Gaukroger, Descartes, 1.

14 Cohen, How to Love, 24; Wallin, “Constructions of Childhood,” 172; Vermeir, “RoboCop Dissected,” 1039; Maisano, “Infinite Gesture,” 63; Sterne, Jonathan, The Audible Past: Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction (Durham, 2003), 73 CrossRef | Google Scholar; Wood, Living Dolls, 3–4; Kurzweil, Raymond, The Age of Intelligent Machines (Cambridge, 1999), 29 Google Scholar; Robinson and Garratt, Introducing Descartes, 102; and Flynn, Tom, The Body in Three Dimension (New York, 1998), 10 Google Scholar.

15 Panafieu, “Automata,” 142, n. 10.

16 Cohen, How to Love, 24; Reilly, Automata and Mimesis, 68; Vermeir, “RoboCop Dissected,” 1039; Wilson, The Melancholy Android, 95; and Wood, Living Dolls, 3–4.

17 Money, Nicholas P., The Amoeba in the Room (Oxford, 2014), 46 Google Scholar.

18 Gaukroger, Descartes, 1–2.

19 Brodo, “Introduction,” 1–4.

20 Ibid., 4–5.

21 Wallin, “Constructions of Childhood,” 173.

22 Bloom, Paul, Descartes’ Baby: How the Science of Child Development Explains What Makes Us Human (New York, 2004)Google Scholar, xii.

23 Ibid., xii–xiii.

24 One major category of sources that I chose not deal with, though it provides further proof of the story's popularity in recent decades, is those on the Internet. A quick search will reveal countless websites that mention the narrative. Other references to the story in English and French works published since the 1990s that I have not yet referred to in the notes above are Panagia, Davide, “Why Film Matters to Political Theory,” Contemporary Political Theory, 12(2013), 2–25 CrossRef | Google Scholar, at 15; Humphrey, Nicholas, “Introduction,” in Descartes, René, Meditations & Other Writings (London, 2011)Google Scholar, xiii; Schleifer, Ronald, Intangible Materialism: The Body, Scientific Knowledge, and the Power of Language (Minneapolis, 2009), 35–6Google Scholar; Guido, Laurent, “Modèles et images de la danse(use) mécanique des automates à l’électro-humain,” in Schifano, Laurence, ed., La vie filmique des marionettes (Paris, 2008), 107–25CrossRef | Google Scholar, at 108 n. 3; Muri, Alison, The Enlightenment Cyborg: A History of Communications and Control in the Human Machine, 1660–1830 (Toronto, 2007), 28 CrossRef | Google Scholar; Boden, Margaret A., Mind as Machine: A History of Cognitive Science, vol. 1 (Oxford, 2006), 74 Google Scholar; Godier, Rose-Marie, L'automate et le cinéma (Paris, 2005), 11 Google Scholar; Burnett, Graham, Descartes and the Hyperbolic Quest: Lens Making Machines and Their Significance in the Seventeenth Century (Philadelphia, 2005), 39 Google Scholar; Benesch, Klaus, Romantic Cyborgs: Authorship and Technology in the American Renaissance (Amherst, 2002), 203 Google Scholar; Cavallaro, Daniel, Critical and Cultural Theory: Thematic Variations (London, 2001), 194 Google Scholar; Colburn, Timothy, Philosophy and Computer Science (Abingdon, 1999), 42 Google Scholar; Higley, Sarah L., “The Legend of the Learned Man's Android,” in Hahn, Thomas and Lupack, Alan, eds., Telling Tales: Essays in Honor of Russell Peck (Rochester, 1997), 127–60Google Scholar, at 146–7; and Breton, Philippe, A l'image de l'homme: Du golem aux créatures virtuelles (Paris, 1995), 35 Google Scholar.

25 Kurzweil, The Age of Intelligence Machines, 29; Cavallaro, Critical and Cultural Theory, 194; Ward, Virtual Organisms, 147–8; and Crevier, AI, 2.

26 Gaby Wood, Living Dolls, 4, writes, “It is hard to know if this story is true.” See also Wilson, The Melancholy Android, 95.

27 On twentieth-century critiques of Descartes and his reputation see Sorell, Tom, “Excusable Caricature and Philosophical Relevance: The Case of Descartes,” in Rogers, G. A. J., Sorell, Tom, and Kraye, Jill, eds., Insiders and Outsiders in Seventeenth-Century Philosophy (New York, 2010), 153–63Google Scholar; and John Cottingham, “Descartes’ Reputation,” in ibid., 164–76.

28 For instances of such negative views of Cartesian ideas see Watson, Richard, Cogito, Ergo Sum: The Life of René Descartes (Boston, 2002), 18–21 Google Scholar.

29 See Cottingham, “Descartes’ Reputation.”

30 Gaukroger, Descartes; Rodis-Lewis, Geneviève, Descartes: Biographie (Paris, 1995)Google Scholar, translated into English as Descartes: His Life and Thought, trans. Jane Marie Todd (Ithaca, 1998); Watson, Cogito, Ergo Sum; Clarke, Desmond M., Descartes: A Biography (Cambridge, 2006)CrossRef | Google Scholar; and Grayling, A. C., The Life and Times of Genius (New York, 2005)Google Scholar. A number of other works on more specific aspect of Descartes's life have appeared, including the fate of his remains, the famous painting of him, and his interest in occult philosophy. See Aczel, Amir D., Descartes's Secret Notebook: A True Tale of Mathematics, Mysticism, and the Quest to Understand the Universe (New York, 2005)Google Scholar; Shorto, Russell, Descartes’ Bones: A Skeletal History of the Conflict between Faith and Reason (New York, 2008)Google Scholar; and Nadler, Steven, The Philosopher, the Priest, and the Painter: A Portrait of Descartes (Princeton, 2013)CrossRef | Google Scholar.

31 Watson, Cogito, Ergo Sum, 3.

32 Clarke, Descartes, 2.

33 Kimball, Roger, “What's Left of Descartes?”, New Criterion, 13/10 (1995), 8–14 Google Scholar, at 14.

34 Kimball, “What's Left of Descartes?”, 8–9.

35 Shorto, Descartes’ Bones, 29.

36 For the context of revived cybernetic discourse see Hayles, N. Katherine, How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics (Chicago, 1999)CrossRef | Google Scholar. Hayles characterizes the current cybernetic discourse as “the third wave”: see 11–12 and 222–46. For a more concise overview of the history of cybernetic discourse see Clarke, Bruce, “From Thermodynamics to Virtuality,” in Clarke, Bruce and Henderson, Linda Dalrymple, eds., From Energy to Information: Representation in Science and Technology, Art, and Literature (Stanford, 2002), 17–33 Google Scholar.

37 A good example of this is the neurologist Antonio R. Damasio's book on the embodiment theory of consciousness that was originally published in 1994. Damasio, Antonio R., Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain(New York, 2000)Google Scholar.

38 For example, see Muri, The Enlightenment Cyborg, 13–17.

39 Grafton, Anthony, “Descartes the Dreamer” in Grafton, , Bring Out Your Dead: The Past as Revelation (Cambridge, 2001), 244–58, at 246–7Google Scholar.

40 See, for instance, Perkowitz, Digital People, 55–6; Ward, Virtual Organisms, 147–8; Kurzweil, The Age of Intelligent Machines, 29; Colburn, Philosophy and Computer Science, 42; Crevier, AI, 2; and Simons, Is Man a Robot?, 16.

41 See, for instance, Levitt, “Animation and the Medium of Life”; Muri, The Enlightenment Cyborg; and Hayles, How We Became Posthuman.

42 Works that directly cite Gaukroger are Vermeir, “RoboCop Dissected,” 1036 n. 1; Sawday, Engines of the Imagination, 201, 362 n. 142; Maisano, “Infinite Gesture,” 63, 80 n. 1; Burnett, Descartes and the Hyperbolic Quest, 39 n. 96; Bloom, Descartes’ Baby, x, xii; Reilly, Automata and Mimesis, 68, and 190–91 n. 47; and Brodo, “Introduction,” 2, 25 n. 1. Ones that cite Wood are Panagia, “Why Film Matters to Political Theory,” 15, 23 n. 23; Nagasawa, Existence of God, 162 n. 23; Wallin, “Constructions of Childhood,” 172; Wilson, The Melancholy Android, 152 n. 1; and Maisano, “Infinite Gesture,” 80 n. 1. Some works provide no reference but they are clearly informed by Wood as they feature specific themes like Descartes's travel to Sweden. See Cohen, How to Love, 24; Perkowitz, Digital People, 56; and Jess-Cooke, Inroads, 60 n. 42.

43 For the history and the controversy over Baillet's biography see Sebba, Gregor, “Adrien Baillet and the Genesis of His Vie de M. Des-Cartes ,” in Lennon, Thomas M., Nicholas, John M., and Davis, John W., eds., Problems of Cartesianism(Kingston and Montreal, 1982), 9–60 Google Scholar. Sebba argues (at 41) against the notion that Baillet set out to write a kind of hagiography of Descartes. See also Wang, Leonard J., “A Controversial Biography: Baillet's La Vie de Monsieur Des-Cartes ,” Romanische Forschungen, 75/3–4 (1963), 316–31Google Scholar.

44 Baillet, Adrien, La Vie de Monsieur Des-Cartes (Paris, 1691), 89–90 Google Scholar.

45 For details on this liaison see Clarke, Descartes, 131–6; and Gaukroger, Descartes, 294–5.

46 Gaukgroger, Descartes, 194. Gaukroger quotes an earlier biography by Jack Vrooman. See Vrooman, Jack R., René Descartes: A Biography (New York, 1970), 137 Google Scholar.

47 Clarke, Descartes, 133.

48 Baillet, La Vie de Monsieur Des-Cartes, 90. Gaukroger has suggested that this reaction on the part of Descartes may have been exaggerated by Baillet. See Gaukroger, Descartes, 462 n. 202.

49 Clarke, Descartes, 133–4; and Gaukroger, Descartes, 294.

50 See Rountree, Richard, Bonaventure d'Argonne: The Seventeenth Century's Enigmatic Carthusian (Geneva, 1980)Google Scholar.

51 Ibid., 151–2.

52 Ibid., 157–67.

53 Vigneul-Marville, , Mélanges d'histoire et de littérature, vol. 2 (Paris, 1725), 134 Google Scholar. Thanks to Tili Boon Cuillé for her help with this passage.

54 Descartes, René, The Philosophical Writings of Descartes, vol. 1, trans. John Cottingham, Robert Stoothhoff, and Dugald Murdoch (Cambridge, 1985), 139 Google Scholar (on his notion of animals as soulless machines see 139–41). For details on Cartesian physiology see Chene, Dennis Des Spirits and Clocks: Machine and Organism in Descartes(Ithaca, 2001)Google Scholar; Barker, Gordon and Morris, Katherine J., Descartes’ Dualism (London, 1996)Google Scholar; and Gaukroger, Descartes, 269–99. For older works see Carter, Richard B., Descartes’ Medical Philosophy: The Organic Solution to the Mind–Body Problem (Baltimore, 1983), esp. 175–9Google Scholar; Moravia, Sergio, “From Homme Machine to Homme Sensible: Changing Eighteenth-Century Models of Man's Image,” Journal of the History of Ideas, 39 (1978), 49–60 CrossRef | Google Scholar | PubMed; Rosenfield, Leonora Cohen, From Beast-Machine to Man-Machine (New York, 1940)Google Scholar; Jaynes, Julian, “The Problem of Animate Motion in the Seventeenth Century,” Journal of the History of Ideas, 31 (1970), 119–234 CrossRef | Google Scholar | PubMed; Hall, Thomas S., “Descartes’ Physiological Method: Position, Principles, Examples,” Journal of the History of Biology, 3(1970), 53–81 CrossRef | Google Scholar | PubMed; and Hall, Ideas of Life and Matter, vol. 1 (Chicago, 1969), 250–63.

55 On Descartes's use of the automaton idea see Kang, Minsoo, Sublime Dreams of Living Machines: The Automaton in the European Imagination (Cambridge, 2011), 116–24Google Scholar.

56 Nicolas-Joseph Poisson, Commentaire ou remarques sur la méthode de René Descartes (Vendôme, 1670), 156.

57 Des Chene, Spirits and Clocks, 65–6. For Descartes's description of the magnet-operated figure see Descartes, René, Oeuvres inédites de Descartes, trans. (Latin–French) Foucher de Careil (Paris, 1859), 35–7Google Scholar.

58 Derek J. De Solla Price reported the claim in his 1964 essay on the history of automata, which became the source for other references to Descartes as an automaton maker. De Solla Price, Derek J., “Automata and the Origins of Mechanism and Mechanistic Philosophy,” Technology and Culture, 5/1 (1964), 9–23 CrossRef | Google Scholar, at 23. See also Nagasawa, Existence of God, 15; Boden, Mind and Machine, 74; Perkowitz, Digital People, 55; Sterne, The Audible Past, 72–3; Wood, Living Dolls, 4; and Kurzweil, The Age of Intelligent Machines, 29.

59 This work has a rather complicated publication history. Descartes completed it in the late 1620s but after hearing of the persecution of Galileo, he declined to publish it in his own time as it was full of Copernican ideas. After his death, only the second part of the work on physiology was published in 1662 in a Latin translation, and then in French, under the title of Traité de l'homme, in 1664. The entire work was published as Traité du monde in 1677.

60 Descartes, René, The World and Other Writings, trans. Stephen Gaukroger (Cambridge, 1998), 107 CrossRef | Google Scholar.

61 Jaynes, “The Problem of Animate Motion in the Seventeenth Century,” 224.

62 Battisti, Eugenio, L'Antirinascimento (Milan, 1962), 226 Google Scholar. Thanks to Rebecca Messbarger for translating this passage from Italian.

63 Many modern versions of the Descartes story also mention the Albertus tale. See Sawday, Engines of the Imagination, 193; Berlinski, Infinite Ascent, 40; Heudin, Les créatures artificielle, 66; Gaukroger, Descartes, 418 n. 1; Strauss, “Reflections in a Mechanical Mirror,” 193; Sladek, John, “Roderick, or the Education of a Young Machine” in Sladek, The Complete Roderick (New York, 2004), 1–339, at 327Google Scholar; Price, “Automata and the Origins of Mechanism,” 23; Cohen, Human Robots in Myth and Science, 30; and Louis d'Elmont, “L'homme peut-il frabriquer un homme?” Le petit journal illustré, 19 May 1935, 3.

64 A slightly different translation of this passage, rendered from Italian by Arielle Saiber, has previously been published in Kang, Sublime Dreams of Living Machines, 70–71. For the original text see Corsini, Matteo, Rosaio della vita(Firenze, 1845), 15–16 Google Scholar. The identification of Corsini as the author of the Rosaio was made in the nineteenth century by the Florentine librarian and historian Luigi Passerini, through a comparison of the alleged date of the work's composition to the biographical details of Corsini's life, but his reasoning has not been universally accepted. See Passerini, Luigi, Genealogia e storia della famiglia Corsini (Florence, 1858), 45–8Google Scholar.

65 See de Madrigal, Alonso Fernández, Beati Alphonsi Thostati Episcopi Abulensis super explanatio litteralis amplissima nunc primum edita in apertum (Venice, 1528)Google Scholar, II, 15a. Ben Halliburton identified this text from this reference: Dickson, Arthur, Valentine and Orson: A Study in Late Medieval Romance (New York, 1929), 214 Google Scholarn. 147. For more on the symbolism of moving and speaking statues and artificial heads in the medieval and renaissance contexts see Truitt, E. R., Medieval Robots: Mechanism, Magic, Nature and Art (Philadelphia, 2015), esp. 69–95 CrossRef | Google Scholar; Kang, Sublime Dreams of Living Machines, 68–79; and Dickson, Valentine and Orson 201–16.

66 See Newman, William R., Promethean Ambitions: Alchemy and the Quest to Perfect Nature (Chicago, 2004)CrossRef | Google Scholar; and Eamon, William, Science and the Secrets of Nature: Books of Secrets in Medieval and Early Modern Culture (Princeton, 1994)Google Scholar. For Albertus's interest in alchemy and astrology see Weishipl, James A., ed., Albertus Magnus and the Sciences: Commemorative Essays (Toronto, 1980)Google Scholar; and Lynn Thorndike, A History of Magic and Experimental Science, vol. 2 (New York, 1923), 521–92. Similar stories about the construction of a magical head through the use of natural magic has been told about other celebrated intellectuals of the Middle Ages, including Gerbert (Pope Sylvester II), Roger Bacon, and Robert Grosseteste. See Kang, Sublime Dream of Living Machines, 68–79.

67 Descartes, The Philosophical Writings of Descartes, vol. 1, 115.

68 D'Israeli, Isaac, Curiosities of Literature, vol. 1 (New York, 1971), 441–2Google Scholar. The story, in the same form, was published in 1795 in the Lady's Magazine. See “The Wooden Daughter of Descartes,” Lady's Magazine (Jan. 1795), 7.

69 Some of the modern versions of the story feature the Dutch theme, having Descartes travel to or from Holland on a ship captained by a Dutchman. See Ward, Virtual Organisms, 148; Brodo, “Introduction,” 2; and Gaukroger, Descartes, 1.

70 Emery, Jacques-André, Oeuvres complètes (Paris, 1857), 749 Google Scholar.

71 “A tall tale.” Michaud, Louis-Gabriel, Biographie universelle, ancienne et moderne, vol. 11 (Paris, 1814), 158 Google Scholar.

72 France, Anatole, La rôtisserie de la reine Pédauque (Paris, 1893), 137–8Google Scholar. For an alternate translation see France, Anatole, The Romance of Queen Pédauque (no translator credited) (New York, 1931), 83–4Google Scholar.

73 For instance, Gaukroger, Descartes, 1.

74 As far as I have been able to ascertain, the first twentieth-century scholar to correctly identify the origin of the story was Leonora Cohen Rosenfield in her 1968 book on animal automatism. See Rosenfield, From Beast-Machine to Man-Machine, 203 and, more importantly 236 n. 44. Stephen Gaukroger refers to it as one of his sources but does not discuss the Vigneul-Marville text that is quoted in it. Since then, the original story has been referred to in Reilly, Automata and Mimesis, 190 n. 47; Kang, Sublime Dreams of Living Machines, 123; and Higley, “The Legend of the Learned Man's Android,” 146.

75 Newnes’ Pictorial Knowledge, vol. 6 (London, n.d. but probably 1933–4), 2234. Thanks to Rebecca Hutchins and Barnaby Hutchins for finding and sending me the article and image.

76 Ibid.

77 Leroux, Gaston, “La machine à assassiner,” in Adventures incroyables (Paris, 1992), 485–622 Google Scholar, at 555. For an alternate translation see Leroux, Gaston, The Machine to Kill (no translator credited) (New York, 1935)Google Scholar, 134.

78 Elmont, “L'homme peut-il frabriquer un homme?”, 3.

79 Sladek, “Roderick,” 327.

80 Crevier, AI, 2.

81 Wilson, The Melancholy Android, 95.

82 Heudin, Les créatures artificielle, 51.

83 Cohen, How to Love, 24.

84 This misspelling of “pheasant” (perdrix in the Poisson text; see note 56 above) unfortunately led Jonathan Sterne to write “peasant.” See Sterne, The Audible Past, 72.

85 Price, “Automata and the Origins of Mechanism,” 23.

86 Boden, Mind as Machine, 74; Benesch, Romantic Cyborgs; Sterne, The Audible Past, 73; and Kurzweil, The Age of Intelligent Machines, 29.

87 John Cohen, Human Robots in Myth and Science (London, 1966), 69.

88 Cohen, From Beast-Machine to Man-Machine, 203.

89 Ibid., 236 n. 44.

90 The works that point to Francine Descartes are Levitt, “Animation and the Medium of Life,” 138; Humphrey, “Introduction,” xiii; Wallin, “Constructions of Chilhood,” 171–2; Jess-Cooke, Inroads, 60; Reilly, Automata and Mimesis, 68; Sawday, Engines of the Imagination, 201; Vermeir, “RoboCop Dissected,” 1036; Wilson, The Melancholy Android, 95; Maisano, “Infinite Gesture,” 63; Bloom, Descartes’ Baby, xii; Perkowitz, Digital People, 56; Berlinski, Infinite Ascent, 40; Wood, Living Dolls, 4; Ward, Virtual Organisms, 148; Brodo, “Introduction,” 4; and Gaukroger, Descartes, 1. Sarah L. Higley refers to Cohen and Price, as well as Rosenfield, quoting the last of these quoting Vigneul-Marville, and she correctly points to the denial of Francine's existence in the original tale, but she still confesses that while she “managed to round up many of the early robots and trace their retellings . . . Francine, rusting under the waves, still evades me.” Higley, “The Legend of the Learned Man's Android,” 129, n.1, and 146.

91 Panafieu, “Automata,” 142 n. 10.

92 Crevier, AI, 2. Crevier mentions this alongside actual automata that were made in the early modern period, including those by Leonardo da Vinci, Salomon de Caus, Jacques de Vaucanson, and Pierre and Louis Jaquet-Droz.

93 Gaukroger, Descartes, 1.

94 Other scholars, some of them referring to Gaukroger, have also described the automaton as Descartes's “companion,” “traveling companion,” and “female companion.” See Sawday, Engines of the Imagination, 201; Vermeir, “RoboCop Dissected,” 1036; Maisano, “Infinite Gesture,” 63; Burnett, Descartes and the Hyperbolic Quest, 39; Reilly, Automata and Mimesis, 68; Jess-Cooke, Inroads, 60; and Brodo, “Introduction,” 2.

95 Gaukroger's sources are an unnamed book on robotics (probably John Cohen) and Rosenfield, and he also refers to Anatole France in Rosenfield. See Gaukroger, Descartes, 418 n. 1.

96 On science fiction stories involving female robots see Wosk, Julie, My Fair Ladies: Female Robots, Androids, and Other Artificial Eves (New Brunswick, 2015)Google Scholar; and Kang, Minsoo, “Building the Sex Machine: The Subversive Potential of the Female Robot,” Intertexts, 9/1 (2005), 5–22 Google Scholar.

97 Wood, Living Dolls, 3–4.

98 Ibid., 4–5.

99 Also found in Brodo, “Introduction,” 4–5.

100 See note 8 above. Kara Reilly, in her 2011 book on automata in theatre history, points to the earliest manifestations of the story in Vigneul-Marville and Isaac D'Israeli in the endnotes, but in her recounting of the story in the text she provides a synopsis of the Gaby Wood story, including his journey to Sweden. Reilly, Automata and Mimesis, 68, 190 n. 47. Reilly includes Wood's description of the storm at sea that leads to the discovery of the automaton. This description is also mentioned in other versions. See Wilson, The Melancholy Android, 95; Vermeir, “RoboCop Dissected,” 1036; and Cohen, How to Love, 24.

101 Robinson and Garratt, Introducing Descartes, 102.

102 Wallin, “Constructions of Childhood,” 172.

103 Humphrey, “Introduction,” xiii. It is interesting that Humphrey also describes the box carrying the automaton as “lined with satin,” which is a detail from Anatole France's story of the salamander which was not featured in Rosenfield's translated passage. See France, La rôtisserie de la reine Pédauque, 137.

104 Cohen, How to Love, 24.

105 For instance, Carolyn Jess-Cooke has written a moving poem about Descartes the grieving father and his mechanical creation. See Jess-Cooke, “Descartes’ Daughters,” in Jess-Cooke, Inroads, 42–3. The tale is also mentioned in the Japanese science fiction anime film Ghost in the Shell II: Innocence as futuristic detectives investigate female robots that have gone rogue. One of the characters says that Descartes “lost his beloved five-year-old daughter and then named a doll after her, Francine. He doted on her. At least that's what they say.” The film, including the mention of the Descartes story, is discussed in Levitt, “Animation and the Medium of Life,” 134–43, and Muri, The Enlightenment Cyborg, 28. N. A. Sulway, in her novel Rupetta (Leyburn, 2013), does not relate the Descartes story directly but utilizes a number of elements from it about a sentient female automaton that is built in the seventeenth century.

0 notes

Text

Mysticism Artists

Contents

Sufi tradition. mysticism meaning

Free online thesaurus

Definitions. find descriptive alternatives

Noun spiritual leader. jan

Prominent 9th-century rabbi

Mysticism is the practice of religious ecstasies together with whatever ideologies, ethics, rites, …… According to Evelyn Underhill, mysticism is "the science or art of the spiritual life." ^ According to Waaijman, the traditional meaning of spirituality is …

Sufi Mysticism Quotes We collected the majority of metadata history records for Silsila-e-iftekhari.com. Silsila E Iftekhari has a poor description which rather negatively influences the efficiency of search engines index and hence worsens positions of the domain. Beautiful and inspiring quotations from the sufi tradition. mysticism meaning On Urdu Mysticism is the practice of religious ecstasies together with

Mystic Leader Synonym Synonyms for mystics at Thesaurus.com with free online thesaurus, antonyms, and definitions. find descriptive alternatives for mystics. … noun spiritual leader. jan 01, 2018 · With the successful inauguration of President Donald Trump comes the unfulfilled conclusion to both parts of the alleged angelic “presidential prophecy” of Charlie Johnston, namely that Obama will not finish his

Within the modern system of Thelema, developed by occultist Aleister Crowley in the first half of the 20th century, Thelemic mysticism is a complex mystical path designed to do two interrelated things: to learn one’s unique True Will and to achieve union with the All. The set of techniques for doing so falls under Crowley’s term Magick, which draws upon various existing disciplines and …

Mysticism In The Middle Ages The End of Europe's Middle Ages. Mysticism. Mysticism is a tradition based on the belief that the mystical experience is a key aspect of religious life. The mystical … Mysticism is the practice of religious ecstasies (religious experiences during alternate states of consciousness), together with whatever ideologies, ethics, rites, myths, legends, and magic may be related

Mysticism Superpower The power to gain strength from mystic beings, places and/or energies. Technique of esoteric energy manipulation. variation of Affinity. Not to be confused with … Siddhis are spiritual, paranormal, supernatural, or otherwise magical powers, abilities, and … "attainment", or "success". In Tamil the word Siddhar/Chitthar refers to someone who has attained siddhis and other kinds of

Nov 6, 2015 … Magick and mysticism are nothing new. Here's five legendary artists and writers that tapped deeply into the occult for their inspiration.

Mysticism Meaning On Urdu Mysticism is the practice of religious ecstasies together with whatever ideologies, ethics, rites, myths, legends, and … In his Arabic language work Emunoth ve-Deoth ("Beliefs and Opinions"), Saadia Gaon, a prominent 9th-century rabbi and the first great Jewish philosopher, argues that "the world came into existence out of nothingness".This thesis was first translated into Hebrew as

from all sides the wanderers come but the goal of their pilgrimage is the same. gnôthi seauton : know your Self ! Mysticology : the Study of the Mentality of Mystics

It is inevitable that inspired art and illumined writing should arouse the beginning of mystical feelings in the hearts of those prepared and sensitive enough to …

The despatialization of post-Industrial society provides some benefits (e.g. computer networking) but can also manifest as a form of oppression (homelessness, gentrification, architectural depersonalization, the erasure of Nature, etc.)

45: Why Artists Are Turning to Mysticism. Artsy Editors. Aug 17, 2017 6:08 pm. You can find the Artsy Podcast on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, Pocket Casts, or the …

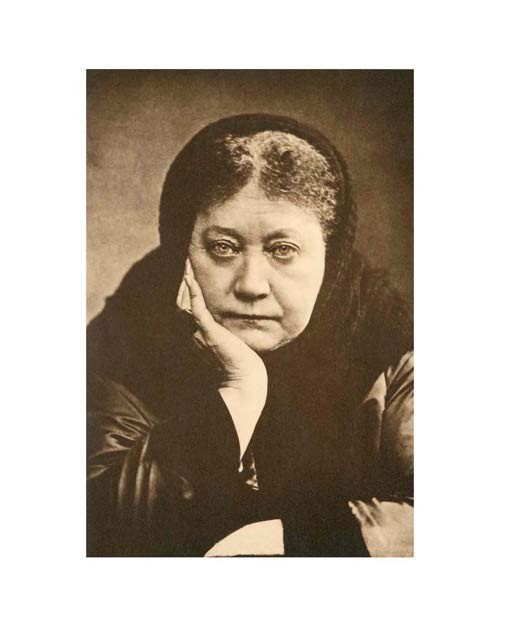

Editor's Statement: Mysticism and Occultism in. Modern Art. By Linda Dalrymple Henderson. T he articles in this issue of Art Jour- nal were chosen from the more …

ARTISTS. You can see a curated selection of our video, multimedia work in the digital archive, or explore the website of each artist below.

0 notes

Video

youtube

Extra dimensions of space—the idea that we are immersed in hyperspace—may be key to explaining the fundamental nature of the universe. Relativity introduced time as the fourth dimension, and Einstein’s subsequent work envisioned more dimensions still--but ultimately hit a dead end. Modern research has advanced the subject in ways he couldn’t have imagined. John Hockenberry joins Brian Greene, Lawrence Krauss, and other leading thinkers on a visual tour through wondrous spatial realms that may lie beyond the ones we experience. The World Science Festival gathers great minds in science and the arts to produce live and digital content that allows a broad general audience to engage with scientific discoveries. Our mission is to cultivate a general public informed by science, inspired by its wonder, convinced of its value, and prepared to engage with its implications for the future. Subscribe to our YouTube Channel for all the latest from WSF. Visit our Website: http://www.worldsciencefestival.com/ Like us on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/worldscience... Follow us on twitter: https://twitter.com/WorldSciFest Original Program date:June 5, 2010 MODERATOR: John Hockenberry PARTICIPANTS: Escher String Quartet, Brian Greene, Lawrence Krauss, Linda Dalrymple Henderson, Shamit Kachru Brian Greene and a moment of physics. 0:29 Einstein and what is gravity. 04:40 Three dimensional space and the warps and curves of gravity. 06:33 What does 3D space look like? 10:55 Escher String Quartet. 16:34 John Hockenberry Introduction. 21:22 Participant Introductions. 24:17 The history of multi-dimensions. 25:43 Who preceded mathematician Kaluza. 31:14 Whats the difference between math and physics 33:21 Graviton's and quantum particles. 40:42 Do experimental physicists except the math as truth? 45:45 Quarks, Leptons and Forces. 53:10 The Calabi-Yau manifold 55:34 Einstein's lunar eclipse experiment. 01:00:00 Describing the fourth dimension 01:05:56 Will there be discoveries outside of just mathematics? 01:07:10 Physics... It is not easy and it takes along time. 01:15:25 Everything we see is just pollution. 01:19:35 The excitement the super string theory. 01:23:22

0 notes

Photo

Hilma af Klint. Tidsandans visionär / Visionary, Edited by Kurt Almqvist and Louise Belfrage, Texts by Julia Voss, Tracey Bashkoff, Isaac Lubelsky, Linda Dalrymple Henderson, Marco Pasi, Bokförlaget Stolpe, Stockholm, 2019 [Karma Bookstore, New York, NY]

#graphic design#art#drawing#geometry#pattern#catalogue#catalog#cover#hilma af klint#kurt almqvist#louise belfrage#julia voss#tracey bashkoff#isaac lubelsky#linda dalrymple henderson#marco pasi#bokförlaget stolpe#karma#2010s

35 notes

·

View notes

Photo

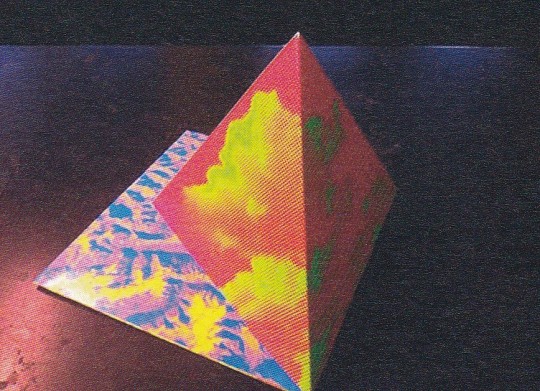

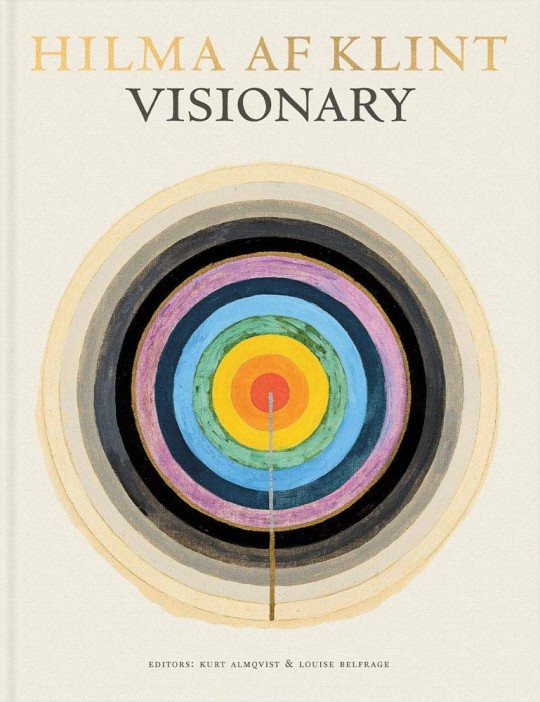

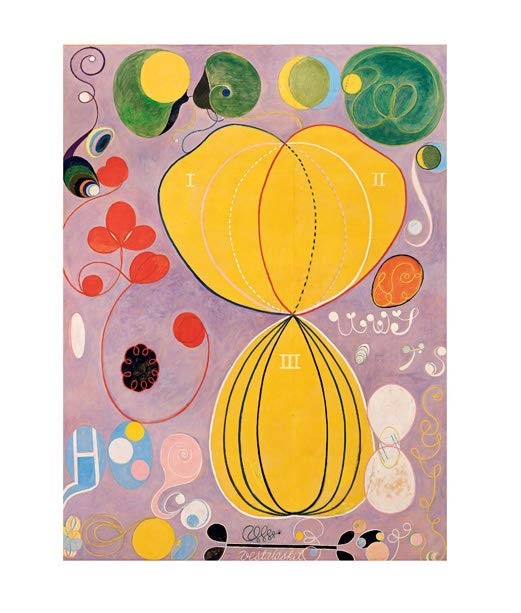

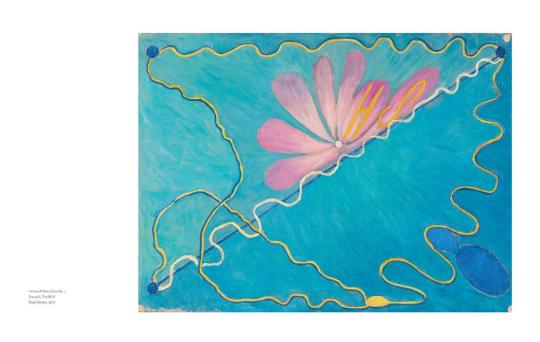

Hilma af Klint Visionary

edited by Kurt Almqvist & Louise Belfrage

Introduction by Daniel Birnbaum. Text by Julia Voss, Tracey Bashkoff, Isaac Lubelsky, Linda Dalrymple Henderson, Marco Pasi.

Bokförlaget Stolpe AB, Stockholm 2020,124 pages, ISBN 9789163972034

euro 40,00

email if you want to buy :[email protected]

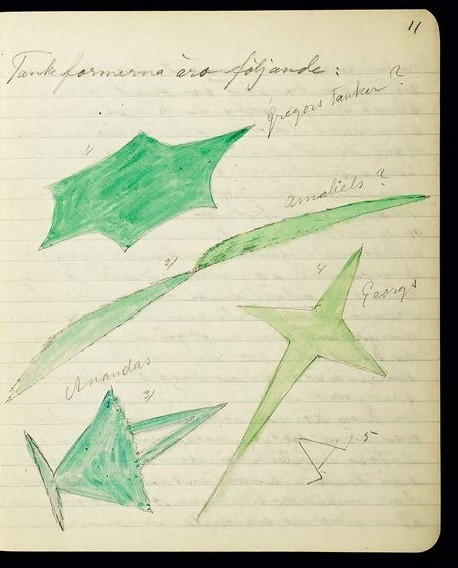

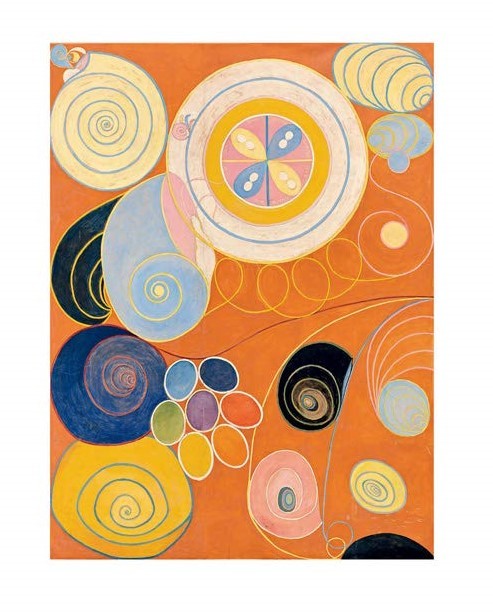

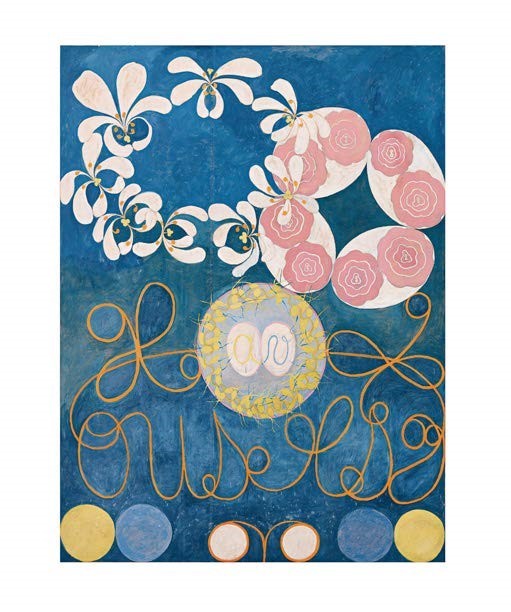

The 2018 exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum in New York, Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future, introduced the general public to the abstract mystical masterpieces of Swedish painter Hilma af Klint (1862–1944). Based on a seminar held at the Guggenheim Museum at the opening of this acclaimed exhibition, this volume compiles the insights of the seminar’s contributors alongside reproductions of works, archival photographs and images from af Klint’s journals.

Hilma af Klint: Visionary explores the social and spiritual movements that appeared at the turn of the 20th century, inspiring the pioneers of modernism and abstract art: Kandinsky, Mondrian, Malevich and af Klint. What was the zeitgeist that inspired such an eruption in abstract art? What were the conditions that created Hilma af Klint? Academics and experts Julia Voss, Tracey Bashkoff, Isaac Lubelsky, Linda Dalrymple Henderson and Marco Pasi each take a different approach. Voss analyzes af Klint's biography, pinpointing five important events in her life; Bashkoff presents her connection to Hilla Rebay and her plans for the building of a temple; Lubelsky traces the origins of theosophy in New York; Henderson examines the occult and science; and Pasi considers esotericism’s changing role in culture.

31/03/20

orders to: [email protected]

ordini a: [email protected]

twitter:@fashionbooksmi

instagram: fashionbooksmilano

designbooksmilano

tumblr: fashionbooksmilano

designbooksmilano

#Hilma af Klint#art exhibition catalogue#spirituals movements#esotericism#fashion inspirations#fashionbooksmilano

43 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#Linda Dalrymple Henderson#book cover#cover design#non-Euclidean geometry#Euclidean#geometry#non-Euclidean#art#modern art

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

CFP: Histories of Media Art, Science and Technology (Krems, 30 Nov-2 Dec 17)

Krems / Wien, November 30 - December 2, 2017

Deadline: Mar 26, 2017

The 7th International Conference on the Histories of Media Art, Science

and Technology titled RE:TRACE focuses on an evaluation of the status

of the meta-discipline MediaArtHistories today.

More than a decade after the first conference founded the field now

recognized worldwide as a significant historical inquiry at the

intersection of art, science, and technology, Media Art Histories is

now firmly established as a dynamic area of study guided by changing

media and research priorities, drawing a growing community of scholars,

artists and artist-researchers.

Immersed in both contemporary and historiographical aspects of the

digital world, we explore the most immediate socio-cultural questions

of our time: from body futures, information society, and media

(r)evolutions, to environmental interference, financial virtualization,

and surveillance. And we do so through a fractal lens of inter- and

trans-disciplinarity, bridging art history, media studies,

neuroscience, psychology, sociology, and beyond. MediaArtHistories is a

field whose theory, methods, and objects of study interweave with and

overlay other disciplines.

The organizing committee invites researchers of different areas,

disciplines and practices to submit individual papers, posters and full

panels with new and original research preferably in the following

themes:

• MediaArtHistories – historiographies and futures of an ever-emerging

field

• Institutional histories of Media Art

• Media Art & Politics (surveillance, climate, visualizations, etc.)

• Collecting media art / Media Art market

• Archiving, preserving and representing Media Art

• Re-Use of cultural heritage data, including education, learning and

research

• Methodologies and research tools for MediaArtHistories with a focus

on Digital Humanities

�� International and local histories and practices of media art

• (Post-)Colonial experiences and non-Western histories of media art,

science and technology

• Paradigm shift – Digital vs. Post-Digital Theory

• Alternative histories for Media Art in relation to newly evolving or

unexpected fields.

• Models and perspectives of research fields adapted across traditional

disciplinary lines.

• New symbolic architecture of digital super companies (Apple, Amazon,

Microsoft, FB, Google)

The conference program will include competitively selected,

peer-reviewed individual papers, panel presentations and posters, as

well as a small number of invited speakers. Presentations will be

delivered in a range of formats, from panel discussions to a poster

session. We particularly encourage submissions by researchers from

international contexts outside of Europe and North America.

Keynote lectures by internationally renowned, outstanding leaders in

the field, will deliberate on the central themes of the conference

series, its histories and futures.

Submission Deadline: March 26, 2017

Notification of acceptance will be announced by April 30, 2017.

Individual proposals for papers should consist of a max. 250-word

abstract with title. Proposals for full panels should consist of a max.

500-word abstract outlining the panel and individual topics of

confirmed speakers. Submission language is English. Submitters should

upload a short bio file (Word), no longer than ½ page per person. The

short bios will be used on the conference website together with your

abstracts.

Initiated by the Media Art Histories Board (Steering Committee):

Prof. Dr. Sean CUBITT (Deputy Head of Department & PhD Tutor / Media

and Communications / Goldsmiths University of London / UK); Univ.-Prof.

Dr. habil. Dr.h.c. Oliver GRAU, MAE (Head of Dept & Chair Professor in

Image Science / Danube University / AT); Dr. Linda Dalrymple HENDERSON

(David Bruton, Jr. Centennial Professor in Art History / History /

University of Texas at Austin / US); Dr. Andreas BROECKMANN (Leuphana

Arts Program, Leuphana University of Lüneburg, GER); Prof. Dr. Erkki

HUHTAMO (Departments of Design Media Arts, and Film, Television, and

Digital Media / University of California Los Angeles / US); Prof. Dr.

Douglas KAHN (Professor of Media and Innovation / National Institute of

Experimental Arts (NIEA) / University of New South Wales, Sydney / AU);

Prof. Dr. Machiko KUSAHARA (School of Letters, Arts and Sciences /

Waseda University / Tokyo, Japan); Prof. Dr. Tim LENOIR (Kimberly J.

Jenkins Chair for New Technologies in Society / Duke University / US);

Prof. Dr. Gunalan NADARAJAN (Dean / Stamps School of Art & Design /

University of Michigan / US); Prof. Dr. Paul THOMAS (Director / Fine

Arts at College of Fine Art / University of New South Wales /AU)

MAH Honorary Board: Martin KEMP, Jasia REICHARDT, Itsuo SAKANE, Peter

WEIBEL, Douglas DAVIS †, Rudolf ARNHEIM †

Venues: Danube University / Located 70km from Vienna in the UNESCO

World Heritage Wachau region, Danube University is the only public

university in Europe specializing in advanced continuing education by

offering low-residency degree programs for working professionals and

life-long learners. Located at both a modern university campus and in

the Göttweig Monastery, the Dept. for Image Science is an

internationally unique institution for research and innovative teaching

with an international faculty, at this point 120 scholars from various

nations and disciplines. The innovative approach of the Department for

Image Science with the close connection to practice has developed the

Archive of Digital Art and founded in 2006 the low-residency

MediaArtHistories-Advanced, MA answering the need for international,

post-graduate studies.

Vienna / The vibrant capital of the Republic of Austria in Central

Europe meeting international travel standards with safe and exciting

surroundings that embrace culture both old and new. Planning for Vienna

is being organized with partner institutions and colleagues. Fast and

frequent public transportation between Vienna and Krems allows for a

blending of two locations into one venue, distributing separate days in

each venue.

Supported by Academia Europaea

Links:

Trace call for papers – www.mediaarthistory.org/retrace

MediaArtHistories-Advanced, MA – www.mediacultures.net/mah

Archive of Digital Art – www.digitalartarchive.at

0 notes

Photo

'Hilma af Klint: Visionary' is Back in Stock! Featuring 220 color reproductions, this volume takes off from a seminar held at the opening of the groundbreaking 2018 @guggenheim show, compiling essays and insights by contributors including Daniel Birnbaum, Julia Voss, Tracey Bashkoff, Isaac Lubelsky, Linda Dalrymple Henderson and Marco Pasi. This is essential reading for anyone interested in the work of one of the most original artists of the 19th-20th centuries—a trailblazer of abstraction, spiritualism, and her own brand of feminism, and most certainly a visionary. Stay tuned for more books on af Klint—including a major monograph from Hatje Cantz and a stupendously produced 7-volume catalogue raisonné from Bokförlaget Stolpe—in our forthcoming Fall 2020 catalog!⠀ ⠀ Please order from your local independent #bookstorehero — many are still shipping or offering curbside pickup! You can also order from local independents via @bookshop_org or #indiebound⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ Or order directly from @artbookps1 @artbookhwla or artbook.com⠀ ⠀ #hilmaafklint #bokförlagetstolpe #visionaryart #spiritualism @daniel.birnbaum @spiraltemple @marco.sf.pasi ⠀ @hatjecantzverlag ⠀ Thanks for the pics @markwilliampearson https://www.instagram.com/p/CAGBDrFJpl4/?igshid=hpykhgfmkarm

0 notes

Photo

Love @tau_au Love @arcanabooks !! #Repost @arcanabooks ・・・ Tauba Auerbach: S v Z Published by D.A.P./SFMOMA. ● Purchase Link in Bio ● Introduction and text by Joseph Becker, Jenny Gheith, Linda Dalrymple Henderson. Afterword by Neal Benezra. Part artist's book, part exhibition catalog, this book chronicles Tauba Auerbach’s multimedia syntheses of abstraction, science, graphic design and typography Tauba Auerbach studies the boundaries of perception through an art and design practice grounded in math, science and craft. Published in conjunction with the first major survey of the artist’s work, this volume, designed by Auerbach in collaboration with David Reinfurt, spans 16 years of her career, highlighting her interest in concepts such as duality and its alternatives, interconnectedness, rhythm and four-dimensional geometry. Encapsulating Auerbach’s longstanding consideration of symmetry, texture and logic, the title S v Z offers a framework for this volume’s typeface, design and structure. Images of more than 130 paintings, drawings, sculptures and artist’s books created between 2004 and 2020 are mirrored by a comprehensive selection of related reference images, illuminating her multifaceted practice as never before. Essays by Joseph Becker, Jenny Gheith and Linda Dalrymple Henderson provide further context for the work. The book contains original marble patterns created specially for the book by the artist on both the endpapers and the edges of the book block. The cover is lettered in Auerbach’s calligraphy, applied in black foil on a silver paper. The typeface was designed by David Reinfurt with Auerbach expressly for this publication, and is based on her handwriting. @tau_au @sfmoma @artbook #bookstorehero https://www.instagram.com/p/B_r6HrFJoU0/?igshid=jpvnw3gtvdtk

0 notes

Photo

Congratulations @tau_au on this one-of-a-kind retrospective book experiment!! #Repost @tau_au ・・・ The appetizer that comes a year before the main course........ Strangely, the book I designed with David Reinfurt @_o_r_g for my survey show at @sfmoma is emerging now, but the show, which was also supposed to open this month, is postponed until 2021. David and I gathered over 450 images and created several original typefaces. There are texts by Jenny Gheith, Linda Dalrymple Henderson and Joseph Becker. This puppy is copublished and distributed by @artbook, so if you’re inclined to shop online (personally feeling very mixed about this- both wanting to support small businesses and also keep all delivery people out of harm’s way) please use it as a opportunity to support an independent book store and not you-know-who. @spoonbillbooks @monographbookwerks @arcanabooks @192books @harvardbookstore @bookshop_org @parklifesf @booksoup all have it. ** All #bookstorehero #bookstoreheroes !! https://www.instagram.com/p/B-uhvDQJ-N9/?igshid=pqb89p4kobel

0 notes

Photo

#Repost @tau_au ・・・ I cannot believe this book exists!!!! Thank you to my co-designer David Reinfurt @_o_r_g, who was a great friend and partner in crime here. Published by @sfmoma and @artbook in connection to a survey at the museum in April. Essays by Linda Dalrymple Henderson, Jenny Gheith and Joseph Becker. https://www.instagram.com/p/B8eE_RcJBGz/?igshid=85hm53zm1sir

0 notes