#literary geopolitics

Text

Thinking About Thinking: A Novel of Tomorrow's Happy World

Thinking About Thinking: A Novel of Tomorrow’s Happy World

The Big Ball of Wax: A Novel of Tomorrow’s Happy World by Shepherd Mead. Here’s the cover of the Ballantine Books mass-market paperback I read back in the day. It’s now available on Kindle.

That’s the subtitle of Shepherd Mead‘s 1954 novel, The Big Ball of Wax.

Do you wonder – perhaps with trepidation and creeping anxiety – what the socioeconomic impacts of Virtual Reality (VR) might be?

Well,…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

for anyone who is interested in free webinars related to Japanese studies on youtube concerning topics such as:

tokugawa era

samurai

east asia pacific and east asia current geopolitical information

food culture and history

yokai

mythology

sexuality in japan

gender

fashion

kawaii culture, etc etc

Japan foundation new york (in the 'live' category): they have a lot of seminars on video games in japan based on a more thematic, cultural and social analysis as well as literary. they do similar analysis for other popular culture such as manga, shojo manga, bl manga etc

just cuz it aint easy finding resources if one is studying japanese culture (jstor was my saviour)

40 notes

·

View notes

Note

You absolute dunce. Either wake up, or stop trying to pretend you care about what’s happening on Gaza. It’s not a “war,” and it’s not a “conflict.” It’s a full-fledged genocide. A war or conflict can only occur between two free nations, who are more or less standing on equal ground. That is NOT what is happening between Palestine and Izrahell. In what kind of a conflict/war does one side control the water, electricity, food, aid etc going into the other side? None. It’snotreal is a parasitic, violent occupation, and the Palestinian people have every right to resist. You have literal Holocaust survivors begging for ceasefire and calling it a genocide, not wanting it to continue. But of course, zios are just modern-day nazis and don’t care about what even the actual Jews, the living Holocaust survivors have to say.

omg my first antisemitic anon hate!! thank you!!!!

Anyone who I actually care about knows who I am as a person and how I feel about the sanctity of human life, so I don't really care about your opinion of me, and especially don't feel the need to indulge in a litmus test on geopolitical politics from you of all people, hope this helps!!

Anyway, I hope you take constructive criticism.

Your review:

Delivery: 6/10.

You get points for decent grammar and sentence structure. It was easy to read, and I like how you used quotation marks correctly, so bonus points for that. First sentence was a good hook, but the incorrect use of commas at the end kinda threw me off a little :/

Creativity: 1/10.

Literally, did you even try?? Not one single independent thought was expressed. Boring. Seen it before. Try harder, please. If you're going to try to play with words, make sure you actually know what they mean; you semantically can't do that to the word "Israel," sorry. It's a Hebrew word, so butchering it in English just feels really juvenile. Would like to have seen better effort with that.

Word choice: 0/10.

You would have gotten points for the words "dunce," because I haven't heard that word since like the 1930s, and "parasitic," because I thought that was an interesting use of the word, but unfortunately you got points taken off for using a KKK slur :/

Literary devices: -17/10.

The Holocaust inversion was not part of the rubric, so I had to take extra points off for that, and unfortunately it went into the negatives. Sorry :/

(I would have given you points for the use of irony, when you equated a KKK slur for Jews to the entity responsible for the worst genocide of Jews in history, but I'm absolutely sure that you did not use it on purpose, so the points were voided.)

Other notes:

The choice to be a coward (anonymous) really added to the ambiance of the message, but unfortunately I don't see a spot on the rubric for that, so no points were awarded.

Overall: -10/40 = -25%. Congrats, you failed! Disrespectfully, go fuck yourself!

.עם ישראל חי

#and for the record keep our dead and our survivors out of your mouth#my great grandmother who survived auschwitz actually does not need you to speak for her thanks!!#antisemitism#anon hate#jewish#jumblr#antisemitic dickwad#עם ישראל חי mother fucker#i would say when they go low we go chai but i am in the basement with this one actually

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

The arrival of the Mongols ended the illusion of the political unity of the Kyivan realm and put an end to the very real ecclesiastical unity of the Rus’ lands. The Mongols recognized two main centers of princely rule in Rus’: the principalities of Vladimir-Suzdal in today’s Russia and Galicia-Volhynia in central and western Ukraine. Constantinople followed suit, dividing the Rus’ metropolitanate into two parts. The political and ecclesiastical unity of the Kyiv-centered Rus’ Land had disintegrated. The Galician and Vladimirian princes were now busy building Rus’ lands of their own in their home territories. Although they claimed the same name, “Rus’,” the two principalities followed very different geopolitical trajectories. Both had inherited their dynasties from Kyiv, which was also their source of Rus’ law, literary language, and religious and cultural traditions. Both found themselves under alien Mongol rule. But the nature of their dependence on the Mongols differed.

In the lands of what is now Russia, ruled from Vladimir, the Mongol presence lasted until the end of the fifteenth century and eventually became known as the “Tatar yoke,” named after Turkic-speaking tribes that had been part of the Mongol armies and stayed in the region after the not very numerous Mongols left. The view of Mongol rule as extremely long and severely oppressive has been a hallmark of traditional Russian historiography and continues to influence the interpretation of that period of eastern European history as a whole. In the twentieth century, however, proponents of the Eurasian school of Russian historical writing challenged this negative attitude toward Mongol rule. The history of the Mongol presence in Ukrainian territory provides additional correctives to the traditional condemnation of the “Tatar yoke.” In Ukraine, ruled by the Galician and Volhynian princes, the Mongols were less intrusive and oppressive than they were in Russia. Their rule was also of shorter duration, effectively over by the mid-fourteenth century. This difference would have a profound impact on the fates of the two lands and the people who settled them.

Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of Europe: A History of Ukraine

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Napoleon as the black angel and Tsar Alexander the white angel

This is from an excerpt about Madame de Krüdener, a religious mystic during the Napoleonic era, from the memoir of Leon Dembowski, Moje Wspomnienia, Volume 1. (Source)

A bit about her career:

“Her literary activity was followed by various writings and pamphlets about humanity, in which she plunged into mysticism and presented herself as a prophetess. From 1806 to 1814, despite poor health and exhausted strength, she began to walk through Russia, northern Germany, the Netherlands and France, gathering listeners around her, handing out money and pamphlets.”

Her teachings:

“The principles of her teaching, both repeated in writings and disseminated by living words, consisted in implementing the principles of the early Christian Church and abandoning battles and wars. Moreover, the abolition of the death penalty, the return of freedom to subjugated nationalities and the strict exercise of Christian mercy completed this philanthropic system.”

In which she finds her ideas to be at odds with greater geopolitical events and social currents of her time:

“These sublime and beautiful thoughts, which probably once prevailed in beliefs, had few supporters in the era of Mme de Krüdener’s activity. All Europe seemed to be one camp, and Napoleon, on the one hand, and English intrigues, on the other, were completely destroying it. Everyone was thinking about the marshal’s baton, principalities, subsidies that Napoleon lavished, and while some were longing for constant conquests, others were thinking about how to break Napoleon’s yoke. Therefore, her apostolate, which could only reach places where the French eagles had not reached, did not really reach her convictions. Seeing that the path of persuasion would not reach her goal, she began to prophesy and predict the fall of the black angel (Napoleon), who would be struck down by the white angel (Alexander).”

What’s interesting is that the duel between Britain and France is diagnosed as the source of Madame de Krüdener’s problems, so she turns to a third party (Russia) to be the savior.

Her influence over Tsar Alexander I:

“As a result, Alexander wanted to know her, and it must be admitted that this partly corresponded to his inclination towards mysterious things, because many similar examples can be cited in the life of this monarch. […] Throughout all these years, Mme de Krüdener constantly worked on Emperor Alexander, having established influence mainly over his mind, pushing him towards mysticism, religiosity and abandonment of liberal principles.”

The author makes note that Madame de Krüdener and Tsar Alexander died around the same time.

Bold letters by me.

Pages 180-182

#Madame de Krüdener#Krüdener#Barbara von Krüdener#Leon Dembowski#Dembowski#Moje Wspomnienia#napoleonic era#napoleonic#Napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#religious history#first french empire#French empire#Russia#russian history#french history#19th century#france#history#imperial Russia#tsar Alexander I#tsar Alexander

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

I. part of "The Knight-Paladin Alphabet Headcanons"

I am creating headcanons for the Knight-Paladin Gelebor right here.

Warning, there will be NSFW ones too, though way later (they aren't there yet).

Here are a 2 letters from the first chapter:

G — Grief — How do they process grief?

It is said that Auri-El could do naught but teach the Elvenfolk to suffer with dignity.

This paraphrase might not completely fall in line with the Falmer doctrines of faith, but the theme of being ennobled by martyrdom is common, starting with the very initiation to enlightenment undertaken in the pilgrimages to the Chantry of Auri-El.

True to his beloved culture, perhaps even influenced by it, he tends to mourn quietly. The Knight-Paladin seldom weeps openly. He harbors no desire for pity, for he believes a guardian ought to remain silent about his own sorrows. To impose his emotions upon another strikes him not only as inappropriate but profoundly selfish.

Therefore, he does not showcase the level of hurt he's under — a subtle display of melancholy at most. To be exact, he refrains from presenting strong emotions whatsoever, whether they're positive, negative or ambivalent.

K — Knowledge — Do they like learning new things? Do they possess any piece of wisdom unknown to others, or is perhaps forbidden?

Needless to say, he possesses boundless knowledge of the old ways and Nirn from the dawn of the First Era, which would prove a miraculous source of information for today's scholars but probably not to anyone else. He is willing to share everything about the functioning of the Snow Elven Empire, Falmeri Pantheon, Falmereth’s traditions and convenances. He doesn’t necessarily have any forbidden knowledge, he has always strayed far from all wicked branches of magic (unlike him …).

He loves learning new things, always intently listening to any intel from adventurers if they would ever want to share a piece of their wisdom with him. The few books he took with him to the Darkfall Cave he reread countless times and on rare occasions a soul would graze him with new information about the outside world. Bit by bit, he learned of the change of the end of Atmorans’ active slaughtering of the Snow Elves, Chimer to Dunmer transformation, the disappearance of the Dwemer, the Oblivion crisis…

If the Dragonborn would allow him so, he would politely inquire about all interesting questions that would pop in his mind on a guard for centuries. To be frank, any new information would be fascinating to him. Socioeconomic news, geopolitical landscape, developments in technology, or something about culture and arts — all he will lap up with utmost attention.

There are, of course, certain facts he is better off without being aware of. He certainly would fare far more peacefully without being notified about the existence of such pieces of art like “The Slaying of the Falmer Princes” or “Conquest of the Falmer”... Only Auri-El knows how the stoic Knight-Paladin might react to those obscene literary works.

Lord, help him if he discovers Brynjolf’s gig as a salesman.

#gelebor#knight paladin gelebor#gelebor imagine#forgotten vale#snow elf#auriel#gelebor x reader#dawnguard#falmer

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

In honor of Juneteenth, we are featuring four books in our collection by queer Black and African authors. Descriptions of the books are below the read more.

Lez Talk: A Collection of Black Lesbian Short Fiction (2016) ed. by S. Andrea Allen & Lauren Cherelle.

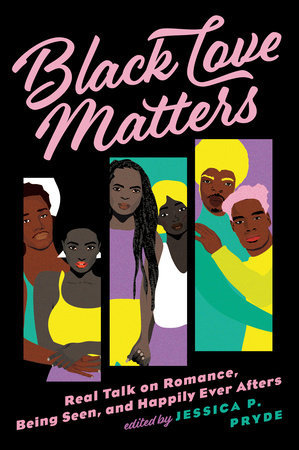

Black Love Matters: Real Talk on Romance, Being Seen, and Happy Ever Afters (2022) ed. by Jessica P. Pryde

The Black Imagination: Science Fiction, Futurism and the Speculative (2011) ed. by Sandra Jackson and Julie E. Moody-Freeman

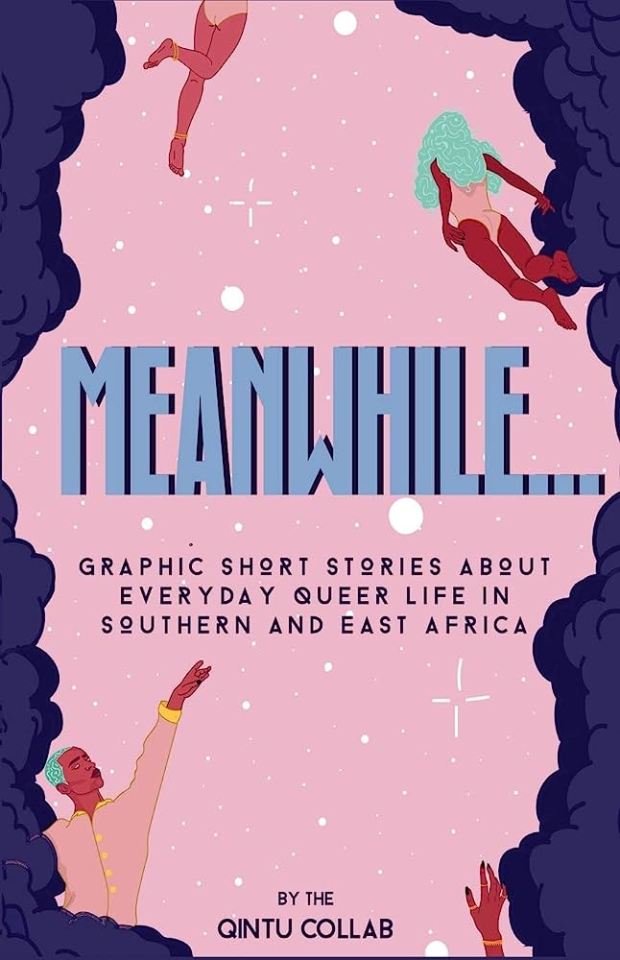

Meanwhile: Graphic Short Stories about Everyday Queer Life in Southern and East Africa (2019) by the Qintu Collab

The Browne Popular Culture Library (BPCL), founded in 1969, is the most comprehensive archive of its kind in the United States. Our focus and mission is to acquire and preserve research materials on American Popular Culture (post 1876) for curricular and research use. Visit our website at https://www.bgsu.edu/library/pcl.html.

Lez Talk

A necessary and relevant addition to the Black LGBTQ literary canon, which oftentimes over looks Black lesbian Writing, Lez Talk is a collection of short stories that embraces the fullness of Black lesbian experiences. The contributors operate under the assumption that "lesbian" is not a dirty word, and have written stories that amplify the diversity of Black lesbian lives. At once provocative, emotional, adventurous, and celebratory, Lez Talk crosses a range of fictional genres, including romance, speculative, and humor. The writers explore new subjects and aspects of their experiences, and affirm their gifts as writers and lesbian women.

Black Love Matters

An incisive, intersectional essay anthology that celebrates and examines romance and romantic media through the lens of Black readers, writers, and cultural commentators, edited by Book Riot columnist and librarian Jessica Pryde.

Romantic love has been one of the most essential elements of storytelling for centuries. But for Black people in the United States and across the diaspora, it hasn't often been easy to find Black romance joyfully showcased in entertainment media. In this collection, revered authors and sparkling newcomers, librarians and academicians, and avid readers and reviewers consider the mirrors and windows into Black love as it is depicted in the novels, television shows, and films that have shaped their own stories. Whether personal reflection or cultural commentary, these essays delve into Black love now and in the past, including topics from the history of Black romance to social justice and the Black community to the meaning of desire and desirability.

Exploring the multifaceted ways love is seen--and the ways it isn't--this diverse array of Black voices collectively shines a light on the power of crafting happy endings for Black lovers.

Jessica Pryde is joined by Carole V. Bell, Sarah Hannah Gomez, Jasmine Guillory, Da'Shaun Harrison, Margo Hendricks, Adriana Herrera, Piper Huguley, Kosoko Jackson, Nicole M. Jackson, Beverly Jenkins, Christina C. Jones, Julie Moody-Freeman, and Allie Parker in this collection.

The Black Imagination

This critical collection covers a broad spectrum of works, both literary and cinematic, and issues from writers, directors, and artists who claim the science fiction, speculative fiction, and Afro-futurist genres. The anthology extends the discursive boundaries of science fiction by examining iconic writers like Octavia Butler, Walter Mosley, and Nalo Hopkinson through the lens of ecofeminist veganism, post-9/11 racial geopolitics, and the effect of the computer database on human voice and agency. Contributors expand what the field characterizes as speculative fiction by examining for the first time the vampire tropes present in Audre Lorde’s poetry, and by tracing her influence on the horror fiction of Jewelle Gomez. The collection moves beyond exploration of literary fiction to study the Afro-futurist representations of Blacks in comic books, in the Star Trek franchise, in African films, and in blockbuster films like Independence Day, I Robot, and I Am Legend.

Meanwhile

The lived realities of young queer people in African contexts are not well documented. On the one hand, homophobic political discourse tends to portray queer people as 'deviant' and 'unAfrican', and on the other, public health research and advocacy often portrays them as victims of violence and HIV. Of course, young queer lives are far more diverse, rich and complex. For this reason, the Qintu Collab was formed to allow young queer people from a few African countries to come together, share experiences and create context-specific, queer-positive media that documents relatable stories about and for queer African youth. We see this as a necessary step in developing a complex archive of queer African life, whilst also personalising queer experiences and challenging prejudicial stereotypes. The Collab is made up of eighteen queer youth from Botswana, Kenya and Zimbabwe, two academics, three artists and a journalist. We first worked in small groups in each country through a range of creative participatory methods that focused on personal reflection and story-telling. Young people created personal timelines, and made visual maps of their bodies, relationships, and spaces. We then had group discussions about themes that emerged to help decide what to include in the comic works. At the end of 2018, we all came together in Nairobi, Kenya, for a week to collaborate on this comic book, and a set of podcasts on similar topics. We worked through various ways of telling stories, and developed significant themes, including family, religion and spirituality, social and online queer spaces, sex, and romantic relationships. Each young person created a script and laid out the scenes for a comic that told a short story from their lives. They then worked one-on-one with an artist to finesse those ideas into a workable comic, and the artists thereafter developed each story through multiple rounds of feedback from the story's creator and the rest of the group

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

From von Bertalanffy’s “system of systems,” LeClair derived six criteria to define the genre. (1) Systems novels respond to “accelerating specialization (and alienation) of knowledge and work”; “tremendous growth in information and communications”; “large-scale geopolitical crises over energy and exchange (of goods information and money); and “planetary threats produced by man yet now seemingly beyond his control.” (2) They bridge the gap between C. P. Snow’s “two cultures,” the literary and the scientific. (3) “The themes of systems theory are the master subjects of literary modernism—process, multiplicity, simultaneity, uncertainty, linguistic relativity, perspectivism—but in a new larger scale of spatial and temporal relations (the ecosystem) that reflects the new scale of sociopolitical experience, including the rise of multinational corporations and global ecology.” (4) In terms of character, “‘Systems man’ is more a locus of communication and energy in a reciprocal relationship with his environment than an entity exerting force and dictating linear cause-effect sequences.” (5) Systems theory “offers the novelist a contemporary model for hypothetical formulations of wholes.” (6) Systems theory provided a “a doubled or split relation to the idea of mastery, criticizing man’s attempt to master his ecosystem and yet, in its on synthetic act, ‘mastering’ various specialties in large abstractions in order to communicate beyond specialties.”

I have quoted liberally from LeClair’s original formulations to give a sense of the way that in setting new terms for the understanding of these novels he was deviating from the ordinary modes in which we talk about novels. Part of his project was to bring fresh academic attention to DeLillo, whom he saw as neglected by scholars, and so he sought the razzle-dazzle of a theory yet to infiltrate English departments, one that brought with it fresh jargon. It turned out we could talk about these books and understand them in a way close to that which LeClair intended without resorting to this language. Novels teach you how to read them, and they teach novelists how to write more novels. I have tried to reformulate LeClair’s theses on my own in the simplest terms: (1) too much information; (2) the inescapability of science; (3) the incomprehensible scale of things; (4) the limits of any man’s perceptions; (5) the need to see things whole; (6) the impossibility of mastery even when it’s the artist’s duty.

It could be argued that these conditions have applied to any novelist or writer of extended narratives at any time in the history of the form. Wasn’t Dickens synthesizing massive amounts of information? Didn’t Shakespeare have to consider science or cosmology? Wasn’t Nick Carraway telling a story whose historical dimensions he couldn’t entirely grasp? Didn’t Herman Melville and George Eliot aspire to put the whole world into their novels? Hasn’t total mastery eluded every writer from Homer down to Joyce and Beckett? Novels emerge from a long cyclical tradition. Since LeClair coined the term critics have recast the systems novel as a return of the encyclopedic novel or as the maximalist novel, terms of long standing that can easily be projected into the past. But the differences between these terms are useful to discern. An encyclopedia is a container of knowledge that seeks to include everything and organize it. Its mode of organization is arbitrary: the alphabet. The maximum is simply a term of scale: everything will be as big as possible. But the system will not only accommodate everything but also its movement and change. The theory comes from a biologist, and the metaphor accommodates living things, even living things moving deathward.

Christian Lorentzen, Shocks to the System: Don DeLillo’s novels of the Cold War and its aftermath

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gaza Has Exposed Journalistic and Academic “Neutrality” as the Conservative Deflection It Always Was

After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, elite liberal institutions had no problem picking a side. After 37,000 Palestinians are killed by Israel—things are now more complicated.

Suddenly, it seems, taking a stand on oppression by journalistic institutions, universities and prestige nonprofits has fallen out of fashion. So, what changed? It wasn’t the principle of liberal intervention on behalf of the oppressed, but rather the geopolitical utility and racial makeup of those being oppressed.

In February 2022, virtually the whole of the liberal taste-making and knowledge-production world responded with unequivocal outrage at Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, issuing statements of solidarity, condemnations of Russia, and a boycott of Russian cultural products. This conviction of standing up for those under siege officially expired over the past eight months — and it’s worth taking inventory of why and how this happened.

Last month, the National Writers Union (NWU) released a detailed report tracking “44 cases of retaliation that impacted more than 100 media workers” in response to “the perception that they support the Palestinian cause or are critical of the Israeli government.” The survey, which covered the period from October 7, 2023 to February 1, 2024 in North America and Europe, found that workers faced de-platforming, firing, suspension and other forms of discipline, with journalists of Middle Eastern or North African descent and those who identify as Muslim especially impacted. “Western media workers have faced a wave of retaliation for speaking up against or critically covering Israel’s war on Gaza — and in particular, for voicing support for Palestinians,” the report summarizes.

The report, of course, did not get much coverage from the same media it was criticizing. But it is an essential document: a real-time, thorough, sober case study on flagrant liberal institutional hypocrisy.

Compare these findings with how many U.S. media workers, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, were punished for expressing solidarity with Ukrainians or explicitly criticizing Russia. An informal survey conducted by this author of a similar time frame shows that exactly zero were. One never wants to compare tragedies, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is a crime and tragedy in its own right. But given that it happened 18 months prior to Israel’s leveling of Gaza, it can serve as a useful A-B test to expose some of the racist, power-serving, and blatantly phony currents in elite liberal discourse. Expressing solidarity with Ukrainians, however sincere or morally urgent, offends essentially no center for power within the United States – – no wealthy donors, no Congressional subcommittees, no Fox News or CNN pundits — unlike expressions of solidarity with Palestinians, which has thus far cost countless people their jobs, status, reputations and financial security.

[...]

The breakneck hypocrisy is not just the purview of Western media and the highbrow literary world — it’s par for the course among elite educational institutions as well. It was announced Tuesday that Harvard University will, according to the New York Times, “no longer take positions on matters outside of the university.”

When it was Russia invading Ukraine, the university did not hesitate to express empathy and explicitly take a side. Then-President Lawrence Bacow made it clear where the institution stood: “Now is a time for all voices to be raised. The deplorable actions of Vladimir Putin put at risk the lives of millions of people and undermine the concept of sovereignty. Institutions devoted to the perpetuation of democratic ideals and to the articulation of human rights have a responsibility to condemn such wanton aggression.”

But as the carnage in Gaza became increasingly obscene and difficult to defend, moral stances became trapped in a fog of liberal equivocation and above-the-fray appeals to high-minded neutrality. The New York Times dutifully frames this pivot as a response to some organic fraughtness of the topic at hand, without commenting on the obvious power structures that make it fraught in the first place. “Perhaps unlike any other issue, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict split university communities, and clarified the downsides of such statements on highly contested topics,” the Times notes.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Olga Romanova says profit motives make Federal Penitentiary Service Russia’s most ‘anti-war’ agency

In an interview for The Insider, literary critic Nikolai Aleksnadrov spoke to Olga Romanova, the director of the civil rights organization Russia Behind Bars, about the past and present of Russia’s prisons. Romanova’s core argument is that private profits drive policy within the Federal Penitentiary Service, shaping attitudes and practices related to prisoner labor, troop recruitment, and trends in persecution and torture. The “merger” between Russia’s state authorities and the criminal world has established a transactional system that determines how prisons are administered. Romanova says this “interpenetration” ensures shared interests in how rights and privileges are extended (and denied) to inmates, particularly when it comes to forced labor and protections against abuse.

Thanks to these administrative linkages between officials and criminals, Russia’s shifting geopolitics reverberate in the prison system and trigger purges of the latest “public enemies” from inside the “crime committees” that share power at penitentiaries. Romanova says this happened to Georgian “thieves in law” after Russia’s brief war in 2008. She claims that radical Islamists seized the vacuum left by ousted Georgian criminal bosses. Romanova also argues that an ongoing campaign by prison officials against all Muslim inmates escalated further in the aftermath of the Moscow concert hall terrorist attack in March 2024.

According to Romanova, the Federal Penitentiary Service’s reliance on kickbacks and the embezzlement of profits derived from forced labor has — somewhat counterintuitively — made the agency the most anti-war in the federal government. The reason for this attitude is that the war has diluted prisons’ labor pool and diverted funding that might otherwise have maintained or even improved the industrial infrastructure at prison facilities. In other words, the recruitment of prisoners and redirected federal spending have reduced the income of corrupt prison officials (and cut earnings for all the other bureaucrats who collect their own rents in this chain).

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm of the opinion that Hideo Kojima was leading Metal Gear in increasingly tight concentric circles to the point that if he hadn't left Konami, the next Metal Gear after V would have strangled the series to death on its own insular plotting. His storytelling tendencies have only gotten increasingly esoteric and abstract as his career has worn on, his obscene loreboner is always erect, and he made no secret of his exhausted resentment of his own series over the years.

All three were very bad developments for a series whose roots are poignant post-Soviet political commentary and the real-world implications of nuclear weaponry giant death robots. Did the injection of philosophical musings on the nature of heritage and culture add a good post-modern spice to the series? Hell yes. But after the PS2, when these themes began to overtake the political commentary, you can feel the series start to lose itself. It detaches from the real world, from its own world, from its own characters, as they devolve into plot points and mouthpieces for Kojima to muse on human nature and the purpose of life, polemics ranting themselves at each other atop Mount Snakemore.

Sometimes an elderly Navajo man talks about how much he loves cheeseburgers and they're the only good colonial invention, and that's fun. I agree with that. But all the implications of his part in a story about colonization desecrating indigenous culture and atomizing native people is so buried by layers of metaphor and avant-garde storytelling and literary reference and being sidelined because Phantom Pain is really about the hollowness of chasing retribution and Cowboy Freddy Krueger being mad he had to clean up after Big Boss' dumb ass for several years (*sharp inhale*), that it ends up toothless. No point to make, because it's behind the hazy spectre of Metal Gear Solid. A grandiose video game ouroburos, a selfish, controlling, tired auteur's albatross of an opus.

Revengeance is an antidote for all this, as it reaches beyond The Saga Of Snake into a world that, while still divorced from itself, is far more grounded in the physical, the geopolitical, in exploring the logistic ramifications of all the Weird Plot Shit in MGS4, (accidentally) tapping into a very real and very dangerous sentiment that was brewing in the United States at the time that would boil over a few years later. It isn't perfect, it's far less intricate than Kojima's work, but it's such a breath of fresh air; a clear and strong sign of life in Metal Gear as a concept. It can absolutely persist beyond Kojima, provided it's allowed to leave The Dynasty behind.

I of course had the exact same thought about Star Wars in 2017, and I expect my hopes would be similarly snuffed out with regards to Metal Gear, should it move forward after Delta and the imminent rereleases. But there is a non-zero chance that the next entirely new Metal Gear will be an enthusiastic, daring work made with love, bursting with new material. If Kojima was still in charge, that would be another Return to Zero.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Title: Mobility: A Novel

Author: Lydia Kiesling

Genre: literary fiction

Content/Trigger Warning/s: discussions and mentions of major historical events and natural disasters, including but not limited to 9/11, the BP Oil Spill, Hurricane Harvey, and the COVID-19 pandemic

Summary (from author's webpage): The year is 1998, the End of History. The Soviet Union is dissolved, the Cold War is over, and Bunny Glenn is an American teenager in Azerbaijan with her Foreign Service family. Through Bunny’s eyes we watch global interests flock to the former Soviet Union during the rush for Caspian oil and pipeline access, hear rumbles of the expansion of the American security state and the buildup to the War on Terror. We follow Bunny from adolescence to middle age—from Azerbaijan to America—as the entwined idols of capitalism and ambition lead her to a career in the oil industry, and eventually back to the scene of her youth, where familiar figures reappear in an era of political and climate breakdown.

Both geopolitical exploration and domestic coming-of-age novel, Mobility is a propulsive and challenging story about class, power, politics, and desire told through the life of one woman—her social milieu, her romances, her unarticulated wants. Mobility deftly explores American forms of complicity and inertia, moving between the local and the global, the personal and the political, and using fiction’s power to illuminate the way a life is shaped by its context.

Buy Here: https://bookshop.org/p/books/mobility-lydia-kiesling/18547461

Spoiler-Free Review: Godsdamn but this book makes me FUCKING ANGRY! I mean this in a good way, by the way, as this is frankly speaking a pretty good read.

Look, it’s not every day that a book pisses me off, but this one pissed me off in the best possible way, with its focus on the sheer hypocrisy of white people - specifically privileged white women - when it comes to the much larger suffering that everyone else around them experiences. From the moment she is introduced all the way to the very end of this novel, Bunny/Elizabeth thinks of no one but herself. Her disinterest as a teenager can be forgiven, I suppose, because I think a majority of teenagers are self-centered little shits to varying degrees - and I say that as a teenager who was pretty self-centered myself. The few who aren’t are rare and far between.

But later on, as she grows more and more comfortable in her place in the oil industry, you can practically SEE her convincing herself that what she’s doing, what her industry is doing, is right and just and not as problematic as everyone thinks it is. Worse, one can also read how she twists her WILLFUL IGNORANCE into a VIRTUE because IT BENEFITS HER TO DO SO. It’s just so INFURIATING to see that happen, since she has the privilege and the opportunity to do better, and yet: SHE DOESN’T!

The funny thing is, SHE GETS CALLED OUT ON IT! There are several moments throughout the novel wherein she is forced to confront how she doesn’t take a stand on anything, for just sitting on a fence, for thinking only of her own comfort, and while she sometimes pauses to think about what the other person’s saying and wonder if maybe they’re right, you can almost FEEL her flinch away from anything that makes her uncomfortable. THEN she goes RIGHT back to thinking any line of thought that makes her feel “safe” and one gets to watch as she chooses the path that makes her feel better, even if it comes at the cost of other people’s lives. They’re not HER people after all, how can she consider the plight of some nebulous entity who lives half the world away and whom she’s never met? This takes a chillingly exploitative turn towards the end of the novel.

I’ll admit, for a few moments while reading this I wonder if there’s anything she could have realistically done to actually take a stand and do something. The size and complexity of the oil industry is mentioned repeatedly throughout the novel; at various points Bunny/Elizabeth herself says that she can’t understand all of it, no matter how hard she tries. And when one is faced with something THAT big, that has the capacity to mutate into a new form to avoid accountability and instead re-emerge stronger than ever— How does one fight against something like that? Seen from that perspective maybe Bunny/Elizabeth’s reticence can be understood, even sympathized with, but after a certain point even this sympathy evaporates because it becomes clear that she’s CHOOSING to remain complacent.

But the interesting thing is, all this rage at Bunny/Elizabeth and the life she’s chosen can easily be turned on oneself. You read this book and wind up asking yourself: “Am I actually doing anything about the way the world works? Am I doing enough?” These are important questions, in my opinion, and applies to a lot more issues than just the theme of climate crisis that this book’s built around. None of these questions are comfortable or soothing, and the potential answers are likely to be less so, but they’re questions we need to ask regardless, if we don’t want to face the same kind of future Bunny/Elizabeth faces at the end of the novel.

Overall, this is an infuriating read, but excellent precisely BECAUSE it’s infuriating. It reveals some very uncomfortable truths and make the reader as some very difficult questions, leading to answers that are probably even MORE uncomfortable and difficult than the questions themselves. But the novel also emphasizes the need to ask those questions and find those answers, because seeking only to live in a bubble of comfort, unbothered and undisturbed by the wider world’s troubles, means living a life devoid of compassion and empathy, and only leads to a future where the entire world suffers.

Rating: five oil tankers

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

tbh even the feminist commentary COULD have been good. The concept of using dolls to talk about societal norms & ideological forces could actually work incredibly well, but the movie only treats them as people in those moments. Like they're dolls when it comes to haha funny jokes but otherwise it seems to not sink in that those are ideas in plastic form and therefore not actual people who can genuinely experience oppression & deal it out in the way that we do.

Like. The patriarchy isn't "'men are better & their interests are more important & more valid", thats only a consequence of the patriarchy. The central & most stable ideological center of the patriarchy is heteronormativity, which is very much always already the central proposition of barbieland. The extremely sharp unbreakable divide between men & women, the highly sexualized yet completely sexless perfectly gendered bodies, the monogamous heterosexual relationships that are again, sexless, based not on any kind of pleasure or eroticism but on following preordained scripts & reaffirming identities. The entire simulacrum of traditional american society all the way down to a suburb & malibu beach, all completely detached from any kind of material reality. This could be a great setting for talking about ideology & sexism!!! But it fails & does the opposite and actually obscures ideology and sexism in the process.

Like. okay. moment that made me bite my hands in frustration at the sheer lack of awareness was when barbie first comes to the real world w ken, she gets catcalled by construction workers & answers "hey. i think you all should know i don't have a vagina. And he doesn't have a penis! we literally don't have genitals" and i was like please say moreeeeee think about it for just a second think about what that meannnnns. But no it was just a joke about how as kids we all thought it was weird they didn't have genitals. Ha-ha. How can you not DO anything with that in your commentary on feminism just think for just a little bit it could be so interesting. Barbie is a woman! Not a single person ever denies this but she doesn't have genitals or even a human body. Isn't it so absolutely clear when you put it like that the way that women are ideas and human bodies exist separately from those ideas?? How barbie is in some way the perfect woman specifically because she doesn't have a body?? That the body is an object upon which the idea of gender is (always uncomfortably) projected? You don't even need to say it! More focus on barbie's lack of genitals yet developing cellulite wouldve allowed those questions to emerge.

The "patriarchy" that ken brings back to barbieland after seeing the real world isn't actual patriarchy. I think thats really the most damaging part of the movie which is completely misleading the audience as to what patriarchy actually is, which is a system of political organisation supported & maintained by economic incentives. Theres no economy in barbieland. No food no shelter no people who need to be kept alive. Theres no fight for ressources, no geopolitical neighbors to contend with. All that Ken brings back is the ideological narrative of "patriarchy" which was already the one barbieland operated under. The barbies don't actually hold any positions of power, because theres nothing to have political power over. President barbie isn't president of anything, she's a barbie with a special sash that says president on it. Literary nobel prize winner barbie hasn't actually written a book. Its just what it says on her boxes. There are no factual accomplishment the titles refer to, they're ideas. The idea of a woman writing a book, the idea of a woman being president. Letting aside that women do and have done these things in the past and the patriarchy is still here alive and well, the further notion of the "idea" of a woman holding a position of power being antithetical to patriarchy is just ridiculous. Its an imaginary world in which women have all the titles and accolades traditionally awarded to men. What does that do materially for the condition of women everywhere. The barbies are all accomplished and amazing and smart (or so it says on the box) and the kens are all bland hot idiots. There are no material conditions in barbieland that led to this. The barbies are not collectively empowered to do this. They are held up as a collection of amazing individuals supposedly who reached their achievements not out of any sort of societal change but because they all happen to be individually exceptional. Where's the feminism in that? Work harder and be more amazing and you too can be president Barbie. Barbie is a women's utopia because all the individual women are exceptionally accomplished and intelligent(not in any concrete way, which is a way that still requires specific material conditions to result in any kind of concrete achievement, just essentially, ontologically exceptional and amazing), and all the individual men are mediocre and stupid. No societal change has been made. No political difference at all. This is the neoliberal dream of progressive liberation

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

15 Questions 15 Mutuals

Thank you @localfruitt for the tag :3

1. Are you named after anyone? aaa after a literary character

2. When was the last time you cried? today, talked to my dad about some Stuff u.u

3. Do you have kids? no

4. Do you use sarcasm a lot? not really, it takes me some effort to understand it and more effort to use it

5. What’s the first thing you notice about people? voice <3

6. What’s your eye color? brown, kinda dark

7. Scary movies or happy endings? scary movies :3

8. Any special talents? i have a general ease with manual stuff, drawing being what i like the most. but gay audacity + this ease means i will do anything from sewing projects to tattooing

9. Where were you born? brasília - brasil

10. What are your hobbies? reading!!! dnd!!! also games, drawing, writing, journaling more recently

11. Have you any pets? not currently ): i want a cat or two, or maybe a lizard

12. What sports do you play/have played? i used to practice muay thai/chinese boxing! also just running

13. How tall are you? 161cm

14. Favorite subject in school? geopolitics, literature, philosophy, sociology, visual arts

15. Dream job? illustrator for children's books and magazines..... aaa maybe one day

tagging: don't feel obligated but! @saturdaysky @omniscientwreck @gaydandelions @blair-the-bold @luciferousnacht @glossolali

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

2022 Year End Compilation

The Ancient Minstrel, Jim Harrison

Hm. A meandering, unfocused disappointment. In the introduction Harrison admitted that he surrendered to fictionalizing his autobiography. I wish he hadn’t. His fictitious flourishes only detract from his usually gorgeous prose.

Eggs, Jim Harrison

Hmmm! Considerably drier than I expected. It feels like he abandoned his usual poetic prose in favor of a more traditional―dare I say Russian―psychological study. The result is surprisingly staid.

The Case of the Howling Buddhas, Jim Harrison

HMMM!!! This was dreadful. Harrison has never been embarrassed by sex, but this novella feels like he wrote it with his penis.

Brida, Paulo Coelho

I have no idea if the magical system Coelho presents here is his own invention or not, but personally I don’t really care. I adored this book and its bizarre yet gentle syncretism of paganism and Christianity. I know many find Coelho’s books unbearably twee, but so far all the ones I’ve read have hit the sweet spot between sentimentality and sincerity.

Undermajordomo Minor, Patrick deWitt

At a certain point this book started to feel like deWitt wrote it solely to surprise and outguess himself. That’s the only explanation I can think of for a book that takes so many surreal and thematically nonsensical turns. I enjoyed a good deal of it, but I can’t help but wish deWitt had settled it all on a central point or two. That said, I’m not sure I’ll ever be able to forget the most bizarre secret aristocratic orgy this side of Eyes Wide Shut.

The Running Man, Stephen King [as Richard Bachman]

Deliciously, succulently furious. I had no idea King had this kind of fury in him. It made an already lean thriller absolutely propulsive. This was the pulpy palate cleanser I’ve been looking for for a long, long time.

The Far Cry, Fredric Brown

This was...very much not what I was expecting. When I picked this book up, I expected a decently entertaining crime thriller. Instead, it’s a slow-burn psychological drama of a man investigating a murder and becoming obsessed with the dead victim. So much of it predicts Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo. The first chunk of the book is a bit dry, but once the obsession begins to really take hold of the protagonist it becomes quite engaging.

Reality Check, Peter Abrahams

Apparently, this book won a Young Adult literary award when it was published. All I can say is that if books this dull were considered industry exemplars at the time, then losing an entire generation of young readers to Twilight and dystopian death games suddenly makes much more sense.

Roadwork, Stephen King [as Richard Bachman]

This book makes an interesting counterpoint with Pet Sematary: both films are, in their own ways, about dealing with grief. But whereas Sematary reacts passively with resignation, Roadwork reacts actively with rage. It’s a bit bloated, but the whole thing still vibrates with the anger that makes King’s Bachman books so compelling.

Fever 1793, Laurie Halse Anderson

A brisk and snappy work of young adult historical fiction. Would be fascinated to see what this book would’ve been if it’d been written in the shadow of our current pandemic and its plague of misinformation and anti-vaxx sentiment.

The Thing Around Your Neck, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Adichie’s short stories all, in one way or another, see people trapped between the push and pull of different identities and cultures, whether they’re racial, ethnic, or geopolitical. The opening story, the ghastly and sad “Cell One,” even extends this to see a young man incapable of adapting to the us vs. them mentality of prisoners and prisoner guards after getting arrested over suspicions of murder. It’s a fantastic collection of stories, even if all of them don’t hit equal heights. A personal favorite is “Jumping Monkey Hill.” I could’ve easily read a book-length version of that one.

Patrimony: A True Story, Philip Roth

Knowing that I’ll probably go through something similar with my own father, reading this book was like placing my hand on a hot skillet.

A Lost Lady, Willa Cather

The elegiac downfall of a man, a house, a woman, a nation, a myth. Lovely, sad, and rich with Cather’s unmistakable sense of place.

Jesus’ Son, Denis Johnson

“I had a moment’s glory that night, though. I was certain I was here in this world because I couldn’t tolerate any other place.”

The Violent Bear It Away, Flannery O’Connor

Only someone with a devout faith could write a book with such venom towards organized religion.

The Crying of Lot 49, Thomas Pynchon

Perhaps choosing this as my first novel to read while mentally burnt out after finishing a semester of seminary wasn’t the best idea.

Mao II, Don DeLillo

Terrifyingly prescient in its vision of a future where terrorism replaces the written word as the most effective means of mass communication. However, the book itself feels inherently disjointed, even within the context of DeLillo’s usual chronological and POV flourishes. Only the prologue and epilogue at the mass Moonie wedding and the revolutionary unrest in Beirut told from the perspectives of the book’s two central women seem to actually engage with DeLillo’s thesis of “the future belongs to crowds.” The middle clump of the book is mostly—both figuratively and literally—tortured writer porn.

Running Dog, Don DeLillo

Migraine-inducing in its byzantinism. This novel’s first half where it was just a pulpy spy thriller was more fun than the philosophically nihilistic second. The actual content of Hitler’s home movie was a brilliant coup, but it did little to relieve the overall turgidness of the overcomplicated narrative.

A Good Man Is Hard to Find and Other Stories, Flannery O’Connor

An essential Catholic corrective to the current of gloomy Calvinism that infects so much of American literature. The title story, “The River,” and “A Temple of the Holy Ghost” are sad and beautiful while “Good Country People” and “The Displaced Person” are deliciously nasty.

The Magic Barrel, Bernard Malamud

I enjoyed the modern Jewish parables well enough, but the “American Jew in Italy” stories sapped almost all of my enthusiasm out from reading this book.

The Pale King, David Foster Wallace

Somehow, simultaneously, one of the dullest, most thrilling, most banal, and most touching novels I’ve ever read. Wallace delves into the nature of boredom, proving that the ability to navigate mundanity and monotony is just as central to the human experience as the capacity to comprehend beauty. Parts of this novel lodged into my mind like a splinter, none more than the first chapter which might be one of the single most gorgeous pieces of prose in American literature.

A Really Big Lunch: Meditations on Food and Life from the Roving Gourmand, Jim Harrison

Possibly the finest book I’ve ever read about food, eating, the love of both, and how they all inform the act of living as a bodily human being. You can taste the marrow in this book’s bones.

The Book of Daniel, E. L. Doctorow

The fact that Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were later proven guilty as sin by declassified Soviet documents does nothing to lessen this book as a chilling portrait of how America scapegoats and lynches its poor, dispossessed, and racially marginalized. Also, I could read Doctorow’s descriptions of NYC crowds, streets, neighborhoods, and markets forever.

Homer & Langley, E. L. Doctorow

Oh, how I wish Doctorow had stretched his imaginary history of the Collyer brothers to include 9/11. Also, I feel like Doctorow might have fumbled a possible creative flourish by not revealing that the book itself was a copy of Langley’s fabled newspaper which, upon completion, managed to speculate on the future.

World’s Fair, E. L. Doctorow

Pleasant enough as a childhood autobiography of growing up in early twentieth century New York City, but at times it felt more like Doctorow was writing a laundry list of sense memories than he was the story of his youth. Also, it’s kind of cringy how much of it was recycled from The Book of Daniel.

The Ponder Heart, Eudora Welty

The rare Southern Gothic comedy that’s genuinely clutch-your-side funny, not the sardonic, wince-through-the-tragedy “comedy” of Flannery O’Connor.

Delta Wedding, Eudora Welty

**heavy sigh** You know what this book reminds me of? Those awful late 70s Robert Altman films where he filled his casts with too many damn characters all with barely anything to do.

As I Lay Dying, William Faulkner

As amazing as everyone says it is. I was a Faulkner agnostic after reading The Sound and the Fury which I admired only on a technical level and Light in August which I didn’t like at all. But this novel was a tour de force portrait of Southern decrepitude writ large with the imagery of the Old Testament and the tragedy of the ancient Greeks.

Mexican Gothic, Silvia Moreno-Garcia

Delightfully morbid, thrilling, and disgusting. Was not expecting this book to go in the direction of weird science, but I’m glad it did.

Midnight’s Children, Salman Rushdie

It was around the halfway point of this book—right when Saleem and Shiva were about to meet for the first time—that I heard the news that Salman Rushdie had been attacked and stabbed in New York. What a testament for how little has truly changed since his literary career started.

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, James Joyce

Statler: “What was this book called again? A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man?”

Waldorf: “More like Portrait of the Reader as Bored Senseless!”

Both: “D’oh-ho-ho-ho!!”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hemingway and WW II

By Nassim Belhadj

On September 1st 1939, Adolf Hitler invaded Poland with his army. Outbreak of World War II. During this period, the world-famous writer and journalist Ernest Hemingway was in his 40's. In this article we will present you the life of Ernest Hemingway during the war.

Credits : GoogleImage.com

The beginning of a world conflict

From the beginning of the Second World War until July 1944, Hemingway spent his time in his Cuban villa in Havana: he fished and spent his days on his yacht. He also follows sports and literary news. However, he does not inform himself at all of the geopolitical news of the moment. This does not prevent him from continuing to be active and from continuing to publish books. The first one came out in 1940 entitled “For whom the bell tolls”, which earned him his 7th Nobel

Prize for Literature. The first came out in 1940 entitled “For whom the bell tolls”, which earned him his 7th Nobel Prize for Literature. This book is inspired by his experience during the Spanish Civil War, a conflict during which he will be sent as a journalist-reporter. His second book is called "Men at war", which tells the story of the United States' entry into the war.

Credits : GoogleImage.com

July 1944

In June 1944, he participated as a soldier in the Normandy landings. At the end of July 1944, he was assigned to the 22nd Infantry Regiment commanded by Colonel Charles Buck Lanaham, which was heading for Paris. On August 25, he was present during the liberation of Paris. He went to Luxembourg to cover the Battle of the Ardennes on December 1917, however due to his state of health, he was hospitalized due to a pneumonia. A week later, he was discharged from the hospital but the fighting was over. In January 1945, he put an end to his participation in combat as a soldier but also as a journalist-reporter.

Credits : GoogleImage.com

To conclude, we can say that Hemigway's participation in the conflict was a bit late. Nevertheless, he participated in important moments of the conflict, such as the landing in Normandy and the liberation of Paris.

3 notes

·

View notes