#louis slotin

Text

your boyfriend—yeah, the one with the cowboy boots? yeah we um. we broke his screwdriver and he received a lethal radiation dose. yeah, in an accident that mirrored the death of his research partner months prior. so um. sorry

#mal.txt#demon core#louis slotin#boyfriend meme#talking to egg and started thinking about this HFKDJDK#radiation

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wow - the story of Louis Slotin is pretty parallel to Gale's. This must have been inspiration for the character. How thrilled Gale is with flirting with danger and showing how much he can push the limits of human capability and ingenuity.

A sense of recklessness but heroics once the error had been made. Honestly a great modern AU if anyone wants to yoink this idea. Probably will help me figure out how my scientist Tav will perceive him.

Here's a link about the situation with some visuals.

This last link in particular sheds a softer light on the guy, which parallels extremely well to Gale's dilemma about the orb and wanting to spare people from further collateral.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Version 2 of Demon Core Chan

#demon core#louis slotin#slotin’s screwdriver#my art#artist on tumblr#xray#see through#bones#nuclear energy#nuclear physics#demon core-chan#anime girl#anime#skeleton#spooky scary skeleton

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

The two absolute KINGS of "hey check this shit out" before something horrific happens

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

a cautionary tale in emoji

🖐💤🐉💣

👨🔬☢️🧱🔵🏥💀

🤠👖👢☢️🪛🔵😔🏥💀

🖐🚫☢️

🤖🦾✅️☢️🦺⛑️

#demon core#louis slotin#harry daghlian#the manhattan project#nuclear physics#death#tw death#come with me and you’ll be in a world of NRC violations#the thing is the nuclear regulatory commission didn’t exist yet#louis slotin yeed his last haw

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Holy SHIT!

New Mister Manticore video dropped!

youtube

I have no idea what this is yet but it looks intriguing!

Well it’s certainly interesting.

#personal stuff#dougie rambles#analog horror#mister manticore#louis slotin#manhattan project#Youtube#bullshit#criticality

2 notes

·

View notes

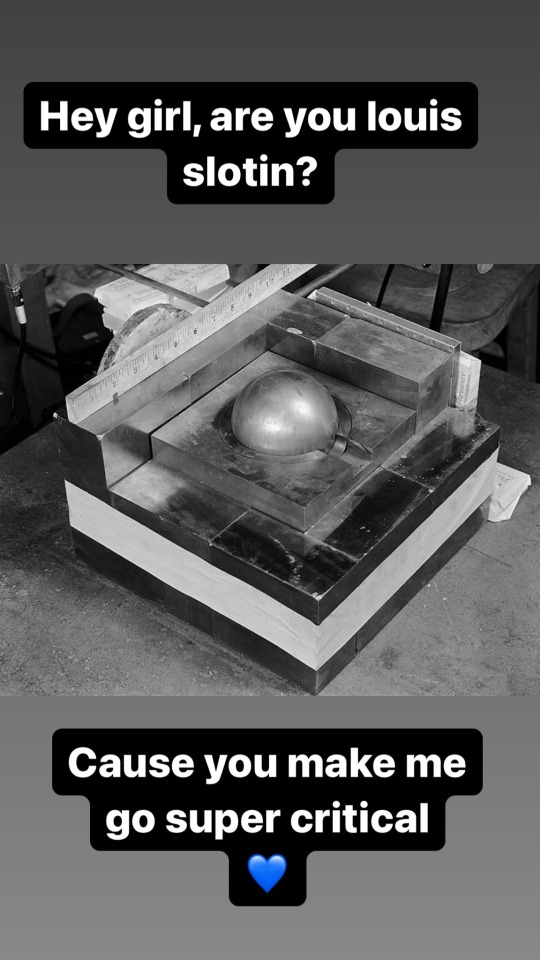

Text

#the demon core#demon core#louis slotin#radioactive#plutonium#science#science memes#shitpost#valentines day card#I laughed my ass off making it so I hope yall like it#hey girl

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

On 21 May 1946, not quite a year later, Slotin was carrying out an experiment, similar to those he had so often successfully performed in the past.

"Brighter than a Thousand Suns: A Personal History of the Atomic Scientists" - Robert Jungk, translated by James Cleugh

#book quote#brighter than a thousand suns#robert jungk#james cleugh#nonfiction#may 21#40s#1940s#louis slotin#scenes that precede unfortunate events#experiment

1 note

·

View note

Text

A poem by Michael Lista

Louis Slotin's Sex Appeal

When our bespectacled physicist

bicycles the base, despondent past

the pandaemonic faces of his peers

with their baby-eating smiles

and black fedoras shading

their blackened brains

happily he thinks of his atomic bomb,

his happy Trojan horse,

his lips now breaking

into the famous grin

that still dispatches women by the bed-load

into bedlam, into bed.

after Irving Layton

Michael Lista

Image: Close-Up of Nuclear Scientist Louis Slotin, next to the Trinity bomb, 1945.

The complete text of Bloom, a poetic account of the last day of Louis Slotin's life, is available on the Internet Archive.

0 notes

Text

'My parents’ house sits at the foot of the Sangre de Cristos facing west toward the setting sun and the Jemez Mountains. I still remember nights looking out across the vast darkness at the twinkling lights of Los Alamos, the secret city, “a place,” as the late anti-nuclear activist and Ohkay Owingeh elder Herman Agoyo put it, “with no public memory.”

As the crow flies, Truchas is 30 miles from Los Alamos, separated by the great Tewa Basin and arid badlands checkerboarded by Hispano settlements and Indigenous Pueblos. For most of my young life, I took the Lab for granted. It was there in the background, omnipresent like a low-frequency hum.

Memorandum for the record

But it didn’t always just exist. It was forced onto our homeland and into our consciousness, even if most origin stories about the Manhattan Project and the Lab’s continued presence in the region treat local people like extras in a movie.

“For the several hundred workers required to man these plants, there must also be several thousand service and supporting personnel,” a 1950 internal report read. Its writer was debating whether Los Alamos was the best place for the weapons Lab moving forward.

Scientists performed clandestine work here, yes, but that work required and continues to require the effort of so many others — “supporting personnel” — who can also be on the frontlines of exposure.

I am reminded, for instance, of an experiment that went horribly wrong just nine months after American forces decimated Hiroshima and Nagasaki with nuclear bombs. A Canadian physicist, Louis Slotin, was trying to gather data on nuclear chain reactions when the screwdriver he was holding as a wedge between a beryllium tamper and a plutonium core accidentally slipped. For a brief second, the beryllium and plutonium reached fission, sending out a blast of blue light and radioactivity.

Slotin’s death in 1946 has been famously recorded in histories of the Lab. But there were several other people in the room that day, including several colleagues and a security guard whose fate has largely been eclipsed. All that was noted in records of the event was his fear. Apparently, it was said, the security guard ran out of the room and up a hill. And that’s where his part in the story ends.

But he was there, a witness — and one, I imagine, who was exposed to the same plutonium that within a matter of nine days killed Slotin. I’ve long wondered: Who was he? What was his story?

When I think of that man, I think of my Grandpa Gilbert. Many auxiliary staff were local people who got their start on “the hill” as security guards for the Atomic Energy Commission. That was his story — a career begun as a security guard in 1946 and ended some three decades later as a staff member of the Lab and the University of California, which managed it. The position was a distinction that not many Hispanos held at the time. My mom says he felt dignified by his work there — the only means he had to raise five kids after World War II. But there was a trade-off, including discreet trips to the doctor where he was screened for cancer on a more-than-routine basis.

Many family members would follow in his footsteps — my Uncle Jerry among them. Los Alamos was a place abounding in conspiracy theories and Uncle Jerry found himself at the center of one of them. He believed that racism had created a culture of retaliation, so toxic that it led to his being framed for intentionally dosing his supervisor with plutonium-239. After my uncle’s death two years ago, the Santa Fe New Mexican published a column narrating the sordid events — his boss ultimately recanted the allegations and my uncle and others won a settlement — but he was haunted by a lasting specter. The multiple cancers that consumed his body decades later were products of the Lab, in his opinion, like sleeper fires set within him.

I only recently came to know the fragments of my Uncle Pat’s story. During his three years at the Lab in the late 1970s, he was flown on two occasions to California with a locked box chained to his wrist. His destination was TRW, the predecessor of Northrop Grumman Space Technology, and his cargo, he told me, was top-secret technology that could detect nuclear weapons testing from outer space.

There’s a kind of mental acrobatics required to compartmentalize these different realities — the opportunity and the harm, the secrets and the consent. I know this compartmentalization well, this desire to draw a line in the sand between the good and the bad. When I was 19, I spent a summer working as an undergraduate intern in the Lab’s explosives division, a building perched behind a maze of fences and guards. I didn’t have a security clearance at the time, nor could I foresee getting one, so I spent most days marooned at my desk in the front office, filing papers and sending emails. I couldn’t even take a bathroom break without a chaperone accompanying me.

Nothing of that work rings more clearly than a memory of two scientists stumbling out into the hallway, covered in blood. An experiment had gone awry — nothing radiation related — but it was so shrouded in mystery that parsing what actually happened is like trying to put a puzzle together that’s missing half the pieces. I watched in horror from the doorframe.

After that, I transferred to the Bradbury Science Museum, also in Los Alamos, where I walked by replicas of Little Boy and Fat Man daily to get to my desk. I spent that summer, among other things, writing exhibition text about the Manhattan Project’s early architects — J. Robert Oppenheimer, Enrico Fermi, Richard Feynman. I wrote not the history of mi gente, but of those agents of immense creation and destruction, those who’d exacted what Myrriah Gómez in her book, “Nuclear Nuevo México,” calls nuclear colonization. The irony.

It was only when I left the state that I had the distance to understand the debt our communities pay for the good jobs. I began to unpack what it means for New Mexico to be what the writer D.H. Lawrence once called the moon of America. This place was distant enough in America’s consciousness to be foreign, exotic even. But as that “tierra incognita,” the unknown and unknowable blankness stretched across mental maps of the Southwest, our world became America’s wasteland. We continue to sit at the periphery of centers of power, yet we have been forced into the epicenter of this nation’s nuclear weapons complex.

Now, as I write about the role of nuclear weapons across New Mexico, the nation and the globe, Toni Morrison’s words come to mind: “The subject of the dream is the dreamer.” Her ideas about literature were deeply influenced by psychoanalysis. Indeed, to her mind, the act of dreaming was not unlike the act of writing. Or, to put it another way, the subject of the writing is the writer. Here, that is me.

My family and community’s own tangled history with the Lab sits in my subconscious like an inchoate thought. Only when I hold it up to scrutiny does that thought form into the imperative, allowing me to fully fathom what the Manhattan Project birthed in our backyard. Perhaps this is what Gómez refers to as an “innate knowing,” our local “sixth sense.”

“The locals know their local land and water supplies are contaminated from the nuclear material that was either buried in nearby canyons or on riverbanks,” Gómez writes in her book. “They know their presence on the Pajarito Plateau is being erased from national memory. They know they were placed in dangerous jobs because of their identities. They know the plutonium exploded into the atmosphere during the Trinity Test is making them sick. They know nuclear waste, if buried in their backyard, poses severe threats.”

I know all of this when I drive along Highway 84/285, an artery that connects Pojoaque Pueblo to Española and the Pueblos of Santa Clara and Ohkay Owingeh, below a billboard sprawled against sienna-hued bluffs. A woman with a complexion like my own holds radiation detection equipment and smiles down at me.

“Radiation Control Technicians are vital to operations at LANL,” the billboard proclaims. “Start your career as an RCT at Northern NM College now.”

My worldview will always shape my writing on a topic that hits so close to home, but the focus of this series — The Atomic Hereafter — is to highlight all the communities most impacted by 80 years of nuclear presence, from the most recent attempts to modernize the nation’s nuclear arsenal to the long, drawn-out ways radiation can transmit from mother to child. Nuclear issues in this state are generational. I will take them one story at a time.'

0 notes

Text

i feel like the way i talk about real life catastrophic things happening to people vs. the way some ppl talk about it is like radically different

#considering a lot of it is “me wanting to at least be a modicum respectful”#like louis slotin's death for example#but a lot of ppl just want to joke and make light of people dying in horrific ways (real life ppl i should add)#and it feels really . idk. disrespectful and uncomfortable#like its not a heehee hoo hoo funny its a “this person slowly died in a horrifying fashion and its not funny”

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

He should not be chillin with his bestie Louis Slotin at the Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico on May 21, 1946

It took me a second to realize what you were talking about, and the instant i realized i just went "OH NO NOT THE DEMON CORE!"

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

While I'm on the subject of talking about the Manhattan Project, I want to say that Louis Slotin probably has one of the funniest legacies of anyone in history. "He bravely saved the lives of several of his coworkers... from himself, for being a stupid fucking idiot who died because he was a stupid fucking idiot."

116 notes

·

View notes

Text

me: I thought of the WORST dating sim / visual novel idea

by WORST I mean I am grinning manically as I type this

(but also. it's a bad idea. I want to make it very clear I know that)

YOU are a brilliant female physicist who has Mulan'ed her way into the Manhattan Project

YOUR OPTIONS ARE: von neumann, feynman, oppenheimer, etc etc

...I have to google whether this has been done. hmm. mildly surprisingly, no!

@eightyonekilograms: Louis Slotin if you like himbos

@femmenietzsche: You should also be able to romance the Demon Core

315 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nuclear Accidents to read about for more Burrow’s End Context (Besides Chernobyl):

I’ve recently become hyperfixated with reading about these and a lot of them have bits that I think can add to what’s going on in Burrow’s End. (These are far from all the possible examples I could give you, these just seemed the most relevant). I’ve grouped them by location in honor of the Cold War themes we’ve been seeing.

Soviet Incidents:

Mayak Kyshtym Disaster (1957) | Considered the third worst nuclear plant disaster in history (behind Chernobyl and Fukushima). Case of neglect and lack of oversight and general human stupidity. Caused huge amount of contamination to surrounding area; they had previously already been dumping their waste into a nearby lake. High civilian casualties; at least 200 people died and many, many more were affected.

“In the 45 years afterwards, about half a million people in the region have been irradiated in one or more of the incidents, exposing them to up to 20 times the radiation suffered by the Chernobyl disaster victims outside of the plant itself.”

Vinča Nuclear Institute Criticality Excursion (1958) | Researchers smelled ozone while they were unknowingly being irradiated, resulting in one death

Greifswald Nuclear Power Plant Incidents | 1975: Electrical fire destroyed control lines to coolant pumps 1989: Another cooling pump malfunction caused near-meltdown

KS-150 Incidents (1976, 1977) | Several different incidents involving coolant malfunction

K-431 Chazhma Bay Accident (1985) | Criticality excursion on a nuclear submarine caused by operator error. Resulted in a large area of severe contamination. (10 fatalities, another 49 injured, unknown how many could have been affected by contamination).

US Incidents:

Louis Slotin Accident (1946) | There are several excursions and deaths associated with the Manhattan Project and Los Alamos— but this one involved witnesses reporting a “blue glow” as the resulting radiation ionized the surrounding air. Slotin died within days, and several of his colleagues were injured, one permanently disabled, with some later dying early deaths.

Cecil Kelley Accident (1958) | Procedural error caused criticality accident that resulted in a “bright flash of blue light;” (warning that the descriptions on this one get particularly grisly as Kelley received more than seven times the adult lethal dose of radiation; he was the only one affected).

Surry Power Station Incidents (1972, 1979, 1986, 2011) | Multiple cooling system accidents, primarily those involving escaping steam, resulting in burns and one explosion. (Only the events in 1972 and 1986 resulted in loss of life, for 6 deaths total)

Three Mile Island Accident (1979) | Water escaped from the coolant system due to a mix of operator error and design flaws. This led to the reactor overheating and an eventual leak of radioactive gases via the steam released during the incident. Luckily the contamination of surrounding areas appears to have been minimal (for the most part).

Pilgrim Nuclear Power Station Malfunctions (1986) | Used Cape Cod Bay as the water source for its cooling system, resulting in an impact on aquatic plant and animal life. In 1986, recurring equipment malfunctions resulted in an emergency shutdown. The US Nuclear Regulatory Commission once referred to it as “one of the worst-run″ nuclear power plants in the US.

Peach Bottom Atomic Power Station Incidents (1987) | Nuclear Regulatory Commission found evidence of misconduct, procedure error, corporate malfeasance, deliberate disregard for safety regulations, and pollution via accidental waste leakage into a nearby river. Resulted in a forced shutdown in 1987, associated with cooling malfunctions.

(There are several other [mostly nonfatal] US incidents at nuclear power plants, too many to fully get into here. See: Idaho National Laboratory, Enrico Fermi Nuclear Generating Station, Browns Ferry Nuclear Plant, Nine Mile Point Nuclear Station, Calvert Cliffs Nuclear Power Plant, Millstone Nuclear Power Station, Crystal River Nuclear Plant, and Davis–Besse Nuclear Power Station)

Other Locations:

Lucens Reactor Accident (1969) | Loss of coolant accident led to partial meltdown and contamination of the reactor cavern

Vandellòs Nuclear Power Plant Accident (1989) | A fire damaged the cooling system, leading to near-meltdown

Other Resources:

Wikipedia:

Page for nuclear and radiation accidents

Page for criticality accidents

Page for LOCA (Loss-of-coolant accident)

Union of Concerned Scientists:

A Brief History of Nuclear Accidents Worldwide

National Health Institute:

Civilian nuclear incidents: An overview of historical, medical, and scientific aspects

See Also:

World Nuclear Association, Atomic Archive, Institute for Energy and Environmental Research, The Nuclear Regulatory Commission, and the International Atomic Energy Agency.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

15 Inventors Who Were Killed By Their Own Inventions

Marie Curie - Marie Curie, popularly known as Madame Curie, invented the process to isolate radium after co-discovering the radioactive elements radium and polonium. She died of aplastic anemia as a result of prolonged exposure to ionizing radiation emanating from her research materials. The dangers of radiation were not well understood at the time.

William Nelson - a General Electric employee, invented a new way to motorize bicycles. He then fell off his prototype bike during a test run and died.

William Bullock - he invented the web rotary printing press. Several years after its invention, his foot was crushed during the installation of the new machine in Philadelphia. The crushed foot developed gangrene and Bullock died during the amputation.

Horace Lawson Hunley - he was a marine engineer and was the inventor of the first war submarine. During a routine test, Hunley, along with a 7-member crew, sunk to death in a previously damaged submarine H. L. Hunley (named after Hunley’s death) on October 15, 1963.

Francis Edgar Stanley - Francis crashed into a woodpile while driving a Stanley Steamer. It was a steam engine-based car developed by Stanley Motor Carriage Company, founded by Francis E. Stanley and his twin Freelan O. Stanley.

Thomas Andrews - he was an Irish businessman and shipbuilder. As the naval architect in charge of the plans for the ocean liner RMS Titanic, he was travelling on board that vessel during her maiden voyage when the ship hit an iceberg on 14 April 1912. He perished along with more than 1,500 others. His body was never recovered.

Thomas Midgley Jr. - he was an American engineer and chemist who contracted polio at age 51, leaving him severely disabled. He devised an elaborate system of ropes and pulleys to help others lift him from the bed. He was accidentally entangled in the ropes of the device and died of strangulation at the age of 55.

Alexander Bogdanov - he was a Russian physician and philosopher who was one of the first people to experiment with blood transfusion. He died when he used the blood of malaria and TB victim on himself.

Michael Dacre - died after testing his flying taxi device designed to permit fast, affordable travel between regional cities.

Max Valier - invented liquid-fuelled rocket engines as a member of the 1920s German rocket society. On May 17, 1930, an alcohol-fuelled engine exploded on his test bench in Berlin that killed him instantly.

Mike Hughes - was killed when the parachute failed to deploy during a crash landing while piloting his homemade steam-powered rocket.

Harry K. Daghlian Jr. and Louis Slotin - The two physicists were running experiments on plutonium for The Manhattan Project, and both died due to lethal doses of radiation a year apart (1945 and 1946, respectively).

Karel Soucek - The professional stuntman developed a shock-absorbent barrel in which he would go over the Niagara Falls. He did so successfully, but when performing a similar stunt in the Astrodome, the barrel was released too early and Soucek plummeted 180 feet, hitting the rim of the water tank designed to cushion the blow.

Hammad al-Jawhari - he was a prominent scholar in early 11th century Iraq and he was also sort of an inventor, who was particularly obsessed with flight. He strapped on a pair of wooden wings with feathers stuck on them and tried to impress the local Imam. He jumped off from the roof of a mosque and consequently died.

Jean-Francoise Pilatre de Rozier - Rozier was a French teacher who taught chemistry and physics. He was also a pioneer of aviation, having made the first manned free balloon flight in 1783. He died when his balloon crashed near Wimereux in the Pas-de-Calais during an attempt to fly across the English Channel. Pilâtre de Rozier was the first known fatalities in an air crash when his Roziere balloon crashed on June 15, 1785.

50 notes

·

View notes