#morrison

Text

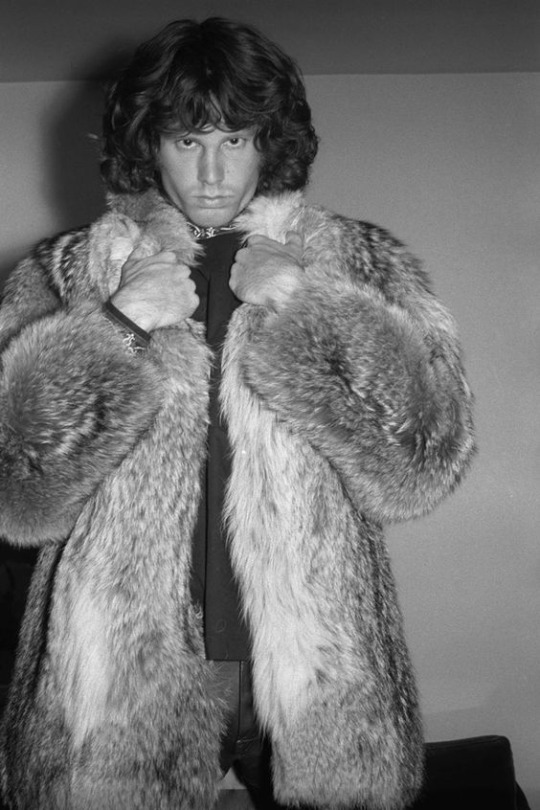

Jim Morrison, that’s it. that's the post

#jim morrison#the doors#60s rock#60s music#psychedelic rock#60s#70s#70s music#60s fashion#60s icons#1960s#sixties#1970#seventies#rock#shaman#morrison#the doors band#music#artist#artists

610 notes

·

View notes

Text

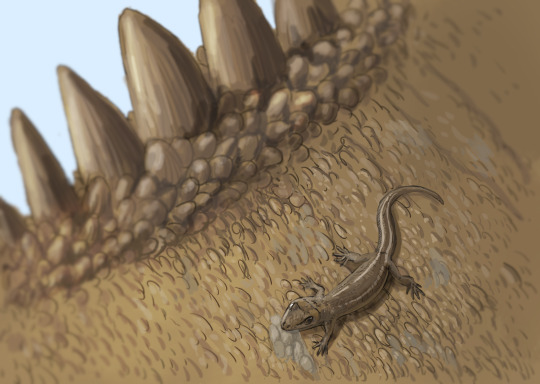

Results from the #paleostream (first of the "classic edition"). I just now notice that 3 of these are in the process of eating something. Helioscopos, Pelodosotis, Plourdosteus, Leptauchenia

#sciart#paleoart#paleostream#palaeoblr#dinosaur#jurassic#morrison#gecko#placoderm#oreodont#leptospondyl

349 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stegosaurus stenops

#paleoillustration#paleontologist#paleo art#paleoblr#paleoart#paleontology#paleostream#paleomedia#jurassic period#Morrison#morrison formation#stegosaurus#dinosaurs#dinosaur#dinosaur art#sketchbook

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

They were solitary little girls whose loneliness was so profound it intoxicated them and sent them stumbling into Technicolored visions that always included a presence, a someone, who, quite like the dreamer, shared the delight of the dream.

- Toni Morrison, Sula

#quotes#books#literature#lit#classics#academia#light academia#dark academia#chaotic academia#book#book quotes#quotation#Toni Morrison#Morrison#Sula#Novel#Fiction#Historical Fiction

133 notes

·

View notes

Text

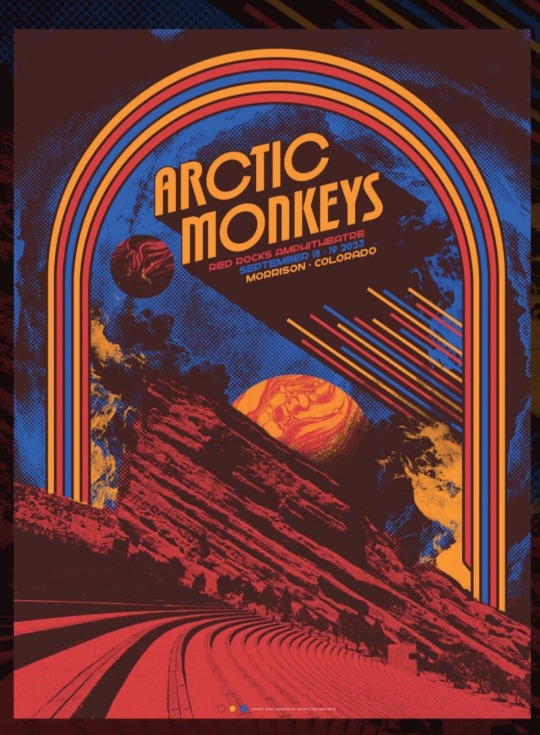

Alex Turner backstage at Red Rocks Amphitheater, Morrison Colorado

18/09/2023

🎥: lairy_girl

#arctic monkeys#alex turner#the car era#the car tour#the car#red rocks amphitheatre#morrison#colorado#video fan

157 notes

·

View notes

Text

““Dorothy reminds me in so many ways of Toni Morrison,” West said. “You know Toni Morrison is Catholic. Many people do not realize that she is one of the great Catholic writers. Like Flannery O’Connor, she has an incarnational conception of human existence. We Protestants are too individualistic. I think we need to learn from Catholics who are always centered on community.”

(…)

She viewed belief in God as “an intellectual experience that intensifies our perceptions and distances us from an egocentric and predatory life, from ignorance and from the limits of personal satisfactions”—and affirmed her Catholic identity. “I had a moment of crisis on the occasion of Vatican II,” she said. “At the time I had the impression that it was a superficial change, and I suffered greatly from the abolition of Latin, which I saw as the unifying and universal language of the Church.”

Morrison saw a problematic absence of authentic religion in modern art: “It’s not serious—it’s supermarket religion, a spiritual Disneyland of false fear and pleasure.” She lamented that religion is often parodied or simplified, as in “those pretentious bad films in which angels appear as dei ex machina, or of figurative artists who use religious iconography with the sole purpose of creating a scandal.” She admired the work of James Joyce, especially his earlier works, and had a particular affinity for Flannery O’Connor, “a great artist who hasn’t received the attention she deserves.”

What emerges from Morrison’s public discussions of faith is paradoxical Catholicism. Her conception of God is malleable, progressive, and esoteric. She retained a distinct nostalgia for Catholic ritual, and feels the “greatest respect” for those who practice the faith, even if she herself wavered. In a 2015 interview with NPR, Morrison said there was not a “structured” sense of religion in her life at the moment, but “I might be easily seduced to go back to church because I like the controversy as well as the beauty of this particular Pope Francis. He’s very interesting to me.”

Morrison’s Catholic faith—individual and communal, traditional and idiosyncratic—offers a theological structure for her worldview. Her Catholicism illuminates her fiction; in particular, her views of bodies, and the narrative power of stories. An artist, Morrison affirmed, “bears witness.” Her father’s ghost stories, her mother’s spiritual musicality, and her own youthful sense of attraction to Christianity’s “scriptures and its vagueness” led her to conclude it is “a theatrical religion. It says something particularly interesting to black people, and I think it’s part of why they were so available to it. It was the love things that were psychically very important. Nobody could have endured that life in constant rage.” Morrison said it is a sense of “transcending love” that makes “the New Testament . . . so pertinent to black literature—the lamb, the victim, the vulnerable one who does die but nevertheless lives.”

(…)

Morrison is describing a Catholic style of storytelling here, reflected in the various emotional notes of Mass. The religion calls for extremes: solemnity, joy, silence, and exhortation. Such a literary approach is audacious, confident, and necessary, considering Morrison’s broader goals. She rejected the term experimental, clarifying “I am simply trying to recreate something out of an old art form in my books—the something that defines what makes a book ‘black.’”

(…)

Morrison was both storyteller and archivist. Her commitment to history and tradition itself feels Catholic in orientation. She sought to “merge vernacular with the lyric, with the standard, and with the biblical, because it was part of the linguistic heritage of my family, moving up and down the scale, across it, in between it.” When a serious subject came up in family conversation, “it was highly sermonic, highly formalized, biblical in a sense, and easily so. They could move easily into the language of the King James Bible and then back to standard English, and then segue into language that we would call street.”

Language was play and performance; the pivots and turns were “an enhancement for me, not a restriction,” and showed her that “there was an enormous power” in such shifts. Morrison’s attention toward language is inherently religious; by talking about the change from Latin to English Mass as a regrettable shift, she invokes the sense that faith is both content and language; both story and medium.

From her first novel on forward, Morrison appeared intent on forcing us to look at embodied black pain with the full power of language. As a Catholic writer, she wanted us to see the body on the cross; to see its blood, its cuts, its sweat. That corporal sense defines her novel Beloved (1988), perhaps Morrison’s most ambitious, stirring work. “Black people never annihilate evil,” Morrison has said. “They don’t run it out of their neighborhoods, chop it up, or burn it up. They don’t have witch hangings. They accept it. It’s almost like a fourth dimension in their lives.”

(…)

Morrison has said that all of her writing is “about love or its absence.” There must always be one or the other—her characters do not live without ebullience or suffering. “Black women,” Morrison explained, “have held, have been given, you know, the cross. They don’t walk near it. They’re often on it. And they’ve borne that, I think, extremely well.” No character in Morrison’s canon lives the cross as much as Sethe, who even “got a tree on my back” from whipping. Scarred inside and out, she is the living embodiment of bearing witness.

(…)

Morrison’s Catholicism was one of the Passion: of scarred bodies, public execution, and private penance. When Morrison thought of “the infiniteness of time, I get lost in a mixture of dismay and excitement. I sense the order and harmony that suggest an intelligence, and I discover, with a slight shiver, that my own language becomes evangelical.” The more Morrison contemplates the grandness and complexity of life, the more her writing reverts to the Catholic storytelling methods that enthralled her as a child and cultivated her faith. This creates a powerful juxtaposition: a skilled novelist compelled to both abstraction and physicality in her stories. Catholicism, for Morrison, offers a language to connect these differences.

For Morrison, the traits of black language include the “rhythm of a familiar, hand-me-down dignity [that] is pulled along by an accretion of detail displayed in a meandering unremarkableness.” Syntax that is “highly aural” and “parabolic.” The language of Latin Mass—its grandeur, silences, communal participation, coupled with the congregation’s performative resurrection of an ancient tongue—offers a foundation for Morrison’s meticulous appreciation of language.

Her representations of faith—believers, doubters, preachers, heretics, and miracles—are powerful because of her evocative language, and also because she presents them without irony. She took religion seriously. She tended to be self-effacing when describing her own belief, and it feels like an action of humility. In a 2014 interview, she affirmed “I am a Catholic” while explaining her willingness to write with a certain, frank moral clarity in her fiction. Morrison was not being contradictory; she was speaking with nuance. She might have been lapsed in practice, but she was culturally—and therefore socially, morally—Catholic.

The same aesthetics that originally attracted Morrison to Catholicism are revealed in her fiction, despite her wavering of institutional adherence. Her radical approach to the body also makes her the greatest American Catholic writer about race. That one of the finest, most heralded American writers is Catholic—and yet not spoken about as such—demonstrates why the status of lapsed Catholic writers is so essential to understanding American fiction.

A faith charged with sensory detail, performance, and story, Catholicism seeps into these writers’ lives—making it impossible to gauge their moral senses without appreciating how they refract their Catholic pasts. The fiction of lapsed Catholic writers suggests a longing for spiritual meaning and a continued fascination with the language and feeling of faith, absent God or not: a profound struggle that illuminates their stories, and that speaks to their readers.”

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

⭐

Art by : thehollyfox

37 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Miragaia longicollum

Commission for Primal Creations https://twitter.com/Primal_Creation

Miragaia longicollum skeletal referenced from Ashley Patch(Plastospleen) https://www.artstation.com/ashleypatch

#Digital 2D#Animals & Wildlife#Illustration#creatures#stegosaurus#herbivore#jurassic#jurassic park#jurassic world#morrison#jurassic period#lourinhã#Portugal#allosaurus#apatosaurus#Miragaia#longicollum#dinosaur#ornithischian#animals#paleoart#paleontology#scientific illustration#tyrannosaurus rex#triceratops#saurian#the isle#path of titans#beasts of the mesozoic#prehistoric planet

349 notes

·

View notes

Text

i've wanted to draw morrison for a while now i think he looks cool :)

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maple Avenue, Morrison, Illinois.

70 notes

·

View notes

Photo

We love our superheroes because they refuse to give up on us. We can analyse them out of existence, kill them, ban them, mock them, and still they return, patiently reminding us of who we are and what we wish we could be.

- Grant Morrison, Supergods: What Masked Vigilantes, Miraculous Mutants, and a Sun God from Smallville Can Teach Us About Being Human

Morrison’s book is an excellent read for all comic book fans. Morrison has been one of the most influential comic book writers of modern times. He’s worked on many iconic superheroes in his time. His writings are philosophical, humane, and slyly counter-cultural.

#morrison#grant morrison#quote#writer#comic books#superheroes#superman#christopher reeve#art#artist#genre#literature#arts#culture

205 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lorenzo Zurzolo in Morrison (2021)

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thank you for choosing J.D. Morrison & Associates!

Here at JDM&A, we specialize in solving problems, whatever that may be. We tackle anything from odd jobs to demons! We proudly serve the Redgrave City area and all its outlying towns!

If you have a request, please leave it in the ask box. We will get back to you as soon as possible.

Thank you for choosing J.D. Morrison & Associates.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

mindless drawing, thus: morrison with a sheer shirt.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Morrison

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Poster for the concert at Red Rocks Amphitheater, Morrison Colorado

18/09/2023

#arctic monkeys#the car era#the car tour#the car#red rocks amphitheatre#morrison#colorado#poster concert

237 notes

·

View notes