#nawal nasrallah

Text

Bustāniyya & Mis̲h̲mis̲h̲iyya

There was a practice day run by Master Agnes Boncuer in the Scout Hall in Clara the weekend just gone, courtesy of the good offices of THL Órlaith Caomhánach, and I took the opportunity to try out a couple of recipes on people. Both of these I've actually cooked before, but it was mostly before I was taking good notes. The two are from the same page of Annals of the Caliphs' Kitchens, the translation of al-Warraq by Nawal Nasrallah. They are bustāniyya, a dish with orchard produce, and mis̲h̲mis̲h̲iyya, an apricot stew. Both call for chicken rather than "meat", which makes them somewhat unusual.

It's worth noting that in both cases, where the recipe calls for the juice of the fruit, I used fruit and all. This is the "peasant" version of the dishes, at least in my head; while I can see the elite of the elite using just the juices and presenting meat "alone" as the dish, I can't see most cooks of the time leaving out the fruit. So in it went. I will at some point try the posh as-written version.

Here are the two recipes:

Bustāniyya (cooked with orchard produce) from the copy of Abū Samīn

Wash small and sour plums and put them in a wet kerchief [to hydrate them] if using the dried variety. If fresh ones are used, [just] add to them some water, press and mash them then strain the liquid. Cut chicken breasts into finger-like strips and add to them whatever you wish of other meats. [Put them in a pot], add the [strained juice of] cherries, and let them boil together. Season the pot with black pepper, mā kāmak̲h̲ (liquid of fermented sauce), olive oil (zayt), some spices, a small amount of sugar, wine vinegar, and 5 walnuts that have been shelled and crushed. [When meat is cooked], break some eggs on it and let them set [with the steam of the pot], God willing.

A recipe for mis̲h̲mis̲h̲iyya (apricot stew)

Clean and wash a plump chicken. Disjoint it and put it aside. Choose ripe apricots, which are yellow and sour. Put them in a pot with some water and bring them to a boil. Press and mash them with the water they were boiled in, and strain them into a bowl.Now go back to the chicken, put it in a clean pot and add the white part of fresh onion (bayāḍ baṣal), cilantro, and rue [all chopped]. Add as well a piece of galangal, a stick of cassia, and whole pieces of ginger. Light the fire underneath the pot and let it cook. Then sprinkle the pot with onion juice and add enough of the strained apricot liquid to submerge the chicken. Season the pot with coriander seeds, black pepper, and cassia, all ground.Let the pot simmer until [chicken is] cooked and serve it.

For the bustāniyya, I had fresh plums (probably much sweeter than the ones available in period), frozen sweet cherries (definitely sweeter), and I left out the sugar to compensate. Last time I made this was over a slow fire, outdoors, and two different people asked if there was chocolate in it - at least in part due to the colour it arrives at. The plums this time were very juicy, and there was rather too much liquid overall, so that the eggs at the end were submerged and poached, rather than sitting on top to steam. I think the walnuts might be intended as a thickener, rather than anything else - I had them down to a grit, but not to a powder, so they didn't really work that way. "Some spices" is unusually unhelpful for al-Warraq, but I used some cinnamon and ginger. The spices tasted stronger in this than in the other dish.

The mis̲h̲mis̲h̲iyya I've done a few times now, and it's starting to enter my rotation as just another dish I can do at short notice. Chicken and apricots are a good combination in any cuisine, and I'm pretty sure I've seen tagine recipes very much like this. As usual, I left out the rue, because nobody ever knows if they're allergic to it or not, and I don't fancy someone finding out from my cooking.

Both were served with plain rice and stack of pita and naan bread.

They went down well in general, the mis̲h̲mis̲h̲iyya more so (a few people took some home, too). The bustāniyya had 12 eggs in it, and I've only accounted for about four of them being eaten, so either eight people ate them and didn't notice, or were so horrified by the discovery they couldn't talk about it. Daniel was amused; he'd expected his to be a large chunk of chicken, and was very puzzled by finding white and yolk when he cut into it. I suspect that the bustāniyya might actually be better with just the juices, as written, so that'll be the next thing to try.

#sca#medieval food#medieval cookery#medieval cooking#medieval arabic food#sca cookery#food history#arabic food#al warraq#nawal nasrallah#fruit#chicken

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

[ID: A wide cylindrical pile of rice, eggplants, and 'lamb' on a serving platter, garnished with parsley. End ID]

مقلوبة / Maqluba

مَقْلُوبَة ("maqlūba," "upside down" or "turned over") is a Levantine casserole in which spiced meat, fried vegetables, and rice are arranged in a pot and simmered; the entire pot is then inverted onto a serving tray to reveal the layered ingredients. Maqluba historically uses lamb and eggplant, but modern recipes more often call for chicken; tomato, cauliflower, potato, bell pepper, and peas are other relatively recent additions to the repertoire.

A well-made maqluba should be aromatic and highly spiced; the meat and vegetables should be very tender; and the rice should be cohesive without being mushy. A side of yoghurt gives a tangy, creamy lift that cuts through and complements the spice and fat in the dish.

Maqluba emphasizes communal eating and presentation. It is usually eaten during gatherings and special occasions, especially during Ramadan—a month of sunrise-to-sunset fasting which celebrates the revelation of the Qu'ran to the prophet Mohammad. The pot is sometimes flipped over at the table for a dramatic reveal.

History

Many sources cite Muhammad bin Hasan al-Baghdadi's 1226 Kitāb al-ṭabīkh (كتاب الطبيخ لمحمد بن حسن البغدادي) as containing the first known reference to maqluba. However, the recipes for "maqluba" in this book are actually for small, pan-fried patties of spiced ground meat. [1] The dish is presumably titled "maqluba" because, once one side is fried, the cook is instructed to turn the patties over ("أقلب الوجه الآخر") to brown the other; the identical name to the modern dish is thus coincidental.

References to dishes more like modern maqluba occur elsewhere. A type of مغمومة ("maghmūma," "covered" dish), consisting of layers of meat, eggplant, and rice, covered with flatbread, cooked and then inverted onto a serving plate, is described in a 9th-century poem by إبراهيم بن المهدي (Ibrāhīm ibn al-Mahdī):

A layer of meat underneath of which lies a layer of its own fat, and another of sweet onion, another of rice,

Another of peeled eggplant slices, each looking like a good dirham honestly earned. [...]

Thus layered the pot is brought to a boil first then enclosed with a disc of oven bread.

On the glowing fire it is then put, thus giving it what it needs of heat and fat.

When fully cooked and its fat is well up, turn it over onto a platter, big and wide. (trans. Nawal Nasrallah) [2]

These sources are both Iraqi, but one story holds that maqluba originated in Jerusalem. صلاح الدين الأيوبي (Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn al-Ayyūbi; "Saladin"), after capturing the city from the Crusaders and reinstating Muslim rule in 1187, was served the dish, and was the first to describe it with its current name. Before this point, the Jerusalem specialty had supposedly been known as "باذنجانية" ("bāḏinjānīyya"), from "باذنجان" "bāḏinjān" "eggplant" + ية- "-iyya," a noun-forming suffix.

[ID: The same dish shown from directly above. End ID]

In Palestine

Maqluba is often invoked in the context of Palestinian strength and resistance, in defiance of its occasional description as an "Israeli" dish. Palestinian magazine writer Aleeya Rizvi reflects:

In the wake of the recent [2023] war in Gaza, our culinary endeavors, particularly in crafting and sharing traditional Palestinian dishes like Maqluba, represent a conscious effort to contribute to the preservation and resilience of Palestinian culture. In a time when cultural heritage is under threat, preparing and enjoying these time-honored recipes becomes more than a mere culinary activity; it transforms into a deliberate act of cultural continuity and solidarity.

Maqluba also has a more specific association with physical resistance against the backdrop of increased settler and police violence against Palestinians, including regular Israeli raids and attacks on the جامع الأقصى ("Jāmi' al-Aqṣā"; al-Aqsa mosque), during Ramadan.

The holiest month in the Islamic calendar, Ramadan is given over to fasting, prayer, and reflection; people gather together in homes and mosques to break their fast after sunset, and spend entire nights in mosques in worship. Khadija Khwais and Hanady Al-Halawani used to serve maqluba for افطار ("ifṭār," fast-breaking meal) in the Al-Aqsa mosque, until Israeli occupation authorities banned them from the mosque for "incitement."

In response, starting in 2015, Al-Halawani and other volunteer مرابطين ("murābiṭīn," lit. "holy people," guardians of the mosque) stationed themselves on the ground outside the mosque's gate (باب السلسلة; Bāb as-Silsila, "chain gate") to prepare and serve maqluba. Those who were banned from entering the mosque broke their fast and prayed at the mosque's gates, and in the nearby alleys of the Old City. The same year saw Israeli security personnel and settlers attack Palestinian protestors and guardians outside and inside the mosque with tear gas and stun grenades.

For Al-Halawani, the serving of maqluba at the al-Aqsa gates symbolizes "defiance, steadfastness, and insistence on continuing the fast [...] in spite of the occupation’s practices." The "Maqluba at al-Aqsa" ritual "has become one of the most disturbing Palestinian scenes for the occupation forces," who associate it with the defense of "Palestinian heritage" and the intent to "motivate worshipers and murabitin to repel incursions into the mosque." (Al-Halawani has been arrested, threatened, beaten, and detained by Israeli police multiple times for her role as a defender of Al-Aqsa. She was among the prisoners freed in trades between Israel and Hamas in December 2023.)

In 2017, occupation forces installed metal detectors, electronic gates, metal barriers, and police cameras to surveil worshipers following a shoot-out at one of al Aqsa's gates. Hundreds of protesters refused to enter the mosque until the repressive measures were removed, instead gathering and praying in its courtyard; surrounding families bolstered the sit-ins by serving food and drink. When the gates were dismantled, over 50,000 people gathered to eat maqluba in celebration, picking up on the earlier association of the dish with Saladin's victory (and its resultant alternate name, "أكلة النصر," "ʔakla an-naṣr," "victory meal").

The name "maqluba," meaning "upside-down" or "inverted," may be associated with victory and resistance as well. Fatema Khader noted in 2023 that the method of serving maqluba was a "symbolic representation of how Israeli policies and decisions against Palestinians will be flipped on their heads and become rendered meaningless." It is also relevant that maqluba is meant to be served to large groups of people, and can thus be linked, symbolically and literally, to solidarity and communal resistance.

This year in Gaza, Palestinians show steadfast optimism as they paint murals, hang lanterns, buy sweets, hold parties, and pray in groups amongst the rubble where mosques once stood. But despite these efforts at creating joy, the dire circumstances take heavy tolls, and the holiday cannot be celebrated as usual: Israel's campaign of slow starvation led Ghazzawi Diab al-Zaza to comment, "We have been fasting almost against our will for three months".

Donate to provide hot meals in Gaza for Ramadan

[1] Also reprinted in Mosul: Umm Al-Rubi'in Press (مطبعة ام الربيعين) (1934), p. 57. For an English translation see Charles Perry, A Baghdad Cookery Book (2005), pp. 77-8.

[2] This poem, as well as one of Ibn al-Mahdi's maghmuma dishes, were compiled in Ibn Sayyar al-Warraq's 10th-century Book of Dishes (كتاب الطبيخ وإصلاح الأغذية المأكولات وطيّبات الأطعمة المصنو; "Kitāb al-ṭabīkh waʔiṣlāḥ al-ʔaghdiyat al-maʔkūlāt waṭayyibāt ʔaṭ'ima al-maṣno," "Book of cookery, food reform, delicacies, and prepared foods"), p. 99 recto. For Nasrallah's English translation see Annals of the Caliph's Kitchens, pp. 313-4.

In the 14th-century Andalusian Cookbook (كتاب الطبيخ في المغرب والأندلس في عصر الموحدين، للمكلف المجهول; "Kitāb al-ṭabīkh fī al-Maghrib wa al-Andalus fī ʻaṣr al-Mawahḥidīn," "Book of cookery from the Maghreb and Andalusia in the era of Almohads"), a maghmuma recipe appears as "لون مغموم لابن المهدى", "maghmum by Ibn al-Mahdi". For an English translation see An Anonymous Andalusian Cookbook, trans. Perry et al.

Ingredients:

For a 6-qt stockpot. Serves 12.

For the meat:

1 recipe seitan lamb

or

2 cups (330g) ground beef substitute

1 cinnamon stick

1 bay laurel leaf

Pinch ground cardamom

Several cracks black pepper

For the dish:

3 cups (600g) Egyptian rice

2 medium-sized globe eggplants

2 large Yukon gold potatoes (optional)

Vegetarian 'chicken' or 'beef' bouillon cube (optional)

2 1/2 tsp table salt (1 1/2 tsp, if using bouillon)

Vegetable oil, to deep-fry

Fried pine nuts or sliced blanched almonds, to top

Egyptian rice is the traditional choice in this dish, but many modern recipes use basmati.

I kept my ingredients list fairly simple, but you can also consider adding cauliflower, carrots, peas, chickpeas, zucchini, bell pepper, and/or tomato to preference (especially if omitting meat substitutes).

For the spices:

1 1/2 Tbsp maqluba spices

or

1 4" piece (3g) cinnamon bark, toasted and ground (1 1/2 tsp ground cinnamon)

3/4 tsp (2.2g) ground turmeric

3/4 tsp (1.5g) cloves, toasted and ground

3/4 tsp (2.2g) black peppercorns, toasted and ground

15 green cardamom pods (4.5g), toasted, seeds removed, and ground (or 3/4 tsp ground cardamom)

Instructions:

For the meat:

1. Prepare the seitan lamb, if using: it will need to be started several hours early, or the night before.

2. If using ground meat: heat 2 tsp oil in a skillet on medium. Add cinnamon stick and bay leaf and fry for 30 seconds until fragrant.

3. Add meat and ground spices and fry, agitating occasionally, until browned. Set aside.

For the dish:

2. Rinse rice 2 to 3 times, until water runs almost clear. Soak in cold water for 30 minutes, while you prepare the vegetables.

3. Optional: to achieve a presentation with eggplant on the sides of the maqluba, remove the skin from either side of one eggplant (so that all slices have flesh exposed on both sides) and then cut lengthwise into 1/2" (1cm)-thick slices.

Cut the other eggplant (or both eggplants) widthwise into coins and half-coins.

4. Sprinkle eggplant slices with salt on both sides and leave for 10-15 minutes to release water.

5. Peel potatoes and cut in 1/4" (1/2 cm) slices.

6. Heat about an inch of oil in a deep skillet or wok on medium (a potato slice dropped in should immediately form bubbles). Fry the potato slices until golden brown, then remove onto a paper-towel-lined plate or wire cooling rack.

7. Press eggplant slices on both sides with a towel to remove moisture. Fry in the same oil until translucent and golden brown, then remove as before.

Fry other vegetables (except for tomato, chickpeas, and peas) the same way, if using.

8. Drain rice. Whisk bouillon, salt, and ground spices into several cups of hot water.

9. Prepare a large, thick-bottomed pot with a circle of oiled parchment paper (or with a layer of sliced tomatoes). Add ground meat, if using. Layer widthwise-sliced eggplants into the pot, followed by potatoes. Place longitudinally sliced eggplants around the sides of the pot, large side up.

10. Add rice and pack in. Fold eggplant slices down over the rice, if they protrude.

11. Pour broth into the pot, being careful not to upset the rice. Add more water if necessary, so that the rice is covered by about an inch.

12. Heat on medium to bring to a boil. Reduce heat to low, cover with a closely fitting lid, and cook 30 minutes.

13. If rice is not fully cooked after 30 minutes, lightly stir and add another cup of water. Re-cover and cook another 15 minutes. Check again and repeat as necessary.

14. Allow maqluba to rest for half an hour before flipping for best results. Place a large platter upside-down over the mouth of the pot, then flip both over in one smooth motion. Tap the bottom of the pot to release, and leave for a few minutes to allow the maqluba to drop.

15. Slowly lift the pot straight up, rotating slightly if the sides seem stuck.

16. Top with fried seitan lamb, chopped parsley, and fried pine nuts or almonds, as desired.

365 notes

·

View notes

Text

My great-aunt Victoria (Toya) Levy was an incredible woman. Born in Baghdad in 1922, she moved to Israel with her husband in 1950 to start a new life. They lived in a tiny house surrounded by fruit trees that they planted in the small town of Yavneh, where Toya dedicated her life to helping children from broken families.

She was an amazing cook — and a generous one, too. Shortly after we got married, my husband and I spent a day with her to learn the secrets of Iraqi Jewish cooking from the best.

That day, Toya taught us how to make t’beet, a Shabbat dish of stuffed chicken with rice cooked overnight, and kubbeh batata: potato fritters stuffed with ground beef. In her tiny kitchen, she also taught us to make meatballs in a dried apricot and tomato sauce. Of all the dishes, this was the only one that my grandmother never made and so I was not familiar with it. Yet its flavors stuck with me. The simple ingredients — sour dried apricots, tomato, lemon juice, raisins and just a few spices — somehow made a dish much greater than the sum of its parts. The meatballs were so tender and rich, and the sauce was sweet and sour, a combination that Iraqi Jews love.

My great-aunt Toya passed away years ago. I had somehow forgotten this wonderful recipe and when I tried to research the dish, I found different versions of it in almost every Iraqi and Iraqi Jewish cookbook I searched in. The dish was called mishmishiya or kofta mishmishiya (“mishmish” means apricot in both Arabic and Hebrew), ingryieh (a name that I saw only in a Jewish cookbook) or margat hamidh-Hilu. Interestingly, all the Jewish versions included meatballs, while Islamic recipes used stew meat. I assume this had to do with the cost of ingredients and the fact that most Jewish recipes were written by Iraqi Jews who moved to Israel, where stew meat was much more expensive than ground beef.

According to Nawal Nasrallah’s “Delights From the Garden of Eden,” which researches the ancient cuisine of Iraq, the roots of this stew can be traced back to the Babylonian and Assyrian days (19th-6th centuries B.C.). A similar recipe, called mishmishiya, is also documented in Al-Baghdadi’s book “Kitab al Tabikh” from Medieval Baghdad. It calls for fresh apricots of a sour variety. Back then, of course, tomatoes from the New World were not available and, in fact, the original mishmishiya was also known as the “white stew.” Since Jews were living in Iraq from the destruction of the First Temple in 586 B.C., I feel a real connection to this humble stew’s long history.

Of all the recipes I found, my great-aunt Toya’s version is the best. Her apricot meatballs have become a family favorite; the 2,000-year-old dish from worlds away lives on, now with our kids.

Dried apricots are available all year long, but I still think this dish is most suitable for a summer dinner. The apricots, with their bright color and flavor, mirror sunny summer days, not to mention the fact that this easy and fast recipe is perfect for those of us who want to spend as little time as possible over the stove when temperatures outside are soaring.

Notes:

The recipe calls for dried apricots with no added sugar. They are available at specialty supermarkets such as Whole Foods and Trader Joe’s. If you’re using sweetened dried apricots, reduce the sugar in the sauce to 2 teaspoons.

The original recipe included raisins in the sauce, which I chose to omit, but you can add those for extra sweetness.

Store the cooked meatballs in a sealed container in the fridge for up to four days.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mesopotamian heritage explored through the history of cooking

It was sometime in 1990 when Iraq was going through another wave of political and military turmoil under former president Saddam Hussein that Nawal Nasrallah, at the time a professor of English literature and linguistics, arrived on the East Coast of the United States.

As Dina Ezzat describes in the Egyptian weekly Al-Ahram, having a passion for the quality food that she had long enjoyed wherever she had lived in Iraq, Nasrallah, like many Arab expatriates, connected with her home country while abroad through its traditional recipes.

With the passing of time, Nasrallah’s cooking evolved from being a way to satisfy her homesickness to an incitement to do research about the history of these delightful meals, however, not just in terms of the evolution of the recipes, but also in terms of documenting the long history of Iraqi cuisine.

Eventually, she ended up being the translator of several ancient cookbooks, including classics from the 10th, 13th, and 14th centuries that offer a thorough insight into culinary culture, not just in Iraq but also in other countries that were once controlled by the mediaeval Abbasid Dynasty in Baghdad.

Published in 2003, another crucial moment in the modern history of Iraq, Nasrallah’s Delights from the Garden of Eden introduced Iraqi cuisine in both its past and present guise to a world that may have known more about Saddam’s political and military adventures.

The title was the culmination of thorough research into the history of mediaeval Arab cuisine that had led Nasrallah to translate a 10th-century classic by Ibn Sayyar Al-Warraq called Kitab Al-Tabikh (Cookbook) that came out in English as Annals of the Caliphs’ Kitchens.

There were also her translations of the Best of Delectable Foods and Dishes from Al-Andalus and Al-Maghrib, a cookbook by the 13th-century Andalusian scholar Ibn Razin al-Tujibi, and the 14th-century Kenz Al-Fawaed fi Tanwia Al-Mawaed that came out under the English title of the Treasure Trove of Benefits and Variety at the Table: A Fourteenth-Century Egyptian Cookbook.

Nasrallah is keen to establish two facts about her work: first, that writing about the history of food is also a type of literature; and second, that a cookbook in the mediaeval context is not just a set of recipes but also includes nutritional facts, cooking techniques, and eating manners.

Through her work on the subject, Nasrallah said, it is not difficult to trace the uninterrupted thread of recipes from Mesopotamia, the Iraq of the Middle Ages, to modern Iraq today.

#manchester#iraq#iraqi#london#uk#baghdad#liverpool#scotland#hussein al-alak#usa#cooking#food#heritage#culture#history#museums#art history#learning#education#teachers#teaching

0 notes

Text

Medieval Hummus

Recipe by Lucien Zayan

Adapted by Ligaya Mishan

The roots of this recipe, an ancestor of modern hummus, date back at least as far as the 13th century, as the Iraqi food historian Nawal Nasrallah writes on her blog, My Iraqi Kitchen. As adapted by Lucien Zayan, a Frenchman of Egyptian and Syrian descent who runs the Invisible Dog Art Center in Brooklyn, you boil chickpeas until their skins loosen and they reveal themselves, tender little hulks with souls of butter. Then you mash them in a swirl of tahini, olive oil, vinegar, spices and herbs, and fold in a crush of nuts, seeds and preserved lemon, sour-bright and tasting of aged sun. Notably absent from the recipe is garlic. Here, instead, the nuts — Mr. Zayan uses hazelnuts, for more butteriness, and pistachios, with their hint of camphor — fortify the chickpeas in their earthy heft, so close to the richness of meat.

Time: 30 minutes

Yield: about 4.5 cups

Ingredients:

1/3 cup raw hazelnuts

1 1/2 tablespoons caraway seeds

1 tablespoons coriander seeds

1 1/2 teaspoons sesame seeds

1/4 cup shelled, roasted unsalted pistachios

5 mint leaves

1 small sprig tarragon, leaves only

3 1/2 cups cooked, drained chickpeas (two 15-ounce cans or homemade from 8 ounces dried chickpeas)

1/2 cup tahini

1/4 cup olive oil, plus more for drizzling

2 tablespoons fresh lemon juice, plus more to taste*

1/2 tablespoon ground sumac, plus more for sprinkling

1 1/2 teaspoons rice vinegar

Salt

1/2 cup ice-cold water

*Tip: Instead of lemon juice, Lucien Zayan uses half of a preserved lemon (preferably made with minimal salt) and adds a splash of its liquid along with the ice water.

Preparation

Step 1

In a small skillet over medium-low heat, toast the hazelnuts, stirring occasionally, until fragrant and the skins begin to split, 3 to 4 minutes. Then transfer to a plate lined with a paper towel. When cool, gently rub off the skins and discard.

Step 2

Using the same pan, toast the caraway, coriander, and sesame seeds, stirring occasionally, until fragrant, about 2 minutes. Remove from heat to cool slightly (seeds will continue to toast).

Step 3

Add the toasted hazelnuts and the pistachios to a food processor and pulse until they release their oils and make a compact paste. Add the mint and tarragon and pulse to combine.

Step 4

Add the chickpeas to the mixture in the food processor, reserving a handful for garnish. Then add the tahini, olive oil, lemon juice, the toasted seeds, sumac, rice vinegar, and a pinch of salt. Start pulsing and gradually add the ice water, splash by splash, until creamy and smooth. Taste and add more lemon juice or salt, as desired.

Serve drizzled with olive oil, dusted with sumac, and finish with a few chickpeas on top.

0 notes

Text

Gedenkfeier auch in der Küche

Ganz nach guter alter Tradition: Dass Küche und Kultur zusammengehören, zeigt Nawal Nasrallah mit ihrem Vortrag: "Food Culture and History in the Middle East". Die Begrüssung zu Beginn an "Nina" laut meines Screen dient natürlich in keinster Form der Ansprache an unsere "Partner mit eigenen Interessen" auch auf den Rechnern, wir haben aber dennoch in den Filialen des Hotel Chelsea auch auf den Dienstrechnern weiteres Material zu holen bei der geführten Wanderung. Der General, "Betreut" mit Kooperierenden Einheiten holt mehr Material. "Nina" und Hilfsgenossen! Und, ich betone es immer wieder: Gut, dass wir uns selbst an solchen Tagen wie dem 9. November bei der Gedenkfeier der Kosher Nostra mit Richter alle weiterbilden können! Dürfen wir einen weiteren Kollegen der Polizeistation Worms reichen auch zur Betreuung? Und mit Dienstrechner? Zeithistorisch gesehen auch nicht so neu! Finden Sie nicht auch? Rosinante? Auch wieder wollen? Ein kleines Intermezzo gegen 18 : 00 Uhr bei der gezielten Ansprache zum Daten-Transfer führt zum etwas schlagartigen Druck auf das Ohr rechts? Das Technikprotokoll versagt bestimmt wieder. Und wir haben gleich wieder noch mehr. Essen! Gut. Und Sie? Sie wollten für wen sammeln? Ja bitte? Heringe? Stimmt. Cyberfeld KI. Wir haben Hunger! Siehe die Anmerkungen im Beitrag zum 9. November unten!

0 notes

Text

Publication Day: 'Best of Delectable Foods and Dishes from al-Andalus and al-Maghrib,' a 13th-century Cookbook

Publication Day: ‘Best of Delectable Foods and Dishes from al-Andalus and al-Maghrib,’ a 13th-century Cookbook

The English translation of the thirteenth-century cookbook Fiḍālat al-khiwān fī ṭayyibāt al- ṭaʿām wa-l-alwān by the Andalusi scholar Ibn Razīn al-Tujībī is out in translation — with introduction and glossary — by leading food scholar and translator Nawal Nasrallah:

This thirteenth-century cookbook, published in English as Best of Delectable Foods and Dishes from al-Andalus and al-Maghrib,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Una de personajes femeninos por el día de la mujer

Una de personajes femeninos por el día de la mujer

Sherezade, Imán, Aala, Halima, Salma, Nezha, Amira, Muna, Malika, Karima, Firdaus, Muna, Dilshad, Máriam, Huda, Nawal, Quisma, Kaouther, Hayat, Núria, Mathilde, Zalya, Assia, Hasana, Fátima, Amina, Abderrahmán,…

Nombres de mujeres árabes protagonistas de novelas, autoras de las mismas o, simplemente, que me forman parte de mi vida en alguna forma. Este es mi pequeño homenaje a las mujeres que…

View On WordPress

#Día de la mujer#Emily Nasrallah#Líbano#Leila Slimani#Libia#Mujer#Mujer en punto cero#Nawal Al-Saadawi#Sudán

1 note

·

View note

Text

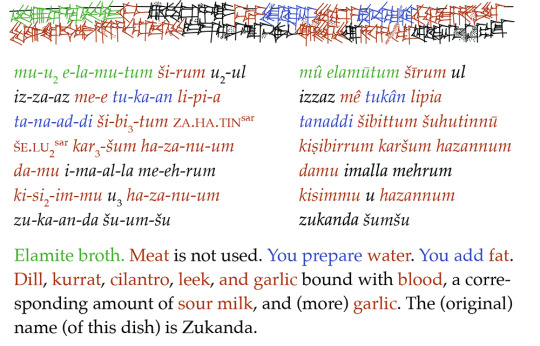

Ancient Mesopotamian Recipe: Elamite Broth

Image description: The same text in four forms, with color coding showing the nouns, verbs, and subject of the text. The top is in the ancient-Babylonian script. The middle using the Latin alphabet to transliterate it, twice. At the bottom is the English translation. It reads:

Elamite broth. Meat is not used. You prepare water. You add fat. Dill, kurray, cilantro, leek, and garlic bound with blood, a corresponding amount of sour milk, and (more) garlic. The (original) name of this dish is Zukanda.

End image description.

The recipe was creating using pig's blood, though the chefs said "the blood of sheep would be better." The recipe is approximately 4,000 years old. Translation from the Yale culinary tablets by Gojko Barhamovic, Patricia Jurado Gonzalez, Chelsea A. Graham, Agnete W. Lassen, Nawal Nasrallah, and Pia M. Sörensen.

#history#babylon#food#iraq#iraqi culture#iraqi food#iraqi cuisine#ancient#antiquity#tw food#tw blood

77 notes

·

View notes

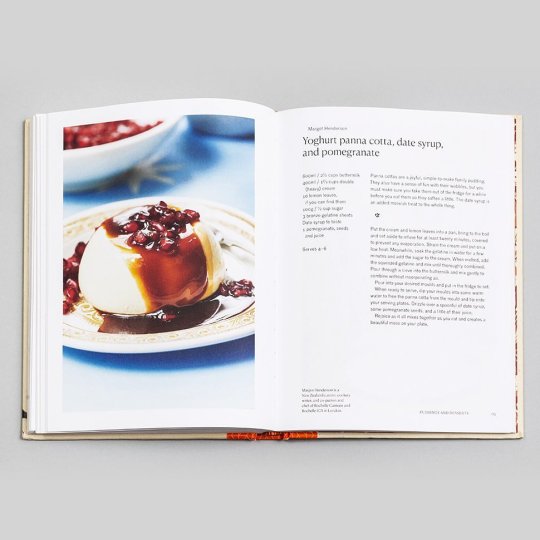

Photo

For Passover, may we recommend 'A House with a Date Palm Will Never Starve (Cooking with Date Syrup: Forty-One Chefs and an Artist Create New and Classic Dishes with a Traditional Middle Eastern Ingredient),' edited by Michael Rakowitz and published by @art_books_ Art and food meet social activism in Rakowitz’s inspiring cookbook, in which forty-one noted international chefs, restauranteurs and food writers contribute recipes featuring the traditional Middle Eastern ingredient that also plays a key role in Rakowitz’s artwork. “Food becomes very important in exile,” Claudia Roden writes. “Families hold on to their dishes for generations, long after they have cast off their traditional clothes, dropped their native language and stopped listening to their own forms of music. Michael’s family fled Iraq for the United States in 1947 as a result of riots and reprisals against Jews. He has used cooking as a way of celebrating the family’s origin and the harmony that once reigned between Jews and Muslims.” Chefs include: Sara Ahmad, Sam and Sam Clark (Moro, Morito), Linda Dangoor, Caroline Eden, Cameron Emirali (10 Greek Street), Eleanor Ford, Jason Hammel (Lula Café, Marisol), Stephen Harris (The Sportsman), Anissa Helou, Margot Henderson (Rochelle Canteen), Olia Hercules, Charlie Hibbert (Thyme), Anna Jones, Philip Juma (JUMA Kitchen), Reem Kassis, Asma Khan (Darjeeling Express), Florence Knight, Jeremy Lee (Quo Vadis), Prue Leith, Giorgio Locatelli, Nuno Mendes (Chiltern Firehouse), Thomasina Miers (Wahaca), Nawal Nasrallah, Russell Norman (Polpo), Yotam Ottolenghi (Ottolenghi, NOPI), Sarit Packer and Itamar Srulovich (Honey & Co), Michael Rakowitz, Yvonne Rakowitz, Brett Redman (Neptune, Jidori, Elliot's Café), Claudia Roden, Nasrin Rooghani, Marcus Samuelsson (Red Rooster, Aquavit), Niki Segnit, Rosie Sykes, Summer Thomas, Kitty Travers, Alice Waters (Chez Panisse) and Soli Zardosht (Zardosht). Read more via linkinbio. #michaelrakowitz #housewithadatepalmwillneverstarve #middleeasternrecipes #datepalm #datesyrup #cookbook #passoverrecipes https://www.instagram.com/p/CcYjcMaJys6/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#michaelrakowitz#housewithadatepalmwillneverstarve#middleeasternrecipes#datepalm#datesyrup#cookbook#passoverrecipes

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Iṭriya (meat dish with dried noodles)

Iṭriya is recipe 86 in the Kanz; page 130 in Nawal Nasrallah's translation, which is the version I'm using. I've cooked this a few times now; a couple of times for Dun in Mara Arts & Science Days, and once for the Travellers' Fare (Friday evening meal, as people are arriving) at Crown just gone.

I say I've cooked this: I actually change it so much it's almost certainly a different dish. But I feel the spirit survives.

Here's Nasrallah's text:

You need meat and dried noodles (iṭriya), black pepper and a bit of coriander for the meatballs (mudaqqaqa). Make meatballs with a small amount of the meat. Pound the meat with a bit of black pepper, coriander, and baked onion. [As for the rest of the meat,] boil it, strain it, and brown it [in fat]. Pound black pepper and cilantro and add them to the [fried] meat. Pour the [strained] broth on them, and when the pot comes to a boil, throw in the meatballs. [Continue cooking] until done.Add dried noodles to the pot, along with snippets of dill (ḥalqat shabath), and a small amount of soaked chickpeas. [Let the pot cook] and then simmer, and serve.

Meat, as ever for the Arabic recipes, should be mutton, and owing to the unavailability of mutton here, I use lamb. Iṭriya itself is noted in a glossary as "thin dried strings of noodles, purchased from the market and measured by cooks in handfuls". I did a bit of poking around as to what might best represent that, and while I do intend to try some Middle Eastern shops and see what they have, wholewheat spaghetti doesn't seem horribly wrong.

I've tried making the meatballs in two ways - with minced lamb, and with chopped lamb (Lady Erin's cleaver skills were employed for this at Crown). Chopped is way better, and this is not the first time I've noticed this - chopped meat and minced meat ("ground meat" for the Americans) are two very different things. A lot of Irish people seem to have the genetic trait whereby coriander tastes like soap, so I substitute parsley. And while I've tried both baked and fried onion, I didn't observe a lot of difference, so I keep using the easier fried version. I kept the black pepper, though!

A good few dishes in both al-Warraq and the Kanz use both meat and meatballs. I really like the effect, I have to say; it gives textural variation without mixing different things and thereby muddying the taste.

"Soaked chickpeas" becomes canned chickpeas, and I think they're not too different. They go very well with the lamb and the parsley. And the dill I add as written.

The overall dish is a dense, hearty thing, with the noodles/spaghetti leading, and plenty of meat in among them. It's a good dish for people arriving at an event, and it's been popular every time I've cooked it. Lady Aoife, who usually eschews carbohydrates, has been known to curse my name and reach for the tongs when it appears.

#medieval cookery#sca cookery#food history#sca#medieval arabic food#the kanz#nawal nasrallah#nasrallah#itriya#noodles

1 note

·

View note

Link

Caliphs may have even cooked competitively. According to one story, the caliph al-Maʾmūn, who reigned in the early ninth century, once faced off against his brother and boon companions. It was an “Iron Chef of medieval times,” laughs [Nawal] Nasrallah. In her description of the event, a cook named ‘Ibāda was present. Described as having a “delightful and mischievous sense of humor,” he was nonetheless jealous when al-Muʿtaṣim, al-Maʾmūn’s brother, cooked a dish that smelled quite good. He coaxed al-Muʿtaṣim into adding a bowl of fermented sauce to his dish, which then gave off a nasty odor. In true sibling fashion, al-Maʾmūn roasted his brother mercilessly.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

My great-aunt Victoria (Toya) Levy was an incredible woman. Born in Baghdad in 1922, she moved to Israel with her husband in 1950 to start a new life. They lived in a tiny house surrounded by fruit trees that they planted in the small town of Yavneh, where Toya dedicated her life to helping children from broken families.

She was an amazing cook — and a generous one, too. Shortly after we got married, my husband and I spent a day with her to learn the secrets of Iraqi Jewish cooking from the best.

That day, Toya taught us how to make t’beet, a Shabbat dish of stuffed chicken with rice cooked overnight, and kubbeh batata: potato fritters stuffed with ground beef. In her tiny kitchen, she also taught us to make meatballs in a dried apricot and tomato sauce. Of all the dishes, this was the only one that my grandmother never made and so I was not familiar with it. Yet its flavors stuck with me. The simple ingredients — sour dried apricots, tomato, lemon juice, raisins and just a few spices — somehow made a dish much greater than the sum of its parts. The meatballs were so tender and rich, and the sauce was sweet and sour, a combination that Iraqi Jews love.

My great-aunt Toya passed away years ago. I had somehow forgotten this wonderful recipe and when I tried to research the dish, I found different versions of it in almost every Iraqi and Iraqi Jewish cookbook I searched in. The dish was called mishmishiya or kofta mishmishiya (“mishmish” means apricot in both Arabic and Hebrew), ingryieh (a name that I saw only in a Jewish cookbook) or margat hamidh-Hilu. Interestingly, all the Jewish versions included meatballs, while Islamic recipes used stew meat. I assume this had to do with the cost of ingredients and the fact that most Jewish recipes were written by Iraqi Jews who moved to Israel, where stew meat was much more expensive than ground beef.

According to Nawal Nasrallah’s “Delights From the Garden of Eden,” which researches the ancient cuisine of Iraq, the roots of this stew can be traced back to the Babylonian and Assyrian days (19th-6th centuries B.C.). A similar recipe, called mishmishiya, is also documented in Al-Baghdadi’s book “Kitab al Tabikh” from Medieval Baghdad. It calls for fresh apricots of a sour variety. Back then, of course, tomatoes from the New World were not available and, in fact, the original mishmishiya was also known as the “white stew.” Since Jews were living in Iraq from the destruction of the First Temple in 586 B.C., I feel a real connection to this humble stew’s long history.

Of all the recipes I found, my great-aunt Toya’s version is the best. Her apricot meatballs have become a family favorite; the 2,000-year-old dish from worlds away lives on, now with our kids.

Dried apricots are available all year long, but I still think this dish is most suitable for a summer dinner. The apricots, with their bright color and flavor, mirror sunny summer days, not to mention the fact that this easy and fast recipe is perfect for those of us who want to spend as little time as possible over the stove when temperatures outside are soaring.

Notes:

The recipe calls for dried apricots with no added sugar. They are available at specialty supermarkets such as Whole Foods and Trader Joe’s. If you’re using sweetened dried apricots, reduce the sugar in the sauce to 2 teaspoons.

The original recipe included raisins in the sauce, which I chose to omit, but you can add those for extra sweetness.

Store the cooked meatballs in a sealed container in the fridge for up to four days.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#بلادي_الجميلة ❤ #مصر ❤

What Was Cooking in Medieval Cairo?

"Medieval visitors to Egypt never failed to be captivated by the uniqueness of its agricultural landscape. The Nile, they said, flowed from paradise...

https://t.co/lwDDgFwMJp

#egypt#medieval cairo#medieval egypt#cooking#cooking books#recipe#recipes#dishes#MASRZAMAN#culture#مصر#مصريات#تاريخ مصر#اطباق مصرية#فن الطهي#islam#islamic egypt#sultan#good reads#research#history#ancient history#medieval history#travel#markets#kitchen#egyptians#egyptian#Egyptian kitchen#المطبخ المصري

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Publication Day: ‘Best of Delectable Foods and Dishes from al-Andalus and al-Maghrib,’ a 13th-century Cookbook – ArabLit & ArabLit Quarterly

Publication Day: ‘Best of Delectable Foods and Dishes from al-Andalus and al-Maghrib,’ a 13th-century Cookbook – ArabLit & ArabLit Quarterly

The English translation of the thirteenth-century cookbook Fiḍālat al-khiwān fī ṭayyibāt al- ṭaʿām wa-l-alwān by the Andalusi scholar Ibn Razīn al-Tujībī is out in translation — with introduction and glossary — by leading food scholar and translator Nawal Nasrallah:

Source: Publication Day: ‘Best of Delectable Foods and Dishes from al-Andalus and al-Maghrib,’ a 13th-century Cookbook – ArabLit &…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Sweet-and-Sour Fish with Raisin and Date Sauce

A House With A Date Palm Will Never Starve

Chef Nawal Nasrallah

0 notes