#nerdanel is HIS top

Text

Indis is about to steal his girl

909 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think Fëanor should be put in an odyssey >:3c

#the little face at the end is imperative to the narrative#instead of nerdanel fending off suitors#it’s her deciding if she should remarry and block feanor reembodiement#so on top of everything an odyssey implies#feanor also has a time crunch#i need this elf desperate to see his wife again ok!#silmarillion#feanorians#the silmarillion#silm#feanor#tolkien#house of feanor#feanor x nerdanel#feanel

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've been rereading Here Be Dragons by thorinoakentwig and I've been daydreaming of the concept of Maedhros (after his death and being sent to the void) begging for redemption, if not for himself then at least for his brothers and father for failing to complete the oath. Eru listens to him and grants him his wish, allowing his family to rest in Mando’s halls instead of the void. Feanor is furious, not for being upstaged or whatever, but at the idea of his son suffering for him, more than he already has

(Fingon got to see a glimpse of red hair that burned like molten lava in the Halls before Maedhros was taken again. He closed his eyes for just a moment to feel and settle his grief before moving into action once again)

As per their agreement, Maedhros must save a life for every one he and his kin have ruined, however, he is not sent back as an Elf, but instead is reborn again and again in the form of Men and Dwarves and Hobbits with their mortal lifespans and limitations. He struggles with each rebirth to remember the last one, for mortal memories are so flawed compared to those of the Elves, but he gets the sensation of deja vu often and has strange dreams, and knows he has a Purpose.

But no matter the life he lives, he always has brilliant red hair, his eyes are always light in colour if not grey, he is always tall for his race, and at some point in his life he will loose a hand. Its not always in response to the Enemy- one lifetime he was whittling a toy horse and cut his palm, which became so infected that it had to be amputated.

He goes around helping people, as a doctor, a smith, a teacher, but more often than not he feels at home with a blade in his hand and the burden of responsibility for a people on his shoulders. He has led armies, villages, bands of mercenaries, counciled lords and ladies, and on one occasion commanded a ship full of Men. He never knows why he has such a drive to help people, why helping makes him feel so guilty, why he has nightmares of dark shadows and pain and three brilliant lights, why the chill of winter makes him feel safe, why he's always wanted a large family yet never once in all his reincarnation has had any desire to marry.

That is, until one day when he is reborn as a Man by the name of Doegred, he is take to the sea side by his parents as a gift for his 6th birthday. He looks west and is filled with such a profound longing that when asked whats wrong, he points towards the setting sun and says "i used to live there. I miss my home." As the sun sets, and as his parents digest the strange statement of their son, a voice comes floating by on the wind.

Its melodic, but melancholic in such a profound way that it moves all those that hear it to tears. Young Doegred tears away from his parents and races down the sand towards the vpice, red hair snapping behind him like licks of flame. Once his parents catch up to him, they are met with a strange scene.

An Elf, for no other being is as tall or looks as beautiful even in such a neglected state, is knelt on the shore, weeping and clutching their son to him as if he is afraid he'll vanish if he lets go. Doegred, for all that is worth, is making calming soothing croons while patting the matted hair of the Elf. He looks up at his parents, and with a glint in his blue eyes that almost makes them look grey, says "this is my younger brother. I left him behind once and I dont plan on doing so again."

(When they go home, it is with a much cleaner elf named Maglor in tow and much confused acceptance as two exasperated parents of a strange child can bare.)

Maglor stays in their village for a time, helping Doegred help others, until the Man becomes 18 and is leaving home for an adventure. He takes Maglor with him to the Elven city of Eregion, where they meet with the Elven lord there and much tears are shed. Doegred slowly begins to remember his past lives, reliving moments in dreams and second hand from tales told by Maglor and Celebrimbor. They in turn start to learn the full details of his agreement with Eru, of the burden he placed on his shoulders for his kin.

He helps his former nephew with the more political side of running his city, and tries his best to ignore the reverent whispering of the Feanorian Elves. Celebrimbor, not wanting to the news of his guests to spread, shuts his city's gates to outsiders and turns away a slightly peeved Maia in the process.

Doegred ages, as all Men do and it isn't long by Elven standards that he is once again on his deathbed and soon ready to start life once again, to have another turn at penance for he and his family- even if he still does not fully remember them. When Doegred closes his eyes for the last time a city wails at loss, and scouting parties are sent out in search of a red haired babe.

A red dawn breaks with a hobbit babe opening grey eyes for the first time. Black smog forms from the mountains in the southeast. War is the horizon. And a boat sailing from the west comes with two passengers bearing ill tidings and offering support against the growing Evil.

One has hair of spun golden silk, the other with braids of thick ebony ropes. One carries a sword and a flag with a golden flower. The other has only a harp and a bow.

Within the safety of Gladden Fields, the new Hobbit mother adorns her baby's swaddle with a golden ribbon. It seems like it will bring good luck

#maedhros#maglor#Silmarillion#lotr#silm fic#amber rambles#getting this out before it haunts me more lmao#technically Maedhros penance is done by the end of the second age and throughout the 3rd some of his siblings can leave the halls#but Mae is still Guilty and just keeps being reborn#i also think it would be fun if mae is reborn as gimlis older brother#legolas asking gimli to marry him just fucking SWEATING cause the reincarnated Kinslayer is staring him down from waist height#with the OTHER Kinslayer adding a supporting glare behind him with Celebrimbor teasing Thranduil off to the side#elrond is just happy to have some family members back#gloin has come to terms with the fact that elves are just gonna be around his kids#feanor is SEETHING in the halls about having to share Dad status with a bunch of otber ppl#What If He Has A Dad Ranking List And Im Not In The Top 10????#Nerdanel is aldo upset about having to share mom status but also appreciates the help lmao

170 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Thanksgiving! In celebration, have an awkward family dinner scene from my current WIP.

“You know,” Earwen said, taking a careful sip of her wine, “you could petition the Valar.”

This was not a new concept. It had not been tried recently, but Nerdanel still had to pause in her meal for a moment to poke at just why Earwen was presenting it so cautiously.

“On what grounds?” She had certainly tried everything she could think of.

“Precedence, mainly. It is not so different from the case of Finwe and Miriel.”

Arafinwe sat with his fork half frozen between his plate and his mouth. Nerdanel felt half frozen herself, trying to understand. How could the statute of Finwe and Miriel possibly be similar to her own case?

“I know you might not have anyone in mind now,” Earwen continued, “but it might help to already have your right established.”

Her right. Her right to -

To do what everyone had been so insistent she do.

Get up.

Smile.

Move on.

She could get up. She could smile. She could - move.

But to move on? To take someone else in his place?

She was furious with him. Incandescently so. She wanted to claw out those clever, unsatisfied eyes. She wanted to bite out his beautiful, poisonous tongue. She wanted to pour molten rock over him and let it settle around him until he could never move from its confines again.

But to move on? To take someone else?

She imagined someone coming to Feanaro after his vaults had been torn open and telling him it was alright, really, that the Silmarils were gone; look, they had all these pieces of lovely shattered glass, and he was welcome to take his pick between them.

“I could remarry, you mean,” she said, and Feanaro would have known that just because her voice was still, it did not mean she said it calmly. “Have children again, even.”

“If you liked,” Earwen said, though her own voice was careful now.

Nerdanel sipped her wine. “I do not know why you do not take your own advice. You would not even have to appeal to the Valar for it; no one would have the slightest right to object to you and Arafinwe having another child. Then it wouldn’t matter that Aegnor is never going to come out of the Halls.”

Earwen’s face went white.

“Excuse me,” Nerdanel said and left.

. . .

She was already packed by the time Arafinwe came to her room. She had steadied by then, though not calmed.

“She meant well, and I did not,” she conceded without looking up from securing the last of her things. “I won’t trouble you till I’ve thought up a proper apology.”

Everyone remembered that she had fought with Feanaro. No one ever seemed to remember that if it had just been Feanaro raging, it would not have been a fight.

“Please don’t leave,” Arafinwe said wearily, leaning against the door. “We’ve had quite enough of that.”

“It’s what I do,” she said shortly. Hear something horrible. Say something horrible. Leave.

Not come back until it was too late, and he had already sworn that stupid Oath.

He scrubbed a hand across his face. “As your apology to me,” he clarified, “please at least wait until morning.”

She paused.

He looked so very tired.

“Alright,” she conceded. She sank down on top of her bags. “Do you think I should move on?”

It was poking at a bruise for no good reason. Her answer wouldn’t change for him.

But she wanted to know just how long she should take to come up with an apology.

“I have no right to tell you how to handle your personal affairs,” he said, and for a moment, he sounded like her king, gracefully holding himself to the limits of his power.

She scowled at him.

“No right,” he repeated. “And if you want to - to never make another statue of him and run off to join the choir in Alqualonde, I will be the last to tell you otherwise.”

“But?”

“But if you came back and told me you wished to remarry, I think I would offer you the crown of the Noldor not to,” he admitted. “As much as he would laugh to hear one of my mother’s children speak against it. Right now it is only the verdict of the Valar that he may never return, and the Valar have changed their minds before. If we should lock that door forever . . . “

It was probably immaterial anyway. The Valar had needed Miriel’s permission to allow Finwe’s remarriage; Feanaro, surely, would not give it.

Surely. Surely she still meant more to him than that.

She did not wish to bare that corner of her soul tonight, not even to Arafinwe. Instead, she confessed to an easier thing.

“When I was pregnant with the twins,” she said, staring at the ceiling, “it was - difficult. More difficult than any of the other births had been. I had half lost myself by the end.”

“I remember,” he said softly.

That surprised her; she did not remember him from then at all, but she supposed that only supported her point. “I was convinced I was going to die, and I was in no state to think clearly about it. I swore to him over and over that I would come back, that the very moment Namo allowed it I would come back, that he would not need to be patient long.”

Some irrational part of her had been terrified that they would lie to him; that they would say she had refused the call of life while she was desperately pounding on Mandos’s walls.

When she had been saner, she had known the fearful fancies for what they were. But in the midst of them . . .

“He kept promising that I wasn’t going to die, of course.” And he had been right about that, though it was the only one of their arguments that she would concede now. “But when that didn’t settle me, he told me that he believed me, and that if it took me a hundred thousand years to return, he would believe me still and wait.”

She had never doubted that promise. Even when they had burned everything else between them, she had believed that promise. In their worst moments, it had been because she was sure he would never concede any ground whatsoever to Indis’s marriage, but she had still believed it.

She hadn’t returned the promise. She hadn’t thought she would need to.

But now here she was, still standing, and the Valar promising that he would never, ever return.

It was not yet a hundred thousand years.

And when it had been, she would keep his promise in his stead and still wait.

#silmarillion#fic#nerdanel#finarfin#earwen#nerdanel is not perfect#nerdanel is not happy with feanor#but she hasn't given up on him#part of a prequel to Memento Pugna but can stand alone

236 notes

·

View notes

Text

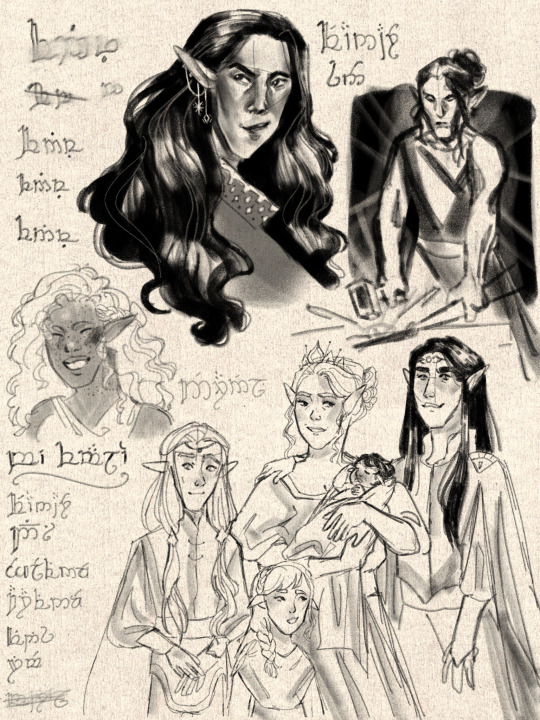

Here’s my artwork for @silmarillionepistolary day 4, love and creation!

More time has passed, and Finwë still loves his art, his people, and his growing family. His eldest son, Fëanáro (shown on the top left and right), has grown into an ambitious and genius adult. He is always creating and inventing new things - even a written language! Finwë has spent much time learning the script (a few failed attempts are shown in the top left corner), but he is immensely proud of his son (and his wife, Nerdanel, pictured below him).

Finwë’s ‘other family’, so called by Fëanáro (who doesn’t get along with them at all), has grown over the last several years. Indis is a ray of sunshine in his life, and as strong a woman as she is a Queen - she has borne four children and remains as joyful and sturdy as ever. Nolofinwë is the eldest, followed by Arafinwë, then his two daughters Findis and Írimë. Finwë adores children, and would love to always have them near him forever. (Though his own are swiftly growing up, Nerdanel is already pregnant with her first child, which is very excited about).

Still, though his first wife makes no more appearances in his sketches … she always lingers in the back of his mind, a phantom he could not erase even if he wanted to. And he doesn’t want to, no matter how much guilt he feels about pining over Míriel when his living wife is ever beside him.

Tengwar translations (the language is English transcribed into Tengwar):

#lord of the rings#art#my art#the silmarillion#finwe's sketchbook#finwe#house of finwe#silmarillion epistolary#indis#Fëanorian#nerd#fingolfin#finarfin#findis#irime lalwen#fandom event

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wanted to try my hand at some prop design so here's a collection of Maedhros's few possessions that made it past the end of the first age. So, there's his comb in the top left, i like to think that it was given to him by Nerdanel, and that maglor is the one who kept it, along with the cloak pins. Then there's his earring, i think that that one stays in the ruins of himring until the second song of arda. The hunting knife, he gave to Elros, and it sank with numenor. The book is a painstakingly preserved collection of letters from his brothers and fingon, that was likely delivered to Elrond by one of the last of mae's followers after his death, and the firefly is a nightlight that he made for baby gil-galad that followed him to sirion and well into the second age, though it's origins and maker weren't remembered by anyone.

#silamrillion#art#maedhros#as close to archeology as i can get with these long lived bastards#first age#feanorians#tolkien

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

revenant

maedhros & nerdanel | t | ao3

The first sound he remembers is a woman’s voice. It is soft—there is sadness in it, at first, before it is overshadowed by an artist’s precision, sentiment giving way to craft.

“Yes,” she says, “quite right, for the shade of his hair; only it has been finer, and curled less. He was not quite so tall—his memory betrays you there. I would have him brought down perhaps half an inch. His eyes—”

The first touch he remembers is a calloused hand on the side of his face, a caress along his cheek. Fingers gently pulling back his eyelid. A glimpse of a marbled ceiling, columns decorated with sculpted stone flowers, all white. He can feel her lean over him. Can see her hair. Fine and brown, very slightly curled. Almost red.

“The shape is right,” she says, “and the eyelashes. But I do not remember them so pale.”

The first scent he remembers is hyacinths, and then rock dust. Wind tickles his skin. He turns his head and sees her, bending over him. Her face is unwrinkled, her lips pale, cheeks a little pudgy, eyebrows and eyelashes a chestnut brown.

“Are you awake, Maitimo?” she asks.

He nods.

Some cloud flits over her features at that, some grief, some doubt. Old hurts hang in the air between them. Then she quashes it. Speaks, now, to him. “Say something.”

“Something,” he echoes.

She smiles. Her voice carries the same dispassionate notes of a craftsman. “He would answer me so,” she says, “yes, quite right on the sense of humor. But his voice had not been so raspy.”

He swallows. Reaches to feel at his own throat. “I smoke,” he says, “it’s a bad habit.”

The woman turns away from him. He cannot see whom she speaks to. “I do not remember him smoking,” she says.

They change his height, and the texture and curl of his hair, and the glint of his eye. But itch for tobacco never leaves him.

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

The woman is his mother. It is not usual, he is told, that she had been there at his rebirth. But he had not been able himself to speak for any adjustments that need be made to his body, for he does not remember what it had been like before

He walks with her through the white city, made of marble clean as bone. Low domed cathedrals, tall gleaming towers—statues, all white, of elves and not-elves. Here is one of an elvish woman hewing stone; here is another, of a star-crowned king. The inhabitants of the city are a stark contrast to the buildings, dressed in silks so bright in color they seem to be distilled light. To his eyes there is something a little comical to them.

A child’s drawing, he thinks. The background left untended to, but the principal characters colored in.

(It swims before his vision then, briefly; dark inch lines drawn onto parchment, sketches of lairs and fortresses, filled in by a child’s hand with cheerful watercolor. He leans towards the memory, but cannot touch it.)

“You made me too tall,” he tells his mother, half-laughing, “look, no one is as tall as I am. Everyone is staring.”

“None of that,” she tells him, “you are just how you were meant to be, Maitimo.”

He does not feel made-right, made-well. He feels huge, ungainly, his limbs too long and his shoulders too wide.

They walk along the dirt road. Grass begins to cover it, here and there. Plainly horses and carts rarely come this way; only single sets of footprints, so light they barely leave behind a path.

His mother’s house is carved out of the side side of a hill some ways away from the city. One big room in the center, tall domed ceiling, skylight carved into the very top of it, where the peak of the hill must be. Under that light there is a block of white marble, chipped in four places but indistinct. A chisel lays atop it.

Little coal-stove, in the corner. Scattered dishes, clean but disorderly. Half loaf of bread and a little jam, black currant. Hard cheese.

One wall unfinished. Three walls of wood, and one of dirt.

Seven chests in the corner by the dirt wall, stacked atop each other. Seals on the latches of the chests, like eight-pointed stars with one point broken off.

Two rooms branching off, dug-out and reinforced with oak-wood. They are dark, and he cannot tell what they are without stepping inside.

“This is yours,” his mother tells him, of the right. He hesitates a moment, then goes. Sees the bed in the corner, wide and soft, hanging tapestries. There are four robes for him, in same bright silks everyone else had worn. Green as the first leaves of spring. Lilac, shimmering slightly even in the darkness. Bright, pretty coral-pink, decorated with embroidered leaves in yellow and purple, slightly raised and pleasant to the touch. Sky-blue, with patchwork clouds.

“They were yours once,” his mother tells him. “Long ago.”

His own robes, he notices, are a mottled grey. The color of a spider-web, he thinks, of dust. “How long?” he asks.

His mother shuts her eyes, as though counting. “Seven thousand years.”

He has some vague notion that in the damp clothes spoil, especially in so long a time. That moths eat holes in sleeves. That seams come apart. But when he asks she looks at him oddly.

“Nothing spoils, here,” she says, “do not be silly.”

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

They eat. There is one chair at the wooden table in the corner, so his mother brings a stool from the workshop to sit on. The jam is sweet and sour, just how he likes it. The bread is perfectly soft.

“Why do I not remember this?” he asks, pulling at the sleeve of his new, blue robe. “Why do I not remember you?”

His mother hesitates.

“You burned,” she says, “you burned and there was not enough left of you to put such memories together. You’re right handed, dear.”

He switches his knife to his right hand.

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

She leaves him to rest and to gather himself. He wishes for smoke. Walks around the perimeter of the bedroom she’s given him and looks over every item.

A writing desk, prettily carved from dark oak, scratched with use. Pleasant, beneath his fingers. Familiar. Atop it—

A crystal ball, cold and heavy in his hand. A little light trapped within it, iridescent purple-red. He brings it up to his face and blows hot breath onto its surface. Sees age-old fingerprints on the smooth surface, there and then gone again.

Parchment, most of it blank. A few notes, scattered here or there on the papers, in beautiful, looping script, though he can make no sense of them. A snatch of a poem, rhyming turning eyes with burning skies, a note to procure radish-seed. Starred, and underlined—write to Elemmíre, Káno cannot play at the lilac-bloom festival—exile. A half-written apology, unaddressed, for a slight he cannot even begin to guess at.

He picks up the quill, and dips it into the inkwell. Feels scratch of the parchment under his touch as he writes:

Káno cannot play. Káno cannot play. Káno cannot play.

Three lines, neatly underneath the first. His hand is nothing like the hand of the first writer, his letters sharp and distinct and lonely where they ought to touch, ought to loop, ought to overlap. Maybe this is his mother’s writing, he thinks.

Though she had not seemed one for poetry, nor for ambling, awkward apologies.

Shelves. Books on history, on poetry. He runs his fingers along the spines and knows he has read them—can summon even the memories of the opening stanzas and chapter-headings. How odd, to remember these but not his mother. A flute, silver and black. Candles.

The bed is certainly his, for it is over-long. There is one blanket on it, a light thing of shimmering purple silk, and—he laughs to see it, then thinks he might weep—a little stuffed lamb, with cotton sewn onto its back to make fluff. He lifts it to his face, and breathes deeply.

It smells of sleep, of rose-soap, of tears. Its name dances somewhere just out of reach. It is not mine, he thinks, I gave it to…

But he cannot finish the thought. He sits, holding the little sheep in his lap. His fingers twitch.

Káno cannot play. Káno cannot play. Káno cannot play.

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

He does not mean to sleep. He is not sure he does, truly. Only that he is waking. With his left hand he is holding the little sheep to his chest. His right hand is bound, above his head. His shoulders are stiff and ache.

He sinks his fingers spasmodically into the lamb’s fur. Shakes.

Yanks his hand down, expecting to feel the chain bite at his wrist. There is nothing, because his hand is gone, because—

Because.

Sits. Stares at two hands, clenched around the stuffed lamb. Too tight. Strangling it, poor thing. Poor thing.

He breathes in deeply, smelling again the rose-soap, the tears. Outgrew it, he thinks. Gave it away, gave it to—

There is a longing in his chest, like half of him missing. The burned half, he thinks. He shuts his eyes and tries to picture it, but nothing comes. Somewhere in the other room he can hear a faint clinking, a shuffling, steps. An image swims in his mind, an elf; dark-eyed, dark-braided, pouring liquor, mixing herbs and honey.

For some while he lies and holds the lamb, listening to the movements outside. Then the soft light of the crystal ball becomes oppressive, and he rolls out of bed. Feels the cool wooden floor under his feet. Slips outside.

If he is disappointed to see his mother in the main room, standing by the little oak table and mixing tea, he knows better than to show it.

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

They breakfast outside. Pomegranate, a day past ripe and a little soft with it. Honey. Crumbling cottage cheese.

He notices for the first time how far they are from the city through which they had passed. There is a dirt road, half-covered in grass and little-tread. No one passes by them.

In the light of day he can see how their blood runs together. The sun freckles them the same. Bleaches his mother’s hair into a shade resembling his. He sees the square angles of his body in her big, calloused hands, in the set of her shoulders. But that is to be expected, he supposes. She made him. Shaped him, out of whatever he had been before this.

He expects she might speak of who he had been, but she does not. She sits and eats, sits and watches him. He cannot think of something to say, and follows her example.

“You want something to do,” she says, as they stack their plates.

“Yes,” he says. In that she knows him. Already he feels too idle, too stagnant, caught without a purpose.

She takes his plates. She gives him a shovel. A hammer. A chisel. She brings him back inside, and bids him dig.

“Here?” he asks, running his fingers over the dirt wall.

“Yes,” she says, “there is a lot of work to do, Maitimo. We will have a hall, and five more rooms. The hill ought fit them.”

He drives his spade into the dirt. Mostly clay, he thinks. It’ll hold well.

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

They work in shifts; first he digs and his mother takes the pile of dirt and carries it out. Then she digs, and he lugs dirt.

After some time his shoulders begin to ache, new muscles responding to unfamiliar work. It is a pleasant ache, the shape of it familiar. It is almost odder, he thinks, for his back not to hurt.

The work is mediative. They do not talk during it, beyond the exchanges necessary to the work—“give me that” and “rock, I think,” and “steer leftwards.”

When the sun falls pink-orange through the skylight they cease their work. She hands him a broom to sweep the last of the dirt off the wooden floor. Gathers up the spade and the chisel, and washes them.

They walk together out of the hill, and bathe in the river. The water is warm. When it sprays out onto his face he opens his lips and tastes it, almost sweet with its clarity. When he dives it whips his braid around his face.

They return.

She goes to ship at the square of marble. He goes to his room. Shoves down the ever-present craving for tobacco. Sits at the desk. Reads by the light of the crystal ball, old books of poetry.

He is not surprised he knows every line.

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

Neither of them sleeps. In the morning they resume they work again, digging the tunnel. He starts to leave the door open, when he goes to empty the pile of dirt, knowing he shall return to it soon. She closes it, each time. He does not ask why.

The rhythmic movement of the shovel becomes second nature. Around it all thoughts cease. All that is left is the motion, the sound, the heft. He does not notice at first he is putting words to it.

Thumpthump. Thump-thump. Thumpthump.

Káno can-not play. Káno can-not play. Káno can-not play.

It is odd. He has read better poetry.

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

On the fourth night he sleeps again, and dreams of the scent of burning tree-sap and screams, of dark soot staining his hands, of a woman that falls and screams, and screams, and screams. Wakes clutching the lamb to him and calls out for a name he cannot recall again.

For breakfast she poaches eggs. Cracks them each onto upturned plates with suns painted on. Swirls the water around the pot to as twisters turned inside out. Clink of the teaspoon against the black edge of the pot. Then the eggs go on, one by one, and turn around.

“Your father used to do this,” she says, “I never cooked. Only the bread.”

He holds out a hand. “Let me,” he says, and she steps aside. He picks up the spoon. Swirls eggs.

“Good eggs,” she says later, when they sit and breakfast on the grass.

He tears off a chunk of his bread-crust with his teeth. Chews. “Good bread,” he says.

The patterns of leaves dance over her arm. Shadows, in the sun.

“Right hand, Maitimo,” she reminds him.

He moves his fork. Takes a bite of egg, and feels the yolk on his tongue. “Are you angry with me?”

“I do not mean to be,” she says, which is answer enough. She must see it on his face, because she puts down her fork and looks at him. “It was all very long ago.”

He nods.

She reaches over to lay a hand on the side of his face. She has not touched him, since the first day, and now she strokes his cheekbone. “I wanted you,” she says, “I begged for you.”

He shuts his eyes. There is soot on his hands. The ocean is angry, horribly angry with him. “Did I burn,” he says, “aboard a ship?”

She stares at him.

“I cannot say,” she says. Then, more forcefully: “my Maitimo might have, I think.”

He leans into her touch. It does not last long.

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

He expects the summer to pass, but it never does. The sun rises at the same time each day, and does not go down for a long time time. They eat sliced peaches and flaky pastries and spinach-wraps and perfect fall apples, goat milk and sour bread, carrot stew, eggs made in a startling variety of ways, candied flowers. He learns where the food comes from; once every twelve days a young elven girl comes, carrying covered baskets on her head, and his mother takes them from her and tucks them into the dug-out place beneath the hill, where the earth and the ground-water keep them cool.

(He wonders why it matters. Nothings seems to spoil here. She could leave them in the heat, he thinks, and they would be fine.)

Sometimes the girl brings them letters. Some seem formal, rolled into official-looking tubes and sealed with wax. Others are clearly hastily written, scrawled on one scrap of parchment or another, sometimes with sketches on the back.

Usually she will open them at the table, and name the relation who had written to her but not the contents. “My sister in law,” she will say, or sometimes, “my father,” or, once or twice, “your cousins.” Sometimes it is a patron in Tirion that writes.

One morning a letter arrives sealed with dark blue wax, an address scrawled along the edge she reads but does not voice aloud. She tucks it into her inside pocket and does not speak its sender, ignoring his curious eyes.

They dig.

As they go further they must pull up more and more rocks, must navigate around sandy areas that fall when touched. His shoulders no longer ache with the work. Indeed he grows so used to it that it is odd not to do it, that it begins to pull at him to spend time idle.

During the nights she chisels away at the marble slab, working by moonlight, and he reads, or else goes to swim in the river. At first she is wary to let him go alone, but after the third time he returns unwavering at dawn she stops tracking him.

The marble begins to take shape. An animal, he thinks. A four-legged thing, bent low to the ground.

“Did you make the statues in the white city?” he asks her. It is night, then, or perhaps the first note of morning. The moonlight is gone. He has stopped reading, but she has not finished her carving.

“Only the good ones,” she says, half-laughing. It is not a joke.

He picks up the pan. Stokes the fire, to make breakfast. Picks up the knife, unthinking, with his right hand. In the faint light his own hand is pale as marble. Carefully carved.

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

After some time he begins to call the little lamb Káno. The odd nights when he comes to sleep he holds it to his chest. Through his nightmares the scent of rose soap never fades from its cotton sewn fur, and he begins to tell reality apart by it.

There are the snatches of his dreams, the screams, the song, the slow grinding of war-axes and the rattling of fortress doors. There is the icy forest, the kind that doesn’t truly exist in real life because winter does not exist, and snow does not exist, and one does not dash madly between ice-covered pines chasing the prints of bare-footed children. Then there is the smell of rose soap, and the softness of the cotton under his cheek.

(Sometimes he thinks Káno is in the next room, clinking around, humming under his breath. But that is an odd thought, because Káno is a stuffed lamb.)

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

“We are done digging, for now,” she says. The state of done digging should naturally follow the state of digging, but he has somehow failed to realize it is possible. But there it is, the tunnel. Five rooms branching off. “We must now go for wood.”

She gives him an axe. He looks down at it, and sees the dusting of red clay on the head first as blood, then as rust.

(Nothing rusts, he reminds himself. Rust is an idea in his mind with no real-world equivalent, like rot and ice and decapitation.)

They walk together along the overgrown dirt road, pulling an ass-drawn cart behind them. Not towards the city, this time, but away from it. The path fades, and fades, and fades, until there is nothing left but her intuition.

The wood is ancient, and untouched, pines tall and dark, their trunks many times the width of their shoulders. He reaches out and lays his hands on the bark, feeling its dark, deep ridges.

“The tree will bleed,” he says, “when we cut it down.”

“Yes,” she says, “so it will.”

She takes his hand, and draws it up to touch the deep green needles on a lower branch. When she begins to pray he knows the words, and echoes her. Together they ask for leave from Yavanna; together they promise to take no more than their due, and to pry the seeds from the pinecones of the fallen tree and plant them.

Then she makes the mark, and he begins to chop.

Some part of him expects soft yielding flesh under the axe-swing, expects gore, expects blood spray over his upturned face. Instead his axe hits hard wood, and only yellowish pine sap springs up around the cut.

It is long work, to reduce a living thing into material. First the tree must fall. Then it is cut again, to be rid of the thin branches for which they have no use; then again, to fit on the cart. Then they collect pinecones and twist them open, shake the seeds out and bury them in the dark soil, beneath the layers of dry pine-needles. Carry water from the river to drown them.

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

It is dark when they make their return. His body aches in new ways with new work. Pine-sap clings sticky to his hands, his green robes. He wants to chase the dew gathering in his lungs away with smoke.

“The river,” his mother says, and he nods. But the water cannot wash the sap from him, and he goes to bed with his hands still stained.

He will not touch the stuffed lamb, except with the back of his wrist, to knock it from the bed. It stares at him plaintively from the floor, and he pities it.

“I am sorry, Káno,” he says, “but if I touch you you will be ruined. You are made of soft things, and shall not be washed clean.”

In his dreams there is a little boy, bright eyed and loud. He plays the flute, the same silver flute on the shelves, and laughs, high and bird-like, twirls in pretty mother-of-pearl court robes. When he reaches out to touch this child he sees his hands are covered in blood, that he has stained everything; the boy and the flute and the mother-of-pearl, and nothing is merry.

Then he stirs, half-wakes. Slips back down into his dreams. Now there is a figure above him, amber-eyed, more fair than any elf he can remember laying his eyes on. He has an axe in his hand, stained with red clay, and he raises it and hews off his right hand.

Oh, he says, unbothered, well, don't worry about it. I've still got my left.

But tree-sap keeps pouring out of the cut on his wrist, spewing in messy, sticky arcs, staining the other elf’s gold-beaded hair and his cheeks and his lips and his eyelashes, and he will drown, he will drown.

When he wakes there is no smell of rose-soap to cling to. He curls up on himself and thinks he must have come from a different world, a worse world; that he is a stained and broken thing forced into a clean body. He does not belong here, he knows.

He wonders what it would be, to go back. Wonders if he’s scared of it.

Then he slips outside, and bids his mother good morning, and sits trying to clean his hands. Chops spinach into fine little slivers; beats it with cheese and with eggs, pours it into the pan to cook. Watches the edges crisp up, fine bubbles forming on the surface.

His mother stirs sugar into tea. He misses someone so fiercely he feels his chest a hollow, empty thing. They slip outside to breakfast. The sun greets them, cheerful and warm.

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

They chop the wood into boards, long to accommodate the hallway, wide. His mother has a better hand for it, at first, but he is quick to learn. The first days they speak of nothing but craft.

When they sit polishing the wood the sap has nearly come off his hands. Perhaps he has grown new skin, and the sap has flaked off with the old.

“Who will live there,” he says, “in the new rooms?”

She looks up at him. Her sleeves are hiked up, the board in front of her gleaming bright in the sun. “Your brothers.”

He has thought so, though he could not have voiced it.

“There are five,” he says, and knows it to be a question. He thinks she nods. “Who is next, after me?”

For a moment she hesitates. “Tyelkormo,” she says, “if he is granted to me.”

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

He touches the edges of the eight-pointed star on the sealed chest. The broken point. She sits behind him and reads one of her letters. He can see another still-sealed underneath, the one she had not announced to him.

I have five brothers, he thinks. I am one of six.

It does not fit. Shoes too small in the toe, pinching uncomfortably.

For the first time he can remember he feels angry, truly and properly. Kicks at the lowest of the chests, then yelps in pain at his foot. Tyelkormo, he thinks, Tyelkormo, Tyelkormo. Who can need you? Who can want you?

The woman who is not his mother looks up from her carving, but says nothing. He will tell her, he thinks, when their work is done.

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

But he breaks. The secret is too heavy on him; he cannot take it. They sit, and polish boards. It is an endless task.

“Maitimo,” the woman who is not his mother says, “hand me the sponge.”

He hands her the sponge. “I am not he,” he says, quite casually, “they brought the wrong soul back, and put it in your son’s body. I am another creature, and I think an evil one.”

“Oh,” she says, “and why is that?”

“There are evil things,” he says, “in my mind. I know not this land, but another. I dream of ice and bloodied hands and scared children.”

For some time she turns from him. He is sure she weeps. He would touch her, but it is not his right. He looks down at the board, working his brush in random patterns.

“Against the grain, Maitimo,” she says.

He turns his brush against the grain. They do not speak of it again.

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

He likes to run his hands along the polished wood. Likes to press wood-braces into the soil. Likes the neat sharpness that they give the tunnel, the way it begins to take the shape of the house.

“Did you do the same for me?” he asks, as they hang up curtain-doors.

“Yes,” she says.

“There was a different home,” he says, “where the chest is from. The bed is from. K—the lamb.”

“Yes,” she says.

For some time they work in silence. He braces the doorframe, and she hammers in the nails. Then they switch.

“What are you carving?” he asks. “I thought it a sheep.”

“No,” she says, “only an elf hiding under the wool.”

He nods. She nudges him, to step aside. There is a little window on the other side of the room, the sloping end of the hollow hill. She measures it, for a frame. Writes numbers on the inside of her arm in charcoal.

She taps him on the elbow as she passes him, beckoning him to follow. Outside they trim the wood into shapes to fit. He holds, she saws. Then she has them switch, so he may get the practice.

“I have gown too used to solitude,” she says, as they brace the corners of the window-frame with metal. “I have no words left. I thought it would be easier, to speak to you.”

He looks up. For the first he sees the weight of her own neurosis on her, the weight of her pain, her fear, her loneliness. For the first time he thinks she might touch him, if she remembered how.

“How long has it been?” he asks.

“Six thousand years,” she says. “You spend dead nearly twice the time you spent living. But I lost you sooner, of course.”

They carry the window frame inside. They fit it.

It will have a good sill, he thinks. Perhaps Tyelkormo will like to sit on it, and watch the birds.

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

It looks like a proper house, with the last of the boards fitted to the floor, to the walls. The woman who could be his mother tells him that there is not so much left to do; only to make make the bed frames and the shelves, fitted to each of them. Only to open the chests and lay out what she had saved, of them.

“Saved from what?” he asks.

She looks up at him, as though surprised he does not know. “The building was torn down,” she says, “the king’s body was inside.”

She makes a gesture with her hands, first twisted together then falling. Tower. Splat.

Do people die here, he wonders, or had the king been simply waiting to be born?

“Tyelkormo will want hounds,” she says, “on his bed frame. Likely in the house, too.”

So he sits, and whittles hounds. They turn out crooked, their noses too long. She has him try again, and that is better.

Káno cannot play, he thinks, the repetition of a song stuck in his head, Káno cannot play. Káno cannot play.

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

“I cannot tell,” he says, setting a book of insect sketches next to a fox-skull on his brother’s shelves, “if I know him.”

His maybe-mother turns to look at him. Her face is drawn.

He touches the bone. It is familiar, at least. Smooth. Oddly delicate, for what it is. In places the smooth surface has peeled off, and it is porous. He could hold it in his hands and squeeze the barest bit and watch it crumble.

“Sometimes I think I am your son,” he says, “but that something wrong has clung to me, as the tree sap has. Some other world I saw, in death, that lingers upon waking.”

She takes his hands. Holds, around the fox skull. Her fingers do not touch the bone.

“Do not leave me,” she says, “do not go there. Promise me, Maitimo.”

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

He tosses dumplings into broth, one after the other. She sits across the table from him. Her eyes follow their fall.

“I have not told you everything,” she says.

You haven’t told me anything, he thinks. But that is unjust. She has told him how to chisel stone and chop wood, how to polish floorboards, how to whittle hunting-hounds, how poach eggs.

She reaches past him, across the table. Picks up the parchment sealed with blue wax.

“I didn’t want to give you this,” she says. For a moment she holds it close to her chest, so that he cannot help but suppose the ending of the sentence will be so I won’t. Then she holds it out to him. “It is for you. You were betrothed.”

“Oh.” He reaches for the paper. He cannot tell if that seems right. If it is true of him. “Perhaps I was.”

“I am not sure,” she says, “how serious you were about it.”

An old instinct almost calls him to argue. To cry, I will, I will, after—

But after what?

He breaks the blue seal. Twirls open the paper.

The handwriting hits him with a note of such intense familiarity he cannot see the meaning of the words. His head swims.

The first time he remembers weeping is in the kitchen, holding a piece of parchment to his chest, and it is over the slopes of his lover’s letters. Behind him the fire crackles. He feels his chest cave in.

Maedhros, his lover writes, I grow tired of waiting for you to call to me. If you have gotten it into your head that it is your righteous duty to crawl into a ditch and die, speaking to none, we shall have words...

Maedhros does not make it past that opening line. He shakes with the clarity of the voice in his mind, its low, musical quality, its sardonic lilt. How well he can sense the desperation behind it. I know you, he thinks, I love you.

The woman in the room with him steps closer. She looks at the letter, but her eyes do not move to read the words.

“I never learned it,” she says, “some last defiance of your father. As though if I did not speak it it could not touch me.” There her voice breaks, her pale face flushing. "What do you think of that, Maitimo? Me lobbing one last insult at a long-dead man, and hurting myself by it?"

Of course, Maedhros thinks. It is Sindarin. He knows it, though he cannot say how. He’s thought in it, now and then, without noticing. Perhaps if he had spoken more he would have used it.

He lowers the letter, and looks at the woman who had once been his mother. In the shadows here she seems as white as marble. How odd, to think of her, all alone, beating the shape of sheep’s wool out of stone with a chisel. To think of her hollowing out the hill to make room for him. To think of her clawing him back from the dead. To think of her carving herself out of loneliness and defiance and love and anger.

Well-made, she called him.

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hmm actually as a follow-up to this post, let's rank all of the names Nerdanel gave her sons from least to most fucked up:

Makalaurë (gold cleaver). Literally fine and normal (also pretty). Probably why he ended up among the more well-adjusted of the lot.

Ambarussa (top-russet). Unimaginative, but alright.

Tyelkormo (hasty riser). Mostly ok? If, as The Shibboleth of Fëanor suggests, a reference to his quick temper, possibly a little mean but probably fine.

Carnistir (red-faced). Not exactly complimentary, but whatever.

Maitimo (well-made). Sure let's just name this kid for his looks as a deliberate fuck-you to everyone who wondered at Fëanor marrying someone "not the fairest of her people" that's going to be fine.

Atarinkë (little father). Ever wondered why this one ended up Like That? Hmm??

Umbarto (ill-fated). UM???

#silmarillion#nerdanel#the line of miriel#obviously this is mostly lh since I don't think these were necessarily out of the ordinary by elven naming standards#but in my culture they would all be so so weird so I'm side-eying them anyway

231 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who Looks Like Who(for Plot and also Angst purposes in some cases, but mostly based off vibes)

Fëanor has Míriel's expressions, her short slight frame, and her elegant nimble hands, but his colouring, his charisma, everything else comes from Finwë

Maedhros looks like Nerdanel, but with a bit of Finwë in him. You can tell from a glance that he's Nerdanel's son, equally so that he's Finwë's grandson. It's much hard to tell that he's Fëanor's son (unless he's in a temper). He has Nerdanel's level head and pragmatism combined with the Finwëan charisma, intensity and general OP-ness, all of which he inherited in spades. It's very dangerous - to others.

Maglor has Nerdanel's nose and eyes, and her vibes of quiet serenity until the breaking point and then quiet pointed fury, but also he looks like Fëanor otherwise. Especially wrt his charisma.

Celegorm looks like Míriel. He has Nerdanel's more solid frame, but otherwise could pass for Míriel's twin. Everyone who knew Míriel is always commenting on how he has her hair, her eyes, her rebelliousness, her restlesness, her temper etc. Part of the reason he spends so much time in the woods is because no one there compares him to a woman who died before he was born.

Caranthir looks like Nerdanel with dark hair, and he has her pragmatism. He does have his father's temper, but he also has A Lot of Indis' mannerisms that he has no idea where they came from Atar. (Indis is a genius with maths, economics, trade - Caranthir learnt everything from her. She isn't proud of much that anyone does in Beleriand, but she is very proud of Caranthir's trade empire.)

Curufin looks exactly like Fëanor, except when he's deep in Crafting Mode - then he looks weirdly like Nerdanel. He has Nerdanel's clear head and her insight, and Fëanor's short temper. He's cruel when he's angry, unlike his dad who rampages indiscriminately, but very much like his mum who always knows how to make it hurt.

Ambarussa are identical, with Nerdanel's colouring and frame, but Fëanor's face. Lightly toasted (or crispy or whatever) has more Fëanor vibes and raw has more Nerdanel vibes. Can't explain it, its just Like That. And also the vibes of Fëanor accidentally toasting the twin more like himself. Delicious

Findis has her mother's golden hair, her father's eyes, and an uncanny likeness to Míriel in her mannerisms that can only come from copying Fëanor. (Does this piss Fëanor off? Absolutely. Will she ever stop? Absolutely not.)

Fingolfin has his mother's eyes and her height, but just like Fëanor his colouring, his charisma, everything comes from Finwë.

Fingon did not inherit his father's height and he will never not be sore about it. He looks more like Anairë than anyone else, but his eyes are indubitably Fingolfin's. His habit of braiding ribbons in his hair comes from Findis - she tends to use bright colours but he prefers only gold.

Turgon DID inherit Fingolfin's height, and just like Fingolfin he will never let his elder brother forget it. HE looks a lot like Indis, if she had Noldorin colouring, and everyone says his more...settled temperament comes from her. It doesn't - Indis is calm and controlled, Turgon has his mother's resting bitch face and icy temper. Everyone just thinks he doesn't because his temper is quiet rather than explosive.

Aredhel also inherited Fingolfin's height. She looks like Anairë if Anairë had the Finwëan dramatic tendencies and charisma. Her idols are Cousin Celegorm and Aunt Lalwen (in that order) and it shows.

Argon is taller than Aredhel. By like...a hair. When he discovers that, it becomes his entire personality for a good week. He is the only one who looks mostly like Fingolfin, but he has Anairë's quiet, deadly iciness rather than the Finwëan over the topness.

Finarfin has his mother's colouring and her calm facade, but in all else he is Finwë writ blond. He also hides a temper under the calm facade, but because he controls it better everyone assumes his dad's temper passed him by.

Finrod has the Telerin chill/friendly factor mixed with the Noldorin dramatic intensity, which leaves him aggressively and pointedly friendly. He looks like his mum if Eärwen were blonde and constantly wore as much jewellery as Fëanor made in a particularly inspired month.

Orodreth got Indis' calm facade, and the Finwëan drama gene skipped him for which he is eternally thankful. He has Eärwen's colouring, and Finwë's bone structure, but everything is softer with Orodreth. He's just very shy and quiet and adorable.

Angrod looks very much like his dad, if his dad had blue eyes. He also got Indis' calm facade, but the difference between him and Orodreth is that for Angrod it is just a facade. He's got stubborness in spades from Finwë, and a backbone of mithril from his mum. She also gave him a healthy dose of common sense. Oh and he got a bunch of mannerisms off Findis that really annoy his uncle Fëanor.

Aegnor...well. People make jokes that he's Fëanor but blond. He's got the charisma, the intensity, the impulsiveness, the propensity for bad life choices, the list goes on. Thankfully, he also has Angrod to keep him from anything too awful.

Galadriel has Indis' height, her strength, her colouring and beauty, and a temper that wouldn't look out of place on Fëanor himself. She also has her mother's competency (which comes from the same place as Lúthien's ability to take down the two biggest bads without breaking a sweat). It's a rather dangerous combination.

Lalwen is...herself. She's got her mother's height, her father's charisma and his colouring, but mostly she's just Lalwen. Bold and laughing and utterly done with her family's drama.

#feanor#nerdanel#maedhros#maglor#caranthir#curufin#celegorm#amrod and amras#ambarussa#fingolfin#anairë#fingon#turgon#aredhel#nolofinweans#feanorians#finarfin#earwen#finrod#orodreth#angrod#aegnor#galadriel#arafinweans#finwe#finweans#house of finwe#miriel#Indis#silmarillion

219 notes

·

View notes

Text

"She also was firm of will, but she was slower and more patient than Fëanor, desiring to understand minds rather than to master them. When in company with others she would often sit still listening to their words, and watching their gestures and the movements of their faces. Her mood she bequeathed in part to some of her sons , but not to all. Seven sons she bore to Fëanor, and it is not recorded in the histories of old that any others of the Eldar had so many children. With her wisdom at first she restrained Fëanor when the fire of his heart burned too hot; but his later deeds grieved her and they became estranged."

- J.R.R. Tolkien, Morgoth's Ring, "The Later Quenta Silmarillion (II): Of Fëanor and the Unchaining of Melkor"

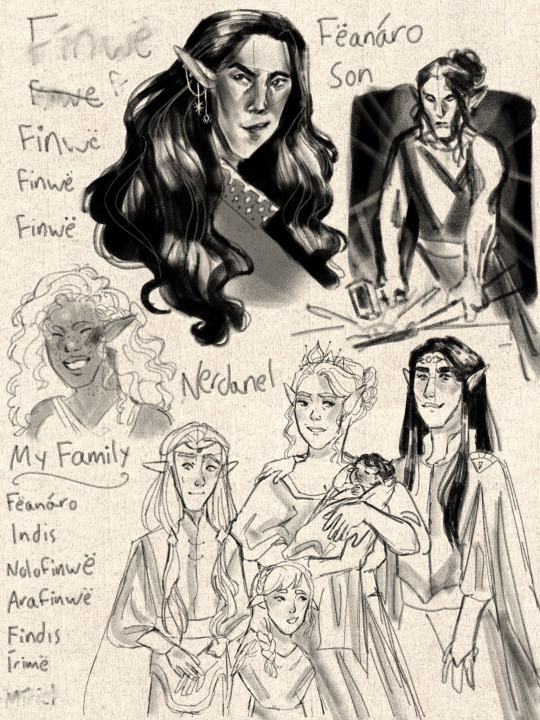

@tolkienofcolourweek || day 2: elves + journeys || nerdanel the wise

[ID: an edit comprised of four posters in brown and rusty red with some grey and white accents.

1: Rayan El-Mahmoud, a lebanese-ghanaian model with light brown skin, freckles, and coily reddish hair. She is in front of some rocks, leaning her head on one hand while looking towards the viewer, and is wearing a strapless white dress. The image points down from the top of the poster and is framed in orangey-red and white on a brown background. Text underneath reads "nerdanel" in a large red font and a very small cursive one in white / 2: A craggy mountain surrounded by scree. Text in the same colors as the frame from Image 1 reads "In her youth she loved to wander far from the dwellings of the Noldor; either beside the long shores of the Sea or in the hills;" / 3: Brownish-orange hills with a river running down through them. Text in the same format as Image 2 reads "and thus she and Fëanor had met and were companions in many journeys." / 4: Rayan El-Mahmoud, this time standing leaning against the rocks and looking up at the viewer. The colors and positioning of the smaller image are reversed, as are the colors of the text /End ID]

#edits with the wild hunt#brought to you by me#tocweek2023#nerdanel#the silmarillion#mepoc#described#posters#silmedit#tolkienedit#tolkiensource#elvensource#oneringnet#fc: rayan el-mahmoud#elves elves elves

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nerdanel headcanons

She’s short for an Elf. Like Tiny.

Freckles EVERYWHERE

Chubby Nerdanel! No one can stay lean and fit after 6 pregnancies and our girl handles heavy stones on a daily basis. She’s chonky.

She never gets angry but instead will give you a Disappointed Look(tm) that is even worse (Maitimo gets it from her and uses it shamelessly with his brothers). The rare times she really gets angry it’s at Fëanor and everyone in a mile radius can hear her scream.

Short haired Nerdanel! She doesn’t have time to care for her hair.

Nerdanel’s called the Wise and gives genuinely good advice but in an incredibly blunt way, usually using a fuckton of swearwords.

She was the one to ask Fëanor out bc he was too tongue tied and blushing whenever around her to do it himself

She has no patience for court bullshit and etiquette

As a child she sometimes sat on Aulë’s knees and braided trinkets in his beard, using bigger and weirder things each time until he noticed

Once called Aulë grandpa as a toddler and he never let her forget

She genuinely thinks she gave good names to her sons. No one can change her mind.

Incredibly stubborn when she puts her mind to it.

She wears old tunics belonging to her father as work clothes, and then ones from Fëanor after their marriage. She has to cut the sleeves and the tunics fall well past her knees (Fëanor finds this incredibly hot)

She has a very good singing voice though she prefers bawdy drinking songs to refined opera. Makalaurë asked her to perform some of his first compositions at court and it’s the only time Nerdanel sang in public

She made the first tunic for each of her sons despite hating sewing. After they left, she keeps the tunics in the top drawer of her dresser.

38 notes

·

View notes

Note

Christmas Beleria Prompt:

Curufin with young Celebrimbor and Celebrimbor's mother, his ex.

Cancelled flight & Bittersweet memories

🥰

Thank you for the prompt! This one is a tad sad. It's a ten-year-old with separated parents, what can I say? ~800 words, rated G.

Posting these to AO3, here. Prompt list.

On the airport intercom, the garbled speech of the announcer repeated the message: flight number 472 to Valin, delayed, weather conditions, thankyouforyourpatience.

Oh well. Celebrimbor liked the airport: he liked watching the planes take-off and land, and telling Dad the things he’d learned about on TikTok from @airplanefactswithmax — like the fact the Boeing 767 they’d be taking across Belegaer to Valin tonight had a cruising speed of 850 kilometres an hour and had two engines with sixty-three thousand pounds of thrust each.

And, because their flight to Valin would be nine hours and forty minutes, that also meant they’d be served dinner, breakfast, and snacks. And, since Grandpa bought them Business Class tickets as a Yule present, Celebrimbor could order as many free root beers as he wanted while Dad slept.

The flight was delayed, though, and he was hungry. He eyed the wall of snacks in the airport shop. Lembas Munch Mix or Juicy Sweets? He looked at his dad’s credit card in his hand and back at the wall. Dad was tired: he probably wouldn’t mind if he got both. Celebrimbor grabbed a bag of the Juicy Sweets. Although he was the second-tallest kid in his class, he still had to stand on his tiptoes to reach the Lembas Munch Mix on the top row.

He plopped them down on the counter, avoiding eye contact with the cashier, and tapped the credit card on the machine.

“Thank you,” he said, and, "You too," when the cashier told him to have a good flight, then winced as he turned away, feeling foolish: she wasn't flying anywhere.

On the way back to the gate, he ripped the bag of Juicy Sweets open, sifting through for a red one: his favourite flavour. He also picked out a green one, which was Dad’s favourite.

Dad was on the phone when he got back, so he sat himself down quietly and munched on the gummies while he listened.

“I know. I know. Well, we can’t really do anything about it, can we? It’s cancelled, that’s that.”

What? Celebrimbor perked up. Cancelled?

“No, I’m not going to book another flight. They'll re-book us for end of December. It’s just a day, Alwen!”

He was talking to Mom.

“Yes, yes — I know it was your year.” Dad glanced at Celebrimbor with a guilty look. Celebrimbor offered him the open bag of Juicy Sweets, and he grabbed a handful and popped the whole thing in his mouth at once.

“You know,” he said around his mouthful (like he told Celebrimbor not to do), “his whole family is here now, you could always come here.”

There was shrill chattering on the other end of the line and Dad drew the phone away from his ear, grimacing.

“Fine, yes,” he said when it was over. “Yes, I know your parents— No, I hear you, Alwen. But we’re not booking another flight. We’ll come at the end of the month. Yes. No. There’s nothing to discuss!”

Dad clenched his fist on the armrest. Talking to Mom always made him angry. Celebrimbor knew they didn’t love each other, they’d told him as much. They’d thought they were in love when they were eighteen, but eighteen-year-olds couldn’t possibly know they were in love — even though Grandpa Fëanor had met Grandma Nerdanel when they were nineteen; but Uncle Cáno had met his husband when they were sixteen, and now they were divorced and didn’t talk at all, so maybe his grandparents were an exception.

Celebrimbor wondered if Mom and Dad would talk if it wasn’t for him. Probably not. (They never told him that he was an accident, but he’d figured it out when he was eight.)

“Have a good day, Alwen,” said Dad. He didn’t sound like he wanted her to have a good day. “Yes. I’m tired, you’re tired, we’ll talk again tomorrow. Goodbye.”

He hung up and sighed loudly.

“So we’re not going?” Celebrimbor asked.

“No,” Dad said, taking another gummy from the bag. “We’re not going. They cancelled the flight.” He patted Celebrimbor’s shoulder. “Sorry, Tyelps. We’ll go for New Year’s, hey?”

“Yeah, okay,” Celebrimbor said, quashing the swoop of disappointment rising from his belly. He loved Dad and all his uncles and his grandparents and his friends at school. He loved his not-actually-uncle Uncle Finrod, too. He’d never want to live with Mom in Valin, but he did like their visits every other year. They always made ornaments with dried oranges and string, and baked a gingerbread castle from scratch.

“Hey, Dad,” said Celebrimbor, “you wanna make a gingerbread house?”

Dad yawned, but it turned into a smile. “Yeah, sure. We’ll do that tomorrow.”

“And maybe we can send Mom some handmade ornaments?”

“Good idea. She’ll like that.” He took Celebrimbor's hand and gave it a squeeze. "How'd I have such a nice kid?"

Celebrimbor shrugged. "I dunno. Lucky?"

Dad opened his mouth, pretending offense, and Celebrimbor grinned and laughed.

[@airplanefactswithmax is hilarious and fandom-appropriate, if you haven't seen it. I got those facts from an airline website though, not his videos.]

#celebrimbor#curufin#curufin's wife#well... celebrimbor's mom anyway#holiday prompts#modern au#my fic

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Forgiveness, can you imagine?

[ID: Digital painting of Fëanor and Nerdanel in profile. Nerdanel, a light-skinned female elf with long red hair, is leaning her chin on the top of Fëanor's head, who is a very light-skinned male elf with long black hair. Fëanor has extensive scarring on the side of his face and his ear. They are both wearing earrings in the colours of the trans flag. Glowing snow or dust falls around them, and the background has indistinct dark mountains and lights.]

Reposting it without the ask so I can pin it + get it into the tags, but the prompt is here.

T4T Nerdanel and Fëanor reunited in Dagor Dagorath. I wanted to achieve a less detailed and more textured feel, and I'm pretty happy with the result!

Queer characters series | Disabled characters series

#feanor#nerdanel#silmarillion#tolkien#beautiful art#the silmarillion#feanor art#nerdanel art#echo's drawings#queer silmarillion#silm#silm art#queer tolkien characters#disabled tolkien characters

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

I dont have my copy of the Silmarillion on hand atm (shameful I know) but I have a memory of something along the lines of when Fingon went to rescue Maedhros from Thangorodrim, he sang a traveling song from his grandfather's era, one that was popular enough that both he and Mae knew the lyrics to sing back

I've been humming and hawing about what that song might be, and I have a list, but the top of the list atm is "Stay, I Pray You" from Anastasia the Musical. Its a nice minor key, when I first heard i thought it was about missing a person, would be easy to sing along in a group, has GREAT foreshadowing depending on how u use it, etc

This is a song I can see one the Noldor sang as they crossed Middle Earth West for Valinor, one Miriel sang at the loom in Valinor, mournful about the life she left behind, Feanor and Nerdanel singing the song in a more major key to their children as they traveled or as a lullaby on the road, one that Maedhros would have sang as a lullaby to his younger brothers and cousins (and to his foster sons centuries later), a theme of which could have been incorporated into the Noldolante/one that Maglor could have sung on the shorelines, and a song I can see Nolofinwe leading as his host crossed the ice, bringing the song full circle as his host leaves Valinor for Middle Earth

Fingon singing this song, something that helped him keep walking on those dark, bitterly cold nights, something that is keeping him moving as he tries to find clues of his beloved cousin. Begging, desperate, he calls:

"You are all I know

You have raised me

How to turn away?

How to close the door?

How to go where I have never gone before?"

And then he hears a voice, faint, singing back word for word, and Fingon is scrambling over rock and leaping over ledges, not caring for anything but that voice that sings along.

"How can I desert you

How to tell you why?

Coachmen, hold the horses

Stay, I pray you

Let me have a moment

Let me say goodbye"

And then he sees him, Maedhros dangling above him, starved and broken but not gone yet, the pale fire in his eyes still flickering. Fingon can do nothing but stare, enthralled as Maedhros whispers the final line, weak voice carrying in the wind.

"I'll bless my homeland till I die"

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

20 questions for fic writers

Thanks very much to @nocompromise-noregrets for the tag! This is always an interesting exercise and I haven't done it in a while.

1. How many works do you have on Ao3? 182, but a goodly subset of those are collections of very short works (drabbles, my beloveds!).

2. What’s your total Ao3 word count? 137,372. I average around 700 words per ficlet (counting those that are collections of drabbles). I have only two works over 2,000 words -- one at barely 2,100 and one at 5,600 by dint of TRSB last summer.

3. What fandoms do you write for? Tolkien only. Mostly Silmarillion but occasionally Lord of the Rings, as well.

4. What are your top five fics by kudos? I'm splitting this by fandom because the older LoTR stuff has more kudos simply as a function of time.

For LoTR: Deep in the Ancient Forests of the World; Light a Little Fire in Me; I Do Not Grudge You the Game; Rash Words and Bitter Hopes; Sing, O Stone and Air. These are all Legolas/Gimli ficlets.

For Silm: When All Other Lights Go Out (the aforementioned TRSB Feanorian family drama); What We Make, Makes Us (Caranthir and Feanor); What Keeps Us Here (Celeborn and Thranduil); Still Plenty of Good in the World (Sam Gamgee fixes Feanor and Nerdanel); and It Is the Opinion of this Reviewer (Finrod critiques the research of his peers).

No method to the madness here, it seems. Some shippy, most not. Some angsty, some humorous, mostly canon compliant. Range of Silm characters. Interesting to see the variety, actually.

5. Do you respond to comments? Always. Usually within a few days. Comments are a great way to get to know other people in the fandom, and it's always a pleasure to see familiar names pop up. It's nice to know I have a bit of a following. But I also love seeing new people appear, and I welcome everything from a single emoji to a full blown rant. I reply to them all.

6. What is the fic you wrote with the angstiest ending? Only one? Impossible to choose. I love an angsty ending. Killing Fingon off is always a delight (like this, or this). Sending people off to their dooms (like this, or this) is another. Making them consider might-have-beens, too (like this, or this, or this).

7. What’s the fic you wrote with the happiest ending? I do also like happy endings! I write many happy post-canon returns, to tie up all the loose ends. Also happy moments within canon, but you usually have to pretend you don't know what comes next (blame the Professor, not me). For LoTR, These Our Braided Lives has a very happy Gimleaf ending. For Silm, try In These Altered States, Rejoice.

8. Do you get hate on fics? Spitting over my shoulder on this one, but no. Even the people who don't agree with my takes on particular characters have always been polite. Thank you, kind readers!

9. Do you write smut? If so, what kind? I don't write anything explicit. I'll read a wide variety but am more restrained in my writing. I've snuck a little bit into the mature range for a few things recently, but I prefer allusion and metaphor, really. It's the spirit of the intimacy that interests me, not so much the mechanics.

10. Do you write crossovers? What’s the craziest one you’ve written? Nope. Canon compliant or canon adjacent always.

12. Have you ever had a fic translated? Yes, I've had a few requests. My Thranduil seems to be quite popular in other languages.

13. Have you ever co-written a fic before? I haven't but would be happy to explore the possibility.

14. What’s your all time favorite ship? Can't pick just one. Legolas/Gimli, Glorfindel/Ecthelion, Maedhros/Fingon, Finrod/Edrahil. The much rarer Egalmoth/Rog. And I'm pleased to have originated the tag for Amrod/Aredhel. Spitfire fans, get on that! (thanks to chestnut_pod for the horrible, wonderful ship name)

15. What’s a WIP you want to finish but doubt you ever will? Not a WIP, even, just an idea that I've mentioned before: an AU in which Fingon, returning from Thangorodrim with Maedhros, can't hold onto him, and he falls from the eagle's back into Lake Mithrim. I won't write it, but I sure hope someone else will.

16. What are your writing strengths? Brevity, ha! Condensing a great deal of emotional development into very few words. Figurative language. Ripping your heart out and stomping on it, tidily.

17. What are your writing weaknesses? Dialogue. I don't write much of it, and it takes a long time to get it right.

18. Thoughts on writing dialogue in another language in fic? I'm not likely to do so. I don't like the way it interrupts the flow. I'd rather indicate the language that is being spoken than try to craft compelling dialogue in it. This is especially fraught in the Tolkien fandoms, where the linguists WILL come for you if you get it wrong, lol!

19. First fandom you wrote for? LoTR. I've only been doing this for a couple of years.

20. Favourite fic you’ve written? Impossible to choose! But my comfort series is The Flower and the Fountain: 16,000 words of Glorfindel and Ecthelion in 32 vignettes. I love those guys.

Thank you so much for the tag! @polutrope @eilinelsghost @melestasflight @tathrin @thelordofgifs @zealouswerewolfcollector, what about you? And anyone else who'd like to share, hop in!

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Incomplete list of name origins/motivations of the House of Finwë, according to me (and sometimes canon). Any names not listed were given for normal “parent liked it and it fit the baby (fathername)/young child (mothername) well enough.”

Original Brady Bunch:

Finwë (epessë, "hair/crowned guy") - as discussed here

Miriel - [normal name origins]

Indis (mothername, "bride") - true maternal prophecy. “She’s going to fuck her way into trouble and, if we’re lucky, fuck her way out of it”

Fëanáro (m, "spirit of fire") - not prophecy so much as really really obvious right away

Curufinwë [I] (fathername, "clever finwë") - Finwë, proudly watching his son build cities out of blocks: “He’s like me but even more clever!”

Findis (f, [finwë+indis]) - Finwë has the naming instincts of Bella Swan and we should mock him so much more for this

Arakáno [I] (m, "high chieftain") - warning label Fingolfin was a very bossy toddler; Indis thought it was adorable and was sure he’d grow into it (he did)

Lalwen/Irimë - [both normal name origins]

Ingoldo [I] (m, "the noldo") - spite. born 2 months after Nelyafinwë due to total lack of parental coordination. Indis looked Fëanor straight in the eyes while introducing his new, distinctly blond and Vanya-looking baby brother to him. Effectiveness as a warning label is entirely accidental.

Fëanorians:

Nelyafinwë (f, "third finwë") - spite

Maitimo (m, "well-shaped") - Nerdanel: Attention, everyone! I have made the PRETTIEST BABY EVER!!;

Makalaurë (m, "golden voice") - Nerdanel, proudly: Yes, his beautiful voice is very loud [functional warning label]

Tyelkormo (m, "hasty riser") - warning label Nerdanel, loving but strained smile: My newest beloved son. Will not. Stay. Asleep. :)

Carnistir (m, "red-faced") - Nerdanel: Lookit how red his little face gets when he cries! Don’t you just want to squish it even more?!

Atarinkë (m, "little father") - Nerdanel, delighted: FËANÀRO, IT’S A BABY YOU!;

Curufinwë [II] (f, "clever finwë") - Fëanor, awed whisper: holy shit you’re right, it’s a baby me

Ambarussa & Umbarto Ambarto (m, "red-topped" & "doomed" "up-exalted") - as told in The Shibboleth of Fëanor:

Nerdanel, desperately ignoring the growing sense of true maternal prophecy: They’re both redheads!

Fëanor: Beloved, you can’t give them both the same name.

Nerdanel: Yes I can.

Fëanor: No you can’t.

Nerdanel: Yes I can.

Fëanor: No you can’t.

Nerdanel: Fine, his name is Doomed, are you happy! He’s doomed to a terrible fate! He’s going to suffer and die alone!

Fëanor: Haha you mean fated to great things, upwardly mobile, right?! Nothing has ever gone wrong when I ignore you, and probably nothing ever never will!

Ambarussa, jointly, as soon as they're old enough to speak: We like having the same name actually

also, Telúfinwë (f, "last finwë") - Fëanor: "Okay, even I think we should probably stop at 7"

Fingolfinians:

Findekáno (f, "hair[crowned] commander") - a little bit of spite ("Finwë" + "Arakáno"), but mostly Fingolfin liked how it sounded and didn't realize until it was too late that he'd just swapped the syllables in Kanafinwë, and had to pretend real fast that he didn't care

Turukáno (f, "strong chieftain") - Fingolfin decided to lean into the káno root for his kids, and he likes how this name sounds and he doesn't care that it's the same root at Turkafinwë! Not everything is about Fëanor!

Írissë (f, "[something] femine") - Fingolfin, standing on top of a roof, holding baby Aredhel up like Simba: "WE HAD A GIRL!!!" ("Ir" from Anairë)

Arakáno (m, "high chieftain") - Anairë: haha holy shit, Nolo, he's a baby you

Finarfinians:

Findaráto (f, "high/noble finwë") - Finarfin shortly before his first son is born, moving around scraps on paper on which are written root words: "Okay so it has to include 'fin' and a part of one of my names which is not 'fin' (how stupid would two 'finwë's sound in one name!), but it for the sake of individualism it shouldn't be literally my name nor, preferably, Nolofinwë's...

Ingoldo (m, "the noldo") - warning label: Eärwen, preventing her son from trying to eat his fourth very child-chokable random gem from the ground today: "Ara, he gets this from your side." (Effectiveness as a warning label for nude werewolf combat is entirely accidental.)

Angrod - [normal name origins]

Aegnor - [normal name origins]

Artanis (f, "noble lady") - Finarfin standing on the opposite roof, holding baby Galadriel up like Simba: "GIRL! GIRL! GIRL!"

Nerwen (m, "man maiden") - Men already barely understand Elvish gender, especially as filtered through the Professor. We cannot begin to conceive of what Galadriel was doing with it, nor should be be so hubristic as to try

Grandchildren, birth order according to me:

Orodreth (m, "mountain climber") - warning label: if this child is not given something to climb, he will Find Something to Climb