#or most of the goethe derivatives

Text

broke: Faustus sells his soul for power

woke: Faustus genuinely does sell his soul for knowledge

bespoke: Faustus mostly just wants Mephistopheles

#this only applies to the marlowe version tho#definitely not the goethe#or most of the goethe derivatives#although it does apply to#frau faust#doctor faustus#hot faust summer#otp: as many souls as there be stars#srsly read the contract and the way he talks about it#and compare what he actually does with access to phenomenal cosmic power#it's all about the d(emon dick)

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

CoTE opening quotes

a list of the opening quotes in classroom of the elite:

What is evil?- Whatever springs from weakness.

-F W Nietzsche, The Antichrist

It takes great talent and skill to conceal one's talent and skill.

-La Rochefoucauld, Reflections or Sentences and Moral Maxims

Man is an animal that makes bargains: no other animal does this - no dog exchanges bones with one another.

-Adam Smith, An Enquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations

We should not be upset that others hide the truth from us, when we hide it so often from ourselves.

-La Rochefoucauld, Reflections or Sentences and Moral Maxims

Hell is other people.

-Jean-Paul Sartre, No Exit

There are two kinds of lies; one concerns an accomplished fact, the other concerns a future duty.

-Jean Jacques Rousseau, Emile or on Education

Nothing is as dangerous as an ignorant friend; a wise enemy is to be preferred.

-Jean de La Fontaine, Fables

Abandon all hope, ye who enter here.

-Dante Alighieri, The Divine Comedy, Inferno

Man is condemned to be free.

-Jean-Paul Sartre, Existentialism and Humanism

Every man has in himself the most dangerous traitor of all.

-Kierkegaard, Works of Love

What people commonly call fate is their own stupidity.

-Schopenhauer, Philosophical Writings

Genius lives only one story above madness.

-Schopenhauer, Parerga and Paralipomena

Remember to keep a clear head in difficult times.

-Horace, Odes (Carmina)

There are two main human sins from which all the others derive: impatience and indolence.

-Franz Kafka, The Zurau Aphorisms

The greatest souls are capable of the greatest vices as well as of the greatest virtues.

-Rene Descartes, Discourse on Method

The material has to be created.

-Florence Nightingale, subsidiary notes (female nursing into military hospitals in peace and war)

Every failure is a step to success.

-William Whewell, Lectures on the History of Moral Philosophy in England

Adversity is the first path to truth.

-G G Byron Don Juan

To doubt everything or to believe everything are two equally convenient solutions; both dispense with the necessity of reflection.

-H Poincare, Science and Hypothesis

The wound is at her heart.

-Vergil, Aeneid

If you make a mistake and do not correct it, this is called a mistake.

-Anonymous, Analects

People, often deceived by an illusive good, desire their own ruin.

-Niccolo Machiavelli, Discourses on Livy

A man who cannot command himself will always be a slave.

-J W V Goethe, Zahme Xenien

Force without wisdom falls of its own weight.

-Horace, Odes (Carmina)

The worst enemy you can meet will always be yourself.

-F W Nietzsche, Thus spoke Zarathustra

lmk if you'd like explanations as to how these epigraphs relate to the story

#classroom of the elite#CoTe#ayanokoji#kiyotaka ayanokouji#quotes#literature quotes#deep quotes#anime#light novel#anime opening

246 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve yet to see anyone talk about this:

The verse on the matchbox being highlighted so obviously stuck out to me. Neil is clever. He did this for some reason. I looked into this a while ago but only just got round to writing it out because I’ve been sick and had the time to hyper fixate on researching something I didn’t need to…

So buckle up because Job 41 is a parallel of the minisode scene when God is talking to Job. But I think the whole of Job 41 relates heavily to Crowleys character and his storyline because it’s about a sea snake.

Full warning this post is long, but it’s all important I promise.

Disclaimer you have to read if you’re gonna comment about me being wrong in my interpretation of Job 41: I am someone who doesn’t believe it’s possible to perfectly understand the bible. I’m not presenting anything as fact because there’s looottts of different interpretations of literally everything in the bible. This is my interpretation of the chapter. I don’t care if you think I’m wrong cause you have a double degree in know it all religious studies. Disclaimer over.

So where does the verse come from?

Job 41:19

‘Out of his mouth go burning lamps, and sparks of fire leap out’

This verse is part of Gods description of a leviathan that takes up most of the second part of chapter 41 in the book of Job. If you want to read the entire chapter before reading this I’ll paste it at the bottom of the post. It’s from the King James version. You can also just google it.

But what’s a leviathan? Glad you asked. I spent to long looking it up.

Leviathans. The general consensus is that the creature referred to in Job 41 is some kind of sea monster. The Hebrew word that translates to Leviathan (Livyatan) appears six times in the Old Testament. One of them is in Job 41. The word is derived from the root Iwy or ‘ twist, coil’ and means ‘the sinuous one.’ So I think we can establish that this creature is at least indicated to be snake-like. It could be a crocodile, a whale, a dragon, a snake, or just an indescribable monster. But we have no modern reference because this creature doesn’t exist in modern times if it ever existed at all. So for the purpose of relating it to the show, I think its important to note that one of the interpretations is that the leviathan is a snake like creature or a sea serpent Iike what’s shown in this beautiful piece of art.

The Destruction of Leviathan by Gustave Doré (1865)

Now, these two verses from the first part of Job 41 are important,

Job 41:10

None is so fierce that dare stir him up: who then is able to stand before me?

Job 41:4

Will he make a covenant with thee? Will thou take him for a servent forever?

Prior to chapter 41 Job, has been questioning God about the mysteries of creation. God responds by chastising Job for questioning him and describing how Job would not be able to subdue the great leviathan and make him his servant, so why does he think he has a right to question god?

And in our minisode Job comes back from talking to god and says:

“I think the point was, if you want answers, come back when you can make a whale.”

What’s happening when Azirpahale and Crowley come across God talking to Job is exactly what’s happening in Job 41. I also noted that in the minisode Job said God talked alot about whales. Which is funny, because it seemed random at the time, but one interpretation of the ‘leviathan’ is that it’s some kind of whale.

So that scene in the minsode is based off of Job 41! Amazing. But I don’t think the connections end there…

The more obvious potential reference to Crowley in Job 41 is how God describes the leviathan being able to spit fire. The verse on the matchbox comes from this part of the chapter.

Job 41:19

Out of his mouth go burning lamps, and sparks of fire leap out

Job 41:20

Out of his nostrils goeth smoke, as out of a seething pot or caldron

Job 41:21

His breath kindleth coals, and flames goeth out of his mouth

We know Crowley has the ability to summon fire. He summoned that giant sun thing that shoots fireballs to smite goats at the start of the minisode, then he sets fire to the house before saving Job’s children. So leviathan/sea serpent spits fire, our fav snake from Eden can summon fire. Fire is also just quite central to his storyline with the bookshop fire, the road/his Bentley setting fire, Heaven trying to burn Aziraphale with fire and the bombing of the church when he saves Aziraphales books.

But there’s some less obvious connections in Job 41 to Crowley. There’sa few interesting verses here that seem to relate to Crowley

Job 41:4

Will he make a covenant with thee? wilt thou take him for a servant for ever?

God isn’t talking about killing the leviathan, he’s talking about enslaving it

Job 41:24

His heart is firm as a stone: yea, as hard as a piece of nether millstone

Nether millstones, according to my googling, are millstones obviously, but it’s also a phrase that indicates something that is tough and unyielding, unlikely to submit. It’s describing the leviathan being unyielding to negotiations. God also says this about the leviathan,

Job 41:29

Darts are counted as stubble: he laughter at the shaking of a spear

I couldn’t help but think all these verses are very Crowley sounding. He is stubborn and willfull, unable to be controlled and won’t submit to servitude. He (both actually and metaphorically) laughed in hell's face when he and Aziraphale were body doubling and the holy water didn’t destroy him.

Crowleys wilfulness and refusal to be subjugated is the reason he fell in the first place. It’s the reason he fell out with Hell as well, he refuses to fully go along with either side. He believes in autonomy and freedom. He said no to Aziraphale because he cannot return to a life he perceives as slavery, especially as Aziraphales ‘second in command’. He doesn’t want to be under anyones command or to command anyone. It’s so against his very nature to return that the suggestion was ridiculous to him. And this chapter of Job is a parallel in that God uses the leviathan as an example because it’s ridiculous to imagine a giant sea monster being enslaved by a human to do his bidding. Just like in the minisode how it’s ridiculous to tell Job to make whales before he can ask God anything.

But that’s the point. That’s the whole conflict of the show, Gods ridiculous answer to everything is that it’s ‘ineffable’ and therefore you can’t ask questions.

I also think it’s also fitting that the leviathan is perceived to be a monster that must be slain or enslaved.

And it makes me think of how Crowley has always been labelled as evil because he fell. I think of how, at heart, he is truly gentle and kind, he’s a starmaker. But his fall, his appearance, his desire to be autonomous and his grey moral campus make him feared and a target. He’s a boat rocker, he keeps asking questions even when he gets told ridiculous answers and that’s the problem for those in power. It makes me think of this quote

“Draw a monster. Why is it a monster?”

-Daughter by Janice Lee.

So in conclusion, not only is Job 41 the chapter that would’ve inspired the scene where Job is talking to god, I think Crowley represents the leviathan being discussed in Job 41.

So do I think this has any meaning/hint to season 3?

I don’t think there’s a direct hint. But it reminded me that Crowleys character is truly unrelenting. He’s a nether millstone. And he won’t give up that easily. He absolutely won’t submit to anyone, and he’s shown time and time again that his blustering about running away disappears as soon as someone or something he cares about is in danger (ie Aziraphale). And the second coming will also threaten his creation (the universe) so I’m really hoping we will see so much more of Crowleys power and history in S3.

I’m really happy I looked into this, because I could be completely off the deep end with this analysis but it actually wouldn’t even matter because this universe Terry and Neil’s created is built around it being transposable. You can put any lens you want on it. And I had fun deep diving into Job 41. I never thought I’d ever say I had fun reading the bible but Neil you did it. Sneaky buggar.

Full chapter of Job 41:

41 Canst thou draw out leviathan with an hook? or his tongue with a cord which thou lettest down?

2 Canst thou put an hook into his nose? or bore his jaw through with a thorn?

3 Will he make many supplications unto thee? will he speak soft words unto thee?

4 Will he make a covenant with thee? wilt thou take him for a servant for ever?

5 Wilt thou play with him as with a bird? or wilt thou bind him for thy maidens?

6 Shall the companions make a banquet of him? shall they part him among the merchants?

7 Canst thou fill his skin with barbed irons? or his head with fish spears?

8 Lay thine hand upon him, remember the battle, do no more.

9 Behold, the hope of him is in vain: shall not one be cast down even at the sight of him?

10 None is so fierce that dare stir him up: who then is able to stand before me?

11 Who hath prevented me, that I should repay him? whatsoever is under the whole heaven is mine.

12 I will not conceal his parts, nor his power, nor his comely proportion.

13 Who can discover the face of his garment? or who can come to him with his double bridle?

14 Who can open the doors of his face? his teeth are terrible round about.

15 His scales are his pride, shut up together as with a close seal.

16 One is so near to another, that no air can come between them.

17 They are joined one to another, they stick together, that they cannot be sundered.

18 By his neesings a light doth shine, and his eyes are like the eyelids of the morning.

19 Out of his mouth go burning lamps, and sparks of fire leap out.

20 Out of his nostrils goeth smoke, as out of a seething pot or caldron.

21 His breath kindleth coals, and a flame goeth out of his mouth.

22 In his neck remaineth strength, and sorrow is turned into joy before him.

23 The flakes of his flesh are joined together: they are firm in themselves; they cannot be moved.

24 His heart is as firm as a stone; yea, as hard as a piece of the nether millstone.

25 When he raiseth up himself, the mighty are afraid: by reason of breakings they purify themselves.

26 The sword of him that layeth at him cannot hold: the spear, the dart, nor the habergeon.

27 He esteemeth iron as straw, and brass as rotten wood.

28 The arrow cannot make him flee: slingstones are turned with him into stubble.

29 Darts are counted as stubble: he laugheth at the shaking of a spear.

30 Sharp stones are under him: he spreadeth sharp pointed things upon the mire.

31 He maketh the deep to boil like a pot: he maketh the sea like a pot of ointment.

32 He maketh a path to shine after him; one would think the deep to be hoary.

33 Upon earth there is not his like, who is made without fear.

34 He beholdeth all high things: he is a king over all the children of pride.

#good omens#crowley#good omens analysis#aziracrow#aziraphale#crowly x aziraphale#good omens s2#good omens season 2#ineffable husbands

107 notes

·

View notes

Text

also a little sketch of how i imagined faust's mephisto back in 2019 :3 honestly he does remind me a little of obey me's design, and their personalities also have some aspects that are similar!

note: faust is a drama written by goethe where mephisto is a leading character in; it’s also widely regarded as germany's most important piece of literature & germany's national drama! i’m a little confused because i always thought mephisto was a character created by goethe, but the real story/myth that faust is based on apparently also had mephisto in it..

in reality, he’s often portrayed as an ugly devil, even symbolizing it in the second part during a masked play, as well as his name and character literally being related to rodents, parasites, etc., but i was 17 and in a situationship and needed a fictional man to thirst over.. so i designed him like this

obviously my later headcanon designs for obey me when mephisto was just a mentioned character are derived from my initial design, and i even had a headcanon that interlinks faust's mephisto & obey me's mephisto.. if you wanna look at old old designs, they’re in my pinned :') i always write too much wth

i was so attached to my headcanon, i had trouble liking the actual mephisto for a while, but i love him a lot now ♡ though i often think back to my version's mephisto and miss him a lil :)

#obey me#obey me!#obey me shall we date#obey me! shall we date?#obey me headcanon#obey me mephistopheles#obey me mephisto

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

pn character name post...TWO! last name edition and also the random psychonauts around the motherlobe who i didn't feel like including in the first one

including ones that aren't real surnames but are real words/clearly plays on real words. if one is missing assume either it doesn't mean anything/I couldn't find a meaning or I didn't think it needed explaining (e.g. Sweetwind, Doom)

Aquato - clearly a play on "aqua"

Nein - "no" in German

Zanotto - from a diminuitive of Zane or Zani/Zanni, the Venetian form of Gianni, which is short for Giovanni, which is the Italian form of "John" (God is gracious, Hebrew). unrelated but "Zanni" is also where we get the English word "zany"

Oleander - a flowering shrub that is grown as an ornamental or landscape plant despite being poisonous

Cruller - a kind of twisty donut :)

Boole - possibly from a Middle English word for bull

Canola - genericized trademark of a brand of cooking oil. the "can" is short for "Canada"

Zilch - German surname of uncertain etymology, slang for 'nothing'

Athens - after the Greek city, which Athena was probably named after, not the other way around

Lutefisk - Norwegian word for a traditional Nordic fish dish. it's soaked in lye.

Bulgakov - son of Bulgak (Bulgak being a surname in its own right that means "restless" or "troublesome"). Mikhail is probably named after the Russian author Mikhail Bulgakov, best known for The Master and Margarita

Fir - as in a fir tree

Phage - short for bacteriophage; a Greek suffix meaning "eater"

Bubai - Mandarin word meaning "invincible"

Tripe - animal stomach lining prepared for food; figuratively used to mean nonsense or valueless ideas/writing

Fideleo - possibly from Latin "fidelis", faithful/loyal

Cooper - barrel maker (English)

Soleil - "sun" in French

Houndstooth - a fabric pattern (that Becky does not wear)

Rolls - likely alluding to fat rolls

Bonaparte - French-ified version of Buonaparte, an Italian surname meaning "good match" or "good solution"

Teglee - derived from famed black velvet painter Edgar Leeteg; "Leeteg" was originally "Lütig", which I can't find a straight answer on what that means

Inflagrante - from "in flagrante", a shortened version of "in flagrante delicto", a Latin term that literally translates to "while the crime is blazing" and basically means "in the act"; it can refer to being in the act of doing something bad but particularly when shortened also means. well. in the act of Doing A Sex

DeLucca - alternate spelling of Italian De Luca, "[child] of Luca"; Luca ultimately meaning "from Lucania"

Pokeylope - pokey (slow) + lope (to walk slowly). good turtle name

Loboto - clearly a play on "lobotomy"

Forsythe - man of peace (Scottish Gaelic)

Natividad - Spanish for "nativity", meaning birth but particularly referring to the births of Mary or Jesus. a common name in the Philippines in addition to Spanish-speaking countries

Martinez - son of Martin (Spanish). "Martin" is derived from "Mars", Roman god of war and root of the word "martial"

Joseph - "he [God] will add" (Hebrew)

Gette - variation of Goethe, derived from "Gott" (God in Middle High German as well as modern German)

Neriman (also spelled Nariman) - a name of Persian origin, possibly meaning "brave mind"

Potts - topographical name. if you lived near holes in the ground you might have gotten called Potts

Malik - "king" in Arabic and various other Semitic languages; as a surname, is most common in India and Pakistan

OKAY now for the miscellaneous motherlobe NPCs

Brianne - "hill" or "power" (Celtic)

Chet - short for Chester, "fortress" (Latin)

Colin - young dog (Scottish)

Crenshaw - possibly "twisted wood" (Old English)

Dustin - from Thorsteinn, "Thor's stone" (Old Norse)

Evan - from the Welsh form of John

Forrest - take a guess.

Frank - Frenchman, more or less

Hawkins - diminuitive of Hawk or of Hal (from Henry, "home ruler", Germanic)

Jared - descent (Hebrew)

Kim - diminuitive of various names

Kramer - shopkeeper, merchant (German)

Lance - land (German/Old Saxon)

Larry - short for Laurence, "from Laurentum" (Latin)

Lori - short for Laura (laurel) or Lorraine (kingdom of Lothar, a Frankish king)

Sherri - from "cherie", French for darling

Susan - lily (Hebrew)

Thad - short for Thaddeus, Greek name of unclear origin

Whitlatch - "white path" or "white stream" (Old English)

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

honestly would love to hear more about twinflower if you felt like sharing? :)

I have been drafting this ask response on and off for over a week because I want everyone to love twinflower as much as I do thank you for your patience uh I mean yes! I do feel like sharing! thank you for enabling me! make yourself a cuppa and get comfy. it's Gloam's Natural History Hour, and here is everything you should love about the twinflower

Let us begin with the Latin name: Linnaea borealis. But first, it was Campanula serpyllifolia. Let me explain.

Twinflower is a small and unremarkable evergreen plant that nonetheless captured the heart of one of the world's most influential scientists in the eighteenth century. Species Plantarum is best-known for containing the first consistent use of binomial nomenclature (genus and species), but it was also there that Carl Linnaeus described twinflower for the first time.

It is a creeping subshrub that grows along the ground, with green and glossy shallow-toothed oval leaves about the size of dimes. Blooms come from delicate hairy stems that have unfolded themselves to the comparatively towering height of two or so inches above the ground. They are pinkish-white, nodding, and look like the sort of thing you'd imagine a fairy lives in. As you might suspect from the name, they grow in pairs. Some three centuries after Linnaeus first described it, one Mark C. in the comments of a 2013 blog post described the fragrance as "a delight to the most jaded sniffer".

In portraits, he is often found holding it. (Linnaeus, not Mark C.) He dearly loved it. But he could not name twinflower after himself: at first, it was classified in a different genus, and besides, it was poor taste. What's a guy to do?

Become acquainted with a wealthy Dutch botanist, Gronovius, son not of preachers and peasants but classical scholars, who would name it for him in his honour. Naturally. In gratitude, and advocacy for such acts of commemorative botanical naming, Linnaeus wrote in Critica Botanica:

It is commonly believed that the name of a plant which is derived from that of a botanist shows no connection between the two...[but]...Linnaea was named by the celebrated Gronovius and is a plant of Lapland, lowly, insignificant, disregarded, flowering but for a brief space — after Linnaeus who resembles it.

He would go on, of course, to receive fanmail from Rousseau. Contemporary Goethe would later write: "With the exception of Shakespeare and Spinoza, I know no one among the no longer living who has influenced me more strongly."

Lowly Linnaeus himself chose borealis, for Boreas, the Greek god of the north wind; and indeed it grows where the north wind blows, in a great circumboreal ring around the globe, from semi-shaded woodlands in southern British Columbia (hello), to tundra and taiga in Sweden and Siberia. You can find the same blooms in China and Poland and Minnesota. It's as old as glaciers. In Poland and other European countries it is in fact protected as glacial relict, and you can find it isolated at high elevations far south of its range, where it was left behind in the Pleistocene.

And now it is Linnaea borealis.

When Linnaeus was ennobled twenty years later for his services to botany, zoology, and medicine, he put the twinflower on his coat of arms. Some references use hedging (pun intended) language to describe their relationship: he was 'reported to be fond'. It was 'rumoured to be a favourite.' Bullshit, I say. He was in love. Anyone can see it.

One final etymological point of interest: his surname is itself borrowed from nature. After enrolling in university, his father had to abandon his patronymic last name and create family name. A priest, he created the Latinate Linnæus after linden - the great tree that grew on the family homestead.

And so from Latin and nature sprung the name, and not a generation later, unto Latin and nature it had returned. A name crafted of whole cloth in homage an enormous tree now describes the genus of a plant that tops out at three inches tall and has flowers smaller than your thumbnail.

In spite of this, its uses are myriad. A common name of twinflower in Norwegian, nårislegras, translates to corpse rash grass, for its use in treating skin conditions. It can be made into a tea to take in pregnancy or provide relief of menstrual cramps. Scandinavian folk medicines use it for rheumatism. Humans have made it into teas, tinctures, decoctions, poultices, and even administered its therapeutic properties via smoke inhalation. And then there is its persistent and widespread use in filling our hearts: lending itself century over century and season over season to mankind, to a coat of arms, a poem, a photo, a fond memory—

Ralph Waldo Emerson, in Woodnotes I, says this of twinflower and the man it's named for:

He saw beneath dim aisles, in odorous beds,

The slight Linnaea hang its twin-born heads,

And blessed the monument of the man of flowers,

Which breathes his sweet fame through the northern bowers.

Art is subjective, but I will happily admit I prefer this passage, from Robert of Isle Royale, on the website Minnesota Wildflowers:

My wife and I encountered Linnaea borealis in the last week of June 38 years ago on Isle Royale. We now live in Vilas County in northern Wisconsin and were happy to find a large patch of Twinflowers growing under the sugar maples, balsam fir and hemlock on our property there. This is now very special to us and we await their flowering each June around our anniversary.

A final note. Twinflower requires genetically different individuals to set seed and reproduce sexually. This is known as self-incompatibility. Thus the plants in those isolated spots - old glacial hideouts, or places with fragmented plant populations like Scotland - only reproduce clonally. Let us end with imagining a plant that has not reproduced with another for millennia, but instead carries its line on its own back, and survives by creating itself over and over again, in a genetically identical colony that grows with wet summers and shrinks with dry ones; that briefly blooms every June, lifting its flowers high above itself, a hundred tiny beacons that will be answered only by its own voice; and there, too far for pollination, but a distance you or I could travel in minutes, is its nearest partner, doing the same thing, across an impossible void that looks to us as nothing more than a gap between one part of the woods and the next. Yet it is L. borealis, named for a man named for a tree, that is capable of looking out across generations of humankind walking fragmented pine woodlands and the ghostly southern border of the Laurentide ice sheet, and seeing nothing more than the gap between one seed-set and the next.

Let us end with imagining a tiny plant, and ourselves beside it, loving it for hundreds of years, even smaller.

#asks#botany#plants#twinflower#Linnaea borealis#an essay#that i have put my whole heart into#read it?#or don't but go sit in nature for a bit#and marvel at it all til ur chest hurts with love#that's the takeaway i'm going for here anyway#about me#outside the cabin#my writing

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

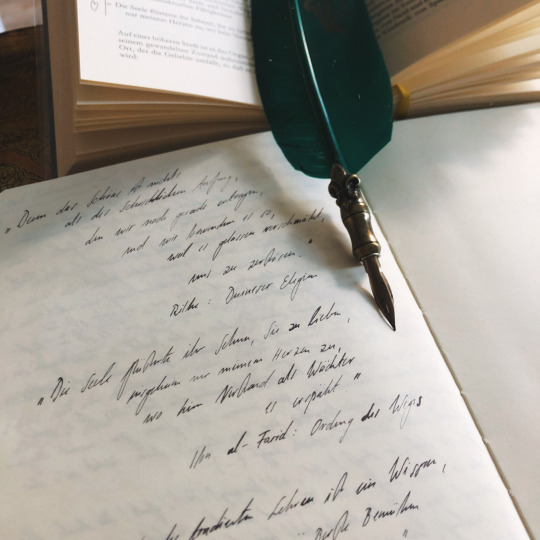

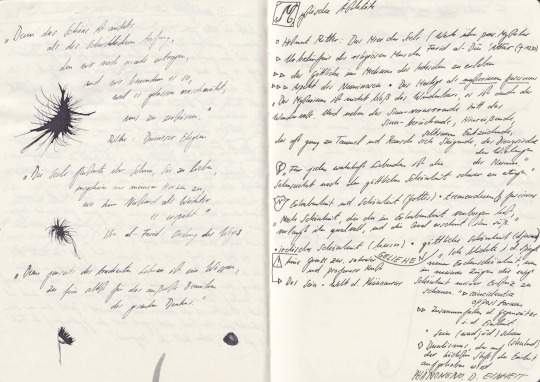

‘The covenant of love was granted to me on the day when there was no day, in my primal time, before she appeared to conclude the contract. And I obtained my love not by hearing or seeing, not by acquisition and not by an inclination of nature, but I loved her already in the world of divine command, when nothing had appeared, before creation I was drunk.’

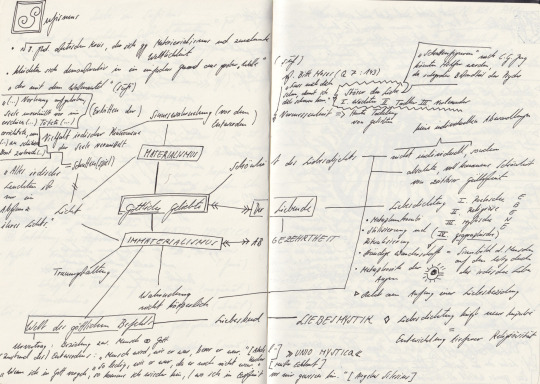

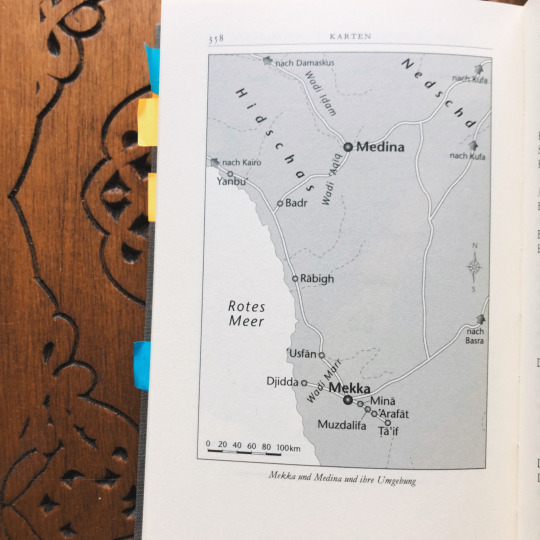

Ibn al-Farid was born in 1181 in Cairo, Egypt, during the Ayyubid period. He was a member of a prominent family and received a classical education in Islamic sciences, literature, and poetry. Ibn al-Farid is regarded as one of the greatest mystical poets in Arabic literature. His work has profoundly influenced subsequent generations of poets and Sufis.

The Diwan of Ibn al-Farid is a collection of his poetry, encompassing his famous qasidas (odes) and other forms of Arabic poetry. This compilation showcases his mastery in both poetic form and spiritual depth and reflects themes of divine love, union with God, and the spiritual journey.

Through translations, his mystical odes were known in the European region, first by Viennese court interpreter and friend of Goethe Josef von Hammer-Purgstall (1774 - 1856): The Arabic Song of Love (1854).

1917 the didactic poem ‘Al-Ta'iyyah al-Kubra’ was translated into Italian by Ignazio Di Matteo, critically analysed by Carlo Alfonso Nallino ‘Poema mistico’ and Alleyne Nicholson's work of 1940 'The Odes of Ibnu 'l-Farid' bulding the basis for this edition by Prof. Renate Jacobi.

Love poetry - Ideal of love

Individual relationship of lovers above the norms and demands of society

Frequent motif:

Conflict, experienced as tragic in a world of social change, as a hopeless relationship in which the lovers who cling to it perish;

Typical of ‘udhritic poetry (Bedouin tribe of the ’Udhra):

By no means platonic, but sexual fulfilment only in marriage, which, however, is denied

‘The poet and his beloved have known each other since childhood, fall in love and want to marry, but the woman is married off to a richer man by her parents. The lovers remain faithful to each other. They meet, but without offending decency, and in the end the poet, and sometimes the lover, die of grief.’

‘Poets of the ‘Udhra tribe from the 7th century sang of their passionate love for a single woman who outlasts death. Before that, the concept of ‘udhrite love (al-hubb al-’udhri) was derived, which plays an important role in classical Arabic literature, in poetry and prose, as well as in profane love theory.’

Famous couples:

> Djamil and Buthaina (Djamil ibn Ma'mar, d. 701, is the most important poet of the ‘udhra tribe; his divan is considered relatively reliable)

> Kuthaiyir and ‘Azza (Kuthaiyir, d. 723)

> Qais and Lubna (Qais ibn al-Dharih, d. 689, like Kuthaiyir belonging to a different tribe, but attributed to the ‘Udhrite school; from the tribe of “Amir, called al-Madjnun ”the madman’ and his lover Laila;

Poeticised by many mystical poets in many Islamic literatures + symbol of absolute love of God; doubts about historicity, attributed verses probably do not date from the 7th century either;)

Basic structure resembles ‘udhritic poetry, yet deviations:

‘After Madjnun loses Laila, he falls into madness. He turns away from human society and lives among the animals in the desert until his death, focussing entirely on his love for Laila. His renunciation of the outside world is so total that he is unable to turn his attention to the real Laila when she visits him in the desert. His inner image of her holds him completely captive.’ [p. 161]

(The poet's response to his lover's accusation that he does not pay attention to her:)

‘You fill my heart so much that I cannot look at you.’

[Abbas ibn al-Ahnaf, d. 808)

'Udhritic love in two genres: Poetic (ghazal) and narrative form; complement each other and are placed in a historical context in Arabic tradition

+ Narratives initially oral, records were collected in the 8th century

The concept of ‘udhritic love’ reached Heinrich Heine via Henri Stendhal's treatise ‘De l'amour’ (1822):

The wonderful Sultan’s daughter

Every day used to rush,

Around the evening hour to the fountain,

Where the white waters splash.

The young slave stood pale

At the fountain, around evening,,

Where the white waters wail;

And his paleness was increasing.

One evening the princess approached him

With sudden words, like a whip:

I want to know your name,

Your home and your kinship!

And the slave spoke: My name is Mohammed

I come from the Yemen that I cherish,

And I stem from the tribe of Asra,

From those who, when they love, they perish.

[Translation by Joseph Masaad]

My (incomplete) notes in German

#literature#book#bookworm#book cover#classic literature#world literature#arabic poetry#arabic culture#sufi#sufism#monism#mysticism#divine love#love#poetry#cultural heritage

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hob Gadling name meaning (and a revelation that hit me while writing this post):

Hob is an old nickname for Robert or Robin. It probably derives from old English names like Hrothbert (archaic version of Robert). Today the nickname would be Bob or Rob and or Bobby or Robby. The most common nickname for Robert or Robin today is Bob.

I'm not entirely sure how Hob evolved into Bob but then again the German nickname for Marguerite is Gretchen. That seems odd too when you think about it.

Apparently the name Gadling happens to mean "Loyal companion of low Birth."

So yes, Hob Gadling's name is pretty much "Bob Friendly Every-man."

Wait... I just realized something as my own mother was named Marguerite and

Marguerite was Faust's lover in Goethe's Faust and... Ooooh, Neil, you delightfully sneaky man... Marguerite / Gretchen is who saves Faust's soul and takes him to Heaven. Morpheus is very, very likely spending his afterlife in Hob's dreams. Like Gretchen saving Faust's soul, Hob saved Morpheus's. Hob is Morpheus's Gretchen!

Faust and Marlowe's less-hopeful Doctor Faustus are referenced several times in The Sandman. Including a book in The Dreaming Library where Marlowe allows Faust to be redeemed like in Goethe's telling.

In Goethe's Faust Part 2 it's Marguerite AKA Gretchen who pleads Faust's case to higher powers because he's learned to care and learned that the ultimate life experience he's been seeking is love- caring about others, thus saving his soul from his bargain with Mephisto.

I can't believe I didn't realize until just now while writing this post. Hob is Morpheus's Gretchen. Morpheus spending his afterlife in Hob’s dream is Morpheus’s soul being saved by his Gretchen, Hob Gadling. Okay, NOW I ship it.

48 notes

·

View notes

Note

Jumping off your comment on Substack that Poe invented avant-garde poetry and pulp fiction, and Jane Austen invented romance fiction, what other authors invented genres? What was the most recent genre invented?

I was being deliberately provocative with that statement. Often it's hard to name a single inventor. Why are all these genres invented in the last three centuries? Because of print culture and mass literacy's explosion of discourse. Back before the printing press and mass literacy, you didn't need that many genres; tragedy, comedy, epic, and romance were enough. And most modern genres are, as critics like Northrop Frye would insist, developments of these. (Austen writes comedy; Poe writes romance.) But still, with so many more opportunities to create, more is created, so a few further generalizations can be made. Walter Scott invented the historical novel at the same time as Poe and Austen were inventing everything else. And though I credited Austen with the realist novel in its modern form, Balzac had a hand in that, too, turning Scott's approach to the past as living continuum onto the present itself. Plenty of authors invent sub-genres of broader genres. Poe gives us modern horror in general by modernizing the Gothic, itself devised as the return of modernity's repressed by Walpole and Radcliffe, in the same way that Austen modernizes the domestic sentimental novel of Richardson and Rousseau by synthesizing it with the comic epic of Fielding. These innovations flow into others, from the realistic novel of ideas in George Eliot, the proto-modernist novel of consciousness in Henry James on Austen's side to the further techno-modernizations of the Gothic in Stoker, Stevenson, and eventually Lovecraft on Poe's. The superhero is invented in the 20th century out of pulp influences, synthesizing the Poe-like detective (itself a romance derivative: the modern knight-errant) with Wellsian science-fiction scenarios (themselves descended from the romance's enchanted landscapes); the inventors here, not quite literary or artistic geniuses, are Siegel and Shuster, who probably would have cited Hercules and Samson. Going back to high literature, the bildungsroman is invented in the 18th century as the epic itinerary of the modern soul in an alien society: Defoe and Fielding, Rousseau and Goethe. The bildungsroman becomes the existential novel in the late 19th century, often mediated by Poe's own influence, his injection of the immobilizing irrational into the narrative of development, as with Notes from Underground, and flowing from there into Hamsun, Camus, Sartre, Dazai, Ellison, and into the present. Dostoevsky more than anyone else can also perhaps also be credited with the novel of ideas, though, as I said, George Eliot provides a stabler English version. The synthesizers and the inventors, the last and the first, can be hard to tell apart. Austen and Poe stand at the end as well as at the beginning of traditions, each looking back to the ruins of an older order. Walter Benjamin: "every great work founds a genre or dissolves one." These two gestures are the same gesture. In Ulysses we find Austen's domestic realism and rational psychology fused with Poe's formalism and irrational psychology at the apotheosis of modern fiction and the birth of the 20th-century novel. Kafka and Borges each come out of Poe's innovation to create something new and indefinable we are still living with, still annotating, still working on, too "still in it" to quite name it. Woolf is unimaginable without Austen, yet not quite deducible from Austen, and still a regulating influence. It's an infinite topic. As for the most recent genres and their inventors, someone younger than me will have to answer; go ahead, tell me to read One Piece; tell me to play video games; you won't be the first.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Rosa Mayreder - photograph - 1905

Rosa Mayreder (née Obermeyer; 30 November 1858, in Vienna – 19 January 1938, in Vienna) was an Austrian freethinker, author, painter, musician and feminist. She was the daughter of Marie and Franz Arnold Obermayer who was a wealthy restaurant operator and barkeeper.

Rosa had twelve brothers and sisters and although her conservative father did not believe in the formal education of girls he allowed her to participate in the Greek and Latin lessons of one of her brothers. She also received private instruction in French, painting and the piano.

Rosa Obermeyer was born on 30 November 1858. Her father was Franz Arnold Obermayer, who was the owner of a prosperous tavern. Accounts of Mayreder's family, social atmosphere, and insights to her personality are recorded in a series of diary entries, the first of which is dated 28 April 1873; she was fourteen at the time. Her autobiographical diary entries covered a range of topics from her every-day life to her feelings on war.

Growing up, Mayreder lived in a large household and received an education that was typical of the well-off. Mayreder was taught to play the piano, sing, speak French, and draw by private tutors. However, Mayreder was jealous that her less academically inclined brothers were given more educational opportunities. Later, the impact of this schooling would become evident, as Mayreder would revolt against the way girls were educated among the middle class. She criticized the sexual double standard and prostitution. At seventy, in 1928, she was recognized as an honorary citizen in Vienna. One such instance of rebellion was her decision to never wear a corset when she turned eighteen. This act of defiance was not only a social statement, but a personal dig against her mother, who believed it was a woman's duty to derive her sense of self from her husband and sons.

As she grew into adulthood, Mayreder was exposed to a plethora of artists, writers, and philosophers. One of the most influential activities on Mayreder's future were her frequent meetings with Josef Storck, Wiener Kunstgewebeschule, Rudolf von Waldheim, Friedrich Eckstein, and her brothers Karl, Julius, and Rudolf. Additionally, the writings of Nietzsche, Goethe, and Kant had a significant influence on her as well. Her exposure to people such as these allowed Mayreder to come in contact with those who acknowledged the discrepancies between men and women in society and encouraged her to pursue involvement in the sociological issues she believed in.

In 1881 Rosa married the architect Karl Mayreder, who later became rector of the technical university in Vienna. The marriage was harmonious but remained childless. In 1883 Rosa had an abortion and she also had two affairs, which she describes in detail in her diaries. Karl suffered repeated depressions from 1912 until his death in 1935.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Nor does this- [the whale's tail's]] amazing strength, at all tend to cripple the graceful flexion of its motions; where infantileness of ease undulates through a Titanism of power. On the contrary, those motions derive their most appalling beauty from it. Real strength never impairs beauty or harmony, but it often bestows it; and in everything imposingly beautiful, strength has much to do with the magic. Take away the tied tendons that all over seem bursting from the marble in the carved Hercules, and its charm would be gone. As devout Eckerman lifted the linen sheet from the naked corpse of Goethe, he was overwhelmed with the massive chest of the man, that seemed as a Roman triumphal arch."

Melville's Moby Dick

0 notes

Text

Iqbal and Nietzsche are two of the most influential thinkers of the modern era, but they have very different views on human nature and destiny.

Iqbal adisagreed with Nietzsche on many fundamental issues,

such as his atheism, his nihilism, his rejection of religion and morality, and his emphasis on brute force and conflict. Iqbal believed that

Nietzsche's Superman was a degraded version of the Islamic concept of thePerfect man or inasn-i-kamil. Let's understand first,

what is Iqbal's Perfect Man: -spiritual and ethical being who seeks to realize the divine potential within him -not a slave to his passions or his environment, but a master of himself and his destiny.-not a rebel against God or society, but a servant of both -not a destroyer of values, but a creator of new ones.

-derived his concept of the Perfect Man from the Quran, the Hadith, and the Sufi tradition. He also cited examples of the Perfect Man in Islamic-For insan-i-kamil Iqbal cited the example of Prophet Muhammad ﷺ, his companions, and scholars like shah Waliullah -the Perfect Man was the ideal model for Muslims to emulate in their personal and collective lives.

Nietzsche, on the other hand, was a philosopher who challenged the foundations of Western civilization and culture. He proclaimed the death of God and the end of morality. He advocated for a radical individualism and a will to power that transcended all limits and norms.

He envisioned a new type of human being who would create his own values and meaning in a world without any. - Superman or Overman is a rare and exceptional being who rises above the herd mentality and the slave morality of the masses-

He is not bound by any conventional morality or religion, but follows his own inner law.

He is not afraid of suffering or death, but embraces them as opportunities for growth.

He is not a follower of anyone or anything, but a leader and a creator.- derived his concept of the Superman from his own personal experience and his interpretation of ancient Greek and Germanic mythology. -cited examples of the Superman in history and literature, such as Napoleon Bonaparte, Julius Caesar, Goethe, Shakespeare, and Zarathustra.

He believed that the Superman was the future goal of humanity and the highest expression of life.

The vision of Iqbal that emphasizes spirituality, ethics, harmony, and service. The vision of Nietzsche that emphasizes individuality, power, conflict, and creativity.

Overall, Iqbal's Philosophy is much more enriching and realistic than Neitzsche. Where as Neitzsche's philosophy may appear appealing to a nihilistic and atheistic man, but it lacks the vigor and spirituality of Iqbal's.

- Taiyeb Mughal

1 note

·

View note

Quote

Brahms – Piano Quartet no. 3 in c minor (1875)

I’m surprised that I haven’t covered this work yet. It’s been one of my favorites for a long time now…it was actually my introduction to Brahms. I was kind of overwhelmed by most of the music, so I didn’t really like the full quartet. But the slow movement was, and is, one of the most beautiful pieces of music I’ve ever heard. Of course I say that for every great piece, so it’s ok if you roll your eyes. But over time this became one of my favorite chamber works, and among my personal top favorite works by Brahms. When Brahms brought the manuscript of this quartet to his publisher, he asked for the picture on the cover to be a man holding a gun to his head. This allusion to Goethe’s Werther (about a young man falling in love with an older married woman who didn’t love him back, and eventually committing suicide because of it) has led people to assume this piece is a musical confession of his unrequited love for Clara Schumann, and how it contributed to some private emotional turmoil. It does at least give a more human side to a composer who’s always being called a dull academic. And perhaps it was this personal aspect, and details and references to Clara and Robert, that kept him from publishing it right away. He wrote it around the same time as his first two quartets, but left it in a drawer for decades until deciding to come back and finish it. That at least explains why, overall, it’s somewhat more ‘direct’ than the denser textures of his late music.

The first movement has a lot of the “academic” moments I mentioned, where in following with Classical tradition, the entire sonata form is based on or derives from the opening. The C tolls in octaves on the piano, the strings play a somber theme with emphasis on a falling two note motif. Then, we go a semi-tone lower, which goes against classical form. The Romantic justification can come from the Werther-suicide image; like the character, the music is losing its sense of self. We modulate back to c minor, even with odd pizzicato notes outside of the key, and now hear a passionate wave of a melody again based on the two-note motif. That transitions into the softer and lyrical “B” melody, but even this melody derives from the motif. Again, this motif will be reused to an obsessive degree and re-contextualized for the mood in a way that would make Beethoven proud. The next section starts with a repeating Eb on the piano, again making me think of bells, that the strings start playing over. This acts as a pedal point, which in the 19th century signaled “old fashioned”, “Bach”, “church music” etc. and Brahms was criticized and called regressive/conservative a lot with his use of pedal points as an example of this ‘problem’. But from one of the letters he wrote to Clara, he said he knew she had a soft spot for pedal points. If you hear them in Brahms’ music, it’s probably because he knew Clara would like them. Anyway, we also get a kind of ‘heroic’ revision of the theme with heavy pounding chords and a scratchy viola. Into the ‘development’ section we have the lyrical version of the theme playing in canon in the strings over an unsettled rumble of another motivic pattern in the piano’s bass. Through all that turmoil, the last section opens with a much softer, more contemplative version of the lyrical theme. But the intensity comes back and collapses into the same somber atmosphere of the opening.

The second movement rushes in with a wide leap downward, which becomes the motif to be obsessed over here. More-so than the first movement does this scherzo show Brahms’ ‘heavy handedness’ and love for thick textures, full chords, and slamming into the piano’s bass registers. The strings interject with the rhythm, pulsating the motif, and soon the violin pulls a melody out of it all. And I think I hear a lot of “hunting horn” calls coming through open fifths, and I wonder if Brahms were trying to evoke “the hunt” with both horn calls and a kind of ‘galloping’ rhythm. Or maybe this is a kind of evocation of the woods which horn-calls were ubiquitous with in 19th century German music, like this scherzo is a wild and dark shaded Friederich painting that shows nature as a menacing and awesome thing. Or I could be speculating too much. The biggest surprise is how this movement ends in the major, with a triumph you wouldn’t expect early on, especially after the kind of devastating ending of the first movement.

This helps us into the slow movement, which I already said was in my short-list of ‘most beautiful pieces I’ve ever heard’. It starts with the cello singing the melody, a very long almost operatic melody, over the piano’s syncopated chords, with a lot of slight dissonances and leading tones that really push the emotional ‘longing’ in this music. At the end of the melody, the violin joins in a duet and it plays a slightly altered version of it. The cello has a rich accompanying part that mixes into the fabric. And then something magical happens; the viola joins the violin and cello for a trio on a new melody (in the Brahms fashion, the ‘new’ melody derives from the first one), while the piano’s texture changes into slow arpeggios. After that section, the rhythm gets a bit disjointed, and the harmonies a little more mysterious, segue-ways into another gorgeous magical part: another revision plays in the strings in call and response style, while scales in contrary motion on the keyboard emphasize and make the dissonances a little harsher, more paneful, and more poignient. I won’t keep detailing this movement since words aren’t enough. I’ll end with a mention that Brahms often used pizzicato to represent water, so my inner Romantic wants to think of this as a peaceful scene by a river, a serious contrast in the emotional intensity that we’ve heard so far.

The last movement opens in a way feels like Italian opera. The violin plays a melody over the piano – the right hand is playing a restless figuration that modulates like a Bach keyboard piece, while the left hand plays the beat and also emphasizes a three note motif which has to be a homage to Beethoven. Funny, I think if Brahms heard me say “this might be a Beethoven reference,” he’d treat me the way he treated critics of his first symphony, “of course it is! Any ass could see that!” Soon the full string section comes in, and again we get the dense textures and hyper-drama of the scherzo (along with the heavy-handedness). Through this section Brahms de-stabalizes the rhythm, but comes back to stability along with an easier and thinner section in the major. The development has the strings playing with and obsessing over, what else, but fragments of the opening melody. In its recap, the melody is played again in unison strings over a fiercely difficult etude looking passage on the piano made up of broken octaves. During this recap the instruments are again disrupted by complicated passagework that messes up the rhythm. After getting overwhelmed by the violence, Brahms again surprises us with a major key ending. But maybe it isn’t a surprise, maybe the scherzo was a foreshadowing. That’s the thing that keeps bringing me back to Brahms: everything that happens is more deliberate than you’d assume at first. If he presents an idea, it will not be left alone; it will return as an important component, and the whole structure is based on what Schoenberg would later call ‘developing variation’. From one melody, an entire piece can emerge.

Movements:

1. Allegro non troppo

2. Scherzo: Allegro

3. Andante

4. Finale: Allegro comodo

mikrokosmos: Brahms – Piano Quartet no. 3 in c minor (1875) I’m surprised that I haven’t covered this work yet. It’s been one of my favorites for a long time now…it was actually my introduction to Brahms. I was kind of overwhelmed by most of the music, so I didn’t really like the full quartet.…

0 notes

Quote

Brahms – Piano Quartet no. 3 in c minor (1875)

I’m surprised that I haven’t covered this work yet. It’s been one of my favorites for a long time now…it was actually my introduction to Brahms. I was kind of overwhelmed by most of the music, so I didn’t really like the full quartet. But the slow movement was, and is, one of the most beautiful pieces of music I’ve ever heard. Of course I say that for every great piece, so it’s ok if you roll your eyes. But over time this became one of my favorite chamber works, and among my personal top favorite works by Brahms. When Brahms brought the manuscript of this quartet to his publisher, he asked for the picture on the cover to be a man holding a gun to his head. This allusion to Goethe’s Werther (about a young man falling in love with an older married woman who didn’t love him back, and eventually committing suicide because of it) has led people to assume this piece is a musical confession of his unrequited love for Clara Schumann, and how it contributed to some private emotional turmoil. It does at least give a more human side to a composer who’s always being called a dull academic. And perhaps it was this personal aspect, and details and references to Clara and Robert, that kept him from publishing it right away. He wrote it around the same time as his first two quartets, but left it in a drawer for decades until deciding to come back and finish it. That at least explains why, overall, it’s somewhat more ‘direct’ than the denser textures of his late music.

The first movement has a lot of the “academic” moments I mentioned, where in following with Classical tradition, the entire sonata form is based on or derives from the opening. The C tolls in octaves on the piano, the strings play a somber theme with emphasis on a falling two note motif. Then, we go a semi-tone lower, which goes against classical form. The Romantic justification can come from the Werther-suicide image; like the character, the music is losing its sense of self. We modulate back to c minor, even with odd pizzicato notes outside of the key, and now hear a passionate wave of a melody again based on the two-note motif. That transitions into the softer and lyrical “B” melody, but even this melody derives from the motif. Again, this motif will be reused to an obsessive degree and re-contextualized for the mood in a way that would make Beethoven proud. The next section starts with a repeating Eb on the piano, again making me think of bells, that the strings start playing over. This acts as a pedal point, which in the 19th century signaled “old fashioned”, “Bach”, “church music” etc. and Brahms was criticized and called regressive/conservative a lot with his use of pedal points as an example of this ‘problem’. But from one of the letters he wrote to Clara, he said he knew she had a soft spot for pedal points. If you hear them in Brahms’ music, it’s probably because he knew Clara would like them. Anyway, we also get a kind of ‘heroic’ revision of the theme with heavy pounding chords and a scratchy viola. Into the ‘development’ section we have the lyrical version of the theme playing in canon in the strings over an unsettled rumble of another motivic pattern in the piano’s bass. Through all that turmoil, the last section opens with a much softer, more contemplative version of the lyrical theme. But the intensity comes back and collapses into the same somber atmosphere of the opening.

The second movement rushes in with a wide leap downward, which becomes the motif to be obsessed over here. More-so than the first movement does this scherzo show Brahms’ ‘heavy handedness’ and love for thick textures, full chords, and slamming into the piano’s bass registers. The strings interject with the rhythm, pulsating the motif, and soon the violin pulls a melody out of it all. And I think I hear a lot of “hunting horn” calls coming through open fifths, and I wonder if Brahms were trying to evoke “the hunt” with both horn calls and a kind of ‘galloping’ rhythm. Or maybe this is a kind of evocation of the woods which horn-calls were ubiquitous with in 19th century German music, like this scherzo is a wild and dark shaded Friederich painting that shows nature as a menacing and awesome thing. Or I could be speculating too much. The biggest surprise is how this movement ends in the major, with a triumph you wouldn’t expect early on, especially after the kind of devastating ending of the first movement.

This helps us into the slow movement, which I already said was in my short-list of ‘most beautiful pieces I’ve ever heard’. It starts with the cello singing the melody, a very long almost operatic melody, over the piano’s syncopated chords, with a lot of slight dissonances and leading tones that really push the emotional ‘longing’ in this music. At the end of the melody, the violin joins in a duet and it plays a slightly altered version of it. The cello has a rich accompanying part that mixes into the fabric. And then something magical happens; the viola joins the violin and cello for a trio on a new melody (in the Brahms fashion, the ‘new’ melody derives from the first one), while the piano’s texture changes into slow arpeggios. After that section, the rhythm gets a bit disjointed, and the harmonies a little more mysterious, segue-ways into another gorgeous magical part: another revision plays in the strings in call and response style, while scales in contrary motion on the keyboard emphasize and make the dissonances a little harsher, more paneful, and more poignient. I won’t keep detailing this movement since words aren’t enough. I’ll end with a mention that Brahms often used pizzicato to represent water, so my inner Romantic wants to think of this as a peaceful scene by a river, a serious contrast in the emotional intensity that we’ve heard so far.

The last movement opens in a way feels like Italian opera. The violin plays a melody over the piano – the right hand is playing a restless figuration that modulates like a Bach keyboard piece, while the left hand plays the beat and also emphasizes a three note motif which has to be a homage to Beethoven. Funny, I think if Brahms heard me say “this might be a Beethoven reference,” he’d treat me the way he treated critics of his first symphony, “of course it is! Any ass could see that!” Soon the full string section comes in, and again we get the dense textures and hyper-drama of the scherzo (along with the heavy-handedness). Through this section Brahms de-stabalizes the rhythm, but comes back to stability along with an easier and thinner section in the major. The development has the strings playing with and obsessing over, what else, but fragments of the opening melody. In its recap, the melody is played again in unison strings over a fiercely difficult etude looking passage on the piano made up of broken octaves. During this recap the instruments are again disrupted by complicated passagework that messes up the rhythm. After getting overwhelmed by the violence, Brahms again surprises us with a major key ending. But maybe it isn’t a surprise, maybe the scherzo was a foreshadowing. That’s the thing that keeps bringing me back to Brahms: everything that happens is more deliberate than you’d assume at first. If he presents an idea, it will not be left alone; it will return as an important component, and the whole structure is based on what Schoenberg would later call ‘developing variation’. From one melody, an entire piece can emerge.

Movements:

1. Allegro non troppo

2. Scherzo: Allegro

3. Andante

4. Finale: Allegro comodo

mikrokosmos: Brahms – Piano Quartet no. 3 in c minor (1875) I’m surprised that I haven’t covered this work yet. It’s been one of my favorites for a long time now…it was actually my introduction to Brahms. I was kind of overwhelmed by most of the music, so I didn’t really like the full quartet.…

0 notes

Quote

Brahms – Piano Quartet no. 3 in c minor (1875)

I’m surprised that I haven’t covered this work yet. It’s been one of my favorites for a long time now…it was actually my introduction to Brahms. I was kind of overwhelmed by most of the music, so I didn’t really like the full quartet. But the slow movement was, and is, one of the most beautiful pieces of music I’ve ever heard. Of course I say that for every great piece, so it’s ok if you roll your eyes. But over time this became one of my favorite chamber works, and among my personal top favorite works by Brahms. When Brahms brought the manuscript of this quartet to his publisher, he asked for the picture on the cover to be a man holding a gun to his head. This allusion to Goethe’s Werther (about a young man falling in love with an older married woman who didn’t love him back, and eventually committing suicide because of it) has led people to assume this piece is a musical confession of his unrequited love for Clara Schumann, and how it contributed to some private emotional turmoil. It does at least give a more human side to a composer who’s always being called a dull academic. And perhaps it was this personal aspect, and details and references to Clara and Robert, that kept him from publishing it right away. He wrote it around the same time as his first two quartets, but left it in a drawer for decades until deciding to come back and finish it. That at least explains why, overall, it’s somewhat more ‘direct’ than the denser textures of his late music.

The first movement has a lot of the “academic” moments I mentioned, where in following with Classical tradition, the entire sonata form is based on or derives from the opening. The C tolls in octaves on the piano, the strings play a somber theme with emphasis on a falling two note motif. Then, we go a semi-tone lower, which goes against classical form. The Romantic justification can come from the Werther-suicide image; like the character, the music is losing its sense of self. We modulate back to c minor, even with odd pizzicato notes outside of the key, and now hear a passionate wave of a melody again based on the two-note motif. That transitions into the softer and lyrical “B” melody, but even this melody derives from the motif. Again, this motif will be reused to an obsessive degree and re-contextualized for the mood in a way that would make Beethoven proud. The next section starts with a repeating Eb on the piano, again making me think of bells, that the strings start playing over. This acts as a pedal point, which in the 19th century signaled “old fashioned”, “Bach”, “church music” etc. and Brahms was criticized and called regressive/conservative a lot with his use of pedal points as an example of this ‘problem’. But from one of the letters he wrote to Clara, he said he knew she had a soft spot for pedal points. If you hear them in Brahms’ music, it’s probably because he knew Clara would like them. Anyway, we also get a kind of ‘heroic’ revision of the theme with heavy pounding chords and a scratchy viola. Into the ‘development’ section we have the lyrical version of the theme playing in canon in the strings over an unsettled rumble of another motivic pattern in the piano’s bass. Through all that turmoil, the last section opens with a much softer, more contemplative version of the lyrical theme. But the intensity comes back and collapses into the same somber atmosphere of the opening.

The second movement rushes in with a wide leap downward, which becomes the motif to be obsessed over here. More-so than the first movement does this scherzo show Brahms’ ‘heavy handedness’ and love for thick textures, full chords, and slamming into the piano’s bass registers. The strings interject with the rhythm, pulsating the motif, and soon the violin pulls a melody out of it all. And I think I hear a lot of “hunting horn” calls coming through open fifths, and I wonder if Brahms were trying to evoke “the hunt” with both horn calls and a kind of ‘galloping’ rhythm. Or maybe this is a kind of evocation of the woods which horn-calls were ubiquitous with in 19th century German music, like this scherzo is a wild and dark shaded Friederich painting that shows nature as a menacing and awesome thing. Or I could be speculating too much. The biggest surprise is how this movement ends in the major, with a triumph you wouldn’t expect early on, especially after the kind of devastating ending of the first movement.

This helps us into the slow movement, which I already said was in my short-list of ‘most beautiful pieces I’ve ever heard’. It starts with the cello singing the melody, a very long almost operatic melody, over the piano’s syncopated chords, with a lot of slight dissonances and leading tones that really push the emotional ‘longing’ in this music. At the end of the melody, the violin joins in a duet and it plays a slightly altered version of it. The cello has a rich accompanying part that mixes into the fabric. And then something magical happens; the viola joins the violin and cello for a trio on a new melody (in the Brahms fashion, the ‘new’ melody derives from the first one), while the piano’s texture changes into slow arpeggios. After that section, the rhythm gets a bit disjointed, and the harmonies a little more mysterious, segue-ways into another gorgeous magical part: another revision plays in the strings in call and response style, while scales in contrary motion on the keyboard emphasize and make the dissonances a little harsher, more paneful, and more poignient. I won’t keep detailing this movement since words aren’t enough. I’ll end with a mention that Brahms often used pizzicato to represent water, so my inner Romantic wants to think of this as a peaceful scene by a river, a serious contrast in the emotional intensity that we’ve heard so far.

The last movement opens in a way feels like Italian opera. The violin plays a melody over the piano – the right hand is playing a restless figuration that modulates like a Bach keyboard piece, while the left hand plays the beat and also emphasizes a three note motif which has to be a homage to Beethoven. Funny, I think if Brahms heard me say “this might be a Beethoven reference,” he’d treat me the way he treated critics of his first symphony, “of course it is! Any ass could see that!” Soon the full string section comes in, and again we get the dense textures and hyper-drama of the scherzo (along with the heavy-handedness). Through this section Brahms de-stabalizes the rhythm, but comes back to stability along with an easier and thinner section in the major. The development has the strings playing with and obsessing over, what else, but fragments of the opening melody. In its recap, the melody is played again in unison strings over a fiercely difficult etude looking passage on the piano made up of broken octaves. During this recap the instruments are again disrupted by complicated passagework that messes up the rhythm. After getting overwhelmed by the violence, Brahms again surprises us with a major key ending. But maybe it isn’t a surprise, maybe the scherzo was a foreshadowing. That’s the thing that keeps bringing me back to Brahms: everything that happens is more deliberate than you’d assume at first. If he presents an idea, it will not be left alone; it will return as an important component, and the whole structure is based on what Schoenberg would later call ‘developing variation’. From one melody, an entire piece can emerge.

Movements:

1. Allegro non troppo

2. Scherzo: Allegro

3. Andante

4. Finale: Allegro comodo

mikrokosmos: Brahms – Piano Quartet no. 3 in c minor (1875) I’m surprised that I haven’t covered this work yet. It’s been one of my favorites for a long time now…it was actually my introduction to Brahms. I was kind of overwhelmed by most of the music, so I didn’t really like the full quartet.…

0 notes

Quote

Brahms – Piano Quartet no. 3 in c minor (1875)

I’m surprised that I haven’t covered this work yet. It’s been one of my favorites for a long time now…it was actually my introduction to Brahms. I was kind of overwhelmed by most of the music, so I didn’t really like the full quartet. But the slow movement was, and is, one of the most beautiful pieces of music I’ve ever heard. Of course I say that for every great piece, so it’s ok if you roll your eyes. But over time this became one of my favorite chamber works, and among my personal top favorite works by Brahms. When Brahms brought the manuscript of this quartet to his publisher, he asked for the picture on the cover to be a man holding a gun to his head. This allusion to Goethe’s Werther (about a young man falling in love with an older married woman who didn’t love him back, and eventually committing suicide because of it) has led people to assume this piece is a musical confession of his unrequited love for Clara Schumann, and how it contributed to some private emotional turmoil. It does at least give a more human side to a composer who’s always being called a dull academic. And perhaps it was this personal aspect, and details and references to Clara and Robert, that kept him from publishing it right away. He wrote it around the same time as his first two quartets, but left it in a drawer for decades until deciding to come back and finish it. That at least explains why, overall, it’s somewhat more ‘direct’ than the denser textures of his late music.

The first movement has a lot of the “academic” moments I mentioned, where in following with Classical tradition, the entire sonata form is based on or derives from the opening. The C tolls in octaves on the piano, the strings play a somber theme with emphasis on a falling two note motif. Then, we go a semi-tone lower, which goes against classical form. The Romantic justification can come from the Werther-suicide image; like the character, the music is losing its sense of self. We modulate back to c minor, even with odd pizzicato notes outside of the key, and now hear a passionate wave of a melody again based on the two-note motif. That transitions into the softer and lyrical “B” melody, but even this melody derives from the motif. Again, this motif will be reused to an obsessive degree and re-contextualized for the mood in a way that would make Beethoven proud. The next section starts with a repeating Eb on the piano, again making me think of bells, that the strings start playing over. This acts as a pedal point, which in the 19th century signaled “old fashioned”, “Bach”, “church music” etc. and Brahms was criticized and called regressive/conservative a lot with his use of pedal points as an example of this ‘problem’. But from one of the letters he wrote to Clara, he said he knew she had a soft spot for pedal points. If you hear them in Brahms’ music, it’s probably because he knew Clara would like them. Anyway, we also get a kind of ‘heroic’ revision of the theme with heavy pounding chords and a scratchy viola. Into the ‘development’ section we have the lyrical version of the theme playing in canon in the strings over an unsettled rumble of another motivic pattern in the piano’s bass. Through all that turmoil, the last section opens with a much softer, more contemplative version of the lyrical theme. But the intensity comes back and collapses into the same somber atmosphere of the opening.

The second movement rushes in with a wide leap downward, which becomes the motif to be obsessed over here. More-so than the first movement does this scherzo show Brahms’ ‘heavy handedness’ and love for thick textures, full chords, and slamming into the piano’s bass registers. The strings interject with the rhythm, pulsating the motif, and soon the violin pulls a melody out of it all. And I think I hear a lot of “hunting horn” calls coming through open fifths, and I wonder if Brahms were trying to evoke “the hunt” with both horn calls and a kind of ‘galloping’ rhythm. Or maybe this is a kind of evocation of the woods which horn-calls were ubiquitous with in 19th century German music, like this scherzo is a wild and dark shaded Friederich painting that shows nature as a menacing and awesome thing. Or I could be speculating too much. The biggest surprise is how this movement ends in the major, with a triumph you wouldn’t expect early on, especially after the kind of devastating ending of the first movement.

This helps us into the slow movement, which I already said was in my short-list of ‘most beautiful pieces I’ve ever heard’. It starts with the cello singing the melody, a very long almost operatic melody, over the piano’s syncopated chords, with a lot of slight dissonances and leading tones that really push the emotional ‘longing’ in this music. At the end of the melody, the violin joins in a duet and it plays a slightly altered version of it. The cello has a rich accompanying part that mixes into the fabric. And then something magical happens; the viola joins the violin and cello for a trio on a new melody (in the Brahms fashion, the ‘new’ melody derives from the first one), while the piano’s texture changes into slow arpeggios. After that section, the rhythm gets a bit disjointed, and the harmonies a little more mysterious, segue-ways into another gorgeous magical part: another revision plays in the strings in call and response style, while scales in contrary motion on the keyboard emphasize and make the dissonances a little harsher, more paneful, and more poignient. I won’t keep detailing this movement since words aren’t enough. I’ll end with a mention that Brahms often used pizzicato to represent water, so my inner Romantic wants to think of this as a peaceful scene by a river, a serious contrast in the emotional intensity that we’ve heard so far.

The last movement opens in a way feels like Italian opera. The violin plays a melody over the piano – the right hand is playing a restless figuration that modulates like a Bach keyboard piece, while the left hand plays the beat and also emphasizes a three note motif which has to be a homage to Beethoven. Funny, I think if Brahms heard me say “this might be a Beethoven reference,” he’d treat me the way he treated critics of his first symphony, “of course it is! Any ass could see that!” Soon the full string section comes in, and again we get the dense textures and hyper-drama of the scherzo (along with the heavy-handedness). Through this section Brahms de-stabalizes the rhythm, but comes back to stability along with an easier and thinner section in the major. The development has the strings playing with and obsessing over, what else, but fragments of the opening melody. In its recap, the melody is played again in unison strings over a fiercely difficult etude looking passage on the piano made up of broken octaves. During this recap the instruments are again disrupted by complicated passagework that messes up the rhythm. After getting overwhelmed by the violence, Brahms again surprises us with a major key ending. But maybe it isn’t a surprise, maybe the scherzo was a foreshadowing. That’s the thing that keeps bringing me back to Brahms: everything that happens is more deliberate than you’d assume at first. If he presents an idea, it will not be left alone; it will return as an important component, and the whole structure is based on what Schoenberg would later call ‘developing variation’. From one melody, an entire piece can emerge.

Movements:

1. Allegro non troppo

2. Scherzo: Allegro

3. Andante

4. Finale: Allegro comodo

mikrokosmos: Brahms – Piano Quartet no. 3 in c minor (1875) I’m surprised that I haven’t covered this work yet. It’s been one of my favorites for a long time now…it was actually my introduction to Brahms. I was kind of overwhelmed by most of the music, so I didn’t really like the full quartet.…

0 notes