#reptile scute fossil

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Large Crocodile Scute Fossil – Diplocynodon – Eocene, Morocco

Offered for sale is a large fossilised crocodile scute, identified as belonging to the extinct genus Diplocynodon. This impressive specimen originates from Eocene-aged deposits in Morocco, representing an ancient relative of modern crocodiles that once thrived in subtropical freshwater environments.

Fossil Type:

Specimen: Crocodile Scute (Osteoderm)

Genus: Diplocynodon

A heavily armoured part of the dermal skeleton, typically located along the back or flanks

Geological Context:

Period: Paleogene

Epoch: Eocene

Age Range: ~56 to 34 million years ago

Depositional Environment: Fluvial and lacustrine (river and lake) systems typical of subtropical Eocene Morocco. These ecosystems were rich in crocodilians, turtles, and early mammals, with fine sediments preserving vertebrate remains well.

Morphological Features:

Large, bony scute with characteristic pitted texture and convex curvature

May show keel or central ridge depending on location in the body armour

Fossilised in mottled brown, grey, or ochre hues due to iron and mineral replacement

Scientific Importance:

Diplocynodon is an extinct genus of alligatoroid crocodilian known from both Europe and North Africa

These scutes help researchers understand crocodile evolution, biomechanics, and defensive adaptations during the Eocene

Scutes like this are commonly found detached from the skeleton and provide valuable data for species identification and palaeoecological reconstructions

Locality Information:

Morocco – a globally significant fossil locality for Eocene freshwater deposits, yielding crocodyliform remains alongside fish, turtles, and mammals

Authenticity & Display:

All of our fossils are 100% Genuine Specimens and come with a Certificate of Authenticity. This listing includes actual photographs of the specimen you will receive. Please refer to the photo for full sizing – the scale cube = 1cm.

This is a fantastic collector’s piece for anyone interested in fossil reptiles, Eocene ecosystems, or the evolution of crocodilians. A well-preserved and visually impressive fossil, ideal for educational display or private collections.

Own a real piece of Eocene life—an armoured fragment from a prehistoric crocodile over 40 million years old!

#Crocodile scute fossil#Diplocynodon fossil Morocco#Eocene crocodile armour#fossil crocodile plate#Eocene reptile fossil#authentic crocodilian fossil#Moroccan fossil croc#fossil osteoderm#reptile scute fossil#certified fossil scute#prehistoric croc fossil

0 notes

Text

Crystal Palace Field Trip Part 2: Walking With Victorian Dinosaurs

[Previously: the Permian and the Triassic]

The next part of the Crystal Palace Dinosaur trail depicts the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. Most of the featured animals here are actually marine reptiles, but a few dinosaur species do make an appearance towards the end of this section.

Although there are supposed to be three Jurassic ichthyosaur statues here, only the big Temnodontosaurus platyodon could really be seen at the time of my visit. The two smaller Ichthyosaurus communis and Leptonectes tenuirostris were almost entirely hidden by the dense plant growth on the island.

Ichthyosaurs when fully visible vs currently obscured Left side image by Nick Richards (CC BY SA 2.0)

Head, flipper, and tail details of the Temnodontosaurus. A second ichthyosaur is just barely visible in the background.

Ichthyosaurs were already known from some very complete and well-preserved fossils in the 1850s, so a lot of the anatomy here still holds up fairly well even 170 years later. They even have an attempt at a tail fin despite no impressions of such a structure having been discovered yet! Some details are still noticeably wrong compared to modern knowledge, though, such as the unusual amount of shrinkwrapping on the sclerotic rings of the eyes and the bones of the flippers.

———

Arranged around the ichthyosaur, three different Jurassic plesiosaurs are also represented – “Plesiosaurus” macrocephalus with the especially sinuous neck on the left, Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus in the middle, and Thalassiodracon hawkinsi on the right.

They're all depicted here as amphibious and rather seal-like, hauling out onto the shore in the same manner as the ichthyosaurs. While good efforts for the time, we now know these animals were actually fully aquatic, that they had a lot more soft tissue bulking out their bodies, and that their necks were much less flexible.

———

The recently-installed new pivot bridge is also visible here behind some of the marine reptiles.

———

Positioned to the left of the other marine reptiles, this partly-obscured pair of croc-like animals are teleosaurs (Teleosaurus cadomensis), a group of Jurassic semi-aquatic marine crocodylomorphs.

A better view of the two teleosaurs by MrsEllacott (CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Crystal Palace statues have the general proportions right, with long thin gharial-like snouts and fairly small limbs. But some things like the shape of the back of the head and the pattern of armored scutes are wrong, which is odd considering that those details were already well-known in the 1850s.

———

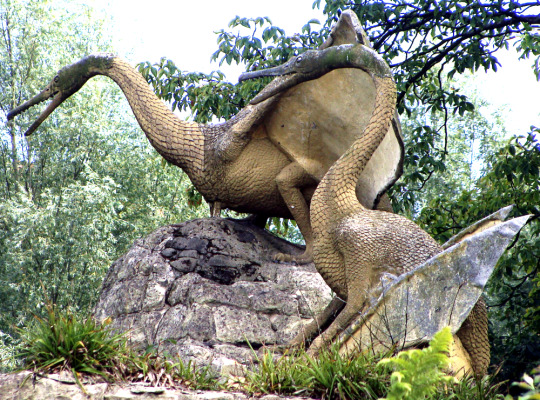

Finally we reach the first actual dinosaur, and one of the most iconic statues in the park: the Jurassic Megalosaurus!

Megalosaurus bucklandi was the very first non-avian dinosaur known to science, discovered in the 1820s almost twenty years before the term "dinosaur" was even coined.

At a time when only fragments of the full skeleton were known, and before any evidence of bipedalism had been found, the Crystal Palace rendition of Megalosaurus is a bulky quadrupedal reptile with a humped back and upright bear-like limbs. It's a surprisingly progressive interpretation for the period, giving the impression of an active mammal-like predator.

This statue suffered extensive damage to its snout in 2020, which was repaired a year later with a fiberglass "prosthesis".

———

Reaching the Cretaceous period now, we find Hylaeosaurus (and one of the upcoming Iguanodon peeking in from the side).

Hylaeosaurus armatus was the first known ankylosaur, although much like the other dinosaurs here its life appearance was very poorly understood in the early days of paleontology. Considering how weird ankylosaurs would later turn out to be, the Crystal Palace depiction is a pretty good guess, showing a large heavy iguana-like quadruped with hoof-like claws and armored spiky scaly skin.

It's positioned facing away from viewers, so its face isn't very visible – but due to the head needing to be replaced with a fiberglass replica some years ago, the original can now be seen (and touched!) up close near the start of the trail.

———

Two pterosaurs (or "pterodactyles" according to the park signs) were also supposed to be just beyond the Hylaeosaurus, but plant growth had completely blocked any view of them.

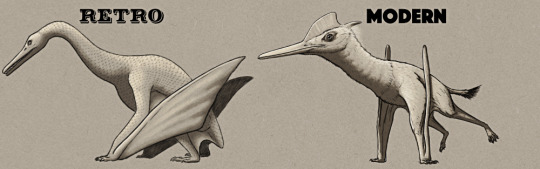

Although these two statues are supposed to represent a Cretaceous species now known as Cimoliopterus cuvieri, they were probably actually modeled based on the much better known Jurassic-aged Pterodactylus antiquus.

A second set of pterosaur sculptures once stood near the teleosaurs, also based on Pterodactylus but supposed to represent a Jurassic species now known as Dolicorhamphus bucklandii. These statues went missing in the 1930s, and were eventually replaced with new fiberglass replicas in the early 2000s… only to be destroyed by vandalism just a few years later.

(The surviving pair near the Hylaeosaurus are apparently in a bit of disrepair these days, too, with the right one currently missing most of its jaws.)

Image by Ben Sutherland (CC BY 2.0)

The Crystal Palace pterosaurs weren't especially accurate even for the time, with heads much too small, swan-like necks, and bird-like wings that don't attach the membranes to the hindlimbs. Hair-like fuzz had been observed in pterosaur fossils in the 1830s, but these depictions are covered in large overlapping diamond-shaped scales due to Richard Owen's opinion that they should be scaly because they were reptiles.

But some details still hold up – the individual with folded wings is in a quadrupedal pose quite similar to modern interpretations, and the bird-like features give an overall impression of something more active and alert than the later barely-able-to-fly sluggish reptilian pterosaur depictions that would become common by the mid-20th century.

(Much like the statues themselves, the "modern" reconstruction above is based on Pterodactylus rather than Cimoliopterus)

———

The last actual dinosaurs on this dinosaur trail are the two Cretaceous Iguanodon sculptures. At the time of my visit they weren't easy to make out behind the overgrown trees, and only the back end of the standing individual was clearly visible.

Named only a year after Megalosaurus, Iguanodon was the second dinosaur ever discovered, and early reconstructions depicted it as a giant iguana-like lizard.

The Crystal Palace statues depict large bulky animals, one in an upright mammal-like stance and another reclining with one hand raised up. (This hand is usually resting on a cycad trunk, but that element appeared to be either missing or fallen over when I was there.)

Famously a New Year's dinner party was held in the body of the standing Iguanodon during its construction, although the accounts of how many people could actually fit inside it at once are probably slightly exaggerated.

A clearer view by Jim Linwood (CC BY 2.0)

Considering that the skull of Iguanodon wasn't actually known at the time of these sculpture's creation, the head shape with a beak at the front of the jaws is actually an excellent guess. The only major issue was the nose horn, which was an understandable mistake when something as strange as a giant thumb spike had never been seen in any known animal before.

(The fossils the Crystal Palace statues are based on are actually now classified as Mantellisaurus atherfieldensis, but the "modern" reconstruction above depicts the chunkier Iguanodon bernissartensis.)

———

Image by Doyle of London (CC BY-SA 4.0)

I also wasn't able to spot the Cretaceous mosasaur on the other side of the island due to heavy foliage obscuring the view.

Depicting Mosasaurus hoffmannii, this model consists of only the front half of the animal lurking at the water's edge. It's unclear whether this partial reconstruction is due to uncertainty about the full appearance, or just a result of money and time running out during its creation.

The head is boxier than modern depictions, and the scales are too large, but the monitor-lizard like features and paddle-shaped flippers are still pretty close to our current understanding of these marine reptiles. It even apparently has the correct palatal teeth!

Next time: the final Cenozoic section!

#field trip!#crystal palace dinosaurs#retrosaurs#i love them your honor#crystal palace park#crystal palace#ichthyosaur#plesiosaur#teleosaurus#crocodylomorpha#marine reptile#megalosaurus#theropod#hylaeosaurus#ankylosaur#iguanodon#ornithopoda#ornithischia#dinosaur#pterodactyle#pterodactylus#pterosaur#mosasaurus#mosasaur#paleontology#vintage paleoart#art

478 notes

·

View notes

Text

World Tomistoma Day 2023

Although I find the concept of a "World Day of" generally stupid, I believe that on the matter of endangered species, it can be a very meaningful speaker.

Tomsen, a female T. schlegelii at BioParc Fuengirola (Spain)

Today, August 5th, an initiative of the Crocodile Specialist Group (CSG) together with the "Tomistoma Task Force" is trying to draw attention to this poorly known and misunderstood species.

For those of you who don't know this animal, Tomistoma schlegelii, commonly known as Malayan false gharial is a longirostrine crocodilian that inhabits forested freshwater lakes, slow-moving rivers and swamps of Peninsular Malaysia, Borneo, Sumatra and possibly Java, feeding on diverse prey (From invertebrates to monkeys, small deer, birds and reptiles, with fish constituting the bulk of its diet), and although it is not a particularly aggressive species, there are several records of attacks on humans, with at least one fatal confirmed.

Tomistoma schlegelii devouring a female proboscis monkey (Nasalis larvatus). Inspired by Galdikas et al. 1985 (Illustration made in 2022)

It is characterized by a long narrow snout which blends gradually with the base of the head/skull. Two rows of very small, barely distinct post-occipital scutes. Nuchal scales continuous with dorsal scutes and are almost indistinguishable. They are generally brown in color, with dark bands, including blotches and bands on snout and jaws.

But what makes this species really interesting are two particularities : Its enormous size and its ínteresting taxonomic affinities:

a) Size: It is not uncommon for Tomistoma males to reach lengths of 4 m today, but skeletal remains (Mainly skulls) indicate that we could be (Although improbably) in the presence of one of the candidates for the largest crocodylian species in the world .

In their 2008 study, R. & N. Whitaker noted that the longest skulls in the world belonged to Tomistoma (One at Munich Museum at 81.5 cm; another at the AMNH at 76.5 cm ...) with the British Museum specimen taking the lead with an incredible 84 cm (Leaving all other species behind).

However, observations made on Tomistomas in captivity at the Samut Prakarn Crocodile Farm (Bangkok) and on some wild specimens, determined that the HL:TL ratio was 1:6.4 for the species; and therefore, the British Museum specimen would have measured about 5.38 m in life, certainly a giant but far from the monstrous sizes of some salties (Crocodylus porosus).

The British Museum specimen. George Craig © (In the second photo, you can compare the size with C. porosus and G. gangeticus large specimens)

b) Uncertain affinities: Tomistoma is the last survivor of an old lineage that originated about 40-50 mya ago. This has made many authors wonder: where does this species fit in the evolutionary tree of crocodylia? And well... it's complicated.

T. schlegelii has long been considered to be a member of the Crocodylidae ( Brochu 2003). Much of the analysis has focussed on skeletal attributes, often constrained that way to allow comparison with fossil material, but there is supporting evidence from soft anatomy as well (Frey et al. (1989) , Endo et al.(2002)...)

But now begins the tricky part : Molecular analyses place Tomistoma as a Gavialid.

( White and Densmore 2001; Janke et al. 2005;McAliley et al. 2006, Roos et al. 2007; Man et al. 2011...) Although some of these studies have been criticized for their methodology, it is clear that it cannot be ignored that they all reach the same conclusion.

Likewise, there are important discrepancies about the times and periods in which both families appear/diverge, so the debate is not yet definitely closed.

Tomistoma are considered vulnerable by the IUCN Red List, nonetheless, it remains possible that T. schlegelii may qualify as Endangered in the future due to ongoing habitat loss and degradation, particularly Malaysia, so this day is still important to spread the word about the species.

I have only been able to enjoy these animals live once, at the BioParc in Fuengirola, Málaga (Spain) where they keep a trio of three adult specimens: Two females (Montse and Tomsen) and a huge male (René, affectionately nicknamed "Pinocho"). This Zoo is the only one in Spain that houses Tomistomas and has achieved the titanic task of their reproduction in captivity.

René, the huge male at BioParc Fuengirola. Video by me.

#zoology#animals#reptiles#crocodiles#nature#crocodilians#wildlife#science#conservation#endangered species#endangered animals

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vertebrates 2/24

today in verts we talked about turtles. apparently, turtles have a lot going on that make them super freaky when it comes to their sister taxa.

Lets start with this question: What exactly ARE turtles?

Order Testundies

Sauropsida

Only 361 alive species across 14 families

Instantly recognizeable because of shell

What is so weird about them?

Turtles have anapsid skulls, and are the only amniotes (vertebrates that lay amniotic eggs) with this condition

What is an anapsid skull?

Anapsid skull is a type of Temporal Fenestration.

Temporal fenestrae are openings in the skull that are behind the eyes which allow movement of the lower jaw.

Anapsid means no fenestra, so the only opening are the orbits (eye holes) and nostrils. (turtles)

Synapsid means single fenestra, which is the lower fenestra. (this is what humans have, including mammals and mammal like reptiles)

Diapsid means two fenestrae, which are upper and lower. (lepidosaurs and archosaurs [lizards/snakes, crocodiles/dinosaurs/birds, respectively])

The big question with turtles anapsid skulls is: were they always this way, or did they lose their synapsid/diapsid condition?

The answer comes from the fossil record. In the past we can see that the synapsid condition appears in turtles once in the synapsid lineage, and the diapsid condition appears once in the sauropsid lineage. This proves that turtles evolved to have the anapsid condition in their skull, making it a secondary condition.

2. Modern turtles lack teeth

Jaws of turtles are surrounded by a hard keratinous sheath. Keratin is the same thing our fingernails are made of, but this is a much thicker and denser makeup of it. It has a very sharp beaklike shape that is good for cutting plant and animal material. This is good, because most turtles are omnivores or carnivores.

There are some turtles that are herbivores, but these are usually stenophagous (specific diet) and only eat a certain food in general.

3. Modern turtles are divided into two groups

Cryptodira

262/361 species belong here

head retracts as a vertical S-bend

known as "S-necked" turtles

found in fresh water, marine, and terrestrial

Pleurodira

99/361 species belong here

head retracts by bending horizontally into shell

known as "side-necked" turtles

All freshwater

4. Turtle Shells

Formed by 3 elements

Endoskeleton (spine, ribs, clavical)

Exoskeleton (dermis)

Epidermis (keratinous scutes)

Two halves of shell are:

carapace (top)

plastron (bottom)

The carapace is covered in scutes, which are the individual outlined shapes on top. Under the carapace is bone, dermal and endochondral. Dermal bone is the lower layer and endochondral is the upper layer.

Now lets talk about the types of shells:

Hinged shell

Hinge in the middle that allows the plastron to close the front and back opening of the shell

OR

Double hinge on either end

Weird shells

Lack keratinous scutes and bony plates are reduced

OR

Lack keratinous scutes and the bony plates are replaced by thousands of dermal bone

Evidence of turtles date back to the triassic period

5. How do turtles breathe?

Before getting into this, it is important to note that during development, turtles ribs fuse to their shell, which is good because it reinforces their shell, but it also changes how they breathe in comparison to other amniotes.

Amniotes use a process called costal ventilation, which is where when the lungs expand with air, the ribcage moves with it, and then when the lungs exhale, the ribcage goes back to normal. Because turtles cannot move their fused ribcage, they had to adapt a new way of breathing.

Instead of moving their lungs, turtles move their guts!

when the turtle inhales, the lungs expand. a few muscles and membranes surrounding the guts stretch and allow the lungs to push their gut downward

when the turtle exhales, the muscles and membranes push the guts back up towards the deflating lungs

This causes problems for many turtles functions.

when a turtle is fully retracted inside of its shell, it cannot breathe and must hold its breath

Sea turtles cannot breathe when they walk. they must walk, then take a break to breathe

Most turtles can breathe when they walk due to their diagonal gait. They walk with their left back foot and right front foot, and then right back foot and left front foot.

Aquatic turtles must come up for air, which makes them vulnerable to predators. Luckily, they can hold their breath for a very long time.

There is another way for turtles to breathe which is honestly pretty funny. I'm being completely serious when I tell you, some of them can breathe through their buttholes. They literally open their butthole over and over and pump water in and out and are able to diffuse oxygen from the water. This is really good for them to not have to surface, especially for turtles who get trapped under ice in colder months.

6. Turtle reproduction!

Lay on average 4-5 eggs, or even up to 100 eggs!

Almost no parental care, layed egg and then you are on your own!

Temperature dependent sex determination (TSD):

temperature determines sex of turtle. (Humans are the organism with gender, everything else is sorted by sex)

changes of even 3-4 degrees can determine sex

Lower temps mean males while higher temps mean females

Challenges of reproduction:

Few eggs and slow maturity mean turtles do not reproduce fast enough to combat endangerment

Pet trading, food collection, medicine, habitat destruction, and pollution all affect turtles

Global warming effects TSD and creates a disproportionate ratio of sexes which affects future reproduction as well

Over half of the 361 species are endangered

In conclusion, turtles are funky. We need to protect them to ensure they stay on our earth!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Discover the Fascinating History of Crocodile Fossils

Crocodile fossils offer a glimpse into the incredible history of these ancient reptiles, which have existed for over 200 million years. Found across the globe, these fossils help us understand their evolution and survival through changing climates. For more information visit: https://www.fossilageminerals.com/products/crocodile-scute-armor-dermal-plates-teeth-fossil-bones-dinosaur-age-hell-creek-mt-04nqq252

0 notes

Photo

Desmatosuchus

Desmatosuchus is an extinct genus of archosaur belonging to the Order Aetosauria. It lived during the Late Triassic.

Desmatosuchus was a large quadrupedal reptile upwards of 4.5 m (15 ft) to 6 m (20 ft) in length and 280 kg (620 lb) in weight. Individuals of Desmatosuchus were heavily armored. The carapace was made up of two rows of median scutes surrounded by two more rows of lateral scutes. Desmatosuchus fed by digging up soft vegetation...

Read more: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Desmatosuchus

Images: Fossil skeleton at Petrified Forest National Park by Frank Kovalchek CC, Jeff Martz | NPS

#fossils#science illustration#prehistoric#reptile#aetosaur#national parks#public lands#nature#north america#animals#science

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

The apex killer of the snowy Northern Tundra, Lasiosauropteryx are a large-sized, ancient species of a mysterious lineage of winged Therapsid. Science often tells that Therapsids were the stock that gave rise to modern and prehistoric mammals and was considered to be the lineage that kept gradually evolving increasingly mammalian features, hence the name “mammal-like reptiles”, and much like the weird looking creatures of the past, Lasiosauropteryx is no different. Lasiosauropteryx is a strange creature, as they seem to be the cut off where birds and mammals split down the evolutionary train, taking on the aspects of both Bird, Reptile and Mammal. They are winged, and in addition to the glandular skin on its body covered in fur found in most modern mammals, this modern synapsid along with its now extinct relatives possess a variety of modified skin coverings, including: Osteoderms, a bony armor embedded in the skin around the feet and scutes, a protective structure of the dermis often with a horny covering on the tail.

Their wings are also strange. In evolution, Aerial locomotion first began in non-mammalian haramiyidan cynodonts, with creatures like Arboroharamiya, Xianshou, Maiopatagium and Vilevolodo all bearing exquisitely preserved, fur-covered wing membranes that stretch across the limbs and tail. Their fingers are elongated, similar to those of bats and colugos and likely sharing similar roles both as wing supports and to hang on tree branches. Much like these creatures, Lasiosauropteryx possess fur-covered wing membranes similar to that of Bats instead of modern or ancient birds. As in other mammals, and unlike in birds, the radius is the main component of the forearm. Lasiosauropteryx have five elongated digits, which all radiate around the wrist. The thumb in Lasiosauropteryx points forward and supports the leading edge of the wing, and the other digits support the tension held in the wing membrane. The second and third digits go along the wing tip, allowing the wing to be pulled forward against aerodynamic drag, without having to be thick as in pterosaur wings. The fourth and fifth digits go from the wrist to the trailing edge, and repel the bending force caused by air pushing up against the stiff membrane. Due to their flexible joints, Lasiosauropteryx are more maneuverable and more dexterous than gliding mammals.However though it has wings. Lasiosauropteryx prefer to glide despite being capable of flying in the air. When on the ground however, Lasiosauropteryx can only crawl awkwardly similar to that of the locomotion of grounded bats, making lateral gaits (the limbs move one after the other) when moving slowly but being capable of moving with a bounding gait (all limbs move in unison) at greater speeds, the folded up wings being used to propel them forward, giving the creature the ability of moving 10mpsThe wings of Lasiosauropteryx are much thinner and consist of more bones than the wings of birds, allowing them to maneuver more accurately than the latter, and fly with more lift and less drag. By folding the wings in toward their bodies on the upstroke, they save 35 percent energy during flight, However the membranes are delicate, tearing easily, but can regrow, and small tears heal quickly. This is because the patagium which is the wing membrane stretched between the arm and finger bones, and down the side of the body to the hind limbs and tail, consists of connective tissue, elastic fibers, nerves, muscles, and blood vessels. The muscles keep the membrane taut during flight. The most striking feature of the creature is their thick, shaggy coat of fur which covers a majority of the body. As winter approaches their coats become incredibly dense and spreads to cover almost the entire animal. Flight with a full winter coat is difficult and only undertaken in times of need. During the summer season they shed their winter coats, leaving their body covered in a much finer coat of fur, and leaving the hindquarters and upper back exposed. Coloration for this creature usually coincides with it main set territory. It has gray fur covering most of its body, with dark blue accents at the tips of the fur on its head, wings, and tail. Hair has its origins in the common ancestor of mammals, the synapsids, about 300 million years ago. It is currently unknown at what stage the synapsids acquired mammalian characteristics such as body hair and mammary glands, as the fossils only rarely provide direct evidence for soft tissues. However much like in mammals, the hairs of Lasiosauropteryx are all connected to nerves, and so the fur also serves as a transmitter for sensory input. Lasiosauropteryx are the dominant predator of their respected habitats, they are very large compared to most creatures heavy despite being a flighted creature, which is a good advantage for it when it comes to fighting aggressors physically: despite their size, they’re shockingly agile and possess a glint of unpredictability in their fighting style taken full advantage tot heir erratic behavior to aid it in a fight. It should also be noted that despite all the encounters people have had with this beast, NO ONE KNOWS WHERE THESE THINGS CAME FROM. When they were first discovered in the northern parts of New America, it was thought to be a elaborate hoax, as these creatures with all their weird attributes look like something straight out of European legend. And much like their fairy tail cousins, these creatures are, astonishingly and disturbingly aggressive Lasiosauropteryx are ferocious predators that will not back down from a fight until they kill the target or die trying. As a result of their size, Lasiosauropteryx dominate the ecosystems in which they live. They are carnivores, although they have been considered as eating mostly carrion, they will frequently ambush live prey with a surprisingly stealthy approach. When suitable prey arrives near a creatures chosen ambush site, it will suddenly charge at the animal at high speeds and go for the underside or the throat. Despite popular belief however, Lasiosauropteryx do not deliberately allow prey to escape with fatal injuries but try to kill prey outright using a combination of lacerating damage and blood loss. They have been recorded as killing Super Mutants within seconds, and observations of the creature tracking prey for long distances are likely misinterpreted cases of prey escaping an attack before succumbing to infection. Lasiosauropteryx eat in a manner similar to crocodiles, by tearing large chunks of flesh and swallowing them whole while holding the carcass down with their forelimbs. For smaller prey up to the size of a goat, their loosely articulated jaws, flexible skulls, and expandable stomachs allow them to swallow prey whole. Undigested vegetable contents of a prey animal’s stomach and intestines are typically avoided. Copious amounts of red saliva the creature produces help to lubricate the food to make it easy to swallow, but swallowing is still a long process (15–20 minutes to swallow a super mutant).

#What is sought is most often found if it is truly sought: World Information#Fallout#Fallout 4#Fallout AU#fo4#Fallout World Building#Fallout 4 World Building

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Super Croc, gigantic crocodile from Cretaceous period

Paleontologist Paul Serrano and his team were searching near Gadoufaoua, Niger in Africa. During the search, the team came across huge pieces of fossilised bones, and recognised them as the bones from an extinct crocodile species. It was so large that it wound up as the first animal nicknamed a “Supercroc”.

French paleontologists had found similar bones including skull fragments some 30 years before Serrano's team. They named the creature Sarcosuchus imperator (flesh crocodile emperor), but before the expedition by Serrano's team in 1997 little was known about this ancient predator.

As soon as the team started digging they found massive jaw bones, each as long as some members of the team. The jaws were about 6 feet (1.8 metres) in length, and huge crushing teeth were a testament that this giant crocodile used them to tear away dinosaur flesh. They are thought to have existed during the Middle Cretaceous era, about 110 million years ago. The skull fragments found were put together, and it was estimated that they probably grew up to 40 feet (12 metres) in length, and weighed around 8 tons (17,500 pounds).

The team found skull fragments, intact jaw bones, vertebrae, limb bones, and armour plates (scutes) about 30 cms long which used to run over the whole body of this species. This assemblage of bones helped the scientists to get a clear picture of about half of the giant crocodile's skeleton. According to Serrano, "The new material gives us a good idea of hyper-giant crocodiles. There's been rampant speculation about what they looked like and where they fit in the croc family tree." There are annual growth rings on the scutes, and from this the scientists calculated the croc's age to be about 50 to 60 years.

Sarcosuchus does not share the same reptile family tree as modern day crocodiles, which consists of caimans, gharials, alligators and crocodiles. "It's not a modern croc, but they share an early common ancestor, " as per Larsson, a member of Serrano's team.

In the early Jurassic, after the split of early crocodilians into separate land based and marine based species, Sarcosuchus appeared. They were probably ambush hunters, and were adept in surprising their preys with little chance of defense. Like the modern day Indian gharials, this ancient predator had upwardly tilted eye sockets, which helped them to hide their huge body underwater while waiting for the unsuspecting preys.

The other distinguishing feature is the round bony protrusion at the tip of its snout known as bulla, another common feature present in modern gharials. Larsson thinks that just like the gharials use the muscles around bulla to emit various sounds during mating, the ancient croc must have used it to emit mating calls. The bulla could also have enhanced their sense of smell and gave them an edge over other predator species.

Other relatives of this animal have been recognized in fossil deposits since this initial discovery, expanding the range of large crocodile-like animals from the end-Cretaceous extinction back into the Jurassic..

Source:

http://on.natgeo.com/1CsQ9ps

http://bit.ly/1EYMUUY https://www.livescience.com/59697-super-croc-with-t-rex-teeth-ate-dinosaurs.html

--RB.[_

_](https://www.facebook.com/TheEarthStory/photos/pcb.857650794295966/857650627629316/?type=3&theater#)

628 notes

·

View notes

Text

In an unexpected twist it turns out alligators can regrow their tails too

https://sciencespies.com/nature/in-an-unexpected-twist-it-turns-out-alligators-can-regrow-their-tails-too/

In an unexpected twist it turns out alligators can regrow their tails too

Cornered by a dangerous predator, a gecko can self-amputate its still twitching tail, creating a fleeting moment of distraction – a chance for the lizard to flee with its life.

Small reptiles such as geckos and skinks are well known for this remarkable ability to sacrifice and then rapidly regrow their tails. Now, to scientists’ surprise, it turns out that much larger alligators can regrow theirs too. But only while they’re young.

Juvenile American alligators (Alligator mississippiensis) can regrow up to 18 percent of their total body length back. This is about 23 cm or 9 inches of length.

What’s really cool is this regrowth appears to occur via a mechanism we’ve not seen before.

By imaging and dissecting the tail regrowth, researchers from Arizona State University (ASU) found alligators do this quite differently from the other animals we know that can regenerate their appendages.

Regrown tails are visibly identified by scale coloration, dense scale patterning, and lack of dorsal scutes. pic.twitter.com/adFdXs6rIY

— Cindy Xu (@xucindy) November 19, 2020

As far as regrowing body parts goes, amphibious axolotls are the champions of regeneration amongst land animals with internal skeletons.

If injured, they can reform a segmented skeleton, complete with muscles that differ along their height – distinguishing top from bottom.

Regrown lizard tails do not have a segmented skeleton, but lizards do reform muscles – although they look uniformly the same, with no variation in topside structure compared to the bottom.

This may be because regenerating appendages is physiologically expensive, and in smaller lizards has been shown to reduce overall growth rate.

Alligators, it seems, don’t even bother re-growing muscles at all.

“Clearly there is a high cost to producing new muscle,” said ASU animal physiologist Jeanne Wilson-Rawls.

The team believes that even a muscle-less extra bit of tail must give these dangerous predators an edge in their murkily watered homes.

Unlike lizards, they can’t self-amputate – their tail loss usually results from trauma inflicted by territorial aggression, or cannibalism from larger individuals.

Damage from human interactions, like motor blade damage have also been recorded.

The anatomical difference between original and regenerated tail. (Arizona State University)

The connective-tissue alligators replace skeletal muscle with is more like the wound repair you would see in the tuatara or in mammal wound healing, the team explains.

“The regrown alligator tail is supported by an unsegmented cartilage tube rather than bone… lacked skeletal muscle and featured scar-like connective tissue populated with nerves and blood vessels,” ASU cellular biologist and first author of the research Cindy Xu explained on Twitter.

“Regrown tails from juvenile American alligators exhibit features of both regeneration and wound repair.”

But regrowth of cartilage, blood vessels, nerves and scales is similar to what is seen in lizards.

“Future comparative studies will be important to understand why regenerative capacity is variable among different reptile and animal groups,” said Xu.

It also may take them considerably longer to regrow their missing bits. While skinks can do it in as little as six months, a related crocodilian, the black caiman (Melanosuchus niger) takes up to 18 months to reform their tails.

Alligators are an ancient lineage of reptiles, who shared a common ancestor with birds around 245 million years ago, back when non-avian dinosaurs dominated the Earth.

There’s fossil evidence of an ancient crocodilian from the Jurassic period that also had a regenerated tail.

This “raises the question of when during evolution this ability was lost. Are there fossils out there of dinosaurs, whose lineage led to modern birds, with regrown tails?” ASU biomedical scientist Kenro Kusumi questions.

“We haven’t found any evidence of that so far in the published literature.”

The team notes so far they’ve only been able to observe the end product of tail regenerations in alligators.

Given that they are a threatened species, further studies on how this process works may be challenging, but could provide some useful information.

“If we understand how different animals are able to repair and regenerate tissues, this knowledge can then be leveraged to develop medical therapies,” said ASU anatomist Rebecca Fisher.

This research was published in Scientific Reports.

#Nature

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Animal Crossing Fish - Explained #28

Brought to you by a marine biologist who likes turtles just as much as literally everyone...

Fish I’ve Covered: Click Here

So today we will be covering another marine reptile that graced the ocean meta during the Cretaceous period. That’s right, we are covering the biggest turtle that ever lived - Archelon:

So, unlike the Ichthyosaurs and Plesiosaurs, we still have sea turtles living on Earth. Unfortunately, every single one of them is ENDANGERED, according to the US ESA (Endangered Species Act), so probably not for long and that’s not cool. They are threatened by pretty much everything you can think of, from habitat loss, to climate change, to ocean plastic and light pollution, and yes, even hunting. Sea turtles got it bad. Archelon, by the end of its reign, was also dealing with some of these issues.

So, let’s talk about Archelon for a bit. The species name is Archelon ischyros and, as I’ve said, it was the largest turtle to ever grace our planet. At 15 ft (4.6 m), it was HUGE in comparison with today’s biggest turtle, the Leatherback sea turtle at only 7.2 feet (2.2m) for the biggest specimens. The fossil in AC doesn’t really show you the magnitude of how big this turtle was, so here’s the one at the Yale Peabody Museum:

Archelon and other massive sea turtles of the past belong to a separate family (Protostegidae) within the sea turtle super family. Unlike most sea turtles you can think of, Archelon and friends didn’t have hard shells with bony scutes, but rather had leathery carapaces like today’s Leatherback sea turtle and reduced plastrons (underside of the “shell”). But like their cousins, Archelon also had a pronounced beak it more than likely used to hunt and crush mollusk, crustacean, and soft-bodied prey. Here’s a prehistoric reconstruction of what Archelon may have looked like, artist Dmitry Bogdanov :

So, we didn’t talk about this when we covered the Plesiosaur and the Ichthyosaur, but those two had live birth, which was paramount in their survival. Yeah. Reptiles. That had live birth like mammals do. Not as unlikely as you think, considering some species of shark and bony fish also have live birth to this day. You see, every adaptation an animal has incurs a cost somewhere. Gestating babies inside the mother of a species puts a lot of strain on the mother and limits the number of offspring that can be born at a time. However, laying eggs puts the babies in danger of environmental factors and predation. Sea turtles, like a lot of things that lay eggs, lay them and then leave. There is very minimal parental care and of thousand eggs laid, perhaps 1 will make it to adulthood. Those are crappy odds, but that’s how a lot of animals do things. When things are stable, this is just fine. However, when the climate and, subsequently, the habitat changes, that’s when things aren’t so good.

Like all turtles, it is suspected that Archelon had to come up onto beaches to nest. Back during the Cretaceous, huge swaths of North America were underwater (called the Western Interior Seaway), and this is where Archelon lived. It’s suspected as the climate cooled and water was frozen at the poles, the seaway closed, limiting where Archelon could live and nest until it eventually went extinct. This is kind of happening to sea turtles right now, except their nesting sites are being trashed by people. Disturbance, light pollution, plastic pollution, and egg-collection are really hitting sea turtles hard, and the miracle of getting 1 out of 1000 hatchlings to adulthood is becoming impossible. So, uh, let’s start doing more of that recycling thing, okay?

And there you have it. Fascinating stuff, no?

#animal crossing#ac: new horizons#archelon#sea turtle#fossil#science in video games#animal crossing fish explained

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

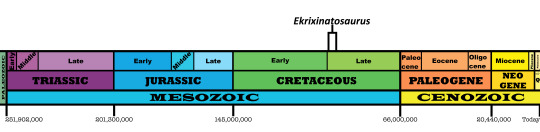

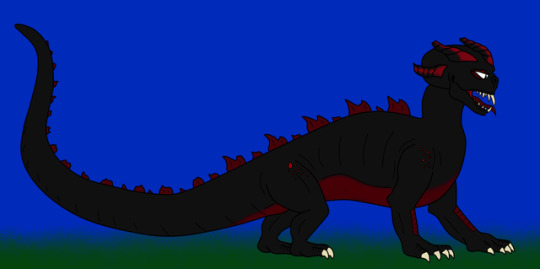

Ekrixinatosaurus novasi

By Ripley Cook

Etymology: Reptile born of an Explosion

First Described By: Calvo et al., 2004

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Ceratosauria, Neoceratosauria, Abelisauroidea, Abelisauridae, Carnotaurinae, Brachyrostra

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: Between 100 and 97 million years ago, in the Cenomanian of the Late Cretaceous

Ekrixinatosaurus is known from the Candeleros Formation of Neuquén, Argentina

Physical Description: Ekrixinatosaurus is a typical, large Abelisaurid, with a similar body shape to other members of the group - a thick trunk, long flexible tail, robust hindlimbs, barely any forelimbs, a thick neck, and a boxy head. It was covered in scutes and scales all over its body, and probably had no feathers at all. Compared to other Abelisaurids, Ekrixinatosaurus had a very large head and even more robust limbs, allowing it to turn quicker than other theropods of its size. This was important, as it lived in an environment with many different large sauropods. However, its hind limbs were also shorter than relatives, indicating that it couldn’t run particularly fast. Compared to other Abelisaurids, its skull was very short and deep, sort of like the Pug of Abelisaurs; the jaw also curved upward, giving it the weird appearance of being smiling all the time. It was about 7.4 meters long, making it only somewhat smaller than the largest known abelisaurid (Carnotaurus at 7.8 meters long).

Diet: Ekrixinatosaurus would have eaten large herbivores in its environment, especially sauropods; though any medium to large sized animal would have been on the menu.

Behavior: Ekrixinatosaurus would have spent much of its time hunting prey, using its legs to maneuver through the environment to chase its large targets, and corner them to where they can’t escape. As such, Ekrixinatosaurus probably spent the majority of its time in the more arid parts of its environment, rather than the swampy bits. It’s possible that Ekrixinatosaurus would hunt in family groups to take down bigger prey, but there isn’t fossil evidence either way on that score. They probably would have also taken care of their young.

By Scott Reid

Ecosystem: Ekrixinatosaurus lived in the Candeleros Formation of South America, which is a fun coincidence, because yesterday’s dinosaur did too! This was a braided river system, with a wide variety of swamps and very rich soil, and extensive sand deposits around the swamp area. Many fish, frogs, tuataras, turtles, snakes, and early mammals lived in this habitat, both in the wet swamp area and the more semi-arid landscape around it. Along with Ekrixinatosaurus, there were many other dinosaurs such as the very large Giganotosaurus which would have probably eaten Ekrixinatosaurus; the small fishing raptor Buitreraptor; a mysterious Coelurosaur Bicentenaria, an Alvarezsaurid Alnashetri, a probable Elasmarian, and many large sauropods for Ekrixinatosaurus to hunt - the Titanosaur Andesaurus and also Diplodocoids such as Limaysaurus, Nopcsaspondylus, and Rayososaurus.

Other: Ekrixinatosaurus was an Abelisaurid, it actually showcases how large-bodied Abelisaurids evolved before the huge Carnosaurs died out mid-way through the late Cretaceous; previously, hypotheses indicated that as the large Carnosaurs went extinct, the Abelisaurids “took their place”; but clearly that story is more complicated than it used to appear.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Bonaparte, J. F., F. E. Novas, R. A. Coria. 1990. Carnotaurus sastrei Bonaparte, the horned, lightly built Carnosaur from the Middle Cretaceous of Patagonia. Contributions in Science, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. 416.

Calvo, J. O., D. Rubilar-Rogers, and K. Moreno. 2004. A new Abelisauridae (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from northwest Patagonia. Ameghiniana 41(4):555-563

Grillo, O. N., R. Delcourt. 2016. Allometry and body length of abelisauroid theropods: Pycnonemosaurus nevesi is the new king. Cretaceous Research 69: 71.

Leanza, H.A.; S. Apesteguia; F.E. Novas, and M.S. De la Fuente. 2004. Cretaceous terrestrial beds from the Neuquén Basin (Argentina) and their tetrapod assemblages. Cretaceous Research 25. 61–87.

Novas, F. E., F. L. Angolín, M. D. Ezcurra, J. Porfiri, J. I. Canale. 2013. Evolution of the carnivorous dinosaurs during the Cretaceous: The evidence from Patagonia. Cretaceous Research 45: 174.

Sánchez, María Lidia; Susana Heredia, and Jorge O. Calvo. 2006. Paleoambientes sedimentarios del Cretácico Superior de la Formación Plottier (Grupo Neuquén), Departamento Confluencia, Neuquén (Sedimentary paleoenvironments in the Upper Cretaceous Plottier Formation (Neuquen Group), Confluencia, Neuquén). Revista de la Asociación Geológica Argentina 61. 3–18.

Valieri, J., R.D.; Porfiri, J.D.; Calvo, J.O. (2011). "New information on Ekrixinatosaurus novasi Calvo et al. 2004, a giant and massively-constructed Abelisauroid from the "Middle Cretaceous" of Patagonia". In Calvo, González, Riga, Porfiri and Dos Santos (eds.). Paleontología y dinosarios desde América Latina (PDF). pp. 161–169.

Wang, S., J. Stiegler, R. Amiot, X. Wang, G.-H. Du, J. M. Clark, X. Xu. 2017. Extreme Ontogenetic Changes in a Ceratosaurian Theropod. Current Biology 27 (1): 144 - 148.

Wichmann, R. 1929. Los Estratos con Dinosaurios y su techo en el este del Territorio del Neuquén (“The dinosaur-bearing strata and their upper limit in eastern Neuquén Territory”). Dirección General de Geología, Minería e Hidrogeología Publicación 32. 1–9.

#Ekrixinatosaurus novasi#Ekrixinatosaurus#Ceratosaur#Dinosaur#Abelisaurid#Dinosaurs#Palaeoblr#Carnivore#Theropod Thursday#South America#Cretaceous#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature#factfile

336 notes

·

View notes

Photo

RARE: Turtle Exoskeleton Fossil – Barton Beds, Eocene, Whitecliff Bay, Isle of Wight UK

This listing features a rare fossilised turtle exoskeleton fragment, sourced from the Barton Beds at Whitecliff Bay, Isle of Wight, UK. This specimen dates to the Eocene Epoch, making it over 40 million years old and a significant piece of the UK’s palaeontological heritage.

Fossil Type:

Specimen: Turtle Exoskeleton (Shell fragment – likely carapace or plastron)

Represents a chelonian (turtle or tortoise) from the Eocene vertebrate assemblage of southern England

Geological Context:

Period: Paleogene

Epoch: Eocene

Stage: Bartonian (~41.3 to 38 million years ago)

Formation: Barton Group (formerly part of the “Barton Beds”)

Depositional Environment: Coastal lagoon and estuarine settings. The Barton Beds were laid down in a warm, subtropical marine and marginal marine environment rich in vertebrate and invertebrate fossils.

Morphological Features:

Curved or slightly flattened dermal bone typical of chelonian shell fragments

Surface may show granular texture or faint impressions of scute boundaries

Brown-grey fossilisation with natural wear and mineralisation from estuarine clays

Scientific Importance:

Fossil turtle material from the Barton Beds is rare and valuable for understanding Eocene coastal ecosystems in Britain

Specimens like this may be attributable to genera such as Trionyx or other soft-shelled or hard-shelled turtle lineages found in European Eocene sites

These fossils help reconstruct the palaeobiogeography of marine reptiles in the early Cenozoic

Locality Information:

Whitecliff Bay, Isle of Wight, UK – a historically significant fossil site with well-exposed Barton Beds yielding both marine and terrestrial Eocene fossils. A known locality for rare turtle remains, crocodile teeth, and fish fossils

Authenticity & Display:

All of our fossils are 100% Genuine Specimens and are provided with a Certificate of Authenticity. The photographs show the actual fossil for sale. Please see the photo for full sizing – note that the scale rule cube = 1cm.

This is a scientifically intriguing and display-worthy Eocene turtle exoskeleton fossil from one of Britain’s most productive fossil sites. A fine addition to any fossil collection, especially for those interested in ancient reptiles or the palaeontology of the British Isles.

Own a real piece of early Cenozoic history—fossilised remains from over 38 million years ago!

#Turtle exoskeleton fossil#Barton Beds fossil turtle#Eocene turtle shell#Whitecliff Bay fossil#Isle of Wight fossil reptile#rare UK turtle fossil#Eocene vertebrate fossil#fossil carapace fragment#British fossil turtle shell#certified turtle fossil specimen

0 notes

Photo

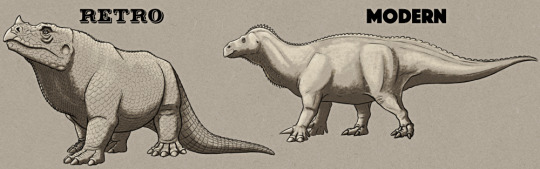

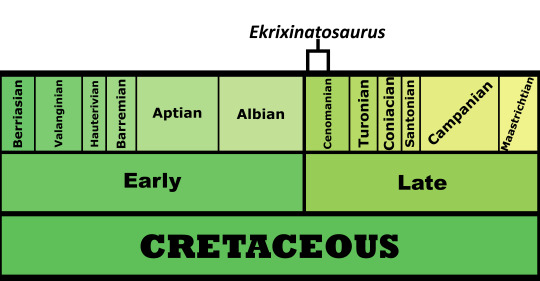

Retro vs Modern #15: Dimetrodon limbatus

With its prominent sailback Dimetrodon is one of the most iconic prehistoric animals – and one that still frequently gets mistaken for a dinosaur, despite being closer related to modern mammals.

1870s-1980s

The first known Dimetrodon fossil was an upper jaw fragment found in Canada in the 1840s, but at the time this specimen was thought to represent a dinosaur. It wasn't until the late 1870s that species like Dimetrodon limbatus (initially called Clepsydrops limbatus) from the Midwestern and Southern United States were recognized as belonging to a much older and different group of animals given the name "pelycosaurs".

While some paleontologists did propose pelycosaurs as being ancestral to mammals quite early on, for several decades the prevailing view was actually that they were an ancient branch of rhynchocephalian reptiles closer related to modern tuataras. From the 1910s onwards pelycosaurs were finally linked back to mammals, with their similarities to the therapsids placing them as early members of the synapsid lineage – although all these early mammal-relatives were still considered to be derived from reptiles, and "mammal-like reptile" became a commonly-used term for them.

As a result reconstructions of Dimetrodon during this time period usually depicted a highly reptilian and heavily scaled lizard-like animal, with a sprawling belly-dragging pose, protruding crocodilian-like teeth, and a highly shrink-wrapped sail on its back modeled on those of some modern lizards. Some earlier images also showed a short stumpy tail, since Dimetrodon's longer tail proportions weren't confirmed until the 1920s.

2020s

During the late 20th century new classification techniques led to the messy concept of "reptiles" being properly redefined as sauropsids, and synapsids being recognized as an entirely separate non-reptilian lineage of amniotes. Along with new studies and discoveries this has resulted in our understanding of Dimetrodon changing a lot in the last few decades, moving away from a heavily reptilian interpretation and instead letting it be its own weird "protomammal" thing.

We now know there were at least a dozen different species of Dimetrodon living during the early-to-mid Permian, about 295-272 million years ago. Most of them are known from North America, but an additional species discovered in Germany suggests this genus ranged further across Pangaea than previously thought.

Dimetrodon limbatus was one of the larger species, about 3m long (10'), and like other members of the genus it had a tall narrow skull with high-set eyes and two distinct types of teeth in its jaws. The structure of its nasal cavities suggest it had a good sense of smell, and like the related synapsid Ophiacodon it may have had a closer to "warm-blooded" metabolism than previously thought.

It would have had a very poor sense of hearing, however, and probably didn't even have any visible ears on its head. It may have been functionally deaf to air-borne sounds entirely, only able to detect vibrations by pressing its lower jaw to the ground.

No skin impressions are known for Dimetrodon. Scaly reptile-like skin has been found on varanopids, a group traditionally classified as very early synapsids – but some recent studies have suggested they were actually part of the true reptile lineage, so their extensive scaliness probably doesn't apply to synapsids like Dimetrodon after all. There is some possible evidence of rows of square or rectangular scale-like scutes on the underside of the belly and tail in pelycosaur-grade synapsids, but otherwise the next-closest known synapsid skin comes from the distantly-related therapsid Estemmenosuchus, which seems to have had smooth glandular skin similar to a hairless mammal.

The characteristic back sail, formed by highly elongated neural spines on the vertebrae, is now thought to have been covered in a different pattern of soft tissue than older reconstructions depicted. The texture of the bone along the spines' length shows that at the base they were deeply embedded in the back musculature, then further up they were covered by skin webbing, but then at the tips they may actually have been unwebbed and free-standing, giving a much spinier profile.

While the sail was traditionally assumed to be used for temperature regulation, more recently this has started to seem less likely. The sail doesn't seem to have been quite as well-supplied with blood vessels as previously thought, and there's a lack of direct correlation between sail size and body size in different Dimetrodon species and age classes. Instead this structure may actually have been used for visual communication and display, and could therefore have been quite flashy and brightly-colored.

Fossilized trackways also suggest that Dimetrodon didn't move with a low lizard-like sprawling gait but instead with something more like a crocodilian "high walk", with its limbs much closer to upright. It was probably a fairly active terrestrial predator and would have eaten a wide variety of other smaller Permian animals, with its teeth having been found in association with the remains of the amphibians Eryops and Diplocaulus and the freshwater shark Xenacanthus.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#retro vs modern 2022#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#dimetrodon#sphenacodontidae#synapsid#stem-mammal#protomammal#art#sailback#retrosaurs#stop shrink-wrapping synapsids#dimetrodon was basically less like a Permian dragon and more like a Permian *bear*

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Turtles

Turtles evolved many million years ago, hence being the earliest group of reptiles.

Turtles are aquatic animals, spending most of their time in water. They have webbed feet or flippers, combined with a streamlined body. The only time sea turtles will leave the ocean is to lay their eggs in the sand.

Tortoises however, are land animals. Their bodies have been adapted in different ways to turtles, for example; tortoises have stumpy round legs for walking on land. They can also dig burrows for when the sun gets too hot with their strong forelimbs.

The largest sea turtle is the Leatherback Turtle; it weighs 272 to 680 kilograms, and is 139 to 160 centimetres long (WWF). The smallest turtle is the Speckled Cape Tortoise; it’s shell is around 7.9 centimetres long and it only weighs 142 grams.

A turtles shell is a modified rib cage and part of the vertebral column, the top part of the shell is called the carapace and the bottom is called the plastron. It’s made up of about 60 bones that are covered by plates called 'scutes', these are made of keratin (ADW).

All turtles lay eggs. They find a place on land to lay their eggs, dig a nest into the sand or the dirt and then walk away. No species of turtle nurtures their young. Sea turtles usually lay around 110 eggs in a nest, though the flatback turtle only lays around 50 at a time.

The temperature of the sand affects the sex of the turtle. Equal number of male and female offspring are born if the beach temperature is perfect however, due to rising temperatures, too many sea turtle females are being born. This is contributing to the decline in species numbers (Sea Turtle Conservatory).

The earliest known turtle fossils are from around 220 million years ago, the Triassic period. They are nearly identical to modern turtles anatomically. Sea turtles have been around for around 120 million years.

A pair of Russian Steppe Tortioses got sent into space in 1968, in the Zond 5 launched by the Soviet Union. This was a space probe that was the first spacecraft to orbit the moon. It returned safely and the tortoises survived (NASA).

1 note

·

View note

Photo

“The Royal Society’s conversazione—skeleton of the Pareiasaurus bainii, a huge fossil reptile, exhibited by professor H. G. Seeley,” from The Graphic, 16 May 1891

The artist dreams he is Ezekiel, taken by the Lord to a barren, rocky place, where, amid the stones and crags, lie the jumbles of a skeleton—massive, strewn bones of a beast long dead.

“Son of man,” says the Lord, “can these bones live?”

Says the artist, “Sovereign Lord, you alone know.”

Then the voice of the Lord speaks again, “Prophesy to these bones with your pen and ink, and say unto them, Dry bones, I will lay sinews upon you, and bring up flesh upon you, and cover you with skin and scales.”

The artist opens his sketchbook. The valley is silent. A cloud passes before the sun and shadows the earth so that it is difficult to see what is bone and what is rock. But the Lord’s whisper echoes, and, fired with a holy imagination, the artist draws. Lines become forms and the image of the resurrected beast takes shape.

At once, there is a creaking, a rustling. Pebbles roll. Stones shift. The bones lift from the dirt and come together, bone to bone. And, indeed, sinews and flesh come up upon them, stretching over the skeleton like layers of wet silk and red clay. Still, he draws. Drool glistens at the edge of the beast’s coarse mouth and drips onto the dust. The artist feels his hand rushing over the paper, hears the pen nib scratch its surface. And the skin clothes the flesh, lumpy and jagged with scutes and scales, the snout flecked with whiskers and snot. Yellow eyes roll in the once hollow sockets and stare.

When the drawing is finished, the artist lifts his pen, and the breath of the Lord pushes past him, tugs his fussy coattails and tips his hat, and flows into the beast like a silent river. A heartbeat drums within the monstrous frame; a pink tongue lolls out, licks those bumpy chops; the eyes spark; toes curl in the dust; and the beast exhales. Its hot breath crashes over the artist, a wave of humidity and boggy scent.

At this, the artist awakens.

117 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Gargantosaurus Length: 250 foot Height (At shoulder): 80 foot (At hip): 60 foot Weight: Approx 100 tons Colour: Black with deep red markings. Diet: Carnivorous Noticeable features: Skin tends to be smooth with small patches of bumpy scales around hip and shoulder areas, and is often coated with what appears to be oil (possibly secreted from pores?). The body bares a strong crocodile build, and is adorned with raised scutes down the center-line of the back. Forelimbs are longer than the hind limbs. Unusually, the head is strangely humanoid in appearance to the point in which it is described as being almost "10% human to 90% reptile". The mouth is large and full of long needle-like teeth. The most striking feature of the Gargantosaurus specimen witnessed (See image above) is the horns/crest that run along the head. It is speculated that this individual could be a variant (sub-species?), or maybe even a rare glimpse of a 'pure-blood' which has miraculously survived since the Mesozoic Era* Notes: One look at Gargantosaurus, and it is easy to see how the ancient myths of dragons and sea monsters, and other 'kaiju' style creatures have sprung up across the world. With the now proven existence of living Gargantosaurus specimens, one must wonder just how many other giant creatures, known only through folk-law, are waiting out there to be discovered as real. *Gargantosaurus fossils have been found in deposits dating back 66 million years. That living specimens exist today is amazing given how little such a large animal has evolved. Some of the more 'crackpot' theories that have been circulating of late is that Gargantosaurus (and possibly other prehistoric species) were subject to experimentation by 'otherworldly beings', enabling the 'experimental variants' to survive while the 'pure-bloods' died out. Concept art of Gargantosaurus as featured in the novel 'Saurian' by William Schoel

#lizardman22#monster#kaiju#gargantosaurus#dinosaur#reptile#reptilian#reptilia#saurian#novel#book#digital#digital art#art#fan#fan art#concept#concept art#william schoel#bio#digital drawing#drawing#dinosaura#dinosaurian#quadraped#crocodillian#hybrid#human hybrid#william schoell

0 notes