#Eocene reptile fossil

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Fossil Snake Vertebra PALAEOPHIS TOLIAPICUS London Clay Eocene Isle of Sheppey Kent UK Authentic Specimen

This listing features a fossilised vertebra of the extinct marine snake Palaeophis toliapicus, from the renowned London Clay Formation of the Isle of Sheppey, Kent, UK. This is a carefully selected specimen from the Lower Eocene Epoch, and comes with a Certificate of Authenticity.

Palaeophis toliapicus is an extinct marine snake, part of the family Palaeophiidae, known for their elongated vertebrae and presumed aquatic adaptations. These snakes lived during the Ypresian Stage of the Eocene (~56 to 47.8 million years ago) and are considered some of the earliest large marine snakes to evolve after the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs.

The London Clay Formation is a world-famous fossil-bearing deposit laid down in a subtropical marine shelf environment, rich in marine and terrestrial fauna. The Isle of Sheppey exposures are particularly renowned for vertebrate fossils, including sharks, crocodiles, turtles, and snakes such as Palaeophis.

Morphological Features:

Elongated centrum with a slightly compressed form

Lateral foramina (small holes for blood vessels)

Well-defined neural canal and arch facets

Adaptations suggest a streamlined body ideal for swimming

These features make the vertebrae of Palaeophis instantly recognisable and highly sought after by collectors and researchers alike. Their rarity and scientific importance make them outstanding additions to any vertebrate fossil collection.

This is the exact specimen photographed for the listing. Scale rule cubes/squares = 1cm. Please refer to the image for full sizing.

Specimen Details:

Species: Palaeophis toliapicus

Fossil Type: Snake Vertebra (Reptile Bone)

Formation: London Clay Formation

Age: Early Eocene (Ypresian Stage)

Location: Isle of Sheppey, Kent, UK

Depositional Environment: Subtropical marine shelf

Family: Palaeophiidae

Order: Squamata

This is a rare opportunity to acquire an authentic specimen of a prehistoric marine snake from one of the most productive fossil sites in Europe. Ideal for collectors, educators, and anyone with an interest in paleo-reptiles or Eocene marine ecosystems.

All of our Fossils are 100% Genuine Specimens & come with a Certificate of Authenticity.

#Palaeophis toliapicus vertebra#fossil snake bone#London Clay fossil#Eocene reptile fossil#snake fossil Sheppey#Kent fossil snake#UK reptile fossil#Eocene snake vertebra#Palaeophis fossil for sale#Eocene vertebrate fossil#Isle of Sheppey fossil#authentic Palaeophis vertebra#snake fossil UK#marine snake fossil#rare Palaeophis fossil#vertebra fossil London Clay

0 notes

Text

#2829 - Psephophorus terryprachetti - Pterry's Giant Pturtle

A very large, extinct, leatherback turtle from the Eocene, named after beloved author Terry Pratchett. He was pleased about this, saying that anybody that wasn't delighted about getting a species named after them was clearly a Pod being from the Planet Zog.

The first fossils from the genus were discovered by German Paleontologist Christian Erich Hermann von Meyer in 1846, but all he had were the dermal plates (not that different from the fossil above, really). That's probably why even by 1879, they still weren't clear on what it actually was - British paleotologist Harry Govier Seeley thought they resembled the armour of an armadillo.

The Pturtle was discovered in New Zealand in the 1990s. It would have been 2.5m long, in life.

Sadly, there's only one Dermochelyid turtle left in the world - the Leatherback Dermochelys coriacea, which is critically endangered in some areas. Leatherbacks are unique compared to other modern sea turtles because they lack a bony shell; instead, its carapace is covered by oily flesh and flexible, leathery skin. They're also the deepest-diving and fastest reptiles in the world, swimming down to over 1200m depth, at speeds of up to 35kph. Their constant activity and internal adaptations lets them run at a surprisingly high internal temperature - 18C above the surrounding water.

The biggest threat to leatherback survival is, unfortunately, humanity - hatchlings can be confused by artificial light and head inland instead of towards the water, older turtles are easily caught in fishing nets, and they can confuse plastic bags floating in the water for the jellyfish that form the bulk of their diet.

Otago Museum, Dunedin, Aotearoa New Zealand.

#Otago Museum#Dunedin#Dermochelyidae#Psephophorus#leatherback turtle#new zealand fossil#fossil turtle#terry pratchett#great a'tuin

210 notes

·

View notes

Text

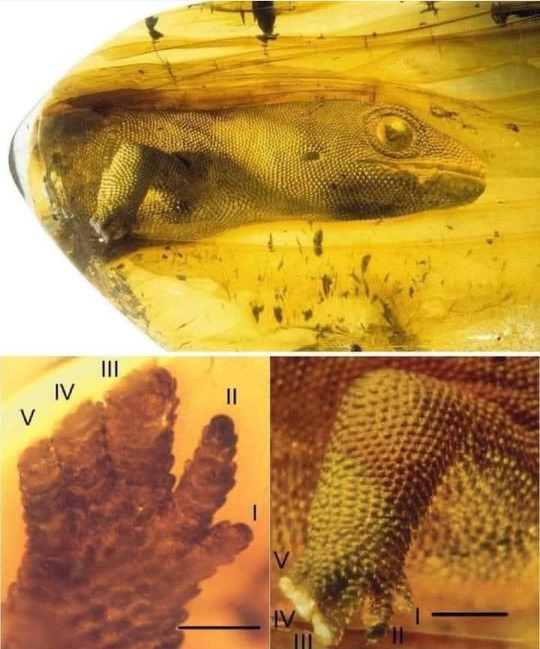

A 53-million-year-old gecko fossil was discovered almost perfectly preserved in Baltic amber. This Lower Eocene specimen represents a new genre and species, with a unique digital morphology, different from current geckos.

The 54-million-year-old Baltic Amber preserved key anatomical details, revealing surprising evolutionary adaptations. Unlike modern geckos, it displays primitive digital structures, which provides clues to the evolution of their locomotion.

They are believed to have developed adhesive pads multiple times in their evolutionary history, facilitating their adaptation to arboreal environments. This finding enriches our understanding of reptile evolution and past biological diversity.

The fossil highlights the importance of the Baltic amber as a window into the past, holding crucial evidence for science. A true treasure that connects modern biology to the origins of these fascinating creatures.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

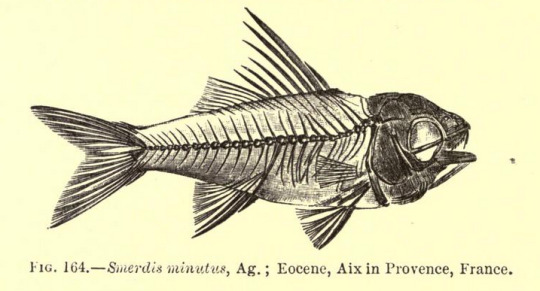

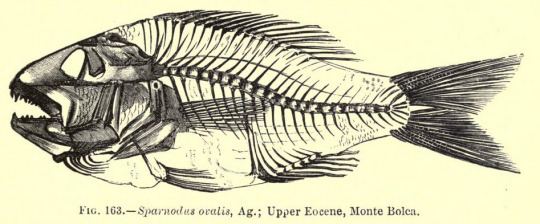

Eocene fish skeletons (Smerdis minutus & Sparnodus ovalis) from A Guide to the Fossil Reptiles and Fishes in the Department of Geology and Paleontology in the British Museum (Natural History), 1896.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

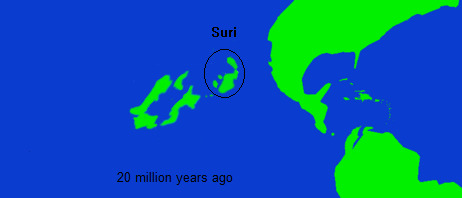

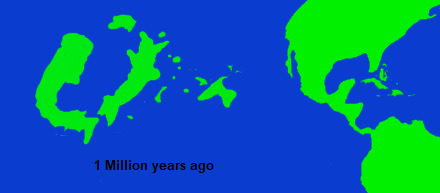

Paleontological Biogeography of Niur

The unique characteristics of Niuri fauna (and to a lesser extent flora) have been shaped by the geology and isolation of the islands, as they moved through time and space, as well as the unique conditions surrounding them.

Already at the start of the Paleocene, the landmass that would one day form the Niuri islands was already somewhat loosely attached to the South American mainland. Although it fluctuated with sea levels, for most of this period only an isthmus connected the two, and this prevented total faunal exchange from occurring, allowing, even then, isolation enough for the Niuri fauna to diversify separately from their South American relatives.

The Niuri landmass was climatically quite different from the neighboring region of South America, which additionally was a factor limiting the free transfer of organisms back and forth between the landmasses. Even so, outside of insects and some other groups of invertebrates, the fauna of the Niuri landmass, and for the most part the flora, was largely indistinct from that of South America until the middle of the Paleocene, differing mainly in the varying amounts of taxa found rather than the types. Towards the middle Paleocene , however , a low lying area in the middle of the Niuri landmass began to sink and was flooded, first as a large lake and then shortly after as a bay.

In tens of millions of years this bay would become part of the Faln sea, but even from its formation it began to change the life in the surrounding area. The most immediate effect was the change in marine fossils, as the shape of the land around the bay isolated it from the greater Pacific and also provided a unique habitat within it. Additionally, it triggered a further differentiation of the habitat of the Niuri landmass from the South American mainland, especially in the region of the isthmus. Finally, it is believed to have contributed to a broad shift in the climatic stability of the landmass as a whole, as prior to this point, the portion of Gondwana that would one day split of that would eventually become the Niuri landmass was subject to a high degree of climate instability , particularly in inland environments, and tended to support a very low diversity of megafaunal animals.

Beginning with the formation of the Paleo-Faln Bay the middle Paleocene the Niuri climate would change to instead become remarkably stable and consistent during the Neogene, much more so than neighboring continents or indeed most of the world. That said any semblance of stability during the last half of the Paleocene was rather abruptly interrupted by the end of that period.

The Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum appears to have abruptly altered the environment of the Niuri landmass, and it triggered a rapid shift in its faunal makeup. Taxa which had previously been common throughout both Niur and the adjoining regions of South America disappeared or were heavily reduced in Niur, while some groups that all but disappeared in mainland South America continued to flourish in Niur. In the Ypresian, the first period of the Eocene, for the uniquely Niuri fossils of mammals, reptiles, and birds begin to make up a substantial degree of the Paleo record, by the beginning of the Middle Eocene the fossil taxa of Niur is almost wholly distinct from South American forms. It's also around this time when the last connection to mainland South America disappeared, and from then on Niur was an island landmass, drifting to the northwest on its Continental plate.

While it last was directly connected to South America no later than 40 million years ago, Niur was still close enough that birds, plants , some insects and bats could readily cross the gap. Even so this isolation was complete enough that from then on all future introductions of new fauna to the Niuri Islands are termed as distinct events. Even prior to becoming truly isolated, the faunal interchanges of Niur and South America in the Paleocene and Early Eocene are also considered to be distinct events, namely the First and Second South American introductions. The First Introduction refers to a period of time in the late Paleocene, where after some degree of distinction had already emerged in the islands some new faunal groups migrated over from South America. The more impactful Second Introduction occured immediately prior to the final severance, somewhere around 45-40 million years ago, perhaps caused by a temporary widening of the connection between the landmasses before it finally was buried under the sea. These new groups were subject to almost immediate, intense evolutionary pressures upon Niur's isolation, and those that survived rapidly diversified into new forms.

In the early Eocene, the western half of the Niuri landmass had been rendered an island and with the separation from South America, and these would retain separate faunal assemblages until the Oligocene, when changes in the landscape and sea level led to an interchange of animal taxa across the islands. The landmasses that composed these islands were heavily altered in position and shape, and are not to be confused with the two later proto-islands that would appear (along with Senika) later in the Neogene. The largest differences between these two assemblages were mammalian taxa, with birds and reptiles appearing to be less affected by the gap between them, although it's believed that the poisonous bird groups originated in the western island before also expanding into the eastern island as well. While both western and eastern islands included members of the initial mammalian assemblages, as well as those that arrived during the First South American introduction, the mammals that arrived in the Second and later Third South American (which occurred in the latest eocene or earliest oligocene, as a chain of islands allowed some taxa to island hop from northern South America) introductions were limited to the eastern island until the late Oligocene. Most prominent among the eastern limited animals were the Notoungulates, the Pyrotheres, and later the Astrapotheres and ameridelphian marsupials all of which would lead to unique Niuri taxa that are still extant. In addition to this, xenarthrans were present in the eastern island as well, although these remained species poor and went extinct by the end of the Oligocene. There are at least some teeth fossils that suggest that Litopterns may have briefly been present in the eastern island, in the mid Eocene.

Meanwhile the only major group of placental mammal to survive in the western island during this time period were the xenungulates (of the first South American introduction), which although initially being somewhat diverse and common in the early Eocene, afterwards appeared to have been in a long decline before disappearing in the Oligocene. The other mammals present in the western island were the various non-placental mammals, which along with the Niuri ameridelphians (Kaulodelphidae) , are collectively called "Koutou" in modern Niur, despite not being particularly closely related. These include the Gondwanatheres, and Polydolopimorphia, both present from the earliest Paleocene, and the Sparrassodonts, and the Xenodelphians from the First South America introduction. The Sparrassodonts were additionally present in the fauna that arrived during the Second South American introduction, and the new arrivals appear to have replaced the Sparrassodonts still present on the Eastern Island, although after the faunal interchanges in the Oligocene both Western and Eastern Sparrassodonts continued to flourish. Additionally, the Polydolopimorphia maintained high diversity on both western and eastern islands until the Oligocene, and all three modern families appeared nearly simultaneously on both islands before the faunal interchanges that unified the assemblages (although one extinct, enigmatic family that appeared to be endemic to the eastern island went extinct not long after).

Shortly prior to the Oligocene Faunal Interchange, there was one additional "introduction event" wherein, most likely via a single rafting event, salamanders were introduced to what is now Senika (which was the earliest modern island to differentiate itself clearly in the fossil record). In the Niuri paleontology this is called either the First North American Introduction or the Zero Suri Introduction, as its debated whether they rafted from North America or from the Suri islands. They would gradually spread during the rest of the Oligocene, before more heavily diversifying in the Miocene.

In the mid to late Miocene, the Suri islands, themselves subject to a long and generally less understood geological history, approached close enough to the east of Niuri that fauna and flora could exchange between these two island chains. The fossil record of the Suri islands is confusing, and this is further complicated by the fact that they have been subject to gradually increasing subsidence for the past 10 million years, which along with the rise of sea levels during the Holocene , has buried much of the former Suri landmass under the sea. This process of sinking was somewhat abated by a period of volcanism which created new land inbetween Suri and Niur, as well as contributed to the geological features of eastern Niur, that said much of this volcanism had dissipated by the Pleistocene.

The first evidence of an interchange between Suri and Niur, actually appears in Suri, around 15-18 million years , when rather abruptly various distinctly Niuri plant pollen taxa appear almost simultaneously throughout fossil sites in Suri. This is followed shortly after by Niuri avian fauna, which although less attested appears to rather rapidly replace the indigenous Suri birds (although how complete this replacement was is hard to say, given the fragmentary record). The introduction of Niuri life in Suri seemed to trigger a wave of extinctions as well as spur the new evolution of Suri life.

Generally it seems that during the Miocene, most introductions between Niur and Suri tended to follow the pattern of Niuri life establishing itself in Suri, with little managing to travel the other way. Following the avifauna, Niuri Astrapotheres and Xenodelphians arrived in Suri, becoming firmly established during the late middle Miocene. Around this time, the two island chains reached their closest point of contact, after which Niur would continue to drift eastward at a greater speed than Suri. Even so, because of the lowered sea levels during the Pliocene and Pleistocene, and continuing volcanicism creating temporary, connective archipelagos, the faunal interchanges would continue, although in separate pulses. The last phase of the the first Suri introduction was the point at which Suri fauna, perhaps finally adapted to the pressures of the Niuri arrivals, managed for the first time to make the journey to Niur. Between 10 and 7 million years ago, a variety of Suri taxa became established in Niur. The first, and most widespread of these groups, were the two Suri families of salamander, which now accompanied the earlier cryptobranchid salamanders that had been introduced in the Oligocene. Additionally, for the first time, rodents found their way to Niur, the small mouse like members of the family Sminthidae (one of the only rodent families to survive in Suri) adapted to alpine habitats in Niur, and in present at least five species are known in the genus Subtilicus. The one megafaunal introduction, though, was the most impactful, the carnivoran feneraks. These catlike predators are part of the larger clade Felarimorpha which is either a suborder of Carnivora itself or an infraorder of Feliformia (although some phylogenetic analyses have proposed that Felarimorpha might instead be the sister taxa of all other carnivorans) . Feneraks make up one of the two living clades of Felarimorphs, although the first feneraks in Niur were part of a now extinct group, often called the Crested Fenerak, after the unusual protrusions that later members developed on their skulls. Crested fenerak gradually spread throughout much of Niur, and took the place of the sparrasodonts as top mammalian predators (and indeed, in many habitats, as top terrestrial predators in general). Crested fenerak would continue to evolve in Niur, while new groups, more closely related to modern fenerak, evolved in Suri. Niur and Suri drifted away from each other, the first period of interchange ended, with the fauna of both islands profoundly shifted.

The two island chains, for much of the Pliocene, existed largely in separation from each other, although birds and plants still managed to easily cross from one to the other. Niur, especially the southern parts of it, has many plant genera in common with Central America and Northern South America, and while its unknown exactly when they made the journey there, many groups present are believed to be relatively recent evolutionarily speaking, and therefore may have been the result of birds ferrying their seeds from the continents , to the southern parts of Suri, and then to Niur. Most prominently, the wide variety of cactuses in Niur, many of which are relatively closely related to species found in North and South America, is believed to be caused by such patterns. This might also be where many of the Solanaceae present in Niur originate from, and unless the result of an ancient introduction by people, almost certainly how the genus Capsicum arrived.

Both Niur and Suri experienced environmental and ecological changes during the Pliocene, and in Niur at least, this lead to the decline of the crested-fenerak in most locations other than what is modern day Nirou, by the end of the Pliocene. Rather than disappear all at once, they seemed to gradually decline area by area, at first in the south of greater Kaita, with their disappearance spreading from there until they were restricted to the northern plains of Nirou. This disappearance was historically tied to the onset of the Second Suri introduction, which is considered to have started shortly before the onset of the Pleistocene, as lower sea levels and renewed volcanic activity again created a bridge between Suri and Niur, and allowed the dispersal of the modern feneraks into Niur. However, more recent research suggests that the crested-feneraks began their decline before modern feneraks arrived, and in fact it was only in areas where they had already disappeared that modern feneraks were able to establish themselves, with the exception of northern Nirou, where crested-feneraks survived for much longer and coexisted with their modern cousins until eventually going extinct during the late Pleistocene. There are five species of fenerak alive today in Niur, and they probably evolved from at least somewhat semi-aquatic ancestor (as the water-fenerak is today still) which managed to island hop to eastern Niur, although its unclear if this was the result of one or two introductions. The record throughout much of the Pleistocene is ambiguous, and the exact history of the fenerak might be better elucidated by further genetic studies. The other group of Suri animals that is typically considered to be part of the second introduction were the peccaries, which live today in various forests on the eastern Islands of Niur. Although their choice of habitats is different (both in Niur and Suri they exclusively live in relatively cool forests) they seem closely related to the American peccaries, to the point where its a bit of mystery as to how they arrived in Suri in the first place. Compared to the fenerak which are usually apex predators or at least dominant in their environments, Niuri peccaries, while locally common, tend to be more marginal parts of their ecosystem, and even still mostly live in areas where they have less competition from other mid to large size herbivorous animals.

There is no exact boundary between the Second and Third Suri introductions, because low sea levels throughout the Pleistocene meant that there was an almost continuous potential for island hopping between Niur and Suri. Rather, the Third introduction is defined by its most famous member, the people of Niur, the felar-mesai, who first arrived in Niur from Suri, sometime in middle Pleistocene. Because of their beliefs regarding remains of the dead and genetics, most studies on Niuri paleoarcheology have focused on material culture, and because of this many dates regarding the earliest records of people in Niur are subject to massive ranges. Its also unclear if the earliest people in Niur were members of the same species as present day mesai, and the fragmentary record of remains is complicated by the fact that there is a high degree of genetic diversity within the present day mesai (much more so than modern humans), meaning that any species level determinations based on bone fragments are highly contested. Different methods of dating have suggested various results of when the first people in Niur arrived (or at least, the first member of the clade of felarimorpha to which modern mesai belong to), anywhere from 150,000 to 800,000 years ago, a time range of over half a million years. These inconsistencies might be explained by the "lost seeds" hypotheses, which views these early records as evidence not of permanent populations but rather temporary, small groups of mesai, which periodically would arrive in Niur during certain climatic periods, which corresponded to a spread of specific Suri plant taxa in Niur, and then disappear when the climate shifted again and those plants became less common, without ever becoming fully established in Niur. Even those that oppose this theory, tend to view the populations of Niur during this time as being sparse and likely subsumed by later arrivals. The period around 120,000-70,000 years ago is seen as the first clear period of continuous inhabitation of Niur, and appears to correspond with a new group of people arriving from Suri, or at least a new material culture spreading from there. Even so, population density was incredibly low, and subsequent migration from Suri in various pulses continued until around 20,000 during the last glacial maximum. The mesai population in Suri would decline considerably after this point, with the last evidence of living mesai dating to perhaps around 10,000 years ago, although there may have been a very small remnant population until as late as 8,200 years ago.

Along with mesai, at least in the later migrations, included various semi-domesticated Suri plants, which form the bulk of the other arrivals during the Third Suri introduction. By the time of the last glacial maximum, the volcanicism that had created island chains between Suri and Niur had mostly subsided, and the islands that were left gradually sunk into the rising sea levels of the Holocene. The last remnants of that volcanism are the hot springs and mountains of Senika, Nacre and the islands to its north. Despite the massive changes in climate and land, as well as the arrival of people, most of Niur's native fauna remains highly successful, and incredibly distinct. Groups that have long gone extinct elsewhere thrive there, and its unique ecosystems have so far avoided the fate of other isolated environments that has so often come about as the result of new introductions. Outside of some plants and a few insects associated with introduced agriculture, almost no invasive species have managed to take hold in Niur, and few if any native taxa have gone extinct in the last 10,000 years.

On the contrary, the robustness of Niuri ecosystems have leant some Niuri taxa the ignominious status of being invaders themselves, mostly a handful of insects and plants, aside from one specific incidence where one of the large Niuri ratites (the Upland Takako) become established in parts of Spain after a failed attempt to farm them. These large birds have proved to be a nuisance in Spain, as well as being environmentally damaging, as they will kill foxes or other mammals they view as a threat to their eggs or young, as well as domestic goats and sheep they view as competition for food. Attempts to control them via hunting have been partially successful, although the surviving population (mostly in the Pyrenees) is much more wary of humans and traps and is also notoriously dangerous, sometimes injuring or even killing hunters (in addition to sheep and goats).

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

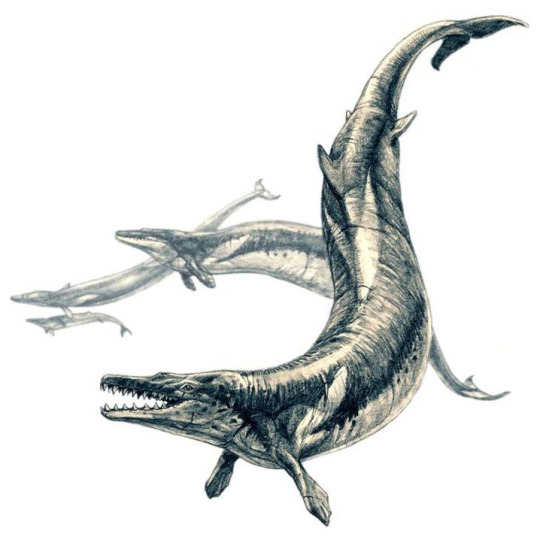

Basilosaurus

(temporal range: 41.3-33.9 mio. years ago)

[text from the Wikipedia article, see also link above]

Basilosaurus (meaning "king lizard") is a genus of large, predatory, prehistoric archaeocete whale from the late Eocene, approximately 41.3 to 33.9 million years ago (mya). First described in 1834, it was the first archaeocete and prehistoric whale known to science.[2] Fossils attributed to the type species B. cetoides were discovered in the United States. They were originally thought to be of a giant reptile, hence the suffix "-saurus", Ancient Greek for "lizard". The animal was later found to be an early marine mammal, which prompted attempts at renaming the creature, which failed as the rules of zoological nomenclature dictate using the original name given. Fossils were later found of the second species, B. isis, in 1904 in Egypt, Western Sahara, Morocco, Jordan, Tunisia, and Pakistan.[3] Fossils have also been unearthed in the southeastern United States and Peru.[4][5][6]

Basilosaurus is thought to have been common in the Tethys Ocean.[7][8] It was one of the largest, if not the largest, animals of the Paleogene. It was the top predator of its environment, preying on sharks, large fish and other marine mammals, namely the dolphin-like Dorudon, which seems to have been their predominant food source.

Basilosaurus was at one point a wastebasket taxon, before the genus slowly started getting reevaluated, with many species of different Eocene cetacean being assigned to the genus in the past, however they are invalid or have been reclassified under a new or different genus, leaving only 2 confirmed species. Basilosaurus may have been one of the first fully aquatic cetaceans[2] (sometimes referred to as the pelagiceti[9]). Basilosaurus, unlike modern cetaceans, had various types of teeth–such as canines and molars–in its mouth (heterodonty), and it probably was able to chew its food in contrast to modern cetaceans which swallow their food whole.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Messel Pit Fossil Site

Today, we're embarking on a journey to the UNESCO World Heritage Site of the Messel Pit Fossil Site in Germany, where the secrets of Earth's ancient past are preserved in remarkable detail, waiting to be discovered.

The Messel Pit Fossil Site is a paleontological paradise that provides a glimpse into life on Earth 47 million years ago during the Eocene epoch. It's like a time capsule from a distant past.

In 1995, this site was granted UNESCO World Heritage status, recognizing its extraordinary scientific and historical significance. It's a place where fossils tell the story of evolution and the environment in vivid detail.

What makes Messel truly unique is the remarkable state of preservation of its fossils. The fine-grained oil shale has preserved not only the bones but also soft tissues, feathers, and even the contents of stomachs.

The Messel Pit is a treasure trove of prehistoric life. Fossils include early mammals, ancient reptiles, early primates, and a wide variety of plant life, offering a comprehensive view of Eocene ecosystems.

The site has been instrumental in our understanding of the evolution of mammals, birds, and insects. Fossils like the Eocene horse Propalaeotherium and the ancient crocodile Baryphracta becki are just a couple of the many remarkable discoveries.

The Messel Pit is not just a place for excavation but also for scientific research and conservation efforts to ensure the continued preservation of its valuable fossil record.

Messel is a place of learning and discovery, hosting events, exhibitions, and educational programs that celebrate the rich scientific heritage of the site.

In conclusion, the Messel Pit Fossil Site is a gateway to Earth's ancient past, offering a remarkable view of prehistoric life and evolution. As a UNESCO World Heritage Site, it invites us to appreciate the significance of paleontology and the remarkable stories fossils can tell. When you're ready to explore a world where time is frozen in stone, the Messel Pit is a destination that promises to inspire and captivate. 🌍🦕🔍

#messel#pit#fossil#culture#germany#europe#unesco#world heritage#discovery#ancient#travel#paleontology#past

1 note

·

View note

Text

This is absolutely fascinating. This statement in particular caught my attention. Related turtles survived after the extinction of dinosaurs. From the article:

While Solnhofia went extinct at the end of the Jurassic as sea levels fell and the European archipelagos briefly dried out, the family lingered through the extinction of the dinosaurs, evolving bizarre representatives with cue-ball shaped heads in the Eocene Epoch before finally disappearing.

1 note

·

View note

Text

"I have made a grave mistake"

Yantarogekko preserved halfway in amber

Photo credit - Wolfgang Weitschat, Universität Hamburg

#art#digital art#illustration#yantarogekko#gecko#reptile#paleoart#paleo art#fossil amber#Eocene#paleontology

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Large Crocodile Scute Fossil – Diplocynodon – Eocene, Morocco

Offered for sale is a large fossilised crocodile scute, identified as belonging to the extinct genus Diplocynodon. This impressive specimen originates from Eocene-aged deposits in Morocco, representing an ancient relative of modern crocodiles that once thrived in subtropical freshwater environments.

Fossil Type:

Specimen: Crocodile Scute (Osteoderm)

Genus: Diplocynodon

A heavily armoured part of the dermal skeleton, typically located along the back or flanks

Geological Context:

Period: Paleogene

Epoch: Eocene

Age Range: ~56 to 34 million years ago

Depositional Environment: Fluvial and lacustrine (river and lake) systems typical of subtropical Eocene Morocco. These ecosystems were rich in crocodilians, turtles, and early mammals, with fine sediments preserving vertebrate remains well.

Morphological Features:

Large, bony scute with characteristic pitted texture and convex curvature

May show keel or central ridge depending on location in the body armour

Fossilised in mottled brown, grey, or ochre hues due to iron and mineral replacement

Scientific Importance:

Diplocynodon is an extinct genus of alligatoroid crocodilian known from both Europe and North Africa

These scutes help researchers understand crocodile evolution, biomechanics, and defensive adaptations during the Eocene

Scutes like this are commonly found detached from the skeleton and provide valuable data for species identification and palaeoecological reconstructions

Locality Information:

Morocco – a globally significant fossil locality for Eocene freshwater deposits, yielding crocodyliform remains alongside fish, turtles, and mammals

Authenticity & Display:

All of our fossils are 100% Genuine Specimens and come with a Certificate of Authenticity. This listing includes actual photographs of the specimen you will receive. Please refer to the photo for full sizing – the scale cube = 1cm.

This is a fantastic collector’s piece for anyone interested in fossil reptiles, Eocene ecosystems, or the evolution of crocodilians. A well-preserved and visually impressive fossil, ideal for educational display or private collections.

Own a real piece of Eocene life—an armoured fragment from a prehistoric crocodile over 40 million years old!

#Crocodile scute fossil#Diplocynodon fossil Morocco#Eocene crocodile armour#fossil crocodile plate#Eocene reptile fossil#authentic crocodilian fossil#Moroccan fossil croc#fossil osteoderm#reptile scute fossil#certified fossil scute#prehistoric croc fossil

0 notes

Photo

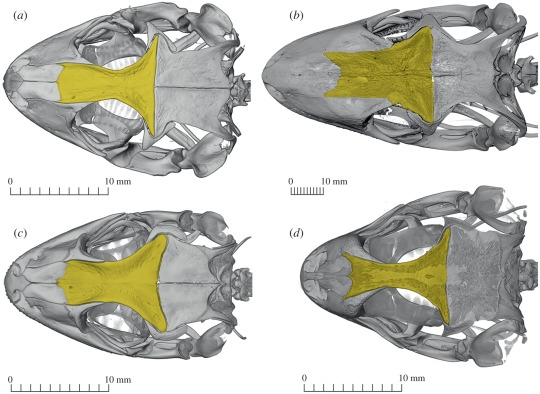

Europe's Oldest Gecko Species Lived in Belgium

Paleontologists have described a new extinct gecko species from Belgium. The lizard Dollogekko dormaalensis lived 56 million years ago, making it the oldest gecko species in Europe. 'This discovery provides new evidence for the early history of geckos in Europe,' says Annelise Folie, paleontologist at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences (RBINS). The scientists named the new species after the famous Belgian paleontologist Louis Dollo.

Living geckos are found worldwide in tropical and subtropical regions. Most species are adapted to warm climates, so in Europe you will only find them around the Mediterranean Sea. But during the Eocene epoch, 56 to 34 million years ago, it was much warmer in our regions and a lot of thermophilic animals, including geckos, could be found in more northern latitudes than today.

An international team of paleontologists examined a fossil of such a prehistoric gecko from the collections of the RBINS. The fossil was found in Dormaal, a borough of the Belgian town of Zoutleeuw in Flemish Brabant. As it turns out, the fossil belongs to a hitherto unknown species, and represents the oldest remains of geckos known in Europe, together with indeterminate material from Portugal. The new species, Dollogekko dormaalensis, is therefore the earliest living gecko species from Europe described so far.

The only part of this individual that the scientists found was the fossilized frontal bone. However, due to its unique shape and external surface sculpture, it provided enough information to conclude that it was a previously unknown species. This forehead bone therefore immediately became the official type specimen - the (part of the) individual used to describe the species - and will continue to be preserved in the collections of the RBINS.

Greenhouse world

Dollogekko dormaalensis lived during a period known as the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (56 million years ago), when Belgium, which today has a temperate marine climate, was much warmer. The new gecko was part of a diverse reptilian fauna of the so-called "Greenhouse World" of this period.

Tropical and subtropical conditions then extended much farther to the poles. In addition, the rise in temperatures during the early Eocene led to a rise in sea level, and many areas of Eurasia were flooded. Europe was an archipelago consisting of several islands. "Given future global climate change and predicted sea-level rise, it is of great importance to understand the distribution of thermophilic, tropical species of the past, as well as the distributions of certain infectious diseases such as malaria," says Andrej Čerňanský, lead author of the study.

What's in a name

When scientists describe a new species, they naturally give it a name. In this case, it was not only a new species epithet (the second part of the scientific name), but also a new genus name (the first part). The species could not be classified in an existing genus because it does not resemble nor lived in the same area than any other gecko species from that period.

The scientists found their inspiration for the species epithet at the location of the discovery of the type specimen: dormaalensis means ‘from Dormaal’. The genus name, Dollogekko, is a tribute to the famous Belgian paleontologist Louis Dollo (1857-1931), best known for his research on dinosaurs, including the Iguanodons, housed at the RBINS. His specialty was the anatomy of extinct fishes and reptiles, including turtles, mosasaurs, snakes, lizards, and dinosaurs.

The study was published in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

This project is a collaboration between researchers from multiple institutions, including the Comenius University in Bratislava, Slovakia (Andrej Čerňanský), Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences (Annelise Folie, Thierry Smith, and Richard Smith), Sam Houston State (Juan Diego Daza) and Villanova University (Aaron M. Bauer) in the United States.

Images 1, 2 and 3 © 2022 The Authors. Published by the Royal Society under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License. Images 4 and 5 © Annelise Folie, RBINS

156 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey guys, how ‘bout a fun fact science corner? I’m wanting to talk about Kimbetopsalis Simmonsae. I know it’s a big word, sadly we don’t have common names for most extinct animals so any creature that hasn’t existed within the last 1000 years is gonna be a mouthful.

Now what does Kimbetopsalis have to do with Cro-Marmot and Dumuzi? This is where science and my headcanons merge.

So Let’s talk Dino-Sore days.

If Cro was around during the age of the Dinosaurs, that dates him all the way back to the Mesozoic era. So let’s throw him at the tail end of the Cretaceous period, when the most popular of the giant reptiles reigned, tyrannosaurus, the titanosaurs, pteranodon, ect.

Marmots did not exist at any time during the entirety of the Mesozoic. In fact, though many of the mammals that lived during that time were very rodent like, true rodents did not even appear for another 10 million years after dinosaurs were wiped off the face of the planet. And marmots did not evolve for at LEAST another 48 million years after THAT.

So Cro and his sister Dumuzi could not have been marmots. So then what were they?

Time to put on my paleonerd hat.

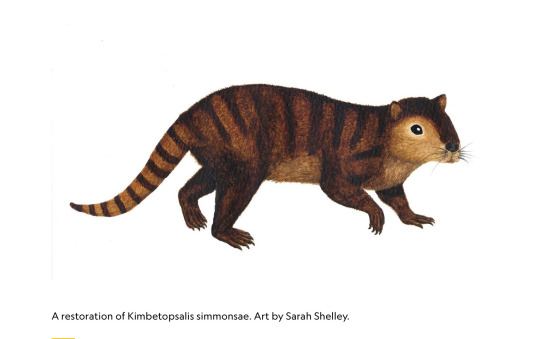

Meet Kimbetopsalis Simmonsae

To the left we have paleoart of what we believe Kimbetopsalis to have looked like, and to the right we have a modern day marmot. Not too drastically different, eh?

Now here’s what’s really cool about Kimbetopsalis. We have fossil evidence that tells us that they are one of the few survivors of the K/PG mass extinction. That’s right, these are one of the legendary mammals that survived the famous asteroid impact that wiped out all the non-avian dinosaurs and played a role in bringing forth the Age of Mammals. If it weren’t for little survivors like them, we wouldn’t be here!

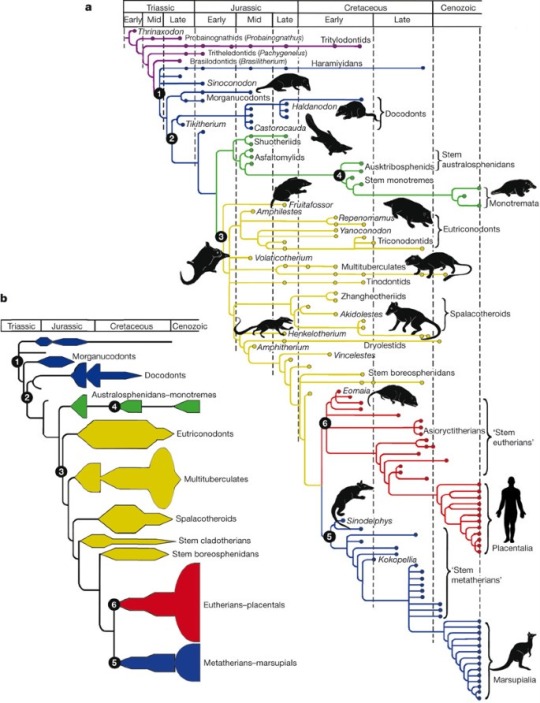

Kimbetopsalis is part of a group of mammals that no longer exists, the multituberculates. These group of animals survived for 130 million years, dying out and disappearing from the fossil record forever in the late Eocene. But don’t be too sad! Multituberculates existed for longer than ANY other group of mammaliforms, including the one that you, I, and every canon character of htf belongs to. The placentals. Today there are only three living groups of crown mammals (aka true mammals): the monotremes (such as the platypus and echidnas), the marsupials (such as kangaroos and opossums), and the placentals.

Now I could go on forever about taxonomies but trust me we’d be here forever. Especially since we are still learning what we can to fully understand mammal evolution. You see, the fossil record for Mesozoic mammals is scarce. Mammals did not get much larger than a badger throughout all the Mesozoic so they did not fossilize easily. Most of what we know about them from that time is from small fragmentary remains, mainly teeth. But despite very few full fossils having been found, we are learning and discovering something new about our ancient mammalian ancestors every day. What we know is constantly changing, but that is the nature of paleontology.

Like I said. We’d be here all day. So let’s move on.

As far as mammals go, Multituberculates like Kimbetopsalis were very common during the Mesozoic. They are easily identifiable by, you guessed it, their teeth.

As you can see, the molars have some crazy cusps on them, also known as “tubercles” hence the name. Their teeth are designed for chomping and crunching all kinds of vegetation. These teeth are very unique among mammals and probably helped them to have a generalist diet which would have aided them greatly in surviving the aftermath of the Chicxulub asteroid impact.

Anyways, Kimbetopsalis is a survivor and a cool little critter, much like Cro is. They lived among the largest land animals to ever walk the earth. They survived the horrifying event that saw an end to the Age of the Reptiles.

I dunno bout yall, but I just think that’s pretty neat.

#happy tree friends#htf#htf cro marmot#Dino-sore days#htf oc#maybe I’ll do a little science corner for all the prehistoric ocs#I love rambling about cool critters#paleo#loretime

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

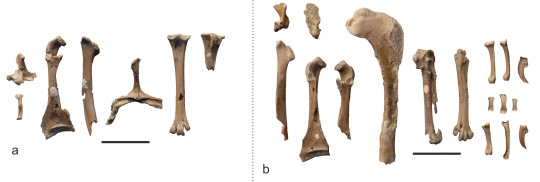

Waltonavis paraleptosomus Mayr & Kitchener, 2022 (new genus and species)

(Specimens of Waltonavis paraleptosomus [scale bars = 10 mm], from Mayr and Kitchener, 2022)

Meaning of name: Waltonavis = Walton-on-the-Naze bird [in Latin]; paraleptosomus = near [in Greek] Leptosomus [genus of the extant courol, L. discolor]

Age: Eocene (Ypresian), 54.6‒55 million years ago

Where found: London Clay Formation, Essex, U.K.

How much is known: Three partial skeletons, including partial skulls and various limb bones, and a tarsometatarsus (fused ankle and foot bones) from a juvenile individual.

Notes: Waltonavis was probably closely related to the extant courol (Leptosomus discolor), a tree-dwelling bird from Madagascar and the Comoros. Despite its restricted distribution today, the courol had close relatives that ranged widely during the Paleogene, with the Eocene genus Plesiocathartes being known from both Europe and North America.

Compared to Plesiocathartes, Waltonavis was smaller and appears to have been less closely related to the modern courol. Given its smaller size and narrower beak, Waltonavis probably also fed differently from the courol, which mostly preys on large insects and small reptiles (especially chameleons).

Waltonavis closely resembles Lapillavis, an enigmatic bird from the Eocene of Germany with uncertain affinities. This may suggest that Lapillavis was yet another close Paleogene relative of the courol.

Reference: Mayr, G. and A.C. Kitchener. 2022. New species from the early Eocene London Clay suggest an undetected early Eocene diversity of the Leptosomiformes, an avian clade that includes a living fossil from Madagascar. Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments advance online publication. doi: 10.1007/s12549-022-00560-0

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

We take evolution for granted. It is easy to imagine ourselves as the end goal, regardless of whereas there is a God or not. That the current state of affairs is the destined one.

But evolution is nothing if not chaos. Life is the result of many chances and happenstances, which resulted in our status quo. The most frequent “what if” scenario when imagining different possibilities of how life would have evolved different is perhaps the famous “what if [non-avian] dinosaurs never died out”, but I believe this project will illustrate this point even better.

In our timeline, Theria, the group of mammals composed of placentals, marsupials and any extinct cousins that descended from their last common ancestor, came to dominate the world. From the hopping kangaroos to majestic tigers, to the flying foxes and enormous whales, they’re the definition of “mammal” in most people’s minds.

But it wasn’t always like this.

Even today, monotremes still live in Oceania, but the beginning of the “Age of Mammals” actually had another group as far more dominant than therians: multituberculates. This ancient lineage were the most common and diverse mammals in the Mesozoic, and their entrance into the Cenozoic was promising: surviving a mass extinction event, they proliferated and came to dominate the mammalian fossil reccord for the first 5 million years.

But they declined rapidly, for reasons still poorly understood, giving way to therian mammals. This is why you’re here, and why only some paleontologists know what a multituberculate is.

So what if they didn’t die out?

Ectypodus arctos devouring a basal rodent by Dylan Bajda. Already a carnivorous animal, this scene could have taken place in both timelines, but in this one it heralds the end of placentals, and the era of the allotheres.

Table of contents

What is a multituberculate?

An alternate history:

Paleocene

Eocene

Oligocene

Animal Groups (note: only until Oligocene for now)

Multituberculate Diets

Multituberculate Saberteeth

Multituberculate Sounds

Kogaionidae

Taeniolabidoidea

Microcosmodontidae

Meniscoessidae

Ptilodontoidea

Djadochtather[i]oidea

Gondwanatheria

Flying Mammals

Sea Mammals

Marine Reptiles

Birds

Dryolestoidea

Monotremata

A world with no lizards

Alternate Timelines Of The Timeline

Nyctosaurid Earth

Meta

The three Multituberculate Earths

#speculative evolution#speculative biology#spec evo#multituberculate#multituberculata#allotheria#multituberculate earth

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hunting For Fossil Frogs In Wyoming

by Amy Henrici

Collection managers at Carnegie Museum of Natural History (CMNH) typically spend their time on collection-based tasks. Sometimes, however, we are called on to clean out the office of a former curator in our respective sections. With the death of Section of Vertebrate Paleontology (VP) Curator Emerita Mary Dawson late last year, I’ve been spending time in her office sorting through numerous items she accumulated during her nearly 58-year career at the museum. While there, I can’t help but think of a conversation we had in her office many years ago when I expressed interest in obtaining a Master of Science degree in geology and paleontology at the University of Pittsburgh.

Mary agreed to be my advisor and suggested fossil fishes as a topic for my thesis, because at that time not many paleontologists were studying this group. She arranged for me to join a field crew from our Section led by curators Kris Krishtalka and Richard Stucky who planned to spend the summer of 1984 searching Eocene sediments (~56–34 million years ago) in the Wind River Basin of central Wyoming for fossils of mammals and other vertebrates. She instructed them to take me to the north end of Lysite Mountain, where during a 1965 reconnaissance geologist Dave Love (of the United States Geological Survey [USGS]) and his student Kirby Bay and others showed her some fish fossils.

1965 reconnaissance of the north end of Lysite Mountain. The fish locality lies further below the group. Left to right, Dave Foster, USGS geologist Dave Love, Love’s student Kirby Bay, then CMNH VP Curator Craig Black, and Ted Gard. Photo by Mary Dawson, July 28, 1965.

As planned, in late June I set out from Pittsburgh in my un-airconditioned car on a three-day drive to Wyoming to join the crew who had arrived before me. Some of my time in the field was spent assisting the crew in their search for mammal fossils, something I had no experience with. My previous field work involved collecting ancient amphibian, reptile, and dinosaur fossils from the time before most mammals had evolved. Indeed, the first set of “fossils” that I collected on this trip turned out to be fragments of modern rabbit bones that Kris unceremoniously dumped into his ashtray while identifying the day’s haul after dinner. Fortunately, my skills at finding mammal fossils improved.

After a few days we went on the first of several reconnaissance trips to Lysite Mountain, which lies north of the Wind River Basin and forms part of the southern escarpment of the Bighorn Basin. To get there we drove deeply rutted and sometimes rocky dirt roads. Once there, the crew spread out in search of fossils. While some of us searched for and found incomplete and disarticulated fish fossils, others discovered a unit that produced frog fossils. When Kris and Richard showed me the frog fossils, they strongly urged me to base my thesis on the frogs instead of the scrappy fish I had collected. I quickly agreed, which was a decision that I never regretted.

We returned to our routine of prospecting for fossils in the Wind River Basin, until the planned arrival of Pat McShea (now my husband and Program Officer in the CMNH Department of Education) via a Trailways bus. The original plan was for Pat and me to drive my car daily to Lysite Mountain, but this was not feasible, given the condition of the roads. Instead the crew dropped us off with our camping gear for four days of fossil frog collecting. This was followed by a second field season in 1986, in which my sister, Ellen Henrici, joined us with her off-road capable SUV.

The frog quarry, with the Bighorn Basin below, to right of quarry. Photo by the author, 1984.

Using a hammer and chisel to pry open pieces of rock, we collected nearly 150 specimens of frog fossils in varying degrees of completeness. The preparation of the fossils and the identification of the various bones took me a long time. I eventually figured out that they were all the same type of frog and represented a new genus and species in the family Rhinophrynidae, which today is known by a single species: Rhinophrynus dorsalis, the Mexican burrowing toad. The fossil collection even includes tadpoles in various stages of development, as well as a mortality layer preserving the scattered bones of many individuals. I named this new genus and species Chelomophrynus bayi in a 1991 paper published in CMNH’s scientific journal, the Annals of Carnegie Museum.

Growth series of Chelomophrynus bayi, arranged in order of maturity from youngest (left) to oldest (right). The red arrow points to the thigh bone (femur). A tail, not preserved, would have been present in the tadpoles. Photos by the author, 2015.

Sample of the extensive mortality layer of Chelomophrynus bayi. Cause of death might have been disease. Photo by the author, 2021.

In paleontology, the study of living creatures can inform our understanding of fossils. The Mexican burrowing toad is very unusual in that it spends most of its life underground and only emerges to breed after heavy rain. The species currently inhabits dry tropical to subtropical forests along coastal lowlands in extreme southern Texas southward into Mexico and Central America. It has two bony spades on each hind foot that help it to efficiently dig, hind feet first, into the ground. Once underground, other skeletal specializations enable it to use its front feet and nose to penetrate termite and ant tunnels and then protrude its tongue into the tunnel to catch insects. Chelomophrynus possesses a number of these specializations (though some are not as well developed as in the modern Rhinophrynus), which strongly suggests that it too was able to burrow underground to feed on subterranean insects.

Rhinophrynus dorsalis, the modern Mexican burrowing toad. Image from the CMNH Section of Herpetology.

Partial hind foot of Chelomophrynus bayi, which preserves two bony spades that in life would have been covered in a keratinous sheath and used for digging feet-first into the ground. Photo by the author.

Rhinophrynids once occurred as far north as southwestern Saskatchewan, Canada around 36 million years ago. Their southward retreat to their current range could be because they apparently never developed the ability to hibernate in burrows, which would have protected them from seasonal sub-freezing temperatures which began developing around 34 million years ago.

The oldest rhinophrynid is Rhadinosteus parvus, a frog that lived with dinosaurs. In 1998, I was able to name and describe it based upon several late-stage tadpoles collected earlier from Dinosaur National Monument, Utah, a site where many of the dinosaurs on exhibit in CMNH came from. A cast of Rhadinosteus is displayed in CMNH’s Dinosaurs in Their Time gallery.

Amy Henrici is the Collection Manager in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to share their unique experiences from working at the museum.

111 notes

·

View notes

Link

Snakes, why did it have to be snakes!

Going on from my last post about Megalania, the largest known lizard, today’s post is about the aptly named Titanoboa, the largest snake known to science. A big apology to all of you those who hate snakes or suffer from ophidophobia (the fear of snakes).

In the Mid to Late Paleocene (66-55 million years ago), warm and wet conditions in what is now South America created the perfect environment for large reptiles to fill the vacant megafaunal niches formerly held by the now extinct non-avian dinosaurs. Titanoboa cerrejonensis was one of these reptiles, completely deserving the megafauna label. It could reach a length of 12.8 metres and weight of 1,135 kg (42 ft and 2,500 lb for any Imperial unit fans), far larger than any modern day comparisons, with the longest snake (the reticulated python) only reaching around 6.25 metres and the heaviest - the green anaconda - only stretching to a respectable 225 kg.

Like these two extant snakes, Titanoboa was probably a constrictor, crushing its prey to death and then swallowing it whole. As it was thought to live in swamps and wetlands, and because of fossils of Titanoboa teeth, scientists theorise that this massive snake could be mainly a fish-eater.

Large reptiles like this often require high temperatures to grow this large and maintain their bulk and so the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum provided these temperatures for creatures like Titanoboa. Ultimately though, these temperatures couldn’t last, and so this wonderful and fascinating snake is now only known from fossils, capturing the hearts and minds of us modern humans.

I do not own this video, I like reptiles and paleontology so I thought I would share. Check out Moth Light Media’s channel for more of this interesting paleo stuff. This is the second in a series on prehistoric reptiles, the first being Megalania. Why not stay around for more?

#megafauna#reptile#reptiles#facts#paleontology#snakes#boa#titan#south america#animals#paleocene#dinosaur#link#coolfacts

20 notes

·

View notes