#road work

Text

road signs/work birthday party theme

#png#transparent#transparent png#transparent pngs#transparent png objects#kidcore#toycore#toywave#yellow#orange#party#construction#road signs#road work#birthday party#party themes#imagine a party

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

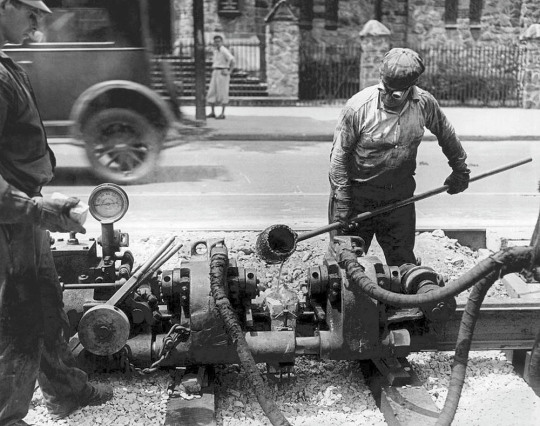

A hundred years ago today: road work in front of the NY Stock Exchange, April 12, 1923.

Photo: Standard Photographic Service/NYPL

#vintage New York#1920s#road work#road construction#Broad St. NY#Wall St.#vintage Wall St.#street photography#street scene#April 12#12 April

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

"You come here often?"

Rody x Coworker

crack ship that me and my friend have been thinking about-

I keep forgetting to post this version lmao-

Just added a few things rlly, nothing else

#rody dead plate#coworker elevator hitch#rody lamoree#coworker#rody x coworker#sea drifter draws#rodwork#road work

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Puhst. Alte Wilhelmsburger Reichsstraße, Hamburg 03/2021

Foto: Vanja Stockhausen

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tuesday, February 13, 2024

There’s utility work in front of the museum today. The building shook hard a few times but so far I haven’t noticed anything amiss.

#curator#museum#road work#construction#warning would have been nice#couldn’t have done anything anyways

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The world will stand still ... for road work

#Klaatu#Barada#Nikto#Robot#Flying saucer#Space Ship#The Day the Earth Stood Still#Road Work#Programmable#Signage#Electronic

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“The foothold created by prisoner-built roads in the Canal Zone enabled colonial officials, army engineers, and politicians in the United States to train their sights on a Pan-American Highway, which would run north-south from Alaska to Argentina. Convict road building in Panamá became part of the massively increased federal support for convict road building projects across states, territories, and colonies under US jurisdiction. Federal officials, meanwhile, pushed their modernizing agenda for prisons and roads at the convenings of international organizations like the Pan American Union (PAU) and the Pan American Prison Congress. The Pan-American Highway was shrouded in the rhetoric of hemispheric harmony, and PAU Director General L.S. Row described the “Good Roads Movement” as encapsulating “the very essence of true Pan-Americanism.”

E.W. James, chief of the inter-American regional office of the Public Roads Administration, promised the highway would open up great tracts of land and offer US motorists scenes of “exotic interest,” discovery, and adventure. Probably “no white man” has ever traveled between Central and South America overland, he wrote referring to the Darién Gap between Panamá and Columbia. He provided a list of voyages along portions of the highway, including that of Zone policeman 88, Harry A. Franck. At the 1915 Panama-Pacific World’s Fair in San Francisco, the US Office of Public Roads staged the most comprehensive road exhibit to date. By the end of World War II, the inter-American portion between the United States and Panamá included 1,557 miles of paved roadway, 930 miles of all-weather, 280 miles of dry-weather, and 567 miles of trails. “The last quarter century in the Western Hemisphere has been preeminently an era of road building,” James proudly concluded.

Forced transportation was central to the chattel mode of incarceration, along with degrading hard labor. Throughout the period of US canal construction, 1904–1914, police and prison officials routinely deported people from the Zone. Indeed, when he was appointed police chief, George Shanton saw it as his first order of business. Before he was even expressly granted expanded deportation powers, he gathered members of Teddy Roosevelt’s “Rough Riders” and other “American gunmen” to round up any “bad men” in the newly occupied territory.

“We went after them and some we found necessary to kill off but the great majority were gradually rounded up and placed in the stocks, later being put into bull-pens which we constructed,” he told the Boston Globe years later. “The next thing to do was to get them out of the country altogether,but we were in a position where we could not legally deport them. So we rounded up some old three masters […] and, bundling the birds all aboard, shot them off to the Islands thereabout.”

His nonchalance masked a more systematic process of targeted depopulation that combined Spanish-speaking Afro-Panamanians, French-speaking Martinicans, and English-speaking Jamaicans and Barbadians under the general category of “negro criminal,” who were then indiscriminately sent off to neighboring Caribbean islands. “With them out of the Zone,” Shanton wrote, “we were then in a position of refusing them entrance should they attempt to return.”

Canal Zone District Attorney William Jackson argued that the “great expense” the government had incurred by paying to transport some twenty thousand workers from Barbados and elsewhere in the West Indies “abundantly justified” expanded powers of deportation and judicial cost savings measures. The Canal Zone government paid the cost of deportation, he added, and rightly recouped the “enormous expense incident to jury trials.” As with other labor recruitment contracts, some officials worried they were skirting a line too near slavery. Responding to John Steven’s request to import more Chinese laborers, for instance, Secretary of War William Taft wrote, “peonage or coolieism, which shortly stated is slavery by debt, is as much in conflict with the Thirteenth Amendment of the Constitution as the usual form of slavery.” Others were less concerned. Despite apparent ambiguities in charting these degrees of unfreedom, they knew for certain that the Thirteenth Amendment’s convict clause provided that those convicted of a crime would become slaves of the state. Following a paradigm of patriarchal governance, Canal officials also assumed that other forms of dependent or coerced labor—of women, children, and colonial subjects—were part of the natural order of things. Evidently paying the passage of a small fraction of the total Canal Zone workforce had metaphorically, if not contractually, already indentured much wider segments of the population in the eyes of certain administrators.

...

The police and prison guards charged with implementing the forced labor program brought their own ideas about dependency, deviance, punishment, and work. Racialized labor control schemes had been vitally important to their jobs throughout the American empire. Zone policemen like Harry Franck and Robert Lamastus remarked that their fellow officers were mostly Southerners and almost all military men. Police Chief George Shanton, for instance, had served in the Rough Riders during the US wars in Puerto Rico and the Philippines. His successor had been a Confederate blockade runner, and the police chief after him was a former US Marshal in Indian Territory. When a police chase was on, wrote Harry Franck, everyone from the lieutenant down to the newest rookie would swarm out of the police station: “[T]he most apathetic of the force were girding up their loins with the adventurous fire of the old Moro-hunting days in their eyes, and all, some ahorse, more afoot, were dashing one by one out into the night and the jungle.” With this turn of phrase, Franck evoked the experience of colonial violence from fighting in the predominantly Muslim region of the Philippine archipelago to characterize the rush of tracking alleged outlaws in the Panamanian jungles as a kind of manly “adventure.”

Robert Lamastus, who was put in charge of working prisoners outside the penitentiary, exemplified many of these elements guards brought to the road gangs. With his family back in Kentucky, heavily indebted after the Civil War, he had gone fortune-seeking in the far reaches of the Northwest, joining the army in Alaska. He dreamed of striking it rich prospecting for gold or purchasing land to clear and cultivate. Yet his letters home made clear that he envisioned himself directing rather than performing hard physical labor; referring to farm work, for example, he exclaimed that there were “plenty of easier ways of making a living besides working like a slave for it.” Lamastus joined the police force in 1907 and was rapidly promoted. Within two years he was making $107.50 per month, five times what he earned when he first enlisted in the army, and the following year he received an additional $10 a month to serve as labor foreman over prisoners at Culebra. “We are building roads with them,” he wrote home, “I start work at 7 in the morning and I am through 5:30 in the evening.”

After successfully completing his road building assignments in the town of Empire, he was made Assistant Deputy Warden in charge of all outside work. “I was promoted on the 19th of Dec. my pay is $125 per mo.” he proudly wrote home. In addition to his salary, as Gold Roll employees, white police and prison officers like Robert Lamastus also received the full range of government benefits including paid housing, health care, and vacations. The racially segregated social and economic hierarchies he and his colleagues helped establish in the Canal Zone therefore ensured that white American men, as a group, would stand to gain the most from the incarceration and forced labor of Zone inhabitants deemed criminals.

The Canal Zone governors, wardens, police, and prison guards who implemented the prison labor program drew on techniques of labor extraction and domination that had characterized the American expansion under slavery, settler colonialism, and war-making. While they were not all members of the ex-Confederate diaspora who sought to spread white supremacy across the Caribbean to Brazil, or across the Pacific to Hawaii, Fiji, and Australia, most shared lived experiences of slavery and colonial violence. They also shared a vision of patriarchal mastery and racial hierarchy in which white men assumed themselves to be the head, performing mental and skilled labor, and racialized others to be the body, performing unskilled, physically demanding, menial labor. Their vision of white settler-colonial agricultural development depended on roads being built throughout the Zone and across Panamá. It also provided prison administrators and guards a unique avenue of upward social mobility. After a career commanding prison labor in the Canal Zone and directing the Panamanian island prison colony at Coiba, for example, Robert Lamastus went on to set up coffee plantations in Boquete, Chiriqui, that have remained in his family to this day.”

- Benjamin D. Weber, “The Strange Career of the Convict Clause: US Prison Imperialism in the Panamá Canal Zone,” International Labor and Working-Class History No. 96, Fall 2019, p. 88-90, 91-92.

Image at top is: “Road Making by Convicts” from Willis J. Abott, PANAMA And the Canal IN PICTURE AND PROSE. New York: Syndicate Publishing Company, 1913. p. 352.

#panama canal#canal zone#thirteenth amendment#convict clause#convict labour#american prison system#american empire#u.s. imperialism#penal labour#slavery by another name#settler colonialism#road building#road work#prison camp#good roads movement#bad boys make good roads#academic quote#academic research#history of crime and punishment#united states history#prison guards#racism in america#shoveling out the unwanted

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maverick: Croissants: dropped

Rooster: Road: works ahead

Hangman: BBQ sauce: on my titties

Bob: Shavacado: fre

Phoenix: Miss Keisha: fuckin dead

Cyclone, who just wanted a normal morning for once: I didn’t understand a single word of that, and I hate every single one of you.

Warlock, with a deadpan expression: Bitch: didn't hesitate.

Cyclone: Seriously? You too?

#maverick top gun#top gun#maverick#rooster#hangman#phoenix#bradley bradshaw#iceman#incorrect quotes#bob#jake seresin#top gun 2#top gun maverick#croissants#road work#bbq sauce#shavacado#miss keisha#cyclone#warlock

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

when u pass construction

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A workman is pouring molten borax into the opening where two streetcar rails join together, ca. 1927. This was part of the track-welding program to reduce noise in the city.

Photo: Underwood Archives via Fine Art America

139 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Heavy equipment used to work on a highway bridge over the Hudson River in New York.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The road work is a block away now...!

How will we get out when it gets here.

#road work#done this fall?#needed to be done#we were like this road is 3rd world road#by college#hard to fix#also narrow#aaaaaaaaaah#i think they have it worked out#at least its not a sinkhole in the intersection neae our yard

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Material World. Georg-Wilhelm-Straße, Hamburg 05/2023

Foto: Vanja Stockhausen

#hamburg#photographers on tumblr#original photography#wilhelmsburg#hamburg wilhelmsburg#street photography#35mm#building materials#road work

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

heads up: this games charity bundle was finally approved on itch.io! it opens this friday, april 12th, and will run for a week. all proceeds will go to the Palestinian Children's Relief Fund.

you can check out the bundle on itch.io and follow @vgforpalestine on twitter for more updates!

—

EDIT: as of april 20th, 2024 this bundle is now live!!

#free palestine#itch.io#charity bundle#video games for palestine#palestinian relief bundle#pan talks#just got the email that the project is finally live after a couple tehcnical hiccups and itchio road bumps here and there#they said we could share so i figured i'd post abt it here on tumblr since it appears that they're not on here o7 please boost!#i have a zine in this one but please be sure to check out all of the work

18K notes

·

View notes