#shenmo

Text

「係呀,齊天大聖同埋牛魔王都係噉講㗎!」

“Yeah, the Great Sage Monkey God and Bull Demon King said so too!”

「你應該知嘅喎!」 (指緊陳秀珠[右]↓)

“You should know!” (pointing to Rebecca Chan, lady on the right ↓).

(Another) inside joke here? 😸

Rebecca Chan played Princess Iron Fan, wife of Bull Demon King, in TVB's Journey to the West 《西遊記》 (1996 & 98) series. ↓

Context: The man talking about Great Sage Monkey God (aka Sun Wukong) and Bull Demon King is playing a character who's not quite right in the head.

《師奶強人》 (1998) 第三集

#TVB#Cantonese#HK Drama#As Sure as Fate#Kwok Fung#Rebecca Chan#JTTW 1996#Journey to the West#Shenmo#Chinese Language#Language

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Stealth Cinematic Adaptation of Peach Blossom Girl 桃花女

(This post was originally appeared as a Twitter thread on 14 October 2020 and is reproduced here with minor edits.)

I’d like to talk briefly about my favorite of the live-action Disney adaptations of Chinese folk tales: the story of the Peach Blossom Girl’s defeat of the Duke of Zhou in a battle of magic, adapted, of course, into the Star Wars sequel trilogy. (No, not really. But I was struck by the similarities while watching The Rise of Skywalker, and I’d like to imagine that some of the films’ more perplexing narrative choices are in fact a consequence of adapting a centuries-old folktale into a sprawling space opera.)

A summary for those unfamiliar with the tale: Zhougong 周公, the Duke of Zhou, is associated with the Book of Changes, oneiromancy, and other mantic techniques. In this story, he runs a divination shop, and for 30 years has never been wrong (he’s got a money-back guarantee). Then his predictions begin to fail. He foresees a widow’s merchant son, Shi Zongfu 石宗辅, dying in a pit, but the man returns home safely; he predicts that his servant Pengjian 彭剪 will die in three days, but instead his life is extended. Infuriated, Zhougong quits the business.

His nemesis turns out to be Taohua nü 桃花女, the Peach Blossom Girl, a local teenager who not only excels him in divination but is also a sorcerer who can manipulate fate. He vows revenge. Forcing her to marry his son on an ill-omened day, he calls on deities to kill her.

She beats him at every turn: counters his curses, tricks a tiger spirit into killing his daughter (whom she later resurrects), and even arranges her own resurrection after he attacks the peach tree holding her life essence. Each humiliating defeat only enrages him further. The feud culminates in Zhougong’s death, but at his household’s request, Taohua revives him.

I've taken most of the details in this summary from a short novel of uncertain authorship, 桃花女阴阳斗传 (Taohua’s Battle of Yin and Yang, among other titles), published in 1848, which casts the story into the shenmo 神魔 “gods and demons” mode. But the story exists in many forms.

The earliest in print is a Yuan dynasty zaju play attributed to Wang Ye 王晔, found in Ming collections under the title “Taohua, adept in the yin-yang trigrams” 讲阴阳八卦桃花女 (脉望馆 version) or “Taohua defeats magic, marries Zhougong” 桃花女破法嫁周公 (元曲选 version).

“Miss Irisation breaks the plum formation” 云来姐巧破梅花阵 from the late Ming collection 贪欣误 tells the same tale using different character names.

In the story “Taohua fights using magic” 桃花女斗法, in the 1846 zhiguai collection 闻见异辞, the two fight with bees, tigers, and spiders.

There’s also a wide range of local operas and folk ballads, as well as a proliferation of 20th century adaptations into different media.

Turning to the Star Wars sequels, we can recognize the major characters at once, although existing canon did force some minor tweaks.

◎ Kylo Ren is Zhougong. Born into a noble family and trained in divination from a young age, Zhougong sets out on his own when the royal court rejects his counsel. He’s arrogant and vindictive, and he cares more for proving his dominance than for the lives of people close to him.

◎ Rey is Taohua. Born to commoners, she lives in seclusion until her late teens, when compassion for her neighbors moves her to use her talents, attracting Zhougong’s attention. She wields a peach branch that expands into a halberd, preserved in the film as Rey’s staff.

◎ Finn is Shi Zongfu, a merchant traveling far from home who is saved from certain death by Taohua’s intervention. The first half of the novel is largely his story, but after he demands compensation from Zhougong for the inaccurate prediction of his death, he drops out of the narrative altogether.

In a 1957 lianhuanhua retelling that recasts the tale as one of class struggle, Shi (here known as Shi Ji) is fleeing a forced labor corps when Taohua rescues him. They fight against Zhougong’s cruel, exploitative regime as a romantic pair. (Read it online.)

◎ Pengjian, Zhougong’s servant, doesn’t have an exact counterpart. Using the spells Taohua taught him, not only does he escape immediate death, he also extracts an additional 850 years of life from stellar deities, becoming Peng Zu 彭祖, an enduring symbol of longevity.

Star Wars’ resident multicentenarian, Yoda, is unfortunately of the wrong alignment and, by the sequel trilogy, already dead. After Taohua saves him, Pengjian acts on her behalf and betrays Zhougong’s schemes—Hux, basically. Like Yoda and Hux, Pengjian is a comic character.

◎ To trap Taohua, Zhougong invokes the Black Killer 黑煞, a powerful protector god. Taohua counters by invoking the Red Killer 红煞. The two gods neutralize each other but agree not to actively interfere in the fight between Zhougong and Taohua.

Instead of pitting the two champions head-to-head, The Last Jedi time-shifts the confrontation: as the Black Killer, Snoke’s big moment is getting killed off, while Luke, the Red Killer, responds to a cry for help by deflecting an attack with his enlightened nonviolence.

◎ As it turns out, Taohua isn’t a nobody—she’s really an immortal sent to stop Zhougong from revealing too many secrets. The two are a divine pair—a yin-yang dyad, if you will, avatars of a knife and sheath lost when the god Zhenwu disemboweled himself in a purification ritual.

The Daoist god Zhenwu 真武, the “perfect warrior,” is also known as Xuanwu 玄武 “dark warrior” and has the title 玄天上帝 “high emperor of the dark heavens.” He’s identified with the god of the north, Heidi 黑帝, the “black emperor.” Here’s an appearance over Mt. Wudang in 1413:

Zhenwu isn’t in all versions of the tale, but if the trilogy must have a final boss, he’s the only logical choice—even if the moral dualism of the Star Wars universe requires him to be evil. The films’ lineage of evil black-robed mages practically demands the Emperor’s return. Palpatine’s death in the original trilogy isn’t a problem, either. Zhenwu has many incarnations—at one point in the late Ming novel Journey to the North 北游记, he’s killed by the avatar of the spirit of Guan Yu’s glaive, and his companions have him resurrected to continue his mission.

When it comes to ending the story, It can’t be denied that the adaptation does stumble a bit.

① Shock reveals.

Like other literary adaptations of the period based on well-known folk myths, the novel opens with background on Taohua and Zhougong and their relationship to Zhenwu. Play audiences would have been familiar with their roles as well, so Zhenwu’s abrupt appearance on the last page of the 脉望馆 edition to reclaim his charges wouldn’t have come out of nowhere. (The 元曲选 edit omits the god altogether and never clearly explains the source of Taohua’s power.) By moving the core story to an unfamiliar setting in a galaxy far, far away, the adaptation can’t rely on shared cultural knowledge, meaning a long-dead villain’s unheralded return or a reversal where a character who’s been a nobody for most of the story turns out to be the chosen one feel contrived and unearned.

② The overstuffed ending.

After Zhougong’s total humiliation, there are lots of options for the folktale’s conclusion. In some, Taohua accepts marriage into a humbled Zhougong’s house; in others, he keeps battling her until the gods intervene. Here’s a comparison of the two versions of the scene following Zhougong’s resurrection

From the Yuan play:

(Zhougong and his children rise.)

TAOHUA

Zhougong, why aren’t you counting trigrams?

ZHOUGONG

Don’t you mock me, too. I’ve got to tell you, Taohua, today I was convinced my magic was great, but I never imagined yours would be greater still, a hundred times greater than mine. I never had a chance of beating you. Come, be my daughter-in-law and you won’t suffer by it. Let’s have the wedding banquet today, and may there be harmony between our families.

TAOHUA

Under the circumstances, harmony it is.

(From Act 4 of 脉望馆 edition)

From the Qing novel:

Zhougong’s soul returned to his corpse, and he flipped over and sat up on the ground. His eyes blazed hate at Taohua as he sprang up and seized his star-sword, shouting, “Halt, demon woman! You presume to recall my soul? I swear on my life to put you to death!” He advanced on her with his sword. Taohua pulled the compliant peach branch from her silk bag and blocked him. “This is the thanks I get for saving your life, Zhou Qian? You think you can bully me?” Again he swung his sword, but she dodged and parried with her branch, yin and yang clashing in the great hall. [. . .] Zhougong and Taohua fought from the doorway to the courtyard, but the space was too cramped to use their full powers, so they mounted clouds and battled each other into the air. [. . .] Everyone else watched them from the ground. Wreathed in rosy clouds, they waged a savage battle in the sky, receding into the distance until they finally disappeared. [. . .] The fight reached a fever pitch as they tapped every skill they possessed. The roar and thunder of their struggle alerted the Grand Coordinator-Censor who, noticing the ferocity of their fight and their proximity to the North Gate of Heaven, hurried to inform the high emperor of the dark heavens, Zhenwu. The emperor peered through his wisdom eye and understood all that had happened. He dispatched general Tortoise and general Snake to bring the two to him.

(From Chapter 16)

Having Taohua and Zhougong reconcile after she’s put him in his place (and reversed all his harm) makes sense in a wedding comedy meant to create an origin story for rites and taboos and to subvert the trope of the passive, reluctant bride. The novel is more fascinated with the magical duel. It replaces Zhougong’s contrition with a heavenly intervention, recalling the two from the mortal realm and binding them to their celestial duties with a golden elixir that will dissolve their bodies if they stray again.

The film adaptation combines the two endings, working a quick redemption for Kylo (and reconciliation with Rey) into the same epic battle that leads to what’s more or less an exit from the mortal realm—him into death, her to the isolated home of her mentor and protector. The two versions of the story aren’t really compatible, and by attempting both, the film doesn’t make either convincing.

As an aside, one odd thing about the folktale is that while the Taohua and Zhougong are clearly the central dramatic pairing, age and propriety mean the marriage proposal is made on behalf of his son, who barely appears. In the Yuan play, he has no lines and comes on stage only to die. In the novel he doesn’t even exist: Zhougong only pretends to have a son. Most adaptations pair the two directly, such as this Taiwanese opera starring Xiao-mi 小咪 as a more sympathetic Zhougong and Huang Yang-hua 黄旸骅 as Taohua.

Which brings us to the next problem:

③ No songs!

To the novel’s assortment of incidental poems and plot-specific spells invoking various deities, the author adds an actual song to pass the time while Shi Zongfu’s mother is waiting to recite Taohua’s spell to call her son out of the deadly pit. And the dramas are chock full of tunes. Imagine if, in response to Kylo’s “Join me,” Rey were to launch into a version of the kiss-off song that’s Taohua’s answer to Zhougong’s marriage proposal (the text here is the more dramatic edit by Zang Maoxun 臧懋循 in 元曲选):

【笑和尚】我、我、我,不恋你居兰堂住画阁,我、我、我,不恋您列鼎食重裀卧,我、我、我,不恋您那雪花银三十个。(媒婆云)那周公算的��《周易》课,只有他家大官人晓得,再不传别人的。姐姐,你过门之后,他还要传这《周易》课与你哩。(正旦唱)他、他、他,论阴阳少讲习,我、我、我,论卦爻多参破,休、休、休,我根前,(做推媒婆跌科,唱)还卖弄甚么《周易》的课。

TAOHUA

(singing)

I, I, I don’t care about your halls and galleries.

I, I, I don’t care about your life of luxury.

I, I, I don’t care for the silver you say that you’ll give to me.

MATCHMAKER

Zhougong’s Changes, mantic methods he alone has access to—Take his offer, join his house; he’ll gladly share that art with you.

TAOHUA

He, he, he knows nothing of the craft of prophecy.

I, I, I have mastered all the trigrams’ mysteries.

Stop, stop, stop—

(pushes Matchmaker to the ground)

Flogging those oversold, useless old Changes to me!

Or maybe not, considering that Star Wars as a franchise doesn’t have the greatest track record for songs sung by humans. Still, that’s just one of the countless ways to make a cross-genre adaptation of a folktale do justice to the original while also taking advantage of the huge canvas of a new fictional universe. The Taohua-Zhougong story is a small domestic drama, after all, without the sweeping scale of other shenmo quest or war novels. Grafting it onto a standard Star Wars climax retread shrinks the new universe rather than expanding the source material to fill the new space.

There’s bound to be a satisfying way to make all the elements work, although it would likely take some clever plotting to make the square peg of a wedding comedy for dueling Daoist immortals fit the round hole of a space station exhaust port. ■

——————————

This post is one reader’s take on the tale of Taohua and Zhougong. I’m not a specialist in Yuan theater, Daoism, or late imperial vernacular literature, so all corrections are welcome. You’re also free to challenge my misreading of Star Wars, but please know that I’m not especially interested.

Further reading

Vincent Durand-Dastès, “Divination, Fate Manipulation and Protective Knowledge In and Around ‘The Wedding of the Duke of Zhou and Peach Blossom Girl’, a Popular Myth of Late Imperial China” for more on the novel and its magical elements.

Variations of the Peach Blossom Girl myth are covered in a 2012 master’s thesis by Guo Fan 郭帆, 《“桃花女”故事研究》 ; There’s also a 1992 master’s thesis by Liu Huiping 刘惠萍, 《桃花女斗周公故事研究》 that I haven’t seen.

A cool 2008 PhD thesis on Zhenwu iconography by Noelle Giuffrida, “Representing the Daoist God Zhenwu, the Perfected Warrior, in Late Imperial China”.

Sources

Character woodcuts from the British Library’s copy of the 丹柱堂 reprint of the 1848 联益堂 edition of 桃花女阴阳斗传, as photoreproduced in 古本小说丛刊第四辑 (中华书局, 1990).

Illustration of Pengzu praying to the stars from 元曲选 digitized from the Harvard-Yenching collection.

Yuan zaju play: The 元曲选 version is readable on Gushiwen.org; the text of the 脉望馆 version isn’t online but the manuscript version is reproduced in 古本戏曲丛刊第4集第25册.

Zhenwu and the knife spirit image from the 1602 edition of 北方真武祖师玄天上帝出身志传 (北游记) reproduced in 故本小说集成 (上海古籍出版社), page 129.

Appearance over Wudang image from 大明玄天上帝瑞应图录 held by Bibliothèque Nationale, available online.

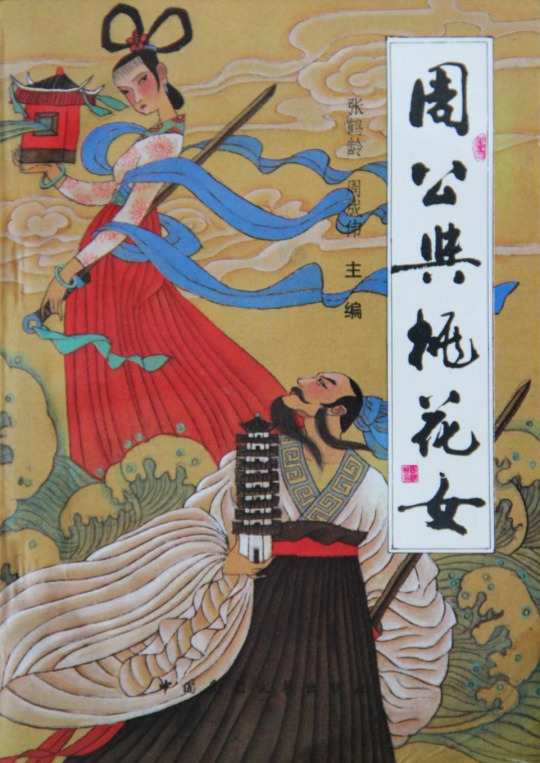

Book cover for 周公与桃花女 from the 1989 中国民间文艺出版社 title by by 张鹤龄 and 周成伟. 1957 lianhuanhua 桃花女 adapted by 江澄 and illustrated by 盛焕文 and 盛鹤年, published by 江苏人民出版社. Available online.

0 notes

Text

So You Want to Read More about Chinese Mythos: a rough list of primary sources

"How/Where can I learn more about Chinese mythology?" is a question I saw a lot on other sites, back when I was venturing outside of Shenmo novel booksphere and into IRL folk religions + general mythos, but had rarely found satisfying answers.

As such, this is my attempt at writing something past me will find useful.

(Built into it is the assumption that you can read Chinese, which I only realized after writing the post. I try to amend for it by adding links to existing translations, as well as links to digitalized Chinese versions when there doesn't seem to be one.)

The thing about all mythologies and legends is that they are 1) complicated, and 2) are products of their times. As such, it is very important to specify the "when" and "wheres" and "what are you looking for" when answering a question as broad as this.

-Do you want one or more "books with an overarching story"?

In that case, Journey to the West and Investiture of the Gods (Fengshen Yanyi) serve as good starting points, made more accessible for general readers by the fact that they both had English translations——Anthony C. Yu's JTTW translation is very good, Gu Zhizhong's FSYY one, not so much.

Crucially, they are both Ming vernacular novels. Though they are fictional works that are not on the same level of "seriousness" as actual religious scriptures, these books still took inspiration from the popular religion of their times, at a point where the blending of the Three Teachings (Buddhism, Daoism, Confucianism) had become truly mainstream.

And for FSYY specifically, the book had a huge influence on subsequent popular worship because of its "pantheon-building" aspect, to the point of some Daoists actually putting characters from the novel into their temples.

(Vernacular novels + operas being a medium for the spread of popular worship and popular fictional characters eventually being worshipped IRL is a thing in Ming-Qing China. Meir Shahar has a paper that goes into detail about the relationship between the two.)

After that, if you want to read other Shenmo novels, works that are much less well-written but may be more reflective of Ming folk religions at the time, check out Journey to the North/South/East (named as such bc of what basically amounted to a Ming print house marketing strategy) too.

-Do you want to know about the priestly Daoist side of things, the "how the deities are organized and worshipped in a somewhat more formal setting" vs "how the stories are told"?

Though I won't recommend diving straight into the entire Daozang or Yunji Qiqian or some other books compiled in the Daoist text collections, I can think of a few "list of gods/immortals" type works, like Liexian Zhuan and Zhenling Weiye Tu.

Also, though it is much closer to the folk religion side than the organized Daoist side, the Yuan-Ming era Grand Compendium of the Three Religions' Deities, aka Sanjiao Soushen Daquan, is invaluable in understanding the origins and evolutions of certain popular deities.

(A quirk of historical Daoist scriptures is that they often come up with giant lists of gods that have never appeared in other prior texts, or enjoy any actual worship in temples.)

(The "organized/folk" divide is itself a dubious one, seeing how both state religion and "priestly" Daoism had channels to incorporate popular deities and practices into their systems. But if you are just looking at written materials, I feel like there is still a noticeable difference.)

Lastly, if you want to know more about Daoist immortal-hood and how to attain it: Ge Hong's Baopuzi (N & S. dynasty) and Zhonglv Chuandao Ji (late Tang/Five Dynasties) are both texts about external and internal alchemy with English translations.

-Do you want something older, more ancient, from Warring States and Qin-Han Era China?

Classics of Mountains and Seas, aka Shanhai Jing, is the way to go. It also reads like a bestiary-slash-fantastical cookbook, full of strange beasts, plants, kingdoms of unusual humanoids, and the occasional half-man, half-beast gods.

A later work, the Han-dynasty Huai Nan Zi, is an even denser read, being a collection of essays, but it's also where a lot of ancient legends like "Nvwa patches the sky" and "Chang'e steals the elixir of immortality" can be first found in bits and pieces.

Shenyi Jing might or might not be a Northern-Southern dynasties work masquerading as a Han one. It was written in a style that emulated the Classics of Mountains and Seas, and had some neat fantastic beasts and additional descriptions of gods/beasts mentioned in the previous 2 works.

-Do you have too much time on your hands, a willingness to get through lot of classical Chinese, and an obsession over yaoguais and ghosts?

Then it's time to flip open the encyclopedic folklore compendiums——Soushen Ji (N/S dynasty), You Yang Za Zu (Tang), Taiping Guangji (early Song), Yijian Zhi (Southern Song)...

Okay, to be honest, you probably can't read all of them from start to finish. I can't either. These aren't purely folklore compendiums, but giant encyclopedias collecting matters ranging from history and biography to medicine and geography, with specific sections on yaoguais, ghosts and "strange things that happened to someone".

As such, I recommend you only check the relevant sections and use the Full Text Search function well.

Pu Songling's Strange Tales from a Chinese Studios, aka Liaozhai Zhiyi, is in a similar vein, but a lot more entertaining and readable. Together with Yuewei Caotang Biji and Zi Buyu, they formed the "Big Three" of Qing dynasty folktale compendiums, all of which featured a lot of stories about fox spirits and ghosts.

Lastly...

The Yuan-Ming Zajus (a sort of folk opera) get an honorable mention. Apart from JTTW Zaju, an early, pre-novel version of the story that has very different characterization of SWK, there are also a few plays centered around Erlang (specifically, Zhao Erlang) and Nezha, such as "Erlang Drunkenly Shot the Demon-locking Mirror". Sadly, none of these had an English translation.

Because of the fragmented nature of Chinese mythos, you can always find some tidbits scattered inside history books like Zuo Zhuan or poetry collections like Qu Yuan's Chuci. Since they aren't really about mythology overall and are too numerous to cite, I do not include them in this post, but if you wanna go down even deeper in this already gigantic rabbit hole, it's a good thing to keep in mind.

#chinese mythology#chinese folklore#resources#mythology and folklore#journey to the west#investiture of the gods

2K notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I don’t know if you happen to know, but I’m trying to research Journey to the South (as I am currently reading Journey to the West) but I can’t seem to find any translations of it available to an English speaking audience. Would you happen to know of any translations?

Thank you

Funny enough I happen to know quite a bit! I helped create and edit the JTTS pdf together and it is publically available thanks to @journeytothewestresearch

Feel free to enjoy!

#ask#jttw#journey to the west#xiyouji#jtts#journey to the south#yuebei xing#jidu#louhou#Rahu#Ketu#sun wukong

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

this project is set in what is to other people a pretty ordinary shenmo low fantasy setting, it's a normal day in the northern song dynasty with a normal amount of ghosts and demons, but my main character comes from a sect so confucian that he specifically is experiencing the setting as urban fantasy

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

Me sorprende que Macaque este de acuerdo que nombre a los niños por fanchilds de un fanfic del Viaje al oeste (Viaje al sur)

translated via google:

"I'm surprised that Macaque agrees that I name the children after fanchildren from a Journey to the West fanfic (Journey to the South)"

I feel like Macaque didn't even know about "Journey to the South" unless he was specifically looking for information about Sun Wukong online. XD

He would definetly know about and read "Journey to the West" just to get an idea of how the world remembers his and Wukong's story. But I don't think he'd know about the non-canonical fan sequels. As a goof I could see Macaque googling whether or not Wukong had kids and/or romantic partners in the last 1000 years and getting "Journey to the South" as a result. He'd be very confused.

Macaque: "So... you've had kids?"

Wukong, chokes on water: "W-what?!"

Macaque: "The other book told me you had like three kids. One really big scary daughter, and a pair of twin sons that didn't do much."

Wukong (has read every adaptation of Jttw there is): "...OH! You mean the fan-sequel! That was written in the 1580s by some guys I didn't even know. It's part of a four-book shenmo series about another chinese folk hero. I only get mentioned in like two chapters."

Macaque, six ears flutter: *is relieved to know SWK is telling the truth* "...ok, that definitely explains some things."

Wukong, cheeky smile: "Were you worried that I had kids without you?" ( ¬‿¬)

Macaque, tsundere-mode: "N-no! I was worried that some poor child had inherited your stupidity!" ( っ- ‸ – c)

Wukong: "Big words coming from someone having a baby with me."

Macaque: *is pregnant with MK during the AU* " "...touché"

Many years later as they're planning for more kids.

Macaque: "I'm a little stuck on names right now. My brain keeps going to weird theatre characters."

Wukong: "How about Yuebei for a girl?"

Macaque: "....lunar apogee? You mean like when the moon is farthest from earth?"

Wukong, doesn't want to admit that he's read all Jttw fanfics and liked the name: "Ye... yeah. I wanna keep the space theme names a thing."

Macaque: "....it is a really cute name. Let's keep it for if we have another girl."

Wukong: *phew!*

Later once Yuebei and the Lunar Node Twins are born.

Macaque, holding Yuebei: "You totally named our kids after fanfic characters didn't you?"

Wukong, holding the twin boys: "Haha! Wondered how long 'til you noticed!"

Macaque: "Jerk. Now I'm attached to the names."

Wukong: "In my defence you were gonna name the boys Castor and Pollux."

Macaque: "That was until I discovered that they wouldn't be Geminis."

Wukong: "Gods, we're both nerds."

Macaque, lovingly: "Yeah..."

#the monkey king and the infant au#the monkey king and the infant#lmk shadowpeach au#shadowpeach being parents#shadowpeach#pregnancy tw#lmk yuebei xing#yuebei xing#journey to the south#lmk lunar nodelets#lmk jidu and luohou#jidu and luohou#lmk au#lego monkie kid#lmk fan children

46 notes

·

View notes

Note

hello ^^/! I found your art semi recently and have become a huge fan of your style and characters! A question: what are ur inspirations/influences behind Huran Enki? love the historical references in your art, just wondering what else fuels it!

omg thank you <33

so Huran Enki is narratively inspired by works from antiquity like Greek tragedies, shenmo novels and epic poems like The Secret History of the Mongols, the Epic of Gilgamesh, etc... basically every desperate or twisted aspect of human behaviour that interested me, i put it into Huran Enki.

for visual inspiration i look at a lot of irl artworks from these eras plus the landscapes/peoples/textiles/clothing/patterns of the steppes of West Asia and Central Asia! and then it all gets filtered thru my eyes and what im capable of drawing. i try to keep the influences varied... use things i see in-person or in books etc rather than exclusively online... oh also cant forget to mention the manga/anime influences from like Gundam, Utena, Princess Tutu, Shut Hell, Fate, and more :3

i would love to read more epic poems like Beowulf and the Mahabharata and keep feeding things to my story!

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rewatched sporadic episodes of 《新白娘子傳奇》 (2019) (“New Legend of the White Snake”),

and there's this character 景松 (Jǐng Sōng) — who's some kind of rodent spirit-creature (妖 yāo), a 「金鼠」, direct translation, ‘Golden Rat’ — who's friends with 白蛇 (White Snake) and 青蛇 (Green Snake) and regularly hangs out at their residence.

And it just occurred to me, if he's some kind of 鼠 🐁 and they are 蛇 🐍, that would make them 🤭 quite literally:

🐍蛇鼠一窩🐁

🇭🇰🇲🇴 se⁴ syu² jat¹ wo¹

🀄 ㄕㄜˊ ㄕㄨˇ ㄧˋ ㄨㄛ | 🀄 shé shǔ yì wō

Literal meaning: snakes and rats in one den.

Meaning: (usually two) groups of people colluding together with bad/harmful intentions to others.

#Side note: I know much of it is probably CGI but I really love the#Interior and decor of the 白府,giving off such calm and soothing vibes#NLotWS 2019#Eps 5 and 6#Legend of the White Snake#Shenmo#C Drama#Mandarin#Cantonese#Chinese Language#Language

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Other Fantasy Subgenres:

Anthropomorphic Fantasy: anthropomorphism is the attribution of human characteristics, languages, behaviors, and motivations to an entity other than human. This something may be an inanimate object, natural phenomenon, or (and this is most often the case) animals.Watership Down

Arabian Fantasy: It is an old and traditional sub-genre that has seen a resurgence in the modern era. It is a sub-genre steeped in history and if not always mythic, then at least fable-like—which makes it an incredibly rich sub-genre. There are often stories within stories. Jinns, ghouls, sorcerers, real people and geography mixed with the legendary and fictional.Throne of the Crescent Moon

Bangsian Fantasy: Bangsian Fantasy is a sub-genre primarily concerned with the afterlife and specifically with the exploration of the afterlife. The sub-genre gets its name from author John Kendrick Bangs. Bangs wrote stories about the afterlife and the supernatural, but with a humorous style. Bangs is not the first writer, nor the last, who wrote stories like these, but his work gave the sub-genre shape. A common feature of Bangsian Fantasy is the inclusion of dead famous people and mythological characters. These stories tend (though not always) to have a genial tone. There are three main categories that Bangsian stories fall into: ghosts stuck in the living world, living people stuck in the world of the dead, and people who have died in a Heaven (or Hell). Heroes in Hell

Christian Fantasy: It is a sub-genre that utilizes and/or explores Christian ideas and themes. The religious elements can be deliberate and overt, but they can also be sub-textual and even allegorical.The Chronicles of Narnia

Celtic Fantasy: Celtic Fantasy encompasses all fantasy stories that drawn on Celtic legends and lore. The setting of most Celtic Fantasy is a medieval or ancient world. Some common elements: pagan religions, druids, matriarchal societies, romance, tragedy, strong ties to the natural world. Celtic Fantasy has a bit of a bad rap with strong literary and historic types because of its fictionalizing of real legends, cultures, societies, and peoples. Some even describe the sub-genre as escapist.The Little Country

Dragon Fantasy: 🐉Temeraire

Fantastique: Fantastique is a French term for a literary and cinematic genre that overlaps with science fiction, horror, and fantasy. The Fantastique is defined in large part by its peculiar ambiance. There is tension both within the narrative and within the reader. It is a literature that does not offer resolution but instead unsettles the reader. At its core is the supernatural (or the unknown, or the impossible) and its intrusion upon the natural (reality, or what has been accepted as reality). The Magic Skin

Futuristic Fantasy: Futuristic Fantasy does seem a bit oxymoronic. But, as the genre has grown and evolved the future no longer belongs to just the Sci Fi writers.The Sword of Shannara

Military Fantasy: The Military Fantasy sub-genre has a descriptive name, but that does not mean all Fantasy stories with military elements are part of this sub-genre. Military Fantasy is specifically about military life and may focus on a solider or a group who is part of a military.Chronicles of the Black Company

Shenmo: Gods and demons fiction is a subgenre of fantasy fiction that revolves around the deities, immortals, and monsters of Chinese mythology. The term shenmo xiaoshuo, which was coined in the early 20th century by the writer and literary historian Lu Xun, literally means "fiction of gods and demons".The Journey to the West

Swashbuckling Fantasy: Swashbuckling Fantasy is most easily described as a fantastical adventure. With plenty of energy and witty retorts, this sub-genre is meant to entertain. There are action sequences, witty dialogue, camaraderie, the chance for glory, and some romance thrown in. On Stranger Tides

Vampire Fantasy: Vampire Fantasy is known for its strong supernatural elements and undertones of blood, sex, and death. However, as the sub-genre has developed even these characteristics have changed.The Historian

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yulaan practicing qigong to form a ball of chi, by Shiredora

Especially with Strongest Under Heaven, but it's still present in Little Miss Savage: the extensive root of wuxia/xianxia/shenmo fantasy, which shouldn't even be a revelation for a Dragon Ball work, but most Western fans have literally no clue what any of those are despite them being everything Dragon Ball is supposed to be.

0 notes

Text

maybe it's just because I'm watching immortal samsara, but I need sooo many scum villain aus set in the heavenly realm. just give me shenmo, shen qingqiu was BORN to be an idle god doing cool and silly shit up in heaven. I want shenanigans

0 notes

Photo

This is my bubbly detective daughter, Chun Hua, from my interactive graphic novel, Angel By Day. I tried using brown calligraphy ink as an underpainting with watercolor on top. It smeared a bit, but I think it turned out nicely overall.

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

There’s no explanation to how SWK got kids in JTTS?

Nope, never a wife or any kind of partner to be mentioned. Like I said JTTS only really has a Sun Wukong cameo rather than being about his life. You can read it yourself if you wanna see it. Pretty much it just has Wukong in the first chapter to win a contest, and then, in the last chapter to take our main character down with the help of his daughter. But yes, the children are introduced as always being there and doesn’t explain their backstory, taking it as the reader is supposed to just move on with that information. It’s less trying to make a point and more of just cameo appearance.

#anon ask#anonymous#anon#jttw#journey to the west#xiyouji#sun wukong#journey to the south#jtts#jidu#luohou#yuebei xing#Ketu#Rahu#ask

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

did i tell you guys im working on a new thing. it started as wixia cyberpunk but now its ballooned to eventually hit xianxia and shenmo and maybe steampunk im mostly lookint at nezha reborn and maybe final fantasy. i wrote whole new chuubos style arcs for it. i suffer a curse and today its name is scope creep

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

El rey Zhou y su concubina Daji, Fotos escénicas de la Ópera de Pekín La investidura de los dioses, 1931, Tientsin. La ópera se basa en una novela china del siglo XVI y una de las principales obras chinas vernáculas del género de dioses y demonios (shenmo).

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

↑ 唷!俾妖怪捉咗?使乜驚啊?

我好劣徒始終會嚟救我嘅!

Yo! Captured by demons? What's there to be afraid of? My dear disciple will ultimately come and rescue me!

↑ 嗰個師父…次次都係噉!

以為我老孫每次都會咁得閒去救佢!

好!睇我今次點畀你一啲顏色睇!

That Master! Always taking it for granted that I have nothing better to do than to rescue him all the time! All right! I'll show you this time!

↑ 唷!師父?使乜管啊?

同紅孩兒去開P比較爽!

Yo! Master? Who cares? More fun to go out partying with Red Boy!

《西遊記》 無線電視台 (1996)

#Found these pics as I was having a nostalgic moment#And started digging round for more#TVB#JTTW 1996#Stuff and such and the narrative just popped into my head#Take it as an opportunity for more#Canto Practise#I'm too lazy to write the Jyutping down this time#But I doubt anyone really cares and this post is mostly for my own amusement anyway#HK Drama#Kong Wah#Dicky Cheung#Maple Hui#Journey to the West#Shenmo#Cantonese#Chinese Language#Language

272 notes

·

View notes