#stem tetrapod

Photo

A convergent pokemon with relicanth - this fella’s a sort of stem-tetrapod.

#fakemon#pokemon#convergent evolution#ground type#rock type#stem tetrapod#tetrapod#ichthyostega#amphibian#lobe finned fish#temnospondyl#relicanth

401 notes

·

View notes

Text

Megalocephalus pachycephalus

Megalocephalus was a genus of early tetrapod from the Late Carboniferous. Its type species is M. pachycephalus. Its second species is M. lineolatus. The known specimens of M. pachycephalus were found in multiple sites in England, Ireland, and Scotland; while M. lineolatus was found in a quarry in Ohio, U.S. Both species were discovered in the late 1800s and had much material referred to and from other genera quite frequently for several decades.

The genus name Megalocephalus means "big head," while pachycephalus means "thick head."

There was a third species named M. brevicornis in 1947 based on some original fossils referred to as "Pteroplax" brevicornis, however, the original holotype was poorly described and destroyed in a museum fire in 1909.

Megalocephalus is considered a member of Baphetidae, a small family of early tetrapod amphibians. It is not entirely clear how closely related the members of this family are due to some striking differences between them, but M. pachycephalus is closely related to sister taxon Kyrinion, more so than it is to M. lineolatus. Both species were large, estimated to reach upwards of 1.5m from head to tail. Like other baphetids, the skull had an elongation of the eye socket, which is thought to have been either a location for a salt gland or extra jaw muscle attachments. Its long, sharp teeth indicate it hunted fish.

Original paper: M. pachycephalus original description; M. lineolatus original description (referred to as Leptophractus)

Wikipedia article: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Megalocephalus

#tetrapods#stem tetrapod#paleoart#paleontology#artwork#original art#human artist#megalocephalus#baphetidae#tetrapoda#obscure fossil tetrapods

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Despite being named after the famous Muppet frog, Kermitops gratus here wasn't actually a frog itself. Instead it was a close relative of the common ancestor of all modern amphibians, part of a grouping of amphibian-like animals known as amphibamiform temnospondyls.

Living in what is now Texas, USA, during the mid-Permian, about 275 million years ago, Kermitops would have resembled a chunky salamander. Only its fossil skull is known, so its full body size is uncertain, but based on the proportions of related amphibamiformes it was probably around 15-20cm long (~6-8").

Although its discovery helps to fill in the very sparse fossil record of the early evolution of modern amphibians, it's also complicated matters more than expected. Previously it was thought that the characteristic skull anatomy of modern amphibians evolved in a clear sequence, but Kermitops has a unique mix of features that doesn't fit this idea – suggesting that there was a lot of convergent evolution going on in amphibamiformes at the time.

———

NixIllustration.com | Tumblr | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#kermitops#amphibamiformes#dissorophoidea#temnospondyl#amphibian#stem-lissamphibian#tetrapod#art#it's not easy bein' green#somebody name an entelodont after miss piggy next please

362 notes

·

View notes

Text

thats why theyre bestest friends

#rayman#clarification: globox actually becomes a stem tetrapod#like a tiktaalik or acanthostega of some sort i mean look at his triangle face

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

March’s Fossil of the Month - Acanthostega (Acanthostega gunnari)

Family: Acanthostega Family (Acanthostegidae)

Time Period: 365 Million Years Ago (Late Devonian)

In life, Acanthostega gunnari would have likely resembled a cross between a lungfish and a salamander, and this isn’t dramatically different to what it really was; Acanthostega was a stem-tetrapod, an early member of the lineage of animals that now contains all reptiles, birds, mammals and amphibians, and is believed to be an example of a key stage in the transition between fleshy-finned fishes and the earliest terrestrial vertebrates. Although it possessed 4 short limbs ending in wide, 8-toed feet, the lack of any clear wrist or ankle joints suggests that Acanthostega likely couldn’t support its weight on land, and this combined with its well-developed pelvic bones implies that it was likely a fully-aquatic animal that primarily relied on a paddle-like fin on its tail to propel it forwards while its limbs were used to steer or possibly to grasp aquatic vegetation. During the late Devonian much of the world (including the area of what is now Greenland where Acanthostega fossils were first discovered) was covered in humid, swampy deciduous forests, and this combined with Acanthostega’s anatomy suggests that it likely inhabited warm, oxygen-poor forest pools, which would also explain one of its more unusual characteristics; in addition to possessing fish-like internal gills (as suggested by the presence of gill arch like structures at the base of its skull), a rudimentary rib cage implies that Acanthostega likely had lungs, allowing it to extract oxygen from water as well as air and thereby survive in shallow, oxygen-starved pools that fishes and larger stem-tetrapods would have struggled to breathe in. The teeth of Acanthostega (which were arranged in two rows and were short and sharp, with two larger fangs on the lower jaw) implies that it was likely carnivorous (possibly feeding on terrestrial arthropods caught from above-water beds of vegetation or the banks of its home pools), and comparisons of the anatomy and mineral makeup of fossils of smaller individuals (believed to be juveniles) with those of larger individuals (which are generally believed to be adults) implies that it grew slowly, possibly taking up to 6 years to reach full maturity (at which point most individuals were around 60cm/23.6 inches long, although the difference in the length of seemingly mature individuals suggests that, as with many fish, adverse environmental conditions could considerably limit Acanthostega’s growth.) Although it is unlikely that Acanthostega or its descendants ever succeeded in colonizing land, it is generally accepted that (having become so well-suited to life in the oxygen-poor pools they inhabited) they had little need to, and as several of Acanthostega’s fellow stem-tetrapods (such as the significantly larger Ichthyostega, which had jointed, six-toed limbs and a more developed rib-cage that likely allowed it to haul itself onto land for prolonged periods like modern mudskippers or seals) are known to have done so, the study of the anatomy and lifestyle of this strange little swamp-dweller can still help to shed light on how the variety of land-dwelling vertebrates seen today came to be.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

Image Sources

Fossil: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Acanthostega_gunnari.jpg#/media/File:Acanthostega_gunnari.jpg

Restoration: https://www.10tons.dk/acanthostega-gunnari

#Acanthostega#acanthostega gunnari#animal#animals#prehistoric animals#wildlife#prehistoric wildlife#devonian wildlife#zoology#biology#paleontology#stem-tetrapod#stem-tetrapods#evolution

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

yknow i never thought i’d have to stop and consider if an animal actually has a tongue before but here we are

0 notes

Text

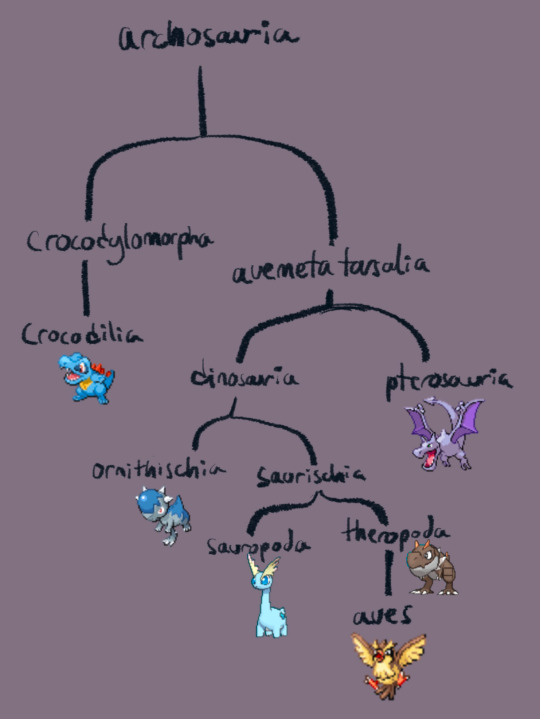

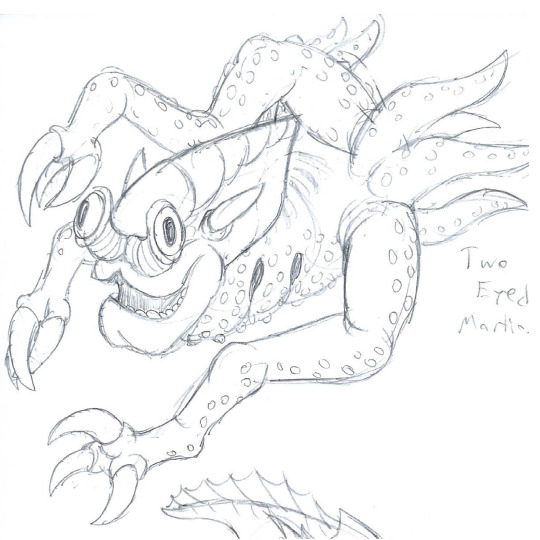

had this lying around for a while, a quick sketch of "shock-jaw", a stem-tetrapod kaiju

#ollyneanderthal art#creature design#monster design#kaiju art#kaiju#kaiju oc#dino art#prehistoric animals#lobe finned fish#tetrapods

82 notes

·

View notes

Note

is there a known point at which humans and pokemon diverged?

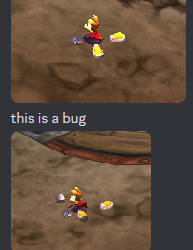

yes! i've been meaning to talk about something similar to this, so we'll be needing to expand the scope of this ask by, like, a lot. so, first we do kind of need to answer what a pokemon actually is, what it means when we say an organism is a pokemon. and to do that: i'm going to tell you about dinosaurs and trees. stick with me, here, i'm having fun. here's a little phylogeny lesson.

we'll be using dinosaurs as our example to talk about evolutionary relationships: dinosauria is a clade, also called a monophyletic group. that means that it is defined as one common ancestor and all its descendants. genera, families, and so on are usually clades (there are some exceptions, usually resulting from outdated definitions already being important and widely accepted before new data mixes up how we thought the family tree looked. for example, fish isn't a monophyletic group, because they exclude the tetrapods. if fish were a clade, we'd all be fish. as we should be).

here's a very, very simplified family tree of the archosaurs, the group that includes crocodiles, dinosaurs, and pterosaurs. think of this whole thing as a tree branch that splits and diverges as new species and groups arise.

a monophyletic group, or clade, is like if you snip a branch from the tree and include the entire branch. so, if you snip this tree at the dinosauria branch, it'll have the ornithischia and saurischia (including sauropoda, theropoda, and aves) twigs on it, so all ornithischians and saurischians are dinosaurs. (in case you didn't know, birds are dinosaurs, and that's why!) basically, if it evolved from a dinosaur, it will also be a dinosaur.

(the next two terms are not actually relevant to our discussion, but if i'm defining monophyly, i need to tell you about the other two -phyly's, so bear with me. now, a lot of times when people say "dinosaurs", they don't mean to include birds- this is called a paraphyletic group. this means it excludes a part of the branch- so, if you snipped the tree at dinosauria, and then discarded the aves twig, you would have a paraphyletic group including ornithischia, sauropoda, and theropoda minus the aves.

the third common type of grouping is polyphyletic, which is when multiple branches of a tree are grouped together. so, if you snipped the tree at, say, crocodilia, pterosauria, and sauropoda and made those separate branches a group without anything else, that would be a polyphyletic grouping.)

.

now, let's look at trees. the word 'tree' doesn't describe an evolutionary grouping like the previous words do, 'tree' is just a descriptor that refers to how something looks, or what physical features it has- trees have woody stems, are perennial, and have branches with leaves, for example. there are species from all around the plant kingdom that are trees, that are entirely unrelated from one another! for example, an oak tree is much more closely related to a rose bush than it is to a pine tree. so "tree" is a morphological descriptor, not an evolutionary one.

now, what are pokemon? let's look at some of the traits every single pokemon shares. all pokemon have one or two out of the 18 types. they can all learn moves and have abilities, and can be caught in pokeballs. there is no one monophyletic group that includes all pokemon and excludes all non-pokemon. hell, there are things outside of the kingdom of life that are pokemon, look at trubbish. that's just a bag of trash that came to life. that's not related to literally anything. god i love trubbish

that is to say, pokemon is a morphological descriptor, just like trees, and not like dinosaurs. it is a group of things with particular characteristics with no regard to how they're related evolutionarily.

so, now we loop back to your original question: when did humans diverge from pokemon? in fact, humans evolved from organisms that were pokemon. almost every vertebrate is a pokemon, with the majority of the exceptions being tiny, so humans not being pokemon is pretty weird given we are Big Vertebrates, we're as far as we know the Only Big Vertebrate that isn't a pokemon.

our lineage lost its.. pokemon-ness right around half a million years ago. apologies if i get some specifics wrong here, human evolution isn't my forte- but the first non-pokemon human was Homo heidelbergensis. H. heidelbergensis gave rise to Homo neanderthalensis (commonly known as neanderthals) and Homo sapiens- that's us! every other member of the genus Homo, and the great apes more broadly, are pokemon. of the non-pokemon Homo lineage, Homo sapiens (us) is the only remaining species (though many people do have a fair bit of neanderthal heritage in there).

well, why did our little human lineage stop being pokemon? it's generally a pretty big advantage to be able to breathe fire, or shoot ice lasers, or use telekinesis or whatever, so there's a strong selective pressure against losing pokemon-ness, despite its high energy cost. well, as far as i know, the best theory we have for that has to do with our relationship with pokemon, and the fact that we're so good at becoming friends with them. seriously! ancient humans befriended and worked with the pokemon around them, so much so that they essentially lost the need to be pokemon themselves.

because most pokemon require much more energy than the average non-pokemon to function, due to the aforementioned fire breathing and ice lasers and such, if there's no strong selective pressure for a species to keep being a pokemon, that trait will generally be selected against. summed up: the reason you and i aren't pokemon is because we're friends with pokemon. :)

oh, and- our closest non-pokemon relatives are basically everything else in the genus Homo. that's the ralts line, sawk, throh, and yes, of course: mr. mime. so next time you're out training, be sure to say hi to your closest pokemon cousins.

whew! that was a longwinded answer for something that technically could've been, like, a paragraph, but thank you for reading my tangents if you did.

330 notes

·

View notes

Text

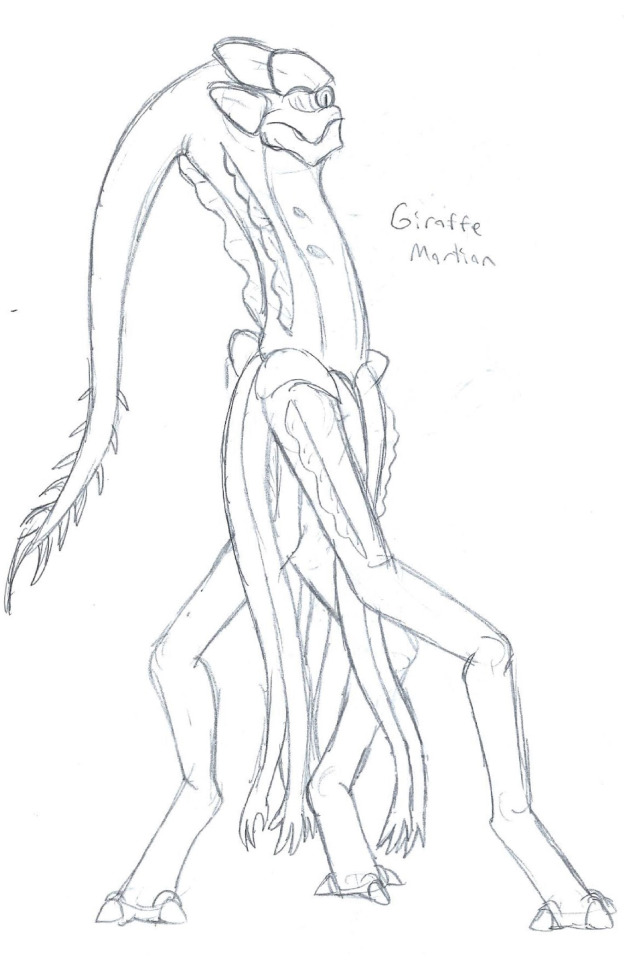

A Hundred Some New ATOM Kaiju Pt. 7

On this installment of the unfinished ATOM kaiju showcase, we've got still more aliens for you.

Rosunwell has a bit of a story to it. See, the Beyonder Alliance - i.e. the big coalition of alien invaders on ATOM's setting - creates synthetic organisms tailor-made to new planets they wish to interact with, since most of its citizens don't want to modify their bio-chemistry to adapt to the wildly different environments of other planets, and it's easier to just custom build those foot-on-the-ground explorers anyway. These custom explorers are made from a gray biological sludge of stem cells that's easily molded to resemble native life - hence humans more often than not seeing gray, humanoid aliens when being abducted. Well, during the Beyonder Invasion, one ship was ruptured and leaked out its collection of inert gray sludge, and said sludge got caught between an explosion and a Yamaneon fault line, and thus suddenly became a kaiju.

The sludge slowly figures out what shape it'd like to be, beginning as an amorphous, shifting pile of goo sculpting various alien anatomical features, before finally coalescing into a final form. Rosunwell would be the 100th ATOM Bonus Kaiju File, which would make it the 150th file overall (not including the contest entries), so to be cheeky I made it loosely resemble Mewtwo, the 150th pokemon.

Four more fun Beyonder monsters: a killer clown from outer space, a monster based on a toy batmobile I saw that looked kinda loke a monster head, a spider-like alien that takes more than a bit after Venom and Spider-Man (pretty proud of the name "Galachnid"), and a three-eyed goober.

In the past I designed more Venusian monsters than Karamtor, and while most of them remain abandoned, I guess I had a soft spot for Vrank, the living tank monster, so I gave it another go.

To finish this batch, we have four martian monsters that would feature in a story about the prehistoric war between the Martians and the Beyonder Alliance - four comrades of Kemlasulla and pals. They're all exercises in taking Kemlasulla's body plan in strange directions, just as Earth has spun the tetrapod body plan into a multitude of very different beasts. I think they may still be too similar to Kemlasulla to really reach the diversity I wanted, but then maybe I only think that because I'm looking at them with earthling tetrapod eyes.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Easter everyone! While you may never see a bunny laying colorful eggs, it may come as a surprise that once upon a time, egg-laying mammals were the norm. In fact, it wasn't until as recently as about 140 Mya that mammals started giving live birth. In fact some mammals, like the echidna and platypus, still lay eggs today.

Morganucodon (Glamorgan Tooth), was a very small, early mammaliform that lived from the late Triassic to the middle Jurassic (~205-163 Mya). This primitive mammal's skull was only about 2-3 cm in length, and it had the appearance of a mouse or shrew. It is thought to have been a burrower, and its eggs were probably small and leathery, much like the eggs of modern monotremes.

The amniotic egg was an important milestone in the evolution of life. While amphibians still lay their jelly like spawn in the water, later tetrapods would adapt a more advanced egg with a protective shell. This would allow these animals to live further inland, without needing to rely on the water so much. We think these amniotes diverged during the Carboniferous about 312 Mya, but since eggs typically don't fossilize well, our earliest fossil evidence of eggs don't appear until about 195 Mya, a group of fossilized eggs laid by stem Sauropod dinosaurs in the early Jurassic.

The amniotes would split into two major groups, the Synapsids and Sauropsids. The ancestors of today's mammals and reptiles respectively.

#happy easter#paleoart#paleontology#evolution#mammals#morganucodon#eggs#easter#easter egg#zoology#amniote

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

Swan I promise I'll get caught up on your fanwork soon. Soon as I actually watch these overdue DVDs of The Watchman😉. In the meantime consider this an invitation to do a director's commentary from back when Will Graham was a bird?

please enjoy your viewing of the watchman! don't quote me on this, but i hear he (the eponymous watchman) was in a comic book once...really make u thimk.

oh god okay umm...how do i put this politely for the good people in the audience who have not been following me since 2013. so. ok. so i've long maintained that turning a character into a bird monster is one of the truest forms of love i am capable of expressing. "but swan!" you say, shocked and horrified, "surely you mean turning a character into a WEREWOLF is one of the truest forms of love you are capable of expressing! you have a whole thing about werewolves! it's an expanded universe with hinted crossovers! there's internal logic and now a magic system! you have spilled literally thousands of words that are No Plot Just Describing Midcycle Werewolves and you KEEP THREATENING TO DO THAT MORE." and like. you're not wrong strictly speaking. and i do inflict that aggressively upon my favorite characters. but there is something particularly monstery about the bird monster that a werewolf just doesn't get at.

it's the uncanny valley of it all, you dig? a werewolf is, when you get down to it, a wolf whose instincts are fettered to a human perception of the world—hence, functionally, a dog. a very large, gross, dangerous, infectious dog, in some cases—a dog with hands and fucked-up people teeth, frequently—but it's fundamentally the emotional tension of the dog that i'm working with here, right? the sit and stay and will i get a pat or a kick of things, the what is a pack and what are they owed of it, the animal caught in a little box with the human and the realization of how little space there is between those two things. which is all lovely delicious good food for me, personally, and of course i am capable of making something tangibly offputting out of those compelling pieces.

but the bird monster is a different game. that's a different part of the uncanny valley, and i hesitate to call it a more physical part, but the physicality IS part of it. a bird has warm blood, like you or like me (with apologies to any reptiles, amphibians, ectothermic fish, etc. reading this). it breathes air. it's often social and intelligent. it has a voice—more importantly, it makes music. we connect with these qualities, as fellow warm-blooded social tetrapods. we think, oh, this is a familiar creature, this is a creature i can easily empathize with (again, apologies to those reading this who, like me, are thrown into a tearful cute-aggression frenzy over the japanese giant salamander).

but a bird feels different from a human in a way that a dog doesn't. it's got feathers. it's got hollow bones. it's got an expressionless face and eyes that don't convey the same warmth as a dog's or a wolf's or even a cat's. there are tame birds and domesticated birds, yes, but in general there's not the same cultural sense of the bird as companion animal that smooths the way (or burdens) the dog or the wolf-as-dog.

and it flies. that's fuckin' different.

so it's a different tension there. where the werewolf's sense of alienation stems from the uneasy knowledge that there's gray area between wolf and dog and human, the bird monster's deal is a more classic disjoint. a human is not like a bird. these two things are (or feel) more diametrically opposed. and yet in the bird monster they exist within a single body anyway. the human in you is content to travel in two dimensions. the bird in you understands that there's a whole lot more world if you just look up. the human in you needs the solidity of earth underfoot and the comforting anchor of gravity. the bird in you knows those things for chains and cages in disguise. the human in you tastes blood and grimaces, gags, spits and screams and weeps. the bird in you swallows, expressionless, and sings.

ok so then imagine if it was will graham,,,

#chatter#ask games#PRETENTIOUS PRETENTIOUS PRETENTIOUS PRETENTIOUS.#tldr: bird monsters is different body horror and i like it.#''ok what was the like. plot. of the bird!will thing'' there wasn't a PLOT you think i do PLOTS#HE TURNED INTO A BIRD AND THEN MADE OUT WITH BEVERLY KATZ A LOT BECAUSE I'M A WOMAN OF DISCERNING TASTES.#BY MOST PEOPLE'S ACCOUNTS I WAS DOING HANNERBAL FANDOM VERY WRONGLY.#it's been a very long time since i thought about this au. first instance of me trying to bring heians into a fandom hilariously#in a vain but good-faith attempt to rehabilitate the characters of chiyoh and lady murasaki. by turning them into bird monsters.#my repertoire is limited but i get MILEAGE out of it baby.#i don't even know what to tag this.#beautiful monsters#i guess?

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Picture by Timothy Morris

The cnidarian trees of the earth of the Quotidians, from Fellow Tetrapod.

Pictured is what appears to be a branch of a maple tree, but on close inspection, the leaves look a bit puply and tentacular. They are in fact polyps, encased in a tough cuticle, able to withdraw into the glassy hollow stem. This is what the Zogreion has instead of trees

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ossinodus pueri

Ossinodus was a genus of stem tetrapod from the Early Carboniferous. Its type species is O. pueri. The known specimens were found in the Druckabrook Formation in Queensland, Australia. Its fossils include the oldest known pathological bone in a tetrapod, which is a healed fracture on a right radius.

Its formal diagnosis does not include any autapomorphies, but the authors found the combination of its features to be enough to warrant the creation of a new genus and species. While most of its traits are shared with other members of Whatcheeriidae, it does have a broader and shallower skull than Whatcheeria and was generally larger than both Whatcheeria and Pederpes, which is its most distinguishing quality.

Its placement amongst other stem tetrapods is debated, but it has been supported that it is closely related, if not included within, Whatcheeriidae. The possible absence of an intertemporal bone, a small bone on the skull above the eye, would place it more basally to Whatcheeriidae as a sister taxon to the family. There are five known specimens of O. pueri, all found at the same time from the same formation, that vary in size and are thought to represent both juvenile and adult creatures. Its most famous fossil, the radius with a healed fracture, indicates it is the oldest known large tetrapod to have spent substantial time on land, as it was found that the pressure exerted on the bone to fracture it could have only come from falling off of a height of about three feet. Its healing also appears to have continually remodeled the bone in response to supporting weight, something that would not have occurred if it spent all its time in the water.

Original paper: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.0031-0239.2004.00353.x

Wikipedia article: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ossinodus

#tetrapods#stem tetrapod#paleoart#paleontology#artwork#original art#original artwork#human artist#ossinodus#whatcheeriidae#tetrapoda#obscure fossil animals#obscure fossil tetrapods

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Crassigyrinus scoticus was an early tetrapod from the early Carboniferous Period, known from ancient coal swamps of Scotland, Nova Scotia, and West Virginia between about 350 and 330 million years ago.

Around 2m long (6'6"), it had an elongated streamlined body with tiny vestigial-looking forelimbs, and a pelvis that wasn't well-connected to its spine – features that suggest it had re-evolved a fully aquatic lifestyle at a time when its other early tetrapod relatives were specializing more and more for life on land.

Fossils of its skull are all rather crushed, and traditionally its head shape has been reconstructed as unusually tall and narrow. But a more recent study using CT scanning has instead come up with a wider flatter shape more in line with other early tetrapods.

Its mouth also had a very wide gape and a strong bite, and it may have occupied an ecological role similar to that of modern crocodilians, lurking in wait to ambush passing prey.

———

NixIllustration.com | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#crassigyrinus#stem-tetrapod#tetrapod#art#good job you funky little tetrapod

455 notes

·

View notes

Text

Life in the Carboniferous

(first row: Diplocaulus, Lepidodendron, Arthropleura; second row: Meganeura, Hylonomus, Walchia, Pulmonoscorpius; third row: Tullimonstrum, Calamites, Edestus; fourth row: Pederpes, Eryops, Stethacanthus)

Art by:

Pederpes - Ntvtiko

Lepidodendron - Richard Bizley

Calamites - Jonathan Hughes

Walchia - Dinoraul

Arthropleura - Vladislav Egorov

Meganeura - Walking with Monsters

Pulmonoscorpius - Plioart

Hylonomus - John Sibbeck

Diplocaulus - Sergey Krasovskiy

Eryops - mmuyano

Tullimonstrum - Nobu Tamura

Edestus - Julio Lacerda

Stethacanthus - Ja Chirinos

It‘s the age of giant bugs!

But before I get to talk about giant bugs, we have to take a moment and appreciate the real stars of the Carboniferous: The plants! The whole reason it is called Carboniferous (“coal-bearing“) is because of them. The forests of the time got flooded repeatedly, decayed, rotted and over the ages have turned into coal deposits that we use today. So whenever you hear people talk about fossil fuels coming from dinosaurs you can “well-actually“ them and talk about ancient plants instead.

During the Carboniferous earth was a warm, humid place with lots of tropical swamp forests. Some of the plants you would have seen there are roughly familiar to us today, like ferns. Similar looking were the seed ferns, which are extinct today. They reproduced by making seeds (shocking, I know), unlike “regular“ ferns, that reproduce via spores.

In some cases the plant groups are still around today, but they look nothing like their Carboniferous counterparts. Calamites for example was a horsetail that grew into more than 30 m high tree-like structures. Closely related to the small modern clubmosses were the Lepidodendrales (“scale trees“, named after their bark, which looked like scaly reptile skin). Lepidodendron could grow up to 50 m tall and would have spend most of its life as a single unbranched stem, which definitely added to the weird alien feel of Carboniferous forests. A more familiar sight were the earliest conifers, like Walchia, which lived during the late Carboniferous. Many other modern plants including grasses, flowers or hardwood trees, like maples or oaks, weren‘t around yet and wouldn‘t be for many millions of years.

Now that we have established that the forests of the time were strange and alien filled with plants of all kinds of weird shapes and unusual sizes, let‘s look at the bugs, which were also having all the wrong sizes:

Among many others there was the dragonfly cousin Meganeura with a wingspan of more than 70 cm, Pulmonoscorpius, an about 70 cm long scorpion and Arthropleura, a truly gigantic millipede, more than 2 m long. It was comparable in size to the biggest sea scorpions and one of the biggest arthropods that ever lived.

The questions is of course, why were insects and other arthropods this big? The main answer is oxygen. Insects have a very different breathing system than we do and it doesn‘t scale well with size. Because of that they have a size limit. At some point, they just can‘t get enough oxygen into their bodies (thankfully, because I don‘t need giant spiders or mosquitos or whatever). During the Carboniferous however, there was a lot more oxygen in the atmosphere than there is today, so the arthropods could grow much bigger than they do today.

Another reason for the giant bugs might be, that they didn‘t really have a lot of competition. There was nothing to keep them in check, so evolution just went wild with them. You have to remember that, while insects were already taking to the skies, the proudest accomplishment of our tetrapod ancestors was crawling from one puddle to another. To say that arthropods had a head start would be an understatement. So for future references, remember that every time I mention a cool thing any vertebrate does, there probably was an insect that did the same thing millions of years earlier.

But speaking of the tetrapods: They were getting better at crawling between puddles. We get the first true amphibians like boomerang-headed Diplocaulus and the giant Eryops, one of the biggest land animals of the time (you know, roughly milliped-sized). Maybe even more exciting was that during this time we see the first amniots! That‘s right, there are animals that lay eggs now. Real, actual eggs, that can survive without water. These lizard-like creatures (they aren‘t actual lizards, those will take a lot longer to evolve) can finally leave the puddles and rivers their amphibian cousins have been bound to.

It‘s probably a good thing, that they can leave the water behind, because there was some very weird shit going on in the oceans. After the placoderms went extinct during the late Devonian mass extinction (rip), a lot of bizarre shark relatives showed up, like Stethacanthus with its anvil shaped dorsal fin or the absolute horror that is Edestus.

But the weirdest thing of the Carboniferous (maybe one of the weirdest things ever) has to be the Tully monster (btw, not really a monster, only about 35 cm long). I mean, just look at it. It has a mouth that is separated from the rest of its body by a proboscis. It has stalked eyes. It is weird as fuck. We also have absolutely no idea what it is. Science agrees that it is an animal, and that‘s about it. There are arguments for it being a vertebrate, an arthropod, a mollusc, a worm and pretty much anything else you could think of. Honestly I just love it because of how strange and fake it looks.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

I knew jumping into Armored Core after binging Dark souls 2 for a week would be a jolt & i'd have to adjust right away; it was and i did (especially because this is my first time with *any* mech media)

What i wasn't prepared for was how quickly the game rewired my brain to the stem. i streamed just the first couple hours, now i'm replaying missions for the S Ranks and planning 3 separate mech builds & paintjobs based on my favorite Modular Synth Modules

Ideas & images under the cut

Saïch: 4 detunable saw waves. I'm thinking a tetrapod with all laser/plasma weapons

Rampage: Envelope/Function Generator. i want to give it huge tank treads and all the lob-able weapons/vertical missile launchers to go with the Rise/Fall inputs

Plaits: oscillator multi-tool with tons of pre-programmed settings. it does so much it's hard to translate it to a mech build. probably a lightweight frame with a mix of kinetic & energy weapons, maybe the only one with a shield

5 notes

·

View notes