#that´s already soseki

Text

Happy Soseki Sunday!

#I wanted to edit this more but look at the dog´s face#that´s already soseki#soseki natsume#the great ace attorney#tgaa#dai gyakuten saiban#dgs#natsume soseki#soseki sunday#dgssoseki appreciation#minas art

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

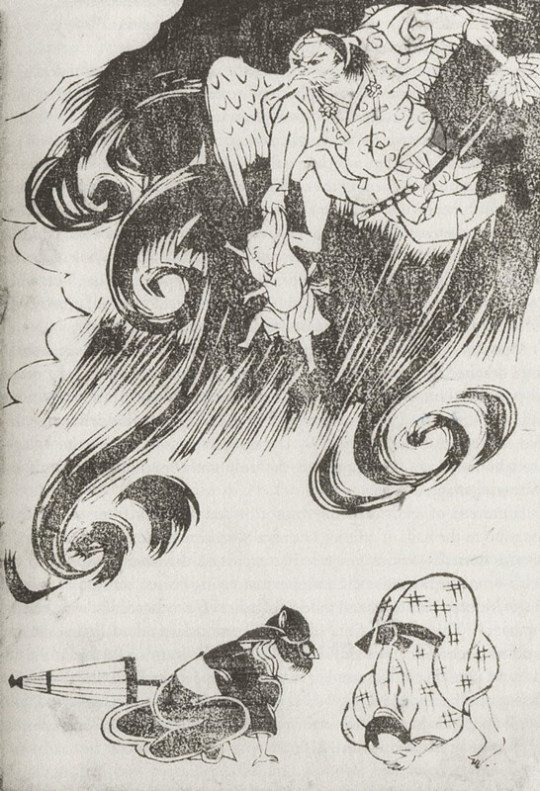

"Tenma, boss of the tengu". Exploring the "heavenly demon(s)"

The identity of Tenma, the leader of tengu in Touhou, remains a mystery. I think only ZUN can solve it - if he ever chooses to, obviously. Therefore, this is not quite an article meant to prove I figured out who Tenma is. Instead, it presents the origin of this name, and introduces a handful of figures in various contexts portrayed as leaders of the tengu who I think would be interesting candidates for the position of Tenma.

My additional goal is to show that even though popculture tends to portray all tengu as basically interchangeable, there is actually a fair share of unique tales about specific named members of this category. Corrupt monks! Vengeful spirits! Visitors from far off lands! There’s even a sea monster converted to Buddhism! Obviously, this isn’t supposed to be a list of every single named tengu and every single story. It’s not even a list of all of my favorite tengu. It’s simply an attempt at convincing you that digging deeper into tengu background is worth it - and in particular that there is still a lot to speculate about when it comes to their leader in Touhou. It’s some of the best oc free real estate in the series, really.

Due to technical difficulties, the bibliography is included as a Google Docs link rather than a part of the article. I'm sorry.

From Mara to tengu: the development of the concept of tenma

Silhouette of a tengu negotiating with Kanako in WaHH 38, sometimes labeled as Tenma on fan sites through debatable exegesis.

As we originally learned in Perfect Memento in Strict Sense, Gensokyo’s tengu are ruled by an individual named Tenma (天魔). Akyuu simply describes them as the “tengu’s boss” and provides no further information. While some additional tidbits have since surfaced here and there, they largely remain a mystery. Next to Chang’e, the unseen fourth deva of the mountain and the fourth Beast Realm figurehead they’re easily the highest profile unseen character in the entire series.

While in absence of information on the contrary we cannot necessarily assume that Tenma isn’t a given name in Touhou, ZUN did not actually come up with this term. It has been a significant part of tengu background at least since the Kamakura period. It can be translated as “heavenly demon”, and it’s a shortened form of Dairokuten Maō (第六天魔王), “Demon King of Sixth Heaven”, the Japanese name of Mara. Tenma is explained as a synonym of Mara’s “personal name” Hajun (波旬; Sanskrit Pāpīyas) for instance in the treatise Makashikan (摩訶止観; translation of Chinese Móhē Zhǐguān, “Great Cessation and Insight”).

Is that all there is to the mystery of Tenma? For what it’s worth, a possible reference to the full form of Mara’s name can be found in a description of Okina’s ability card in Unconnected Marketeers, which mentions “Tenma living in paradise”. I don’t think this is very strong evidence, though.

Touhou aside, it is hard to deny tengu are fundamentally tied to Mara. They are directly described as his subjects in Buddhist works such as Soseki Musō’s (1275–1351) Muchū mondō (夢中問答集; “Questions and Answers in Dreams”) and Unshō’s (運敞; 1614–1693) Jakushōdō Kokkyōshū (寂照堂谷響集). However, it needs to be stressed that a being referred to as Tenma does not necessarily have to be Mara himself.

A plurality of Maras theoretically became possible as soon as the belief this name didn’t designate an individual, but rather a position which could be held by various individuals or a category of beings developed in Buddhism. The former idea already appears in the Māratajjanīya, a part of the Theravada Buddhist Majjhima Nikāya, dated to the late first millennium BCE or early first millennium CE. Maudgalyāyana, one of the disciples of the historical Buddha, reveals in it that he was (a) Mara in a past life, and thus can easily notice the presence of the present Mara. The shift from a singular Mara (魔, mo) to an assortment of “demon kings” (魔王, mowang) is also well documented in early Buddhist sources from China.

As a curiosity it’s worth noting that even though the terms mo and mowang originally referred to strictly Buddhist demons, they were also incorporated into Daoist traditions, especially Lingbao and Shangqing. For example the former school's central text Duren Jing (度人經; “Scripture for Universal Salvation”) maintains that multiple mowang exist.

While some of these “demon kings” are tempters not too dissimilar from their Buddhist forerunner (though what they obstruct is attaining the distinctly Daoist form of transcendence - in other words, immortality), others are portrayed as judges responsible for determining the fates of people in the afterlife. In later sources the term mo sometimes also refers to supernatural pathogens (generally 邪, xie or 邪氣, xiequi).

Sun Wukong and his fellow pilgrims battling the Bull Demon King on a mural from the Summer Palace in Beijing (wikimedia commons)

You don’t really need to look for any particularly obscure sources to see this transformation of Mara into a generic moniker, though - even the Bull Demon King from Journey to the West has the compound 魔王 in his name. Same goes for numerous other antagonists from this work.

When it comes to Japanese sources, it also doesn’t require looking for anything particularly obscure to find evidence in the belief in multiplicity of ma or tenma.

In the historical epic Heike Monogatari, emperor Go-Shirakawa implores Sumiyoshi Daimyōjin to explain the nature of tenma to him. He reveals that this term refers to monks and scholars who, despite nominally following Buddhism, lacked the mindset needed to attain enlightenment. He compares them to birds of prey, but also states they belong to the “dog species”. All of these are nods to well established beliefs about tengu, which I discussed in my previous article, with a reference to the writing of their name on top of that.

It comes as no surprise that right after that Sumiyoshi Daimyōjin specifies that “the wise men of the eight sects who become tenma are called tengu”. He also makes it clear the tenma are quite numerous: “nine out of ten will definitely become tenma and try to destroy the Law of Buddha,” he warns.

A plurality of tenma can also be found in assorted biographies of pious Buddhist reborn in a pure land, so-called ōjōden (往生伝). The Tendai treatise Asabashō (阿娑縛抄) attributes the ability to “subdue all tenma” - evidently a class of beings, not an individual - to Fudō Myōō.

Through the rest of the article, I will introduce some of these tenma - the most famous tengu. My goal is not to convince you that any of them is a uniquely plausible candidate for the role of the unseen Touhou Tenma - I merely would like to point out there are multiple interesting options.

The oneness of vice and virtue: Ryōgen, the ruler of Makai

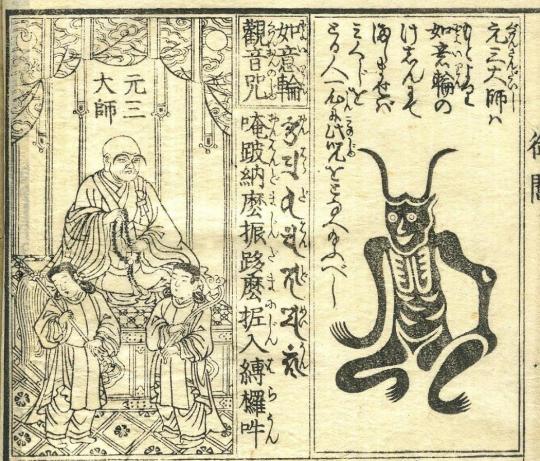

The historical Ryōgen (left) and his deomic alter ego Tsuno Daishi (wikimedia commons)

Before Ryōgen (912–985) came to be seen as a tengu, he was one of the most influential members of the Tendai school of Buddhism to ever live. He reformed the Enryaku-ji complex on Mt. Hiei, took part in numerous theological debates, and gained the favor of the imperial court by supposedly enabling the birth of an heir of emperor Murakami with his prayers. He was also renowned as a master of esoteric protective rituals.

The proponents of the Tendai establishment understood him as a fearsome protector of this tradition. As early as 50 years after his death, in the 1030s, he came to be identified as the reincarnation of Tendai’s founder Saichō. He was also considered a manifestation of one of the eight dragon kings, Uhatsura (優鉢羅; from Sanskrit Utpalaka). Ōe no Masafusa states that in this form he continued to protect Mt. Hiei, instead of being reborn in a pure land. This idea continued to spread, and by the end of the Kamakura period he came to be commonly revered as a protective figure by all strata of society. Haruko Wakabayashi notes that only Kūkai developed a similar cult in Japan as far as patriarchs of the esoteric Buddhist schools go.

It was not Ryōgen’s ability to navigate complex doctrinal debates about the interpretation of sutras that resulted in his popularity, but rather his esoteric skills. He was supposedly uniquely accomplished when it came to subduing anything which could be described as ma. In a Konjaku Monogatari tale I’ll discuss in more detail later, he effortlessly overcomes a tengu, for instance.

However, in addition to spiritual obstacles and demons, the ma he was supposed to conquer also included political opponents, rebels or brigands, as the Buddhist law and the interests of the state were understood as identical. Ryōgen’s efficiency was so great he came to be viewed as a manifestation of Fudo Myōō, one of the wisdom kings and the conqueror of ma par excellence.

Not everyone viewed Ryōgen positively, though. The earliest criticism came from his contemporaries. It was argued that he favored monks from aristocratic families, and that he lived in luxury unbefitting for a monk. Furthermore, numerous conflicts between monks erupted during his tenure as Enryakuji’s abbot, including the split between the Sanmon and Jimon lineages. Since in some cases this led to armed confrontations, later on he was blamed for essentially enabling the rise of militarized monks who commonly caused disturbances on Mt. Hiei.

The real breakthroughs were not these tangible “political” criticisms. Rather, it was the identification of Ryōgen as ma, which arose due to conflict between various schools of Buddhism in the early middle ages. Most commonly this meant portraying him as a tengu - as I explained in my previous article, the form arrogant or corrupt monks were believed to take. A variant tradition described him as an oni, though according to Bernard Faure this likely simply reflects a degree of interchangeability between them and tengu.

Ryōgen is arguably the most famous historical monk to be furnished with such a literary afterlife. An early example can be found in the Hōbutsushū from the twelfth century, which states that this was a result of his attachment to Enryaku-ji. In Jimon Kōsōki (寺門高僧記) it is instead his investment in doctrinal debates that made him unable to attain rebirth in a pure land.

A gathering of tengu leaders from Tengu Zōshi (wikimedia commons)

Since Ryōgen was no ordinary monk, his tengu self also had to be special. In the Tengu Zōshi (天狗草紙), he is described as the ruler of all tengu and the realm they inhabit, Makai (“world of ma”; also referred to as Tengudō). It's worth pointing out the notion of Makai being a place where monks turn into specific classes of supernatural beings is basically a core part of UFO’s plot, and in SoPM Miko even wonders if Byakuren shouldn’t be considered a tengu.

As a ruler of Makai, Ryōgen came to be referred to as a “demon king”, maō (魔王). An example can be found in the historical epic Taiheiki, where he is described as one of the “great demon kings” (大魔王, daimaō) who debate how to cause chaos in Japan. He is assisted by vengeful spirits of the emperors Sutoku (more on him later), Go-Toba and Go-Daigo; two members of the Minamoto clan who sided with Sutoku, Tameyoshi and Tametomo; and the monks Genbō, Shinzei (真済, 800-860; obscure today, but apparently well known as a monk turned tengu in the middle ages) and Raigō (who supposedly turned into the infamous “iron rat”).

In Hirasan Kojin Reitaku (比良山古人霊託; “The Spiritual Oracle of the Old Man of Mount Hira”) this is only a temporary fate, though: supposed by the time this work was compiled, he already managed to leave Tengudō. As I discussed last month, this reflects a fairly standard belief too: to become a tengu, one had to actually be a Buddhist, and while it made striving for enlightenment more difficult, it did not mean eternal damnation or anything of that sort. A tengu could still choose to pursue rebirth in a pure land - it was just more difficult than for a human.

The evolution of Ryōgen’s image didn’t end with the establishment of his new role as a king of tengu, or even with the arguments that he might have nonetheless subsequently attained enlightenment. By the end of the Kamakura period, he came to be worshiped explicitly in the form of a “demon king”. While initially polemical, this image of him came to be subverted by Tendai monks to their own ends. They asserted that Ryōgen did not enter the realm of ma because of his arrogance, but rather consciously chose to do so in order to protect Buddhist principles. By becoming the ruler of its inhabitants, he also became their ultimate conqueror.

The notion of a being who is simultaneously essentially Mara-like and a protector of Buddhism seems contradictory. That’s actually the intent here. Through the middle ages, the esoteric schools of Buddhism developed the notion of hongaku, or “original enlightenment”. In its light, opposites were in fact identical. Buddha was the same as Mara (魔仏一如, mabutsu ichinyo). As it was argued, to attain Buddha nature one had to understand and experience delusion as well. Thus virtuous individuals could become demon kings in order to freely control evil beings.

In addition to its deep philosophical implications, the hongaku theory was also used to reject criticisms of the Buddhist establishment. Enjoying luxuries was but a way to better understand delusion, and thus to advance along the path to enlightenment. Its proponents embraced some criticisms of Ryōgen: he did favor nobles, accumulate wealth and live arrogantly. He did become a powerful tengu. But all of this was in fact part of a noble goal. And on top of that, as a demon king he was an even more fearsome protector of Tendai than he would be otherwise.

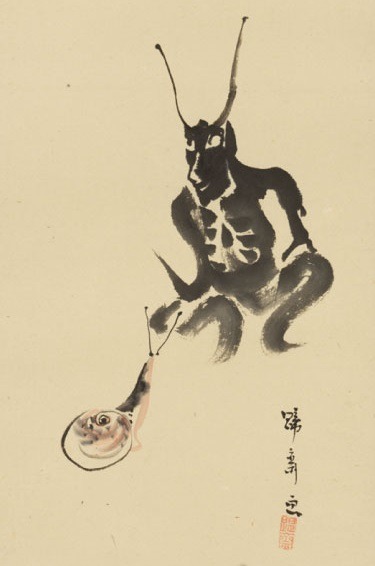

"Tsuno Daishi and a snail" by Teisai Hokuba (Sumida Hokusai Museum; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

The new role of Ryōgen warranted new iconography. While formerly portrayed simply as a monk holding the expected priestly attributes, in the Kamakura period he came to be depicted as Tsuno Daishi (角大師), the “Horned Master”. This image spread far and wide due to the development of a belief that hanging depictions of Ryōgen would guarantee the same protection Tendai institutions received from him. He came to be seen as particularly efficient in warding off disease.

Many temples still distribute talismans depicting Tsuno Daishi today. This custom received a lot of press coverage in the early months of the COVID pandemic, and you might have seen some examples on social media.

From vengeful spirit to tengu: the case of emperor Sutoku

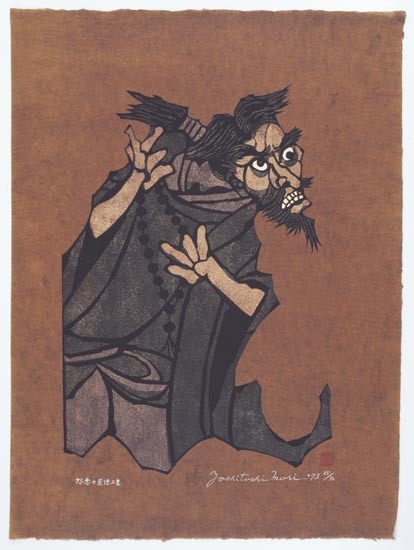

Sutoku, as depicted by Yoshitoshi Mori (Tokyo's National Museum of Modern Art; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Sutoku has much in common with Ryōgen - he was also a historical figure who purportedly became a tengu. However, he was not a monk, but rather an emperor. He reigned from 1123 to 1142, when he was forced to abdicate in favor of his half brother Konoe.

Konoe passed away in 1155, but Sutoku was not allowed to return to the throne. It was instead claimed by another half brother, Go-Shirakawa. Sutoku decided that’s enough half brothers seizing a position he believed was still rightfully his, and plotted an uprising. This culminated in the Hōgen Disturbance of 1156. Alas, planning seemingly wasn’t his strong suit, since the conflict was essentially resolved before it even started. Go-Shirakawa’s forces defeated Sutoku’s before they even left their encampment.

Sutoku as a vengeful spirit, as depicted by Kuniyoshi Utagawa (wikimedia commons)

In the aftermath of his failed rebellion, Sutoku was exiled to Sanuki, where he eventually passed away in 1164. However, his memory lingered on. He most likely came to be widely perceived as a vengeful spirit after the great fire of Angen broke out in Kyoto in 1177. Other subsequent disasters, including the Genpei war (1180-1185) and the 1181 famine, strengthened the belief that he was punishing his enemies from behind the grave. However, he didn’t become just any vengeful ghost, but one of the three greatest members of this category ever, next to Sugawara no Michizane and Taira no Masakado.

Sutoku was, in a way, the sum of many of the greatest fears of medieval Japan. The belief in his rebirth as a vengeful ghost coexisted with a tradition presenting him as a tengu - arguably one of the greatest tengu ever. This status is firmly ingrained into his image in later sources. Today he is frequently included in modern groupings of “three great youkai” alongside Shuten Dōji and Tamamo no Mae. It seems sometimes he’s replaced by Ōtakemaru, but honestly I think he is more worthy of this spot, and also even though this is ultimately a synthetic modern group, it’s much more representative of medieval culture to have a tengu alongside an oni and a fox.

A strikingly tengu-like vengeful Sutoku, as depicted by Yoshitsuya Utagawa (wikimedia commons)

While peculiar, Sutoku’s dual role as a tengu and a vengeful spirit is not entirely unique. Initially these two categories were pretty firmly separate. Tengu obstructed attaining enlightenment and rebirth in a pure land; vengeful ghosts, as their name indicates, were focused on personal vengeance. However, in popular imagination they overlapped, as evident for example in members of both groups scheming together in the Taiheiki. This most likely reflects the overlap between the perception of enemies of Buddhism and enemies of the state. Vengeful ghosts were typically members of factions who lost one political struggle or another, and their vengeance was aimed at the establishment.

Regardless of Sutoku’s supernatural taxonomic position, his post-mortem fate is tied to the fact he was a devout Buddhist. All accounts of his exile stress that he spent much of his time copying sutras. According to a rumor first attested in 1183, he also wrote a curse on their backs using his own blood, vowing to become a “demon king” - (a) Mara - due to perceived injustice he faced. There is no evidence it’s based on a historical event, even though it’s not impossible Go-Shirakawa did believe in it. At the very least, he definitely saw the deceased Sutoku as a supernatural threat, as he had various ceremonies performed in hopes of pacifying him.

Hōgen Monogatari, composed in the early fourteenth century, asserts that he became a tengu while he was still alive. When his request to deposit the completed manuscripts in a temple in Kyoto was denied by Go-Shirakawa, he vowed to remain his enemy in future lives, and stopped cutting his nails and hair. This symbolically marked his transformation. However, a former emperor couldn’t just become any tengu. Therefore, for instance in the Taiheiki he is described as a leader of the tengu, and his bird form is that of a golden kite.

Up to 2022, the Touhou wiki used to claim that “among Touhou fans, it is almost a general idea that the Tenma is inspired by Grand Emperor Sutoku” (not sure what is the “grand” doing here, there’s no such a title as daitennō as far as I am aware, but I digress), as you can see here. I will admit I’ve never encountered this headcanon - you will generally be hard pressed to find Touhou headcanons relying on actual mythology that aren’t just some variety of power level wank or otherwise all around awkward - so I think removing it was the right move (I don’t think the replacement is any better considering Mara is not a “Hindi god” - Hindi is a language, not a religion - but that’s another problem).

I’m also not aware of any Sutoku fan characters save for Tenmu Sutokuin from the fangame Mystical Power Plant who isn’t even supposed to be a take on the canon Tenma. Design-wise she clearly leans more into the vengeful spirit side of things (to the point the design would work better as Michizane than Sutoku, really, though I don’t dislike it). The filename on the wiki misspells her name as Tenma, but I have no clue whether this has anything to do with the strange headcanon assertion from the Tenma article. The closest thing to a Tenma reference she gets is a spell card referencing the sixth heaven, but the game refers to her merely as a “great tengu”.

Kōgyo Tsukioka's illustration of a performance of Matsuyama Tengu, with actors playing Saigyō, Sutoku and another tengu (wikimedia commons)

MPP aside, there's a lot of room for Sutoku in Touhou. The poet-monk Saigyō, whose life and works served as a loose inspiration for the plot of Perfect Cherry Blossom and Yuyuko’s character, went on a journey through locations associated with the late ex-emperor four years after his death, in 1168. He felt a personal connection to him because before being ordained he served as a guard of the imperial palace during his reign. This unconventional pilgrimage to at the time peripheral, sparsely inhabited areas was both a form of paying respect to his former superior, and possibly a way to pacify his vengeful spirit.

Saigyō obviously did not meet the deceased Sutoku, and ultimately only two of his poems deal with his downfall. However, later legends kept expanding upon their connection. This eventually culminated in the development of a tale according to which the monk in fact encountered Sutoku in the form of either a vengeful spirit or a tengu. The noh play Matsuyama Tengu is based on it. Its title is derived from the name Sutoku’s first residence after his exile. As a curiosity it’s worth pointing out the play singles out Sagamibō (相模坊), the tengu of Mt. Shiramine, as an ally of Sutoku - an ideal candidate for a stage 5 sidekick, if you ask me.

Some further interesting developments regarding Sutoku’s tengu identity took place in the Edo period, but I’ll discuss them in a separate section later.

The other tengu emperor: Go-Shirakawa

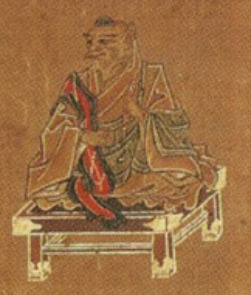

A portrait of Go-Shirakawa (wikimedia commons)

While Sutoku’s opposition to Go-Shirakawa essentially was the first step to the development of the belief he was a tengu, the latter also came to be viewed as a member of this category. While still alive, no less. One of the first sources to identify him as a tengu is a letter of his contemporary Minamoto no Yoritomo. He refers to the emperor as the “greatest tengu of all Japan” because of his notoriously fickle political positions. He at one point approved Minamoto no Yoshitsune’s plan to suppress Yoritomo, just to reverse this decision and declare Yoshitsune is acting on behalf of a tenma.

The notion of Go-Shirakawa being a tengu is present in the Heike Monogatari as well. In the scene I already mentioned, Sumiyoshi informs Go-Shirakawa that extensively studying Buddhist texts made him arrogant, and that he’s already attracting the attention of tengu. It is just a matter of time until he will be reborn as one of them himself. Stressing his religiosity is meant to show how it is possible for him to become a tengu in the same manner as monks.

Go-Shirakawa’s tengu career arguably peaked with his portrayal in Hirasan Kojin Reitaku. It states that both him and Sutoku became tengu, but it is the former whose “power is beyond comparison”. However, he plays no bigger role in the narrative, and he’s not described as a leader of the tengu, or even as the most powerful of them. In the absence of Ryōgen, it is apparently his contemporary Yokei (余慶; 919-991) who became the most powerful tengu. Go-Shirakawa doesn’t even get to be the second most powerful - that’s apparently Zōyo (増誉; 1032–1116). As far as I am aware, no distinct legends about these monks becoming tengu exist, so much like the elevated position of Go-Shirakawa this seems like a peculiarity of Hirasan Kojin Reitaku.

Early twentienth centiury depiction of a typical shirabyōshi costume (wikimedia commons)

While Go-Shirakawa doesn’t appear in any particularly significant pieces of tengu literature otherwise, his personal quirks are responsible for a somewhat obscure aspect of tengu background. A further detail revealed in the Hirasan Kojin Reitaku is that tengu are connoisseurs of all sorts of performances, but enjoy the dances of shirabyōshi in particular. know, I brought this up already in the previous article, but I think it’s a fun detail. Think of the sheer potential of a tengu shirabyōshi character (whether in Touhou context or elsewhere), also.

From celebrated saint to reviled tengu and back again: Ippen

A statue of Ippen from Hōgon-ji, apparently destroyed in a fire in 2013 (wikimedia commons)

Ippen is here more as a curiosity than anything, since he isn’t really a mainstay of tengu literature. Like Ryōgen and the two emperors-turned-tengu, he was a historical figure. He lived from 1238 to 1289 and founded the Jishū school of Pure Land Buddhism. He spent much of his life as a wandering preacher, advocating a unique form of nenbutsu (chanting the name of Amida), the self-explanatory nenbutsu dance (念仏踊り, nenbutsu-odori).

Legends assert that various miracles occurred thanks to Ippen’s devotion. For instance, at one point the nenbutsu dance he initiated made flowers fall from the sky. On another occasion, purple clouds appeared above him. Stories of his various miraculous deeds were retold in the form of picture scrolls, such as Ippen Hijiri-e (一遍 聖 絵; “The Illustrated Biography of Ippen”).

Ippen’s activity, in particular the dance he promoted, was evidently controversial among his contemporaries. Tengu Zōshi refers to him as the “chief tengu”, and portrays the practices he spread negatively. An entire explanatory paragraph is devoted to stressing the disruptive character of nenbutsu he promoted. Alongside other unorthodox behaviors it is blamed for various social ills including the fall of the Song dynasty in China (sic).

The opposition of other Buddhist schools to certain early currents within the Pure Land movement was often rooted in the rejection of the worship of deities and even Buddhas other than Amida. Of course, today it’s not hard to find people incorrectly convinced Buddhism is a “religion without gods” (this is a phenomenon so widespread it was actually considered a major obstacle by researchers of the history of Buddhism). However, through the middle ages devas, kami, Onmyōdō calendar deities and various figures like Dakiniten or Matarajin who defy classification altogether were anything but marginal in most schools of Buddhism in Japan. Oaths were sworn by Taishakuten and his entourage, Enmaten and Taizan Fukun were invoked in popular rites meant to guarantee good fortune, and so on.

Interestingly, Tengu Zōshi does not deny that miracles attributed to Ippen really happened. In fact, they are even depicted in the illustrations. However, the reader is expected to realize they are implicitly not a genuine display of Buddhist holiness, but merely a tengu trick meant to lead people astray. This is essentially a twist on stories already common in the Heian period, something like the tengu pretending to be a Buddha in a famous story from the Konjaku Monogatari adapted to reflect the anxieties of the Kamakura period tied to new religious movements.

The condemnation of Ippen goes further than merely implying his miracles were trickery, though. While in the final section of the scroll it is revealed that with enough effort even a tengu can attain buddhahood, Ippen is singled out as incapable of that. He is destined to fall even further from grace and to be reborn in the realm of beasts.

Despite the circulation of such negative opinions about Ippen among his contemporaries, Jishū school ultimately survived past the Kamakura period, and it still exists today.

Tengu caught between history and fiction: Tarōbō

Tarōbō in a mandala from Mt. Atago (via Patricia Yamada's Bodhisattva as Warrior God; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Tarōbō (太郎坊) is the tengu of Mount Atago. This location’s association with the tengu is well attested, and for instance in Hirasan Kojin Reitaku multiple of them are said to reside there, including Yokei, Zōyo and Jien.

However, Tarōbō is not identical with any of these historical monks. He’s an interesting case because it would appear he stands exactly on the border between historical figures and literary characters. One of the first attestations of him, if not the first one outright, has been identified in the Tengu Zōshi. On an illustration showing a gathering of tengu leaders, who are mostly identified by the names of schools of Buddhism they represent, one is instead given a specific name, Atago Tarōbō (愛石護太郎房). His notoriety continued to grow in later sources: Taiheiki presents him as a well known tengu, while Heike Monogatari outright labels him the “greatest tengu in all of Japan”.

While Tengu Zōshi and other early sources don’t provide any information about Tarōbō’s origin, in later tradition he came to be identified with the legendary Korean monk Nichira (日羅). His name would be read as Illa following the Hanja sign values, and at least some authors prefer using this reading or list both. I’m sticking to Nichira here, to maintain consistency with a name sometimes used to refer to his tengu form, Nichirabō (日羅坊; “the monk Nichira”).

A statue of Nichira (amagasaki-daikakuji.com; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Nichira is mentioned for the first time in the Nihon Shoki, in the section dedicated to the reign of emperor Bidatsu (late sixth century). He is described as an inhabitant of Baekje, one of the three Korean kingdoms which existed at the time. However, his father came there from Japan. The emperor seeks his help with navigating foreign policy. After some tribulations - apparently the king of Baekje didn’t want to let him go - he finally arrived in Japan in 583, armed and on horseback. He starts acting as an advisor to the emperor.

After a few months, Nichira is assassinated by other Baekje envoys present in the court since he wants the emperor to pursue rather aggressive foreign policy (most notably, he suggests ruthlessly slaughtering any potential settlers from Baekje who would try to establish settlements in Japan). The assassination has to be delayed, because he emits supernatural light at night. That’s not where his apparent supernatural powers end - after being killed he resurrects for a moment in order to make it clear his assassination was not a plot of Silla (another Korean kingdom). He is later buried, and no further mention is made of him.

While some elements of the Nihon Shoki account were retained in later legends about Nichira, especially his arrival from Korea and his ability to emit a supernatural glow, he was otherwise essentially entirely reinvented. Instead of an advisor of emperor Bidatsu, he came to be portrayed as a Buddhist monk and as an ally of prince Shotoku.

An early example of such a legend is preserved in Nihon Ōjō Gokuraku-ki (日本往生極楽記; “Japanese records of rebirth in a Pure Land”) from the late tenth century. It states that Nichira met with Shotoku when the latter was still a child, and declared he was a manifestation of Kannon. The prince in response recognized him as the reincarnation of one of his disciples from an unspecified past life. We also learn that he is capable of emitting light because of his devotion to Surya, the personification of the sun. There’s no real chronological issue here: while Nihon Shoki doesn’t mention Shotoku (or Buddhism, for that matter; it first comes up a year after Nichira’s death there) in any passages dealing with Nichira, the prince would indeed be a kid at the time of his arrival.

Things get more complicated later on. True to his portrayal as a ruthless enthusiast of military operations, Nichira came to be described as aiding Shotoku in quelling Mononobe no Moriya and his allies. Following the conventional chronology this would have happened long after Nichira’s death, though. A possible attempt at reconciling obviously contradictory traditions can be found in Ōe no Masafusa’s Honchō Shinsenden (本朝神仙伝), as you might remember from the Ten Desires post from last year.

In contrast with virtually every other source dealing with Shotoku’s genealogy, Masafusa claims the prince was a son of Bidatsu, which would make him considerably older at the time of Nichira’s arrival. The meeting between them is fairly similar to the Nihon Ōjō Gokuraku-ki version: Nichira recognizes Shotoku as a manifestation of Kannon, and both of them then emit supernatural light. No mention is made of any military help, though.

The portrayal of Nichira as a military ally of Shotoku is present in legends which link him with tengu. After the defeat of Moriya, he supposedly left to take over Mt. Atago. According to a guide to famous places (名所記, meishoki) from 1686, Kyōwarabe (京童; “Children in Kyoto”) by Kiun Nakagawa (中川喜雲; 1636-1705) he did so in the form of a tengu.

Atago Gongen (wikimedia commons)

Bernard Faure notes there is a similar legend in which Nichira is a separate figure from Tarōbō. The former, portrayed as a military official in the service of prince Shotoku, sets on a journey to pacify the tengu of Mt. Atago. He accomplishes this by revealing he is a manifestation of Shōgun Jizō (勝軍地蔵), a Kamakura period reinterpretation of this normally peaceful bodhisattva as a fearsome warrior, historically worshiped on Mt. Atago as Atago Gongen. Nichira then becomes the leader of the tengu, while Tarōbō provides him with information about the mountain.

Something that surprised me is that there is a single Korean source which mentions the tradition presenting Nichira as a monk who became a tengu. During the Imjin war, a failed Japanese invasion of Korea, the Korean Neo-Confucian philosopher Kang Hang was captured and subsequently spent three years (from 1597 to 1600) in Japan as a prisoner of war before escaping (possibly with the help of Seika Fujiwara, a fellow Neo-Confucian scholar he befriended). He wrote a memoir dealing with this experience, Kanyangnok (“The record of a shepherd”) in which he mentions Nichira in passing. He states that he was known as Tarōbō, and that he was enshrined and worshiped as Atago Gongen.

Something that’s worth pointing out is that despite living centuries apart, Ōe no Masafusa and Kang Hang both make the same mistake, stating that Illa arrived in Japan from Silla, as opposed to Baekje. I thought this might represent an alternative tradition, but in both cases translators pretty firmly conclude we’re dealing with a mistake. My best bet would be that this has something to do with the Japanese name of Silla, 新羅, sharing a kanji with Nichira’s own name; the name of Baekje, 百済, does not. It doesn’t seem any later legend brings up his post-mortem effort to clear the name of Silla envoys from the Nihon Shoki, so I don’t think that was necessarily a factor.

I’m actually shocked I haven’t seen a Touhou take on Nichira, considering his association with Shotoku. In particular, it’s worth pointing out that his transformation into a tengu is essentially how people tend to mistakenly assume the connection between Matarajin and Hata no Kawakatsu works (in reality, it’s very limited in scope and indirect, but that’s a topic for another time). Plus there’s a lot of storytelling potential in having a tengu - or even Tenma - be yet another character from Miko’s past. ZUN isn’t very interested in building upon prince Shotoku legends involving Kawakatsu or Kurokoma, but it’s hard to deny they’re a popular topic in fanart.

Yet another tradition about the identity of Tarobō, as far as I can tell entirely independent from his connection to Nichira, is preserved in the Engyōbon, the oldest version of Heike Monogatari. A gloss states that he is the tengu form of the monk Shinzei (真済; 800-860), who in a tale from Konjaku Monogatari and a variety of other sources menaced empress Somedono (染殿后; Fujiwara no Akirakeiko), the wife of emperor Seiwa.

Tarōbō also plays a role in a tale unrelated to speculation about his origin, Kuruma-zō Sōshi (車僧草紙; “Tale of the handcart priest”). It was originally composed in the sixteenth or seventeenth century. The eponymous protagonist is a Zen practitioner who, as his name indicates, travels with his handcart in tow. Tarōbō attempts to convince him to abandon this lifestyle. They engage in a Zen dialogue (mondō), in which the monk triumphs over the tengu. He also manages to overcome Tarōbō’s subordinates who attempt to make him stray away from his practice by showing him gruesome images of battles in the realm of the asuras.

Finally, under the name Nichirabō Tarōbō appears in the tale of Zegaibō. Initially I planned to only dedicate a single paragraph to it, but I figured Zegaibō is such a fun figure that a separate section is warranted.

Not a tiangou: Zegaibō, the Chinese tengu

Zegaibō taking a bath (wikimedia commons)

The history of Zegaibō (是害坊) starts before he even got this name. In the anthology Konjaku Monogatari, there are a handful of stories about tengu arriving in Japan from overseas - specifically from India or China. These are obviously literary fiction, as there is nothing quite analogous to tengu in Indian literature, and while their name is borrowed from Chinese tiangou, this term also doesn’t have all that much to do with tengu, ultimately.

One of the aforementioned stories focuses on a Chinese tengu named Chira Yōju (智羅永寿; I was unable to establish whether there’s any connection with 智羅天狐, the alternate name of Iizuna Gongen, Chira Tenko) He arrives in Japan to challenge local Buddhist monks. He reveals that he has previously bested these in his homeland successfully, and that he would like to check how their Japanese peers compare. Local tengu take him to Mt. Hiei, where he unsuccessfully tries to bait major Tendai monks, including Ryōgen, into battling him. He is eventually beaten up by Ryōgen’s attendants, and after his defeat the Japanese tengu take him to a hot spring so that he can recover. In the end he decides to return home.

It was possible to establish that Chira Yōju was the basis for the tale of Zegaibō because the colophon of an illustrated scroll known simply as Zegaibō Emaki (是害坊絵巻) states that the story draws inspiration from a similar tale from the lost collection Uji Dainagon Monogatari. Based on other sources it is assumed it was most likely identical with the Konjaku Monogatari account of the misadventures of Chira Yōju. Save for the change of the main character’s name, the stories do not differ much. More time is dedicated to the meeting between Zegaibō and the Japanese tengu, though. They are led by Nichirabō from Mt. Atago.

Zegaibō meeting with his Japanese peers (New York Public Library Digital Collections)

Zegaibō evidently became a popular, recognizable character later on. This might reflect a sense of patriotism (or nationalism) the story possibly could have inspired in the readers: the Japanese monks are portrayed as more resistant to the schemes of demons than their continental peers, after all. However, it’s also possible that Zegaibō’s defeat was interpreted as a take on tensions between Buddhist monks and shugenja, considering the latter were commonly compared with tengu.

Regardless of which interpretation is correct, Zegaibō’s undeniable popularity allowed him to reappear in a variety of other tales. There is a noh play which simply adapts the tale about him, Zegai. The events are largely the same, though the name Tarōbō is used instead of Nichirabō to refer to the tengu of Mt. Atago. Bernard Faure mentions that in one version of the legend about Nichira’s arrival on Mt. Atago, he defeats Zegaibō, here portrayed as the leader of the local tengu. The tengu subsequently reveals the “sacred geography” of Japan to him. Finally, Zegaibō plays a major role in the Edo period puppet play Shuten Dōji Wakazakari (酒呑童子若壮; “Shuten Dōji in the Prime of Youth”).

In this work, Zegaibō is indirectly responsible for the transformation of the eponymous character into an oni. After a rampage which left 160 monks dead and various other heinous acts, the young Shuten Dōji, known simply as Akudōmaru (悪童丸; “evil child”), proclaims that there has never been anyone more mighty than him in Japan, China or India. This display of arrogance alerts Zegaibō, who appears in the guise of a young monk and offers to wrestle with him so that he can prove his strength. However, as soon as the fight starts, he reveals his true form and takes Shuten Dōji into the air.

Zegaibō presents Akudōmaru to Maheśvara (via Keller Kimbrough's Battling Tengu, Battling Conceit; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Zegaibō then brings his opponent to Maheśvara (摩醯首羅王, Makeishuraō; a phonetic transcription is used in place of the most common Japanese form 大自在天, Daijizaiten). The latter is unexpectedly described as a maō. Zegaibō seemingly presumes that his boss will punish the unruly human by turning him into a tengu, but Maheśvara is so impressed by his bravery that he chooses to turn him into an oni to let him cause even more chaos. This is rather obviously distinct from the more widespread versions I discussed in the not so distant past.

From makara to tengu: Konpira

A typical depiction of Konpira as one of the heavenly generals (via Bernard Faure’s Rage and Ravage; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

While Zegaibō according to tales focused on him arrived from China, there is technically a tengu whose origins were believed to lie even further away - Konpira (金比羅). However, he is a special case because despite being arguably one of the most famous tengu, he actually wasn’t viewed as a member of this category for most of his history.

Konpira is a Japanese transliteration of Sanskrit Kumbhīra. This name can be literally translated as “crocodile”. His origin is poorly understood, though it is possible he was originally essentially a divine representation of reptilian inhabitants of the Ganges. As you can read here, the gharial, the mugger crocodile and the saltwater crocodile all can be found in this river in some capacity.

Fittingly, Kumbhīra is sometimes described as a makara who converted to Buddhism. This term refers to a type of partially crocodilian mythical hybrid, most notably depicted as the steed of Hindu deities such as Ganga and Varuna. Bernard Faure suggests that in Japan he might have been analogously understood as a wani at first. However, Kumbhīra could also be portrayed as a yaksha, for example in the Golden Light Sutra. What remained consistent is the idea that he was a fierce being converted to Buddhism.

Kumbhīra is well known as the foremost of the Twelve Heavenly Generals (十二神将, jūni shinshō). It is possible that the crocodilian Kumbhīra and the homonymous heavenly general were initially separate deities, though in Japanese context they are effectively the same. Konpira and his peers are regarded as the protectors of the Buddha Yakushi but historically were simultaneously perceived as a type of shikigami. I will only discuss this role more in my next article, though, as it is not very relevant here. All you need to know is that it made him a commonly invoked protective deity in apotropaic rituals.

An interesting legend pertaining to this aspect of Konpira’s character is preserved in the Taiheiki. When Fujiwara no Yasutada (藤原保忠; 890-936) fell ill, a Buddhist priest arrived to perform a ritual focused on Yakushi and his heavenly generals to heal him. However, as soon as he started to invoke Konpira, Yasutada got so horrified that he died. The ritual has apparently been hijacked through supernatural means, and what he heard was not the name “Konpira” but rather the phrase kubi kiran - “I’ll cut off your head”. This was an act of vengeance of the spirit of Sugawara no Michizane - Yasutada was one of the courtiers who conspired to exile him earlier. Evidently after he became a vengeful spirit he was able to essentially turn Konpira to his cause and reverse the effects of invoking him.

While the heavenly generals are associated with the Chinese zodiac, the correspondences between the individual deities and zodiacal animals aren’t really consistent. Konpira can variously be linked with the tiger, the rat or the boar, and accordingly with the northeast, north or northwest. The northeastern link is particularly significant, as in some cases it led to conflation between him and Matarajin, who as a subduer of demons was strongly associated with this direction.

A variant of the legend in which Saichō, the founder of Tendai, meets Matarajin during his journey to China identifies the latter with Konpira. Supposedly Konpira slash Matarajin was originally the protector of the Vulture Peak in India, then moved to Mount Tiantai in China, and finally reached Mount Hiei in Japan with Saichō.

The two were also equated with each other by the Tendai priest Jōin (乗因; 1682–1739) in the Edo period. However, his attempt was actually met with criticism from his contemporaries. A certain Sōji Mitsuan (密庵僧慈) wrote in 1806 that Jōin was evidently confused because Matarajin and Konpira are clearly separate deities. He concludes he evidently didn’t even read the Mahāvairocana Sutra. I’m honestly surprised ZUN didn’t reference this conflict over syncretism in any of Okina’s spell cards, it would fit right in.

Konpira Daigongen (wikimedia commons)

Despite Matarajin’s tengu credentials, which I discussed last month, the association between him and Konpira actually isn’t why the latter came to be seen as a tengu. This phenomenon instead began as an aspect of his role as the protective deity of Matsuo-ji on Mt. Zōzu (象頭山) in Shikoku. Here he came to be worshiped under the name Konpira Daigongen (金毘羅大権現). His enshrinement apparently only occurred in 1573, though according to a legend from the seventeenth century he arrived there much earlier, and already resided on Mt. Zōzu in the times of En no Gyōja. However, there is no reference to him in the few earlier sources dealing with this location. Since its name can be translated as “Mt. Elephant Head”, it has been suggested that it might have been associated with Shōten, the Japanese form of Ganesha, in earlier periods, though this remains speculative.

Despite Konpira’s new role as a mountain god, his early aquatic connections were not entirely lost. In the eighteenth century he came to be seen as a protector of maritime routes through the Seto Inland Sea and tutelary god of navigation. This reflected the growth of importance of inland maritime trade which was a result of the shogunate's ban on most foreign trade.

Interestingly, while most donations were made to Konpira by local sailors and merchants, his new role made him so famous that Chinese traders residing in Nagasaki prayed to him too, and a small shrine was even erected in that city at one point. Donations made by travelers from the Ryukyu Kingdom are recorded too. Both of these phenomena were highlighted in Edo travel books in order to stress the prestige of Konpira.

Kongōbō (Universität Wien's Religion in Japan: Ein digitales Handbuch)

Konpira didn’t become a tengu right away. The oldest recorded tradition associating Mt. Zōzu with a specific tengu refers to him as Kongōbō (金剛坊; “diamond priest”). He was not (yet) a form of Konpira, but rather a deified seventeenth century Shingon monk, Yūsei (宥盛), who between 1600 and 1613 served as the abbot of Matsuo-ji.

It seems Yūsei actually created the image of himself as a tengu on his own - in 1606 he commissioned a statue depicting him as a tengu manifestation of Fudo Myōō. The inscription explicitly states that he “entered the way of tengu” in order to bring fame to the mountain. This was a part of a bigger project of portraying himself as a master of various esoteric arts in order to gain the patronage of local nobles. After he passed away, his disciples and relatives continued spreading the image of his tengu form, now renamed Kongōbō. He eventually came to be seen as a manifestation of Konpira.

In popular imagination the new tengu-like image of Konpira eventually came to be detached from its actual origin. He was instead identified as emperor Sutoku simply because both were associated with roughly the same area - the historical Sanuki province. This idea was popularized by the 1756 play Konpira Gohonji Sutokuin Sanuki Denki (“The Sanuki Legend of the Retired Emperor Sutoku, the Original Source of Konpira”) by Izumo Takeda II. Various other authors followed in his footsteps, including Akinari Ueda and Bakin Takazawa, strengthening this equation.

While I focused on the early portrayal of Konpira and on his eventual transformations into a tengu, the traditions of Mt. Zōzu continued to evolve in subsequent centuries. After the separation of Buddhism and Shinto, Konpira came to be viewed as a kami. Due to the influence of Atsutane Hirata and his disciples he received a new name, Kotohira (金刀比羅) after the Meiji reforms. However, many lay people continued to refer to the protector of the mountain as Konpira. Today both forms of the name are in use.

Bibliography

Tumblr doesn't let me post the bibliography as a part of the article for some reason. You can find it here in the form of a google doc.

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ive had a headcanon for a little over 2 years now that Ryuu at one point or another has a couple of journals buried somewhere... That, or with the assistance of maybe Soseki, publishes his own book(s) about his time in London and other experiences hes had.. I mean like, a little later in life- by the time hes in his mid 40s or 50 ish.

I think Kazuma would have another journal at some point too, since that part is canon to him already.

0 notes

Text

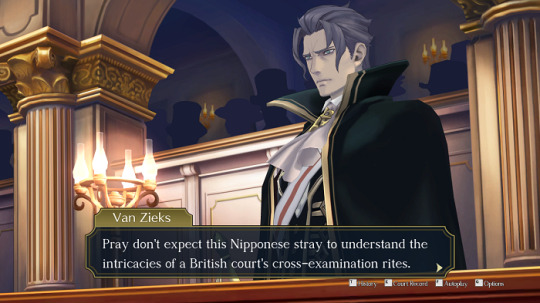

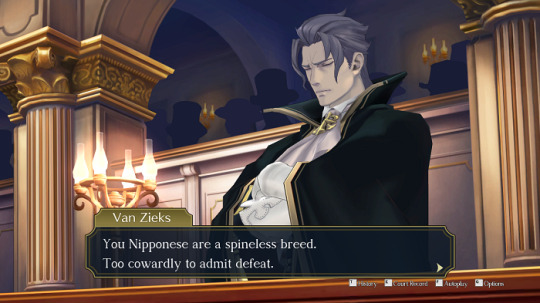

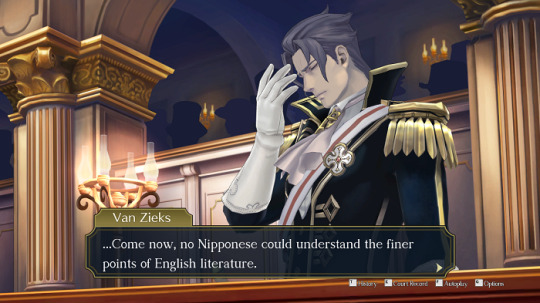

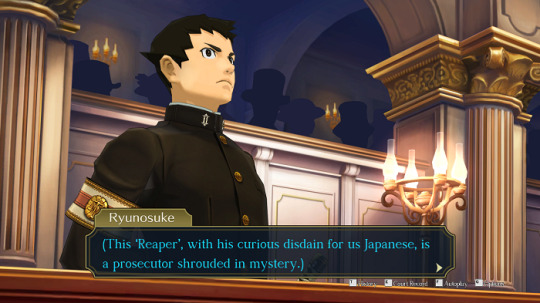

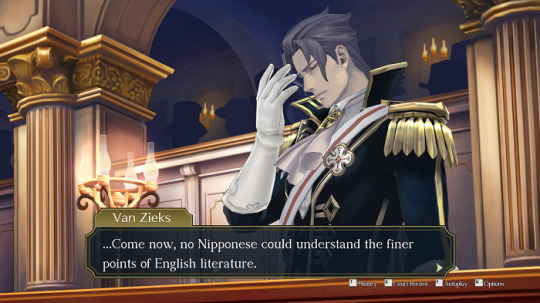

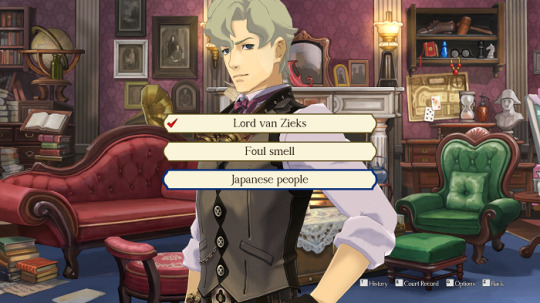

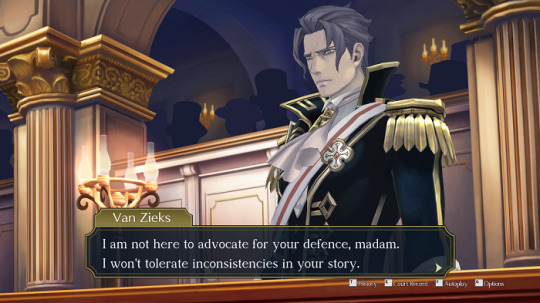

Van Zieks - the Examination, part 12

Warnings: SPOILERS for The Great Ace Attorney: Chronicles. Additional warning for racist sentiments uttered by fictional characters (and screencaps to show these sentiments).

Disclaimer: (see Part 1 for the more detailed disclaimer.)

- These posts are not meant to be taken as fact. Everything I’m outlining stems from my own views and experiences. If you believe that I’ve missed or misinterpreted something, please let me know so I can edit the post accordingly.

-The purpose of these posts is an analysis, nothing more. Please do not come into these posts expecting me to either defend Barok van Zieks from haters, nor expecting me to encourage the hatred.

- I’m using the Western release of The Great Ace Attorney Chronicles for these posts, but may refer to the original Japanese dialogue of Dai Gyakuten Saiban if needed to compare what’s said. This also means I’m using the localized names and localized romanization of the names to stay consistent.

-It doesn’t matter one bit to me whether you like Barok van Zieks or dislike him. However, I will ask that everyone who comments refrains from attacking real, actual people.

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

Part 5

Part 6

Part 7

Part 8

Part 9

Part 10

Part 11

Let's bring this thing home! It's time for the conclusion of the essay series!

Conclusion

With a stupidly long essay series behind us, it's time to look at what we've learned! Let's go back to Part 1 and review what we needed from Van Zieks's character development for a fully rounded redemption arc, shall we?

1) Present an antagonistic (possibly immoral) force who personifies Ryunosuke’s biggest personal obstacle/weakness, in this case racial prejudice.

2) Humanizing traits begin to show.

OPTIONAL: A backstory to justify any immorality he has.

3) Over time, Barok has his realization and sees the error of his ways.

4) Barok atones for his immorality, not simply through apology but by taking decisive steps.

5) The cast around him acknowledges his efforts and forgives him.

And looking at the main game (plus additional dialogue), we have...

1) Antagonistic force:

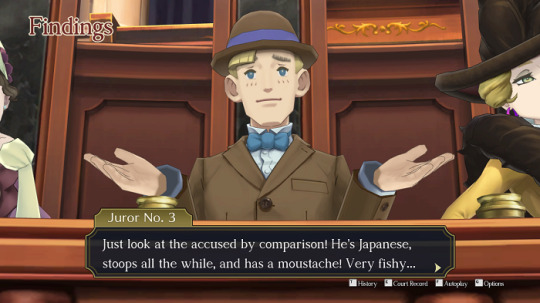

Etc. etc. I have many of these. We can all agree that as an antagonistic force, he does his job quite well. CEO of Racism and White Privilege in the flesh. It works, since we as the audience get very frustrated and want to see him defeated.

2) Humanization:

Giving him an old friend to be a defendant was a brilliant move, really. Albert's reflection on the friendship and the person Van Zieks used to be really helped flesh him out and make him appear more like a human being with, y'know, emotions and weaknesses. The little snippets of dialogue in his office really help too. Presenting evidence can also lead to fun tidbits. All in all, considering how gruff and distant Van Zieks is, they really did their very best to humanize him. The writers were given very little to work with but they exploited every opportunity to come their way.

OPTIONAL backstory:

Again, I don't think we needed a tragic backstory to have a well-rounded, redeemable character. Still, it ties in very expertly to the game's plot and the motivations of quite a few other characters. The story of Klint van Zieks and his death isn't necessarily Barok van Zieks's backstory, it's the center of an intricate web which also holds Kazuma, Stronghart, Gregson, Jigoku, (S)Holmes, Mikotoba, Sithe, Drebber- I could go on. A LOT. So because of how very integrated it is into the main narrative's recurring themes and characters, I'll give it props for being relevant and well thought out.

The bigger question is: Does it justify his immorality? Not entirely. I think the game could have gotten more out of this if they'd involved the other two exchange students in this tale just a bit more. They could have given more attention to how Jigoku's aggressive behavior in the trial impacted Van Zieks, and explained whether he might've suspected Mikotoba of sabotaging (S)Holmes's investigation. If the narrative had done that, all three Japanese people to come to London would have been ‘the bad guy’ in Van Zieks's eyes and it would have given more credence to his racial generalization. They could have also given more attention to how the people around him reacted to Genshin being the Professor, because I'm sure Stronghart and Gregson stoked the fire in terms of xenophobia. As it stands, there isn't really enough there to justify hatred of an entire race as opposed to just one person.

3) Realization/Redemption

We see him already start to realize the error of his ways around the end of 1-5, which is technically only about halfway into the full narrative. Unfortunately, thanks to 2-2 being played afterwards (but chronologically set before 1-5), any progress made in 1-5 can become invalidated in the player's eyes. Growth works best when it's done linear. Don't get me wrong, flashbacking to earlier times when a character is still more morally tainted can work well, but it needs to be executed properly. Barok's behavior in 2-2 is downright insulting towards the audience itself and therefore, it causes emotional friction when relaying the narrative endgoal of redemption. It also makes it extra jarring when we hit 2-3, and suddenly Van Zieks is meant to be relying on the protagonist's desire to expose the truth. How on earth can we as the audience trust that Van Zieks believes in Ryu's abilities when we just came fresh out of a case where this man actively sabotages Ryu's efforts?

Still, the line of redemption continues from 2-3 into 2-4 well enough. He admits that he was wrong- that his hatred was illogical and that he needs to change. This is the very definition of redemption. I need to stress once more this is not to be confused with atonement, which comes next.

4) Atonement

Here it is. It's not enough to simply acknowledge mistakes; one needs to work hard to fix them. Since Van Zieks is the defendant for two whole episodes, equaling roughly 20% of the full narrative and 67% of the time following his first true realization (chronologically), there isn't much that he can actively do to atone. Because remember, not only do these actions need to fit the situation he's currently in, they need to fit his personality. These two limitations ensure the atonement mostly takes the form of dialogue. Of apologies.

One might want to point out that he never apologizes specifically for his racism, but there's a reason for that. If you pay close attention, you'll notice that there isn't a single character who ever uses a word like “racism”, “xenophobia” or even “racial prejudice” in this game. It's for the same reason you'll never see an Ace Attorney character utter words like “alcoholism”, “drug abuse” or “depression”. These things may be implied very strongly, to the point where you'll know for certain a character is suffering from it, but it's never given these exact labels. It has to do with the tone of the game. In Great Ace Attorney's dialogue, Barok van Zieks is only ever described as holding “a deep hatred for Japanese”, which is then the only thing he could apologize for. And he does, so long as you aren't looking for a literal phrasing of “I apologize for my deep hatred of your people”.

Regardless, he can't take more active, decisive action until he's freed from prison and two scenes with Van Zieks later, the game has ended. He still manages to take two actions, though! The first is to publicize the truth of the Professor, taking the blame of the mass murders off Genshin's shoulders (and losing his own privilege in the process). The second is to take Kazuma under his wing as his disciple. I'm not certain there's anything else the narrative could have had him do. What is decisively missing, however, is the following:

5) Acknowledgment

The above aren't good examples of cast acknowledgment that Van Zieks is taking part in a redemption arc, rather, they're the best I could find. Characters are acknowledging that he's changing- that he's being kinder to them and they can get along with him now, but they're not acknowledging that he caused hurt in the first place. This, in my opinion, is the Great Ace Attorney's biggest narrative flaw. I've talked before about how Ryu's reaction to Van Zieks's racism is 'indirect communication', a typically Japanese manner of dealing with negativity. I've also talked about how Ryu is not in a position to speak up, as he's a literal minority who is there to represent his country in an official capacity and can’t afford to make enemies. However, characters like Susato and Kazuma are far more outspoken in their opinions, as is Soseki. The only one who ever calls Van Zieks out on his racism is the British judge, and even that is done very meekly. When an old crusty white guy is the one who condemns white privilege in a cast full of minorities, you've got a problem. The Japanese cast's refusal to acknowledge that Van Zieks's words were harmful is like Team Avatar telling Zuko that sure, he can join since he's a good guy now, but never once acknowledging that he burned down villages or betrayed everyone's trust in Ba Sing Se. There's something very vital missing, see? If indeed the cast had called Van Zieks out more actively on his harmful ways and how necessary it was for him to change, he in turn could have taken more atonement steps in response.

So, for the conclusion: Does Barok van Zieks tick all the necessary boxes for a complete redemption arc? Yes. In a very technical sense, all the requirements are there. But does that mean it's a successful arc? Not necessarily. The game has a few slip-ups, a few things not executed as well as they could have been. For that reason, whether the audience is satisfied with the arc is entirely up to them. Taking into consideration that they had to cram a whole lot of story into just two games- the second game in particular, I can acknowledge they did their very best with the limitations that were there.

And there we have it! That’s all I could think to say on the matter. I hope everyone who read this till the very end enjoyed it, maybe even learned a thing or two. I’m always open to questions, input and constructive criticism!

#dgs#dgs spoilers#tgaa#tgaa spoilers#barok van zieks#I'M FREE!#well until I tackle the DLC content#but until then...#FREEEE

36 notes

·

View notes

Note

Feeling kinda shy & don't want to be too much of a bother 😅, but could you give me some books recommendations pls? Just any book that you enjoyed reading, I'm looking for more reading material

There’s no need to be shy! Feel free to message me whenever you want, even if you just need someone to talk to. Plus, you’re awfully sweet and always a pleasure to interact with 🥰🥰

I have no idea what kind of genres you like, so this is going to be a mix of anything and everything, I hope that’s alright. Okay, let’’s go:

1. Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky

I think I’ve made it plenty clear by now how much I love Dostoevsky’s works 😅 Most people shy away from this book because it’s apparently too ‘prose heavy’ and difficult to understand. That might be true for some, but I absolutely loved it. The sketchy themes of morality and good and evil,, the complex and nuanced characters, their inner conflicts and turmoils and resolutions ughhh, it’s just all so. Good. Plus, the overall plot is very engaging too, and I couldn’t put it down once I started it.

2. The Book Thief by Markus Zusak

My absolute favorite book of. All. Time. Nothing I say about this will ever be able to adequately capture what it made me feel. I have read this book so many times and each time affects me more than the last. I think some of the pages might still be stained with my tears.

3. Kokoro by Natsume Soseki

I have no idea what to say about this book, except that I read it overnight and felt like a changed person in the morning. Very poignant and tactful in dealing with subjects such as misanthropy, guilt, sin, forgiveness, betrayal, and the ennui and pointlessness of human life. Should be required reading for everyone, as far as I’m cocerned.

4. The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini

This book made me feel so many emotions, I can’t even. The way it explores Afghanistan and both its everyday civilian life as well as the aspects of terrorism is really commendable. It paints a very vivid picture and makes you realize that it’s a real place, instead of just some myth and legend, with real people going through very real problems. It made me cry a lot, but I’d recommend this one strongly, especially to people living in the West or otherwise privileged places.

5. Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

I’m not putting many classics on this list because most people have already read many of those, but I just couldn’t stop myself from putting this one here. Absolutely no one is above the tender mutual pining, the sensual hand-brushing and stolen glances, the utter revolutionary romance of Jane Austen’s beautifully crafted, soft Georgian England, and anyone who thinks otherwise is wrong.

6. The Maze Runner Trilogy by James Dashner

If you’re into dystopian literature and no scared by trilogies, you’ll enjoy this. I know the premise sounds very typical of YA dystopia genre, but hear me out. The characters are really well structured, the plot interesting and fast paced, with plenty of foreshadowing and heart-breaking. It’s really up there with The Hunger Games in this genre. Combined with the two prequels, there are a total of five books, but it was really worth it for me.

7. Inferno by Dan Brown

Another one of those books that stayed glued to my hands until I finished it. It’s very fast-paced and thrilling, with the whole ‘chasing and being chased through the city’ and ‘time is running out’ deal. It’s set in various countries, and the amount of detail is incredible! Also, I’d say the plot is quite fitting in present circumstances 😝

39 notes

·

View notes

Note

ALL OF THE HARVEST MOON QUESTIONS >:3c

AH, I SEE HOW IT IS.

1. Which was your first HM?

Harvest Moon SNES was my very first, I had it on emulator when I was a little girl. (Shh, don’t tell anyone!! I did eventually buy the game for virtual console when possible.)

It was closely followed by Harvest Moon DS, which is probably the game I’ve put the most hours into.

2. If you have a few, which is your favorite HM?

…that said, I’ve owned the majority of Harvest Moon games. All in all, I think Animal Parade is probably my favourite, as it incorporates all the features I want out of a good Harvest Moon game into one.

3. If you could try any meal in HM, what would you choose? Why?

This is a tricky one – there’s lots of Harvest Moon games, and lots of dishes. I’m going to be boring and say I want to try the fried egg. But like, one made with the S* rank quality eggs. It has to taste better than one in real life, right?

4. Who was your first spouse? (Or who will it be?)

Since my first game was SNES, my first ever wife was Maria. She was a church girl, I could identify.

My first husband was probably … hm, you couldn’t marry dudes for a while, so I’m not sure. Pierre, perhaps? I played MFoMT late and IoH was one of the first times I got to marry as a girl.

I really wanted to marry Carl in MM, but in the EU version you can only play as a dude because of the rushed release.

5. What character do you most wish you could marry, either in-game or irl? Why?

CAAARRRLLL okay so while I would like to marry Carl, Gill (Tree of Tranquillity version over AP) is also my type. We’re both very serious about work. But also Carl would treat me better, I feel. I dunno man. All of the Harvest dudes are nice.

I’d like to marry, please.

I also want to marry Jeff but he’s, like, already married – but there’s also a game where he’s your rival for Elli so???

6. What do you pursue in a HM game first? Marriage? Wealth?

Marriage first. That said, sometimes you need wealth to get married – you can’t pay for house upgrades in love. So I try to maintain a balance.

There’s usually enough time to do farmwork as well as talk to everyone in a day.

7. There’s a moral to every story. What do you take away from HM?

I’m… not sure! All the games have different ‘messages’. I think it goes to show that building a sense of community – making friends – is important.

Although you shouldn’t make friends by giving them gifts every day. HM is just a little limited in its presentation.

8. Do you have a favourite character? Why or why not?

I do! Some of my favourite characters are Leia, Carl, Gill, Pierre, Soseki, Elli, Moriya, and countless others. I just really love the characters – it’s kind of one of the major game aspects!

9. If you could choose one of the HM games to live in, which would you choose and why?

Probably Trio of Towns, since there’s a lot of town variety, and I can see myself living and working in Tsuyukusa. But I wouldn’t mind living in Forget-Me-Not or Zephyr Town either!

10. What does HM mean to you?

EVERYTHING.

Seriously though, it’s my favourite game series. A lot of my inspiration comes from it, even if I don’t play it all the time like some other games.

Thanks for asking!!!! :3

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

New Life || SosiEvie

@arigatosmiles

Evelyn yawned in the morning, resting in bed as Soseki was busy preparing breakfast. One hand was behind her head while the other was delicately over a very round belly. Honestly...two weeks late? They were seriously taking their sweet time in there, weren’t they. For the past couple weeks, ever since the original due date passed, Evelyn had been taking it easy with the hospital already set to speed dial. After all, they were supposed to be born any day now.

Well, regardless, it was ending soon enough. Tomorrow, since the twins were taking their sweet time being born, she was scheduled to be induced. They couldn’t exactly take all the time they needed with being born.

She hummed, smelling something nice waft in from the kitchen. Ah...guess that meant it was time for her to get up. Evelyn sat up a little, swinging her legs around to the floor. And as soon as her feet touched the floor, she was immediately enveloped in pain.

Everything in her head stopped, her body completely freezing up in place. Everything was focused on this extreme, painful tightness in her stomach, so focused that it was all she could think about. Evelyn remained there frozen for several more moments until the tightness left as soon as it came. Her eyes shot open, and immediately, Evelyn knew what was happening. This was a feeling she never had felt before...and yet she knew right away what exactly it was.

“S...Soseki!” Evelyn called out, getting to her feet and waddling through the house as fast as she could, “We need to go. Now.”

--

Hours and hours later, and Evelyn was smiling. She felt absolutely exhausted, like a complete mess, and drained of everything. But the second she looked at the two children wrapped up in blankets, a tired smile graced her lips and she was already reaching for the twins. A boy and a girl, she was told. A boy wrapped in blue with the slightest bit of pink hair peeking out from the top and a girl wrapped in yellow, unfocused brown eyes already cracked open.

“Hey there...” Evelyn spoke softly, her voice a little hoarse from the many hours leading up to this moment. Eventually, the boy was cradled in her arms while her husband held the girl. And Evelyn couldn’t help but look from the baby in her arms to the baby in Soseki’s arms in absolute wonder. Part of her felt like crying, but she held back, instead holding the newborn securely in her arms.

Before, Soseki and her had decided on several names for different combinations. Two girl names and two boy names. So since they had one girl and one boy, there was no question on what they would name the children.

Aiko Eleanor Yamamoto and Hayato Max Yamamoto.

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

All you do is think. Because all you do is think, you've constructed two separate worlds—one inside your head and one outside. Just the fact that you tolerate this enormous dissonance—why, that's a great intangible failure already.

Natsume Soseki, And Then (Sorekara).

146 notes

·

View notes

Text

FEATURE: Anime vs. Real Life – “Tsukigakirei”

Ah, it’s that special time of year again, where almost every outdoor shot in an anime is jam-packed with graciously falling cherry blossom petals, marking the start of the spring season shows, which in turn means new and exciting anime locations for me to track down and write about. The premier of the first show I’ll be taking a look at was completely drenched in cherry blossoms – I’m of course talking about the very charming Tsukigakirei (as the moon, so beautiful).

Studio feel.’s original romance anime tells the story of Kotarou and Akane, two very shy teenagers in their third year of middle school, who are unconsciously starting to take an interest in each other. Tsukigakirei's grounded story and believable characters are supported by gorgeous pastel colored backgrounds, which are based on the show’s already quite lovely real-world setting – Kawagoe.

Tsukigakirei takes place in Kawagoe, a city in Saitama Prefecture, which is located only around 30 minutes away from central Tokyo. The city with its roughly 350,000 inhabitants often gets referred to as Little Edo, which is the old name for Tokyo, due to its many historic and traditional buildings shaping the townscape. Kawagoe really prospered during the Edo Period (1603–1868) as an important city to Tokyo for trade and strategic purposes. Nowadays the city is a popular tourist destination for day-trips from Tokyo, and maybe even a couple more tourists will find their way to Kawagoe now because of Tsukigakirei.

*All images were taken with GOOGLE STREET VIEW (shots I took myself are marked ‘WD’)

The opening shot immediately unveils the shows setting, and starts off with showing Kawagoe’s main street, Kurazukuri. Kura means warehouse in Japanese, and kurazukuri is the name of the construction style used for these fireproof clay-walled warehouses. Seeing these images, it’s probably easy to understand why the town is called Little Edo.

You might've also instantly recognized the setting if you were following last season’s Fuuka (or have been reading my articles), as Kawagoe was also the destination of Yuu’s and Koyuki’s date trip in the ninth episode.

WD

The opening shows us a quick shot of the Kumano Shrine located along the Taisho-roman Street. I took this picture last summer while visiting Kawagoe. Unfortunately, that was on the same day as Pokémon Go finally launched in Japan, and the city actually has free-WiFi, so I regrettably didn’t take all too many pictures that day. Kamisama Hajimemashita also took place in Kawagoe, and was the original purpose of my trip.

The beautiful spot we’ve seen in the opening and the promotional videos for Tsukigakirei is right behind the Hikawa Shrine, where cherry blossom trees are lined up on both banks of the Shingashi River. The cherry blossoms should also be in full bloom in real life as well now.

That’s Takazawa Bridge and the Motomachi-Mutsuzuka Inari Shrine in the background.

The anime’s visuals would have been beautiful all-around, if it weren’t for those awful-looking CG background characters. But the backgrounds themselves look gorgeous and are pleasant to look at, like this shot of the Kawagoe City Daisan Middle School. The only problem is, that there is no such middle school in Kawagoe. Instead, the school shown in Tsukigakirei is based on Myojo Gakuen Elementary School, which is located in Musashino, a city in the western portion of the Tokyo Metropolis. It might be a bit too early to tell, but this almost seems like a growing trend lately, and was also done by last season's Interviews With Monster Girls or Masamune-kun’s Revenge, where the schools were also located somewhere completely different from the show’s main setting. This could be done for various reasons, like promotional purposes, or just because these schools make better models than the local ones, but I don’t know the exact reason behind this. Like in all the other examples I just mentioned, Myojo Gakuen Elementary School was also listed in the ending credits.

This shot from the opening shows the Taisho-roman Street, which I’ll come back to a little further down.

WD

Kumano Shrine again.

Given that the school is located someplace completely different, it’s not possible to retrace the exact path which Akane takes to get home. Instead the anime just shows different scenes from all around town. The railway crossing is located only a bit north of Kawagoeshi Station.

Also the order in which these backgrounds are shown during Akane’s walk home don’t really make any sense in real life, but that’s just some very, very minor criticism from my side.

I was not able to get a shot from the other side of Akane’s apartment building, but you get the picture.

Hon-Kawagoe Station is one of the city’s three main stations.

Gusto is the family restaurant where the painfully awkward encounter between Akane’s and Kotarou’s families took place. This particular scene, together with the short moment during which Akane was unsure how to enter her new classroom for the first time, were my favorite moments of the episode, as they just felt so relatable. These two are still middle school kids after all, and yes, just about everything ones parents did was somehow automatically embarrassing at that age, especially starting a random conversation with the parents of the person you were interested in. The scene managed to perfectly showcase the awkwardness of these kids, almost not being able to greet or talk to each other, or getting iced coffee instead of melon soda just to appear more mature.

In the end, both of them did not manage to talk a lot with each other, but that might just be exactly what the show intended. The anime’s title “tsuki ga kirei” (the moon is beautiful) seems to stem from the famous phrase "tsuki ga kirei desu ne" (the moon is beautiful, isn’t it?), which was coined by one of Japan’s most important writers in modern literature, Natsume Soseki. In a popular anecdote about him, he translated “I love you” into “the moon is beautiful, isn’t it?”. He thought that the former was too blunt, and that two people don’t necessarily need direct words to communicate their feelings, since looking at the same thing while also feeling the same way about it is enough to convey their emotions. Beautiful, isn’t it? This doesn’t seem too farfetched given the themes of the show, and the fact that Kotarou seems to be well-read himself, quoting Osamu Dazai at the dinner table with ease. (Or it’s simply a very clever marketing campaign by the popular messaging app Line.)

A post office in Kawagoe. I don’t think it was explicitly explained or mentioned in the anime, but Kotarou seems to be handing in some kind of entry for a writing contest.

This shot of the entrance to the Kumano Shrine is especially interesting, since it seems like the anime actually used Google Street View as its template here. Aside from almost everything lining up perfectly, the top corner of the white house is especially odd (I took the liberty to mark the spot I mean). You often have these unclean stitches and cuts using Street View, which you can see in the top corner of the house here as well. But checking the building on my own pictures and on Street View from different angles and times, the house doesn’t actually have a deformation like that in real life. Nothing big or bad at all, it’s just interesting to see that anime studios might also be making good use of Street View.

The Taisho-roman Street is a broad granite street lined with buildings dating back to the Taisho Period, and leads straight to the Kurazukuri District.

WD

The bookshop which Kotarou enters at the end of the episode is actually a Japanese confectionary shop. The shop to the left is a little café.

WD

And that concludes this week’s edition of Anime vs. Real Life. I’m sure this is not the last you’ll see about Tsukigakirei and Kawagoe, as there are still a lot of famous landmarks, like the Kitain Temple or the city’s Bell Tower to see. I also prepared a little Google Map with all the locations shown in the anime, which I’ll try to update over the season.

What did you think of Tsukigakirei’s premier, and does Kawagoe seem like a place you’d like to visit? Sound off in the comments below!

---

You can follow Wilhelm on Twitter @Surwill.

0 notes

Text