#the archivist inquiries of the public

Text

I'm not sure if this will take off but I'd love to be indulged. I just read through an old reddit thread where butches talked about what colognes they wore and liked, and got to thinking that it'd be fun to do the same.

#the archivist inquiries of the public#tumblr polls#polls#poll time#also honestly i'm a bit of a frag head#if that's the proper term#which i didn't used to be but then i started enjoying more and more being a pleasant sensory experience for people#and also sometimes the reactions of the girls gays and theys is. ahem. quite nice too#also i love wearing cologne and doing it better than men#it's like dress up but it isn't but if it makes homophobes mad then yes it is and i'm flipping them off while i do it#archivist talk#personally in my collection i've got one million lucky valentino's born in roma and then TF's oud wood and i recently got another#called bohemian lime#lush's lord of misrule is also ... mamma mia#i've got others but these are just the ones of note based on how other people have reacted lol#also shout out to old spice deodorant in all its many scents except for the part where it gives me a rash hate that part#lesbianism#dykery#butch posting#butch#butch lesbian#butch dyke#a butch dyke wants to know man talk to me#thatbutcharchivist

276 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Our mission is to collect, preserve, and provide historical UFO materials to the general public and interested parties. With the accumulated data, we hope to assist with serious research endeavors and aid in an accurate chronicling of UFO/UAP history for present and future generations regardless of belief or non-belief in the subject."

Who: An assemblage of the leading U.S. UFO/UAP Historians and Archivists led by David Marler that includes: Jan Aldrich, Rod Dyke, Barry Greenwood, Dr. Mark Rodeghier, Rob Swiatek, and others.

What: The establishment of the largest historical archive dedicated to the preservation and centralization of UFO/UAP information in the United States.

Where: Physical archive to be based in the Albuquerque, New Mexico area.

Why: Our mission is to collect, preserve, and provide historical UFO materials to the general public and interested parties. With the accumulated data, we hope to assist with serious research endeavors and aid in an accurate chronicling of UFO/UAP history for present and future generations regardless of belief or non-belief in the subject.

Context: In recent years, there have been successive U.S. government disclosures acknowledging the UFO/UAP subject as a genuine phenomenon. Subsequently, multiple U.S. military, intelligence, and scientific agencies have started adopting programs to study the subject such as NASA and the AIAA. In addition, within the civilian sector, there has been an influx of new researchers into this field of inquiry. Many academics and scientists are included in this group.However, most of these parties do not have access to the vast array of historical materials and data sets in the hands of civilian U.S. UFO/UAP historians and researchers.

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Archivists are not librarians: Understanding the differences [Part 3]

Continued from part 2

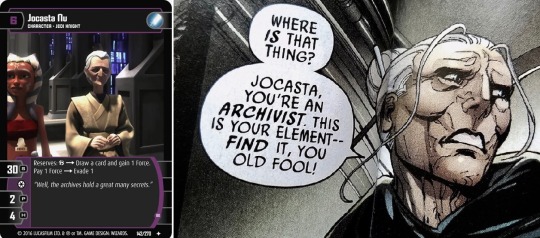

On the left, a trading card of Nu from the Star Wars Trading Game. On the right, Nu calls herself an archivist in the comic Star Wars: Darth Vader no. 9.

There are many important duties of an archivist, including preserving and providing access to original materials, involvement with records life cycle phases, records selection (i.e. archival appraisal), and arranging (then describing) collections of records. Archivists also work to protect records from theft and physical damage and work to ensure that digital records will be available when needed in the future. Of these duties, librarians also select their materials, try to protect them from physical damage and theft, and describe the materials. [4] However, the records that librarians work with on a day to day basis is nothing like those which archivists work with, and there are different systems of organization and arrangement. This is why it is always a problem when a librarian has control of an archives and claims they have the "right" way of organizing the records, inevitable messing it up for all those to follow, resulting in an archivist having to fix it later.

Reprinted from my Wading Through the Cultural Stacks WordPress blog. Originally published on Dec. 9, 2021.

These are not, of course, the only duties of an archivist. In fact, there are efforts by archivists to identify essential evidence of society, ensuring its availability for use, plan and direct publications, exhibitions, and outreach programs, make records accessible for use and assist patrons in locating information. Archivists are also concerned with records which have been deemed important enough to be kept for an extended period of time and sometimes are in charge of the archive itself. Managing records, along with transparency, ensuring the survival of provenance, keeping original order, and creating a coherent collection through well-informed and pro-active selection and collecting, are a vital part of being an archivist too. [5]

Librarians, on the other hand, can represent the library, providing patrons help with audiovisual and technology matters, engaging in reference services, assists other staff, develops grants, and selects (and maintains) audiovisual collections. Such librarians may also have strong computer, communication, and organizational skills, and enjoys learning. [6]

While some of these skills, like maintaining collections, organization, assisting staff, and various skills, would be helpful in an archival environment, there are other important skills which can't be gained by working in a library, where you are shelving and organizing books, DVDs, and CDs, for instance.

© 2022 Burkely Hermann. All rights reserved.

Continued in part 4

Notes

[4] For these two sentences, see "What's an Archivist?" on the NARA website, "What are archives?" page from the SAA, and "What Are Archives and How Do They Differ from Libraries?" page from the SAA.

[5] See "What are archives?" page from the SAA, "What are archives" from the University of Nottingham, and "What are Archives?" page from the National Museum of American History, Bob Clark saying that "our job as archivists is to be transparent & to make information accessible to the public. NARA is dedicated to the proposition of govt transparency through record-keeping & historical inquiry. There should be no archival issue that is too arcane for the public to understand," and the ICA page entitled "Who is an archivist?"

[6] This is pulling from some of the job description for the "Head of Technology and Patron Services (Full-time Librarian)" position on the ALA website.

#jocasta nu#star wars#star wars the clone wars#swtcw#comics#comic books#librarians#archivists#archival science#archival studies#archives#libraries#pop culture#reviews#definitions

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reed's Master Post

Hey there! I'm Reed aka Accidental Mistress (so named for the snz fic series of the same name, which I write). My DMs and asks are open, I just have a few boundaries. Please don't ask me to roleplay, as it's not something I'm comfortable with. Explicit sexual discussions also make me uncomfortable, being on the asexual spectrum (but some spiciness is ok!). I enjoy compliments, but please do not describe in detail about how my content gets you off. I'm open to requests and suggestions for wavs or writing, but I can't guarantee that I'll get to them. I'm not super comfy with large age gaps of like 10+ years, but you can still follow and interact with me! I just prefer those interactions remain friendly, i.e. pls don't flirt with me if I'm old enough to be your mom 😅 That's basically it. Don't be a creep or a jerk, and we should get along just fine.

Commission information can be found here.

My YouTube channel can be found here.

My master post for recordings on Tumblr is here.

My sneezy scientist chatbot Zayne can be found here.

Fic content, including Accidental Mistress, can be found under the cut on this post!

If you like what I do, please consider sending me some support so I can continue to create content for you!

Ko-fi

Accidental Mistress Content

Accidental Mistress is currently On Hiatus until further notice.

Character Profiles:

Noelle Violette and Oraion Leroux

Quinns Shaw

Oliver Dietrich

Mordecai Amadeus Catherwood

Setting Information:

World Overview

Fics:

In chronological order (story, not publication) with the earliest at the top. After each title is a short description of which characters are in it, and what kind of content.

SEASON ONE:

Accidental Mistress (N, Or, - M snz)

Experiment 239-158 (N, Or - M snz)

Enter Knight (N, Or, Q - M snz, SWH)

At the Silver Market (N, Or, Q - M snz, whump)

Stray Cat (Ol, Q - M, N-b snz)

Sugar We're Going Down (N, Or - M snz, NSFW)

Silver Metal (N, Or - M snz)

Dust in the Wind (N, Or, - M snz, F snz)

Catch Me (N, Or - M snz, whump)

Induce or Not? (N, Or - M snz)

Growing Up (N, Or - M snz, giant snz, destructive snz)

Take (N, Or - whump)

Soaked (N, Or - M snz, NSFW)

Cat's in the Cradle (Q, Ol - N-b snz)

Faith, Trust, and... (N, Or - M snz)

Cleaning House (M - M snz)

Library Magic (N, Or - M snz, NSFW)

Nothing Holding Me Back (N, Or - M snz)

One Look (Q, Ol - N-B snz)

Broken (N, Or - M snz, F snz, whump)

This Feeling (N, Or, Q, Ol - F snz, N-B snz, sickfic)

Good Things (N, Or - F snz, M snz, sickfic, NSFW)

Beneath the Mask (N, Or - M snz, non-human snz, sickfic)

Drabbles:

Safe in His Arms (Modern AU)

Handkerchief (not snz)

Playlist:

"Official" Accidental Mistress Playlist

Asks:

Emoji Ask 💬 N&O

Emoji Ask 🪶&💐 N&O

100 Questions N, O, Q, and Me

Emoji Ask 🕰️ N&O

Emoji Ask 📓 N and 🍵 O

EFF OC Inquiry 3 & 4 N&O

EFF OC Inquiry 2 & 9 O

OC Asks 10 & 13

OC Asks 4 & 9

OC Asks 16

Art:

Oraion Sketches

Oraion color piece

Sneezy Oraion

Realistic Concepts

confused-snz Fan Art

Cursebreaker Content

Set in the same world of Vibrahnem, Cursebreaker follows Jakob Steiner, a young Archivist, and his unusual companion Balthasar.

Character profiles:

Jakob and Balthasar

Fics:

To Have a Voice (J, B - M snz)

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Future That Belongs To Us

Hey, I actually got another fic done for jmart week! huzzah! (ngl wasn’t sure if that would happen, but I’m super glad I did.)

Anyways, this is for Day 7′s prompt, Growing Old Together

(tho it only sorta kinda fits it? It’s more about considering the possibility that Jon and Martin will get to grow old together than narrating them actually doing so. tbf when I started it I had a different, more ‘Forehead Kisses, direction in mind, but the fic was like ‘I’m going to go this way instead’ and I indulged it.)

@jonmartinweek

.

Martin doesn’t like hospitals. He doesn’t like being in them. He doesn’t like the smells, the noise. He especially doesn’t like how his heart plummets every time he hears some alert go off or a doctor with a clear destination in mind hurries past him. He reminds himself over and over again that Jon is fine. He’s stable. Heck, he’s breathing this time around. There’s absolutely no reason for the doctors to be rushing to his bedside. Certainly not because the five minutes Martin left him alone to go get something to eat from the canteen were the exact five minutes something happened—Jon’s heart stops and he’s dying or some would-be murderer finally made it past their security detail (or was allowed past, Martin still doesn’t quite trust the gruff men in uniforms despite their reassurances) and finished the job Martin himself started when he…

Martin buys a plastic-wrapped sandwich and a bottle of water without much fanfare. He keeps his head down and hopes no one notices or recognizes him. Not that many would. Though a photo of Jon’s face (usually his employee ID photo from the Institute, which frustrates Martin to no end. Even with it all being over, Jonah Magnus still looms over them.) has been printed alongside news articles or write-ups debating his character, making him irrevocably recognizable to the public, Martin, Basira, Melanie, and Georgie managed to avoid the same level of scrutiny. They’re not as interesting to the media news cycle as the Bringer of the Apocalypse himself apparently. For the most part. Usually.

Martin very much wishes it all would stop, and go away already. They changed the world back. That’s what matters. Not these endless inquiries into who Jon is. He doesn’t need them. Not now. Not when he’s trying to heal from…

“Mr. Blackwood! Mr. Blackwood!”

Martin cringes. He stops in his tracks. The lift doors are a meter ahead of him. He was so close. There’s always one, though. One persistent reporter who just won’t bugger off. He sighs, rolls his shoulders, closes the remaining distance, and presses the button for the lift anyway.

The reporter, one Martin doesn’t recognize (and he knows quite a few by now, almost every freaking time he leaves the hospital…), doesn’t take the obvious hint. He, huffing and puffing catches up with Martin, and scrambles to removed a notepad and pen from his pocket.

“Mr. Blackwood, care to comment on—?”

The lift, which Martin will forever be grateful for arrives. In a well-practiced maneuver Martin steps into it, blocks the reporter from following, and hits the door close button. Only after the lift, with only him in it, starts to move, does Martin let himself sag against its back wall.

The ride up to the floor where Jon’s room is is short. Too short. Martin tenses and mentally prepares himself right before the doors open. There won’t be any reporters up here. Though one may be able to slip in downstairs, where the hospital is still just a hospital, it’s far less likely here, in the wing they sectioned off to house the Archivist himself.

On the one hand, Martin is a bit relieved for the privacy granted by the government’s insistence of dedicating an entire area in the hospital to house Jon while he recuperates from being severed from the Eye. On the other, Martin’s ongoing anxiety that this is the day they’ll determine Jon Well Enough to ship off to some prison somewhere Martin can’t reach him surely isn’t good for his own health.

Not that there’s been any official decision there that Martin knows of. According to Basira, enough people in governmental positions were Avatars during the Eyepocalypse themselves, a call for criminalizing the role likely won’t happen. Probably.

Or, they could ship Jon off to one of the countries demanding to try him in their own courts. The last time Martin allowed himself a few minutes of watching a news broadcast, the Americans were still doggedly demanding as much.

The long and short of it is, there are a lot of thoughts that aren’t good for Martin’s health and all of them tend to clamor for his attention the second after the lift stops and before the door opens. The second that, once the doors do, the fear that Jon won’t be somewhere on their other side spikes to its zenith.

Arnie, the bored attendant assigned to checking everyone’s IDs once they step off the lift on this floor, grunts his usual greeting when he sees Martin. Martin allows himself to finally exhale. If Jon were no longer there, Arnie would be informing him as much.

He walks down the hallway, pointedly not looking at any of the officials who cut off their conversations when he passes. Martin wants to yell at them, demand they tell him why they’re there. They don’t need to be. Jon isn’t going to-to do anything! He can’t! Not anymore! And Martin and the others made sure the story that got out was that final decision to save their world over all the others was a unanimous one.

No one knows, has any reason to think, Jon would have done anything differently.

Martin pauses just outside Jon’s room. Jon wouldn’t have told them the truth himself. Of course he wouldn’t. Even he’s not that self-destructive.

The first thing Martin sees inside Jon’s hospital room are the nurses. The first thing he does is look for knives or guns in their hands. Takes a would-be murderer to know one, his voice mocks him from inside his head.

But no, one nurse is supporting Jon sit upright while the other gently wraps fresh bandages around his torso. Martin stands in the doorway and watches a long minute, but no hidden, sharp objects are slipped out of pockets to do harm. He approaches the bedside.

“Hey,” Martin’s hears the quiver in his own voice. He starts to reach out a tentative hand, but hesitates. He still loves Jon. Even after everything, he’s fairly certain he’s not capable of not loving Jon. The problem is Jon loving him back.

Because, ultimately, Martin is the one who got want he wanted. Their world was saved. The Entities were sent away, dooming all the others. Jon lost.

Jon’s hand, the one without an IV attached to its arm, wraps itself around Martin’s and gently squeezes. Martin looks up, and, for the first time without also facing off the intensity of a supernatural force, meets Jon’s unwavering gaze. It’s warm and brown and loving, and it occurs to Martin that he’s not sure he’s ever really seen Jon without the shadow of the Eye cast over him. That that’s something he can do now.

“I…” The words don’t come. The idea of Jon sending him away, never wanting to see him again, comes back. It’s so much worse because there is a Jon without the Eye now and, though Martin would do anything for his happiness, he may not want anything to do with Martin. Because the one time it really, truly mattered, Martin didn’t agree with him. He betrayed him. And, even if there is a Jon who gets to live to tomorrow, that Jon certainly doesn’t need Martin there with him and…

Jon’s hand pulls at Martin, and he lets it guide him to sitting on the edge of Jon’s bed.

“I still love you,” Jon whispers. “I want…” he pauses, looks away. “I don’t know how to…” He pulls his hands away, curling them into his blanket. “It’s okay if you leave. I can—I’ll be fine. I…”

“Do want to grow old with me?” The question blurts itself out of Martin before he can stop it. It’s not what he wanted to say, what he was slowly putting words together to say, but it’s the underlying inquiry beneath all of it.

Now that we have the future, do you want me in yours?

Jon blinks owlishly at him. His brows furrow together. “Of course I do, Martin, but I don’t want you to feel obligated to me. You’re free. You don’t have to…”

“I want to.” Martin pauses. “That is, if you’ll have me.” I almost killed you, after all. It would be perfectly reasonable if you never wanted to see me again.

There’s a long pause where Jon doesn’t say anything, but a contemplative look overtakes his face. “I think,” he finally admits, “we’re talking in circles.”

Martin considers the concept. “…yeah, you might be right there.” He chuckles. “I suppose we could figure it out as we go?”

“Together?”

Always. “Together.”

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

UWM Archives Intern Spotlight

Meet intern Maddi Brenner, third-year graduate student in the coordinated master’s degree program for Library and Information Science (MLIS) and Urban Studies (MS). She is in her final year of the program and plans to graduate in May 2022.

What is your area of study and research interests?

My research interests include urban history, public libraries, mental health & pedagogy, and anything archives.

Tell us about your thesis research and field work.

I am currently in the research phase of my thesis. I am analyzing the expansion of branch libraries and the implementation of a coordinated branch library system in the city of Milwaukee during the 1960s and 70s. I am reviewing the goals of the plan, its development and success post-construction. So far, I have noticed several discrepancies in funding and budget allocations, library location issues, council disagreements and neighborhood dynamics involved in library development.

I am also a fieldworker at Marquette University where I am processing the previously restricted collection of Joseph McCarthy (JRM). If you are interested in any random facts about the 1950s, I seem to have copious amounts of knowledge on the topic. One thing I am working on now is transferring relevant material related to and by Jean Kerr Minetti (the wife, and later widow, to Joe) from the JRM collection to its own open series. The documentation of women involved in the life of famous male figures is not often represented or even in its own narrative. The goal is to connect a sort of interrelatedness to the two series, but ultimately allow the individuals to stand alone in their interpretation.

It reminds me that although work has and is being done to address issues in collection arrangement and description, there is still more to do.

What draws you to the archives, special collections, or libraries profession?

I am really interested in how primary sources connect us to certain understandings of our history, especially through outreach, reference, and research.

What is your favorite collection within the archive -- or most interesting record/collection that you've come across?

I don't have a true favorite, but I do think it's cool that we hold the Society of American Archivists records. It is a massive collection with over 350 boxes and more than 3,500 digital files. Organization of the material has been re-arranged multiple times with new accessions up to 2018. I am not only fascinated by the history of archiving and collection management, but also how these records shaped issues of privilege, representation, and accessibility in the archives today.

What are you working on now for the archives?

Currently, I am working on research regarding reference and WTMJ film footage. The purpose of the project is to explore the frequency of reference requests and the value of preserving WTMJ footage. I will be analyzing both social media and e-mail as platforms crucial in access and outreach processes.

I also regularly coordinate archive transfers to other Wisconsin schools. It is fun to see what type of material is out there from other repositories and how impactful this program can be for researchers. Wisconsin is one of the only states that has this program, so that's exciting!

What's something surprising you've learned (about yourself as an archivist or about the profession) since you've started working at UWM Archives?

Honestly, I've learned that no two days are the same at the archives. There is so much going on and almost always a reference inquiry - whether big or small that I can dive into. There is a common misconception that archivists just sit around in an underground storage room all day and though, I surprisingly love being in the storage rooms, that's far from the truth. We wear many hats.

#Intern Spotlight#graduate students#UWM Archives#archivists#historians#library history#archives#libraries#UW-Milwaukee

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

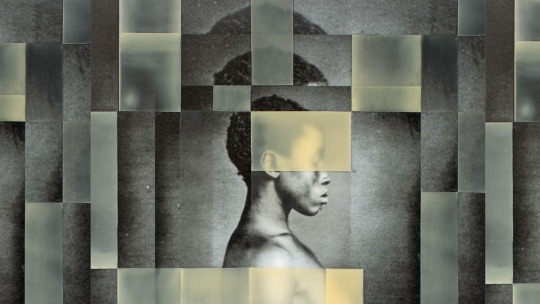

THE DARK UNDERSIDE OF REPRESENTATIONS OF SLAVERY

Will the Black body ever have the opportunity to rest in peace?

The photographs are about the size of a small hand. They’re wrapped in a leatherette case and framed in gold. From the background of one, the image of a Black woman’s body emerges. Her hair is plaited close to her head, and she is naked from the waist up. Her stare seems to penetrate the glass of the frame, peering into the eyes of the viewer. The paper label that accompanies her likeness reads: delia, country born of african parents, daughter of renty, congo. In another frame, her father stands before the camera, his collarbone prominent, and his temples peppered with gray and white hair. The label on his photo says: renty, congo, on plantation of b.f. taylor, columbia, s.c.

In 1850, when these images were captured, the subjects in the daguerreotypes were considered property. The bodies in the photographs had been shaped by hard labor on the grub plantation, where they’d spent their lives stooped over sandy soil, working approximately 1,200 acres of cotton and 200 of corn. Brought from the fields to a photography studio in Columbia, South Carolina, each person was photographed from different angles, in the hopes of finding photographic evidence of physical differences between the Black enslaved and the white masters who owned them. A daguerreotype took somewhere between three and 15 minutes of exposure time, and the end result was a detailed image imprinted on a small copper-plated sheet, covered with a thin coat of silver.

Louis Agassiz, a professor at Harvard, commissioned the portraits of Delia and Renty, along with those of other enslaved people, from the photographer Joseph T. Zealy. The daguerreotypes remained, all but forgotten, in the school’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology attic until an archivist found them in a storage drawer in 1976. Since then, these photos of Renty and his daughter Delia have been featured on conference programs, in presentations, and reproduced in books.

As photography has moved from the scientific novelty of Agassiz’s time to ubiquitous contemporary entertainment over the years, the art form has reflected society’s inequity. The rediscovery of the daguerreotypes and their use in revenue-generating materials in the present day have helped surface an ethical issue that has long accompanied images of Black people’s bodies: Their presentation and exploitation still, in many cases, outweigh individual ownership and autonomy.

While the provenance of the photos traces a line from a drawer at Harvard to a photographer in South Carolina, their story today also has roots in Norwich, Connecticut, home to Tamara Lanier, who claims to be the great-great-great-granddaughter of Renty. As a girl, Lanier’s mother told her about an ancestor named “Papa Renty.” She learned that he was a master of the Bible and that, as an act of defiance, he taught other enslaved people to read. According to the history passed down through her family, Renty got his hands on Noah Webster’s The Original Blue Back Speller, and after tending to crops in the fields, he would study the book at night.

Gillian B. White: Introducing the third chapter of “Inheritance”

Lanier would not start searching for the truth behind those stories until 2010, the year her mother died. She began a genealogical search for her ancestors. She also told an acquaintance, Richard Morrison, of her mother’s death and her own attempt at tracing her bloodline. Morrison, an amateur genealogist, took what Lanier told him and did some digging. He came up with a name: Renty Taylor. Morrison’s Ancestry.com search pulled up a photograph of Renty from 1850—one of Agassiz’s daguerreotypes. Further searches provided Lanier with information about Agassiz and Zealy and mentioned where she could find the original pictures: Harvard University. When she traveled to the school and viewed the images, Lanier was disappointed by their size, which resembled a deck of cards. There he was, the man who seemed larger than life in many of her mother’s stories, looking small and sad.

Seeing her ancestors in the archives at the university, Lanier felt the portraits were out of place. She believed that the images of Renty and Delia belonged to her. So on March 20, 2019, she filed a lawsuit against Harvard. In her lawsuit she alleges that the images of Renty and Delia are still working for the university, based on the licensing fees their images command. (In 2019, Harvard acknowledged that the images are not protected by copyright and that it charges only a $15 fee for a high-resolution scan.) Lanier requested that the university grant ownership of the daguerreotypes to her, pay her punitive damages, and turn over any profits associated with the portraits. “From slavery to where we are today, Black people’s property has been taken from them,” Lanier told me. “We are a disinherited people.”

Earlier this year, a court dismissed Lanier’s lawsuit, saying that “the law … does not confer a property interest to the subject of a photograph,” no matter the circumstances of its composition. Neither Harvard nor the judge presiding over the case disputed Lanier’s evidence that she was a direct descendant of Renty. Still, the court declared that Havard had the right to keep ownership of the photographs. Lanier has appealed the decision, and now the Massachusetts Supreme Court will weigh in. Oral arguments are scheduled for November 1.

Lanier’s case is about more than her personal interest in the photographs; rather, it has greater implications in a long-running reckoning. Agassiz used these photos of enslaved Africans, along with measurements of their cranium, as evidence of a theory known as polygenism, which was used by American proponents to justify slavery. He and other scientists believed Black people were created separately from white people, and their pseudoscientific inquiry was embedded into racist stereotypes in the bedrock of this country. To some historians, in keeping and curating images like these, Harvard is still celebrating the work of these practitioners and their discredited racial theories. (Harvard did not respond to requests for comment. In a previous statement, the university claimed the daguerreotypes were “powerful visual indictments of the horrific institution of slavery” and hoped the court ruling would make them “more accessible to a broader segment of the public.”)

The outcome of Lanier’s court case against Harvard will be legal commentary on whether the Black body ever has the opportunity to rest in peace, or whether present-day academic and entertainment priorities outweigh the rights of the Black deceased.

Whether she gets there or not depends on her long shot of an appeal. But her fight is an important front in a war over the ownership of images of Black bodies, one that is being waged on TikTok as well as in dusty archival drawers.

This technology spawns a series of questions: At a time when Black bodies are treated as teaching moments for the larger culture, are those whose bodies were broken—by the whip of an overseer or the bullet of a police officer—ever afforded the opportunity to rest in peace? This inquiry is the latest curious development in the ethically fraught conversation about Black bodies, ancestry, and ownership. There is a direct line between historical exploitation and the ongoing commercialization of and profiting from images of dead Black people, over which their descendants often have little control, few claims, and few rights.

America is still grappling with the limitations of freedom, and whether Renty and Delia will be released from the grips of the archives remains to be seen.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Inquisition

The Inquisition

The Hand of the King

"Our Eye Watches All"

An organization created for the purpose of gathering intelligence and conducting inquiries into the lives of public figures via espionage and sabotage.

Symbolism of Banner

Blue - for vigilance as they are an intelligence organization

White - for "purity"/justice, since their purpose is to ensure the wellbeing of the state The symbol on the flag is a mix of the letter I for inquisitio which means inquiry or investigation and an eye which is the symbol of its founder, Metis.

Structure

The employees of the Inquisition do not have their names stated or written down. Rather, they are referred to by their assigned designation. The format of an agent's designation is their unit letter followed by their agent number. Ex. Deimos is 5E or Epsilon five.

Within the bureau, agents will wear identifying bands to signal their rank. On the field, this protocol is waived.

Departments

Scryer

"It is said that many lived in fear during the reign of King Chronus, for the hundred eyes of Metis saw through both walls and hearts."

-Intelligence gathering and spy network. Designation "Sigma". Blue bands.

Archivist

"The records of the Inquisition go as far back as the warring states period to the genealogy of each noble house in Noemius. But history is still incomplete, and the origin of this strange land is yet unknown."

-Data managing and security. Designation "Alpha". Gold bands.

Executioner

"Their fear of death will choke them, right Athena?"

- Black ops. The Inquisition denies all evidence of their existence. Designation "Epsilon". Black bands.

Warden

"I did what I was ordered to... I'm sorry."

-The department that manages all the other ones. They are identified by their designation of "Delta" with the Lord Inquisitor being Delta 1. Directors wear red bands with the exception of the Lord Inquisitor who wears a white one.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

COVID-19 Update

Until further notice, all National Archives research rooms, the National Archives Museum, all museums in our Presidential Libraries system, and all public events at our facilities nationwide are closed to the public and/or cancelled.

We will continue to serve you remotely by responding to emailed records requests and History Hub inquiries. While we are closed, please explore our many online resources at www.archives.gov, view our online exhibits and educational resources, and join our Citizen Archivist Missions.

For more information, go to https://www.archives.gov/coronavirus

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

{ @restitutiopax }

Big optics sparkle as he peers at every angle, curious and bright. "Huh! Where I'm from, our EM Field is capable of something similar, even if stricture on a textural level. How curious."

Starscream’s wings hike up for a moment before relaxing low, almost to rest position. Orion’s curiosity is charming, and a welcome change from how most mecha react to him.

Out of his own need to explore, though, the Seeker gradually presses outwards with his EMF, keeping it at a surface level [greeting/inquiry] as it skims against the Archivist.

“You’ll find most from... my... area of the whatever use their fields as an extension of themselves, as a sort of ephemeral manifestation of the emotional subsystem. It’s considered polite not to broadcast your field too far in public, though in some cases someone with high clearance or a significant function-- again, a peacekeeper or a policemech or such-- can push their field out broad and forcefully to override other nearby signals and calm a situation. And medical tech crew usually have dampeners installed, or otherwise strictly control their fields when working... Oh, and I know a mech who’s EMF is so weak you’d never know he even has one, despite being forged.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

Departures

I am currently travelling to London to visit two archives, The London Metropolitan Archives, and The Black Cultural Archives. These archives house documents and materials related to the two organisations, Greater London Council and The Commission for Racial Equality. At this exact moment, I am sitting next to my partner on a British Airways flight to London. I am not the type to write at a whim yet as someone who is truly terrified of flying, I find myself needing the distraction after a particularly bumpy taxi.

Besides working at the Vogue Archives and the V&A archives this will be the first time I attend an archive with a personal agenda, with a personal sense of intrigue and inquiry. I am unsure as to what I will find but I have a vague idea of what questions I would like to answer. At what point did these organisations feel the need the communicate ideas such as anti-racism to the public? How did they decide on the iconography and visuals? How soon after such decisions did they decide to bring in advertising agency Saatchi & Saatchi? How did they define the term anti-racism? Municipal anti-racism?

Reading the work of scholars and activists that came before me, that cleared the ground back in the 70s and 80s I feel so proud and yet disconnected from the tradition and legacy. I am also trying to find out where I fit in this conversation as someone who comes from a different colonial history and whose parents arrived in the UK just as the work on anti-racism had begun on a municipal level.

I wonder what the material will look like, how will it be presented to me? I sheepishly asked the archivist if two weeks felt like enough time to get through the material. “It depends on what you need really, but two weeks sounds about right.” I read through the rules sent to me, making sure to take notes on what I could take in and how I would go about recording the material. What would the room look like? Would there be other researchers keen to have a chat after almost two years of social isolation?

A few days prior I spoke with my supervisor, and I asked if she had any advice on an archival visit. Again, the question felt clumsy. She reassured me that it is difficult to know until one is in front of the material, but that I should try and remain focused on the task at hand. “It can be difficult to know when to stop looking, you always think the perfect piece is in the next box, but when time is tight it is often the case that you need to stop.” She told me of past students who had visited the archives of artists and had lost themselves in the love letters and notes. The sense of always being behind your schedule whilst doing a Ph.D. is overwhelming. I took her advice seriously.

This visit itself was organised rather late. During my first year, I was adamant I didn’t need to go to an archive. I didn’t think it was important to understand the intentionality behind these images. I felt that I knew what they were trying to achieve. More than that I felt that my research questions were focused on the images themselves. I wanted to give them agency beyond what the organisations and the advertising agency wanted. I wanted to interrogate the images as individuals and ask them what they thought they were doing. Looking back this may have been a stubborn position to take or one that would not yield enough work to justify a Ph.D. qualification. I kept saying to colleagues that I am not a historian.

I had finished reading Saadiya Hartman’s book Lose Your Mother before returning to Copenhagen. I had also read Wayward Lives Beautiful Experiments before even applying for the Ph.D. A book so profound and moving that I had to stop reading and return to a year after I began. What I loved so much about Lose Your Mother was her sense of frustration and how clearly she articulated it. The landscape became her archive as she scanned various locations in Ghana that represented the trauma and pain from the Transatlantic slave trade. She made the archive into what she wanted, blending personal stories with historical findings, and was honest when she came across dead ends. After a truly miserable summer of covid infections and isolation, this book brought me back to life. I have not stopped gushing about it. I am not sure exactly how much this book had an impact on my position regarding an archival visit but it gave me the optimism to embrace the sometimes negative and frustrated feelings.

We have begun our descent into London Heathrow, my partner and I pointing out the different parts of the city. Stratford, The O2 arena, The Royal Albert Hall. I begin my work on Monday and am filled with a mix of excitement and intrigue. Well, I am actually filled with anxiety, landing brings me no tranquillity. I am hoping to document my trip and write some more reflexive pieces like this one. For now, I wait for the bump of the wheels on the tarmac to truly feel relaxed and safe. I begin work on Monday.

0 notes

Text

Before Rhode Island Built Its State House, a Racist Mob Destroyed the Community That Lived There

https://sciencespies.com/history/before-rhode-island-built-its-state-house-a-racist-mob-destroyed-the-community-that-lived-there/

Before Rhode Island Built Its State House, a Racist Mob Destroyed the Community That Lived There

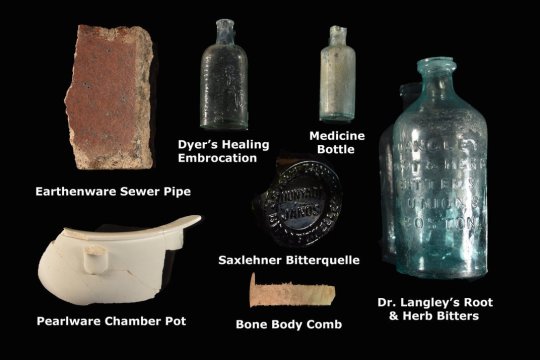

Photo of 1982 excavation at North Shore site

Snowtown Project

On a pair of folding tables in the basement of the Public Archaeology Laboratory (PAL) in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, four metal trays display an unusual assemblage of artifacts. Humble ceramic tableware. Iron padlocks. Dominoes carved out of bone. A cut-glass tumbler. A diminutive bottle of French hair tonic. The headless body of a porcelain doll. A Spanish coin. A redware pot with drizzles of blue, black, yellow and green paint frozen in time on its sides.

These are the vestiges of Snowtown, a poor but vibrant mixed-race community that was once part of the state’s capital city, Providence. Moreover, it stood on the grounds where the state’s imposing capitol building now sits. Though no visible traces of the neighborhood remain, its history—including a deadly mob attack in 1831—is now being resurrected by the Snowtown Project.

The initiative began as an outgrowth of a Rhode Island State House Restoration Society subcommittee that was tasked with telling lesser-known stories about the capitol building and its grounds. Marisa Brown, who chairs the subcommittee and is an adjunct lecturer at Brown University’s John Nicholas Brown Center for Public Humanities and Cultural Heritage, says, “There’s a disconnect between the accuracy of what happened in the past and what our landscapes tell us. There are just too many places that we have lost.”

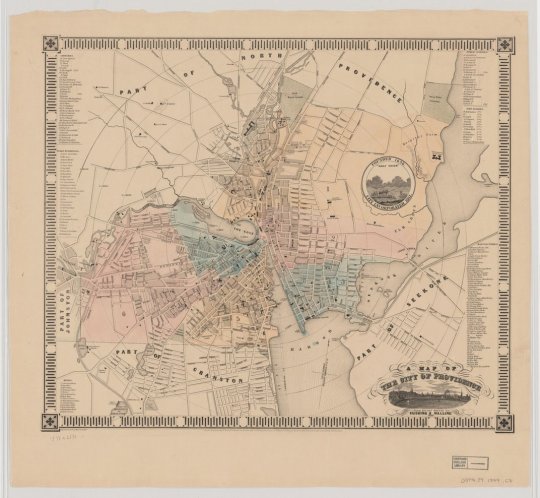

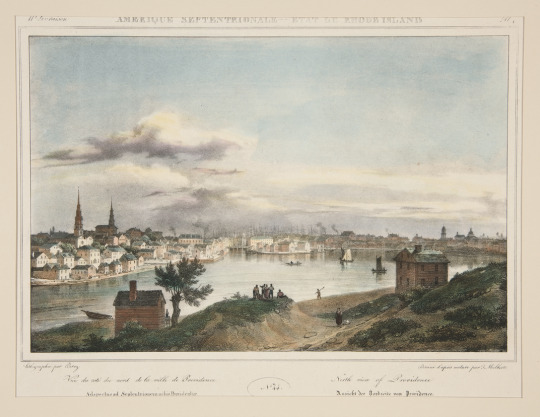

1849 map of Providence, Rhode Island. Snowtown stood just north of the Cove, near the center of the map.

Harvard University, Harvard Map Collection

In 2019, the subcommittee emailed colleagues to gauge interest in researching Snowtown. Over the course of three meetings, a handful of people blossomed first into a group of 30 and now a cohort of more than 100 historians, archivists, archaeologists, teachers, storytellers, artists and community members.

After the American Revolution, Rhode Island experienced rapid population growth driven by the international “Triangle Trade”—of enslaved people, sugar products and spirits—through the port of Providence. The state’s distilleries had a special knack for turning imported sugarcane and molasses from the West Indies into rum, which was traded for enslaved labor. But by the 1830s, as the population surpassed 16,000, the manufacturing of textiles, jewelry and silverware had supplanted the merchant trade as the city’s primary economic driver.

The state’s Gradual Emancipation Act of 1784 had allowed children born to enslaved women to be freed once they reached adulthood. Within decades, a new population of free Black people had emerged, but they, along with indentured servants, Indigenous people, immigrants and impoverished white people, were pushed into marginalized communities. Many of these groups were denied the opportunity to work in the burgeoning manufacturing industry.

They lived in places like Snowtown, a settlement of shabby homes and businesses with little in the way of conveniences. It was home to between two and three dozen households, but the population ebbed and flowed. Some residents toiled as domestic servants in the homes of Providence’s elite, or in trades like carpentry and sewing. The most successful owned small businesses or boarding houses. Even for the latter, life in Snowtown was difficult.

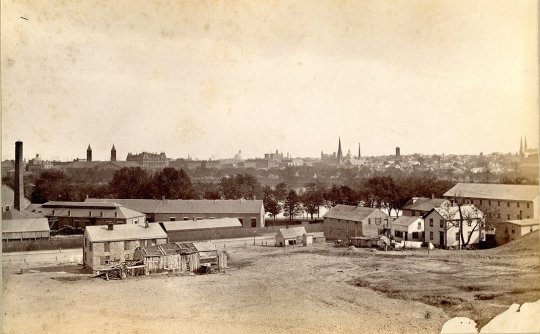

View south from Smith Hill with downtown Providence in the background and residential buildings in the foreground, 1885

Providence Public Library under CC BY-SA 4.0

Pollution in Providence made conditions even worse. The Great Salt Cove, a tidal estuary that had been significant to local Indigenous tribes, just below the sandy bluff where Snowtown was located, became a dumping ground for sewage and industrial waste. Real estate in the village was undesirable; rents were cheap; and “disreputable” businesses aimed at sailors coming through port—brothels, saloons and dance halls—proliferated.

In 1831, sailors newly arrived from Sweden aboard the steamer Lion started a brawl at a tavern in Olney’s Lane, a neighborhood adjacent to Snowtown that was also home to an assemblage of non-white communities. According to an account in the Rhode Island American and Gazette, the sailors gathered reinforcements and attacked a home occupied by “blacks of a dissolute character.” Two Black men fired on the sailors, slaying one and wounding three. The white mob, shouting “Kill every negro you can!” advanced uphill into Snowtown, where the shooter was believed to had fled.

Over the course of four days, 18 buildings in Snowtown and Olney’s Lane were damaged or destroyed. Eventually, the state militia, ill-equipped to handle the scene, fired to disperse the mob, killing four.

Though residents rebuilt, by the late 1800s, Snowtown and its Black residents had been displaced by industrial progress. Rhode Island had grown into the wealthiest state per capita. In part as a monument to its prestige, the state commissioned renowned architects McKim, Mead & White, of Pennsylvania Station and New York Public Library renown, to design a massive State House on the bluff above Great Salt Cove. Construction was completed in 1904.

1828 lithograph showing view looking south from Smith’s Hill, with some of the buildings along the north shore of the Cove in the mid-ground

Yale University Art Gallery

Today, all traces of Snowtown and its sister communities are obscured beneath railroad tracks, a small park commemorating state founder Roger Williams, and the ornate neoclassical capitol and its rolling green lawns.

Still, says Chris Roberts, a Snowtown Project researcher and an assistant professor at Rhode Island School of Design, “If you’re researching slavery in Providence, Snowtown comes up. If you’re looking at the history of women in Providence, Snowtown shows up. If you’re looking into the city as a commercial hub, it comes up. Snowtown is a character in so many different histories of the city.”

Uncovering Snowtown has not been without challenges. For starters, the record is incomplete. Census data, for example, documents the names of heads of households, with only numbers to indicate women and children. “We often have to grapple with these archival silences,” says Jerrad Pacatte, a Snowtown research committee member and a PhD candidate at Rutgers University. “These were people who were not considered worthy of being counted.”

Physical evidence of entrepreneurship, creativity and personal care persist in a collection of about 32,000 artifacts. The artifacts were unearthed, and about 30 percent cataloged, in the early 1980s, when the Federal Railroad Administration undertook rail-improvement projects in the Northeast, including in Providence.

Assorted artifacts found during digs in the Snowtown neighborhood

Snowtown Project

According to Heather Olson, the lab manager for PAL and a Snowtown Project researcher, the materials were then archived and shipped to what is now the Rhode Island Historical Preservation and Heritage Commission. They remained there for 35 years, largely untouched, save for a few inquiries related to doctoral theses and a small exhibit in 1988; those items subsequently went missing.

The remaining artifacts were turned over to the PAL in 2013. The organization has digitally cataloged the entire collection—everything from writing slate and pencils to crucibles for metal working, woodworking tools and children’s toys. (Some of these digitized objects will hopefully be publicized online when the project is completed.)

Kitchen items are the most common, and they reflect a curious intermingling of status. Alongside unadorned plates and servingware, the collection includes pricey Blue Willow transferware, Chinese porcelain and an 18th-century feldspathic stoneware teapot. Olson says, “I don’t know if these arrived as clean fill from somewhere, if it was something bought secondhand, or if this was something that had been given to the people”—for example, to a domestic servant employed by the city’s wealthy.

Other artifacts give clues about the residents’ health. The large number of bottles for digestive tonics, for instance, speaks to the contaminated nature of the water supply. For Olson, the collection is an opportunity to examine a hidden history. “What can you identify? What can you say about people who were, for the most part, invisible?” she says.

If the complex work of the Snowtown Project shines a spotlight on a single truth, it’s that “written history belongs to the winners,” says Joanne Pope Melish, a retired University of Kentucky historian; the author of Disowning Slavery: Gradual Emancipation and “Race” in New England, 1780–1860; and co-chair of the project’s research committee.

“History, and the doing and the telling of history, is a product of the politics of the moment in which the telling of the story is happening and of the moment in which the story took place,” she explains.

Rooftop view of Providence from City Hall, looking north over railroad tracks, Providence Cove, and buildings in the distance, circa 1880. Snowtown is visible in the distance at top left.

Providence Public Library under CC BY-SA 4.0

White supremacy was alive and well above the Mason-Dixon Line. Newly freed African American people traded the physical oppression of enslavement for the societal oppression of classism and historical effacement. Mentions of Snowtown are infrequent in contemporaneous newspapers. They begin to reemerge only in the 1960s, as the civil rights movement brought the neighborhood back into public consciousness.

This awareness has accelerated over the past decade, in direct response to the Black Lives Matter movement. Modern media retellings of vanished histories have also helped, such as the episode of HBO’s “Watchmen” that dramatized the events of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre.

Before Tulsa, according to Pope Melish, white mobs attacked northern Black neighborhoods 144 times between 1820 and 1850. While the Oklahoma attack was far deadlier, these assaults present two sides of the same coin. Pope Melish says, “It parallels the impossibility of being a ‘perfect’ enslaved person or free person of color. If you’re poor, you’re disgusting. If you’re successful, you’re uppity. Both cause hostility.”

Traci Picard, a public historian who co-chairs the Snowtown Project research team, has been working to unearth personal histories. She has sifted through thousands of seemingly mundane materials, including writs and warrants—an early version of small-claims court. “Every single thing is built by someone,” she says. “I don’t mean designed by someone, or who gets the credit for building it. Every single block, every single brick, every single building—we’re surrounded by people’s lives and experiences and stories.”

Planning is underway to present those stories in an exhibition at the State House, as well as a digital publication featuring maps, photos and documents. Snowtown History Walks debuted in June, and public art installations and signage for self-guided tours are also being discussed.

Playwright and actor Sylvia Ann Soares, a programs team member and a Cape Verdean descendant of the Portuguese slave trade in Providence, is working on a Snowtown-themed play set to premiere next year. She believes that involvement of artists in the earliest stages of the project is integral to its retelling. “The results will be richer,” she says. “Many people will not read a scientific journal or go to a talk, but if it’s dramatic, if there’s some music, some songs of that era, it brings it alive.”

Soares adds, “I intend to [use the play to] speak out as an inspiration for advocacy against present-day injustice.”

For Pacatte, it’s also an opportunity to broaden our understanding of a part of American evolution that has been swept under the carpet of white history. “Snowtown is a microcosm for the very messy and prolonged process of emancipation that people in the North experienced before the Civil War,” he says. “It’s the story of African Americans [in the U.S.]: They were resilient and kept rebuilding their lives.”

African American History

American History

Death

Digitization

Exhibitions

Indigenous Peoples

Industrial Revolution

Maps

Race and Ethnicity

Racism

Slavery

#History

0 notes

Text

Week 1 Presentation

aim: engage with curatorial concepts to investigate modes of representation, collection, display and distribution.

key historical developments 19th 20th century museum practices + cultural and ethical concerns for both community and of institutional context.

public presentation of creative works were I take of the role of curator

written proposal and visual submission

Workblog

Curatorial Proposal

Independent Research// individuate project for your interests and disciplinary/studio inquiry

museums.

(collect conserve display educate stimulate research offer experience )

Collections

( The art or process of collecting and the accumulation of objects, things, artefacts, consumables, resources. Undertaken by institutions on behalf of the public, research collections, private collections, hobby and specialist hobby collections. )

curating.

(The curator selects items for exhibition and develops relationships in support of a theme or subject also considers the agency, ethics and responsibilities that comes with the terrain of curating. )

Professional practices

( Conditioning reports, collections management, conservation, archivists, outreach and education. )

Bennett (The Birth of the Museum, 90) states of public rights:

1. ‘That museums are equally open and accessible to all.’

2. ‘[Museums] should adequately represent the cultures and values of different sections of the public.’

these stated principles are ‘a rhetoric often not met by the political rationality embodied in the actual modes of their function.’

How exactly is the representation of diverse cultures and community groups displayed in a museum?

modes of display -understanding via framing display of function giving context and meaning

architectural spaces

to be experienced but they also conditioned experience

narratives ; collection can reflect interest of induvial or the museum

decolonize this space https://decolonizethisplace.org/

queer the collection https://vanabbemuseum.nl/en/collection/queering/about/

https://exhibits.law.harvard.edu/queering-the-collection

Types of museums i may be interested in investigating and further researching;

portrait, sound and vision, tattoo,space ,hair,botanic,

0 notes

Text

week1

Lecture:

Key historical development of 19th-20th

Part1 museums 1-3 collect&conserve; display; educate; stimulate; offer expirence

Part2 Collections 4-6 the art or process of collecting objects

Part 3 Curating 6-8 elect items for exhibition

Part4. Professional practices 9-11 behind the scenes conditioning report, management, archivists, conversation…

Museum of nature and hunt Venus; Position of things

Deep Cuts: A response to a short run

www.pantograph.punch.com

Virtual museums exist in electric form on the internet , they rerun dependent upon collections while also bring benefits.

Assessment:

-blog

-curatorail proposal

Week1 reading the history of museums

The thinking within the museum which drives exhibition making is often motivated by funding, is politicized and ideological.

How is the representation of diverse cultures and community groups displayed in a museum?

Models of display:

What is encountered in a display is understood by how it is framed. This are models of display function, they themselves provide context and meaning. Whom determines these?

Prevailing traditions:

The white cube and the black box are modes of display: architectural spaces in which exhibitions are presented to be experienced. But these space also condition experience. These models have also shaped prevailing traditions on the history of art and exhibition design practices.

Independent tasks: Museums: big, small, practical, virtual, real objects, intangible items…

Assignment:

1.Three types of museums I feel interested:

<1>Steampunk HQ:

1.What do they do:

Steampunk HQ is an art collaboration and gallery in the historic Victorian precinct of Oamaru, New Zealand. It celebrates its own industrial take on steampunk via an array of contraptions and sculptures, complemented by audio-visual installations in two darkened rooms and part of the buildings basement.

2.What’s their collection:

Their collection is about steampunk artwork and sculptures. The gallery presents a theme of a dark post-apocalyptic vision of a future "as it might have been". Contraptions and bizarre machinery featuring heavy use of copper, gears, pipes, gas cylinders, as well as an ensemble of skeletal sculptures are lit by flickering lights and accompanied by projectors and background sounds. The two large darkened rooms and part of the basement of the building house a variety of old industrial and medical machines remade into "aetheric" devices. The exhibits include some large machines, such as a steam tractor, periodically emitting steam, and a boat with a grim reaper.

<2>Cancún Underwater Museum:

Museo Subacuático de Arte, known as MUSA, in Cancun, Mexico

1.What do they do:

Cancun underwater museum is an initiative that wished to divert a large group of ocean divers disrupting the balance of underwater fauna in the Caribbean coastline. The director of the Cancun National Marine Park -Jaime Gonzalez Canto wished to provide an alternative to preserving these disrupted coral reefs. By bringing British Sculptor Jason De Caires Taylor and a group of Mexican artists on board, nearly 500 statues with pH neutral marine concrete were anchored into the ocean.

The Cancun underwater museum also known as the ‘Museum of submerged Art’ has nearly three such galleries that showcase a variety of themes reflecting the subtle nuances of the fishing community.The idea of maintaining a much-needed balance between nature and mankind is reinforced through its solitary human sculptures.You can view these underwater installations in the National Marine Park of Cancun situated in the islands of Isla Mujeres and Punta Nizuc. They are due to expand to another 10 galleries adding nearly 1200 statues to its wondrous collection.

2.What’s their collection:

The Cancun underwater museum holds an interesting blend of statues ranging from themes such as capital greed to simplistic holistic living of the fishermen community. You would find sculptures ranging from simple objects such as time bombs to world-renowned art forms such as the ‘Vicissitude’ in close quarters. The ‘Vicissitude’ showcases people standing in a circle looking at the sky praying for hope. Other Installations such as that of a group of men, with their heads buried in the sand, showcase realistic capitalistic burnout.

<3>Icelandic Phallological Museum: located in Reykjavik, Iceland

1.What do they do:

The Icelandic Phallological Museum is the largest museum in the world to contain a collection of phallic specimens belonging to all the various types of mammal found in a single country. Phallology is an ancient science which, until recent years, has received very little attention in Iceland, except as a borderline field of study in other academic disciplines such as history, art, psychology, literature and other artistic fields like music and ballet. Now, thanks to The Icelandic Phallological Museum, it is finally possible for individuals to undertake serious study into the field of phallology in an organized, scientific fashion.

2.What’s their collection:

The Icelandic Phallological Museum contains a collection of more than two hundred and fifteen penises and penile parts belonging to almost all the land and sea mammals that can be found in Iceland. Visitors to the museum will encounter fifty six specimens belonging to seventeen different kinds of whale, one specimen taken from a rogue polar bear, thirty-six specimens belonging to seven different kinds of seal and walrus, and one hundred and fifteen specimens originating from twenty different kinds of land mammal: all in all, a total of two hundred and nine specimens belonging to forty six different kinds of mammal, including specimens from Homo Sapiens. It should be noted that the museum h as also been fortunate enough to receive legally-certified gift tokens for four specimens belonging to Homo Sapiens.

2. Drawing Maps:

1. Guided by my intuition:

The main elements that lead me to visit my first five displays are “Color” and “Size”. Either the red/green Kirkcaldie&Stain’s uniform or the giant saddle for elephants is huge and conspicuous. They are outstanding and easily attracting your attention. Then I get back to the regular routine and have a look at the displays on the very left wall. At the end of the left part, there is a very interesting exhibition for Wellington’s famous cat. After that, when you are leaving the cat exhibition, right under the stairs, there is a series of royal crowns which are extremely shining. So I didn’t pay attention to other displays on the other side of the wall and went to see these crowns.

2.Following the museum’s instruction:

I just followed the footprint guidance on the floor and visit them in normal order.

3. Reading Review:

<1>Etymology:

Museum: from ancient Greek

meaning: seat of the Muses

Function: a philosophical institution or a place of contemplation

Ancient museum was more like a prototype university for philosophical discussion rather than to preserve heritage. It revived in 15th-century Europe and mainly conveyed the concept of comprehensiveness. Till 17th century, the word started to represent collections of curiosities.

The reason was because the Oxford Uni received Ashmolean’s property and settled them in a building open to the public. Besides, with the process of founding the British Museum, the idea of an institution called a museum for preserving and showing collections to the public was gradually well established in 18th.

Since the interaction between the museum and the society becomes more and more important, the emphasis on the building itself became less dominant. There are new forms of museum such as eco museums and virtual museums.

<2>

The development of museology and the application of museography isn’t satisfying because:

Personnel were trained to a certain collection and lack understanding of considering the museum as a whole.

Lack of mature disciplines and techniques for the management of museum and may learn something improper from other fields.

Lacking of clear purpose and identity

The apprenticeship give little space for new and creative ideas

“The origins of the twin concepts of preservation and interpretation, which form the basis of the museum, lie in the human propensity to acquire and inquire.” From the Paleolithic burials, the cave art shows the evidence of inquiry and communication through their collections.

In the ancient, “the collection of things that might have religious, magical, economic, aesthetic, or historical value or that simply might be curiosities was undertaken worldwide by groups as well as by individuals.”

The essay talked about in Asia, one of the main reason is because of the veneration of the past, and I think there is another strong motivation, to demonstrate the dignity of status, It’s more like a symbol of power.

The emperor of Qin Dynasty asked to build his mausoleum for around 40 years. It contains an estimated 8,000 lifelike clay soldiers, as well as mass graves and evidence of a brutal power grab. Besides, All the pottery warriors are facing east. According to historical records, the original ruling area of Qin was in the west and the other states were in the east. Qin Shi Huang always planned to unify all states, so the soldiers and horses facing east might confirm his determination for unification.

In Europe, the maritime links through the Mediterranean ports promoted the movement of antiquities and the developing trade in them, which also accelerated cultural conversation and interaction leading to the European Renaissance. Outstanding among the collections was that formed by Cosimo de' Medici in Florence, in 17th century his collections have been bequeathed to the state and the public want to have a look, thus palaces holding such collections were open to visitors and were listed in the tourist guides of the period.

In Europe, “The developing interest in human as well as natural history in the 16th century led to the creation of specialized collections.” Professional terms and books were created to distinguish different types of museums. For example, Samuel von’s view reflects a spirit of system and rational inquiry that had begun to emerge in Europe. People gradually have the awareness of early concepts of museology, including classification, care of a collection, and the identification of potential sources from which collections might be developed.

The learned society’s promoted the establishment of more scientific and cultural organizations the Royal Society in London (1660) and the Academy of Sciences in Paris (1666). “By the turn of the century, organizations covering other subject areas were being established, among them the Society of Antiquaries of London (1707), and learned societies were also appearing in provincial towns. This was the beginning of a movement that, through the collections formed and the promotion of their subjects, contributed much to the formation of museums in the modern meaning of the term. A history of modern museums begins in the next section. ”

<3>Toward the modern museum: from private collection to public exhibition

From the past, most of the collections were owned by prominent individuals with huge wealth or noble social status; but over time, the spirits of inquiry and desire of appreciating and learning added other meaning and purpose to collection. A wider group of participators and collectors join in and feel concerned with enjoyment and study and the advancement of knowledge or the continuity of their collections. If it’s hard to be achieved in the family unit, it’s better to hand them into the corporate unit or the government.“ if knowledge were to have lasting significance, it had to be transmitted in the public domain.”

17th century

the world's first university museum: the Ashmolean Museum

The Ashmolean came into existence in 1682, when the wealthy antiquary Elias Ashmole gifted his collection to the University. It opened as Britain's first public museum, and the world's first university museum, in 1683.

The Ashmolean is Oxford University's Museum of Art and Archaeology. Opened in 1683, it is the oldest public museum in the UK. The museum has incredibly rich and diverse collections from around the globe, ranging from Egyptian mummies and classical sculpture to the Pre-Raphaelites and modern art.

18th century:

Background: “The 18th century saw the flowering of the Enlightenment and the encyclopaedic spirit, as well as a growing taste for the exotic. These influences, encouraged by increasing world exploration, by trade centred on northwestern Europe, and by developing industrialization, are evident in the opening of two of Europe's outstanding museums, the British Museum, in London, in 1759 and the Louvre, in Paris, in 1793. “

“ The British Museum was formed as the result of the government's acceptance of responsibility to preserve and maintain three collections "not only for the inspection and entertainment of the learned and the curious, but for the general use and benefit of the public.”

0 notes

Text

IL CINEMA RITROVATO 2017: THE ART OF DECAY, THE PERSISTENCE OF FILM

Dawson City: Frozen Time (Bill Morrison)

By Tara Judah

Introducing Decasia (2002) at Il Cinema Ritrovato, Bill Morrison talked about his requests for access for use of decaying nitrate film. Not all archives were forthcoming with the material. Perhaps it is the persistence of imperfection that breeds protective behaviour in archivists. But, what Morrison affected, once access was granted, is a glorious symphony of the persistence of history. The physical, indexical trace, though smudged, blurred, rotting and occasionally absent, never stops trying to prove itself. What was filmed may appear altered, but even a glimpse of a single frame is ontological proof in perpetuity.

Celebrating fragments and embracing the journey as well as the fact, Morrison makes the case for decay: every bit as important and beautiful as the thing it attacks. The quality of nitrate film, now, itself an historical artifact, must also be seen and even understood as art.

More urgently, it draws attention to the artifice of production in a new way, as the material itself is always achingly present; it refuses to adhere to the confines of the frame, affording it with a physically manifest, amorphous omnipotence; and, the fragility of the medium reminds us of the instability of human creation, and the finite nature of our species.

Beyond formal inquiry lies playful and lyrical entertainment: a man boxes a decaying blob, air shuttle shaped carriers on a carousel blast into frame out of a thrumming void, and young boys jump up and down on a moving splotch. There are moments, too, when the decay looks like something – a sort of phantom, haunting the image, insisting on the past.

The inescapable nature of history and our endless fascination with our own sordid stories further led Morrison to making the feature-length documentary, Dawson City: Frozen Time (2016), which also screened at the festival this year. Working first with material from the Dawson City Film Find (1978), using some 124 of the 533 newly discovered reels, Morrison’s use of the footage is so expressive that it breathes new life into lost voices of the silent film era. The documentary tells a much grander and more complete narrative, too, about place, people and their complex history with film.

Flooding to Dawson in the hopes of striking it rich, prospectors turned the First Nation hunting ground into a city where gold and gambling were king. From its very early days, film played its part in both capturing the city’s rapid development and entertaining its new inhabitants. The disregard for film history – studios couldn’t be bothered to cover the costs of having the films sent back and, as the official end-of-the-line for exhibition, many prints were simply thrown in the river – mirrors the voracious, uncaring pace of capitalist enterprise and white settlement that also took place. Morrison reveals the uneasy history with a deft hand, letting primary evidence – static and moving – do the talking.

Dawson City is a multilayered story that really thinks about how time, history and artifact affects the memories of private and public lives. Morrison shows us how history refused to be silenced – the nitrate film that was buried constantly peeking out of the permafrost, begging to be (re)discovered. He lets us uncover, too, through the newly found silent film footage, how values and attitudes of the time played out in moving images, just as they do today. Carefully curated snippets of well-trodden visual tropes and storytelling devices that are ingrained in our cultural memory make the argument all the more compelling. He makes his own discoveries, also, through personal interest (namely baseball) and by the ever-changing significance of historical information – a Trump anecdote now plays its part in the film’s marketing, but only became relevant as the political climate changed over the duration of his working on the film.

So much more than just a lesson in Dawson City’s own history, and extending further still than the bounds of film history, Morrison’s approach to archive film offers us an experience of the past that is unwaveringly contemporary. There is, in my opinion, no greater way to consider how film history has relevance today than through the incredible archive works of art that Morrison has crafted.

Source

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Semester

I began the semester wondering about the origins of popularized historical narratives and the implications of holding onto them for generations. It seems that history is a product that is sold to many of us unsuspectingly. As people of the present, we look towards those before us for information to help us better understand our contemporary climate. Where we choose to look through for history can become a suspicious venture, as many times, communities and organizations, like museums or memorial foundations, share their curated narratives about history to make a profit. While all narratives shared with us about the past seem valuable, I had an intuition at the beginning of the semester that not all narratives hold as much weight as others do. I asked about the origins of popularized narratives and wondered what the process of distributing such pervasive information is like. I made assumptions that history as we know it is marketed to us. On our first trip to Holyoke, some of these questions I had been wondering about were made clear. The Wistariahurst museum was a site that housed many conflicting perspectives on the history of Holyoke. Gift shop items sold there pander to tourists and newer city residents, likely ones that are participating in the gentrification of Holyoke, that romanticize Holyoke without acknowledging the marginalization of black and brown community members. Extensive archives of community organizing, like the archives about activist Carlos Vega, represent and resonate with the pre-existing population of black and brown people in the city. The Wistariahurst museum met me with truthfulness though, despite some of the conflicting images within the building; many museums neglect to approach patrons with unsavory or difficult truths in an attempt to make a profit off of the history they are retelling. Conversation with the museum’s archivists and representatives, who were familiar with or resonate with the city’s working class community of color, allowed me to begin to answer some of my questions about the production of history, and affirmed the analogy of history being a product, which I presented in my introductory blog post.

In my post entitled, “Wistariahurst as a Contemporary Community Center,” I reflected on the connection between power, wealth, and privilege, and the ability to control collective memory in reference to history. I state, "I begin to wonder, how people like Skinner use their power and money to create structures and systems that assert familial power and memorialize white figures of history even after the death of an industry and a family." This thought mirrors similar inquiries that I had at the beginning of the semester, which I shared in my introduction. I asked, “Should we continue to feel entitled to land and spaces after knowing our unsavory beginnings?” In creating monuments to the past that center around or are curated from the perspective of dominant white figures of specific histories, we attempt to eternally recognize and memorialize specific interpretations of our past. Those who can afford to psychologically and, more importantly, physically set things in stone, demonstrate an entitlement to having the agency to control community and/or societal perceptions on significant events.

I posed a series of questions in my intro that I hoped would be answered for me by the end of the semester, and then clarified and explained to my reader. “Who should be in charge of sites rich with history? (Especially sites that center around marginalized people),” I asked. Unaware of the exact locations I would be visiting in Holyoke this semester, I was pleasantly surprised when we had the opportunity to visit the Wistariahurst museum. By learning about the Skinner Family and their wealth, stemming from manufacturing in Holyoke, the social and political power the family was able to exercise because of their orchestrating role in furthering the economic development of Holyoke, made it clear to me that money holds significant power. The Skinner’s ability to shift the tone of a community simply by constructing opulence in the midst of normalcy is reason enough to dissuade me from thinking that those in charge of managing sites rich with history should be those who were the dominating figures of the past. Establishing the tone of historical narratives that don't consider or include non dominant figures who were also involved in what is being recounted, makes for a uncredible source. I was very impressed with the Wistariahurst staff, as they made a point to ensure that the historical building was preserved and acknowledged as a site of importance, but are using their own knowledge of the past and present to design specific programming around education that happens in the museum. They chose to dedicate time during the tour to show us the Wistariahurst archives of community organizers and have a discussion with the museum’s archivist, specifically hired to further explore and uncover the history and contributions of Black people in the city of Holyoke. The Wistariahurst staff we interacted with realize the importance of allowing the community to control and influence what occurs within spaces of importance around the neighborhood.